SUMMARY

Antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) that trigger RNase H-mediated cleavage are commonly used to knockdown transcripts for experimental or therapeutic purposes. In particular, ASOs are frequently used to functionally interrogate long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) and to discriminate lncRNA loci that produce functional RNAs from those whose activity is attributable to the act of transcription. Transcription termination is triggered by cleavage of nascent transcripts, generally during polyadenylation, resulting in degradation of the residual RNA polymerase II (Pol II)-associated RNA by XRN2 and dissociation of elongating Pol II. Here we show that ASOs act upon nascent transcripts and, consequently, induce premature transcription termination downstream of the cleavage site in an XRN2-dependent manner. Targeting the transcript 3’ end with ASOs, however, allows transcript knockdown while preserving Pol II association with the gene body. These results demonstrate that the effects of ASOs on transcription must be considered for appropriate experimental and therapeutic use of these reagents.

Graphical Abstract

eTOC blurb

Antisense oligonucleotide (ASO)-mediated transcript knockdown is commonly used to interrogate the function of long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs). Here, Lee et al. demonstrate that ASOs induce cleavage of nascent transcripts and thereby trigger premature transcription termination. Thus, these reagents cannot be used to establish an RNA-mediated function for a lncRNA locus.

INTRODUCTION

Antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) are broadly used tools that allow modulation of RNA processing, protein production, or transcript abundance in cellular and animal model systems and represent a rapidly emerging class of therapeutics for diverse diseases. ASOs exert their effects on gene expression through several different mechanisms. First, ASOs can modulate pre-mRNA splicing by binding and sterically-blocking splice sites or other sequences that regulate exon inclusion. For example, ASOs that cause exon skipping in the DMD transcript or exon inclusion in SMN2 have been approved by the FDA for treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy and spinal muscular atrophy, respectively (Havens and Hastings, 2016; Rinaldi and Wood, 2018). Second, ASOs can block ribosome association, thereby reducing protein production from the targeted mRNA (Baker et al., 1997). The most common use of ASOs, however, is to induce decay of targeted transcripts by triggering RNase H-mediated cleavage. The formation of DNA-RNA hybrids between ASOs and their targets recruits endogenous RNase H1, resulting in hydrolysis of the RNA strand of the duplex (Wu et al., 2004). ASOs that trigger target mRNA degradation are undergoing clinical testing for diverse diseases including Huntington disease, myotonic dystrophy, and familial hypercholesterolemia (Rinaldi and Wood, 2018; Stein and Castanotto, 2017). Through the incorporation of specific nucleotide modifications, ASOs can be purposefully designed to engage these various modes of target regulation.

Long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) are a class of noncoding transcripts defined simply by having a length greater than 200 nucleotides and a lack of protein-coding potential. Because of this broad definition, these RNAs represent a diverse array of functional entities (Derrien et al., 2012; Kung et al., 2013; Ulitsky and Bartel, 2013). LncRNAs are often classified into those that function to regulate local gene expression in cis or those that leave the site of transcription and perform various functions in trans (Kopp and Mendell, 2018). While demonstration of a trans-acting function for a lncRNA is experimentally straightforward since the heterologous expression of these transcripts will rescue a loss-of-function phenotype, it has proven much more challenging to establish an RNA-mediated function for lncRNA loci that regulate gene expression in cis. DNA regulatory elements such as enhancers are broadly, if not ubiquitously, transcribed (Core et al., 2014; De Santa et al., 2010; Kim et al., 2010; Li et al., 2016). Moreover, transcription or splicing of lncRNAs may influence the local chromatin state and affect RNA polymerase II (Pol II) occupancy of nearby genes (Anderson et al., 2016; Engreitz et al., 2016; Latos et al., 2012). Thus, the mere production of a lncRNA transcript is not sufficient to infer a functional role for the RNA itself. Rather, at least three possible mechanisms must be considered when dissecting the function of a cis-acting lncRNA locus: i) local gene regulation is mediated by the action of regulatory DNA elements within the lncRNA gene body whose transcription is not required for function; ii) transcription of the lncRNA locus is required for regulatory activity but the transcribed RNA itself is not functional; or iii) the lncRNA molecule performs an RNA-mediated regulatory function (Kopp and Mendell, 2018). Establishing that transcription of a lncRNA locus is necessary for function can be readily achieved by introducing sequence elements that terminate transcription using genome editing techniques (Anderson et al., 2016; Engreitz et al., 2016; Latos et al., 2012). In cases where transcription is required, knockdown of the RNA using ASOs has emerged as the most frequently used approach to assess a possible function for the lncRNA molecule itself. ASOs that trigger RNase H-mediated cleavage are very effective for lncRNA knockdown, in part due to their activity in the nucleus where many lncRNAs are predominantly localized (Derrien et al., 2012). The interpretation of these experiments could be confounded, however, if ASOs influence transcription, a possibility that has not yet been formally examined.

For the majority of eukaryotic genes, transcription termination is triggered by cleavage of the nascent transcript by the polyadenylation machinery at the polyA signal sequence (PAS) (Birse et al., 1998; Connelly and Manley, 1988; Rosonina et al., 2006; Whitelaw and Proudfoot, 1986). Nascent transcript cleavage engages the ‘torpedo mechanism’, whereby the phosphorylated 5’ end of the uncapped residual RNA still associated with elongating Pol II provides an entry point for 5’-to-3’ exonucleolytic decay by XRN2, which degrades the nascent transcript until it reaches and displaces the bound Pol II from the chromatin template (Connelly and Manley, 1988; Kim et al., 2004; Proudfoot, 2016; Rosonina et al., 2006; West et al., 2004). Interestingly, it has been reported that XRN2 promotes premature transcription termination within gene bodies, at sites of promoter proximal Pol II pausing (Brannan et al., 2012; Nojima et al., 2015). Furthermore, XRN2 promotes termination downstream of PAS-independent cleavage events (Ballarino et al., 2009; Fong et al., 2015; Wagschal et al., 2012). Therefore, the XRN2-mediated torpedo mechanism is not limited to PAS-dependent termination and can be activated by other events that cause endonucleolytic cleavage of nascent Pol II-associated transcripts.

In this study, we examined the possibility that ASO-mediated cleavage of nascent RNAs induces transcription termination by activating the torpedo mechanism, thereby confounding the interpretation of functional studies of cis-acting lncRNA loci. Nuclear run-on (NRO) experiments and analysis of nascent chromatin-associated RNA in human cells revealed efficient targeting of nascent noncoding and protein-coding transcripts by ASOs. Furthermore, chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays demonstrated that introduction of ASOs reduced Pol II occupancy downstream of the transcript cleavage site in an XRN2-dependent manner. Together, these results establish that ASO-mediated knockdown triggers premature transcription termination by initiating the torpedo mechanism. We further show that targeting the 3’ end of transcripts with ASOs allows RNA knockdown while preserving Pol II association with the distal gene body. These findings reveal important considerations for the appropriate use of ASO reagents and provide an opportunity to manipulate transcription termination for experimental and therapeutic purposes.

RESULTS

ASOs induce cleavage of nascent transcripts

To determine whether ASOs trigger degradation of nascent transcripts, we first employed the NRO assay, a classic technique for measuring nascent transcript production from a gene of interest (Smale, 2009). Locked nucleic acid (LNA) gapmer ASOs, which contain standard DNA nucleotides flanked by LNA-modified nucleotides to increase target affinity and oligonucleotide stability, were designed to target three well-characterized lncRNAs, NORAD, MALAT1 and HOTAIR, and the housekeeping protein-coding transcript PPIB (designated ASO1 in Figure S1A). These transcripts were chosen based on their variable cytoplasmic or nuclear subcellular localization and the presence or absence of introns. Following transfection of cultured cells with ASOs, nuclei were isolated under conditions in which engaged Pol II was paused. An in vitro NRO transcription reaction was then performed in the presence of ribonucleotide precursors including bromouridine-triphosphate (Br-UTP), allowing the specific recovery and quantification of BrU-labeled nascent transcripts (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. ASOs induce cleavage of nascent transcripts in isolated nuclei.

(A) Schematic of nuclear run-on (NRO) experiments. Figure adapted from (Roberts et al., 2015). (B-E) Steady-state ASO-mediated knockdown in total RNA. qRT-PCR analysis of the indicated transcripts after ASO transfection in HCT116 (B-D) or HEK293T cells (E). Transcript abundance was normalized to GAPDH and mean level in control (CTRL) ASO-transfected cells. n = 3 biological replicates (individual replicates shown as black dots). **p<0.01, calculated by two-tailed t-test. For this and all subsequent figures, bar graphs and error bars represent mean ± SEM.

(F-I) qRT-PCR analysis of nascent transcript levels in NRO experiments in HCT116 (F-H) or HEK293T cells (I). For each panel, the approximate positions of primer pairs (A,B,C) and ASO targeting site are indicated in the transcript schematic above each graph. Transcript abundance was normalized to GAPDH and mean level in control (CTRL) ASO-transfected cells. n = 3 biological replicates (individual replicates shown as black dots). ns, not significant; *p<0.05; **p<0.01; calculated by Holm-Sidak’s multiple comparison t test.

See also Figure S1.

The human colon cancer cell line HCT116 was transfected with ASOs targeting NORAD, MALAT1, or PPIB. Similar experiments were performed in HEK293T cells with an ASO targeting HOTAIR, due to the higher expression of this lncRNA in this cell line. Compared to transfection with non-targeting control ASO, introduction of gene-specific ASOs resulted in a ~60–90% reduction in steady-state abundance of each targeted transcript in transfected cells prior to nuclear isolation (Figures 1B–E). NRO assays were then performed and nascent transcripts were measured by quantitative reverse-transcriptase (qRT)-PCR using primer sets that assessed the 5’, middle, or 3’ segments of each targeted RNA. Two independent reference genes, GAPDH (Figures 1F–I) and B2M (Figures S1B–E), were used to minimize the possibility of normalization artifacts. For each assayed transcript, introduction of the cognate ASO resulted in a significant reduction in nascent transcript abundance downstream of the ASO targeting site (Figures 1F–I and S1B–E). In the case of NORAD and PPIB, nascent transcript levels upstream of the site of ASO-mediated cleavage were also significantly reduced. Thus, ASOs efficiently target nascent transcripts in isolated nuclei. Transcript fragments upstream of the ASO target site are likely released from elongating Pol II and, in the absence of a stabilizing polyA tail, degraded by the exosome (Garneau et al., 2007), whereas the 3’ fragment provides a substrate for XRN2, potentially engaging the torpedo mechanism of transcription termination.

ASOs promote cleavage of chromatin-associated nascent RNAs in intact cells

We next performed metabolic labeling experiments to ascertain whether ASOs induce degradation of nascent transcripts in intact cells. Following transfection of HCT116 or HEK293T cells with ASOs, cells were pulse-labeled with 5-ethynyl uridine (EU) for 30 minutes to allow EU incorporation into newly synthesized RNA. Chromatin-associated RNAs were then isolated, further enriching for nascent transcripts. Following cell lysis and chromatin isolation under conditions prohibiting new transcription initiation, EU-labeled RNAs were biotinylated, purified, and assayed by qRT-PCR to measure chromatin-associated nascent RNA (Figure 2A). Consistent with the results of the NRO experiments, transfection of ASOs targeting NORAD, MALAT1, PPIB, or HOTAIR resulted in a significant reduction in chromatin-associated nascent transcript levels (Figures 2B–E and S2A–D). Reduced nascent transcript abundance downstream and, in most cases, upstream of the ASO target site was observed, consistent with XRN2- and exosome-mediated decay of the endonucleolytic cleavage products, respectively. These data document that ASOs efficiently target chromatin-associated nascent RNAs derived from both noncoding and protein-coding gene loci in human cells.

Figure 2. ASOs promote cleavage of chromatin-associated nascent transcripts in intact cells.

(A) Schematic of metabolic labeling and analysis of chromatin-associated nascent transcripts. Figure adapted from (Mayer and Churchman, 2016).

(B-E) qRT-PCR analysis of chromatin-associated nascent transcripts in HCT116 (B-D) or HEK293T cells (E). For each panel, the approximate positions of primer pairs (A,B,C) and ASO targeting site are indicated in the transcript schematic above each graph. Transcript abundance was normalized to GAPDH and mean level in control (CTRL) ASO-transfected cells. n = 3 biological replicates (individual replicates shown as black dots). ns, not significant; *p<0.05; **p<0.01; calculated by Holm-Sidak’s multiple comparison t test.

See also Figure S2.

ASO-mediated knockdown triggers premature transcription termination

Next, we tested whether ASO-mediated endonucleolytic cleavage of nascent transcripts resulted in premature transcription termination. ChIP was used to monitor the occupancy of total Pol II or Pol II phosphorylated at the serine 5 residue of the C-terminal domain repeat region (P-Ser5) along the gene bodies of ASO-targeted transcripts (Figure 3A). Total and P-Ser5 Pol II was readily detectable across NORAD, MALAT1, PPIB, or HOTAIR in cells transfected with control ASO (Figures 3B–E). Following transfection with ASOs that target each respective transcript, however, a significant reduction in both total and P-Ser5 Pol II association was observed at the 3’ end of each gene body. Notably, the presence or absence of introns downstream of the ASO targeting site had little impact on the magnitude of downstream Pol II association. These results demonstrate that ASO-mediated cleavage triggers premature transcription termination downstream of the ASO targeting site.

Figure 3. ASO-mediated knockdown triggers premature transcription termination.

(A) Schematic of Pol II ChIP experiments.

(B-E) ChIP-PCR analysis of total and P-Ser5 Pol II occupancy at the indicated loci in HCT116 (B-D) or HEK293T cells (E). For each panel, the approximate positions of primer pairs (A,B,C) and ASO targeting site are indicated in the transcript schematic above each graph. The percent input signal for each sample was calculated and normalized to signal obtained using an amplicon in the GAPDH gene. Values are expressed relative to the average signal detected in control (CTRL) ASO-transfected cells. n = 3 biological replicates (individual replicates shown as black dots). ns, not significant; *p<0.05; **p<0.01; calculated by Holm-Sidak’s multiple comparison t test.

XRN2 is required for ASO-mediated premature transcription termination

We hypothesized that ASO-mediated cleavage of nascent RNAs could induce transcription termination through the torpedo mechanism due to the resultant generation of an entry point for 5’-to-3’ degradation of the residual Pol II-associated transcript by XRN2. XRN2-mediated termination is not limited to PAS-dependent cleavage and can be triggered by transcript cleavage through other mechanisms that produce a nascent transcript fragment with a phosphorylated 5’ end (Ballarino et al., 2009; Brannan et al., 2012; Fong et al., 2015; Wagschal et al., 2012). To test whether ASO-induced premature transcription termination depends upon XRN2 activity, we examined nascent transcript levels and Pol II-association of ASO-targeted genes following XRN2 depletion. Cells were first transfected with control or XRN2-targeting siRNA, and then ASOs targeting NORAD or PPIB, or a non-targeting control ASO, were introduced 48 hours later (Figure S3A). This strategy resulted in efficient depletion of XRN2 and the ASO-targeted transcripts (Figures 4A and 4D).

Figure 4. XRN2 is required for ASO-mediated premature transcription termination.

(A) qRT-PCR analysis of XRN2 (upper) and NORAD (lower) transcript levels in HCT116 cells following transfection of non-targeting control siRNA (siNT) or XRN2-targeting siRNA (siXRN2) followed by transfection with the indicated ASO. Transcript abundance was normalized to GAPDH and mean level in control siRNA and ASO-transfected cells (siNT + CTRL ASO). n = 3 biological replicates (individual replicates shown as black dots). *p<0.05, **p<0.01, calculated by two-tailed t-test.

(B) qRT-PCR analysis of chromatin-associated nascent NORAD transcripts following transfection of siRNA and ASOs. The transcript schematic above the graph shows approximate positions of primer pairs (A,B’,B,C) and ASO targeting site. Transcript abundance was normalized to GAPDH and mean level in control (CTRL) ASO-transfected cells. n = 3 biological replicates (individual replicates shown as black dots). ns, not significant; **p<0.01; calculated by Holm-Sidak’s multiple comparison t test.

(C) ChIP-PCR analysis of P-Ser5 Pol II occupancy at the NORAD locus following transfection of siRNA and ASOs. Percent input signal for each sample was calculated and normalized to signal obtained using an amplicon in the GAPDH gene. Values are expressed relative to the average signal detected in control (CTRL) ASO-transfected cells. n = 3 biological replicates (individual replicates shown as black dots). ns, not significant; **p<0.01; calculated by Holm-Sidak’s multiple comparison t test.

(D) qRT-PCR analysis of XRN2 (upper) and PPIB (lower) transcript levels in HCT116 cells following transfection of siRNAs and ASOs as described for panel (A).

(E) qRT-PCR analysis of chromatin-associated nascent PPIB transcripts following transfection of siRNA and ASOs as described for panel (B).

(F) ChIP-PCR analysis of P-Ser5 Pol II occupancy at the PPIB locus following transfection of siRNA and ASOs as described for panel (C).

See also Figure S3.

Nascent, chromatin-associated transcripts in siRNA/ASO-transfected cells were analyzed using the EU metabolic labeling approach (Figure 2A). In cells depleted of XRN2, nascent transcript abundance at the 3’ end of NORAD or PPIB was no longer significantly reduced following transfection of ASOs targeting these transcripts (Figures 4B, 4E, and S3B–C). Accordingly, analysis of P-Ser5 Pol II along the gene bodies of NORAD and PPIB using ChIP demonstrated that XRN2 depletion fully restored the association of Pol II at the 3’ end of these genes (Figures 4C and 4F). These data support the model that ASO-mediated cleavage of nascent transcripts induces the torpedo mechanism, resulting in premature transcription termination within targeted gene bodies.

Targeting the distal portion of transcripts with ASOs preserves Pol II association

The demonstration that ASOs trigger premature transcription termination downstream of the site of RNA cleavage suggested that targeting the 3’ end of a gene, proximal to the polyadenylation site, could result in transcript knockdown while preserving Pol II association with the gene body. To test this hypothesis, additional ASOs were designed to target the distal portion of the lncRNA NORAD or the protein coding gene PPIB (designated ASO2 in Figure S1A). Both proximally-targeting ASOs (ASO1) and distally-targeting ASOs (ASO2) resulted in efficient knockdown of total NORAD or PPIB transcript levels (Figures 5A–B). Metabolic labeling with EU was then used to examine the effects on chromatin-associated nascent transcript levels. In the case of NORAD, targeting either the proximal or distal segment of the transcript comparably reduced nascent transcript levels throughout the gene body (Figure 5C). For PPIB, however, the distally-targeted ASO (ASO2) only significantly reduced nascent transcript abundance downstream of its cleavage site and, overall, was much less effective at knockdown of the nascent PPIB transcript (Figure 5D). Since ASO1 and ASO2 were equally effective at reducing total PPIB transcript levels (Figure 5B), the distinct behavior of these oligos at the level of nascent RNA suggests differential availability of the ASO target sites. For example, rapid transcription elongation at the PPIB locus would limit the time available for engagement of the distal targeting site by an ASO relative to the proximal target site which would emerge from elongating Pol II earlier.

Figure 5. Distal targeting of transcripts with ASOs preserves Pol II association.

(A-B) Steady-state ASO-mediated knockdown in total RNA. qRT-PCR analysis of NORAD (A) or PPIB (B) levels after ASO transfection in HCT116 cells. For each panel, the approximate positions of primer pairs (A,B,C) and ASO targeting sites (ASO1, ASO2) are indicated in the transcript schematic above each graph. Transcript abundance was normalized to GAPDH and mean level in control (CTRL) ASO-transfected cells. n = 3 biological replicates (individual replicates shown as black dots). *p<0.05, **p<0.01, calculated by two-tailed t-test.

(C-D) qRT-PCR analysis of chromatin-associated nascent NORAD (C) or PPIB (D) transcripts in HCT116 cells after transfection with ASOs. ASO1 data from Figures 2B and 2D was re-plotted to allow direct comparison of knockdown efficiency. Transcript abundance was normalized to GAPDH and mean level in control (CTRL) ASO-transfected cells. n = 3 biological replicates (individual replicates shown as black dots). ns, not significant; *p<0.05, **p<0.01; calculated by Holm-Sidak’s multiple comparison t test.

(E-F) ChIP-PCR analysis of P-Ser5 Pol II occupancy at the NORAD (E) or PPIB (F) loci following ASO transfection. Percent input signal for each sample was calculated and normalized to signal obtained using an amplicon in the GAPDH gene. Values are expressed relative to the average signal detected in control (CTRL) ASO-transfected cells. n = 3 biological replicates (individual replicates shown as black dots). ns, not significant; *p<0.05; calculated by two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

See also Figure S1.

We next examined the effects of proximal or distal targeting of NORAD or PPIB on P-Ser5 Pol II association by ChIP. At both gene loci, P-Ser5 Pol II association with distal gene segments was preserved after transfection of 3’-targeting ASOs (Figures 5E–F). These data demonstrate that the confounding effect of premature transcription termination induced by ASO-mediated nascent-transcript cleavage may be avoided by targeting the distal segment of the gene body.

DISCUSSION

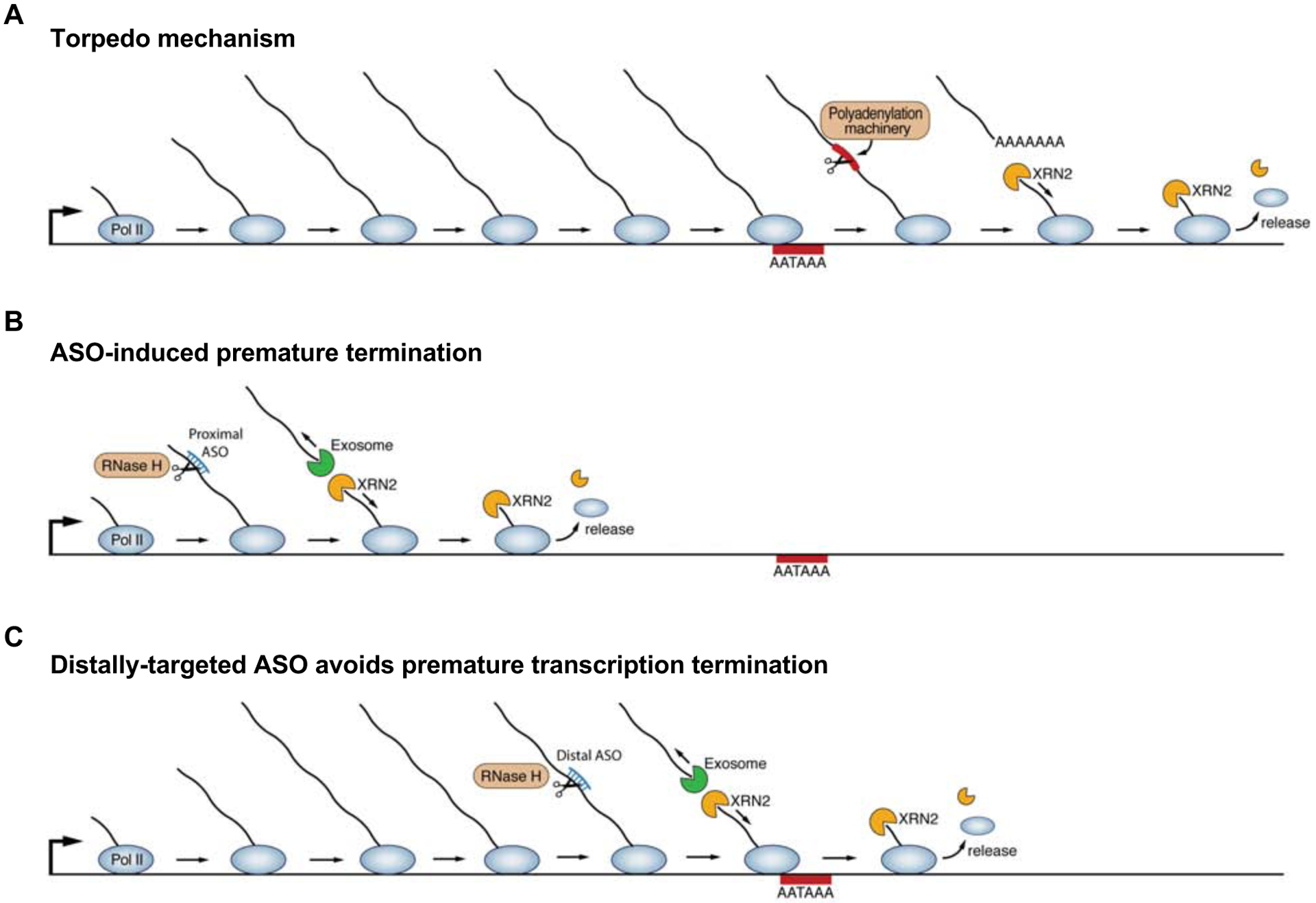

It is widely assumed that ASO-mediated RNA cleavage affects gene expression solely at the post-transcriptional level. In this study, however, we show that due to the ability of ASOs to act upon nascent transcripts, targeting an RNA of interest with this approach induces premature transcription termination, an effect which must be considered in order to appropriately interpret experiments that employ these reagents. Mechanistically, ASO-induced nascent transcript cleavage provides an entry point for degradation of the residual, uncapped Pol II-associated RNA by XRN2 in a 5’-to-3’ manner. This scenario activates the ‘torpedo mechanism’ of transcription termination, whereby XRN2 triggers dissociation of elongating Pol II when it fully degrades the residual transcript and reaches the polymerase complex (Figures 6A–B). This mechanism of transcription termination mirrors the natural termination mechanism that occurs following cleavage and polyadenylation of most Pol II transcripts.

Figure 6. Mechanism of transcription termination following cleavage and polyadenylation or ASO-mediated nascent transcript cleavage.

(A) The torpedo mechanism is activated by cleavage and polyadenylation, or other events that lead to cleavage of the nascent transcript. The resulting uncapped, phosphorylated 5’ end of the residual Pol II-associated transcript provides an entry point for the 5’-to-3’ exoribonuclease XRN2, which degrades the nascent transcript until it reaches and displaces the elongating polymerase from the chromatin template.

(B) ASO-mediated nascent transcript cleavage produces a residual Pol II-associated transcript that is an XRN2 substrate, thereby activating the torpedo mechanism in a manner analogous to the events that follow cleavage and polyadenylation.

(C) When the site of ASO cleavage is directed to the distal segment of the transcript, as close as possible to, but upstream, of the PAS, efficient transcript knockdown can still be achieved while preserving Pol II association with the distal gene body.

Our demonstration that ASOs induce premature transcription termination has important implications for the appropriate interpretation of experimental data derived from the use of these reagents. Foremost among these is the principle that ASO-mediated transcript knockdown cannot, in isolation, establish an RNA-mediated function for a transcribed locus. This tenet is perhaps most relevant for the study of lncRNAs, many of which act in cis to regulate local gene expression (Kopp and Mendell, 2018). Such cis-acting lncRNA loci have been proposed to produce RNAs that recruit chromatin modifying complexes or transcription factors and, through chromatin looping, deliver these complexes to nearby promoters. In practice, however, it can be extremely challenging to establish that these loci function through the encoded RNA. Traditional enhancers or other types of DNA regulatory elements are broadly, if not ubiquitously, transcribed (Core et al., 2014; De Santa et al., 2010; Kim et al., 2010; Li et al., 2016). Moreover, the act of transcription or splicing of a nascent transcript can itself influence expression of neighboring genes (Anderson et al., 2016; Engreitz et al., 2016; Latos et al., 2012). Thus, the production of an RNA does not necessarily imply functionality. Prior to this work, it was generally accepted that ASO-mediated knockdown could provide compelling additional data that would support an RNA-mediated function for a transcript produced by a noncoding locus. Our findings reported here, demonstrating that ASOs have an inhibitory effect on transcription, clearly show that ASO-mediated knockdown is not sufficient to support this conclusion.

Given the confounding effect of ASOs on transcription, how can one establish an RNA-mediated function for a noncoding RNA locus of interest? We have described one straightforward strategy that can potentially mitigate this issue. If the site of ASO cleavage is directed to the distal segment of the transcript, as close as possible to, but upstream, of the PAS, efficient transcript knockdown can still be achieved while preserving Pol II association with the complete gene body (Figure 6C). In some cases, distal targeting efficiently reduces nascent transcript abundance but does not provide an opportunity for premature torpedo-mediated termination because the targeting site is close to the 3’ end of the gene. Our experiments with ASO-mediated knockdown of NORAD exemplify this concept. In other cases, the distal segment of the transcript may not be available for efficient targeting at the level of nascent RNA, perhaps due to the kinetics of transcription elongation at the target locus, as exemplified by PPIB. In either case, premature transcription termination may be avoided by targeting the distal segment of the gene body, despite allowing knockdown of the total cellular levels of the transcript. Although our data suggest that these principles should be broadly applicable, direct assessment of the effect of ASO knockdown on transcription of a locus of interest, for example using Pol II ChIP, is recommended.

In addition to targeting the 3’ ends of transcripts with ASOs, it will be important in the future to evaluate whether orthogonal methods of transcript knockdown similarly act upon nascent RNAs and consequently affect transcription. In principle, any experimental strategy that induces cleavage of a nascent transcript can trigger premature transcription termination through the torpedo mechanism. RNA interference (RNAi), for example, has been reported to act both in the cytoplasm (Zeng and Cullen, 2002) and nucleus (Burger and Gullerova, 2015; Gagnon et al., 2014; Kalantari et al., 2016), suggesting that this pathway may have the ability to act upon nascent transcripts. More recently, the CRISPR/Cas13 system has been developed for targeted RNA knockdown (Abudayyeh et al., 2017; Cox et al., 2017), potentially providing an alternative approach to interrogate lncRNA activity. However, catalytically dead Cas13 orthologs from Ruminococcus flavefaciens (CasRx) are capable of targeting pre-mRNA and altering splicing (Konermann et al., 2018), suggesting that Cas13 proteins may interact with nascent transcripts. Nevertheless, this system might be useful for specifically knocking down cytoplasmic lncRNAs by, for example, appending the protein with a nuclear export signal and thereby limiting its access to the nascent RNA. A similar approach may allow engineering of Cas13 variants that are directed to subnuclear compartments distinct from the site of transcription. Finally, transcript tethering strategies could, in principle, be used to overcome the limitations of knockdown approaches and establish a cis-acting RNA-mediated lncRNA function. One could delete the genomic sequence encoding a lncRNA, or insert a transcriptional terminator, and then perform a rescue experiment in which the lncRNA, expressed in trans, is recruited to its original site of expression. CRISPR-display, a method in which long RNAs are incorporated into Cas9 guide RNAs (Shechner et al., 2015), or other well-established tethering systems such as the bacteriophage MS2 coat protein (Coller et al., 1998), could be adapted for this purpose. This strategy could potentially provide convincing evidence that a lncRNA performs an RNA-mediated function at its site of transcription that is independent of the DNA sequence from which it is encoded.

In addition to the experimental caveats revealed by our demonstration that ASOs promote transcription termination, this activity offers previously unrecognized experimental and therapeutic opportunities. For example, the purposeful induction of transcription termination by ASOs may be useful for modulating the activity of lncRNA loci whose activity is dependent upon transcription, but independent of the encoded RNA itself. Previously, this could only be accomplished by laborious genome editing strategies, such as insertion of strong polyadenylation sequences within the gene body (Anderson et al., 2016; Engreitz et al., 2016; Latos et al., 2012). ASOs can now potentially be used to more rapidly rule in or rule out a transcription-dependent activity of a noncoding locus of interest and to determine the consequences of loss-of-function of the underlying transcription-dependent sequence element. ASO-induced transcription termination could also potentially be exploited for therapeutic purposes. For example, mutations in the PAS of the HBA2 gene, which encodes α2-globin, have been described in α-thalassaemia (Higgs et al., 1983). These mutations not only impair appropriate 3’ end processing of the HBA2 message, but also cause transcriptional readthrough which interferes with transcription of the downstream HBA1 gene (encoding α1-globin) (Whitelaw and Proudfoot, 1986). The resulting deficiency of both α2-globin and α1-globin leads to a more severe α-thalassaemia phenotype than would be expected due to loss of α2-globin alone. In this scenario, therapeutic targeting of the 3’ end of the HBA2 transcript with an ASO could potentially restore transcription termination, thereby rescuing expression of HBA1 and, at least partially, ameliorating the α-thalassaemia phenotype. This example illustrates the potential therapeutic utility of inducing transcription termination using ASOs, a strategy that merits further investigation in other pathophysiologic contexts.

STAR METHODS

LEAD CONTACT AND MATERIALS AVAILABILITY

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Joshua Mendell (joshua.mendell@utsouthwestern.edu). All unique/stable reagents generated in this study are available from the Lead Contact with a completed Materials Transfer Agreement.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Human cell culture

HCT116 cells (ATCC) were cultured in McCoy’s 5A media (Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (Gibco, Sigma-Aldrich) and 1X Antibiotic-Antimycotic (Gibco). HEK293T (ATCC) cells were grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (Gibco, Sigma-Aldrich) and 1X Antibiotic-Antimycotic (Gibco). HCT116 is a male cell line and HEK293T is most likely female due to the presence of multiple X chromosomes and no detectable Y chromosome. Cell lines were confirmed to be free of mycoplasma contamination.

METHOD DETAILS

Design and transfection of oligonucleotides

All locked nucleic acid (LNA) antisense oligonucleotides used in this study were 15–16 nucleotides in length with a phosphorothioate backbone and contained central DNA nucleotides flanked by LNA nucleotides at both the 5’ and 3’ ends. ASOs were obtained from QIAGEN and designed using the QIAGEN Antisense GapmeR Designer. For each experiment, 1×106 cells were reverse-transfected with ASOs at 50 nM concentration using 5 μl of Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Transfected cells were harvested within 36 hours for analysis.

ON-TARGETplus Human XRN2 siRNA SMARTpool (Dharmacon) was used for XRN2 knockdown. 1×106 HCT116 cells were reverse-transfected with a final siRNA concentration of 40 nM using 2 μl of Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Sequences of ASOs and siRNA used in this study are provided in Table S1.

RNA extraction and qRT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cells using the QIAGEN miRNeasy Mini kit with the on-column DNase digestion step and cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA using the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis SuperMix (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturers’ instructions. SYBR Green PCR master Mix (Applied Biosystems) was used for qPCR reactions. RNA expression levels were normalized to GAPDH or B2M using the ΔΔCt method. The number of biological replicates for each experiment is described in the figure legends and three technical replicates were performed for each biological replicate. Primer sequences used for qRT-PCR are provided in Table S1.

Nuclear run-on

Nuclear run-on (NRO) was performed as previously described (Roberts et al., 2015) with minor modifications to the protocol. 2×106 cells were harvested by trypsinization, washed in cold PBS, and pelleted at 400g for 4 min at 4°C. The cell pellet was resuspended in 200 μl of cold lysis buffer (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.34 M sucrose, 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100, and 1 mM DTT) and incubated on ice for 10 min. The nuclei were pelleted at 1300g for 5 min at 4°C and washed in lysis buffer to remove residual cytoplasm. The intact nuclei were then resuspended in 40 μl of cold nuclear storage buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 0.1 mM EDTA, 5 mM MgCl2, and 40% (v/v) glycerol) and placed on ice. Transcription reactions were prepared as follows: 50 μl of 2× Transcription buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 5 mM MgCl2, 300 mM KCl, and 4 mM DTT), 2 μl RNaseOUT (40 U/μl, Invitrogen), 1 μl 100 mM BrUTP (Sigma-Aldrich), 2 μl 100 mM ATP (Roche), 2 μl 100 mM GTP (Roche), 2 μl 100 mM CTP (Roche), and 1 μl UTP 100 mM (Roche) were combined. This 60 μl reaction mixture was then added to 40 μl of nuclei in storage buffer. The reaction was mixed gently by pipetting and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. To halt the reaction, 600 μl of TRIzol LS (ThermoFisher Scientific) was added, mixed well, and incubated at room temperature for 5 min. After chloroform extraction, RNA was isolated using the miRNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN) with the on-column DNase step according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Immunoprecipitation of bromouridylated RNA was performed as follows: For each sample, 30 μl protein G Dynabeads (Invitrogen) were pre-washed in PBST (0.1% (v/v) Tween-20 in PBS) and combined with 2 μg of anti-BrdU monoclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). After incubation on a rotating platform for 10 min at room temperature, the beads were washed twice in PBSTR (PBST supplemented with 8 U/mL RNaseOUT) and resuspended in 100 μl PBSTR. 2 μg of bromouridylated RNA was denatured at 65°C for 5 min, mixed with the anti-BrdU conjugated beads, and rotated for 30 min at room temperature. Immunocomplexes were magnetically separated and washed three times with PBSTR. To harvest the RNA, 500 μl of TRIzol (Ambion) was added to the beads, mixed by pipetting, and incubated for 5 min at room temperature. 100 μl of chloroform was added, vortexed for 15 s, and incubated for 10 min at room temperature. The samples were centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. The aqueous phase was collected and transferred to a new tube. RNA was precipitated by adding 250 μl of isopropanol and 20 μg of GlycoBlue (15 mg/ml, Invitrogen). cDNA was synthesized using the SuperScript VILO cDNA synthesis kit with random primers (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Real-time PCR amplification was performed using Fast SYBR Green master mix (Life Technologies). Relative quantification of each target, normalized to an endogenous control (GAPDH or B2M), was performed using the ΔΔCt method. Primer sequences are provided in Table S1.

Metabolic labeling and analysis of nascent transcripts

Metabolically-labeled nascent transcripts were isolated as previously described (Mayer and Churchman, 2016) with minor modifications. 0.5 mM EU (Invitrogen) was added to the culture medium 30 min prior to harvesting, according to the manufacturer’s recommendation. 4×106 EU-labeled cells were harvested by trypsinization, washed in cold PBS, and pelleted at 400g for 4 min at 4°C. The cell pellet was resuspended in 400 μl of cold cytoplasmic lysis buffer (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.34 M sucrose, 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100, and 1 mM DTT) supplemented with 1× protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche), 25 μM α-amanitin (Sigma-Aldrich), and 10 U SUPERaseIn (Invitrogen) and incubated on ice for 10 min. The nuclei were pelleted at 1300g for 5 min at 4°C and washed in lysis buffer to remove residual cytoplasm. Nuclei were resuspended in 200 μl cold nuclear lysis buffer (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 3 mM EDTA, 0.2 mM EGTA, 1% (v/v) Triton X-100, and 1 mM DTT) supplemented with 0.05% SDS, 1× protease inhibitor cocktail, 25 μM α-amanitin, and 10 U SUPERaseIn and incubated on ice for 10 min. The chromatin was pelleted at 1700g for 5 min at 4°C and resuspended in 50 μl chromatin resuspension buffer (1× PBS supplemented with 1× protease inhibitor cocktail, 25 μM α-amanitin, 20 U SUPERaseIn). 700 μl of QIAzol lysis reagent was added, mixed well, and incubated at room temperature for 5 min. RNA was isolated using the miRNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN) with on-column DNase treatment according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The EU-labeled RNA was biotinylated and captured using the Click-it Nascent RNA Capture Kit (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 1 μg of EU-labeled RNA was biotinylated with 0.5 mM biotin azide in Click-iT reaction buffer. The biotinylated RNA was precipitated with ethanol and resuspended in distilled water. Click-iT RNA binding buffer supplemented with RNaseOUT was then added to the biotinylated RNA. The mixture was heated at 68°C for 5 min and added to MyOne Strepta vidin T1 Dynabeads followed by incubation at room temperature for 30 min with gentle vortexing. Beads were washed with Click-iT wash buffers 1 and 2 using magnetic separation. The washed beads were resuspended in Click-iT wash buffer 2 and directly used for cDNA synthesis using the SuperScript VILO cDNA synthesis kit with random primers (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Real-time PCR amplification was performed as described for NRO reactions.

Native chromatin immunoprecipitation

Native chromatin immunoprecipitation was performed as previously described (Skene and Henikoff, 2017) with minor modifications. 4×106 cells were harvested by trypsinization, washed in cold PBS, and pelleted at 400g for 4 min at 4°C. The cell pellet was resuspended in 500 μl of cold nuclear preparation buffer (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.34 M sucrose, 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100, and 1 mM DTT) supplemented with 1× protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and 1× PhosSTOP (Roche) and incubated on ice for 10 min. The nuclei were pelleted at 1300g for 5 min at 4°C, resuspended in 250 μl cold dilution buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1% (v/v) Triton X-100, and 1 mM DTT) supplemented with 0.05% SDS, 1× protease inhibitor cocktail, and 3 mM CaCl2 and incubated on ice for 10 min. 2.5 μl of 10× MNase (2000 U/μl, NEB) was added followed by incubation at 37°C for 4 min. The MNase reaction was stopped by adding 250 μl 2× ChIP buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl pH8.0, 20 mM EDTA, 200 mM NaCl, 2% (v/v) Triton X-100, and 0.2 % (w/v) sodium deoxycholate) supplemented with 40 mM EGTA, 1 mM DTT, and 2× protease inhibitor cocktail. Samples were centrifuged for 10 min at 15,000 rpm at 4°C. The supernatant containing soluble chromatin was collected and combined with an additional 500 μl 1× ChIP buffer. Chromatin was pre-cleared with 30 μl protein G Dynabeads (Invitrogen) for 1 h at 4°C, and then incubated overnight at 4°C with either 10 μg anti-RNA Pol II (Active motif, Clone 4H8) or 5 μg anti-Pol II P-Ser5 antibody (Active motif, Clone 3E8). Antibody-bound complexes were captured by incubation with 30 μl of protein G Dynabeads for 4 h at 4°C. Beads were washed 5 times with ChIP buffer and antibody-bound complexes were then eluted in 100 μl of Elution buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 10 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM DTT, 1% SDS, and 5 μl of proteinase K (50 mg/ml, Lucigen)) for 1 h at 55°C. 2 μl RNase A (5 mg/ml, Lucigen) was added followed by incubation for 30 min at 37°C. DNA was purified using the QIAquick PCR purification Kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and eluted in 50 μl TE buffer. Both input and immunoprecipitated DNA were quantified by real-time PCR with primers listed in Table S1.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

All experiments were repeated with a minimum of three independent biological replicates as indicated in each figure legend. Statistical significance was analyzed using Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software). The Student’s t test, Holm-Sidak’s multiple comparisons t test, or Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test were used to determine statistical significance. All values are reported as mean ± SEM in each figure.

Supplementary Material

Table S1. Nucleic acid sequences used in this study, Related to STAR Methods

Highlights.

ASOs induce cleavage of nascent transcripts

ASO-mediated cleavage of nascent RNAs induces premature transcription termination

XRN2 is required for ASO-mediated premature transcription termination

Targeting transcript 3’ end with ASOs avoids premature transcription termination

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Albert Mo for technical assistance and Rebecca Burgess and members of the Mendell laboratory for helpful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from CPRIT (RP160249 to J.T.M.), NIH (R35CA197311, P30CA142543, and P50CA196516 to J.T.M.), and the Welch Foundation (I-1961-20180324 to J.T.M.). J.T.M. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- Abudayyeh OO, Gootenberg JS, Essletzbichler P, Han S, Joung J, Belanto JJ, Verdine V, Cox DBT, Kellner MJ, Regev A, et al. (2017). RNA targeting with CRISPR-Cas13. Nature 550, 280–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson KM, Anderson DM, McAnally JR, Shelton JM, Bassel-Duby R, and Olson EN (2016). Transcription of the non-coding RNA upperhand controls Hand2 expression and heart development. Nature 539, 433–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker BF, Lot SS, Condon TP, Cheng-Flournoy S, Lesnik EA, Sasmor HM, and Bennett CF (1997). 2’-O-(2-Methoxy)ethyl-modified anti-intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) oligonucleotides selectively increase the ICAM-1 mRNA level and inhibit formation of the ICAM-1 translation initiation complex in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. J Biol Chem 272, 11994–12000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballarino M, Pagano F, Girardi E, Morlando M, Cacchiarelli D, Marchioni M, Proudfoot NJ, and Bozzoni I (2009). Coupled RNA processing and transcription of intergenic primary microRNAs. Mol Cell Biol 29, 5632–5638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birse CE, Minvielle-Sebastia L, Lee BA, Keller W, and Proudfoot NJ (1998). Coupling termination of transcription to messenger RNA maturation in yeast. Science 280, 298–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brannan K, Kim H, Erickson B, Glover-Cutter K, Kim S, Fong N, Kiemele L, Hansen K, Davis R, Lykke-Andersen J, et al. (2012). mRNA decapping factors and the exonuclease Xrn2 function in widespread premature termination of RNA polymerase II transcription. Mol Cell 46, 311–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger K, and Gullerova M (2015). Swiss army knives: non-canonical functions of nuclear Drosha and Dicer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 16, 417–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coller JM, Gray NK, and Wickens MP (1998). mRNA stabilization by poly(A) binding protein is independent of poly(A) and requires translation. Genes Dev 12, 3226–3235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connelly S, and Manley JL (1988). A functional mRNA polyadenylation signal is required for transcription termination by RNA polymerase II. Genes Dev 2, 440–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Core LJ, Martins AL, Danko CG, Waters CT, Siepel A, and Lis JT (2014). Analysis of nascent RNA identifies a unified architecture of initiation regions at mammalian promoters and enhancers. Nat Genet 46, 1311–1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox DBT, Gootenberg JS, Abudayyeh OO, Franklin B, Kellner MJ, Joung J, and Zhang F (2017). RNA editing with CRISPR-Cas13. Science 358, 1019–1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Santa F, Barozzi I, Mietton F, Ghisletti S, Polletti S, Tusi BK, Muller H, Ragoussis J, Wei CL, and Natoli G (2010). A large fraction of extragenic RNA pol II transcription sites overlap enhancers. PLoS Biol 8, e1000384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derrien T, Johnson R, Bussotti G, Tanzer A, Djebali S, Tilgner H, Guernec G, Martin D, Merkel A, Knowles DG, et al. (2012). The GENCODE v7 catalog of human long noncoding RNAs: analysis of their gene structure, evolution, and expression. Genome Res 22, 1775–1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engreitz JM, Haines JE, Perez EM, Munson G, Chen J, Kane M, McDonel PE, Guttman M, and Lander ES (2016). Local regulation of gene expression by lncRNA promoters, transcription and splicing. Nature 539, 452–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong N, Brannan K, Erickson B, Kim H, Cortazar MA, Sheridan RM, Nguyen T, Karp S, and Bentley DL (2015). Effects of Transcription Elongation Rate and Xrn2 Exonuclease Activity on RNA Polymerase II Termination Suggest Widespread Kinetic Competition. Mol Cell 60, 256–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon KT, Li L, Chu Y, Janowski BA, and Corey DR (2014). RNAi factors are present and active in human cell nuclei. Cell Rep 6, 211–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garneau NL, Wilusz J, and Wilusz CJ (2007). The highways and byways of mRNA decay. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8, 113–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havens MA, and Hastings ML (2016). Splice-switching antisense oligonucleotides as therapeutic drugs. Nucleic Acids Res 44, 6549–6563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgs DR, Goodbourn SE, Lamb J, Clegg JB, Weatherall DJ, and Proudfoot NJ (1983). Alpha-thalassaemia caused by a polyadenylation signal mutation. Nature 306, 398–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalantari R, Chiang CM, and Corey DR (2016). Regulation of mammalian transcription and splicing by Nuclear RNAi. Nucleic Acids Res 44, 524–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M, Krogan NJ, Vasiljeva L, Rando OJ, Nedea E, Greenblatt JF, and Buratowski S (2004). The yeast Rat1 exonuclease promotes transcription termination by RNA polymerase II. Nature 432, 517–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TK, Hemberg M, Gray JM, Costa AM, Bear DM, Wu J, Harmin DA, Laptewicz M, Barbara-Haley K, Kuersten S, et al. (2010). Widespread transcription at neuronal activity-regulated enhancers. Nature 465, 182–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konermann S, Lotfy P, Brideau NJ, Oki J, Shokhirev MN, and Hsu PD (2018). Transcriptome Engineering with RNA-Targeting Type VI-D CRISPR Effectors. Cell 173, 665–676 e614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp F, and Mendell JT (2018). Functional Classification and Experimental Dissection of Long Noncoding RNAs. Cell 172, 393–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kung JT, Colognori D, and Lee JT (2013). Long noncoding RNAs: past, present, and future. Genetics 193, 651–669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latos PA, Pauler FM, Koerner MV, Senergin HB, Hudson QJ, Stocsits RR, Allhoff W, Stricker SH, Klement RM, Warczok KE, et al. (2012). Airn transcriptional overlap, but not its lncRNA products, induces imprinted Igf2r silencing. Science 338, 1469–1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Notani D, and Rosenfeld MG (2016). Enhancers as non-coding RNA transcription units: recent insights and future perspectives. Nat Rev Genet 17, 207–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer A, and Churchman LS (2016). Genome-wide profiling of RNA polymerase transcription at nucleotide resolution in human cells with native elongating transcript sequencing. Nat Protoc 11, 813–833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nojima T, Gomes T, Grosso ARF, Kimura H, Dye MJ, Dhir S, Carmo-Fonseca M, and Proudfoot NJ (2015). Mammalian NET-Seq Reveals Genome-wide Nascent Transcription Coupled to RNA Processing. Cell 161, 526–540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proudfoot NJ (2016). Transcriptional termination in mammals: Stopping the RNA polymerase II juggernaut. Science 352, aad9926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinaldi C, and Wood MJA (2018). Antisense oligonucleotides: the next frontier for treatment of neurological disorders. Nat Rev Neurol 14, 9–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts TC, Hart JR, Kaikkonen MU, Weinberg MS, Vogt PK, and Morris KV (2015). Quantification of nascent transcription by bromouridine immunocapture nuclear run-on RT-qPCR. Nat Protoc 10, 1198–1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosonina E, Kaneko S, and Manley JL (2006). Terminating the transcript: breaking up is hard to do. Genes Dev 20, 1050–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shechner DM, Hacisuleyman E, Younger ST, and Rinn JL (2015). Multiplexable, locus-specific targeting of long RNAs with CRISPR-Display. Nat Methods 12, 664–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skene PJ, and Henikoff S (2017). An efficient targeted nuclease strategy for high-resolution mapping of DNA binding sites. Elife 6: e21856 DOI: 10.7554/eLife.21856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smale ST (2009). Nuclear run-on assay. Cold Spring Harb Protoc 2009, pdb prot5329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein CA, and Castanotto D (2017). FDA-Approved Oligonucleotide Therapies in 2017. Mol Ther 25, 1069–1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulitsky I, and Bartel DP (2013). lincRNAs: genomics, evolution, and mechanisms. Cell 154, 26–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagschal A, Rousset E, Basavarajaiah P, Contreras X, Harwig A, Laurent-Chabalier S, Nakamura M, Chen X, Zhang K, Meziane O, et al. (2012). Microprocessor, Setx, Xrn2, and Rrp6 co-operate to induce premature termination of transcription by RNAPII. Cell 150, 1147–1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West S, Gromak N, and Proudfoot NJ (2004). Human 5’ --> 3’ exonuclease Xrn2 promotes transcription termination at co-transcriptional cleavage sites. Nature 432, 522–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitelaw E, and Proudfoot N (1986). Alpha-thalassaemia caused by a poly(A) site mutation reveals that transcriptional termination is linked to 3’ end processing in the human alpha 2 globin gene. EMBO J 5, 2915–2922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H, Lima WF, Zhang H, Fan A, Sun H, and Crooke ST (2004). Determination of the role of the human RNase H1 in the pharmacology of DNA-like antisense drugs. J Biol Chem 279, 17181–17189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Y, and Cullen BR (2002). RNA interference in human cells is restricted to the cytoplasm. RNA 8, 855–860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Nucleic acid sequences used in this study, Related to STAR Methods