Abstract

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a common outcome evaluated in clinical studies, often as a safety endpoint in a variety of cardiovascular, kidney disease, and other clinical trials. AKI endpoints that include modest rises in serum creatinine from baseline may not associate with patient-centered outcomes such as initiation of dialysis, sustained decline in kidney function, or death. Surprisingly, data from several randomized controlled trials have suggested that in certain settings, the development of AKI may be associated with favorable outcomes. AKI safety endpoints that are non-specific and may not associate with patient-centered outcomes could result in beneficial therapies being inappropriately withheld or never developed for commercial use. Here we review several issues related to commonly employed AKI definitions and suggest that future work in AKI use more patient-centered AKI endpoints such as major adverse kidney events at 30 days (MAKE30) or other later time points.

Keywords: Acute kidney injury (AKI), acute renal failure (ARF), clinical trials, safety, patient-centered outcome (PCO), serum creatinine (Scr), hemodynamics, trial end point, safety signal, kidney function, AKI definition, acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF), blood pressure control, kidney damage, biomarker, prognosis, major adverse kidney events (MAKE), surrogate outcome

Introduction

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is generally defined by increases in serum creatinine (Scr), decreases in urine output, and changes in urine biomarkers – none of which are particularly meaningful to patients. Clinical researchers increasingly recognize the need to re-focus investigation on patient-centered outcomes (PCOs). In the United States, the Affordable Care Act established the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) in 2010 to research “questions and outcomes meaningful and important to patients and caregivers”1. Outcomes including mortality, the need for dialysis in-hospital, and the development of chronic kidney disease (particularly kidney failure) longer-term are most meaningful to patients. Thus, it is imperative that, if AKI is to be used as a safety endpoint in clinical practice or research, we be reasonably certain that our definition of AKI contributes to these undesirable PCOs.

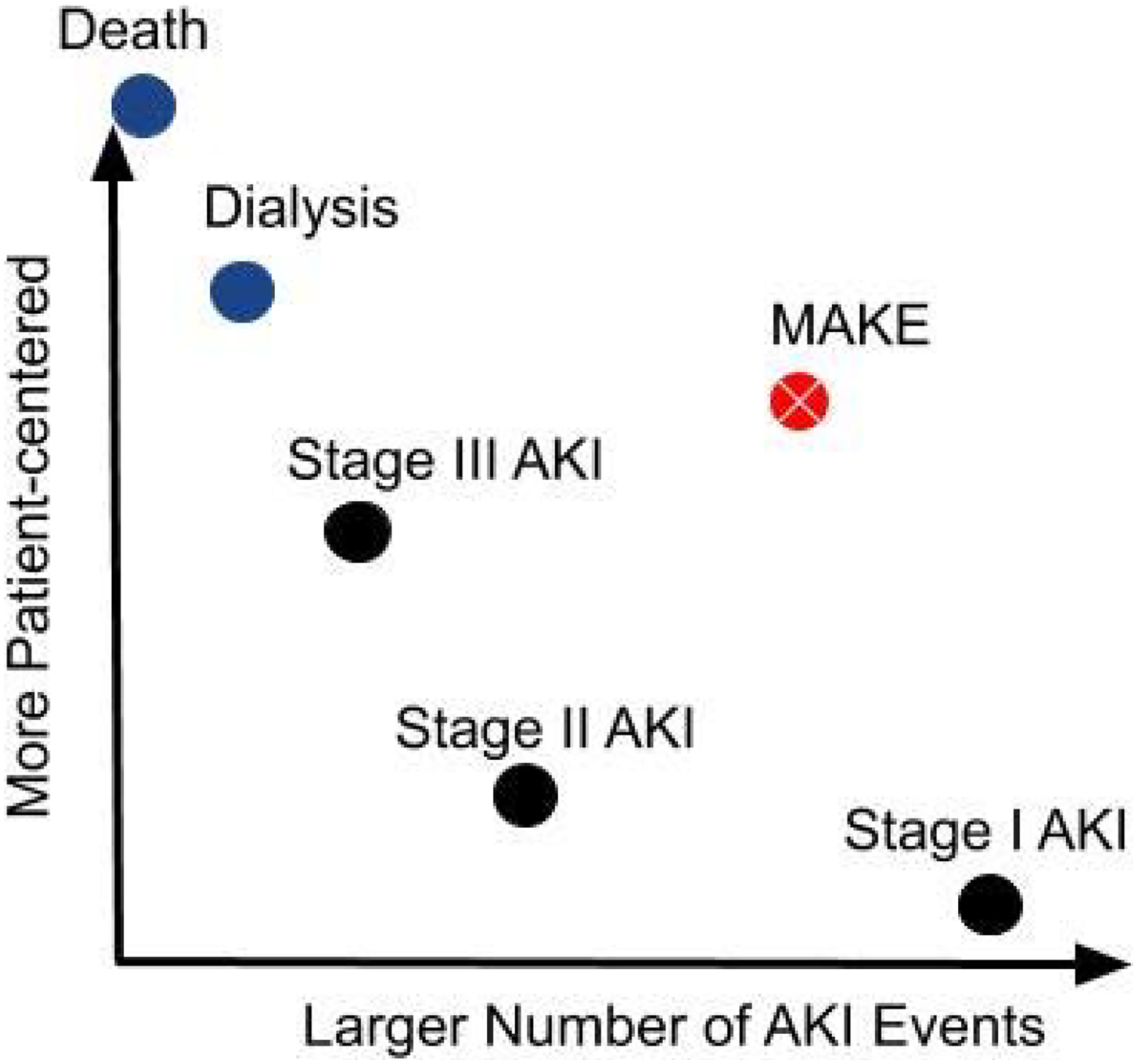

Investigators have a number of options when choosing an AKI definition for a particular study. Even though some consensus has been brought to AKI definitions by groups like ADQI (the Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative) in 20042 and KDIGO (Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes) in 20123, AKI is rarely defined exactly the same way twice. Each study examining AKI as a safety endpoint determines whether to use Scr-based criteria, urine output-based criteria, or less commonly urine biomarkers or dialysis initiation. Studies employing patient-centered AKI definitions require larger numbers of patients or longer periods of follow-up in order to be adequately powered. Each group of investigators chooses an AKI definition based on the balance it wishes to strike between patient-centeredness and the number of events they expect to observe (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual tradeoffs between patient-centeredness and number of events of various AKI endpoints.

AKI: acute kidney injury; MAKE: major adverse kidney events.

Even mild AKI has been associated with less favorable PCOs in a robust observational literature, but numerous examples from randomized controlled trial data question the clinical significance of modest rises in serum creatinine. Here we review origins of current AKI definitions and highlight recent examples from the literature where these definitions of AKI are either not associated with PCOs or are paradoxically associated with more favorable PCOs.

Origin of the Scr Cutoff in the AKI Definition

Most investigators choose to define AKI by the serum creatinine-based criterion of a ≥ 0.3 mg/dL or 1.5x increase in serum creatinine from baseline (stage 1 AKI or higher) as recommended by KDIGO 3. This 0.3 mg/dL value originated from a 2005 paper examining 9,205 patient records at Brigham and Women’s hospital in Boston between 1997 and 19984. An increase of ≥ 0.3 mg/dL in serum creatinine was associated with an adjusted odds ratio (OR) of 4.1 (95% confidence interval (CI), 3.1–5.5) for mortality. This high OR for mortality highlights the sensitivity of kidney function as a marker of mortality, but the association by no means indicates causation. Nevertheless, this association with mortality has been replicated in innumerable observational datasets, and thus the 0.3 mg/dL increase in serum creatinine was incorporated into consensus AKI definitions in 2007 (Acute Kidney Injury Network [AKIN]) and in 2012 (KDIGO). While these definitions distinguish mild (“stage 1”) AKI from the more severe stages 2 and 3 AKI, researchers frequently use AKI of any stage as an endpoint.

AKI and Patient-centered Outcomes

Acute Decompensated Heart Failure (ADHF)

Diuresis is the foundational treatment of ADHF, whether associated with reduced or preserved ejection fraction, and diuretic use is associated with AKI in randomized controlled trials5,6. However, mild AKI in this context is not associated with adverse outcomes.

In data from the ROSE-AHF (Renal Optimization Strategies Evaluation in Acute Heart Failure) trial on 283 patients with heart failure receiving high dose intravenous loop diuretics, worsening kidney function was assessed by serum creatinine, serum cystatin C, and urinary biomarkers (Table 1). Diuretic-induced AKI (whether defined by changes in serum creatinine or cystatin C) was not associated with elevated urinary biomarkers, suggesting these mild AKI episodes may reflect changes in hemodynamics rather than intrinsic damage to the kidney. Surprisingly, the development of AKI was associated with improved survival. In fact, patients with more indicators of AKI (rises in both serum cystatin C and urinary biomarkers) had the best prognosis, while patients with fewer indicators of AKI (stable or decreased cystatin C and urinary biomarkers) had the worst survival7.

Table 1.

Randomized controlled trial data questioning the clinical significance of mild to moderate increases in Scr

| Study | Patients in AKI analysis | Intervention | AKI Definitions/Metrics | AKI Prognosis? | Protocolized Dose Reduction for AKI? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROSE-AHF (N = 360 w/ acute HF and CKDa) | 283 w/ BL and 72 h serum and urinary biomarkers | All given high-dose IV loop diuretics, additionally randomized to placebo, nesiritide, or dopamine | Assessed by increases in Scr, Scys, and urinary biomarkers (NGAL, NAG, KIM-1)b | Survival paradoxically higher in patients w/ AKI (by Scr, Scys, or urinary biomarkers) | No (clinicians could change diuretic doses every 24 h) |

| DOSE (N = 308 w/ acute on chronic HF) | 301 w/ at least one Scr other than BL | 2 × 2 factorial randomized to low vs high dose diuretics and bolus vs continuous infusion | ΔScr from admission to 72 h (as a continuous variable and also w/ ≥0.3 mg/dL cutoff) | Risk of death, rehospitalization, or ED visit decreased (HR per 0.3 mg/dL increase in Scr, 0.81; p=0.026) | No (clinicians could change to any dose of oral diuretic at 48 h if patient deemed to have had an adequate response) |

| CARRESS-HF (N = 188 w/ acute HF and Scr ≥ 0.3 mg/dL above BL) | 105 w/ urinary biomarkers | Stepped diuretic therapy vs ultrafiltration | ≥ 20% reduction in eGFR or increase in urinary biomarkers at 4 d post-randomization | Recovery of kidney function at 60 d post-randomization more frequent among patients w/ AKI | No (diuretics could be decreased or temporarily held for an increase in Scr felt to be due to a transient episode of intravascular volume depletion) |

| RENAAL (N = 1513 w/ T2DM and nephropathy) | 1435 still in study at 3 mo; 719 in losartan group | Losartan vs placebo | ΔeGFR from randomization to mo 3 | Patients w/ larger initial fall in eGFR had lower long-term eGFR slope from 3 mo to final visit (at median of 33 mo) | No (increased Scr led to the discontinuation of the study medication in <1.5%) |

| SPRINT (N=9361 w/ hypertension and increased CV risk) | 8526 w/ data on early eGFR decline | SBP target < 120 mmHg vs < 140 mmHg | % eGFR decline from BL at 6 mo | No interaction between eGFR decline and the benefit of intensive SBP lowering on CV and all-cause mortality | No |

| ADVANCE (N = 11140 w/ T2DM and increased risk of vascular disease) | 11066 w/ 2 Scrs before and during the 6 wk run-in period (3 wk apart) | Perindopril-indapamide vs placebo | % change in Scr during run-in period | No evidence of heterogeneity in the benefit of randomized treatment effects on the outcome across subgroups defined by acute Scr increase | No (1.0% and 1.4% excluded during run-in period for ‘other suspected intolerance’ and ‘other reasons’, respectively) |

| SOLVD (N = 6797 w/ left ventricular ejection fraction ≤ 35%) | 6337 w/ data on kidney function at BL and 14 d post-randomization | Enalapril vs placebo | Decrease in eGFR ≥20% at 14 d | Survival advantage of enalapril over placebo more pronounced in patients w/ worsening kidney function | No (3 wk run-in: 0.2% of patients excluded for worsening kidney function) |

Scr, serum creatinine; Scys, serum cystatin C; HF, heart failure; CKD, chronic kidney disease; BL, baseline; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; CV, cardiovascular; Δ, change; ED, emergency department

eGFR 15–60 ml/min/1.73 m2 on admission

NGAL: neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin; NAG: N-acetyl-β-d-glucosaminidase; KIM-1: kidney injury molecule 1.

Data from the DOSE (Diuretic Optimization Strategies Evaluation) trial tell a similar story. In this trial, patients with ADHF were randomized in a 2 × 2 factorial design to high versus low dose loop diuretics delivered by continuous infusion versus bolus dosing. As serum creatinine increased, the risk of the composite primary endpoint (death, rehospitalization, or emergency room visit) decreased (hazard ratio (HR) per 0.3 mg/dL increase in serum creatinine of 0.81, p=0.026). When the 0.3 mg/dL cutoff was used, a ≥ 0.3 mg/dL increase in serum creatinine was not associated with the composite primary endpoint, whereas a ≥ 0.3 mg/dL decrease in serum creatinine was associated with higher risk 8.

Finally, CARRESS-HF (Cardiorenal Rescue Study in Acute Decompensated Heart Failure), a randomized controlled trial that compared stepped pharmacotherapy with fixed-rate ultrafiltration, diminished enthusiasm for ultrafiltration due to an AKI safety signal in the ultrafiltration group. However, a post hoc analysis of the data showed that patients who had worsening kidney function during the intervention period enjoyed better kidney function at 60 days, regardless of treatment group9.

These studies suggest that AKI, defined by small to moderate increases in serum creatinine, is not a valid proxy for PCOs in ADHF. In this clinical setting, a modest increase in serum creatinine could reflect adequate decongestion rather than an adverse event.

After Initiation of Outpatient Antihypertensive Therapy

In the outpatient setting, AKI cannot be diagnosed by formal criteria because multiple serum creatinine measurements are rarely obtained within a period of several days. Nevertheless, subacute elevations in serum creatinine measured weeks to months apart are viewed as adverse clinical events and often precipitate medication changes and/or referral to nephrology. While the idea that a rise in serum creatinine predicts adverse outcomes may hold true in general, we can again find notable exceptions where rises in serum creatinine associate with more favorable PCOs.

A post hoc analysis of the RENAAL (Reduction of Endpoints in Non-Insulin-Dependent Diabetes Mellitus with the Angiotensin II Antagonist Losartan) trial showed that patients who had the largest acute reductions in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) after starting losartan also had the least steep downward slope in eGFR long-term10. In other words, patients with an acute rise in Scr experienced slower progression of chronic kidney disease (CKD).

Similar results were seen when examining the effect of more intensive blood pressure control on cardiovascular outcomes and mortality. In SPRINT (Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial), a randomized controlled trial comparing a systolic blood pressure target of < 120 mmHg versus < 140 mmHg, more intensive systolic blood pressure lowering decreased cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality, but resulted in more AKI events (defined by increases in serum creatinine, the majority of which were modest in magnitude). However, a post hoc analysis of SPRINT showed that patients with acute rises in serum creatinine received the same benefit from the blood pressure lowering intervention as did patients with stable or decreased serum creatinine11.

An analysis of data from the ADVANCE (Action in Diabetes and Vascular Disease: Preterax and Diamicron Modified Release Controlled Evaluation) trial showed an acute rise in serum creatinine after perindopril-indapamide initiation was associated with worsened PCOs including all-cause mortality and major macrovascular events12. However, similar to the analysis of SPRINT, there was no evidence of heterogeneity in the benefit of randomized treatment across subgroups defined by the acute increase in serum creatinine. In other words, randomization to active treatment instead of placebo decreased the risk of PCOs regardless of whether there was an acute increase in serum creatinine.

Finally, reanalysis of data from SOLVD (Studies of Left Ventricular Dysfunction) showed an association between an acute rise in serum creatinine after randomized treatment with enalapril and mortality13. However, when the treatment arms were analyzed separately, mortality associated with worsening kidney function was restricted to patients in the placebo group. Among patients randomized to enalapril, an acute rise in serum creatinine had no adverse prognostic significance. Furthermore, among patients who continued the study drug, the survival advantage of enalapril over placebo was more pronounced in patients with worsening kidney function (adjusted HR, 0.7; 95% CI, 0.5–0.9) than in patients without (adjusted HR, 0.9; 95% CI, 0.8–1.0). In SOLVD, AKI observed without intervention (placebo) was a poor prognostic sign, whereas AKI after an intervention (enalapril) was a favorable prognostic sign.

Thus, while modest increases in serum creatinine after outpatient initiation or intensification of antihypertensive or vasodilator therapy are markers of poorer prognosis in observational data14, data from the trials summarized above suggest these increases in serum creatinine do not indicate lesser benefit from the interventions. It has even been suggested this type of acute rise in creatinine be termed “acute renal success” rather than acute renal failure or acute kidney injury15. Taken together, high quality data from randomized clinical trials demonstrate that acute modest increases in serum creatinine are not valid PCOs. One should note that, while study protocols did not explicitly require dose reduction or discontinuation of study medication for AKI, clinicians in these trials may well have reduced or stopped the study medication if severe enough AKI occurred. Thus, conclusions from these trial data must be limited to the mild to moderate AKI events observed.

Variation by Different Clinical Contexts

As stated above, AKI has been associated with morbidity and mortality in numerous epidemiologic studies4,16–18. Many clinical trials adopt AKI as a safety endpoint because of this robust literature. However, AKI is not a specific disease, but rather a clinical entity with many different etiologies19. The association of AKI with PCOs differs based on the underlying etiology and clinical context. For instance, AKI after cardiac surgery is associated with a higher risk for mortality (relative risk (RR), 5.46; 95% CI, 1.87–15.95) than is AKI in the general intensive care unit (RR, 1.77; 95% CI, 1.39–2.26)20. Urinary biomarkers can distinguish subtypes of intrinsic AKI from AKI caused by decreased kidney perfusion (as defined by clinical context and improvement with fluids), and the risk of death or provision of dialysis during an inpatient stay is higher in intrinsic AKI than in AKI from decreased kidney perfusion21. Because of the heterogeneity of prognoses associated with AKI, researchers should be careful when choosing a definition of AKI depending on the clinical context being studied.

Patient-centered AKI Definitions

AKI definitions that include mild increases in serum creatinine do not consistently associate with PCOs – but what are the alternatives? The search for a urinary biomarker of AKI could identify an analyte that correlates better with PCOs; until then, clinical researchers need more patient-centered AKI definitions. In 2012, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) workgroup on clinical trials in AKI recommended using “a composite endpoint of death, provision of dialysis, or sustained loss of kidney function” for Phase III trials related to AKI22. Such an endpoint has been formalized as MAKE (major adverse kidney events), analogous to cardiology’s MACE (major adverse cardiovascular events: classically non-fatal stroke, non-fatal myocardial infarction, and cardiovascular death). MAKE is often defined as “death, dialysis, or doubling of creatinine,” which has long been used in CKD progression research, now applied at a shorter duration for AKI studies (e.g., MAKE30 applies this endpoint at 30 days). MAKE is more patient-centered: outcomes like death and dialysis clearly matter to patients and the serum creatinine criterion is more specific than criteria commonly used to define stage 1 AKI. To meet a MAKE endpoint by serum creatinine, not only must the serum creatinine double, but also the doubling of serum creatinine must be sustained (often until discharge, or 30 days, etc.). These two features make the serum creatinine criterion of MAKE more specific for PCOs, while potentially allowing for greater power (due to a larger number of events – if all components of the composite are directionally consistent) than an endpoint based on death or dialysis alone. MAKE has been used in a few randomized controlled trials in AKI23,24 and is slowly making its way into observational literature as well25–27. However, additional work is still needed to evaluate the patient-centeredness of the ‘doubling of creatinine’ criterion, which is often the most common MAKE criterion met. Future work may identify better endpoints that incorporate etiology and clinical context (e.g., suspected hemodynamic versus parenchymal injury).

Conclusion

We have learned that AKI is associated with mortality in some clinical contexts 4,16–18, and with survival in others7,8,13. From kidney transcriptomics and urinary proteomics, we know different etiologies of AKI lead to distinct genetic signatures.28 As we aim to unravel the distinct pathophysiologic pathways behind various causes of AKI and to define biologically and clinically relevant AKI subtypes, we suggest that stage 1 AKI should not be considered a valid proxy for a patient-centered safety endpoint. The 0.3 mg/dL serum creatinine cutoff is overly sensitive and poorly specific when considering PCOs as the standard. Random laboratory error (even with modern enzymatic methods traceable to isotope-diluation mass spectrometry), combined with intra-individual biological variability, can result in 0.3 mg/dL changes in serum creatinine without any change in GFR29. Real harm may arise from the use of stage 1 AKI as a safety endpoint – drugs whose benefits are already proven may be held or discontinued due to concern for patient harm30 and drugs in development may be placed on the proverbial shelf for insufficient cause. More work is needed to determine the best safety endpoint for kidney function. Until the underlying biology is clearer, clinical research on AKI should avoid definitions including modest increases in serum creatinine in favor of more patient-centered endpoints, potentially including MAKE30, MAKE60, or MAKE90.

Support:

Dr. McCoy was supported by a NIH T-32 grant (5T32DK007357), and Dr. Chertow was supported by a NIH K-24 grant (2K24DK085446). The funder had no role in defining the content of the article.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial Disclosure: The authors declare that they have no relevant financial interests.

References

- 1.Frank L, Basch E, Selby JV. The PCORI Perspective on Patient-Centered Outcomes Research. JAMA. 2014;312(15):1513. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.11100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bellomo R, Ronco C, Kellum JA, Mehta RL, Palevsky P, Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative workgroup. Acute renal failure - definition, outcome measures, animal models, fluid therapy and information technology needs: the Second International Consensus Conference of the Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative (ADQI) Group. Crit Care. 2004;8(4):R204–12. doi: 10.1186/cc2872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Acute Kidney Injury Working Group. KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for Acute Kidney Injury. Kidney Int Suppl. 2012;2(1):1–138. doi: 10.1038/kisup.2012.7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chertow GM, Burdick E, Honour M, Bonventre JV, Bates DW. Acute Kidney Injury, Mortality, Length of Stay, and Costs in Hospitalized Patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(11):3365–3370. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004090740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grams ME, Estrella MM, Coresh J, Brower RG, Liu KD. Fluid balance, diuretic use, and mortality in acute kidney injury. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(5):966–973. doi: 10.2215/CJN.08781010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Felker GM, Lee KL, Bull DA, et al. Diuretic Strategies in Patients with Acute Decompensated Heart Failure. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(9):797–805. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1005419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahmad T, Jackson K, Rao VS, et al. Worsening Renal Function in Patients With Acute Heart Failure Undergoing Aggressive Diuresis Is Not Associated With Tubular Injury. Circulation. 2018;137(19):2016–2028. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.030112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brisco MA, Zile MR, Hanberg JS, et al. Relevance of Changes in Serum Creatinine During a Heart Failure Trial of Decongestive Strategies: Insights From the DOSE Trial. J Card Fail. 2016;22(10):753–760. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2016.06.423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rao VS, Ahmad T, Brisco-Bacik MA, et al. Renal Effects of Intensive Volume Removal in Heart Failure Patients With Preexisting Worsening Renal Function. Circ Heart Fail. 2019;12(6):e005552. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.118.005552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holtkamp FA, De Zeeuw D, Thomas MC, et al. An acute fall in estimated glomerular filtration rate during treatment with losartan predicts a slower decrease in long-term renal function. Kidney Int. 2011;80(3):282–287. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beddhu S, Shen J, Cheung AK, et al. Implications of Early Decline in eGFR due to Intensive BP Control for Cardiovascular Outcomes in SPRINT. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;30(8):1523–1533. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2018121261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ohkuma T, Jun M, Rodgers A, et al. Acute Increases in Serum Creatinine After Starting Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitor-Based Therapy and Effects of its Continuation on Major Clinical Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Hypertension. 2019;73(1):84–91. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.12060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Testani JM, Kimmel SE, Dries DL, Coca SG. Prognostic importance of early worsening renal function after initiation of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy in patients with cardiac dysfunction. Circ Hear Fail. 2011;4(6):685–691. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.111.963256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fu EL, Trevisan M, Clase CM, et al. Association of Acute Increases in Plasma Creatinine after Renin-Angiotensin Blockade with Subsequent Outcomes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. August 2019:CJN.03060319. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03060319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirsch S Prerenal Success in Chronic Kidney Disease. Am J Med. 2007;120(9):754–759. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.02.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bucaloiu ID, Kirchner HL, Norfolk ER, Hartle JE, Perkins RM. Increased risk of death and de novo chronic kidney disease following reversible acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2012;81(5):477–485. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ali T, Khan I, Simpson W, et al. Incidence and Outcomes in Acute Kidney Injury: A Comprehensive Population-Based Study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18(4):1292–1298. doi: 10.1681/asn.2006070756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoste EAJ, Bagshaw SM, Bellomo R, et al. Epidemiology of acute kidney injury in critically ill patients: the multinational AKI-EPI study. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41(8):1411–1423. doi: 10.1007/s00134-015-3934-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chawla LS. Disentanglement of the acute kidney injury syndrome. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2012;18(6):579–584. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e328358e59c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ricci Z, Cruz D, Ronco C. The RIFLE criteria and mortality in acute kidney injury: A systematic review. Kidney Int. 2008;73(5):538–546. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nickolas TL, Schmidt-Ott KM, Canetta P, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic stratification in the emergency department using urinary biomarkers of nephron damage: A multicenter prospective cohort study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59(3):246–255. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.10.854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palevsky PM, Molitoris BA, Okusa MD, et al. Design of clinical trials in acute kidney injury: Report from an NIDDK workshop on trial methodology. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7(5):844–850. doi: 10.2215/CJN.12791211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Self WH, Semler MW, Wanderer JP, et al. Balanced Crystalloids versus Saline in Noncritically Ill Adults. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(9):819–828. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1711586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Semler MW, Self WH, Wanderer JP, et al. Balanced Crystalloids versus Saline in Critically Ill Adults. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(9):829–839. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1711584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shawwa K, Kompotiatis P, Jentzer JC, et al. Hypotension within one-hour from starting CRRT is associated with in-hospital mortality. J Crit Care. 2019;54:7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2019.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meersch M, Küllmar M, Schmidt C, et al. Long-Term Clinical Outcomes after Early Initiation of RRT in Critically Ill Patients with AKI. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;29(3):1011–1019. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2017060694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Woodward CW, Lambert J, Ortiz-Soriano V, et al. Fluid Overload Associates With Major Adverse Kidney Events in Critically Ill Patients With Acute Kidney Injury Requiring Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy. Crit Care Med. June 2019:1. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kellum JA, Prowle JR. Paradigms of acute kidney injury in the intensive care setting. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2018;14(4):217–230. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2017.184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Delanaye P, Cavalier E, Pottel H. Serum Creatinine: Not so Simple! Nephron. 2017;136(4):302–308. doi: 10.1159/000469669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clark AL, Kalra PR, Petrie MC, Mark PB, Tomlinson LA, Tomson CRV. Change in renal function associated with drug treatment in heart failure: National guidance. Heart. 2019;105(12):904–910. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2018-314158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]