Abstract

Long RT-PCR (LRP) amplification of RNA templates is sometimes difficult compared to long PCR of DNA templates. Among RNA templates, hepatitis C virus (HCV) represents an excellent example to challenge the potential of LRP technology due to its extensive secondary structures and its difficulty to be readily cultured in vitro. The only source for viral genome amplification is clinical samples in which HCV is usually present at low titers. We have created a comprehensive optimization protocol that allows robust amplification of a 9.1 kb fragment of HCV, followed by efficient cloning into a novel vector. Detailed analyses indicate the lack of potential LRP-mediated recombination and the preservation of viral diversity. Thus, our LRP protocol could be applied for the amplification of other difficult RNA templates and may facilitate RNA virus research such as linked viral mutations and reverse genetics.

Keywords: Hepatitis C, Long RT-PCR, Quasispecies, Cloning

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is an indispensable technique in biomedical research. With known primer sequences, it can easily amplify a DNA target less than 3 kb but it has diminished power when the target is larger than 3 kb. In 1994, Barnes et al. [1] first hypothesized that the inability to amplify large DNA fragments was due to the misincorporation of nucleotides by most thermostable DNA polymerases, which resulted in premature termination of PCR. Based on this hypothesis, mixed polymerases, one of which has 3′–5′ exonuclease “proofreading” activity to correct the misincorporation, have successfully amplified DNA targets up to 42 kb [2]. However, there has been limited success in applying this concept to the amplification of large RNA genomes that require the reverse transcription (RT) step prior to PCR amplification. Compared to the amplification of DNA targets, it is reasonable to hypothesize that the RT step is of crucial importance during long RT-PCR (LRP) performance when taking into account the following characteristics. First, in most situations, the solution buffers are not compatible between RT and PCR. Only part of the RT reaction can be used for subsequent PCR and thus reduces the sensitivity dramatically. Second, most RT enzymes have an inhibitory role for thermostable DNA polymerases [3]. Third, RT is conducted at temperatures ranging from 37 °C to 50 °C at which the RNA template may retain its secondary structure that makes RT stop prematurely. Such situations are even more challenging when trying to amplify full-length hepatitis C virus (HCV) genome, a positive sense single-strand RNA virus in the family of flavirividae. There is extensive secondary structure along the whole HCV genome [4], [5], [6]. Furthermore, HCV cannot be cultured in vitro. The only source of RNA template for LRP is clinical samples in which HCV has a low titer. In the present study, we have investigated each step for the LRP procedure and developed a robust protocol for the efficient amplification and cloning of near full-length HCV genome from clinical samples. We also estimated the sensitivity and potential PCR-mediated recombination related to this protocol.

Materials and methods

Samples. The LRP optimization was directly conducted with serum samples collected in 2001 from two patients infected with HCV genotype 1a, referred to as JLR3037 and RJ, respectively. A large volume of serum stored at −70 °C was available from these two patients, which allowed repeated and detailed optimization of our LRP protocol. After the optimization, additional serum samples were used for the estimation of sensitivity, robustness, and potential recombination (see below). HCV RNA levels were quantitated by bDNA assay (Bayer VERSANT HCV 3.0) immediately prior to the start of this study.

RNA extraction. Total RNA was extracted from serum by using either QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) or TRIzol LS reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the instructions provided. With QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit, RNA was extracted from 280 μl of serum and finally eluted into 60 μl of Tris buffer containing 20 U/ml of RNasein Ribonuclease Inhibitor (Promega, Madison, WI). In the extraction with TRIzol LS reagent, 250 μl of serum was applied and the RNA pellet was finally dissolved in 20 μl of nuclease-free water containing 20 U/ml of RNasein Ribonuclease Inhibitor (Promega). Additionally either glycogen (Invitrogen) or transfer RNA (tRNA) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was used for facilitating RNA precipitation. For both methods, vigorous vortexing was avoided to prevent shearing of long RNA templates [7].

Reverse transcription. Since RT is a critical step for successful LRP, we optimized this step as follows. First, we tested multiple RT enzymes alone or in combination, including AMV (Promega), M-MLV (Promega), Expand Reverse Transcriptase (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN), Transcriptor Reverse Transcriptase (Roche Applied Science), SuperScript II (Invitrogen), SuperScript III (Invitrogen), and rTth DNA polymerase (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) that shows reverse transcriptase activity in the presence of MnCl2 at elevated temperatures. In some experiments, we mixed a RT enzyme with Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene), a similar strategy as used in long PCR, to improve full-length cDNA synthesis [8]. Second, previous studies showed certain chemicals might improve full-length cDNA synthesis in both quantity and quality. In this study, we tried different additives at various concentrations, including DMSO (5–10%) (Sigma), GC-Melt (0.5 M) (BD Biosciences), DTT (5–10 mM), trehalose (0.6 M) (Sigma) [9], and betaine (2 M) (Sigma) [9]. Third, we designed a series of HCV-specific RT primers located at the 3′ end of NS5b (Table 1 ). These primers were tested for efficient priming at different concentrations. Fourth, besides direct application of RT reaction in subsequent PCR, we also tried to purify RT reaction with or without RNase H digestion [11] prior to PCR, by using QIAquick PCR Purification Kit or QIAquick Nucleotide Removal Kit (Qiagen) or Dynabeads KilobaseBINDER Kit (Dynal) in which RT primers were biotinylated at their 5′ ends. Finally, we also investigated the role of 7-deaza-2′-deoxyguanosine (Sigma) in the RT reaction that may improve the elongation in GC-rich domains [10].

Table 1.

The list of primers tested during LRP optimization

| Primer | Polarity | Sequence (5′–3′) | Position | Tm (°C) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RT | QR1 | Anti-sense | Cggttggggaggaggtag | 9356–9373 | 60.5 |

| QR2 | Anti-sense | Tagccagccgtgaaccag | 9248–9265 | 61 | |

| QR268 | Anti-sense | Gctgtagccagccgtgaaccag | 9248–9269 | 68.5 | |

| QR274 | Anti-sense | Ccgctgtagccagccgtgaaccag | 9248–9271 | 74.4 | |

| QR3* | Anti-sense | Cagccctgcctcctctgg | 9139–9156 | 64.5 | |

| QR4 | Anti-sense | Ggttggggaggaggtagatg | 9353–9372 | 60.7 | |

| QR5 | Anti-sense | Tgcagcaagcaggagtagg | 9326–9344 | 60.3 | |

| QR6 | Anti-sense | Atcggttggggaggaggtag | 9356–9375 | 62.5 | |

| QR7* | Anti-sense | Atcagtatcatcctcgcccac | 8858–8878 | 61.3 | |

| Q5BR1 | Anti-sense | Gcagcaagcaggagtaggcaa | 9323–9343 | 65.1 | |

| Q5BR2 | Anti-sense | Tatcggagtgagtttgagct | 9199–9218 | 55.1 | |

| Q5BR3 | Anti-sense | Tttgagctttgttcttactg | 9187–9206 | 50.9 | |

| PCR | QUF1 | Sense | Ggcgacactccaccatagatc | 18–38 | 61.8 |

| QUF2 | Sense | Gccgagtagtgttgggtc | 253–270 | 56.5 | |

| QUF3 | Sense | Ctgtgaggaactactgtcttc | 45–65 | 51.5 | |

| QUF4 | Sense | Ctgcctgatagggtgcttg | 289–307 | 59.4 | |

| QUF5 | Sense | Actcccctgtgaggaactac | 39–58 | 55.7 | |

| WF1 | Sense | Actcccctgtgaggaactactgtcttcac | 39–67 | 67.8 | |

| WF2 | Sense | Actgtcttcacgcagaaagcgtctagc | 57–83 | 68.9 | |

| WF3 | Sense | Agaaagcgtctagccatggcgttag | 70–94 | 67.6 | |

| WF33 | Sense | Acgcagaaagcgtctagccat | 66–86 | 63.5 | |

| WF4 | Sense | Tagtatgagtgtcgtgcagcctcca | 92–116 | 67.2 | |

| WF5** | Sense | ggatctgacgttaattaacatagtggtctgcggaaccggt | 139–160 | 67.5 | |

| WF6 | Sense | Gactgctagccgagtagtgttgggtc | 245–270 | 67.4 | |

| WF7 | Sense | Tggtactgcctgatagggtgcttg | 284–307 | 66.5 | |

| WR1* | Anti-sense | Ctattratttcacctggagagtaactgtggag | 9021–9052 | 67.6 | |

| WR2* | Anti-sense | Ctgaggcatgcggccacc | 9053–9070 | 68.7 | |

| WR3* | Anti-sense | Cggtgtctccaagctcgcaa | 9090–9109 | 67.1 | |

| WR4* | Anti-sense | Agaagyctagcgcggacgctc | 9116–9136 | 65.5 | |

| WR5 | Anti-sense | Gcagccctgcctcctctgg | 9139–9157 | 68.0 | |

| WTR5 | Anti-sense | Gcagccctacctcctctgg | 9139–9157 | 62.3 | |

| WR55** | Anti-sense | atagctgggtggccggccatggcagccctacctcctctgg | 9139–9160 | 67.9 | |

| WR6 | Anti-sense | Ttggagtgagtttgagctttgttcttactg | 9187–9216 | 66.7 | |

| WR7 | Anti-sense | Gccgctattggagtgagtttgagc | 9200–9223 | 67.3 | |

| HCV6 | Anti-sense | Ggtaccccaagtttrctgaggca | 9063–9085 | 63.5 | |

| HCV7 | Anti-sense | Gagtaactgtggagtgaaaaygcg | 9011–9034 | 62.2 | |

| 5′UTR | QUF3 | Sense | Ctgtgaggaactactgtcttc | 45–65 | 257 bp |

| QUR3 | Anti-sense | Ccctatcaggcagtaccacaa | 281–301 | ||

| Core | CoreF2 | Sense | Tactgcctgatagggtgcttg | 287–307 | 709 bp |

| CoreR3 | Anti-sense | Atcggccgyctcgtacacaat | 975–995 | ||

| E1/E2 | QRAF2 | Sense | Aactgttcaccttctctccca | 1207–1227 | 496 bp |

| Q6AR1 | Anti-sense | Tcgggacagcctgaagagttg | 1682–1702 | ||

| NS3 | NS3AF2 | Sense | Tgtggagaacctagagacaac | 3933–3953 | 316 bp |

| NS3AR2 | Anti-sense | Cgtcggcaaggaacttgccrt | 4228–4248 | ||

| NS5a | Q5AF2 | Sense | Atccctcccatataacagcag | 6871–6891 | 251 bp |

| Q5AR2 | Anti-sense | Acaagcggatcgaaggagtcca | 7099–7121 | ||

| NS5b | Q5BF2 | Sense | Atccgtacggaggaggcaat | 8298–8317 | 921 bp |

| Q5BR2 | Anti-sense | Tatcggagtgagtttgagct | 9199–9218 |

We also show the Tm values for all LRP primers as well as the primer sequences used for monitoring HCV cDNA synthesis. Star indicates that primer sequences are involved within putative stem loops [4], [5], [6]. Double stars indicate that primers contain restriction sites in their 5′ ends. Primer numbering is according to HCV H77 strain (GenBank Accession No. NC_004102). All primers were designed with software Eugene version 1.01. Degenerate bases are matched with standard International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) codes.

PCR. All PCR experiments were done with DNA Thermal Cycler 480 (Perkin-Elmer-Cetus, Norwalk, CT). The nested PCR strategy and a touchdown protocol were generally applied. At the beginning, we tested several thermostable DNA polymerases for long PCR, such as Expand Long Template PCR System (Roche Applied Science) and Elongase Enzyme Mix (Invitrogen). We eventually focused on rTth DNA polymerase, XL (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), and most of the optimization experiments were done with this enzyme. The strategy to optimize long PCR was basically similar to what we described for RT step. Multiple additives were first tested, including DMSO, betaine [12], [13], and tetramethylammonium (TMA) oxalate [14]. Next, a series of primers were tested for their efficiency with long PCR (Table 1). Meantime, since one of the mixed polymerases has 3′–5′ exonuclease “proofreading” activity that may degrade primers, we tested phosphorothioate primers to see if the PCR amplification is improved [15], [16], [17]. To allow hot-start PCR that may diminish non-specific priming, we adopted two measures, the use of loop incorporated primers [18] and an oligonucleotide, Trnc-21, which specially inhibits DNA polymerase isolated from Thermus thermophilus (Tth pol) at low temperature [19], [20]. Finally, with the DNA Thermal Cycler 480, we empirically fixed denaturing temperature at 94 °C for 30 s, elongation temperature at 72 °C or 68 °C for 9 min, and annealing step for 30 s. However, the annealing temperature was adjusted depending on the T m values of the primers (Table 1).

Molecular cloning of HCV envelope domain. HCV displays a typical quasispecies nature shared by most RNA viruses. To understand if our LRP protocol conserves viral diversity, we compared the HCV quasispecies profiles derived from regular RT-PCR and LRP products in two patient samples, LIV19 and LIV23. The viral heterogeneity has been detailed in these two patients in our previous study based on a 1.38 kb amplicon spanning the most hypervariable region 1 (HVR1) of HCV genome [21]. In brief, serum RNA was reverse transcribed with 200 U M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Promega), followed by nested PCR with Taq DNA polymerase (Applied Biosystems). The PCR product was gel purified by using QIAEX II Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen) and ligated into the pTOPO-TA cloning vector (Invitrogen). Escherichia coli TOP-10 cells (Invitrogen) were used for transformation and recovery of recombinant clones. Approximately 15 clones for each sample were sequenced with ABI PRISM dye terminator cycle sequencing ready reaction kit using an ABI 373A automated sequencer (Applied Biosystems).

Molecular cloning of long RT-PCR product. For cloning the LRP product, we first tried several commercial cloning kits, including TOPO XL PCR Cloning Kit (Invitrogen), Copylight Cloning Kit, and Clone Smart Blunt Cloning Kit (Lucigen Corporation, Middleton, WI), without success. Next, we estimated cloning efficiency of Gateway Technology with Clonase II (Invitrogen). Finally, we returned to a conventional cloning strategy in which the LRP product was digested with two restriction enzymes PacI and FseI, followed by ligation into a special plasmid named pClone. The ligation product was electroporated into Stbl4 cells or DH10B cells (Invitrogen). The pClone vector was constructed by replacing PacI–BamHI fragment of pAdTrack-CMV [22] with a ∼120 bp fragment that was assembled to include rare restriction enzymes not found in the HCV genome based on an analysis of 13 full-length HCV genotype 1a isolates. Positive recombinant clones were identified by either the digestion or partial sequencing of both ends of the insert.

Estimation of PCR-mediated recombination. PCR may induce a homologous recombination [23], [24], [25]. The rate of recombination is dependent on the protocol used. After the optimization of our long RT-PCR, we estimated the potential recombination related to this protocol. In doing so, sera from samples LIV19 and LIV23 were mixed in equal amounts, followed by the same procedures of RNA extraction, RT, long PCR, and cloning. Approximately 20 positive recombinant clones were sequenced at 8 domains located within 5′UTR, Core, E1, E2, NS2, NS3, NS5a, and NS5b regions, respectively. Recombination would be indicated for a given clone if conflicting clusterings were noted in phylogenetic trees constructed with 1 of the 8 domains that we sequenced.

Genetic analysis. All sequences were aligned with Clustal W (version 1.74) [26]. Sequence editing and multiple sequence comparisons were performed with matched programs in the Wisconsin GCG package (Oxford Molecular Group, Inc., version 10.0). The mean genetic distance (d), the number of synonymous substitutions per synonymous site (dS), and the number of nonsynonymous substitutions per nonsynonymous site (dN) were calculated with the Kimura 2-parameter method (all sites) [27] in the Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis software package (MEGA, version 3.0) [28]. All phylogenetic trees were constructed using the Neighbor-Joining method [29] with a bootstrap test implanted in MEGA. The genetic complexity at both nucleotide and amino acid levels was evaluated, respectively, for samples LIV19 and LIV23 by calculating normalized entropy (S n): S n = S/lnN, where N is the total number of clones; S = −∑i(pi ln pi), where pi is the frequency of each clone in the viral quasispecies population.

Statistical tests. Student’s t-test was used to analyze differences between mean values for genetic parameters when data were normally distributed. Non-parametric tests were used to evaluate samples for which normal distributions were not present.

Results

Monitoring HCV cDNA synthesis

The synthesis of full-length HCV cDNA is a prerequisite for successful LRP. Several groups have performed nested PCR of HCV 5′UTR after RT step, assuming a positive result as the indicator of full-length HCV cDNA synthesis. However, we found that multiple domains, located within 5′UTR, Core, E2, NS3, NS5a, and NS5b, respectively, could be successfully amplified after RT in which RT primers were omitted. This indicated the existence of extensive self-priming during RT presumably induced by HCV RNA secondary structure or oligonucleotides in extracted RNA template. Using the DNA Thermal Cycler 480, the whole procedure for LRP takes at least 2 days. We therefore amplified multiple small fragments (5′UTR, HVR1, NS3, NS5a, and NS5b) (Table 1) by using the first round LRP product as the template. After the first round LRP, the effect of self-priming is reduced. The negative amplification of these small fragments indicated the absolute absence of full-length HCV cDNA and thus the second round LRP is not necessary. To test all LRP conditions and parameters alone or in combination, the optimization procedure consists of hundreds of protocols. Our approach that monitors the full-length cDNA synthesis based on first round PCR product, although not perfect, still improves experimental progress significantly.

Reverse transcription

Two RNA extraction procedures, based on either QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen) or TRIzol LS reagent (Invitrogen), gave similar LRP results. However, in the latter procedure, the addition of tRNA or glycogen during RNA precipitation, even at low concentration, resulted in the failure of subsequent PCR, suggesting that these carriers had a detrimental role on rTth XL activity.

The optimization of RT can be summarized as follows.

-

1.

SuperScript III outperformed all other reverse transcriptases such as AMV, M-MLV, Expand Reverse Transcriptase, Transcriptor Reverse Transcriptase, SuperScript II, and rTth DNA polymerase. Robust LRP results were obtained when running RT with 200 U of SuperScript III at 50 °C for 75 min, followed by inactivation at 70 °C for 15 min. However, using a mixture of SuperScript III (200 U) and AMV (2.5 U) gave LRP results that were much more reproducible, with an increased yield. LRP was not successful using a mixture of RT enzyme and Pfu DNA polymerase, perhaps because the latter had low activity (<30%) in a non-optimized buffer system under RT temperature (50 °C) (Stratagene, personal communication).

-

2.

All additives (except DTT) that we tested in the RT reaction had an adverse role for LRP. Although these additives have been reported to improve full-length cDNA synthesis, they may be not compatible with SuperScript III or rTth XL DNA polymerase.

-

3.

The selection of RT primers is critical for successful LRP. The most satisfactory and reproducible results were obtained only when using QR2 as the RT primer (Table 1). Interestingly, LRP did not work when replacing QR2 with QR264 or QR274, suggesting an appropriate T m value of RT primers was required. However, LRP failed when modifying other RT primers into a similar T m value as QR2. In contrast, reproducible amplifications were obtained with other serum samples in which QR2 had one or two nucleotide substitutions. These observations suggest that efficient priming for full-length HCV cDNA synthesis is domain-dependent. Additionally, unlike previous reports [30], our LRP is acceptable with QR2 in broad range of concentrations from 0.0625 μM to 1 μM.

-

4.

There was no obvious advantage but a reduced sensitivity when purifying RT reaction by using Qiagen spin columns or Dynabeads. Similarly, the use of 7-deaza-2′-deoxyguanosine in RT reaction or RNase H digestion was not advantageous.

PCR

The PCR was most successful with rTth DNA polymerase, XL. However, it should be noted that we did not perform detailed optimization with the another two systems, Expand Long Template PCR System and Elongase Enzyme Mix. The former system is the only one that uses a buffer containing MgCl2, which is a common component of RT buffers. This makes it potentially promising to reconcile the two buffer systems, but information about additional buffer components is not available and therefore optimization cannot be performed. There was no improvement and sometimes even an adverse effect of other measures including the addition of additives (DMSO, betaine, and TMA oxalate) and the use of phosphorothioate or loop incorporated primers. However, Trnc-21, an oligonucleoide inhibitor to rTth DNA polymerase, was required for reproducible amplification. The minimum concentration of Trnc-21 is 0.4 μM. We also found no interference to LRP when increasing the concentration up to 1.2 μM. Unlike RT, the requirement for primers in long PCR is less stringent as long as the T m values of primers are approximately 68 °C.

Optimized LRP protocol

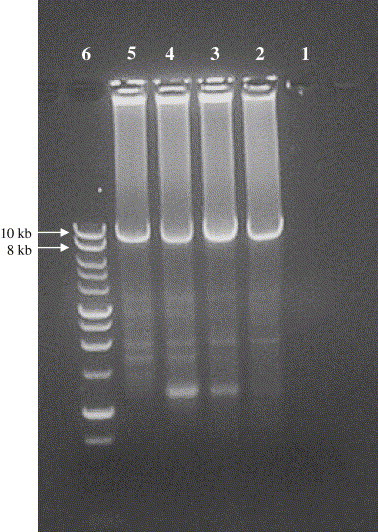

In the optimized protocol, RNA was extracted from 280 μl of serum by using QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen). 10.6 μl of RNA template was mixed with 9.4 μl RT matrix consisting of 1× SuperScript III buffer, 10 mM DTT, 1 μM QR2 (reverse primer), 2 mM dNTPs (Invitrogen), 20 U of RNasein Ribonuclease Inhibitor, 200 U of SuperScript III, and 5 U AMV (Promega). The reaction was performed by incubation at 50 °C for 75 min, followed by heating at 70 °C for 15 min. Five microliters of RT reaction was applied for the first round of PCR that contained 1.25 mM Mg(OAc)2, 1× XL PCR buffer, 2 mM dNTPs (Invitrogen), 0.4 μM Trnc-21, 0.4 μM of each primer (WF33 and QR2), and 2 U rTth XL DNA polymerase. Cycle parameters were programmed as 94 °C for 1 min followed by the first 10 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s and 65 °C for 9 min and final 20 cycles in which the annealing/elongation temperature was reduced to 60 °C for 9 min with a 3 s autoextension at each cycle. The reaction was ended with 10-min incubation at 72 °C. Two microliters of the first round of PCR product was used for the second round amplification with primers WF5 and WR55. Cycle parameters were the same as the first round PCR except the annealing/elongation temperature was changed to 72 °C for the first 10 cycles and 68 °C for the last 20 cycles, respectively. Using this protocol, a 9095 bp fragment was reproducibly obtained for samples JLR3037 and RJ (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Amplification of 9.1 kb fragment of HCV genome from serum samples JLR3037 (lanes 2 and 3) and RJ (lanes 4 and 5) by using optimized LRP protocol. The PCR product was electrophoresed on a 0.8% Seakem GTG agarose gel (FMC BioProducts). Lane 1, negative control; lane 6, 1 kb DNA ladder (Fisher).

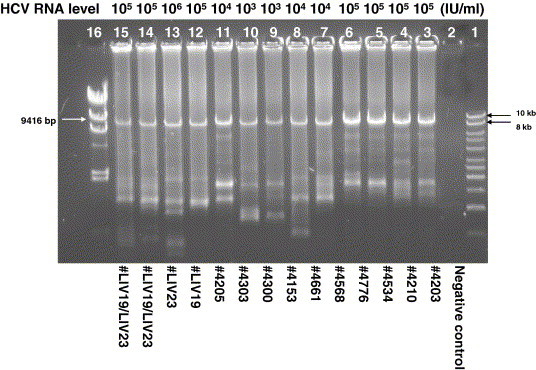

Robustness and sensitivity

With the optimized LRP protocol, we tested 24 HCV genotype 1a samples (serum or plasma) with various RNA levels, ranging from 103 to 106 IU/ml. The predicted DNA fragment of 9.1 kb was successfully amplified in all samples, even in those with low HCV RNA levels. A representative result is shown in Fig. 2 . These results indicate that our LRP protocol is robust and sensitive. For those samples with HCV RNA levels less than 103 IU/ml, LRP amplification was improved by extracting total RNA from 560 μl of serum instead of 280 μl of serum (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Amplification of 9.1 kb fragment of HCV genome from additional serum samples with various HCV RNA levels, including samples LIV19 and LIV23. The PCR product was electrophoresed on a 0.8% Seakem GTG agarose gel (FMC BioProducts). Lane 2, negative control; 1ane 1, 1 kb DNA ladder (Fisher); lane 16, Lambda DNA/HindIII markers (Promega).

In our optimized LRP protocol, we used four primers: QR2, WF33, WF5, and WR55. Sequence alignment showed that these primer domains are relatively conservative through most of HCV genotype 1a isolates, especially for 5′ end primers WF33 and WF5. We also found that one or two nucleotide substitutions within primers QR2 and WR55 did not abrogate the LRP amplification but resulted in a diminished amount of the amplicon as determined by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Cloning the LRP product

We encountered unexpected difficulty in cloning the LRP product that is approximately 9.1 kb in length. We repeatedly tried four commercial cloning kits: TOPO XL PCR Cloning Kit, CopyRight Cloning Kit, Clone Smart Blunt Cloning Kit, and Gateway Technology with Clonase II. A common problem with these cloning kits was the high background of clones without the insert, which is generally assumed to be as the result of either the toxicity of foreign genes or the instability of recombinant clones. Since pSMART vectors from CopyRight and Clone Smart Blunt Cloning Kits contain multiple terminators that eliminate transcription both into and out of the insert DNA and therefore reduce potential toxicity of the insert, the instability of recombinant clones may be responsible for the high background with false positive clones. We therefore constructed pClone vector that contains pBR origin and restriction sites not found in HCV genome. With this conventional strategy, the LRP product was successfully cloned with DH10B E. coli cells but not Stbl4 cells. Positive rate for recombinant clones was about 30% which is much higher than previous reports [31], [32]. A 2 ml miniculture yielded approximately 5 μg of recombinant clones, which is a suitable amount for the performance of analysis such as sequencing.

LRP preserves HCV quasispecies diversity

To see if our LRP protocol preserves viral diversity, we evaluated HCV quasispecies based on HVR1 domain derived either from a short amplicon (1.38 kb) or from the LRP product. We sequenced the HVR1 domain from 16 and 15 positive recombinant clones for samples LIV19 and LIV23, respectively. There are generally comparable levels for both genetic complexity and genetic diversity except for a significantly higher genetic complexity at the amino acid level for sample LIV23 (0.829 versus 0.430, p < 0.05) (Table 2 ). Sample LIV19 had a low genetic diversity and similar HVR1 quasispecies lineages were obtained either by short fragment amplification or by LRP (Fig. 3 A). However, when comparing HVR1 quasispecies profiles, respectively, derived from the 1.38 kb and 9.1 kb amplicons in sample LIV23, only one HVR1 lineage was shared by both amplicons (Fig. 3B).

Table 2.

The comparison of genetic parameters of HCV HVR1 quasispecies profiles derived from either 1.38 kb or 9.1 kb amplicons

| Sample | Amplicon | Number of clones | Genetic complexity |

Genetic distance |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleotide | Amino acid | d | dS | dN | |||

| LIV19 | 1.38 kb fragment | 11 | 0.770 | 0.685 | 0.026 | 0.022 | 0.028 |

| 9.1 kb fragment (LRP) | 16 | 0.537* | 0.800* | 0.025* | 0.036* | 0.020* | |

| LIV23 | 1.38 kb fragment | 18 | 0.430 | 0.430 | 0.164 | 0.098 | 0.197 |

| 9.1 kb fragment (LRP) | 15 | 0.620* | 0.829** | 0.113* | 0.144* | 0.101* | |

Star and double star indicate p > 0.05 and p < 0.05, respectively, comparing to corresponding genetic parameters derived from the 1.38 kb amplicon.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of HCV HVR1 (27 aa) quasispecies profiles derived from either 1.38 kb or 9.1 kb amplicons. Dots indicate the identity to the top line of amino acid sequence. While there is no obvious difference for sample LIV19 (A), LIV23 (B) displays much distinct HVR1 quasispecies profiles from two sizes of amplicons, 1.38 kb and 9.1 kb, respectively.

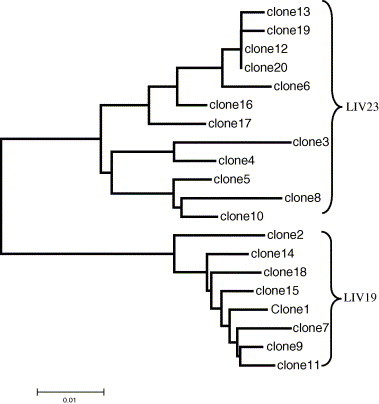

Lack of detection of LRP-mediated recombination

LRP was performed using a mixture of equal amounts of serum from samples LIV19 and LIV23. Twenty clones derived from the LRP product were sequenced at eight domains including 5′UTR, Core, E1, E2, NS2, NS3, NS5a, and NS5b. Phylogenetic analysis showed that eight clones belonged to sample LIV19 and 12 clones were from LIV23. Neighbor-Joining trees constructed with each domain displayed consistent clustering for each clone, suggesting the absence of potential recombination induced by LRP. A representative tree constructed with the HCV E1 domain is shown in Fig. 4 . Although we did not sequence 20 clones in full-length, the possibility for recombination is very small, if not excluded, since the eight domains that we sequenced are evenly scattered along the entire 9.1 kb amplicon.

Fig. 4.

A representative neighbor-joining (NJ) tree constructed based on HCV E1 domain of 20 clones derived from 9.1 kb LRP product, which was amplified using mixed serum from samples LIV19 and LIV23. As expected, all clones are clustered into two groups, LIV19 and LIV23. There is no contradictory clustering for each clone in trees constructed with other seven domains, indicating the lack of LRP-mediated recombination.

Discussion

Long RT-PCR has been successfully used to amplify large or near full-length domains of RNA viruses, including human coronavirus [30], poliovirus [34], borna disease virus [35], porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus [36], coxsackievirus [37], and hepatitis E virus [38]. It has also been applied to the amplification of cellular RNA derived from such genes as the neurofibromatosis 1 (NF1) and polycystic kidney disease 1 (PKD1) genes [39], [40]. In these studies, a common feature was the availability of good RNA templates in both quantity and quality. In contrast, HCV cannot be easily cultured in vitro although there are recent reports of the establishment of HCV cell culture by using a special HCV genotype 2a strain JFH-1 [41], [42], [43]. Clinical samples from patients infected with HCV have a relatively low titer of viral RNA level. In addition, HCV holds a strong structure along with the whole genome [4], [5], [6]. These features may explain the limited success of LRP with HCV. While there have been occasional reports regarding the amplification of near full-length HCV genome [44], [45], reproducible results were only obtained with the amplification of less than 5 kb fragments in HCV [7], [33], [46], [47]. In contrast, the protocol we have described here has considerable robustness. Besides the two serum samples that we used for optimizing our protocols, we successfully amplified a near full-length HCV genome from an additional 24 patient samples infected with HCV genotype 1a. We identified several critical factors for efficient amplification of a near full-length HCV genome. First, the RT step was conducted by using mixed enzymes, SuperScript III and AMV. SuperScript III is a mutant form of SuperScript II, which makes it fully active at temperature as high as 55 °C. Potential RNA secondary structure could be melted at this temperature. However, incubation at 55 °C resulted in decreased sensitivity perhaps due to the partial degradation of the RNA templates. In the optimized protocol, we used 50 °C for the RT reaction. It has been reported that AMV especially favors the reverse transcription of genes with GC-rich domains or strong secondary structure due to its stability at higher temperatures. It is not known how these two enzymes work together, but similar cooperativity has been observed for mixed DNA polymerases in long PCR [1]. In any case, we demonstrated that mixed RT enzymes improve full-length HCV cDNA synthesis in both quality and quantity. Second, not all primers can effectively prime the synthesis of full-length HCV cDNA. In our experiments, only one primer, QR2, met this requirement, indicating the full-length HCV cDNA synthesis is considerably dependent on the appropriate priming site. To some extent, this observation is consistent with a previous report in which differential priming of RNA templates resulted in obvious differences in both accuracy and reproducibility of RT-PCR [48]. Third, the use of Trnc-21 in PCR steps is recommended. Inclusion of Trnc-21 resulted in automated hot-start PCR amplification. Although there are several techniques available for the initiation of “hot-start” PCR, such as manual control, the use of wax, and the addition of antibodies to thermal stable DNA ploymerases, none of them is as efficient and convenient as Trnc-21. Finally, the primers for PCR procedures should have appropriate T m values dependent on the annealing/elongation temperatures. Our last optimization step for successful LRP was to raise the annealing/elongation temperature to 72 °C in the second round of PCR, around 5 °C above the primer T m values. The large difference between annealing/elongation temperatures and primer T m values resulted in non-specific amplification while a low annealing/elongation temperature less than 60 °C always abrogated the amplification.

There are two salient features for our LRP procedure: the lack of detectable recombination and the preservation of viral diversity, as estimated with samples LIV19 and LIV23. Recombination is generally explained by template switching during PCR, particularly when the synthesis of complementary strands is stopped prematurely. The lack of detectable recombination in our LRP protocol may have contributed to the reduced cycle numbers (60 cycles versus regular 70 cycles) and Vent DNA polymerase that is included within rTth DNA polymerase, XL, and has 3′–5′ exonuclease proofreading activity. The HVR1 is located at the 5′ end of HCV E2 domain and is the most variable region along the entire HCV genome. By comparing genetic parameters for HVR1 quasispecies profiles, our LRP protocol preserves viral heterogeneity, as also reported with a 5 kb HCV amplicon [33]. Furthermore, similar HVR1 quasispecies lineages were obtained with sample LIV19 while sample LIV23 displayed much different HVR1 quasispecies lineages derived from either the 1.38 kb or the 9.1 kb amplicon. By using clones as direct PCR templates, we failed to amplify HVR1 domain by screening 40 clones that had no correct insert confirmed with enzyme digestion after miniculture (data not shown). This excludes the possibility for the loss of potential HVR1 quasispecies lineages during the culture due to the instability of recombinant clones. Thus, these results again emphasize the bias of HVR1 quasispecies amplification when using different primer pairs as we previously reported [49]. Still, defective interfering particles (DIP) are another factor to be taken into account. The generation of DIP, natural viral mutants with large deletions in the genome, seems to be a general phenomenon for all viruses, including HCV [50], [51]. Quasispecies profiles contributed by DIP could be lost in our protocol since we gel purified only the 9.1 kb fragment prior to cloning. Taken together, the quantitation of viral diversity, if present at a high level within a given sample, is largely underestimated and/or biased by current protocols for PCR amplification and cloning.

The technology described here should be applicable to other HCV genotypes as well as other RNA viruses such as GB virus C, HIV, and dengue virus. With the amplification and efficient cloning of a near full-length viral genome, it is now possible to study linked mutations at genome-wide scale. Linked mutation is a common strategy exploited by viruses to counter their loss of the fitness resulting from point mutations at immune and/or drug targets. The identification of common patterns of linked mutation is helpful for the improvement of combinational antiviral strategies. In addition, our LRP protocol preserves HCV diversity and has no detectable recombination induced by PCR. These characteristics make it possible to isolate dominant, subdominant, and minor viral variants within a complex virus population, which facilitates the approach of reverse genetics. An initial step in reverse genetics is to construct vectors containing full-length viral genomes, usually assembled by overlapped PCR products that represent viral consensus sequences. However, the consensus sequence is artificial in concept and is not necessarily the dominant viral variant. As a result, replication from infectious clones with consensus viral genome may not occur. This may partially explain why the infectious HCV clone of H77 consensus did not replicate in cell culture while the one with JHF1 did [41], [42], [43]. In contrast to the existence of multiple HVR1 quasispecies lineages in the patient H77 [52], JHF1 was derived from a patient with fulminant hepatitis. The immunocomprised status in this patient resulted in an extremely homogeneous viral population by cloning analysis of HVR1 domain [53]. In such a situation, consensus viral sequence may be equal to authentic dominant viral variant that makes an “infectious” clone infectious.

Acknowledgments

We thank Yunfeng Feng (Washington University in St. Louis) and John E. Tavis (Saint Louis University) for helpful discussions. We also thank Patrick Sheehy (National University of Ireland Cork, Ireland) and Rodolpho M. Albano (Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Brazil) for clarifying issues regarding their work.

References

- 1.Barnes W.M. PCR amplification of up to 35-kb DNA with high fidelity and high yield from lambda bacteriophage templates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:2216–2220. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.6.2216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheng S., Fockler C., Barnes W.M., Higuchi R. Effective amplification of long targets from cloned inserts and human genomic DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:5695–5699. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.12.5695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chumakov K.M. Reverse transcriptase can inhibit PCR and stimulate primer-dimer formation. PCR Meth. Appl. 1994;4:62–64. doi: 10.1101/gr.4.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tuplin A., Wood J., Evans D.J., Patel A.H., Simmonds P. Thermodynamic and phylogenetic prediction of RNA secondary structures in the coding region of hepatitis C virus. RNA. 2002;8:824–841. doi: 10.1017/s1355838202554066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tuplin A., Evans D.J., Simmonds P. Detailed mapping of RNA secondary structures in core and NS5B-encoding region sequences of hepatitis C virus by RNase cleavage and novel bioinformatic prediction methods. J. Gen. Virol. 2004;85:3037–3047. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80141-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simmonds P., Tuplin A., Evans D.J. Detection of genome-scale ordered RNA structure (GORS) in genomes of positive-stranded RNA viruses: implications for virus evolution and host persistence. RNA. 2004;10:1337–1351. doi: 10.1261/rna.7640104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu L., Nakano T., Smallwood G.A., Heffron T.G., Robertson B.H., Hagedorn C.H. A refined long RT-PCR technique to amplify complete viral RNA genome sequences from clinical samples: Application to a novel hepatitis C virus variant of genotype 6. J. Virol. Methods. 2005;126:139–148. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2005.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hawkins P.R., Jin P., Fu G.K. Full-length cDNA synthesis for long-distance RT-PCR of large mRNA transcripts. Biotechniques. 2003;34:768–770. doi: 10.2144/03344st06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spiess A.N., Ivell R. A highly efficient method for long-chain cDNA synthesis using trehalose and betaine. Anal. Biochem. 2002;301:168–174. doi: 10.1006/abio.2001.5474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McConlogue L., Brow M.A., Innis M.A. Structure-independent DNA amplification by PCR using 7-deaza-2′-deoxyguanosine. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:9869. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.20.9869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Polumuri S.K., Ruknudin A., Schulze D.H. RNase H and its effects on PCR. Biotechniques. 2002;32:1224–1225. doi: 10.2144/02326bm01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henke W., Herdel K., Jung K., Schnorr D., Loening S.A. Betaine improves the PCR amplification of GC-rich DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3957–3958. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.19.3957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hengen P.N. Optimizing multiplex and LA-PCR with betaine. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1997;22:225–226. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01069-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kovarova M., Draber P. New specificity and yield enhancer of polymerase chain reactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:E70. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.13.e70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skerra A. Phosphorothioate primers improve the amplification of DNA sequences by DNA polymerases with proofreading activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:3551–3554. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.14.3551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Noronha C.M., Mullins J.I. Amplimers with 3′-terminal phosphorothioate linkages resist degradation by vent polymerase and reduce Taq polymerase mispriming. PCR Meth. Appl. 1992;2:131–136. doi: 10.1101/gr.2.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Di Giusto D., King G.C. Single base extension (SBE) with proofreading polymerases and phosphorothioate primers: improved fidelity in single-substrate assays. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:e7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gng007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ailenberg M., Silverman M. Controlled hot start and improved specificity in carrying out PCR utilizing touch-up and loop incorporated primers (TULIPS) Biotechniques. 2000;29:1018–1020. doi: 10.2144/00295st03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dang C., Jayasena S.D. Oligonucleotide inhibitors of Taq DNA polymerase facilitate detection of low copy number targets by PCR. J. Mol. Biol. 1996;64:268–278. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin Y., Jayasena S.D. Inhibition of multiple thermostable DNA polymerases by a heterodimeric aptamer. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;271:100–111. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chambers T.J., Fan X., Droll D.A., Hembrador E., Slater T., Nickells M.W., Dustin L.B., DiBisceglie A.M. Quasispecies heterogeneity within the E1/E2 region as a pretreatment variable during pegylated interferon therapy of chronic hepatitis C virus infection. J. Virol. 2005;79:3071–3083. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.5.3071-3083.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.He T.C., Zhou S., da Costa L.T., Yu J., Kinzler K.W., Vogelstein B.A. A simplified system for generating recombinant adenoviruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:2509–2514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Judo M.S., Wedel A.B., Wilson C. Stimulation and suppression of PCR-mediated recombination. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:1819–1825. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.7.1819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shafikhani S. Factors affecting PCR-mediated recombination. Environ. Microbiol. 2002;4:482–486. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2002.00326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fang G., Zhu G., Burger H., Keithly J.S., Weiser B. Minimizing DNA recombination during long RT-PCR. J. Virol. Methods. 1998;76:139–148. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(98)00133-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Higgins D.G., Sharp P.M. CLUSTAL: a package for performing multiple sequence alignment on a microcomputer. Gene. 1988;73:237–244. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90330-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kimura M. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J. Mol. Evol. 1980;16:111–120. doi: 10.1007/BF01731581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumar S., Tamura K., Nei M. MEGA3: integrated software for molecular evolutionary genetics analysis and sequence alignment. Brief. Bioinform. 2004;5:150–163. doi: 10.1093/bib/5.2.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saitou N., Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thiel V., Rashtchian A., Herold J., Schuster D.M., Guan N., Siddell S.G. Effective amplification of 20-kb DNA by reverse transcription PCR. Anal. Biochem. 1997;252:62–70. doi: 10.1006/abio.1997.2307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kolykhalov A.A., Agapov E.V., Blight K.J., Mihalik K., Feinstone S.M., Rice C.M. Transmission of hepatitis C by intrahepatic inoculation with transcribed RNA. Science. 1996;277:570–574. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5325.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yanagi M., Purcell R.H., Emerson S.U., Bukh J. Transcripts from a single full-length cDNA clone of hepatitis C virus are infectious when directly transfected into the liver of a chimpanzee. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:8738–8743. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rispeter K., Lu M., Lechner S., Zibert A., Roggendorf M. Cloning and characterization of a complete open reading frame of the hepatitis C virus genome in only two cDNA fragments. J. Gen. Virol. 1997;78:2751–2759. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-11-2751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boot H.J., Schepp R.M., van Nunen F.J., Kimman T.G. Rapid RT-PCR amplification of full-length poliovirus genomes allows rapid discrimination between wild-type and recombinant vaccine-derived polioviruses. J. Virol. Methods. 2004;116:35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2003.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shoya Y., Kobayashi T., Koda T., Lai P.K., Tanaka H., Koyama T., Ikuta K., Kakinuma M., Kishi M. Amplification of a full-length Borna disease virus (BDV) cDNA from total RNA of cells persistently infected with BDV. Microbiol. Immunol. 1997;41:481–486. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1997.tb01881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nielsen H.S., Storgaard T., Oleksiewicz M.B. Analysis of ORF 1 in European porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus by long RT-PCR and restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis. Vet. Microbiol. 2000;76:221–228. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(00)00258-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martino T.A., Tellier R., Petric M., Irwin D.M., Afshar A., Liu P.P. The complete consensus sequence of coxsackievirus B6 and generation of infectious clones by long RT-PCR. Virus Res. 1999;64:77–86. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(99)00081-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jameel S., Zafrullah M., Chawla Y.K., Dilawari J.B. Reevaluation of a North India isolate of hepatitis E virus based on the full-length genomic sequence obtained following long RT-PCR. Virus Res. 2002;86:53–58. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(02)00052-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martinez J.M., Breidenbach H.H., Cawthon R. Long RT-PCR of the entire 8.5-kb NF1 open reading frame and mutation detection on agarose gels. Genome Res. 1996;6:58–66. doi: 10.1101/gr.6.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thongnoppakhun W., Wilairat P., Vareesangthip K., Yenchitsomanus P.T. Long RT-PCR Amplification of the entire coding sequence of the polycystic kidney disease 1 (PKD1) gene. Biotechniques. 1999;26:126–132. doi: 10.2144/99261rr01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhong J., Gastaminza P., Cheng G., Kapadia S., Kato T., Burton D.R., Wieland S.F., Uprichard S.L., Wakita T., Chisari F.V. Robust hepatitis C virus infection in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:9294–9299. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503596102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wakita T., Pietschmann T., Kato T., Date T., Miyamoto M., Zhao Z., Murthy K., Habermann A., Kräusslich H., Mizokami M., Bartenschlager R., Liang T.J. Production of infectious hepatitis C virus in tissue culture from a cloned viral genome. Nature Med. 2005;11:791–796. doi: 10.1038/nm1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lindenbach B.D., Evans M.J., Syder A.J., Wölk B., Tellinghuisen T.L., Liu C.C., Maruyama T., Hynes R.O., Burton D.R., McKeating J.A., Rice C.M. Complete replication of hepatitis C virus in cell culture. Science. 2005;309:623–626. doi: 10.1126/science.1114016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang L.F., Radkowski M., Vargas H., Rakela J., Laskus T. Amplification and fusion of long fragments of hepatitis C virus genome. J. Virol. Methods. 1997;68:217–223. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(97)00132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tellier R., Bukh J., Emerson S.U., Miller R.H., Purcell R.H. Long PCR and its application to hepatitis viruses: amplification of hepatitis A, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C virus genomes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1996;34:3085–3091. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.12.3085-3091.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu Z., Netski D.M., Mao Q., Laeyendecker O., Ticehurst J.R., Wang X.H., Thomas D.L., Ray S.C. Accurate representation of the hepatitis C virus quasispecies in 5.2-kilobase amplicons. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2004;42:4223–4229. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.9.4223-4229.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sheehy P., Scallan M., Kenny-Walsh E., Shanahan F., Fanning L.J. A strategy for obtaining near full-length HCV cDNA clones (assemblicons) by assembly PCR. J. Virol. Methods. 2005;123:115–124. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2004.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang J., Byrne C.D. Differential priming of RNA templates during cDNA synthesis markedly affects both accuracy and reproducibility of quantitative competitive reverse-transcriptase PCR. Biochem. J. 1999;337:231–241. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fan X., Lyra A.C., Tan D., Xu Y., Di Bisceglie A.M. Differential amplification of hypervariable region 1 of hepatitis C virus by partially mismatched primers. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001;284:694–697. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bangham C.R.M., Kirkwood T.B.L. Defective interfering particles and virus evolution. Trends Microbiol. 1993;1:260–264. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(93)90048-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Prince A.M., Huima-Byron T., Parker T.S., Levine D.M. Visualization of hepatitis C virons and putative defective interfering particles isolated from low-density lipoproteins. J. Viral Hepat. 1996;3:11–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.1996.tb00075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Farci P., Shimoda A., Coiana A., Diaz G., Peddis G., Melpolder J.C., Strazzera A., Chien D.Y., Munoz S.J., Balestrieri A., Purcell R.H., Alter H.J. The outcome of acute hepatitis C predicted by the evolution of the viral quasispecies. Science. 2000;288:339–344. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5464.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kato T., Furusaka A., Miyamoto M., Date T., Yasui K., Hiramoto J., Nagayama K., Tanaka T., Wakita T. Sequence analysis of hepatitis C virus isolated from a fulminant hepatitis patient. J. Med. Virol. 2001;64:334–339. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]