Abstract

Social isolation describes a lack of a sense of belonging, the inability to engage and connect with others, and the neglect or deterioration of social relationships. This conceptual review describes how social isolation and connectedness affect the well-being of LGBTQ youth. Most studies focused on the psychosocial experience of social isolation, which led to suicide attempt, self-harm, sexual risk, and substance use. We map out how the psychosocial experience is described and measured, as well as how varying types of social connectedness facilitate well-being. We found this scholarly work has drawn from a variety of frameworks, ranging from minority stress theory to positive youth development, to devise interventions that target isolation and connectedness in schools, community-based organizations, and in online environments. Finally, we discuss the importance of addressing social, cultural, and structural dimensions of social isolation in order to foster enabling environments that allow LGBTQ youth to thrive. This conceptual review suggests that individual and social transformations are the result of young people’s meaningful participation in shaping their environment, which is made possible when their capabilities are fostered through social well-being. Our findings suggest the need for measures of social isolation among youth in databanks produced by global institutions, such as the World Health Organization.

Keywords: Social isolation, LGBTQ youth, connectedness, minority stress, social well-being

The World Health Organization (WHO) Constitution defines health as ‘a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’ (WHO, 2014, p. 7). However, the social well-being of marginalized groups is often treated as secondary to their physical and mental health, especially when prioritization of their human rights challenges cultural and political ideologies (Hall & Lamont, 2013; Harkness, 2007). Responding to marginalization involves social, cultural, political, and individual processes, and requires an approach to global public health that emphasizes fostering environments to enable positive social relationships.

A focus on social well-being is particularly important when addressing the needs of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) youth throughout the world. Marginalization due to sexual orientation and gender identity has been linked to higher rates of suicide (Di Giacomo et al., 2018), mental health disorders (Russell & Fish, 2016) substance use (Day, Fish, Perez-Brumer, Hatzenbuehler, & Russell, 2017; Kelly, Davis, & Schlesinger, 2015) and exposure to violence (Espelage, Merrin, & Hatchel, 2018) among LGBTQ youth compared to their heterosexual and/or cisgender counterparts. Because LGBTQ youth have traditionally been defined primarily by their gender identity and sexual orientation, much of the research on this population, particularly in the wake of the HIV epidemic, has focused on sexual risk behaviours. But a clearer understanding of the underlying determinants of the social well-being of LGBTQ youth is necessary in order to address epidemiologic concerns with fundamentally social causes (Padilla, del Aguila, & Parker, 2007).

Social isolation is a determinant of well-being conceptualized to describe the lack of a sense of belonging, the inability to engage and connect with others, and the neglect or deterioration of social relationships. As the process of identity formation is integral to youth development (Goldbach & Gibbs, 2017), the experience of social isolation during this developmental process generates a lack of identity safety due to fear of social devaluation (Gamarel, Walker, Rivera, & Golub, 2014). Youth experience minority stress due to victimization, rejection, discrimination, and internalized stigma in their family, school, peers and social media, religion, racial and ethnic enclaves, and within the LGBTQ community itself (Bouris et al., 2010; Goldbach & Gibbs, 2017). In comparison to heterosexual/cisgender youth, LGBTQ youth report higher incidence of family rejection, bullying, and violence in their school environment, and physical, verbal, and sexual violence in general (Gamarel et al., 2014). Social isolation occurs when the same spaces that are meant to provide meaningful support for youth (e.g., families, schools, religious organizations, online platforms) create an atmosphere of rejection, bullying, and stigma. Social isolation may also result from legal structures, institutional policies, and cultural norms that generate a sense of otherness (Hatzenbuehler & Keyes, 2013).

This conceptual review describes how social isolation and connectedness affect the well-being of LGBTQ youth. As we expected, most of the evidence present focuses on the psychosocial experience of social isolation. We map out how the psychosocial experience is described and measured, as well as how varying types of social connectedness facilitate well-being. We found this scholarly work has drawn from a variety of frameworks, ranging from minority stress theory to positive youth development, to devise interventions that target isolation and connectedness in schools, community-based organizations, and in online environments. Finally, we discuss the importance of addressing social, cultural, and structural dimensions of social isolation in order to foster enabling environments that allow LGBTQ youth to thrive.

Methods

We conducted a scoping evidence mapping of the peer-reviewed literature (Miake-Lye, Hempel, Shanman, & Shekelle, 2016). Evidence mapping is an approach to synthesizing evidence, identifying the gaps in the literature, and presenting a conceptual depiction of the evidence base (Miake-Lye et al., 2016). Evidence mapping allows for the broader inclusion of research (e.g., both quantitative and qualitative) using the minimum quality criterion of publication in peer-reviewed literature, “without limiting to studies that assess the strength or direction of relationships” (Coast, Norris, Moore, & Freeman, 2018, p. 200). As a scoping review, we included studies with a variety of research designs to provide a broad conceptual, thematic definition of the issues of social isolation and connectedness among LGBTQ youth, specifically; its purpose was to identify the range of related concepts and gaps that emerged from the peer-reviewed research on this topic (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005).

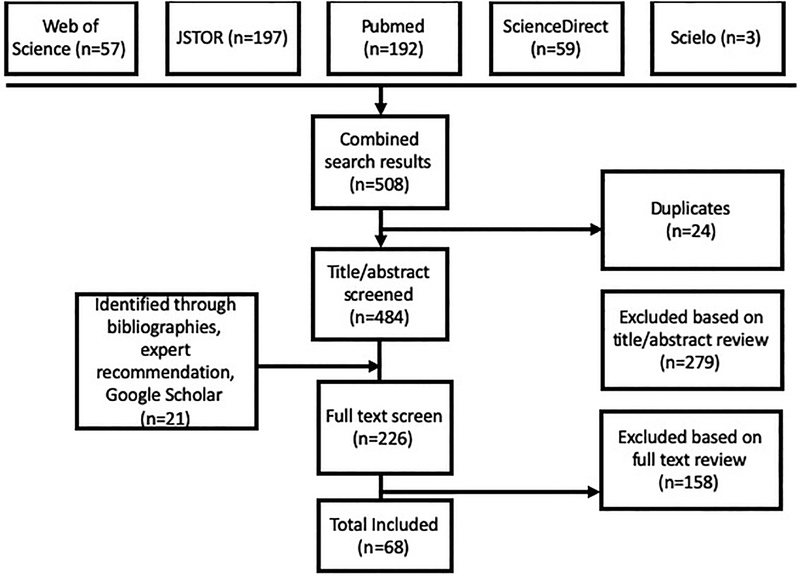

This method is particularly appropriate for capturing research from a variety of scholarship-producing global contexts with a range of ontological and epistemological orientations. In addition to qualifying as peer-reviewed, substantive inclusion criteria included: 1) the primary population is youth, from early/late adolescence to young adulthood, (ages 12–25), who are either LGBTQ-identified or allies; 2) a dimension of social isolation and/or connectedness is included as a variable, measure, or qualitative domain of inquiry; 3) capturing an aspect of the social determinants of health framework, and 4) published between 2000 and 2018. Exclusion criteria included: 1) conference proceedings, 2) encyclopaedia entries, 3) law reviews, 4) cultural or film studies without a health focus, and 5) work published in a language other than English, Spanish and/or Portuguese. Using MeSH permutations of the following search terms: ‘social isolation’ or ‘social connectedness’ or ‘social belonging’ or ‘social inclusion’ or ‘loneliness’ or ‘social exclusion’ and ‘LGBT’ or ‘lesbian’ or ‘gay’ or ‘bisexual’ or ‘transgender’ or ‘queer’ or ‘sexual minority’ or ‘gender minority’ or ‘sexual orientation’ and ‘youth’ or ‘young people’ or ‘adolescent’ or ‘children’, we began by surveying JSTOR, PubMed, SciELO, ScienceDirect, and Web of Science, as depicted in Figure 1. We used Zotero to combine abstracts and citations from these databases, identify duplicates, and conduct an initial screening of titles and abstracts. We excluded 279 publications during the abstract and title review, one of which was excluded because of language (n=1, Russian language). To address potential bias introduced by our language-related exclusion criterion, we asked an expert in sexual health in Russia to review the article so we may consider its inclusion. The article was finally eliminated on the basis that it was a review article that did not collect primary data on our population of interest. We included 21 publications that were not captured through these databases after consultation with subject experts, screening bibliographic references in articles in full review, and through Google Scholar. We conducted a full review of 226 publications. Of those, 68 were selected based on our criteria to be part of our scoping evidence mapping. The selection process is illustrated in Figure 1. After the articles were selected, the first author and two research assistants conducted the initial synthesis. The charting process involved creating a master table in which information was entered for each article, including year of publication, population category (e.g., LGB youth), age of population and sample size, theoretical frameworks used, and main qualitative/quantitative findings relevant to social isolation and connectedness. The thematic analysis presented in this scoping review is a result of thematic patterns observed during this charting process. The three patterns included: 1) studies using the minority stress framework to explore relationship between social isolation and connectedness with psychosocial outcomes, 2) studies describing relational dynamics, including othering, social invisibility and bullying, and 3) studies describing various forms of connectedness to build individual and social resilience and create enabling environments. We organized studies according to the national context where they were conducted. The geographic distribution of studies by their methodological orientation is described in Table 1. After identifying the range of countries where research was published, we described the policy context for LGBTQ people in each of these country-level contexts using reports provided by Human Rights Watch (HRW) and the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, and Intersex Association (ILGA) (HRW, 2019; Mendos & ILGA, 2019). In this description of the policy context, we noted laws that criminalised LGBTQ people, as well as those that protected groups from discrimination, banned conversion therapy, and protected marriage equality and/or civil unions. This policy context provides a fuller picture of what structural factors might affect the study participants where research took place.

Figure 1.

Article Selection Diagram

Table 1:

Geographic Distribution of Studies by Methodological Orientation, Population Categories, and Policy Contextc

| Country | Studies by methodology | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative | Qualitative/Ethnographic/Mixed | Population categoriesa | |

| Australia |

McCallum and McLaren (2011) McLaren, et al. (2015) |

Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual (LGB) adolescents and Heterosexual counterparts | |

| Policy context: Australia passed a referendum supporting same-sex marriage in 2017, resulting in the Marriage Amendment Act 2017, in spite of opponents who argued that same-sex marriage was harmful for children. The debates around the referendum sparked hate speech, especially in social media. Currently, the country is grappling with questions about whether religious institutions, like schools, can discriminate against LGBTQ students and employees. The country recently saw increased activism on behalf of aboriginal queer youth due to their disproportionately high suicide rates. Studies are examining whether marriage equality creates a positive policy context for youth suffering from mental health issues, and conversion therapy bans are being considered at the federal level. (Mendos & ILGA, 2019) | |||

| Belgium | Aerts, et al. (2012) | Dewaele, et al. (2013) | LGB adolescents |

| Policy context: Belgium has been a leader in the international community on behalf of the human rights of LGBTQ people. Marriage was defined to include same-sex partnerships in 2003, and adoption laws granted full joint-paternal rights in 2006. The Anti-Discrimination Laws of 2003, 2007 and 2013 ban discrimination based on sexual orientation. In 2013, article 22 of the Anti-Discrimination Law ‘prohibits the incitement of discrimination, hate, segregation or violence’ based on sexual orientation (Mendos & ILGA, 2019, p. 265) | |||

| Brazil |

Asinelli-Luz and da Cunha (2011) Brandelli Costa, et al. (2017) |

Murasaki and Galheigo 2016 Seffner (2013)b |

Sexual minority youth; Gay, Lesbian, and Homosexual youth experiencing sexual stigma and homophobia; Sexual and gender diversity in schools and public spaces |

| Policy context: Brazil had been a leader in promoting the rights of LGBTQ youth through their ‘Brazil without Homophobia’ and ‘Schools without Homophobia’ programs until the recent changes in the country’s political climate and support for state-sponsored homophobia (Mendos & ILGA, 2019). A decision banning conversion therapy was repealed by a Federal judge in 2017; government is considering policies prohibiting teachers from using of the term ‘sexual orientation’ in schools (HRW, 2018, n.p.). Several state-level laws prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation in Brazil, although the federal constitution does not (Mendos & ILGA, 2019). | |||

| Canada |

Saewyc, et al. (2009)* Veale, et al. (2017)b Wilson, et al. (2018) Martin and D’Augelli (2003)* |

John, et al. (2014)b Lapointe (2015)b Morrison, et al. (2014) Porta, et al. (2017)*b |

LGB adolescents and Heterosexual counterparts; Transgender adolescents; Homosexual adolescents; LGBTQ youth and straight allies; Questioning sexual identity |

| Policy context: In 1996, the Canadian Human Rights Act protects against discrimination based on sexual orientation, and same-sex marriage was legally recognized in 2005 (Mendos & ILGA, 2019). The Canadian government made a public apology for its history of ‘state-sponsored, systematic oppression, and rejection’ of LGBTQ people in 2017 (Mendos & ILGA, 2019, p. 118). In 2018, Bill C-66 ‘expunges the records of individuals who were prosecuted because of their sexuality when homosexuality was criminalized’ (HRW, 2018, n.p.). Canada hosted the second conference of the Equal Rights Coalition (ERC) in 2018, ‘giving a voice to young LGBTI people who are often underrepresented in forums where the rights of LGBTI people are discussed’ (Mendos & ILGA, 2019, p. 60). Conversion therapy has been banned in several Canadian provinces. The Canadian state of Ontario has seen challenges to the inclusion of sexual and gender identities in sex education in schools. In 2017, the Canadian government instituted the ‘X’ non-binary gender marker option for passports and immigration documents. (Mendos & ILGA, 2019) | |||

| Israel | Shilo, et al. (2015) | Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Queer and Questioning youth | |

| Policy context: Israel has some protections against discrimination against persons based on ‘sexual tendencies’ (p. 249) and recognizes ‘reputed [same-sex] couples’ in a status that parallel that of different-sexed married couples (Mendos & IGLA, 2019, p. 285). Same-sex couples were denied the ability to adopt in Israel in 2018, and the Israeli Child Welfare Services argued ‘that having same-sex parents would be a difficulty for a child due to societal prejudice, tacitly sanctioning and perpetuating societal prejudice towards LGBT people’ (Mendos & ILGA, 2019, p. 139). There was a backlash from LGBTQ civil society organisations, which demanded ‘prevention of violence, legal recognition of same-sex families, and equality in health’ (IGLA, 2019, p. 140). Although there is no legal ban on conversion therapy, the Israel Medical Association’s policy expels practitioners found to use these practices (Mendos & ILGA, 2019). | |||

| Italy | Baiocco, et al. (2010) | Lesbian and Gay youth | |

| Policy context: Italian Decree 216 protected persons from discrimination based on sexual orientation in the workplace in 2003, although broader anti-discrimination protections do not exist. Civil partnerships and cohabitation provided same-sex couples tax, inheritance, and social security rights in Law May 20 no. 76 of 2016. The European Court of Human Rights ruled in Orlandi and Others v. Italy, in 2017, in favour of legally recognizing same-sex marriages performed across national borders (Mendos & ILGA, 2019). | |||

| Portugal | Antonio, et al. (2017) | Santos, et al. (2017) | Inclusivity and homophobic bullying in heterosexual youth |

| Policy context: Law against consensual same-sex acts was not repealed until 1983. The Portuguese Constitution of 2005 includes protections against discrimination based on sexual orientation in Article 13(2), and further anti-discrimination in the workplace protections were passed in 2009. The country legalised same-sex marriage in 2010, and same-sex couples gained full adoption rights in 2016. In 2018, Portugal outlawed non-consensual surgeries on intersex children. In the same year, Portugal played a key role in promoting anti-bullying campaigns in Malaysia during the country’s Universal Periodic Review. (Mendos & ILGA, 2019) | |||

| Namibia | Brown (2017) | Homosexual secondary school students | |

| Policy context: Namibia criminalises anal sex between men. According to the Criminal Procedure Act of 2004, sodomy is grouped with ‘crimes for which police are authorised to make an arrest without a warrant or to use of deadly force in course of that arrest’ (Mendos & ILGA, 2019, p. 355). Human rights organisations have begun to open civil society to address criminalising and discriminatory laws in Namibia, holding advocacy events such as ‘We are One’ in 2017 (Mendos & ILGA, 2019). In spite of legal criminalisation, according to a 2016 survey, Namibia is considered among the most socially tolerant countries in Africa (Mendos & ILGA, 2019). | |||

| Netherlands | Baams, et al. (2014) | Same-sex attracted (SSA) and LGB youth | |

| Policy context: The Equal Treatment Act of 1994 prohibits direct or indirect discrimination based on sexual orientation in employment and in access to goods and services; penal code prohibits hate speech (‘insulting statement’ and ‘incitement of hatred’) based on sexual orientation (Mendos & ILGA, 2019, p. 266). In 1998, Book 1 of the Civil Code provided protection for same-sex partnerships ‘virtually equivalent to marriage’ (Mendos & ILGA, 2019, p. 288), and in 2001 allowed for the joint adoption of children for same-sex couples. | |||

| New Zealand | Martin and D’Augelli (2003)* | Lesbian and Gay youth | |

| Policy context: Criminalisation against same-sex sexual acts was abolished in 1986, and in 2017, the government issued an apology for ‘tremendous hurt and suffering’ inflicted by the policy and expunged convictions (Mendos & ILGA, 2019, p. 165). Discrimination based on sexual orientation is prohibited based on the Human Rights Act of 1993, and government is considering adding the prohibition of discrimination based on gender identity. New Zealand outlawed conversion therapy at the national level, and several religious orders have recently taken ‘gay-friendly’ stances. The country passed marriage equality through the Marriage Amendment Act of 2013. Activists from New Zealand joined Australians in the ‘Darlington Statement’ on behalf of human rights for the intersex community in 2017. | |||

| South Africa | Kowen and Davis (2006) | Lesbian youth | |

| Policy context: South Africa became the only country in Africa to recognize same-sex marriage in 2006, and in 2018 legislation prohibited civil servants from opting out of performing same-sex services (Mendos & ILGA, 2019). In 1996, the constitution included protection against discrimination based on sexual orientation and other human rights protections for LGBTI communities. In spite of this, violence against LGBTI groups, such as corrective rape against lesbians and transmen, remains a problem in South Africa. Government, including the Department of Justice and Constitutional Development, and civil society groups established the National Task Team to respond to rapes and other hate crimes against sexual and gender minorities (Mendos & IGLA, 2019; HRW, 2018). A survey conducted in 2016 found that 88% of hate crimes and discrimination go unreported due to fear (Mendos & ILGA, 2019). In 2017, the Limpopo Department of Education was ordered to pay damages to a student for discrimination based on their gender identity (Mendos & ILGA, 2019). | |||

| Taiwan | Chen (2013) | Homosexual male students | |

| Policy context: The Supreme Court in Taiwan called for same-sex marriage to become law within two years in 2017. This process has been challenged by a referendum in 2018 in which Taiwanese voters rejected marriage equality (Mendos & ILGA, 2019; HRW, 2018). Opponents argued that they needed to protect children from the harms of ‘legitimising homosexuality and immorality’ and mounted social media campaigns warning that same-sex marriage would attract HIV-positive people to Taiwan and ‘flood’ the health care system (Mendos & ILGA, 2019, p. 35). Taiwan is among the few countries that has outlawed conversion therapy at the national level (Mendos & ILGA, 2019). The country voted against sexual orientation and gender identity education in schools, although the Gender Equity Education Act of 2004 protects faculty and staff’s sexual orientation in public and private schools (Mendos & ILGA, 2019). | |||

| Thailand |

Van Griensven, et al. (2004) Yadegarfard, et al. (2014)b |

Bisexual and Homosexual adolescents; Male-to-Female Transgender adolescents |

|

| Policy context: Thailand is currently considering legalising same-sex civil unions. In 2007, the Ministry of Labour prohibited discrimination based on ‘personal sexual attitude’ (Mendos & ILGA, 2019, p. 250). UNESCO and Education International have partnered with teachers’ unions in Thailand to survey perceptions on LGBTI rights among teachers. They developed a professional development workshop to train teachers about the impact of bullying and discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity. They launched a School Climate Assessment tool to determine ‘aspects that are essential for a whole school approach to creating a safe and inclusive learning environment for LGBTI students’ (Mendos & ILGA, 2019, p. 59). | |||

| UK |

McDermott, et al., (2008)b McDermott (2011)b McDermott (2015)b McDermott, Hughes, and Rawlings (2018a, 2018b)b McDermott and Roen (2012)b McDermott, Roen and Piela (2013)b Roen, et al. (2008)b |

Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender youth; Queer youth; LGBT youth and heterosexual counterparts in rural and urban areas; LGBT youth contributing to online discussion boards |

|

| Policy Context: The Marriage Act of 2014 affirms the legality of same-sex marriage in England and Wales (Mendos & ILGA, 2019). The Employment Equality Regulations of 2003, and Equality Act Regulations of 2007 and 2010 ban discrimination based on sexual orientation in employment, education, public functions and services (Mendos & ILGA, 2019; McDermott, 2011). The Criminal Justice and Immigration Act of 2008 ‘prohibits the incitement to hatred on the ground of sexual orientation’ (Mendos & ILGA, 2019, p. 267). Recent efforts in Parliament (Conversion Therapy Bill) and in the NHS England and NHS Scotland have moved to ban conversion therapy (Mendos & ILGA, 2019). | |||

| USA |

Baams, et al. (2015) Birkett, et al. (2015)b Day, Perez-Brumer, Russell (2018)b Detrie and Lease (2007) Duong and Bradshaw (2014) Eisenberg and Resnick (2006) Goldbach., et al., (2015) Hatchel and Marx (2018)b Hatzenbuehler, et al., (2012) Hatzenbuehler and Keyes (2013) Martin and D’Augelli (2003)* McConnell, et al. (2015)b Needham and Austin (2010) Poteat, et al., (2015) Poteat and Sheerer (2016)b Ryan, et al. (2010)b Saewyc, et al. (2009)* Seil, et al. (2014) Simons, et al. (2013)b Taliaferro, et al. (2017) Whitaker, et al. (2016) Williams and Chapman (2012) Zimmerman, et al. (2015) |

DiFulvio (2011) Fields, et al. (2015) Gamarel, et al., (2014)b McCormick, et al. (2016)b Muñoz-Laboy, et al. (2009) Paceley (2016)b Porta, et al. (2017)*b Ragg, et al. (2006) Reed and Miller (2016) Romijnders, et al. (2017)b Singh, et al. (2014)b Steinke, et al. (2017)b Theriault, et al. (2014)b |

LGB adolescents and Heterosexual counterparts; LGBT youth; Lesbian and Gay youth; Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Questioning adolescents; Bisexual adolescents; Transgender adolescents; Sexual Minority Youth (SMY); Sexual Minority Women (SMW); High School Students; Gay-Straight Allies and Advisors; Young Black Men who have Sex with Men (MSM); Young Black Gay and Bisexual Men (GBM); LGBTQ Youth of Color; LGBTQ youth in the child welfare system; Bisexual Latino/a Male and Female Youth; Gender and Sexual Minority (GSM) Youth; Trans Youth |

| Policy context: The Mathew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act of 2008 ‘provides for enhanced penalties for crimes motivated by perceived or actual sexual orientation’ (Mendos & ILGA, 2019, p. 259). After the Supreme Court’s decision in Obergefell v. Hodges in 2015, same-sex marriage became legal across the USA, but there is vast variation in how education, employment, housing, and other social determinants of health of LGBTQ people have been protected at the subnational (state) level in the USA (Mendos & ILGA, 2019; HRW, 2018). For example, limitations to transgender inclusivity in gender-segregated public restrooms have challenged school climates (Mendos & ILGA, 2019; HRW, 2018). Large data sets were limited by the inclusion of LGB, but not transgender, youth. | |||

| Vietnam | Horton (2014) | Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual youth | |

| Policy context: The Penal Code of 1999 does not ‘criminalise consensual same-sex sexual acts between adults’ (Mendos & ILGA, 2019, p. 189). Vietnam does not have legal protections against discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity, but the government is considering instituting legal protections and improving health access for transgender people (Mendos & ILGA, 2019). | |||

Represents a cross-national study

Column identifies categories used to classify participants in the studies in each country;

Denotes study that includes transgender youth or focuses on transgender experience in its scope.

Policy context briefly describes the national and cultural context where studies took place. Most information about policy context is drawn from Huma Rights Watch country profiles and the 2019 ILGA report on state-sponsored homophobia.

RESULTS

Of the 68 studies reviewed in this study, 37 were quantitative (54%) and 31 (46%) qualitative, ethnographic, or mixed methods. Among quantitative studies, 9 studies (24%) included transgender youth, and many of the studies used data sets that only asked questions about sexual orientation. Quantitative data sets included: National Examination of High School in Brazil; Brazilian Youth Research Survey; Youth Risk Behavior Survey in New York; Minnesota Student Survey; California Healthy Kids Survey; Oregon Healthy Teens Survey; National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health; and British Columbia Adolescent Health Surveys. Among qualitative, ethnographic, and mixed methods studies, 18 studies (61%) included transgender youth as participants. These studies ranged from small projects (n=4) involving body mapping interviews (Murasaki and Galheigo, 2016) to ethnographic studies of physical spaces (Seffner, 2013) and online spaces (McDermott et al., 2008) to mixed methods studies that combined semi-structured interviews and online surveys (McDermott, Hughes and Rawlings, 2018a, 2018b). Although the USA produced a large portion of the literature, studies conducted in the UK and Canada were the most inclusive of transgender youth and of a greater variety of epistemological approaches to researching social isolation and connectedness. In our sample of countries reflected in the studies selected, Namibia was the only country that criminalises same-sex sexual relations. In the following sections, we describe the thematic synthesis that resulted from our charting process.

Minority Stress and Psychosocial Outcomes

Most of the literature we reviewed employed a version of the minority stress model to explore the effects of social isolation on the mental health of LGBTQ youth. This model posits that marginalized individuals internalize social norms (e.g., heterosexism, homophobia, transphobia, racism, classism) that stigmatize them, resulting in psychological distress (Meyer, 1995). The theory connects individual perceptions with social experience and distal factors (Duong & Bradshaw, 2014; John et al., 2014). In the study of social isolation among LGBTQ youth, social psychologists and sociologists measured the effects of social isolation on mental health using constructs such as perceived loneliness (Chen, 2013; Martin & D’Augelli, 2003; McConnell, Birkett, & Mustanski, 2015), perceived burdensomeness (Baams, Grossman, & Russell, 2015), expected rejection (Baams, Bos, & Jonas, 2014), perceived sense of connectedness (Goldbach, Schrager, Dunlap, & Holloway, 2015; Hatzenbuehler, McLaughlin, & Xuan, 2012), sense of belonging (McCallum & McLaren, 2011), and perceptions of sexual stigma (Brandelli Costa et al., 2017). Studies with a strong focus on psychosocial outcomes and mental health were conducted primarily in the global North, in the USA (Baams et al., 2015; Duong & Bradshaw, 2014; Goldbach et al., 2015; Hatchel & Marx, 2018; Hatzenbuehler et al., 2012; Reed & Miller, 2016; Seil, Desai, & Smith, 2014; Zimmerman, Darnell, Rhew, Lee, & Kaysen, 2015), Canada (John et al., 2014; Morrison, Jewell, McCutcheon, & Cochrane, 2014; Wilson, Asbridge, & Langille, 2018), UK (McDermott, 2015; McDermott, Roen, & Scourfield, 2008), Australia (McCallum & McLaren, 2011; McLaren, Schurmann, & Jenkins, 2015), New Zealand (Martin & D’Augelli, 2003), Netherlands (Baams et al., 2014), Italy (Baiocco, D’Alessio, & Laghi, 2010), and Belgium (Aerts, Van Houtte, Dewaele, Cox, & Vincke, 2012; Dewaele, Van Houtte, Cox, & Vincke, 2013); although, several were conducted in the global South in Brazil (Asinelli-Luz & Cunha, 2011; Brandelli Costa et al., 2017), Taiwan (Chen, 2013), and Thailand (van Griensven et al., 2004; Yadegarfard, Meinhold-Bergmann, & Ho, 2014).

Social isolation was associated with negative mental health outcomes including depression (Baams et al., 2014; McCallum & McLaren, 2011; Reed & Miller, 2016; van Griensven et al., 2004; Wilson et al., 2018; Yadegarfard et al., 2014); suicidal ideation and attempt (Baams et al., 2015; Brandelli Costa et al., 2017; Duong & Bradshaw, 2014; Eisenberg & Resnick, 2006; McDermott et al., 2008; Seil et al., 2014; Taliaferro & Muehlenkamp, 2017; Veale, Peter, Travers, & Saewyc, 2017; Whitaker, Shapiro, & Shields, 2016; Yadegarfard et al., 2014); substance use (Baiocco et al., 2010; Goldbach et al., 2015; Hatchel & Marx, 2018; Reed & Miller, 2016; Seil et al., 2014); and limited access to mental health services (Williams & Chapman, 2012). In their study conducted in Thailand with 260 youth, ages 15–25, of which 129 identified as transgender, Yadegarfard et al. (2014) found that loneliness was a strong predictor for depression, suicidal thinking, and sexual risk behaviour. Among transgender youth, family rejection was positively associated with higher levels of depression symptoms (B = 0.19; p < 0.05) and social isolation was associated with suicidal ideation (B = 0.17; p < 0.05). In Brazil, Brandelli Costa et al. (2017), in a study conducted among 9,919 adolescents 11–24 years of age, found that suicide attempts among youth who experienced sexuality-related stigma had increased by 60% between 2004 and 2012, whereas the rates had decreased by 20% among those who did not report experiencing stigma.

For youth with intersectional identities, conforming to social norms is more challenging. Research on intersectionality and minority stress have explored the intersection of LGBTQ+ status and racial/ethnic minority status (Fields et al., 2015; Fields, Morgan, & Sanders, 2016; Hatchel & Marx, 2018; Reed & Miller, 2016) and few studies have explored additional exclusion based on social class status (Brandelli Costa et al., 2017; Kowen & Davis, 2006; McDermott, 2011; McDermott & Roen, 2012). McDermott and Roen (2012) draw attention to the necessity of making space for intersectionality and diversity when conducting research with LGBTQ youth. Hatchel and Marx (2018) used the minority stress model in combination with the theory of intersectionality to understand the relationship between school belonging and sense of victimization and drug use among transgender youth ages 10–18 years who participated in the California Healthy Kids Survey. They found that school belonging had a direct effect on drug use (B= 0.14, p <0.001), and that transgender youth of colour experienced greater levels of victimization than their White and/or cisgender counterparts. Belonging to several marginalized communities and identities (based on sexual orientation, class, race, ethnicity, gender, and disability) presents social hurdles that youth internalize and result in psychosocial stress (Brown, 2017).

Relational Dynamics: Othering, Social (In)visibility, and Bullying

In addition to examining psychosocial outcomes, the research on social isolation among LGBTQ youth has started to concentrate on stigmatizing relational dynamics, such as ‘othering,’ social invisibility, and bullying, which generate social exclusion. Othering exists when those with lifestyles outside of mainstream ideas of acceptability are classified as ‘deviant, abnormal, and unnatural’ (Brown, 2017, p. 343). Marginalization and isolation generated by othering are exacerbated when individuals leave their safety zones or cultural enclaves and interact with broader society in spaces such as school and work. Othering, like the minority stress model, describes an interaction between the outside environment, social relationships, and an internalized lack of social well-being. This framework, however, emphasizes social well-being much more than the minority stress framework, which focuses primarily on mental health outcomes. Othering results in widening disparities in access to essential resources, such as housing, employment opportunities, and healthcare (Brown, 2017). DiFulvio (2011), in a qualitative study of 15 ‘sexual minority’ youth in rural Massachusetts, found that youth who felt devalued forged resilient relationships to cope with ‘otherness.’ Social connectedness, defined as ‘belonging where youth perceive they are cared for and empowered within a given context’, was related to ‘affirming the self,’ ‘finding others like you,’ and ‘moving toward action’ as thematic domains that emerged in life history interviews (DiFulvio, 2011, p. 1611). Social connectedness, characterized by contexts where youth feel they are cared for and empowered, can mediate the effect of stress, discrimination, and violence on mental health outcomes (DiFulvio, 2011; Gamarel et al., 2014; McDermott, 2015; Roen, Scourfield, & McDermott, 2008). The relational model of health provides some useful insight into how relationships can foster resilience. According to the relational model of health, isolation occurs as a result of violence and social rejection, and isolation is often the main source of pain and suffering for young LGBTQ individuals. Within this model, there are four main aspects of relationships that reduce pain and suffering, and promote resilience: empowerment, authenticity, perceived mutual engagement, and conflict tolerance. High levels of each of these aspects have been correlated with psychological well-being, high self-esteem, and self-development, and have also been shown to negatively associated with depression symptoms, sexual risk behaviours, and substance use (Gamarel et al., 2014).

Similar studies, based on positive youth development theories have found that a sense of social invisibility generates isolation when youth lack mentors or live in remote, rural areas (Dewaele et al., 2013; Horton, 2014; Kowen & Davis, 2006; Paceley, 2016; Ragg, Patrick, & Ziefert, 2006). Kowen and Davis (2006) in South Africa with 11 Lesbian youth (16–24 years of age), they found that social isolation and sense of otherness stemmed from the invisibility of young lesbians and from marginalization within the family, school, media, and broader social context. Participants reported lacking positive role models as driving social isolation. In another study conducted in small towns and rural communities in the USA, Paceley (2016) conducted qualitative interviews with 34 gender and sexual minority youth (14–18 years old) and found that youth living in rural and small towns experience an additional layer of place-related marginalization. Gender and sexual minority (GSM) youth in small communities reported lacking GSM friends and spaces, which led to social isolation; they needed to gain social acceptance and visibility in families, peer groups, schools, and communities, and to develop their social identities in ‘safe spaces’ (Paceley, 2016). Another study that examined the experiences of 21 gay and lesbian identified youth (16 – 22 years old) living the foster care system, found youth’s perception of foster care service providers shaped their feelings of isolation, safety, affirmation, and connection with community (Ragg et al., 2006). Youth felt more vulnerable in the foster care system due to their mistrust of case workers and fear of their gay/lesbian identity being discovered; they preferred social ‘invisibility’ over the possibility of social rejection (Ragg et al., 2006). Social invisibility becomes a coping strategy in situations and contexts in which youth feel they need to ‘manage’ their exposure to discrimination (Dewaele et al., 2013). In a study conducted in Belgium with 24 lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth (16–18 years old), Dewaele et al. (2013) found youth used invisibility to avoid homonegativity and strategic visibility to connect with other LGB youth to navigate and mitigate isolation. Although invisibility may be an effective strategy for avoiding discrimination, it comes with negative consequences for the development of the ‘self’ that result from isolation (Horton, 2014). A study on 10 lesbian and gay identified youth (20–25 years old) conducted in Vietnam found that these invisible youth experienced institutionalized ‘misrecognition’ in families, communities, educational system, media and laws. Homosexuality was considered a ‘social disease’; and lack of social recognition was thematically related to isolation, fear, and lack of social well-being (Horton, 2014).

Recent studies have focused on bullying as a major relational determinant of social isolation and self-harm (Duong & Bradshaw, 2014; McDermott, Hughes, & Rawlings, 2018b, 2018a; Santos, Silva, & Menezes, 2017; Veale et al., 2017). Veale et al. (2017) administered the Canadian Trans Youth Heath online survey to 923 transgender youth (14–25 years of age) in Canada. They found that, among youth ages 14–18, 64% reported having been bullied, taunted, and/or ridiculed, and 33% were bullied on the Internet in past year. The odds of non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) was higher among those who reported experiencing enacted stigma (OR= 1.25; 95% CI: 1.13–1.38), a composite index based on experiences of discrimination, harassment, or violence. To explore the relationship between experiences of bullying and suicidal behaviours, Duong and Bradshaw (2014) analysed data from 951 LGB youth who completed the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS), which is administered to 9th to 12th graders in New York. The odds of attempted suicide were higher among youth who had experienced school bullying (OR = 3.01; 95% CI: 1.09 – 8.33, p = 0.034), cyberbullying (OR = 3.07; 95% CI: 1.39–6.79, p =0.006), and both school and cyberbullying (OR = 5.10; 95% CI: 1.90–13.71, p = 0.001). Feeling connected to an adult in schools may protect students who experienced both school and cyberbullying from attempted suicide (OR= 0.18; 95% CI= 0.04–0.75; p= .019) and making a serious suicide attempt (OR= 0.16; 95% CI= 0.03–0.76; p= .021). These studies have focused primarily on the individual psychological outcomes associated with the experience of stigmatizing relational dynamics.

Few studies go further to examine how the policy environment shapes these relational dynamics (Brown, 2017; Hatzenbuehler & Keyes, 2013; John et al., 2014; Mello, Freitas, Pedrosa, & Brito, 2012). Hatzenbuehler and Keyes (2013) analysed the Oregon Healthy Teens survey, which included 11th grade students of which 1,413 identified as LGB, to observe how living in counties with a higher proportion of school districts that had adopted anti-bullying policies inclusive of sexual orientation may affect LGB students’ mental health. The study divided anti-bullying policies into three categories based on the extent of their inclusiveness, and it determined that the risk of suicide attempts among LGB students was lowest in counties with the most inclusive (containing sexual orientation on the list of included protections) anti-bullying policies. Living in the counties with inclusive anti-bullying policies was a protective factor against attempted suicide for LGB youth (OR = 0.18, 95% CI: 0.03–0.92). The lack of LGB protective policies is a form of structural stigma because it enables exclusive homophobic rhetoric to persist. A small qualitative study conducted in Namibia with 12 students in secondary school who self-identified as homosexual suggested that these students experienced isolation and violence in school as a result of Namibian laws that consider homosexuality a criminal sexual offense (Brown, 2017). Namibian youth reported experiencing bullying in school environments from other students, as well as from school teachers and administrators (Brown, 2017). More research is needed to measure effects of policies, oppressive systems, and structural stigma on social isolation and social well-being.

Building Resilience and Enabling Environments

A subset of literature examined the role of social resilience and enabling environments as protective factors against social isolation (Day, Perez-Brumer, & Russell, 2018; Detrie & Lease, 2007; DiFulvio, 2011; Gamarel et al., 2014; Hatchel & Marx, 2018; McCormick, Schmidt, & Terrazas, 2016; Murasaki & Galheigo, 2016; Reed & Miller, 2016; Romijnders et al., 2017; Seffner, 2013; Shilo, Antebi, & Mor, 2015; Singh, Meng, & Hansen, 2014; Zimmerman et al., 2015). Studies identified various dimensions of connectedness (i.e., the ability to form social relationships with people, groups, and/or contexts) fostered within enabling relationships and environments, including school connectedness (Saewyc et al., 2009; Veale et al., 2017; Whitaker et al., 2016; Wilson et al., 2018), family connectedness (Eisenberg & Resnick, 2006; Munoz-Laboy et al., 2009; Ryan, Russell, Huebner, Diaz, & Sanchez, 2010), parent connectedness (Needham & Austin, 2010; Simons, Schrager, Clark, Belzer, & Olson, 2013; Taliaferro & Muehlenkamp, 2017; Williams & Chapman, 2012), foster family connectedness (McCormick et al., 2016; Ragg et al., 2006), teacher connectedness (Duong & Bradshaw, 2014; Taliaferro & Muehlenkamp, 2017), peer connectedness (Birkett, Newcomb, & Mustanski, 2015; McConnell et al., 2015; McLaren et al., 2015), connectedness to the LGBTQ community (Baiocco et al., 2010; Goldbach et al., 2015; Zimmerman et al., 2015), and connection to broader society (Poteat, Scheer, Marx, Calzo, & Yoshikawa, 2015; Zimmerman et al., 2015). Taliaferro and Muehlenkamp (2017) in their analysis of the Minnesota Student Survey, found that parent connectedness was protective against suicide attempt among bisexual youth (OR = 0.93, 95% CI: 0.88–0.98). Among gay or lesbian youth, school safety was protective of suicide attempt (OR=0.65, 95% CI: 0.47–0.91) and repetitive self-harm (OR = 0.56, 95% CI: 0.40–0.80). Several other studies indicated that bisexual youth experienced lower levels of school and family connectedness than their gay/lesbian and heterosexual counterparts (Munoz-Laboy et al., 2009; Saewyc et al., 2009). Whitaker et al. (2016) analysed the responses of 356 LGB youth who participated in the California Healthy Kids Survey. They found higher levels of school connectedness were protective for suicidal ideation (OR = 0.59, 95% CI: 0.41–086) among LGB youth. In contrast, we could only identify one study that used ethnographic methods to observe school context, rather than focusing on the individuals’ perception of their connection with people in their environment (Seffner, 2013). In Brazil, Seffner (2013) conducted ethnographic observation of three public schools to evaluate whether practices in these contexts were aligned with intended goals to fight homophobia, respect diversity, and include all students. This study found that heteronormative masculinity was pervasive in school contexts and challenged their goals towards inclusion of non-normative sexualities and gender identities.

Several studies based in the global North have explored relationship between sense of connectedness to the LGBTQ community and social well-being (Baiocco et al., 2010; Detrie & Lease, 2007; Goldbach et al., 2015; Zimmerman et al., 2015). Zimmerman et al. (2015), in a study based in the US consisting of online surveys with 843 sexual minority women (SMW) 18–25 years of age, found that SMW who experienced rejection from their family sought a connection with sexual minority communities. Young SMW who were out to their family reported higher levels of connectedness with sexual minority communities (B = .06; p = .049) and higher levels of collective self-esteem (B = .07; p = .022). SMW of non-White racial background experienced lower levels of connectedness (B= −0.08; p =0.007) when out to their family. They argued that SMW found resilience, or the ‘adaptation under specific risks or stress,’ through their community connectedness and community-level self-esteem (Zimmerman et al., 2015, p. 179). In another Internet survey with 218 LBG youth (14–22 years of age), Detrie and Lease (2007) found social connectedness and collective self-esteem were positively associated with self-acceptance (B= 0.43, P <0.001; B= 0.24, P <0.001, respectively) and with environmental mastery (B= 0.48, P <0.001; B= 0.11, P <0.05, respectively). The measure of environmental mastery, or the ‘ability to manipulate and control complex environments,’ was drawn from Ryff (1989)’s subscale, which intends to capture ‘active participation in and mastery of the environment are important ingredients of an integrated framework of positive psychological functioning’ (Ryff, 1989, p. 1071). The use of collective self-esteem was construct used in both of these studies to capture ‘the individuals’ self-evaluations of their social identity based on memberships in groups, both private and interpersonal’; it ‘results from the individual’s perception of the worth, value, and importance of their group membership’ (Detrie & Lease, 2007, p. 177). Other research has found that a strong connectedness to LGBTQ communities can be associated with drug (Goldbach et al., 2015) and alcohol use (Baiocco et al., 2010). Goldbach et al. (2015), in their US-based study with 1,911 LGB youth ages 12–17, found that although connectedness to queer community was negatively associated with internalized homophobia (B= −0.680, t = −28.195, p = .001), this connectedness was a risk factor for marijuana use (OR = 1.445, t = 3.443, p < .001). Studies are needed to observe the relationship between connectedness to the LGBTQ community and these dimensions of social well-being in the global South, especially in collectivist societies where notions of resilience and self-esteem are tied to collective well-being.

There were two kinds of identity-safe, enabling environments salient in the literature that fostered social connectivity among LGBTQ youth: Genders and Sexualities Alliances (GSAs) and online interventions. Identity-safe spaces foster positive health by encouraging self-development and providing opportunities for relationship building and support (Gamarel et al., 2014; Lapointe, 2015; Paceley, 2016; Poteat et al., 2015; Theriault, 2014). Identity-safe spaces provide a nurturing environment where LGBTQ youth, who may experience rejection from their biological families and/or in schools, can build a family of choice that will provide emotional, informational and material support (DiFulvio, 2011). Gamarel et al. (2014) found that within safe spaces, LGBTQ youth have described the creation of a sense of “we”, of unity among members that can help withstand violence, bullying, and discrimination faced outside the group. This kind of youth development approach identifies protective factors for LGBTQ youth instead of simply categorizing them as an at-risk population (DiFulvio, 2011). The social connectedness that develops in safe spaces provides an opportunity for youth to come together and collectively make sense of their identities and the negative experiences associated with those identities (DiFulvio, 2011).

The Genders and Sexualities Alliance (GSA) Network, formerly known as Gay-Straight Alliance Network, is well-known for creating safe spaces for self-expression and for uniting trans and queer youth at schools across the United States. The intervention has had some global diffusion through its adoption in Canada (John et al., 2014; Porta et al., 2017). GSAs can play a significant role in socialization and advocacy to foster a sense of empowerment and of belonging (Lapointe, 2015; Poteat et al., 2015). In their study of 448 high school participants in Massachusetts GSA Network (of which 268 identified as LGBQ), Poteat et al. (2015) identified individual (e.g., demographics, general engagement) and contextual attributes (e.g., collective social justice efficacy, collective perception of school hostility) that promoted socialization (e.g., dances, parties, talent shows) and/or advocacy (e.g., Day of Silence, Ally Week, Youth Pride) within GSAs. They found that collective perception of school hostility was positively associated with greater engagement in advocacy (B= .98, p < 0.01). Advocacy enabled GSAs to address external, as well as internal, issues and aims to improve visibility of LGBTQ communities and to refute stereotypes about non-heteronormative identities (Poteat et al., 2015). It may be that socialization and the development of social connections is the primary goal of participation, and then once relationships are established within the GSA, the members are better able and willing to participate in advocacy which can benefit those beyond their immediate social group.

The notion of LGBTQ ‘allyship’ was central to describing social connectedness with the broader community (António, Guerra, & Moleiro, 2017; Lapointe, 2015; Poteat & Scheer, 2016). An ally is “someone who advocates and works to address issues involving human and civil rights” and who is dedicated to positive social change and committed to standing with LGBTQ persons against othering, stigma, and discrimination (Lapointe, 2015, p. 145). A Canadian study of 68 heterosexual college students who participate in GSAs found that three factors were key in motivating allyship and LGBTQ-positive attitude formation: early exposure and normalization experiences, encounters with LGBTQ persons in high school or college, and empathizing with LGBTQ persons (Lapointe, 2015). Allies actively engaged in activities and opportunities to question their heteronormative privileges and acknowledge their prejudices while challenging the standard idea of ‘normal’ (Lapointe, 2015). The push to become an ally differs from person to person, but many heterosexual young people are motivated to become allies when they experience an LGBTQ friend endures hurtful and negative experiences during and after the process of ‘coming out’ (Lapointe, 2015). Personal experiences of marginalization can also motivate people to become allies when they perceive the unjustness of discrimination based on gender and sexual identity (Lapointe, 2015). Allyship is not limited to youth, many adults take on the role of ally for LGBTQ youth. Adults in a position of allyship, especially those involved in GSAs need to be experienced in providing tailored support to LGBTQ youth who often carry intersectional identities (Poteat & Scheer, 2016). Research conducted by Poteat and Scheer (2016) draws attention to the importance of self-efficacy when facilitating race-related discussions and other topics specific to LGBTQ diversity. LGBTQ GSA advisors with personal experience of sexual orientation-based discrimination may feel more efficacious than heterosexual advisors when it comes to working with marginalized youth. Self-efficacy levels in working with LGBTQ youth vary depending on the identity of the advisor, suggesting that there is room for providing more support and training for those directly involved in serving as allies to the LGBTQ community (Poteat & Scheer, 2016).

The second type of enabling environment salient in the research consists of online interventions and platforms, which may be a viable space for addressing social isolation among LGBTQ youth (McDermott, 2015; McDermott & Roen, 2012; McDermott, Roen, & Piela, 2013; Steinke, Root-Bowman, Estabrook, Levine, & Kantor, 2017). Recent studies have utilized online platforms to conduct research on LGBTQ isolation and explore how LGBTQ youth use the Internet to seek support to affirm their social identities (McDermott, 2015; McDermott & Roen, 2012). The Internet was identified as a space where LGBTQ may find supportive outlets and social engagement (McDermott & Roen, 2012), especially when LGBTQ youth use strategies like social invisibility to hide or deny their minority identities in an effort to cope with and avoid discrimination (Dewaele et al., 2013; DiFulvio, 2011). The Internet is an especially critical site for intervention to address cyberbullying (Veale et al., 2017). Online forums can be designed to be identity-safe spaces for LGBTQ youth to develop and explore different aspects of their identities and same-sex desires, which they may not be able to express in their lives offline (McDermott et al., 2013; Steinke et al., 2017). In a study with 92 sexual and gender minority youth (15–20 years old), Steinke et al. (2017) found that social isolation (e.g., experienced as a lack of social representation and a lack of validating community) and stigma (e.g., discrimination, oversexualization) drove the need for digital, online interventions with community-relevant information. They also found that youth wanted interventions holistic well-being (physical, mental and social), rather than those narrowly focused on HIV prevention (Steinke et al., 2017). Online research studies have found that LGBTQ adolescents who experience extreme social isolation and participate in self-harm are especially less likely to seek support for mental health problems (McDermott, 2015). In their Internet-based study of online spaces, McDermott (2015) conducted qualitative analysis of online discourse of LGBTQ youth (ages 13–25 years) on 20 websites; and found that although they may be reluctant to seek out face-to-face help, many LGBTQ youth turn to online support networks to deal with issues of homophobia, transphobia, self-harm, and suicidal thoughts among other complex social and mental health issues (McDermott, 2015). Because of their status as a safe space for LGBTQ oriented discourse, Internet discussion boards, chat rooms, forums, and instant messaging are useful for hosting discussions among youth who experience isolation (McDermott & Roen, 2012). Ethnographic research has employed asynchronous online interviews to understand how marginalized LGBTQ youth use online environments and navigate online identities (McDermott & Roen, 2012). Online outreach can serve as a valuable method for reaching hidden subpopulations of marginalized LGBTQ youth, and can be an effective method to engage youth with intersectional identities in discussions about mental health issues (McDermott & Roen, 2012).

Discussion

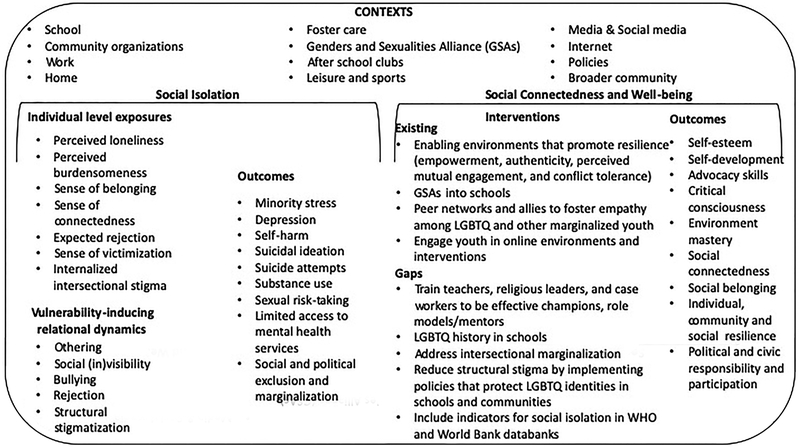

In this conceptual review, we described how social isolation and connectedness affect the well-being of LGBTQ youth. Figure 2 represents the psychosocial, relational, and contextual determinants of social isolation and connectedness, as well as gaps in the existing literature. Most of the evidence focuses on the psychosocial experience of social isolation. Research on psychosocial experiences was based primarily in the global North (n = 20), although a few studies were carried out in the global South (n= 5) (Asinelli-Luz & Cunha, 2011; Brandelli Costa et al., 2017; Chen, 2013; van Griensven et al., 2004; Yadegarfard et al., 2014). The minority stress model was the most commonly cited framework used to examine the effects of social isolation and mental health. Having higher levels of perceived loneliness, perceived burdensomeness, expected rejection, and perceptions of sexual stigma leads to negative mental health outcomes (Baams et al., 2015; Martin & D’Augelli, 2003; McConnell et al., 2015). These negative mental health and behavioural outcomes included substance use, sexual risk-taking behaviour, limited access to health services, depression, and suicidal ideation and attempts (Day et al., 2017; Hatzenbuehler et al., 2012). In contrast, having higher levels a perceived sense of connectedness and sense of belonging were found to be protective factors (Day et al., 2018). Although we identified a few studies that demonstrated that belonging to multiple marginalized identities increases psychosocial stress, these studies did not present potential solutions (i.e., programs and interventions) to address intersectional stigma (Fields et al., 2015; Fields, Morgan, & Sanders, 2016; Hatchel & Marx, 2018; Reed & Miller, 2016). This highlights the need for interventions to mitigate marginalization across multiple identities in order to reduce negative mental health outcomes. In addition, we identified the need to explore social class status as an additional level of exclusion that can further increase social isolation among LGBTQ youth.

Figure 2.

Psychosocial, Relational, and Contextual Determinants of Social Isolation and Connectedness Framework

The second major thematic area that emerged in our review was about the vulnerability-inducing relational dynamics that lead to social isolation and marginalization, including othering, social invisibility, and bullying. Four of the 15 studies on relational dynamics were carried out in the global South (Brown, 2017; Horton, 2014; Kowen & Davis, 2006; Seffner, 2013). This set of studies went beyond describing how individuals perceived or internalized psychosocial factors to focus on how social relationships are organized across different spaces and are shaped by policies. Being othered increases when individuals leave their cultural enclaves and engage in spaces where their identities are not well represented, resulting in differential access to important resources (Brown, 2017). According to the relational model of health, building relationships that have high levels of empowerment, authenticity, perceived mutual engagement, and conflict tolerance are necessary to inhibit negative mental health outcomes and behaviours due to othering (Gamarel et al., 2014). Youth in unstable living situations might prefer social invisibility to cope with discrimination of their LGBTQ identity (Ragg et al., 2006). Although some research has explored the effects of spatial isolation (e.g., rural and small-town location), the interaction of spatial isolation with racial/ethnic and LGBTQ identity-related marginalization has not been explored (Paceley, 2016). There needs to be an increase in the visibility of LGBTQ identities in rural areas to create safe spaces where youth are allowed to develop and grow into their identities. As the study conducted by Aerts et al. (2012) in Belgium indicates, ‘LGB friendly’ policies and curricula have positive effects for all students by generating an environment of belongingness. Programs that incorporate LGBTQ history in schools could address social invisibility and be effective in systemically building positive environments for healthy social relationships to develop among all students (Cerezo & Bergfeld, 2013; Palma, Piason, Manso, & Strey, 2015; Snapp, Burdge, Licona, Moody, & Russell, 2015).

Addressing social, cultural, and structural dimensions of social isolation emerge as critical to fostering enabling environments that allow LGBTQ youth to thrive. Increasing connectedness in multiple environments helps protect LGBTQ youth from negative mental health outcomes. Connectedness is defined in multiple contexts such the school, family, home, foster family, peer networks, and broader society. School anti-bullying polices that directly protect LGBTQ youth and broader policies that support LGBTQ people (e.g., those supporting same-sex marriage) have been shown to reduce the negative consequences of social isolation and promote collective, social well-being (Hatzenbuehler & Keyes, 2013). Schools that explicitly protect students with diverse sexual orientations on the list of included protections as part of their anti-bullying policies have youth with lower levels of suicide attempts (Hatzenbuehler & Keyes, 2013).

Interventions described in this literature target social isolation and connectedness in schools, community-based organizations, and in online environments. Studies based on positive youth development theories have promoted access to LGBTQ mentors, allies, and positive role models to reduce social isolation (Paceley, 2016). GSAs and online interventions help create positive LGBTQ spaces for youth to connect with peers and adults, discuss their experiences, and engage in advocacy (Lapointe, 2015; McDermott & Roen, 2012; Poteat & Scheer, 2016). In addition, teachers and advisors need to be trained to serve LGBTQ youth more effectively (Mello et al., 2012). Outside of the formal educational environment, LGBTQ-welcoming religious institutions and ‘families of choice’ are two social institutions in which interventions may serve isolated youth effectively (Etengoff & Daiute, 2015; Shilo et al., 2015). To counterbalance experiences with religious rejection, affirming churches have been a key source of social support throughout the world (Walker & Longmire-Avital, 2013). Similarly, youth who were rejected by their families often find alternative sources of social support and inclusion within queer families of choice – in which LGBTQ mentors provide the social connection, intergenerational guidance, and support that youth require for their development (Arnold & Bailey, 2009). Further research is necessary to support interventions that address social isolation by engaging youth in these environments (Wright-Maley, Davis, Gonzalez, & Colwell, 2016).

Interventions using online platforms are a growing area of research in LGBTQ health. Most interventions have focused on HIV prevention rather than on social isolation and well-being more broadly. Online, there is a high need for relevant LGBTQ information and for interventions that target bullying. Youth socially invisible in non-online environments will make their LGBTQ identities visible in select online spaces. Online safe spaces can serve as an effective strategy to engage youth in support networks to cope with issues affecting their mental health. Interventions that target ‘governance’ norms on online platforms with substantial use by LGBTQ youth (e.g., Tumblr, Facebook, Grindr, Whatsapp) may interrupt the reproduction of stigma, discrimination, social isolation, and cyberbullying, with special consideration for LGBTQ youth with intersectional identities (Duguay, Burgess, & Suzor, 2018; Kowalski, Limber, & McCord, 2018). LGBTQ health education conducted through online venues requires a reframing to focus on social well-being (and not focus solely on HIV and sexually transmitted infections) in order to contribute to positive community identity.

The existing literature focuses primarily on individual resilience, missing important social, community-based, and political dimensions of resilience (Hall & Lamont, 2013). Individual resilience is understood as a satisfactory outcome after an individual has been exposed to some factor that puts this outcome at risk. Broader dimensions of collective resilience describe the contexts in which individuals are enabled to thrive or that encourage the meaningful participation of communities in shaping their social environments. Few studies tried to capture these dimensions through constructs such as ‘environmental mastery’ (Detrie & Lease, 2007). Political resilience allows for groups that are isolated and marginalized to work together in solidarity, rather than reproducing oppression to compete for limited resources. This is particularly important when considering how relationships of power produce social isolation among youth who experience intersectional marginalization (e.g., LGBTQ and racial/ethnic minorities, low socioeconomic status, rural location, political minorities, migrant populations). A solidarity-based approach is critically necessary to shift cultural norms in which 1) identity-based conflicts generate tensions among different marginalized groups that in turn reproduce oppressive social norms, and 2) those holding several marginalized identities experience greater levels of social isolation at the intersection of marginalization (Smith, 2007; Hindman, 2011). Rather than singling out ‘at-risk’ youth, and intervening only at the individual-level, it will be important to develop interventions that aim to cultivate an environment in which youth with intersectional identities can generate solidarity to combat diverse forms of social isolation and oppression (McDermott & Roen, 2016).

This conceptual review has several broader implications for addressing social isolation among LGBTQ youth in response to global processes. First, it offers insights for interventions in the current stage of globalization, in which societies are growing more interconnected through faster, more accessible media (Bennett, 2012). At the same time, individuals experience fewer meaningful and personal interactions and greater exposure to marginalizing stimuli. Globalization has led to a generation of youth with a strong participatory culture, which values diversity, autonomy, and self-expression through a variety of accessible media (Jenkins, Itō, & Boyd, 2015). This virtual interconnectedness also presents the opportunity to engage youth who fear visibility (McDermott & Roen, 2012). Virtual networks may be used to breakdown boundaries between different global cultures through the flow of strategies for social resistance, mobilization, and transformation (Brettschneider, Burgess, & Keating, 2017). Second, there are epistemological differences emerging in the global North (e.g., focus on individual psychosocial outcomes and large quantitative samples) and the global South (e.g., the use of ethnography and qualitative methods to observe environments). These epistemologies could be combined through North-South and South-South collaboration that results in studies that 1) incorporate rigorous quantitative designs to analyse how individuals internalize their policy context, and 2) use ethnography and case studies to describe how social and cultural norms in environments (e.g., schools, churches, sports leagues, libraries, online) shape the participation of youth with multiple marginalized identities.

Third, addressing social isolation is fundamental to safeguarding the human rights of LGBTQ youth (Taylor & Peter, 2011). The human rights framework promotes the principles of equity, non-discrimination, and participation (Meier & Gostin, 2018). For this reason, global health governance institutions may consider including indicators for social isolation and connectedness among youth in their country-level assessments. A few United Nations committees with a commitment to the human rights of young people, such as the Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC), have considered information about LGBTQ children in their country-level reviews (Carroll & ILGA, 2016). In addition, the WHO’s constitution states:

The enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health is one of the fundamental rights of every human being without distinction of race, religion, political belief, economic or social condition […]

Healthy development of the child is of basic importance; the ability to live harmoniously in a changing total environment is essential to such development.

(WHO, 2014, p. 7)

Although the WHO describes how social isolation can be damaging for the mental health of older adults, putting them at risk for dementia (WHO, 2017, 2018, 2019), it has not considered isolation and connectedness in describing the health and welfare of young people. Global variation exists in terms of how sexual orientation and gender identity are supported or criminalised at the country level and within countries. Few studies have begun to examine how the policy context becomes internalized by LGBTQ youth, potentially resulting in adverse mental and physical health outcomes (Brown, 2017; Hatzenbuehler & Keyes, 2013). In its current efforts to mainstream human rights at the institutional level, the WHO should work to operationalise measures of social well-being that capture the individual, social, and structural dimensions of isolation experienced by LGBTQ youth. Such measures would facilitate cross-national comparisons to identify social factors that promote connectedness to the LGBTQ community. Studies may compare notions of resilience and collective well-being across individualistic and collectivist societies (Bie & Tang, 2016), as well as across secular and religious states. This conceptual review suggests that individual and social transformations are the result of young people’s meaningful participation in shaping their environment, which is made possible when their capabilities are fostered through social well-being. National and international policy contexts that enable human rights may facilitate health-promoting social connections.

Acknowledgements

Support for this research was provided in part by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of the Foundation. We thank Dr. Elizabeth King, who assisted in reviewing the Russian language document.

Contributor Information

Jonathan Garcia, Oregon State University, College of Public Health and Human Sciences.

Nancy Vargas, Oregon State University, College of Public Health and Human Sciences.

Jesse L. Clark, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Mario Magaña Álvarez, Oregon State University, College of Public Health and Human Sciences.

Devynne A. Nelons, Oregon State University, College of Public Health and Human Sciences.

Richard G. Parker, Associação Brasileira Interdisciplinar de AIDS (ABIA).

References

- Aerts S, Van Houtte M, Dewaele A, Cox N, & Vincke J (2012). Sense of belonging in secondary schools: A survey of LGB and heterosexual students in Flanders. Journal of Homosexuality, 59(1), 90–113. 10.1080/00918369.2012.638548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- António R, Guerra R, & Moleiro C (2017). Ter amigos com amigos gays/lésbicas? O papel do contacto alargado, empatia e ameaça nas intenções comportamentais assertivas dos bystanders. PSICOLOGIA, 31(2), 15 10.17575/rpsicol.v31i2.1138 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arksey H, & O’Malley L (2005). Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold EA, & Bailey MM (2009). Constructing home and family: how the ballroom community supports African American GLBTQ youth in the face of HIV/AIDS. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 21(2–3), 171–188. 10.1080/10538720902772006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asinelli-Luz A, & Cunha J. M. da. (2011). Percepções sobre a discriminação homofóbica entre concluintes do ensino médio no Brasil entre 2004 e 2008. Educar Em Revista, (39), 87–102. 10.1590/S0104-40602011000100007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baams L, Bos HMW, & Jonas KJ (2014). How a romantic relationship can protect same-sex attracted youth and young adults from the impact of expected rejection. Journal of Adolescence, 37(8), 1293–1302. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baams L, Grossman AH, & Russell ST (2015). Minority stress and mechanisms of risk for depression and suicidal ideation among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Developmental Psychology, 51(5), 688–696. 10.1037/a0038994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baiocco R, D’Alessio M, & Laghi F (2010). Binge drinking among gay, and lesbian youths: the role of internalized sexual stigma, self-disclosure, and individuals’ sense of connectedness to the gay community. Addictive Behaviors, 35(10), 896–899. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett WL (2012). The personalization of politics: political identity, social media, and changing patterns of participation. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 644(1), 20–39. 10.1177/0002716212451428 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bie B, & Tang L (2016). Chinese gay men’s coming out narratives: connecting social relationship to co-cultural theory. Journal of International and Intercultural Communication, 9(4), 351–367. 10.1080/17513057.2016.1142602 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Birkett M, Newcomb ME, & Mustanski B (2015). Does it get better? A longitudinal analysis of psychological distress and victimization in lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 56(3), 280–285. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.10.275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouris A, Guilamo-Ramos V, Pickard A, Shiu C, Loosier PS, Dittus P, … Michael Waldmiller J (2010). A systematic review of parental influences on the health and well-being of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth: time for a new public health research and practice agenda. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 31(5–6), 273–309. 10.1007/s10935-010-0229-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandelli Costa A, Pasley A, Machado W de L, Alvarado E, Dutra-Thomé L, & Koller SH (2017). The experience of sexual stigma and the increased risk of attempted suicide in young Brazilian people from low socioeconomic group. Frontiers in Psychology, 8 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brettschneider M, Burgess S, & Keating C (Eds.). (2017). LGBTQ Politics: A critical reader. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown A (2017). ‘Sometimes people kill you emotionally’: policing inclusion, experiences of self-identified homosexual youth in secondary schools in Namibia. African Identities, 15(3), 339–350. 10.1080/14725843.2017.1319751 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll A, & ILGA. (2016). State-sponsored homophobia: a world survey of sexual orientation laws. Retrieved September 4, 2019, from https://ilga.org/downloads/02_ILGA_State_Sponsored_Homophobia_2016_ENG_WEB_150516.pdf

- Cerezo A, & Bergfeld J (2013). Meaningful LGBTQ inclusion in schools: the importance of diversity representation and counterspaces. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 7(4), 355–371. 10.1080/15538605.2013.839341 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen I-C (2013). Loneliness of homosexual male students: parental bonding attitude as a moderating factor. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 16, E71 10.1017/sjp.2013.55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coast E, Norris AH, Moore AM, & Freeman E (2018). Trajectories of women’s abortion-related care: a conceptual framework. Social Science & Medicine, 200, 199–210. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.01.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day JK, Fish JN, Perez-Brumer A, Hatzenbuehler ML, & Russell ST (2017). Transgender youth substance use disparities: results from a population-based sample. Journal of Adolescent Health, 61(6), 729–735. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.06.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day JK, Perez-Brumer A, & Russell ST (2018). Safe schools? Transgender youth’s school experiences and perceptions of school climate. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47(8), 1731–1742. 10.1007/s10964-018-0866-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detrie PM, & Lease SH (2007). The relation of social support, connectedness, and collective self-esteem to the psychological well-being of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Journal of Homosexuality, 53(4), 173–199. 10.1080/00918360802103449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewaele A, Van Houtte M, Cox N, & Vincke J (2013). From coming out to visibility management—A new perspective on coping with minority stressors in LGB youth in Flanders. Journal of Homosexuality, 60(5), 685–710. 10.1080/00918369.2013.773818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFulvio GT (2011). Sexual minority youth, social connection and resilience: from personal struggle to collective identity. Social Science & Medicine, 72(10), 1611–1617. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.02.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duguay S, Burgess J, & Suzor N (2018). Queer women’s experiences of patchwork platform governance on Tinder, Instagram, and Vine. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 135485651878153 10.1177/1354856518781530 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duong J, & Bradshaw C (2014). Associations between bullying and engaging in aggressive and suicidal behaviors among sexual minority youth: The moderating role of connectedness. The Journal of School Health, 84(10), 636–645. 10.1111/josh.12196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg ME, & Resnick MD (2006). Suicidality among gay, lesbian and bisexual youth: the role of protective factors. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 39(5), 662–668. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.04.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espelage DL, Merrin GJ, & Hatchel T (2018). Peer victimization and dating violence among LGBTQ youth: the impact of school violence and crime on mental health outcomes. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 16(2), 156–173. 10.1177/1541204016680408 [DOI] [Google Scholar]