Abstract

Aim

There is no consensus in the literature on how best to manage wrist flexion and forearm pronation deformities in children with cerebral palsy (CP). The aim of this research was to come up with a treatment algorithm for the surgical management of such cases.

Methods

Children with CP who underwent upper limb surgery between 2009 and 2016 at a single centre and by a single lead surgeon were reviewed retrospectively. Movement analysis and Shriners Hospital Upper Extremity Evaluation (SHUEE) data collected pre- and post-operatively.

Results

Thirteen patients were recruited. Most patients underwent a flexor carpi ulnaris (FCU) to extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB) transfer, with or without pronator teres (PT) re-routing, and finger flexor or elbow flexor releases. Mean increase in active range of supination was 40.8° (p = 0.002) and wrist extension 28.9° (p = 0.004). The mean increase in dynamic positional analysis (part of the SHUEE) was 25.4% (of which 40.3% was due the increases in wrist function and 16.8% due to forearm function). The loss of wrist flexion was not significant (p = 0.125). The mean follow-up was 14 months (range 9–21).

Conclusions

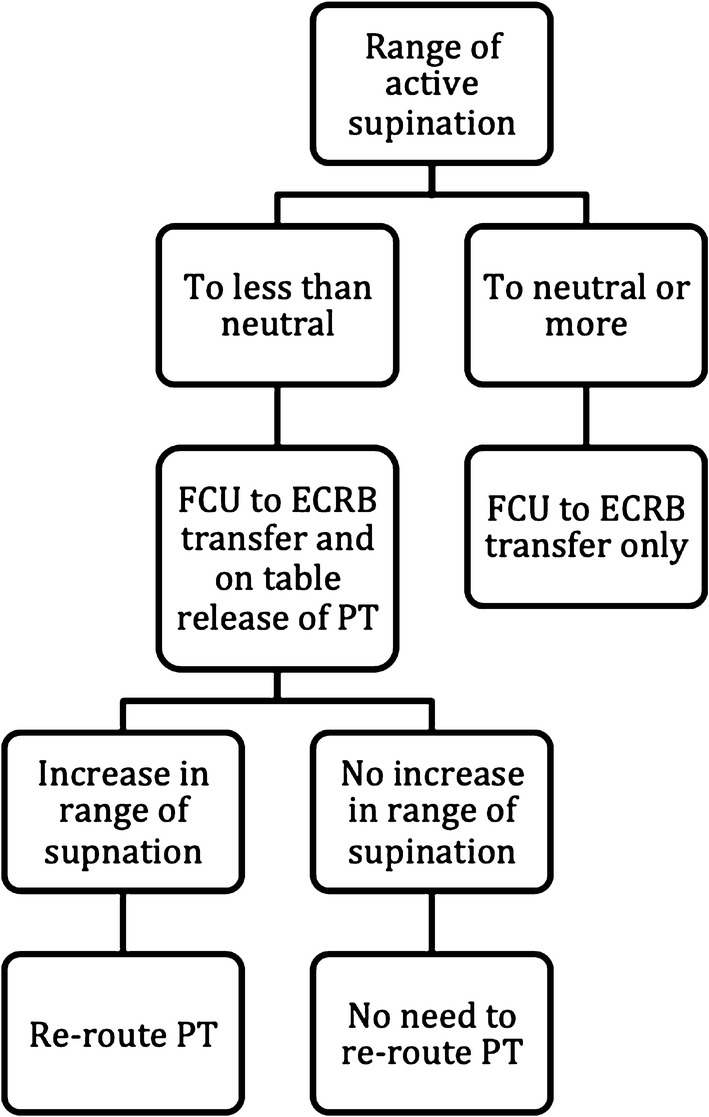

To tackle both a pronation and flexion deformity, the authors favour performing a FCU to ECRB transfer in isolation if there is active supination to neutral; if active supination is short of neutral, then a FCU to ECRB with a PT release and possible re-routing performed. A treatment algorithm is proposed.

Level of evidence

IV.

Keywords: Cerebral palsy, Flexion, Pronation, FCU, ECRB, Paediatrics, Movement analysis, Surgery

Introduction

Cerebral palsy (CP) is a non-progressive and non-hereditary insult to the immature brain with prevalence rate around 1 per 1000 births, typically with resultant muscle spasticity [1]. Reconstructive surgeries of upper extremities are less described in the literature than lower limb surgery. The common upper extremity deformities seen in spastic CP patients are shoulder adduction and internal rotation, elbow flexion, forearm pronation, wrist and finger flexion, and thumb in palm [2]. Pronation contractures are caused by an imbalance between the spastic pronator teres and quadratus muscles, and weaker supinator muscles, as well as spastic wrist and finger flexors.

The significance of these pronation and flexion deformities is not small. Aside from the aesthetics aspect, a pronated forearm position interferes with normal hand and finger use, particularly as patients are not able to see their own palms. A pronated forearm position also exacerbates flexion deformities in the wrist and hand due to the effect of gravity on the wrist in relation to the normal radial incline of the wrist (which favours flexion) [3–5]. When supination is significantly restricted, patients often compensate through other body and shoulder movements. Patients with chronically pronated forearms also run the risk of radial head dislocations, most commonly in a posterolateral direction. Although rare, a dislocated radial head can further limit forearm extension and supination [6].

The treatment options are various and include both non-operative and operative measures. The evidence is scant and when present, there is no consensus in the literature on the surgical management of pronation and flexion deformities of the upper limbs in CP. The aim of this retrospective review was to look at consecutive cases performed in a single centre, looking specifically at the pre- and post-operative range of movement in children with CP who underwent operative correction, and to come up with a treatment algorithm.

Methods

All cases of children with CP who underwent surgery to the upper limb between 2009 and 2016 at a single centre and by a single surgeon were reviewed retrospectively. Inclusion criteria were any paediatric patients who underwent upper limb surgery for malpositioning due to spasticity (n = 25) as determined objectively by upper limb movement analysis including the Shriners Hospital Upper Extremity Evaluation (SHUEE) analysis. Exclusion criteria were patients whose documented pre-operative and post-operative assessment of the range of movement could not be located or they could not comply with the assessment, patients who underwent wrist fusion, or patients who had surgery to the thumb only (n = 12).

Of the patients recruited, their clinical notes and movement analysis data were reviewed retrospectively. Data were retrieved on the pre-operative active range of pronation and supination, elbow flexion and extension and wrist flexion and extension. All patients underwent SHUEE analysis, looking specifically at the Dynamic positional analysis (DPA). Furthermore, data were collected on the type of cerebral palsy (hemiplegic or total body) and the Gross Motor Functional Classification System (GMFCS) score.

The movements tested were as follows:

forearm pronation and supination, with the elbow at 90° of flexion.

elbow flexion and extension with forearm in neutral pronosupination.

wrist dorsi- and palmar-flexion with the elbow at 90° and the forearm in neutral pronosupination.

Forearm pronation and supination with elbow extension were not tested as this is not standard practice in upper limb movement analysis.

Active range of motion was measured in degrees. Pronation and supination were measured separately from neutral (taken to be 0°), that is with the hand parallel to the sagittal plane. Elbow flexion and extension were measured from full extension (taken to be 0°) to full flexion (taken to be 150°). Similarly to forearm pronation and supination, wrist flexion and extension were measured from neutral (taken to be 0°) to full palmar flexion (taken to be 90°) to full dorsiflexion (taken to be 70°). Values in the negative for a given range of supination mean that there was a block to neutral for that movement equivalent to the degrees in the negative.

Tests of normality were performed for all parameters measured. When normally distributed, the mean and standard deviations (SD) were compared using a paired two-tailed t test; for those parameters that failed the test of normality, a Wilcoxon test was used to compare the medians and interquartile ranges (IQR). For both tests, p < 0.05 was taken as significant.

Results

Twenty-five patients were identified in total. 12 were excluded as they did not meet the inclusion criteria as stated above. Of the remaining 13 patients, there were 4 females and 9 males. The average age at time of first surgery was 14 years (range 9–19 years). 12 patients were hemiplegic (eight left, four right) and one patient did not have a definitive classification to the CP. Eight patients had a GMFCS score of 2, one patient had a GMFCS score of 1 and two patients had a GMFCS score of 3. In two patients, the GMFCS score was not documented.

With regards to surgical procedures performed, all patients underwent a flexor carpi ulnaris (FCU) to extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB) transfer in the first instance. Depending on the pre-operative and intra-operative findings, some patients also had a pronator teres (PT) release or re-routing, elbow flexor releases and/or finger flexor muscle releases. One patient underwent bony surgery in the form of a proximal row carpectomy. Here were no bony deformities at the time of writing this paper in this patient. The demographics of the patients recruited and the details of the surgical procedures performed are tabulated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics of children recruited to the study and details on operative procedures performed

| Case | Age at first surgery | Sex | CP type | GMFCS | Operations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 16 | F | Left hemiplegia | 2 | FCU to ECRB transfer |

| 2 | 14 | F | Left hemiplegia | Not documented | FCU to ECRB transfer, PT re-routing, FDS and FPL lengthening, re-routing and reefing of EPL |

| 3 | 11 | M | Right hemiplegia | 2 | FCU to ECRB transfer, PT re-routing, FDS lengthening |

| 4 | 17 | M | Spasticity, not classified | Not documented | FCU to ECRB transfer, biceps and brachoradialis lengthening, PT re-routing, FDS lengthening |

| 5 | 14 | M | Right hemiplegia | 1 | FCU to ECRB transfer |

| 6 | 19 | F | Right hemiplegia | 2 | FCU to ECRB transfer, FDS and FPL release |

| 7 | 13 | M | Left hemiplegia | 2 | FCU to ECRB transfer, EPL re-routing, FPL lengthening |

| 8 | 9 | M | Right hemiplegia | 2 | FCU to ECRB transfer |

| 9 | 15 | M | Left hemiplegia | 3 | FCU to ECRB transfer, biceps and brachoradialis lengthening |

| 10 | 16 | M | Left hemiplegia | 2 | FCU to ECRB transfer, PT re-routing, FDS lengthening, BR to APL transfer, elbow flexor lengthening, thumb web-space release |

| 11 | 11 | F | Left hemiplegia | 2 | FCU to ECRB transfer, PT re-routing |

| 12 | 14 | M | Left hemiplegia | 3 | FCU to ERCB transfer, re-routing and reefing of EPL, thumb adductor release |

| 13 | 12 | M | Left hemiplegia | 2 | FCU to ECRB transfer, PT re-routing, proximal row carpectomy, left elbow flexor release, botulinium toxin to thumb adductor |

CP cerebral palsy, GMFCS gross motor function classification system, PT pronator teres, FCU flexor carpi ulnaris, ECRB extensor carpi radialis brevis, FDS flexor digitorum superficialis, FPL flexor pollicis longus, EPL extensor pollicis longus, BR brachoradialis

The details of the ranges of movement are tabulated in Table 2. The values obtained for supination, wrist extension and DPA were normally distributed. All other parameters failed the test of normality. The active range of supination increased by 40.1° (p = 0.002, df = 12, SD 36.1, 95% CI 18.9–62.6) and active wrist extension by 28.9° (p = 0.004, df = 12, SD 29.5, 95% CI 11.1–46.6). Despite the loss of some flexion at the wrist of 26.9°, this was not statistically significant (p = 0.125). Two patients had no improvement in either the range of supination or wrist extension (cases 1 and 10). In one other patient (case 9), the range of supination didn’t change. In another patient the range of wrist extension didn’t improve (case 4). The change in DPA on the SHUEE was also significant at 19.1 (p = 0.008, df = 12, SD 21.7, 95% CI 6.1–32.2). In those patients who underwent FCU to ECRB transfer only (without PT release or re-routing), the mean increases in supination and wrist extension were 28.6° and 30.0°, respectively.

Table 2.

Details of pre-operative and post-operative ranges of movement, and the average change in the range of movement

| Case | Pre-operative active range of movement | Post-operative active range of movement | Change in active range of movement | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forearm | Elbow | Wrist | Forearm | Elbow | Wrist | Forearm | Elbow | Wrist | ||||||||||

| Pro | Sup | Ext | Flx | Ext | Flx | Pro | Sup | Ext | Flx | Ext | Flx | Pro | Sup | Ext | Flx | Ext | Flx | |

| 1 | 90 | 0 | 0 | 150 | 70 | 90 | 90 | 0 | 0 | 150 | 60 | 90 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | − 10 | 0 |

| 2 | 30 | 0 | − 40 | 150 | − 90 | 90 | 80 | 70 | − 10 | 150 | − 30 | 90 | 50 | 70 | 30 | 0 | 60 | 0 |

| 3 | 90 | 0 | − 5 | 150 | − 50 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 0 | 150 | 30 | 90 | 0 | 90 | 5 | 0 | 80 | 0 |

| 4 | 90 | − 10 | − 45 | 150 | 20 | 90 | 90 | 40 | − 10 | 140 | 15 | 90 | 0 | 50 | 35 | − 10 | − 5 | 0 |

| 5 | 90 | 10 | − 20 | 150 | 0 | 90 | 70 | 20 | − 30 | 150 | 60 | 0 | − 20 | 10 | − 10 | 0 | 60 | − 90 |

| 6 | 90 | 40 | − 30 | 150 | 0 | 90 | 90 | 45 | − 30 | 150 | 20 | 10 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 20 | − 80 |

| 7 | 90 | 0 | 0 | 150 | 10 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 0 | 150 | 30 | 90 | 0 | 90 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 0 |

| 8 | 90 | 45 | 0 | 150 | 30 | 90 | 20 | 90 | 0 | 150 | 70 | 0 | − 70 | 45 | 0 | 0 | 40 | − 90 |

| 9 | 90 | 45 | − 35 | 150 | 15 | 90 | 90 | 45 | − 25 | 150 | 45 | 90 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 30 | 0 |

| 10 | 90 | 0 | − 45 | 150 | 10 | 90 | 90 | 0 | − 30 | 150 | − 10 | 90 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 0 | − 20 | 0 |

| 11 | 90 | − 20 | 0 | 150 | − 20 | 90 | 90 | 10 | 0 | 150 | 10 | 90 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 0 |

| 12 | 90 | 10 | − 10 | 120 | 20 | 90 | 90 | 60 | − 5 | 150 | 70 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 5 | 30 | 50 | − 90 |

| 13 | 90 | 0 | − 45 | 150 | − 20 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 0 | 150 | 0 | 90 | 0 | 90 | 45 | 0 | 20 | 0 |

| Mean (SD) | – | 9.2 | – | – | − 0.4 | – | – | 50.0 | – | – | 28.5 | – | – | 40.8 (36.1) | – | – | 28.9 (29.5) | – |

| Median (IQR) | 90 | – | − 20 | 150 | – | 90 | 90 | – | − 5 | 150 | – | 90 | 0 (0) | – | 5 (15) | 0 (0) | – | 0 (80) |

| p value | 0.750 | 0.002 | 0.047 | 0.999 | 0.004 | 0.125 | ||||||||||||

All measurements are in degrees and refer to the active range of movement. For normally distributed values, mean and paired t test was used. For non-normally distributed values, median and Wilcoxon test was used

Pro pronation, Sup supination, Ext extension, Flx flexion, SD standard deviation, IQR interquartile range

Italicized results are statistically significant

The details of the pre-operative and post-operative SHUEE scores are tabulated in Table 3.

Table 3.

Details of change in SHUEE (Shriners Hospitals Upper Extremity Evaluation) score on pre-operative and post-operative assessment

| Case | Pre-operative | Post-operative | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| DPA | DPA | DPA | |

| 1 | 73 | 83 | 10 |

| 2 | 47 | 53 | 6 |

| 3 | 44 | 74 | 30 |

| 4 | 48 | 83 | 35 |

| 5 | 53 | 93 | 40 |

| 6 | 85 | 75 | 71 |

| 7 | 39 | 90 | 51 |

| 8 | 44 | 99 | 55 |

| 9 | 75 | 71 | − 4 |

| 10 | 53 | 46 | − 7 |

| 11 | 46 | 51 | 5 |

| 12 | 60 | 78 | 18 |

| 13 | 23 | 43 | 20 |

| Mean (SD) | 53.1 | 72.2 | 19.1 (21.7) |

| p value | 0.008 |

SFA spontaneous functional analysis, DPA dynamic positional analysis, SD standard deviation

Italicized results are statistically significant

All children included had movement analysis both pre- and post-operatively. The mean follow-up including movement analysis was 14 months (range 9–21 months). Most had longer clinical follow-up, however, only follow-up that included formal movement analysis was taken into account for the purposes of this study.

Discussion

The treatment of upper limb deformities in CP is complex and there is no clear consensus over how to optimally manage pronation and flexion deformities of the forearm and wrist in these patients. Although there are some reports of positive outcomes of non-operative treatment by cast alone [13–15], most authors advocate operative treatment [2, 5, 9]. Non-operative treatments include physical therapy, the use of splints and casts, and botulinum injections into the pronator and flexor muscles. The surgical options are various and it is often unclear what procedure is best to undertake. The surgical options include tenotomies or fractional lengthening of the pronator muscles, transposition or re-routing of the pronator teres, transfer of the pronator teres or the flexor carpi ulnaris to the extensor carpi radialis brevis muscle (the latter being primarily aimed at improving wrist extension), and a radial rotational osteotomy [4, 7–12].

Gschwind and Tonkin [9] classified the pronation deformity and proposed operative procedures for each category. In their paper, they suggest re-routing or transferring the pronator teres only if there was no active supination but free passive supination. In all other cases requiring surgery, they simply release the pronator quadratus and possibly release the wrist and finger flexors, with or without brachioradialis re-routing. In this series, release of pronator teres rather than pronator quadratus was undertaken because it is often found to be contracted, and the range of supination is found to increase on its release. Furthermore, because the range of movement assessed during direct examination may not correlate to actual functional range during activities, the authors of this series advocate a videotaped evaluation of the patient performing tasks using the Shriners Hospital Upper Extremity Evaluation in addition to formal assessment of the range of upper limb.

Many authors favour re-routing of the pronator teres muscle [8, 14, 15] and have concluded that this is better than pronator teres tenotomy alone [16]. Some have shown good results with a transposition of the pronator teres muscle to the wrist extensor muscles, with or without a pronator quadratus myotomy [7, 9], while others have concluded that a transposition of the flexor carpi ulnaris to the extensor carpi radialis brevis muscle, with or without a lengthening of pronator teres, and re-routing of brachioradialis muscle give the best results [10, 11, 17, 18].

FCU to ECRB transfer is considered the gold standard treatment for flexed wrist by many authors [19, 20]. There is also evidence that this transfer also increases supination due to the biomechanics of the transfer [10]. Furthermore, pronator teres to ECRB transfer also improves wrist extension and shows good results in up to 80% of patients. It has also been shown to improve supination, but this fact remains controversial [10, 21].

The results of this study show that FCU to ECRB transfer is a good option to improve both the range of forearm supination and both elbow and wrist extension. The rationale is choice of procedure was based on both the pre-operative and intra-operative findings as follows. If, at pre-operative assessment, supination to beyond neutral could not be achieved actively then pronator re-routing was performed in addition. In our series, the mean increases in range of supination and wrist extension were 40.8° and 28.9° respectively, both of which were significant (p = 0.002 and p = 0.004, respectively). Elbow flexor lengthening was performed if pre-operatively the patient could not achieve extension to within about 45 degrees of full extension. This was done through myofascial lengthening. Even in those who did not have elbow flexor lengthening, the range of elbow extension also improved significantly post-operatively although this was not an intended aim of the surgery. Finger and thumb flexor tendon lengthening (again with myofascial lengthening) with or without EPL tendon reefing was performed if at the end of the procedure and with the wrist in the corrected position the patient still had a thumb-in-palm contracture and/or clenched fingers. Regardless of procedure, there was no detrimental effect on the range of wrist flexion or pronation of the forearm. This study also confirms that the increase in range of movement is associated with an increase in the DPA score (done as part of the SHUEE) of 25.4 (p = 0.008). Our post hoc analysis of our DPA scores showed that 40.3% and 16.8% of the change came from increases in wrist and forearm movement, respectively. The increase in SHUEE score is corroborated by other investigators, who also found that an increase in SHUEE scores was associated with an improvement in the bodily impairment measures [22]. The combination of range of wrist and forearm movement, specifically increased supination and wrist extension, means that the wrist is in a more functional position and that the grip strength improves as the wrist adopts a position closer to the position of function [23].

The adjunctive quadratus myotomy as recommended by Gschwind and Tonkin [9], which resulted in an up to 40° increase in range of supination in their series, requires an additional surgical approach, with its associated morbidity, and the increase in range of supination from our series was sufficient without it.

The effect of lengthening of elbow flexors is something else that needs to be taken into consideration when planning surgery on these patients. Only 2 of the 4 patients in our series who had elbow flexor lengthening actually had an increase in range of supination and the question on whether lengthening the elbow flexors de-functions the biceps as a supinator should be looked at in the future. Similarly, if on passively positioning the wrist in the position of function the finger flexors are found to be too tight (and may therefore negate the effect of transfers done at the wrist), they need to be lengthened.

The small numbers and the retrospective nature of this study, and therefore the potential for observational bias, are two of the main limitations of this study and this must be kept in consideration when looking at the results. The two main procedures (i.e., FCU to ECRB transfer with or without PT re-routing) were not compared head to head in relation to their effect on active supination, and were often done in conjunction. FCU to ECRB transfer was the preferred operation in our series and it seems that this is likely to be sufficient even if done in isolation (provided that there is active supination ideally to neutral or just beyond). It would make sense that re-routing PT of course also releases it as a pronator. However, it is difficult to know if PT actually becomes an active supinator or whether it is simply defunctioned as a pronator and helps to hold the forearm in a more supinated position. If this were to be looked into, formal electromyographic analysis as part of the post-operative assessment would need to be done. Finally, only the active range was analysed here but other authors have also taken into account the passive range of movement when considering treatment [9]. In our series, passive range of movement was also assessed pre-operatively and intra-operatively, however, because the desired effect is that of a functioning tendon transfer, we opted to analyse only the active range of movement in our patients.

Conclusion

Surgery is an effective tool in the management of pronation and flexion deformities of the forearm and wrist in patients with CP. The algorithm presented in Fig. 1 summarises the practice of the authors in a tertiary centre and is based on results and experience obtained with time. The authors would favour performing a FCU to ECRB transfer in isolation to address both the wrist flexion and pronation deformity. If there is active supination to neutral, this in isolation is often sufficient. If, however, active supination is short of neutral, the authors would recommend performing a FCU to ECRB transfer as well as a release of PT; if passive supination increases further on table, possibly with other soft tissue releases such as releasing the intraosseus membrane, then PT should be re-routed. If the passive range of supination does not increase any further on releasing PT, there is nothing to be gained by re-routing the PT. Finger and elbow flexor releases can be performed as required and as discussed earlier on in the discussion.

Fig. 1.

Summary of the protocol employed by the authors at their centre

Author Contributions

MM: study design, data collection, statistical analysis and writing of paper. JL: data collection and writing of paper. RB: study design, statistical analysis and writing of paper.

Funding

None.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This manuscript represents honest and original work. The manuscript has been read and approved by all the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Odding E, Roebroeck ME, Stam HJ. The epidemiology of cerebral palsy: incidence, impairments and risk factors. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2006;28:183–191. doi: 10.1080/09638280500158422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lomita C, Ezaki M, Oishi S. Upper extremity surgery in children with cerebral palsy. Journal of American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2010;18:160–168. doi: 10.5435/00124635-201003000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Čobeljić G, Rajković S, Bajin Z, et al. The results of surgical treatment for pronation deformities of the forearm in cerebral palsy after a mean follow-up of 17.5 years. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research. 2015;10:106. doi: 10.1186/s13018-015-0251-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El-Said N. Selective release of the flexor origin with transfer of flexor carpi ulnaris in cerebral palsy. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. British. 2001;83(2):259–262. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.83B2.0830259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kreulen M, Smeulders M, Veeger H, Hage J. Movement patterns of the upper extremity and trunk before and after corrective surgery of impaired forearm rotation in patients with cerebral palsy. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 2006;48(6):436–441. doi: 10.1017/S0012162206000958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pletcher D, Hoffer M, Koffman D. Non-traumatic dislocation of the radial head in cerebral palsy. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume. 1976;58(1):104–105. doi: 10.2106/00004623-197658010-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patella V, Martucci G. Transposition of pronator radial teres muscle to the radial extensors of the wrist, in infantile cerebral paralysis An improved operative technique. Italian Journal of Orthopaedics and Traumatology. 1980;6(1):61–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sakellarides H, Mital M, Lenzi W. Treatment of pronation contractures of the forearm in cerebral palsy by changing the insertion of the pronator radii teres. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume. 1981;63(4):645–652. doi: 10.2106/00004623-198163040-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gschwind C, Tonkin M. Surgery for cerebral palsy: part 1. Classification and operative procedures for pronation deformity. The Journal of Hand Surgery: British. 1992;17(4):391–395. doi: 10.1016/S0266-7681(05)80260-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheema T, Firoozbakhsh K, De Carvalho A, Mercer D. Biomechanic comparison of 3 tendon transfers for supination of the forearm. Journal of Hand Surgery. American Volume. 2006;31(10):1640–1644. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ozkan T, Tuncer S, Aydin A, Hosbay Z, Gulgonen A. Brachioradialis re-routing for the restoration of active supination and correction of forearm pronation deformity in cerebral palsy. The Journal of Hand Surgery: British. 2004;29(3):265–270. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsb.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moon E, Howlett J, Wiater B, Trumble T. Treatment of plastic deformation of the forearm in young adults with double-level osteotomies: case reports. Journal of Hand Surgery. American Volume. 2011;36(4):639–646. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2010.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yasukawa A. Upper extremity casting: adjunct treatment for a child with cerebral palsy hemiplegia. Case report. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1990;44(9):840–846. doi: 10.5014/ajot.44.9.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bunata R. Pronator teres rerouting in children with cerebral palsy. Journal of Hand Surgery. American Volume. 2006;31(3):474–482. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2005.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Veeger H, Kreulen M, Smeulders M. Mechanical evaluation of the pronator teres rerouting tendon transfer. The Journal of Hand Surgery: British. 2004;29(3):259–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsb.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strecker W, Emanuel J, Dailey L, Manske P. Comparison of pronator tenotomy and pronator rerouting in children with spastic cerebral palsy. Journal of Hand Surgery. American Volume. 1988;13(4):540–543. doi: 10.1016/S0363-5023(88)80091-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thuilleux B, Tachdjian M. Treatment of flexon-pronation contracture of the wrist in hemiplegic children. Revue de Chirurgie Orthopedique et Reparatrice de l’Appareil Moteur. 1976;62(4):419–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gugger Y, Kalb K, Prommersberger K, van Schoonhoven J. Brachioradialis rerouting for restoration of forearm supination or pronation. Operative Orthopadie und Traumatologie. 2013;25(4):350–359. doi: 10.1007/s00064-012-0205-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koman LA, Sarlikiotis T, Smith BP. Surgery of the upper extremity in cerebral palsy. Orthopedic Clinics of North America. 2010;41(4):519–529. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pollock GA. Surgical treatment of cerebral palsy. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. British Volume. 1962;44:68–81. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.44B1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salazard B, Medina J. The upper limb of children with cerebral palsy: surgical aspects. Chirurgie de la Main. 2008;27(Suppl 1):S215–S221. doi: 10.1016/j.main.2008.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Heest AE, Bagley A, Molitor F, James MA. Tendon transfer surgery in upper-extremity cerebral palsy is more effective than botulinum toxin injections or regular, ongoing therapy. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume. 2015;97(7):529–536. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.M.01577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Driscoll SW, Horii E, Ness R, et al. The relationship between wrist position, grasp size, and grip strength. Journal of Hand Surgery. 1992;17:169–177. doi: 10.1016/0363-5023(92)90136-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]