Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The use of hyperbaric oxygen (O2) as a therapeutic agent carries with it the risk of central nervous system (CNS) O2 toxicity.

METHODS

To further the understanding of this risk and the nature of its molecular mechanism, a review was conducted on the literature from various fields.

RESULTS

Numerous physiological changes are produced by increased partial pressures of oxygen (Po2), which may ultimately result in CNS O2 toxicity. The human body has several equilibrated safeguards that minimize effects of reactive species on neural networks, believed to play a primary role in CNS O2 toxicity. Increased partial pressure of oxygen (Po2) appears to saturate protective enzymes and unfavorably shift protective reactions in the direction of neural network overstimulation. Certain regions of the CNS appear more susceptible than others to these effects. Failure to decrease the elevated Po2 can result in a tonic-clonic seizure and death. Randomized, controlled studies in human populations would require a multicenter trial over a long period of time with numerous endpoints used to identify O2 toxicity.

CONCLUSIONS

The mounting scientific evidence and apparent increase in the number of hyperbaric O2 treatments demonstrate a need for further study in the near future.

Keywords: hyperbaric oxygen seizures, hyperbaric oxygen therapy, CNS oxygen toxicity

Modern therapeutic use of hyperbaric oxygen (HBO2) in clinical medicine began in the 1950s.64,83 Boerema, a Dutch surgeon, in conjunction with the Royal Dutch Navy, was the first physician to “drench” the tissue of a patient with increased partial pressure of oxygen (Po2) with the use of a hyperbaric chamber.16 Through his work and subsequent experiments, HBO2 has been shown to have positive effects in treating wounds,67,104 and as a treatment for carbon monoxide (CO) toxicity.85,89 In 1977, Blue Cross/Blue Shield accepted a report from the Undersea Medical Society (now Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society) on hyperbaric oxygenation, which resulted in a list of disorders for which hyperbaric treatment should be considered. Many of today’s indications for hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBO2T) stem from this list. Current indications for HBO2T covered by Medicare are shown in to Table I.79,84,94 More research is needed to conclude for which indications HBO2T is most beneficial and to what extent.32

Table I.

Examples of Therapeutic Uses of HBO2.

| ELECTIVE INDICATIONS | EMERGENT INDICATIONS |

|---|---|

| Radiation injury* | Carbon monoxide poisoning |

| Compromised skin grafts | Decompression illness |

| Chronic nonhealing wounds# | Gas gangrene |

| Refractory osteomyelitis | Arterial gas embolism |

| Inhibition of clostridium perfringens | Ischemia-reperfusion injury |

| Suppression of autoimmune responses | Hemorrhagic anemia |

| Tissue salvage in burn victims | |

| Nerve cell regeneration | |

| Preparation and preservation of skin grafts |

“Radiation injury” includes soft tissue radionecrosis, osteoradionecrosis, and hemorrhagic radiation cystitis.

Particularly diabetic ulcers

HBO2T is a therapeutic modality that exposes the body to 100% inspired oxygen (O2) at ambient pressures greater than one atmosphere.79,107 Therapeutic administration of supplemental O2 generally refers to increasing the fractional inspired O2 (FIo2). Without the use of a hyperbaric chamber, FIo2 equals the partial pressure of inspired O2 (PIo2). This limits the range of PIo2 from 0.21 ATA [FIo2 = 21% at one atmosphere of absolute pressure (ATA)] to 1.0 ATA (FIo2 = 100% at 1 ATA); 1 ATA equals one atmosphere of pressure at sea level. Hyperbaric chambers increase ambient pressure, allowing the PIo2 to exceed 1 ATA. The majority of clinical uses for HBO2T derive their benefit from the increased Po2 that HBO2T provides.17 The increased Po2 delivered throughout the body causes reactive oxidative species (ROS) that promote wound healing and postischemic tissue survival.105 Hydrostatic effects of HBO2T that affect bubble size are beneficial for illnesses such as decompression sickness.83 HBO2T has been gaining increased attention in the popular press87,113 and among scientific researchers.70

The toxic nature of O2 is often underappreciated. There are side effects of the hydrostatic and oxidative changes that HBO2T creates, including HBO2 seizures.18,92 Determining mechanisms of HBO2 toxicity and its ability to cause seizures has been an effort of researchers in the hopes of maximizing the potential benefits of HBO2T while minimizing its risks.

Both patients and hyperbaric medical attendants are routinely exposed to the hyperbaric environment (although attendants do not routinely breathe HBO2) and are therefore exposed to an increased risk of O2 toxicity. There are special populations outside of medicine who are also routinely exposed to HBO2, including military, commercial and recreational divers, and subterranean workers.37,49,118 The risk of O2 toxicity is increased when the ratio of O2 to inert gas is raised in the hopes of minimizing deleterious gas effects. Combat divers use pure O2 via a rebreather apparatus for clandestine purposes (to avoid bubbles).37,82 High Po2 greatly increases the risk of O2 toxicity even at shallow depths but it also purges nitrogen from a diver’s body. Following missions, divers can be extracted and flown well above sea level with little concern for decompression sickness, making it ideal for clandestine and lengthy underwater operations.43,82 Concerns over CNS O2 toxicity remain a limiting factor in standard operating procedures for closed-circuit diving operations and HBO2T alike.37,83 Some deleterious effects of gases under pressure and the populations at risk are listed in Table II.

Table II.

Physiological Effects of Gases Under Pressure.*

| DEPTH (PRESSURE) OF ONSET | POPULATION | TOXICITY | SOURCE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sea level (1 ATA) | Everyone | CO | Incomplete hydrocarbon combustion |

| O2 (pulmonary, retinal) | Long exposures to 100% O2 | ||

| CO2 | Inadequate ventilation | ||

| 12 fsw (1.3 ATA) | Closed-circuit diver | O2 (CNS) | Breathing 100% O2 |

| 45 fsw (2.4 ATA) | HBO2T | O2 (CNS) | Breathing 100% O2 |

| 99 fsw (4 ATA) | Open-circuit diver | N2 | Breathing compressed air |

| 165 fsw (6 ATA) | Open-circuit diver | O2 (CNS) | Breathing compressed air |

fsw = feet of sea water.

This list does not include decompression sickness (DCS), which may occur at virtually any depth given the proper circumstances.

O2 toxicity in humans can be categorized into two major types: low pressure or chronic O2 toxicity, such as pulmonary toxicity, nonspecific cellular toxicity, organ damage and erythrocyte hemolysis; and high pressure or acute O2 toxicity, most commonly associated with CNS O2 toxicity.29,106 Chronic toxicity tends to occur when the Po2 exceeds 0.5 ATA for extended periods of time. People may be most familiar with retinal manifestations of O2 toxicity resulting in blindness of premature neonates. Prolonged exposure to elevated Po2, whether increased concentrations of oxygen inspired at atmospheric pressure or low concentrations of inspired oxygen at high ambient pressures, places humans at risk for pulmonary oxygen toxicity.44,45 It is characterized by decrease in pulmonary function, chest tightness, exertional dyspnea, and cough. Moderate to severe cases can involve pulmonary edema, hemorrhage, or death.42,44

The risk of CNS O2 toxicity is a function of both Po2 and exposure time, directly proportional to both: the greater the Po2, the greater the risk of HBO2 seizure.61 While the onset of seizures is usually in the vicinity of 2–3 ATA, the pressure at onset may be significantly lowered by coexisting conditions such as immersion, exercise, and respiratory acidosis due to moderate CO2 retention.69 1.9 ATA is a noticeable threshold for increased risk.69,77 Even at lower Po2 HBO2 seizures can occur particularly when combined with inert gases or carbon monoxide (CO).9,52 The most dramatic manifestation of CNS O2 toxicity is an HBO2-induced seizure. Additional effects of CNS O2 toxicity may also occur, including autonomic, motor, and cardiorespiratory signs and symptoms,40 such as bradycardia, hyperventilation, dyspnea, and altered cardiorespiratory neural reflexes.43

CNS O2 toxicity often presents acutely with little or no warning. Common signs and symptoms of CNS O2 toxicity are easily remembered using the mnemonic VENTID-C3,11,83:

Visual symptoms: tunnel vision, blurred vision, or decreased peripheral vision

Ear symptoms: tinnitus, roaring, pulsing sounds, or perceived sounds not from an external stimulus

Nausea: often with vomiting and headache

Twitching/Tingling: of extremities, facial muscles

Irritability: or any change in mental status such as confusion, agitation, anxiety, or undue fatigue

Dizziness: or clumsiness, loss of coordination

Convulsions: and death

Unfortunately many of these symptoms are not exclusive to O2 toxicity, and CNS O2 toxicity does not usually proceed through any predictable sequence of the above signs. Convulsions, the most serious effect of O2 toxicity due to its fatal potential if left untreated, may occur without warning or other accompanying signs.43,64 O2-induced seizures are characterized as generalized tonic-clonic seizures, though focal seizures may be the only neurological manifestation at times.64,99 During the seizure, the individual loses consciousness and convulses, usually progressing through both a tonic phase, in which all of the muscles are stimulated at once and lock the body into a state of rigidity, and a clonic phase, during which various muscles may cause violent thrashing motions.42,63 Brain activity is depressed during the postictal period, during which the individual is usually unconscious and subdued. This is usually followed by a period in which the individual is semiconscious and very restless, usually sleeping on and off for as little as 15 min or as long as an hour or more. Afterward he or she often becomes suddenly alert and complains of no more than fatigue, muscular soreness, and possibly a headache. After an O2 toxicity convulsion the individual usually remembers clearly the events up to the moment when consciousness was lost, but remembers nothing of the convulsion itself and little of the postictal phase.64

Convulsions unrelated to O2 toxicity may also occur in HBO2 environments and would present identically to a HBO2-induced seizure. It is critical to differentiate seizures resulting from hyperbaric oxygen from other etiologies, such as hypoglycemia. A convulsion due to O2 toxicity has little lasting effects, assuming the O2 pressure is immediately decreased; however, a hypoglycemic seizure unrecognized and untreated can be fatal. Unlike other tonic-clonic seizures, such as those seen in epilepsy, the danger of hypoxia during breathholding in the tonic phase of a HBO2-induced convulsion is minimized by the high Po2 in the brain and tissues; the source of the toxicity helps minimize hypoxia in the tissue during the seizure. A greater danger is posed by decreasing pressure in a chamber too quickly, which could potentially lead to a gas embolism. Since it would be difficult to differentiate between a postictal individual and an unconscious victim suffering from a cerebral arterial gas embolism, those experiencing O2-induced seizures in a hyperbaric chamber under pressure are generally kept at that same pressure until their convulsions cease. The Po2 in such cases is diminished solely by altering the breathing gas mixture. Patients suffering from O2-induced seizures generally have full recoveries within 24 h with no lasting effects, and it is unclear whether there is increased susceptibility to future incidents of O2 toxicity.11

The primary treatment for an O2-induced seizure is to lower the inspired Po2. This is accomplished by decreasing ambient pressure, switching to a breathing mixture with a lower percentage of O2, or both. Decreasing inspired Po2 may not immediately reverse the effects of CNS O2 toxicity and is not without risk. It is believed that the biochemical processes responsible for the toxicity remain in place for a period after the Po2 has been decreased in the ambient or inspired atmosphere. The individual experiencing the toxicity is not considered clear from danger until several minutes have passed after the Po2 has been decreased.34,83

In practice, the risk of acute O2 toxicity is often mitigated by interspersing short periods of air amid the pure O2 therapy at increased pressure commonly referred to as “air breaks.”11 It is a logical measure and some species such as insects have evolved discontinuous breathing in order to minimize risks of O2 toxicity even at 1 ATA.56 However, there is limited clinical data to support this practice.28 Some data supports the use of intermittent air breaks of 5–10 min to prolong HBO2 exposure prior to the onset of seizures.24 Yet, animal models demonstrate the possibility that the rapid decreases in Po2 may actually instigate seizure activity14 while appearing to be beneficial in preventing pulmonary oxygen toxicity.55 While intermittent exposures may decrease symptoms of CNS toxicity, measured molecular activities maintain prebreak levels, adding further confusion to the mechanism and success of air breaks during HBO2T.64 Therefore, understanding the mechanisms leading to HBO2 CNS toxicity can help to mitigate toxicity.

A search of current work on this subject including PubMed searches using the words “hyperbaric seizure” and “hyperbaric convulsion” yielded hundreds of peer-reviewed publications pertaining to HBO2 seizures. Several reviews and case series exist that emphasize the incidence of hyperbaric oxygen seizures. To the author’s knowledge there are no peer-reviewed review articles focusing on HBO2 seizures. A recent review on CNS oxygen toxicity was written in 2004.11 This review emphasizes primary research into the underlying mechanism by which increased Po2 causes HBO2 seizures in humans. While this review is not exhaustive, its goal is to summarize the majority of the existing knowledge on this topic by adequately sampling current research.

Mechanisms

Methods and models used to investigate the mechanisms of HBO2 toxicity on the nervous system must attempt to isolate two interdependent variables: 1) effects due to the increased ambient pressure on the CNS; and 2) effects due to the increased Po2. Small mammals serve as a good animal model for studying the cellular mechanisms of oxidative stress in the mammalian central nervous system.2 Therefore, many research studies have used mice, rats or other small rodents as models for research.68,117

The normobaric hyperoxic brain slice model is a common research model. It is a less desirable model to study the effects of oxygen toxicity on neuronal activity since most in vitro preparations of CNS tissue and cells use a 95% O2 control level during preparation. Humans inspiring normobaric air have relatively low Po2 in their brain, 35 mmHg or less, depending on the region.19 Murine brains have even lower ranges of Po2 in their brain, from 5 to 25 mmHg.126 Direct investigation using hyperbaric oxygen is preferred.

The use of in vitro electrophysiological methods to investigate the cellular mechanisms of O2 toxicity within a hyperbaric chamber has been limited by the challenges of working with or in a sealed pressure chamber and the mechanical disturbances experienced during tissue compression. Chamber design improvements have minimized these obstacles, allowing easier experimentation on animal models in ambient pressures around 5 ATA. Refinements in chamber design and using an ambient atmosphere of 100% helium have allowed intracellular experiments in rat brain slices. Electrophysiological studies on rat neurons have shown that increases in the Po2 in cerebral tissue lead to increased ROS production, followed by increased cortical EEG activity, and finally resulting in the onset of an O2-induced seizure activity.37,108

Effects on the CNS attributed to increased hydrostatic pressure, such as high-pressure nervous syndrome,37 tend to occur at very high pressures, ranging from 15 to 70 ATA. This results from compression of cerebral spinal fluid, circulation, and extracellular and intracellular fluid compartments of the CNS. Cellular mechanisms most likely involve synaptic and membrane dynamic responses to severe and fast changes in pressure.33,37 Therefore there is little evidence to suggest that hydrostatic pressure plays a significant role in HBO2 seizures, particularly at pressures involved with HBO2T less than 3 ATA.33

A relationship exists between high pressures and glycine receptors which indicates possible roles pressure plays on HBO2 seizures. High pressures have no effect on the maximum response of the glycine receptor to glycine; however, the half maximal effective concentration of glycine to its receptor and pressure become directly proportional at pressures above 100 ATA.101 While this seems less likely to be correlated with seizures occurring at 2–3 ATA, typical of HBO2T, it appears to be associated with high pressure neurological syndrome at much greater depths.37,101 The fact that glycine receptors are linked to myoclonic activity in mammals raises suspicion that conformational alterations at pressures less than 100 ATA may still participate in hyperbaric seizures to some degree at lower pressures.76

O2 under hyperbaric conditions behaves like a drug whose effects on metabolism exceed O2’s common role as a simple oxidizer.64 The molecular effects of increased Po2 during HBO2T affects neural networks in the CNS, resulting in overall network excitability.37 Much of the research into the molecular mechanisms of CNS O2 toxicity has focused on the neuroexcitatory and neuroinhibitory effects of neuroactive agents that results from elevated Po2. In general, mechanisms responsible for hyperbaric oxygen seizures can be categorized to include: ROS, inhibitory neurotransmitters, excitatory neurotransmitters, extracellular effects resulting in neurotransmitter dysregulation, and the imbalance of neuroprotective mechanisms.

Oxidative stress plays a key role in the mechanism of O2 toxicity. CNS O2 toxicity is an acute exposure to an oxidative environment disrupting neurological function. HBO2T greatly increases oxygen tension in the brain. Molecular O2 is a natural oxidative reagent in cellular biochemical pathways producing various free radicals. The mammalian CNS response to hyperoxia ranges from moderate, reversible changes in neural activity to violent seizures that may lead to irreversible motor deficits and death. In vitro experiments on rat brains exposed to HBO2 demonstrate that the Po2 is directly proportional to ROS formation in the tissue.108 The initial physiological response to hyperoxia is increased formation of superoxide and nitric oxide (NO) among other ROS.105 Prolonged exposure of neural tissue to HBO2 stresses antioxidant protective mechanisms. Oxidation of cellular components occurs due to the increased production of free radicals such as superoxide, hydrogen peroxide, hydroxyl radicals, and peroxynitrite. Oxidation of cellular metabolic reactants has therapeutic benefits,104,105 but also has negative effects. ROS can cause membrane weakening and metabolic dysregulation if normobaric O2 is not restored. It directly affects the various ionic conductances that regulate cell excitability. ROS are also reported to target neurotransmitter systems, altering chemical synaptic transmission.34,37 The network of ROS and antioxidants remains unclear and requires further research.123

The body scavenges oxidizing substances through enzymatic antioxidants such as superoxide dismutase for superoxide anions, catalase for hydrogen peroxide and nonenzymatic antioxidants such as reduced glutathione and vitamin E.105 Glutathione is regenerated by reaction with nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH). Therefore, sufficient levels of both glutathione and NADPH may be critical to defending against the increased level of oxidants.34

Nonenzymatic antioxidants should logically protect against HBO2 seizures. Vitamin E deficiency increases the risk of HBO2 seizures15; however, vitamin E failed to prevent HBO2 seizures.123 Another example is superoxide dismutase. Superoxide catalyzes superoxide anions to O2. Therefore, increased levels or activity of superoxide dismutase should decrease levels of ROS; hence, in theory, HBO2 seizures should be attentuated.57,93 However, in transgenic mice bred to overexpress human extracellular superoxide dismutase in the brain, inhibition of superoxide dismutase increased resistance to HBO2 seizures contrary to expectations. By inhibiting superoxide dismutase, the catalysis of superoxide into O2 (an in vivo antioxidant mechanism) is blocked, allowing superoxide levels to rise unopposed during HBO2 exposure. A fourfold decrease in seizures was measured in these mice pretreated with diethyldithiocarbonate, an inhibitor of human extracellular superoxide dismutase.88 The mechanism of this counterintuitive result appears to be the interaction between superoxide and other HBO2-induced reactants.

Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) has long been correlated with HBO2 seizures.120,121 Though GABA has been found to be lowered in mammalian neuronal synapses during HBO2 seizures when exposed to HBO2 in short intervals,58 there is evidence to suggest that the increased steady-state levels of GABA over longer intervals may be responsible for O2-induced seizures.46 In experiments involving transgenic mice with a HBO2-sensitivity phenotype, data suggests that the excitatory amino acids, such as aspartate and glutamate, play as important or more important roles in HBO2 seizures than GABA.81

Glutamate, an excitatory amino acid, is a potent, fast-acting neurotoxin in neuronal cultures. It has been shown to create morphological changes in mature cortical neurons within minutes of HBO2 exposure with neuronal degeneration occurring over the course of hours. In vitro experiments demonstrated that one-hundredth the intracellular concentration of glutamate during hyperbaric exposures critically damages cortical neurons.27 Decreased glutamate metabolism during HBO2 exposure sensitizes neural networks to HBO2 seizures.72 Conflicting evidence exists as to the degree of change in excitatory amino acids prior to and during HBO2 seizures. Recent evidence suggests that O2-induced seizures may result from an imbalance of excitatory and inhibitory synaptic neurotransmitters, glutamate and GABA, respectively. The imbalance results in a greater relative decrease in presynaptic release of GABA than of glutamate,38 which suggests that the relative increase of excitatory neurotransmitters with respect to inhibitory neurotransmitters may be a basic mechanism of HBO2 seizures.

Extracellular mediators of physiological functions such as NO also play a role in HBO2 seizures. NO has been implicated in neurotoxicities resulting from excess glutamate stimulation in cultures of rat cortex, striatum, and hippocampus.36 NO activity appears to increase the ratio of excitatory to inhibitory neurotransmitters which increases the probability of O2 seizures.38 Neurons containing nitric oxide synthase (NOS), widespread throughout the cortex, react to HBO2 by increasing NO production.1,82 In HBO2 environments, NO acutely decreases cerebral blood flow but then increases regional cerebral blood flow after prolonged HBO2 exposure preceding neuronal excitation.39,51 NO has been associated with changes in cerebral blood flow and HBO2 seizures.98 Cerebral blood flow is indirectly proportional to the time of onset of HBO2 seizures in animal models. Effects of NO with respect to HBO2 seizures is diagrammed in Fig. 1.68,125 When interstitial NO, aspartate, glutamate, and GABA were measured in vivo in anesthetized rats under HBO2 conditions with respect to blood flow and EEG activity of the striatum, increases in NO metabolites and blood preceded spikes in EEG activity and seizures. Thus, it was concluded that HBO2-stimulated neuronal NO production promoted an imbalance between excitatory (glutamate) and inhibitory (GABA) synaptic activity. This in turn contributes to O2-induced seizures in rats.38

Fig. 1.

Schematic of extracellular interactions produced by increased Po2 that result in CNS HBO2 seizures. Increased cerebral blood flow (CBF) results in decreased time to onset of HBO2 seizures (tHBO2S). Extracellular substances such as phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors (PDE-5i), 7-NI, N-nitro-L-arginine (NNA, a NOS inhibitor), and daurisoline (DSL, a calcium channel blocker) affect CBF. Dotted line = lessened action (−). Bold line = increased action (+). Large arrow = correlation.

The molecular mechanisms involved in HBO2 seizures are complex. An imbalance of the redundant molecular protective mechanisms that humans have evolved to counter deleterious effects of increased Po2, as depicted in Fig. 2, appears to lead to HBO2 seizures. Elevated Po2 causes concomitant saturation of the redundant antioxidant systems evolved to protect humans. Though individual reactions are well-described, the network of interactions between the various reactions are not well-described.123 Increased Po2 saturates enzymes and maximizes rates of reactions designed to protect against reactive species. For example increased Po2 saturates superoxide dismutase, increasing superoxide. Superoxide anions can react with NO to yield nitrate (NO3), a neurologically inert substance; however, the rate of this reaction does not appear sufficient to eliminate risks of CNS O2 toxicity at sufficiently high Po2 over time.

Fig. 2.

Schematic of some synaptic changes produced by increased Po2 and resulting in CNS HBO2 seizures. The human body has several equilibrated safeguards that minimize effects of ROS on neural networks. Increased Po2 appears to saturate protective enzymes and unfavorably shift protective reactions in the direction of neural network overstimulation, resulting in HBO2 seizures. NT = neurotransmitter; AP = action potential. Dotted line = lessened action. Bold line = increased action.

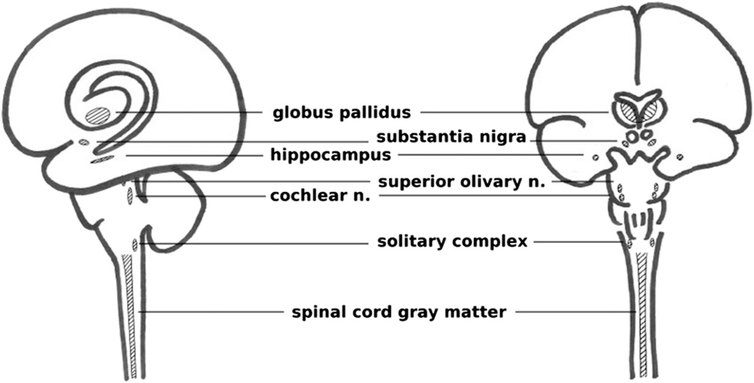

A long-standing question regarding hyperbaric oxygen seizures is whether certain regions of the CNS are more susceptible to HBO2.112 Neuroanatomic studies have shown that centrally located regions of the brain are most affected by exposure to HBO2, including: the globus pallidus, substantia nigra, superior olivary nucleus, ventral cochlear nucleus, limbic structures, amygdala, and the spinal cord gray matter, diagrammed in Fig. 3.109,111 It is worth noting that the globus pallidus and substantia nigra are brain regions also susceptible to CO toxicity. Single-cell electrophysiology experiments have shown that hippocampus and brain stem neurons are disproportionately sensitive to increased Po2 in surrounding tissues when exposed to HBO2.50,65 The anatomical localization of neuroactive agents and their effects may also explain anatomical distribution of increased O2 sensitization.37,90

Fig. 3.

Brain regions most likely involved in HBO2-induced seizures. Certain regions of the CNS (including the solitary complex in the dorsal medulla, hippocampus, globus pallidus, substantia nigra, superior olivary nucleus, ventral cochlear nucleus, and spinal cord gray matter) appear more susceptible than others to these effects. Note the central nature of these regions, anatomically similar to CO susceptible regions.

For example, at HBO2 levels of 3–5 ATA, regional cerebral blood flow in the substantia nigra decreased for 30 min but gradually returned to normal levels preceding EEG spikes.33 Acute exposure to HBO2 results in an increased firing rate of specific neurons, particularly carbon dioxide (CO2)/proton-chemosensitive neurons, which are coupled via gap junctions and baroreceptors, in the cerebral and cerebella cortex that demonstrate a high sensitivity to HBO2, chemical oxidants, and neurotransmitters.33,40,80

Certain conditions heighten one’s risk to CNS toxicity and HBO2 seizures. Hypercapnia elevates the risk of O2 toxicity.100,119 Hypercapnic-induced intracellular acidosis makes cells more susceptible to ROS. CO2 causes cerebral vasodilation, increases cerebral blood flow, and heightens CNS exposure to elevated Po2. Neurons in the solitary complex are particularly susceptible to increased Pco2 and Po2, resulting in an increased rate of excitatory firing. Increased Pco2 in HBO2 environments may occur by: 1) a decrease in CO2-carrying capacity of venous hemoglobin since venous hemoglobin may be saturated with O2; 2) alveolar hypoventilation and CO2 retention; and 3) CO2-contamination due to inadequate scrubbing of recirculated breathing gas.37,100 Exercise also increases the risk of CNS O2 toxicity, likely related to increased cerebral blood flow and metabolic rate.2,66 CO toxicity significantly increases the risk of HBO2 seizures.52,97

Current preventative measures to counter O2 toxicity include minimizing exposure times to increased Po2, decreasing the inspired Po2, or inserting periods of air breaks.11 There is evidence in animal models to suggest that repeated HBO2 exposures increases risk of seizures.6,48,75 Data support brain derived neurotrophic factor, 7-nitroindozol (7-NI), and NO as potential mechanisms for sensitization to repeated HBO2 seizures.20,25,26,60 Yet there appears to be some randomization to susceptibility. An individual may repeat the same exposure conditions and suffer from CNS O2 toxicity for no apparent reason.11

Since the mechanism of CNS O2 toxicity remains uncertain, there is a paucity of prophylactic measures to prevent it. Certain factors are known to mitigate an individual’s susceptibility to CNS O2 toxicity. Numerous prophylactic treatments for HBO2-induced seizures have been shown to be effective through in vivo experiments involving rats and mice.

NO is an important mediator of CNS O2 toxicity.12 Inhibition of NOS with nitroarginine showed similar prevention of CNS toxicity and O2-induced seizures in both transgenic and nontransgenic mice.23,88,115 The potency of NOS inhibitors in preventing CNS O2 toxicity is indirectly proportional to the disassociation constant of the inhibitor and NOS.36 Intraperitoneal administration of GABA proved effective in protecting rats from O2-induced seizures. Since GABA does not cross the blood brain barrier, the mechanism of its protection is speculated to be an osmotic effect drawing a metabolite of GABA out of the brain.46 Pretreatment of rats exposed to HBO2 conditions with 7-NI slowed the rate of decline in GABA levels, decreased the glutamate/GABA excitotoxicity index, and minimized EEG spikes associated with O2 toxicity.38

MK-801, an NMDA receptor antagonist, has been shown to prevent EEG spikes associated with O2 toxicity and O2-induced seizures.37,39 Other substances such as disulfiram (Antabuse)21,47,117 and antioxidants also appear to delay or diminish O2 toxicity in the brain.34,37 Additional agents that hasten the onset or increase incidence of HBO2 seizures include: adrenocortical hormones, epinephrine, hyperthermia, norepinephrine, thyroid hormones, vitamin E deficiency,15 brain derived neurotrophic factor,25 misonidazole,54 pseudoephedrine,91 hyperglycemia,4 and phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors.41 Additional agents that delay the onset or attenuate HBO2 seizures include: N-nitro-L-arginine (NNA),22,115 daurisoline (DSL),115 acclimitization to hypoxia, antioxidants,74 chlorpromazine, reserpine, starvation,31 ganglionic blocking drugs and anti-epileptics,71 glutathione,62 hypothermia, hypothyroidism, insulin,4 CoQ10 and carnitine,7 acetazolamide,119 excitatory amino acid antagonists,30 aminooxyacetic acid (AAOA),5,35 delta-sleep-inducing peptide (DSIP),78 beta-carotene,10 vigabatrin,53,110 propionyl-L-carnitine,8 leukotriene and PAF inhibitors,73 carbamazepine,95 propranolol,117 caffeine,13 Dilantin,116 and lithium.103 Some agents that one would expect to affect HBO2 seizures, such as allopurinol and pyridoxine, did not. 57,103,114

Potential Areas of Research

A significant amount of research has been conducted on the mechanisms of CNS O2 toxicity, but few clinical studies or trials exist as to how to prevent it. There are few attempts in applying existing results to testing prophylactic treatments for humans. This is likely due to the potential difficulties of such studies. A search (using keywords “hyperbaric oxygen,” “hyperbaric oxygen therapy,” and “oxygen toxicity”) shows over 50 active NIH-funded clinical trials pertaining to HBO2 and only one pertaining to CNS O2 toxicity.86 Potentially beneficial, “off-the-shelf” medications (FDA approved medication or nonregulated supplement) could be trialed for their efficacy in preventing or reducing the incidence of HBO2-induced CNS toxicity, including: disulfiram (an inhibitor of alcohol dehydrogenase with some evidence of success in preventing HBO2 seizures in animal models, approved for use in the treatment of alcohol abuse),34 acamprosate (a glutamate receptor modulator approved for use in the treatment of alcohol abuse), and vitamin E (a nonenzymatic antioxidant sold as a supplement).

In a clinical setting, an HBO2T center would have no less than 1000 treatments per year. If we assume that treatments can be taken as independent events, i.e., there is no correlation between two treatments on the same person or different individuals with the same preexisting conditions, then we can use all 1000 treatments as individual events upon which we can base our design. This is purely an assumption in order to minimize a sample size calculation. An O2-induced seizure is the most easily quantifiable endpoint for measuring CNS oxygen toxicity, although any signs, symptoms, or composite of the two could be used.

The frequency of an oxygen-induced seizure may be approximated at 1 in 10,000 treatments, with the literature citing a wide range from 2 in 100,000 to 1 in 1000.97,118,124 One study estimates the probability of a CNS toxicity event as low as 1.7% over the period of a 4-h dive with Po2 = 1.4 ATA.102

A prospective study would seek to decrease the frequency of oxygen-induced seizures by a given factor as a result of implementing a prophylactic treatment, such as disulfiram or antioxidants. Using STATA version 9.0 for Windows (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX) the sample size needed to conduct a definitive randomized trial demonstrating a tenfold reduction in the frequency of hyperbaric oxygen-induced seizures, from 0.0001 to 0.00001, using a two-sided 0.05 level test with 80% power is 85,218, assuming equal allocation to the experimental and control arms. It could take a single hyperbaric facility over a decade to accrue enough data to execute a definitive study of this nature. This information necessitates that randomized clinical studies investigating CNS oxygen toxicity be multicenter studies with endpoints more than just seizures used to identify oxygen-toxicity.

Further, agents that mitigate O2-induced seizures may also negatively affect the therapeutic benefits of HBO2T, thus adding to the complexity of the study. For example, any antioxidant that can effectively eliminate ROS during HBO2T may eliminate their role in causing HBO2 seizures, but it would also eliminate the benefits ROS play in promoting wound healing and postischemic tissue survival.105 This would require a long time, a great deal of resources, and/or multiple institutions to accomplish. It is unlikely for a research study of this magnitude to occur. Therefore, continued basic science research may be the best alternative to investigate CNS toxicity.

The advent of nanoscale devices allows for more precise delivery and investigation of mediators of O2-induced seizures such as NO.96 The excitatory firing rate of dorsal medullary neurons due to HBO2 can be mimicked by the presence of pro-oxidants at normobaric conditions,37 demonstrating that normobaric experimentation might be feasible to shed light on O2’s toxic effects under pressure. Precise delivery of ROS or neurotransmitter mediators of CNS toxicity would allow for detailed experimental designs at the molecular, neuronal level in normal models at normobaric conditions. This may shed light on unanswered questions such as whether the effects of hyperoxia and the resulting ROS are presynaptic or postsynaptic in origin, currently an unanswered question. Normobaric models of the effects of HBO2 would also open the door to the wide array of experimental tools that otherwise would not be feasible to perform in hyperbaric chambers. Finally, as data and proposed theories of O2 toxicity increase, this area of research becomes primed for computational simulations. Current prediction models have shown that it is very difficult to build a prediction model for mild hyperoxia given the current data.102 However, computational analysis and simulations of molecular signaling interactions might enable existing and otherwise conflicting theories to coexist within a new model for CNS O2 toxicity. This would provide a physiologically based model with greater precision and accuracy. Models of complex biological systems such as T lymphocyte activation demonstrate the feasibility of this approach.59

Summary

The benefits of HBO2 come with the risk of CNS O2 toxicity. The exact mechanism of O2 toxicity remains a mystery. Prophylactic measures and treatment for CNS O2 toxicity remain centered on limiting exposure to high Po2. Better understanding of molecular mechanisms causing O2 toxicity can lead to prophylactic therapies for consideration in clinical trials. There is increasing need for research on the systemic interactions of the multiple players involved in HBO2 seizures in order to better understand how they occur and how to prevent them.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allen BW, Demchenko IT, Piantadosi CA. Two faces of nitric oxide: implications for cellular mechanisms of oxygen toxicity. J Appl Physiol. 2009. February 106(2):662–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arieli R Oxygen toxicity is not related to mammalian body size. Comp Biochem Physiol A Comp Physiol. 1988; 91(2):221–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arieli R, Arieli Y, Daskalovic Y, Eynan M, Abramovich A. CNS oxygen toxicity in closed-circuit diving: signs and symptoms before loss of consciousness. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2006; 77(11):1153–1157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beckman DL, Crittenden DJ, Overton 3rd DH, Blumenthal SJ. Influence of blood glucose on convulsive seizures from hyperbaric oxygen. Life Sci. 1982; 31(1):45–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beckman DL, Iams SG. Protection against high-pressure oxygen seizures by amino-oxyacetic acid. Undersea Biomed Res. 1978. September 5(3):253–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benjamini Y, Bitterman N. Statistical approach to the analysis of sensitivity to CNS oxygen toxicity in rats. Undersea Biomed Res. 1990. May 17(3):213–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bertelli A, Giovannini L, Mian M, Spaggiari PG. Protective action of propionyl-L-carnitine on toxicity induced by hyperbaric oxygen. Drugs Exp Clin Res. 1990; 16(10):527–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bertelli A, Bertelli AA, Giovannini L, Spaggiari P. Protective synergic effect of coenzyme Q10 and carnitine on hyperbaric oxygen toxicity. Int J Tissue React. 1990; 12(3):193–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bitterman N, Laor A, Melamed Y. CNS oxygen toxicity in oxygen-inert gas mixtures. Undersea Biomed Res. 1987. November 14(6):477–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bitterman N, Melamed Y, Ben-Amotz A. Beta-carotene and CNS oxygen toxicity in rats. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1994 Mar 76(3):1073–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bitterman N CNS oxygen toxicity. Undersea Hyperb Med. 2004; 31(1):63–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bitterman N, Bitterman H. L-arginine-NO pathway and CNS oxygen toxicity. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1998; 84(5):1633–1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bitterman N, Schaal S. Caffeine attenuates CNS oxygen toxicity in rats. Brain Res. 1995; 696(1–2):250–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bleiberg B, Kerem D. Central nervous system oxygen toxicity in the resting rat: postponement by intermittent oxygen exposure. Undersea Biomed Res. 1988. September 15(5):337–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Block ER. Effect of superoxide dismutase and succinate on the development of hyperbaric oxygen toxicity. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1977. July 48(7):645–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boerema I, Kroll JA, Meijne NG, Lobin E, Kroom B, Huskies JW. High atmospheric pressure as an aid to cardiac surgery. Arch Chir Neerl. 1956; 8:193–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Camporesi EM, Bosco G. Mechanisms of action of hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Undersea Hyperb Med. 2014; 41(3):247–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Camporesi EM. Side effects of hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Undersea Hyperb Med. 2014; 41(3):253–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carreau A, El Hafny-Rahbi B, Matejuk A, Grillon C, Kieda C. Why is the partial oxygen pressure of human tissues a crucial parameter? Small molecules and hypoxia. J Cell Mol Med. 2011; 15(6):1239–1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chavko M, Auker CR, McCarron RM. Relationship between protein nitration and oxidation and development of hyperoxic seizures. Nitric Oxide. 2003. August 9(1):18–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chavko M, Braisted JC, Harabin AL. Attenuation of brain hyperbaric oxygen toxicity by fasting is not related to ketosis. Undersea Hyperb Med. 1999; 26(2):99–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chavko M, Braisted JC, Harabin AL. Effect of MK-801 on seizures induced by exposure to hyperbaric oxygen: comparison with AP-7. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1998; 151(2):222–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chavko M, Braisted JC, Outsa NJ, Harabin AL. Role of cerebral blood flow in seizures from hyperbaric oxygen exposure. Brain Res. 1998; 791(1–2):75–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chavko M, McCarron RM. Extension of brain tolerance to hyperbaric O2 by intermittent air breaks is related to the time of CBF increase. Brain Res. 2006; 1084(1):196–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chavko M, Nadi NS, Keyser DO. Activation of BDNF mRNA and protein after seizures in hyperbaric oxygen: implications for sensitization to seizures in re-exposures. Neurochem Res. 2002; 27(12):1649–1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chavko M, Xing G, Keyser DO. Increased sensitivity to seizures in repeated exposures to hyperbaric oxygen: role of NOS activation. Brain Res. 2001; 900(2):227–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choi DW, Maulucci-Gedde M, Kriegstein AR. Glutamate neurotoxicity in cortical cell culture. J Neurosci. 1987. February 7(2):357–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clark JM. Extension of oxygen tolerance by interrupted exposure. Undersea Hyperb Med. 2004; 31(2):195–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clark JM. The toxicity of oxygen. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1974;110(6, Pt 2): 40–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Colton CA, Colton JS. Blockade of hyperbaric oxygen induced seizures by excitatory amino acid antagonists. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1985; 63(5):519–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.D’Agostino DP, Pilla R, Held HE, Landon CS, Puchowicz M, et al. Therapeutic ketosis with ketone ester delays central nervous system oxygen toxicity seizures in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2013; 304(10):R829–R836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.D’Agostino Dias M, Fontes B, Poggetti RS, Birolini D. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy: types of injury and number of sessions–a review of 1506 cases. Undersea Hyperb Med. 2008; 35(1):53–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cellular Daniels S. and neurophysiological effects of high ambient pressure. Undersea Hyperb Med. 2008; 35(1):11–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davis JC, Hunt TK, editors. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Bethesda (MD): Undersea Medical Society, Inc.; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davison AJ. Aminooxyacetic acid provides transient protection against seizures induced by hyperbaric oxygen. Brain Res. 1983; 276(2):384–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dawson VL, Dawson TM, Bartley DA, Uhl GR, Snyder SH. Mechanisms of nitric oxide-mediated neurotoxicity in primary brain cultures. J Neurosci. 1993; 13(6):2651–2661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dean JB, Mulkey DK, Garcia AJ, Putnam RW, Henderson RA. Neuronal sensitivity to hyperoxia, hypercapnia, and inert gases at hyperbaric pressures. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2003; 95:883–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Demchenko IT, Piantadosi CA. Nitric oxide amplifies the excitatory to inhibitory neurotransmitter imbalance accelerating oxygen seizures. Undersea Hyperb Med. 2006; 33(3):169–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Demchenko IT, Boso AE, O’Neill TJ, Bennett PB, Piantadosi CA. Nitric oxide and cerebral blood flow responses to hyperbaric oxygen. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2000; 88(4):1381–1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Demchenko IT, Gasier HG, Zhilyaev SY, Moskvin AN, Krivchenko AI, et al. Baroreceptor afferents modulate brain excitation and influence susceptibility to toxic effects of hyperbaric oxygen. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2014; 117(5):525–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Demchenko IT, Ruehle A, Allen BW, Vann RD, Piantadosi CA. Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors oppose hyperoxic vasoconstriction and accelerate seizure development in rats exposed to hyperbaric oxygen. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2009 April 106(4):1234–1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Domachevsky L, Rachmany L, Barak Y, Rubovitch V, Abramovich A, Pick CG. Hyperbaric oxygen-induced seizures cause a transient decrement in cognitive function. Neuroscience. 2013; 247:328–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Donald K Oxygen and the diver West Palm Beach (FL): Best Publishing Co.; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eckenhoff RG, Dougherty JH Jr., Messier AA, Osborne SF, Parker JW. Progression of and recovery from pulmonary oxygen toxicity in humans exposed to 5 ATA air. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1987. July 58(7):658–667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eynan M, Krinsky N, Biram A, Arieli Y, Arieli R. A comparison of factors involved in the development of central nervous system and pulmonary oxygen toxicity in the rat. Brain Res. 2014; 1574:77–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Faiman MD, Nolan RJ, Baxter CF, Dodd DE. Brain gamma-aminobutyric acid, glutamic acid decarboxylase, glutamate, and ammonia in mice during hyperbaric oxygenation. J Neurochem. 1977. April 28(4):861–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Faiman MD, Nolan RJ, Oehme FW. Effect of disulfiram on oxygen toxicity in beagle dogs. Aerosp Med. 1974. Jan 45(1):29–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fenton LH, Robinson MB. Repeated exposure to hyperbaric oxygen sensitizes rats to oxygen-induced seizures. Brain Res. 1993; 632(1–2): 143–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fock AW. Analysis of recreational closed-circuit rebreather deaths 1998–2010. Diving Hyperb Med. 2013; 43:78–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Garcia AJ 3rd, Putnam RW, Dean JB. Hyperbaric hyperoxia and normobaric reoxygenation increase excitability and activate oxygen-induced potentiation in CA1 hippocampal neurons. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2010;109(3):804–819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gutsaeva DR, Moskvin AN, Zhiliaev SIu, Kostkin VB, Demchenko IT. [Nitric oxide and carbon dioxide in neurotoxicity induced by oxygen under pressure]. [Article in Russian]. Ross Fiziol Zh Im I M Sechenova. 2004; 90(4):428–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hampson NB, Simonson SG, Kramer CC, Piantadosi CA. Central nervous system oxygen toxicity during hyperbaric treatment of patients with carbon monoxide poisoning. Undersea Hyperb Med. 1996. Dec 23(4):215–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hall AA, Young C, Bodo M, Mahon RT. Vigabatrin prevents seizure in swine subjected to hyperbaric hyperoxia. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2013; 115(6):861–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Harris JW, Shrieve DC. Misonidazole (Ro-07–0582) sensitizes mice to convulsions induced by hyperbaric oxygen or pentylenetetrazol. Br J Radiol. 1978; 51(612):1024–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hendricks PL, Hall DA, Hunter WL Jr., Haley PJ. Extension of pulmonary O2 tolerance in man at 2 ATA by intermittent O2 exposure. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol. 1977; 42(4):593–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hetz SK, Bradley TJ. Insects breathe discontinuously to avoid oxygen toxicity. Nature. 2005; 433(7025):516–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hoppe SA, Terrell DJ, Gottlieb SF. The effect of allopurinol on oxygen-induced seizures in mice. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1984; 55(10): 927–930. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hori S Study on hyperbaric oxygen-induced convulsion with particular reference to gamma-aminobutyric acid in synaptosomes. J Biochem. 1982; 91(2):443–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jacobi Medical Center Hyperbaric Treatments [Internet]. Jacobi Medical Center, Bronx, NY; c2015 [cited 2015 Dec 15]. Available from: http://www.jacobi-hyperbaric.com/html/hyperbaric-treatments.html. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jellestad FK, Gundersen H. Behavioral effects of 7-nitroindazole on hyperbaric oxygen toxicity. Physiol Behav. 2002; 76(4–5):611–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jenkinson SG. Oxygen toxicity. New Horiz. 1993; 1(4):504–511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jenkinson SG, Jordan JM, Duncan CA. Effects of selenium deficiency on glutathione-induced protection from hyperbaric hyperoxia in rat. Am J Physiol. 1989; 257(6, Pt 1):L393–L398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kandel ER, Schwartz JH, Jessell TM. Principles of neuroscience, 4th ed. Columbus (OH): McGraw-Hill; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kindwall EP, Whalen HT. Hyperbaric medicine practice, 2nd ed Flagstaff (AZ): Best Publishing Company; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 65.King GL, Parmentier JL. Oxygen toxicity of hippocampal tissue in vitro. Brain Res. 1983; 260(1):139–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Koch AE, Koch I, Kowalski J, Schipke JD, Winkler BE, et al. Physical exercise might influence the risk of oxygen-induced acute neurotoxicity. Undersea Hyperb Med. 2013; 40(2):155–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kranke P, Bennett MH, Martyn-St James M, Schnabel A, Debus SE, Weibel S. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for chronic wounds. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015; 6:CD004123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kurasako T, Takeda Y, Hirakawa M. Increase in cerebral blood flow as a predictor of hyperbaric oxygen-induced convulsion in artificially ventilated rats. Acta Med Okayama. 2000; 54(1):15–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lambertsen CJ. Definition of Oxygen Tolerance in Man [Internet]. Institute For Environmental Medicine, University of Pennsylvania Medical Center Philadelphia, PA 19104–6068; Naval Medical Research and Development Command and Office of Naval Research 31 December 1987. C2015 [cited 2015 Dec 12] Available from: http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a239247.pdf.

- 70.Lee CH, Lee L, Yang KJ, Lin TF. Top-cited articles on hyperbaric oxygen therapy published from 2000 to 2010. Undersea Hyperb Med. 2012; 39(6):1089–1098. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lembeck F, Beubler E. Convulsions induced by hyperbaric oxygen: inhibition by phenobarbital, diazepam and baclofen. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1977; 297(1):47–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li Q, Guo M, Xu X, Xiao X, Xu W, et al. Rapid decrease of GAD 67 content before the convulsion induced by hyperbaric oxygen exposure. Neurochem Res. 2008; 33(1):185–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lin Y, Jamieson D. Are leukotrienes or PAF involved in hyperbaric oxygen toxicity? Agents Actions. 1993; 38(1–2):66–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lin Y, Jamieson D. Effects of antioxidants on oxygen toxicity in vivo and lipid peroxidation in vitro. Pharmacol Toxicol. 1992; 70(4):271–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Liu W, Li J, Sun X, Liu K, Zhang JH, et al. Repetitive hyperbaric oxygen exposures enhance sensitivity to convulsion by upregulation of eNOS and nNOS. Brain Res. 2008; 1201:128–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lynch JW. Molecular structure and function of the glycine receptor chloride channel. Physiol Rev. 2004; 84(4):1051–1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mayevsky A, Shaya B. Factors affecting the development of hyperbaric oxygen toxicity in the awake rat brain. J Appl Physiol. 1980; 49(4): 700–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mendzheritskiĭ AM, Lysenko AV, Uskova NI, Sametskiĭ EA. [The mechanism of the anticonvulsive effect of the delta sleep-inducing peptide under conditions of elevated oxygen pressure]. [Article in Russian, Abstract in English]. Fiziol Zh Im I M Sechenova. 1996; 82(1):59–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Medicare definition and indications for hyperbaric oxygen therapy [Internet] c2015 [cited 2015 Nov 11]. Available from: https://www.medicare.gov/coverage/hyperbaric-oxygen-therapy.html.

- 80.Mialon P, Gibey R, Bigot JC, Barthelemy L. Changes in striatal and cortical amino acid and ammonia levels of rat brain after one hyperbaric oxygen-induced seizure. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1992; 63(4): 287–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mialon P, Joanny P, Gibey R, Cann-Moisan C, Caroff J, et al. Amino acids and ammonia in the cerebral cortex, the corpus striatum and the brain stem of the mouse prior to the onset and after a seizure induced by hyperbaric oxygen. Brain Res. 1995; 676(2):352–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Moskvin AN, Zhilyaev SY, Sharapov OI, Platonova TF, Gutsaeva DR, et al. Brain blood flow modulates the neurotoxic action of hyperbaric oxygen via neuronal and endothelial nitric oxide. Neurosci Behav Physiol. 2003; 33(9):883–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Naval Sea Systems Command, United States Department of the Navy. Navy diving manual, 5th ed. Washington (DC): U.S. Government Printing Office; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 84.National Coverage Determination (NCD) for Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy. (20.29), Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services [Internet] c2015 [cited 2015 Dec 12]. Available from: www.cms.gov.

- 85.Nelson LS, Lewin NA, Howland MA, Hoffman RS, Goldfrank LR, Flomenbaum NE. Goldfrank’s toxicologic emergencies, 9th ed New York (NY): McGraw Hill; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 86.National Institutes of Health, National Library of Medicine [Internet] C2015 [cited 2015 Dec 1]. Available from: clinicaltrials.gov.

- 87.Olivero M Hospitals Tout Benefits of Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy [Internet]. 6 Oct 2014 [cited 2015 Nov 11]. Available from: http://www.usnews.com/news/articles/2014/10/06/hospitals-tout-benefits-of-hyperbaric-oxygen-therapy.

- 88.Oury TD, Ho YS, Piantadosi CA, Crapo JD. Extracellular superoxide dismutase, nitric oxide, and central nervous system O2 toxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992; 89(20):9715–9719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Pace N, Strajman E, Walker EL. Acceleration of carbon monoxide elimination in man by high pressure oxygen. Science. 1950; 111(2894): 652–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Piantadosi CA, Tatro LG. Regional H2O2 concentration in rat brain after hyperoxic convulsions. J Appl Physiol. 1990. November 69(5):1761–1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Pilla R, Held HE, Landon CS, Dean JB. High doses of pseudoephedrine hydrochloride accelerate onset of CNS oxygen toxicity seizures in unanesthetized rats. Neuroscience. 2013; 246:391–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Plafki C, Peters P, Almeling M, Welslau W, Busch R. Complications and side effects of hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2000; 71(2):119–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Puglia CD, Loeb GA. Influence of rat brain superoxide dismutase inhibition by diethyldithiocarbamate upon the rate of development of central nervous system oxygen toxicity. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1984; 75(2):258–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Raman G, Kupelnick B, Chew P, Lau J. A Horizon Scan: Uses of Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2006 Oct 05. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK299143/. [PubMed]

- 95.Reshef A, Bitterman N, Kerem D. The effect of carbamazepine and ethosuximide on hyperoxic seizures. Epilepsy Res. 1991; 8(2):117–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Roche CJ, Dantsker D, Samuni U, Friedman JM. Nitrite reductase activity of sol-gel-encapsulated deoxyhemoglobin. Influence of quaternary and tertiary structure. J Biol Chem. 2006; 281(48):36874–36882 Epub 2006 Sep 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sanders RW, Katz KD, Suyama J, Akhtar J, O’Toole KS, et al. Seizure during hyperbaric oxygen therapy for carbon monoxide toxicity: a case series and five-year experience. J Emerg Med. 2012; 42(4):e69–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sato T, Takeda Y, Hagioka S, Zhang S, Hirakawa M. Changes in nitric oxide production and cerebral blood flow before development of hyperbaric oxygen-induced seizures in rats. Brain Res. 2001; 918(1–2):131–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Seckin M, Gurgor N, Beckmann YY, Ulukok MD, Suzen A, Basoglu M. Focal status epilepticus induced by hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Neurologist. 2011; 17(1):31–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Seidel R, Carroll C, Thompson D, Diem RG, Yeboah K, et al. Risk factors for oxygen toxicity seizures in hyperbaric oxygen therapy: case reports from multiple institutions. Undersea Hyperb Med. 2013; 40(6):515–519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Shelton CJ, Doyle MG, Price DJ, Daniels S, Smith EB. The effect of high pressure on glycine- and kainate-sensitive receptor channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Proc Biol Sci. 1993; 254(1340):131–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Shykoff B Incidence of CNS oxygen toxicity with mild hyperoxia: a literature and data review. Panama City (FL): Navy Experimental Dive Unit; 2013; TA 12–03 NEDU TR 13–03. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Singh AK, Banister EW. Relative effects of hyperbaric oxygen on cations and catecholamine metabolism in rats: protection by lithium against seizures. Toxicology. 1981; 22(2):133–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Thom SR. Hyperbaric oxygen – its mechanisms and efficacy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011; 127(Suppl 1):131S–141S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Thom SR. Oxidative stress is fundamental to hyperbaric oxygen therapy. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2009; 106(3):988–995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Thomson L, Paton J. Oxygen toxicity. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2014; 15(2): 120–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Tibbles PM, Edelsberg JS. Hyperbaric-oxygen therapy. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(25):1642–1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Torbati D, Church DF, Keller JM, Pryor WA. Free radical generation in the brain precedes hyperbaric oxygen-induced convulsions. Free Radic Biol Med. 1992; 13(2):101–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Torbati D, Lambertsen CJ. Regional cerebral metabolic rate for glucose during hyperbaric oxygen-induced convulsion. Brain Res. 1983; 279(1–2): 382–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Tzuk-Shina T, Bitterman N, Harel D. The effect of vigabatrin on central nervous system oxygen toxicity in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 1991; 202(2):171–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Vion-Dury J, LeGal La Salle G, Rougier I, Papy JJ. Effects of hyperbaric and hyperoxic conditions on amygdala-kindled seizures in rat. Exp Neurol. 1986; 92(3):513–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Voronov IB. Brain structures and origin of convulsions caused by high oxygen pressure (HOP). Int J Neuropharmacol. 1964; 3:279–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Walker J Hyperbaric oxygen therapy gets more popular as unapproved treatment: use of HBOT to treat autism, brain injury is growing despite a lack of conclusive evidence [Internet]. Wall Street Journal; 5 January 2015. [cited 2015 Nov 11]. Available from: http://www.wsj.com/articles/hyperbaric-oxygen-therapy-gets-more-popular-as-unapproved-autism-treatment-1420496506.

- 114.Walter FG, Chase PB, Fernandez MC, Cameron D, Roe DJ, Wolfson M. Pyridoxine does not prevent hyperbaric oxygen-induced seizures in rats. J Emerg Med. 2006; 31(2):135–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Wang WJ, Ho XP, Yan YL, Yan TH, Li CL. Intrasynaptosomal free calcium and nitric oxide metabolism in central nervous system oxygen toxicity. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1998; 69(6):551–555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Weaver LK. Phenytoin sodium in oxygen-toxicity-induced seizures. Ann Emerg Med. 1983; 12(1):38–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Whelan HT, Bajic DM, Karlovits SM, Houle JM, Kindwall EP. Use of cytochrome-P450 mono-oxygenase 2 E1 isozyme inhibitors to delay seizures caused by central nervous system oxygen toxicity. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1998; 69(5):480–485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Witucki P, Duchnick J, Neuman T, Grover I. Incidence of DCS and oxygen toxicity in chamber attendants: a 28-year experience. Undersea Hyperb Med. 2013; 40:345–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Wood CD. Acetazolamide and CO2 in hyperbaric oxygen toxicity. Undersea Biomed Res. 1982; 9(1):15–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Wood JD. The role of gamma-aminobutyric acid in the mechanism of seizures. Prog Neurobiol. 1975; 5(1):77–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Wood JD, Watson WJ, Murray GW. Correlation between decreases in brain gamma-aminobutyric acid levels and susceptibility to convulsions induced by hyperbaric oxygen. J Neurochem. 1969; 16(3):281–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Wylie DC, Das J, Chakraborty AK. Sensitivity of T cells to antigen and antagonism emerges from differential regulation of the same molecular signaling module. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007; 104(13): 5533–5538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Xiao X, Wang ZZ, Xu WG, Xiao K, Cai ZY, et al. Cerebral blood flow increase during prolonged hyperbaric oxygen exposure may not be necessary for subsequent convulsion. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2012; 18(11):947–949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Yildiz S, Aktas S, Cimsit M, Ay H, Toğrol E. Seizure incidence in 80,000 patient treatments with hyperbaric oxygen. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2004; 75:992–994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Yoles E, Zurovsky Y, Zarchin N, Mayevsky A. The effect of hyperbaric hyperoxia on brain function in the newborn dog in vivo. Neurol Res. 2000; 22(4):404–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Zhang C, Bélanger S, Pouliot P, Lesage F. Measurement of local partial pressure of oxygen in the brain tissue under normoxia and epilepsy with phosphorescence lifetime microscopy. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(8): e0135536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]