Abstract

Background

Standardized reporting methods facilitate comparisons between studies. Reporting of data on benefits and harms of treatments in surgical RCTs should support clinical decision‐making. Correct and complete reporting of the outcomes of clinical trials is mandatory to appreciate available evidence and to inform patients properly before asking informed consent.

Methods

RCTs published between January 2005 and January 2017 in 15 leading journals comparing a surgical treatment with any other treatment were reviewed systematically. The CONSORT checklist, including the extension for harms, was used to appraise the publications. Beneficial and harmful treatment outcomes, their definitions and their precision measures were extracted.

Results

Of 1200 RCTs screened, 88 trials were included. For the differences in effect size of beneficial outcomes, 68 per cent of the trials reported a P value only but not a 95 per cent confidence interval. For harmful effects, this was 67 per cent. Only five of the 88 trials (6 per cent) reported a number needed to treat, and no study a number needed to harm. Only 61 per cent of the trials reported on both the beneficial and harmful outcomes of the intervention studied in the same paper.

Conclusion

Despite CONSORT guidelines, current reporting of benefits and harms in surgical trials does not facilitate clear communication of treatment outcomes with patients. Researchers, reviewers and journal editors should ensure proper reporting of treatment benefits and harms in trials.

This systematic review assessed current reporting of the benefits and harms of treatments in surgical trials in leading medical journals. Despite the CONSORT guidelines, reporting of outcomes and effect sizes is still insufficient. This hampers evidence‐based and shared decision‐making.

Inadequate reporting limits information to patients

Antecedentes

Los métodos para la estandarización en la descripción de los resultados facilitan la comparación entre estudios. La toma de decisiones clínicas debe estar respaldada por los resultados que se obtienen en los ensayos clínicos aleatorizados (randomized clinical trials, RCTs) quirúrgicos sobre los efectos beneficiosos y nocivos de los tratamientos. Es obligado que la descripción de los resultados de los ensayos clínicos sea correcta y completa a fin de estimar la evidencia disponible y poder informar a los pacientes de forma adecuada antes de solicitar el consentimiento informado.

Métodos

Se revisaron de forma sistemática los RCTs publicados entre enero de 2005 y enero de 2017 en las 15 revistas principales en los que se comparaba un tratamiento quirúrgico con cualquier otro. Para evaluar las publicaciones, se utilizó la guía de comprobación del CONsolidated Standard of Reporting Trials (CONSORT), haciéndola extensiva también a los efectos nocivos. Se obtuvieron los resultados sobre los efectos beneficiosos y nocivos del tratamiento, sus definiciones y sus medidas de precisión.

Resultados

De 1.200 RCTs seleccionados, se incluyeron 88 ensayos. Para comparar las diferencias de los efectos beneficiosos de los resultados, en el 68% de los ensayos se aportó sólo un valor de la P pero no el intervalo de confianza del 95%. Para efectos nocivos, el porcentaje fue del 67%. En sólo 5 de 88 ensayos (6%) se informó del número de pacientes que es necesario tratar (number needed to treat, NNT), y en ningún estudio se precisó el número de pacientes que es necesario para perjudicar (number needed to harm, NNH). En sólo el 61% de los ensayos se informó de los resultados beneficiosos y nocivos de la intervención analizada en el mismo artículo.

Conclusión

A pesar de la guía CONSORT, la descripción actual de los efectos beneficiosos y nocivos en los ensayos quirúrgicos no permite obtener una clara información del resultado del tratamiento obtenido en los pacientes. Los investigadores, los revisores y los editores de las revistas deben garantizar una descripción adecuada los beneficios y efectos nocivos del tratamiento en los ensayos clínicos.

Introduction

RCTs are considered the best quality evidence for the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions. Surgeons may use this evidence to inform patients to reach informed consent and facilitate shared decision‐making. Surgeons need to communicate clearly the benefits and harms of possible treatments so that patients can understand and weigh these options and express a preference1. Surgeons should therefore be able to rely on clear and complete information about trial results.

Interpreting the results of an RCT remains challenging, however, as reporting outcomes may lack transparency. The CONSORT statement2, 3 was developed in the late 1990s to promote complete, clear and uniform reporting of RCTs. An extended version4, published in 2004, added ten recommendations about harm‐related data. Although widely supported, evidence shows there is still inadequate reporting in RCTs5, 6.

The aim of this systematic review was to assess the reporting of data on the benefits and harms in a recent representative sample of surgical RCTs in leading medical journals, in order to appreciate whether reported outcomes were easily interpretable and applicable in clinical practice when treatment decisions have to be made.

Methods

This review was conducted according to the PRISMA statement7.

Journal Citation Reports was used to identify the top five leading general medical journals and the top ten surgical journals, ranked by impact factors in 2015 (Table 1). A literature search was conducted in the MEDLINE database using PubMed. As only RCTs published within the specific journals were under consideration, the search did not extend to other databases; all the journals were available and traceable through PubMed.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included journals

| Journal | Impact factor 2015 | CONSORT endorsement | No. of included trials | Modified CONSORT score of included trials* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annals of Surgery | 8·6 | Yes | 23 | 47 (24–59) |

| American Journal of Transplantation | 5·7 | Yes | 1 | 40 |

| Journal of the American Medical Association Surgery | 5·7 | Yes | 1 | 57 |

| British Journal of Surgery | 5·6 | Yes | 26 | 50 (31–61) |

| Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery – American Volume | 5·2 | No | 15 | 48 (32–56) |

| Journal of the American College of Surgeons | 4·3 | Yes | 2 | 61 (59–63) |

| New England Journal of Medicine | 59·6 | Yes | 10 | 54 (39–61) |

| Lancet | 44·0 | Yes | 6 | 55 (47–63) |

| Journal of the American Medical Association | 37·7 | Yes | 4 | 52 (38–63) |

Values are median (range).

RCTs including surgical patients and published between January 2005 and January 2017 were eligible. This time interval reflected the publication of the CONSORT extension for harms in 2004. The last search was conducted in January 2017. RCTs that compared a surgical treatment with another surgical or non‐surgical treatment were sought. The search was limited using RCT as publication type along with the following terms, combined using ‘OR’: ‘Surgical Procedures, Operative’[Mesh], ‘excision*’[tiab], ‘postoperation*’[tiab], ‘postoperative’[tiab], ‘resection*’[tiab], and ‘surg*’[tiab].

Study selection

It was planned to include a sample of about 100 RCTs. Based on the screening of a pilot sample of 100 eligible RCTs, eight matched the inclusion criteria. Therefore, 1200 RCTs were selected randomly from the initial set of eligible trials to arrive at the intended 100 RCTs. Studies on patients younger than 18 years, non‐human studies, pilot studies, non‐RCTs, and RCTs in ophthalmology, gynaecology and otorhinolaryngology (being not exclusively surgical specialties) were excluded.

Two reviewers conducted the screening of titles and abstracts of the eligible studies independently. Any disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer. Two reviewers then performed the full‐text screening independently. EndNote X7 (https://endnote.com/), Covidence (The Cochrane Collaboration; https://www.covidence.org/home) and Excel® 2010 (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington, USA) were used during the process of study selection.

Critical appraisal

The revised version of the CONSORT statement and the CONSORT extension for harms were used to evaluate completeness of reporting RCTs2, 4, 8, 9, excluding those unrelated to surgical intervention10. The revised CONSORT statement provides a checklist of 22 items, and the CONSORT extension for harms checklist contains ten additional items. The reviewers discussed both checklists beforehand in order to have the same understanding of each item. This resulted in a combined checklist of 35 items (Table 2). Two reviewers independently scored the items. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion.

Table 2.

Modified CONSORT checklist and adherence in the 88 trials

| Item | Description | No description | Inadequate description | Adequate description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Collected data on harms and benefits stated in title and abstract | 0 (0) | 34 (39) | 54 (61) |

| 2 | Collected data on harms and benefits stated in the introduction | 0 (0) | 62 (71) | 26 (30) |

| 3 | Explicit definition of eligibility criteria for participants | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 87 (99) |

| 4 | Description of settings/locations where data were collected | 1 (1) | 35 (40) | 52 (59) |

| 5 | Details of intervention intended for each group and how/when they were administered | 3 (3) | 6 (7) | 79 (90) |

| 6 | Specific objectives and hypotheses | 0 (0) | 3 (3) | 85 (97) |

| 7 | Clearly defined primary and secondary outcome measures, and (when applicable) any methods used to enhance quality of measurements | 0 (0) | 20 (23) | 68 (77) |

| 8 | List addressed adverse events with definitions for each | 13 (15) | 34 (39) | 41 (47) |

| 9 | Clarify how harms‐related data were collected | 17 (19) | 21 (24) | 50 (57) |

| 10 | How sample size was determined and (when applicable) explanation of any interim analyses and stopping rules | 12 (14) | 0 (0) | 76 (86) |

| 11 | Method used to generate the random allocation sequence, including details of any restriction | 20 (23) | 4 (5) | 64 (73) |

| 12 | Method used to implement the random allocation sequence, clarifying whether sequence was concealed until interventions were assigned | 21 (24) | 3 (3) | 64 (73) |

| 13 | Who generated the allocation sequence, who enrolled participants, who assigned participants to their groups | 53 (60) | 4 (5) | 31 (35) |

| 14 | Details of blinding of subjects | 49 (56) | 0 (0) | 39 (44) |

| 15 | Details of blinding of treatment providers | 55 (63) | 0 (0) | 33 (38) |

| 16 | Details of blinding of assessors | 43 (49) | 1 (1) | 44 (50) |

| 17 | Details of blinding of data analysts | 64 (73) | 0 (0) | 24 (27) |

| 18 | How the success of masking was assessed | 66 (75) | 0 (0) | 22 (25) |

| 19 | Statistical methods used to compare groups for primary outcome(s); methods for additional analyses | 0 (0) | 7 (8) | 81 (92) |

| 20 | Describe plans for presenting and analysing information on harms | 23 (26) | 11 (13) | 54 (61) |

| 21 | Flow chart describing patient numbers at different stages | 22 (25) | 1 (1) | 65 (74) |

| 22 | Flow of participants described in text; describe protocol deviations from study as planned together with reasons | 0 (0) | 24 (27) | 64 (73) |

| 23 | Dates defining the periods of recruitment and follow‐up | 5 (6) | 2 (2) | 81 (92) |

| 24 | Describe withdrawals due to harms and their experiences with allocated treatment | 35 (40) | 12 (14) | 41 (47) |

| 25 | Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of each group | 1 (1) | 6 (7) | 81 (92) |

| 26 | Number of participants in each group included in each analysis; use of intention‐to‐treat principle. State results in absolute numbers when feasible | 27 (31) | 1 (1) | 60 (68) |

| 27 | Provide the denominators for analyses on harms | 11 (13) | 20 (23) | 57 (65) |

| 28 | Complete reporting of results and estimated effect size and its precision | 0 (0) | 15 (17) | 73 (83) |

| 29 | Multiple testing and corrections, indicating those prespecified and those exploratory | 16 (18) | 0 (0) | 72 (82) |

| 30 | All important adverse events or side‐effects in each intervention group/patient | 10 (11) | 21 (24) | 57 (65) |

| 31 | Present the absolute risk per arm and per adverse event type, grade, and seriousness, and present appropriate metrics for recurrent events, continuous variables and scale variables | 11 (13) | 33 (38) | 44 (50) |

| 32 | Describe any subgroup analyses and exploratory analyses for harms | 69 (78) | 2 (2) | 17 (19) |

| 33 | Balanced discussion of own study results | 0 (0) | 34 (39) | 54 (61) |

| 34 | Balanced discussion of generalizability of study results | 78 (89) | 0 (0) | 10 (11) |

| 35 | Balanced discussion in comparison with overall evidence | 0 (0) | 32 (36) | 56 (64) |

Values in parentheses are percentages.

In addition, the number needed to treat (NNT) and number needed to harm (NNH) were scored, as these numbers are considered as clinically useful measures because of their comprehensibility11, 12. The ‘possible impact of funding on results’ was scored as adequate if it was clear from the trial description that it had received unrestricted funding (the sponsor had had no influence on the trial conduct, data collection and analysis, interpretation of the data or writing of the manuscript). Judgement of some items, such as blinding, was given the benefit of the doubt and scored as adequate if this was clear implicitly from the text, even though not stated as such. Similarly, the (in)adequacy of the description of generalizability and comparison with overall evidence was judged with leniency.

Data extraction

A predefined, structured, data extraction form was composed to extract the study characteristics. These were: first author, journal, country of study, year of publication, number of contributing centres, involvement of a statistician or epidemiologist, surgical subspecialty, nature of interventions (surgical versus surgical, or surgical versus non‐surgical), patient characteristics, types of intervention, sample size, follow‐up period, types and total number of outcomes. One reviewer extracted the data, which was checked by a second reviewer independently. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion.

Only data for up to two ‘primary’ benefits (desired outcomes as primary outcomes), up to three ‘secondary’ benefits, up to two ‘primary’ harms (outcomes to be avoided, used as primary outcomes) and up to three ‘secondary’ harms were extracted, as these were considered to be the most important ones. Up to ten outcomes were thus extracted for each trial. Outcomes were defined as primary or secondary according to the description in the methods section of each article. Outcomes were considered beneficial or harmful when they were felt to be desired or to be avoided respectively. If a choice had to be made, the selection of harms and benefits for inclusion depended on clinical relevance, as determined by the reviewers. For example, a more patient‐relevant or patient‐reported outcome measure such as pain was preferred over surgical procedural outcomes such as perioperative pancreatojejunostomy leak. Outcomes, such as wound healing, that were assessed at various time points, were judged as a single outcome.

The various effect measures were recorded, including the accompanying precision measures, difference measures, precision measures of the differences between study arms, whether the outcomes were specifically defined and the time intervals of measurements.

Each extended CONSORT item was scored on a scale from 0 to 2 (0, no description; 1, inadequate description; 2, adequate description). Data were analysed using SPSS® version 22.0 (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA). A descriptive analysis was conducted for all available characteristics of the included journals and RCTs.

Results

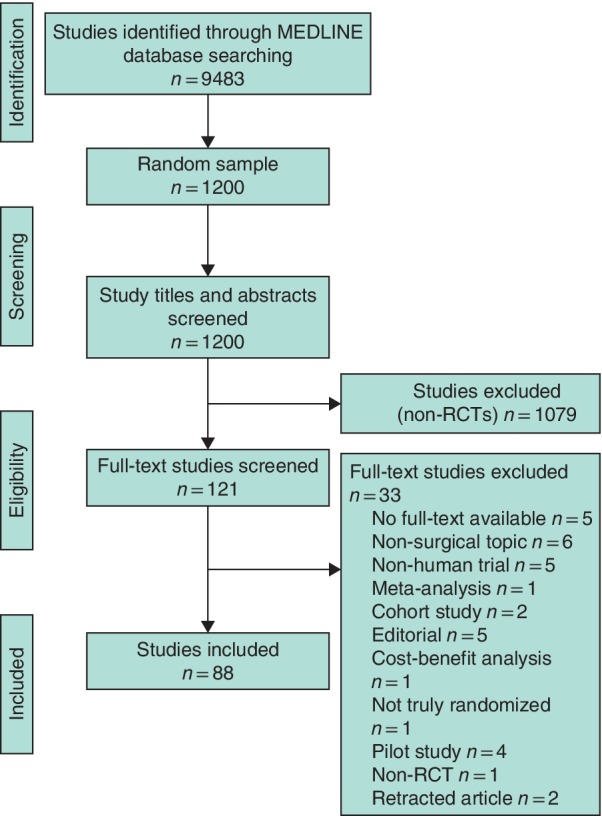

The search resulted in 9483 potentially eligible articles. Titles and abstracts from a random sample of 1200 articles were examined, from which 121 trials from nine different journals were included for full‐text screening. Of these, 88 articles were included in the final sample. An overview of the study selection and inclusion process is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of the study process

Characteristics of included journals

The included 88 trials originated from six surgical and three general medical journals. Their characteristics are shown in Table 1. Only the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery did not explicitly endorse the CONSORT statement guidelines. The surgical and medical journals had median impact factors of 5·7 (range 4·3–8·6) and 44 (37·7–59·6) respectively.

Characteristics of included trials

Table 3 provides an overview of the trial characteristics. Half of the 88 included trials were multicentre studies, the largest of which involved 177 centres. Of the 88 trials, 68 (77 per cent) compared a surgical intervention with another surgical intervention; the remaining 20 (23 per cent) compared a surgical intervention with a non‐surgical intervention.

Table 3.

Characteristics of included RCTs

| No. of trials (n = 88) | |

|---|---|

| No. of centres | 88 (100) |

| Single‐centre | 44 (50) |

| Nature of intervention | |

| Surgical versus surgical | 68 (77) |

| Surgical versus non‐surgical | 20 (23) |

| Type of RCT | |

| Initial | 70 (80) |

| Follow‐up | 18 (20) |

| Follow‐up period (months) | |

| < 1 | 7 (8) |

| 1–5 | 14 (16) |

| 6–12 | 32 (36) |

| > 12 | 34 (39) |

| Missing | 1 (1) |

| Total no. of outcomes | |

| 1–3 | 15 (17) |

| 4–6 | 49 (56) |

| 7–9 | 15 (17) |

| 10–12 | 8 (9) |

| 13 | 1 (1) |

| Measurement outcomes | |

| Primary harm | 54 (61) |

| Primary benefit | 39 (44) |

| Secondary harm | 70 (80) |

| Secondary benefit | 37 (42) |

| Statistician or epidemiologist involvement | |

| Involvement acknowledged | 48 (55) |

| Funding | |

| No funding reported | 17 (19) |

| Possible impact of funding on results | 58 (66) |

| Unrestricted grant stated | 13 (15) |

| Mentioned adherence to CONSORT statement | 5 (6) |

Values in parentheses are percentages.

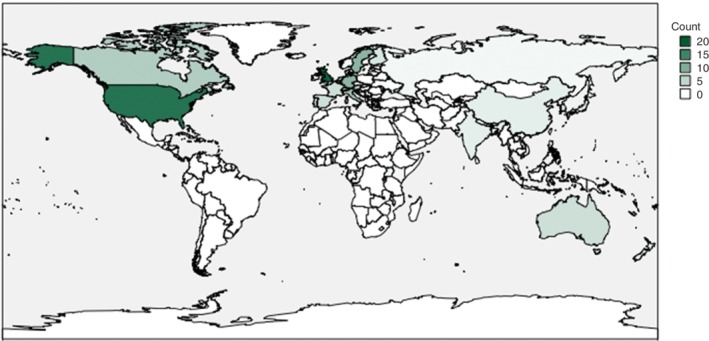

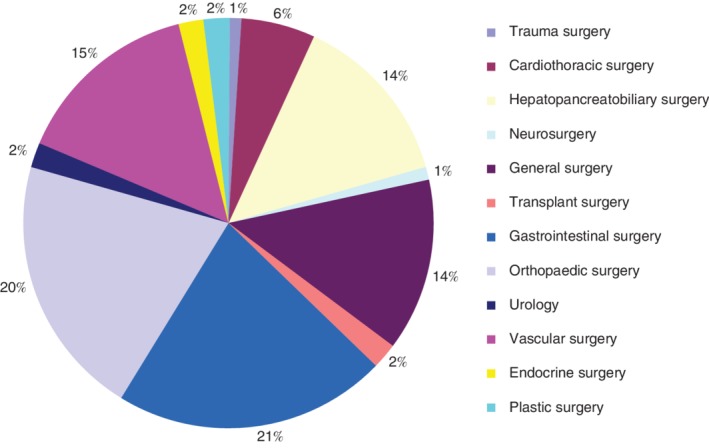

Nearly 60 per cent of the included trials were conducted in Europe (Fig. 2). Fig. 3 presents the subspecialties involved; gastrointestinal surgery (21 per cent), orthopaedic surgery (20 per cent) and vascular surgery (15 per cent) were involved most frequently. Adherence to the CONSORT statement was stated in 6 per cent of studies.

Figure 2.

Overview of the demographic distribution of included RCTs Count indicates the number of articles from each country.

Figure 3.

Overview of the subspecialties of included studies

A median of 6 (range 1–13) outcomes were reported in the included trials. A minority (39 of 88, 44 per cent) reported a primary benefit, in contrast to 54 trials (61 per cent) that stated a primary harm. In more than half of the trials (55 per cent) a statistician or epidemiologist was involved (Table 3).

Table S1 (supporting information) presents detailed information for the included trials.

Reporting in included trials

The overall CONSORT scores of the included studies are shown in Table 1. Median score was 49 (range 24–63) of 70. This score was slightly lower for surgical journals (median score 48 (24–63)) than for the general medical journals (median score 54 (38–63)). CONSORT scores were not significantly higher in more recent publications (median 42 for 2005–2011 versus 42·5 for 2012–2017 articles).

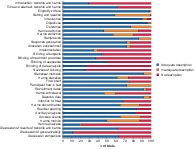

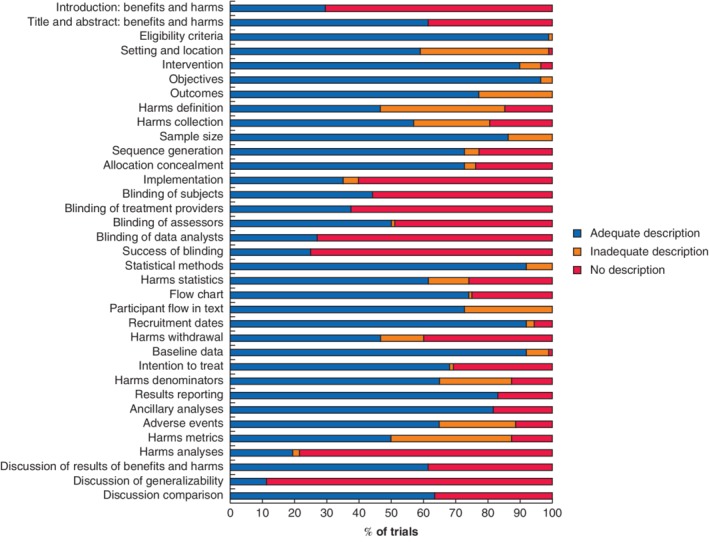

The metrics referring to harmful outcomes were reported inadequately in 33 of 88 studies (38 per cent) (Table 2). Less than half of the studies were scored as adequate regarding the description of loss to follow‐up owing to the occurrence of harm. The description of plans for presenting and analysing information on harms was reported adequately in 61 per cent of the studies. The blinding process was poorly described. For example, only 24 trials (27 per cent) described blinding of the data analyst adequately (Fig. 4). Table 2 shows that generalizability in the discussion section was reported adequately in only 11 per cent of the studies. In contrast, the definition of eligibility criteria was reported adequately in 99 per cent.

Figure 4.

Outcomes of the modified CONSORT checklist

Reporting of outcome measurements

An overview of the most frequently reported primary beneficial and harmful outcomes is given in Table 4. In the 88 studies, a total of 46 primary beneficial outcomes and 63 primary harmful outcomes were reported. Every included study reported at least one discrete outcome. The most frequently reported primary beneficial outcome was a functional outcome measure (15 of 46 reported primary benefits), followed by a measure of the quality of life (10 of 46 benefits). Perioperative characteristics, for example operative blood loss (12 of 63 reported primary harms), complications (12 of 63 harms) and mortality (11 of 63 harms) were the most frequently reported primary harmful outcomes. Overall, 40 of all 280 reported outcomes (14·3 per cent) were not defined clearly. Definitions of primary benefits and harms were lacking in 11 per cent (5 of 46 benefits) and 10 per cent (6 of 63 harms) respectively.

Table 4.

Reporting of primary benefits and harms

| No. of trials | |

|---|---|

| Primary benefits (n = 46) | |

| Functional patient‐reported outcome measure | 15 (33) |

| Quality of life | 10 (22) |

| Survival | 5 (11) |

| Intraoperative results | 4 (9) |

| Technical success | 4 (9) |

| Overall success | 4 (9) |

| Remission | 2 (4) |

| Laboratory results | 1 (2) |

| Weight loss | 1 (2) |

| Primary harms (n = 63) | |

| Perioperative characteristics | 12 (19) |

| Complications | 12 (19) |

| Mortality | 11 (18) |

| Pain | 10 (16) |

| Recurrence | 7 (11) |

| Self‐reported symptoms | 5 (8) |

| Hospital stay | 5 (8) |

| Delay until return to work | 1 (2) |

Values in parentheses are percentages.

Tables 5 and 6 present the effect and precision metrics for the reported benefits and harms. Overall, more trials reported continuous metrics (expressed as means or medians) than dichotomous measures (such as percentages or absolute numbers). In 29 (63 per cent) of the 46 trials in which primary benefits were described, these were continuous outcomes. Only eight (8 per cent) of the 99 primary and secondary beneficial outcomes were reported as percentages with the corresponding absolute numbers, and 13 per cent (13 of 99) were reported as percentages only (Table 5).

Table 5.

Frequency of reported outcomes and precision metrics on benefits of trials

| Primary benefit 1 (n = 39) | Primary benefit 2 (n = 7) | Secondary benefit 1 (n = 37) | Secondary benefit 2 (n = 13) | Secondary benefit 3 (n = 3) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect measure | |||||

| Missing | 1 (3) | – | – | – | – |

| Mean | 19 (49) | 5 (71) | 21 (57) | 9 (69) | 1 (33) |

| Median | 4 (10) | 1 (14) | 7 (19) | 2 (15) | 2 (67) |

| Percentage | 6 (15) | 1 (14) | 6 (16) | – | – |

| Absolute number | 2 (5) | – | 2 (5) | 1 (8) | – |

| Absolute number + percentage | 6 (15) | – | 1 (3) | 1 (8) | – |

| Mean and median | 1 (3) | – | – | – | |

| Precision measure of effect | |||||

| Missing | 13 (33) | – | 10 (27) | 4 (31) | – |

| P value | 1 (3) | 1 (14) | – | – | – |

| 95 per cent c.i. | 6 (15) | – | 9 (24) | 3 (23) | – |

| s.d. | 15 (39) | 5 (71) | 12 (32) | 4 (31) | 1 (33) |

| i.q.r. | 2 (5) | 1 (14) | 4 (11) | 2 (15) | 2 (67) |

| s.d. and i.q.r. | 1 (3) | – | – | – | – |

| Range | 1 (3) | – | 2 (5) | – | – |

| Difference measure | |||||

| Missing | 3 (8) | – | 1 (3) | 1 (8) | – |

| Risk ratio | 1 (3) | – | – | – | – |

| Hazard ratio | 4 (10) | 1 (14) | 1 (3) | – | – |

| Odds ratio | 2 (5) | – | 1 (3) | – | – |

| Difference in mean | 16 (41) | 4 (57) | 18 (49) | 6 (46) | 1 (33) |

| Difference in percentage | 3 (8) | – | 5 (14) | – | 2 (67) |

| Difference in median | 4 (10) | 1 (14) | 7 (19) | 2 (15) | – |

| Difference in absolute number | – | – | 2 (5) | 1 (8) | – |

| General effect size | 2 (5) | 1 (14) | 1 (3) | 2 (15) | – |

| Risk difference | 2 (5) | – | 1 (3) | 1 (8) | – |

| Relative risk and number needed to treat | 1 (3) | – | – | – | |

| Difference in mean and in median | 1 (3) | – | – | – | – |

| Precision measure of difference | |||||

| P value | 23 (59) | 5 (71) | 27 (73) | 9 (69) | 3 (100) |

| 95 per cent c.i. | 1 (3) | 1 (14) | 3 (8) | 1 (8) | – |

| P value and 95 per cent c.i. | 14 (36) | 1 (14) | 7 (19) | 3 (23) | – |

| 90 per cent c.i. | 1 (3) | – | – | – | – |

Values in parentheses are percentages.

Table 6.

Reporting outcomes and precision metrics on harms

| Primary harm 1 (n = 54) | Primary harm 2 (n = 9) | Secondary harm 1 (n = 70) | Secondary harm 2 (n = 33) | Secondary harm 3 (n = 15) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect measure | |||||

| Missing | 1 (2) | – | – | 2 (6) | – |

| Mean | 19 (35) | 4 (44) | 12 (17) | 8 (24) | 2 (13) |

| Median | 7 (13) | – | 7 (10) | 3 (9) | 2 (13) |

| Percentage | 8 (15) | 1 (11) | 7 (10) | 5 (15) | 2 (13) |

| Absolute number | 3 (6) | – | 12 (17) | 7 (21) | 3 (20) |

| Absolute number + percentage | 15 (28) | 3 (33) | 30 (43) | 8 (24) | 5 (33) |

| Cumulative incidence | 1 (2) | 1 (11) | – | – | – |

| Absolute number + mean | – | – | 1 (1) | – | – |

| Ratio | – | – | 1 (1) | – | – |

| Rate/100 patient‐years | – | – | – | – | 1 (7) |

| Precision measure of effect | – | ||||

| Missing | 23 (43) | 4 (44) | 46 (66) | 21 (64) | 10 (67) |

| P value | 1 (2) | – | 1 (1) | 1 (3) | 1 (7) |

| 95 per cent c.i. | 6 (11) | 1 (11) | 6 (9) | 1 (3) | ‐ |

| s.d. | 13 (24) | 4 (44) | 9 (13) | 6 (18) | 1 (13) |

| i.q.r. | 1 (2) | – | 2 (3) | – | 1 (7) |

| Range | 5 (9) | – | 4 (6) | 4 (12) | 1 (7) |

| P value and range | 1 (2) | – | 1 (1) | – | – |

| s.e.m. | 3 (6) | – | 1 (1) | – | – |

| Difference measure | |||||

| Missing | 4 (7) | 1 (11) | 19 (27) | 10 (30) | 4 (27) |

| Risk ratio | 4 (7) | 1 (11) | 1 (1) | – | – |

| Hazard ratio | 7 (13) | – | 2 (3) | 1 (3) | – |

| Odds ratio | 4 (7) | 1 (11) | 2 (3) | 1 (3) | – |

| Difference in mean | 18 (33) | 4 (44) | 13 (19) | 8 (24) | 2 (13) |

| Difference in percentage | 7 (13) | – | 26 (37) | 9 (27) | 6 (40) |

| Difference in median | 7 (13) | – | 5 (7) | 3 (9) | 2 (13) |

| Risk difference | 3 (6) | 1 (11) | 1 (1) | 1 (3) | – |

| Difference in cumulative incidence | – | 1 (11) | – | – | – |

| Effect size | – | – | 1 (1) | – | – |

| Difference in rate/100 patient‐years | – | – | – | – | 1 (7) |

| Precision measure of difference | |||||

| Missing | 3 (6) | 1 (11) | 11 (16) | 5 (15) | 2 (13) |

| P value | 29 (54) | 4 (44) | 51 (73) | 25 (76) | 13 (87) |

| 95 per cent c.i. | 6 (12) | – | 1 (1) | – | – |

| P value and 95 per cent c.i. | 14 (26) | 4 (44) | 6 (9) | 3 (9) | – |

| 90 and 95 per cent c.i. | 1 (2) | – | 1 (1) | – | – |

| P value, 95 per cent c.i. and number needed to treat | 1 (2) | – | – | – | – |

Values in parentheses are percentages.

A total of 63 primary and 118 secondary harms were reported. In 48 per cent of the trials the primary harm was a continuous outcome. Of the 181 primary and secondary harmful outcomes, 61 (33·7 per cent) were reported as percentages with the corresponding absolute numbers, and 23 (12·7 per cent) were reported as percentages only (Table 6).

The precision of the observed differences was usually reported as a P value only, and not as a 95 per cent confidence interval. For the differences in effect size of beneficial outcomes, 68 per cent of the trials reported a P value only, and not a 95 per cent confidence interval. For harmful effects, this was 67 per cent.

Only five of the 88 studies (6 per cent) mentioned a NNT or NNH. However, a NNT or NNH could be calculated based on the absolute numbers provided for eight of the 46 documented primary benefit outcomes, and for two of the 63 reported primary harm outcomes. Some 39 per cent of the trials did not report on both the beneficial and harmful outcomes of the intervention studied in the same paper.

Discussion

This systematic review analysed the reporting of data from surgical RCTs published within the past two decades in leading surgical and medical journals. The CONSORT statements have been designed to optimize the reporting of (benefits and harms in) trials, but this review found that current publications still show suboptimal reporting of discrete data. Previous systematic reviews have addressed the suboptimal level of adherence to the CONSORT statement in publications in surgical journals13. The present review adds to this in terms of deficiencies in how data on benefits and harms are reported. Few of these outcomes were described as an adequate and easily interpretable effect estimate or difference measure. Measures of precision such as confidence intervals were missing in most trial reports. In combination with effect size, precision measures help the reader to appreciate whether or not a finding is clinically relevant. Besides effect and precision measures, benefits and harms should be defined clearly so that healthcare providers can communicate these with patients.

Most trials included in this review provided P values only, which express statistical significance14 but do not communicate unequivocally the amount of statistical uncertainty that surrounds the available effect estimate. P values can make it more difficult to appreciate results, with risks of misinterpretation and errors in assessing the applicability of an intervention in clinical practice15.

More trials in the present review reported on harms than on benefits as primary outcomes. This finding is in contrast with a previous review that showed poor reporting of harms16. Possibly, trials of surgical interventions pay more (but still insufficient) attention to harmful effects, given the invasive nature of the intervention.

The number of patients who need to be treated to achieve one additional beneficial event, the NNT, has become a well known measure of treatment benefit11. When treatment decisions are to be made, particularly in the surgical outpatient clinic, these parameters may help healthcare providers explain to their patients the expected benefits and risks of interventions. Back in 2001, the CONSORT statement argued that the NNT could be helpful to express the results of an RCT.

Studies assessing reporting quality before the extended CONSORT statement was issued17, 18 showed similar shortcomings. Unfortunately, the publications evaluated here still suffered from the same shortcomings, despite the fact that leading medical journals have supported the recommendations for standards of reporting11, 17, 19, or even extended them20. Generalizability of the results was described poorly in most trials. This aspect is crucial for healthcare providers to appreciate whether the results of a trial are relevant and applicable to their own patient population.

The present review has limitations. Of the 88 trials included in the analysis, 18 were follow‐up studies, in which some primary reports of trial results were not included. As these follow‐up studies often did not describe further details about trial designs and methods, this might have resulted in a lower modified CONSORT score in comparison with the initial RCTs. However, when reporting follow‐up data of a study, authors should make clear the main points of the methodology and outcomes of the conducted RCT. The random sample did not yield studies from all initially selected journals, although this seems unlikely to have influenced the findings, as all studies were published in leading journals, nearly all of which endorsed the CONSORT statement. It was, however, unclear in which year the journals in the survey adopted this requirement in their instructions to authors. This study was limited to studies of surgical versus surgical versus non‐surgical interventions. Surgical trials reporting on non‐surgical interventions alone might show higher CONSORT scores, because non‐surgical (mostly drug) treatments tend to be better scrutinized and monitored before reporting the outcomes. The classification of outcomes as beneficial or harmful was sometimes ambiguous. For example, pain is generally interpreted as harmful and was therefore reported as ‘harm’, but in one study21 reduction in pain was scored as a ‘benefit’.

The CONSORT statement, along with the extension for harms, provides guidelines that should ensure high reporting quality for RCTs. Current trials, however, reported in leading surgical and medical journals still fail to describe reported benefits and harms in surgical RCTs correctly, despite the fact that the CONSORT statement is supported widely. Interpretation of the provided evidence remains difficult and susceptible to interpretation bias, which, in turn, impedes adoption. Authors, editors, statisticians and peer reviewers should emphasize adherence to CONSORT guidelines to facilitate evidence‐based clinical decision‐making.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Table S1. Detailed characteristics of included studies

Funding information

No funding

References

- 1. Stiggelbout AM, Van der Weijden T, De Wit MP, Frosch D, Legare F, Montori VM et al Shared decision making: really putting patients at the centre of healthcare. BMJ 2012; 344: e256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Begg C, Cho M, Eastwood S, Horton R, Moher D, Olkin I et al Improving the quality of reporting of randomized controlled trials. The CONSORT statement. JAMA 1996; 276: 637–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Freemantle N, Mason JM, Haines A, Eccles MP. An important step toward evidence‐based health care. Consolidated standards of reporting trials. Ann Intern Med 1997; 126: 81–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ioannidis JP, Evans SJ, Gotzsche PC, O'Neill RT, Altman DG, Schulz K et al; CONSORT Group. Better reporting of harms in randomized trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. Ann Intern Med 2004; 141: 781–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hopewell S, Dutton S, Yu LM, Chan AW, Altman DG. The quality of reports of randomised trials in 2000 and 2006: comparative study of articles indexed in PubMed. BMJ 2010; 340: c723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wang JL, Sun TT, Lin YW, Lu R, Fang JY. Methodological reporting of randomized controlled trials in major hepato‐gastroenterology journals in 2008 and 1998: a comparative study. BMC Med Res Methodol 2011; 11: 110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP et al The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta‐analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med 2009; 6: e1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Altman DG, Schulz KF, Moher D, Egger M, Davidoff F, Elbourne D et al; CONSORT GROUP (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials). The revised CONSORT statement for reporting randomized trials: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 2001; 134: 663–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG. The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel‐group randomised trials. Lancet 2001; 357: 1191–1194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Boutron I, Moher D, Altman DG, Schulz KF, Ravaud P; CONSORT Group . Extending the CONSORT statement to randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatment: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 2008; 148: 295–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cook RJ, Sackett DL. The number needed to treat: a clinically useful measure of treatment effect. BMJ 1995; 310: 452–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tramèr MR, Walder B. Number needed to treat (or harm). World J Surg 2005; 29: 576–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Speich B, Mc Cord KA, Agarwal A, Gloy V, Gryaznov D, Moffa G et al Reporting quality of journal abstracts for surgical randomized controlled trials before and after the implementation of the CONSORT extension for abstracts. World J Surg 2019; 43: 2371–2378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nuzzo R. Statistical errors: P values, the ‘gold standard’ of statistical validity, are not as reliable as many scientists assume. Nature 2014; 506: 150–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Baker M. Statisticians issue warning over misuse of P values. Nature 2016; 531: 151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hodkinson A, Kirkham JJ, Tudur‐Smith C, Gamble C. Reporting of harms data in RCTs: a systematic review of empirical assessments against the CONSORT harms extension. BMJ Open 2013; 3: e003436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nuovo J, Melnikow J, Chang D. Reporting number needed to treat and absolute risk reduction in randomized controlled trials. JAMA 2002; 287: 2813–2814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hildebrandt M, Vervolgyi E, Bender R. Calculation of NNTs in RCTs with time‐to‐event outcomes: a literature review. BMC Med Res Methodol 2009; 9: 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Furukawa TA. From effect size into number needed to treat. Lancet 1991; 353: 1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Legemate DA, Koelemay MJ, Ubbink DT. Number unnecessarily treated in relation to harm: a concept physicians and patients need to understand. Ann Surg 2016; 263: 855–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bingener J, Skaran P, McConico A, Novotny P, Wettstein P, Sletten DM et al. A double‐blinded randomized trial to compare the effectiveness of minimally invasive procedures using patient‐reported outcomes. J Am Coll Surg 2015; 221: 111–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Detailed characteristics of included studies