Key Points

Question

What are the associations between daily step counts and step intensity with mortality among US adults?

Findings

In this observational study that included 4840 participants, a greater number of steps per day was significantly associated with lower all-cause mortality (adjusted hazard ratio for 8000 steps/d vs 4000 steps/d, 0.49). There was no significant association between step intensity and all-cause mortality after adjusting for the total number of steps per day.

Meaning

Greater numbers of steps per day were associated with lower risk of all-cause mortality.

Abstract

Importance

It is unclear whether the number of steps per day and the intensity of stepping are associated with lower mortality.

Objective

Describe the dose-response relationship between step count and intensity and mortality.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Representative sample of US adults aged at least 40 years in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey who wore an accelerometer for up to 7 days ( from 2003-2006). Mortality was ascertained through December 2015.

Exposures

Accelerometer-measured number of steps per day and 3 step intensity measures (extended bout cadence, peak 30-minute cadence, and peak 1-minute cadence [steps/min]). Accelerometer data were based on measurements obtained during a 7-day period at baseline.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was all-cause mortality. Secondary outcomes were cardiovascular disease (CVD) and cancer mortality. Hazard ratios (HRs), mortality rates, and 95% CIs were estimated using cubic splines and quartile classifications adjusting for age; sex; race/ethnicity; education; diet; smoking status; body mass index; self-reported health; mobility limitations; and diagnoses of diabetes, stroke, heart disease, heart failure, cancer, chronic bronchitis, and emphysema.

Results

A total of 4840 participants (mean age, 56.8 years; 2435 [54%] women; 1732 [36%] individuals with obesity) wore accelerometers for a mean of 5.7 days for a mean of 14.4 hours per day. The mean number of steps per day was 9124. There were 1165 deaths over a mean 10.1 years of follow-up, including 406 CVD and 283 cancer deaths. The unadjusted incidence density for all-cause mortality was 76.7 per 1000 person-years (419 deaths) for the 655 individuals who took less than 4000 steps per day; 21.4 per 1000 person-years (488 deaths) for the 1727 individuals who took 4000 to 7999 steps per day; 6.9 per 1000 person-years (176 deaths) for the 1539 individuals who took 8000 to 11 999 steps per day; and 4.8 per 1000 person-years (82 deaths) for the 919 individuals who took at least 12 000 steps per day. Compared with taking 4000 steps per day, taking 8000 steps per day was associated with significantly lower all-cause mortality (HR, 0.49 [95% CI, 0.44-0.55]), as was taking 12 000 steps per day (HR, 0.35 [95% CI, 0.28-0.45]). Unadjusted incidence density for all-cause mortality by peak 30 cadence was 32.9 per 1000 person-years (406 deaths) for the 1080 individuals who took 18.5 to 56.0 steps per minute; 12.6 per 1000 person-years (207 deaths) for the 1153 individuals who took 56.1 to 69.2 steps per minute; 6.8 per 1000 person-years (124 deaths) for the 1074 individuals who took 69.3 to 82.8 steps per minute; and 5.3 per 1000 person-years (108 deaths) for the 1037 individuals who took 82.9 to 149.5 steps per minute. Greater step intensity was not significantly associated with lower mortality after adjustment for total steps per day (eg, highest vs lowest quartile of peak 30 cadence: HR, 0.90 [95% CI, 0.65-1.27]; P value for trend = .34).

Conclusions and Relevance

Based on a representative sample of US adults, a greater number of daily steps was significantly associated with lower all-cause mortality. There was no significant association between step intensity and mortality after adjusting for total steps per day.

This study uses National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data to examine the dose-response relationships between step count (steps/d) and step intensity (steps/min) and mortality in a representative sample of US adults aged 40 years or older.

Introduction

A goal of 10 000 steps per day is promoted widely, but evidence for this goal is limited,1 and evidence from prospective mortality studies is incomplete. Higher step counts have been associated with lower mortality, but previous investigations have been conducted in older adults,2,3 in individuals with debilitating chronic conditions,4,5 or in cohorts with relatively few deaths,6 which may limit the generalizability of these findings. Furthermore, although higher gait speeds and self-reported walking pace have been associated with lower mortality risk,7,8 there is conflicting evidence that higher accelerometer-measured step intensity is associated with better health. In cross-sectional analyses, Tudor-Locke et al9 reported that higher step cadence was associated with better cardiometabolic health after adjustment for total steps per day in women, but not in men. In contrast, among 16 741 women, Lee et al3 reported that step intensity was not significantly associated with lower mortality after adjustment for total steps per day. Hence, it is unclear whether accelerometer-measured step intensity is associated with better health independent of total steps per day, particularly in men and younger adults. The purpose of this study was to describe the dose-response relationships between step count (steps/d) and step intensity (or cadence; steps/min) and mortality in a representative sample of US adults aged 40 years or older. Taking more steps and stepping at a higher intensity were hypothesized to be associated with lower mortality risk.

Methods

Study Population

The National Center for Health Statistics ethics review board approved the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) protocols, and written informed consent was obtained for all participants. This analysis involving de-identified data with no direct participant contact is not considered to be human subjects research and was not subject to institutional review board review, based on National Institutes of Health policy. NHANES is a representative sample of noninstitutionalized US adults.10 From 2003 to 2006, participants were asked to wear an ActiGraph model 7164 accelerometer on the hip during waking hours for a 7-day period.10 Non–wear time was defined using an automated algorithm,10 and individuals with at least 1 day of valid wear (ie, ≥10 h/d) were included. Although activity count data from the 2003 to 2004 NHANES cycle has been publicly available, step count data from this cycle were not released because of missing data. In 2016, missing step data were imputed using semiparametric multiple imputation,11 and these data were included in these analyses. Self-reported race or ethnicity using fixed categories was collected to characterize the population and facilitate oversampling of non-Hispanic black individuals and Mexican American individuals. Self-reported demographic information (age, sex, education); health behaviors (alcohol intake, smoking); and diagnoses of diabetes, heart disease, heart failure, stroke, cancer, chronic bronchitis, and emphysema were collected. Height and weight were measured. Diet quality was assessed with 24-hour recall-based measures of 12 dietary components integrated as the 2005 Healthy Eating index12 (scale range, 0-100; higher scores indicate healthier diet). Self-reported general health was assessed using the question, “Would you say your health in general is excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?” Mobility limitations (difficulty walking 0.25 miles, without special equipment, or up 10 steps) were assessed among participants who were older than 60 years or who were younger than 60 years but reported limitations related to work, memory problems, or other physical or mental limitations.

Stepping Amount and Intensity

ActiGraph 7164 step counts were recorded over 1-minute intervals. Step counts from this device have been found to be accurate at the population level, recording 99% of daily step counts, in comparison with the ankle-worn Stepwatch,13 an accurate and precise reference measure.13,14 ActiGraph step counts are also highly correlated with Stepwatch (r = 0.837).13 Total step counts (steps/d) were computed by summing daily steps and calculating median values from the valid days for each participant. Step intensity, or cadence, was estimated using 3 metrics. Bout cadence was determined by first identifying extended bouts of stepping (ie, ≥2 consecutive minutes at ≥60 steps/min [slow walking15]) across valid days. From these bouts, mean bout cadence (steps/min) was calculated. We also calculated peak 30-minute (peak 30) and peak 1-minute (peak 1) cadence.15 Peak 30 cadence was calculated by selecting the 30 highest cadence values each day, calculating the mean of these daily values, and then calculating a mean over all days. Peak 1 cadence was calculated by selecting the minute with the highest cadence value on each day, and then calculating the mean over all days.

Mortality Ascertainment

The primary outcome was all-cause mortality, assessed via the National Death Index.16 Secondary outcomes were defined using underlying causes of death with International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) codes for cardiovascular disease (CVD; ICD-10 code 053-075) and cancer (ICD-10 code 019-043).

Statistical Analysis

Cox proportional hazard models were used to model mortality associations from the interview date to either the date of death or censoring (December 31, 2015), whichever came first. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs were adjusted for covariates selected based on previous investigation,17 including age; sex; race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Mexican American, other); education level (<high school, high school diploma, >than high school); diet quality (continuous); alcohol consumption (never, former, current, unknown); smoking status (never, former, current); body mass index (BMI; <25, 25-29.9, ≥30); self-reported general health (excellent, very good, good, fair, poor, unknown); mobility limitation (no physical/mental limitations, no mobility limitation, limited mobility, unknown); and diagnoses of diabetes (yes, no, borderline), heart disease (yes, no, unknown), heart failure (yes, no, unknown), stroke (yes, no), cancer (yes, no), chronic bronchitis (never, former, current, unknown), and emphysema (yes, no, unknown). Given the small amount of missing data (≤5% for a given covariate), we classified these values as missing/unknown in our models. Results for our primary all-cause mortality outcome are reported without adjustment for multiple comparisons.

We estimated the dose-response relationship between steps per day and mortality with restricted cubic spline functions using 3 knots placed at the fifth, 50th, and 95th sample-weighted percentiles (ie, approximately 3000 steps per day for the fifth, 9000 for the 50th, and 16 000 for the 95th percentile).18 The 10th percentile (approximately 4000 steps/d) was used as the reference. Step intensity values were classified into weighted quartiles and modeled with and without adjustment for steps per day. Tests for trend across quartiles were examined using ordinal values in separate models. Participants who had no extended stepping bouts recorded were evaluated as a distinct group and compared with the lower quartile of step intensity.

Adjusted mortality rates (MRs) were estimated from the Cox proportional hazard regression models as 1 − adjusted population attributable risk (PAR)19 × group-specific US population–specific annual mortality rate for 2003 (ie, per 1000 adults/y).20 In computing the PAR, an MR was estimated from the Cox regression as R = I ∑ wi ri, where I was the baseline hazard rate and wi and ri were the sample weight and relative risk evaluated at the observed activity level and covariate/confounder levels of each study individual i, respectively, and the sum is over all the study individuals. We compute the “counterfactual” mortality rate as R* = I ∑ wi ri*, where ri* is the counterfactual relative risk in which the activity is set to a fixed level for the study participants at which the adjusted mortality rate is computed. The PAR is (R - R*)/R, and the baseline hazard rate I cancels out of this expression. To explore the relationship to mortality risk between step counts and step intensity, we examined mortality risk in jointly classified categories of each exposure with low step counts (<4000 steps/d) and low step intensity (lower quartile) as a common reference group. In detailed analyses assessing confounding in the association between step count and mortality, sequential models were fit adjusting only for sex; sex and age; and sex, age, and all covariates.

To assess model fit we calculated the C statistic in models with all covariates and recalculated the C statistics after the addition of steps per day. To assess the association of missing data on results we compared results from our analytic sample with a complete case sample. Sensitivity analyses were completed to evaluate confounding and potential effect modification using stratification and tests for interaction/heterogeneity for educational status, behavioral risk factors (smoking, alcohol, diet), comorbid conditions (heart disease, stroke, heart failure, diabetes, chronic bronchitis, emphysema, cancer), self-reported health, mobility limitations, length of follow-up, extended stepping bouts, and for those with imputed steps data. Because of the potential for type I error due to multiple comparisons, findings for analyses of secondary end points and subgroup analyses should be interpreted as exploratory.

We examined the proportional hazards assumption by testing statistical significance of interactions between follow-up time and exposures. We used PROC SurveyPhreg and MIANALYZE (SAS version 9.4)21 accounting for the complex sample design and the variance from five imputations of steps. Two-sided P values <.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Of 6355 adults aged at least 40 years at the time of the survey, 4840 had valid accelerometer data. Of these individuals, 2435 (54%) were women. Individuals who wore the accelerometer had significantly higher levels of education. The group who wore the accelerometer had a higher proportion of people who had a BMI greater than 30 or were current consumers of alcohol and a smaller proportion of people with heart disease, heart failure, mobility limitations, fair or poor health, or stroke (eTable S1 in the Supplement). Participants who took more steps were significantly younger, had lower BMIs, lower diet quality, a higher education level, and included a higher proportion of current drinkers, but had lower prevalence of comorbid conditions (eg, diabetes, heart disease, cancer) and mobility limitations and a lower rate of reporting fair or poor general health (Table 1). The majority of participants (4416 of 4840 [91%]) had complete covariate data. The accelerometer was worn for a mean of 5.7 days for a mean of 14.4 hours per day; 94% of participants wore the monitor for at least 10 hours a day (ie, valid wear) for at least 3 days, and 14% had imputed step data. Participants took a mean of 9124 steps per day. During a mean 10.1 years of follow-up (weighted), there were 1165 deaths, including 406 CVD and 283 cancer deaths. The C statistic increased from 0.787 to 0.824 after adding steps per day to the covariate-adjusted model, indicating improved model fit (eTable S2 in the Supplement). Preliminary analysis revealed substantial attenuation in the association between steps per day and mortality with increasing adjustment for covariates (Table 2); therefore, results for models adjusted for all covariates are reported.

Table 1. Descriptive Characteristics and Number of Steps per Day of Participants in a Study of the Association of Daily Step Count and Step Intensity With Mortality Among US Adults Aged at Least 40 Yearsa.

| Characteristic | Steps/d, No. (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <4000 (n = 655) | 4000-7999 (n = 1727) | 8000-11 999 (n = 1539) | ≥12 000 (n = 919) | Total (N = 4840) | P valueb | |

| Age, mean (95% CI), y | 69.9 (68.6-71.1) | 59.9 (59.1-60.7) | 54.0 (53.2-54.7) | 51.1 (50.5-51.7) | 56.8 (56.2-57.4) | <.001 |

| BMI, mean (95% CI) | 31.4 (30.6-32.2) | 29.9 (29.5-30.3) | 28.6 (28.2-28.9) | 27.1 (26.8-27.4) | 28.9 (28.7-29.2) | <.001 |

| HEI 2005 score,c mean (95% CI) | 57.5 (56.3-58.7) | 57.2 (56.5-57.9) | 56.9 (56.1-57.7) | 55.5 (54.3-56.8) | 56.8 (56.2-57.3) | .03 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Men | 293 (37.8) | 771 (38.9) | 750 (47.6) | 591 (59.8) | 2405 (46.5) | <.001 |

| Women | 362 (62.2) | 956 (61.1) | 789 (52.4) | 328 (40.2) | 2435 (53.5) | |

| Race/ethnicityd | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 412 (79.6) | 1000 (78.5) | 816 (76.6) | 453 (76.1) | 2681 (77.4) | .03 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 142 (12.6) | 363 (10.5) | 330 (10.3) | 158 (8.5) | 993 (10.2) | |

| Mexican American | 74 (2.9) | 272 (4.1) | 296 (5.3) | 245 (7.9) | 887 (5.3) | |

| Other | 27 (4.9) | 92 (6.8) | 97 (7.7) | 63 (7.5) | 279 (7.1) | |

| BMI | ||||||

| 13.4-24.9 (Normal) | 178 (23.6) | 445 (25.1) | 377 (26.7) | 313 (36.7) | 1313 (28.1) | <.001 |

| 25.0-29.9 (Overweight) | 190 (27.0) | 608 (33.9) | 618 (38.8) | 379 (38.5) | 1795 (36.0) | |

| 30.0-62.5 (Obese) | 287 (49.3) | 674 (41.1) | 544 (34.6) | 227 (24.8) | 1732 (35.9) | |

| Education | ||||||

| <High school | 266 (32.0) | 501 (18.2) | 400 (13.7) | 285 (16.0) | 1452 (17.4) | <.001 |

| High school | 157 (26.0) | 453 (27.8) | 359 (24.5) | 218 (27.5) | 1187 (26.4) | |

| >High school | 232 (42.0) | 773 (54.0) | 780 (61.8) | 416 (56.5) | 2201 (56.2) | |

| Alcohol | (n = 607) | (n = 1640) | (n = 1440) | (n = 871) | (n = 4558) | |

| Never drinker | 126 (19.2) | 248 (12.9) | 190 (11.1) | 62 (6.5) | 626 (11.4) | <.001 |

| Former drinker | 140 (23.6) | 337 (20.8) | 260 (17.3) | 118 (12.0) | 855 (17.9) | |

| Current drinker | 341 (57.2) | 1055 (66.3) | 990 (71.6) | 691 (81.6) | 3077 (70.7) | |

| Smoking | ||||||

| Never smoker | 283 (42.8) | 775 (45.2) | 763 (50.0) | 413 (45.7) | 2234 (46.8) | .62 |

| Former smoker | 263 (38.5) | 608 (32.9) | 474 (30.1) | 288 (31.5) | 1633 (32.1) | |

| Current smoker | 109 (18.7) | 344 (22.0) | 302 (19.9) | 218 (22.8) | 973 (21.1) | |

| Diabetes | ||||||

| Yes | 204 (29.9) | 284 (13.9) | 168 (7.8) | 69 (4.5) | 725 (11.2) | <.001 |

| No | 429 (66.8) | 1403 (84.0) | 1346 (90.7) | 841 (94.6) | 4019 (87.1) | |

| Borderline | 22 (3.2) | 40 (2.1) | 25 (1.5) | 9 (0.9) | 96 (1.7) | |

| Stroke | ||||||

| Yes | 102 (15.4) | 103 (4.8) | 36 (1.9) | 15 (1.1) | 256 (3.9) | <.001 |

| No | 553 (84.6) | 1624 (95.2) | 1503 (98.1) | 904 (98.9) | 4584 (96.1) | |

| Coronary heart disease | (n = 646) | (n = 1715) | (n = 1534) | (n = 918) | (n = 4813) | |

| Yes | 96 (15.0) | 130 (6.7) | 70 (3.8) | 23 (2.1) | 319 (5.4) | <.001 |

| No | 550 (85.0) | 1585 (93.3) | 1464 (96.2) | 895 (97.9) | 4494 (94.6) | |

| Heart failure | (n = 642) | (n = 1719) | (n = 1539) | (n = 918) | (n = 4818) | |

| Yes | 102 (16.2) | 92 (4.5) | 38 (1.7) | 12 (1.0) | 244 (3.8) | <.001 |

| No | 540 (83.8) | 1627 (95.5) | 1501 (98.3) | 906 (99.0) | 4574 (96.2) | |

| Cancer | ||||||

| Yes | 140 (22.0) | 288 (16.2) | 162 (11.7) | 50 (6.1) | 640 (12.9) | <.001 |

| No | 515 (78.0) | 1439 (83.8) | 1377 (88.3) | 869 (93.9) | 4200 (87.1) | |

| Chronic bronchitis | (n = 650) | (n = 1722) | (n = 1537) | (n = 914) | (n = 4823) | |

| Current | 48 (8.4) | 76 (5.8) | 39 (2.5) | 12 (1.6) | 175 (3.9) | <.001 |

| Former | 34 (6.4) | 78 (5.3) | 43 (3.1) | 25 (3.1) | 180 (4.1) | |

| Never | 568 (85.2) | 1568 (88.9) | 1455 (94.4) | 877 (95.3) | 4468 (91.9) | |

| Emphysema | (n = 650) | (n = 1723) | (n = 1537) | (n = 918) | (n = 4828) | |

| Yes | 54 (8.2) | 73 (4.2) | 23 (1.2) | 5 (0.5) | 155 (2.7) | <.001 |

| No | 596 (91.8) | 1650 (95.8) | 1514 (98.8) | 913 (99.5) | 4673 (97.3) | |

| Mobility limitatione | (n = 650) | (n = 1725) | (n = 1539) | (n = 919) | (n = 4833) | |

| Yes | 462 (68.7) | 597 (31.5) | 232 (12.0) | 64 (5.0) | 1355 (22.2) | .01 |

| No | 164 (24.7) | 761 (36.4) | 610 (31.5) | 298 (24.3) | 1833 (30.9) | |

| No physical/mental limitations | 24 (6.7) | 367 (32.0) | 697 (56.5) | 557 (70.6) | 1645 (46.9) | |

| General health | (n = 609) | (n = 1644) | (n = 1442) | (n = 874) | (n = 4569) | |

| Excellent | 23 (3.7) | 115 (7.7) | 171 (13.3) | 108 (15.2) | 417 (11.0) | <.001 |

| Very good | 92 (16.0) | 415 (30.2) | 444 (36.8) | 273 (37.7) | 1224 (32.9) | |

| Good | 211 (34.1) | 654 (39.2) | 524 (35.7) | 322 (35.6) | 1711 (36.7) | |

| Fair/poor | 283 (46.1) | 460 (2.8) | 303 (14.1) | 171 (11.5) | 1217 (19.4) | |

Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared).

Percentages, means, and CIs were estimated using US population weights.

P values were computed separately for each covariate and indicate statistically significant differences between step groups if P < .05.

Healthy Eating Index (HEI) 2005 scores describe an individual diet quality as recommended by the 2005 Dietary Guidelines for Americans (range, 0 [least healthy] to 100 [most healthy]).

Race/ethnicity was determined using preferred terminology from the National Center for Health Statistics as non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, and Mexican American. Mexican American individuals were oversampled rather than broader groups of individuals from Latin America. Other includes Asian, other Hispanic, Alaskan native, and multiracial individuals.

Mobility limitation was assessed among participants aged at least 60 years or among younger individuals reporting some type of physical or mental limitation. Mobility limitation was defined as a report of having difficulty walking for a quarter mile without special equipment or walking up 10 steps.

Table 2. Evaluation of Confounding in the Association Between Steps per Day and All-Cause Mortality With Increasing Adjustment for Confounding Factors in a Study of the Association of Daily Step Count and Step Intensity With Mortality Among US Adults Aged at Least 40 Years.

| Steps/d | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1a | Model 2b | Model 3c | |

| 12 000 | 0.09 (0.07-0.11) | 0.23 (0.19-0.29) | 0.35 (0.28-0.45) |

| 8000 | 0.21 (0.18-0.24) | 0.38 (0.32-0.43) | 0.49 (0.44-0.55) |

| 4000 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

Model 1: steps per day + sex.

Model 2: steps per day + sex + age.

Model 3: model 2 + diet quality, race/ethnicity, body mass index, education, alcohol consumption, smoking status, diabetes, stroke, coronary heart disease, heart failure, cancer, chronic bronchitis, emphysema, mobility limitation, and self-reported general health.

Step Counts and All-cause Mortality

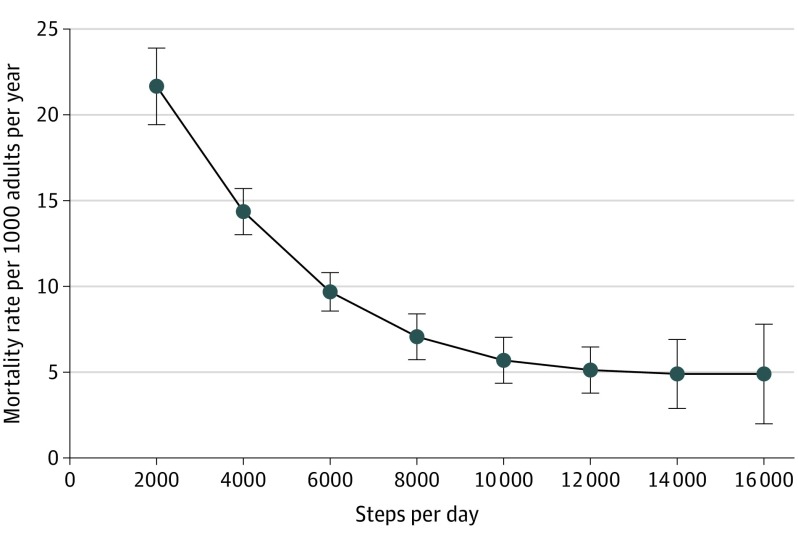

The unadjusted incidence density rate for all-cause mortality was 76.7 per 1000 person-years (419 deaths) for the 655 individuals who took less than 4000 steps per day; 21.4 per 1000 person-years (488 deaths) for the 1727 individuals who took 4000 to 7999 steps per day; 6.9 per 1000 person-years (176 deaths) for the 1539 individuals who took 8000 to 11 999 steps per day; and 4.8 per 1000 person-years (82 deaths) for the 919 individuals who took at least 12 000 steps per day (Table 3). Taking 2000 steps per day was associated with significantly higher all-cause mortality compared with the reference group (10th percentile) of individuals who took 4000 steps per day (MR: 21.7 [95% CI, 19.4-23.9] vs 14.4 [95% CI, 13.0-15.7] per 1000 adults per year; HR, 1.51 [95% CI, 1.41-1.62]). Taking 8000 steps per day was associated with significantly lower all-cause mortality compared with 4000 steps day (MR: 7.1 [95% CI, 5.7-8.4] vs 14.4 [95% CI, 13.0-15.7] per 1000 adults per year; HR, 0.49 [95% CI, 0.44-0.55]). Taking 12 000 steps per day was associated with significantly lower all-cause mortality compared with 4000 steps per day (MR: 5.1 [95% CI, 3.8-6.5] vs 14.4 [95% CI, 13.0-15.7] per 1000 adults per year; HR, 0.35 [95% CI, 0.28-0.45]) (Figure 1 and eTable S3 in the Supplement).

Table 3. Number of Deaths and Unadjusted Mortality Rates for All-Cause, Cardiovascular Disease, and Cancer Mortality in a Study of the Association of Daily Step Count and Step Intensity With Mortality Among US Adults Aged at Least 40 Yearsa.

| Mortality | Steps/d | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <4000 (n = 655) | 4000-7999 (n = 1727) | 8000-11 999 (n = 1539) | ≥12 000 (n = 919) | Total (N = 4840) | |

| All-cause | |||||

| Deaths, No. (%) | 419 (56.5) | 488 (21.3) | 176 (7.3) | 82 (5.1) | 1165 (16.1) |

| Mortality rate per 1000 person-years | 76.7 | 21.4 | 6.9 | 4.8 | 16.0 |

| Cardiovascular disease | |||||

| Deaths, No. (%) | 169 (23.2) | 162 (6.5) | 52 (2.3) | 23 (1.1) | 406 (5.4) |

| Mortality rate per 1000 person-years | 31.6 | 6.6 | 2.1 | 1.0 | 5.4 |

| Cancer | |||||

| Deaths, No. (%) | 62 (7.8) | 133 (6.4) | 56 (2.5) | 32 (2.0) | 283 (4.1) |

| Mortality rate per 1000 person-years | 10.5 | 6.4 | 2.3 | 1.8 | 4.1 |

Percentages and mortality rates were estimated using US population weights.

Figure 1. Steps per Day and All-Cause Mortality in a Study of the Association of Daily Step Count and Step Intensity With Mortality Among US Adults Aged at Least 40 Years.

Mortality rates were adjusted for age; diet quality; sex; race/ethnicity; body mass index; education; alcohol consumption; smoking status; diagnoses of diabetes, stroke, coronary heart disease, heart failure, cancer, chronic bronchitis, and emphysema; mobility limitation; and self-reported general health. Rates were computed using the 2003 mortality rate for US adults (11.4 deaths per 1000 adults per year). Models included US population and study design weights to account for the complex survey design and models were replicated 5 times to account for imputed steps data. Error bars indicate 95% CIs.

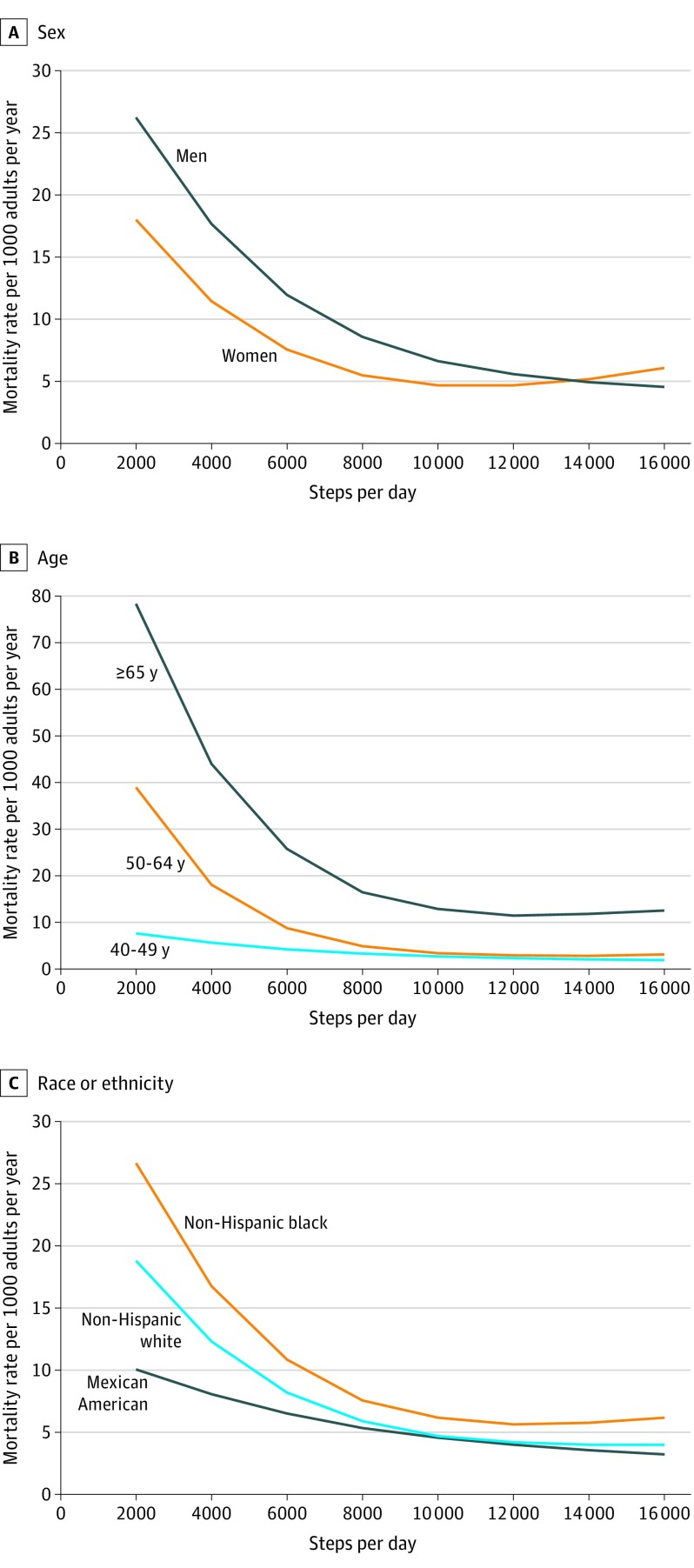

Higher step counts per day (8000 vs 4000) were associated with significantly lower all-cause mortality among men (MR: 8.6 [95% CI, 5.5-11.6] vs 17.7 [95% CI, 15.6-19.7] per 1000 adults per year; HR, 0.48 [95% CI, 0.41-0.58]), women (MR: 5.5 [95% CI, 4.1-6.8] vs 11.4 [95% CI, 10.3-12.6] per 1000 adults per year; HR, 0.48 [95% CI, 0.37-0.62]), younger adults (aged 40-49 years; MR: 3.3 [95% CI, 2.4-4.2] vs 5.6 [95% CI, 2.5-8.8] per 1000 adults per year; HR, 0.58 [95% CI, 0.35-0.96]), older adults (aged ≥65 years; MR: 16.5 [95% CI, 14.4-18.6] vs 44.0 [95% CI, 41.2-46.8] per 1000 adults per year; HR, 0.38 [95% CI, 0.32-0.44]), non-Hispanic white participants (MR: 5.9 [95% CI, 4.5-7.3] vs 12.3 [95% CI, 10.9-13.7] per 1000 adults per year; HR, 0.48 [95% CI, 0.42-0.55]), non-Hispanic black participants (MR: 7.6 [95% CI, 5.4-9.7] vs 16.8 [95% CI, 14.4-19.2] per 1000 adults per year; HR, 0.45 [95% CI, 0.35-0.59]), and Mexican American participants (MR: 5.3 [95% CI, 2.8-7.9] vs 8.1 [95% CI, 4.1-12.0] per 1000 adults per year; HR, 0.66 [95% CI, 0.45-0.98]) (Figure 2 and eTables S4-S6 in the Supplement).

Figure 2. Steps per Day and Mortality by Sex, Age, and Race/Ethnicity in a Study of the Association of Step Count and Intensity With Mortality.

Mortality rates were adjusted for age; diet quality; sex; race/ethnicity; body mass index; education; alcohol consumption; smoking status; 7 comorbid conditions; mobility limitation; and self-reported general health (not including the demographic of interest). Rates were computed using 2003 US mortality rates by sex (men, 13.0 deaths per 1000 adults/y; women, 9.9 deaths per 1000 adults/y), age (40-49 y, 3.1 deaths per 1000 adults/y; 50-64 y, 9.4 deaths per 1000 adults/y; ≥65 y, 35.8 deaths per 1000 adults/y), and race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, 10.0 deaths per 1000 adults/y; non-Hispanic black, 13.8 deaths per 1000 adults/y; Mexican American, 5.6 deaths per 1000 adults/y). Models included US population and study design weights to account for the complex survey design and were replicated 5 times to account for imputed steps data.

Step Intensity and All-cause Mortality

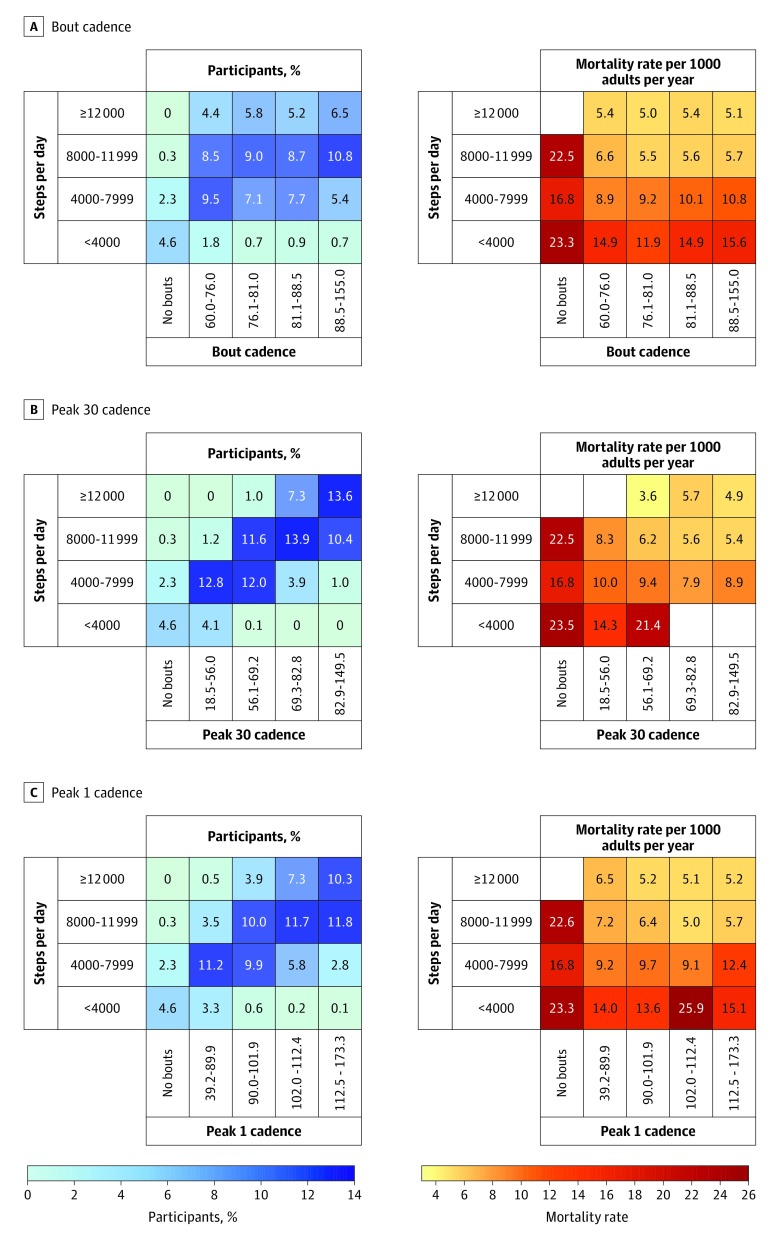

Unadjusted incidence density for all-cause mortality by peak 30 cadence was 32.9 per 1000 person-years (406 deaths) for the 1080 individuals who took 18.5 to 56.0 steps per minute; 12.6 per 1000 person-years (207 deaths) for the 1153 individuals who took 56.1 to 69.2 steps per minute; 6.8 per 1000 person-years (124 deaths) for the 1074 individuals who took 69.3 to 82.8 steps per minute; and 5.3 per 1000 person-years (108 deaths) for the 1037 individuals who took 82.9 to 149.5 steps per minute. Higher step intensity was associated with significantly lower mortality for peak 30 and peak 1 cadence after adjusting for covariates, but not after additional adjustment for total steps per day (eTable S7 in the Supplement). For example, mortality risk for peak 30 cadence was lower before adjustment for total steps per day (MR: 5.2 [95% CI, 3.2-7.3] vs 10.0 [95% CI, 7.1-12.9] per 1000 adults per year; HR, 0.52 [95% CI, 0.37-0.74]; Pvalue for trend <.001) but not after adjustment for total steps per day (MR: 8.4 [95% CI, 4.0-12.9] vs 9.4 [95% CI, 6.9-11.8] per 1000 adults per year; HR, 0.90 [95% CI, 0.65-1.27]; P value for trend = .34) when comparing upper cadence quartiles with lower cadence quartiles. Similar results were observed in men, women, and older adults (eTables S8-S12 in the Supplement).

Steps per day and step intensity were significantly correlated (P < .01 for bout cadence [r = 0.17], peak 30 cadence [r = 0.77], and peak 1 cadence [r = 0.63]; Figure 3 and eTable S13 in the Supplement). Evaluation of mortality rates (Figure 3) revealed higher mortality for those with no extended stepping bouts (MR range, 16.8-23.5 per 1000 adults per year) and those who took less than 4000 steps per day (peak 30 cadence; MR range, 14.3-23.5 per 1000 adults per year), while taking 12 000 or more steps per day was associated with lower mortality (peak 30 cadence; MR range, 3.6-5.7 per 1000 adults per year). Within groups stratified by daily step count, higher step intensity was not significantly associated with lower mortality. For example, for individuals who took less than 4000 steps per day, the adjusted MR was 14.9 per 1000 adults per year in the lowest bout cadence quartile and 15.6 per 1000 adults per year in highest quartile (Figure 3 and eTable S14 in the Supplement).

Figure 3. Joint Associations Between Steps per Day, Step Intensity, and All-Cause Mortality in a Study of the Association of Daily Step Count and Step Intensity With Mortality Among US Adults Aged at Least 40 Years.

Mortality rates were adjusted for age; diet quality; sex; race/ethnicity; body mass index; education; alcohol consumption; smoking status; diagnoses of diabetes, stroke, coronary heart disease, heart failure, cancer, chronic bronchitis, and emphysema; mobility limitation; and self-reported general health. Rates were computed using the 2003 mortality rate for US adults (11.4 deaths per 1000 adults per year). Blank cells indicate joint classifications with 0 participants and instances in which mortality rates could not be estimated. Models included US population and study design weights to account for the complex survey design and models were replicated 5 times to account for imputed steps data.

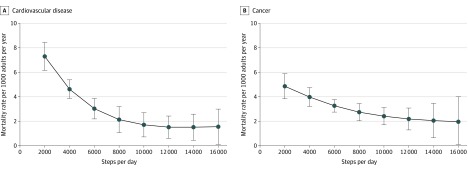

Cardiovascular Disease and Cancer Mortality

Participants who took 8000 steps per day, compared with 4000 steps per day, had significantly lower CVD mortality (MR: 2.1 [95% CI, 1.1-3.2] vs 4.6 [95% CI, 3.9-5.4] per 1000 adults per year; HR, 0.49 [95% CI, 0.40-0.60]) and cancer mortality (MR: 2.7 [95% CI, 2.0-3.4] vs 4.0 [95% CI, 3.2-4.7] per 1000 adults per year; HR, 0.67 [95% CI, 0.54-0.82]) (Figure 4 and eTable S15 in the Supplement). No significant associations of step intensity with CVD or cancer mortality were found in models that adjusted for total steps per day (eTables S16 and S17 in the Supplement).

Figure 4. Steps per Day and Mortality From Cardiovascular Disease (CVD) and Cancer in a Study of the Association of Daily Step Count and Step Intensity With Mortality Among US Adults Aged at Least 40 Years.

Mortality rates were adjusted for age; diet quality; sex; race/ethnicity; body mass index; education; alcohol consumption; smoking status; diagnoses of diabetes, stroke, coronary heart disease, heart failure, cancer, chronic bronchitis, and emphysema; mobility limitation; and self-reported general health. Rates were computed using 2003 mortality rates for US adults (cardiovascular disease, 3.9 deaths per 1000 adults per year; cancer, 3.3 deaths per 1000 adults per year). Models included US population and study design weights to account for the complex survey design and models were replicated 5 times to account for imputed steps data. Error bars indicate 95% CIs.

Sensitivity Analysis

The association of steps per day with all-cause mortality was not significantly different when data were analyzed by education (<high school, high school, >high school), smoking habits (never, former, current), alcohol use (never, former, current), diet (tertiles; eFigure S1 in the Supplement), presence vs absence of 7 comorbid conditions (eFigure S2 in the Supplement), self-reported health (fair/poor, good, very good/excellent), ability to accumulate extended stepping bouts, length of follow-up (eFigure S3 in the Supplement), or those with any imputed step data (eFigure S4 in the Supplement). A significant interaction was present for mobility limitation status and the association of step count with mortality, but the association between step count and mortality was statistically significant in each group (eFigure S3 in the Supplement). The magnitude and significance of associations between all-cause mortality and step counts and step intensity was similar in results from the analytic and complete case analysis (eTables S18 and S19 in the Supplement).

Discussion

In this nationally representative cohort of US adults aged 40 years and older, a greater number of steps per day was significantly associated with lower all-cause, CVD, and cancer mortality. Compared with individuals who took 4000 steps per day, taking 8000 steps per day at baseline was associated with a hazard ratio point estimate of 0.49 and taking 12 000 steps per day was associated with a hazard ratio point estimate of 0.35 for all-cause mortality. Higher step counts were associated with lower all-cause mortality risk among men, women, non-Hispanic white participants, non-Hispanic black participants, and Mexican American participants. In contrast, there was no significant association between higher step intensity and mortality after adjusting for total steps per day.

Previous mortality studies conducted in older adults (eg, aged ≥70 years),2,3 in patients with heart failure5 and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,4 and in smaller cohorts with fewer deaths6 have also shown a higher number of steps per day to be associated with lower mortality. Results in this study using data from the NHANES accelerometer cohort, a representative sample of US adults aged at least 40 years with oversampling of non-Hispanic black and Mexican American individuals, provided a population-based description of the dose-response relationship between steps per day and mortality.

Studies of measured gait speed7 and self-reported walking speed8 have reported that higher walking speeds were associated with lower mortality risk, but there has been limited evidence that free-living step intensity (cadence), was associated with lower mortality. Lee et al3 found no significant association between cadence and mortality after adjustment for total steps in older women. Results from the study reported here also showed no significant association between free-living cadence and mortality risk after accounting for total steps per day, similar to the results of the study by Lee et al3 in women. Results reported here suggest there is also no association between step intensity in men and younger adults. Previous investigations of measured gait speed and reported walking speed did not include objective step count data to determine whether the associations between walking speed and mortality were independent of the total number of steps taken per day. In the present study, total steps per day were positively correlated with step intensity, suggesting that individuals who took more steps per day tended to have higher cadence. Future studies of walking intensity and mortality using more sophisticated measures of cadence22 could help confirm these findings and explain possible differences in mortality rates when using measures of cadence, gait speed, and self-reported walking speed.

Wearable activity monitors that count steps are widely available and provide immediate feedback to the user. When combined with proven behavioral strategies, they may be an effective way to increase physical activity.23 Translation of findings from the data in this report to clinical and public health settings should consider an individual’s fitness, health status, and baseline step count in setting short-term (eg, days, weeks) and long-term (eg, months, years) goals. It is also important to note that accuracy can vary from one step counting device to another.24 Step counts can vary between devices by 20% or more,14,25 which is a substantial amount of steps per day (eg, 20% of 10 000 steps/d is 2000). However, even with known differences among devices, step counts from most monitors are highly correlated (r >0.80).13,14

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, data reported here are observational and no causal inferences can be made. Second, the results are likely affected by unmeasured and residual confounding, and higher step counts reflect better overall health. Although analyses controlled for key demographic indicators, behavioral risk factors, self-reported health, 7 chronic conditions, and BMI, the true strength of association remains uncertain. Furthermore, the presence of peripheral artery disease and comorbidity severity, which are likely confounders, were not controlled for. Third, steps measured by the ActiGraph 7164 may be due to physical activity other than walking (eg, dancing, gardening, housework) and the device does not detect nonambulatory activities (eg, swimming, cycling). Fourth, the cadence estimates (steps/min) used here should be interpreted cautiously because these values reflect the number of steps accumulated per minute of observation on the accelerometer clock, rather than the number steps taken during a full minute of stepping.22 Fifth, death certificates may not accurately represent the true cause of death. Sixth, there were significant differences between individuals included in these analyses and those excluded because of missing data. Results may not be generalizable to those individuals with missing data who were not included. Seventh, although the stability of accelerometer measurements derived from a 7-day administration is relatively high over 6 months to several years (intraclass correlations, 0.6-0.826,27), these results do not account for changes in step counts over time.

Conclusions

Based on a representative sample of US adults, a greater number of steps per day was significantly associated with lower all-cause mortality. There was no significant association between step intensity and all-cause mortality after adjusting for the total number of steps per day.

Table S1. Comparison between those in the analytic sample (Accelerometer) and those who did not wear the device or who did not have at least one valid wear day (No accelerometer)

Table S2. Evaluation of model fit (C statistic) comparing covariate adjusted model 1 to model 2 with additional adjustment for steps/day

Table S3. Adjusted hazard ratios and mortality rates for all-cause mortality

Table S4. Adjusted hazard ratios and mortality rates for all-cause mortality, by sex

Table S5. Adjusted hazard ratios and mortality rates for all-cause mortality, by age group

Table S6. Adjusted hazard ratios and mortality rates for all-cause mortality, by race-ethnicity

Table S7. Association between stepping intensity and all-cause mortality

Table S8. Adjusted hazard ratios for all-cause mortality across quartiles of step intensity using walking bout cadence, peak 30-min cadence, and peak 1-min cadence – men

Table S9. Adjusted hazard ratios for all-cause mortality across quartiles of step intensity using walking bout cadence, peak 30-min cadence, and peak 1-min cadence – women

Table S10. Adjusted hazard ratios for all-cause mortality across quartiles of step intensity using walking bout cadence, peak 30-min cadence, and peak 1-min cadence – age 40-49 years

Table S11. Adjusted hazard ratios for all-cause mortality across quartiles of step intensity using walking bout cadence, peak 30-min cadence, and peak 1-min cadence – age 50-64 years

Table S12. Adjusted hazard ratios for all-cause mortality across quartiles of step intensity using walking bout cadence, peak 30-min cadence, and peak 1-min cadence – age 65+ years

Table S13. Correlation matrix for stepping intensity and total steps per day

Table S14. All-cause mortality rates (per 1,000 adults/year) for the joint associations between steps per day and stepping intensity

Table S15. Adjusted hazard ratios and mortality rates for CVD and Cancer mortality

Table S16. Adjusted hazard ratios for cardiovascular disease mortality across quartiles of stepping intensity

Table S17. Adjusted hazard ratios for cancer mortality across quartiles of stepping intensity

Table S18. Adjusted hazard ratios for steps per day and mortality (8000 vs. 4000 steps/day) in the analytic sample and in complete case analysis

Table S19. Adjusted hazard ratios for stepping intensity and all-cause mortality (Quartile 4 vs. 1) in the analytic sample and in complete case analysis

Figure S1 – Adjusted hazard ratios for all-cause mortality stratified by education and behavioral risk factors (smoking, alcohol consumption, and healthy eating index).

Figure S2 – Adjusted hazard ratios for all-cause mortality stratified by prevalent comorbid conditions.

Figure S3 – Adjusted hazard ratios for all-cause mortality stratified by mobility limitation, self-reported general health, ability to accumulate extended stepping bouts, and length of follow-up.

Figure S4 – Adjusted hazard ratios for all-cause mortality among adults with and without imputed steps.

References

- 1.Lobelo F, Rohm Young D, Sallis R, et al. ; American Heart Association Physical Activity Committee of the Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health; Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Genomic and Precision Medicine; Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; and Stroke Council . Routine assessment and promotion of physical activity in healthcare settings: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137(18):e495-e522. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jefferis BJ, Parsons TJ, Sartini C, et al. . Objectively measured physical activity, sedentary behaviour and all-cause mortality in older men: does volume of activity matter more than pattern of accumulation? Br J Sports Med. 2019;53(16):1013-1020. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2017-098733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee IM, Shiroma EJ, Kamada M, Bassett DR Jr, Matthews CE, Buring JE. Association of step volume and intensity with all-cause mortality in older women. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(8):1105-1112. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waschki B, Kirsten A, Holz O, et al. . Physical activity is the strongest predictor of all-cause mortality in patients with COPD: a prospective cohort study. Chest. 2011;140(2):331-342. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-2521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Izawa KP, Watanabe S, Oka K, et al. . Usefulness of step counts to predict mortality in Japanese patients with heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2013;111(12):1767-1771. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.02.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dwyer T, Pezic A, Sun C, et al. . Objectively measured daily steps and subsequent long term all-cause mortality: the tasped prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2015;10(11):e0141274. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Studenski S, Perera S, Patel K, et al. . Gait speed and survival in older adults. JAMA. 2011;305(1):50-58. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yates T, Zaccardi F, Dhalwani NN, et al. . Association of walking pace and handgrip strength with all-cause, cardiovascular, and cancer mortality: a UK Biobank observational study. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(43):3232-3240. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tudor-Locke C, Schuna JM Jr, Han HO, et al. . Step-based physical activity metrics and cardiometabolic risk: NHANES 2005-2006. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2017;49(2):283-291. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Troiano RP, Berrigan D, Dodd KW, Mâsse LC, Tilert T, McDowell M. Physical activity in the United States measured by accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40(1):181-188. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e31815a51b3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu B, Yu M, Graubard BI, Troiano RP, Schenker N. Multiple imputation of completely missing repeated measures data within person from a complex sample: application to accelerometer data in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Stat Med. 2016;35(28):5170-5188. doi: 10.1002/sim.7049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Cancer Institute Epidemiology and Genetics Research Branch Healthy Eating Index: SAS code. National Cancer Institute website. Updated September 11, 2019. Accessed February 21, 2020. https://epi.grants.cancer.gov/hei/sas-code.html

- 13.Feito Y, Bassett DR, Thompson DL. Evaluation of activity monitors in controlled and free-living environments. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44(4):733-741. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182351913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Toth LP, Park S, Springer CM, Feyerabend MD, Steeves JA, Bassett DR. Video-recorded validation of wearable step counters under free-living conditions. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2018;50(6):1315-1322. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tudor-Locke C, Han H, Aguiar EJ, et al. . How fast is fast enough? Walking cadence (steps/min) as a practical estimate of intensity in adults: a narrative review. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52(12):776-788. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2017-097628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Center for Health Statistics The Linkage of National Center for Health Statistics Survey Data to the National Death Index—2015 Linked Mortality File (LMF): Methodology Overview and Analytic Considerations . Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2019. Accessed February 18, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/datalinkage/LMF2015_Methodology_Analytic_Considerations.pdf

- 17.Matthews CE, Keadle SK, Troiano RP, et al. . Accelerometer-measured dose-response for physical activity, sedentary time, and mortality in US adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;104(5):1424-1432. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.116.135129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Desquilbet L, Mariotti F. Dose-response analyses using restricted cubic spline functions in public health research. Stat Med. 2010;29(9):1037-1057. doi: 10.1002/sim.3841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Graubard BI, Flegal KM, Williamson DF, Gail MH. Estimation of attributable number of deaths and standard errors from simple and complex sampled cohorts. Stat Med. 2007;26(13):2639-2649. doi: 10.1002/sim.2734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson RN, Miniño AM, Hoyert DL, Rosenberg HM. Comparability of cause of death between ICD-9 and ICD-10: preliminary estimates. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2001;49(2):1-32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.SAS Institute The MIANALYZE Procedure In: SAS/STAT 13.1 User’s Guide: Volume 62. SAS Institute; 2013:5172-5192. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dall PM, McCrorie PR, Granat MH, Stansfield BW. Step accumulation per minute epoch is not the same as cadence for free-living adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45(10):1995-2001. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182955780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Scientific Report. US Department of Health and Human Services; 2018. Accessed February 18, 2020. https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2019-09/PAG_Advisory_Committee_Report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bassett DR Jr, Toth LP, LaMunion SR, Crouter SE. Step counting: a review of measurement considerations and health-related applications. Sports Med. 2017;47(7):1303-1315. doi: 10.1007/s40279-016-0663-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosenberger ME, Buman MP, Haskell WL, McConnell MV, Carstensen LL. Twenty-four hours of sleep, sedentary behavior, and physical activity with nine wearable devices. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2016;48(3):457-465. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keadle SK, Shiroma EJ, Kamada M, Matthews CE, Harris TB, Lee IM. Reproducibility of accelerometer-assessed physical activity and sedentary time. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52(4):541-548. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saint-Maurice PF, Sampson JN, Keadle SK, Willis EA, Troiano RP, Matthews CE. Reproducibility of accelerometer and posture-derived measures of physical activity [published online November 1, 2019]. Med Sci Sports Exerc. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000002206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Comparison between those in the analytic sample (Accelerometer) and those who did not wear the device or who did not have at least one valid wear day (No accelerometer)

Table S2. Evaluation of model fit (C statistic) comparing covariate adjusted model 1 to model 2 with additional adjustment for steps/day

Table S3. Adjusted hazard ratios and mortality rates for all-cause mortality

Table S4. Adjusted hazard ratios and mortality rates for all-cause mortality, by sex

Table S5. Adjusted hazard ratios and mortality rates for all-cause mortality, by age group

Table S6. Adjusted hazard ratios and mortality rates for all-cause mortality, by race-ethnicity

Table S7. Association between stepping intensity and all-cause mortality

Table S8. Adjusted hazard ratios for all-cause mortality across quartiles of step intensity using walking bout cadence, peak 30-min cadence, and peak 1-min cadence – men

Table S9. Adjusted hazard ratios for all-cause mortality across quartiles of step intensity using walking bout cadence, peak 30-min cadence, and peak 1-min cadence – women

Table S10. Adjusted hazard ratios for all-cause mortality across quartiles of step intensity using walking bout cadence, peak 30-min cadence, and peak 1-min cadence – age 40-49 years

Table S11. Adjusted hazard ratios for all-cause mortality across quartiles of step intensity using walking bout cadence, peak 30-min cadence, and peak 1-min cadence – age 50-64 years

Table S12. Adjusted hazard ratios for all-cause mortality across quartiles of step intensity using walking bout cadence, peak 30-min cadence, and peak 1-min cadence – age 65+ years

Table S13. Correlation matrix for stepping intensity and total steps per day

Table S14. All-cause mortality rates (per 1,000 adults/year) for the joint associations between steps per day and stepping intensity

Table S15. Adjusted hazard ratios and mortality rates for CVD and Cancer mortality

Table S16. Adjusted hazard ratios for cardiovascular disease mortality across quartiles of stepping intensity

Table S17. Adjusted hazard ratios for cancer mortality across quartiles of stepping intensity

Table S18. Adjusted hazard ratios for steps per day and mortality (8000 vs. 4000 steps/day) in the analytic sample and in complete case analysis

Table S19. Adjusted hazard ratios for stepping intensity and all-cause mortality (Quartile 4 vs. 1) in the analytic sample and in complete case analysis

Figure S1 – Adjusted hazard ratios for all-cause mortality stratified by education and behavioral risk factors (smoking, alcohol consumption, and healthy eating index).

Figure S2 – Adjusted hazard ratios for all-cause mortality stratified by prevalent comorbid conditions.

Figure S3 – Adjusted hazard ratios for all-cause mortality stratified by mobility limitation, self-reported general health, ability to accumulate extended stepping bouts, and length of follow-up.

Figure S4 – Adjusted hazard ratios for all-cause mortality among adults with and without imputed steps.