Abstract

Ganoderma lucidum is a well-known herbal remedy widely used for treating various chronic diseases. Traditionally, the fruiting body is regarded as the medicinal part of this fungus, while recently, the therapeutic potentials of Ganoderma lucidum spore (GLS) is gaining increasing interests. However, detailed knowledge of chemical compositions and biological activities of the spore is still lacking. In this study, high-resolution mass spectrometry and molecular networking were employed for in-depth chemical profiling of GLS, sporoderm-broken GLS (BGLS) and sporoderm-removed GLS (RGLS), leading to the characterization of 109 constituents. The result also showed that RGLS contained more triterpenoids with much higher contents than BGLS and GLS. Moreover, the immunomodulatory activities of BGLS and RGLS were investigated in the zebrafish models of neutropenia or macrophage deficiency. RGLS exhibited more potent activities in alleviating vinorelbine-induced neutropenia or macrophage deficiency, and significantly enhanced phagocytic function of macrophages, which indicated the immunomodulatory activity of GLS was positively correlated with the content of triterpenoids. Further correlation analysis of chemical profiles of GLS and corresponding bioactivities by partial least squares regression identified the potential immunoactive compounds of GLS, including 20-hydroxylganoderic acid G, elfvingic acid A and ganohainanic acid C. Our findings suggest that combining mass spectrometry molecular networking with zebrafish-based bioassays and chemometrics is a feasible strategy to reveal complex chemical compositions of herbal medicines, as well as to discover their potential active constituents.

Keywords: Ganoderma lucidum spore, mass spectrometry molecular networking, zebrafish-based bioassays, immunomodulatory effects, triterpenoids, partial least squares regression

Introduction

Ganoderma lucidum, commonly known as Lingzhi or Reishi, has been used as an herbal remedy in China and many Asian countries for over 2000 years (Zhou et al., 2015; Yuan et al., 2018). According to traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) theory, G. lucidum can tonify “Qi,” and has been revered for its miracle cures and general health promoting benefits (Bishop et al., 2015). Modern scientific studies have proven that this medical macrofungus possesses various bioactivities, including immunomodulation, liver protection, diabetic treatment, anti-tumor and neuroprotective effects (Ahmad, 2018; Cao et al., 2018). Traditionally, the fruiting body of G. lucidum is used as the medicinal part and regarded as the source for many reported activities (Russell and Paterson, 2006; Hsu and Cheng, 2018). Less mature, but potentially even more valuable to therapeutic agent development, is the Ganoderma lucidum spore (GLS), the tiny reproduction unit of the fungus. Recently, GLS is gaining increasing acceptance and popularity as a functional food and nutraceutical, whose efficacy and safety have been suggested by multiple clinical studies in the treatment of cancers (Zhao et al., 2012; Hsu and Cheng, 2018), chronic periodontitis (Nayak et al., 2015) and Alzheimer disease (Wang et al., 2018). Although the use of GLS becomes popular, detailed knowledge of its chemical composition and biological activity is often lacking, as are data on the pharmacodynamics and clinical effects. Additionally, as GLS has outer bilayers of sporoderm, which is mainly composed of chitin and glucan (Lin and Wang, 2006), a variety of sporoderm-breaking techniques have been developed to release the components from the hard and resilient spores (Liu et al., 2005; Soccol et al., 2016). However, only a limited number of studies have been performed to investigate changes in chemical and biological properties of GLS after breaking the spore walls (Chen et al., 2012; Fu et al., 2012; Gao et al., 2013; Xu et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2017), and active constituents of GLS remain elusive (Liu et al., 2011; Yan et al., 2013).

Since its emergence, mass spectrometry (MS) is increasingly perceived as an essential tool in nearly all phases of drug discovery and development, including lead identification, metabolism, pharmacokinetics, and assessment of drug quality and safety (Hofstadler and Sannes-Lowery, 2006; Pacholarz et al., 2012). The hyphenated techniques, such as liquid chromatography-MS (LC-MS), and tandem MS (MS2), which represent the most widely used tools in MS arsenal, have shown many unique strengths in the drug discovery process. Recently, this cutting-edge technique has also been introduced into the realm of natural products and herbal medicines, which have been the source for new pharmaceutical drugs (Newman and Cragg, 2016). Different from synthetic or highly purified drugs, herbal medicines are complex mixtures, which usually contain hundreds of different phytochemicals. These herbal constituents generate thousands of molecular ions and fragment ions in MS analysis, rendering it challenging to annotate the detected chemical signatures. To address this issue, many MS data processing strategies have been developed to accelerate the dereplication and discovery process (Wang et al., 2016b, 2019; Li et al., 2017, 2019). Among these approaches, molecular networking (Watrous et al., 2012) is an emerging tool well suited to this task. Molecular networking visualizes all the ions and their chemical relationships based on MS2 spectra similarity, which is calculated by using a cosine score (Guthals et al., 2012; Quinn et al., 2017). In the generated molecular networks, each node represents a consensus MS2 spectrum (merged spectra with the same precursor ion and similar MS2 spectra), while the edges between the nodes indicate the degree of cosine similarity. Based on the established Global Natural Product Social Molecular Networking (GNPS, https://gnps.ucsd.edu) web platform (Wang et al., 2016a), researchers can elucidate the structure of analogs and structurally related molecules based on their MS spectra (Yang et al., 2013; Allard et al., 2016). Despite the great potential to aid dereplication and structure elucidation, the utility of molecular networking in herbal medicine discovery just begins (Ge et al., 2017; Li et al., 2018; Qiang et al., 2019), and improvements in method performance (e.g., in terms of algorithm, and bioactivity relevance) are still necessary.

Besides its applications in chemical identification, MS has been employed to screen active constituents from complex herbal medicines. Many strategies for active (constituents) identification based on MS have been proposed, which can be separated into two primary categories: the affinity ultrafiltration based strategies which directly detect target-ligand complexes or “free” ligands released from the noncovalent complexes (Chen et al., 2018); and the chemometrics based strategies which investigate the active constituents by correlating chemical profiles of herbal medicines to their bioactive effects (Chang et al., 2018). For example, Yang et al. developed an ultrafiltration high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with diode array detector and mass spectrometry (UF-HPLC-DAD-MS) method to screen tyrosinase inhibitors from mulberry leaves (Yang et al., 2012). Besides, in one of our previous studies, we explored the active constituents of a Chinese medicine (Wenxin Keli) by combining LC-MS, bioassays and an active index approaches (Liu et al., 2018). It is noteworthy that both types of methods own their distinctive pros and cons, and meticulous validation (e.g., in silico docking, dose-response tests, and in vivo pharmacological assays) is necessary when candidates are obtained.

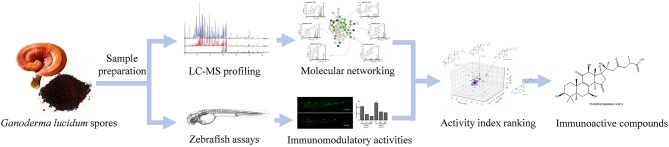

In this work, the active constituents of GLS were investigated by correlating chemical profiles of GLS produced by different manufacturing processes to their respective in vivo activities using partial least squares regression. Molecular networking was employed for structure elucidation and in-depth chemical profiling of GLS. Moreover, the immunomodulatory activities of GLS were evaluated by the zebrafish models of neutrophil or macrophage deficiency, as well as the phagocytic capability of macrophages. The efficiency rate of each constituent was then calculated and ranked based on its peak areas in different GLS samples and the corresponding bioactivities. The experimental workflow is outlined schematically in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Scheme of identifying immunoactive compounds of Ganoderma lucidum spores by molecular networking, zebrafish assays and chemometrics.

Materials and Methods

Materials and Reagents

Ganoderma lucidum spore (GLS, batch No. 14072201), sporoderm-broken Ganoderma lucidum spore (BGLS, batch No. 15121401) and sporoderm-removed Ganoderma lucidum spore (RGLS, batch No. 16042301) were provided by Zhejiang Shouxiangu Institute of Rare Medicine Plant (Zhejiang, China) and the species origin of the samples were authenticated as Ganoderma lucidum (Curtis) P. Karst. by Prof. Mingyan Li in the institute. The samples were kept in the sample room in Pharmaceutical Informatics Institute of Zhejiang University. Vinorelbine (batch No. 140501) was purchased from Jiangsu Haosen Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd (Jiangsu, China). Reference standards including ganoderic acid A, B, C2, D, DM, F, G, H, ganoderenic acid A, B, C, D, lucidenic acid A were purchased from Nature Standard (Shanghai, China).

HPLC-grade acetonitrile and methanol were purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Formic acid (HPLC grade) was purchased from Roe Scientific (Newark, DE, USA). Ethanol and Methylcellulose were acquired from Shanghai Aladdin Bio-Chem Technology (Shanghai, China). Neutral red was purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Saint-Louis, MO, USA). Isopropyl alcohol was purchased from Hangzhou Changzheng Chemical Reagent (Hangzhou, China). Deionized water was prepared with an Elga PURELAB flex system (ELGA LabWater, UK).

Sample Preparation

2 mg of GLS, BGLS, and RGLS were dissolved in 1 mL methanol respectively, and ultrasonically extracted for 20 min, and then centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatants were collected for LC-MS analysis.

BGLS and RGLS were dissolved in system fish water at 10 mg/mL respectively, which were used for zebrafish assays. The system fish water was composed of 200 mg Instant Ocean Salt in per litter of reverse osmosis water with final pH 6.9–7.2, conductivity 480–510 μS/cm, and hardness of 53.7–71.6 mg/L CaCO3.

Instrumentation

An Acquity UPLC system (Waters, Milford, MA, USA) coupled with a Triple TOF 5600plus MS (AB SCIEX, Framingham, MA, USA) was employed for chemical identification. Analysis was performed in negative electrospray ionization (ESI-) mode under following parameters: scan range, m/z 100–1500; source voltage, −4.5 kV; source temperature, 550°C; curtain gas, 35 psi; gas 1 (N2), 50 psi; gas 2 (N2), 50 psi. Declustering potential (DP), collision energy (CE) and collision energy spread (CES) of information dependent acquisition (IDA)-mediated MS2 were 100 V, 40 eV, and 20 eV, respectively.

Chromatographic separation was carried out on an Acquity BEH C18 column (100 mm × 2.1 mm, 1.7 μm, Waters) at 30°C with mobile phase A (0.1% v/v formic acid-water) and mobile phase B (acetonitrile). The flow rate was 0.4 mL/min and a linear gradient elution was programmed: 0–20 min, 20–40% B; 20–28 min, 40–50% B; 28–35 min, 50–70% B; 35–40 min, 70–80% B; 40–45 min, 80–90% B; 45–50 min, 90–95% B; 50–55 min, 95% B. The injection volume was 2 μL.

Construction of MS/MS Based Molecular Network

Tandem mass spectrometry molecular networks were generated using the GNPS platform (https://gnps.ucsd.edu/). Raw MS data were first converted to mzXML format with MSConvert (Kessner et al., 2008) and then uploaded to GNPS to create the molecular networks. The precursor ion mass tolerance was set to 0.5 Da and to a product ion tolerance of 0.1 Da. A network was constructed using 6 minimum matched peaks and a cosine score above 0.7. The spectra in the network were searched against the spectral libraries on GNPS. Results were open and visualized in Cytoscape 3.7.1.

Zebrafish Husbandry and Management

Tg (mpx:GFP) transgenic zebrafish that expressed GFP exclusively in neutrophils and Albino zebrafish were provided by Hunter Biotechnology, which is accredited by the International Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC). Embryos were generated by natural pair-wise mating, and anesthetized in 0.016% (w/v) tricaine prior to observations.

Zebrafish Model of Neutropenia

2-dpf Tg (mpx:GFP) transgenic zebrafish embryos were distributed into 6-well plates, with 30 larvae in 3 mL system fish water for each well. Three groups, i.e., the control group, the model group and the treatment group, were set up. Vinorelbine was administered at 1 ng per larva by intravenous microinjection to generate the zebrafish model of neutropenia. The treatment group was incubated in BGLS or RGLS supplemented fish water after microinjection. The final concentrations of BGLS (22, 67, and 200 μg/mL) and RGLS (33, 100, and 300 μg/mL) were set according to the maximum tolerated concentrations (MTCs) assay (Supplementary Methods). All the groups were incubated in a 28°C incubator for 24 h. Ten larvae were randomly selected from each group and the numbers of neutrophils in the zebrafish were counted and recorded with a Nikon Multi-purpose Zoom Microscope AZ100. The neutrophil recovery rate was calculated using the following formula:

where Ntreatment and Nmodel were the numbers of neutrophils of the larvae in the treatment group and model group, respectively.

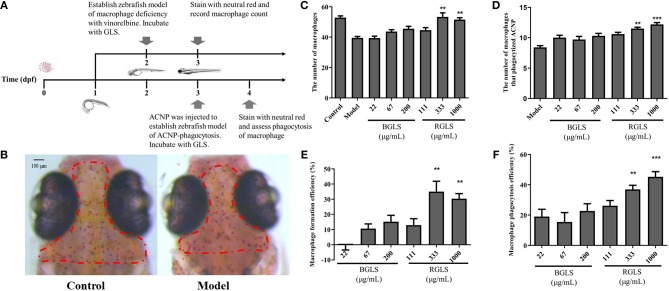

Zebrafish Model of Macrophage Deficiency

2-dpf Albino zebrafish embryos were distributed into 6-well plates, with 30 larvae in each well with 3 mL system fish water. Three groups were designed, including the control group, the model group and the treatment group. Vinorelbine was administered at 0.25 ng per larva by intravenous microinjection to generate the zebrafish model of macrophage deficiency. The treatment group was incubated in BGLS or RGLS supplemented fish water after microinjection. The final concentrations of BGLS (22, 67 and 200 μg/mL) and RGLS (111, 333 and 1000 μg/mL) were set according to the MTC assay in the Albino zebrafish (Supplementary Material). After 48 h incubation, the embryos were stained with 3 mL neutral red (2.5 μg/mL). Subsequently, the zebrafish embryos were immobilized in 3% methylcellulose, and the number of macrophages were counted and recorded with a Nikon dissecting microscope SMZ645. The macrophage formation efficiency was calculated using the following formula:

where Ntreatment and Nmodel were the numbers of macrophages of the larvae in the treatment group and model group, respectively.

Zebrafish Model of Macrophage Phagocytosis

A zebrafish model of PM2.5 phagocytosis was used to assess the phagocytic function of macrophages under the effect of BGLS or RGLS. The model was created by injecting 10 nL active carbon nanoparticles (ACNP, 2.3 mg/mL) to 3-dpf Albino zebrafish. The group design and the tested concentrations were identical to the macrophage deficiency assay. After 24 h incubation, embryos were stained with 3 mL neutral red (2.5 μg/mL) and immobilized in 3% methylcellulose. The number of macrophages that phagocytized ACNP was then counted with a Nikon dissecting microscope SMZ645. The macrophage phagocytosis efficiency was calculated using the following formula:

where Ntreatment and Nmodel were the numbers of macrophages that phagocytized ACNP in the treatment group and model group, respectively.

Statistical Analysis

The data obtained from zebrafish assays was analyzed with GraphPad prism 7 software (GraphPad Software, USA). Parameter comparisons between groups were made with one-way ANOVA analysis of variance. The result was considered statistically significant when P-value < 0.05.

Results and Discussion

Molecular Networking to Profile Ganoderma lucidum Spores

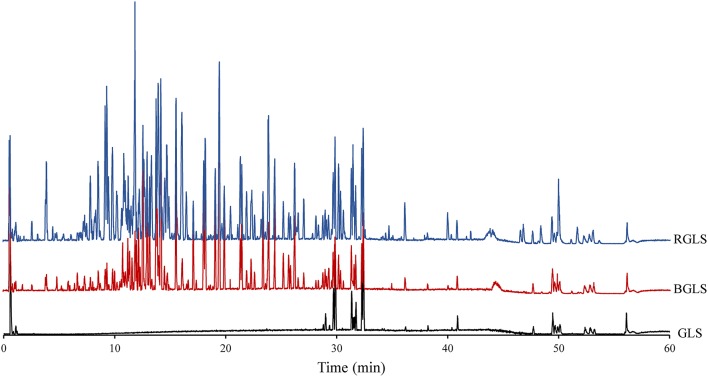

Representative UPLC–Q–TOF/MS chromatograms of GLS (raw material), sporoderm-broken Ganoderma lucidum spores (BGLS) and sporoderm-removed Ganoderma lucidum spores (RGLS) are shown in Figure 2. Apparently, the chemical profiles of these samples varied considerably. Only a few peaks were detected in the chromatogram of GLS, which suggested that the intact sporoderm acted as a barrier against the release of constituents inside the spores. In comparison, both BGLS and RGLS had much more peaks than GLS. The peak intensities of RGLS were higher than those of BGLS, which could be ascribed to the removal of the sporoderm in RGLS.

Figure 2.

Representative base peak chromatograms of different Ganoderma lucidum spore samples obtained by LC-QTOF-MS in negative ion mode. BGLS, Ganoderma lucidum spore; BGLS, sporoderm-broken Ganoderma lucidum spore; RGLS, sporoderm-removed Ganoderma lucidum spore.

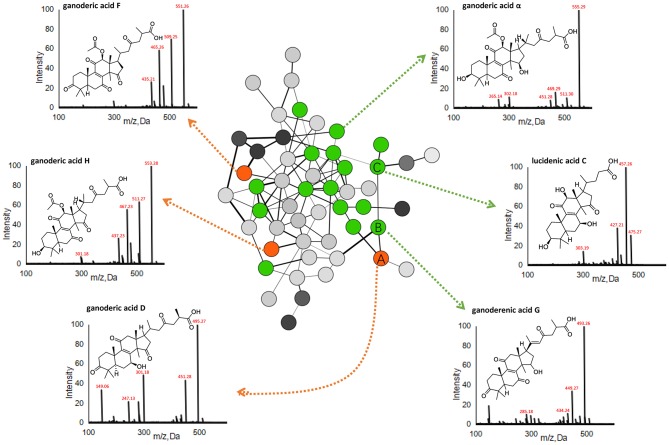

Given the large quantity of constituents with diverse chemical structures in the spore, we next employed molecular networking for chemical identification, and focused on RGLS, which had the most peaks with higher intensities. The molecular network of RGLS based on MS2 spectra similarity was created on GNPS, which contained 501 distinguishable precursor ions, visualized as nodes in the network with 68 clusters (node ≥2), and 186 single nodes. Constituents were then identified and dereplicated through automatic searching in the spectral libraries on GNPS. Besides molecular networking, targeted LC-MS analysis was also conducted to assist the identification based on several strategies developed in our previous studies (Xiao et al., 2014; Li et al., 2015). Briefly, molecular formulae were first generated according to the high-resolution MS data, then the putative identification of the peaks was assigned based on literature and database matching, and was further confirmed via MS2 fragmentations. In addition, 13 constituents were unambiguously confirmed by comparisons with chemical standards in terms of retention time and mass spectra (Table 1). Nodes in the network corresponding to precursor ions of the 13 constituents were positioned and used to propagate molecular annotations, which accelerated dereplication of structurally related molecules. By applying these approaches, a total of 20, 96, and 109 constituents were identified or tentatively characterized from GLS, BGLS, and RGLS, respectively, including 99 triterpenoids, one linoleic acid, and 9 potentially new compounds (Table 1). Taking the cluster in Figure 3 as an example, node A showed a quasi-molecular ion [M-H]− at m/z 513.2850, giving the formula C30H42O7. Fragment ions at m/z 495, 451, and 436 corresponded to successive losses of H2O, CO2, and CH3. Fragment ions at m/z 301 and 285 were characteristic ions formed by the cleavage of the D-ring ([M-H-C11H16O4]−) and the subsequent loss of CH4. In addition, this node showed identical retention time and similar mass spectra with those of the reference standard ganoderic acid D. Thus, this compound was unambiguously assigned as ganoderic acid D. Node B, which was adjacent to node A with high MS2 spectral similarity, showed 2 Da difference in the quasi-molecular ion and many fragment ions, indicating the two compounds shared similar structures. Moreover, node B exhibited identical fragments at m/z 301 and 285 with node A, which represented their A-, B-, and C-ring might be identical. Therefore, this compound was rapidly identified as ganoderenic acid G, with only one double-bond difference in the side chain. Likewise, as the neighbor of node B, node C exhibited a similar fragmentation pattern with node A and B, thus was identified as lucidenic acid C. Therefore, combining molecular networking with targeted MS analysis, large-scale MS dataset can be explored rapidly without any prior knowledge regarding the chemical compositions of the samples, and greatly facilitated the discovery of novel analogs. Detailed MS information is displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characterization of constituents in Ganoderma lucidum spore by LC-QTOF-MS.

| No. | RT (min) | Identity | Observed m/z (+/-) | Molecular formula | Error (ppm) | Major fragments | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4.119 | Lucidenic acid J | 489.2485 | C27H38O8 | −1.8 | 489.2513 [M-H]− 471.2390 [M-H-H2O]− 459.2059 [M-H-2CH3]− 441.1925 [M-H-CH4O-CH3]− 346.1427 [M-H-CH3-C7H12O2]− 318.1485 [M-H-C8H12O3-CH3]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 2 | 4.426 | Elfvingic acid G | 545.2745 | C30H42O9 | −2.0 | 545.2770 [M-H]− 527.2667 [M-H-H2O]− 497.2224 [M-H-H2O-2CH3]− 483.2750 [M-H-H2O-CO2]− 477.2869 [M-H-2H2O-2CH4]− 453.2273 [M-H-H2O-CO2-2CH3]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 3 | 4.745 | Lucidenic acid C | 475.2688 | C27H40O7 | −2.8 | 475.2712 [M-H]− 457.2608 [M-H-H2O]− 265.1417 [M-H-C12H18O3]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 4 | 4.782 | Ganoderic acid L | 533.3109 | C30H46O8 | −2.0 | 533.3146 [M-H]− 515.3015 [M-H-H2O]− 317.1723 [M-H-C10H16O4]− 303.1591 [M-H-C11H18O5]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 5 | 4.817 | 20-hydroxylganoderic acid G | 547.2898 | C30H44O9 | −2.7 | 547.2974 [M-H]− 529.2858 [M-H-H2O]− 503.2624 [M-H-CO2]− 485.2930 [M-H-H2O-CO2]− 399.2180 [M-H-C6H10O3]− 129.0507 [M-H-C24H32O5]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 6 | 4.983 | Elfvingic acid D | 545.2748 | C30H42O9 | −1.5 | 545.2757 [M-H]− 527.2741 [M-H-H2O]− 509.2525 [M-H-2H2O]− 501.2896 [M-H-CO2]− 415.2188 [M-H-C6H10O3]− 129.0549 [M-H-C24H32O6]− |

RGLS |

| 7 | 5.184 | Unknown | 543.2593 | C30H40O9 | −1.2 | 543.2629 [M-H]− 525.2499 [M-H-H2O]− 499.2739 [M-H-CO2]− 495.2378 [M-H-H2O-2CH3]− 481.2601 [M-H-H2O-CO2]− 455.2837 [M-H-C3H4O3]− 437.2696 [M-H-C3H4O3-H2O]− 407.2274 [M-H-C3H4O3-H2O-2CH3]− 301.1789 [M-H-C11H12O5-H2O]− 249.1469 [M-H-C15H22O5-H2O]− 149.0944 [M-H-C15H20O5-C6H12O2]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 8 | 5.337 | Elfvingic acid E | 545.2748 | C30H42O9 | −1.5 | 545.2769 [M-H]− 527.2691 [M-H-H2O]− 497.2214 [M-H-H2O-2CH3]− 483.2779 [M-H-H2O-CO2]− 453.2277 [M-H-H2O-2CH3-CO2]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 9 | 5.417 | 3b,7b,12-Trihydroxy-4-(hydroxymethyl)-11,15,23-trioxolanost-8-en-26-oic acid | 547.2904 | C30H44O9 | −1.6 | 547.2912 [M-H]− 529.2827 [M-H-H2O]− 511.2719 [M-H-2H2O]− 485.2896 [M-H-H2O-CO2]− 467.2808 [M-H-H2O-CO2-H2O]− 265.1436 [M-H-C15H22O5]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 10 | 5.501 | Ganoderic acid η | 531.2946 | C30H44O8 | −3.3 | 531.2934 [M-H]− 513.2875 [M-H-H2O]− 469.2942 [M-H-H2O-CO2]− 454.2739 [M-H-H2O-CO2-CH3]− 319.1917 [M-H-C11H16O4]− 301.1787 [M-H-C11H16O4-H2O]− 265.1427 [M-H-C15H22O4]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 11 | 5.975 | 20-hydroxylucidenic acid F | 471.2377 | C27H36O7 | −2.4 | 471.2372 [M-H]− 441.2320 [M-H-2CH3]− 427.2480 [M-H-CO2]− 409.2368 [M-H-CO2-H2O]− 367.2317 [M-H-C3H6O2-2CH3]− 337.2166 [M-H-C3H6O2-4CH3]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 12 | 6.136 | Ganoderic acid I | 531.2952 | C30H44O8 | −2.2 | 531.2970 [M-H]− 513.2873 [M-H-H2O]− 483.2382 [M-H-H2O-2CH3]− 401.2298 [M-H-C6H10O3]− 129.0556 [M-H-C24H34O5]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 13 | 6.189 | Lucidenic acid G | 475.2685 | C27H40O7 | −3.4 | 475.2707 [M-H]− 457.2609 [M-H-H2O]− 439.2748 [M-H-2H2O]− 427.2132 [M-H-H2O-2CH3]− 409.2020 [M-H-3H2O-CH3]− 385.2380 [M-H-C2H4O2-H2O-CH3]− 303.1952 [M-H-C8H10O3-H2O]− 287.1650 [M-H-C8H10O3-H2O-CH3]− 285.1861 [M-H-C8H12O3-H2O-CH3]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 14 | 6.75 | Methyl lucidenate E2 | 515.3005 | C30H44O7 | −1.8 | 515.3032 [M-H]− 453.3007 [M-H-C2H2O]− 441.2659 [M-H-C3H6O2]− 426.2421 [M-H-C3H6O2-CH3]− 407.2220 [M-H-C3H6O2-CH4-H2O]− 303.2000 [M-H-C11H16O4]− 249.1502 [M-H-C15H22O4]− 137.0622 [M-H-C21H30O6]− 73.0301 [M-H-C26H34O6]− |

RGLS |

| 15 | 6.956 | 20-hydroxylucidinic acid A | 473.2536 | C27H38O7 | −1.9 | 473.2559 [M-H]− 443.2080 [M-H-2CH3]− 302.1497 [M-H-C8H12O4-H]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 16 | 7.054 | Lucidenic acid M | 461.2895 | C27H42O6 | −3.0 | 461.2917 [M-H]− 417.3016 [M-H-CO2]− 302.1915 [M-H-C8H14O3-H]− 301.1775 [M-H-C8H16O3]− 287.1648 [M-H-C8H16O3-CH3]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 17a | 7.243 | Ganoderenic acid C | 515.3005 | C30H44O7 | −2.2 | 515.3050 [M-H]− 303.1968 [M-H-C11H16O4]− 211.0985 [M-H-C19H28O3]− 193.0863 [M-H-C19H28O3-H2O]− |

RGLS |

| 18 | 7.287 | Elfvingic acid H | 529.2798 | C30H42O8 | −1.7 | 529.2836 [M-H]− 511.2720 [M-H-H2O]− 481.2263 [M-H-H2O-2CH3]− 467.2814 [M-H-H2O-CO2]− 437.2330 [M-H-H2O-CO2-2CH3]− 303.1594 [M-H-C11H14O5]− 261.1488 [M-H-C15H24O4]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 19 | 7.539 | Lucidenic acid C | 475.2690 | C27H40O7 | −2.4 | 475.2698 [M-H]− 457.2593 [M-H-H2O]− 439.2490 [M-H-2H2O]− 427.2140 [M-H-H2O-2CH3]− 409.2018 [M-H-3H2O-CH3]− 303.2026 [M-H-C8H10O3-H2O]− 287.1619 [M-H-C8H10O3-H2O-CH3]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 20 | 7.858 | Butyl lucidenate E2 | 571.2908 | C32H44O9 | −0.8 | 571.2950 [M-H]− 529.2833 [M-H-C2H2O]− 511.2745 [M-H-C2H4O2]− 499.2366 [M-H-C2H2O-2CH3]− 497.2579 [M-H-C2H2O-2CH4]− |

BGLS, RGLS, GLS |

| 467.2823 [M-H-C2H4O2-CO2]− 455.2459 [M-H-C2H4O2-CO2-H2O]− 440.2232 [M-H-C2H4O2-CO2-H2O-CH3]− 425.1991 [M-H-C2H4O2-CO2-H2O-2CH3]− |

|||||||

| 21a | 7.868 | Ganoderic acids C2 | 517.3165 | C30H46O7 | −1.1 | 517.3205 [M-H]− 499.3087 [M-H-H2O]− 455.3166 [M-H-H2O-CO2]− 437.3088 [M-H-H2O-CO2-H2O]− 303.1961 [M-H-C11H18O4]− 301.1806 [M-H-C11H20O4]− 287.1646 [M-H-C11H18O4-CH4]− 249.1494 [M-H-C15H24O4]− |

BGLS, RGLS, GLS |

| 22 | 7.964 | Elfvingic acid B | 527.2642 | C30H40O8 | −1.6 | 527.2662 [M-H]− 509.2569 [M-H-H2O]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 479.2095 [M-H-H2O-2CH3]− 465.2664 [M-H-H2O-CO2]− 435.2190 [M-H-H2O-CO2-2CH3]− 330.1473 [M-H-C10H16O4-H]− |

|||||||

| 23 | 8.229 | iso-ganoderic acid G | 531.2953 | C30H44O8 | −2.0 | 531.3005 [M-H]− 513.2891 [M-H-H2O]− 469.2979 [M-H-H2O-CO2]− 451.2869 [M-H-2H2O-CO2]− 303.1953 [M-H-C11H16O5]− 287.1639 [M-H-C11H16O5-CH3]− 265.1443 [M-H-C15H22O4]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 24 | 8.268 | Ganoderic acid θ | 529.2800 | C30H42O8 | −1.3 | 511.2724 [M-H-H2O]− 481.2258 [M-H-H2O-2CH3]− 467.2823 [M-H-H2O-CO2]− 449.2697 [M-H-H2O-CO2-H2O]− 437.2347 [M-H-H2O-2CH3-CO2]− 303.1588 [M-H-C11H14O5]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 25 | 8.268 | Elfvingic acid F | 545.2751 | C30H42O9 | −0.9 | 545.2775 [M-H]− 527.2713 [M-H-H2O]− 415.2153 [M-H-C6H10O3]− 397.2028 [M-H-C11H18O5-H2O]− 283.1693 [M-H-C16H16O5-H2O-CH4]− 129.0546 [M-H-C24H32O6]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 26 | 8.349 | Lucidenic acid N | 459.2745 | C27H40O6 | −1.6 | 459.2772 [M-H]− 441.2644 [M-H-H2O]− 287.2004 [M-H-C8H12O3-CH3]− 249.1482 [M-H-C12H18O3]− 209.1176 [M-H-C11H22O3]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 27 | 8.575 | Ganoderic acid C6 | 529.2800 | C30H42O8 | −1.3 | 511.2734 [M-H-H2O]− 481.2264 [M-H-H2O-2CH3]− 467.2832 [M-H-H2O-CO2]− 437.2357 [M-H-H2O-CO2-2CH3]− 303.1593 [M-H-H-C11H14O5]− |

BGLS, RGLS, GLS |

| 28 | 8.814 | Dehydrolucidenic acid N | 457.2589 | C27H38O6 | −1.4 | 457.2603 [M-H]− 413.2696 [M-H-CO2]− 397.2389 [M-H-CO2-CH3]− 385.2388 [M-H-CO2-2CH3]− 353.2489 [M-H-CO2-2CH3-2H2O]− 285.1824 [M-H-C8H10O3-H2O]− 249.1475 [M-H-C12H16O3]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 29 | 8.876 | Elfvingic acid A | 527.2644 | C30H40O8 | −1.2 | 527.2660 [M-H]− 509.2572 [M-H-H2O]− 497.2231 [M-H-2CH3]− 479.2083 [M-H-H2O-2CH3]− 465.2688 [M-H-H2O-CO2]− 453.2293 [M-H-2CH3-CO2]− 435.2181 [M-H-2CH3-H2O-CO2]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 30a | 9.199 | Ganoderic acid G | 531.2955 | C30H44O8 | −1.6 | 513.2876 [M-H-H2O]− 469.2993 [M-H-H2O-CO2]− 451.2874 [M-H-2H2O-CO2]− 436.2661 [M-H-2H2O-CO2-CH3]− 303.1973 [M-H-C11H16O5]− 287.1635 [M-H-C11H16O5-CH3]− 265.1427 [M-H-C15H22O4]− 249.1474 [M-H-C15H22O5]− |

BGLS, RGLS, GLS |

| 31 | 9.225 | Elfvingic acid C | 529.2797 | C30H42O8 | −1.9 | 529.2873 [M-H]− 511.2732 [M-H-H2O]− 467.2840 [M-H-H2O-CO2]− 449.2721 [M-H-H2O-CO2-H2O]− 318.1837 [M-H-C10H14O4-CH3]− 301.1832 [M-H-C11H16O5]- |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 32 | 9.272 | Lucidenic acid P | 517.2799 | C29H42O8 | −1.5 | 517.2826 [M-H]− 499.2721 [M-H-H2O]− 475.2706 [M-H-C2H2O]− 457.2609 [M-H-C2H4O2]− 439.2506 [M-H-C2H4O2-H2O]− 427.2131 [M-H-C2H4O2-2CH3]− 409.2024 [M-H-C2H4O2-2H2O-CH3]− 303.1987 [M-H-C2H4O2-C8H10O3]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 33a | 9.504 | Ganoderenic acid B | 513.2852 | C30H42O7 | −1.1 | 559.2908 [M-H+FA]− 513.2882 [M-H]− 495.2767 [M-H-H2O]− 451.2869 [M-H-H2O-CO2]− 436.2628 [M-H-H2O-CO2-CH3]− 421.2393 [M-H-H2O-CO2-2CH3]− 331.1912 [M-H-C10H14O3]− 303.1964 [M-H-C11H14O4]− 249.1491 [M-H-C15H20O4]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 34 | 9.582 | Lucidenic acid I | 473.2532 | C27H38O7 | −2.7 | 473.2572 [M-H]− 455.2459 [M-H-H2O]− 437.2368 [M-H-2H2O]− 425.1966 [M-H-H2O-2CH3]− 301.1790 [M-H-C8H10O3-H2O]− 285.1484 [M-H-C8H10O3-H2O-CH3]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 35 | 9.81 | 12-deacetylganoderic acid H | 529.2803 | C30H42O8 | −0.7 | 529.2833 [M-H]− 511.2734 [M-H-H2O]− 493.2637 [M-H-2H2O]− 467.2820 [M-H-H2O-CO2]− 301.1808 [M-H-C11H16O5]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 36 | 9.854 | ganoderic acid GS-1 | 497.2904 | C30H42O6 | −1.4 | 527.2672 [M-H]− 509.2561 [M-H-H2O]− 491.2453 [M-H-2H2O]− 465.2645 [M-H-H2O-CO2]− 447.2541 [M-H-2H2O-CO2]− 301.1801 [M-H-C11H14O5]− 299.1644 [M-H-C11H16O5]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 37 | 9.858 | Ganoderic acid ε or ganoderic acid δ | 515.3009 | C30H44O7 | −1.0 | 561.3045 [M-H+FA]− 515.3040 [M-H]− 497.2931 [M-H-H2O]− 471.3157 [M-H-CO2]− 341.2115 [M-H-C8H12O3-H2O]− |

BGLS, RGLS, GLS |

| 38 | 10.235 | Unknown | 513.2851 | C30H42O7 | −1.3 | 513.2897 [M-H]− 495.2782 [M-H-H2O]− 451.2871 [M-H-H2O-CO2]− 436.2629 [M-H-H2O-CO2-CH3]− 301.1796 [M-H-C11H16O4]− 249.1476 [M-H-C15H20O4]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 39 | 10.287 | Lucidenic acid E2 | 515.2648 | C29H40O8 | −0.5 | 515.2701 [M-H]− 473.2575 [M-H-C2H2O]− 443.2099 [M-H-C3H4O2]− |

BGLS, RGLS, GLS |

| 40 | 10.679 | 12β-acetoxy-7β-hydroxy-3,11,15,23-tetraoxo-5α-lanost-8-en-26-oic acid | 571.2911 | C32H44O9 | −0.3 | 571.2943 [M-H]− 553.2838 [M-H-H2O]− 511.2734 [M-H-C2H4O2]− 467.2835 [M-H-C2H4O2-CO2]− 449.2720 [M-H-C2H2O2-CO2-H2O]− 303.1973 [M-H-C11H12O4-C2H4O2]− |

BGLS, RGLS, GLS |

| 41 | 10.683 | Lucidenic acid K | 471.2382 | C27H36O7 | −1.3 | 471.2398 [M-H]− 453.2310 [M-H-H2O]− 441.1926 [M-H-2CH3]− 300.1348 [M-H-C8H10O4-H]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 42 | 10.875 | Ganoderic acid α | 573.3061 | C32H46O9 | −1.4 | 573.3061 [M-H]− 555.2990 [M-H-H2O]− 511.3083 [M-H-H2O-CO2]− 469.2987 [M-H-C4H6O2-H2O]− 451.2862 [M-H2O-CO2-C2H4O2]− 265.1439 [M-H-C17H24O5]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 43 | 10.972 | Lucidenic acid B | 473.2534 | C27H38O7 | −2.3 | 473.2566 [M-H]− 455.2454 [M-H-H2O]− 437.2338 [M-H-2H2O]− 425.1965 [M-H-H2O-2CH3]− 422.2109 [M-H-2H2O-CH3]− 407.1881 [M-H-2H2O-2CH3]− 301.1806 [M-H-C8H10O3-H2O]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 44 | 11.025 | Ganoderic acid V1 | 513.2850 | C30H42O7 | −1.5 | 513.2883 [M-H]− 495.2767 [M-H-H2O]− 301.1822 [M-H-C11H16O4]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 285.1513 [M-H-C11H14O4-H2O]− 193.0865 [M-H-C19H26O3-H2O]− |

|||||||

| 45 | 11.139 | Applanoxidic acid G | 527.2642 | C30H40O8 | −1.6 | 527.2696 [M-H]− 509.2568 [M-H-H2O]− 479.2112 [M-H-H2O-2CH3]− 465.2675 [M-H-H2O-CO2]− 435.2198 [M-H-H2O-CO2-2CH3]− 301.1454 [M-H-C11H14O5]− 299.1658 [M-H-C11H16O5]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 46 | 11.287 | Lucidenic acid Q | 459.2743 | C27H40O6 | −2.0 | 505.2799 [M-H+FA]− 441.2610 [M-H-H2O]− 397.2714 [M-H-H2O-CO2]− 299.1634 [M-H-C8H16O3]− 285.1477 [M-H-C8H16O3-H2O]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 47 | 11.529 | Ganoderic acid N | 529.2800 | C30H42O8 | −1.3 | 529.2854 [M-H]− 511.2741 [M-H-H2O]− 467.2831 [M-H-H2O-CO2]− 449.2744 [M-H-2H2O-CO2]− 285.1492 [M-H-C11H14O4-H2O-CH4]− 263.1283 [M-H-C15H22O4]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 48 | 11.549 | Applanoxidic acid C | 525.2484 | C30H38O8 | −1.9 | 525.2543 [M-H]− 507.2411 [M-H-H2O]− 477.1950 [M-H-H2O-2CH3]− 463.2493 [M-H-H2O-CO2]− 433.2030 [M-H-H2O-2CH3-CO2]− 328.1312 [M-H-C10H13O4]− 299.1631 [M-H-C11H14O5]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 49 | 11.558 | 3β-hydroxy-12β-acetoxyganodernoid D | 569.2751 | C32H42O9 | −0.9 | 569.2776 [M-H]− 551.2675 [M-H-H2O]− 509.2562 [M-H-H2O-C2H2O]− 479.2092 [M-H-H2O-C2H2O-2CH3]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 465.2648 [M-H-H2O-C2H2O-CO2]− 435.2174 [M-H-H2O-C2H2O-CO2-2CH3]− 345.1687 [M-H-C11H14O4-CH3]− 330.1467 [M-H-C11H14O4-2CH3]− 301.1784 [M-H-C11H12O4-C2H4O2]− |

|||||||

| 50 | 11.611 | Ganoderic acid O | 527.2643 | C30H40O8 | −1.4 | 527.2672 [M-H]− 509.2561 [M-H-H2O]− 491.2453 [M-H-2H2O]− 465.2645 [M-H-H2O-CO2]− 447.2541 [M-H-2H2O-CO2]− 301.1801 [M-H-C11H14O5]− 299.1644 [M-H-C11H16O5]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 51a | 11.827 | Ganoderic acid H | 571.2909 | C32H44O9 | −0.6 | 553.2828 [M-H-H2O]− 511.2720 [M-H-C2H4O2]− 509.2928 [M-H-H2O-CO2]− 481.2244 [M-H-C2H4O2-2CH3]− 467.2342 [M-H-H2O-CO2-C2H2O2]− 437.2342 [M-H-H2O-CO2-C2H2O2-2CH3]− 449.2701 [M-H-C2H4O2-H2O-CO2]− 303.1592 [M-H-C11H12O4-C2H4O2]− 301.1803 [M-H-C11H14O4-C2H4O2]− |

BGLS, RGLS, GLS |

| 52a | 11.867 | Ganoderic acid A | 515.3002 | C30H44O7 | −2.4 | 561.3062 [M-H+FA]− 497.2923 [M-H-H2O]− 453.3016 [M-H-CO2-H2O]− 435.2914 [M-H-CO2-2H2O]− 299.1645 [M-H-C11H20O4]− 285.1496 [M-H-C11H18O4-CH4]− 195.1013 [M-H-H2O-C19H30O3]− 149.0603 [M-H-C19H28O3-H2O-CO2]− |

BGLS, RGLS, GLS |

| 53a | 12.035 | Ganolucidic acid B | 501.3210 | C30H46O6 | −2.3 | 547.3264 [M-H+FA]− 483.3123 [M-H-H2O]− 439.3244 [M-H-CO2-H2O]− 287.2006 [M-H-C11H18O4]− 151.1129 [M-H-H2O-CO2-C19H28O2]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 54a | 12.144 | Ganoderenic acid D | 511.2683 | C30H40O7 | −3.6 | 511.2719 [M-H]− 493.2601 [M-H-H2O]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 467.2979 [M-H-CO2]− 449.2708 [M-H-CO2-H2O]− 437.2340 [M-H-CO2-2CH3]− 299.1641 [M-H-C11H16O4]− 247.1331 [M-H-C15H20O4]− 149.0594 [M-H-C15H20O4-C6H12O]− |

|||||||

| 55a | 12.152 | Ganoderenic acid A | 513.2847 | C30H42O7 | −2.1 | 559.2901 [M-H+FA]− 513.2890 [M-H]− 495.2760 [M-H-H2O]− 451.2892 [M-H-H2O-CO2]− 301.1804 [M-H-C11H16O4]− 285.1871 [M-H-C11H16O4-CH4]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 56 | 12.265 | Applanoxidic acid D | 527.2646 | C30H40O8 | −0.8 | 527.2646 [M-H]− 509.2557 [M-H-H2O]− 479.2087 [M-H-H2O-2CH3]− 465.2651 [M-H-H2O-CO2]− 435.2183 [M-H-H2O-CO2-2CH3]− 301.1434 [M-H-C11H14O4-CH4]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 57 | 12.308 | Lucidenic acid F | 455.2430 | C27H36O6 | −2.0 | 455.2449 [M-H]− 395.2256 [M-H-CO2-CH4]− 383.2220 [M-H-C3H4O2]− 351.2325 [M-H-C3H4O2-2CH4]− 335.1995 [M-H-C3H4O2-3CH4]− 149.0622 [M-H-C6H10O-C12H16O3]− 249.1497 [M-H-C12H14O3]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 58 | 12.366 | Ganoderic acid LM2 | 513.2845 | C30H42O7 | −2.5 | 513.2892 [M-H]− 495.2773 [M-H-H2O]− 480.2482 [M-H-H2O-CH3]− 436.2629 [M-H-H2O-CH3-CO2]− 421.2420 [M-H-H2O-CO2-2CH3]− 301.1774 [M-H-C11H16O4]− 249.1492 [M-H-C15H20O4]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 59 | 12.666 | Ganoderic acid M | 529.2801 | C30H42O8 | 2.6 | 511.2708 [M-H-H2O]− 467.2810 [M-H-H2O-CO2]− 449.2709 [M-H-CO2-2H2O]− 434.2467 [M-H-CO2-2H2O-CH3]− 301.1803 [M-H-C11H14O4-H2O]− 299.1652 [M-H-C11H16O4-H2O]− 263.1283 [M-H-C15H22O4]− |

BGLS, RGLS, GLS |

| 60a | 12.757 | Lucidenic acid A | 457.2587 | C27H38O6 | −1.9 | 503.2643 [M-H+FA]− 457.2612 [M-H]− 439.2497 [M-H-H2O]− 247.1330 [M-H-C12H18O3]− 209.1171 [M-H-C15H20O3]− 149.0603 [M-H-C17H24O5]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 61 | 12.813 | Ganolucidic acid D | 499.3055 | C30H44O6 | −2.0 | 545.3107 [M-H+FA]− 499.3078 [M-H]− 481.2959 [M-H-H2O]− 437.3059 [M-H-H2O-CO2]− 287.2020 [M-H-C11H16O4]− 285.1864 [M-H-C11H18O4]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 62 | 12.936 | Ganoderlactone B | 453.2274 | C27H34O6 | −1.9 | 499.2337 [M-H+FA]− 453.2309 [M-H]− 438.2052 [M-H-CH4]− 409.2390 [M-H-CO2]− 381.2063 [M-H-C3H4O2]− 379.1918 [M-H-C3H6O2]− 301.1799 [M-H-C8H8O3]− 299.1704 [M-H-C8H10O3]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 63a | 13.028 | Ganoderic acid B | 515.3005 | C30H44O7 | −1.8 | 561.3039 [M-H+FA]− 515.3029 [M-H]− 497.2922 [M-H-H2O]− 453.2987 [M-H-H2O-CO2]− 301.1807 [M-H-C11H18O4]− 285.1852 [M-H-C11H18O4-CH4]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 64 | 13.122 | iso-lucidenic acid E2 | 515.2642 | C29H40O8 | −1.6 | 515.3018 [M-H]− 497.2562 [M-H-H2O]− 473.2550 [M-H-C2H2O]− 455.2452 [M-H-C2H2O-H2O]− 437.2361 [M-H-C2H2O-2H2O]− 425.1971 [M-H-C2H2O-H2O-2CH3]− 407.1851 [M-H-C2H2O-H2O-2CH3-H2O]− 383.2283 [M-H-C5H8O2-2CH3]− 301.1812 [M-H-C2H4O2-C8H10O3]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 65 | 13.362 | Ganoderenic acid G | 511.2693 | C30H40O7 | −1.6 | 557.2750 [M-H+FA]− 493.2586 [M-H-H2O]− 449.2609 [M-H-CO2-H2O]− 434.2480 [M-H-CO2-H2O-CH3]− 419.2230 [M-H-CO2-H2O-2CH3]− 301.1805 [M-H-C11H14O4]− 285.1849 [M-H-C11H14O4-CH4]− |

BGLS, RGLS, GLS |

| 66 | 13.886 | Lucidenic acid F | 455.2433 | C27H36O6 | −1.3 | 455.2469 [M-H]− 437.2378 [M-H-H2O]− 381.2074 [M-H-CO2-2CH3]− 301.1815 [M-H-C8H10O3]− 299.1633 [M-H-C8H12O3]− 247.1345 [M-H-C12H16O3]− 149.0581 [M-H-C12H16O3-C6H10O]− 163.1142 [M-H-C15H20O3-CO2]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 67a | 13.976 | Ganoderic acid D | 513.2850 | C30H42O7 | −1.5 | 559.2907 [M-H+FA]− 495.2765 [M-H-H2O]− 451.2872 [M-H-H2O-CO2]− 436.2629 [M-H-H2O-CO2-CH3]− 418.2532 [M-H-2H2O-CO2-CH3]− 301.1810 [M-H-C11H16O4]− 285.1859 [M-H-C11H16O4-CH4]− 283.1708 [M-H-C11H18O4-CH4]− 247.1337 [M-H-C15H22O4]− 149.0608 [M-H-C15H22O4-C6H19O]− |

BGLS, RGLS, GLS |

| 68a | 14.307 | Ganoderenic acid F | 509.2534 | C30H38O7 | −2.1 | 509.2579 [M-H]− 491.2475 [M-H-H2O]− 465.2675 [M-H-CO2]− 461.1993 [M-H-H2O-2CH3]− 447.2560 [M-H-CO2-CH3]− 417.2074 [M-H-H2O-CO2-2CH3]− 299.1648 [M-H-C11H14O4]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 69 | 14.534 | Ganoleuconin F | 569.2750 | C32H42O9 | −1.1 | 615.2811 [M-H+FA]− 551.2643 [M-H-H2O]− 536.2404 [M-H-H2O-CH3]− 509.2544 [M-H-C2H4O2]− 491.2463 [M-H-H2O-C2H4O2]− 465.2649 [M-H-C2H4O2-CO2]− 447.2549 [M-H-H2O-C2H4O2-CO2]− |

BGLS, RGLS, GLS |

| 70 | 14.56 | Lucidenic acid D2 | 513.2487 | C29H38O8 | −1.3 | 513.2506 [M-H]− 495.2753 [M-H-H2O]− 471.2399 [M-H-C2H2O]− 441.1919 [M-H-C3H4O2]− |

BGLS, RGLS, GLS |

| 71 | 14.752 | Ganoderic acid E | 511.2694 | C30H40O7 | −1.4 | 493.2614 [M-H-H2O]− 449.2714 [M-H-H2O-CO2]− 434.2464 [M-H-H2O-CO2-CH3]− 419.2240 [M-H-H2O-CO2-2CH3]− 301.1803 [M-H-C11H14O4]− 299.1648 [M-H-C11H16O4]− 285.1490 [M-H-C11H14O4-CH4]− |

BGLS, RGLS, GLS |

| 72 | 14.899 | Ganolucidate F | 501.3210 | C30H46O6 | −2.3 | 501.3225 [M-H]− 457.3336 [M-H-CO2]− 303.1987 [M-H-C10H12O3-H2O]− 301.1797 [M-H-C10H14O3-H2O]− 287.1638 [M-H-C10H12O3-H2O-CH4]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 73 | 14.9 | Unknown | 569.2745 | C32H42O9 | −1.9 | 569.2795 [M-H]− 551.2686 [M-H-H2O]− 523.3064 [M-H-CH3CH2OH]- 509.2563 [M-H-C2H4O2]− |

RGLS |

| 74 | 14.93 | ganoderenic acid K | 571.2902 | C32H44O9 | −1.9 | 553.2833 [M-H-H2O]− 509.2928 [M-H-H2O-CO2]− 467.2829 [M-H-H2O-CO2-C2H2O]− 449.2718 [M-H-2H2O-CO2-C2H4O]− 301.1809 [M-H-C11H14O4-C2H4O2]− 299.1646 [M-H-C11H16O4-C2H4O2]− 263.1278 [M-H-C11H16O4-C2H4O2-2H2O]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 75 | 15.072 | 12β-acetoxy-7β-hydroxy-3,11,15,23-tetraoxo-5α-lanosta-8,20(22)-dien-26-oic acid | 569.2763 | C32H42O9 | 1.2 | 1047.5907 [2M-H]− 569.2277 [M-H]− 551.2683 [M-H-H2O]− 509.2571 [M-H-C2H4O2]− 465.2650 [M-H-C2H4O2-CO2]− 447.2547 [M-H-H2O-C2H4O2-CO2]− 429.2469 [M-H-2H2O-C2H4O2-CO2]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 76 | 15.197 | Unknown | 489.2849 | C28H42O7 | −1.8 | 443.2807 [M-H-CH3CH2OH]− 399.2907 [M-H-CH3CH2OH-CO2]− 381.2789 [M-H-CH3CH2OH-CO2-H2O]− 287.1999 [M-H-CH3CH2OH-CO2-H2O-C7H12O]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 77 | 15.198 | Ganoderenic acid H | 511.2690 | C30H40O7 | −2.2 | 511.2708 [M-H]− 493.2615 [M-H-H2O]− 449.2705 [M-H-H2O-CO2]− 434.2469 [M-H-H2O-CO2-CH3]− 149.0603 [M-H-H2O-CO2-C19H24O3]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 78 | 15.396 | Ganoderic acid GS | 525.2483 | C30H38O8 | −2.1 | 525.2579 [M-H]− 507.2425 [M-H-H2O]− 492.2190 [M-H-H2O-CH3]− 477.1948 [M-H-H2O-2CH3]− 463.2520 [M-H-H2O-CO2]− 448.2253 [M-H-H2O-CO2-CH3]− 433.2068 [M-H-H2O-CO2-2CH3]− 315.1605 [M-H-C11H14O4]− 287.1618 [M-H-C11H12O4-2CH3]− |

BGLS, RGLS, GLS |

| 79 | 15.666 | 3β-hydroxyganodernoid D | 511.2693 | C30H40O7 | −2.2 | 499.3063 [M-H]− 481.2996 [M-H-H2O]− 437.3062 [M-H-H2O-CO2]− 399.2520 [M-H-C6H12O]− 287.2068 [M-H-C11H16O3-CH3]− 235.1702 [M-H-C15H22O3-CH3]− 99.0448 [M-H-C24H32O5]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 80 | 15.617 | Ganolucidic acid A | 499.3054 | C30H44O6 | −2.2 | 545.3109 [M-H+FA]− 481.2974 [M-H-H2O]− 437.3081 [M-H-CO2-H2O]− 287.1999 [M-H-C11H14O3]− 285.1858 [M-H-C11H16O3]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 81 | 15.619 | Ganoderic acid R or ganoderic acid Me | 545.3107 | C31H46O8 | −2.4 | 545.3108 [M-H]− 511.2691 [M-H-CO2]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 82 | 15.666 | Ganodernoid D | 567.2595 | C32H40O9 | −0.8 | 567.2646 [M-H]− 549.2541 [M-H-H2O]− 507.2429 [M-H-C2H2O]− 477.1957 [M-H-C2H2O-2CH3]− 463.2514 [M-H-C2H2O-CO2]− 433.2040 [M-H-C2H2O-CO2-2CH3]− 315.1602 [M-H-C11H14O4-C2H2O]− 300.1366 [M-H-C11H14O4-C2H2O-CH3]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 83 | 16.095 | Ganoderic acid F | 569.2753 | C32H42O9 | −0.5 | 615.2807 [M-H+FA]− 551.2645 [M-H-H2O]− 509.2561 [M-H-C2H4O2]− 479.2089 [M-H-C2H4O2-2CH3]− 465.2658 [M-H-C2H4O2-CO2]− 447.2544 [M-H-H2O-C2H4O2-CO2]− 435.2186 [M-H-C2H4O2-CO2-2CH3]− |

BGLS, RGLS, GLS |

| 84 | 16.419 | Ganoderic acid β | 499.3055 | C30H44O6 | −2.0 | 499.3101 [M-H]− 455.3188 [M-H-CO2]− 425.2707 [M-H-CO2-2CH3]− 287.2024 [M-H-C11H16O3-CH3]− 285.1900 [M-H-C11H18O3-CH3]− 249.1466 [M-H-C15H22O3]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 85 | 16.499 | Ganoderic acid AM1 | 513.2850 | C30H42O7 | −1.5 | 559.2908 [M-H+FA]− 495.2761 [M-H-H2O]− 451.2851 [M-H-H2O-CO2]− 421.2374 [M-H-H2O-CO2-2CH3]− 399.2550 [M-H-3H2O-CO2-CH4]− 301.1794 [M-H-C11H16O4]− 285.1496 [M-H-C11H16O4-CH4]− |

BGLS, RGLS, GLS |

| 86 | 16.845 | Ganohainanic acid C | 499.3054 | C30H44O6 | −2.2 | 499.3063 [M-H]− 481.2996 [M-H-H2O]− 437.3062 [M-H-H2O-CO2]− 399.2520 [M-H-C6H12O]− 287.2068 [M-H-C11H16O3-CH3]− 235.1702 [M-H-C15H22O3-CH3]− 99.0448 [M-H-C24H32O5]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 87 | 17.456 | Unknown | 501.3208 | C30H46O6 | −2.7 | 547.3265 [M-H+FA]− 501.3250 [M-H]− 303.2011 [M-H-CO2-C9H12O-H2O]− 287.2019 [M-H-C11H18O4]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 88 | 18.435 | Ganorbiformin A | 543.3318 | C32H48O7 | −1.7 | 543.3336 [M-H]− 501.3252 [M-H-C2H2O]− 497.2946 [M-H-CH2O2]− 483.3175 [M-H-C2H4O2]− 457.3330 [M-H-C2H2O-CO2]− 439.3218 [M-H-C2H4O2-CO2]− 301.1783 [M-H-C12H18O4-H2O]− 287.1630 [M-H-C12H16O4-H2O-CH3]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 89 | 18.514 | Applanoxidic acid H | 529.2798 | C30H42O8 | −1.7 | 511.2716 [M-H-H2O]− 481.2229 [M-H-H2O-2CH3]− 467.2844 [M-H-H2O-CO2]− 437.2354 [M-H-H2O-CO2-2CH3]− 345.1632 [M-H-C10H16O3]− 303.1682 [M-H-H-C11H14O5]− |

RGLS |

| 90 | 18.62 | iso-ganodernoid D | 567.2594 | C32H40O9 | −1.0 | 567.2621 [M-H]− 549.2511 [M-H-H2O]− 525.2525 [M-H-C2H2O]− 507.2407 [M-H-C2H2O2-H2O]− 495.2039 [M-H-C2H2O-2CH3]− 492.2165 [M-H-C2H4O2-CH3]− 477.1937 [M-H-H2O-CO2-2CH3]− 463.2489 [M-H-C2H4O2-CO2]− |

RGLS |

| 91 | 18.934 | Ganoderic acid J | 513.2851 | C30H42O7 | −1.3 | 513.2865 [M-H]− 495.2778 [M-H-H2O]− 451.2870 [M-H-H2O-CO2]− 433.2751 [M-H-2H2O-CO2]− 421.2380 [M-H-H2O-CO2-2CH3]− 301.1808 [M-H-C11H16O4]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 92 | 19.274 | Ganoderic acid GS-2 | 499.3054 | C30H44O6 | −2.2 | 499.3066 [M-H]− 455.3153 [M-H-CO2]− 437.3089 [M-H-CO2-H2O]− 357.2432 [M-H-C8H14O2]− 301.1801 [M-H-C11H18O3]− 285.1481 [M-H-C11H18O3-CH3]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 93 | 20.901 | Ganohainanic acid C | 499.3052 | C30H44O6 | −2.6 | 499.3104 [M-H]− 481.2896 [M-H-H2O]− 437.3014 [M-H-H2O-CO2]− 301.1772 [M-H-C11H18O3]− 287.1916 [M-H-C11H16O3-CH3]− 285.1847 [M-H-C11H18O3-CH3]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 94 | 20.947 | Unknown | 543.3308 | C32H48O7 | −3.5 | 497.2937 [M-H-CH2O2]− 479.2817 [M-H-CH2O2-H2O]− 435.2911 [M-H-CH2O2-H2O-CO2]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 95 | 21.202 | Ganoderic acid K | 573.3069 | C32H46O9 | 0.0 | 555.2992 [M-H-H2O]− 511.3804 [M-H-CO2-H2O]− 493.2991 [M-H-CO2-2H2O]− 343.1910 [M-H-C2H4O2-C9H14O3]− 249.1474 [M-H-C11H14O4-C2H4O2-3H2O]− |

RGLS |

| 96 | 22.699 | 11-ketodiacetyltangulinsaeure | 615.3174 | C34H48O10 | −0.1 | 615.3174 [M-H]− 597.3121 [M-H-H2O]− 555.2924 [M-H-CH3COOH]− 553.3118 [M-H-H2O-CO2]− 538.3100 [M-H-H2O-CO2-CH3]− 511.3096 [M-H-H2O-CO2-C2H2O]− 493.3029 [M-H-2H2O-CO2-C2H2O]− 478.2686 [M-H-2H2O-CO2-C2H2O-CH3]− 344.1960 [M-H-2H2O-CO2-C2H2O-CH3-C10H14]− 307.1508 [M-H-2H2O-CO2-C2H2O-C14H18]− |

RGLS |

| 97 | 22.879 | iso-applanoxidic acid C | 525.2484 | C30H38O8 | −1.9 | 525.2552 [M-H]− 507.2400 [M-H-H2O]− 495.2078 [M-H-2CH3]− 477.1963 [M-H-H2O-2CH3]− 463.2500 [M-H-H2O-CO2]− 328.1327 [M-H-C10H13O4]− |

RGLS |

| 98 | 23.227 | Ganolucidic acid E | 483.3106 | C30H44O5 | −2.1 | 529.3160 [M-H+FA]− 439.3231 [M-H-CO2]− 421.3100 [M-H-CO2-H2O]− 287.2013 [M-H-C11H16O3]− 285.1849 [M-H-C11H18O3]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 99 | 23.255 | Applanoxidic acid A or applanoxidic acid E | 511.2684 | C30H40O7 | 8.1 | 493.2616 [M-H-H2O]− 467.2727 [M-H-CO2]− 449.2715 [M-H-CO2-H2O]− 437.2241 [M-H-C3H6O2]− 431.2602 [M-H-CO2-2H2O]− 419.2223 [M-H-C3H6O2-H2O]− 405.2786 [M-H-C4H8O2-H2O]− 301.1820 [M-H-C11H14O4]− 299.1609 [M-H-C11H16O4]− 285.1435 [M-H-C11H14O4-CH4]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 100 | 24.006 | 11β-hydroxy-3,7-dioxo-5α-lanosta-8,24(E)-dien-26-oic acid | 483.3104 | C30H44O5 | −2.5 | 483.3124 [M-H]− 385.2429 [M-H-C6H10O]− 345.2072 [M-H-C9H14O]− 271.1679 [M-H-C9H14O-2CH3-CO2]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 101 | 25.381 | Ganoderic acid V | 527.3370 | C32H48O6 | −1.5 | 527.3405 [M-H]− 485.3237 [M-H-C2H4O]− 441.3395 [M-H-C2H4O-CO2]− 289.2149 [M-H-C13H18O4]− 195.1011 [M-H-C19H28O2-C2H4O]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 102 | 29.09 | Unknown | 571.3274 | C33H48O8 | −0.4 | 525.3240 [M-H-C2H2O]− 465.3041 [M-H-H2O-C2H4O2-CH2O]− 315.0470 [M-H-C11H16O4-C2H4O]− 255.2289 [M-H-C3H6O2-C4H8O2-C8H10O3]− 241.0100 [M-H-C3H6O2-CH4-C4H6O2-C8H10O3]− 153.0000 [M-H-C22H26O8]- 99.0450 [M-H-C26H32O8]- |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 103 | 29.37 | Unknown | 525.3213 | C32H46O6 | −1.6 | 571.3267 [M-H+FA]− 483.3126 [M-H-C2H2O]− 439.3239 [M-H-C2H2O-CO2]− 421.3092 [M-H-C2H2O-CO2-H2O]− 287.1987 [M-H-C12H16O4-CH3]− 285.1877 [M-H-C12H18O4-CH3]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 104 | 30.354 | Ganodernoid G | 571.2886 | C32H44O9 | −4.7 | 525.3254 [M-H-C2H2O]− 465.3020 [M-H-C2H4O2-CO2]− 315.0486 [M-H-C11H16O4-C2H4O]− 255.2327 [M-H-C11H12O4-C2H4O2-2CH4-H2O]− 241.0113 [M-H-C11H12O4-C2H4O2-2CH4-2H2O]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 105a | 32.552 | Ganoderic acid DM | 467.3153 | C30H44O4 | −3.0 | 467.3176 [M-H]− | BGLS, RGLS |

| 106 | 34.013 | Ganoderic acid TR | 467.3159 | C30H44O4 | −1.7 | 467.3178 [M-H]− 449.3060 [M-H-H2O]− 405.3153 [M-H-H2O-CO2]− 389.2859 [M-H-H2O-CO2-CH3]− 295.2066 [M-H-CO2-2CH3-C6H10O]− |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 107 | 36.159 | Unknown | 475.3058 | C28H44O6 | −1.5 | 475.3071 [M-H]- 457.2947 [M-H-H2O]- 431.3174 [M-H-CO2]- 413.3052 [M-H-CO2-H2O]- |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 108 | 38.022 | Unknown | 475.3056 | C28H44O6 | −1.9 | 475.3081 [M-H]- 431.3163 [M-H-CO2]- 413.3079 [M-H-CO2-H2O]- |

BGLS, RGLS |

| 109 | 38.176 | Linoleic acid | 279.2330 | C18H32O2 | −1.6 | 279.2337 [M-H]− | BGLS, RGLS, GLS |

Identified with reference compounds.

GLS, Ganoderma lucidum spore; BGLS, sporoderm-broken Ganoderma lucidum spore; RGLS, sporoderm-removed Ganoderma lucidum spore.

Figure 3.

A representative MS/MS similarity network of the sporoderm-removed Ganoderma lucidum spore. Orange nodes represent reference triterpenoids (i.e., ganoderic acid D, H, and F), while green nodes represent identified triterpenoids.

Zebrafish Assays to Assess Immunomodulatory Activities

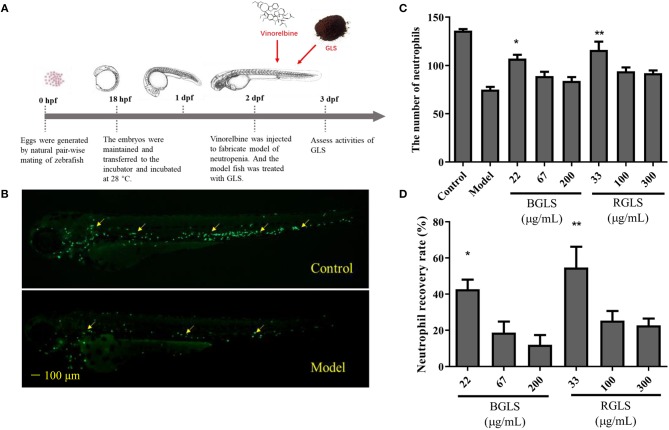

The large difference of chemical profiles of BGLS and RGLS indicated their bioactivities might vary. Due to its convenience and optical accessibility, the zebrafish (D. rerio) has been widely adopted as a model for understanding the mechanisms of development and recently, there has been increasing use of the this organism in varied fields including immunology (Novoa and Figueras, 2012). Therefore, as GLS is considered as a potential immunotherapy agent (Cao et al., 2018), the zebrafish models of neutropenia and macrophage deficiency were employed to evaluate the immunomodulatory activities in terms of neutropenia recovery, macrophage formation, and macrophage phagocytosis. Vinorelbine was intravenously injected at 1 and 0.25 ng per larva to generate the neutropenia and macrophage deficiency models, respectively (Figures 4A, 5A). As shown in Figure 4B, the fluorescence intensity of the model group decreased significantly compared with the control, indicating the model was successfully established. After exposing to different concentrations of BGLS and RGLS for 24 h, the number of neutrophils in the larvae recovered with different degrees. BGLS of 22 μg/mL and RGLS of 33 μg/mL significantly improved the neutrophils compared with the model (P < 0.05 or 0.01), while RGLS exhibited more potent effects than BGLS (Figures 4C,D).

Figure 4.

Assessment of immunoactivity of Ganoderma lucidum spores on zebrafish models of neutropenia. (A) Scheme of zebrafish husbandry and treatment. (B) Representative fluorescent images of Tg (mpx:GFP) transgenic larvae of control and model groups. (C) Neutrophils count in zebrafish of different groups. (D) Neutrophil recovery rate (%) of different groups. BGLS, sporoderm-broken Ganoderma lucidum spores; RGLS, sporoderm-removed Ganoderma lucidum spores. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 10. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. Model.

Figure 5.

Assessment of immunoactivity of Ganoderma lucidum spores on zebrafish models of macrophage deficiency and macrophage phagocytosis. (A) Overview of zebrafish development and experimental protocol. (B) Represent images of macrophages in healthy fish and zebrafish model of macrophage deficiency. (C) Macrophages count in zebrafish of different groups. (D) The number of macrophages that phagocytize active carbon nanoparticles of different groups. (E) Macrophage formation efficiency (%) of different groups. (F) Macrophage phagocytosis efficiency (%) of different groups. BGLS, sporoderm-broken Ganoderma lucidum spores; RGLS, sporoderm-removed Ganoderma lucidum spores. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 10. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. Model.

In the macrophage deficiency model created by vinorelbine (Figure 5B), however, only RGLS of higher concentrations (i.e., 333 and 1,000 μg/mL) could significantly promote the formation of macrophages compared with the model (P < 0.01), while BGLS showed very weak effects (Figures 5C,D). Likewise, in the macrophage phagocytosis model, RGLS of 333 and 1,000 μg/mL significantly increased the number of macrophages that phagocytized ACNP, while BGLS of tested concentrations exhibited slight improvement (Figures 5E,F).

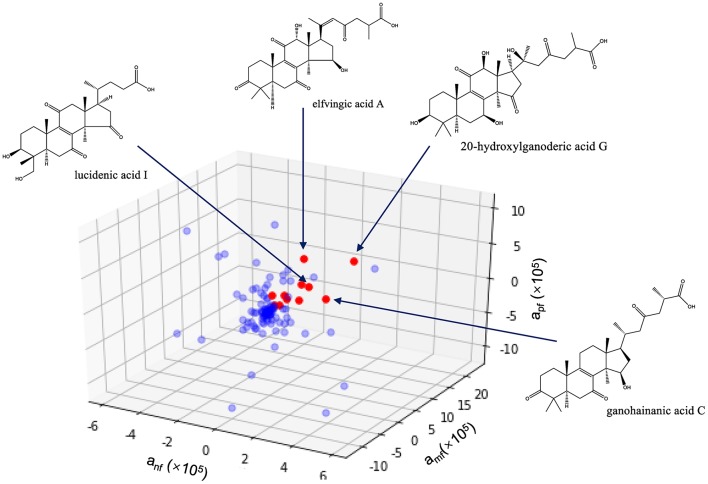

Screening Active Compounds by PLSR-Based Activity Ranking

The above results suggested the immunomodulatory activity of GLS was positively correlated with the content of triterpenoids. However, more than 100 triterpenoids were detected in the GLS, and their contents varied considerably, making it difficult to assign the activity to a single molecule. In addition, as most of these triterpenoids were not commercially available, it would be rather labor-intensive and costly to purify and test the compounds individually. To rapidly screen potential active compounds, we employed the partial least squares regression (PLSR) algorithm to find the correlation between the peak area information (X variables) and the activity (Y variable, i.e., neutrophil recovery rate, macrophage formation efficiency or macrophage phagocytosis efficiency). The activity index was proposed to evaluate the contribution of each constituent to the activities, which was calculated using the following formula:

where Y was the activity of the tested sample; ai was the activity index of constituent i; xi was the peak area of constituent i in the tested sample; Ci was the relative concentration of the tested sample, which was defined as ci/cmax, where ci was the concentration of the tested sample and cmax was the max concentration in each group.

The PLSR model was created according to PLS-W2A (Wegelin, 2000). The dataset obtained was transferred to the center of the multidimensional coordinate system to identify potential active compounds that had high activity index in all the three bioassays. All programs were operated by Spyder with Python 3.6 (Anaconda, Inc., Austin, Texas, USA) software.

As shown in Figure 6, 11 compounds, namely 20-hydroxylganoderic acid G, elfvingic acid A, elfvingic C, lucidenic acid I, ganohainanic acid C, ganoderic acid β, methyl lucidenate E2, dehydrolucidenic acid N, applanoxidic acid G, ganolucidic acid D and ganoderenic acid H were identified as potential immunoactive compounds that ranked high in neutropenia recovery, macrophage formation, and macrophage phagocytosis. However, these candidates needed meticulous validation in vivo and in vitro to confirm their pharmacological effects.

Figure 6.

Identification of immunoactive compounds of Ganoderma lucidum spore by activity index. anf, amf, apf are the activity indices of the compound, representing its effects on neutrophil recovery, macrophage formation and macrophages phagocytosis, respectively.

Discussion

It has been reported that G. lucidum contains over 400 bioactive compounds, including triterpenoids, polysaccharides, nucleotides, sterols, steroids, fatty acids and proteins/peptides, which have various medicinal effects. In the present study, we identified chemical constitutes of GLS by LC-MS and the main constitutes of GLS were identified as triterpenoids. We further employed zebrafish as the animal model to investigate the immunomodulatory activities of GLS, due to its advantages in immune-related research, which included: (1) having complete (innate and adaptative) immune systems, and possessing neutrophils and macrophages in adults and larvae; (2) having a relatively rapid life cycle and was easy to maintain; (3) quickly producing large numbers of offspring that could be assayed in multi-well plates and treated with different chemicals. Finally, activity index was proposed to evaluate the contribution of each constituent to the activity to screen potential immunoactive ones.

In a previous study, Ahmadi and Riazipour revealed that G. lucidum could improve macrophage function through cytokine and NO release (Ahmadi and Riazipour, 2007). Besides, several pharmacological studies have shown that G. lucidum can play an antitumor role through the regulation of the immune system (Boh et al., 2007). A finding suggested that the triterpenes of G. lucidum inhibited anti-lung cancer in vitro and in vivo via enhancement of immunomodulation and induction of cell apoptosis (Liang et al., 2013). Therefore, it can be predicted that GLS may affect the formation and phagocytic function of macrophages to exert the immunomodulatory effect.

Among the compounds identified in G. lucidum, triterpenoids are most widely investigated. Besides the anticancer activities which have been reported by many studies, triterpenoids also showed good immunomodulatory effects. It has been reported that the triterpenoids extract from G. lucidum have anti-inflammatory and anti-proliferative effects, which are mediated through the inhibition of NF-κB and AP-1 signaling pathways in macrophages (Dudhgaonkar et al., 2009). As a major triterpene of GL and GLS, previous studies suggested that Ganoderic acid A played a role in immunomodulation through inhibiting the release of proinflammatory mediators like IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α (Chi et al., 2018). A study also suggested that Ganoderic acid A-treatment not only enhanced cell-mediated immune responses, but also potentiated antitumor immune responses by activating IFN-γ producing CD8+ T cells (Radwan et al., 2015). Liu et al. found that ganoderic acid C1 had an effect on immune system and significantly suppressed murine macrophage TNF-α production, which was associated with suppression of NF-κB (Liu et al., 2015). These studies gave possible direction of our further mechanism study.

Conclusion

This work demonstrates the feasibility of mass spectrometry molecular networking coupled with zebrafish-based bioassays and chemometrics for active constituent identification of complex herbal medicine. An efficient MS data processing method integrating molecular networking and targeted LC-MS analysis was established to comprehensively profile GLS, leading to the characterization of 109 constituents. Immunomodulatory activities of different GLS samples were evaluated by zebrafish models of neutrophil or macrophage deficiency, in which RGLS showed better therapeutic effects than BGLS. Moreover, a three-dimensional activity index approach based on PLSR was developed to identify active constituents in GLS that were effective on all the three bioassays, which included 20-hydroxylganoderic acid G, elfvingic acid A, elfvingic C, and etc. Future works are needed to validate the pharmacological effects of these compounds using purified substances on various in vivo assays. Also possible for further work is employing ions in the molecular network rather than identified peaks for correlation analysis, to explore the potential relationship between bioactivities and certain ions/structures.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The animal study was reviewed and approved by the International Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC).

Author Contributions

ZL, JX, and YW designed the research. ZL, YS, and XZ performed the experimental work and analyzed the data. ZL, JX, and HW prepared the GLP extracts. ZL, YS, LZ, and YW participated in the preparation of manuscript. All authors proofread the paper and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 81803714, 81822047), the National Major Science and Technology Project of China (Grant No. 2017ZX09301012), the Science Technology Department of Zhejiang Province (2016C33060), and the Key R&D Foundation of Zhejiang Province (2019C02100).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphar.2020.00287/full#supplementary-material

References

- Ahmad M. F. (2018). Ganoderma lucidum: persuasive biologically active constituents and their health endorsement. Biomed. Pharmacother. 107, 507–519. 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.08.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadi K., Riazipour M. (2007). Effect of Ganoderma lucidum on cytokine release by peritoneal macrophages. Iran. J. Immunol. 4, 220–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allard P.-M., Peresse T., Bisson J., Gindro K., Marcourt L., Van Cuong P., et al. (2016). Integration of molecular networking and in-silico MS/MS fragmentation for natural products dereplication. Anal. Chem. 88, 3317–3323. 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b04804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop K. S., Kao C. H. J., Xu Y., Glucina M. P., Paterson R. R. M., Ferguson L. R. (2015). From 2000 years of Ganoderma lucidum to recent developments in nutraceuticals. Phytochemistry 114, 56–65. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2015.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boh B., Berovic M., Zhang J., Lin Z. B. (2007). Ganoderma lucidum and its pharmaceutically active compounds. Biotechnol. Annu. Rev. 13, 265–301. 10.1016/S1387-2656(07)13010-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y., Xu X., Liu S., Huang L., Gu J. (2018). Ganoderma: a cancer immunotherapy review. Front. Pharmacol. 9:1217. 10.3389/fphar.2018.01217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang J. B., Lane M. E., Yang M., Heinrich M. (2018). Disentangling the complexity of a hexa-herbal Chinese medicine used for inflammatory skin conditions-predicting the active components by combining LC-MS-based metabolite profiles and in vitro pharmacology. Front. Pharmacol 9:1091. 10.3389/fphar.2018.01091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G., Huang B. X., Guo M. (2018). Current advances in screening for bioactive components from medicinal plants by affinity ultrafiltration mass spectrometry. Phytochem. Analysis 29, 375–386. 10.1002/pca.2769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Liu X., Sheng D., Huang D., Li W., Wang X. (2012). Distinction of broken cellular wall Ganoderma lucidum spores and G. lucidum spores using FTIR microspectroscopy. Spectrochim. Acta A 97, 667–672. 10.1016/j.saa.2012.07.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi B., Wang S., Bi S., Qin W., Wu D., Luo Z., et al. (2018). Effects of ganoderic acid A on lipopolysaccharide-induced proinflammatory cytokine release from primary mouse microglia cultures. Exp. Ther. Med. 15, 847–853. 10.3892/etm.2017.5472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudhgaonkar S., Thyagarajan A., Sliva D. (2009). Suppression of the inflammatory response by triterpenes isolated from the mushroom Ganoderma lucidum. Int. Immunopharmacol. 9, 1272–1280. 10.1016/j.intimp.2009.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu H., Jia T., Zhang Y., Fumimaru M., Eri O., Li H., et al. (2012). The role of three kinds of ganoderma lucidum powder on regulation of immune functions of immunosuppressive mice model. Chinese J. Immunol. 28, 712–716. 10.3969/j.issn.1000-484X.2012.08.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao G., Bao H., Bau T. (2013). Anti-tumor activity of the nano-scale fruiting body powder and the wall-broken spore powder of Ganoderma lucidum in vitro. Mygosystema 32, 114–127. 10.13346/j.mycosystema.2013.01.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ge Y. W., Zhu S., Yoshimatsu K., Komatsu K. (2017). MS/MS similarity networking accelerated target profiling of triterpene saponins in Eleutherococcus senticosus leaves. Food Chem. 227, 444–452. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.01.119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guthals A., Watrous J. D., Dorrestein P. C., Bandeira N. (2012). The spectral networks paradigm in high throughput mass spectrometry. Mol. Biosyst. 8, 2535–2544. 10.1039/c2mb25085c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofstadler S. A., Sannes-Lowery K. A. (2006). Applications of ESI-MS in drug discovery: interrogation of noncovalent complexes. Nat. Rev. Drug Disco. 5, 585–595. 10.1038/nrd2083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu K.-D., Cheng K.-C. (2018). From nutraceutical to clinical trial: frontiers in Ganoderma development. Appl. Microbiol. Biot. 102, 9037–9051. 10.1007/s00253-018-9326-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessner D., Chambers M., Burke R., Agusand D., Mallick P. (2008). ProteoWizard: open source software for rapid proteomics tools development. Bioinformatics 24, 2534–2536. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Guo X., Cao Z., Liu X., Liao X., Huang C., et al. (2018). New MS network analysis pattern for the rapid identification of constituents from traditional Chinese medicine prescription Lishukang capsules in vitro and in vivo based on UHPLC/Q-TOF-MS. Talanta 189, 606–621. 10.1016/j.talanta.2018.07.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Liu T., Liao J., Ai N., Fan X., Cheng Y. (2017). Deciphering chemical interactions between glycyrrhizae radix and coptidis rhizoma by liquid chromatography with transformed multiple reaction monitoring mass spectrometry. J. Sep. Sci. 40, 1254–1265. 10.1002/jssc.201601054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Wang Y., Cheng Y. (2019). Mass spectrometry-sensitive probes coupled with direct analysis in real time for simultaneous sensing of chemical and biological properties of botanical drugs. Anal. Chem. 91, 9001–9009. 10.1021/acs.analchem.9b01251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Xiao S., Ai N., Luo K., Fan X., Cheng Y. (2015). Derivative multiple reaction monitoring and single herb calibration approach for multiple components quantification of traditional Chinese medicine analogous formulae. J. Chromatogr. A 1376, 126–142. 10.1016/j.chroma.2014.12.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang F., Ling Y., Meng D., Yan C., Ming-Hua Z., Jun-Fei G., et al. (2013). Anti-lung cancer activity through enhancement of immunomodulation and induction of cell apoptosis of total triterpenes extracted from Ganoderma luncidum (Leyss. ex Fr.) Karst. Molecules 18, 9966–9981. 10.3390/molecules18089966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Z. B., Wang P. Y. (2006). The pharmacological study of Ganoderma spores and their active components. J. Peking Univ. Health Sci. 38, 541–547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C., Yang N., Song Y., Wang L., Zi J., Zhang S., et al. (2015). Ganoderic acid C1 isolated from the anti-asthma formula, ASHMI™ suppresses TNF-α production by mouse macrophages and peripheral blood mononuclear cells from asthma patients. Int. Immunopharmacol. 27, 224–231. 10.1016/j.intimp.2015.05.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Chen X., Zhao X., Zhao B., Qian K., Shi Y., et al. (2018). Screening and identification of cardioprotective compounds from wenxin keli by activity index approach and in vivo zebrafish model. Front. Pharmacol. 9:1288. 10.3389/fphar.2018.01288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Wang J. H., Yuan J. P. (2005). Pharmacological and anti-tumor activities of Ganoderma spores processed by top-down approaches. J. Nanosci. Nanotec. 5, 2001–2013. 10.1166/jnn.2005.448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Liu Y., Qiu F., Di X. (2011). Sensitive and selective liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry method for the determination of five ganoderic acids in Ganoderma lucidum and its related species. J. Pharmaceut. Biomed. 54, 717–721. 10.1016/j.jpba.2010.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayak R. N., Dixitraj P. T., Nayak A., Bhat K. (2015). Evaluation of anti-microbial activity of spore powder of Ganoderma lucidum on clinical isolates of Prevotella intermedia: a pilot study. Contemp. Clin. Dent. 6, S248–252. 10.4103/0976-237X.166834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman D. J., Cragg G. M. (2016). Natural products as sources of new drugs from 1981 to 2014. J. Nat. Prod. 79, 629–661. 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.5b01055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novoa B., Figueras A. (2012). Zebrafish: model for the study of inflammation and the innate immune response to infectious diseases. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 946, 253–275. 10.1007/978-1-4614-0106-3_15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacholarz K. J., Garlish R. A., Taylor R. J., Barran P. E. (2012). Mass spectrometry based tools to investigate protein-ligand interactions for drug discovery. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 4335–4355. 10.1039/c2cs35035a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiang L., Ting-Hao K., Chongde S., Kunsong C., Cheng-Chih H., Xian L. (2019). Comprehensive structural characterization of phenolics in litchi pulp using tandem mass spectral molecular networking. Food Chem. 282, 9–17. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn R. A., Nothias L. F., Vining O., Meehan M., Esquenazi E., Dorrestein P. C. (2017). Molecular networking as a drug discovery, drug metabolism, and precision medicine strategy. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 38, 143–154. 10.1016/j.tips.2016.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radwan F. F. Y., Hossain A., God J. M., Leaphart N., Elvington M., Nagarkatti M., et al. (2015). Reduction of myeloid-derived suppressor cells and lymphoma growth by a natural triterpenoid. J. Cell. Biochem. 116, 102–114. 10.1002/jcb.24946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell R., Paterson M. (2006). Ganoderma – a therapeutic fungal biofactory. Phytochemistry 67, 1985–2001. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2006.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soccol C. R., Bissoqui L. Y., Rodrigues C., Rubel R., Sella S., Leifa F., et al. (2016). Pharmacological properties of biocompounds from spores of the lingzhi or reishi medicinal mushroom Ganoderma lucidum (Agaricomycetes): a review. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 18, 757–767. 10.1615/IntJMedMushrooms.v18.i9.10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G. H., Wang L. H., Wang C., Qin L. H. (2018). Spore powder of Ganoderma lucidum for the treatment of alzheimer disease: a pilot study. Medicine 97:e0636. 10.1097/MD.0000000000010636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M., Carver J. J., Phelan V. V., Sanchez L. M., Garg N., Peng Y., et al. (2016a). Sharing and community curation of mass spectrometry data with global natural products social molecular networking. Nat. Biotechnol. 34, 828–837. 10.1038/nbt.3597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Zhang A., Sun H., Han Y., Yan G. (2016b). Discovery and development of innovative drug from traditional medicine by integrated chinmedomics strategies in the post-genomic era. Trac-Trends Anal. Chem. 76, 86–94. 10.1016/j.trac.2015.11.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.-J., Ren J.-L., Zhang A.-H., Sun H., Yan G.-L., Han Y., et al. (2019). Novel applications of mass spectrometry-based metabolomics in herbal medicines and its active ingredients: current evidence. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 38, 380–402. 10.1002/mas.21589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watrous J., Roach P., Alexandrov T., Heath B. S., Yang J. Y., Kersten R. D., et al. (2012). Mass spectral molecular networking of living microbial colonies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, E1743–E1752. 10.1073/pnas.1203689109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegelin J. A. (2000). A survey of Partial Least Squares (PLS) Methods, With Emphasis on the Two-Block Case. Seattle, WA: University of Washington, Tech. Rep. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao S., Luo K. D., Wen X. X., Fan X. H., Cheng Y. Y. (2014). A pre-classification strategy for identification of compounds in traditional Chinese medicine analogous formulas by high-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. J. Pharmaceut. Biomed. 92, 82–89. 10.1016/j.jpba.2013.12.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J., Liu Z., Wang Y., Zhu H., Zheng H., Li M., et al. (2014). Determination of inorganic elements in Ganoderma lucidum spore powder with different treatments of wall-broken methods by microwave digestion-ICP-MS. Chin. J. Mod. Appl. Pharm. 31, 813–817. [Google Scholar]

- Yan Z., Xia B., Qiu M. H., Sheng D. L., Xu H. X. (2013). Fast analysis of triterpenoids in Ganoderma lucidum spores by ultra-performance liquid chromatography coupled with triple quadrupole mass spectrometry. Biomed. Chromatogr. 27, 1560–1567. 10.1002/bmc.2960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang D., Limin H., Yuqi L., Liming Z., Jike L., Qingwu H., et al. (2017). Effect of different cell wall disruption methods on in vitro antioxidant activity of crude polysaccharides Ganoderma lucidum spores. Food Sci. Chin. 38, 101–106. 10.7506/spkx1002-6630-201717017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J. Y., Sanchez L. M., Rath C. M., Liu X., Boudreau P. D., Bruns N., et al. (2013). Molecular networking as a dereplication strategy. J. Nat. Prod. 76, 1686–1699. 10.1021/np400413s [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z., Zhang Y., Sun L., Wang Y., Gao X., Cheng Y. (2012). An ultrafiltration high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with diode array detector and mass spectrometry approach for screening and characterising tyrosinase inhibitors from mulberry leaves. Analy. Chim. Acta 719, 87–95. 10.1016/j.aca.2012.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Y., Wang Y., Sun G., Wang Y., Cao L., Shen Y., et al. (2018). Archaeological evidence suggests earlier use of Ganoderma in Neolithic China. Chinese Sci. Bull. 63, 1180–1188. 10.1360/N972018-00188 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H., Zhang Q., Zhao L., Huang X., Wang J., Kang X. (2012). Spore powder of Ganoderma lucidum improves cancer-related fatigue in breast cancer patients undergoing endocrine therapy: a pilot clinical trial. Evid.-Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2012:809614. 10.1155/2012/809614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L.-W., Cao Y., Wu S.-H., Vlasak J., Li D.-W., Li M.-J., et al. (2015). Global diversity of the Ganoderma lucidum complex (Ganodermataceae, Polyporales) inferred from morphology and multilocus phylogeny. Phytochemistry 114, 7–15. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2014.09.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.