Abstract

Purpose:

The study aimed to identify HIV prevention, testing, and care services prioritizing young Latino men who have sex with men (MSM) in an HIV service delivery network in Miami-Dade County, Florida, by visually describing structural features and processes of collaboration within and between health and social venues.

Methods:

The study used cross-sectional data from 40 social and healthcare venues providing goods and services to young Latino MSM. Each venue provided information surrounding HIV-related services provided and collaborations with other venues. Network visualization analyses were performed using UCINET6 and NetDraw2.160.

Results:

The most commonly used services offered by health and social venues were free condoms and HIV education materials. Collaborations both within and between health and social venues components of the network existed. Not all health and social venues provided services to young Latino MSM.

Conclusion:

Health venues can reach and incorporate hard to reach populations, such as non-English speaking and undocumented young Latino MSM, to provide HIV-related services using service delivery venue social networks.

Keywords: Social network methodologies, venue collaboration, HIV, Hispanic Americans, MSM

Introduction

HIV disproportionately affects Hispanic/Latinx communities in the United States (1). In 2016, the Latinx community accounted for almost a quarter of all newly diagnosed HIV cases, despite being only 17% of the total U.S. population (2–5). Miami-Dade County in southern Florida hosts one of the nation’s most densely populated Latinx communities, with 69% of the population identifying as Hispanic/Latinx (1). Of people living in Miami, 53% are foreign born and 74% do not speak English at home, instead speaking languages such as Spanish or Creole (1). In addition to being a majority Hispanic/Latinx-identified county, Miami-Dade County has the highest HIV rate and the third highest number of people living with HIV/AIDS in the U.S. (2–6). Among males, the greatest HIV burden is among men who have sex with men (MSM), and Latino men ages 20-39 years (2–5). One of the factors contributing to HIV infection among young Latino MSM ages 16-29 years (YLMSM) in is the lack of easily accessible and acceptable HIV-related services (7, 8).

Increasing HIV-related services in Miami-Dade County may necessitate additional strategies that lead to the creation of more effective cross-sector partnerships between health and social venues. Many MSM are exposed to HIV risk at social venues (9). Because MSM tend to congregate in certain identifiable social venues, these have the potential to promote HIV-related health services, especially to those who prefer not to be publicly identified with the gay or bisexual communities (10, 11). Integrating health services in social venues could pool resources, talents, and strategies together to overcome disparities in accessing health services among underserved Latino populations, such as MSM, leading to a more effective HIV service delivery network. Collaboration could also increase: 1) information sharing; 2) productivity; 3) accessibility; resources; 4) enhanced services; 5) comprehensive service delivery; and 6) legitimacy with some parts of the community (12–14).

According to Roger’s Diffusion of Innovation Theory, an innovation is communicated by members of a social system through specific channels over time (15). In the context of HIV risk reduction interventions, this theory emphasizes the importance of social network methodologies and analysis, especially in regards to information awareness (15–19). Social network methodologies have found that HIV risk behavior reduction may be facilitated through peer networks and popular opinion leaders (20, 21). Research has suggested that HIV risk reduction interventions, when implemented at the social or community level may have a larger impact than when conducted at the individual-level (18). As such, it is important to understand community contexts, such as the availability and accessibility of social and health venues, and their influences on HIV high risk behaviors. Further research is required to expand our understanding of health and social venues and the role of venue collaboration in the provision of HIV risk reduction interventions.

This study examined HIV prevention, testing, and care services targeting YLMSM within an HIV service delivery network in Miami-Dade County. This study aimed to visually describe structural features and processes of collaboration within and between health and social venues frequented by Latinos. This study sought to visually identify characteristics of collaboration based on the number of HIV services provided by the observed venues. This study defined two types of venues: health venues, such as health care centers and community-based organizations, and social venues, such as gay bars, adult video stores, and religious and business organizations offering social events for the MSM community. The authors used social network methodologies and analysis to assess network characteristics among these venues and to identify venues that occupy a central role in a collaboration network (22, 23). Studying cooperation and support networks is important because it provides an understanding on how ongoing strong and weak ties between organizations can significantly influence organizational actions and outcomes (24, 25). This study created whole collaboration networks by asking venue representatives to nominate their collaborators.

Methods

Sampling of organizations-

This study was conducted as part of the Young Men’s Affiliation Project (YMAP), a larger, multisite longitudinal study being conducted in Chicago and Houston examining social networks and venue affiliation among young MSM in relation to their HIV/STI risk and preventive behavior and further information can be found elsewhere (10). Venue-level network data were collected in Miami-Dade County in 2016. To begin data collection, investigators, staff members, and community consultants developed a roster of 59 health venues and social venues serving YLMSM in Miami-Dade County. The roster was created by compiling a list of organizations from public sources, which advertised to, served, or were frequented by YMSM (10). Subsequently, study staff and co-authors who are members or are familiar with the target population reduced this venue list to of 40 venues based on perceived importance to the YLMSM population, geographic clustering in the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) community, perceived salience in the Latino community (i.e., prestige, reputation, size), and perceived likelihood of participating in the study, as rated by Latino members from the MSM community in Miami and consensus among the study team (10). Health venues were defined as any venue that provided HIV/AIDS prevention, care, and related services to the sexual minority communities in Miami-Dade County. Social venues included were any place where YLMSM were known to congregate. Figure 1 includes a list of services provided by health and social venues. A research assistant, a gatekeeper to the LMSM community (e.g., individuals who facilitate/prevent/assist services/members within a community), visited each venue in the sampling roster. The gatekeeper contacted the owner, manager, or front-line person and arranged a time and date for an in-person interview. Two trained bilingual research associates interviewed all venue representatives in a private, face-to-face setting. Before beginning, written informed consent was obtained. Participants completed the structured interview in approximately 1.5 hours. Data were recorded using iPad-assisted personal interviewing software. Venue representatives were interviewed if they: (1) had been working at the venue for at least 6 months; (2) were not planning to leave the venue for other employment in the next 2 years; (3) were legally able to work at the site venue (over age 21 years if working in a bar or club serving alcohol); and (4) were not intoxicated, mentally or emotionally unstable, or otherwise unable to respond to interview questions. A university institutional review board approved study procedures and surveys.

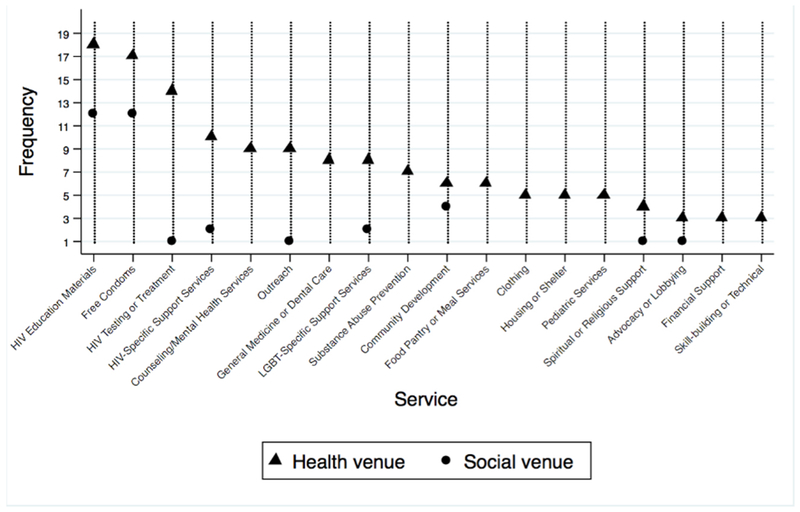

Figure 1.

Service Provision Ranking and Frequency by Type of Venues Providing HIV Related Services to Latino MSM in Miami, 2016.a

a Venues could have more than one resource activity

Measures-

Data were collected using Qualtrics (26). The questionnaire was developed in English, translated into Spanish, then back translated into English. Data collection procedures are further described elsewhere (10). The original English questionnaires and the back translated Spanish versions were consistent. A panel of bilingual researchers assessed face and content validity of the Spanish version of the questionnaire. Instrument reliability and validity were tested with Latino and African-American respondents in Houston and Chicago. Five YLMSM residing in Miami-Dade County reviewed the questionnaire and confirmed that content and language were clearly worded and understandable.

The interview was divided into two sections. The first section gathered a description of the venue. The second section obtained information on a venue’s relationship with other venues in the Miami-Dade metropolitan area. To obtain venues’ relationship data, the interviewer read the following statements:

“To begin, I will give you a list of facilities and organizations that this study considers; therefore, we will reduce it to only the places that you have interacted with. From there, I will ask questions to better understand the kind of relationships you have with these facilities.”

“We have to narrow the list of the facilities, with which you have had any interaction with, whether it is positive or negative, in the last year. In the last 12 months, which of the following facilities have you interacted with?”

The interviewer provided the list of venues included in the study. Participants had the opportunity to add venues which were not on this list. Then, for each venue, participants were asked to select any of the following types of relationships their organization had during the past year: (1) “Collaboration” (i.e., cooperation), by asking whether the venue had worked together on any activity, project, or event with a common goal, whether formally or informally; (2) “Sponsorship,” by asking whether the venue had financed, in full or in part, any activity, project, or event carried out by other venues; and, (3) “Referral,” by asking whether the venue referred costumers or partners elsewhere for goods or services, particularly for the benefit of costumers or members (10). This study defined the term “collaboration” by combining relationships based on collaboration, sponsorship and referral. A binary variable for collaboration was created by coding ‘1’ if each pair of venues shared at least one common type of relation and coding as ‘0’ if otherwise.

Data analysis-

SPSS was used to obtain descriptions of the respondents and venue attributes (27). A relational cooperation matrix for each venue was created to obtain descriptions of network attributes. The presence of a collaborative relationship was entered in the matrix if a participant reported that his/her venue had at least one type of relationship with another venue (sponsorship, sponsor, referral, and collaboration). Graphs were developed to represent health or social venue networks. Links among venues were assessed for collaboration. Due to the reciprocal nature of the collaboration, all network links were maximally symmetrized using UCINET6 (28). The authors assessed network descriptors including degree centralization, the extent to which some nodes have a large number of ties) and Eigenvector centrality, the extent to which a node is connected to many nodes who themselves have high centrality scores. Network graphs were then constructed. Lines represented the presence of a collaborative relationship. Colors were used to designate a node as a health venue or a social venue. Degree centrality or Eigenvector centrality scores were represented by node size with higher centrality scores indicated by larger nodes. Additional colors were used to visualize the numbers of services provided by a venue.

Results

As shown in Table 1, significantly more males than females responded to the questionnaire for social venues than health venues. The majority of those reporting were Latino and full-time employees. There were no significant differences in age or years affiliated with a venue.

Table I.

Frequencies (percentage) or Mean (standard deviation) of Participant Characteristics

| Social Venue (N=22) n (%) | Health Venue (N=18) n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Participants | ||

| Sex at birth1 | ||

| -Male | 20 (91%) | (8) 44% |

| Ethnicity | ||

| -Hispanic/Latino | 19 (86%) | 17 (94%) |

| Employment status | ||

| -Full-time | (14) 64% | (14) 78% |

| -Part-time | (8) 36% | (4) (22%) |

| Age (Years – 95% Confidence Interval) | 38.2 (8.83) | 42.22 (10.43) |

| Years affiliated with the venue (95% Confidence Interval) | 2.86 (3.72) | 3.89 (5.13) |

| Job title | ||

| -Owner | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) |

| -Head (e.g., president, director, CEO) | 0 (0%) | 2 (11%) |

| -Middle management (e.g., manager, coordinator) | 5 (24%) | 5 (26%) |

| -Frontline staff | 15 (71%) | 11 (63%) |

| -Other | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) |

Network structure and services provided-

Health venues provided an average of seven different HIV-related services on premises. Social venues provided an average of one HIV-related service. The most popular services provided in both types of venues were free condoms and HIV education materials. The least common services provided by health venues were financial support, skills-building or technical counseling, and advocacy or lobbying (Figure 1).

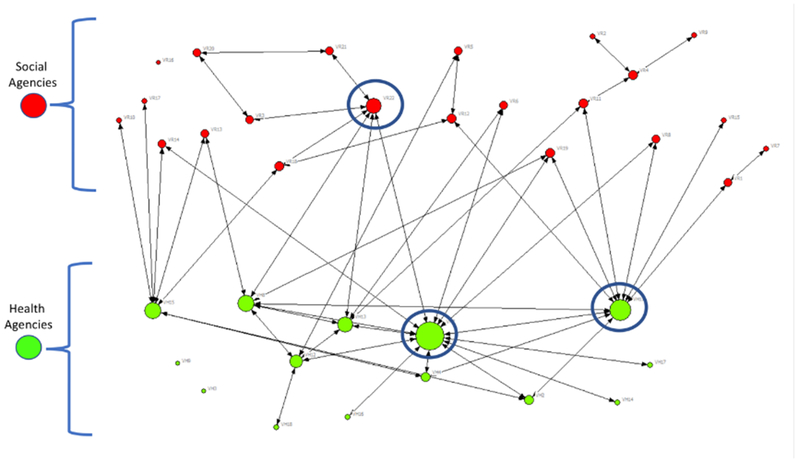

A sociogram illustrating the collaborative patterns among venues serving YLMSM in Miami is shown in Figure 2. Overall, participants reported 73 unidirectional and 72 bidirectional ties. All ties were symmetrized. The network included two sub-networks: the social sub-network located in the upper part of the graph with red nodes and the health sub-network located in the lower part of the graph network with green nodes. There were collaborations both within and between the health and social venue components of the network. There were more collaborative ties in the health sub-network than the social sub-network. There were also three venues, one social and two health, that did not have connections with the rest of the network. Higher degrees of cooperation and support relation (degree centrality) have a proportional size to their centrality score. The network had three venues with high-degree centrality; meaning that many other venues reported collaborations with them (two agencies provided health related services and one agency was a social agency).

Figure 2.

Venues’ degree centrality inside the Miami HIV Services Network of Collaboration for YLMSM

Collaborations-

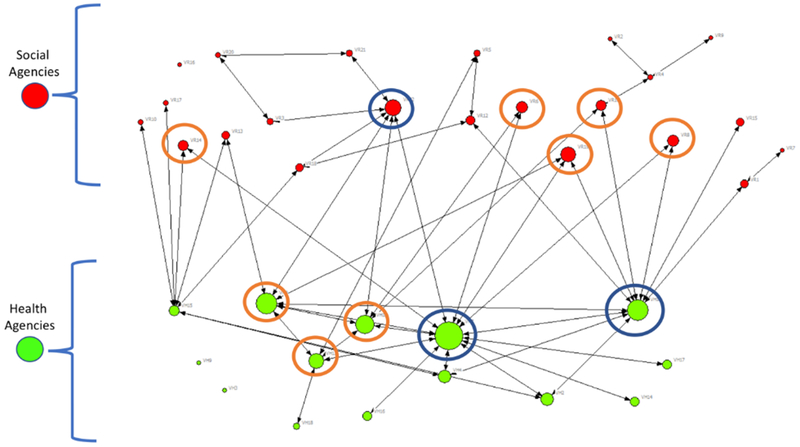

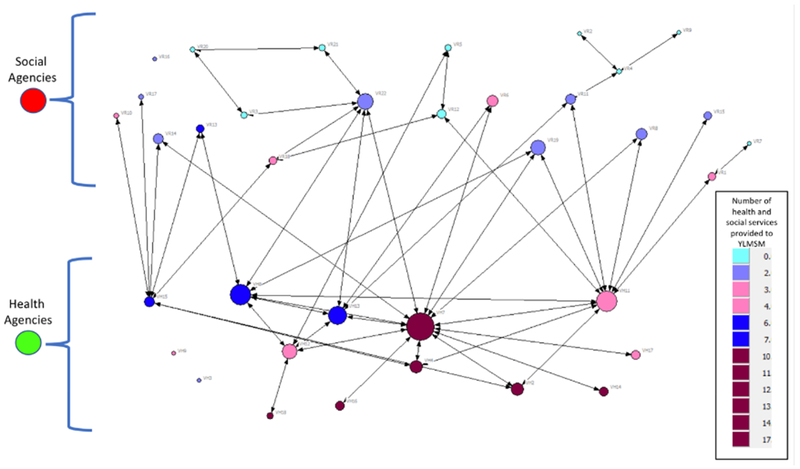

Figure 3 also includes the social and health sub-networks. Each line represents the presence of a collaborative relationship. Eight venues had high Eigenvector centrality scores (three health and five social venues). Figure 4 incorporates venue degree centrality, Eigenvector centrality, and the number of services provided to YLMSM. Nine social venues connected to the network did not provide HIV related services to YLMSM. Only one of these social venues had a connection to a health venue. All other social venues were connected to health venues, but services provided by the social venues were mainly limited to providing free condoms and HIV prevention materials. Isolated venues were not providing services to YLMSM. Five health venues were providing ten or more health services. However, four of these health venues had very low centrality scores.

Figure 3.

Venues’ Eigenvector Centrality inside the Miami HIV Service Network of Collaboration for YLMSM.

Figure 4.

Venues’ service provision inside the Miami HIV Service Network of Collaboration for YLMSM.

Discussion

This study sought to visually described collaborative efforts among social and health venues and identified characteristics of collaboration based on the number of services provided in Miami-Dade County, the epicenter of the HIV epidemic in the US. This study found connections based on services provided between health venues, social venues, and health and social venues. This study is significant as it describes how venue connections have the potential to increase YLMSM’s awareness and use of HIV-related health in Miami-Dade County, where Latinos are not accessing HIV related services. The study also found that the network of health and social venues was not dense. However, it is important to acknowledge that promoting the creation of collaborative ties between social and health venues –which is generally voluntary— involves a commitment to collaborate by both non-central and central venues. Coordinating and aligning programs in a service delivery network can be demanding in term of staffing and resource availability (29). If venues are not committed to strengthen their collaboration initiatives, effective efforts may be as minimal as placing a logo in the promotion of a venue’s activities. On the other hand, cooperation and support have the potential to raise the profile of both organizations.

The analysis found a highly centralized network of health venues dominated by three highly connected nodes. Centrality of influential venues within the network facilitates agenda setting, and creation of space for experimentation (30). However, having a centralized network could be dangerous, if one of these influential venues closes or is excluded. The network may quickly fragment into unconnected sub-networks, making access to HIV prevention and treatment even more difficult for YLMSM in Miami Dade County. It is also important to incorporate the two isolated health venues into the network of collaboration because their clients may experience barriers receiving referrals or information regarding available services (31). This study demonstrates that some health venues in this particular network may need to establish collaborative efforts. A more decentralized network would empower potential partners and may allow a more efficient information and knowledge flow. Organizations providing funding to health venues can also play an important role promoting collaboration and support.

The majority of health venues in this study relied heavily on public support (77.8%). The lack of collaboration among some health venues providing comprehensive services could be a result of a sustained funding cuts and shifts in funding priorities. Funding shifts may result in limited personnel with little time dedicated to network coordination and an increasing number of unfilled service needs (29). Low funding availability could also have been translated into an inexistent or weak institutional funding pressure to promote resource sharing among venues. However, shrinking funds could promote the development of strategic alliances inside service delivery networks and some venues may benefit from new funding environments by developing new strategic alliances that allow operational sustainability. It is unclear if the absence of collaborative links between health venues was due to lack of awareness about other venues; differing or conflicting interests, needs, and objectives; or competition for similar funding.

Fragmentation of service delivery networks can seriously harm the continuation of care (32). The results suggest that some health venues not collaborating with other health venues may be at risk of disappearing. This could be caused by low levels of reciprocity. Another cause of risk for health venues without a large number of connections could be low levels of multicomplex relationships. It has been suggested that before establishing large collaborative efforts, venues should test potential collaborative partners with time-limited or less-intensive activities (29). Further studies should explore if some venues offering HIV services may not be inclined to collaborate with venues with low centrality scores.

Limitations-

This study has several limitations. The data are cross-sectional and do not allow the assessment of dynamic changes. This limits an assessment of the sustainability or longevity of the HIV service delivery network over time. Also, we studied an HIV service delivery network serving YLMSM from a specific geographic region and services did not include pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). Our findings may not be generalizable to other regions or to venues providing services to other populations. The analysis of symmetrized data was conducted as it may be more likely that one partner would remember a relationship that the other forgot, rather than reporting a collaborative relationship that did not exist (33). Further, we may be subject to recall bias and not have complete information on all collaborations as only one representative from each venue was interviewed. In order to have an inclusive roster of venues serving YLMSM in Miami and reducing the number of venues that may have been forgotten, we developed a roster with stakeholders from the LMSM community in Miami-Dade County. We are uncertain if venues included in the study were more or less likely to collaborate than those venues that were excluded. Finally, findings from this study are based on visual analysis, which are subject to investigator bias.

Conclusion

The collaborative structure of the Miami HIV service delivery social network is an example of how health venues can reach and incorporate some sub-groups of LMSM who may be considered hard-to-reach populations, such as non-English speaking and undocumented YLMSM. In order to more effectively address HIV disparities in Latino populations, there is a need to promote available services and encourage the use of these services. Further studies should also confirm our findings using statistical models. For example, geographic analysis should analyze if geographic proximity of venues influenced collaboration. In addition, longitudinal studies should analyze how this service delivery network for YLMSM evolves overtime (29). Finally, a qualitative study could also examine factors that influence collaboration among venues to provide more context to the findings.

Our findings suggest that a social network of health services composed of venues that provide various types of services can beneficially impact in the community (34). Our study findings contribute to the optimization of linkage to HIV preventive services, care, promotion of retention in care, antiretroviral adherence, and viral suppression, to effectively decrease community viral load and AIDS-related mortality. This study shows the relevance for using social network approaches to understand the structures that can lead to the creation or modification of health services in social venues to address disparities in accessing health services among underserved Latino populations, such as MSM. This network approach could also be used to promote the creation of policies that distribute resources among several venues to avoid bottlenecks or disruption in service provision. As Latino MSM are the only group to experience an increase in HIV incidence during the past four years, it is critical that future studies understand enhanced service delivery for this growing population (4).

Contributor Information

Mariano J. Kanamori, Department of Public Health Sciences, Division of Prevention Science and Community Health, Miller School of Medicine, University of Miami, Miami, FL

Mark L. Williams, Department of Health Policy and Management, Robert Stempel College of Public Health & Social Work, Florida International University, Miami, FL

Kayo Fujimoto, Department of Health Promotion & Behavioral Sciences, School of Public Health, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX

Cho Hee Shrader, Department of Public Health Sciences, Division of Prevention Science and Community Health, Miller School of Medicine, University of Miami, Miami, FL

John Schneider, University of Chicago Medicine; Chicago, IL.

Mario de La Rosa, School of Social Work; Robert Stempel College of Public Health & Social Work, Florida International University, Miami, FL

References

- 1.White House. Office of National AIDS Policy. National HIV/AIDS strategy for the United States: updated to 2020. In: Office of National AIDS Policy, editor. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Latinos | Race/Ethnicity | HIV by Group | HIV/AIDS | CDC 2018 [updated 2018-11-01T02:48:00Z. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/racialethnic/hispaniclatinos/index.html.

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention | HIV Basics | HIV/AIDS | CDC. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2016; vol. 28.; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Fact Sheet: HIV among Latinos. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimated HIV incidence and prevalence in the United States, 2010–2015. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report 2018; 23 (No. 1). 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Valverde EE, Waldrop-Valverde D, Anderson-Mahoney P, Loughlin AM, Del Rio C, Metsch L, et al. System and patient barriers to appropriate HIV care for disadvantaged populations: the HIV medical care provider perspective. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2006;17(3):18–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doll M, Fortenberry JD, Roseland D, McAuliff K, Wilson CM, Boyer CB. Linking HIV-negative youth to prevention services in 12 US cities: barriers and facilitators to implementing the HIV prevention continuum. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2018;62(4):424–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stall R, Friedman M, Catania J. Interacting epidemics and gay men’s health. Unequal opportunity. 2007:251–74. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fujimoto K, Wang P, Kuhns L, Ross MW, Williams ML, Garofalo R, et al. Multiplex competition, collaboration, and funding networks among health and social organizations: Towards organization-based HIV interventions for young men who have sex with men. Medical care. 2017;55(2):102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holloway IW, Rice E, Kipke MD. Venue-based network analysis to inform HIV prevention efforts among young gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men. Prevention Science. 2014;15(3):419–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sowa JE. The collaboration decision in nonprofit organizations: Views from the front line. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly. 2009;38(6):1003–25. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donahue JD, Zeckhauser RJ. Collaborative governance: Private roles for public goals in turbulent times: Princeton University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wan TT, Ma A, Lin BY. Integration and the performance of healthcare networks: do integration strategies enhance efficiency, profitability, and image? International journal of integrated care. 2001;1(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations: Simon and Schuster; 2010.

- 16.Khumalo-Sakutukwa G, Morin SF, Fritz K, Charlebois ED, Van Rooyen H, Chingono A, et al. Project Accept (HPTN 043): a community-based intervention to reduce HIV incidence in populations at risk for HIV in sub-Saharan Africa and Thailand. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2008;49(4):422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abrahamson E, Rosenkopf L. Social network effects on the extent of innovation diffusion: A computer simulation. Organization science. 1997;8(3):289–309. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Latkin C, Knowlton AR. Social network approaches to HIV prevention: implications to community impact and sustainability. Community interventions and AIDS. 2005:105–29. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bertrand JT. Diffusion of innovations and HIV/AIDS. Journal of health communication. 2004;9(S1):113–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kelly JA, St Lawrence JS, Diaz YE, Stevenson LY, Hauth AC, Brasfield TL, et al. HIV risk behavior reduction following intervention with key opinion leaders of population: an experimental analysis. American journal of public health. 1991;81(2):168–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Valente TW, Davis RL. Accelerating the diffusion of innovations using opinion leaders. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 1999;566(1):55–67. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goodwin N It’s good to talk: social network analysis as a method for judging the strength of integrated care. International journal of integrated care. 2010;10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Provan KG, Veazie MA, Staten LK, Teufel-Shone NI. The use of network analysis to strengthen community partnerships. Public Administration Review. 2005;65(5):603–13. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Uzzi B The sources and consequences of embeddedness for the economic performance of organizations: The network effect. American sociological review. 1996:674–98. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kraatz MS. Learning by association? Interorganizational networks and adaptation to environmental change. Academy of management journal. 1998;41(6):621–43. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qualtrics L. Qualtrics [software]. Utah, USA: Qualtrics. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 27.IBM. IBM SPSS Statistics Version 23. Boston, MA: International Business Machines Corp; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Borgatti SP, Everett MG, Freeman LC. Ucinet. Encyclopedia of social network analysis and mining. 2014:2261–7. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bunger AC, Doogan NJ, Cao Y. Building service delivery networks: partnership evolution among children’s behavioral health agencies in response to new funding. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research. 2014;5(4):513–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hermans F, Sartas M, Van Schagen B, van Asten P, Schut M. Social network analysis of multi-stakeholder platforms in agricultural research for development: Opportunities and constraints for innovation and scaling. PloS one. 2017;12(2):e0169634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khosla N, Marsteller JA, Hsu YJ, Elliott DL. Analysing collaboration among HIV agencies through combining network theory and relational coordination. Social Science & Medicine. 2016;150:85–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Provan KG, Milward HB. Integration of community-based services for the severely mentally III and the structure of public funding: A comparison of four systems. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. 1994;19(4):865–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schoen MW, Moreland-Russell S, Prewitt K, Carothers BJ. Social network analysis of public health programs to measure partnership. Social science & medicine. 2014;123:90–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kania J, Kramer M. Collective impact. Stanford social innovation review New York; 2011. [Google Scholar]