Introduction

Approximately two-thirds of diagnosed breast cancers (BrCas) in the United States are hormone-receptor positive. Endocrine therapy (ET), the recommended adjunct treatment for hormone-receptor positive BrCa, can reduce recurrence by 40% and lower the risk of dying by one third.1 Despite these survival benefits, adherence to ET is a major problem;2–13 50 to 75% of all women prescribed ET prematurely discontinue or do not maintain adherence after five years. 6,9,14–17 Even lower rates of ET adherence occur among sub-groups of financially-disadvantaged women;18 and, in some cases, are significantly lower among women who are both African American and are of low-income status.19,20 With more recent findings indicating the need to continue ET for 10 years, adherence may be even more problematic.14,21 Therefore, identifying effective interventions to improve maintenance of ET in women with BrCa is vital.17,22,23

Previous studies have extensively documented socio-demographics e.g., race, age, disease, and treatment-related factors are associated with ET adherence, and provided limited evidence about modifiable factors, e.g, psychosocial, behavioral, which can be targeted with interventions.13,24,25,26 A systematic review by Hurtado-de-Mendoza et al. (2016) confirmed that few behavioral intervention studies were conducted on improving adherence to ET therapy. Therefore, the purposes of this systematic review were to explore studies that examined the impact of interventions or strategies to improve ET adherence among women with BrCa, and identify studies offering insights for future researchers designing interventions to improve ET adherence. Given the known health disparities of BrCa survivors that may contribute to lack of ET adherence,18,27,28 we additionally sought to examine whether any studies discussed adaptations or considerations aimed to target the unique needs of disparate populations.

Methods

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria.

Studies included in this review met the following criteria: original research in peer-reviewed journals, full-text available online, clearly stated descriptions of samples and methodology, human subjects, adults, and articles available in English. We focused on papers that examined strategies and approaches for improving adherence to ET among women with BrCa. We defined ET as tamoxifen and/or aromatase inhibitors, the two major classes of drugs used for hormone positive BrCa. We included studies with a broad range of designs to capture data that examined a direct relationship between adherence and any strategy that could be replicated in an intervention. For example, if a study reported modifiable factors e.g., self-efficacy, patient-provider communication)in association with adherence as an outcome, we included the study. We excluded any descriptive manuscripts which did not document strategies to improve adherence.

Search Strategy.

Articles from 2006 to 2017 were retrieved from the following databases: PubMed, CINAHL, PsychInfo, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library. The MeSH terms and keywords included patient compliance [MeSH Terms] OR patient compliance [All Fields] OR medication adherence [MeSH Terms] OR “medication adherence”[All Fields] OR “treatment adherence”[All Fields]) AND (“breast neoplasms”[MeSH Terms] OR “breast neoplasms”[All Fields] OR “breast cancer”[All Fields]) AND (“antineoplastic agents, hormonal”[All Fields] OR “antineoplastic agents, hormonal”[MeSH Terms] OR “aromatase inhibitors”[All Fields] OR “aromatase inhibitors”[MeSH Terms] OR aromatase inhibitors[Text Word] OR “endocrine therapy”[All Fields].

Study screening.

We imported and managed all study citations identified from our search strategy with the Covidence systematic review platform 29 Two reviewers (P.H., S.H.) independently screened titles and abstracts for study eligibility, and identified studies for full-text review. Reviewers independently read the full text and selected studies for inclusion. Following this review, the two reviewers met to reach consensus on the final selection of studies to be included.

Data abstraction.

Data selected for extraction and included in Table 1 are author/date, sample size, inclusion criteria, drug type, adherence measure, design, intervention detail, results and cultural aspects. We based our risk-of-bias assessment on work by Chad-Friedman and colleagues who used a checklist adapted from STROBE recommendations30 to review studies in their systematic review.31

Table 1.

Data Extraction Table for Intervention Approaches to Adherence

| Source | Sample Size | Drug Type | Measurement | Design | Type of Manipulation | Results | Cultural Aspects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albert, 201147 | 207 | Tam & AI | Self report of medication adherence from questionnaire | retrospective descriptive | patient’s interaction with the breast care nurse | nurse navigator contact and knowledge of hormone receptor status significantly correlated (p < 0.001) | Germany |

| Arriola, 201438 | 200 | Tam & AI | MARS (4 items), Drug Attittude Inventory (6 items) higher score greater adherence | cross sectional | physician communication frequency | Frequency of physician communication was significantly associated with medication adherence (p < 0.05) | US White, 54.5% |

| Castaldi, 201746 | 117 | Tam & AI | Days to ET start using National Quality Forum 2 | non-randomized historical usual care versus navigated care | SC vs. Multi-disciplinary Patient Navigation program | SC (68.6 %) vs. navigation (100%) P < .0001) | US AA 45% Hispanic 28.5% Asian 8% white 8.5 % |

| Hadji, 201340 | Treatment (2442) / SC (2402) | AI | self-report questionnaire and percentage of patients adherent at 12 month based on prescription given | RCT | SC vs. Educational materials | SC (52.3%) vs. Educational materials (50.9% ) P = 0.37. | Germany |

| Heisig, 201543 | 137 | Tam & AI | Self-assessment question of number of tablets taken in the last 12 weeks | prospective single cohort | SC vs. enhanced education with printed materials & verbal instruction | Adherence significant for satisfaction with ET information (ρ = 0.17, OR 1.55 p = 0.03, n = 133) and associated problems (ρ = 0.22, OR 1.77, p = 0.006) | Germany |

| Jacob, 201534 | 1874 (DMP); 3041 (SC) | Tam & AI | 90 days without medication refill over 3 year period | retrospective | SC vs. disease management program | SC (39.6 %) vs. Disease Management (32.7 % ) adjusted HR = 0.91, 95 % CI: 0.85–0.98 | Germany |

| Kahn, 200742 | 881 | Tam | Self-report survey; medical record | prospective cohort | patient-centered care | Three factors, amount of support, role in decision making and pre-treatment information on side effects was significantly associated with tamoxifen adherence | US Hispanic& other 5% Non-Hispanic white 85 % Non-Hispanic other 4 % black 7 % |

| Kostev, 201335 | 3,620 | Tam | 90 days without medication refill | retrospective | conversion vs no conversion to a rebate | 44.2% of women who used a rebate process and 33.8% of patients who continued with same process discontinued their treatment (p < 0.01) after one year. | Germany |

| Lin, 201744 | 100 | Tam & AI | MARS (4 item) | cross sectional | Patient provider communicatoin | Physician communication not associated (p > .05) with adherence | USA |

| Liu, 201337 | 303 | Tam & AI | Self report 3 years post diagnosis | observational | patient-provider communication | Patient centered communication by oncologist significantly predicted adherence at 3 years post diagnosis (AOR = 1.22, P = 0.006) | US Latina 49 % White 34 % |

| Markopoulos, 2015 | 1379 per group | AI | Self report number of pills taken; number of Rx written | RCT | Educational materials versus SC | SC (82 %) vs. Education (82%) no significant difference 1 year and similar at 2 years | Lead country Belgium, International study across 18 countries |

| Neugut, 201136 | Pre-medicare 8,110; Medicare 14,050 | AI | minimum 45-day supply gap with no AI on hand and no refills | retrospective cohort | co-payment amount | 90-day co-payment ($90 or more) in younger women compared to a co-payment of $30 (OR= 0.82; 95% CI, 0.72 to 0.94). Older women had similar negative findings regarding the co-payment amounts of $30 or more compared with co-payment amounts of less than $30 OR= 0.72=95% CI, 0.65 −0.80) respectively. | USA White 89/5 % Black 4.7 % Hispanic 3% Asian 1.8% |

| Neuner, 201536 | 16, 462 | AI | Number of days prescription received for 3 months | quasi-experimental pre-post | Amount of Copay | Generic anastrozole introduction increased probabilty of adherence by 5.4 % and with letrozole/exemestane 11 % higher probability | USA |

| Neven, 201433 | 1379 per group | AI | how many tablets taken during the past year (nearly all) | RCT | SC vs. Educational materials | SC (81%) vs. Educational Materials p = 0.4524 | Austria Switzerland Sweden/Finland |

| Yu, 201239 | Treatment (252) /SC (264) | AI | proportion of days covered by prescription refills over the 364 days following the initiation of AI | prospective, controlled, observational | SC vs. standard treatment plus patient support program group | SC (95.9%) vs. Educational materials and reminder calls (95.8%) P = 0.95 | China |

| Ziller, 201341 | 181 | AI | Self reported adherence and an MPR of 80% or more | RCT, 3 arms | SC vs. reminder letters, information booklets vs. reminder letter, telephone calls | SC (48.0%) vs. letter group (64.7%) vs. phone call group (62.7%) P = .75 | Germany |

Abbreviations: SC, standard care; Tam, tamoxifen; AI, Aromatase inhibitors; RCT, randomized controlled trial; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; ET endocrine therapy; AOR, adjusted odds ratio

Results

Study selection

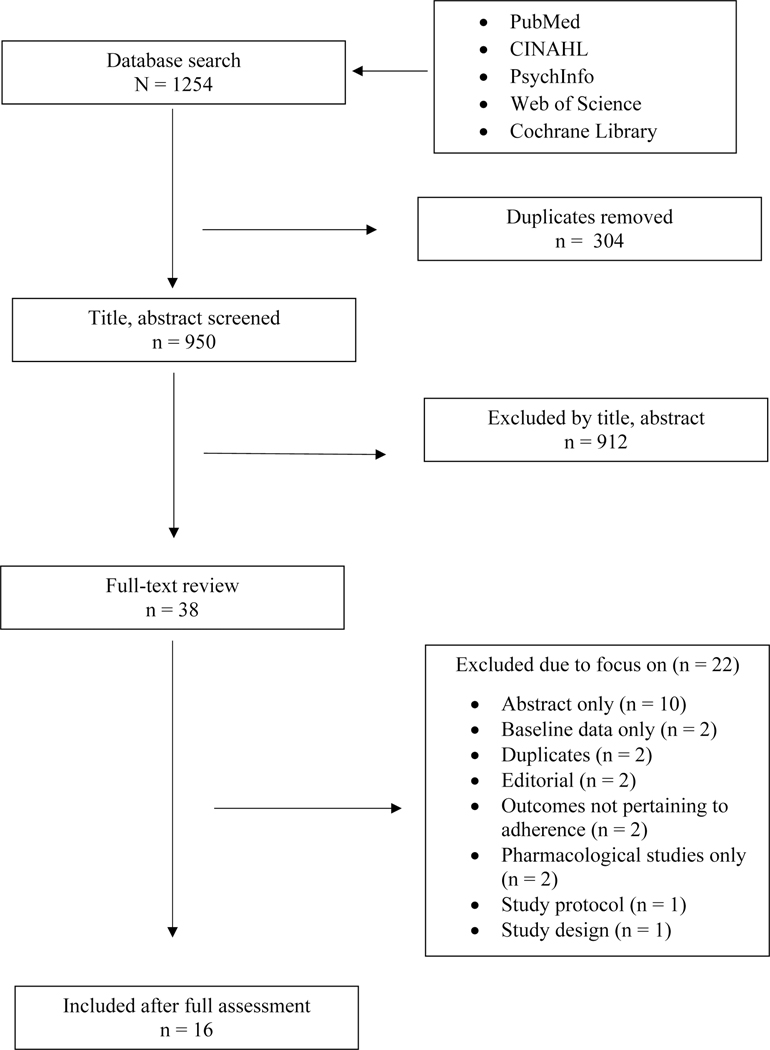

Figure 1 provides a flowchart of the identification, screening, and article selection process, which initially resulted in 1254 original articles about strategies to improve ET adherence. After removing duplicates (n=304), we screened 950 titles and abstracts for study eligibility. From this process, 38 articles were selected for the full-text review. A total of 16 articles were included in the final review; one of the 16 papers reported on the same study at different time intervals, i.e. 1 year and final report.32,33

Figure 1.

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) Flow Chart

Overview of study characteristics

We observed a variety of study designs, adherence definitions and measurement approaches that are presented in Table 1. Eight studies reported inclusion of either tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitors, seven reported inclusion of only aromatase inhibitors, and one study examined tamoxifen only.

Risk of Bias

The risk of bias varied considerably due to the diverse nature of the study designs, e.g. RCT, cross sectional, and quasi-experimental. All studies reported inclusion criteria; sampling methods were appropriate to the design (randomized or convenience). As expected sample size was quite large in the database studies (range from 4915 to 22,160). Large samples were also reported in several of the RCT studies (about 2,700 participants). Human subjects review according to US or international standards was reported in 10 papers (n=16). Four papers used publicly available de-identified data from a claims database and may have been exempt from review.34–37 Two papers did not report on human subjects protection.33,38 However, one of the papers was from the same study33 in which the final paper reported the ethics review.32 The population was adequately described in the studies. Most of the studies addressed bias usually through a discussion of limitations. Only two studies omitted any discussion of bias.35,39

Study Designs

We used the authors’ description of their study design as published in their paper. Two designs (RCT and retrospective) were most commonly used with four papers each.32,33,40,41 Other designs reported included three prospective, 39,42,43 two cross sectional,38,44 and one each of observational,37 quasi-experimental,45 and historical usual care versus an intervention.46 Table 2 shows studies by design that was significantly associated with adherence and provides information on intervention strategies.

Table 2:

Intervention Type and Study Design with Results

| Author | Intervention Type | Type of Manipulation | Measure | Design | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arriola, 201438 | Communication | physician communication frequency | SR | Cross sectional | S - Frequency of physician communication was significantly associated with medication adherence (p < 0.05) |

| Lin, 201744 | Communication | Patient provider communication | SR | Cross sectional | NS - Endocrine therapy adherence was not associated (p > .05) with physician communications although the majority of the patients reported positive physician communications. |

| Castaldi, 201746 | Patient Navigation | Multi-disciplinary Patient Navigation program vs. SC | Other | non-randomized historical usual care versus navigated care | S - Navigation Program clearly demonstrated improved compliance with follow-up and adjuvant therapy in a predominantly minority population. Compliance for NQF measure 1 in NC is 100% versus 57.1% in UC (P = .005). Compliance for NQF measure 2 in NC is 100% versus 68.6% in UC (P < .0001). |

| Liu, 201337 | Communication | patient-provider communication | SR | Observational | S- The use of endocrine therapy 3 years after diagnosis was positively predicted (AOR = 1.22, P = 0.006) by women’s report that their oncologist used patient-centered communication which was assessed at 18 months after diagnosis. |

| Kahn, 200742 | Communication | patient-centered care | SR & other | prospective cohort | S - Tamoxifen use was significantly higher (P = 0.0051) in those women who reported receiving the right amount of support (79%). Adherence was lower when women (81%) were less satifasfied with decision making role (P = 0.0001) and when decision made alone (56%) (P =0.0003). Adherence lower (P < 0.0001) in women who were not informed about side effects prior to experiencing them (62% vs. 85%) |

| Heisig, 201543 | Education | SC versus enhanced education (printed materials & verbal instruction) | Other | Prospective single cohort | S - Adherence significant for satisfaction with ET information (ρ = 0.17, OR 1.55 p = 0.03, n = 133) and associated problems (ρ = 0.22, OR 1.77, p = 0.006) |

| Yu, 201239 | Support group | SC versus standard treatment plus patient support program group | Other | prospective, controlled, observational | NS - Patients in the standard care group stopped use of endocrine therapy at 213.2 days and in the intervention group at 227.8 days; there was no significant difference in the length of time for discontinuation (P = 0.96). |

| Neuner, 201545 | Financial | Amount Copay | Other | quasi-experimental pre-post | S - Generic anastrozole introduction increased increased probabilty of adherence by 5.4 % and with letrozole/exemestane 11 % higher probability |

| Hadji, 201340 | Education | SC versus educational materials | SR & Other | RCT | NS- no difference in rates between the standard and EM arms (50.9% and 52.3%, respectively, P = 0.37). |

| Markopoulos, 2015 | Education | Educational materials versus SC | SR & Other | RCT | NS- end of study results (CARIATIDE) Educational materials did not signiificantly impact adherence in any country. |

| Neven, 2014 | Education | Educational materials versus standard | SR | RCT | S by country - Year 1 Results (CARIATIDE): Educational materials only improved overall adherence with AI in Sweden/Finland; (p = 0.0246) |

| Ziller, 2013 | Education | reminder letters, information booklets versus reminder letter, telephone calls versus SC | SR and Other | RCT, 3 arms, partially- blinded parallel group | NS - No differences were found in adherence at one year post treatment initiation among control group (48.0%) letter group 64.7% or phone call group 62.7%. Post hoc analysis of combined intervention groups versus control was significantly different (p = 0.039). |

| Jacob, 2015 | Education | disease management program versus SC | Other | retrospective | S - DMP patients vs SC showed significant difference (p=0.001) in discontinuing endocrine therapy within 3 years (32.7 % versus 39.6 %). Risk for discontinuing endocrine therapy was lower in DMP patients than standard care (adjusted HR = 0.91, 95 % CI: 0.85–0.98). |

| Kostev, 2013 | Financial | conversion vs no rebate conversion | Other | retrospective | NS - Switching patients to a rebate pharmaceutical process had a significantly negative effect on adherence at one year and 3 years. Discontinuation of treatment was significantly higher at three years (HR:1.27, CI: 1.05 – 1.53, p = 0.014) 44.2% of women who used a rebate process and 33.8% of patients who continued with same process discontinued their treatment (p < 0.01) after one year. |

| Neugut, 201136 | Education | co-payment amount | Other | Retrospective cohort | S - In younger women, the amount of a 90-day co-payment ($90 or more) was significantly associated with non-adherence when compared to a co-payment of $30 (OR= 0.82; 95% CI, 0.72 to 0.94). Older women had similar negative findings regarding the co-payment amounts of $30 or more compared with co-payment amounts of less than $30 OR= 0.72=95% CI, 0.65 −0.80) respectively. |

| Albert, 201147 | Patient Navigation | patient’s interaction with the breast care nurse | SR | retrospective descriptive | S - Adherence was significantly correlated (p < 0.001) with nurse navigator contact (79 contact vs. 56% no contact) and knowledge of hormone receptor status |

Abbreviations: SC, standard care; Tam, tamoxifen; AI, Aromatase inhibitors; RCT, randomized controlled trial; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; ET endocrine therapy; AOR, adjusted odds ratio; S, significant, NS, not significant

Definitions and Measurement of Adherence

Authors differed as to terminology about adherence and used adherence or compliance/compliant,32,33,36,40,41,45 non-adherence,43,44 persistence32,39, non-persistence35,36 and discontinuation.32,34,35,39 Also, authors may have measured two different constructs within one study, commonly whether the patient was taking the drug, e.g. adherence and the time period of taking the drug, e.g. persistence. Compliance and adherence had similar definitions whether by self-report or objective measures such as prescription refill. Participants were considered adherent if they had received or taken 80 % of the drug dispensed and in some cases for analyses this was dichotomized to 80% as being adherent and below 80 % as not adherent.36,43 Discontinuation was defined as lack of continuation of hormone therapy within a specified study time period, e.g. 90 days.34,35 The definition of non-persistence was similar; but the author used a time period within which the drug had not been refilled.36 Persistence was defined as the ongoing use or continuation of hormonal therapy within the specified study time period from initiation to discontinuation; studies lasted from 1 to 4 years.42,46

Data were obtained from self-report exclusively (n=3)37,44,47, self-report and other corroborating data (n=8),32,33,38–40,42,43,47,48 only medical records (n=1)46 de-identified data sets from electronic medical records (n=2)34,35 and claims data (n=2).36,45 Regardless of the source of data, half of the authors used 80% as the standard for adherence as determined by a calculated medication possession ratio or a self-report that provided a similar score.32,33,36,39,40,43,45

Impact of Interventions to Improve ET Adherence

The most frequent intervention strategy reported was patient information/education (n=5). Other strategies included communication between the patient and health care team members (n=5), education and communication (n=2), patient navigation (n=2), and financial changes (n=3). All educational interventions used similar components such as educational materials on various aspects of ET, which were mailed to patients at intervals; although, none of these reported significant results.32,33,39–41 However, one of these studies did show significant results in Sweden and Finland.33 Two studies combined education and communication and both of these studies had significant results.34,43 Similarly, patient navigation, facilitating the patient’s process from diagnosis through treatment showed significant ET adherence.46,47 Details about the interventions are provided in Table 1.

The majority of the studies (n=9) were conducted outside the United States: Germany (n=6)34,35,40,41,43,47 China (n=1)39 and several European/Scandinavian countries in multi-site cooperative studies (n=2).32,33 Of the seven studies conducted in the US, the majority of the participants were white (n=5) with white participants ranging from 54% to 89.5 %.36,38,42,44,45 One study had relatively high African American participation (45%).46 The majority of participants in one study, based in California, were Latina (54%).37 An examination of these studies that included African American and Latina populations did not find any evidence that any cultural adaptations were made. An exception46 used navigated care for a racially diverse cohort of participants. The description of navigation suggested that cultural adjustments were made, such as using bilingual (Spanish and English) navigators, and additional support was provided by American Cancer Society volunteer navigators.46

Discussion

This systematic review extended previous work by identifying and describing a broader range of studies on approaches to improve adherence to ET in women with breast cancer. Of the sixteen studies included in this review, only four were RCTs. While the RCT design yields the highest quality of scientific evidence, we found that the researchers who used this design proposed “educational only” interventions that did not lead to statistically significant improvements in ET adherence; except one study reported significant differences in adherence by country. This finding supports the notion that while education may be a necessary part of an intervention, it is not sufficient for behavior change.49 In fact, the two interventions that combined education and communication reported significant results.

Our findings of inconsistent definitions and measurement of treatment adherence were similar to Hurtado-de-Medoza and colleagues.50 This lack of consistency limited interpretation of findings. Further, the source of the data in four studies was self-reported which decreased credibility of the findings.51 Approaches to increase the scientific rigor of future studies could include longitudinal designs,52 electronic monitoring,53 valid and reliable self-report measures54 and biomarkers such as measurement of tamoxifen in a dried blood spot.55

Health care provider interaction, positive communication, and education are important to patient understanding and adherence.37,38,43,46,47 A standardized program of patient navigation46 or disease management34 had significant impact on adherence. In the disease management program patients received tailored information and individual consultation as well as assistance with transition between inpatient and outpatient care.34 In the patient navigation program, patients received information in English or Spanish and were supported through care transitions.46 In both these cases, the approach was patient centered and adaptable to specific needs of the patient through the continuum of care. In contrast, six studies used well developed educational materials that were provided over time via mail and phone.32,33,39–41,43 While the exact education about the hormonal therapy was not detailed in the papers, in general the educational materials covered benefits, side effects, and other pertinent details about cancer treatment. However, this information was not individualized to the patient. Specific content about the BrCA diagnosis may be needed to help patients understand the critical reason for taking hormonal therapy, such as hormone receptor status.47 Therefore, researchers and provides should determine what content and delivery method works best.

A theoretical approach was used in only one study to frame and direct the components of the intervention.41 Use of theory leads to better design of intervention components and outcomes.56–59 Theories that could be used in adherence interventions include planned behavior,60and self regulation.61 Additionally, frameworks, such as the World Health Organization’s Multidimensional Adherence model,62 could also be useful for planning and evaluating multi-level intervention approaches to improving long-term adherence to ET.

Another weakness of all studies is that none of reported on treatment fidelity62 which is a critical component to improve the quality of interventions.63–65 Treatment fidelity includes an evaluation of the intervention to determine if it was delivered as planned and an assessment of participants’ to establish exposure to the intervention. Even interventions that have been pilot tested may not show an effect and this could be due to problems with fidelity.66 We speculate that treatment fidelity might account for differences found in a multi-site trial where significant changes were demonstrated in the intervention group by country.33

Conclusions

Based on this review, much work remains in the development and testing of interventions to improve ET adherence and adapt interventions to diverse cultures and ethnicities. In this review, of the US studies, none described any cultural adaptation even though both diverse cultures were represented in the samples. Yet, research shows that cultural adaptation is necessary for interventions to be well accepted and adopted by various cultural groups.67–69 Further, cultural adaptation strengthens the effects of the intervention.22,70–72 For example, our work with STORY (Sisters Tell Others and Revive Yourself) demonstrates the effectiveness of a culturally sensitive intervention that improved mood and social connection. Further, secondary analysis of this work found that although adherence was not an outcome of the original study, we documented that intervention participants significantly increased treatment specific knowledge.73

More research is needed in the US where individual health care plans may particularly impact ET adherence. Future interventions should address potential financial and economic barriers to adherence including access to discount pharmaceutical programs.74

We observed a need for standardization of terminology, definitions, and measurement in order to compare findings across studies. Although an 80% medication possession ratio (MPR) is considered adherent, it remains unknown whether this reaches a therapeutic drug level. Measures to determine ET adherence should be used as crosschecks against measurement error, e.g. self-report combined with automated electronic monitoring. Well planned RCTs that include effective intervention components such as communication and education should be implemented. Finally, cancer researchers and clinicians should learn from existing literature on successful intervention in other chronic conditions. Notably, AIDS/HIV work shows theories and models that could be applicable to cancer.75–77

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the following:

• Dr. Felder is supported by a Mentored Research Scientist Development Award to promote diversity from the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (K01CA193667)

• Both Omufuma and Parker are supported by a training grant from the Susan G. Komen® Foundation (GTDR17500160).

• Heiney received partial funding for this paper from and ASPIRE grant from the Vice President of Research Office, University of South Carolina.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Ethical Approval: This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts.

Contributor Information

Sue P. Heiney, College of Nursing, School of Medicine, University of South Carolina.

Pearman D. Parker, College of Nursing, University of South Carolina.

Tisha M. Felder, College of Nursing, Arnold School of Public Health, University of South Carolina.

Swann Arp Adams, College of Nursing, Arnold School of Public Health, University of South Carolina.

Omonefe O. Omofuma, Arnold School of Public Health, University of South Carolina

Jennifer Hulett, College of Nursing, University of South Carolina.

References

- 1.Early Breast Cancer Clinical Trialsists’ Collaborative Group. Effects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and 15-year survival: An overview of the randomised trials. Effects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and 15-year survival: An overview of the randomised trials. 2005;365(9472):1687–1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fontein DBY, Nortier JWR, Liefers GJ, et al. High non-compliance in the use of letrozole after 2.5 years of extended adjuvant endocrine therapy. Results from the IDEAL randomized trial. EJSO. 2012;38(2):110–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kesmodel SB, Goloubeva OG, Rosenblatt PY, et al. Patient-reported adherence to adjuvant aromatase inhibitor therapy using the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale: An evaluation of predictors. Am J Clin Oncol. 2018;41(5):508–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kimmick G, Edmond SN, Bosworth HB, et al. Medication taking behaviors among breast cancer patients on adjuvant endocrine therapy. Breast. 2015;24(5):630–636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Makubate B, Donnan PT, Dewar JA, Thompson AM, McCowan C. Cohort study of adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy, breast cancer recurrence and mortality. Br J Cancer. 2013;108(7):1515–1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kimmick G, Anderson R, Camacho F, Bhosle M, Hwang W, Balkrishnan R. Adjuvant hormonal therapy use among insured, low-income women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(21):3445–3451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Partridge AH, LaFountain A, Mayer E, Taylor BS, Winer E, Asnis-Alibozek A. Adherence to initial adjuvant anastrozole therapy among women with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(4):556–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Partridge AH, Wang PS, Winer EP, Avorn J. Nonadherence to adjuvant tamoxifen therapy in women with primary breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(4):602–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wheeler SB, Kohler RE, Reeder-Hayes KE, et al. Endocrine therapy initiation among Medicaid-insured breast cancer survivors with hormone receptor-positive tumors. J Ca Surviv. 2014;8(4):603–610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gotay C, Dunn J. Adherence to long-term adjuvant hormonal therapy for breast cancer. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2011;11(6):709–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu J, Stafkey-Mailey D, Bennett CL. Long-term Adherence to Hormone Therapy in Medicaid-enrolled Women with Breast Cancer. Health Outcomes Research in Medicine. 2012;3(4):e195–e203. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yung RL, Hassett MJ, Chen K, et al. Initiation of adjuvant hormone therapy by Medicaid insured women with nonmetastatic breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104(14):1102–1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murphy CC, Bartholomew LK, Carpentier MY, Bluethmann SM, Vernon SW. Adherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy among breast cancer survivors in clinical practice: A systematic review. Br Cancer Res Treat. 2012;134(2):459–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCowan C, Shearer J, Donnan PT, et al. Cohort study examining tamoxifen adherence and its relationship to mortality in women with breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2008;99(11):1763–1768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hershman DL, Kushi LH, Shao T, et al. Early discontinuation and nonadherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy in a cohort of 8,769 early-stage breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(27):4120–4128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Riley GF, Warren JL, Harlan LC, Blackwell SA. Endocrine therapy use among elderly hormone receptor-positive breast cancer patients enrolled in Medicare Part D. Medicare & Medicaid. 2011;1(4):E1–E25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chlebowski RT, Kim J, Haque R. Adherence to endocrine therapy in breast cancer adjuvant and prevention settings. Cancer Prev Res. 2014;7(4):378–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ursem CJ, Bosworth HB, Shelby RA, Hwang W, Anderson RT, Kimmick GG. Adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy for breast cancer: Importance in women with low income. J Womens Health. 2015;24(5):403–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hershman DL, Tsui J, Wright JD, Coromilas EJ, Tsai WY, Neugut AI. Household net worth, racial disparities, and hormonal therapy adherence among women with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(9):1053–1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farias AJ, Du XL. Association between out-of-pocket costs, race/ethnicity, and adjuvant endocrine therapy adherence among medicare patients with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(1):86–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nekhlyudov L, Li L, Ross-Degnan D, Wagner AK. Five-year patterns of adjuvant hormonal therapy use, persistence, and adherence among insured women with early-stage breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;130(2):681–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sheppard VB, Wallington SF, Willey SC, et al. A peer-led decision support intervention improves decision outcomes in black women with breast cancer. J Cancer Educ. 2013;28(2):262–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wheeler SB, Reeder-Hayes KE, Carey LA. Disparities in breast cancer treatment and outcomes: Biological, social, and health system determinants and opportunities for research. Oncologist. 2013;18(9):986–993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moon Z, Moss-Morris R, Hunter MS, Carlisle S, Hughes LD. Barriers and facilitators of adjuvant hormone therapy adherence and persistence in women with breast cancer: a systematic review. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2017;11:305–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cahir C, Guinan E, Dombrowski SU, Sharp L, Bennett K. Identifying the determinants of adjuvant hormonal therapy medication taking behaviour in women with stages I–III breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98(12):1524–1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Liew J, Christensen AJ, de Moor JS. Psychosocial factors in adjuvant hormone therapy for breast cancer: an emerging context for adherence research. J Cancer Surviv. 2014;8(3):521–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCarthy AM, Armstrong K, Yang J. Increasing disparities in breast cancer mortality from 1979 to 2010 for US black women aged 20 to 49 years. Am J Public Health. 2015;105 Suppl(3):S446–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reeder-Hayes KE, Meyer AM, Dusetzina SB, Liu H, Wheeler SB. Racial disparities in initiation of adjuvant endocrine therapy of early breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;145(3):743–751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Covidence [computer program]. 2017.

- 30.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(4):344–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chad-Friedman E, Coleman S, Traeger LN, et al. Psychological distress associated with cancer screening: A systematic review. Cancer. 2017;123(20):3882–3894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Markopoulos C, Neven P, Tanner M, et al. Does patient education work in breast cancer? Final results from the global CARIATIDE study. Future Oncol. 2015;11(2):205–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neven P, Markopoulos C, Tanner M, et al. The impact of educational materials on compliance and persistence rates with adjuvant aromatase inhibitor treatment: First-year results from the compliance of aromatase inhibitors assessment in daily practice through educational approach (CARIATIDE) study. Breast. 2014;23(4):393–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jacob L, Hadji P, Albert US, Kalder M, Kostev K. Impact of disease management programs on women with breast cancer in Germany. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;153(2):391–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kostev K, May U, Hog D, et al. Adherence in tamoxifen therapy after conversion to a rebate pharmaceutical in breast cancer patients in Germany. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2013;51(12):969–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Neugut AI, Subar M, Wilde ET, et al. Association between prescription co-payment amount and compliance with adjuvant hormonal therapy in women with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(18):2534–2542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu Y, Malin JL, Diamant AL, Thind A, Maly RC. Adherence to adjuvant hormone therapy in low-income women with breast cancer: the role of provider-patient communication. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;137(3):829–836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arriola KRJ, Mason TA, Bannon KA, et al. Modifiable risk factors for adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy among breast cancer patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;95(1):98–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu KD, Zhou Y, Liu GY, et al. A prospective, multicenter, controlled, observational study to evaluate the efficacy of a patient support program in improving patients’ persistence to adjuvant aromatase inhibitor medication for postmenopausal, early stage breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;134(1):307–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hadji P, Blettner M, Harbeck N, et al. The Patient’s Anastrozole Compliance to Therapy (PACT) Program: A randomized, in-practice study on the impact of a standardized information program on persistence and compliance to adjuvant endocrine therapy in postmenopausal women with early breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(6):1505–1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ziller V, Kyvernitakis I, Knöll D, Storch A, Hars O, Hadji P. Influence of a patient information program on adherence and persistence with an aromatase inhibitor in breast cancer treatment - the COMPAS study. BMC Cancer. 2013;13(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kahn KL, Schneider EC, Malin JL, Adams JL, Epstein AM. Patient centered experiences in breast cancer: Predicting long-term adherence to tamoxifen use. Med Care. 2007;45(5):431–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heisig SR, Shedden-Mora MC, von Blanckenburg P, et al. Informing women with breast cancer about endocrine therapy: Effects on knowledge and adherence. Psychooncology. 2015;24(2):130–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lin JJ, Chao J, Bickell NA, Wisnivesky JP. Patient-provider communication and hormonal therapy side effects in breast cancer survivors. Women Health. 2017;57(8):976–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Neuner JM, Kamaraju S, Charlson JA, et al. The introduction of generic aromatase inhibitors and treatment adherence among Medicare D enrollees. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Castaldi M, Safadjou S, Elrafei T, McNelis J. A multidisciplinary patient navigation program improves compliance with adjuvant breast cancer therapy in a public hospital. Am J Med Qual. 2017;32(4):406–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Albert US, Zemlin C, Hadji P, et al. The impact of breast care nurses on patients’ satisfaction, understanding of the disease, and adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy. Breast Care. 2011;6(3):221–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ziller V, Kalder M, Albert US, et al. Adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy in postmenopausal women with breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2009;20(3):431–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wing RR. Cross-cutting themes in maintenance of behavior change. Health Psychol. 2000;19(1S):84–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hurtado-de-Mendoza A, Cabling ML, Lobo T, Dash C, Sheppard VB. Behavioral interventions to enhance adherence to hormone therapy in breast cancer survivors: A systematic literature review. Clin Breast Cancer. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hugtenburg JG, Timmers L, Elders PJ, Vervloet M, van Dijk L. Definitions, variants, and causes of nonadherence with medication: A challenge for tailored interventions. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2013;7:675–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Voils CI, Hoyle RH, Thorpe CT, Maciejewski ML, Yancy WS Jr. Improving the measurement of self-reported medication nonadherence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(3):250–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sutton S, Kinmonth A-L, Hardeman W, et al. Does Electronic Monitoring Influence Adherence to Medication? Randomized Controlled Trial of Measurement Reactivity. Ann Behav Med. 2014;48(3):293–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Garber MC, Nau DP, Erickson SR, Aikens JE, Lawrence JB. The concordance of self-report with other measures of medication adherence: A summary of the literature. Med Care. 2004;42(7):649–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tre-Hardy M, Capron A, Antunes MV, Linden R, Wallemacq P. Fast method for simultaneous quantification of tamoxifen and metabolites in dried blood spots using an entry level LC-MS/MS system. Clin Biochem. 2016;49(16–17):1295–1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rothman AJ. Toward a theory-based analysis of behavioral maintenance. Health Psychol. 2000;19(1, Suppl):64–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Given B, Given C, Sikorskii A. Deconstruction of a nursing intervention to examine the mechanism of action. ONCOL NURS FORUM. 2007;34(1):199. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Song M-K, Ward SE. Making visible a theory-guided advance care planning intervention. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2015;47(5):389–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Irwin M Theoretical foundations of adherence behaviors: synthesis and application in adherence to oral oncology agents. Clin J Oncol Nur. 2015;19(3 Suppl):31–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Manning M, Bettencourt A. Depression and medication adherence among breast cancer survivors: Bridging the gap with the theory of planned behaviour. Psychol Health. 2011;26(9):1173–1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Latter S, Sibley A, Skinner TC, et al. The impact of an intervention for nurse prescribers on consultations to promote patient medicine-taking in diabetes: A mixed methods study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;47(9):1126–1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.World Health Organization; Adherence to long-term therapies: Evidence for action. Geneva, Switzerland: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gearing RE, El-Bassel N, Ghesquiere A, Baldwin S, Gillies J, Ngeow E. Major ingredients of fidelity: A review and scientific guide to improving quality of intervention research implementation. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31(1):79–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bellg AJ, Borrelli B, Resnick B, et al. Enhancing treatment fidelity in health behavior change studies: best practices and recommendations from the NIH Behavior Change Consortium. Health Psychol. 2004;23(5):443–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Santacroce SJ, Maccarelli LM, Grey M. Intervention fidelity. Nurs Res. 2004;53(1):63–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kearney MH, Simonelli MC. Intervention fidelity: Lessons learned from an unsuccessful pilot study. Appl Nurs Res. 2006;19(3):163–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Airhihenbuwa CO, Ford CL, Iwelunmor JI. Why Culture Matters in Health Interventions: Lessons From HIV/AIDS Stigma and NCDs. Health Educ Behav. 2014;41(1):78–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fisher TL, Burnet DL, Huang ES, Chin MH, Cagney KA. Cultural leverage: Interventions using culture to narrow racial disparities in health care. Med Care Res Rev. 2007;64(5 Suppl):243S–282S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hamilton JB, Agarwal M, Song L, Moore MAD, Best N. Are psychosocial interventions targeting older African American cancer survivors culturally appropriate? A review of the literature. Cancer Nurs. 2011;35(2):E12–E23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jeffe D, Perez M, Yan Y, et al. African American breast cancer survivor stories: Trial usage of a cancer-communication video program. Ann Behav Med. 2015;49(Suppl 1):s5. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Baezconde-Garbanati LA, Chatterjee JS, Frank LB, et al. Tamale Lesson: A case study of a narrative health communication intervention. Journal of Communication in Healthcare. 2014;7(2):82–92. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Champion VL, Springston JK, Zollinger TW, et al. Comparison of three interventions to increase mammography screening in low income African American women. Cancer Detect Prev. 2006;30(6):535–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Heiney SP, Adams SA, Khang L. Agreement between patient self-report and an objective measure of treatment among African American women with breast cancer. J Oncol Navig Surviv. 2014. 5(3):21–27. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Felder TM, Palmer NR, Lal LS, Mullen PD. What is the evidence for pharmaceutical patient assistance programs? A systematic review.. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2011;22(1):24–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Amaro H, Morrill AC, Dai J, Cabral H, Raj A. Heterosexual Behavioral Maintenance and Change Following HIV Counseling and Testing. Health Psychol. 2005;10(2):287–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Amico KR, Barta W, Konkle-Parker DJ, et al. The Information–Motivation–Behavioral skills model of ART adherence in a Deep South HIV+ clinic sample. AIDS Behav. 2009;13:66–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Starace F, Massa A, Amico KR, Fisher JD. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy: An empirical test of the information-motivation-behavioral skills model. Health Psychol. 2006;25(2):153–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]