Graphical abstract

Keywords: Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), Coronavirus, nsP13, Myricetin, Scutellarein

Abstract

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) was the first pandemic in the 21st century to claim more than 700 lives worldwide. However, effective anti-SARS vaccines or medications are currently unavailable despite being desperately needed to adequately prepare for a possible SARS outbreak. SARS is caused by a novel coronavirus, and one of its components, a viral helicase, is emerging as a promising target for the development of chemical SARS inhibitors. In the following review, we describe the characterization, family classification, and kinetic movement mechanisms of the SARS coronavirus (SCV) helicase—nsP13. We also discuss the recent progress in the identification of novel chemical inhibitors of nsP13 in the context of our recent discovery of the strong inhibition of the SARS helicase by natural flavonoids, myricetin and scutellarein. These compounds will serve as important resources for the future development of anti-SARS medications.

1. A novel coronavirus as a culprit for severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) is an atypical contagious respiratory illness primarily transmitted by respiratory droplets or close personal contact [1]. It emerged at the end of 2002 from Guangdong province in Southern China and rapidly spread to Canada and to Southeast Asian countries, including Singapore, Vietnam, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. The affected patients initially showed mild flu-like symptoms, such as cough, sore throat, and fever, and the incubation period for this disease was usually about 2–7 days. The symptoms progressed to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in about 25% of the affected patients, which necessitated mechanical ventilation for survival. More than 50% of the patients who developed ARDS eventually died. The global SARS pandemic was brought under control in July of 2003 by undertaking public health measures, including isolation of patients. A total of 8096 patients were diagnosed with SARS, of which 774 died (total mortality rate, 9.6%). Another important clinical feature of SARS is that compared to elderly patients, young patients had a favorable prognosis (mortality rates for elderly patients: up to 50%) [2]. The total number of SARS patients and casualties worldwide are available on the official website of the World Health Organization (WHO): http://www.who.int/csr/sars/country/en.

During the SARS outbreak, clinicians were unaware of which treatments were required to treat SARS patients, because they had no prior experience in dealing with this disease. After the SARS outbreak, the WHO immediately organized international collaborative efforts to conduct clinical, epidemiological, and laboratory investigations to control the spread of SARS. It was soon identified that the causative agent of SARS was a novel coronavirus, referred to as the SARS coronavirus (SCV) [3], [4], and that the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) was a putative receptor for SCV [5]. SCV has been isolated not only from humans but also from diverse animal species such as civet cats, raccoon dogs, swine, and bats. Therefore, SCV is transmissible between different species, and these animals can function as potential reservoirs of SCV for future outbreaks.

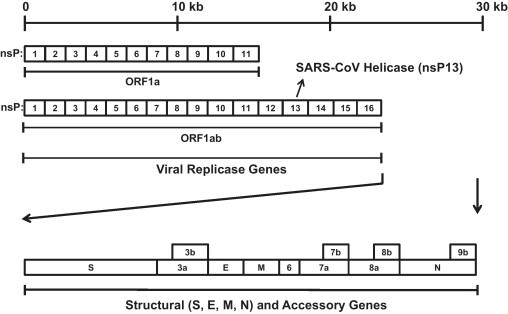

Coronaviruses are members of a family of enveloped viruses that replicate in the cytoplasm of the host animal cells. Coronaviruses are a diverse group of large, enveloped, positive-stranded RNA viruses that cause respiratory and enteric diseases in humans and other animals. Analysis of the full sequence of SCV, which is about 29.7 kb in length, reveals that it is a large, single-stranded, positive-sense RNA virus (Fig. 1 ). The first 2/3 of the SCV genome consists of the viral replicase genes that encode 16 non-structural proteins. Two large polyproteins (pp1ab [∼790 kDa] and pp1a [∼490 kDa]) are initially generated from the replicase region (orf1ab and orf1a) and subsequently cleaved into individual polypeptides by 2 virus-encoded proteinases, the papain-like (accessory) cysteine proteinase (also referred to as PLpro) and 3C-like (main) proteinase (also referred to as 3CLpro or Mpro). Cleavage of pp1ab and pp1a by viral proteinases results in the generation of a total of 16 non-structural proteins (nsPs). It is interesting to note that the expression of pp1ab involves ribosomal frameshifting into the −1 frame just upstream of the pp1a translation termination codon [6]. Although it is still unclear which nsPs are essential or dispensable for replication of the SCV, the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (nsP12) and the NTPase/helicase (nsP13) are certainly critical components for viral replication, and as such, they can serve as feasible targets for the development of SCV inhibitors. The remaining part of the SCV genome, comprising the last 1/3 part encodes 4 structural proteins, namely, spike (S), membrane (M), envelope (E), and nucleocapsid (N) together with 8 accessory proteins that possess no significant sequence homology to viral proteins or other coronaviruses. The functions of these accessory proteins in cells are still poorly characterized [7].

Fig. 1.

The organization of the SCV genome. Replicase genes comprise the first 2/3 of the genome and are translated into 2 polyproteins (Orf1ab [pp1ab] and Orf1a [pp1a]) from open reading frames (ORF1ab and ORF1a). These polyproteins are further cleaved into individual non-structural proteins (nsPs) by viral proteases (nsP3, also called PLpro and nsP5, also called 3CLpro or Mpro). As a result, 16 non-structural proteins (from nsP1 to nsP16) are produced. It is noted that the SCV helicase is the protein nsP13, a cleavage product of pp1ab with 2 3CLpro cleavage sites at both ends. The remaining 1/3 of the genome encodes 4 structural proteins, spike (S), envelope (E), membrane (M), and nucleocapsid (N), together with 8 accessory proteins. 3a and 3b are predicted to originate from the same subgenomic mRNA, and a similar analogy can be applied to other accessory proteins (7a and 7b; 8a and 8b; N and 9b).

2. Characterization of the SCV helicase protein

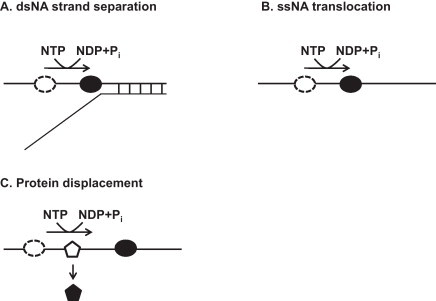

Helicases are molecular motor proteins that separate double-stranded (ds) nucleic acid (NA) using the free energy generated from nucleoside triphosphate (NTP) hydrolysis during translocation on single-stranded (ss) NA [8], [9], [10] (Fig. 2 ). The presence of helicase was first recognized in Escherichia coli in 1976 [11]. Subsequent studies have revealed that helicases are ubiquitous proteins in both eukaryotes and prokaryotes that are required for a wide range of biological processes, such as genome replication [12], recombination, displacement of proteins bound to NAs [13], [14], and chromatin remodeling [15]. Defects in helicase activity are closely associated with a number of human diseases, including premature aging and cancers [16], [17], [18]. Helicases can be grouped into distinct classes, depending on (1) the polarity of their NA unwinding (5′-to-3′ or 3′-to-5′), (2) the types of NA substrate (DNA or RNA helicase), or (3) the basis of primary structure (superfamilies [SFs] and families) [10], [19], [20], [21].

Fig. 2.

Multiple activities of helicases. (A) dsNA strand separation using the energy from NTP hydrolysis. (B) ssNA translocation using the energy from NTP hydrolysis. (C) Protein displacement by helicase during the ssNA translocation.

As mentioned earlier, SCV is a coronavirus family member and was ultimately identified as the virus responsible for SARS [3], [4]. The SCV is an irregularly shaped particle with an outer envelope bearing distinctive club-shaped peplomers. The diameter of an SCV is about 100 nm and the SCV helicase belongs to the SF1, based on a prediction of conserved amino acid sequences. Although a three-dimensional structure of the SCV helicase is still unavailable, its tertiary structure has been predicted by computational modeling studies [22], [23]. The nsP13 SCV helicase consists of 601 amino acids and is a cleavage product of pp1ab [6], [24]. Analysis of amino acid sequence suggests that the SCV helicase has 2 separate domains: (1) a metal-binding domain (MBD) at the N-terminus and (2) a helicase domain (Hel) [22]. A detailed understanding of the biochemical mechanism mediated by SCV helicase became possible [25], [26], [27], [28], [29] after its purification [6], [30].

3. Unwinding of double-stranded nucleic acids (dsNAs) mediated by SCV helicase

The majority of helicases clearly prefer only 1 type of NA (i.e., either RNA or DNA) as an unwinding substrate [31], [32]. Since SCV is a positive-strand ssRNA virus [3], [4], the SCV helicase is regarded as a RNA helicase. However, the SCV helicase and other nidovirus helicases such as the arteritis virus helicase can unwind both dsDNA and dsRNA [33], a feature that is analogous to the hepatitis C virus (HCV) NS3 helicase belonging to the SF2 [34]. Because SF1 and SF2 helicases are closely related in terms of conserved amino acids sequence motifs as well as biochemical properties [9], [19], [20], experimental strategy of the NS3 helicase is are very useful for elucidating the function of the SCV helicase. It is also advantageous to be able to measure dsDNA unwinding activity by SCV helicase in order to identify effective inhibitors of NA unwinding, because DNA is much easier to handle than RNA. In fact, Tanner et al. probed the unwinding activity of His-tagged SCV helicase by using radiolabeled fully dsDNA and partially dsDNA substrates with both 5′- and 3′-ssDNA overhangs [30]. Neither the fully dsDNA nor the partially dsDNA with a 3′-ssDNA overhang were unwound by SCV helicase. For SCV helicase-mediated unwinding of dsNA, a 5′-overhang ssNA was required to load the helicase, which means that the SCV helicase unwinds duplex NAs with a 5′- to 3′-directionality (polarity) [33], [30]. Similar results describing NA unwinding were also reported by Ivanov et al. by using a maltose binding protein (MBP)-tagged SCV helicase [33]. They showed that the MBP-tagged SCV helicase unwound only partial duplex RNA containing a 5′-ssRNA overhang, whereas partial duplex RNA containing a 3′-ssRNA overhang was not unwound. Unwinding experiments with partial duplex DNA also demonstrated that a 5′-ssDNA overhang is necessary for efficient separation by MBP-tagged SCV helicase, indicating a 5′- to 3′-polarity of dsNA unwinding.

Detailed observations of NA unwinding by the SCV helicase were made using a variety of dsDNA substrates by Lee et al. [28]. They conducted unwinding experiments using dsDNA substrates that had different lengths of duplex and 5′-ssDNA overhangs under single-turnover reaction conditions. In the single-turnover experimental setup, an excess ssDNA trap was included in the reaction quenching solution instead of the initial reaction mixture, which prevents re-initiation of dsDNA unwinding by binding to free helicases that are unbound to a dsDNA substrate, as well as helicases that have dissociated from the DNA substrates during the unwinding reaction. The excess DNA trap also inhibits the displaced ssDNA generated during the helicase unwinding reaction from re-annealing to its counterpart ssDNA [35]. By adopting a single-turnover reaction condition, the kinetic time-course of dsDNA unwinding was measured, which provided the kinetic parameters for unwinding. To demonstrate the ssNA translocation or dsNA separation by helicases, a few kinetic parameters are required such as stepping rate, processivity, and step size. Of the kinetic parameters, the processivity of the SCV helicase was investigated with dsDNA substrates containing duplex regions of different lengths [28]. Processivity is defined as a measure of the number of base pairs unwound or the number of nucleotides translocated per enzyme-binding event before the helicase dissociates from the DNA [8], [19]. It is also calculated empirically, and is equal to the rate constant of DNA unwinding divided by the sum of the dissociation and unwinding rate constants [9], [35]. The all-or-none unwinding assay helps monitor the time-dependent strand displacement by the helicase, on the basis of which reaction amplitudes of dsDNA are measured, thus providing a measure of the processivity. The dsDNA unwinding by the SCV helicase showed that the amount of DNA unwound decreased as the length of the duplex region increased [28]. This is consistent with the results of other related helicases. In fact, many helicases have been characterized by the same all-or-none unwinding assay, which showed that the reaction amplitudes decreased as the duplex length increased due to the helicases falling off during the unwinding [35], [36], [37]. Although accurate measurements of the SCV helicase dsNA unwinding processivity are not available because of a lack of a kinetic step size under the experimental conditions, it is reported to be much lower than that associated with other related SF2 family members, such as the NPH-II and HCV NS3 helicases [34], [38]. Recently, a GST-tagged SCV helicase expressed in a baculovirus system showed a higher dsDNA unwinding activity than that of MBP-tagged and His-tagged helicases expressed in E. coli [39]. In addition, the catalytic efficiency of the GST-helicase was enhanced by a SCV polymerase (nsP12). However, it remains unclear precisely why the GST-helicase from the baculovirus system is more active than other tagged helicases expressed in E. coli.

The exact mechanism of strand separation by the SCV helicase remains unclear at present; however, the enzyme activities might be attributed to the monomeric form of the enzyme, like those of the majority of the other SF1 helicases. It has been reported that some SF1 and SF2 helicases can unwind NAs in their monomeric form, but their processivities are generally low [37], [40], [41]. It is also noted that the monomeric forms of some SF1 helicases are rapid and processive at translocating along ssNA, but not processive at dsNA unwinding [42], [43], [44]. In fact, some SF1 helicases (for example, E. coli Rep, E. coli UvrD, and Bacillus stearothermophilus PcrA) display enhanced helicase activity through self-assembly or interaction with other accessory proteins, such as polymerase or single-stranded binding proteins [42], [45], [46], [47]. In the case of the ring-shaped hexameric T7 bacteriophage helicase, pre-steady state kinetic analysis showed that the T7 helicase by itself shows a low processivity at dsDNA unwinding [35]. However, dsDNA unwinding helicase activity increased by almost 9-fold, which is similar to the speed at translocating along ssDNA in the presence of accessory proteins such as polymerase and thioredoxin [48], indicating that the T7 helicase recovers its intrinsic moving speed. Pre-steady state kinetic analysis of helicases demonstrates that helicases intrinsically translocate unidirectionally along ssNAs at a much faster rate than that of dsNA unwinding, because overcoming the energetic barrier for dsNA separation is not necessary [43], [49]. Considering that the SCV has a polymerase and other nonstructural proteins with unknown functions, it is reasonable that the full activity of dsNA unwinding by the SCV helicase may require accessory proteins.

In addition to dsDNA substrates containing different lengths of duplex regions, studies on dsDNA unwinding by the SCV helicase were also conducted using partial dsDNA substrates containing a 50-bp duplex region with different lengths of 5′-ssDNA overhang to investigate the dependence of unwinding on the length of the loading strand [28]. Time-dependent unwinding by the SCV helicase showed that the amount of unwound dsDNA increased as the length of 5′-ssDNA overhang increased. For example, an overhang length of 40 bases resulted in unwinding of more than 95% of the dsDNA substrate, while about 20% of the dsDNA substrate was unwound with a 20 bases 5′-overhang. In case of a 5′-overhang shorter than 20 bases, the amount of unwound dsDNA was not significant. These results suggest that NA binding and unwinding by the SCV helicase has the following functional properties: (1) multiple helicases can bind to a 5′-overhang as the length of the overhang increases, thereby exhibiting a higher processivity; (2) DNA unwinding increases because the binding affinity of helicase monomer or oligomer to 5′-overhang becomes tighter, and (3) functional SCV helicase translocation along ssNA and dsNA unwinding requires a 20-base-long ssNA loading strand, implying a minimal binding site size of the SCV helicase.

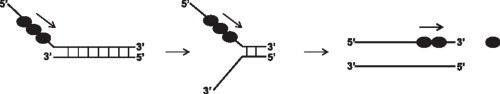

To further examine the dependence of exposed ssNA length on dsNA unwinding by the SCV helicase, a series of dsDNA substrates containing a different length of gap without a 5′-overhang was designed and dsDNA unwinding was measured. The designed gapped dsDNA substrates had blunt ends, and the only binding region for the SCV helicase was the exposed ssDNA gap. Measurements of the gapped dsDNA unwinding showed that a minimal length ssDNA gap was necessary for unwinding, and the amount of unwound dsDNA increased as the length of the gap increased. These findings indicate that the longer loading strand facilitates more binding of the helicase molecule and enhances dsDNA unwinding processivity. The gapped dsDNA unwinding was also measured in the presence of a 5′-ssDNA overhang. The time-course of unwinding with elaborately designed gapped dsDNA with a 5′-overhang indicated that the SCV helicase recognizes the exposed ssDNA portion, both the 5′-ssDNA overhang and the gap, in a different manner. The 5′-ssDNA overhang turned out to be more important for binding and unwinding of the dsDNA substrates. It was also observed that a defined length of the gap in the blunt-ended dsDNA, which was able to unwind dsDNA up to a certain duplex length, was not sufficient to unwind longer duplex DNA. However, the presence of a 5′-ssDNA overhang enabled the SCV helicase to unwind the longer duplex DNA completely, even when the dsDNA substrate with an insufficient gap length for longer duplex DNA unwinding was used. The finding that a longer ssDNA at the 5′ side is necessary to unwind a longer duplex DNA is consistent with the results obtained using dsDNA with different lengths of 5′-ssDNA overhang. Taken together, it is very likely that the SCV helicases pile up during the translocation and facilitate the unwinding by helping the preceding helicase molecule. Therefore, the SCV helicase can translocate along the ssNA and enhance the duplex unwinding unless the helicase falls off. This means that multiple monomers, which are bound to ssNA, unwind the duplex DNA substrate more efficiently, as shown in the proposed model (Fig. 3 ). The proposed model is reminiscent of the mechanism for the unwinding of the T4 Dda (SF1) and HCV NS3 (SF2) helicases [37], [50]. Similar to the SCV helicase, the Dda and NS3 helicases showed increased unwinding activities as the length of the ss-overhang increased in the presence of excess enzyme, supporting the idea for multiple helicase molecules during unwinding. Regarding the structural interactions between helicase monomers, current models suggest that protein–protein interactions are not required for enhanced processivity of monomeric helicases. Rather, the increase in the helicase activity is explained by functional cooperativity between helicase monomers [28]. The model presented in Fig. 3 shows how a non-processive helicase, such as the SCV helicase, acquires high processivity for NA unwinding. Although the model does not contain any other accessory proteins from either the host or the virus itself, the SCV helicase may also be aided by the accessory proteins expressed in infected cells. Future studies will be necessary to mimic the actual replication complex present in the SCV life cycle.

Fig. 3.

Proposed model of dsNA unwinding by SCV helicase. (A) Multiple SCV helicases bound to a 5′-overhang unwind dsNA substrate more efficiently, which is explained by functional cooperativity. (B) Unwinding of gapped dsNA substrate by the SCV helicase is expedited by multiple trailing helicases.

4. NTP hydrolysis activity of the SCV helicase

Helicases convert NTP to NDP and inorganic phosphate (Pi) during ssNA translocation and dsNA separation. During NTP binding and hydrolysis, helicase undergoes stepwise NTP ligation states, including NTP, NDP + Pi, NDP, and empty [51], [52], [53]. Changes in the NTP ligation state lead to conformational changes in the helicase and subsequently cause changes in NA binding affinity. Therefore, translocation and unwinding are driven by NTP binding and hydrolysis. The NTP binding site of SF1/SF2 helicases is generally located at the interface between 2 separated core domains. As the NTP ligation state changes, by which the three-dimensional conformation of the NTP binding pocket also alters, it eventually results in the movement of the domains [54], [55], [56]. This causes a change in the NA binding affinity, thereby bringing about a “power stroke” for translocation. A representative translocation mechanism of PcrA with respect to ATP binding and hydrolysis was proposed as a model system for SF1 helicases [20], the family to which SCV helicase belongs.

A basic characterization of NTPase activity of the SCV helicase has been performed after purification of the protein from E. coli [30], [33]. Although most helicases (including the SCV helicase) make use of ATP as a preferred energy source, exceptions include the T7 helicase that prefers dTTP for DNA unwinding [57], [58], and the T4 gp41 uses GTP as well as ATP for helicase activity. For nucleotides tested for use by the SCV helicase, all 8 common NTPs and dNTPs were hydrolyzed, although the SCV helicase showed better preference for ATP and dATP [30], [33]. Similarly, other helicases that are found in RNA viruses have been shown to have little selectivity for specific types of nucleotides as cofactors [59], [60], [61], suggesting a general feature of RNA virus helicases. The fact that the SCV helicase can hydrolyze a variety of NTPs and dNTPs implies that the triphosphate moiety is the more basic factor for recognition by the helicase rather than sugar/base moieties. The lack of selectivity for specific nucleotides may enable the SCV helicase to bind to triphosphorylated 5′-ends of RNA and have RNA 5′-triphosphatase activity in viral 5′-capping like other related RNA viruses [62], [63], [64]. Although an exact crystal structure is not available as of yet, it is highly likely that the SCV helicase binds to nucleotides and RNA substrate through interactions to β- and γ-phosphate groups. In addition, the SCV helicase is dependent on divalent cations, specifically Mg2+, to hydrolyze nucleotide substrates [65]. It has been reported that NTPase activity of helicases is stimulated in the presence of divalent cations, so the ATPase activity stimulation of SCV helicase was investigated in the presence of 4 different divalent metal cations, Mg2+, Mn2+, Ca2+, and Zn2+ [66]. To date, no helicase has exhibited significant ATPase activity without divalent cations. Of the cations tested, Mg2+ showed optimal stimulation of ATPase activity, and stimulation by Mn2+ was about 40% of Mg2+. However, both Ca2+ and Zn2+ showed less than 20% of the activity of Mg2+. Computer-based modeling analysis showed that the Lys288 residue in the SCV helicase motif I (Walker A) comes into contact with β-phosphate of the bound MgNTP and stabilizes its transition state during catalysis [23]. In addition to motif I, Asp374 of motif II (Walker B) coordinates the Mg2+ of MgNTP, and Glu375 acts as a catalytic base in NTP hydrolysis. Interestingly, an energetically favored position of ATP in the NTPase catalytic pocket of SCV helicase closely resembles the crystal structure of PcrA, a very well-known helicase in the SF1, suggesting that the ATPase activity of the SCV helicase shows a similar pattern to that shown by the ATPase activity of other SF1 helicases [23]. In fact, Mg2+ binding stabilizes the MgNTP complex in the binding pocket of PcrA, thereby hydrolyzing ATP [67].

The presence of NAs also plays an important role in the NTPase activity of helicases. Most helicases, including the SCV helicase, exhibit little or no intrinsic ATPase activity in the absence of NAs. However, the NAs greatly stimulate NTP hydrolysis and the increase in NTPase activity ranges from 10- to 100-fold depending on the type of NAs [68], [69], [70]. The ATPase activity of the SCV helicase was also reported to be stimulated in the presence of homopolynucleotides, in particular poly(U) RNA [30], [66]. Steady state ATPase rates increased in a hyperbolic manner as the concentrations of poly(U) increased, providing a k cat of 68.0 s−1 and a K m of 11.7 nM [66]. However, the ATPase activity was not significantly increased by the addition of either poly(G) or poly(dG). Stimulation of ATPase activity was also investigated in the presence of DNA [66]. When M13 ssDNA, a 7250 base-long circular ssDNA, was added in the ATP hydrolysis reaction, the steady state ATPase rate increased to about 70-times of that observed in the absence of NA, and the k cat value was similar to that of poly(U). However, the presence of plasmid dsDNA did not stimulate the ATPase activity of the SCV helicase, providing a very similar ATPase rate to that observed in the absence of NA. The fact that the ATPase activity is stimulated by only ssNA, and not dsNA, indicates that the SCV helicase binds only ssNA. In fact, the SCV helicase does not unwind blunt-ended dsDNA substrate [30] as mentioned above. Generally, most helicases show enhanced NTPase activity in the presence of ssNA, leading to the interpretation that a conformational change in the protein occurs, thereby hydrolyzing the bound NTP [65].

5. Development of chemical inhibitors of the SCV helicase, nsP13

At present, neither curative SARS remedies nor vaccines are available, and the number of research studies directed toward SARS treatment options in human is still small. Therefore, it is likely that serious global health issues will occur if this disease reemerges in the future. Due to a sudden emergence and explosive spread of SARS, a number of broad-spectrum antiviral medications were empirically administered to the SARS patients during the SARS outbreak in 2003. These medications include ribavirin, HIV protease inhibitors, corticosteroids, and alpha-interferon (IFN-α). In a retrospective review of treatment effects, however, it was demonstrated that none of them actually benefited the SARS patients, and some of them (for example, ribavirin and corticosteroids) may have actually harmed the patients [71]. Thus far, a number of anti-SARS agents have been identified and are reported as promising anti-SCV agents. However, the molecular mechanisms by which they suppress virus growth are largely unclear, and discrepant results have sometimes been reported [72], claiming an urgency for target-based discovery of anti-SARS inhibitors. As mentioned earlier, we have proposed that the SCV helicase (nsP13) protein is a critical component, required for virus replication in host cells, and thus may serve as a feasible target for anti-SARS chemical therapies.

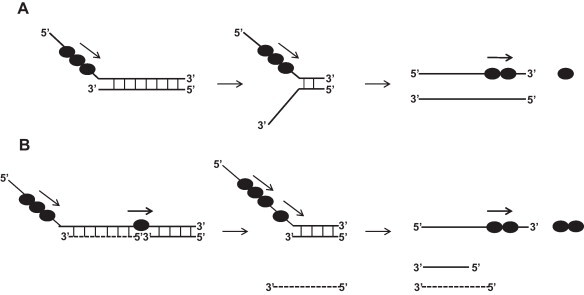

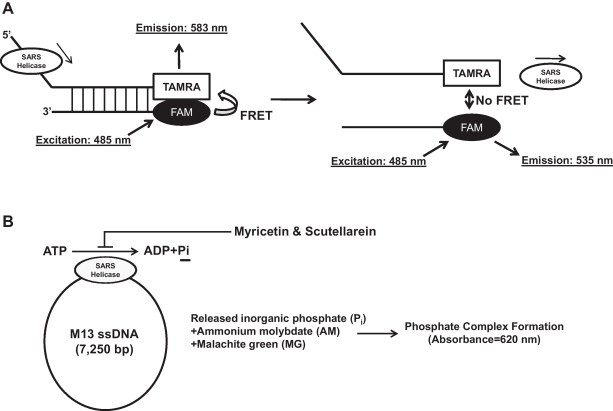

We have recently conducted in vitro biochemical experiments to find out which natural compounds might suppress either (1) the DNA unwinding activity or (2) the ATPase activity of the SCV helicase, nsP13 [73]. Due to proven pharmacological effects of many natural phytochemicals, originating from our dietary or medicinal plants in human, we have selected natural compounds as potential sources for anti-SCV inhibitors. First, we applied the principle of fluorescent resonance energy transfer (FRET) to find out the natural compounds that inhibit the DNA unwinding activity of nsP13. FRET describes an energy transfer mechanism in which the energy of a donor molecule is transferred to an acceptor molecule. More specifically, we mixed nsP13 protein with fluorescent-labeled dsDNA, each strand of which was labeled with different fluorescent dyes, i.e., fluorescein (FAM) and carboxytetramethylrhodamine (TAMRA) at the same terminus. Therefore, a constant FRET reaction between fluorescein and TAMRA occurred when the 2 DNA strands were base-paired; however, this interaction is lost as soon as the duplex is unwound by the nsP13 helicase (Fig. 4A). Using this experimental approach, we observed that none of our natural chemicals (64 compounds in total) interfered with the DNA unwinding activity of the nsP13 protein. Next, we examined the possible effects of natural compounds on suppression of ATP hydrolysis by nsP13. The ATP hydrolysis activity of nsP13 was measured using M13 ssDNA as a template. M13 ssDNA is long circular DNA; therefore, the viral helicase nsP13 protein is expected to continuously translocate along the ssDNA, unless the helicase separates from the DNA. The degree of ATP hydrolysis was then examined by measuring the release of inorganic phosphate (Pi) by colorimetric analysis (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, we observed that only 2 chemicals (myricetin and scutellarein) out of the 64 natural compounds strongly inhibited the ATPase activity of nsP13. IC50 values of myricetin and scutellarein were determined to be 2.71 ± 0.19 μM and 0.86 ± 0.48 μM, respectively; however, they failed to affect the ATPase activity of the HCV NS3 helicase in an identical experimental setup, demonstrating a structural selectivity of these compounds against the ATPase function of SCV helicase [73].

Fig. 4.

(A) Schematic representation of FRET-based dsDNA unwinding assay. Natural chemical inhibitors of SCV helicase (nsP13) dsDNA unwinding activity were assayed by measuring the FRET changes between fluorescein (FAM) and carboxytetramethylrhodamine (TAMRA). (B) Schematic representation of the measurement of the ATPase activity of nsP13. The degree of ATP hydrolysis is determined by measuring the complex formation of inorganic phosphate (Pi) with ammonium molybdate (AM) and malachite green (MG). Both myricetin and scutellarein were found to inhibit the ATPase activity of nsP13, although they did not suppress the ATPase activity of the human hepatitis C virus helicase (NS3h) in an identical experimental setup (data not shown).

It is interesting to note that both myricetin and scutellarein are natural flavonoid compounds. Flavonoids are secondary plant metabolites and have been shown to exert significant beneficial effects such as anti-inflammatory, anti-neurodegenerative, anti-viral, and anti-tumorigenic activities in vitro and in vivo [74]. How myricetin and scutellarein suppress ATPase activity but not the DNA unwinding activity of nsP13 is unclear. In addition, several types of specific chemical inhibitors of SCV have been identified by other groups. For example, bananins, which are adamantane derivatives in which vitamin B6 (pyridoxal) is directly conjugated, strongly inhibited the activity of SCV helicase in vitro and replication of SCV in cultured cells [29]. Exposure of bismuth compounds, which are clinically used as medications for treatment of a variety of gastrointestinal disorders [75], also exerted strong inhibitory effects on the DNA unwinding activity as well as the ATPase activity of SCV helicase, resulting in a retarded growth of SCV-infected cells [76], [77]. Further, Lee et al. recently identified some aryl diketoacids (ADKs) as chemical inhibitors of SCV helicase. However, in contrast to myricetin and scutellarein, they appeared to inhibit the duplex DNA-unwinding activity but not the ATPase activity of SCV helicase [26]. They have expanded the study by showing that dihydroxychromone derivatives, which are structural analogs of ADKs, can function as chemical inhibitors of the DNA-unwinding activity, but not of the ATPase activity, of SCV helicase [27]. Together, these SCV helicase inhibitors can serve as good candidates for development of SARS medication(s) in the future.

6. Future perspectives

As mentioned above, we have recently identified myricetin and scutellarein as novel chemical inhibitors of SCV helicase. In addition, other investigators have found different types of chemical inhibitors of SCV helicases. However, identification of selective chemical inhibitors of SCV in vivo is a daunting task because there are still no appropriate mouse models to test the efficacy of potential anti-SARS inhibitors [78]. In addition, we are yet to determine the molecular mechanisms by which this virus infects, replicates, and evades host cells. Because (1) antiviral interferons (IFNs) are produced during viral infection and modulate adaptive immune responses to promote viral clearance in cells and because (2) SARS is associated with aberrant IFN production and the induction of INF-stimulated genes (ISGs), we propose that SARS is an innate-immunity-regulated disease [79]. This view is well supported by a recent study of SCV infection in primates. SCV infection of cynomolgus macaques resembled several pathological aspects of SARS patients, including an increase in body temperature and acute lung injury, and more interestingly, they exhibited a differential expression of genes that are closely related to inflammation and host immune responses [80]. It is well known that innate immune response signaling plays an important role in alerting host cells to the presence of invading viruses. Pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), such as RIG-I-like receptors (RLRs) and toll-like receptors (TLRs), recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) from invading viral components or pre-existing replication intermediates and elicit appropriate intracellular signaling cascades to protect the host against viruses. Therefore, a better understanding of how innate immune receptors (RLRs and TLRs) as well as intracellular host antiviral immune systems respond to SCV infection will provide us with additional molecular targets for the development of anti-SCV chemical inhibitors in the future.

Acknowledgments

Y.-J. Jeong was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (2010-0022332) and a grant of the Korea Healthcare Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant no.: A103001). Y.-S. Keum was supported by the GRRC program of Gyeonggi province [(GRRC-DONGGUK2011-A01), Study of control of viral diseases].

References

- 1.Berger A., Drosten C., Doerr H.W., Sturmer M., Preiser W. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) – paradigm of an emerging viral infection. J Clin Virol. 2004;29:13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peiris J.S., Yuen K.Y., Osterhaus A.D., Stohr K. The severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2431–2441. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra032498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marra M.A., Jones S.J., Astell C.R., Holt R.A., Brooks-Wilson A., Butterfield Y.S., et al. The Genome sequence of the SARS-associated coronavirus. Science. 2003;300:1399–1404. doi: 10.1126/science.1085953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rota P.A., Oberste M.S., Monroe S.S., Nix W.A., Campagnoli R., Icenogle J.P., et al. Characterization of a novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Science. 2003;300:1394–1399. doi: 10.1126/science.1085952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS): over 100 days into the outbreak. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2003;78:217–20. [PubMed]

- 6.Thiel V., Ivanov K.A., Putics A., Hertzig T., Schelle B., Bayer S., et al. Mechanisms and enzymes involved in SARS coronavirus genome expression. J Gen Virol. 2003;84:2305–2315. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19424-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.SARS Investigation Team from DMERI; SGH Strategies adopted and lessons learnt during the severe acute respiratory syndrome crisis in Singapore. Rev Med Virol. 2005;15:57–70. doi: 10.1002/rmv.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lohman T.M., Bjornson K.P. Mechanisms of helicase-catalyzed DNA unwinding. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 1996;65:169–214. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.001125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel S.S., Donmez I. Mechanisms of helicases. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:18265–18268. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R600008200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patel S.S., Picha K.M. Structure and function of hexameric helicases. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:651–697. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.651. 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abdel-Monem M., Hoffmann-Berling H. Enzymic unwinding of DNA. 1. Purification and characterization of a DNA-dependent ATPase from Escherichia coli. Eur J Biochem. 1976;65:431–440. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1976.tb10358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kornberg A. DNA replication. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1988;951:235–239. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(88)90091-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Veaute X., Delmas S., Selva M., Jeusset J., Le Cam E., Matic I., et al. UvrD helicase, unlike Rep helicase, dismantles RecA nucleoprotein filaments in Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 2005;24:180–189. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jankowsky E., Gross C.H., Shuman S., Pyle A.M. Active disruption of an RNA-protein interaction by a DExH/D RNA helicase. Science. 2001;291:121–125. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5501.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saha A., Wittmeyer J., Cairns B.R. Chromatin remodelling: the industrial revolution of DNA around histones. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:437–447. doi: 10.1038/nrm1945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ellis N.A. DNA helicases in inherited human disorders. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1997;7:354–363. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(97)80149-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ellis N.A., Groden J., Ye T.Z., Straughen J., Lennon D.J., Ciocci S., et al. The Bloom's syndrome gene product is homologous to RecQ helicases. Cell. 1995;83:655–666. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90105-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu C.E., Oshima J., Fu Y.H., Wijsman E.M., Hisama F., Alisch R., et al. Positional cloning of the Werner's syndrome gene. Science. 1996;272:258–262. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5259.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lohman T.M., Tomko E.J., Wu C.G. Non-hexameric DNA helicases and translocases: mechanisms and regulation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:391–401. doi: 10.1038/nrm2394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singleton M.R., Dillingham M.S., Wigley D.B. Structure and mechanism of helicases and nucleic acid translocases. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:23–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.052305.115300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gorbalenya A.E., Koonin E.V. Helicases: amino acidsequence comparisons and structure–function relationships. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1993;3:419–429. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bernini A., Spiga O., Venditti V., Prischi F., Bracci L., Huang J., et al. Tertiary structure prediction of SARS coronavirus helicase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;343:1101–1104. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.03.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoffmann M., Eitner K., von Grotthuss M., Rychlewski L., Banachowicz E., Grabarkiewicz T., et al. Three dimensional model of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus helicase ATPase catalytic domain and molecular design of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus helicase inhibitors. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 2006;20:305–319. doi: 10.1007/s10822-006-9057-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Snijder E.J., Bredenbeek P.J., Dobbe J.C., Thiel V., Ziebuhr J., Poon L.L., et al. Unique and conserved features of genome and proteome of SARS-coronavirus, an early split-off from the coronavirus group 2 lineage. J Mol Biol. 2003;331:991–1004. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(03)00865-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jang K.J., Lee N.R., Yeo W.S., Jeong Y.J., Kim D.E. Isolation of inhibitory RNA aptamers against severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus NTPase/Helicase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;366:738–744. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee C., Lee J.M., Lee N.R., Jin B.S., Jang K.J., Kim D.E., et al. Aryl diketoacids (ADK) selectively inhibit duplex DNA-unwinding activity of SARS coronavirus NTPase/helicase. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2009;19:1636–1638. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee C., Lee J.M., Lee N.R., Kim D.E., Jeong Y.J., Chong Y. Investigation of the pharmacophore space of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) NTPase/helicase by dihydroxychromone derivatives. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2009;19:4538–4541. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee N.R., Kwon H.M., Park K., Oh S., Jeong Y.J., Kim D.E. Cooperative translocation enhances the unwinding of duplex DNA by SARS coronavirus helicase nsP13. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:7626–7636. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tanner J.A., Zheng B.J., Zhou J., Watt R.M., Jiang J.Q., Wong K.L., et al. The adamantane-derived bananins are potent inhibitors of the helicase activities and replication of SARS coronavirus. Chem Biol. 2005;12:303–311. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tanner J.A., Watt R.M., Chai Y.B., Lu L.Y., Lin M.C., Peiris J.S., et al. The severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus NTPase/helicase belongs to a distinct class of 5′ to 3′ viral helicases. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:39578–39582. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300328200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee C.G., Hurwitz J. A new RNA helicase isolated from HeLa cells that catalytically translocates in the 3′ to 5′ direction. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:4398–4407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rogers G.W., Jr., Richter N.J., Merrick W.C. Biochemical and kinetic characterization of the RNA helicase activity of eukaryotic initiation factor 4A. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:12236–12244. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.18.12236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ivanov K.A., Thiel V., Dobbe J.C., van der Meer Y., Snijder E.J., Ziebuhr J. Multiple enzymatic activities associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus helicase. J Virol. 2004;78:5619–5632. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.11.5619-5632.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pang P.S., Jankowsky E., Planet P.J., Pyle A.M. The hepatitis C viral NS3 protein is a processive DNA helicase with cofactor enhanced RNA unwinding. EMBO J. 2002;21:1168–1176. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.5.1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jeong Y.J., Levin M.K., Patel S.S. The DNA-unwinding mechanism of the ring helicase of bacteriophage T7. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:7264–7269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400372101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ali J.A., Lohman T.M. Kinetic measurement of the step size of DNA unwinding by Escherichia coli UvrD helicase. Science. 1997;275:377–380. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5298.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Levin M.K., Wang Y.H., Patel S.S. The functional interaction of the hepatitis C virus helicase molecules is responsible for unwinding processivity. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:26005–26012. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403257200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jankowsky E., Gross C.H., Shuman S., Pyle A.M. The DExH protein NPH-II is a processive and directional motor for unwinding RNA. Nature. 2000;403:447–451. doi: 10.1038/35000239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Adedeji A.O., Marchand B., Te Velthuis A.J., Snijder E.J., Weiss S., Eoff R.L., et al. Mechanism of nucleic acid unwinding by SARS-CoV helicase. PLoS One. 2012;7:e36521. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nanduri B., Byrd A.K., Eoff R.L., Tackett A.J., Raney K.D. Pre-steady-state DNA unwinding by bacteriophage T4 Dda helicase reveals a monomeric molecular motor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:14722–14727. doi: 10.1073/pnas.232401899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu H.Q., Deprez E., Zhang A.H., Tauc P., Ladjimi M.M., Brochon J.C., et al. The Escherichia coli RecQ helicase functions as a monomer. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:34925–34933. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303581200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cheng W., Hsieh J., Brendza K.M., Lohman T.M. E. coli Rep oligomers are required to initiate DNA unwinding in vitro. J Mol Biol. 2001;310:327–350. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fischer C.J., Maluf N.K., Lohman T.M. Mechanism of ATP-dependent translocation of E. coli UvrD monomers along single-stranded DNA. J Mol Biol. 2004;344:1287–1309. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Niedziela-Majka A., Chesnik M.A., Tomko E.J., Lohman T.M. Bacillus stearothermophilus PcrA monomer is a single-stranded DNA translocase but not a processive helicase in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:27076–27085. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704399200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ali J.A., Maluf N.K., Lohman T.M. An oligomeric form of E. coli UvrD is required for optimal helicase activity. J Mol Biol. 1999;293:815–834. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maluf N.K., Fischer C.J., Lohman T.M. A dimer of Escherichia coli UvrD is the active form of the helicase in vitro. J Mol Biol. 2003;325:913–935. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01277-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang Y., Dou S.X., Ren H., Wang P.Y., Zhang X.D., Qian M., et al. Evidence for a functional dimeric form of the PcrA helicase in DNA unwinding. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:1976–1989. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stano N.M., Jeong Y.J., Donmez I., Tummalapalli P., Levin M.K., Patel S.S. DNA synthesis provides the driving force to accelerate DNA unwinding by a helicase. Nature. 2005;435:370–373. doi: 10.1038/nature03615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim D.E., Narayan M., Patel S.S. T7 DNA helicase: a molecular motor that processively and unidirectionally translocates along single-stranded DNA. J Mol Biol. 2002;321:807–819. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00733-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Byrd A.K., Raney K.D. Increasing the length of the single-stranded overhang enhances unwinding of duplex DNA by bacteriophage T4 Dda helicase. Biochemistry. 2005;44:12990–12997. doi: 10.1021/bi050703z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Singleton M.R., Sawaya M.R., Ellenberger T., Wigley D.B. Crystal structure of T7 gene 4 ring helicase indicates a mechanism for sequential hydrolysis of nucleotides. Cell. 2000;101:589–600. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80871-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Abrahams J.P., Leslie A.G., Lutter R., Walker J.E. Structure at 2.8 A resolution of F1-ATPase from bovine heart mitochondria. Nature. 1994;370:621–628. doi: 10.1038/370621a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hingorani M.M., Washington M.T., Moore K.C., Patel S.S. The dTTPase mechanism of T7 DNA helicase resembles the binding change mechanism of the F1-ATPase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5012–5017. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dillingham M.S., Wigley D.B., Webb M.R. Demonstration of unidirectional single-stranded DNA translocation by PcrA helicase: measurement of step size and translocation speed. Biochemistry. 2000;39:205–212. doi: 10.1021/bi992105o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Soultanas P., Dillingham M.S., Wiley P., Webb M.R., Wigley D.B. Uncoupling DNA translocation and helicase activity in PcrA: direct evidence for an active mechanism. EMBO J. 2000;19:3799–3810. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.14.3799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Velankar S.S., Soultanas P., Dillingham M.S., Subramanya H.S., Wigley D.B. Crystal structures of complexes of PcrA DNA helicase with a DNA substrate indicate an inchworm mechanism. Cell. 1999;97:75–84. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80716-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hingorani M.M., Patel S.S. Interactions of bacteriophage T7 DNA primase/helicase protein with single-stranded and double-stranded DNAs. Biochemistry. 1993;32:12478–12487. doi: 10.1021/bi00097a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jeong Y.J., Kim D.E., Patel S.S. Kinetic pathway of dTTP hydrolysis by hexameric T7 helicase-primase in the absence of DNA. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:43778–43784. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208634200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bautista E.M., Faaberg K.S., Mickelson D., McGruder E.D. Functional properties of the predicted helicase of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Virology. 2002;298:258–270. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Morgenstern K.A., Landro J.A., Hsiao K., Lin C., Gu Y., Su M.S.S., et al. Polynucleotide modulation of the protease, nucleoside triphosphatase, and helicase activities of a hepatitis C virus NS3-NS4A complex isolated from transfected COS cells. J Virol. 1997;71:3767–3775. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.5.3767-3775.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Preugschat F., Averett D.R., Clarke B.E., Porter D.J.T. A steady-state and pre-steady-state kinetic analysis of the NTPase activity associated with the hepatitis C virus NS3 helicase domain. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:24449–24457. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.40.24449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bisaillon M., Bergeron J., Lemay G. Characterization of the nucleoside triphosphate phosphohydrolase and helicase activities of the reovirus lambda1 protein. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:18298–18303. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.29.18298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bisaillon M., Lemay G. Characterization of the reovirus lambda1 protein RNA 5′-triphosphatase activity. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:29954–29957. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.47.29954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li Y.I., Shih T.W., Hsu Y.H., Han Y.T., Huang Y.L., Meng M. The helicase-like domain of plant potexvirus replicase participates in formation of RNA 5′ cap structure by exhibiting RNA 5′-triphosphatase activity. J Virol. 2001;75:12114–12120. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.24.12114-12120.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kadare G., Haenni A.L. Virus-encoded RNA helicases. J Virol. 1997;71:2583–2590. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.4.2583-2590.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lee N.R., Lee A.R., Lee B., Kim D-E., Jeong Y-J. ATP hydrolysis analysis of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus helicase. Korean Chem Soc. 2009;30(8):1724–1728. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Soultanas P., Dillingham M.S., Velankar S.S., Wigley D.B. DNA binding mediates conformational changes and metal ion coordination in the active site of PcrA helicase. J Mol Biol. 1999;290:137–148. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Arai K., Kornberg A. Mechanism of dnaB protein action. II. ATP hydrolysis by dnaB protein dependent on single- or double-stranded DNA. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:5253–5259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Patel S.S., Rosenberg A.H., Studier F.W., Johnson K.A. Large scale purification and biochemical characterization of T7 primase/helicase proteins. evidence for homodimer and heterodimer formation. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:15013–15021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Washington M.T., Rosenberg A.H., Griffin K., Studier F.W., Patel S.S. Biochemical analysis of mutant T7 primase/helicase proteins defective in DNA binding, nucleotide hydrolysis, and the coupling of hydrolysis with DNA unwinding. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:26825–26834. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.43.26825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Stockman L.J., Bellamy R., Garner P. SARS: systematic review of treatment effects. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e343. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cinatl J., Jr., Michaelis M., Hoever G., Preiser W., Doerr H.W. Development of antiviral therapy for severe acute respiratory syndrome. Antiviral Res. 2005;66:81–97. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yu M.S., Lee J., Lee J.M., Kim Y., Chin Y.W., Jee J.G., et al. Identification of myricetin and scutellarein as novel chemical inhibitors of the SARS coronavirus helicase, nsP13. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2012;22:4049–4054. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.04.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Williams R.J., Spencer J.P., Rice-Evans C. Flavonoids: antioxidants or signalling molecules. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;36:838–849. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hassfjell S., Brechbiel M.W. The development of the alpha-particle emitting radionuclides 212Bi and 213Bi, and their decay chain related radionuclides, for therapeutic applications. Chem Rev. 2001;101:2019–2036. doi: 10.1021/cr000118y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yang N., Tanner J.A., Zheng B.J., Watt R.M., He M.L., Lu L.Y., et al. Bismuth complexes inhibit the SARS coronavirus. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2007;46:6464–6468. doi: 10.1002/anie.200701021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yang N., Tanner J.A., Wang Z., Huang J.D., Zheng B.J., Zhu N., et al. Inhibition of SARS coronavirus helicase by bismuth complexes. Chem Commun (Camb) 2007:4413–4415. doi: 10.1039/b709515e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Totura A.L., Baric R.S. SARS coronavirus pathogenesis: host innate immune responses and viral antagonism of interferon. Curr Opin Virol. 2012;2:264–275. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wong C.K., Lam C.W., Wu A.K., Ip W.K., Lee N.L., Chan I.H., et al. Plasma inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in severe acute respiratory syndrome. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;136:95–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02415.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Smits S.L., de Lang A., van den Brand J.M., Leijten L.M., van I.W.F., Eijkemans M.J., et al. Exacerbated innate host response to SARS-CoV in aged non-human primates. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000756. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]