Abstract

Background:

Colorectal cancer mortality could be decreased with risk-appropriate cancer screening. We examined the efficacy of three tailored interventions compared to Usual Care for increasing screening adherence.

Methods:

Women (n=1196) ages 51 to 74, from primary care networks and non-adherent to colorectal cancer guidelines were randomized to: 1) Usual Care, 2) tailored Web intervention, 3) tailored Phone intervention, or 4) tailored Web + Phone intervention. Average-risk women could select either stool test or colonoscopy, while women considered at higher than average risk received an intervention that supported colonoscopy. Outcome data were collected at 6 months by self-report followed by medical record confirmation (attrition of 23%). Stage-of-change for colorectal cancer screening (Precontemplation or Contemplation) was assessed at baseline and 6 months.

Results:

The Phone (41.7%, p<.0001) and combined Web+Phone (35.8%, p<.001) interventions significantly increased colorectal cancer screening by stool test compared to Usual Care (11.1%) with odds ratios ranging from 5.4 to 6.8 in models adjusted for covariates. Colonoscopy completion did not differ between groups, except that Phone significantly increased colonoscopy completion compared to usual care for participants in the highest tertile of self-reported fear of cancer.

Conclusion:

A tailored Phone with or without a Web component significantly increased colorectal cancer screening compared to Usual Care, primarily through stool testing, and phone significantly increased colonoscopy compared to usual care but only among those with the highest levels of baseline fear.

Impact:

This study supports tailored phone counseling with or without a web program for increasing colorectal cancer screening in average risk women.

Keywords: Colon cancer screening, interventions, tailoring, stool test, colonoscopy

Introduction

Despite evidence that breast and colorectal cancer screening can significantly reduce mortality, screening rates fall below the standards set by the Healthy People 2020 initiative (1–3). We report colorectal cancer screening outcomes from a randomized controlled intervention trial supported by the National Cancer Institute and developed to increase colorectal cancer screening using tailored Web and Phone-based interventions. All women were nonadherent to colorectal cancer screening at baseline.

Randomized clinical studies show behavioral interventions, including mailed invitations, telephone counseling, navigation, and a combination of patient navigation and telephone support, significantly increase colorectal cancer screening compared to usual Care (4–7). Furthermore, tailoring to demographic and belief variables (e.g., perceived risk, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, self-efficacy, fatalism, and fear) increases relevance of the intervention messages, thereby increasing intervention effects (8–10). When comparing tailored messages to non-tailored approaches or to motivational interviewing, some research has found tailored messages significantly improve cancer-screening behaviors (11–19). Furthermore, studies found that that allowing average risk individuals to select either stool test or colonoscopy resulted in increased screening (20, 21).

Although tailored interventions are efficacious, most studies have not tailored on a comprehensive set of variables that include baseline stage of change, demographics, and belief variables. (22, 23). With rapid advances in technology, our ability to develop phone or web-based messages tailored to a larger set of variables is possible. Additionally, although prior studies had utilized telephone counseling, at the time the present study was designed, few tailored web-based interventions had been tested, and most phone counseling interventions did not include tailored messaging. If a web-based approach were efficacious, it could potentially decrease cost and increase dissemination for cancer screening interventions. Finally, it was hypothesized that the additive effect of web plus phone had the potential to increase screening beyond either individual intervention.

Thus, this trial used a full 2×2 factorial design to assess tailored messaging delivered by Web, Phone or both Web+Phone compared to Usual Care to increase completion of colorectal cancer screening. A secondary outcome was stage-of-change for colorectal cancer screening (intention to screen). Covariates included demographics, comorbidities, and baseline colorectal cancer knowledge, beliefs, and stage-of-change for colorectal cancer screening. Specific research questions were:

Are there differences between randomized groups and usual care in adherence and stage-of-change for colorectal cancer screening defined as: a) stool test, b) colonoscopy, c) either screening test (stool test or colonoscopy), d) risk-appropriate screening.

Methods

Study design:

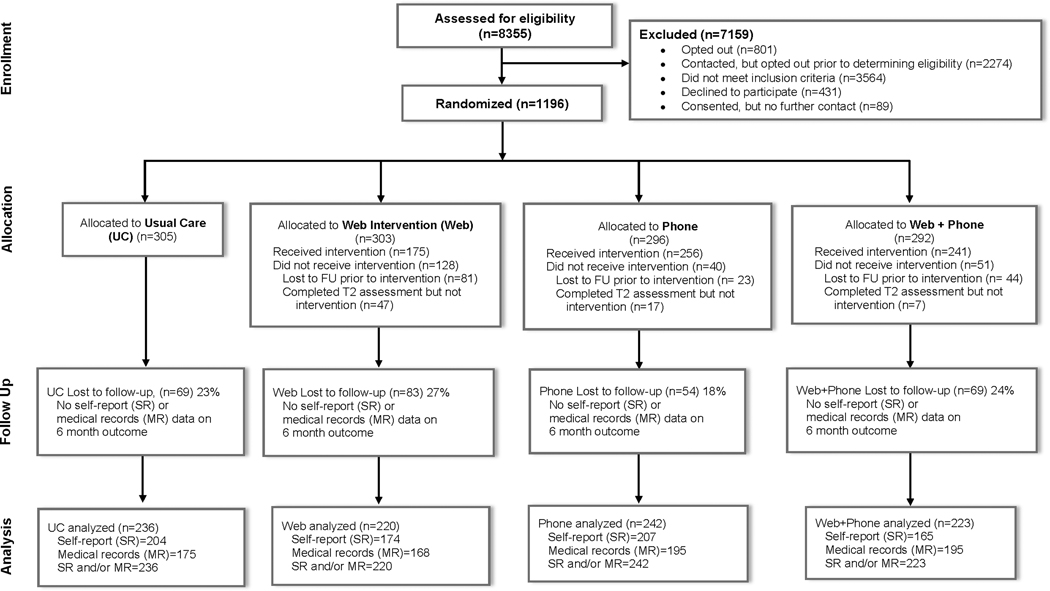

A prospective, randomized factorial design compared the impact of three tailored interventions to Usual Care on colorectal cancer screening adherence and stage-of-change to complete colorectal cancer screening. A total of 1196 woman were randomized to four groups: 1) Usual Care, 2) tailored Web-based, 3) tailored Phone counseling, or 4) a Web-based + Phone counseling intervention. The Consort Diagram is illustrated in Figure 1. The randomization was performed in a Microsoft SQL database, using SQL random ordering functions, without additional stratification. The sample size (at least 200 in each randomized arm) was calculated to yield a power of 80% to detect a 15% difference between each intervention group and Usual Care on the primary outcome of 6 month best-estimate for any CRC screening (e.g., 200 per arm yields 86% power for 35% vs 20%; or 92% power for 50% vs 35%; see Table 2 footnote for the actual sample size, which was slightly greater than 200 per arm. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Indiana University and community sites. This study is registered with the clinical trials identifier NCT03279198 https://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT03279198.

Figure 1:

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram

Table 2.

Logistic Regression (LR) Models of 6 Month (T3) Colorectal Cancer Outcomes

| Outcomes & Randomized Groups | Best-Estimate Data (Medical Record and Self-Report) | Self-Report Data (Stage) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 (Binary LR Model) T3 Screen (yes/no) | Model 2 (Generalized LR Model; reference category = T3 Precontemplation) | |||||

| T3 Contemplation | T3 Action | |||||

| Adjusted OR | p-value | Adjusted OR | p-value | Adjusted OR | p-value | |

| Any Colorectal Cancer screening test | ||||||

| Web only | 1.01 (0.63, 1.62) | .9626 | 1.97 (1.14, 3.40) | .0152 | 1.81 (0.99, 3.30) | .0537 |

| Phone only | 4.00 (2.60, 6.16) | <.0001 | 2.37 (1.28, 4.39) | .0058 | 7.94 (4.33, 14.56) | <.0001 |

| Web + Phone | 2.69 (1.73, 4.18) | <.0001 | 2.52 (1.33, 4.77) | .0045 | 6.68 (3.56, 12.54) | <.0001 |

| Risk-appropriate colorectal cancer test | ||||||

| Web only | 0.94 (0.59, 1.51) | .7982 | 1.92 (1.11, 3.32) | .0195 | 1.62 (0.89, 2.96) | .1163 |

| Phone only | 4.00 (2.60, 6.17) | <.0001 | 1.99 (1.08, 3.67) | .0277 | 7.07 (3.89, 12.85) | <.0001 |

| Web + Phone | 2.59 (1.67, 4.03) | <.0001 | 2.37 (1.26, 4.48) | .0076 | 6.08 (3.26, 11.34) | <.0001 |

| Stool test | ||||||

| Web only | 1.20 (0.64, 2.24) | .5772 | 2.07 (1.17, 3.67) | .0126 | 1.78 (0.86, 3.68) | .1208 |

| Phone only | 6.80 (3.98, 11.60) | <.0001 | 1.93 (1.04, 3.57) | .0364 | 9.81 (5.21, 18.48) | <.0001 |

| Web + Phone | 5.37 (3.11, 9.29) | <.0001 | 2.86 (1.50, 5.45) | .0014 | 12.14 (6.26, 23.57) | <.0001 |

| Colonoscopy | ||||||

| Web only | 0.70 (0.37, 1.33) | .2794 | 1.02 (0.57, 1.80) | .9516 | 0.96 (0.46, 1.97) | .9005 |

| Phone only | 1.39 (0.77, 2.52) | .2717 | 0.64 (0.35, 1.14) | .1285 | 1.38 (0.70, 2.70) | .3534 |

| Web + Phone | 0.88 (0.48, 1.61) | .6750 | 0.83 (0.46, 1.49) | .5275 | 0.84 (0.41, 1.72) | .6274 |

Models adjusted for baseline characteristics including age, race (African American vs Other), education, income, marital status, BMI, whether depression limits patient’s activities (yes/no), family history of 1 or more blood relatives with colon cancer (yes/no), perceived risk, doctor recommendation (yes/no), number of past-year primary care visits excluding eye care and dentistry (>=3), number of self- reported health problems, baseline adherence to mammography screening (yes/no), baseline stage of change for colorectal cancer screening, knowledge, susceptibility, benefits, fear, fatalism, self-efficacy, and barriers. Self-efficacy and barriers specific for colonoscopy or stool test were used in colonoscopy and stool test models, respectively. Sample sizes for Models 1 and 2, respectively, were: any colorectal cancer (843, 683), risk appropriate colorectal cancer (842, 681), stool test (836, 642), and colonoscopy (835, 643).

Women were interviewed at baseline and 6 months post-intervention. Medical records were obtained at 6 months post-intervention to verify screening and obtain a six month outcome variable, if women dropped prior to 6 month data collection. Women assigned to the Web-based intervention group completed an interactive computer program that provided tailored messages based on their feedback to tailoring questions quieried throughout the program. Women assigned to the Phone intervention received messages from a trained interventionist and tailored to real time feedback-with similar to the Web program. Women assigned to the combination of Web and Phone were first directed to complete of the Web program followed within four weeks by a Phone counseling intervention. If women had not completed the Web program within four weeks of being randomized, research assistants called to schedule the Phone counseling but emphasized completion of the Web program prior to their Phone counseling appointment.

Eligibility and recruitment:

Women were eligible if they were ages 50 to 75, nonadherent to colorectal cancer screening guidelines, and had access to the internet. To be considered nonadherent, participants had to confirm they had not completed: 1) a fecal stool test in the last 15 months; 2) a sigmoidoscopy in the last 5 years; or 3) a colonoscopy in the last 10 years. Exclusion criteria included: 1) having a personal history of colorectal cancer, colorectal polyps, or inflammatory bowel disease, and 2) having any medical conditions that would prohibit colorectal cancer screening. Although all women were non adherent to colorectal cancer screening, approximately half of the women accrued were currently adherent to breast cancer screening and half non adherent to breast cancer screening. Adherence to breast cancer screening status was used as a covariate.

A list of women ages 50 to 75 with no medical record of guideline-based screening for colorectal cancer or exclusionary criteria in two community-based family health care systems was forwarded to Indiana University’s Survey Center whose staff completed all accrual and data collection calls. Prior to calling women, introductory letters were mailed explaining the study and offering an opt-out opportunity through returning a postage-paid postcard or calling a toll-free number. If women did not opt out after two weeks, a call was placed to confirm eligibility and explain details of the study. After confirming eligibility, women were asked if they would participate and verbal consent was obtained for the baseline interview which was completed during the initial conversation. Women were also allowed the opportunity to complete the baseline survey via web. After verbal or web consent, participants were mailed a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) authorization form for release of medical record data and a written informed consent which was mailed back with a postage paid envelop. Data were collected at three times-baseline, two weeks after intervention (process data) and six months after intervention. Participants received a $20.00 gift certificate at each data collection time point.

Outcomes of interest:

Outcomes were completion of colorectal cancer screening by stool test, colonoscopy, either screening test, or a risk-appropriate screening test. Risk-appropriate CRC screening was defined as completion of the appropriate test based on the level of risk conferred by family history. For participants who had more than one first- degree relative who was diagnosed with CRC or a first-degree relative diagnosed younger than age 60, colonoscopy is the most appropriate screening test (24). Therefore, we examined whether women had completed the appropriate test based on their CRC risk (family history). A total of 275 (23%) were lost to follow-up. The Web group had the highest attrition (27%) and the Phone group had the lowest (18%). For analyses, we used a best estimate outcome data set which combined both self-report and medical record data. We counted the screening positive if either self-report or medical record data indicated a screening test. This best-estimate data set allowed us to include women who did not have six-month self-report but had medical record data or conversely allowed use of self-report data, if medical records data were not available. Although kappa coefficients showed adequate agreement (.76 for stool test and .85 for colonoscopy) the best estimate dataset served to decrease potential bias due to missing data in either interview or medical record information.

Measures:

Demographic information, family history, and cancer screening history were assessed using standard questions. Belief scales of perceived risk of colorectal cancer, perceived benefits and barriers to colorectal cancer screening, self-efficacy, fatalism, and fear were measured by scales found to be valid and reliable in past research (25–27). Intention to screen for colorectal cancer and actual screening were assessed by questions successfully used in past research (28).

Interventions

Web only Intervention:

A tailored health behavior change intervention was guided by the Health Belief Model, the Transtheoretical Model, and the Likelihood Persuasion Behavioral Theory (29–32). Tailoring focused on key demographic variables (e.g., age, race) and belief variables (mediators) that were theoretically linked to screening behavior in addition to preferred colorectal cancer screening test (33–35). An algorithm embedded in the program directed women at higher than average risk to an intervention that encouraged colonoscopy while women at average risk were allowed to select either stool test or colonoscopy followed by a program consistent with their preferred test.

The tailored Web program was developed such that a woman’s demographic and belief responses (queried throughout the program) triggered an algorithm which selected and delivered messages tailored to each woman’s response. Constructs used for tailoring included age, race, family history of colon cancer, knowledge and beliefs about colon cancer and colorectal cancer screening. Messages were developed and refined from previous research using similar tailoring (22). For example, if a woman did not perceive a personal risk for colorectal cancer or benefits of screening, messages were delivered to reinforce the fact that colorectal cancer can happen to anyone and that screening identifies cancer early when treatment is most successful. Women were able to identify up to three personal barriers and for each barrier identified, a message was delivered suggesting ways to overcome the barrier.

The Web program included graphs, text, videos and animation to reinforce verbal messaging. Further information about development of the tailored program is provided in Supplemental Data Table 1.

Phone only Intervention:

A computer program was used to structure the content and flow of the telephone counseling session. The trained interventionists queried women throughout the program to tailor messaging. Messaging was delivered in a conversational way to increase engagement and interest of participants. The computer interface provided structure for discussing content consistent with the message flow in the Web-based program. Telephone interventionists were trained during an intensive 2-day session with an opportunity for role playing. All telephone interventions were audio recorded with the consent of the participant. For people at average risk, the interventionist ask about their preferred tests and if a woman stated stool test, it was mailed to their home. If the woman were at high risk or preferred colonoscopy, a number to schedule the colonoscopy was provided. The mean time for the Phone intervention was 19 minutes.

Treatment fidelity was enhanced by: 1) extensive training of interventionists that included practice and return demonstration of skills; 2) implementation of a process evaluation for all participants to evaluate their receipt of, and satisfaction with, the interventions; and 3) monitoring of a random selection of 101 (17%) recorded telephone interventions with performance feedback as needed (36). Evaluators used a checklist to evaluate each call which included ratings of the degree of completeness and quality of the information delivered by the interventionist.

Web + Phone Intervention:

Women randomized to the combined Web and Phone intervention completed the Web program followed within four weeks by Phone counseling. The time for the phone intervention in this arm did not differ significantly from the time used in the phone intervention alone (19 minutes).

Usual Care:

Women randomized to Usual Care did not receive an intervention, but depending on location of the family practice site, enrolled women may have received a postcard reminder for cancer screenings from their primary care provider.

Study Endpoints and Analytical Strategy:

The primary study endpoint for analyses was colorectal cancer screening test completion at six months post-intervention. Of the 1,196 women who completed baseline interviews, 921 had screening data from either six-month self-report, medical record, or both and were included in analyses. An intent to treat analyses (i.e., all participants are analyzed according to randomized group, regardless of adherence to intervention) was completed. However, although we attempted an intent to treat design (collect all data on consented participants even if they dropped out before follow up interview), we were not able to obtain outcome data (medical record or self-report) on all participants (36,37).

Four colorectal cancer screening outcomes were created based on best-estimate data from medical record or self-report. Additionally, we modeled stage-of-change for screening with self-report data. (Table 2, Model 2). Women were considered to be in Precontemplation if they did not intend to have colorectal cancer screening in the next six months and in Contemplation if they intended to have colorectal screening in the next six months. Action was defined as being adherent to colorectal cancer screening guidelines and this stage could apply only to women who were adherent at six months. Thus, after intervention, women could move from: 1) Precontemplation to Contemplation; 2) Contemplation to Action (1 step forward); or 3) Precontemplation to Action (2 steps forward).

Multinomial logistic regression models were used to model 6-month stage-of-change by simultaneously estimating odds ratios for women in Action or Contemplation at six months while adjusting for the stage at baseline (either Precontemplation of Contemplation). In binary and multinomial logistic regression models, randomized group assignment and baseline covariates were entered as the independent variables. Covariates entered were either theoretically justified or differed between randomized groups at the 0.10 alpha level (see covariates listed in Table 2 footnote). Wald chi-square tests, adjusted odds ratios, and 95% confidence intervals were reported. Interactions between the intervention and baseline covariates were tested for potential moderating effects, using a conservative alpha of 0.01.

Results

A total of 1,716 woman were eligible for the study. Of these, 520 refused, resulting in a participation rate of 70%. Of the 1,196 women enrolled, 921 had 6-month follow up data (See Figure 1). Demographic characteristics of the women did not differ by group. (Table 1). The mean age was 58.9 (SD=6.2). A total of 24.3% of women reported a high school education or less, 42% reported one or more years post high school and 30.2% reported a 4-year college degree or higher. The predominant race was Caucasian (86.3%), while 10.4% of participants were African-American. A total of 60% were married or living with a partner. Income was distributed as $30,000 or less (31.2 %), $30,001 to $75,000 (41.2%), $75,001 or above (27.6%).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics by Randomized Group

| Baseline Characteristics Number (%) or Mean (SD) | Total Sample (n=1196) | Web (n=303) | Phone (n=296) | Web + Phone (n=292) | Usual Care (n=305) | p- value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doctor or HCP ever suggested you do a stool test? n(%) responding yes | 458 (38.3) | 120 (39.6) | 119 (40.2) | 108 (37.0) | 111 (36.5) | 0.7304 |

| Doctor ever recommended that you have a colonoscopy? n(%) responding yes | 785 (65.8) | 194 (64.2) | 192 (65.1) | 201 (68.8) | 198 (65.1) | 0.6480 |

| Baseline adherence to breast cancer screening | 504 (42.1) | 123 (40.6) | 128 (43.2) | 125 (42.8) | 128 (42.0) | 0.9185 |

| Baseline Colorectal Cancer Screening Stage, n(%) in Contemplation at baseline; (n, % in Precontemplation can be calculated as 100 - % shown below) | ||||||

| Stool test at home | 173 (14.5) | 43 (14.2) | 44 (14.9) | 41 (14.0) | 45 (14.8) | 0.9894 |

| Colonoscopy | 291 (24.3) | 79 (26.1) | 66 (22.3) | 76 (26.0) | 70 (22.9) | 0.5858 |

| Any Colorectal cancer Screening | 410 (34.3) | 107 (35.3) | 98 (33.1) | 104 (35.6) | 101 (33.1) | 0.8639 |

| Risk-appropriate Colorectal cancer screening | 404 (33.8) | 106 (35.0) | 98 (33.2) | 101 (34.6) | 99 (32.5) | 0.7062 |

| Age, mean (SD) | 58.9 (6.2) | 59.3 (6.4) | 58.7 (6.0) | 58.6 (5.9) | 58.9 (6.3) | 0.5727 |

| Highest education | 0.5279 | |||||

| High school graduate or less | 332 (27.8) | 79 (26.1) | 85 (28.9) | 90 (30.8) | 78 (25.7) | |

| Some college | 501 (42.0) | 137 (45.2) | 120 (40.8) | 121 (41.4) | 123 (40.5) | |

| 4 year college graduate to graduate degree | 360 (30.2) | 87 (28.7) | 89 (30.3) | 81 (27.7) | 103 (33.9) | |

| Race | 0.0363 | |||||

| Black or African American | 124 (10.4) | 40 (13.2) | 22 (7.4) | 36 (12.3) | 26 (8.5) | |

| White or Caucasian | 1032 (86.3) | 255 (84.2) | 269 (90.9) | 243 (83.2) | 265 (86.9) | |

| Asian, Pacific Islander, or Other | 40 (3.4) | 8 (2.6) | 5 (1.7) | 13 (4.5) | 14 (4.6) | |

| Married or living with a partner | 719 (60.4) | 182 (60.1) | 188 (64.0) | 171 (58.8) | 178 (58.8) | 0.4493 |

| Total combined yearly household income before taxes | 0.6973 | |||||

| $30,000 or less | 359 (31.2) | 99 (33.9) | 82 (28.8) | 95 (33.3) | 83 (28.6) | |

| $30,001 – $75,000 | 474 (41.2) | 114 (39.0) | 124 (43.5) | 110 (38.6) | 126 (43.5) | |

| $75,001 or above | 319 (27.6) | 79 (27.1) | 79 (27.7) | 80 (28.1) | 81 (27.9) | |

| In the past year, how many times have you seen your doctor or other HCP? (not counting dentist or eye doctor) | ||||||

| 3 or more times, n (%) | 573 (48.3) | 167 (55.5) | 130 (44.1) | 144 (49.5) | 132 (44.2) | 0.0144 |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | 0.6359 | |||||

| Underweight / Normal | 287 (25.0) | 70 (24.0) | 74 (26.2) | 72 (25.9) | 71 (24.1) | |

| Overweight | 324 (28.2) | 86 (29.5) | 82 (29.0) | 66 (23.7) | 90 (30.5) | |

| Obese | 537 (46.8) | 136 (46.6) | 127 (44.9) | 140 (50.4) | 134 (45.4) | |

| Total number of self- reported health problems, mean (SD) | 1.8 (1.7) | 2.1 (1.8) | 1.7 (1.7) | 1.8 (1.6) | 1.7 (1.6) | 0.0190 |

| Does depression limit your activities? n (%) yes, | 99 (8.5) | 27 (9.1) | 17 (6.0) | 37 (12.8) | 18 (6.0) | 0.0084 |

| Perceived age- adjusted risk for colon cancer, n (%) | 0.6297 | |||||

| About the same or not sure | 873 (73.0) | 216 (71.3) | 212 (71.6) | 225 (77.3) | 220 (72.1) | |

| Higher risk | 82 (6.9) | 22 (7.3) | 19 (6.4) | 17 (5.8) | 24 (7.9) | |

| Lower risk | 240 (20.1) | 65 (21.4) | 65 (22.0) | 49 (16.8) | 61 (20.0) | |

| Cancer and Cancer Screening Beliefs | ||||||

| Fatalism | 20.5 (6.9) | 20.4 (6.4) | 20.9 (7.2) | 20.6 (6.8) | 20.1 (7.0) | 0.6159 |

| Fear | 23.0 (7.5) | 23.1 (7.5) | 23.4 (7.6) | 22.9 (7.5) | 22.4 (7.3) | 0.4497 |

| Susceptibility to colon cancer | 6.8 (2.2) | 6.8 (2.2) | 6.8 (2.2) | 6.8 (2.3) | 6.8 (2.2) | 0.9895 |

| Benefits of colorectal cancer screening | 18.1 (3.1) | 18.1 (3.1) | 18.0 (3.3) | 18.0 (3.0) | 18.1 (3.1) | 0.9260 |

| Barriers to Stool Test | 20.1 (5.0) | 19.9 (5.3) | 20.4 (5.0) | 20.1 (5.1) | 19.9 (4.6) | 0.5577 |

| Barriers to colonoscopy | 36.1 (8.7) | 36.0 (8.8) | 36.6 (9.0) | 36.3 (8.9) | 35.3 (8.0) | 0.2744 |

| Self-efficacy for Stool Test | 28.4 (4.8) | 28.4 (4.8) | 28.7 (4.5) | 28.2 (5.3) | 28.4 (4.7) | 0.5341 |

| Self-efficacy for colonoscopy | 36.9 (7.2) | 36.7 (7.5) | 36.7 (7.2) | 36.9 (7.3) | 37.3 (6.7) | 0.7387 |

| Knowledge for colonoscopy | 5.3 (1.9) | 5.2 (1.9) | 5.3 (1.9) | 5.2 (2.0) | 5.3 (1.9) | 0.8782 |

Note. For continuous variables and ordinal income, the two-sided independent-groups t-test was used unless parametric assumptions were violated in which case the two-sided Kruskal-Wallis test was used. For categorical variables, the chi-square test was used. HCP = health care provider. COLORECTAL CANCER = colorectal cancer

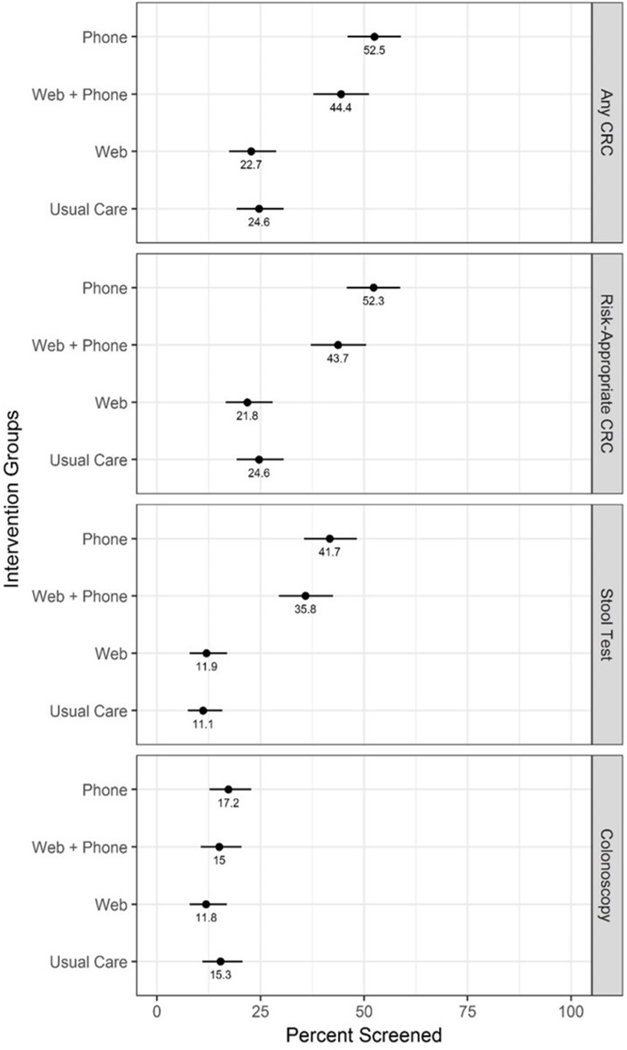

Univariate analyses of colorectal cancer screening outcomes is illustrated in Figure 2. Percentages of women adherent at six months to any colorectal cancer screening test (Web=22.7%, Phone=52.5%, Web+Phone=44.4%, Usual Care=24.6%) were very similar to the percentages adherent to risk-appropriate colorectal cancer screening (Web=21.8%, Phone=52.3%, Web+Phone=43.7%, Usual Care=24.6%). Colonoscopy rates did not differ by group.

Figure 2:

Comparisons of 6 Month Colorectal Cancer Screening outcomes between Randomized Groups Using Best-Estimate Data

Logistic regression was used to compare interventions groups to Usual Care on each 6-month screening outcome while controlling for important covariates (See Table 2 and footnote). Model 1 in Table 2 identifies the p-values and adjusted odds ratios for colorectal cancer screening at 6 months by intervention group. Because none of the theoretically identified covariates had significant odds ratios after adjusting for each other, we display only the group differences in tables. Screening adherence at six months for any colorectal cancer screening test or for risk-appropriate colorectal cancer screening was significantly higher for women in the Phone and Phone+Web intervention groups (p<0.0001) compared to the Usual Care. Completion of a stool test was similar across groups (Web=11.9%, Phone=41.7%. Web + Phone=35.8%, and Usual Care=11/1%). Adherence for colonoscopy was low (Web, 11.8%, Phone, 17.2%, Web+Phone 15.0% and Usual Care 15.3%)-with no significant differences across groups.

The four randomized groups were compared on stage-of-change to screen. In Model 2 (Table 2), the odds of being in Contemplation or Action (versus pre-contemplation) at 6 months are reported, adjusted for baseline stage and covariates. Demographic and experiential variables entered into the equation were not significant. Table 2 provides data to interpret efficacy to move or retain participants to Contemplation or to move participants to Action, adjusted for baseline stage. All three intervention arms (including Web only) were significantly better than Usual Care in increasing the odds for being in Contemplation vs Precontemplation at 6 months for any colorectal cancer screening test (Web p<0.0140, Phone p<0.0057, Web+Phone p<0.0032), for risk-appropriate colorectal cancer screening (Web p=0.0179, Phone p<0.0270, Web+Phone p<0.0053), and for stool test (Web p<0.0100, Phone p<0.0281, Web +Phone p=0.0017). Compared to Usual Care, none of the interventions had a significant effect on 6-month stage-of-change for colonoscopy.

When considering efficacy to move participants to Action from Precontemplation at 6 months for any colorectal cancer screening test the Web was marginally significant (p<0.0537), while the Phone (p<0.00001), Web+Phone (p<0.0001), were very significant compared to Usual Care. For risk-appropriate colorectal cancer screening, Phone (p<0.00001) and Web+Phone (p<0.0001) interventions were significantly different than Usual Care in moving women to from Precontemplation to Action. For stool tests, the Phone (p<0.0001) and Web+Phone (p<0.0001) interventions were significantly better than Usual Care for moving women from Precontemplation to Action. Intervention arms were not different from Usual Care in completion of colonoscopy.

Interaction tests revealed only one significant interaction at 0.01 alpha between intervention effects and baseline covariates (p = 0.0008). Specifically, post-hoc simple effects showed that among participants in the highest tertile of baseline fear scores (n = 253), Phone was significantly more effective than usual care at moving participants to obtain a colonoscopy (odds ratio = 16.39 [2.84, 94.79], p = .002).

Discussion

Results demonstrate the significant impact of Phone counseling to promote colorectal screening. Importantly, the interventions that included Phone included the proactive offer of a mailed stool kit. It is probable that a stool test mailed to their home was the major factor producing the large effect sizes found for Phone and Phone+Web in this study, consistent with other researchers who found that mailing stool test kits increased colorectal cancer screening (7). In particular, Singal found that mailing stool test kits to primary care patients resulted in participation rates of close to 59% (38).

Another factor that may have increased the effects found in this study was allowing average risk women (95%) to select preferred tests. Myers studied 764 African Americans ages 50 to 75 and found that in an intervention, which included a navigation component, persons who expressed a preference for stool testing were much more likely to obtain a stool test than a colonoscopy (41.1% vs. 7.1%) (39). The comparison group, with no personal contact, showed a much smaller advantage for stool testing among persons who expressed a preference (12.1% vs. 7.6%), even though a stool kit had been mailed to them. The personal contact with an interventionist may be an important factor (39).

We cannot conclude that tailoring played a role in the large effect found with our Phone intervention groups. Without a non-tailored phone intervention arm, we do not know if the tailoring used for phone messaging increased stool testing beyond what a non-tailored phone call and mailing stool kits would have accomplished. The fact that the tailored Web-based program did not increase screening and the tailored Phone intervention with mailed stool kits did, suggests that tailoring did not add to the effectiveness of the Phone intervention, although, it is possible that the interaction of tailoring and personal contact by phone added to the effect size we found. Additionally, we have no way of knowing whether mailing a stool kit without a tailored web or phone intervention would have been more effective than usual care.

The tailored Web-based intervention did not increase stool testing compared to Usual Care, a finding supported by other studies using a web-based approach. In a similar attempt to use a tailored interactive computer intervention to promote colorectal cancer screening, Vernon did not find a significant difference in randomized groups comparing a tailored interactive computer program, an informational web program or a survey only group for improving colorectal cancer screening (40). Our decision to use a Web-based approach as one media for delivery reflected the growing penetration of households that now have high speed internet- approximately 75% (46) and the hope that this less expensive intervention could increase screening. The combination of Web plus Phone, although significantly different from Usual Care, produced slightly lower effect sizes than the Phone alone, suggesting that in the presence of Phone outreach, a web-based intervention did not add to the effect.

Rates of colonoscopy screening were not significantly different for any intervention group compared to Usual Care, except when considering the moderating effect of fear. In retrospect, this outcome is understandable. Women at average risk were allowed to select a preferred test and if screening by stool test was the preferred modality, colonoscopy was not promoted, and the intervention focused on stool testing. Furthermore, 95% of women in our sample were at average risk and of those assigned to intervention groups, (Usual Care didn’t select preferred test) 63% stated preference for stool test, 37% stated preference for colonoscopy, and 1% did not state preference. Given the overwhelming preference for stool testing, it is probable that the intervention forestalled women from thinking about colonoscopy. However, research suggests that for women at higher than average risk, phone interventions have significantly increased colonoscopy compared to usual care (41–43). Kinney (2014) tested a telehealth intervention with relatives of colorectal patients using tailored content via phone outreach compared to a mailed educational brochure and found the telehealth intervention resulted in 35.4% of those in the telehealth vs only 15.7% in the mailed brochure completed colonoscopy (43). Additionally, in a sample of high-risk individuals with a family history of colorectal neoplasia, a tailored nurse led intervention resulted in a significant uptake of colonoscopy compared to control (p=.0027) (44).

Demographic and belief variables were tested for moderation and the only significant (alpha 0.10) interaction was between the phone only group and higher levels of fear. Among those with the highest levels of baseline fear of cancer, the Phone intervention group had significantly higher rates of obtaining colonoscopy that Usual Care. This suggests a future opportunity to move high-risk persons to obtain colonoscopy if they report higher levels of fear of cancer.

Although stages of change have been used in a range of behavioral interventions, its use has been limited for studies assessing colorectal cancer screening. We tested the ability of any intervention group compared to Usual Care to advance stage movement for colon cancer screening. All three interventions, including the Web, were successful in promoting forward stage movement from Precontemplation to Contemplation. Additionally, the Web-based intervention, like interventions with phone counseling was marginally significant in moving women in Precontemplation at baseline to Action. A research study that also used stage movement in analyses found an intervention effect for forward stage movement, although no overall increase in actual screening was found (40). Our Web-based intervention included compelling stories from other women about the necessity to screen, an animation of how cancer develops and a visual description of screening tests; perhaps these elements were most important for women who were not considering screening at baseline, allowing the Web-based intervention to increase screening for women at the 6-month follow-up.

Limitations

As with all studies, results of this RCT should be interpreted within the context of the study’s limitations. Women comprised a volunteer sample and included only 70% of those invited. Additionally, women were primarily Caucasian and patients of family practice clinics, already engaged with the medical care system. Results could differ for persons without a health care home or for women of color or Hispanic origin. Furthermore, we were not able to follow women to determine intervention effectiveness for having subsequent annual stool testing. We implemented an intent-to treat design, however, because outcome data were not available on all consented participants, the number analyzed was smaller than the number consented. Finally, additional research is needed to determine the most effective intervention that will support colonoscopy, especially for those women at higher than average risk who require a colonoscopy.

Conclusion

The tailored Phone interventions with or without a Web-based program, significantly increased screening for all participants by stool tests, with the large effect sizes probably due to outreach by Phone and proactive mailing of preferred test (stool kit). The tailored web-based intervention increased screening only in the subgroup of women in Precontemplation at baseline although this finding was only marginally significant. The interventions tested in this study did not increase screening by colonoscopy-with the exception of those with high fear at baseline- possibly because 95% of women were at average risk and were allowed to select their preferred screening test which was most often stool test instead of colonoscopy.

Acknowledgements

Victoria L. Champion and Patrick Monahan had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. Victoria L. Champion, Carla D. Kettler, Timothy E. Stump and Patrick Monahan, all from Indiana University, conducted and are responsible for the data analysis. The authors would like to acknowledge Kathy Zoppi, Kate Bol, Allison Woody, and Susan Wathen from the Community Health Network, Marc Rosenman and Evgenia Teal from Regenstrief Institute in Indianapolis, Indiana, for their assistance with obtaining lists of potential study participants and with their help with the medical records review process. Additionally, health care providers Deborah Allen and Tamika Dawson from Indiana University School of Medicine and Tamika Dawson from Indiana University Health were invaluable in adding a medical perspective to the design of the study.

Sources of Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by National Institutes of Health, RO1CA136940-5. The efforts of Shannon M. Christy were supported by the National Cancer Institute while she was a predoctoral fellow at Indiana University (R25CA117865; PI: V. L. Champion) and while she was postdoctoral fellow at Moffitt Cancer Center (R25CA090314; PI: T. H. Brandon). The efforts of Andrea A. Cohee and Andrew Marley were supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number T32CA117865, while Andrea A. Cohee was a postdoctoral fellow, and while Andrew R Marley was a predoctoral fellow at Indiana University School of Nursing, respectively. The efforts of Wambui Grace Gathirua-Mwangi were supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under the following: Award Number R25CA117865, (PI: V.L. Champion), while she was a predoctoral fellow, Award Number K05CA175048, and Award Number, 3R01CA196243-02S (Co-PI: V. L. Champion), while she was a predoctoral and postdoctoral fellow respectively, at Indiana University School of Nursing. The efforts of Will L. Tarver was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R25CA117865, ( PI: V.L. Champion), while he was a postdoctoral fellow at Indiana University School of Nursing. The efforts of Erika Biederman were supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number T32CA117865 while she is a predoctoral fellow at Indiana University School of Nursing, and from the American Cancer Society Graduate Scholarship in Cancer Nursing Practice, Award Number GSCNP-17-120-01. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This study is registered with the clinical trials identifier NCT03279198.

Abbreviation list:

- HIPAA

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act

- OR

odds ratio

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society, Cancer Facts & Figures, 2017. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levin B, et al. , Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. CA Cancer J Clin, 2008:58:130–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hesse BW, er al., Meeting the Healthy People 2020 Goals: Using the Health Information National Trends Survey to Monitor Progress on Health Communication Objectives, J Health Commun, 2014:19:1497–1509.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Enard KR, et al. , Patient navigation to increase colorectal cancer screening among Latino Medicare enrollees: a randomized controlled trial. Cancer Causes Control, 2015;26:1351–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Green BB, et al. , An automated intervention with stepped increases in support to increase uptake of colorectal cancer screening: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med, 2013:158:301–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ritvo PG, et al. , Personal navigation increases colorectal cancer screening uptake. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 2015:24:506–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gupta S, et al. , Comparative effectiveness of fecal immunochemical test outreach, colonoscopy outreach, and usual care for boosting colorectal cancer screening among the underserved: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med, 2013;173:1725–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ko LK, et al. , Information processes mediate the effect of a health communication intervention on fruit and vegetable consumption. J Health Commun, 2011;16:282–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lustria ML, et al. , A model of tailoring effects: A randomized controlled trial examining the mechanisms of tailoring in a web-based STD screening intervention. Health Psychol, 2016; 35: 1214–1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhao X and Peterson E, Effects of Temporal Framing on Response to Antismoking Messages: The Mediating Role of Perceived Relevance. J Health Commun, 2017;22:37–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jerant A, et al. , Effects of tailored knowledge enhancement on colorectal cancer screening preference across ethnic and language groups. Patient Educ Couns, 2013;90:103–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krebs P, Prochaska JO, and Rossi JS, A meta-analysis of computer-tailored interventions for health behavior change. Prev Med, 2010;51:214–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lustria ML, et al. , A meta-analysis of web-delivered tailored health behavior change interventions. J Health Commun, 2013;18:1039–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Albada A, et al. , Tailored information about cancer risk and screening: a systematic review. Patient Education and Counseling, 2009. 77: p. 1550171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kroeze W, Werkman A, and Brug J, A systematic review of randomized trials on the effectiveness of computer-tailored education on physical activity and dietary behaviors. Ann Behav Med, 2006;31: 205–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Noar SM, Benac CN, and Harris MS, Does tailoring matter? Meta-analytic review of tailored print health behavior change interventions. Psychol Bull, 2007; 133:673–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Velicer WF, Prochaska JO, and Redding CA, Tailored communications for smoking cessation: past successes and future directions. Drug Alcohol Rev, 2006;25:49–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kreuter MW, et al. , Tailoring health messages: customizing communication with computer technology. 2000, Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Menon U, et al. , A randomized trial comparing the effect of two phone-based interventions on colorectal cancer screening adherence. Annals of behavioral medicine : a publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, 2011;42:294–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robertson DJ, et al. , Recommendations on fecal immunochemical testing to screen for colorectal neoplasia: a consensus statement by the US Multi-Society Task Force on colorectal cancer. Gastrointest Endosc, 2017; 85: 2–21 e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Inadomi JM, Why you should care about screening flexible sigmoidoscopy. N Engl J Med, 2012;366:2421–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Champion VL, et al. , Randomized trial of DVD, telephone, and usual care for increasing mammography adherence. J Health Psychol, 2014;21:916–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rawl SM, et al. , Computer-delivered tailored intervention improves colon cancer screening knowledge and health beliefs of African-Americans.Health Edu Res, 2012;27:868–885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rex DK, et al. , Colorectal Cancer Screening: Recommendations for Physicians and Patients fronm the U.S. Multisociety Task Force on Colorectal Cancer Screening. Gastroenterology, 2017;153:307–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Champion VL, et al. , Measuring mammography and breast cancer beliefs in African American Women. Journal of Health Psychology, 2008;13:827–837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Champion VL, et al. , A breast cancer fear scale: Psychometric development. Journal of Health Psychology, 2004;9:769–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Powe BD, Cancer fatalism among elderly African American women: Predictors of the intensity of the perceptions. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 2001;19:85–95. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Champion VL, et al. , Comparison of younger and older breast cancer survivors and age-matched controls on specific and overall quality of life domains. Cancer, 2014;2237–2246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beeker C, et al. , Colorectal cancer screening in older men and women: qualitative research findings and implications for intervention. Journal of Community Health, 2000;25:263–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Price JH, Colvin TL, and Smith D, Prostate cancer: perceptions of African-American males. Journal of the National Medical Association, 1993;85:941–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Myers RE, et al. , Adherence to colorectal cancer screening in an HMO population. Preventive Medicine, 1990;19:502–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Farrands PA, et al. , Factors affecting compliance with screening for colorectal cancer. Community Medicine, 1984;6:12–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Katz ML, et al. , Do cervical cancer screening rates increase in association with an intervention designed to increase mammography usage? J Womens Health (Larchmt), 2007;16:24–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brown ML, et al. , The knowledge and use of screening tests for colorectal and prostate cancer: data from the 1987 National Health Interview Survey. Preventive Medicine, 1990;19:562–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Manne S, et al. , Correlates of colorectal cancer screening compliance and stage of adoption among siblings of individuals with early onset colorectal cancer. Health Psychology, 2002;21:3–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bellg AJ, et al. , Enhancing treatment fidelity in health behavior change studies: Best practices and recommendations from the NIH Behavior Change Consortium. Health Psychology, 2004;23: 443–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lachin JM, Statistical Considerations in the Intent-to-Treat Principle. Vol. 21 2000: Elsevier Science, Inc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Singal AG, et al. , Outreach invitations for FIT and colonoscopy improve colorectal cancer screening rates: A randomized controlled trial in a safety-net health system. Cancer, 2016;122: 456–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Myers RE, et al. , A randomized controlled trial of the impact of targeted and tailored interventions on colorectal cancer screening. Cancer, 2007;110:2083–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vernon SW, et al. , A randomized controlled trial of a tailored interactive computer-delivered intervention to promote colorectal cancer screening: sometimes more is just the same. Annals of behavioral medicine : a publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, 2011;41: 284–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lowery JT, et al. , A randomized trial to increase colonoscopy screening in members of high-risk families in the colorectal cancer family registry and cancer genetics network. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 2014; 23:601–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rawl SM, et al. , Tailored telephone counseling increases colorectal cancer screening. Health Educ Res, 2015;30:622–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kinney AY, et al. , Telehealth personalized cancer risk communication to motivate colonoscopy in relatives of patients with colorectal cancer: the family CARE Randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol, 2014;32:654–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ingrand I, et al. , Colonoscopy uptake for high-risk individuals with a family history of colorectal neoplasia: A multicenter, randomized trial of tailored counseling versus standard information. Medicine (Baltimore), 2016;95: e4303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]