Abstract

The amnion is remodeled during pregnancy to protect the growing fetus it contains, and it is particularly dynamic just before and during labor. By combining ultrastructural, immunohistochemical, and Western blotting analyses, we found that human and mouse amnion membranes during labor were subject to epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT), mediated in part by the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway responding to oxidative stress. Primary human amnion epithelial cell (AEC) cultures established from amnion membranes from non-laboring, cesarean section deliveries exhibited EMT after exposure to oxidative stress, and the pregnancy maintenance hormone progesterone (P4) reversed this process. Oxidative stress or transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) stimulated EMT in a manner that depended on TGF-β–activated kinase 1 binding protein 1 (TAB1) and p38 MAPK. P4 stimulated the reverse transition, MET, in primary human amnion mesenchymal cells (AMCs) through the progesterone receptor membrane component 2 (PGRMC2) and c-MYC. Our results indicated that amnion membrane cells dynamically transition between epithelial and mesenchymal states to maintain amnion integrity, repair membrane damage, and in response to inflammation and mechanical damage and protect the fetus until parturition. An irreversible EMT and accumulation of AMCs characterize the amnion membranes at parturition.

One Sentence Summary

Balanced EMT and MET maintain amnion integrity during pregnancy, and increased EMT is associated with labor.

Remodeling the amnion

During pregnancy, the amniotic membrane undergoes growth, repair, and remodeling processes that depend on epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and the reverse, MET. The membrane weakens near the end of pregnancy in preparation for parturition, and aberrant weakening can lead to premature rupture. Richardson et al. found that amnions from mice and human term births exhibited increased epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and that oxidative stress stimulated EMT in preterm amnions. Experiments using primary human amnion epithelial and mesenchymal cells indicated that oxidative stress and transforming growth factor β (TGF-β), both of which increase at the end of pregnancy, promoted EMT, whereas the pregnancy maintenance hormone progesterone promoted MET. The authors propose that balanced EMT and MET maintain amnion homeostasis until the accumulation of oxidative stress and inflammatory factors trigger an irreversible EMT that leads to amnion weakening and membrane rupture at parturition.

Introduction

Human fetal membranes (collectively referred to as the amniochorion) are composed of multiple layers of cells and extracellular matrix (ECM). The amnion consists of an epithelial sheet oriented with the apical surface facing the amniotic cavity, a basement membrane rich in type IV collagen, and an underlying layer of fibroblasts. The chorion consists of trophoblast cells that are attached to the uterus, a basement membrane, and a layer of reticular cells. The amnion fibroblasts and the reticular layer of the chorion are attached to a spongy layer of ECM that separates the two membranes (1, 2). These mesenchymal cells embedded in ECM provide the structural scaffold for the avascular fetal membranes (3, 4), which define the intrauterine cavity and protect the fetus during gestation. The highly elastic amnion grows with the fetus from the time of embryogenesis and provides both immune and mechanical protection as well as endocrine functions (5). The amnion and chorion layers expand throughout gestation to accommodate the increasing volume of the fetus and amniotic fluid and fuse by the late first or early second trimester (6). Expansion of the fetal membranes requires constant physiological remodeling that is accompanied by cellular shedding (exfoliation) and repair of accumulated membrane microfractures (3). Failure to seal these microfracture defects can lead to degradation and loss of structural integrity of the membranes and appears to be a cause of preterm birth (2, 7).

Although extracellular matrix remodeling is reported to be mediated by matrix metalloproteinases (1, 8), the regulation of fetal membrane cellular remodeling is not well understood. As the innermost lining of the uterine cavity and a structural barrier, fetal membrane homeostasis is critical for successful maintenance of pregnancy. Senescence of fetal membrane cells also occurs as a physiological process that peaks near parturition due to mounting oxidative stress and inflammation in the intrauterine cavity at term, which is mediated predominantly by the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) (9, 10). Aging of the fetal membranes can lead to parturition in both human and animal models (7, 11). Premature activation of fetal membrane senescence in response to various pregnancy-associated risk factors can predispose membranes to dysfunction and rupture. Preterm premature rupture of the membranes (pPROM) is a common complication of pregnancy and accounts for ~ 40% of spontaneous preterm births (12, 13). pPROM contributes to significant neonatal morbidity and mortality, yet no diagnostic or clinical indicators exist to predict high risk. Current diagnostic tests only detect pPROM after its occurrence, creating a clinical quandary as to how to intervene for preventing preterm birth.

To understand predisposing factors that contribute to membrane weakening—specifically amnion stress and stretching—we investigated the mechanisms by which epithelial and mesenchymal cells in the amnion layer undergo remodeling or seal the gaps created by cell shedding. Amnion cells are capable of proliferation, migration, and pluripotent transitions, such as epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and the reverse, mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET), during remodeling (14). Oxidative stress can prevent remodeling by increasing senescence and inflammation; by contrast, nutrient-rich amniotic fluid accelerates remodeling (14, 15). Two key factors that likely mediate cellular transitions during gestation are transforming growth factor–β (TGF-β) and progesterone (P4). TGF-β is an established promoter of EMT (16–18), and P4, the dominant pregnancy maintenance hormone, reduces EMT (19), in part by promoting MET. We found that normal term parturition was associated with amnion membrane EMT, which also coincided with increased cellular and amniotic fluid TGF-β levels, in both humans and mice. We further tested the mechanisms of cellular transitions and the roles played by TGF-β and P4 and found that TGF-β binding to TGF-β receptor 1 (TGFBR1) led to activation of the TGF-β–activated kinase 1 binding protein 1 (TAB1) complex, which promotes autophosphorylation of p38 MAPK (20), thus stimulating amnion epithelial cell EMT. We also identified a unique dual role for P4 in the membranes: P4 maintained the amnion epithelial phenotype by reducing the abundance of EMT-associated transcription factors in the mesenchymal cells, and by forming a complex with progesterone receptor membrane component 2 (PGRMC2), which induced MET in amnion mesenchymal cells through a mechanism that depended on the c-MYC proto-oncogene.

Results

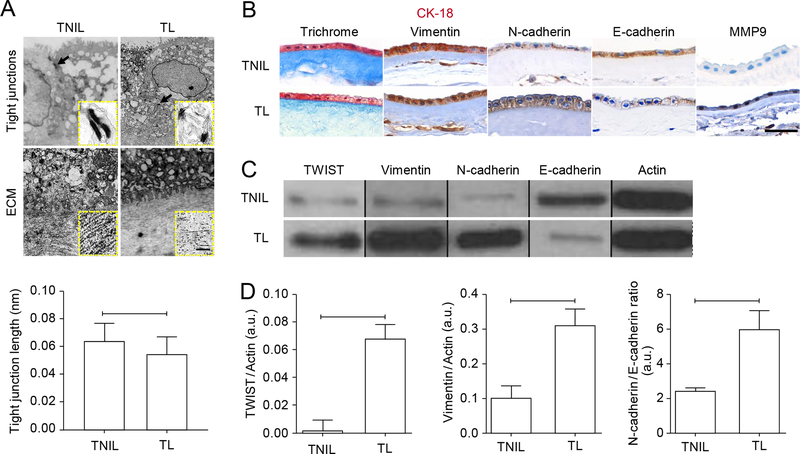

EMT is associated with human term labor

We compared morphological and molecular markers of EMT in amnion membranes from term vaginal deliveries (TL) to term not in labor (TNIL) membranes collected from scheduled cesarean deliveries. We first examined tight junctions in amnion membranes. Tight junctions are connections between epithelial cells, and EMT requires loosening of these junctions to enable epithelial cells to be shed and or migrate (21, 22). Migration also requires loosening of the collagen matrix (21). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) showed smaller desmosome plaques and a significant reduction in tight junction length, accompanied by ECM collagen degradation in TL compared to TNIL amnion membranes (Fig. 1A). Masson’s Trichrome staining also showed collagen degradation based on reduced intensity of blue staining marking the amnion membrane epithelium (Fig. 1B), thus supporting the TEM findings. Next, we examined the epithelium-specific marker cytokeratin 18 (CK-18), a component of type I intermediate filaments, and the mesenchyme-specific marker vimentin (21, 23, 24). Consistent with our prior report that amnion cells normally exist in a metastate producing both intermediate filament types (7), dual immunohistochemical staining co-localized CK-18 and vimentin (Fig. 1B); however, CK-18 was higher in TNIL membranes, whereas vimentin was higher in TL membranes, suggesting an increase in EMT with labor.

Fig. 1. Human amnion membranes from normal term labor show evidence of EMT.

(A) Transmission electron microscopy of amnion membranes from TL (term labor) compared to TNIL (term not in labor) fetal membranes showing tight junctions (arrows/arrowheads). Insets show electron-dense desmosomes. Images are representative of 3 independent biological replicates. Scale bars, XX (main image) and 0.05 nm (inset). (B) Histological analyses of TL and TNIL membranes: Masson’s Trichrome stain to show collagen, dual immunohistochemical (IHC) staining for CK-18 (pink) and vimentin (brown), and single IHC for N-cadherin, E-cadherin, and MMP9. Images are representative of 3 biological replicates. Scale bars, 50 μm. (C–D) Western blot analysis (C) and quantification (D) of TWIST, vimentin, N-cadherin, and E-cadherin in TL and TNIL membranes. Actin is a loading control. Cropped Western blots are shown; full blots are provided in the Supplementary Materials (fig. S5A). n = 5 biological replicates. Error bars represent Mean±SEM. P=0.004 (TWIST); P=0.009 (vimentin); P=0.031 (N-cadherin/E-cadherin). Linear adjustment of contrast and brightness has been applied to the brightfield images throughout figure sections.

We next examined the epithelium-specific adherens junction protein E-cadherin and its mesenchymal counterpart N-cadherin. Immunohistochemical analyses showed TL amnion membranes had higher N-cadherin and lower E-cadherin compared to TNIL (Fig. 1B), confirming an EMT shift by amnion epithelial cells in labor. We also examined matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9), one of the key type IV collagenases capable of degrading ECM (Fig. 1B). Recent studies by Kang Sun’s group have shown that MMP7 (Matrilysin) in amnion membrane cells can also degrade ECM, but this MMP was not tested in this report (25). MMP9, which is present in amniotic fluid during labor (1), was higher in TL compared to TNIL amnion membranes (Fig. 1B). To confirm histological data, Western blot analyses were performed and proteins quantified (Fig. 1, C and D). TL amnion membranes showed higher (3-fold) vimentin and a higher (2.4-fold) N-cadherin/E-cadherin ratio (Fig. 1, C and D; fig. S5A). Labor was associated with an increase in the N-cadherin/E-cadherin ratio in favor of N-cadherin, consistent with increased EMT (26). The presence of specific transcription factors associated with EMT, including TWIST, SNAIL, SLUG, ZEB1, and ZEB2, depend on the cell type, stimulus, and timing since stimulation TWIST was significantly more abundant (27-fold increase) in TL than TNIL membranes (Fig. 1,C and D). Although increasing trends were seen with SNAIL, SLUG, and ZEB in TL, those data did not reach statistical significance (Fig. S1A).

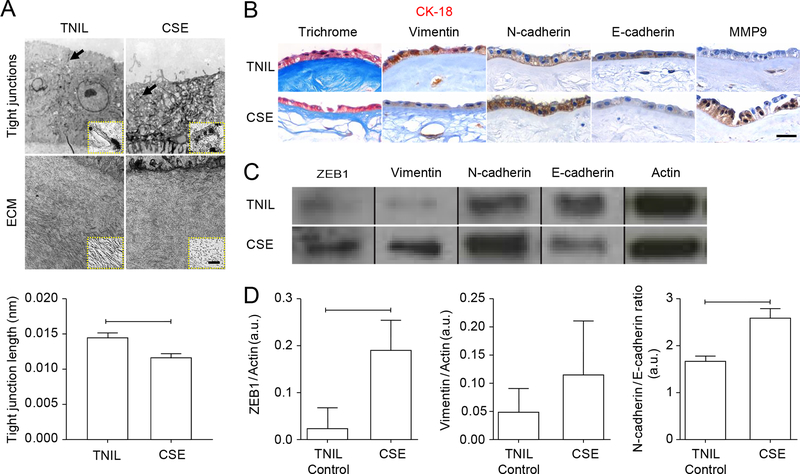

Oxidative stress induces EMT in human amnion membranes

We used a highly validated in vitro organ explant system (27) to test whether the above findings were recapitulated in TNIL fetal membrane clinical specimens treated with cigarette smoke extract (CSE) to induce oxidative stress (17, 28, 29). Our prior work has shown that CSE treatment of explanted TNIL fetal membrane explants produces oxidative damage to proteins, lipids, and DNA that is identical to changes seen in TL membranes (30) and causes activation of the cellular stress mediator p38 MAPK (30, 31). CSE-treated fetal membranes in culture had significant reduction in tight junction length as determined by TEM (Fig. 2A) and confirmed by Masson’s Trichrome staining (Fig. 2B). As seen in TL fetal membranes, CSE treatment of TNIL membranes also induced higher levels of vimentin, N- cadherin, and MMP9 and lower levels of CK-18 and E-cadherin (Fig. 2, B to D). CSE also reduced the N-cadherin/E-cadherin ratio 1.5-fold (Fig. 2D, fig. S5B). ZEB1 was significantly higher (8.3-fold) after CSE treatment compared to controls (Fig. 2, C and D), whereas SLUG and SNAIL were higher in response to CSE, but did not reach statistical significance (Fig. S1B).

Fig. 2. Term not in labor human amnion membranes exposed to oxidative stress show evidence of EMT.

(A) Transmission electron microscopy of cultured TNIL amnion membranes either untreated or exposed to cigarette smoke extract (CSE). Tight junctions are noted with arrows/arrowheads. Insets show a close up of one tight junction Images are representative of 3 biological replicates. Scale bars, 50μm (main image) and 0.05 nm (inset). (B) Histological analyses of untreated TNIL and CSE-treated TNIL membranes: Masson’s Trichrome stain to show collagen, dual IHC for CK-18 (pink) and vimentin (brown), and single IHC for N-cadherin, E-cadherin expression, and MMP9. Images are representative of 3 biological replicates. Scale bar, 50 μm. (C-D) Western blot analysis (C) and quantification (D) of ZEB1, vimentin, N-cadherin, and E-cadherin in untreated and CSE-treated TNIL membranes. Actin is a loading control. Cropped Western blots are shown; full blots are provided in the Supplementary Materials (fig. S5B). n = 3 biological replicates. Error bars represent Mean ± SEM. P=0.036 (ZEB1); P=0.664 (vimentin); P=0.0005 (N-cadherin/E-cadherin). Linear adjustment of contrast and brightness has been applied to all brightfield images throughout figure sections.

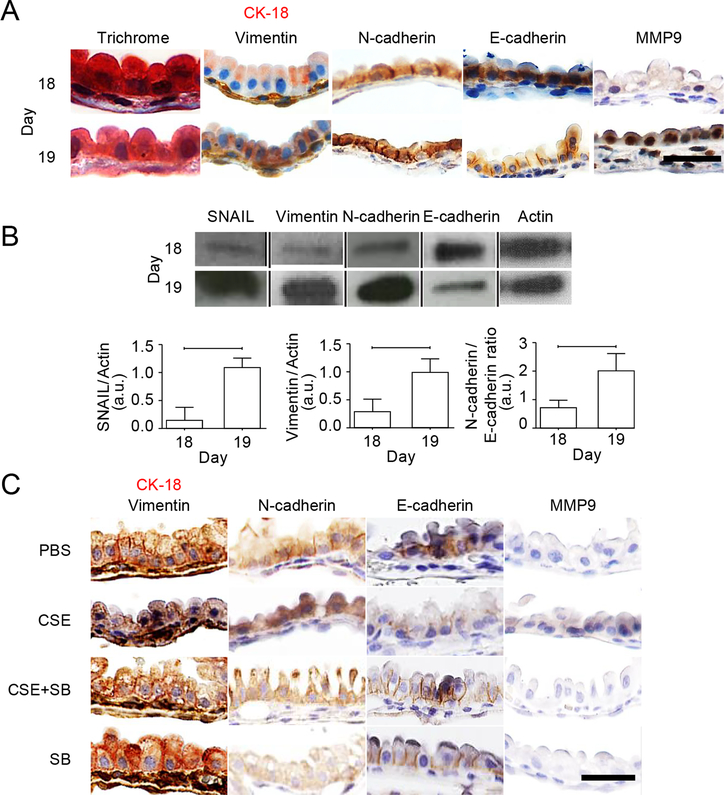

Oxidative stress induces p38-mediated EMT in a murine model

After observing EMT changes in human samples in vivo and in the organ culture in vitro model of oxidative stress, we proceeded to test whether similar changes could be identified in an animal model of labor. CD1 mice were selected for examining EMT phenotypic changes in amniotic sacs on D18, the penultimate day of pregnancy, versus D19, the morning of delivery in our colony. Masson’s Trichrome staining showed that collagen was more degraded on D19 than on D18, and this was accompanied by higher levels of vimentin, N-cadherin, and MMP9 and lower levels of CK-18 and E-cadherin (Fig. 3A, fig. S6). Western blot analyses confirmed the histology data, with D19 showing significantly increased vimentin (3.3-fold change) and an increased N-cadherin/E-cadherin ratio (2.8-fold change) (Fig. 3B and fig. S6, A to C). SNAIL was significantly increased on D19 compared to D18 (6.9-fold change) (Fig. 3B), but changes in SLUG abundance did not reach statistical significance (Fig. S1C). To test if oxidative stress induced changes similar to those seen on D19, we injected CD1 mice with CSE on D14 (29). Vimentin, N-cadherin, and MMP9 were higher, whereas CK-18 and E-cadherin were reduced (Fig. 3C). We previously reported that oxidative stress causes protein peroxidation and p38 MAPK–mediated senescence in this model (29). To confirm that EMT induction in this model is associated with p38 MAPK activation, animals were co-injected with CSE plus the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 on Day 14, and tissues were collected on Day 18 for analysis. SB203580 reduced EMT, as measured by the epithelial and mesenchymal markers, whether delivered alone or in combination with CSE (Fig. 3C). SB203580 treatment also reduced pup loss and preserved placental weight (table S1).

Fig. 3. Term labor and oxidative stress induce p38 MAPK–dependent EMT in mouse amnion membranes.

(A) Masson’s Trichrome staining, dual IHC staining for CK-18 (pink) and vimentin (brown), and single IHC staining for N-cadherin, E-cadherin, and MMP9 in D18 (pregnancy) and D19 (parturition) mouse amniotic sacs. Images are representative of 3 biological replicates. Scale bars, 50 μm. (B) Western blot analysis and quantification of SNAIL, vimentin, N-cadherin, and E-cadherin in D18 and D19 amniotic sacs. Actin is a loading control. Cropped Western blots are shown; full blots are provided in the Supplementary Materials (fig. S6, A to C). n = 5 biological replicates. Error bars represent Mean ± SEM. P= 0.001 (SNAIL), P=0.005 (vimentin), P=0.009 (N-cadherin/E-cadherin). (C) Dual IHC staining for CK-18 (pink) and vimentin (brown) and single IHC staining for N-cadherin, E-cadherin, and MMP9 in amniotic sacs from pregnant mice injected with PBS (control), CSE, CSE plus the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 (SB), or SB alone. Images are representative of 3 biological replicates. Scale bars, 50 μm. Linear adjustment of contrast and brightness has been applied to all brightfield images throughout figure sections.

Collectively, these data are supportive of an association among oxidative stress–induced p38 MAPK activation, EMT, and senescence to promote labor-associated changes in both humans and mouse. We cannot rule out that additive, indirect effects of gestational age may also contribute to these observations. The descriptive data detailed above used human TL and TNIL amnion membranes, mouse TL and TNIL amniotic sacs, and both in vitro (human) and in vivo (mouse) models of oxidative stress. We hypothesize that oxidative stress experienced at term prior to labor promotes p38 MAPK–mediated senescence and EMT in vivo. Further, these studies suggest that senescence may be a key feature of EMT in fetal membranes, likely aided by oxidative stress–associated p38 MAPK activators.

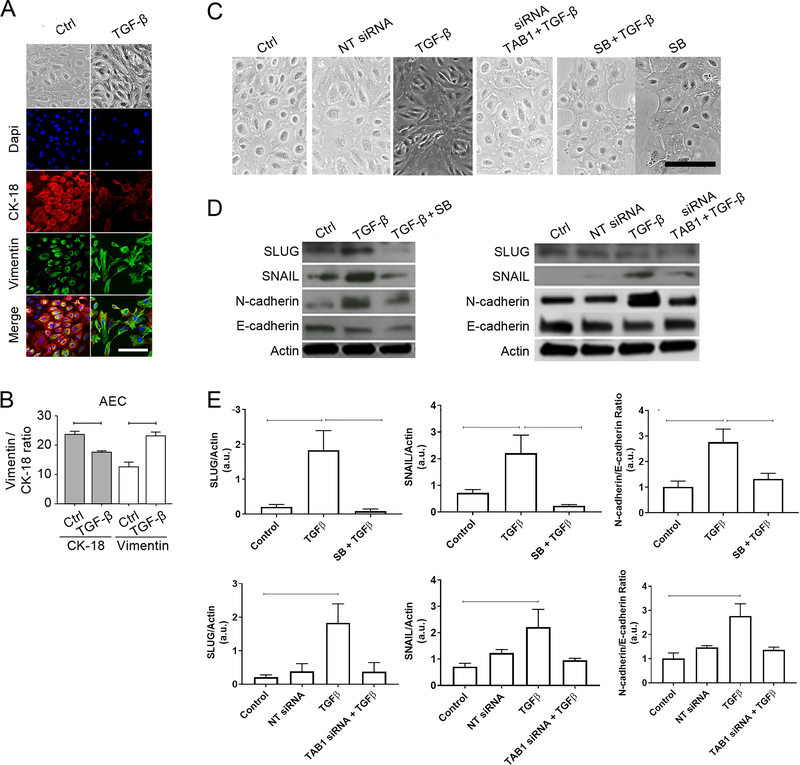

TGF-β induces TAB1- and p38-dependent EMT in AECs

We next addressed the possible endocrine, paracrine, or autocrine regulation of EMT using human primary amnion epithelial cells (AECs) derived from normal TNIL amnion membranes. Other investigators have established that TGF-β induces AECs to undergo EMT (13, 32, 33), and we have shown that TGF-β, in response to oxidative stress, stimulates autophosphorylation of p38 through TAB1, which can bypass the apoptotic signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1) and MAP3Ks (17). Therefore, we tested if TGF-β–TAB1–p38 MAPK signaling might induce EMT in AECs. As a first step to determine whether this process could occur in vivo, we determined the amounts of TGF-β in human amniotic fluid samples from various pregnancy conditions. TGF-β was significantly increased in amniotic fluid from TL compared to TNIL (8.2-fold increase) and in the amniotic fluid of women with preterm birth with premature membrane rupture (pPROM) compared to women who had preterm birth with intact fetal membranes (20.8-fold change) (fig. S2A). Both TNIL and pPROM are associated with increased oxidative stress (23, 28, 29, 34–36) and p38 MAPK activation (17, 27–29, 37). These findings demonstrate that TGF-β was increased in conditions associated with oxidative stress and fetal membrane rupture.

We then treated primary AECs with TGF-β for 6 days. TGF-β treatment promoted EMT changes in AECs, stimulating a change from the typical cuboidal shape to a fibroblastoid shape, increasing the abundance of vimentin (1.3-fold change), and reducing the abundance of CK-18 (2.3-fold change) (Fig. 4, A and B). Crystal violet dye exclusion testing showed that the morphological changes induced by TGF-β were not an artifact of changes in cell viability (fig. S2B) (38). Next, we verified the functional role of p38 MAPK in TGF-β–mediated EMT in AECs using siRNA-mediated TAB1 knockdown and the pharmacological inhibitor of p38 MAPK, SB20358. Treatment with TAB1 siRNA reduced the abundance of TAB1 mRNA and protein (fig. S2C). TAB1 siRNA or SB203580 blocked the TGF-β–induced change from cuboidal to fibroblastoid cell morphology, which were quantified as cell shape indices (Fig. 4C, fig. S2D), supporting the hypothesis that TGF-β can trigger EMT in AECs in a manner that depends on TAB1 and p38. TGF-β treatment also increased SLUG and SNAIL abundance compared to controls (8.8-fold change and 3.1-fold change, respectively) (Fig. 4, D and E; fig. S7, A and B). Co-treatment of AECs with TGF-β plus either TAB1 siRNA or SB203580 reduced SLUG (5-fold and 21.2-fold, respectively) and SNAIL (2.3-fold and 9.5-fold, respectively) abundance compared to TGF-β treatment alone. In accordance with this finding, we noted a higher (2.7-fold) N-cadherin/E-cadherin ratio (Fig. 4E) in AECs treated with TGF-β alone, but this was reversed by TAB1 siRNA or SB203580 co-treatment (Fig. 4E). SB203580 treatment alone did not induce changes in morphology, N-cadherin/E-cadherin ratios, or SNAIL and SLUG abundance (Fig. S2E). In summary, these experiments are consistent with TGF-β -induced, TAB1-mediated activation of p38 MAPK (17) leading to increases in EMT-associated transcription factors and N-cadherin and the adoption of a fibroblastoid cell shape (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. TGF-β induces EMT in a TAB1- and p38 MAPK–dependent manner in human AECs.

(A) Bright field microscopy and confocal fluorescence imaging showing cell morphology, CK-18, and vimentin in untreated (Ctrl) and TGF-β–treated human AECs. Nuclei are labelled with DAPI. Imagen=3). (B) Quantification of CK-18 and vimentin in (A). For CK-18, 23.81 ± 7.124 (control) and 17.73 ± 1.416 (TGF-β–treated); P=0.0002. For vimentin, 12.66 ± 10.63 (control) and 23.33 ± 4.751 (TGF-β–treated); P<0.0001. Values are expressed as mean intensity ± SD. Error bars represent Mean ± SEM. n = 3 biological replicates. Scale bars, 50 μm. (C) Bright field microscopy showing morphology of human AECs that were untreated (Ctrl) or treated with the indicated combinations of non-targeting (NT) siRNA, TAB1 siRNA, TGF-β, and the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580. Images are representative of 5 biological replicates. Scale bars, 50 μm. (D–E) Western blots (D) and quantification (E) of SLUG, SNAIL, N-cadherin, and E-cadherin in AECs treated as indicated. Actin is a loading control). n = 3 biological replicates. Error bars represent Mean ± SEM. Top graphs, TGF-β only compared to control: P = 0.027 (SNAIL), P = 0.013 (SLUG), and P = 0.008 (N-cadherin/E-cadherin); TGF-β only compared to TGF-β + SB: P = 0.022 (SNAIL), P = 0.025 (SLUG), and P = 0.046 (N-cadherin/E-cadherin). Bottom graphs, TGF-β only compared to control: P = 0.023 (SNAIL), P = 0.015 (SLUG), and P = 0.015 (N-cadherin/E-cadherin); TGF-β only compared to TGF-β + TAB1 siRNA: P = 0.184 (SNAIL), P = 0.080 (SLUG), and P = 0.159 (N-cadherin/E-cadherin). Linear adjustment of contrast and brightness has been applied to all brightfield or florescent images throughout figure sections.

Progesterone induces PGRMC2- and c-MYC–mediated MET in AMCs

EMT is a transitional state rather than a stable state, and a homeostatic return of mesenchymal to epithelial phenotype is necessary for the maintenance of fetal membrane integrity. A recent report from our laboratory using scratch assays has shown that wounded primary AECs resemble healing microfractures observed in intact fetal membranes (7). This healing is associated with proliferation, migration (EMT), and wound closure (EMT to MET) within 38 hrs (7). Cells at proliferative and migrating edges display predominantly fibroblastoid shapes with superficial vimentin localization, whereas cells at healed edges were cuboidal with perinuclear vimentin staining (7). AEC wound healing was accelerated by amniotic fluid and restrained by inducers of oxidative stress (7). Based on these lines of evidence, we postulate that MET facilitates the reversal of fibroblastoid cells to an epithelial state, because this transition is essential for filling gaps created by epithelial cell exfoliation and migration during gestation. EMT is associated with inflammation, and sustained inflammation may damage or weaken fetal membranes. The anti-inflammatory properties of P4 have been postulated to minimize EMT’s inflammatory effects by transitioning cells back to their epithelial state through MET (16). Prior to testing the role of P4 in our in vitro system, we confirmed that AECs did not produce the classical nuclear progesterone receptors PRB and PRA, confirming the previous findings of Murtha et al. (9), and indicting that the actions of P4 in AECs are likely mediated through the membrane progesterone receptors PGRMC1 and/or PGRMC2. PGRMC1 abundance did not differ between human TNIL and TL fetal membranes; however, we noticed a significant labor-induced 3.2-fold decrease in PGRMC2 (fig. S3A; fig. S7B). This was recapitulated in vitro with amnion mesenchymal cells (AMCs) subjected to CSE-induced oxidative stress, showing no change in PGRMC1 but a threefold reduction in PGRMC2 (fig. S3B and C; fig. S7B). Additionally, overexpression of PGRMC2 in AMCs increased P4-induced MET, and MET was evident even under oxidative stress conditions in cells that overexpressed PGRMC2 (Fig. S4).

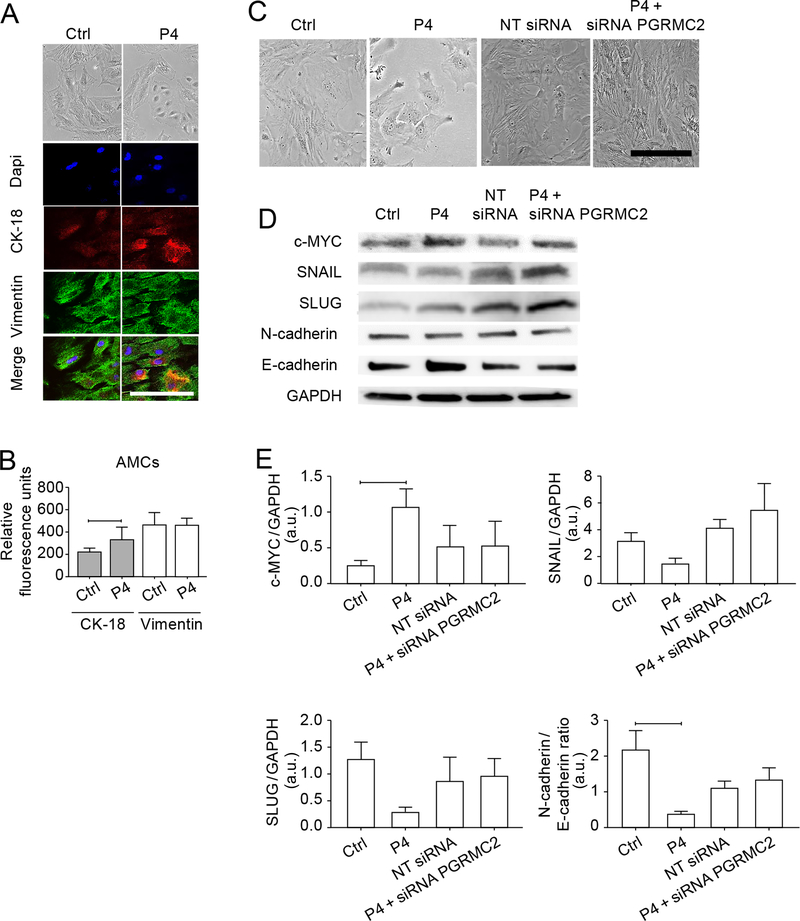

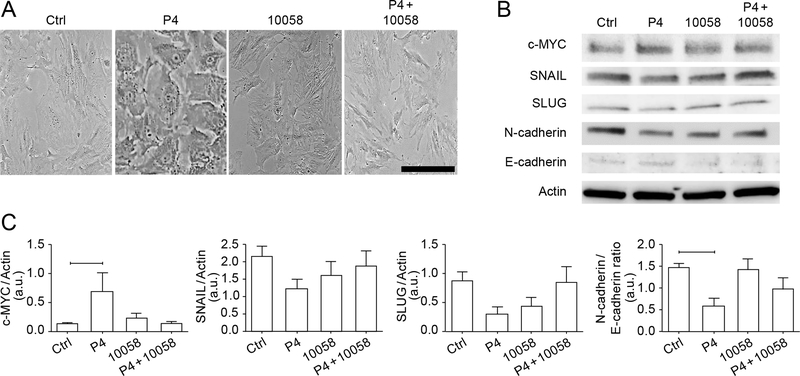

Based on these data, we hypothesized that P4 induces MET in AMCs through PGRMC2. We treated primary AMCs with 200 ng/mL P4, which approximates the concentration of P4 at term, for 6 days. P4 treatment was associated with a shift from fibroblastoid to cuboidal shape with increased abundance of CK-18 (1.5-fold change) (Fig. 5, A and B). We did not observe changes in vimentin staining. Crystal dye exclusion test showed that morphological changes induced by P4 were not an artifact of changes in cell viability (Fig. S3D–E). To test the role of PGRMC2 in this transition, we compared EMT markers and cell morphology in P4-treated AMCs that were either untreated or treated with a PGRMC2-specific siRNA that reduced the abundance of both transcripts and protein (Fig. 5C; Fig. S3F). P4 treatment of AMCs led to a shift in epithelial morphology that was blocked by knocking down PGRMC2 (Fig. 5C) (Fig. 5C). Western blot analysis showed a P4-induced increase (4.2-fold) in c-MYC (Fig. 5D–E), which has been reported to mediate the effects of P4 signaling through PGRMC2 (39). P4 suppressed the accumulation of EMT-associated transcription factors SNAIL (2.1-fold change) and SLUG (4.5-fold change), and this was restored by co-treatment with PGRMC2 siRNA (Fig. 5E). Further, P4 treatment decreased N-cadherin while increasing E-cadherin, contributing to an overall decrease in the N-cadherin/E-cadherin ratio (5.7-fold change) (Fig. 5E). PGRMC2 siRNA reversed this change, supporting a role for P4-PGRMC2 signaling in promoting MET. We then tested if P4-induced morphologic changes were mediated by increased c-MYC. P4 treatment of AMCs led to a shift in epithelial morphology that was blocked by the selective c-MYC inhibitor 10058 (Fig. 6A), consistent with a role for c-MYC in P4-induced MET. In support of this finding, co-treatment of P4 with 10058 showed trends, though not statistically significant changes, of slightly higher SNAIL, SLUG, and N-cadherin/E-cadherin ratio (Fig. 6B–C). In summary, these experiments show that P4-PGRMC2 elicited changes in cell morphology and decreases in EMT-associated transcription factors and N-cadherin in a manner that likely depended on c-MYC.

Fig. 5. P4 induces MET in human AMCs in a PGRMC2-dependent manner.

(A) Bright field microscopy and confocal imaging showing cell morphology, CK-18, and vimentin in untreated (Ctrl) and progesterone (P4)-treated primary human AMCs. Nuclei are labelled with DAPI. Scale bars, 50 μm. (B) Quantification of CK-18 and vimentin in (A). Error bars represent Mean±SEM. n = 3 biological replicates. For CK-18, 226.7 ± 29.01 (control) and 348.4 ± 111 (P4); P=0.002. For vimentin, 467.6 ± 106.6 (control) and 448.5 ± 82.1 (P4); P=0.995. (C) Bright field microscopy showing morphology of untreated AMCs (Ctrl) and AMCs treated with the indicated combinations of P4, non-targeting (NT) siRNA, and PGRMC2 siRNA, Images are representative of 3 independent experiments. Scale bars, 50 μm. (D–E) Western blot analysis (D) and quantification (E) of c-MYC, SNAIL, SLUG, N-cadherin, and E-cadherin in AMCs treated as indicated. Error bars represent means ± SEM. P4 only compared to control: P = 0.010 (c-MYC), P = 0.490 (SNAIL), P = 0.130 (SLUG), and P = 0.030 (N-cadherin/E-cadherin); P4 only compared to P4 + siRNA PGRMC2: P = 0.398 (c-MYC), P = 0.084 (SNAIL), P = 0.381 (SLUG), and P = 0.490 (N-cadherin/E-cadherin). n = 3 biological replicates. Linear adjustment of contrast and brightness has been applied to all brightfield images throughout figure sections.

Fig. 6. P4 induces MET in human AMCs in a c-MYC–dependent manner.

(A) Bright field microscopy showing morphology of primary human AMCs that were untreated or treated with P4, the c-MYC inhibitor 10058, or both P4 and 10058. Image is representative image of 3 independent experiments. Scale bar, 25 μm. (B–C) Western blot analysis (B) and quantification (C) of c-MYC, SNAIL, SLUG, N-cadherin, and E-cadherin in AMCs treated with P4, 10058, or both. Actin is a loading control. n = 3 biological replicates. Error bars represent Mean± SEM. P4 only compared to control: P = 0.049 (c-MYC), P = 0.0.326 (SNAIL), P = 0.176 (SLUG), and P = 0.047 (N-cadherin/E-cadherin); P4 only compared to P4 + 10058: P = 0.050 (c-MYC), P = 0.609 (SNAIL), P = 0.201 (SLUG), and P = 0.512 (N-cadherin/E-cadherin). Linear adjustment of contrast and brightness has been applied to all brightfield images throughout figure sections.

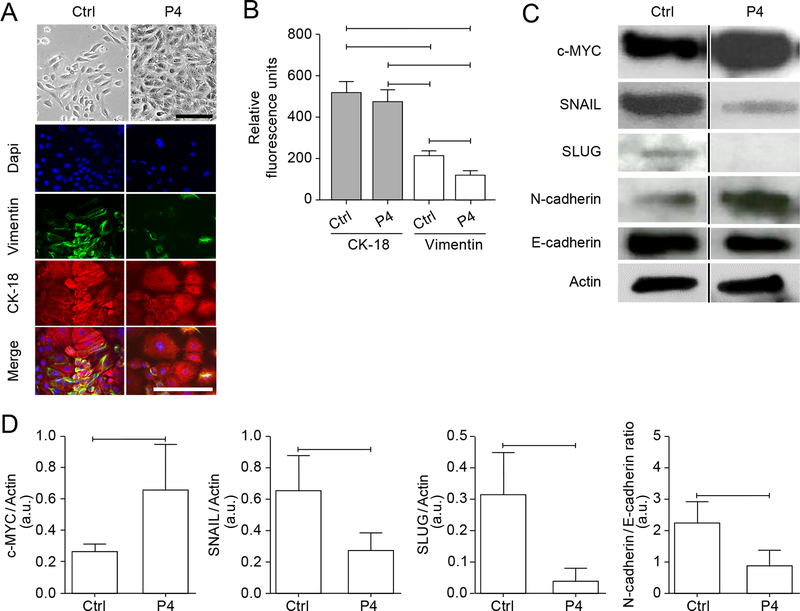

Treating AECs with P4 for 6 days had no effect on cell viability (fig. S3G), maintained epithelial morphology (Fig. 7A, fig. S3H) and CK-18 abundance, and significantly reduced vimentin compared to untreated cells (1.7-fold change) (Fig. 7, A and B). In addition, P4 significantly increased c-MYC (2.4-fold change), decreased SNAIL and SLUG abundance (2.3-fold and 7.7-fold change, respectively), and reduced the N-cadherin/E-cadherin ratio (2.5-fold change) (Fig. 7C–D, fig. S7A). These data support the theory that the high concentrations of circulating P4 in late pregnancy maintain epithelial characteristics in AECs.

Fig. 7. P4 maintains the epithelial state of human AECs.

(A) Bright field microscopy showing morphology of primary human AECs treated with P4 for 6 days and confocal immunofluorescence showing vimentin and CK-18. Nuclei are labelled with DAPI. Image is representative of 3 biological replicates. Scale bars, 50 μm. (B) Quantification of CK-18 and vimentin in (A). Error bars represent Mean± SEM. For vimentin, 223 ± 15.47 (control), 130.1 ± 15.68 (P4), P<0.0001. For CK-18, 523 ± 57.5 (control), 480.3 ± 52.01 (P4), P=0.166. n = 3 independent experiments. (C–D) Western blot analysis (C) and quantification (D) the indicated proteins in untreated and P4-treated AECs. Cropped Western blots are shown; full blots can be found in the Supplementary Materials (fig. S7A). n = 5 biological replicates. Error bars represent Mean± SEM. c-MYC (P=0.0211); SNAIL (P=0.023); SLUG (P=0.007); N-cadherin/E-cadherin ratio (P=0.005). Linear adjustment of contrast and brightness has been applied to all brightfield images throughout figure sections.

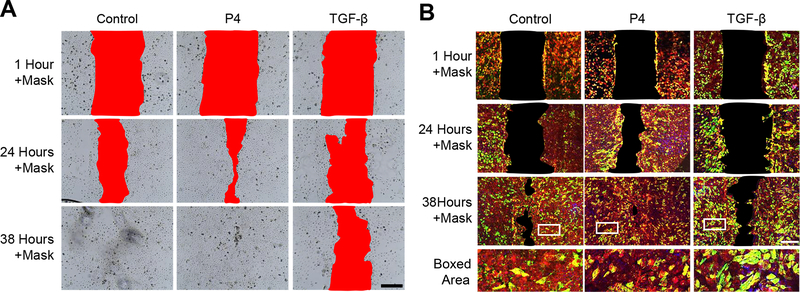

Reversible EMT and MET mediate amnion healing

To further confirm that TGF-β and P4 conferred opposing effects on AECs, we performed in vitro scratch assays. A scratch in an AEC monolayer normally heals within 38 hrs (Fig. 8, A and B). TGF-β substantially inhibited the healing of AEC scratches, with full persistence of the wound after 38 hrs, whereas P4 accelerated healing (Fig. 8A). Immunostaining for CK-18 and vimentin showed that fibroblastoid-shaped cells with high amounts of vimentin dominated the leading edges of wounds that failsed to heal after 38 hrs (Fig. 8B). In contrast, healed areas after P4 treatment and in untreated cultures were dominated by CK-18–positive cells with epithelial morphology (Fig. 8B). These data further support that P4-mediated remodeling of the amnion membrane is likely to promote membrane repair and homeostasis during pregnancy, whereas oxidative stress–induced TGF-β may induce a non-reversible state of EMT.

Fig. 8. P4 expedites wound healing of human AECs in vitro.

(A) Healing of scratch wounds in primary human AECs normal cell culture conditions (control) or treated with P4 or TGF-β. A red mask was applied to aid visualization of the wound field. Images are representative of 3 biological replicates. Scale bar, 100 μm. (B) Immunofluorescence showing vimentin (green) and CK-18 (red) in scratch-wounded primary AECs treated as indicated. A black mask was applied to aid visualization of the wound field. Images are representative of 3 biological replicates. Scale bars, 100 μm. Linear adjustment of contrast and brightness has been applied to all florescent images throughout figure sections.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the mechanisms and mediators through which epithelial and mesenchymal cells of the amnion membrane undergo cyclic remodeling to maintain membrane integrity during pregnancy. We showed that human and murine amnion epithelial cells exist in a “metastate” at term, co-expressing both epithelial and mesenchymal markers (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, and Fig. 3); however, mesenchymal features dominated in term laboring (TL) compared to term non-laboring (TNIL) fetal membranes. These findings were recapitulated in vitro with organ explants of TNIL fetal membranes that were exposed to oxidative stress (Fig. 2). These finding support previous reports by Janzen et al. (40) and Mogami et al. (10) that reported descriptive evidence of EMT in term laboring fetal membranes. The transition from not-in-labor to labor at term is associated with increased oxidative stress, peroxidation of various cellular elements, and activation of p38 MAPK. Senescence and senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP, a form of sterile inflammation) have been observed in fetal membranes during labor (30). Fetal membranes at TL have more microfractures, degraded basement membranes, and augmented cell migration compared to not-in-labor fetal membranes (2). Based on our findings (Fig. 1 and 2), we speculate that molecular and cellular senescence is associated with a terminal (irreversible or static) state of EMT. EMT and associated inflammation and ECM matrix weakening are predisposing factors for mechanical disruption of amnion membranes prompting and facilitating labor and delivery.

We investigated the role of TGF-β as a facilitator of amnion EMT because TGF-β is increased in TL amniotic fluid compared to TNIL (fig. S2A), immunoreactivity for TGF-β is higher in fetal membranes from TL vs. TNIL (17), in vitro evidence shows that oxidative stress can increase the release TGF-β from fetal membranes (17), and TGF-β is one of the classical SASP markers (41). In addition, extracellular vesicles released from AECs under oxidative stress are enriched in TGF-β peptides (42), suggesting a paracrine pathway to promote EMT. Amnion cells exposed to oxidative stress also undergo TGF-β–mediated autophosphorylation of p38 MAPK (17), a key signal that enforces fetal membrane senescence. In summary, intrauterine oxidative stress at term can initiate a cascade of events mediated by TGF-β–p38 MAPK–senescence–EMT that will weaken the amnion. After EMT, the resultant mesenchymal cells are more susceptible to oxidative stress (43–45) than are their epithelial predecessors, and they produce inflammatory cytokines and MMPs and stimulate collagen degradation that can compromise fetal membrane integrity (40). Loss of tight junctions also promotes disassembly of ECM scaffold structures (46). The accumulation of mesenchymal cells in TL vs. TNIL membranes (fig. 5A) supports this concept that the increased mesenchymal character of the constituent cells weakens the amnion, thus hastening membrane rupture and labor.

TGF-β–mediated EMT is a well-reported phenomenon across development, and our data indicate that the amnion epithelium is no exception. Blocking TGF-β–mediated signaling by silencing TAB1 reduced EMT-associated transcription factors and mesenchymal markers, thus maintaining epithelial characteristics. Silencing of TGF-β signaling also reduces p38 MAPK activation (17). Inhibition of EMT in AECs by treatment with a p38 MAPK inhibitor (SB203580) further implicates this pathway (Fig. 4). In both human fetal membranes and mouse amniotic sacs, the p38 MAPK inhibitor reduced mesenchymal intermediate filaments, junction markers, and transcription factors (Fig. 3 and Fig. 4). Although differential increases in ZEB (47), SNAIL (48), SLUG (49), and TWIST (50) were seen between species and distinct stimulants, all of these transcription factors can be activated by p38 MAPK to induce EMT. The potential redundancy may ensure the appropriate state of cellular transition. TGF-β–p38 MAPK signaling plays a major role in membrane homeostasis and cell remodeling throughout gestation (17), and is regulated by many factors including P4 (16, 40). Amnion epithelial cells that undergo EMT but are not permanently shed may move into the mesenchymal layer where they remain as a pool of cells capable of repairing microfractures and gaps in the amnion membrane or recycling to the epithelium by undergoing MET. The production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (27, 28) and p38 MAPK activation peak at term (23, 31, 34, 51, 52) to augment amnion cell senescence and SASP-induced inflammation to promote a terminal state of EMT (Fig. 9).

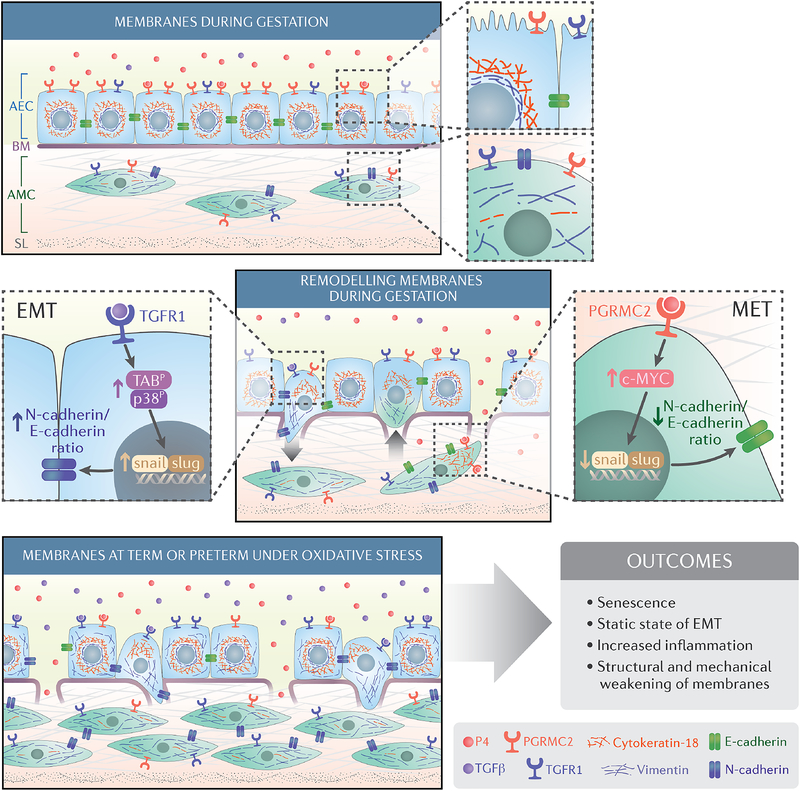

Fig. 9. Schematic of amnion membrane maintenance and disruption due to cellular transitions.

The amnion membrane is comprised of amnion epithelial cells (AECs) and amnion mesenchymal cells (AMCs) that are embedded in ECM and separated from the AECs by a basement membrane (BM) that is rich in Type 4 collagen. During gestation, progesterone (P4), helps to maintain the epithelial state of AECs, and AMCs have a fibroblastoid morphology. We hypothesize that the plasticity of amnion membrane cells allows remodeling of the membrane through cycles of MET and EMT. This maintains inflammatory homeostasis during gestation through a balance of P4-mediated MET and TGF-β–mediated EMT pathways to limit localized inflammation and repair microfractures. At term and preterm, increased oxidative stress and senescence cause an increase in TGF-β both in AMCs and in amniotic fluid and a functional withdrawal of progesterone signaling in AMCs due to a decrease in the P4 receptor PGRMC2. This induces a static state of EMT, increased numbers of AMCs, and inflammation, all of which contributing to labor-associated outcomes such as membrane rupture.

We also examined the mechanisms of recycling of mesenchymal cells back to an epithelial phenotype. Mesenchymal cells perform endocrine functions during gestation (53); however, these functions are tightly regulated and only require a limited number of cells (approximately 10% of amnion membrane cell are mesenchymal). Because mesenchymal cells are predisposed to generating inflammatory and ROS signals (43, 45), their numbers need to be tightly regulated, and this may be achieved by reprograming them back to an epithelial state through MET. MET reestablishes cell-to-cell contacts which is vital to maintain membrane integrity.. Because P4 is a known anti-inflammatory hormone that supports pregnancy maintenance, we tested its ability to reverse EMT to MET. We showed that P4, through PGRMC2, induces MET in a manner that depends on c-MYC (Fig. 5 and Fig. 6). Silencing PGRMC2 or inhbiting c-MYC increased mesenchymal transcription factors and promoted a fibroblastoid phenotype (Fig. 5 and Fig. 6). Based on these data, we postulated that P4 in the amniotic fluid or endogenously produced by amnion epithelial cells may play a functional role in maintaining membrane homeostasis. Because P4 increases PGRMC2 transcripts and protein in AMCs (Fig. S3F), this also provides a feedforward loop to promote MET. Overexpression of PGRMC2 in AMCs increased P4-induced MET, and MET was evident even under oxidative stress conditions in cells that overexpressed PGRMC2 (Fig. S4). However, PGRMC2 was reduced in TL fetal membranes, specifically in the mesenchymal cells (Fig. S3A), likely due to oxidative stress in the amniotic cavity. Exposing AMCs in culture to CSE, an inducer of oxidative stress, caused a reduction in PGRMC2 (Fig. S3B). No change in PGRMC2 was observed in AECs (Fig. S3C), but a decrease was observed in PGRMC1, supporting prior reports by Feng et al (9, 54). An overall reduction in PGRMC2 induced a localized ‘functional P4 withdrawal’ that disrupted MET. We propose this as one of the mechanisms leading to a terminal or static state of EMT at term, indicating a role for P4 in maintaining fetal membrane integrity (Fig. 9).

Maintenance of fetal membrane integrity during gestation and its mechanical and functional disruption at term involve changes in both cells and matrix. Although collagenolysis is well reported, this study emphasizes the role played by the amnion cells themselves. AECs and AMCs can undergo cyclic reprograming throughout gestation under the influence of changes in local tissue environment, such as localized inflammation promoting EMT and P4 supporting MET (Fig. 9). Increases in intrauterine oxidative stress, TGF-β– and p38 MAPK–mediated senescence, and EMT increase the number of AMCs in membranes. This can be detrimental to membrane homeostasis because AMCs are known inducers of prostaglandins, MMPs, and pro-inflammatory cytokines (55, 56), all which can induce membrane weakening, leading to premature membrane rupture. On the other hand, the accumulation of AMCs provides a mechanism to amplify fetal inflammatory responses that are required to promote parturition and therefore fulfill a natural and physiologic need at term. During gestation, P4, through its membrane receptor, controls the number of AMCs by converting them back to AECs (Fig. 9) to maintain membrane integrity. This study has some limitations because the amnion layer of the fetal membranes has dominated our focus. Microfractures also have been reported in the chorion layer (2), and chorion cells undergo a similar type of oxidative stress, p38 MAPK activation, and senescence (28). The chorion trophoblast cells and fibroblastoid cells of its reticular layer also can be susceptible to similar transitions. This region is vulnerable to signals from the maternal decidua and its resident immune cells (57). TGF-β and P4 were obvious choices for investigation in this study because the level of the former increases (17) and the activity of the latter is reduced (58) in TL. Furthermore, P4 is a known activator of c-MYC and an inducer off MET. Estrogens, IL-6, and other labor-associated growth factors known to increase in amniotic fluid at term, such as epidermal growth factor (EGF) and fibroblast growth factor (FGF), can also promote EMT (59–61). Although our model emphasizes the contribution of TGF-β, it is highly likely that EMT in TL is mediated by synergy and cooperation among multiple factors.

Materials and Methods

IRB approval

This study protocol is approved by the Institutional Review Board at The University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB) at Galveston, TX, as an exempt protocol to use discarded placenta after normal term cesarean deliveries (UTMB 11–251). No subject recruitment or consenting was required for this study.

Clinical samples

Fetal membranes (combined amniochorion and decidua) were collected from TNIL cesarean deliveries with no documented pregnancy complications and TL vaginal deliveries. Fetal membranes were dissected from the placenta, washed 3 times in normal saline, and cleansed of blood clots using cotton gauze. Six-millimeter biopsies (explants) were then cut from the midzone portion of the membranes, avoiding the regions overlying the cervix or placenta. The amnion was then separated from the chorion and explants were processed for a variety of assays.

Inclusion Criteria: Normal term birth were women with TL and delivery (> 390/7 weeks) and no pregnancy-related complications. Exclusion Criteria: Subjects with multiple gestations, placenta previa, fetal anomalies, and/or medical or surgeries (intervention for clinical conditions that are not linked to pregnancy) during pregnancy were excluded. Severe cases of preeclampsia or persistent symptoms (headache, vision changes, RUQ pain) or abnormal laboratory findings (thrombocytopenia, repeated abnormal liver function tests, creatinine doubling or > 1.2, or HELLP syndrome) or clinical findings (pulmonary edema or eclampsia) were excluded. Subjects who had any surgical procedures during pregnancy or who were treated for hypertension, preterm labor or for suspected clinical chorioamnionitis (reports on foul-smelling vaginal discharge, high levels of CRP, fetal tachycardia), positive GBS screening or diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis, behavioral issues (cigarette smoking, drug or alcohol abuse) and delivered at term were excluded from the control groups.

In vitro fetal membrane organ culture and stimulation with CSE

The in vitro organ explant culture system for human fetal membranes and stimulation of membranes with cigarette smoke extract was performed as previously reported (27, 42, 62). In this study, cigarette smoke extract was used to mimic the oxidative stress experienced by fetal membranes at term prior to labor that will transition the membrane into a labor phenotype (30). In short, 6mm biopsies of fetal membranes were collected from not laboring cesarean deliveries and placed in an organ explant system for 24 hours. Cigarette smoke extract (CSE) was prepared by bubbling smoke drawn from a single lit commercial cigarette (unfiltered Camel; R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co., Winston Salem, NC) through 50 mL of tissue culture medium (Ham’s F12/Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium mixture with antimicrobial agents) which was then filter sterilized through a 0.22-mm filter (Millipore, Bedford, MA) to remove contaminant microbes and insoluble particles. Fetal membranes were then stimulated with cigarette smoke extract (1:25 dilution) for 48 hours, while the cesarean explants were replaced with tissue culture medium. After a 48 hours treatment, the explants were removed the amnion was separated from the chorion and processed for a variety of assays.

Collection of CD-1 amniotic sacs

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston approved the study protocol. CD-1 pregnant mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). Animals were shipped on Day10 of gestation and acclimated in a temperature- and humidity-controlled facility with automatically controlled 12:12 hour light and dark cycles. Mice were allowed to consume regular chow and drinking solution ad libitum. Mice were allowed to consume regular chow and drinking solution ad libitum. At Day14 of pregnancy, the pregnant CD-1 mice were weighed and subjected to minilaparotomy and injection of 150uL of the treatment solution into uteri, physically between 2–3 gestational sacs, according to the following experimental groups: 1) cigarette smoke extract (CSE) diluted in saline; 2) CSE in combination with SB203580 (p38MAPK inhibitor) and 3) saline alone (control). After sacrificing the animals by using carbon dioxide inhalation according to the IACUC and American Veterinary Medical Association guidelines on Day18, maternal, fetal, and placental weight was documented and pup loss/reabsorption was counted. Amniotic sacs and placentae were collected in either 10% formalin or fresh frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until further analysis. Additionally, CD-1 mice at embryonic Day 18, and 19 of pregnancy were sacrificed using carbon dioxide inhalation according to the IACUC and American Veterinary Medical Association guidelines. Amniotic sacs were collected and collected in either 10% formalin or fresh frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until further analysis.

Amnion epithelial cell (AEC) in vitro culture

Primary AECs were isolated from TNIL amnion (about 10 g), peeled from the chorion layer and dispersed by successive treatments with 0.125% collagenase and 1.2% Trypsin (17, 42). The dispersed cells were plated in a 1:1 mixture of Ham’s F12/DMEM, supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 10 ng/ml EGF, 2 mM L-Glutamine, 100 U/ml Penicillin G and 100 mg/ml Streptomycin at a density of 3–5 million cells per T75 and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 until they were 80–90% confluent.

Amnion mesenchymal cell (AMC) in vitro culture

AMCs were isolated from amnion membranes as previously described by Kendal-Wright et al. (28, 55) with slight modifications. Primary AMCs were isolated from amnion membranes of women experiencing normal parturient at term (not in labor) and undergoing a repeat elective cesarean section. Reflected amnion (∼10 g) was peeled from the chorion layer and rinsed three or four times in sterile Hanks Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) (Cat# 21–021-CV, Corning) to remove blood debris. The sample was then incubated with 0.05% trypsin/EDTA (Cat# 25–053-CI, Corning) for 1 h at 37 °C (water bath) to disperse the cells and remove the epithelial cell layer. The amnion membrane pieces were then washed three to four times using cold HBSS to inactivate the enzyme. The washed amnion membrane was transferred into a second digestion buffer containing Minimum Essential Medium Eagle (Cat# 10–010-CV, Corning), 1 mg/mL collagenase type IV, and 25 μg/mL DNase I and incubated in a rotator at 37°C for 1 h. The digested amnion membrane solution was neutralized using Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM)/F12 media (Cat# 16–405-CV, Corning), filtered using a 70 μm cell strainer, and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min. The cell pellet was resuspended in complete DMEM/F12 media supplemented with 5% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Cat# 35–010-CV, Corning), 100 U/ml penicillin G, and 100 mg/mL streptomycin (Cat# 30–001- CI, Corning), plated at 3–5 million cells per T75, and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 until they were 80–90% confluent.

Quantitation of AEC and AMC from amnion membranes

Fetal membranes were collected from TNIL cesarean deliveries with no documented pregnancy complications and TL vaginal deliveries. Fetal membranes were dissected from the placenta, washed 3 times in normal saline, and cleansed of blood clots using cotton gauze. 0.0006m2 sections were then cut from three different regions of the midzone, avoiding the regions overlying the cervix or placenta. The amnion membrane was then separated from the chorion and the sections were processed using the AMC collection method. AECs were removed after the first digestion and AMCs were removed after the second digestion. Cells were counted manually as well as using an automatic cell counter (Countless 2 FL automated cell counter, ThermoFisher). These data were then used for analysis to determine the changes in AEC/AMC ratios at TNIL and TL.

Cell culture treatments

To induce cellular transitions in AECs, once cells reached 40–50% confluence, each flask was serum starved for 1 hour, rinsed with sterile 1x PBS followed by treatment with media (control), 15ng/ml TGF-β containing media, TGF-β+SB203580 (10μm) a p38MAPK functional inhibitor, SB203580 alone, TGF-β+siRNA to TAB1 (150nM), or progesterone (P4) (30ng/mL) and incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2, and 95% air humidity for 6 days. To induce MET in AMCs, once cells reached 40–50% confluence, each flask was serum starved for 1 hour, rinsed with sterile 1x PBS followed by treatment with media (control), 200ng/mL P4 containing media, P4+10058 (75μM) a pharmaceutical inhibitor of c-MYC, or P4+siRNA to PGRMC2 (150nM) and incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2, and 95% air humidity for 6 days. Cells were collected for PCR and western blots analysis. siRNA transfection: To determine the potential role of TAB1 regulation of TGF-β induced EMT in AEC, and PGRMC2 induced MET in AMCs, we downregulated TAB1 and PGRMC2 using siGENOME siRNA (GE Healthcare Dharmacon, Thermo Fisher Scientific) (table S2). Briefly, AECs and AMCs were cultured to nearly 50% confluence in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and antimicrobial agents (Penicillin/Streptomycin, Amphotericin). Prior to siRNA transfection, cells were incubated with antimicrobial-free medium overnight. Next, cells were incubated for 4 hours with siRNA complexes, which were freshly prepared using either 150 nM siRNA to specific genes or non-target (NT) siRNA as control and 0.3% Lipofectamine® RNAiMAX (Invitrogen) in Opti-MEM™ I Reduced Serum Medium. Cells were further incubated in growth media for 6 Days. Downregulation efficiency of the target genes was validated by qRT-PCR. Gene expression was normalized to non-transfected control.

Overexpression of PGRMC2 in AMCs

To determine if OS-induced functional P4 withdrawal in AMCs occurs through PGRMC2, overexpression studies were carried out. AMCs were cultured to nearly 50% confluence in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and antimicrobial agents (Penicillin/Streptomycin, Amphotericin) then transfected with 800ng of GFP-PGRMC2 expression plasmids (table S3) with FuGENE ® (1:3 plasmid weight) (Promega) in Opti-MEM™ I Reduced Serum Medium. After 24 hours, Opti-MEM was removed, and cells were treated with control, CSE (1:50), or CSE+P4 (200ng/mL) for 48 hours.

Scratch assay and cell culture treatments

Passage (P)1 AECs were seeded at approximately at 80% confluence in 4-well coverslips and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 24 hours. AECs were then serum-starved for 1 hour, rinsed with sterile 1 × PBS, and then scratched evenly down the middle of the well, in a straight line, with a 200μl pipet tip (7). Cells were washed with sterile 1 × PBS four times to remove any cell debris. Cell were then treated with 15ng/ml TGF-β or P4 (30ng/mL) for 1 hour, 24, and 38 hours. Bright field and confocal microscopy documented wound closure, morphology, and vimentin/CK-18 staining.

Transmission Electron Microscopy

Fetal membranes from cesarean and vaginal deliveries and fetal membrane explants from normal-term pregnancies with or without CSE exposure were fixed, stained, and embedded in PolyBed 812. Initial fixation was for 24 hours at 4°C in a fixative with 2.5% paraformaldehyde, 0.2% glutaraldehyde, and 0.03% picric acid in 0.05 mol/L cacodylate buffer. After fixation, samples were rinsed three times with cacodylate buffer and postfixed with 1% osmium tetroxide in 0.1 mol/L cacodylate buffer. Sonicated tissue was rinsed twice with deionized water and stained en bloc with 2% aqueousuranyl acetate for 1 hour at 60°C. The samples were then dehydrated by a series of ethanol-water solutions (50%, 75%, 95%, and 100% ethanol for three exchanges). Dehydrated tissue was infiltrated with two exchanges of propylene oxide, then with propylene oxide–diluted PolyBed resin at 1:1 ratio and 1:2 ratio, and then twice with pure PolyBed 812. Finally, the samples were embedded in PolyBed 812 and cured overnight at 60°C. Because precise tissue orientation could not be maintained during curing of the resin, the first resin blocks were cut to give a wide flat face for the desired sectioning plane, replaced into new embedding molds, and cured again. Samples were cut as 90-nm sections, placed on Formvar-coated slotted grids, and poststained for 3 minutes with a solution of Reynold’s lead citrate. Images were taken with a JEM 1400 electron microscope (JEOL)magnification (4000x or 1500x) (63). This value was used to calibrate the tight junction length from pixels to nanometers.

Bright field microscopy

Bright-field microscopy images were captured using a Nikon Eclipse TS100 microscope (4x, 10x, 20x) (Nikon). Three regions of interest per condition were used to determine the overall cell morphology.

Confocal microscopy

Confocal microscopy images were captured using a Zeiss 880 confocal microscope (10x,40x, or 63x) (Zeiss). Three random regions of interest per field were used to determine red (CK-18) and green (vimentin) fluorescence intensity. Uniform laser settings, brightness, contrast, and collection settings were matched for all images collected. Images were not modified (brightness, contrast, and smoothing) for intensity analysis. ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, rsbweb.nih.; version 1.51J) was used to measure vimentin and CK-18 staining intensity from two focal plans of three different regions per treatment condition at each time point. Image analysis was conducted in triplicate for all cell experiments.

Immunohistochemistry

Human fetal membrane and mice amnion sac tissue sections were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 48 hours and embedded in paraffin. Sections were cut at 5-μm thickness and adhered to a positively charged slide and attached by keeping them at 57 °C for 45 min. Slides were deparaffinized using Xylene and rehydrated with 100% alcohol, 95% alcohol, and normal saline (pH 7.4) and stained. Three images for each category were taken at 10x and 40x magnification. Images were processed with ImageJ and staining intensity was measured in a uniform manner. The following anti-human/mouse antibodies were used for immunohistochemistry: Vimentin (ab92547-Abcam), CK-18 (Abcam ab668), N-cadherin (Abcam ab98952), E-cadherin (Abcam ab15148), MMP9 (Cell Signaling Technology 13667), TGF-β (R&D Systems MAB1835), c-MYC (Cell Signaling Technology D3N8F).

Trichrome staining for collagen

Tissue sections were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 48 hours and embedded in paraffin. Sections were cut at 5-μm thickness and adhered to a positively charged slide and attached by keeping them at 57°C for 45 min. Slides were deparaffinized using Xylene and rehydrated with 100% alcohol, 95% alcohol, and normal saline (pH 7.4) and stained using the Masson Trichrome method to identify collagen components. The amnion epithelium was identified by a single layer of cells, while the ECM was identified as the area in between the amnion epithelium and the chorion layer. Three microscopic fields were captured at 10x and 40x.

Protein extraction and immunoblotting

AECs, AMCs, human, and murine tissue were lysed with RIPA lysis buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, and 1.0 mM EDTA pH 8.0, 0.1% SDS) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail and phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. After centrifugation at 10,000 RPM for 20 minutes, the supernatant was collected, and protein concentrations were determined using BCA (Pierce). The protein samples were separated using SDS-PAGE on a gradient (4–15%) Mini-PROTEAN® TGX™ Precast Gels (Bio-Rad) and transferred to the membrane using iBlot® Gel Transfer Device (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Membranes were blocked in 5% nonfat milk in 1x Tris buffered saline-Tween 20 (TBS-T) or in 5% BSA buffer for a minimum of 1 h at room temperature then probed (or re-probed) with primary antibody overnight at 4°C. The membrane was incubated with an appropriate secondary antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase and immunoreactive proteins and then visualized using Luminata Forte Western HRP substrate (Millipore). The stripping protocol followed the instructions of Restore Western Blot Stripping Buffer (Thermo Fisher). No blots were used more than three times. The following anti-human/mouse antibodies were used for western blot: N-cadherin (ab98952-abcam), E-cadherin (ab15148-abcam), vimentin (ab92547-Abcam), ZEB1 (NBP1–05987-Novus Biologicals), SNAIL (ab180714-Abcam), SLUG (ab180714-Abcam), TWIST (Abcam ab175430), c-MYC (Cell Signaling Technology D3N8F), PGRMC1 (Cell Signaling Technology D6M5M), PGRMC2 (Thermo Fisher PA5–59465), β-Actin (Sigma A5441).

Quantitative RT-PCR

To determine the expression levels of TAB1 and PGRMC2 after treatments, cells were collected and lysed using lysis buffer (Qiagen). RNA was extracted using a RNeasy kit (Qiagen) per the manufacturer’s instructions. Total RNA (500ng) was reverse-transcribed using a High-Capacity RNA-to-cDNA Kit (Applied Biosystems). qRT-PCR was performed on an ABI7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) using Fast SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). The amplification thermal profile was 20s at 95°C and 3s 95°C, followed by 30s 60°C (40 cycles). To confirm the presence of a single amplicon, a melt curve was carried out: 15 s at 95°C, 1 min at 60°C, 15 s at 95°C, and 15s at 60°C. Changes in gene expression levels were calculated by using the ΔΔCt method. We used predesigned qPCR assays from Integrated DNA Technologies (table S4).

Immunocytochemical localization of intermediate filaments cytokeratin and vimentin

Immunocytochemical staining for vimentin (3.7 μl/mL; ab92547; Abcam) and CK-18 (1 μl/mL; ab668, Abcam) were performed for multiple experimental endpoints (13). Additionally, vimentin and CK-18 were measured during PGRMC2 overexpression studies. Manufacturer’s instructions were used to calculate staining dilutions to ensure uniform staining. After each time point, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X, and blocked with 3% BSA in PBS prior to incubation with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C (38). This protocol is adequate to remove non-specific binding of primary antibodies in our system. After washing with PBS, slides were incubated with Alexa Fluor 488 and 594 conjugated secondary antibodies (Life Technologies), diluted 1:1000 in PBS, for 1 hour in the dark. Slides were washed with PBS, treated with NucBlue® Live ReadyProbes® Reagent (Life Technologies) and then mounted using Mowiol 4–88 mounting medium (Sigma).

Crystal violet cell viability assay

To document cell viability after 6 day treatments, AECs and AMCs were seed in a 12-well plate and treated as described above. After 6 days, cells were washed with 1× PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min, washed with water, and stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 20 min. After 20 min, cells are washed, allowed to dry, and 10% acetic acid was added to each well. A 1:4 dilution of the colored supernatant was measured at an absorbance of 590 nm.

Cell shape index quantification

The cell shape index was determined for AEC and AMC cultures by evaluating one frame from each N (total of 3 images) per treatment for cell circularity using ImageJ software. The shape index was calculated using the following formula: SI=4π*Area/Perimeter2, which is an established method that was originally reported to determine vascular cell shape (64). A circle would have a shape index of 1; a straight line an index of 0.

TGF-β ELISA

Human amniotic fluid was collected at term vaginal deliveries (term labor), term-not-in-labor caesarian deliveries (term not in labor), preterm premature rupture of membrane (pPROM), spontaneous preterm births (STB), and a human/mouse TGF-β 1 ELISA Ready-SET-Go! ELISA (second generation) (Affymetrix eBioscience) was conducted following the manufacturer’s instructions. Standard curves were developed with recombinant protein samples of known quantities. Sample concentrations were determined by correlating the samples absorbance to the standard curve by linear regression analysis.

Statistics

Statistical analyses for normally distributed data was performed using an ANOVA with the Tukey Multiple Comparisons Test and T-test. Statistical values were calculated using PRISM. P values of less than 0.05 were considered significant. Data is represented as Mean±SEM.

Supplementary Material

Fig. S1. Mesenchymal transcription factor and p38 MAPK expression at term labor in human and mice models

Fig. S2. TGF-β associated changes in AECs

Fig. S3. P4 and P4 receptor associated changes in AMCs and AECs

Fig. S4. AMC qualities at term

Fig. S5: Original Western blot images for human tissue

Fig. S6: Original Western blot images for mouse tissue

Fig. S7: Original Western blot images for cell culture

Table S1. Oxidative stress–induced changes in pregnant CD-1 mice

Table S2. siRNA sequences

Table S3. Plasmid sequence for GFP-PGRMC2

Table S4. qRT-PCR primer sequences

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Laura F. Martin and Jayshil Trivedi for collecting clinical samples and helping conduct immunohistochemistry and western blots of fetal membrane explants. We would also like to thank Dr. Brandie Taylor for reviewing our raw data and statistical test for accuracy.

Funding: Lauren Richardson is an appointed Pre-doctoral Trainee in the Environmental Toxicology (ETox) Training Program (T32ES007254), supported by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) of the United States, and administered through the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston, Texas. This study is supported by the NIH/NICHD (1R03HD098469-01) to R. Menon.

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper or the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Materials

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Parry S, and Strauss JF 3rd. 1998. Premature rupture of the fetal membranes. N Engl J Med 338: 663–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richardson LS, Vargas G, Brown T, Ochoa L, Sheller-Miller S, Saade GR, Taylor RN, and Menon R Discovery and Characterization of Human Amniochorionic Membrane Microfractures. The American Journal of Pathology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bryant-Greenwood GD 1998. The extracellular matrix of the human fetal membranes: structure and function. Placenta 19: 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casey ML, Winkel CA, Porter JC, and MacDonald PC 1983. Endocrine regulation of the initiation and maintenance of parturition. Clin Perinatol 10: 709–721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu W, Shi SQ, Huang HJ, Balducci J, and Garfield RE 2011. Changes in PGRMC1, a potential progesterone receptor, in human myometrium during pregnancy and labour at term and preterm. Mol Hum Reprod 17: 233–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ulm B, Ulm MR, and Bernaschek G 1999. Unfused amnion and chorion after 14 weeks of gestation: associated fetal structural and chromosomal abnormalities. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 13: 392–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richardson L, and Menon R 2018. Proliferative, Migratory, and Transition Properties Reveal Metastate of Human Amnion Cells. Am J Pathol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonney EA, Krebs K, Saade G, Kechichian T, Trivedi J, Huaizhi Y, and Menon R 2016. Differential senescence in feto-maternal tissues during mouse pregnancy. Placenta 43: 26–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feng L, Allen TK, Marinello WP, and Murtha AP 2018. Roles of Progesterone Receptor Membrane Component 1 in Oxidative Stress-Induced Aging in Chorion Cells. Reprod Sci: 1933719118776790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mogami H, Kishore AH, and Word RA 2018. Collagen Type 1 Accelerates Healing of Ruptured Fetal Membranes. Sci Rep 8: 696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caughey AB, Robinson JN, and Norwitz ER 2008. Contemporary diagnosis and management of preterm premature rupture of membranes. Rev Obstet Gynecol 1: 11–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rennie K, Gruslin A, Hengstschlager M, Pei D, Cai J, Nikaido T, and Bani-Yaghoub M 2012. Applications of amniotic membrane and fluid in stem cell biology and regenerative medicine. Stem Cells Int 2012: 721538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roy R, Kukucka M, Messroghli D, Kunkel D, Brodarac A, Klose K, Geissler S, Becher PM, Kang SK, Choi YH, and Stamm C 2015. Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition Enhances the Cardioprotective Capacity of Human Amniotic Epithelial Cells. Cell Transplant 24: 985–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang LL, Jiang XM, Huang MY, Feng ZL, Chen X, Wang Y, Li H, Li A, Lin LG, and Lu JJ 2019. Nagilactone E suppresses TGF-beta1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition, migration and invasion in non-small cell lung cancer cells. Phytomedicine 52: 32–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ooshima A, Park J, and Kim SJ 2018. Phosphorylation status at Smad3 linker region modulates TGF-beta-induced EMT and cancer progression. Cancer Sci. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Canciello A, Russo V, Berardinelli P, Bernabo N, Muttini A, Mattioli M, and Barboni B 2017. Progesterone prevents epithelial-mesenchymal transition of ovine amniotic epithelial cells and enhances their immunomodulatory properties. Sci Rep 7: 3761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richardson L, Dixon CL, Aguilera-Aguirre L, and Menon R 2018. Oxidative Stress-Induced TGF-beta/TAB1-mediated p38MAPK activation in human amnion epithelial cells. Biol Reprod. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kalluri R, and Weinberg RA 2009. The basics of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Clin Invest 119: 1420–1428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pastushenko I, and Blanpain C 2018. EMT Transition States during Tumor Progression and Metastasis. Trends Cell Biol. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lamouille S, Xu J, and Derynck R 2014. Molecular mechanisms of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 15: 178–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee JM, Dedhar S, Kalluri R, and Thompson EW 2006. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition: new insights in signaling, development, and disease. J Cell Biol 172: 973–981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu CY, Lin HH, Tang MJ, and Wang YK 2015. Vimentin contributes to epithelial-mesenchymal transition cancer cell mechanics by mediating cytoskeletal organization and focal adhesion maturation. Oncotarget 6: 15966–15983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Menon R, Boldogh I, Hawkins HK, Woodson M, Polettini J, Syed TA, Fortunato SJ, Saade GR, Papaconstantinou J, and Taylor RN 2014. Histological evidence of oxidative stress and premature senescence in preterm premature rupture of the human fetal membranes recapitulated in vitro. American Journal of Pathology 184: 1740–1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carnevali S, Petruzzelli S, Longoni B, Vanacore R, Barale R, Cipollini M, Scatena F, Paggiaro P, Celi A, and Giuntini C 2003. Cigarette smoke extract induces oxidative stress and apoptosis in human lung fibroblasts. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 284: L955–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang LY, Wang WS, Wang YW, Lu JW, Lu Y, Zhang CY, Li WJ, Sun K, and Ying H 2019. Drastic induction of MMP-7 by cortisol in the human amnion: implications for membrane rupture at parturition. Faseb j 33: 2770–2781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gravdal K, Halvorsen OJ, Haukaas SA, and Akslen LA 2007. A switch from E-cadherin to N-cadherin expression indicates epithelial to mesenchymal transition and is of strong and independent importance for the progress of prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res 13: 7003–7011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Menon R, Boldogh I, Urrabaz-Garza R, Polettini J, Syed TA, Saade GR, Papaconstantinou J, and Taylor RN 2013. Senescence of primary amniotic cells via oxidative DNA damage. PLoS ONE [Electronic Resource] 8: e83416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jin J, Richardson L, Sheller-Miller S, Zhong N, and Menon R 2018. Oxidative stress induces p38MAPK-dependent senescence in the feto-maternal interface cells. Placenta 67: 15–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Polettini J, Richardson LS, and Menon R 2018. Oxidative stress induces senescence and sterile inflammation in murine amniotic cavity. Placenta 63: 26–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Menon R, Behnia F, Polettini J, Saade GR, Campisi J, and Velarde M 2016. Placental membrane aging and HMGB1 signaling associated with human parturition. Aging (Albany NY) 8: 216–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ayad MT, Taylor BD, and Menon R 2018. Regulation of p38 mitogen-activated kinase-mediated fetal membrane senescence by statins. Am J Reprod Immunol 80: e12999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alcaraz A, Mrowiec A, Insausti CL, Bernabe-Garcia A, Garcia-Vizcaino EM, Lopez-Martinez MC, Monfort A, Izeta A, Moraleda JM, Castellanos G, and Nicolas FJ 2015. Amniotic Membrane Modifies the Genetic Program Induced by TGFss, Stimulating Keratinocyte Proliferation and Migration in Chronic Wounds. PLoS One 10: e0135324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alcaraz A, Mrowiec A, Insausti CL, Garcia-Vizcaino EM, Ruiz-Canada C, Lopez-Martinez MC, Moraleda JM, and Nicolas FJ 2013. Autocrine TGF-beta induces epithelial to mesenchymal transition in human amniotic epithelial cells. Cell Transplant 22: 1351–1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Behnia F, Taylor BD, Woodson M, Kacerovsky M, Hawkins H, Fortunato SJ, Saade GR, and Menon R 2015. Chorioamniotic membrane senescence: a signal for parturition? Am J Obstet Gynecol 213: 359.e351–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Menon R 2014. Oxidative stress damage as a detrimental factor in preterm birth pathology. Frontiers in Immunology 5: 567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dutta EH, Behnia F, Boldogh I, Saade GR, Taylor BD, Kacerovsky M, and Menon R 2016. Oxidative stress damage-associated molecular signaling pathways differentiate spontaneous preterm birth and preterm premature rupture of the membranes. Mol Hum Reprod 22: 143–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Menon R, and Papaconstantinou J 2016. p38 Mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK): a new therapeutic target for reducing the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Expert Opin Ther Targets 20: 1397–1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Feoktistova M, Geserick P, and Leverkus M 2016. Crystal Violet Assay for Determining Viability of Cultured Cells. Cold Spring Harb Protoc 2016: pdb.prot087379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fink KL, Wieben ED, Woloschak GE, and Spelsberg TC 1988. Rapid regulation of c-myc protooncogene expression by progesterone in the avian oviduct. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 85: 1796–1800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Janzen C, Sen S, Lei MY, Gagliardi de Assumpcao M, Challis J, and Chaudhuri G 2017. The Role of Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition in Human Amniotic Membrane Rupture. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 102: 1261–1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang Y, Alexander PB, and Wang XF 2017. TGF-beta Family Signaling in the Control of Cell Proliferation and Survival. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sheller S, Papaconstantinou J, Urrabaz-Garza R, Richardson L, Saade G, Salomon C, and Menon R 2016. Amnion-Epithelial-Cell-Derived Exosomes Demonstrate Physiologic State of Cell under Oxidative Stress. PLoS One 11: e0157614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ko E, Lee KY, and Hwang DS 2012. Human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells undergo cellular senescence in response to oxidative stress. Stem Cells Dev 21: 1877–1886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Orciani M, Gorbi S, Benedetti M, Di Benedetto G, Mattioli-Belmonte M, Regoli F, and Di Primio R 2010. Oxidative stress defense in human-skin-derived mesenchymal stem cells versus human keratinocytes: Different mechanisms of protection and cell selection. Free Radic Biol Med 49: 830–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Denu RA, and Hematti P 2016. Effects of Oxidative Stress on Mesenchymal Stem Cell Biology. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2016: 2989076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ichikawa-Tomikawa N, Sugimoto K, Satohisa S, Nishiura K, and Chiba H 2011. Possible involvement of tight junctions, extracellular matrix and nuclear receptors in epithelial differentiation. J Biomed Biotechnol 2011: 253048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yan W, Xiaoli L, Guoliang A, Zhonghui Z, Di L, Ximeng L, Piye N, Li C, and Lin T 2016. SB203580 inhibits epithelial-mesenchymal transition and pulmonary fibrosis in a rat silicosis model. Toxicol Lett 259: 28–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lin Y, Mallen-St Clair J, Wang G, Luo J, Palma-Diaz F, Lai C, Elashoff DA, Sharma S, Dubinett SM, and St John M 2016. p38 MAPK mediates epithelial-mesenchymal transition by regulating p38IP and Snail in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol 60: 81–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Witte D, Otterbein H, Forster M, Giehl K, Zeiser R, Lehnert H, and Ungefroren H 2017. Negative regulation of TGF-beta1-induced MKK6-p38 and MEK-ERK signalling and epithelial-mesenchymal transition by Rac1b. Sci Rep 7: 17313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li NY, Weber CE, Wai PY, Cuevas BD, Zhang J, Kuo PC, and Mi Z 2013. An MAPK-dependent pathway induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition via Twist activation in human breast cancer cell lines. Surgery 154: 404–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bredeson S, Papaconstantinou J, Deford JH, Kechichian T, Syed TA, Saade GR, and Menon R 2014. HMGB1 promotes a p38MAPK associated non-infectious inflammatory response pathway in human fetal membranes. PLoS ONE [Electronic Resource] 9: e113799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Polettini J, Behnia F, Taylor BD, Saade GR, Taylor RN, and Menon R 2015. Telomere Fragment Induced Amnion Cell Senescence: A Contributor to Parturition? PLoS ONE [Electronic Resource] 10: e0137188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li Y, Zhang D, Xu L, Dong L, Zheng J, Lin Y, Huang J, Zhang Y, Tao Y, Zang X, Li D, and Du M 2019. Cell-cell contact with proinflammatory macrophages enhances the immunotherapeutic effect of mesenchymal stem cells in two abortion models. Cell Mol Immunol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Meng Y, Murtha AP, and Feng L 2016. Progesterone, Inflammatory Cytokine (TNF-alpha), and Oxidative Stress (H2O2) Regulate Progesterone Receptor Membrane Component 1 Expression in Fetal Membrane Cells. Reprod Sci 23: 1168–1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sato BL, Collier ES, Vermudez SA, Junker AD, and Kendal-Wright CE 2016. Human amnion mesenchymal cells are pro-inflammatory when activated by the Toll-like receptor 2/6 ligand, macrophage-activating lipoprotein-2. Placenta 44: 69–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sun K, Ma R, Cui X, Campos B, Webster R, Brockman D, and Myatt L 2003. Glucocorticoids induce cytosolic phospholipase A2 and prostaglandin H synthase type 2 but not microsomal prostaglandin E synthase (PGES) and cytosolic PGES expression in cultured primary human amnion cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88: 5564–5571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]