Abstract

Traditional GWAS have successfully detected genetic variants associated with schizophrenia. However, only a small fraction of heritability can be explained. Gene-set/pathway based methods can overcome limitations arising from single SNP-based analysis, but most of them place constraints on size which may exclude highly specific and functional sets, like macromolecules. Voltage-gated calcium (Cav) channels, belonging to macromolecules, are composed of several subunits whose encoding genes are located far away or even on different chromosomes. We combined information about such molecules with GWAS data to investigate how functional channels associated with schizophrenia. We defined a biologically meaningful SNP-set based on channel structure and performed an association study by using a validated method: SNP-set (Sequence) Kernel Association Test. We identified 8 subtypes of Cav channels significantly associated with schizophrenia from a subsample of published data (N = 56,605), including the L-type channels (Cav1.1, Cav1.2, Cav1.3), P-/Q-type Cav2.1, N-type Cav2.2, R-type Cav2.3, T-type Cav3.1 and Cav3.3. Only genes from Cav1.2 and Cav3.3 have been implicated by the largest GWAS (N = 82,315). Each subtype of Cav channels showed relatively high chip heritability, proportional to the size of its constituent gene regions. The results suggest that abnormalities of Cav channels may play an important role in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia and these channels may represent appropriate drug targets for therapeutics. Analyzing subunit-encoding genes of a macromolecule in aggregate is a complementary way to identify more genetic variants of polygenic diseases. This study offers the potential of power for discovery the biological mechanisms of schizophrenia.

Keywords: schizophrenia, channels, molecule-based GWAS, SNP-sets, SKAT

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a highly heritable complex disease (Lichtenstein et al. 2009). The biological underpinnings of schizophrenia remain an enigma, making prevention difficult and delaying development of better treatment alternatives (Van Os and Kapur 2009). Recently, advances in technology and the establishment of an international consortium, the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (PGC), have made it possible to perform genome-wide association studies (GWAS) involving more than a hundred thousand individuals. The latest study from PGC has reported 108 independent genomic regions associated with schizophrenia (Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium 2014). However, the variants identified can only explain a small fraction of the estimated heritability (Giusti-Rodríguez and Sullivan 2013; Goldstein 2009; Ripke et al. 2013; Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium 2014), and the functional consequences of these variants remain largely uncharacterized. These problems may originate from inherent limitations of the GWAS methodology: The mass univariate testing approach requires an extremely stringent significance threshold to control false positives, thus reducing power; Genetic heterogeneity further complicate interpretation in large meta-analysis; Connecting SNP markers to the causal variants they represent is not straightforward; And, robust, efficient methods for detecting interactions among genetic variants remain elusive.

Gene-based, and gene-set/pathway based methods provide promising alternatives to overcome certain limitations of GWAS (Askland et al. 2012). Typically, genetic variants within or near to a gene are aggregated and tested for associations with a disease (Liu et al. 2010). Gene-set/pathway based analyses aggregate functionally related genes, providing a potentially powerful and biologically oriented bridge between genotypes and phenotypes (Ramanan et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2010). These methods, complementary to GWAS, have several advantages: They can reduce the number of tests performed; They may reduce the impact of genetic heterogeneity across cohorts; And they can facilitate the interpretation of findings. On the other hand, they also have limitations: Genes typically work in concert with one another (Liu et al. 2010), thus gene-based methods cannot take into account the joint effect among genes; The organization of pathways is typically derived from experiments of model organisms or predicted from mathematical models so uncertainties may be present (Bauer‐Mehren et al. 2009); The mechanism of the pathways is rarely clear (Khatri et al. 2012); And most published gene-set/pathway analyses place constraints on size from ten to a few hundred genes (Ramanan et al. 2012). Restriction to pathways with more than ten genes may exclude highly specific and potentially informative functional SNP sets, like macromolecules.

A macromolecule is a very large molecule created by polymerization of multiple smaller subunits. Voltage-gated calcium (Cav) channels that belong to macromolecules, are pore-forming membrane proteins involved in diverse physiological processes including depolarization of neuronal action potentials, neurotransmitter release, neuronal excitability and intracellular signaling(Simms and Zamponi 2014). Before interesting GWAS findings emerged, they have already received considerable physiological investigations in psychiatric and neurological disorders due to their importance to brain function (Catterall 2000; Simms and Zamponi 2014). Cav channels are key mediators of calcium entry into neurons (Turner et al. 2011) and calcium signaling is involved in major molecular hypothesis of schizophrenia such as dopamine, glutamatergic and GABAergic hypothesis (Lidow 2003). In fact, calcium signaling dysfunction has been suggested as a unifying pathological mechanism in schizophrenia (Lidow 2003). Thus, Cav channels gene variants are of large interest in relationship to schizophrenia and we chose to perform the macromolecular analysis of functional Cav channels.

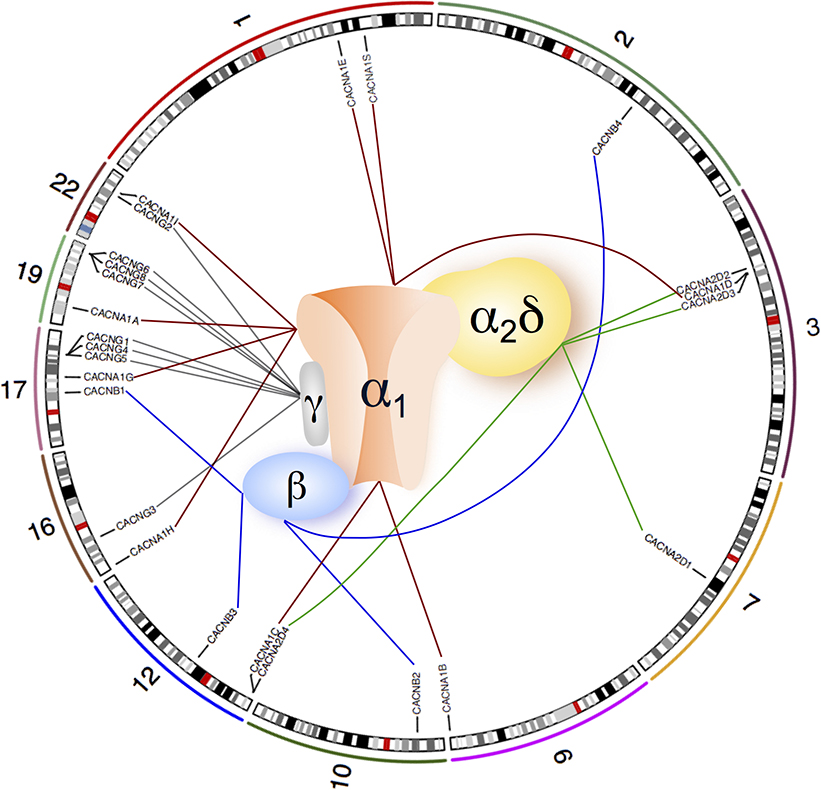

Recent GWAS have identified several associated neuronal ion channel genes (e.g. CACNA1C, CACNB2, CACNA1I, KCNB1, HCN1, CHRNA3, CHRNA5, CHRNB4) (Cross-Disorder Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium 2013; Ripke et al. 2013). In particular, associations at CACNA1C, CACNB2 and CACNA1I, which encode Cav channel subunits, extend previous findings implicating members of Cav channels in schizophrenia (Hamshere et al. 2013; Ripke et al. 2013). Cav channels can either be monomers (one subunit), or heteromultimers (three or four subunits). Although these subunits physically bind together to form a channel, their encoding genes are located in different regions of a chromosome or even on different chromosomes. For example, in the Cav1.1 channel (Bannister and Beam 2013), the α1 subunit gene CACNA1S, α2δ subunit gene CACNA2D1, β subunit gene CACNB1 and γ subunit gene CACNG1 are located at chromosomal bands 1q32, 7q21-q22, 17q21-q22 and 17q24, respectively (Fig. 1). Due to the limitations of gene-based and gene-set based analysis mentioned above, it is possible that taking the macromolecules (Cav channels) as a joint entity can explain more for the risk of schizophrenia than one single locus alone.

Fig. 1.

Molecular organization of voltage-gated calcium channels and chromosome locations of their subunit-coding genes.

Most Cav channels are multi-subunit structure (containing 3 or 4 subunits, α1, β, α2δ, with or without γ subunits), but T-type Cav channels only have the α1 subunit. In one specific channel, the subunits are physically bound together, but their encoding genes are localized far apart or even on different chromosomes. Nine autosomal genes (CACNA1A, CACNA1B, CACNA1C, CACNA1D, CACNA1E, CACNA1G, CACNA1H, CACNA1I, CACNA1S) encode α1 subunit (connected by red lines), four genes (CACNB1, CACNB2, CACNB3, CACNB4) encode β subunits (connected by blue lines), four genes (CACNA2D1, CACNA2D2, CACNA2D3, CACNA2D4) encode α2δ subunit (connected by green lines) and eight genes (CACNG1, CACNG2, CACNG3, CACNG4, CACNG5, CACNG6, CACNG7, CACNG8) encode γ subunit (connected by grey lines). The numbers 1, 2, 3, 7, 9, 10, 12, 16, 17, 19 & 22 represent chromosome numbers.

We defined a SNP set from single channel genes and investigated how this biologically functional unit is associated with schizophrenia, using the accessible PGC schizophrenia GWAS data (N = 56,605: 25,629 cases and 30,976 controls) divided into a discovery and a replication sample. We applied the SNP-set (Sequence) Kernel Association Test (SKAT) (Wu et al. 2010) and identified significant associations in eight subtypes of Cav channels (Cav1.1, Cav1.2, Cav1.3, Cav2.1, Cav2.2, Cav2.3, Cav3.1 and Cav3.3). In contrast, only genes (CACNA1C, CACNB2 and CACNA1I) from two subtypes were implicated by the original GWAS despite its larger sample (N = 82,315). These findings show the potential of the macromolecule approach to identify the possible etiology of diseases, and suggest that abnormalities of Cav channels may play an important role in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia.

Materials and Methods

Cav Genes

A total of 26 genes encoding subunits of Cav channels can be classified into 4 groups (Table 1) according to the types of subunits they encode (Catterall 2000; Simms and Zamponi 2014). Genes CACNA1A, CACNA1B, CACNA1C, CACNA1D, CACNA1E, CACNA1F, CACNA1G, CACNA1H, CACNA1I, CACNA1S encode the α1 subunits, CACNA2D1, CACNA2D2, CACNA2D3, CACNA2D4 encode the α2δ subunits, CACNB1, CACNB2, CACNB3, CACNB4 encode the β subunits and CACNG1, CACNG2, CACNG3, CACNG4, CACNG5, CACNG6, CACNG7, CACNG8 encode the γ subunits. We only analyzed genes located on the autosomes, so the gene CACNA1F on the X-chromosome was excluded.

Table 1.

Gene-level test result from discovery and validation stages.

| Gene Name | Type of Encoding Subunit | Stage1 BH_SKAT P | Stage2 BH_SKAT P | Combined dataset BH_SKATP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CACNA1A | α1A | 4.66E-01 | 3.80E-01 | 2.29E-01 |

| CACNA1B | α1B | 7.15E-01 | 1.75E-01 | 1.75E-01 |

| CACNA1C | α1C | 2.24E-04* | 2.42E-12* | 3.07E-18* |

| CACNA1D | α1D | 5.85E-01 | 7.63E-01 | 5.53E-01 |

| CACNA1E | α1E | 4.48E-01 | 7.49E-02 | 8.85E-03* |

| CACNA1G | α1G | 8.94E-03* | 1.75E-01 | 3.41E-03* |

| CACNA1H | α1H | 5.60E-01 | 8.16E-01 | 3.29E-01 |

| CACNA1I | α1I | 3.75E-04* | 2.32E-04* | 9.88E-09* |

| CACNA1S | α1S | 2.13E-01 | 2.64E-01 | 1.26E-01 |

| CACNA2D1 | α2δ1 | 5.85E-01 | 8.42E-02 | 1.26E-01 |

| CACNA2D2 | α2δ2 | 5.60E-01 | 7.49E-02 | 1.94E-01 |

| CACNA2D3 | α2δ3 | 4.48E-01 | 8.42E-02 | 8.01E-02 |

| CACNA2D4 | α2δ4 | 4.48E-01 | 1.60E-01 | 7.15E-02 |

| CACNB1 | β1 | 7.15E-01 | 1.75E-01 | 1.53E-01 |

| CACNB2 | β2 | 3.55E-02* | 6.73E-02 | 2.41E-05* |

| CACNB3 | β3 | 4.66E-01 | 1.92E-01 | 1.60E-01 |

| CACNB4 | β4 | 6.68E-01 | 1.86E-01 | 1.75E-01 |

| CACNG1 | γ1 | 6.48E-01 | 1.75E-01 | 1.53E-01 |

| CACNG2 | γ2 | 4.48E-01 | 1.75E-01 | 2.91E-01 |

| CACNG3 | γ3 | 4.66E-01 | 1.60E-01 | 1.26E-01 |

| CACNG4 | γ4 | 8.47E-01 | 7.49E-02 | 1.26E-01 |

| CACNG5 | γ5 | 4.66E-01 | 1.87E-01 | 1.26E-01 |

| CACNG6 | γ6 | 4.66E-01 | 1.75E-01 | 4.98E-01 |

| CACNG7 | γ7 | 5.75E-01 | 1.75E-01 | 1.26E-01 |

| CACNG8 | γ8 | 4.66E-01 | 2.65E-01 | 1.75E-01 |

P-value < 0.05 after correction.

Stage1: discovery phase; Stage 2: validation phase; BH: Benjamini Hochberg; SKAT: SNP-set (Sequence) kernel association test.

Genotype data

Due to IRB restrictions from some sub-studies in PGC, we used the largest accessible PGC schizophrenia data which contains 36 case-control sub-studies (N = 56,605; 25,629 cases and 30,976 controls compared to 52 sub-studies and N=82,315 in the primary study) (Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium 2014). Quality control and imputation were performed by the PGC Statistical Analysis Group for each dataset separately. Briefly, SNP meets with following conditions were retained: SNP missingness < 0.05, SNP Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium P > 1×10−6 in controls or P > 1×10−10 in cases. Samples with missing rate > 0.05 were removed. After quality control, the remaining genotypes were imputed using SHAPEIT2/IMPUTE2 (Delaneau et al. 2014; Howie et al. 2012) based on the full 1000 Genomes Project dataset (Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium 2014). To evaluate the replicability of our analysis, we selected out the data used in the first phase of PGC (PGC1) as a discovery sample (10,616 cases and 10,315 controls), and used the rest as replication sample (15,013 cases and 20,661 controls). In addition, we also used combined samples from both discovery and replication stages. We first merged the best-guessed genotype data (imputation information score > 0.8 and minor allele frequency > 0.05) across 36 sub-studies, and then, performed the second round of quality controls using parameters SNP-missingness < 0.05 and minor allele frequency > 0.05. To control the impact of population stratification on our analysis, we computed the first 20 principal components based on the merged and quality controlled genotype data by using the program EigenSoft (Price et al. 2006). Since some Cav genes are close together in genomic position (for example, CACNG6, CACNG7 and CACNG8) it is possible that some SNPs may be assigned to more than one genes. In order to avoid the such undesired bias, we annotated SNPs to the closest gene (GENCODEv1.9) based on genomic positions that were derived from the human genome assembly build hg19. Then based on the SNPs list, the genotypes of the 25 Cav genes were extracted.

Cav channels can either be monomers (only the α1 subunit), or heteromultimers (three subunits α1, β, α2δ; or four subunits α1, β, α2δ, γ). Great diversity of Cav channels allows them to fulfill highly specialized roles in specific neuronal subtypes (Simms and Zamponi 2014). Thus, for each α1 subunit (principal subunit for classifying subtypes of Cav channels), co-assembly of a variety of ancillary subunits (β, α2δ, γ) exists (Table 2). In some Cav channels, the ancillary subunit types are not completely known. So for channel-level association analysis, we test all of the possible combinations based on the current literatures (Buraei and Yang 2010; Catterall 1996; Davies et al. 2010; Hofmann et al. 2014; Schlick et al. 2010). According to different subunit gene combinations (3 or 4 genes per set), genotypes of the genes consisting of a Cav channel were concatenated. Therefore, each SNP set is corresponding to one functional channel that exists in nature.

Table 2.

Channel-level test results.

| Channel Name | Subunits Combination | Stage1 BH_SKAT P | Stage2 BH_SKAT P | Combined datasets BH_SKAT P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cav1.1 | α1S β1 α2δ1 γ1 | 4.63E-01 | 2.78E-02* | 3.54E-02* |

| Cav1.2 | α1C β1 α2δ1 | 9.56E-04* | 5.85E-12* | 1.51E-16* |

| α1C β1 α2δ2 | 5.09E-05* | 8.42E-14* | 1.62E-19* | |

| α1C β2 α2δ1 | 6.21E-05* | 8.87E-13* | 1.31E-20* | |

| α1C β2 α2δ1 γ1 | 6.21E-05* | 8.05E-13* | 1.16E-20* | |

| α1C β2 α2δ1 γ2 | 5.70E-05* | 6.13E-13* | 1.13E-20* | |

| α1C β2 α2δ1 γ3 | 6.21E-05* | 4.66E-13* | 5.56E-21* | |

| α1C β2 α2δ1 γ4 | 6.93E-05* | 6.03E-13* | 1.07E-20* | |

| α1C β2 α2δ1 γ5 | 6.21E-05* | 6.93E-13* | 6.59E-21* | |

| α1C β2 α2δ1 γ6 | 6.21E-05* | 7.04E-13* | 1.31E-20* | |

| α1C β2 α2δ1 γ7 | 6.21E-05* | 8.05E-13* | 1.13E-20* | |

| α1C β2 α2δ1 γ8 | 6.21E-05* | 8.36E-13* | 1.13E-20* | |

| α1C β2 α2δ2 | 6.66E-06* | 8.72E-14* | 1.75E-22* | |

| α1C β2 α2δ2 γ1 | 6.66E-06* | 8.42E-14* | 1.64E-22* | |

| α1C β2 α2δ2 γ2 | 6.66E-06* | 8.42E-14* | 1.61E-22* | |

| α1C β2 α2δ2 γ3 | 6.66E-06* | 8.42E-14* | 1.16E-22* | |

| α1C β2 α2δ2 γ4 | 7.22E-06* | 8.42E-14* | 1.61E-22* | |

| α1C β2 α2δ2 γ5 | 6.66E-06* | 8.42E-14* | 1.16E-22* | |

| α1C β2 α2δ2 γ6 | 6.66E-06* | 8.42E-14* | 1.64E-22* | |

| α1C β2 α2δ2 γ7 | 6.66E-06* | 8.42E-14* | 1.61E-22* | |

| α1C β2 α2δ2 γ8 | 6.66E-06* | 8.42E-14* | 1.61E-22* | |

| α1C β2 α2δ3 | 3.72E-05* | 2.65E-12* | 2.67E-20* | |

| α1C β2 α2δ4 | 6.66E-06* | 1.49E-13* | 1.16E-22* | |

| α1C β3 α2δ1 | 9.49E-04* | 5.85E-12* | 1.51E-16* | |

| α1C β3 α2δ2 | 5.09E-05* | 8.42E-14* | 1.62E-19* | |

| α1C β4 α2δ1 | 3.50E-03* | 7.39E-11* | 8.50E-15* | |

| α1C β4 α2δ2 | 7.72E-04* | 4.67E-11* | 6.26E-15* | |

| Cav1.3 | α1D β3 α2δ1 | 5.71E-01 | 6.08E-02 | 8.46E-02 |

| α1D β3 α2δ2 | 5.71E-01 | 1.85E-01 | 3.93E-01 | |

| α1D β3 α2δ3 | 3.17E-01 | 5.79E-02 | 4.26E-02* | |

| α1D β3 α2δ4 | 4.39E-01 | 3.18E-01 | 1.21E-01 | |

| α1D β4 α2δ1 | 6.41E-01 | 4.63E-02* | 6.17E-02 | |

| α1D β4 α2δ2 | 6.78E-01 | 1.22E-01 | 2.00E-01 | |

| α1D β4 α2δ3 | 4.07E-01 | 4.36E-02* | 3.54E-02* | |

| α1D β4 α2δ4 | 5.71E-01 | 1.72E-01 | 9.55E-02 | |

| Cav2.1 | α1A β1 α2δ1 | 4.99E-01 | 4.00E-02* | 4.42E-02* |

| α1A β4 α2δ1 | 5.71E-01 | 3.28E-02* | 3.72E-02* | |

| α1A β4 α2δ2 | 5.71E-01 | 7.90E-02 | 1.02E-01 | |

| α1A β4 α2δ3 | 3.49E-01 | 3.27E-02* | 2.13E-02* | |

| α1A β4 α2δ4 | 4.69E-01 | 1.13E-01 | 4.99E-02* | |

| Cav2.2 | α1B β1 α2δ1 | 6.41E-01 | 2.34E-02* | 3.92E-02* |

| α1B β1 α2δ2 | 7.14E-01 | 3.28E-02* | 1.02E-01 | |

| α1B β1 α2δ3 | 3.58E-01 | 2.34E-02* | 2.16E-02* | |

| α1B β3 α2δ1 | 6.41E-01 | 2.34E-02* | 3.92E-02* | |

| α1B β3 α2δ2 | 6.92E-01 | 3.28E-02* | 1.02E-01 | |

| α1B β3 α2δ3 | 3.58E-01 | 2.34E-02* | 2.16E-02* | |

| α1B β4 α2δ1 | 6.90E-01 | 2.15E-02* | 3.51E-02* | |

| α1B β4 α2δ2 | 7.66E-01 | 3.97E-02* | 8.89E-02 | |

| α1B β4 α2δ3 | 4.37E-01 | 2.15E-02* | 1.92E-02* | |

| Cav2.3 | α1E β1 α2δ1 | 4.25E-01 | 5.15E-03* | 1.47E-03* |

| α1E β2 α2δ1 | 4.53E-02* | 4.25E-04* | 2.30E-07* | |

| α1E β3 α2δ1 | 4.25E-01 | 5.15E-03* | 1.47E-03* | |

| α1E β4 α2δ1 | 4.82E-01 | 5.15E-03* | 1.56E-03* | |

| Cav3.1 | α1G | 2.23E-03* | 1.28E-01 | 1.05E-03* |

| Cav3.2 | α1H | 4.82E-01 | 8.16E-01 | 3.08E-01 |

| Cav3.3 | α1I | 7.31E-05* | 3.85E-05* | 1.64E-09* |

P-value < 0.05 after corrections.

Stage1: discovery phase; Stage 2: validation phase; BH: Benjamini Hochberg; SKAT: sequencing kernel association test.

SNP-set (Sequence) Kernel Association Test (SKAT)

SKAT was used to test for association between a set of genetic variants and dichotomous or quantitative phenotypes. It uses the logistic kernel-machine regression modeling framework. SKAT aggregates individual score test statistics of SNPs in a SNP set and computes SNP-set level P-values. SKAT can be used for common or/and rare variants (Ionita-Laza et al. 2013; Wu et al. 2010; Wu et al. 2011). In the current study, we focus on the common variants in line with the PGC schizophrenia study and used SKAT version 1.07 (Wu et al. 2010). The linear kernel with beta (p, 1.25), where p is the minor allele frequency of a SNP, was used. In our analysis, we carefully selected the cohort indicators and the first six principal components as covariates after comparing results including different number of principal components (three, six and ten) (Supplementary Table S1). At the same time, to overcome the issue of the large number of degrees of freedom, SKAT employs a test that adaptively estimates the degrees of freedom by accounting for correlation (LD) among the SNPs (Wu et al. 2010). In this study, a SNP set can be a collection of SNPs from a gene or several genes consisting of a heteromeric channel. The Benjamini Hochberg (BH) procedure was used to correct for multiple comparisons both in the Table 1 and Table 2 (Hochberg and Benjamini 1990; Wu et al. 2011).

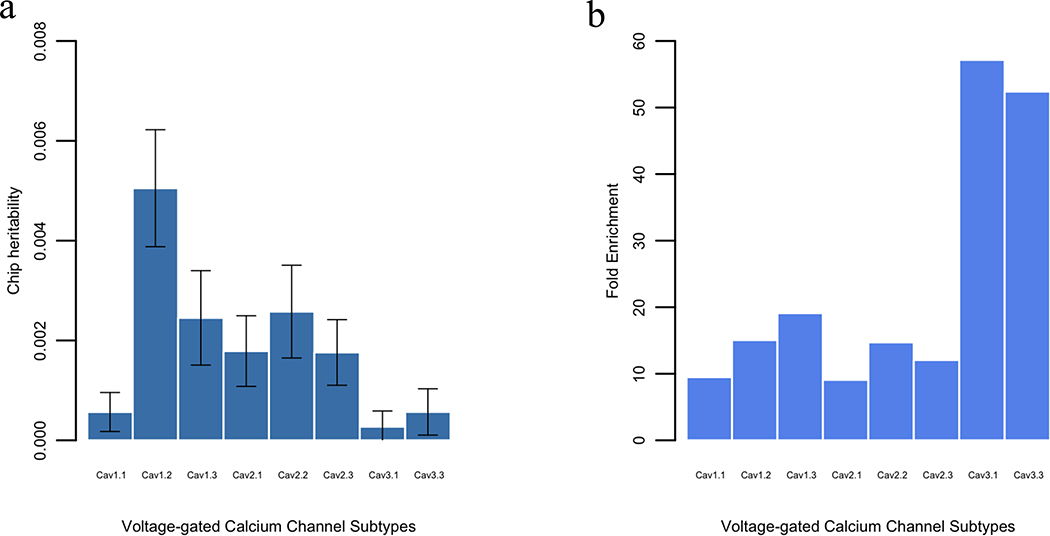

Estimate schizophrenia heritability contributed by Cav Channels SNPs

Channels significantly associated with schizophrenia (Table 2) were selected. For each subtype of Cav channel, all of the auxiliary subunit (β, α2δ, γ) genes contributing to a significant association with schizophrenia were grouped with each α1 gene. The following gene lists Cav1.1 (CACNA1S, CACNA2D1, CACNB1, CACNG1), Cav1.2 (CACNA1C, CACNA2D1, CACNA2D2, CACNA2D3, CACNA2D4, CACNB1, CACNB2, CACNB3, CACNB4, CACNG1, CACNG2, CACNG3, CACNG4, CACNG5, CACNG6, CACNG7, CACNG8), Cav1.3 (CACNA1D, CACNA2D3, CACNB3, CACNB4), Cav2.1 (CACNA1A, CACNA2D1, CACNA2D3, CACNA2D4, CACNB1, CACNB4), Cav2.2 (CACNA1B, CACNA2D1, CACNA2D3, CACNB1, CACNB3, CACNB4), Cav2.3 (CACNA1E, CACNA2D1, CACNB1, CACNB2, CACNB3, CACNB4), Cav3.1 (CACNA1G), Cav3.3 (CACNA1I) were used to extract genotype-phenotype data for estimating chip heritability by using the linear mixed method BOLT-REML (Loh et al. 2015). The level of enrichment for association with schizophrenia was represented by the ratio of proportion of chip heritability (from each subtype of channel) in total heritability (33%) (Ripke et al. 2013) to the proportion of their SNPs in all SNPs (9423850 variants, minor allele frequency > 0.05) from the 1000 Genomes Project.

Results

Association of Cav genes with schizophrenia (gene level)

Two genes, CACNA1C and CACNA1I significantly associate with schizophrenia in the discovery cohort (corrected P < 0.05) and in the replication cohort (corrected P < 0.05) both according to the SNP-set (Sequence) Kernel Association Test (SKAT) method (Table 1) and univariate analysis (Supplementary Table S2). Within the combined sample (56,605 subjects) a further three genes were identified by the SKAT analysis: CACNA1E, CACNA1G and CACNB2. CACNA1C, CACNA1I and CACNB2 were previously reported, while CACNA1E and CACNA1G have not been reported as schizophrenia candidates (Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium 2014).

Association of Cav channels with schizophrenia (macromolecule level)

Macromolecule-level testing in the discovery cohort identified heteromers Cav1.2 (all possible subunits combinations), Cav2.3 (α1E β2 α2δ1), and monomers Cav3.1 (α1G) and Cav3.3 (α1I) as associated (corrected P < 0.05). All of them except Cav3.1 (α1G) were replicated in the separate samples by SKAT analysis (Table 2). In the combined sample, heteromers Cav1.1 (α1S β1 α2δ1 γ1), Cav1.2 (all possible subunits combinations), Cav1.3 (α1D β3 α2δ3, α1D β4 α2δ3), Cav2.1 (α1A β1 α2δ1, α1A β4 α2δ1, α1A β4 α2δ3, α1A β4 α2δ4), Cav2.2 (α1B β1 α2δ1, α1B β1 α2δ3, α1B β3 α2δ1, α1B β3 α2δ3, α1B β4 α2δ1, α1B β4 α2δ3), and Cav2.3 (α1E β1 α2δ1, α1E β2 α2δ1, α1E β3 α2δ1, α1E β4 α2δ1), and monomers Cav3.1 (α1G) and Cav3.3 (α1I) associate with the risk of schizophrenia (corrected P < 0.05) (Table 2).

Chip heritability of Cav channels

We estimate that 0.0567% (s.e. 0.0391%), 0.5051% (s.e. 0.1172%), 0.2453% (s.e. 0.0946%), 0.1788% (s.e. 0.0708%), 0.2578% (s.e. 0.0929%), 0.176% (s.e. 0.0658%), 0.0272% (s.e. 0.0316%) and 0.0569% (s.e. 0.0464%) of the variance in schizophrenia can be explained by Cav1.1, Cav1.2, Cav1.3, Cav2.1, Cav2.2, Cav2.3, Cav3.1 and Cav3.3 SNPs respectively (Fig. 2a). The Cav1.2 account for the largest amount of chip heritability (0.5051%, s.e. 0.1172%) and the Cav3.1 account for the least (0.0272%, s.e. 0.0316%). However, after accounting for the number of SNPs included in each Cav subtype, Cav3.1 and Cav3.3 show largest fold enrichment (39.83 and 36.51, respectively) (Fig. 2b). All tested subtypes of Cav channels show > 6-fold enrichment. The variance explained by each subtype of Cav channels is proportional to its number of SNPs (Supplementary Fig. S1). This is in line with the previous discovery that the larger the genomic region, the higher the proportion of chip heritability that can be accounted for (Yang et al. 2011).

Fig. 2.

Estimates of the schizophrenia variance explained by SNPs from each subtype of Cav channels. (a) Chip heritability of each significant subtype of Cav channel, (b) Fold enrichment of each significant subtype of Cav channel in schizophrenia. The fold enrichment is the ratio of the proportion of chip heritability (from each significant subtype of channel) in total heritability (33%) to the proportion of their SNPs in all SNPs (9,423,850 variants, minor allele frequency > 0.05) from 1000 Genomes Projects.

Robustness of the channel-based association

Cav channels that are significantly associated with schizophrenia reported by SKAT were also identified by another program MAGMA (de Leeuw et al. 2015) (Supplementary Table S5). However, MAGMA identified fewer channels at the discovery stage compared with SKAT (Table 2; Supplementary Table S5). But for the largest European dataset (49 sub-studies), MAGMA reports similar results with SKAT.

Discussion

In the current study we applied a macromolecule approach to a subsample of published schizophrenia GWAS (N = 56,605) and identified eight subtypes of Cav channels associated with schizophrenia, including the L-type Cav channels (Cav1.1, Cav1.2, Cav1.3), P-/Q-type Cav2.1, N-type Cav2.2, R-type Cav2.3, T-type channels (Cav3.1, Cav3.3). Only genes (CACNA1C, CACNB2 and CACNA1I) from Cav1.2 and Cav3.3 were implicated in the primary PGC analysis, which was based on a larger sample (N = 82,315) (Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium 2014). In addition, we used another published statistical tool MAGMA to confirm our analysis. The results are highly consistent although the two programs are based on different assumptions and statistical models. It demonstrates that analyzing macromolecule subunit genes in aggregate is a complementary way to identify more genetic variants of schizophrenia compare to the traditional GWAS that treating each SNP separately.

The macromolecule subunits physically bind together to achieve their cellular functions, thus perturbations of any of their subunits may contribute to disease pathogenesis. In previous GWAS of schizophrenia, only a handful of channel subunits were implicated, perhaps due to the limited power of the massive univariate tests (Lichtenstein et al. 2009; Ripke et al. 2013; Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium 2014). To the best of our knowledge, only Askland and coworkers (Askland et al. 2012) have performed an association analysis of ion channels with schizophrenia, but the gene-sets defined in their study is a mixture of subunit-encoding genes from many ionic species and does not therefore correspond to a macromolecule existing in nature. In addition, it was tested in a much smaller sample. In order to test whether each functional Cav channel is associated with schizophrenia or not, we composed specific gene-set based on molecular structures of Cav channels (Buraei and Yang 2010; Catterall 1996; Davies et al. 2010; Schlick et al. 2010; Simms and Zamponi 2014). For each channel (macromolecule-based analysis), although the containing genes locate far away or even on different chromosomes, the encoding subunits are physically binding together in one functional unit to deal with flow of calcium ions. This macromolecule-based approach is different from grouping genes based on their functional catalogs or pathways since their products (proteins) interact directly or indirectly and they could not form a unique functional macromolecule. Our approach combining biological priors with GWAS data identified eight subtypes of Cav channels associated with the risk of schizophrenia. It is possible that the associations of whole channels with schizophrenia may be due to a highly associated component gene. This is likely the case for Cav1.2, where a few possible subunit combinations (for example, Cav1.2: α1C β1 α2δ2 that encoded by genes CACNA1C, CACNB1 and CACNA2D2) show their significance thanks to the α1 subunit gene CACNA1C (Table 1; Supplementary Table S7) although most of the others are not. The significant associations of the other heteromultimeric channels may be not due to a single significant gene. For example, during the discovery and replication stages, the Cav2.3 channel (subunits encoded by CACNA1E, CACNB2 and CACNA2D1) was discovered and replicated by SKAT but none of their composing genes was identified at the gene-level test. The univariate analysis (minP SNP represents channel) could not identify this channel in small samples (discovery and replication stages), but the combined sample could confirm this finding when applying a macromolecule-based approach (Supplementary Table S3). None of the channels Cav1.1, Cav1.3, Cav2.1 and Cav2.2 subunit genes was identified in gene-level testing, but the channels show significant association with schizophrenia in the combined sample. These results indicate that subunit genes can collectively associate with disease susceptibility, even if individual genes do not exhibit significant association. It seems that analyzing channel SNPs as a set can capture the joint effect of multiple variants located on different chromosomes. Thus, genetic variants with weak or moderate effects could be identified when we combined them together based on biological knowledge of the macromolecule.

We also observed enrichment of heritability in significant Cav channels SNPs for schizophrenia and it may point to a major role of the inherited genetic variants in the risk of schizophrenia. These eight subtypes of Cav channels may provide more knowledge about the pathology of schizophrenia. Cav channels are the primary mediators of depolarization-induced calcium entry into neurons (Simms and Zamponi 2014). Calcium-dependent processes such as neurotransmitter release, neuronal gene transcription, and activation of calcium-dependent enzymes are of critical importance to brain function (Clapham 2007; Simms and Zamponi 2014). L-type Cav channels (Cav1.1, Cav1.2, Cav1.3) are involved in learning, memory and synaptic plasticity (Moosmang et al. 2005; White et al. 2008; Woodside et al. 2004). Mutations in CACNA1C, the gene encoding the α1 subunit of Cav1.2, are responsible for Timothy syndrome, a multisystem disorder including cognitive impairment and autism spectrum disorder (Splawski et al. 2005; Splawski et al. 2004). SNPs located in CACNA1C are linked to development of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and depression (Dao et al. 2010; Green et al. 2010; He et al. 2014). Data from mice and humans suggest an involvement of Cav1.3 channels in neurophysiological functions, in particular in the dopaminergic system (Simms and Zamponi 2014), which is involved in the pathology of schizophrenia (Brisch et al. 2014). Although, in humans, mutations in Cav1.1 have been linked to hypokalemic periodic paralysis (Ptáček et al. 1994) and malignant hyperthermia (Monnier et al. 1997), a pathway analysis for a set of calcium channel genes implicated CACNA1S (Cav1.1 channel α1 subunit gene) as one of the 20 gene regions associated in the five psychiatric disorder meta-analysis (Cross-Disorder Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium 2013). P-/Q-type channel Cav2.1 and N-type channel Cav2.2 play a role in neurotransmitter release at the presynaptic terminal and in neuronal integration in many neuronal types (Williams et al. 1992). R-type channel Cav2.3 are strongly expressed in cortex, hippocampus, striatum, amygdala and interpeduncular nucleus (Parajuli et al. 2012). The T-type channels (Cav3.1, Cav3.3) appear to play important roles in regulating neuronal excitability (Simms and Zamponi 2014). Although there is no direct evidence associating Cav2.1, Cav2.2, Cav2.3 and Cav3.1 with schizophrenia, due to their strong expression and wide distribution in the human brain, these four subtypes of Cav channels are likely involved in some aspects of schizophrenia pathology. A recent study of rare variants in schizophrenia demonstrated that a gene set containing 26 Cav genes yielded a large odds ratio of 8.4 (Purcell et al. 2014). Given the central role of Cav channels in regulating neurotransmitter release and neuronal gene transcription, the identified channels may represent convenient drug targets for novel therapeutics. Designing drugs for specific channels by targeting α1 subunit, or designing more universal drugs for some channels by targeting shared ancillary subunits can improve efficiency of treatments. There are some Cav channels blockers in clinical use. A few L-type Cav channel antagonists such as verapamil and nifedipine which are used for hypertension, have been examined in clinical trials in schizophrenia (Lencz and Malhotra 2015). Revisiting the effect of existing agents on Cav channels or designing new drugs could be a high priority for new schizophrenia treatment development.

The genetic association test of macromolecules may also suggest candidates for non-additive interactions (epistasis) and improve polygenic predictions. In addition, while we only considered Cav channels, future work could consider other types of channels, such as potassium channels, sodium channels, and proton channels as interesting susceptibility candidates for schizophrenia and other psychiatric disorders.

The present findings illustrate the power of the macromolecule-based approach applied to schizophrenia, which identified eight subtypes of Cav channels associated with the disorder. The results highlight the combined role of different aspects of calcium signaling in schizophrenia pathophysiology, and suggest several new potential drug targets for development of novel therapeutics.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the EU funding (PsychDPC); Research Council of Norway [RCN #223273, #251134]; South East Norway Regional Health Authority; and KG Jebsen Foundation [SKGJ-MED-008].

Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium

Stephan Ripke1,2, Benjamin M. Neale1,2,3,4, Aiden Corvin5, James T. R. Walters6, Kai-How Farh1, Peter A. Holmans6,7, Phil Lee1,2,4, Brendan Bulik-Sullivan1,2, David A. Collier8,9, Hailiang Huang1,3, Tune H. Pers3,10,11, Ingrid Agartz12,13,14, Esben Agerbo15,16,17, Margot Albus18, Madeline Alexander19, Farooq Amin20,21, Silviu A. Bacanu22, Martin Begemann23, Richard A Belliveau Jr2, Judit Bene24,25, Sarah E. Bergen 2,26, Elizabeth Bevilacqua2, Tim B Bigdeli 22, Donald W. Black27, Richard Bruggeman28, Nancy G. Buccola29, Randy L. Buckner30,31,32, William Byerley33, Wiepke Cahn34, Guiqing Cai35,36, Murray J. Cairns39,120,170, Dominique Campion37, Rita M. Cantor38, Vaughan J. Carr39,40, Noa Carrera6, Stanley V. Catts39,41, Kimberly D. Chambert2, Raymond C. K. Chan42, Ronald Y. L. Chen43, Eric Y. H. Chen43,44, Wei Cheng45, Eric F. C. Cheung46, Siow Ann Chong47, C. Robert Cloninger48, David Cohen49, Nadine Cohen50, Paul Cormican5, Nick Craddock6,7, Benedicto Crespo-Facorro210, James J. Crowley51, David Curtis52,53, Michael Davidson54, Kenneth L. Davis36, Franziska Degenhardt55,56, Jurgen Del Favero57, Lynn E. DeLisi128,129, Ditte Demontis17,58,59, Dimitris Dikeos60, Timothy Dinan61, Srdjan Djurovic14,62, Gary Donohoe5,63, Elodie Drapeau36, Jubao Duan64,65, Frank Dudbridge66, Naser Durmishi67, Peter Eichhammer68, Johan Eriksson69,70,71, Valentina Escott-Price6, Laurent Essioux72, Ayman H. Fanous73,74,75,76, Martilias S. Farrell51, Josef Frank77, Lude Franke78, Robert Freedman79, Nelson B. Freimer80, Marion Friedl81, Joseph I. Friedman36, Menachem Fromer1,2,4,82, Giulio Genovese2, Lyudmila Georgieva6, Elliot S. Gershon209, Ina Giegling81,83, Paola Giusti-Rodríguez51, Stephanie Godard84, Jacqueline I. Goldstein1,3, Vera Golimbet85, Srihari Gopal86, Jacob Gratten87, Lieuwe de Haan88, Christian Hammer23, Marian L. Hamshere6, Mark Hansen89, Thomas Hansen17,90, Vahram Haroutunian36,91,92, Annette M. Hartmann81, Frans A. Henskens39,93,94, Stefan Herms55,56,95, Joel N. Hirschhorn3,11,96, Per Hoffmann55,56,95, Andrea Hofman55,56, Mads V. Hollegaard97, David M. Hougaard97, Masashi Ikeda98, Inge Joa99, Antonio Julià100, René S. Kahn34, Luba Kalaydjieva101,102, Sena Karachanak-Yankova103, Juha Karjalainen78, David Kavanagh6, Matthew C. Keller104, Brian J. Kelly120, James L. Kennedy105,106,107, Andrey Khrunin108, Yunjung Kim51, Janis Klovins109, James A. Knowles110, Bettina Konte81, Vaidutis Kucinskas111, Zita Ausrele Kucinskiene111, Hana Kuzelova-Ptackova112, Anna K. Kähler26, Claudine Laurent19,113, Jimmy Lee Chee Keong47,114, S. Hong Lee87, Sophie E. Legge6, Bernard Lerer115, Miaoxin Li43,44,116 Tao Li117, Kung-Yee Liang118, Jeffrey Lieberman119, Svetlana Limborska108, Carmel M. Loughland39,120, Jan Lubinski121, Jouko Lönnqvist122, Milan Macek Jr112, Patrik K. E. Magnusson26, Brion S. Maher123, Wolfgang Maier124, Jacques Mallet125, Sara Marsal100, Manuel Mattheisen17,58,59,126, Morten Mattingsdal14,127, Robert W. McCarley128,129, Colm McDonald130, Andrew M. McIntosh131,132, Sandra Meier77, Carin J. Meijer88, Bela Melegh24,25, Ingrid Melle14,133, Raquelle I. Mesholam-Gately128,134, Andres Metspalu135, Patricia T. Michie39,136, Lili Milani135, Vihra Milanova137, Younes Mokrab8, Derek W. Morris5,63, Ole Mors17,58,138, Kieran C. Murphy139, Robin M. Murray140, Inez Myin-Germeys141, Bertram Müller-Myhsok142,143,144, Mari Nelis135, Igor Nenadic145, Deborah A. Nertney146, Gerald Nestadt147, Kristin K. Nicodemus148, Liene Nikitina-Zake109, Laura Nisenbaum149, Annelie Nordin150, Eadbhard O’Callaghan151, Colm O’Dushlaine2, F. Anthony O’Neill152, Sang-Yun Oh153, Ann Olincy79, Line Olsen17,90, Jim Van Os141,154, Psychosis Endophenotypes International Consortium155, Christos Pantelis39,156, George N. Papadimitriou60, Sergi Papiol23, Elena Parkhomenko36, Michele T. Pato110, Tiina Paunio157,158, Milica Pejovic-Milovancevic159, Diana O. Perkins160, Olli Pietiläinen158,161, Jonathan Pimm53, Andrew J. Pocklington6, John Powell140, Alkes Price3,162, Ann E. Pulver147, Shaun M. Purcell82, Digby Quested163, Henrik B. Rasmussen17,90, Abraham Reichenberg36, Mark A. Reimers164, Alexander L. Richards6, Joshua L. Roffman30,32, Panos Roussos82,165, Douglas M. Ruderfer6,82, Veikko Salomaa71, Alan R. Sanders64,65, Ulrich Schall39,120, Christian R. Schubert166, Thomas G. Schulze77,167, Sibylle G. Schwab168, Edward M. Scolnick2, Rodney J. Scott39,169,170, Larry J. Seidman128,134, Jianxin Shi171, Engilbert Sigurdsson172, Teimuraz Silagadze173, Jeremy M. Silverman36,174, Kang Sim47, Petr Slominsky108, Jordan W. Smoller2,4, Hon-Cheong So43, Chris C. A. Spencer175, Eli A. Stahl3,82, Hreinn Stefansson176, Stacy Steinberg176, Elisabeth Stogmann177, Richard E. Straub178, Eric Strengman179,34, Jana Strohmaier77, T. Scott Stroup119, Mythily Subramaniam47, Jaana Suvisaari122, Dragan M. Svrakic48, Jin P. Szatkiewicz51, Erik Söderman12, Srinivas Thirumalai180, Draga Toncheva103, Paul A. Tooney39,120,170, Sarah Tosato181, Juha Veijola182,183, John Waddington184, Dermot Walsh185, Dai Wang86, Qiang Wang117, Bradley T. Webb22, Mark Weiser54, Dieter B. Wildenauer186, Nigel M. Williams6, Stephanie Williams51, Stephanie H. Witt77, Aaron R. Wolen164, Emily H. M. Wong43, Brandon K. Wormley22, Jing Qin Wu39,170, Hualin Simon Xi187, Clement C. Zai105,106, Xuebin Zheng188, Fritz Zimprich177, Naomi R. Wray87, Kari Stefansson176, Peter M. Visscher87, Wellcome Trust Case-Control Consortium 2189, Rolf Adolfsson150, Ole A. Andreassen14,133, Douglas H. R. Blackwood132, Elvira Bramon190, Joseph D. Buxbaum35,36,91,191, Anders D. Børglum17,58,59,138, Sven Cichon55,56,95,192, Ariel Darvasi193, Enrico Domenici194, Hannelore Ehrenreich23, Tõnu Esko3,11,96,135, Pablo V. Gejman64,65, Michael Gill5, Hugh Gurling53, Christina M. Hultman26, Nakao Iwata98, Assen V. Jablensky39,102,186,195, Erik G. Jönsson12,14, Kenneth S. Kendler196, George Kirov6, Jo Knight105,106,107, Todd Lencz197,198,199, Douglas F. Levinson19, Qingqin S. Li86, Jianjun Liu188,200, Anil K. Malhotra197,198,199, Steven A. McCarroll2,96, Andrew McQuillin53, Jennifer L. Moran2, Preben B. Mortensen15,16,17, Bryan J. Mowry87,201, Markus M. Nöthen55,56, Roel A. Ophoff38,80,34, Michael J. Owen6,7, Aarno Palotie2,4,161, Carlos N. Pato110, Tracey L. Petryshen2,128,202, Danielle Posthuma203,204,205, Marcella Rietschel77, Brien P. Riley196, Dan Rujescu81,83, Pak C. Sham43,44,116 Pamela Sklar82,91,165, David St Clair206, Daniel R. Weinberger178,207, Jens R. Wendland166, Thomas Werge17,90,208, Mark J. Daly1,2,3, Patrick F. Sullivan26,51,160 & Michael C. O’Donovan6,7

1Analytic and Translational Genetics Unit, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts 02114, USA.

2Stanley Center for Psychiatric Research, Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02142, USA.

3Medical and Population Genetics Program, Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02142, USA.

4Psychiatric and Neurodevelopmental Genetics Unit, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts 02114, USA.

5Neuropsychiatric Genetics Research Group, Department of Psychiatry, Trinity College Dublin, Dublin 8, Ireland.

6MRC Centre for Neuropsychiatric Genetics and Genomics, Institute of Psychological Medicine and Clinical Neurosciences, School of Medicine, Cardiff University, Cardiff, CF24 4HQ, UK.

7National Centre for Mental Health, Cardiff University, Cardiff, CF24 4HQ, UK.

8Eli Lilly and Company Limited, Erl Wood Manor, Sunninghill Road, Windlesham, Surrey, GU20 6PH, UK.

9Social, Genetic and Developmental Psychiatry Centre, Institute of Psychiatry, King’s College London, London, SE5 8AF, UK.

10Center for Biological Sequence Analysis, Department of Systems Biology, Technical University of Denmark, DK-2800, Denmark.

11Division of Endocrinology and Center for Basic and Translational Obesity Research, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, 02115USA.

12Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Psychiatry Section, Karolinska Institutet, SE-17176 Stockholm, Sweden.

13Department of Psychiatry, Diakonhjemmet Hospital, 0319 Oslo, Norway.

14NORMENT, KG Jebsen Centre for Psychosis Research, Institute of Clinical Medicine, University of Oslo, 0424 Oslo, Norway.

15Centre for Integrative Register-based Research, CIRRAU, Aarhus University, DK-8210 Aarhus, Denmark.

16National Centre for Register-based Research, Aarhus University, DK-8210 Aarhus, Denmark.

17The Lundbeck Foundation Initiative for Integrative Psychiatric Research, iPSYCH, Denmark.

18State Mental Hospital, 85540 Haar, Germany.

19Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University, Stanford, California 94305, USA.

20Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Atlanta Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Atlanta, Georgia 30033, USA.

21Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Emory University, Atlanta Georgia 30322, USA.

22Virginia Institute for Psychiatric and Behavioral Genetics, Department of Psychiatry, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Virginia 23298, USA.

23Clinical Neuroscience, Max Planck Institute of Experimental Medicine, Göttingen 37075, Germany.

24Department of Medical Genetics, University of Pécs, Pécs H-7624, Hungary.

25Szentagothai Research Center, University of Pécs, Pécs H-7624, Hungary.

26Department of Medical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm SE-17177, Sweden.

27Department of Psychiatry, University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine, Iowa City, Iowa 52242, USA.

28University Medical Center Groningen, Department of Psychiatry, University of Groningen NL-9700 RB, The Netherlands.

29School of Nursing, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, New Orleans, Louisiana 70112, USA.

30Athinoula A. Martinos Center, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts 02129, USA.

31Center for Brain Science, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 02138 USA.

32Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, 02114 USA.

33Department of Psychiatry, University of California at San Francisco, San Francisco, California, 94143 USA.

34University Medical Center Utrecht, Department of Psychiatry, Rudolf Magnus Institute of Neuroscience, 3584 Utrecht, The Netherlands.

35Department of Human Genetics, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, New York 10029 USA.

36Department of Psychiatry, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, New York 10029 USA.

37Centre Hospitalier du Rouvray and INSERM U1079 Faculty of Medicine, 76301 Rouen, France.

38Department of Human Genetics, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, California 90095, USA.

39Schizophrenia Research Institute, Sydney NSW 2010, Australia.

40School of Psychiatry, University of New South Wales, Sydney NSW 2031, Australia.

41Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, University of Queensland, Brisbane, St Lucia QLD 4072, Australia.

42Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Science, Beijing 100101, China.

43Department of Psychiatry, Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China.

44State Key Laboratory for Brain and Cognitive Sciences, Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China.

45Department of Computer Science, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27514, USA.

46Castle Peak Hospital, Hong Kong, China.

47Institute of Mental Health, Singapore 539747, Singapore.

48Department of Psychiatry, Washington University, St. Louis, Missouri 63110, USA.

49Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Assistance Publique Hopitaux de Paris, Pierre and Marie Curie Faculty of Medicine and Institute for Intelligent Systems and Robotics, Paris, 75013, France.

50Blue Note Biosciences, Princeton, New Jersey 08540, USA

51Department of Genetics, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27599–7264, USA.

52Department of Psychological Medicine, Queen Mary University of London, London E1 1BB, UK.

53Molecular Psychiatry Laboratory, Division of Psychiatry, University College London, London WC1E 6JJ, UK.

54Sheba Medical Center, Tel Hashomer 52621, Israel.

55Department of Genomics, Life and Brain Center, D-53127 Bonn, Germany.

56Institute of Human Genetics, University of Bonn, D-53127 Bonn, Germany.

57Applied Molecular Genomics Unit, VIB Department of Molecular Genetics, University of Antwerp, B-2610 Antwerp, Belgium.

58Centre for Integrative Sequencing, iSEQ, Aarhus University, DK-8000 Aarhus C, Denmark.

59Department of Biomedicine, Aarhus University, DK-8000 Aarhus C, Denmark.

60First Department of Psychiatry, University of Athens Medical School, Athens 11528, Greece.

61Department of Psychiatry, University College Cork, Co. Cork, Ireland.

62Department of Medical Genetics, Oslo University Hospital, 0424 Oslo, Norway.

63Cognitive Genetics and Therapy Group, School of Psychology and Discipline of Biochemistry, National University of Ireland Galway, Co. Galway, Ireland.

64Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois 60637, USA.

65Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, NorthShore University HealthSystem, Evanston, Illinois 60201, USA.

66Department of Non-Communicable Disease Epidemiology, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London WC1E 7HT, UK.

67Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, University Clinic of Psychiatry, Skopje 1000, Republic of Macedonia.

68Department of Psychiatry, University of Regensburg, 93053 Regensburg, Germany.

69Department of General Practice, Helsinki University Central Hospital, University of Helsinki P.O. Box 20, Tukholmankatu 8 B, FI-00014, Helsinki, Finland

70Folkhälsan Research Center, Helsinki, Finland, Biomedicum Helsinki 1, Haartmaninkatu 8, FI-00290, Helsinki, Finland.

71National Institute for Health and Welfare, P.O. BOX 30, FI-00271 Helsinki, Finland.

72Translational Technologies and Bioinformatics, Pharma Research and Early Development, F. Hoffman-La Roche, CH-4070 Basel, Switzerland.

73Department of Psychiatry, Georgetown University School of Medicine, Washington DC 20057, USA.

74Department of Psychiatry, Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California 90033, USA.

75Department of Psychiatry, Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine, Richmond, Virginia 23298, USA.

76Mental Health Service Line, Washington VA Medical Center, Washington DC 20422, USA.

77Department of Genetic Epidemiology in Psychiatry, Central Institute of Mental Health, Medical Faculty Mannheim, University of Heidelberg, Heidelberg, D-68159 Mannheim, Germany.

78Department of Genetics, University of Groningen, University Medical Centre Groningen, 9700 RB Groningen, The Netherlands.

79Department of Psychiatry, University of Colorado Denver, Aurora, Colorado 80045, USA.

80Center for Neurobehavioral Genetics, Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior, University of California, Los Angeles, California 90095, USA.

81Department of Psychiatry, University of Halle, 06112 Halle, Germany.

82Division of Psychiatric Genomics, Department of Psychiatry, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, New York 10029, USA.

83Department of Psychiatry, University of Munich, 80336, Munich, Germany.

84Departments of Psychiatry and Human and Molecular Genetics, INSERM, Institut de Myologie, Hôpital de la Pitiè-Salpêtrière, Paris, 75013, France.

85Mental Health Research Centre, Russian Academy of Medical Sciences, 115522 Moscow, Russia.

86Neuroscience Therapeutic Area, Janssen Research and Development, Raritan, New Jersey 08869, USA.

87Queensland Brain Institute, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Queensland, QLD 4072, Australia.

88Academic Medical Centre University of Amsterdam, Department of Psychiatry, 1105 AZ Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

89Illumina, La Jolla, California, California 92122, USA.

90Institute of Biological Psychiatry, Mental Health Centre Sct. Hans, Mental Health Services Copenhagen, DK-4000, Denmark.

91Friedman Brain Institute, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, New York 10029, USA.

92J. J. Peters VA Medical Center, Bronx, New York, New York 10468, USA.

93Priority Research Centre for Health Behaviour, University of Newcastle, Newcastle NSW 2308, Australia.

94School of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, University of Newcastle, Newcastle NSW 2308, Australia.

95Division of Medical Genetics, Department of Biomedicine, University of Basel, Basel, CH-4058, Switzerland.

96Department of Genetics, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts 02115, USA.

97Section of Neonatal Screening and Hormones, Department of Clinical Biochemistry, Immunology and Genetics, Statens Serum Institut, Copenhagen, DK-2300, Denmark.

98Department of Psychiatry, Fujita Health University School of Medicine, Toyoake, Aichi, 470–1192, Japan.

99Regional Centre for Clinical Research in Psychosis, Department of Psychiatry, Stavanger University Hospital, 4011 Stavanger, Norway.

100Rheumatology Research Group, Vall d’Hebron Research Institute, Barcelona, 08035, Spain.

101Centre for Medical Research, The University of Western Australia, Perth, WA 6009, Australia.

102The Perkins Institute for Medical Research, The University of Western Australia, Perth, WA 6009, Australia.

103Department of Medical Genetics, Medical University, Sofia1431, Bulgaria.

104Department of Psychology, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, Colorado 80309, USA.

105Campbell Family Mental Health Research Institute, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Toronto, Ontario, M5T 1R8, Canada.

106Department of Psychiatry, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, M5T 1R8, Canada.

107Institute of Medical Science, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, M5S 1A8, Canada.

108Institute of Molecular Genetics, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow123182, Russia.

109Latvian Biomedical Research and Study Centre, Riga, LV-1067, Latvia.

110Department of Psychiatry and Zilkha Neurogenetics Institute, Keck School of Medicine at University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California 90089, USA.

111Faculty of Medicine, Vilnius University, LT-01513 Vilnius, Lithuania.

112 Department of Biology and Medical Genetics, 2nd Faculty of Medicine and University Hospital Motol, 150 06 Prague, Czech Republic.

113 Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Pierre and Marie Curie Faculty of Medicine, Paris 75013, France.

114Duke-NUS Graduate Medical School, Singapore 169857, Singapore.

115Department of Psychiatry, Hadassah-Hebrew University Medical Center, Jerusalem 91120, Israel.

116Centre for Genomic Sciences, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China.

117Mental Health Centre and Psychiatric Laboratory, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu, 610041, Sichuan, China.

118Department of Biostatistics, Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland 21205, USA.

119Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University, New York, New York 10032, USA.

120Priority Centre for Translational Neuroscience and Mental Health, University of Newcastle, Newcastle NSW 2300, Australia.

121Department of Genetics and Pathology, International Hereditary Cancer Center, Pomeranian Medical University in Szczecin, 70–453 Szczecin, Poland.

122Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services; National Institute for Health and Welfare, P.O. BOX 30, FI-00271 Helsinki, Finland

123Department of Mental Health, Bloomberg School of Public Health, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland 21205, USA.

124Department of Psychiatry, University of Bonn, D-53127 Bonn, Germany.

125Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Laboratoire de Génétique Moléculaire de la Neurotransmission et des Processus Neurodégénératifs, Hôpital de la Pitié Salpêtrière, 75013, Paris, France.

126Department of Genomics Mathematics, University of Bonn, D-53127 Bonn, Germany.

127Research Unit, Sørlandet Hospital, 4604 Kristiansand, Norway.

128Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts 02115, USA.

129VA Boston Health Care System, Brockton, Massachusetts 02301, USA.

130Department of Psychiatry, National University of Ireland Galway, Co. Galway, Ireland.

131Centre for Cognitive Ageing and Cognitive Epidemiology, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh EH16 4SB, UK.

132Division of Psychiatry, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh EH16 4SB, UK.

133Division of Mental Health and Addiction, Oslo University Hospital, 0424 Oslo, Norway.

134Massachusetts Mental Health Center Public Psychiatry Division of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts 02114, USA.

135Estonian Genome Center, University of Tartu, Tartu 50090, Estonia.

136School of Psychology, University of Newcastle, Newcastle NSW 2308, Australia.

137First Psychiatric Clinic, Medical University, Sofia 1431, Bulgaria.

138Department P, Aarhus University Hospital, DK-8240 Risskov, Denmark.

139Department of Psychiatry, Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, Dublin 2, Ireland.

140King’s College London, London SE5 8AF, UK.

141Maastricht University Medical Centre, South Limburg Mental Health Research and Teaching Network, EURON, 6229 HX Maastricht, The Netherlands.

142Institute of Translational Medicine, University of Liverpool, Liverpool L69 3BX, UK.

143Max Planck Institute of Psychiatry, 80336 Munich, Germany.

144Munich Cluster for Systems Neurology (SyNergy), 80336 Munich, Germany.

145Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Jena University Hospital, 07743 Jena, Germany.

146Department of Psychiatry, Queensland Brain Institute and Queensland Centre for Mental Health Research, University of Queensland, Brisbane, Queensland, St Lucia QLD 4072, Australia.

147Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland 21205, USA.

148Department of Psychiatry, Trinity College Dublin, Dublin 2, Ireland.

149Eli Lilly and Company, Lilly Corporate Center, Indianapolis, 46285 Indiana, USA.

150Department of Clinical Sciences, Psychiatry, Umeå University, SE-901 87 Umeå, Sweden.

151DETECT Early Intervention Service for Psychosis, Blackrock, Co. Dublin, Ireland.

152Centre for Public Health, Institute of Clinical Sciences, Queen’s University Belfast, Belfast BT12 6AB, UK.

153Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, University of California at Berkeley, Berkeley, California 94720, USA.

154Institute of Psychiatry, King’s College London, London SE5 8AF, UK.

155A list of authors and affiliations appear in the Supplementary Information.

156Melbourne Neuropsychiatry Centre, University of Melbourne & Melbourne Health, Melbourne, Vic 3053, Australia.

157Department of Psychiatry, University of Helsinki, P.O. Box 590, FI-00029 HUS, Helsinki, Finland.

158Public Health Genomics Unit, National Institute for Health and Welfare, P.O. BOX 30, FI-00271 Helsinki, Finland

159Medical Faculty, University of Belgrade, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia.

160Department of Psychiatry, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27599–7160, USA.

161Institute for Molecular Medicine Finland, FIMM, University of Helsinki, P.O. Box 20 FI-00014, Helsinki, Finland

162Department of Epidemiology, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, Massachusetts 02115, USA.

163Department of Psychiatry, University of Oxford, Oxford, OX3 7JX, UK.

164Virginia Institute for Psychiatric and Behavioral Genetics, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Virginia 23298, USA.

165Institute for Multiscale Biology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, New York 10029, USA.

166PharmaTherapeutics Clinical Research, Pfizer Worldwide Research and Development, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139, USA.

167Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, University of Gottingen, 37073 Göttingen, Germany.

168Psychiatry and Psychotherapy Clinic, University of Erlangen, 91054 Erlangen, Germany.

169Hunter New England Health Service, Newcastle NSW 2308, Australia.

170School of Biomedical Sciences and Pharmacy, University of Newcastle, Callaghan NSW 2308, Australia.

171Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, Maryland 20892, USA.

172University of Iceland, Landspitali, National University Hospital, 101 Reykjavik, Iceland.

173Department of Psychiatry and Drug Addiction, Tbilisi State Medical University (TSMU), N33, 0177 Tbilisi, Georgia.

174Research and Development, Bronx Veterans Affairs Medical Center, New York, New York 10468, USA.

175Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics, Oxford, OX3 7BN, UK.

176deCODE Genetics, 101 Reykjavik, Iceland.

177Department of Clinical Neurology, Medical University of Vienna, 1090 Wien, Austria.

178Lieber Institute for Brain Development, Baltimore, Maryland 21205, USA.

179Department of Medical Genetics, University Medical Centre Utrecht, Universiteitsweg 100, 3584 CG, Utrecht, The Netherlands.

180Berkshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust, Bracknell RG12 1BQ, UK.

181Section of Psychiatry, University of Verona, 37134 Verona, Italy.

182Department of Psychiatry, University of Oulu, P.O. BOX 5000, 90014, Finland

183University Hospital of Oulu, P.O.BOX 20, 90029 OYS, Finland.

184Molecular and Cellular Therapeutics, Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, Dublin 2, Ireland.

185Health Research Board, Dublin 2, Ireland.

186School of Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, The University of Western Australia, Perth WA6009, Australia.

187Computational Sciences CoE, Pfizer Worldwide Research and Development, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139, USA.

188Human Genetics, Genome Institute of Singapore, A*STAR, Singapore 138672, Singapore.

189A list of authors and affiliations appear in the Supplementary Information.

190University College London, London WC1E 6BT, UK.

191Department of Neuroscience, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, New York 10029, USA.

192Institute of Neuroscience and Medicine (INM-1), Research Center Juelich, 52428 Juelich, Germany.

193Department of Genetics, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 91905 Jerusalem, Israel.

194Neuroscience Discovery and Translational Area, Pharma Research and Early Development, F. Hoffman-La Roche, CH-4070 Basel, Switzerland.

195Centre for Clinical Research in Neuropsychiatry, School of Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, The University of Western Australia, Medical Research Foundation Building, Perth WA 6000, Australia.

196Virginia Institute for Psychiatric and Behavioral Genetics, Departments of Psychiatry and Human and Molecular Genetics, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Virginia 23298, USA.

197The Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, Manhasset, New York, 11030 USA.

198The Hofstra NS-LIJ School of Medicine, Hempstead, New York, 11549 USA.

199The Zucker Hillside Hospital, Glen Oaks, New York,11004 USA.

200Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health, National University of Singapore, Singapore 117597, Singapore.

201Queensland Centre for Mental Health Research, University of Queensland, Brisbane 4076, Queensland, Australia.

202Center for Human Genetic Research and Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts 02114, USA.

203Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Erasmus University Medical Centre, Rotterdam 3000, The Netherlands.

204Department of Complex Trait Genetics, Neuroscience Campus Amsterdam, VU University Medical Center Amsterdam, Amsterdam 1081, The Netherlands.

205Department of Functional Genomics, Center for Neurogenomics and Cognitive Research, Neuroscience Campus Amsterdam, VU University, Amsterdam 1081, The Netherlands.

206University of Aberdeen, Institute of Medical Sciences, Aberdeen, AB25 2ZD, UK.

207Departments of Psychiatry, Neurology, Neuroscience and Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland 21205, USA.

208Department of Clinical Medicine, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen 2200, Denmark.

209Departments of Psychiatry and Human Genetics, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois 60637, USA.

210University Hospital Marqués de Valdecilla, Instituto de Formación e Investigación Marqués de Valdecilla, University of Cantabria, E‐39008 Santander, Spain

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Compliance with ethical standards

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Data availability

Schizophrenia genotype data from the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium can be accessed by following the consortium’s data policies: https://www.med.unc.edu/pgc/shared-methods.

References

- Askland K, Read C, O’Connell C, Moore JH (2012) Ion channels and schizophrenia: a gene set-based analytic approach to GWAS data for biological hypothesis testing. Human Genet 131: 373–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannister RA, Beam KG (2013) Ca V 1.1: the atypical prototypical voltage-gated Ca 2+ channel. Biochim Biophys Acta 1828: 1587–1597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer‐Mehren A, Furlong LI, Sanz F (2009) Pathway databases and tools for their exploitation: benefits, current limitations and challenges. Mol Syst Biol 5: 290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brisch R, Saniotis A, Wolf R, Bielau H, Bernstein H-G, Steiner J, Bogerts B, Braun AK, Jankowski Z, Kumaritlake J (2014) The role of dopamine in schizophrenia from a neurobiological and evolutionary perspective: old fashioned, but still in vogue. Front psychiatry 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buraei Z, Yang J (2010) The β subunit of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Physiol Rev 90: 1461–1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall WA (1996) Molecular properties of sodium and calcium channels. J Bioenerg Biomembr 28: 219–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall WA (2000) Structure and regulation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 16: 521–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapham DE (2007) Calcium signaling. Cell 131: 1047–1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross-Disorder Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (2013) Identification of risk loci with shared effects on five major psychiatric disorders: a genome-wide analysis. Lancet 381: 1371–1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dao DT, Mahon PB, Cai X, Kovacsics CE, Blackwell RA, Arad M, Shi J, Zandi PP, O’Donnell P, Knowles JA (2010) Mood disorder susceptibility gene CACNA1C modifies mood-related behaviors in mice and interacts with sex to influence behavior in mice and diagnosis in humans. Biol Psychiatry 68: 801–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies A, Kadurin I, Alvarez-Laviada A, Douglas L, Nieto-Rostro M, Bauer CS, Pratt WS, Dolphin AC (2010) The α2δ subunits of voltage-gated calcium channels form GPI-anchored proteins, a posttranslational modification essential for function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107: 1654–1659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Leeuw CA, Mooij JM, Heskes T, Posthuma D (2015) MAGMA: generalized gene-set analysis of GWAS data. PLoS Comput Biol 11: e1004219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaneau O, Marchini J, Consortium GP (2014) Integrating sequence and array data to create an improved 1000 Genomes Project haplotype reference panel. Nat Commun 5: 3934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giusti-Rodríguez P, Sullivan PF (2013) The genomics of schizophrenia: update and implications. J Clin Investi 123: 4557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein DB (2009) Common genetic variation and human traits. N Engl J Med 360: 1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green EK, Grozeva D, Jones I, Jones L, Kirov G, Caesar S, Gordon-Smith K, Fraser C, Forty L, Russell E (2010) The bipolar disorder risk allele at CACNA1C also confers risk of recurrent major depression and of schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry 15: 1016–1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamshere ML, Walters JTR, Smith R, Richards A, Green E, Grozeva D, Jones I, Forty L, Jones L, Gordon-Smith K (2013) Genome-wide significant associations in schizophrenia to ITIH3/4, CACNA1C and SDCCAG8, and extensive replication of associations reported by the Schizophrenia PGC. Mol Psychiatry 18: 708–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He K, An Z, Wang Q, Li T, Li Z, Chen J, Li W, Wang T, Ji J, Feng G (2014) CACNA1C, schizophrenia and major depressive disorder in the Han Chinese population. Br J Psychiatry 204: 36–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochberg Y, Benjamini Y (1990) More powerful procedures for multiple significance testing. Stat Med 9: 811–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann F, Flockerzi V, Kahl S, Wegener JW (2014) L-type CaV1. 2 calcium channels: from in vitro findings to in vivo function. Physiol Rev 94: 303–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howie B, Fuchsberger C, Stephens M, Marchini J, Abecasis GR (2012) Fast and accurate genotype imputation in genome-wide association studies through pre-phasing. Nat Genet 44: 955–959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ionita-Laza I, Lee S, Makarov V, Buxbaum JD, Lin X (2013) Sequence kernel association tests for the combined effect of rare and common variants. Am J Hum Genet 92: 841–853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatri P, Sirota M, Butte AJ (2012) Ten years of pathway analysis: current approaches and outstanding challenges. PLoS Comput Biol 8: e1002375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lencz T, Malhotra A (2015) Targeting the schizophrenia genome: a fast track strategy from GWAS to clinic. Mol Psychiatry 20: 820–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein P, Yip BH, Björk C, Pawitan Y, Cannon TD, Sullivan PF, Hultman CM (2009) Common genetic determinants of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in Swedish families: a population-based study. Lancet 373: 234–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lidow MS (2003) Calcium signaling dysfunction in schizophrenia: a unifying approach. Brain Res Rev 43: 70–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu JZ, Mcrae AF, Nyholt DR, Medland SE, Wray NR, Brown KM, Hayward NK, Montgomery GW, Visscher PM, Martin NG (2010) A versatile gene-based test for genome-wide association studies. Am J Hum Genet 87: 139–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loh P-R, Bhatia G, Gusev A, Finucane HK, Bulik-Sullivan BK, Pollack SJ, de Candia TR, Lee SH, Wray NR, Kendler KS (2015) Contrasting genetic architectures of schizophrenia and other complex diseases using fast variance-components analysis. Nat Genet 47:1385–1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monnier N, Procaccio V, Stieglitz P, Lunardi J (1997) Malignant-hyperthermia susceptibility is associated with a mutation of the a1-subunit of the human dihydropyridine-sensitive L-type voltage-dependent calcium-channel receptor in skeletal muscle. Am J Hum Genet 60: 1316–1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moosmang S, Haider N, Klugbauer N, Adelsberger H, Langwieser N, Müller J, Stiess M, Marais E, Schulla V, Lacinova L (2005) Role of hippocampal Cav1. 2 Ca2+ channels in NMDA receptor-independent synaptic plasticity and spatial memory. J Neurosci 25: 9883–9892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parajuli LK, Nakajima C, Kulik A, Matsui K, Schneider T, Shigemoto R, Fukazawa Y (2012) Quantitative regional and ultrastructural localization of the CaV2. 3 subunit of R-type calcium channel in mouse brain. J Neurosci 32: 13555–13567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price AL, Patterson NJ, Plenge RM, Weinblatt ME, Shadick NA, Reich D (2006) Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet 38: 904–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ptáček LJ, Tawil R, Griggs RC, Engel AG, Layzer RB, Kwieciński H, McManis PG, Santiago L, Moore M, Fouad G (1994) Dihydropyridine receptor mutations cause hypokalemic periodic paralysis. Cell 77: 863–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell SM, Moran JL, Fromer M, Ruderfer D, Solovieff N, Roussos P, O’Dushlaine C, Chambert K, Bergen SE, Kähler A (2014) A polygenic burden of rare disruptive mutations in schizophrenia. Nature 506: 185–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramanan VK, Shen L, Moore JH, Saykin AJ (2012) Pathway analysis of genomic data: concepts, methods, and prospects for future development. Trends Genet 28: 323–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ripke S, O’Dushlaine C, Chambert K, Moran JL, Kähler AK, Akterin S, Bergen SE, Collins AL, Crowley JJ, Fromer M (2013) Genome-wide association analysis identifies 13 new risk loci for schizophrenia. Nat Genet 45: 1150–1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (2014) Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature 511: 421–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlick B, Flucher B, Obermair G (2010) Voltage-activated calcium channel expression profiles in mouse brain and cultured hippocampal neurons. Neuroscience 167: 786–798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simms BA, Zamponi GW (2014) Neuronal voltage-gated calcium channels: structure, function, and dysfunction. Neuron 82: 24–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Splawski I, Timothy KW, Decher N, Kumar P, Sachse FB, Beggs AH, Sanguinetti MC, Keating MT (2005) Severe arrhythmia disorder caused by cardiac L-type calcium channel mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102: 8089–8096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Splawski I, Timothy KW, Sharpe LM, Decher N, Kumar P, Bloise R, Napolitano C, Schwartz PJ, Joseph RM, Condouris K (2004) Ca v 1.2 calcium channel dysfunction causes a multisystem disorder including arrhythmia and autism. Cell 119: 19–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RW, Anderson D, Zamponi GW (2011) Signaling complexes of voltage-gated calcium channels. Channels 5: 440–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Os J, Kapur S (2009) Schizophrenia. Lancet 374: 635–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H (2010) Analysing biological pathways in genome-wide association studies. Nat Rev Genet 11: 843–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White JA, McKinney BC, John MC, Powers PA, Kamp TJ, Murphy GG (2008) Conditional forebrain deletion of the L-type calcium channel CaV1. 2 disrupts remote spatial memories in mice. Learn Mem 15: 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams ME, Brust PF, Feldman DH, Patthi S, Simerson S, Maroufi A, McCue AF, Velicelebi G, Ellis SB, Harpold MM (1992) Structure and functional expression of an omega-conotoxin-sensitive human N-type calcium channel. Science 257: 389–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodside B, Borroni A, Hammonds M, Teyler T (2004) NMDA receptors and voltage-dependent calcium channels mediate different aspects of acquisition and retention of a spatial memory task. Neurobiol Learn and Mem 81: 105–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu MC, Kraft P, Epstein MP, Taylor DM, Chanock SJ, Hunter DJ, Lin X (2010) Powerful SNP-set analysis for case-control genome-wide association studies. Am J Hum Genet 86: 929–942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu MC, Lee S, Cai T, Li Y, Boehnke M, Lin X (2011) Rare-variant association testing for sequencing data with the sequence kernel association test. Am J Hum Genet 89: 82–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Manolio TA, Pasquale LR, Boerwinkle E, Caporaso N, Cunningham JM, De Andrade M, Feenstra B, Feingold E, Hayes MG (2011) Genome partitioning of genetic variation for complex traits using common SNPs. Nat Genet 43: 519–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.