Abstract

Despite growing evidence of significant racial disparities in the experience and treatment of chronic pain, the mechanisms by which these disparities manifest have remained relatively understudied. The current study examined the relationship between past experiences of racial discrimination and pain-related outcomes (self-rated disability and depressive symptomatology) and tested the potential mediating roles of pain catastrophizing and perceived injustice related to pain. Analyses consisted of cross-sectional path modeling in a multiracial sample of 137 individuals with chronic low back pain (Hispanics: n = 43; blacks: n = 43; whites: n = 51). Results indicated a positive relationship between prior discriminatory experiences and severity of disability and depressive symptoms. In mediation analyses, pain-related appraisals of injustice, but not pain catastrophizing, were found to mediate these relationships. Notably, the association between discrimination history and perceived injustice was significantly stronger in black and Hispanic participants and was not statistically significant in white participants. The findings suggest that race-based discriminatory experiences may contribute to racial disparities in pain outcomes and highlight the specificity of pain-related, injustice-related appraisals as a mechanism by which these experiences may impair physical and psychosocial function. Future research is needed to investigate temporal and causal mechanisms suggested by the model through longitudinal and clinical intervention studies.

Keywords: Racial discrimination, chronic low back pain, injustice perception, pain catastrophizing, disability

The pain literature documents notable racial/ethnic disparities in chronic pain experience and care.1,25 Individuals identifying as black/African American endorse more frequent and disabling pain across a number of conditions compared to other racial groups, most notably Whites.1,25 With respect to low back pain—the leading cause of pain and disability in the United States—research in the area of Workers’ Compensation highlights racial disparities in evaluation, treatment, and litigation outcomes of work-related lower back injuries9,10,12,13 with blacks showing long-term vulnerability to greater pain intensity, catastrophizing, emotional distress, financial stress,9,11 and future disability.9

Experiences of discrimination reliably predict worse mental and physical health outcomes.5,45,46,70 Perceived discrimination is defined as perception of negative race-or ethnicity-related attitudes, judgments, or unfair treatment toward members of a group2,21,33,70 and is viewed as one way by which racism generates stress.69 Indirect evidence suggests that black pain patients experience more discrimination—they are more often referred to urine drug tests and substance abuse specialists,5 denied early prescription renewals,4 receive care less responsive to meaningful contextual information including the presenting problem, objective findings, and facial expressions,28 and have briefer face-to-face interactions with (white) providers.3,31,32 Studies likewise highlight a positive association between perceived discrimination and pain experience among black and other minority participants.8,17,23,26,36,62 However, despite research showing robust associations between discrimination and health outcomes,5,45,46 exact mechanisms underlying these associations remain unclear.5

Perceived injustice and pain catastrophizing have emerged as key psychosocial contributors to negative pain-related outcomes18,39,55,58; both reflect cognitive appraisals of pain experience and both show differences between black and white individuals. Perception of injustice, an appraisal reflecting the severity and irreparability of pain-/injury-/disability-related loss, blame, and unfairness,39,40,58,60 predicts poor outcomes in both acute and chronic pain populations.39,58 Black patients admitted to inpatient trauma care reported significantly higher injury-related injustice appraisals than white counterparts63; this finding was replicated in patients with chronic low back pain (CLBP).64,65 Similarly, pain catastrophizing, defined as an “exaggerated cognitive and affective reaction to an expected or actual pain experience”61 is consistently linked to greater pain intensity, disability, emotional distress, and physical dysfunction.18,22,55,68 Given evidence of higher pain catastrophizing among black individuals,11,64 both injustice and catastrophic appraisals have been posited as potential mechanisms explaining racial differences in pain outcomes.10 Notably, despite growing representation within the U.S. population, relatively little is known about the pain experience of Hispanic Americans,20 and evidence is mixed regarding their relative levels of pain or pain-related distress.19,29

The aforementioned observations highlight growing empirical recognition of diversity and disparities in pain experience25 and underscore the need to examine mechanisms underlying racial/ethnic disparities in pain. The current study presents a secondary data analysis building upon published findings of relationships between ethnicity/race, injustice perception, and anger with pain outcomes.64 The current analysis expands on these findings and reports on novel associations between perceived discrimination with self-rated pain Racial Discrimination, Injustice Appraisal, and Chronic Pain outcomes, and the mediating role of cognitive processes, namely perceived injustice and pain catastrophizing on these associations. The principal aims of the current study were as follows. First, to identify direct associations between racial discrimination and pain outcomes in a multiethnic sample of individuals with CLBP. Second, to characterize the mediating roles of perceived injustice and pain catastrophizing in the relationship of perceived discrimination with disability and depression. It was hypothesized that racial discrimination would be positively related to worse pain outcomes (disability, depression, and pain intensity). It was expected that perceived injustice and pain catastrophizing would mediate the association of racial discrimination with disability and depression. Finally, to examine whether racial differences moderate the association of self-reported discrimination with outcome variables. These analyses were exploratory, and no a priori hypotheses were determined.

Methods

Participants

The sample included 137 men and women with CLBP (mean duration = 8.52 years, SD = 7.58, range = .5–39 years). Of the sample, 53.3% were male (n = 73), with a mean age of 41.9 years (SD = 12.2, range = 19–70 years). Regarding marital status, 47.4% (n = 65) of the sample were single and 31.4% (n = 43) were married at the time of data collection. Median education level was <1 completed year of college. Of the sample, 46.3% (n = 63) reported being currently employed, and 19.9% reported being unable to work (n = 27). Median income was $10,000 to $20,000; 81.0% of the sample (n = 111) reported making <$40,000 per year. Regarding the ethnic makeup of the sample, 37.2% of the sample reported being white or Caucasian (n = 51), 31.4% self-identified as black or African American (n = 43), and 31.4% self-identified as Hispanic or Latino (n = 43). Data from this study have been previously published in demonstrating racial differences in the relationships between perceived injustice and pain outcomes.64

Procedure

Participants were recruited from a large metropolitan area through advertisements in local community settings and medical offices, including flyers, newspapers, and online classifieds. Individuals who expressed interest in participation were screened by phone to determine eligibility. Participants were included in the study if they were between the ages of 18 and 70 years, endorsed presence of low back pain for at least 6 months, and reported that pain significantly interfered in daily activities. Individuals were excluded from participation if they reported co-occurring medical conditions that impacted mobility and/or if they were currently pregnant (pregnancy exclusion related to physical exertion called for by the larger study protocol). Collection of survey data was conducted via postal mail or email. Participants completed survey materials (reported herein) and then attended a single laboratory-based session in which they completed a series of physical and cognitive performance assessment (not reported herein), and presented investigators with their surveys, which were checked for completeness. As part of the laboratory sessions, participants completed a number of behavioral measures not included in current analyses. Participants were compensated $60.00 in exchange for their participation in the study. All aspects of this protocol, including informed consent procedure, were reviewed and approved by the university institutional review board.

Measures

Perceived Discrimination

The Brief Perceived Ethnic Discrimination Questionnaire − Community Version (Brief PEDQ-CV)6 is a 17-item measure that was adapted from the Perceived Ethnic Discrimination Questionnaire (PEDQ).6 It is used across ethnic groups to assess perceived racism or ethnic discrimination and measures 5 factors: exclusion/rejection, stigma/devaluation, discrimination at work/school, threat/aggression, and unfair treatment by police. A representative item from the PEDQ is “Have others made you feel like an outsider who doesn’t fit in because of your dress, speech, or characteristics related to your ethnicity/race?” Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale, ranging from “never happened” to “happened very often.” Scale scores are calculated by averaging participants’ responses, with a higher score indicating higher endorsed prior discriminatory experiences indicative of racism; scale scores range from 1 to 5. For the community version, the language of items was made less difficult and items were revised to fit the life experiences of community-dwelling adults.47 The PEDQ-CV has been most intensively studied in relation to mental and physical health outcomes and is most directly comparable to other measures of perceived interpersonal racism and ethnic discrimination. The scale has shown evidence of good reliability (Cronbach’s alpha coefficients >.95) in black and Latino samples. This measure has been used in a small number of samples that include white individuals.24 The PEDQ-CV showed a normal distribution in the current study (skewness = .80, kurtosis = −.10).

Pain Catastrophizing

This was assessed using the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS),59 a 13-item self-report questionnaire widely used to assess catastrophizing tendencies in chronic pain research and clinical settings. The PCS directs respondents to consider how they tend to think and feel in the broad context of pain stimuli. A sample item from the PCS is “I become afraid that the pain will get worse.” Respondents rate their endorsement of frequency for each item using a 0 to 4 Likert scale 0 (not at all) to 4 (all the time), and scores are computed as a sum total ranging from 0 to 52. The PCS comprises 3 subscales: magnification, rumination, and feelings of helplessness. All items are summed to create a total score. Clinically significant scores have been identified in previous publications as 20 in multidisciplinary treatment settings52 and 30 in a sample of injured workers seeking a return to work.57 The psychometric validity of the PCS has been demonstrated.44,59,66 In the current sample, the internal consistency of the PCS was high (Cronbach’s α = .95).

Perceived Injustice

Perceived injustice was assessed using the Injustice Experience Questionnaire (IEQ).58 The construct of perceived injustice encompasses 2 related domains: irreparability of loss and other blame.58 Representative items from the IEQ include “It all seems unfair,” “My life will never be the same,” and “Most people don’t understand how severe my condition is.” The IEQ consists of 12 items, scored from 0 (never) to 4 (all the time); IEQ scores are computed as a sum score with a range from 0 to 48, with higher scores representing a greater degree of perceived injustice. The IEQ has demonstrated adequate psychometric properties58 and been validated for use in both acute injury58,63 and chronic pain samples.48,51 A cutoff score of 19 on the IEQ has been identified in previous studies as indicative of risk for long-term disability.51 In the current sample, the internal consistency of the IEQ was high (Cronbach’s α = .92).

Disability

Disability was measured using the Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ).49 The RMDQ contains 24 items, scored as “Yes” or “No,” relating to a person’s perception of their difficulty performing various activities of daily living due to back pain. The RMDQ scores are computed as a sum score with a range from 0 to 24, with higher scores reflecting greater disability; clinically significant levels of disability have been denoted as a score of 15 or higher in prior chronic pain research.67 The RMDQ demonstrates strong reliability and validity49 and is recommended as a measure in CLBP research.16 The internal consistency of the scale was high in the current sample (Cronbach’s α = .92).

Depressive Symptoms

Severity of depressive symptoms was assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9).34 The PHQ-9 consists of 9 items, scored from 0 (not at all) to 4 (nearly every day) to measure severity of depressive symptoms. PHQ-9 scores are computed as a sum score with a range from 0 to 27; prior research has indicated that a score of 14 or greater may denote clinically significant depressive symptoms in chronic pain populations.53 It is a reliable and valid measure of severity of depression.34 The internal consistency of the scale was high in the current sample (Cronbach’s α = .91).

Pain Intensity

Pain intensity was assessed using the Pain Rating Index of the McGill Pain Questionnaire − Short Form.7,41 This questionnaire assesses pain intensity over the previous 2 weeks and comprises a sum of 15 items describing sensory and affective dimensions of pain. Item rankings are rated from 0 (none) to 3 (severe), and total scores range from 0 to 45, with higher scores indicating greater pain experience. The Pain Rating Index of the McGill Pain Questionnaire − Short Form has demonstrated adequate reliability and validity in chronic pain and other conditions.7 Internal consistency of this scale was high (Cronbach’s α = .92).

Income

Yearly income was assessed using a categorical series of responses. Responses were coded in ranges of $10,000 (ie, “Less than $10,000,” “$10,000 to $19,999” up to $100,000). Two additional categories reflecting higher incomes (“$100,000 to $149,999” and “Greater than $150,000”) were also included.

Analyses

Demographic differences were analyzed using SPSS Version 25 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Univariate ANOVAs were used to examine differences in study variables across ethnic groups, and in cases of a significant omnibus score, planned comparisons were conducted comparing scores between black, Hispanic, and white participants. Similarly, comparisons across racial groups for categorical demographic variables (income, gender, etc) were estimated using chi-square tests. Based on both prior literature6 and a previous publication from this dataset,64 we expected elevated levels of disability, distress, pain symptomatology, and greater lifetime exposure to discriminatory events among black respondents compared to other racial groups; further, we compared differences between white and Hispanic participants on all study variables as these were of substantive interest and have received relatively less attention in prior studies. Path models were estimated using Mplus software, Version 6.12 (Muthén) and Muthén, Los Angeles, CA, USA)43 to test the direct effect of perceived discrimination on depressive symptoms and pain-related disability, as well as the mediating roles of pain catastrophizing and perceived injustice in these relationships. Indirect effects were estimated using a 1000-draw bootstrap-estimated product of coefficients (ab) approach, which is preferable to normal theory mediation analytic approaches due to greater statistical power and a lower risk of type I error.35 Moderation analyses were conducted by re-estimating the full model while adding interaction terms between race and the exogenous or predictor variable for each path (ie, race-by-PEDQ score predicting pain catastrophizing, perceived injustice, depressive symptoms, or disability; race-by-IEQ and race-by-PCS interactions predicting depression or disability). To avoid redundancy among presented path models, moderation effects are reported in the “Results” section only, rather than being presented as a separate figure. All model parameters including mediated and moderated effects are presented as standardized path coefficients to allow comparison across paths. As Mplus does not output significant values for standardized path coefficients in conjunction with bootstrapping procedures, these significant values are drawn from equivalent unstandardized path models. Pain intensity scores and self-reported race were included as covariates in all fully specified models. As the fully specified models were fully saturated, model fit indices indicated perfect fit and are therefore not reported. Given the strong theoretical relationship between pain catastrophizing and perceived injustice,56,58 these factors were freed to covary in all fully specified models.

Results

Ethnic Differences in Study Variables

Descriptive statistics for primary study variables are summarized in Table 1 for the entire sample and each racial group. Notable ethnic differences were observed across study variables. No racial differences were noted in pain duration (F(2, 135) = 2.64, P = .075), age (F(2, 133) = .487, P = .62), gender (χ2(2) = 1.05, P = .59), or income (χ2(18) = 27.84, P = .064). Black participants reported significantly higher levels of pain-related injustice appraisal (F(2, 134) = 14.60, P < .001), disability (F(2, 134) = 13.29, P < .001), depressive symptomatology (F(2, 134) = 4.09, P = .02), and pain catastrophizing (F(2, 117) = 5.82, P = .004) than both white and Hispanic participants, whereas white and Hispanic participants did not differ on these measures. Black participants also reported significantly higher levels of perceived racial discrimination compared to Hispanic participants; although overall higher discrimination scores were observed among black participants relative to white participants, this difference did not reach statistical significance (F(2, 134) = 2.18, P = .12). Black participants also reported significantly greater pain intensity scores than white participants but not Hispanic participants (F(2, 134) = 6.49, P = .002); white and Hispanic participants did not differ significantly in average pain intensity.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Pain, Disability, and Psychosocial Variables

| Mean (SD) | Total Sample | Black Participants | Hispanic Participants | White Participants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MPQ-SF-PRI | 21.96 (13.02) | 25.26 (11.00, n = 43)a | 22.49 (17.11, n = 43) | 18.68 (9.59, n = 50) |

| RMDQ | 13.27 (6.47) | 17.14 (6.10, n = 43)b | 11.74 (5.70, n = 43) | 11.29 (6.04, n = 51) |

| PHQ-9 | 10.44 (7.17) | 12.93 (6.76, n = 43)b | 8.88 (7.73, n = 43) | 9.65 (6.59, n = 51) |

| PCS | 25.03 (13.71) | 30.63 (13.25, n = 40)b | 24.00 (15.49, n = 43) | 21.22 (11.66, n = 51) |

| IEQ | 25.09 (12.27) | 32.72 (10.76, n = 43)b | 22.00 (10.90, n = 43) | 21.25 (11.80, n = 51) |

| PEDQ | 1.97 (74) | 2.19 (.81, n = 42)c | 1.78 (.59, n = 41) | 1.94 (74, n = 50) |

Abbreviations: MPQ-SF-PRI, Pain Rating Index of the McGill Pain Questionnaire – Short Form; PDI, Pain Disability Index.

Score is significantly greater than white participants at P < .05.

Score is significantly greater than both Hispanic and white participants at P < .05.

Score is significantly greater than Hispanic participants at P < .05.

Bivariate Associations

Bivariate correlations can be found in Table 2. Based on previously suggested benchmarks for interpreting the magnitude of bivariate correlations,14,27 perceived racial discrimination showed small-to-moderate positive correlations with all other study variables. Small-to-moderate, yet statistically significant, relationships were noted between discrimination and perceived injustice (r = .345, P < .001), depression (r = .326, P < .001), and disability (r = .302, P = .001) and modest associations were noted between discrimination and pain intensity (r = .172, P = .049) and pain catastrophizing (r = .195, P = .034). Additional associations have been described elsewhere[63]—briefly, other study variables (pain intensity, pain catastrophizing, perceived injustice, disability, and depressive symptoms) demonstrated moderate positive associations (r = .421–.691, P < .001 in all cases).

Table 2.

Correlations Between Study Variables

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Perceived discrimination (PEDQ) | .195* | .345** | .302** | .326** | .208* |

| 2. Pain catastrophizing (PCS) | - | .604** | .638** | .641** | .421** |

| 3. Perceived injustice (IEQ) | - | .691** | .630** | .589** | |

| 4. Disability (RMDQ) | - | .598** | .613** | ||

| 5. Depression (PHQ-9) | - | .542** | |||

| 6. Pain intensity (MPQ-SF-PRI) | - |

P < .05.

P < .01.

Path Modeling Results

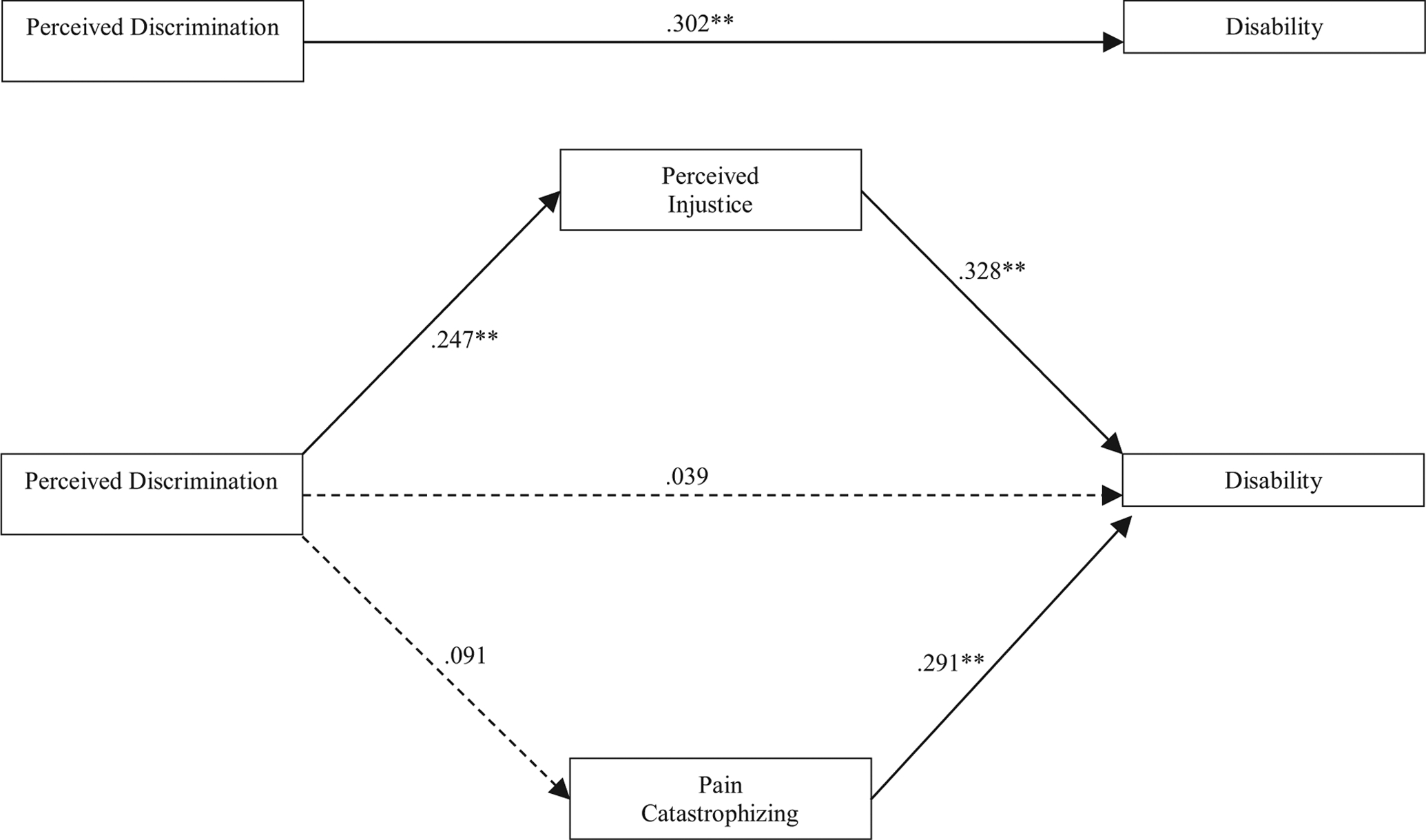

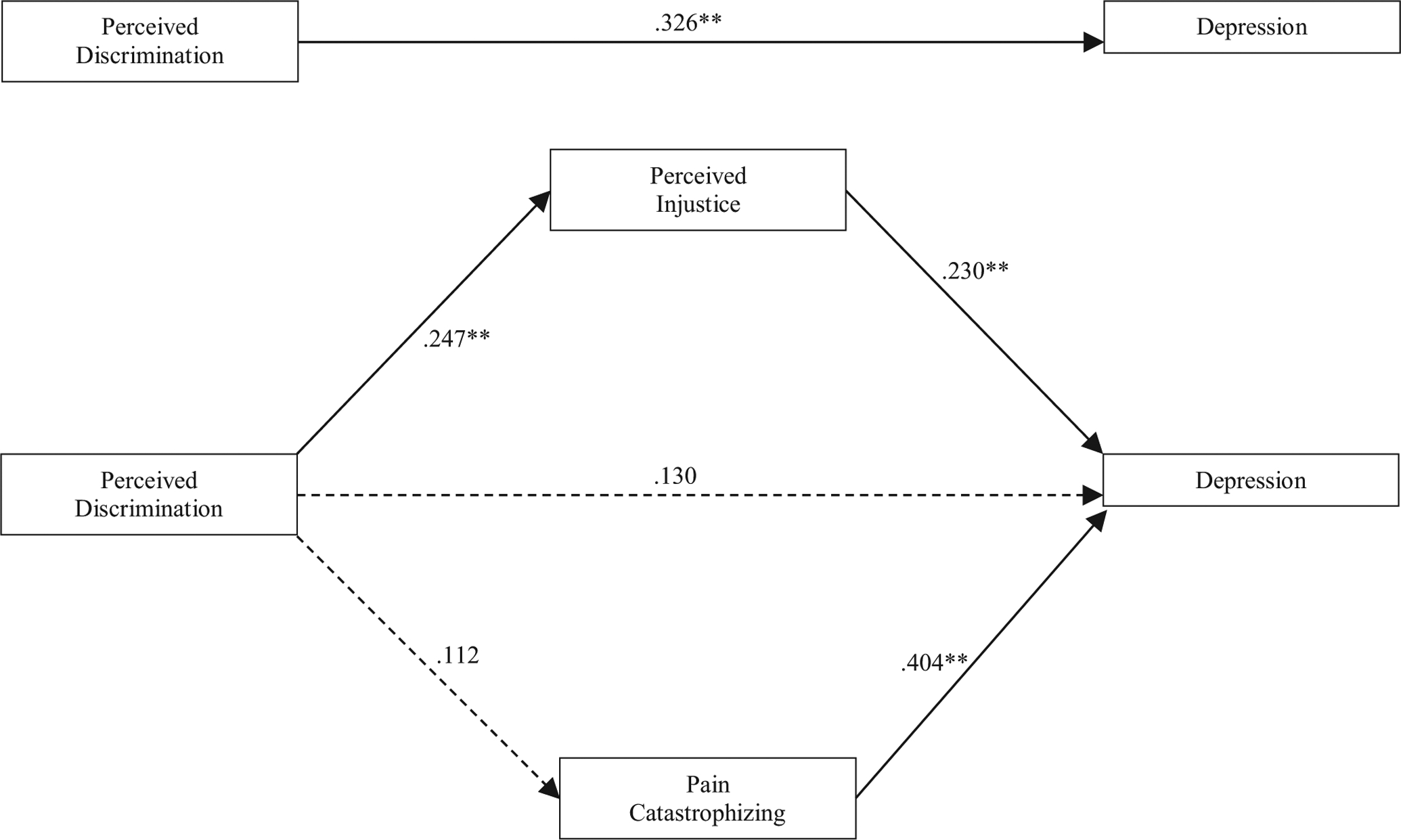

When the direct effect of the exogenous variable (perceived discrimination) was modeled without other predictors in the model, higher levels of perceived discrimination predicted higher levels of disability (β = .302, P < .001) and depression (β = .326, P < .001). Similarly, participants reporting higher levels of perceived discrimination reported higher levels of perceived injustice related to their pain, but did not report significantly different levels of pain catastrophizing. Both potential mediators (pain catastrophizing and perceived injustice beliefs related to pain) showed significant and positive relationships with depression and disability ratings. Notably, perceived injustice showed a stronger relationship with disability than pain catastrophizing, whereas pain catastrophizing showed a relatively stronger relationship with depression, compared to perceived injustice. Pain intensity scores were also found to be significantly and positively related to perceived injustice (β = .437, P = .001) and pain catastrophizing (β = .561, P < .001), but were not significantly related to depressive symptoms (β = .142, P = .19) and disability scores (β = .129, P < .27).

Fully Specified Models

The total proportion of variance of the outcome variable (R2) accounted for in each model, above and beyond the effects of pain intensity and self-reported race, can be found in Table 3. In the fully specified model predicting disability ratings (Fig 1), inclusion of both mediators reduced the direct effect of perceived discrimination on disability ratings to nonsignificance (β = .023, P = .73). Perceived injustice (ab = .114, P = .005) was found to mediate the relationship between perceived discrimination and disability ratings. In the fully specified model predicting depressive symptoms (Fig 2), perceived injustice and pain catastrophizing continued to show significant relationships with depressive symptoms, but the direct effect of perceived discrimination was no longer statistically significant (β = .116, P = .072). Perceived injustice scores were found to significantly mediate the relationship between perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms (ab = .065, P = .042). Pain catastrophizing was not found to be a significant mediator of the relationship between perceived discrimination and either outcome variable (P > .14 in both cases).

Table 3.

Variance Accounted for in the Fully Specified Model (R2)

| Endogenous Variable | Perceived Discrimination Main Effect | Fully Specified Model Disability as Outcome | Fully Specified Model- Depressive Symptoms as Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disability | .091 | .559 | - |

| Depressive symptoms | .107 | - | .521 |

NOTE. R2 estimates do not include effects of pain intensity.

Figure 1.

Perceived injustice as a mediator of the effects of perceived discrimination on disability. All path coefficients presented in standardized form. Covariates in model included pain intensity and self-reported race.

Note: ** = p < .01; * = p < .05

Figure 2.

Perceived injustice as a mediator of the effects of perceived discrimination on depression. All path coefficients presented in standardized form. Covariates in model included pain intensity and self-reported race.

Note: ** = p < .01; * = p < .05

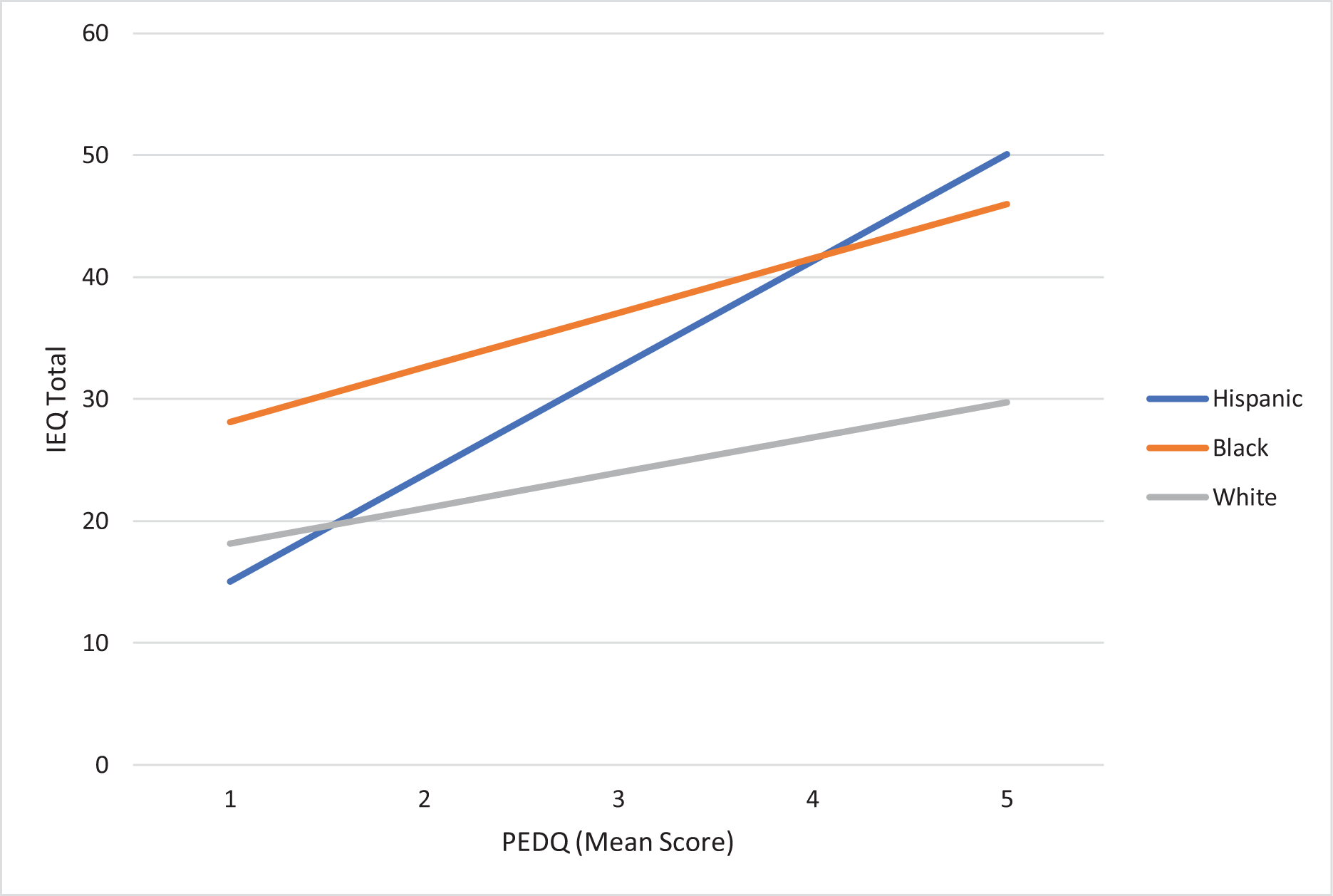

Moderation Analyses

When race was tested as a moderator of each path in the fully specified model, a significant race-by-perceived discrimination interaction was noted in predicting perceived injustice scores (interaction β = −.190, P= .010). When simple slopes were explored by racial group, the relationship between perceived discrimination and perceived injustice was found to be significant and of a larger magnitude for black/African American participants (β = .369, P = .016) and Hispanic participants (β = .463, P = .002), but were not statistically significant for white participants (β = .185, P = .20). The separate slopes for each racial group can be found in Fig 3. No other significant interactions between race and study variables were noted (P > .31 in all cases).

Figure 3.

Relationship between perceived ethnic discrimination and perceived injustice by racial group.

Note: PEDQ = Perceived Ethnic Discrimination Questionnaire; IEQ = Injustice Experiences Questionnaire

Discussion

In a multiethnic sample of individuals with CLBP, our results revealed a significant intervening role of injustice appraisal, as opposed to pain catastrophizing, in the relationship between endorsed lifetime exposure to discriminatory experiences and both self-reported disability and depression. These results suggest that greater exposure to prior experiences of racial discrimination may increase vulnerability to elevated injustice appraisals—ie, perceptions of the irreparability and unfairness related to one’s chronic pain experience. Conversely, the lack of association between perceived discrimination and catastrophizing suggests that these may be conceptually distinct parallel risk factors in chronic pain experience. In addition, moderation models revealed that associations between perceived discrimination and injustice appraisals were stronger, and statistically significant, only for participants who identified with a racial minority group—ie, black and Hispanic participants.

In the current sample, black participants endorsed higher levels of discrimination experiences compared to Hispanic participants, although the difference in reported discrimination was not significantly different between black and white participants. This finding is counterintuitive and may reflect an instrumentation issue either with variability in how the items were interpreted by respondents or perhaps a degree of under- or over-reporting by 1 group. Given the PEDQ measure perceptions of discriminatory ethnic or racial experiences, it is unclear to what extent questions reflect the observable frequency or severity of such events; consequently, further work on instrumentation and measurement in this regard would be valuable. Although PEDQCV scores in our sample reflected a relatively low level of perceived discrimination, they were comparable to prior studies.5,6 It may also be that the predominantly low-income nature of our sample played a role in this finding; prior empirical studies have suggested that the effects of socioeconomic indicators and race on adjustment to physical symptoms are intertwined and may necessitate examination in samples that reflect a greater diversity across the socioeconomic spectrum.15,38 In addition, black participants also endorsed higher levels of pain intensity, disability, depressive symptoms, and pain catastrophizing compared to both white and Hispanic counterparts. These findings are consistent with low back pain-specific findings in the area of Workers’ Compensation9,11 as well as evidence of worse pain outcomes and pain care for black individuals in the United States.1,25 Our findings are also consistent with the literature documenting a reliable association between racial discrimination and negative health outcomes,37 as well as a handful of studies addressing the intersection of discrimination and pain experience among racial minority groups.8,23,26,36,62 Despite the magnitude of the condition, fewer studies still specifically address low back pain.17

Notably, there was a weak association between perceived discrimination and pain intensity; this finding is not surprising for a few reasons. First, while perceived discrimination represents an appraisal likely reflecting an accumulation of life experiences and social context that is likely to reflect a largely stable construct (albeit one that may change with accumulated experience across a long period of time), assessment of pain intensity more likely reflect a more specific and often variable physical symptomatology, which might be expected to fluctuate across time in ways that discriminatory experiences may not. The same conclusion may be drawn for the association between perceived discrimination and injustice perception, which was significant but also relatively modest, suggesting that these constructs are likely distinct and their co-occurrence may be more apparent in some individuals than others. Second, the aspect of discriminatory and pain experiences that are most likely to be connected is through cognitive/affective responses, which themselves may also be variable across time and do not necessarily show a perfect correspondence with the occurrence of stressful life events such as discrimination or physical symptomatology.

The current study is the first to examine these relationships using a structural path modeling approach, allowing for simultaneous estimation of multiple direct and mediated effects and more effective modeling of complex psychological phenomena. Analyses revealed an association between perceived discrimination and pain-related injustice appraisal, and further indicated that perceived injustice accounted for a significant degree of the relationship between perceived discrimination and disability and depression, above and beyond the effects of pain intensity and income. In contrast, pain catastrophizing did not demonstrate a significant association with perceived discrimination. These differential relationships highlight both the significance of the association between discrimination experiences and health-related injustice appraisals, and the theoretical specificity of injustice appraisal as a potential mechanism for the impact of perceived discrimination on pain-related outcomes. Although perceived injustice and pain catastrophizing are major predictors of negative pain outcomes, the lack of an association between catastrophizing and discriminatory experiences suggests that catastrophizing represents a parallel risk factor alongside injustice perception for poor coping and adjustment. The findings intuitively suggest that prior discrimination experiences to a greater degree inform specific justice beliefs related to pain compared to other appraisals related to pain, such as the magnification of the threat value of pain. Further, these results suggest that assessing experiences of racial discrimination may add incrementally to the prediction of disability and mood disturbance in chronic pain, which are common co-occurring problems with highly multifactorial etiologies.

The association between perceived racial discrimination and injustice appraisal related to one’s health condition is both intuitive and surprisingly understudied. Research addressing health-related injustice appraisal is still early in development and as such has addressed relatively few (although expanding) health conditions and populations.42 Relatedly, research on health-related injustice appraisal has almost exclusively been conducted with largely Caucasian samples. Studies of multiethnic samples63 conducted by the current research team have consistently indicated that black participants endorse higher pain-/injury-related injustice appraisals than white counterparts and the current findings provide a glimpse into why this may be the case. Similarly, previous findings have demonstrated the incremental value of injustice beliefs within the CLBP population, in addition to replicating prior findings regarding racial disparities with respect to pain and psychosocial outcomes.64 The current study expands on these findings and examines the interface of societal- and individual-level inequities with injustice appraisals regarding a specific pain condition like CLBP. Specifically, this is the first evidence that lifetime experience of social injustices may contribute to stronger appraisals regarding the injustice of one’s own pain or health condition, and subsequently worse adjustment to pain. In addition, for racial minority individuals, adjustment to chronic pain or injury may indeed reflect differential economic access and biased treatment experiences,1,28 further contributing to appraisals of discrimination and injustice. People of lower socioeconomic status who are systematic targets of unfairness may, understandably, develop a sense of helplessness to redress unfair situations, which may subsequently fuel a cascade of negative health consequences and an increased sense of unfairness over time.30

Moderation analyses additionally suggested that the aforementioned associations may be more salient for some groups than others. Specifically, significant association between discrimination and perceived injustice were observed for black and Hispanic participants only. Given the distribution of racial discrimination scores in the current sample, we cannot conclude that the differential findings owe to greater exposure to discriminatory experiences among black and Hispanic participants or even differential quality of such experience. However, research with black and Hispanic populations has shown the deleterious impact of discriminatory experience on minority health,8,17,23,26,36,62 identifying it as a pervasive and “weathering” form of stress unique to minority communities.30 The current results suggest that minority individuals may be uniquely susceptible to the negative and potentially cumulative effects both of broader social inequities and personal appraisals regarding the injustice of one’s health condition.

Limitations

A primary limitation of our findings concerns the cross-sectional nature of the data. As all variables were collected concurrently, we cannot make inferences regarding temporal precedence or causality of the examined relationships in our model. Our use of mediation in this respect should similarly be interpreted with these limitations in mind; it is plausible that the relationships between pain-related disability and distress may influence appraisal processes related to pain. Also, the PEDQ-CV has not been validated among Caucasian individuals, which presents a potential source of bias. It would be of value for future studies to compare PEDQCV scores to other instruments assessing experiences of racial discrimination in order to further support the ecological validity of this instrument. As noted previously, the relatively low degree of discrimination reported in this sample and unexpected pattern of results related to racial discrimination indicate that it may be valuable for future studies to compare PEDQCV scores with other instruments assessing experiences of racial discrimination in order to further support the ecological validity of this instrument. In addition, the study analyses were based on a relatively small sample. Although we noted some significant main effect and moderation-based differences among racial groups, replication of our findings in larger samples would further strengthen the reliability of our findings and may allow for further articulation of these relationships, such as potential explanatory factors underlying the differential relationships between injustice perception and psychosocial factors between racial groups.

Future Directions

Our findings warrant replication in larger samples and extension in longitudinal studies. As perceptions of discrimination are a longstanding risk factor that may evolve over time, it is important to examine how appraisal processes may vary over time, and whether factors like social inclusion and group identity may buffer these effects.30 Further, feelings of social isolation and anger, which have shown significant theoretical and statistical relationships with perceived injustice in prior studies,50,54 might make suitable candidates as mediators but were not tested in the current study. As noted previously, a prior publication from this sample-identified aspects of anger experience and expression as potential factors linking injustice perception and depressive symptoms.64 Given the small sample size and planned moderation analyses as part of the current study, we opted not to replicate these analyses in the current paper. However, expansion of the current findings in larger samples that more comprehensively test the associations between perceived discrimination and outcomes (eg, through sequential mediation of anger and cognitive appraisal variables) would further strengthen the interpretability of these relationships. Additionally, given the salience of justice principles among diverse and marginalized populations, significant consideration should be given to the context of prior discriminatory experiences when appraisals of perceived injustice are targeted for clinical intervention. It is plausible that reducing the frequency or impact of injustice appraisals may ameliorate some of the physical and psychosocial difficulties associated with chronic pain. Further, it is likely that efforts to address systems-level factors that perpetuate discriminatory behavior toward racial and ethnic minorities, particularly within the healthcare system, are needed to prevent the development of injustice appraisals and ultimately improve pain outcomes among these groups.

Conclusions

The current study is the first to report on the associations of perceived discrimination with pain-related outcomes in a multiethnic sample of individuals with CLBP. This study also demonstrates the specificity of perceived injustice in mediating the impact of perceived discrimination on pain-related disability and depression, and shows that these associations occur specifically in racially marginalized groups. The current findings provide an empirical foundation for future research addressing the complex interplay of social context and of psychological constructs within racially diverse populations.

Perspective:

More frequent prior experiences of racial discrimination are associated with greater depressive symptomatology and pain-related disability in individuals with chronic low back pain. These associations are explained by the degree of injustice perception related to pain, but not pain catastrophizing, and were stronger among black and Hispanic participants.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) Early Career Grants Program and the National Institute of Health under grant T32 035165 for their support of this study.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2019.09.007.

References

- 1.Anderson KO, Green CR, Payne R: Racial and ethnic disparities in pain: Causes and consequences of unequal care. J Pain 10:1187–1204, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banks KH, Kohn-Wood LP, Spencer M: An examination of the African American experience of everyday discrimination and symptoms of psychological distress. Community Mental Health J 42:555–570, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beach MC, Saha S, Korthuis PT, Sharp V, Cohn J, Wilson IB, Eggly S, Cooper LA, Roter D, Sankar A: Patient-provider communication differs for black compared to white HIV-infected patients. AIDS Behav 15:805–811, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Becker WC, Starrels JL, Heo M, Li X, Weiner MG, Turner BJ: Racial differences in primary care opioid risk reduction strategies. Ann Fam Med 9:219–225, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brondolo E, Hausmann LR, Jhalani J, Pencille M, Atencio-Bacayon J, Kumar A, Kwok J, Ullah J, Roth A, Chen D: Dimensions of perceived racism and self-reported health: Examination of racial/ethnic differences and potential mediators. Ann Behav Med 42:14–28, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brondolo E, Kelly KP, Coakley V, Gordon T, Thompson S, Levy E, Cassells A, Tobin JN, Sweeney M, Contrada RJ: The perceived ethnic discrimination questionnaire: development and preliminary validation of a community version 1. J Appl Soc Psychol 35:335–365, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burckhardt CS, Jones KD: Adult measures of pain: The McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ), Rheumatoid Arthritis Pain Scale (RAPS), Short–Form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF MPQ), Verbal Descriptive Scale (VDS), Visual Analog Scale (VAS), and West Haven–Yale Multidisciplinary Pain Inventory (WHYMPI). Arthritis Care Res 49:S96–S104, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burgess DJ, Grill J, Noorbaloochi S, Griffin JM, Ricards J, Van Ryn M, Partin MR: The effect of perceived racial discrimination on bodily pain among older African American men. Pain Med 10:1341–1352, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chibnall JT, Tait RC: Disparities in occupational low back injuries: Predicting pain-related disability from satisfaction with case management in African Americans and Caucasians. Pain Med 6:39–48, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chibnall JT, Tait RC: Long-term adjustment to work-related low back pain: Associations with socio-demographics, claim processes, and post-settlement adjustment. Pain Med 10:1378–1388, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chibnall JT, Tait RC: Legal representation and dissatisfaction with workers’ compensation: Implications for claimant adjustment. Psychol Inj Law 3:230–240, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chibnall JT, Tait RC, Andresen EM, Hadler NM: Clinical and social predictors of application for social security disability insurance by workers’ compensation claimants with low back pain. J Occup Environ Med 48:733–740, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chibnall JT, Tait RC, Andresen EM, Hadler NM: Race differences in diagnosis and surgery for occupational low back injuries. Spine 31:1272–1275, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen J: Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. New York, Routledge, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Day MA, Thorn BE: The relationship of demographic and psychosocial variables to pain-related outcomes in a rural chronic pain population. Pain 151:467–474, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deyo RA, Dworkin SF, Amtmann D, Andersson G, Borenstein D, Carragee E, Carrino J, Chou R, Cook K, DeLitto A: Focus article: Report of the NIH task force on research standards for chronic low back pain. Eur Spine J 23:2028–2045, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edwards RR: The association of perceived discrimination with low back pain. J Behav Med 31:379, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edwards RR, Cahalan C, Mensing G, Smith M, Haythornthwaite JA: Pain, catastrophizing, and depression in the rheumatic diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol 7:216, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Edwards RR, Moric M, Husfeldt B, Buvanendran A, Ivan-kovich O: Ethnic similarities and differences in the chronic pain experience: A comparison of African American, Hispanic, and white patients. Pain Med 6:88–98, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ennis SR, Ríos-Vargas M, Albert NG: The Hispanic Population: 2010. US Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration. Washington, DC, US Census Bureau, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Finch BK, Hummer RA, Kol B, Vega WA: The role of discrimination and acculturative stress in the physical health of Mexican-origin adults. Hisp J Behav Sci 23:399–429, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flor H, Behle DJ, Birbaumer N: Assessment of pain-related cognitions in chronic pain patients. Behav Res Ther 31:63–73, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goodin BR, Pham QT, Glover TL, Sotolongo A, King CD, Sibille KT, Herbert MS, Cruz-Almeida Y, Sanden SH, Staud R: Perceived racial discrimination, but not mistrust of medical researchers, predicts the heat pain tolerance of African Americans with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Health Psychol 32:1117, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gordon JL, Johnson J, Nau S, Mechlin B, Girdler SS: The role of chronic psychosocial stress in explaining racial differences in stress reactivity and pain sensitivity. Psychosom Med 79:201, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Green CR, Anderson KO, Baker TA, Campbell LC, Decker S, Fillingim RB, Kaloukalani DA, Lasch KE, Myers C, Tait RC: The unequal burden of pain: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in pain. Pain Med 4:277–294, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haywood C Jr.., Diener-West M, Strouse J, Carroll CP, Bediako S, Lanzkron S, Haythornthwaite J, Onojobi G, Beach MC, Woodson T: Perceived discrimination in health care is associated with a greater burden of pain in sickle cell disease. J Pain Symptom Manage 48:934–943, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hemphill JF: Interpreting the magnitudes of correlation coefficients. Am Psychol 58:78–79, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hirsh AT, Hollingshead NA, Ashburn-Nardo L, Kroenke K: The interaction of patient race, provider bias, and clinical ambiguity on pain management decisions. J Pain 16:558–568, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hollingshead NA, Ashburn-Nardo L, Stewart JC, Hirsh AT: The pain experience of Hispanic Americans: A critical literature review and conceptual model. J Pain 17:513–528, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jackson B, Kubzansky LD, Wright RJ: Linking perceived unfairness to physical health: The perceived unfairness model. Rev Gen Psychol 10:21–40, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jensen JD, King AJ, Guntzviller LM, Davis LA: Patient-provider communication and low-income adults: Age, race, literacy, and optimism predict communication satisfaction. Patient Educ Couns 79:30–35, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson RL, Saha S, Arbelaez JJ, Beach MC, Cooper LA: Racial and ethnic differences in patient perceptions of bias and cultural competence in health care. J Gen Intern Med 19:101–110, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krieger N: Embodying inequality: A review of concepts, measures, and methods for studying health consequences of discrimination. Int J Health Serv 29:295–352, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL: The PHQ-9: A new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatr Ann 32:509–515, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 35.MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J: Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behav Res 39:99–128, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mathur VA, Kiley KB, Haywood C Jr.., Bediako SM, Lanzkron S, Carroll CP, Buenaver LF, Pejsa M, Edwards RR, Haythornthwaite JA: Multiple levels of suffering: Discrimination in health-care settings is associated with enhanced laboratory pain sensitivity in sickle cell disease. Clin J Pain 32:1076, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mays VM, Cochran SD, Barnes NW: Race, race-based discrimination, and health outcomes among African Americans. Annu Rev Psychol 58:201–225, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McIlvane J: Disentangling the effects of race and SES on arthritis-related symptoms, coping, and well-being in African American and white women. Aging Ment Health 11:556–569, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McParland JL, Eccleston C: “It’s not fair” social justice appraisals in the context of chronic pain. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 22:484–489, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 40.McParland JL, Eccleston C, Osborn M, Hezseltine L: It’s not fair: An interpretative phenomenological analysis of discourses of justice and fairness in chronic pain. Health 15:459–474, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Melzack R: The short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire. Pain 30:191–197, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Monden KR, Trost Z, Scott W, Bogart KR, Driver S: The unfairness of it all: Exploring the role of injustice appraisals in rehabilitation outcomes. Rehabil Psychol 61:44, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Muthén L, Muthén B: Mplus Statistical Modeling Software (Version 6.12). Los Angeles, Muthén & Muthén, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Osman A, Barrios FX, Gutierrez PM, Kopper BA, Merrifield T, Grittmann L: The Pain Catastrophizing Scale: Further psychometric evaluation with adult samples. J Behav Med 23:351–365, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paradies Y: A systematic review of empirical research on self-reported racism and health. Int J Epidemiol 35:888–901, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pascoe EA, Smart Richman L: Perceived discrimination and health: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull 135:531, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reyes-Gibby CC, Aday LA, Todd KH, Cleeland CS, Anderson KO: Pain in aging community-dwelling adults in the United States: Non-Hispanic whites, non-Hispanic blacks, and Hispanics. J Pain 8:75–84, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rodero B, Luciano JV, Montero-Marín J, Casanueva B, Palacin JC, Gili M, del Hoyo YL, Serrano-Blanco A, Garcia-Campayo J: Perceived injustice in fibromyalgia: Psychometric characteristics of the Injustice Experience Questionnaire and relationship with pain catastrophising and pain acceptance. J Psychosom Res 73:86–91, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Roland M, Morris R: A study of the natural history of back pain: Part I. Development of a reliable and sensitive measure of disability in low-back pain. Spine 8:141–144, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Scott W, Trost Z, Bernier E, Sullivan MJ: Anger differentially mediates the relationship between perceived injustice and chronic pain outcomes. Pain 154:1691–1698, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Scott W, Trost Z, Milioto M, Sullivan MJ: Further validation of a measure of injury-related injustice perceptions to identify risk for occupational disability: A prospective study of individuals with whiplash injury. J Occup Rehabil 23:557–565, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Scott W, Wideman TH, Sullivan MJ: Clinically meaningful scores on pain catastrophizing before and after multidisciplinary rehabilitation: a prospective study of individuals with sub-acute pain after whiplash injury. Clin J Pain 30:183–190, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Slater MA, Doctor JN, Pruitt SD, Atkinson JH: The clinical significance of behavioral treatment for chronic low back pain: An evaluation of effectiveness. Pain 71:257–263, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sturgeon JA, Carriere JS, Kao M- CJ, Rico T, Darnall BD, Mackey SC: Social disruption mediates the relationship between perceived injustice and anger in chronic pain: A collaborative health outcomes information registry study. Ann Behav Med 50:802–812, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sturgeon JA, Zautra AJ: State and trait pain catastrophizing and emotional health in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Behav Med 45:69–77, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sturgeon JA, Ziadni MS, Trost Z, Darnall BD, Mackey SC: Pain catastrophizing, perceived injustice, and pain intensity impair life satisfaction through differential patterns of physical and psychological disruption. Scand J Pain 17:390–396, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sullivan MJ: The Pain Catastrophizing Scale: User Manual. Montreal, McGill University, 2009, pp 1–36 [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sullivan MJ, Adams H, Horan S, Maher D, Boland D, Gross R: The role of perceived injustice in the experience of chronic pain and disability: Scale development and validation. J Occup Rehabil 18:249–261, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sullivan MJ, Bishop SR, Pivik J: The Pain Catastrophizing Scale: Development and validation. Psychol Assess 7:524, 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sullivan MJ, Scott W, Trost Z: Perceived injustice: A risk factor for problematic pain outcomes. Clin J Pain 28:484–488, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sullivan MJ, Thorn B, Haythornthwaite JA, Keefe F, Martin M, Bradley LA, Lefebvre JC: Theoretical perspectives on the relation between catastrophizing and pain. Clin J Pain 17:52–64, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Taylor JLW, Campbell CM, Thorpe RJ Jr., Whitfield KE, Nkimbeng M, Szanton SL: Pain, racial discrimination, and depressive symptoms among African American women. Pain Manag Nurs 19:79–87, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Trost Z, Agtarap S, Scott W, Driver S, Guck A, Roden-Foreman K, Reynolds M, Foreman ML, Warren AM: Perceived injustice after traumatic injury: Associations with pain, psychological distress, and quality of life outcomes 12 months after injury. Rehabil Psychol 60:213, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Trost Z, Sturgeon J, Guck A, Ziadni M, Nowlin L, Goodin B, Scott W: Examining injustice appraisals in a racially diverse sample of individuals with chronic low back pain. J Pain 20:83–96, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Trost Z, Van Ryckeghem D, Scott W, Guck A, Vervoort T: The effect of perceived injustice on appraisals of physical activity: An examination of the mediating role of attention bias to pain in a chronic low back pain sample. J Pain 17:1207–1216, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Van Damme S, Crombez G, Bijttebier P, Goubert L, Van Houdenhove B: A confirmatory factor analysis of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale: Invariant factor structure across clinical and non-clinical populations. Pain 96:319–324, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vlaeyen JW, Kole-Snijders AM, Boeren RG, Van Eek H: Fear of movement/(re) injury in chronic low back pain and its relation to behavioral performance. Pain 62:363–372, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Westman AE, Boersma K, Leppert J, Linton SJ: Fear-avoidance beliefs, catastrophizing, and distress: A longitudinal subgroup analysis on patients with musculoskeletal pain. Clin J Pain 27:567–577, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Williams DR, Mohammed SA: Discrimination and racial disparities in health: Evidence and needed research. J Behav Med 32:20–47, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Williams DR, Spencer MS, Jackson JS. Race, stress, and physical health: The role of group identity In Contrada RJ & Ashmore RD (eds): Rutgers series on self and social identity, Vol. 2. Self, social identity, and physical health: Interdisciplinary explorations. New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press; 71–100, 1999 [Google Scholar]