Abstract

Fungi from Order Onygenales include human pathogens. Although secondary metabolites are critical for pathogenic interactions, relatively little is known about Onygenales compounds. Here, we use chemical and genetic methods on Aioliomyces pyridodomos, the first representative of a candidate new family within Onygenales. We isolated 14 new bioactive metabolites, nine of which are first disclosed here. Thirty-two specialized metabolite biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) were identified. BGCs were correlated to some of the new compounds by heterologous expression of biosynthetic genes. Some of the compounds were found after one year of fermentation. By comparing BGCs from A. pyridodomos with those from 68 previously sequenced Onygenales fungi, we delineate a large biosynthetic potential. Most of these biosynthetic pathways are specific to Onygenales fungi and have not been found elsewhere. Family-level specificity and conservation of biosynthetic gene content is evident within Onygenales. Identification of these compounds may be important to understanding pathogenic interactions.

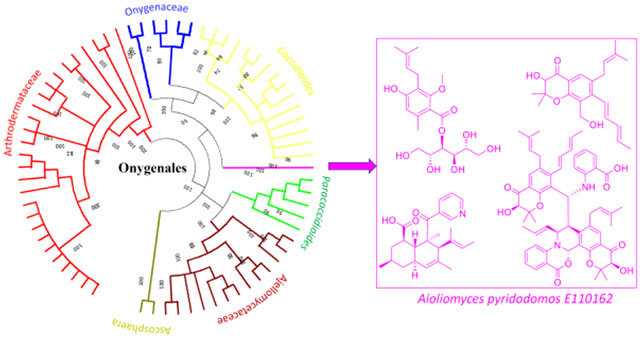

Graphical abstract

Fungi produce secondary metabolites that establish and maintain infections.1 For example, Aspergillus fumigatus (order: Eurotiales) synthesizes gliotoxin as part of its repertoire to circumvent the human immune system.2 Eurotiales fungi, such as Aspergillus spp. and Penicillium spp., are the best-studied producers of secondary metabolites, with thousands of known compounds including those important in virulence. In contrast, fungi from order Onygenales include important human pathogens that are challenging to treat,3, 4 but much less is known about their secondary metabolites. Several Onygenales compounds from pathogens have been produced via heterologous expression,5, 6 but it remains unknown if these are produced in the native host. Similarly, an Onygenales biosynthetic gene cluster (BGC) implicated in virulence is an iron-sequestering siderophore pathway with unknown chemical products.7, 8

From non-pathogenic Onygenales, many compounds have been reported. A few examples include polyketides and isoprenoids from marine9 and terrestrial Onygenales.10–15 Onygenales and Eurotiales strains contain a similar number of BGCs responsible for producing secondary metabolites, although the types of genes differ slightly between the groups.16–19 Thus, it might be expected that both pathogenic and non-pathogenic Onygenales provide a reservoir of new secondary metabolites important in infection.

Here, we examined Aioliomyces pyridodomos, a non-pathogenic Onygenales isolate from a coral reef tunicate in the Eastern Fields of Papua New Guinea. Through genome sequencing, we analyzed BGC content of A. pyridodomos and compared it to the available Onygenales genomes. This analysis revealed a large untapped diversity of Onygenales compounds awaiting discovery from both pathogenic and non-pathogenic isolates. Sequence analysis shows that the number of BGCs in Onygenales is similar to that found in Eurotiales, but encoding a different and new suite of compounds.

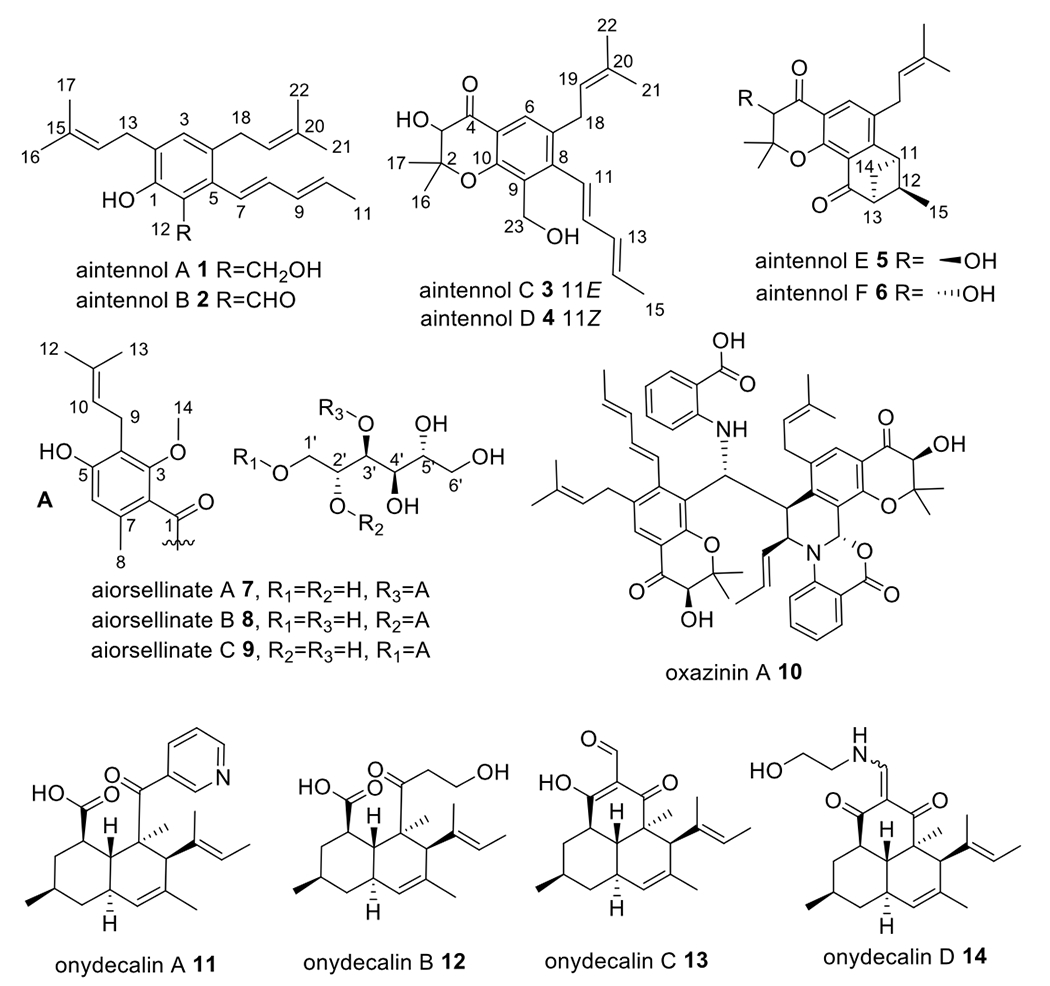

To determine the chemical potential of A. pyridodomos, we performed fermentation and chemical analysis, leading to the discovery of 14 polyketides (1-14). Previously, we identified a new polyketide derivative, oxazinin A (10), which exhibited activity against transient receptor potential (TRP) channels.20 Subsequently, we described a series of unusual polyketides, onydecalins (11-14), with anti-TRP and anti-Histoplasma activities.21 Here, we describe further new polyketide structural families encompassing aintennols (1-6) and aiorsellinates (7-9). We identified some of the BGCs linked to A. pyridodomos compounds by sequence analysis and heterologous expression. Our data suggest that Onygenales is a rich source of untapped secondary metabolites.

Results and Discussion

Biosynthetic Pathways in A. pyridodomos.

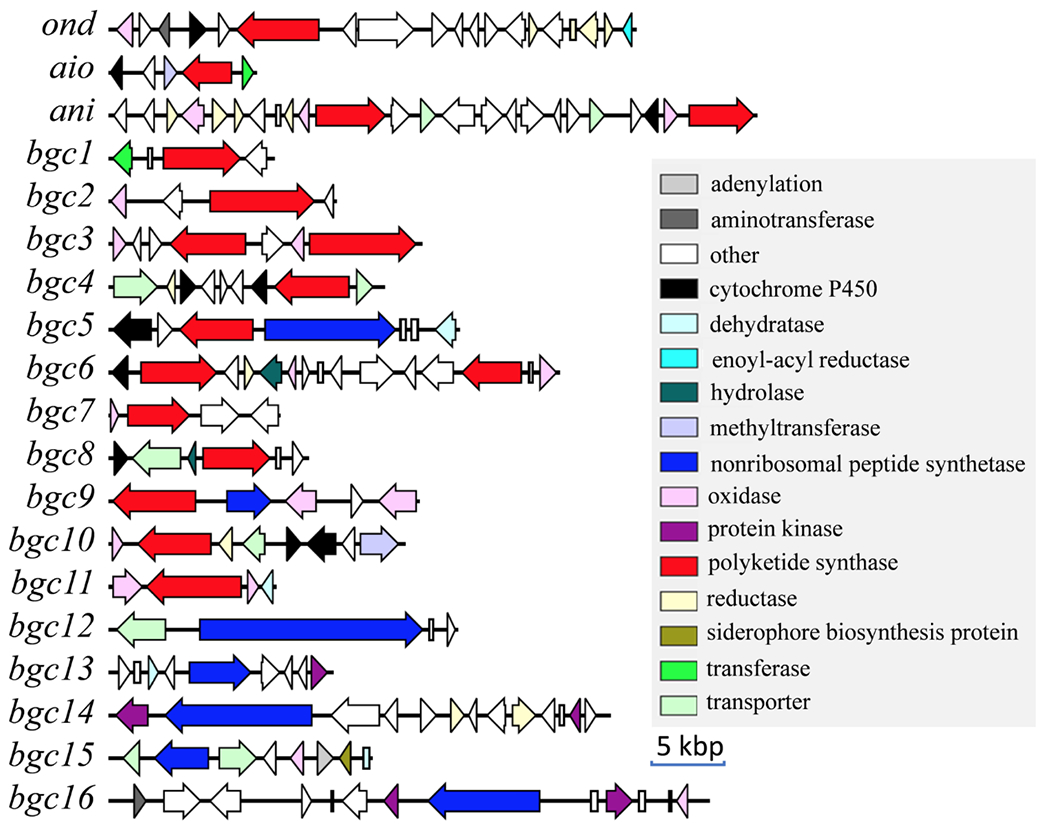

A. pyridodomos E110162 was sequenced with Illumina HiSeq, providing a draft genome with 526 scaffolds. Using the antiSMASH22 algorithm with cluster finder,23 we identified 86 putative BGCs in the genome. The contigs containing BGCs were manually examined to ensure that they contained the entire BGC, and that BGCs did not span multiple scaffolds. We excluded the category “cf_putative”, which are speculative BGC calls, leading to 32 BGCs belonging to well-defined secondary metabolic classes. We focused on the 19 polyketide and nonribosomal peptide metabolic BGCs (Figure 1), because these are important biosynthetic families in fungi with extensive experimental data.24, 25 Twelve BGCs contained at least one polyketide synthase (PKS), five contained a nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS), and two contained a PKS and an NRPS. There were no hybrid PKS-NRPS genes26 in the genome.

Figure 1.

Predicted PKS and NRPS BGCs in the A. pyridodomos genome.

Comparison with Other Fungal Genomes.

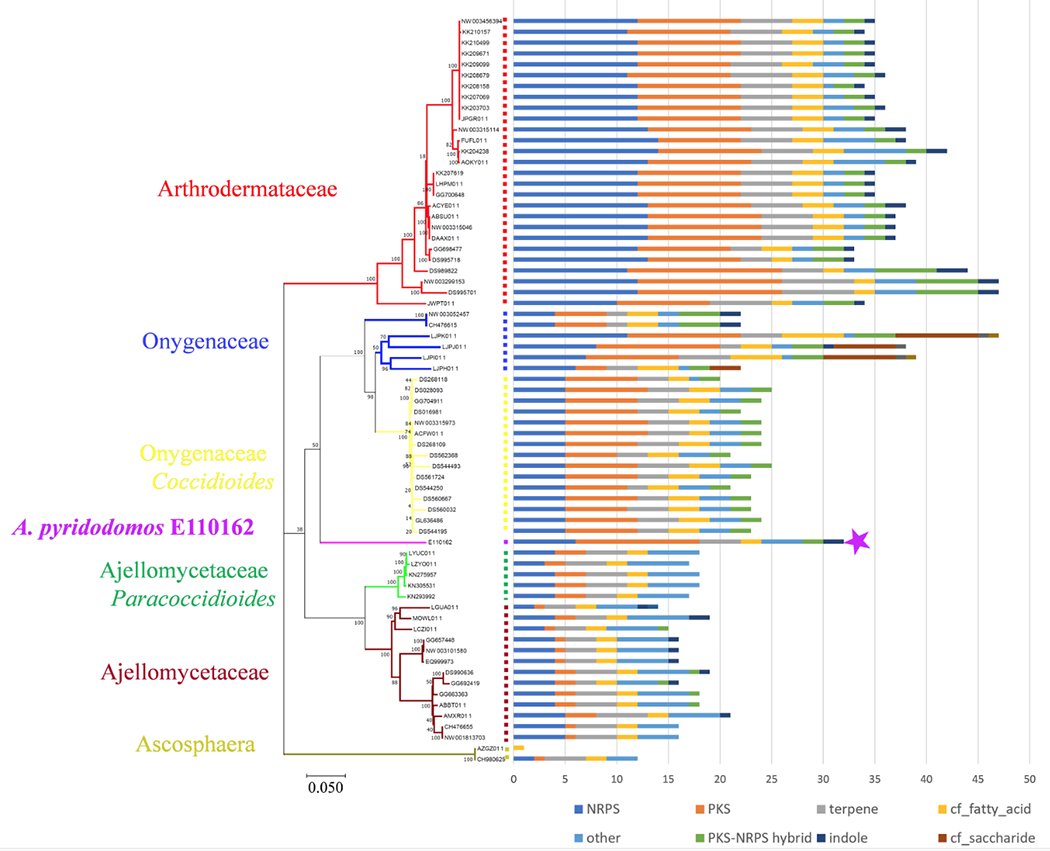

We sought to understand the A. pyridodomos genome in comparison to those in other Onygenales. We compared the identified A. pyridodomos BGCs to those from 68 sequenced Onygenales strains (Table S1) available in GenBank at the time of analysis. To obtain BGCs, we applied antiSMASH22 to the 69 genomes to identify 1888 BGCs (excluding “cf_putative”), of which 1184 contained a PKS, an NRPS, or both. These were overlaid on a maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree of the 69 strains (Figure 2). As expected, >90% of the PKS genes belong to the vast group of fungal type I iterative PKSs.24 Families Arthrodermataceae and Onygenaceae contain the most abundant BGCs, while the Ajellomycetaceae family contains relatively fewer. Ascosphaera, which is deeply branched within the Onygenales tree, contains the fewest BGCs.

Figure 2.

Onygenales contains a wealth of secondary metabolic BGCs. The purple star indicates A. pyridodomos. A phylogenetic tree (left) was obtained by concatenating 17 conserved proteins in 69 Onygenales strains with available genome sequences and performing a maximum-likelihood method with MEGA-X.27 Bootstrap values are indicated at the nodes of the tree. Family-level taxonomy is indicated, except for the important genera Coccidioides and Paracoccidiodes, which belong to Ajellomycetaceae and Onygenaceae, respectively. antiSMASH was used to predict BGCs, which are enumerated in the bar chart at right (excluding the antiSMASH category “cf_putative”).

We next sought to determine whether the Onygenales BGCs were similar to those from other fungi. We focused on PKS and NRPS clusters, which are the most straightforward to analyze. Using antiSMASH, we found that only 38 out of the 1184 BGCs had significant similarity (over 70% of the genes show similarity to known clusters) to BGCs from fungi outside of the Onygenales. These related BGCs were found in 17 strains from order Eurotiales and 10 strains from class Sordariomycetes (Figure S1). Many of these 27 strains are plant or insect pathogens. Thus, while fungal PKS and NRPS genes share many common features, this analysis suggests that Onygenales encodes a unique suite of compounds in comparison to other fungi.

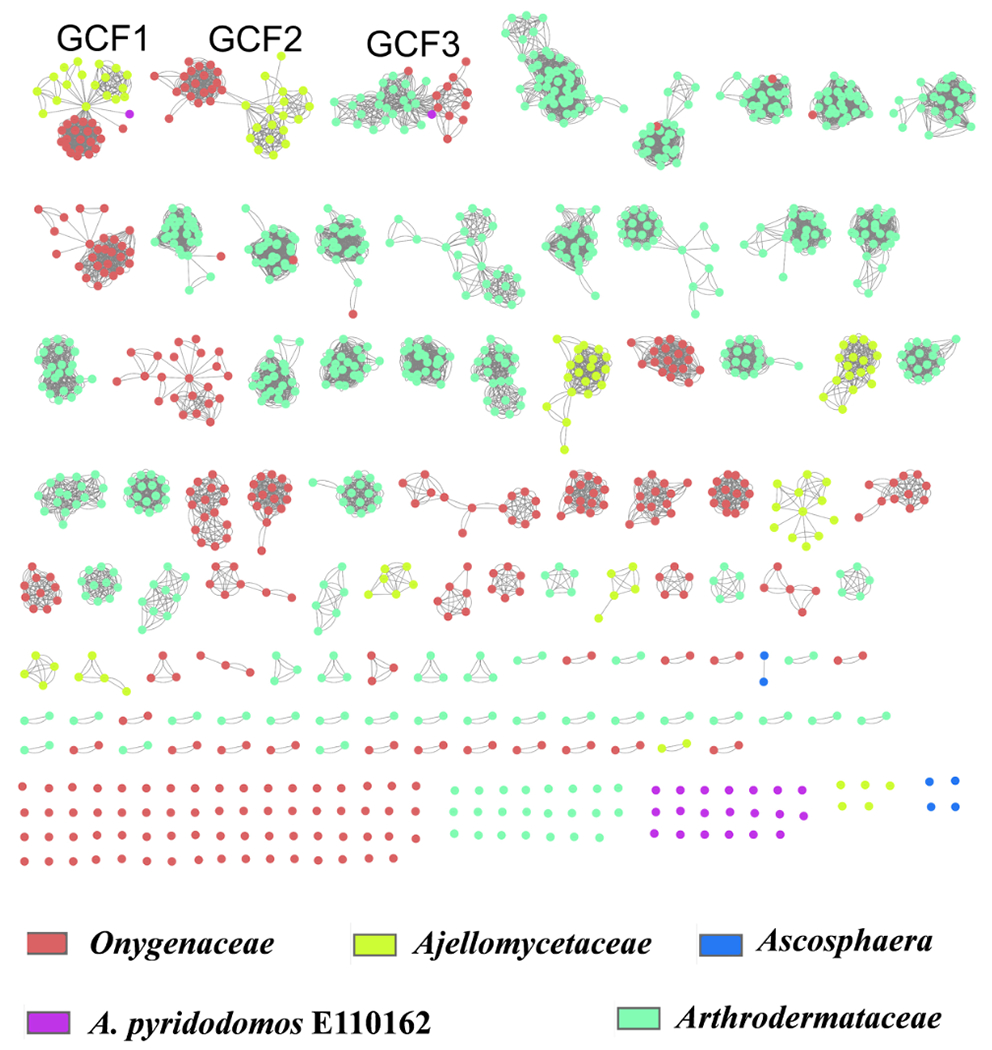

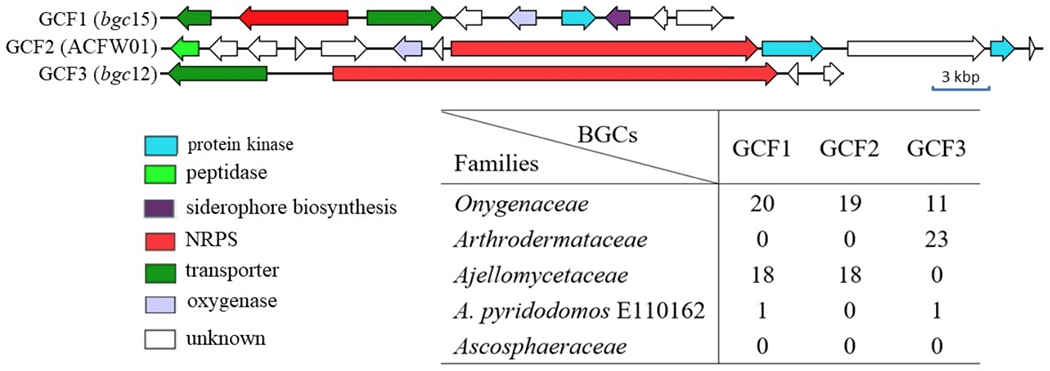

We asked how the Onygenales BGCs were distributed within the order, comparing the fungal taxonomic family to the biosynthetic Gene Cluster Family (GCF), as defined by Medema et al.28 The concept of GCF was introduced so that whole biosynthetic pathways could be compared.29 Using Medema’s method,28 1184 PKS and NRPS BGCs were classified into 103 GCFs and 119 singletons, for a total of 222 groups. We used two different methods, Cytoscape networking30 and cluster analysis28 to graphically analyze the distribution of GCF in comparison to fungi at the family level (Figures 3 and S2). Both methods revealed that the majority of GCFs (96% of the 222) are specific to a single fungal family within Onygenales. Seven GCFs in the network are shared by two different families, and only two GCFs (GCF1 and GCF3) are more widely distributed in Onygenales. These results suggest a family-level specialized metabolite conservation in Onygenales.

Figure 3.

Cytoscape analysis reveals that most Onygenales biosynthetic pathways are specific to individual families of fungi. We identified 1184 PKS and NRPS BGCs, which are indicated by circles. Connections of the circles by lines indicate GCFs. The color of each circle indicates the fungal family that contains the BGC. Thus, the appearance of multiple colors linked by lines indicate GCFs that are distributed among more than one fungal family. If only a single color is present, the BGC was found only within a single family.

All of the A. pyridodomos BGCs are singletons, except for two pathways belonging to the widely distributed GCFs 1 and 3. This result reinforces the potential family-level status of this strain. We are currently working to refine this phylogenetic analysis.

We examined the three most widely occurring GCF1-3, all of which include an NRPS gene (Figure 4). Based upon previous studies, these common GCFs are likely responsible for the production of hydroxamate siderophores, involved in iron acquisition.7 For example, Hwang et al. identified GCF1 as an iron-regulated siderophore pathway (SID1) required for host colonization,8 although the chemical structure of the siderophore was not defined. Thus, the biosynthetic pathways found in Onygenales are relatively specific to the family level except for siderophores involved in iron acquisition.

Figure 4.

Gene organization of the most common NRPS GCFs shared among multiple families in Onygenales. GCF1 is comprised of relatives of the previously identified SID1.8

Overall, these results indicate that Onygenales contain a mostly new and uncharacterized biosynthetic potential, at least in the PKS/NRPS gene families. Because the Onygenales include important human pathogens, characterizing this potential should be a priority.

A limitation in this study results from our current understanding of fungal biosynthesis. Fungal PKS genes are often similar, yet their chemical products differ in unpredictable ways. These differences are caused both by the PKSs and by combinations of different tailoring enzymes that modify PKS products. This reinforces the need to characterize the chemicals from Onygenales: which of the compounds are actually produced, do they contribute to pathogenesis, and do they represent new structural motifs?

Polyketides from A. pyridodomos.

We grew A. pyridodomos for at least 1-2 months to obtain natural products, and for up to a year to obtain further compounds. We selected the medium ISP2 because it was one of the few that afforded reasonable growth for this otherwise challenging isolate. While we initially worked with extracts isolated after a few weeks of fermentation, because of the slow growth of the fungus we left the culture for two months. The fungus continued to grow, and a much larger abundance of polyketides was produced. Therefore, we left the culture for a much longer period (one year) to see whether the yield would increase. To our surprise, not only did the fungus keep growing, but additional metabolites appeared after a one-year period. The new compounds appeared likely to be non-enzymatic, but interesting and novel, rearrangement products31 (Table 1). Thus, extended fermentation may provide a method to increase chemical diversity from microbial strains. Because of the lengthy nature of this experiment, it was performed once. For this reason, it is worth attempting on other systems before generalizing our result.

Table 1.

Compound production after extended fermentation.

| Time | Shaking / 30 °C | Static / 21 °C |

|---|---|---|

| 25 days | 1,3,4,7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 | - |

| 60 days | 1,3,4,7, 8, 9, 11, 12 | - |

| 365 days | - | 1,2,3,4,5,6,7, 8, 9, 11, 12 13,14 |

In total, 14 polyketides (1-14) were isolated from A. pyridodomos. Our strategy was to purify all of the abundant metabolites, as Onygenales have rarely been examined chemically. We described five of these previously: onydecalins A-D (11-14)21 and oxazinin A (10).20 Here, we describe six further oxazinin analogs (aintennols A-F (1-6)) and three other polyketides (aiorsellinates A-C (7-9)). Of these, 5, 6, 8, 9, 13, and 14 likely represent rearrangement products (vide infra). The remainder of compounds represent mature products or intermediates, as experimentally defined below. Compounds 5, 6, 13, and 14 were isolated only after 1-year fermentation (Table 1).

Aintennol A (1) was isolated as pale yellow solid with a molecular formula of C22H30O2. 1H, 13C, COSY and HSQC NMR data (Table 2 and Figure 5) revealed that 1 has some structural features similar to those of oxazinin A (10). A triplet olefinic proton (δ 5.34, H-14) exhibited a strong COSY correlation with a methylene group (δ 3.34, H2-13) and a weak correlation with two singlet methyl signals (δ 1.76, 6H, H3-16, 17), indicating the presence of a prenyl group in 1. A second prenyl group in the structure can be deduced from the NMR data (δ 5.18, H-19; δ 3.21, H2-18; δ 1.69, 1.72, H3-21,22;). The COSY spectrum of 1 contained cross-peaks between H-7/H-8/H-9/H-10/H3-11, indicating that 1 has the same pentadienyl moiety as that in 10. Additionally, five non-protonated carbons (δ 153.0, 127.1, C-1, C-2; 131.7, 135.5, 123.0, C-3, C-4, C-5) and an aromatic methine group (δH 6.90, δC 129.8) were observed in the 13C NMR data, revealing a pentasubstituted benzene ring. An oxygenated methylene group was observed at δH 4.93, δC 61.5, and an exchangeable proton signal at δ 7.30 was assigned to a phenolic hydroxy group. Finally, HMBC correlations from H2-12 to C-1, C-6, C-5, from H-7 to C-6, from H2-13 to C-1, C-2, C-3, from H2-18 to C-3, C-4, C-5, and from H-3 to C-13, C-18 located the substitutions of the two benzene groups, the CH2OH group and the pentadienyl moiety on the pentasubstituted phenyl ring in 1. The deshielded chemical shift of C-1 (δ 153.0) of the benzene ring indicated a hydroxy group at C-1, establishing the complete structure of 1.

Table 2.

1H (500 MHz) and 13C NMR (125 MHz) data of compounds 1 and 2 in CDCl3.

| No. | 1 | 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| δC, type | δH, (J in Hz) | δC, type | δH, (J in Hz) | |

| 1 | 153.0, C | 159.0, C | ||

| 1-OH | 7.30, brs | 12.07, s | ||

| 2 | 127.1, C | 128.4, C | ||

| 3 | 129.8, CH | 6.90, s | 137.6, CH | 7.17, s |

| 4 | 131.7, C | 130.6, C | ||

| 5 | 135.5, C | 139.6, C | ||

| 6 | 123.0, C | 118.2, C | ||

| 7 | 126.4, CH | 6.40, d (15.7) | 123.6, CH | 6.57, d (15.7) |

| 8 | 135.8, CH | 6.05, dd (15.7, 10.4) | 139.8, CH | 6.12, dd (15.7, 10.4) |

| 9 | 131.7, CH | 6.22, dd (14.6, 10.8) | 131.2, CH | 6.28, dd (14.7, 10.8) |

| 10 | 130.1, CH | 5.76, dq (14.6, 6.8) | 132.4, CH | 5.85, dq (10.8, 6.8) |

| 11 | 18.2, CH3 | 1.83, d (6.8) | 18.6, CH3 | 1.85, d (6.8) |

| 12 | 61.5, CH2 | 4.93, s | NDa | 10.10, s |

| 13 | 29.2, CH2 | 3.34, d (7.3) | 31.5, CH2 | 3.33, d (7.3) |

| 14 | 122.3, CH | 5.34, t (7.3) | 121.6, CH | 5.31, t (7.3) |

| 15 | 133.7, C | 132.5, C | ||

| 16 | 18.1, CH3 | 1.76, s | 17.9, CH3 | 1.72, s |

| 17 | 26.0, CH3 | 1.76, s | 25.7, CH3 | 1.76, s |

| 18 | 32.4, CH2 | 3.21, d (7.4) | 27.3, CH2 | 3.24, d (7.4) |

| 19 | 123.6, CH | 5.18, t (7.4) | 122.6, CH | 5.16, t (7.4) |

| 20 | 131.6, C | 133.4, C | ||

| 21 | 18.2, CH3 | 1.69, s | 17.9, CH3 | 1.71, s |

| 22 | 26.3, CH3 | 1.72, s | 25.7, CH3 | 1.73, s |

ND=not detected.

Figure 5.

Key COSY and HMBC correlations for compounds 1-7.

Aintennol B (2) was isolated as yellow solid with molecular formula C22H28O2, which is two protons lighter than 1. This was explained by the substitution of an alcohol in 1 with an aldehyde in 2. The 1H NMR data (Table 2 and Figure 5) had very similar signals as those of 1, except for the absence of the CH2OH group in 2. Instead, a deshielded singlet proton was observed at δ 10.10 (H-12), consistent with an aldehyde at C-12. HMBC correlations from H-12 to C-1, C-6 and C-5 confirmed the aldehyde substitution at C-6 in the benzene ring. Further, the IR spectrum of 1 in comparison to 2 was consistent with the addition of a carbonyl. However, no HSQC correlation for H-12 was observed. Proton H-12 was not exchangeable, as overnight incubation with 10% CD3OD did not wash out the signal. Evidence for an aldehyde was further established in the deshielded shift of 1-OH (δ 7.30 brs in 1 versus δ 12.07 in 2), resulting from a hydrogen bond between 1-OH and 12-CHO. Finally, the UV spectrum of 2 contains a λmax almost identical to that of albicucin B,32 also suggesting conjugation with an aldehyde.

Aintennols C (3) and D (4) were isolated as isomeric, pale yellow solids with the molecular formula C22H28O4. The 1D NMR data (Table 3 and Figure 5) of 3 and 4 are similar to those of 1. The major difference in comparison to 1 is that in 3 one of the isoprene groups was replaced with two singlet methyl groups (δ 1.62, 1.20, H-16, H-17), a singlet oxygenated methine group (δH 4.40, H-3, δC 77.4 C-3), an oxygenated non-protonated carbon (δC 84.4 C-2), and a ketone carbonyl (δC 194.7, C-4). HMBC correlations from H3-16/H3-17 to C-2, C-3, from H-3 to C-2 and C-4, and from H-6 to C-4 supported a 4-chromanone moiety in 3, identical to that found in oxazinin A (10). A spin system from H-11 to H-15 was determined to result from a pentadienyl unit based upon COSY correlations. The chemical shifts of the carbons in this pentadienyl unit are very similar to those found in oxazinin A, indicating the same trans double bonds in 3, while the chemical shifts of the protons are very different. (This difference is caused by deshielding from an adjacent aromatic group in 10.) Because of overlap between H-11 and H-12, a HOMODEC decoupling experiment (Figure S56) helped to improve coupling constant accuracy. An unusually small coupling constant was observed between H-12 and H-13 (JH12-H13 = 6.7 Hz). The 1D NMR data of 4 differed from those of 3 only in the chemical shifts and J-values of the pentadienyl unit, especially for positions 11, 12, and 13 (Table 3). The coupling constant (JH11-H12 = 11.3 Hz) suggested a cis configuration of the C-11/C-12 double bond in 4. There was no observed Cotton effect in the ECD spectrum of 3 and 4, despite a strong dynode voltage corresponding to the UV absorption spectra. Thus, as found for 10, 3 and 4 are racemic.

Table 3.

1H (500 MHz) and 13C NMR (125 MHz) data of compounds 3 and 4 in CD3CN.

| 3 | 4 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| δC, type | δH, (J in Hz) | δC, type | δH, (J in Hz) | |

| 2 | 84.4, C | 84.2, C | ||

| 3 | 77.4, CH | 4.40, s | 77.5, CH | 4.44, s |

| 4 | 194.7, C | 195.1, C | ||

| 5 | NDa | 118.9, C | ||

| 6 | 125.9, CH | 7.52, s | 125.6, CH | 7.57, s |

| 7 | 134.0, C | 134.1, C | ||

| 8 | 147.5, C | 146.7, C | ||

| 9 | 128.8, C | 126.1, C | ||

| 10 | 157.5, C | 156.7, C | ||

| 11 | 126.3, CH | 6.57, d (2.9) | 125.0, CH | 6.29, d (11.3) |

| 12 | 137.8, CH | 6.56, d (6.7) | 133.0, CH | 6.41, dd (11.9, 11.3) |

| 13 | 132.5, CH | 6.32, ddd (15.2, 6.7, 2.9) | 128.4, CH | 5.74, dd (15.0, 11.9) |

| 14 | 132.9, CH | 5.91, dq (15.1, 6.8) | 133.5, CH | 5.89, dq (15.5, 6.8) |

| 15 | 18.4, CH3 | 1.84, d (6.8) | 18.3, CH3 | 1.69, d (6.7) |

| 16 | 26.9, CH3 | 1.62, s | 27.1, CH3 | 1.62, s |

| 17 | 18.0, CH3 | 1.20, s | 18.1, CH3 | 1.23, s |

| 18 | 32.7, CH2 | 3.31, m | 32.3, CH2 | 3.22, d (6.0) |

| 19 | 123.3, CH | 5.20, t (6.2) | 123.3, CH | 5.20, t (6.2) |

| 20 | 133.8, C | 133.8, C | ||

| 21 | 17.8, CH3 | 1.71, s | 17.8, CH3 | 1.66, s |

| 22 | 26.0, CH3 | 1.74, s | 26.0, CH3 | 1.71, s |

| 23 | 56.6 CH2 | 4.61 d (11.7), 4.55 d (11.7) | 57.3, CH2 | 4.53, brs |

ND=not detected.

Aintennols E (5) and F (6) were isolated only after 1-year fermentation as isomeric, pale yellow solids with the molecular formula C22H26O4. The 1D NMR data (Table 4 and Figure 5) of 5 and 6 are almost identical. The spectra for 5 and 6 were similar to those for 3 and 4, with most differences at C-23 and C-11-C-15. A ketone carbonyl (δC 198.1, C-23), three methines (δC 40.5, C-11, 46.9, C-12, 54.7, C-13), a methylene (δC 38.2, C-14), and a doublet methyl (δC 12.7, C-15) were observed in the 1D NMR data of 5. COSY correlations between H-11/H-12/H-13/H2-14/H3-15 suggested that all of the protons for the additional sp3 carbons are in a single spin system. HMBC correlations from H3-15 to C-11, C-12, C-13, and from H2-14 to C-12 and C-23 established a benzobicyclo[3.1.1]heptanone moiety in the structure of 5. HMBC correlations from H-14 to C-8 supported the link between the benzobicyclo[3.1.1]heptanone moiety and the prenylated benzene ring. The chemical shifts and coupling constants for H-14 in both 5 and 6 are almost identical to those of a synthetic compound, endo-2-isopropyl-2,3-dihydro-1,3-methanonaphthalen-4(1H)-one, but drastically different from exo-2-isopropyl-2,3-dihydro-1,3-methanonaphthalen-4(1H)-one.33 This finding established an endo-benzobicyclo[3.1.1]heptanone moiety in 5 and 6. There was no observed Cotton effect in the ECD spectra of 5 and 6, indicating that both are racemic. The 1H NMR and 13C spectra of 5 and 6 are almost identical, with only slight differences between them. In extended incubation in methanol, 5 and 6 slowly interconvert, indicating that the difference between the compounds is at a labile center, and not at the carbocycle. Because C-3 is racemic in compounds 3 and 4, and the C-3 position is labile due to the adjacent carbonyl, it is likely that 5 and 6 differ in the relative orientation between C-3 and the carbocyclic portion. The absence of a Cotton effect in 5 and 6 indicate that the carbocycle is also racemic. This indicates that the formation of benzobicyclo[3.1.1]heptanone moiety in 5 and 6 is likely non-enzymatic. Thus, 5 and 6 are both racemic; they are diastereomers that differ by the relative configuration between C-3 and the endo-benzobicyclo[3.1.1]heptanone moiety. The absence of distance correlations between the two halves of the molecules precluded establishment of the relative configurations of 5 and 6.

Table 4.

1H (500 MHz) and 13C NMR (125 MHz) data of compounds 5 and 6 in CD3CN.

| 5 | 6 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| δC, type | δH, (J in Hz) | δC, type | δH, (J in Hz) | |

| 2 | 83.6, C | 83.9, C | ||

| 3 | 76.1, CH | 4.49, s | 76.2, CH | 4.46, s |

| 4 | 193.6, C | 193.3, C | ||

| 5 | NDa | NDa | ||

| 6 | 131.1, CH | 7.77, s | 131.0, CH | 7.78, s |

| 7 | NDa | NDa | ||

| 8 | 156.2, C | 156.0, C | ||

| 9 | NDa | NDa | ||

| 10 | 157.4, C | 157.0, C | ||

| 11 | 40.5, CH | 3.60, q (5.8) | 40.8, CH | 3.60, q (5.8) |

| 12 | 46.9, CH | 3.20, m | 46.4, CH | 3.19, m |

| 13 | 54.7, CH | 3.07, q (5.5) | 55.7, CH | 3.07, q (5.5) |

| 14 | 38.2, CH2 | 2.59, dq (9.4, 5.8); 2.17, d (9.4) | 38.5, CH | 2.59, dq (9.4, 5.8); 2.17, d (9.4) |

| 15 | 12.7, CH3 | 0.83, d (7.0) | 12.2, CH3 | 0.79, d (6.7) |

| 16 | 26.4, CH3 | 1.76, s | 26.1, CH3 | 1.76, s |

| 17 | 17.0, CH3 | 1.24, s | 16.8, CH3 | 1.26, s |

| 18 | 30.7, CH2 | 3.27, m | 30.8, CH2 | 3.27, m |

| 19 | 121.3, CH | 5.05, t (6.2) | 121.6, CH | 5.06, t (6.2) |

| 20 | 132.8, C | 133.1, C | ||

| 21 | 17.7, CH3 | 1.70, s | 17.2, CH3 | 1.70, s |

| 22 | 25.3, CH3 | 1.71, s | 25.4, CH3 | 1.71, s |

| 23 | 198.1, C | 197.3, C | ||

ND=not detected.

Aiorsellinate (7) was isolated as a colorless oil with the molecular formula C20H30O9. The presence of a benzene ring in 7 was deduced by the interpretation of HMBC and COSY correlations (Figure 5). The six aromatic carbons, including a methine (C-6, δ112.6) and five non-protonated carbons (C-2~5, δ120.9, 157.0, 119.3, 157.7 and C-7 δ135.0), indicated the presence of a highly substituted doubly-oxygenated benzene ring in the structure of 7. The HMBC correlations from H2-9 to C-3, C-4 and C-5 established the prenyl group at C-4. The HMBC correlations from H3-8 to C-2, C-6 and C-7, from H-6 to C-2, C-4 and C-5, from H3-14 to C-3, as well as the chemical shifts of C- 3 and C-5 established the placement of the other groups on the benzene ring. The chemical shift of C-2 and the ester carbonyl at C-1 determined the position of the ester and established the presence of a prenylated orsellinate moiety. The remaining six oxygenated sp3-hybridized carbons and five alcohol exchangeable protons (Table 5) suggested a hexitol moiety, which was confirmed by COSY correlations between H-1’/H-2’/H-3’ and between H-6’/H-5’/H-6’. Finally, the HMBC correlation from H-3’ to C-1 established an ester bond between the orsellinate moiety and hexitol moiety. To further confirm the structure, 7 was hydrolyzed and analyzed by LC-MS. A new product (m/z 251 [M+H]+) was observed, which corresponded to the expected carboxylate of 7 (Figure S5). Mass spectrometric fragmentation data of 7 provided further evidence for the structure (Figure S6). In particular, an ion at m/z 233 suggested a loss of a hexitol (182 Da) in comparison to an ion at m/z 415 ([M+H]+), while the ion at m/z 251 suggested an addition of H2O to the ion at m/z 233. An ion at m/z 195, which is 56 Da less than the ion at m/z 251, suggested a loss of C4H8 from the prenyl group.

Table 5.

1H (500 MHz) and 13C NMR (125 MHz) data of compounds 7-9 in DMSO-d6.

| No. | 7 | 8 | 9 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| δC, type | δH, (J in Hz) | δC, type | δH, (J in Hz) | δC, type | δH, (J in Hz) | |

| 1 | 168.7, C | 167.2, C | 167.7, C | |||

| 2 | 120.9, C | 119.8, C | 119.1, C | |||

| 3 | 157.0, C | 156.3, C | 155.9, C | |||

| 4 | 119.3, C | 118.4, C | 118.0, C | |||

| 5 | 157.7, C | 156.9, C | 156.5, C | |||

| 6 | 112.6, CH | 6.50, s | 112.0, CH | 6.43, s | 111.7, CH | 6.44, s |

| 7 | 135.0, C | 134.2, C | 133.7, C | |||

| 8 | 20.1, CH3 | 2.19, s | 20.6, CH3 | 2.14, s | 19.6, CH3 | 2.12, s |

| 9 | 23.0, CH2 | 3.22 d, (6.8) | 22.4, CH2 | 3.15, d (6.7) | 22.2, CH2 | 3.16, d (6.7) |

| 10 | 123.1, CH | 5.16, t (6.8) | 123.0, CH | 5.10, t (6.5) | 122.4, CH | 5.11, t (6.7) |

| 11 | 131.3, C | 130.1, C | 129.7, C | |||

| 12 | 26.2, CH3 | 1.62, s | 24.9, CH3 | 1.60, s | 25.3, CH3 | 1.60, s |

| 13 | 18.2, CH3 | 1.74, s | 15.1, CH3 | 1.68, s | 17.0, CH3 | 1.68, s |

| 14 | 62.7, CH3 | 3.69, s | 62.8, CH3 | 3.63, s | 61.8, CH3 | 3.64, s |

| 1’ | 64.0, CH2 (64.3)a | 3.65, m; 3.44, m | 60.5, CH2 | 3.81, m; 3.66, m | 67.6, CH2 | 4.48, d (11.3); 4.11, dd (11.3, 6.9) |

| 1’-OH | 4.39, t (5.2) | 4.59, t (5.0) | ||||

| 2’ | 71.3, CH (71.2) a | 3.87, m | 75.2, CH | 5.02, m | 68.3, CH | 3.74, dd (8.0, 7.0) |

| 2’-OH | 5.00, d (5.3) | |||||

| 3’ | 73.5, CH (73.8) a | 5.27, d (7.4) | 67.5, CH | 3.97, dd (7.5, 7.5) | 71.0, CH | 3.45, m |

| 3’-OH | 4.52, d (7.5) | |||||

| 4’ | 71.0, CH (71.1) a | 3.42, m | 70.9, CH | 3.45, m | 69.4, CH | 3.59, m |

| 4’-OH | 4.35, d (5.7) | 4.47, d (5.2) | ||||

| 5’ | 69.7, CH (69.7) a | 3.85, m | 70.9, CH | 3.36, m | 69.2, CH | 3.56, m |

| 5’-OH | 4.74, d (5.2) | 4.22, d (8.0) | ||||

| 6’ | 63.5, CH2 (63.8) a |

3.63, m; 3.43, m | 63.7, CH2 | 3.60, m; 3.36, m | 63.6, CH2 | 3.59, m; 3.37, m |

| 6’-OH | 4.58, t (5.0) | 4.34, t (5.6) | ||||

13C Chemical shifts (obtained from HSQC spectrum) in compound 7a.

Aiorsellinates B (8) and C (9) were constitutional isomers of 7. The NMR data of 8 and 9 were very similar to those of 7 except for the chemical shifts of the hexitol moiety. In comparison to 7, the chemical shifts of protons and carbon at C-1’ (δH 4.48, 4.11, δC 67.6) in 8 were deshielded, while in 9 those at C-2’ (δH 5.02, δC 75.2) were deshielded. This suggested ester bond migration to C-2’ in 8 and to C-1’ in 9, respectively. Indeed, treatment of 7 in Na2CO3 solution overnight led to an accumulation of 8 and 9. In early time points of the fungal fermentation (10 days), only 7 was present, while at later points 8 and 9 accumulated. Because 7 was the major component in the extract of the fungus at all time points, 7 is the likely enzymatic product of the pathway.

Coupling constants indicated that the hexitols in 7-9 were likely to be either sorbitol or mannitol. Chemical shifts of the hexitols in 7-9 matched those of mannitol very well, especially C-2’ to C-6’ of 7, which were almost identical to the same carbons found in mannitol. Analog 7a was synthesized and had nearly identical chemical shifts and coupling constants as 7, supporting the presence of mannitol. By comparing the experimental and calculated ECD spectra (Figure S7) of 7, the hexitol was determined to be D-mannitol.

Biological Activities of A. pyridodomos Polyketides.

Several of the new compounds were active in assays. We first investigated the extract because it showed activity against a panel of transient receptor potential (TRP) channels. TRPs are important throughout the body and include several channels important in itch and pain, which may potentially be of interest in topical fungal infections.34 However, the purified compounds were only modestly active. In particular, 1 was active against TRPV3 and TRPV4 at 32 and 70 μM, respectively. The compounds were tested for activity against Histoplasma capsulatum. Several compounds exhibited modest activity (Table 6), with selectivity for H. capsulatum in comparison to other fungi.

Table 6.

Anti-Histoplasma Activity of Purified Compounds.

| compound | Histoplasma IC50 (μg/mL) |

|---|---|

| 1 | 8 |

| 3 | 16 |

| 5 | 32 |

| 6 | 64 |

| 13a | 2 |

| 14a | 16 |

| Amphotericin B | 0.5 |

| Itraconazole | 0.001 |

previously reported data21

Identification of Biosynthetic Gene Clusters.

Biogenetic hypotheses for 1-14 were proposed based upon structural data. Compounds 1-14 are all polyketide derivatives that are likely to result from one of the 14 PKS genes in the genome. Aintennols (1-6) and oxazinin (10) likely result from a single biosynthetic pathway, in which 1 or 3 is the probable primary enzymatic product. This pathway would require at least one prenyltransferase, at least one oxidase, and at least one PKS with a terminal reduction domain. Indeed, one BGC was identified to have all of these features, which were absent in other clusters in the genome; this cluster was named “ain” for its putative role in biosynthesis of 1 (Figure S4). Onydecalins (11-14) were previously defined as biogenetically similar to betaenones,35 the biosynthesis of which has been well defined by the Oikawa group;36 a single betaenone-like cluster (ond) is present in the genome (Figure S8). Work is ongoing in our labs to biochemically confirm this assignment.

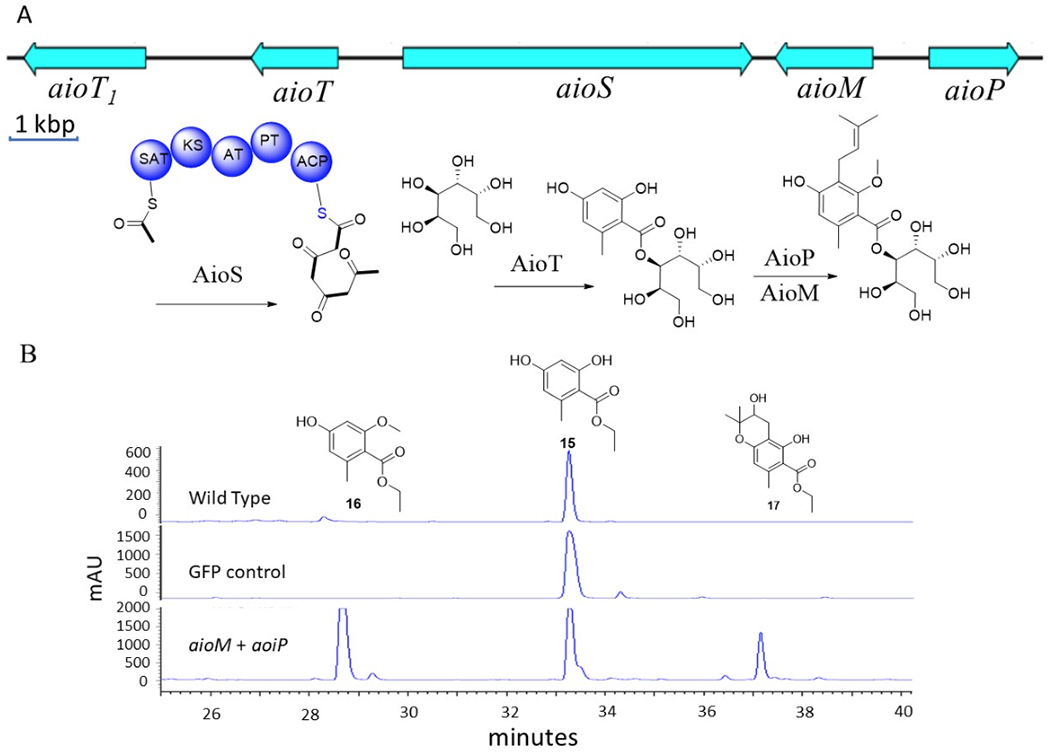

Finally, aiorsellinates (7-9) originate with the single compound 7. In this instance, the core structure appears to be composed of orsellinic acid, the biosynthesis of which has been well studied for decades,37 while new decorations of O-methylation, prenylation, and esterification make the compound unique. A single BGC, aio (Figure 6), contained putative orsellinate PKS (AioS), prenyltransferase (AioP), methyltransferase (AioM), and possible mannitol transferase (AioT) genes. Predicted AioS is very similar to characterized orsellinic acid synthases, except that it terminates with an acyl carrier protein domain instead of a thioesterase. We propose that the neighboring AioT is likely to be involved in the transfer of the ACP-linked orsellinate group, in analogy to a similar protein involved in trichothecene sp. acetylation. Other alternatives include the possibility that mannitol could be added as a detoxification mechanism, which may not be encoded by AioT.

Figure 6.

A) aio gene cluster and domain organization of PKS gene. B) The genes aioT, aioS, aioM, and aioP were overexpressed in F. heterosporum. Incubtion with precursor analog 15 led to formation of two new compounds (16 and 17), as shown in HPLC traces at 290 nm.

To confirm these assignments, we turned to heterologous expression in a model fungus. This route was chosen because of the challenge of generating a new genetic model,38 especially because we have not yet found conditions under which sporulation occurs for this new family. Genes aioS, aioM, aioP, and aioT were cloned into an expression vector that we designed for high-titer polyketide expression and then transformed either singly or in combination into the expression host, Fusarium heterosporum.39 In some cases, we have detected >1 g/kg of heterologous polyketides using this strategy. However, in this instance no new products could be detected. We reasoned that the likely limiting factor would be the PKS, as occasionally these genes do not adapt well to heterologous systems. Therefore, we added orsellinate ethyl ester to the medium (for better cell penetration in comparison to the free acid), affording the predicted prenylated and methylated products only when the correct genes were in place (Figure 6). These derivatives were further modified by oxidation of the isoprene group in the course of fermentation by a nonspecific oxidase in the F. heterosporum genome, indicating that F. heterosporum may not be a good host for heterologous production of 1-3. By contrast, in control fermentations consisting of wild type F. heterosporum or a mutant containing GFP in place of aio genes, no new products were detected unless orsellinic acid ethyl ester was supplied. This demonstrates that aioP and aioM are the functional orsellinate prenyltransferase and methyltransferase, respectively.

Conclusion.

We describe 14 natural products that are so far unique to a new family of Onygenales fungi represented by A. pyridodomos. We tentatively assigned their BGCs and confirmed one of the assignments by heterologous expression. A large number of uncharacterized natural products and BGCs await analysis in the order Onygenales, which is a key group of pathogenic fungi.

General Experimental Procedures

Circular dichroism spectra were obtained on a Jasco J720A spectropolarograph. IR spectra were measured on a thermal Fisher iS50 Fouriertransform IR spectrometer. NMR data were collected using either a Varian INOVA 500 (1H 500 MHz, 13C 126 MHz) NMR spectrometer with a 3 mm Nalorac MDBG probe or a Varian INOVA 600 (1H 600 MHz, 13C 150 MHz) NMR spectrometer equipped with a 5 mm 1H[13C,15N] triple resonance cold probe with a z-axis gradient, utilizing residual solvent signals for referencing40. High-resolution mass spectra (HRMS) were obtained using a Bruker APEXII FTICR mass spectrometer equipped with an actively shielded 9.4 T superconducting magnet (Magnex Scientific Ltd.), an external Bruker APOLLO ESI source, and a Synrad 50W CO2 CW laser. Supelco Discover HS (4.6 × 150 mm) and semipreparative (10 × 150 mm) C18 (5 μm) columns were used for analytical and semipreparative HPLC, respectively, as conducted on a Hitachi Elite Lachrom System equipped with a Diode Array L-2455 detector. Unless stated otherwise, all reagents and solvents were purchased from commercial suppliers, and all reactions were carried out under anhydrous conditions with argon atmosphere. Yields were calculated by HPLC chromatography or 1H NMR spectroscopy.

Fermentation and Extraction.

A. pyridodomos strain was grown and extracted as previously described.21

Purification.

The extract B21 (600 mg) from a 1-year-old culture was separated into seven fractions (Fr1-Fr7) on a C18 column using step-gradient elution of MeOH in H2O (20%, 40%, 60%, 70%, 80%, 90%, and 100%). Fraction Fr3 was further subjected to C18 HPLC (35% CH3CN in H2O) to yield compounds 7 (2.5 mg), 8 (1.0 mg) and 9 (1.1 mg). Fr6 was purified by C18 HPLC (85% CH3CN in H2O) to yield compound 1 (4.2 mg). Fr7 was purified by C18 HPLC (89% CH3CN in H2O) to yield compound 2 (1.0 mg). Fr5 was fractionated using a gradient HPLC method (50% CH3CN in H2O to 80% CH3CN in H2O over 20 min) to yield five sub-fractions (Fr5-1-Fr5-5). Fr5-3 was purified by C18 HPLC (63% CH3CN in H2O) to yield compound 3 (8.0 mg) and 4 (7.0 mg). Fr5-4 was purified by C18 HPLC (66% CH3CN in H2O) to yield compound 5 (1.0 mg) and 6 (1.2 mg). Compounds 1, 3, 4, 7, 8, 9 were also isolated from 2-month shaking culture (extracts A)21 following a similar separation procedure.

Aintennol A (1): pale yellow solid; UV (MeOH) λmax 224, 267 nm; IR (polyethylene) νmax 3501, 2972, 1452, 1249, 1230, 1000 cm−1; 1H and 13C NMR (Table 2); HRESIMS m/z 325.2167 [M-H]- (calcd for C22H30O2, 325.2168).

Aintennol B (2): yellow solid; UV (MeOH) λmax 250, 285, 371 nm; IR (polyethylene) νmax 2960, 1692, 1641, 1450, 1301, 1261, 991, 770 cm−1; 1H and 13C NMR (Table 2); HRESIMS m/z 325.2166 [M+H]+ (calcd for C22H28O2, 325.2168).

Aintennol C (3): pale yellow solid; UV (MeOH) λmax 229, 308, 350 nm; IR (polyethylene) νmax 3422, 2981, 1692, 1611, 1440, 1260, 1103 cm−1; 1H and 13C NMR (Table 3); HRESIMS m/z 357.2066 [M+H]+ (calcd for C22H28O4, 357.2066).

Aintennol D (4): pale yellow solid; UV (MeOH) λmax 228, 265, 297, 343 nm; IR (polyethylene) νmax 3421, 2982, 1692, 1602, 1433, 1261, 1104 cm−1; 1H and 13C NMR (Table 3); HRESIMS m/z 357.2067 [M+H]+ (calcd for C22H28O4, 357.2066).

Aintennol E (5): yellow solid; UV (MeOH) λmax 205, 242, 266, 354 nm; IR (polyethylene) νmax 2972, 1691, 1600, 1454, 1212, 1110 cm−1; 1H and 13C NMR (Table 4); HRESIMS m/z 355.1907 [M+H]+ (calcd for C22H26O4, 355.1909).

Aintennol F (6): yellow solid; UV (MeOH) λmax 205, 242, 266, 354 nm; IR (polyethylene) νmax 2972, 1700, 1600, 1453, 1212, 1111 cm−1; 1H and 13C NMR (Table 4); HRESIMS m/z 355.1908 [M+H]+ (calcd for C22H26O4, 355.1909).

Aiorsellinate A (7): pale yellow solid; UV (MeOH) λmax 199, 251 nm; ECD (0.5 mg/mL, methanol), λmax (Δε) 290 (−0.8), 254 (1.23) nm; IR (polyethylene) νmax 3390, 1712, 1598, 1463, 1272, 1080 cm−1; 1H and 13C NMR (Table 5); HRESIMS m/z 415.1969 [M+H]+ (calcd for C20H30O9, 415.1963).

Aiorsellinate B (8): pale yellow solid; UV (MeOH) λmax 199, 251 nm; IR (polyethylene) νmax 3391, 1712, 1598, 1462, 1272, 1081 cm−1; 1H and 13C NMR (Table 5); HRESIMS m/z 415.1970 [M+H]+ (calcd for C20H30O9, 415.1963).

Aiorsellinate C (9): pale yellow solid; UV (MeOH) λmax 199, 251 nm; IR (polyethylene) νmax 3390, 1712, 1599, 1461, 1272, 1082 cm−1; 1H and 13C NMR (Table 5); HRESIMS m/z 415.1969 [M+H]+ (calcd for C20H30O9, 415.1963).

Sequencing.

The mycelium of A. pyridodomos was collected by centrifugation and then extracted as previously described.41 The resulting DNA samples were repurified with the Genomic DNA Clean & Concentrator kit (Zymo Research). Illumina libraries were prepared as ~350 bp inserts from genome DNA. Libraries were sequenced using an Illumina HiSeq 2000 sequencer in 101 bp/125 bp paired-end runs. Raw fasta files were trimmed by sickle and assembled using IDBA_ud 42 (--mink=20 --maxk=100 --step=20 --inner_mink=10 --inner_step=5 --prefix =3 --min_count=2 --min_support=1 --num_threads=0 --seed_kmer=30 --min_contig=200 –similar=0.95 --max_mismatch=3 --min_pairs=3). The genome was annotated using Augustus43 de novo gene prediction parameters, with ‘Coccidioides_immitis’ as the model organism. The resulting gff output file was converted to a GenBank file and submitted to the RAST44–46 online server for gene identification.

GCF Analysis.

The Augustus43 annotation output was converted to a GenBank file and used as the input for a standalone version of antiSMASH 4.0.22 All BGCs were separated into individual GenBank files. Initial pairwise similarity matrices between every BGC pair were calculated using MultiGeneBlast28 with the parameters (-distancekb 10 -minpercid 50 -minseqcov 80), and then normalized as follows: 1) The ‘total score’ (MultiGeneBlast) between the query BGC and itself was set as 1.0; 2) The ‘total score’ between query BGC and target BGC was normalized to the total score between query itself in step 1. BGC pairs with a final pairwise similarity matrix (normalized score) over 0.6 were selected and visualized in Cytoscape30. Each GCF was manually checked by examining the MultiGeneBlast alignment.

Construction of Phylogenetic Tree.

Proteins encoded in Onygenales genomes were obtained using the Augustus annotation output. Seventeen widespread genes present in a single copy in all genomes were identified by performing a blastp search using A. pyridodomos against 68 of other Onygenales genomes. Hits were defined as identity > 80%, query coverage > 0.8 and subject coverage > 0.8. Genes that met those criteria and that were present in all 68 Onygenales genomes were selected and used for phylogenetic analysis. Orthologous genes were aligned using t-Coffee47 (-mode mcoffee -output=msf, fasta_aln). To remove poorly aligned regions, the resulting alignment was subsequently trimmed with trimAl v1.448 with a gap threshold of 0.4. A concatenation of alignment of all conserved proteins was done by PerlScript catfasta2phyml.pl (https://github.com/nylander/catfasta2phyml). The maximum likelihood (ML) trees were constructed using MEGA-X using the Jukes-Cantor model and 500 bootstrap replicates to assess node support.

Bioactivity Screening.

Assays were performed as previously described.21

Synthesis of Compound 7a.

(See Scheme S1.) Ethyl orsellinate (P1) was prepared as reported by Chen et al.49 Ethyl 4-(benzyloxy)-2-hydroxy-6-methylbenzoate (P3) was prepared as described by Zhu et al.50 Product P3 (300 mg) was treated with LiOH (96 mg) in MeOH:H2O (1:2; 10 mL). The solution was refluxed for 5 h to yield product P4 (270 mg). A mixture of product P4 (260 mg), thionyl chloride (2 mL), and DMF (100 μL) in dry CH2Cl2 (150 mL) was heated to reflux for 6 h, and then the extra thionyl chloride was removed under vacuum to yield product P5 (290 mg, oil). 1,2:5,6-Bis-O-(1-methylethylidene)-D-mannitol (262 mg) in THF (100 mL) was pretreated with NaH (40 mg, 60% in mineral oil) for 1 h and added to the flask containing product P5 (210 mg). The resulting mixture was stirred for 2 h to yield product P6 (350 mg). product P6 (300 mg) was dissolved in 100 mL EtOH, 10% palladium on carbon (30 mg) was added, and the mixture was treated with hydrogen gas (1 atm) for 3 h to yield product P7 (200 mg). Product P7 (42 mg) was dissolved in dry DMF (50 mL), and NaH (4 mg, 60% in mineral oil) was added. The mixture was stirred at 40 °C for 2 h and cooled to room temperature. 3,3-Dimethylallyl bromide (14.7 mg, 12 μL) was added, and the mixture was stirred at 60 °C overnight. The product was precipitated by adding H2O (100 mL), filtered and washed by H2O to yield a white solid, which was further treated with 6 M HCl (10 mL) and purified by C18 HPLC (20% MeCN in H2O) to yield compound 7a (2.1 mg): 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6): δH 9.59 (1H, s, 5-OH); 6.34 (1H, s, H-6); 5.16 (1H, d, J = 7.6 Hz, H-3’); 4.95 (1H, t, H-10); 4.83 (1H, d, 2’-OH); 4.57 (1H, d, 5’-OH); 4.43 (1H, t, 6’-OH); 4.30 (1H, t, 1’-OH); 4.22 (1H, d, 4’-OH); 3.75 (1H, m, H-2’); 3.75 (1H, m, H-5’); 3.38 (1H, m, H-4’); 3.63 (3H, s, H-14); 3.62 (1H, m, H-1’a); 3.33 (1H, m, H-1’b); 3.59 (1H, m, H-6’a); 3.38 (1H, m H-6’b); 3.17 (2H, d, H-9); 2.06 (3H, s, H-8); 1.55 (1H, m, H-11); 1.69 (3H, s, H-12); 1.61 (3H,s, H-13). ESIMS: m/z 415 [M+H]+.

Heterologous Expression and Biosynthesis.

See Table S1 for primer sequences. pyrG-aioS+aioT: the pks gene (aioS) was amplified by PCR in two pieces from genomic DNA with primer pairs 160PKS_PyrG_Fwd/in_160PKS_pyrG_Rev and in_160PKS_PyrG_Fwd/ 160PKS_pyrG_Rev. The resulting fragments were cloned into NotI-linerarized pPyrG517-deg3ER_plus_sgfp by yeast recombination to afford pyrG-aioS+gfp plasmid. The acyltransferase gene (aioT) was amplified with primer pair 160Trs_pyrG_Fwd/160Trs_pyrG_Rev and transformed into S. cerevisiae BY4741 together with PmeI-cut pyrG-aioS+gfp for recombination to make the final plasmid.

pHyg-aioM+aioP: the methyltransferase gene (aioM) was amplified with primer pair 160MT-Fwd/160MT-Rev. the prenyltransferase (aioP) was amplified with primer pair 160prenyl-Fwd/ 160prenyl-Rev. Both amplicons were cloned into NotI- and PmeI-cut overexpression vector FH-3 by yeast recombination.

F. heterosporum was transformed with plasmids using previously reported methods.39 The transformed mutant strain carrying the four genes (aioS+aiot+aioM+aioP) was cultured in PDB (150 mL) at 30 °C with shaking at 180 rpm for 14 days. Sterile-filtered compound 15 (20 mg in 0.2 mL of MeOH) was added at the 72 h time point of the culture. The culture was harvested and extracted with EtOAc. The products were analyzed by HPLC-DAD, LC-MS and NMR, resulting in the identification of two new compounds 16 and 17. Compound 16: 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δH 6.27 (1H, s); 6.24 (1H, s); 4.36 (2H, q, J = 7.1 Hz); 3.78 (3H, s); 2.25 (3H, s); 1.36 (3H, t, J = 7.1 Hz). ESIMS: m/z 211 [M+H]+. Compound 17: 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δH 11.87 (1H, s); 6.28 (1H, s); 4.64 (1H, t, J = 8.8 Hz); 4.40 (2H, q, J = 7.1 Hz); 3.04 (2H, m); 2.43 (3H, s); 1.43 (3H, t, J = 7.1 Hz); 1.36 (3H, s); 1.23 (3H, s). ESIMS: m/z 281 [M+H]+.

ECD Calculation.

ECD calculation was performed as previously described.21

Supplementary Material

Chart 1.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was funded by NIH R01GM107557 and R35GM122521 to EWS and CR; and NIH R00AI112691 and R01AI137418 to SB.

References

- (1).Macheleidt J; Mattern DJ; Fischer J; Netzker T; Weber J; Schroeckh V; Valiante V; Brakhage AA Annu. Rev. Genet 2016, 50, 371–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Arias M; Santiago L; Vidal-Garcia M; Redrado S; Lanuza P; Comas L; Domingo MP; Rezusta A; Galvez EM Front. Immunol 2018, 9, 2549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Sharpton TJ; Stajich JE; Rounsley SD; Gardner MJ; Wortman JR; Jordar VS; Maiti R; Kodira CD; Neafsey DE; Zeng Q; Hung CY; McMahan C; Muszewska A; Grynberg M; Mandel MA; Kellner EM; Barker BM; Galgiani JN; Orbach MJ; Kirkland TN; Cole GT; Henn MR; Birren BW; Taylor JW Genome Res 2009, 19, 1722–1731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Whiston E; Taylor JW G3 (Bethesda) 2015, 6, 235–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Yin WB; Chooi YH; Smith AR; Cacho RA; Hu Y; White TC; Tang Y ACS Synth. Biol 2013, 2, 629–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Harvey CJB; Tang M; Schlecht U; Horecka J; Fischer CR; Lin HC; Li J; Naughton B; Cherry J; Miranda M; Li YF; Chu AM; Hennessy JR; Vandova GA; Inglis D; Aiyar RS; Steinmetz LM; Davis RW; Medema MH; Sattely E; Khosla C; St Onge RP; Tang Y; Hillenmeyer ME Sci. Adv 2018, 4, eaar5459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Hilty J; George Smulian A; Newman SL Med. Mycol 2011, 49, 633–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Hwang LH; Mayfield JA; Rine J; Sil A PLoS Pathog. 2008, 4, e1000044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Niu S; Si L; Liu D; Zhou A; Zhang Z; Shao Z; Wang S; Zhang L; Zhou D; Lin W Eur J. Med. Chem 2016, 108, 229–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Hosoe T; Iizuka T; Komai S; Wakana D; Itabashi T; Nozawa K; Fukushima K; Kawai K Phytochemistry 2005, 66, 2776–2779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Wakana D; Hosoe T; Wachi H; Itabashi T; Fukushima K; Yaguchi T; Kawai KJ Antibiot. (Tokyo) 2009, 62, 217–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Wakana D; Itabashi T; Kawai K; Yaguchi T; Fukushima K; Goda Y; Hosoe TJ Antibio.t (Tokyo) 2014, 67, 585–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Fehlhaber HW; Kogler H; Mukhopadhyay T; Vijayakumar EK; Roy K; Rupp RH; Ganguli BN J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 1988, 41, 1785–1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Gamble WR; Gloer JB; Scott JA; Malloch DJ Nat. Prod 1995, 58, 1983–1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Hammerschmidt L; Aly AH; Abdel-Aziz M; Muller WE; Lin W; Daletos G; Proksch P Bioorg. Med. Chem 2015, 23, 712–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Burmester A; Shelest E; Glockner G; Heddergott C; Schindler S; Staib P; Heidel A; Felder M; Petzold A; Szafranski K; Feuermann M; Pedruzzi I; Priebe S; Groth M; Winkler R; Li W; Kniemeyer O; Schroeckh V; Hertweck C; Hube B; White TC; Platzer M; Guthke R; Heitman J; Wostemeyer J; Zipfel PF; Monod M; Brakhage AA Genome Biol. 2011, 12, R7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Desjardins CA; Champion MD; Holder JW; Muszewska A; Goldberg J; Bailao AM; Brigido MM; Ferreira ME; Garcia AM; Grynberg M; Gujja S; Heiman DI; Henn MR; Kodira CD; Leon-Narvaez H; Longo LV; Ma LJ; Malavazi I; Matsuo AL; Morais FV; Pereira M; Rodriguez-Brito S; Sakthikumar S; Salem-Izacc SM; Sykes SM; Teixeira MM; Vallejo MC; Walter ME; Yandava C; Young S; Zeng Q; Zucker J; Felipe MS; Goldman GH; Haas BJ; McEwen JG; Nino-Vega G; Puccia R; San-Blas G; Soares CM; Birren BW; Cuomo CA PLoS Genet. 2011, 7, e1002345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Martinez DA; Oliver BG; Graser Y; Goldberg JM; Li W; Martinez-Rossi NM; Monod M; Shelest E; Barton RC; Birch E; Brakhage AA; Chen Z; Gurr SJ; Heiman D; Heitman J; Kosti I; Rossi A; Saif S; Samalova M; Saunders CW; Shea T; Summerbell RC; Xu J; Young S; Zeng Q; Birren BW; Cuomo CA; White TC MBio 2012, 3, e00259–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Nielsen JC; Grijseels S; Prigent S; Ji B; Dainat J; Nielsen KF; Frisvad JC; Workman M; Nielsen J Nat. Microbiol 2017, 2, 17044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Lin Z; Koch M; Abdel Aziz MH; Galindo-Murillo R; Tianero MD; Cheatham TE; Barrows LR; Reilly CA; Schmidt EW Org. Lett 2014, 16, 4774–4777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Lin Z; Phadke S; Lu Z; Beyhan S; Abdel Aziz MH; Reilly C; Schmidt EW J. Nat. Prod 2018, 81, 2605–2611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Blin K; Wolf T; Chevrette MG; Lu X; Schwalen CJ; Kautsar SA; Suarez Duran HG; de Los Santos ELC; Kim HU; Nave M; Dickschat JS; Mitchell DA; Shelest E; Breitling R; Takano E; Lee SY; Weber T; Medema MH Nucleic. Acids. Res 2017, 45, W36–W41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Cimermancic P; Medema MH; Claesen J; Kurita K; Wieland Brown LC; Mavrommatis K; Pati A; Godfrey PA; Koehrsen M; Clardy J; Birren BW; Takano E; Sali A; Linington RG; Fischbach MA Cell 2014, 158, 412–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Chooi YH; Tang YJ Org. Chem 2012, 77, 9933–9953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Finking R; Marahiel MA Annu. Rev. Microbiol 2004, 58, 453–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Boettger D; Hertweck C Chembiochem 2013, 14, 28–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Kumar S; Stecher G; Tamura K Mol. Biol. Evol 2016, 33, 1870–1874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Medema MH; Takano E; Breitling R Mol. Biol. Evol 2013, 30, 1218–1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Adamek M; Spohn M; Stegmann E; Ziemert N Methods Mol. Biol 2017, 1520, 23–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Shannon P; Markiel A; Ozier O; Baliga NS; Wang JT; Ramage D; Amin N; Schwikowski B; Ideker T Genome Res. 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Capon RJ Nat. Prod. Rep 2019, epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Halecker S; Surup F; Solheim H; Stadler MJ Antibiot. (Tokyo) 2018, 71, 339–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Zhao J; Brosmer JL; Tang Q; Yang Z; Houk KN; Diaconescu PL; Kwon OJ Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 9807–9810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Moore C; Gupta R; Jordt SE; Chen Y; Liedtke WB Neurosci. Bull 2018, 34, 120–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Ichihara A; Oikawa H; Hashimoto M; Sakamura S; Haraguchi T; Nagano H Agric. Biol. Chem 1983, 47, 2965–2967. [Google Scholar]

- (36).Ugai T; Minami A; Fujii R; Tanaka M; Oguri H; Gomi K; Oikawa H Chem. Commun 2015, 51, 878–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Gaucher GM; Shepherd MG Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 1968, 32, 664–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Grumbt M; Monod M; Staib P FEMS Microbiol. Lett 2011, 320, 79–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Kakule TB; Jadulco RC; Koch M; Janso JE; Barrows LR; Schmidt EW ACS Synth. Biol 2015, 4, 625–633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Gottlieb HE; Kotlyar V; Nudelman AJ Org. Chem 1997, 62, 7512–7515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Tianero MD; Kwan JC; Wyche TP; Presson AP; Koch M; Barrows LR; Bugni TS; Schmidt EW The ISME journal 2015, 9, 615–628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Peng Y; Leung Hc Fau - Yiu SM; Yiu Sm Fau - Chin FYL; Chin FY Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 1420–1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Stanke M; Diekhans M; Baertsch R; Haussler D Bioinformatics 2008, 24, 637–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Aziz RK; Bartels D; Best AA; DeJongh M; Disz T; Edwards RA; Formsma K; Gerdes S; Glass EM; Kubal M; Meyer F; Olsen GJ; Olson R; Osterman AL; Overbeek RA; McNeil LK; Paarmann D; Paczian T; Parrello B; Pusch GD; Reich C; Stevens R; Vassieva O; Vonstein V; Wilke A; Zagnitko O BMC Genomics 2008, 9, 75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Brettin T; Davis JJ; Disz T; Edwards RA; Gerdes S; Olsen GJ; Olson R; Overbeek R; Parrello B; Pusch GD; Shukla M; Thomason JA 3rd; Stevens R; Vonstein V; Wattam AR; Xia F Sci. Rep 2015, 5, 8365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Overbeek R; Olson R; Pusch GD; Olsen GJ; Davis JJ; Disz T; Edwards RA; Gerdes S; Parrello B; Shukla M; Vonstein V; Wattam AR; Xia F; Stevens R Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, D206–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Notredame C; Higgins DG; Heringa J J. Mol. Biol 2000, 302, 205–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Capella-Gutierrez S; Silla-Martinez JM; Gabaldon T Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1972–1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Chen WZ; Fan LL; Xiao HT; Zhou Y; Xiao W; Wang JT; Tang L Chinese Chem. Lett 2014, 25, 749–751. [Google Scholar]

- (50).Zhu J; Porco JA Jr. Org. Lett 2006, 8, 5169–5171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.