Abstract

Background

Diabetes exacerbates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion (MI/R) injury by incompletely understood mechanisms. Adipocyte dysfunction contributes to remote organ injury. However, the molecular mechanisms linking dysfunctional adipocytes to increased MI/R injury remain unidentified. The current study attempted to clarify whether and how small extracellular vesicles (sEV) may mediate pathological communication between diabetic adipocytes and cardiomyocytes, exacerbating MI/R injury.

Methods

Adult male mice were fed a normal or a high fat diet for 12 weeks. sEV (from diabetic serum, diabetic adipocytes, or high glucose/high lipid (HG/HL)-challenged non-diabetic adipocytes) were injected intramyocardially distal of coronary ligation. Animals were subjected to MI/R 48 hours after injection.

Results

Intramyocardial injection of diabetic serum sEV in the non-diabetic heart significantly exacerbated MI/R injury, as evidenced by poorer cardiac function recovery, larger infarct size, and greater cardiomyocyte apoptosis. Similarly, intramyocardial or systemic administration of diabetic adipocyte sEV or HG/HL-challenged non-diabetic adipocyte sEV significantly exacerbated MI/R injury. Diabetic epididymal fat transplantation significantly increased MI/R injury in non-diabetic mice, whereas administration of a sEV biogenesis inhibitor significantly mitigated MI/R injury in diabetic mice. Mechanistic investigation identified that miR-130b-3p is a common molecule significantly increased in diabetic serum sEV, diabetic adipocyte sEV, and HG/HL-challenged non-diabetic adipocyte sEV. Mature (but not primary) miR-130b-3p was significantly increased in the diabetic and non-diabetic heart subjected to diabetic sEV injection. Whereas intramyocardial injection of a miR-130b-3p mimic significantly exacerbated MI/R injury in non-diabetic mice, miR-130b-3p inhibitors significantly attenuated MI/R injury in diabetic mice. Molecular studies identified AMPKα1/α2, Birc6, and Ucp3 as direct downstream targets of miR-130b-3p. Overexpression of these molecules (particularly AMPKα2) reversed miR-130b-3p induced pro-apoptotic/cardiac harmful effect. Finally, miR-130b-3p levels were significantly increased in plasma sEV from type 2 diabetic patients. Incubation of cardiomyocytes with diabetic patient sEV significantly exacerbated ischemic injury, an effect blocked by miR-130b-3p inhibitor.

Conclusion

We demonstrate for the first time that miR-130b-3p enrichment in dysfunctional adipocyte-derived sEV, and its suppression of multiple anti-apoptotic/cardioprotective molecules in cardiomyocytes, is a novel mechanism exacerbating MI/R injury in the diabetic heart. Targeting miR-130b-3p mediated pathological communication between dysfunctional adipocytes and cardiomyocytes may be a novel strategy attenuating diabetic exacerbation of MI/R injury.

Keywords: Diabetes, Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury, Extracellular Vesicles, micro-RNA, Apoptosis

INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with diabetes, a disease affecting 23.6 million people in the United States. Obesity, hyperglycemia, and hyperlipidemia are the most common metabolic disorders identified in diabetes, and are established cardiovascular risk factors1. However, strict glycemic control in recent large-scale clinical trials failed to demonstrate cardiovascular mortality benefit in diabetic patients2, 3. Novel strategies capable of protecting the diabetic heart against exacerbated myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury (MI/R) are urgently needed4, 5.

Research in the past decade has increased understanding of the role adipocytes play in health and disease1. Now recognized as the largest endocrine organ, adipocytes produce a wide range of hormones and cytokines regulating remote organ functions6. Accumulating evidence suggests that visceral adipocyte dysfunction significantly affects the development/progression of type 2 diabetes and diabetic cardiovascular complications1, 7. Complete understanding of the molecular mechanisms responsible for the roles diabetic adipocytes play in cardiac pathophysiology will help identify novel effective therapy against MI/R injury in diabetic individuals.

Extracellular vesicles (EV) are systemic messengers delivering the signaling molecules mediating intercellular and inter-organ communication. Exosomes and microvesicles, of different biogenesis pathways and collectively known as the small EVs (sEV), are two of the most important EV types8, 9. Recent studies demonstrate that adipocytes are a major source of sEV-containing miRNA in circulation. Among 653 detectable miRNAs in serum sEV, 419 are significantly reduced in fat-specific DicerKO mice, with 88% reduced by more than four fold10. More importantly, dysfunctional adipocyte sEV in obesity/diabetes promote remote organ pathologic remodeling11–15. However, it has not been previously investigated whether and how diabetes may alter adipocyte-derived sEV, exacerbating MI/R injury. Enhancing our understanding of adipocyte sEV in cardiac pathology will advance comprehension of the mechanisms responsible for increased diabetic patient mortality after MI, and facilitate identification of novel therapeutic targets reducing MI mortality in diabetes.

Utilizing in vitro molecular mechanistic investigation and in vivo proof of concept, we provide the first evidence that sEV carry miR-130b-3p from dysfunctional adipocytes to the heart, suppressing multiple anti-apoptotic/cardioprotective molecules, and exacerbating MI/R injury. Targeting miR-130b-3p mediated pathologic communication between dysfunctional adipocytes and cardiomyocytes may be a novel strategy attenuating diabetic exacerbation of MI/R injury.

METHODS

All animal study experiments adhered to the National Institutes of Health Guidelines on the Use of Laboratory Animals, and were approved by the Thomas Jefferson University Committee on Animal Care. Human study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of West China Hospital (Chengdu, China). 40 patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) and 40 healthy control were recruited in Department of Endocrinology from August to October 2019 (Table 1 in the online-only Data Supplement). All participants were Han nationality. Written informed consent was obtained prior to study inclusion. The fasting plasma samples were collected and stored at −80°C. Materials, experiment procedures, data collection protocols, and analytic methods will be made available to other researchers as requested for purposes of experiment reproduction, procedural replication, and for collaborative study. Detailed Materials and Methods are presented in the online-only Data Supplement.

Statistical analysis

Data are reported as means ± SD. For analysis of differences between two groups, unpaired student’s t test was performed. For multiple groups, Data were analyzed by one-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Tukey’s, Dunnett’s or Sidak’s multiple comparisons test (details in Figure legends). For all statistical tests, p values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed via Graphpad Prism 7. The Statistical analysis of clinical and biochemical characteristics of the subjects involved in the human study were performed via IBM Spss 25. The analysis of gender between two groups was using Pearson’s chi-squared test. The Shapiro-Wilk statistic was used to test the normality of the other characteristics’ values. If the values were followed normal distribution, the independent sample t-test was used. Otherwise, the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test was used.

RESULTS

1. Diabetic adipocyte-derived sEV exacerbated MI/R-injury in non-diabetic mice

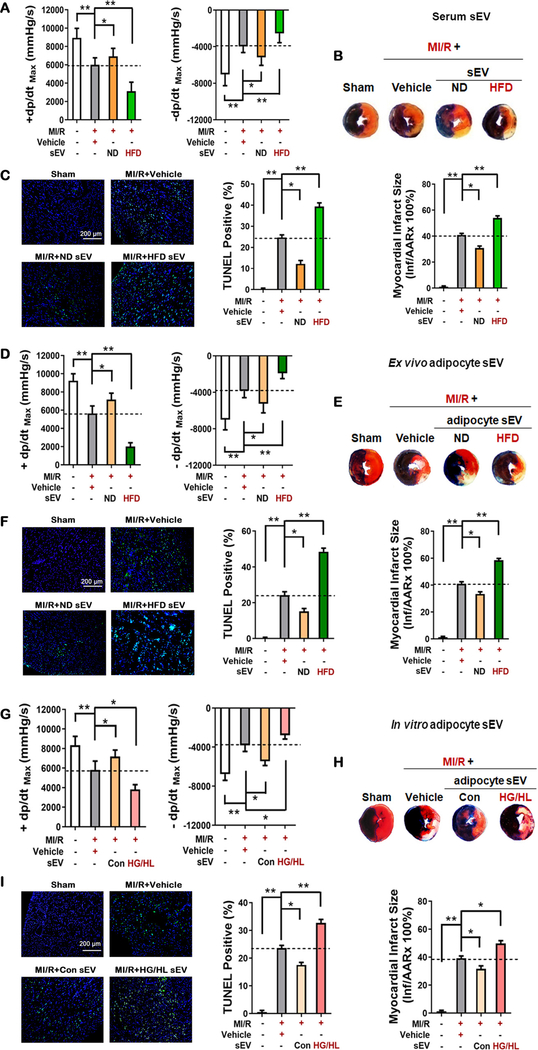

Circulating sEV was isolated from the sera of age-matched male mice fed normal (ND) and high fat diet (HFD) by ultracentrifugation. Vesicles were approximately <300 nm in diameter, positive for CD81, and exhibit sEV characteristics under transmission electron microscopy (Figure 1A–D in the online-only Data Supplement). To determine whether sEV released by HFD tissue may adversely impact MI/R injury, sEV from 200 μl serum (diluted in 20μl PBS) were injected into the left anterior ventricle wall of ND mice at three different sites distal of anticipated coronary ligation. Control animals were injected the same volume of PBS (Vehicle). 48 hours after sEV injection, mice were subjected to MI/R. Compared to vehicle, intramyocardial injection of HFD serum sEV significantly exacerbated MI/R injury in ND mice, as evidenced by poor cardiac function recovery (±dP/dtmax 48% and 36% decreased compared to Vehicle group (p<0.01), larger infarct size (32% larger than Vehicle group, p<0.01), and greater apoptotic death (59% more TUNEL positive cells compared to Vehicle group, p<0.01, Figure 1A–C). To determine whether observed cardiac deleterious effects were caused by serum sEV injection, sEV were isolated from ND animals and injected to ND heart in identical fashion. Interestingly, intramyocardial injection of ND serum sEV exerted opposite effect of HFD serum sEV, reducing MI/R injury (Figures 1A–C). These results indicated that serum sEV from obese/diabetic mice increased MI/R injury.

Figure 1. Deleterious effects of adipocyte sEV derived from obese/diabetic mice in MI/R-injury.

48 hours after sEV intramyocardial injection, mice were subjected to MI/R. (A, D, G) 24 hours after reperfusion, cardiac function was evaluated by hemodynamic testing (n≥15). (B, E, H) Cardiac injury was identified by myocardial Evans blue/TTC double stain (n≥8). (C, F, I) 3 hours after reperfusion, cardiomyocyte apoptosis was determined by TUNEL assay (n=8). (All experiment groups were compared to MI/R+Vehicle group via One-way ANOVA, *p<0.05, **p<0.01) Abbreviations: MI/R, myocardial ischemia/reperfusion; sEV, small extracellular vesicles; ND, normal diet; HFD, high fat diet; HG/HL, high glucose and high lipid administration.

To obtain more evidence that diabetic adipocyte-derived sEV exacerbated diabetic MI/R injury, six additional in vivo and in vitro experiments were performed. First, to determine the specific role of HFD adipocyte sEV, primary adipocytes were isolated from epididymal white adipose tissue (eWAT) of ND or HFD animals. The adipocyte-derived sEV were purified from culture medium 24 hours later (Figure 1E–H in the online-only Data Supplement) by ultracentrifugation and intramyocardially injected. Pharmacokinetic experiments demonstrated that intramyocardially injected adipocyte sEV were quickly internalized by cardiomyocytes, accumulating significantly within 24 hours, and decreased 48 hours after injection (Figure 1I in the online-only Data Supplement). These results are consistent with a previous report about breast cancer-derived exosomes16. Compared to MI/R+Vehicle group, HFD-derived adipocyte sEV administration decreased ±dP/dtmax 64% and 50% respectively (Figure 1D). Moreover, HFD-derived adipocyte sEV administration increased cardiac infarct (43% larger than Vehicle group) and apoptosis (100% greater than Vehicle group), evidenced by Evans blue/TTC double staining and TUNEL assay (Figure 1E and F). In contrast, injection of ND adipocyte sEV significantly decreased MI/R injury in the non-diabetic heart. To further determine whether circulating adipocyte-derived sEV gain access to the myocardium and exacerbate MI/R injury, the sEV from HFD animals were administered to ND animals by tail-vein injection in a 1:1 ratio (i.e., total sEV from 1 HFD epididymal white adipose tissue were intravenously administered to 1 ND mouse). Experimental results demonstrated that circulating sEV were taken up by cardiomyocytes (Figure 1J in the online-only Data Supplement) and exacerbated MI/R injury (Figure 2 in the online-only Data Supplement).

Second, mature adipocytes constitute >90% of adipose tissue volume17. Metabolic disorder is the hallmark of type 2 diabetes18. To determine the specific roles of sEV released by metabolically stressed adipocytes, primary adipocytes from ND mice were cultured in normal glucose/normal lipid (control) or high glucose/high lipid (HG/HL) culture medium for 48 hours. sEV were purified by ultracentrifugation, intramyocardially injected, and their effect upon MI/R injury was determined. Control adipocyte sEV modestly improved +dp/dtmax. However, HG/HL adipocyte sEV significantly increased MI/R injury (Figure 1G–I).

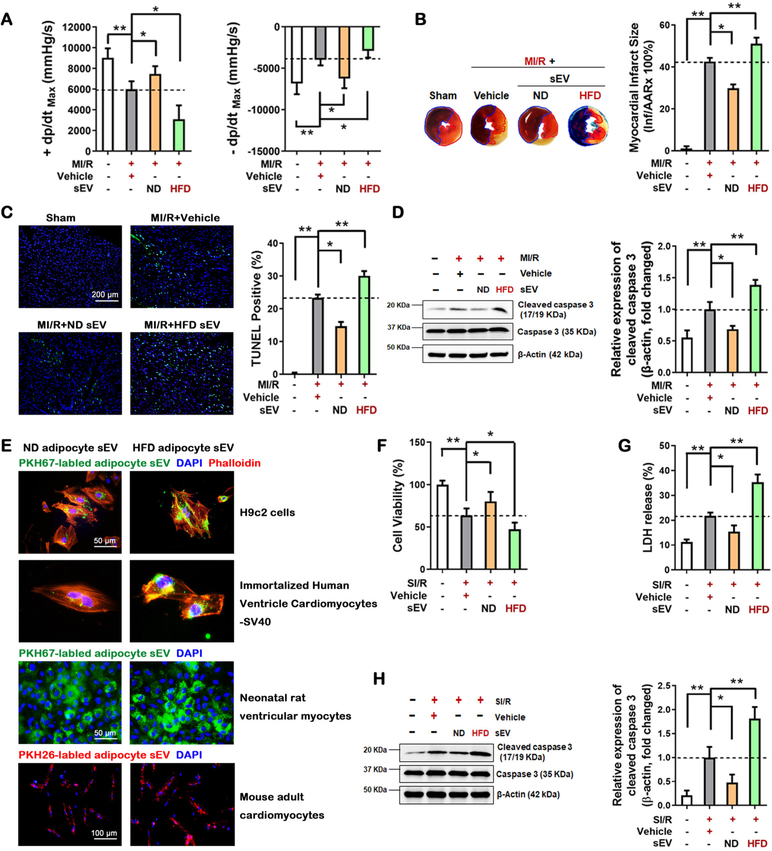

Third, diabetes may alter the quantity, size, and composition of adipocyte sEV, all factors that may contribute to MI/R injury. To determine the specific role of altered sEV composition upon HFD MI/R injury, 2×108 ND adipocyte sEV or HFD adipocyte sEV were purified by ultracentrifugation and intramyocardially injected into non-diabetic mice prior to MI/R. Injection of equal numbers of ND or HFD adipocyte-derived sEV exerted opposite effects upon MI/R injury. HFD adipocyte sEV significantly decreased cardiac function (Figure 2A), increased infarct size (Figure 2B), and increased cardiomyocyte apoptosis (Figure 2C and D).

Figure 2. The content shift of HFD adipocyte sEV was responsible for MI/R injury exacerbation.

48 hours after tantamount sEV intramyocardial injection, mice were subjected to MI/R. 24 hours after reperfusion. (A) cardiac function was evaluated by hemodynamic testing (n≥15). (B) Cardiac injury was identified by myocardial Evans blue/TTC double stain (n=8). (C, D) 3 hour after reperfusion, cardiomyocyte apoptosis was determined by (C) TUNEL assay (n=8) and (D) cleaved caspase-3 assay by Western blot (n=5). (E) In vitro adipocyte sEV uptaken analysis. PKH67-labled or PKH26-labled adipocyte sEV were harvested from primary adipocyte culture medium, and subsequently incubated with H9c2 cells, human cardiomyocytes, and adult mouse cardiomyocytes for 6 hours. (F) Neonatal rat ventricular myocyte (NRVM) cell viability was evaluated by MTT assay in vitro with adipocyte sEV plus simulated ischemia/reoxygenation (SI/R) administration (simulated ischemia 6 hours and reoxgenation 3 hours, n=5). (G) Cell death was determined by LDH release (n=5). (H) Cell apoptosis was determined by cleaved caspase-3 assay by Western blot (n=5). (All experiment groups were compared to MI/R+Vehicle group via One-way ANOVA, *p<0.05, **p<0.01).

Fourth, we determined the direct effects of HFD adipocyte sEV upon simulated ischemia/reoxygenation (SI/R)-induced cellular death. Adipocyte sEV were significantly internalized into cardiomyocytes (Figure 2E), and HFD adipocyte sEV incubation exacerbated SI/R-induced neonatal rat ventricular myocyte (NRVM) death (Figures 2F–H).

Fifth, the epididymal white adipose tissue (eWAT) harvested from HFD-fed mice and ND-fed mice were transplanted into ND-fed mice deprived of eWAT. Consistent with previous reports10, 19, HFD eWAT replacement resulted in significant body weight increase and systemic insulin resistance 14 days after surgery (Figure 3A and B in the online-only Data Supplement). More importantly, compared to ND eWAT replacement, HFD eWAT replacement significantly increased MI/R injury, most significantly impairing dP/dtmax (Figure 3A–D).

Figure 3. Deleterious effects of dysfunctional adipose tissue and systemic sEV from HFD-fed mice in MI/R-injury.

(A-D) The epididymal adipose tissues (eWAT) were isolated from HFD mice or ND donor mice, and transplanted into 8-week-old male non-diabetic recipient mice removed epidydimal fat depots. 7 days after eWAT transplantation, MI/R was performed. (E-H) The HFD-fed mice were intraperitoneal injected GW4869 (2 mg/kg) or vehicle 3 times a week for 12 weeks. Then, MI/R was performed. (A, E) Cardiac function was evaluated by hemodynamic testing (n≥15). (B, F) Cardiac injury was identified by myocardial Evans blue/TTC double stain (n≥8). Cardiomyocyte apoptosis was determined by (C, G) TUNEL assay (n=8) and (D, H) cleaved caspase-3 assay by Western blot (n=5). (All experiment groups were compared to MI/R+ ND eWAT group or MI/R+Vehicle group via upaired t-test, *p<0.05, **p<0.01). Abbreviation: eWAT, epididymal white adipose tissue.

Sixth, GW4869 (a widely-used sEV biogenesis inhibitor) was intraperitoneally administered 3 times a week during the feeding period20. As expected, serum sEV levels were markedly decreased by GW4869 in HFD-fed mice (Figure 3F in the online-only Data Supplement), and the body weight and plasma glucose levels in IP GTT and IP ITT tests were also restored by GW4869 in HFD-fed mice (Figure 3C and D in the online-only Data Supplement). GW4869 administration significantly augmented cardiac function after MI/R, increasing ±dP/dtmax by 34% and 28% (compared to vehicle group, Figure 3E). GW4869 administration reduced cardiac infarct size (39% reduction by Evans blue/TTC double staining analysis, Figure 3F), inhibited cardiomyocyte apoptosis (41% by TUNEL assay, Figure 3G), and decreased cleaved caspase-3 (36% by western blot, Figure 3H) in HFD-fed obese/diabetic mice subjected to MI/R.

Taken together, these results provide clear evidence that the sEV released by diabetic adipocytes exacerbate MI/R injury.

2. Identification of miR-130b-3p as the sEV-containing molecule mediating cardiotoxicity

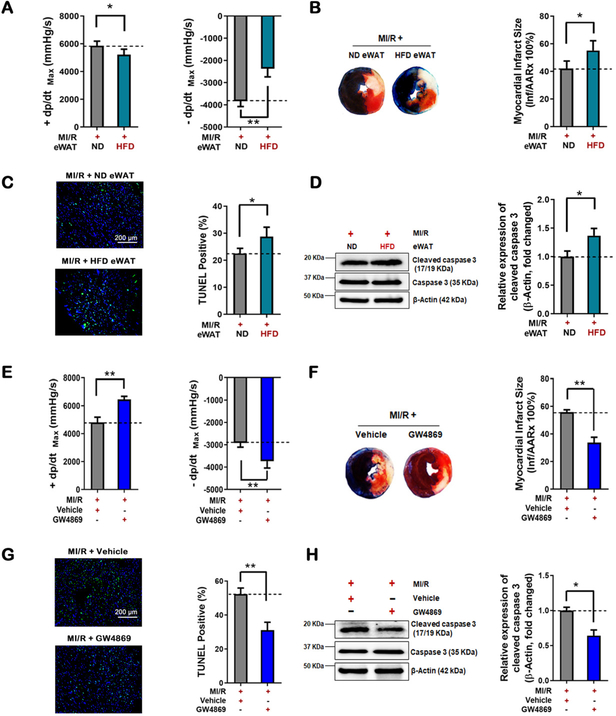

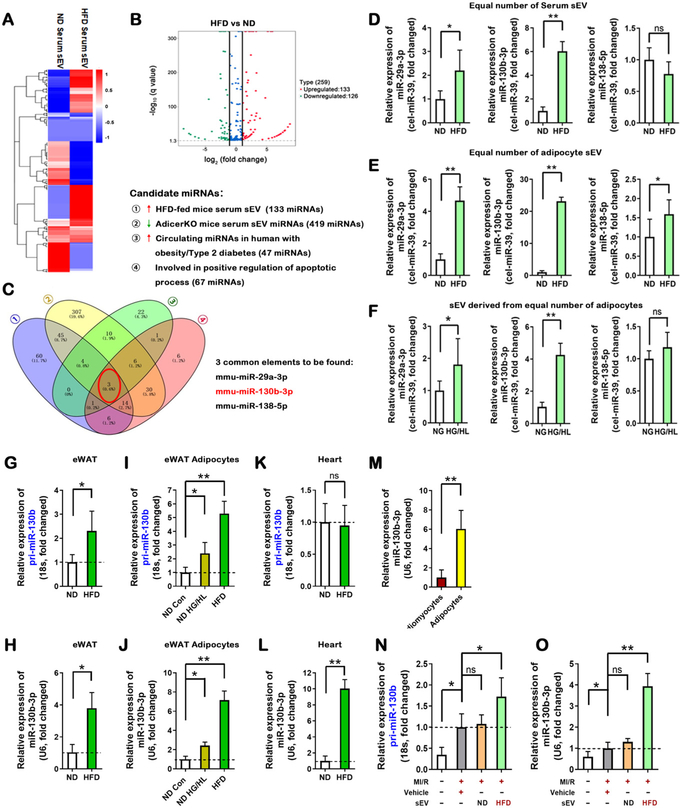

Although sEV carry various signaling molecules involved in cell-cell communication, increasing evidence suggests that miRNAs are the most important molecules by which sEV regulate recipient cell function10, 21. Cardiomyocyte apoptosis (programmed cell death) is promoted by diabetes22, and is one of the most significant driving forces initiating other pathologic remodeling (including necroptosis, excess autophagic death, and cardiac fibrosis) in acute MI/R23–26. We therefore reasoned that identification of the miRNAs responsible for the pro-apoptotic effect of HFD adipocyte sEV may yield consequent novel therapeutic value. Five series of experiments were performed. First, ND or HFD serum sEV were purified by ultracentrifugation. Sera from 10 mice/group (approximately 4 mL) were mixed together and sEV were purified. The sEV-containing small RNAs were extracted and analyzed by deep RNAseq (each sample included the genetic information from 10 mice). Global miRNA profiling revealed upregulation of 133 miRNAs and downregulation of 126 miRNAs in HFD serum sEV (filtering criteria, p<0.05, fold change >2.0. Figure 4A and B) compared to ND serum sEV. To predict sEV-containing miRNAs potentially promoting cardiomyocyte apoptosis, miRNAs significantly increased in HFD serum sEV were analyzed against three miRNA databases: miRNAs elevated in diabetic human serum27–29, miRNAs highly enriched in adipocytes10, and miRNAs positively regulating apoptosis (Diana tools database GO:0043065). Venn overlap analysis identified 3 common miRNAs, including miR-29a-3p, miR-130b-3p, and miR-138–5p (Figure 4C). Importantly, none of these miRNAs are cardiac enriched.

Figure 4. Increased miR-130b-3p present in HFD adipocyte sEV.

(A, B) Differentially expressed miRNAs were selected from sequencing data of serum sEV miRNAs, shown in (A) and (B). (C) Venn analysis selected three candidate miRNAs satisfying four conditions. (D, E) The relative expression of three mature miRNAs in equal numbers of serum sEV and eWAT adipocyte sEV. (F) The relative expression of three mature miRNAs, in adipocyte sEV derived from the same number of adipocytes (n=6, unpaired t-test, *p<0.05, **p<0.01). (G, H) The relative expression of pri-miR-130b and mature miR-130b-3p in eWAT from ND-fed and HFD-fed mice (12 weeks), analyzed by real-time PCR. (I, J) The relative expression of pri-miR-130b and mature miR-130b-3p in eWAT adipocytes from ND-fed and HFD-fed mice, or ND adipocytes treated with HG/HL, analyzed by real-time PCR. (K, L) The relative expression of pri-miR-130b and mature miR-130b-3p in heart tissue from ND-fed and HFD-fed mice, analyzed by real-time PCR. (M) The relative expression of miR-130b-3p in cardiomyocytes and adipocytes. (N, O) The relative expression of pri-miR-130b and mature miR-130b-3p in cardiac tissue +/− adipocyte sEV intramyocardial injection, analyzed by real-time PCR. (All n≥5, unpaired t-test and One-way ANOVA, *p<0.05, **p<0.01,). Abbreviations: ns, not statistically significant.

Second, serum sEV and adipocyte-derived sEV were purified as above. The miRNA expression was determined by miScript PCR System. Of the 3 pro-apoptotic miRNAs identified from HFD sEV, 1) miR-138–5p expression was unchanged in serum sEV, 2) miR-29a-3p was modestly increased in HFD adipocyte sEV and HG/HL adipocyte sEV (Figure 4D–F), and 3) a >20-fold (Figure 4E) and >4-fold (Figure 4F) increase of miR-130b-3p was respectively observed in HFD adipocyte sEV and HG/HL adipocyte sEV. miR-130b-3p belongs to miRNA cluster 25, which includes miR-130b-3p and miR-301b-3p. Interestingly, miR-301b-3p was unchanged in diabetic serum sEV, HFD adipocyte sEV, HG/HL adipocyte sEV (Figure 4 in the online-only Data Supplement), or diabetic patient serum27–29, suggesting miR-301b-3p is not involved in HFD adipocyte sEV-exacerbated MI/R injury.

Third, to evaluate whether mature cardiac miR-130b-3p is of adipose origin, both primary and mature miR-130b-3p were detected simultaneously in adipose and heart tissue by real-time qPCR. Both primary and mature miR-130b-3p were upregulated in HFD eWAT tissue (Figures 4G and 4H), HFD eWAT adipocytes, and HG/HL-challenged adipocytes (Figures 4I and 4J). However, mature (but not primary) miR-130b-3p was markedly increased in HFD cardiac tissue (Figures 4K and 4L). The mature miR-130b-3p was highly expressed in adult mouse adipocytes compared to cardiomyocytes (Figure 4M). Additionally, intramyocardial injection of HFD adipocyte sEV significantly increased cardiac tissue levels of mature miR-130b-3p (Figures 4N and 4O).

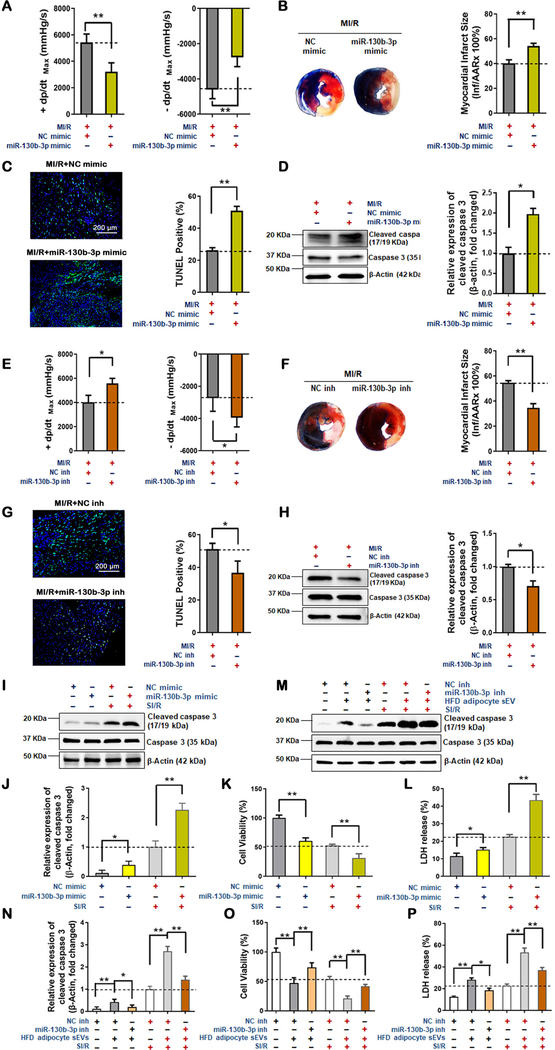

Fourth, to establish a causative relationship between miR-130–3p and MI/R injury, gain- and loss-of-function experiments were performed. A miR-130b-3p mimic and its negative control (NC) were intramyocardially injected into the left ventricle of ND animals prior to MI/R. Hemodynamic analysis revealed the miR-130b-3p mimic significantly decreased systolic/diastolic function (Figure 5A). Consistent with cardiac function analysis, both infarct size and cardiomyocyte apoptosis were significantly increased (Figure 5B–D). Conversely, HFD-exacerbated MI/R-injury (Figure 5 in the online-only Data Supplement) was attenuated by administration of miR-130b-3p inhibitors (miR-130b-3p inh) (Figure 5E–H, and Figure 6 in the online-only Data Supplement).

Figure 5. Deleterious effects of miR-130b-3p upon MI/R-injury in obese/diabetic mice and in cultured cells.

(A-D) miR-130b-3p increased MI/R-injury in non-diabetic mice. 48 hours after miR-130b-3p mimic and NC mimic transfection of the myocardium of non-diabetic mice, MI/R commenced. 24 hours after reperfusion, cardiac function was evaluated by hemodynamic testing (A, n=15, unpaired t-test, *p<0.05, **p<0.01). Cardiac injury was identified by myocardial Evans blue/TTC double stain (B, n=5); cardiomyocyte apoptosis was determined by TUNEL assay (C, n=8) and cleaved caspase-3 assay by Western blot (D, n=5). (E-H) miR-130b-3p-antagonism reduced MI/R-injury in obese/diabetic mice. 48 hours after miR-130b-3p inhibitor (miR-130b-3p inh) and NC inhibitor (NC inh) transfection of the myocardium of HFD-fed mice, MI/R commenced. 24 hours after reperfusion, cardiac function were evaluated by hemodynamic testing (E, n=15, unpaired t-test, *p<0.05, **p<0.01). Cardiac injury was identified by myocardial Evans blue/TTC double stain (F, n=5); cardiomyocyte apoptosis was determined by TUNEL assay (G, n=8) and cleaved caspase-3 assay by Western blot (H, n=5). (Unpaired t-test, *p<0.05, **p<0.01). miR-130b-3p activated cardiomyocyte apoptosis in vitro. Expression of cleaved caspase-3 (I and J), cell viability (K) and LDH release (L) was detected in NRVM cells transfected by mimics of miR-130b-3p or NC for 24 hours and received SI/R administration. Expression of cleaved caspase-3 (M and N), cell viability (O) and LDH release (P) in NRVM cells overexpressing miR-130b-3p inhibitor before HFD adipocyte sEV + SI/R administration. The cells were transfected with miR-130b-3p inh or NC inh 24 hours before HFD adipocyte sEV treatment, and then subjected to SI/R performance 24 hours after HFD adipocyte sEV treatment. (n≥5, One-way ANOVA, *p<0.05, **p<0.01)

Finally, we determined whether miR-130b-3p exerts direct harmful effect upon cardiomyocytes. Transfection of a miR-130–3p mimic significantly exacerbated SI/R-induced NRVM cell death (Figures 5I–L). In contrast, HFD adipocyte sEV-induced cell death was rescued by a miR-130b-3p inhibitor (Figures 5M–P).

Identification of AMPKα as a novel miR-130b-3p target mediating its pro-apoptotic effect

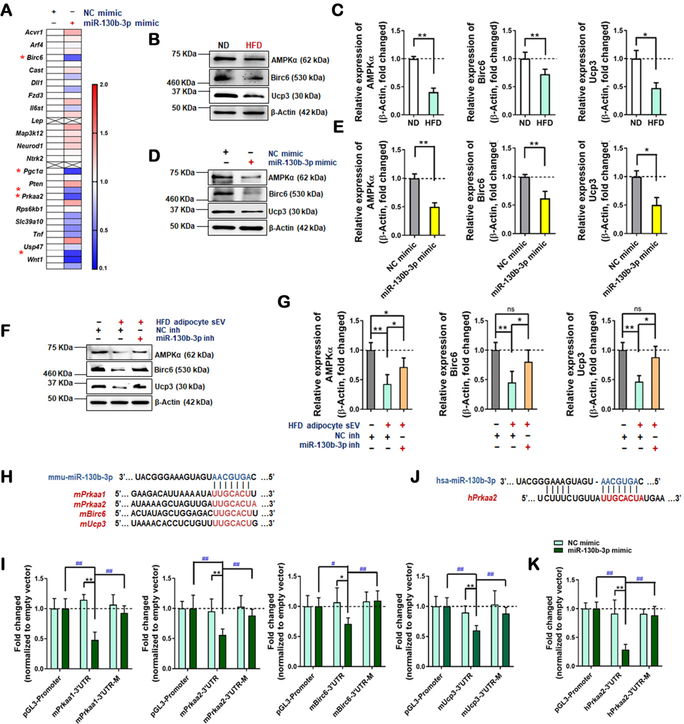

Recent animal and clinical epidemiologic studies highlight the role of miR-130b-3p in adipocyte biology and obesity/diabetes30–34. However, the role of miR-130b-3p in cardiovascular physiology and pathophysiology is largely unexplored. Ppargc1a (Pgc1a) and Pparg, two genes critically involved in metabolic regulation, are confirmed direct target genes of miR-130b-3p35–37. To identify novel miR-130b-3p target genes that may directly promote cardiomyocyte apoptosis and exacerbate MI/R injury, bioinformatic analyses were first performed. Among 1,753 mouse and 2,097 human genes predicted to be potential miR-130b-3p targets (found in at least three of the following five databases: miRWalk, miRanda, miRDB, RNA22, and Targetscan), 687 were shared between mouse and human (Figure 7 in the online-only Data Supplement). DAVID Functional Annotation Bioinformatics Microarray Analysis (version 6.7) predicted the involvement of 37 of 687 potential miR-130b-3p targeting genes in negative regulation of apoptosis. To validate the predicted targets, a miR-130b-3p mimic was intramyocardially injected. The expression of these 37 genes in cardiac tissue was determined. RT-qPCR demonstrated that, in addition to Pgc1a (previously confirmed as a miR-130b-3p target), Prkaa1 (AMPKα1), Prkaa2 (AMPKα2), Birc6, and Ucp3 are the top 4 (previously unreported) genes significantly reduced in the miR-130b-3p mimic-injected heart (Figure 6A).

Figure 6. miR-130b-3p decreased expression of AMPKα and downstream molecules.

(A) Real-time PCR analysis detected expressions of the predicted targets of miR-130b-3p involved in negative regulation of apoptosis in heart tissue with or without miR-130b-3p administration (n=3, multiple unpaired t-test, *p<0.05, **p<0.01) (B and C) Proteins levels were detected by Western blot in cardiac tissue from ND-fed and HFD-fed mice (n=5, unpaired t-test, *p<0.05, **p<0.01). (D and E) Proteins levels were detected in NRVM cells +/− miR-130b-3p mimic or NC mimic (n=5, unpaired t-test, *p<0.05, **p<0.01). (F and G) Protein levels were detected in NRVM cells overexpressing miRNA inhibitors before HFD adipocyte sEV administration. The cells were transfected with miR-130b-3p inh or NC inh 24 hours before HFD adipocyte sEV treatment, and 24 hours after HFD adipocyte sEV treatment, the protein levels were detected. (n=9, One-way ANOVA, *p<0.05, **p<0.01) (H and I) The direct effects of miR-130b-3p upon mouse AMPKα1/2, Birc6, and Ucp3 were identified by reporter gene analysis. (J and K) The direct effects of miR-130b-3p upon human AMPKα2 were identified by reporter gene analysis. The reported plasmids containing the gene mRNA 3’UTR regions (including binding sites) are shown in E and G (mutated binding sites were reverse in sequence). NRVM cells or HEK cells were cotransfected by the miRNA mimics and reporter plasmids for 48 hours. The regulatory effects were evaluated by firefly/renilla luciferase activity. Fold-change was calculated by dividing the value of firefly/renilla luciferase activity in each group transfected with miR-130b-3p mimic by the value obtained from the group transfected with the same reporter constructs and NC mimic. The empty vector (pGL3-Promoter) transfected group served as control, and its value was set as 1.0 (n≥6, two-way ANOVA, comparisons to NC mimic group, *p<0.05, **p<0.01; for mutated reporter plasmid and miR-130b-3p mimic values compared to groups with normal reporter plasmid transfection + miR-130b-3p mimic, #p<0.05, ##p<0.01).

To obtain direct evidence that the downregulation of these genes is responsible for the pro-apoptotic effect of miR-130b-3p, several experiments were performed. First, the protein expression levels of these miR-130b-3p target genes in ND- and HFD-fed heart were determined. The protein levels of AMPKα, Birc6, and Ucp3 were all significantly reduced in HFD-fed mice (Figure 6B and C). Second, miR-130b-3p mimic transfection significantly reduced protein expression of AMPKα, Birc6, and Ucp3 (Figure 6D and E) in NRVM cells. Third, incubation of NRVM cells with HFD adipocyte sEV (Figure 6F and G) significantly inhibited AMPKα, Birc6, and Ucp3 expression, an effect reversed by miR-130b-3p inhibitor transfection. Fourth, to obtain direct evidence that Prkaa1/2, Birc6, and Ucp3 are the direct downstream targets of miR-130b-3p, luciferase assay was performed in NRVM cells transfected with plasmids containing predicted miR-130b-3p-binding sites in 3’ untranslated regions (UTR) (Figure 6H). The miR-130b-3p mimic significantly downregulated luciferase activity in cells expressing wild type genes. This was not true if the binding sites in the 3’UTR of these genes were mutated (Figure 6I). As the binding sites of miR-130b-3p in human and mouse Prkaa2 3’UTR are not conserved (Figure 6J), the reporter plasmids containing human predicted binding sites and reverse sequences were transfected into HEK293 cells. The luciferase activity in the upstream of hPrkaa2 3’UTR were inhibited by overexpressing miR-130b-3p mimic, and the inhibitory effect was abolished when the binding sites were mutated (Figure 6K).

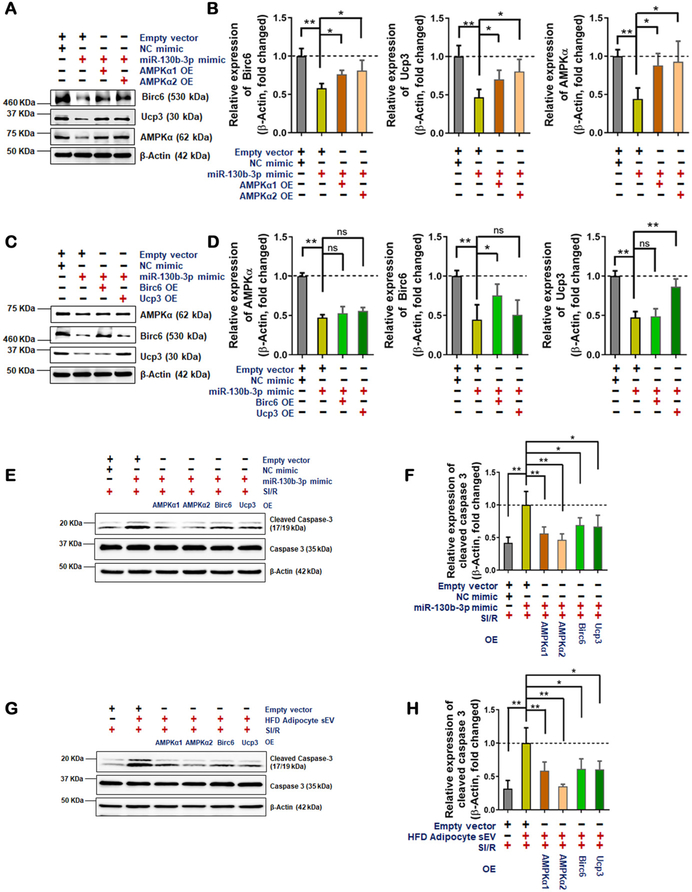

It is well-recognized that AMPKα is a master regulator of metabolic disorder-induced cellular dysfunction and cell death. Moreover, HO-1, Ucp2, Nrf2, Birc6, and Ucp3 are all reported downstream anti-oxidative/cell survival molecules. Having demonstrated that AMPKα is a novel miR-130b-3p target gene, we performed additional experiments to determine the role of AMPKα in miR-130b-3p and HFD adipocyte sEV-induced cell death. First, miR-130b-3p mimic (Figure 8A and B in the online-only Data Supplement) or HFD adipocyte sEV (Figure 8C and D in the online-only Data Supplement) significantly inhibited AMPK activation in NRVM cells. Moreover, the expression of HO-1, Ucp2, and Nrf2 was significantly decreased in NRVM cells treated with miR-130b-3p mimic or HFD adipocyte sEV. Conversely, miR-130b-3p inhibitor restored AMPK activity and its downstream molecule expression in HFD adipocyte sEV-treated NRVM cells (Figure 8 in the online-only Data Supplement). Second, AMPKα1/2 overexpression reversed miR-130b-3p mimic-suppressed expression of Birc6 and Ucp3 in NRVM cells (Figure 7A and B). However, Birc6 or Ucp3 overexpression failed to rescue miR-130b-3p mimic-suppressed expression of AMPKα (Figure 7C and D). These results indicate that miR-130b-3p suppresses Birc6 or Ucp3 expression by direct means (via target genes) as well as indirect mechanisms (via suppression of AMPKα and its downstream signaling). Finally, to validate the role of HFD adipocyte sEV-containing miR130b-3p targeting genes in apoptotic cell death, AMPKα1/2, Birc6, and Ucp3 were individually overexpressed in NRVM cells. Their effect upon miR-130b-3p mimic- and HFD sEV-exacerbated oxidative cell death was determined. Overexpressing miR-130b-3p target genes significantly decreased miR-130b-3p mimic- (Figure 7E and F) and HFD adipocyte sEV-induced (Figure 7G and H) cell death in SI/R-treated NRVM cells. Of the 4 miR-130b-3p target genes, AMPKα2 overexpression exhibited the best protection against miR-130b-3p mimic and HFD adipocyte sEV-induced cell death.

Figure 7. miR-130b-3p-mediated AMPKα downregulation contributed to the cardiomyocyte apoptosis induced by HFD adipocyte sEV.

(A and B) AMPKα1 and AMPKα2 overexpression restored the Birc6 and Ucp3 protein levels in NRVM cells with miR-130b-3p mimic administration. (C and D) Birc6 and Ucp3 overexpression did not restored the AMPKα protein levels in NRVM cells with miR-130b-3p mimic administration. (n=5, One-way ANOVA, comparisons to empty vector + miR-130b-3p mimic group *p<0.05, **p<0.01) (E-H) AMPKα1/2, Birc6 and Ucp3 overexpression downregulated miR-130b-3p mimic + SI/R administration-induced (E and F) or HFD adipocyte sEV + SI/R administration-induced (G and H) cleaved caspase3 expression. Western blot detected protein levels in NRVM cells with plasmid-mediated exogenous genes infusion after miR-130b-3p mimic transfection or HFD adipocyte sEV administration. 24 hours after miRNA mimic transfection or sEV administration, the plasmids were transfected. 24 hours later, SI/R was performed. Plasmids overexpressed AMPKα1/2, Birc6 and Ucp3. Empty vector + miR-130b-3p mimic transfected group with SI/R treatment served as control, and its value was set at 1.0. (n=5, One-way ANOVA, *p<0.05, **p<0.01)

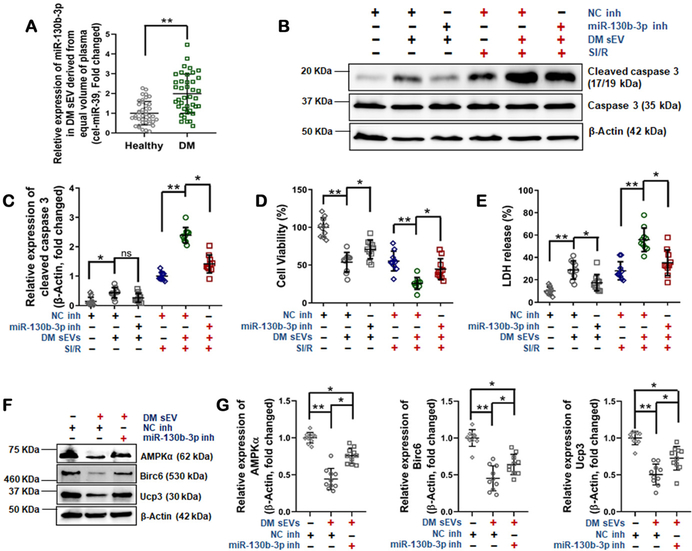

sEV from type 2 diabetic patient promote cardiomyocyte death, an effect attenuated by miR-130b-3p inhibition

As a final step to confirm the translational potential of our experimental findings, sEV were isolated from type 2 diabetic patients and gender/age-matched controls (Table 3 in the online-only Data Supplement). sEV miR-130b-3p levels and their effect upon SI/R-induced cardiomyocyte death were determined. As summarized in Figure 8A, miR-130B-3p was significantly increased in sEV from diabetic patient plasma (DM sEV) compared to healthy controls. Importantly, treatment with sEV purified from diabetic patients significantly exacerbated SI/R-induced NRVM cell death, an effect attenuated by a miR-130b-3p inhibitor (Figures 8B–E). Finally, incubation of NRVM cells with sEV purified from diabetic patients significantly inhibited AMPKα, Birc6, and Ucp3 expression, an effect reversed by miR-130b-3p inhibitor transfection (Figures 8F/G).

Figure 8.

Plasma sEV from diabetic patients promoted SI/R-induced NRVM apoptosis. (A) miR-130b-3p expression in plasma sEV derived from patients with type 2 diabetes (DM sEV) and healthy controls (n=40, unpaired t-test, *p<0.05, **p<0.01). (B-E) DM sEV exacerbated SI/R-induced NRVM death, an effect attenuated by overexpressing miR-130b-3p inhibitor (B/C: cleaved caspase-3; D: cell viability; E: LDH release). (n=10/group, One-way ANOVA, *p<0.05, **p<0.01). (F and G) DM sEV inhibited AMPKα1/2, Birc6, and Ucp3 expression, an effect reversed by overexpressing miR-130b-3p inhibitor. (n=10, One-way ANOVA, *p<0.05, **p<0.01).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we have made three novel findings. First, we provide the first evidence that sEV mediate the pathologic communication between dysfunctional adipose tissue and the heart, exacerbating MI/R injury. Of the various extracellular vesicles, exosomes (30–150 nm) and microvesicles (50–1,000 nm) are the most extensively investigated10, 21. As current ultracentrifugation technology precludes the simple separation of exosomes and microvesicles, sEV is the accepted term describing this highly heterogeneous EV population9. Despite their discovery decades ago, sEV have only recently been identified to play an important role in cell-to-cell communications38, 39. sEV importantly regulates cardiovascular physiology and pathophysiology, including diabetic cardiomyopathy and MI/R injury40, 41. More importantly, dysfunctional adipocyte sEV in obesity/diabetes promote remote organ pathologic remodeling, including inflammatory cytokine release11, systemic insulin resistance11–13, liver TGFβ pathway dysregulation14, and cancer cell metastasis42. The regulatory functions of adipocyte sEV upon the cardiovascular system have also been recently recognized; sEV from PPARγ function-inhibited adipocytes attenuate cardiac hypertrophy15, whereas sEV from diabetic animals exacerbate atherosclerosis13. Our current study provides several lines of evidence strongly supporting diabetic exacerbation of MI/R injury by adipocyte-derived sEV. Intramyocardial injection of diabetic serum sEV, diabetic adipocyte sEV, and HG/HL-challenged adipocyte sEV, or intravenous injection of diabetic adipocyte sEV significantly increased MI/R injury in the non-diabetic heart. In contrast, systemic administration of a sEV biogenesis inhibitor during diabetes development decreased MI/R injury. Moreover, utilizing an accepted fat transplantation approach, we demonstrated that transplantation of diabetic epididymal fat tissue to the non-diabetic heart significantly increased MI/R injury. Finally, we demonstrated that intramyocardial injection of equal numbers of ND adipocyte sEV decreased MI/R injury, an opposite effect observed with diabetic adipocyte sEV, a result suggesting that HFD-induced diabetes alters adipocyte-derived sEV from a friendly cardioprotective transporter to a dangerous vessel carrying cardiotoxic cargo. These novel results advance comprehension of the mechanisms responsible for increased diabetic patient mortality after MI, and aid identification of novel therapeutic targets reducing MI mortality in diabetes.

Second, we identified that miR-130b-3p is the most important molecule mediating diabetic adipocyte sEV pro-apoptotic effect. Although sEV contain proteins and lipids, they are highly enriched in non-coding RNAs, particularly miRNAs. sEV miRNA content varies dramatically per origin cell type, but does not merely parrot the miRNA profile of the donor cell40, 43. Certain miRNAs are preferentially enriched in sEV. Our discovery-driven experiment demonstrates that diabetes dramatically alters serum sEV composition. Combining in vivo, in vitro, and bio-informatic approaches, we demonstrate that miR-130b-3p is a common molecule significantly increased in HFD serum sEV, HFD adipocyte sEV, HG/HL-challenged adipocyte sEV, and diabetic patient serum32, 33. Moreover, we demonstrated that premature and mature forms of miR-130b-3p were significantly increased in HFD visceral adipose tissue. However, mature (but not premature) miR-130b-3p was significantly increased in the HFD heart. Finally, and most importantly, whereas intramyocardial injection of miR-130b-3p mimic significantly increased MI/R injury in the non-diabetic heart, miR-130b-3p inhibitor administrations attenuated MI/R injury in the diabetic heart. Recent animal and clinical epidemiologic studies highlight the role of miR-130b-3p in cancer biology and obesity/diabetes30–34. Its role in cardiovascular physiology and pathophysiology remains largely unexplored. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first reporting the critical role of miR-130b-3p with respect to myocardial apoptosis and post-MI cardiac injury. These results provide the experimental foundation for therapeutic application of anti-miR-130b-3p against MI/R injury, particularly during diabetes.

Third, Pgc1a and Pparg are direct target genes of miR-130b-3p. miR-130b-3p exerts its metabolic regulatory role largely by inhibiting these genes35–37. Utilizing bioinformatic analysis, followed by multiple in vivo and in vitro experimental validations, we identified several novel miR-130b-3p target genes and demonstrated their role in diabetic adipocyte sEV-induced cardiomyocyte death. Among the newly discovered miR-130b-3p targets, AMPKα inhibition by miR-130b-3p likely plays the most significant pathologic role. This conclusion is supported by the work of others and the results provided herein. AMPK is a master molecular regulator in metabolic disorder related cell death and organ injury44–47. AMPKα inhibition causes diabetic cardiomyopathy and diabetic cardiac death48. Conversely, therapeutic strategies activating AMPKα protect the heart against diabetic cardiac injury. Our current study demonstrated that, although Birc6 and Ucp3 are novel miR-130b-3p targets, they are also downstream molecules regulated by AMPKα. AMPKα overexpression rescued miR-130b-3p and diabetic adipocyte sEV-induced Birc6 and Ucp3 suppression. Moreover, although overexpression of each of the novel target genes of miR-130b-3p reduced miR-30b-3p and diabetic adipocyte sEV-induced cell death, AMPKα2 overexpression exerted the most significant protective action, underlining AMPKα downregulation by miR-130b-3p, carried by diabetic adipocyte sEV. Strong clinical and experimental results demonstrate that both AMPK and AMPK-initiated signaling are significantly impaired in the diabetic condition. Whereas the molecular mechanisms ultimately leading to diabetic suppression of AMPK remain unclear, our study provides a novel explanatory mechanism: miR-130b-3p, carried by diabetic adipocyte sEV, negatively regulates AMPKα expression directly. Importantly, as diabetes suppresses AMPK in multiple organs (e.g. heart, liver, muscle, and kidney), the identification of a molecular mechanism upstream of AMPK carries broad implications in the realm of diabetic organ injury.

Several important questions will be addressed in our future studies. Intramyocardial injection of non-diabetic adipocyte sEV significantly attenuated MI/R injury. The molecular mechanisms responsible for this observed cardioprotection, as well as those responsible for the diabetic phenotypic switch, warrant future investigation. Diabetes modified adipocyte sEV content, number, and size. Whether and how such pathologic alterations may contribute to diabetic cardiac injury were not addressed in the current study. Despite both belonging to miRNA cluster 25, miR-130b-3p was selectively upregulated in sEV by diabetes, whereas miR-301b-3p was unchanged. The basis for this important difference requires additional investigation. Finally, diabetes is a systemic disease adversely influencing MI/R injury by complex pathologic mechanisms. The current study evaluated the effect of metabolically stressed adipocyte-derived sEV upon post-MI cardiac apoptosis, recognizing miR-130b-3p as an important pathologic mediator. The molecular identity of sEV produced by other cellular types in diabetic tissue, impacted by other pathologic stresses, influencing other cellular pathology in MI/R injury, all must be clarified to fully understand the molecular mechanisms by which dysfunctional adipose tissue contributes to diabetic cardiovascular complications. It needs to be noted that currently available sEV isolation methods all co-isolate lipoproteins to some degree9. The possible contamination and likely influence of lipoproteins upon sEV cardiac effect should be determined when better sEV isolation methods become available.

In summary, we identified adipocyte sEV as a novel mediator exacerbating acute ischemic/reperfusion-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis in obesity/diabetes (Figure 9 in the online-only Data Supplement). These results suggest that preventing abnormal adipocyte sEV production, blocking miR-130b-3p biogenesis, or administering a miR-130b-3p antagonist may be novel effective therapeutic interventions blocking sEV-mediated pathologic communications between dysfunctional adipose tissue and the heart, providing cardioprotection against diabetic injury.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Perspective.

What Is New?

This study provides the first evidence that sEV mediate the pathologic communication between dysfunctional adipose tissue and the heart, exacerbating ischemic heart injury in obesity/diabetes.

This study demonstrates that miR-130b-3p is the most important molecule mediating diabetic adipocyte sEV pro-apoptotic effect.

This study identifies AMPK as a novel miR-130b-3p target, revealing a novel mechanism via which diabetes inhibits AMPK expression and disturbing cellular metabolism.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Strategies preventing or blocking abnormal adipocyte sEV production may have great potential protection against ischemic heart injury in obesity/diabetes.

Detecting circulating sEV-carried miR-130b-3p expression extent may predict the degree of heart damage and prognosis in obesity/diabetes.

Strategies blocking miR-130b-3p biogenesis or administration of miR-130b-3p antagonist may provide cardioprotection against diabetic injury.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

pECE HA AMPKa1 WT and pECE-HA-AMPKalpha2 WT plasmids were gifts from Dr. Anne Brunet (Addgene plasmid # 69504 and 31654). pcNDA3 myc-Birc6 plasmid was a gift from Dr. Mikihiko Naito (National Institute of Health Sciences, Tokyo, Japan).

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This work was supported by awards from the National Institutes of Health (HL-96686 and HL-123404, X. Ma) and the American Diabetes Association (1-14-BS-218, Y. Wang).

Non-standard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- EV

Extracellular Vesicles

- sEV

Small Extracellular Microvesicles

- MI/R

Myocardial Ischemia/Reperfusion

- DM

Diabetes Mellitus

- T2DM

Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

- ND

Normal Diet

- HFD

High Fat Diet

- HG/HL

High Glucose/High Lipid

- eWAT

Epididymal White Adipose Tissue

- NRVM

Neonatal Rat Ventricular Myocyte

- NC

Negative Control

- APN

Adiponectin

- ns

not statistically significant

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

None

REFERENCES

- 1.Oikonomou EK and Antoniades C. The role of adipose tissue in cardiovascular health and disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2019;16:83–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mazzone T Intensive Glucose Lowering and Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Diabetes: Reconciling the Recent Clinical Trial Data. Circulation. 2010;122:2201–2211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duckworth W, Abraira C, Moritz T, Reda D, Emanuele N, Reaven PD, Zieve FJ, Marks J, Davis SN, Hayward R, Warren SR, Goldman S, McCarren M, Vitek ME, Henderson WG and Huang GD. Glucose control and vascular complications in veterans with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:129–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katayama T, Nakashima H, Takagi C, Honda Y, Suzuki S, Iwasaki Y and Yano K. Clinical outcomes and left ventricular function in diabetic patients with acute myocardial infarction treated by primary coronary angioplasty. Int Heart J. 2005;46:607–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ansley DM and Wang B. Oxidative stress and myocardial injury in the diabetic heart. J Pathol. 2013;229:232–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scherer PE. The many secret lives of adipocytes: implications for diabetes. Diabetologia. 2019;62:223–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Icli B and Feinberg MW. MicroRNAs in dysfunctional adipose tissue: cardiovascular implications. Cardiovasc Res. 2017;113:1024–1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mathieu M, Martin-Jaular L, Lavieu G and Thery C. Specificities of secretion and uptake of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles for cell-to-cell communication. Nat Cell Biol. 2019;21:9–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sluijter JPG, Davidson SM, Boulanger CM, Buzas EI, de Kleijn DPV, Engel FB, Giricz Z, Hausenloy DJ, Kishore R, Lecour S, Leor J, Madonna R, Perrino C, Prunier F, Sahoo S, Schiffelers RM, Schulz R, Van Laake LW, Ytrehus K and Ferdinandy P. Extracellular vesicles in diagnostics and therapy of the ischaemic heart: Position Paper from the Working Group on Cellular Biology of the Heart of the European Society of Cardiology. Cardiovasc Res. 2018;114:19–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomou T, Mori MA, Dreyfuss JM, Konishi M, Sakaguchi M, Wolfrum C, Rao TN, Winnay JN, Garcia-Martin R, Grinspoon SK, Gorden P and Kahn CR. Adipose-derived circulating miRNAs regulate gene expression in other tissues. Nature. 2017;542:450–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kranendonk ME, Visseren FL, van Balkom BW, Nolte-’t Hoen EN, van Herwaarden JA, de Jager W, Schipper HS, Brenkman AB, Verhaar MC, Wauben MH and Kalkhoven E. Human adipocyte extracellular vesicles in reciprocal signaling between adipocytes and macrophages. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2014;22:1296–1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deng ZB, Poliakov A, Hardy RW, Clements R, Liu C, Liu Y, Wang J, Xiang X, Zhang S, Zhuang X, Shah SV, Sun D, Michalek S, Grizzle WE, Garvey T, Mobley J and Zhang HG. Adipose tissue exosome-like vesicles mediate activation of macrophage-induced insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2009;58:2498–2505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xie Z, Wang X, Liu X, Du H, Sun C, Shao X, Tian J, Gu X, Wang H, Tian J and Yu B. Adipose-Derived Exosomes Exert Proatherogenic Effects by Regulating Macrophage Foam Cell Formation and Polarization. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e007442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koeck ES, Iordanskaia T, Sevilla S, Ferrante SC, Hubal MJ, Freishtat RJ and Nadler EP. Adipocyte exosomes induce transforming growth factor beta pathway dysregulation in hepatocytes: a novel paradigm for obesity-related liver disease. J Surg Res. 2014;192:268–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fang X, Stroud MJ, Ouyang K, Fang L, Zhang J, Dalton ND, Gu Y, Wu T, Peterson KL, Huang HD, Chen J and Wang N. Adipocyte-specific loss of PPARgamma attenuates cardiac hypertrophy. JCI Insight. 2016;1:e89908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wen SW, Sceneay J, Lima LG, Wong CS, Becker M, Krumeich S, Lobb RJ, Castillo V, Wong KN, Ellis S, Parker BS and Moller A. The Biodistribution and Immune Suppressive Effects of Breast Cancer-Derived Exosomes. Cancer Res. 2016;76:6816–6827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eto H, Suga H, Matsumoto D, Inoue K, Aoi N, Kato H, Araki J and Yoshimura K. Characterization of structure and cellular components of aspirated and excised adipose tissue. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:1087–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boden G and Laakso M. Lipids and glucose in type 2 diabetes: what is the cause and effect? Diabetes Care. 2004;27:2253–2259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foster MT, Shi H, Seeley RJ and Woods SC. Transplantation or removal of intra-abdominal adipose tissue prevents age-induced glucose insensitivity. Physiol Behav. 2010;101:282–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lallemand T, Rouahi M, Swiader A, Grazide MH, Geoffre N, Alayrac P, Recazens E, Coste A, Salvayre R, Negre-Salvayre A and Auge N. nSMase2 (Type 2-Neutral Sphingomyelinase) Deficiency or Inhibition by GW4869 Reduces Inflammation and Atherosclerosis in Apoe(−/−) Mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2018;38:1479–1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ying W, Riopel M, Bandyopadhyay G, Dong Y, Birmingham A, Seo JB, Ofrecio JM, Wollam J, Hernandez-Carretero A, Fu W, Li P and Olefsky JM. Adipose Tissue Macrophage-Derived Exosomal miRNAs Can Modulate In Vivo and In Vitro Insulin Sensitivity. Cell. 2017;171:372–384 e12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frustaci A, Kajstura J, Chimenti C, Jakoniuk I, Leri A, Maseri A, Nadal-Ginard B and Anversa P. Myocardial cell death in human diabetes. Circ Res. 2000;87:1123–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sciarretta S, Boppana VS, Umapathi M, Frati G and Sadoshima J. Boosting autophagy in the diabetic heart: a translational perspective. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2015;5:394–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boudina S and Abel ED. Diabetic cardiomyopathy, causes and effects. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2010;11:31–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gill C, Mestril R and Samali A. Losing heart: the role of apoptosis in heart disease--a novel therapeutic target? FASEB J. 2002;16:135–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abbate A, Biondi-Zoccai GG and Baldi A. Pathophysiologic role of myocardial apoptosis in post-infarction left ventricular remodeling. J Cell Physiol. 2002;193:145–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Santovito D, De Nardis V, Marcantonio P, Mandolini C, Paganelli C, Vitale E, Buttitta F, Bucci M, Mezzetti A, Consoli A and Cipollone F. Plasma exosome microRNA profiling unravels a new potential modulator of adiponectin pathway in diabetes: effect of glycemic control. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:E1681–E1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deiuliis JA. MicroRNAs as regulators of metabolic disease: pathophysiologic significance and emerging role as biomarkers and therapeutics. Int J Obes (Lond). 2016;40:88–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parrizas M and Novials A. Circulating microRNAs as biomarkers for metabolic disease. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;30:591–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen W, Zhao W, Yang A, Xu A, Wang H, Cong M, Liu T, Wang P and You H. Integrated analysis of microRNA and gene expression profiles reveals a functional regulatory module associated with liver fibrosis. Gene. 2017;636:87–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Demirsoy IH, Ertural DY, Balci S, Cinkir U, Sezer K, Tamer L and Aras N. Profiles of Circulating MiRNAs Following Metformin Treatment in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. J Med Biochem. 2018;37:499–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang YC, Li Y, Wang XY, Zhang D, Zhang H, Wu Q, He YQ, Wang JY, Zhang L, Xia H, Yan J, Li X and Ying H. Circulating miR-130b mediates metabolic crosstalk between fat and muscle in overweight/obesity. Diabetologia. 2013;56:2275–2285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lv C, Zhou YH, Wu C, Shao Y, Lu CL and Wang QY. The changes in miR-130b levels in human serum and the correlation with the severity of diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2015;31:717–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leone V, Langella C, Esposito F, De Martino M, Decaussin-Petrucci M, Chiappetta G, Bianco A and Fusco A. miR-130b-3p Upregulation Contributes to the Development of Thyroid Adenomas Targeting CCDC6 Gene. Eur Thyroid J. 2015;4:213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jiang S, Teague AM, Tryggestad JB and Chernausek SD. Role of microRNA-130b in placental PGC-1alpha/TFAM mitochondrial biogenesis pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;487:607–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gu JJ, Zhang JH, Chen HJ and Wang SS. MicroRNA-130b promotes cell proliferation and invasion by inhibiting peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma in human glioma cells. Int J Mol Med. 2016;37:1587–1593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen Z, Luo J, Ma L, Wang H, Cao W, Xu H, Zhu J, Sun Y, Li J, Yao D, Kang K and Gou D. MiR130b-Regulation of PPARgamma Coactivator- 1alpha Suppresses Fat Metabolism in Goat Mammary Epithelial Cells. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0142809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gartz M and Strande JL. Examining the Paracrine Effects of Exosomes in Cardiovascular Disease and Repair. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2018;7:e007954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Khan M and Kishore R. Stem Cell Exosomes: Cell-FreeTherapy for Organ Repair. Methods Mol Biol. 2017;1553:315–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ibrahim A and Marban E. Exosomes: Fundamental Biology and Roles in Cardiovascular Physiology. Annu Rev Physiol. 2016;78:67–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang X, Gu H, Huang W, Peng J, Li Y, Yang L, Qin D, Essandoh K, Wang Y, Peng T and Fan GC. Hsp20-Mediated Activation of Exosome Biogenesis in Cardiomyocytes Improves Cardiac Function and Angiogenesis in Diabetic Mice. Diabetes. 2016;65:3111–3128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lazar I, Clement E, Dauvillier S, Milhas D, Ducoux-Petit M, LeGonidec S, Moro C, Soldan V, Dalle S, Balor S, Golzio M, Burlet-Schiltz O, Valet P, Muller C and Nieto L. Adipocyte Exosomes Promote Melanoma Aggressiveness through Fatty Acid Oxidation: A Novel Mechanism Linking Obesity and Cancer. Cancer Res. 2016;76:4051–4057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xu JY, Chen GH and Yang YJ. Exosomes: A Rising Star in Falling Hearts. Front Physiol. 2017;8:494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zou MH and Xie Z. Regulation of interplay between autophagy and apoptosis in the diabetic heart: new role of AMPK. Autophagy. 2013;9:624–625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang Y, Tao L, Yuan Y, Lau WB, Li R, Lopez BL, Christopher TA, Tian R and Ma XL. Cardioprotective effect of adiponectin is partially mediated by its AMPK-independent antinitrative action. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;297:E384–E391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dyck JRB and Lopaschuk GD. AMPK alterations in cardiac physiology and pathology: enemy or ally? The Journal of Physiology Online. 2006;574:95–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shibata R, Sato K, Pimentel DR, Takemura Y, Kihara S, Ohashi K, Funahashi T, Ouchi N and Walsh K. Adiponectin protects against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury through AMPK- and COX-2-dependent mechanisms. Nat Med. 2005;11:1096–1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Daskalopoulos EP, Dufeys C, Beauloye C, Bertrand L and Horman S. AMPK in Cardiovascular Diseases. Exp Suppl. 2016;107:179–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.