Abstract

Background

Effects of postmastectomy radiotherapy (PMRT) on autologous breast reconstruction (BRR) are controversial regarding surgical complications, cosmetic appearance and quality of life (QOL). This systematic review evaluated these outcomes after abdominal free flap reconstruction in patients undergoing postoperative adjuvant radiotherapy (PMRT), preoperative radiotherapy (neoadjuvant radiotherapy) and no radiotherapy, aiming to establish evidence‐based optimal timings for radiotherapy and BRR to guide contemporary management.

Methods

The study was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42017077945). Embase, MEDLINE, Google Scholar, CENTRAL, Science Citation Index and ClinicalTrials.gov were searched (January 2000 to August 2018). Study quality and risk of bias were assessed using GRADE and Cochrane's ROBINS‐I respectively.

Results

Some 12 studies were identified, involving 1756 patients (350 PMRT, 683 no radiotherapy and 723 neoadjuvant radiotherapy), with a mean follow‐up of 27·1 (range 12·0–54·0) months for those having PMRT, 16·8 (1·0–50·3) months for neoadjuvant radiotherapy, and 18·3 (1·0–48·7) months for no radiotherapy. Three prospective and nine retrospective cohorts were included. There were no randomized studies. Five comparative radiotherapy studies evaluated PMRT and four assessed neoadjuvant radiotherapy. Studies were of low quality, with moderate to serious risk of bias. Severe complications were similar between the groups: PMRT versus no radiotherapy (92 versus 141 patients respectively; odds ratio (OR) 2·35, 95 per cent c.i. 0·63 to 8·81, P = 0·200); neoadjuvant radiotherapy versus no radiotherapy (180 versus 392 patients; OR 1·24, 0·76 to 2·04, P = 0·390); and combined PMRT plus neoadjuvant radiotherapy versus no radiotherapy (272 versus 453 patients; OR 1·38, 0·83 to 2·32, P = 0·220). QOL and cosmetic studies used inconsistent methodologies.

Conclusion

Evidence is conflicting and study quality was poor, limiting recommendations for the timing of autologous BRR and radiotherapy. The impact of PMRT and neoadjuvant radiotherapy appeared to be similar.

A PROSPERO‐registered, PRISMA‐compliant meta‐analysis was conducted on clinical and patient‐reported outcomes of immediate versus delayed abdominal‐based free‐flap breast reconstruction, in the context of radiotherapy. Current evidence is conflicting, with no consistent recommendations for autologous breast reconstruction and radiotherapy. High‐quality evidence is mandatory for national guidelines and to optimize informed consent.

Better quality evidence still needed.

Antecedentes

En pacientes sometidas a una reconstrucción mamaria (breast reconstruction, BRR) con tejido autólogo se discuten los efectos de la radioterapia post‐mastectomía (post‐mastectomy radiotherapy, PMRT) en las complicaciones quirúrgicas, el resultado estético y la calidad de vida (quality of life, QOL). Esta revisión sistemática evaluó dichos resultados tras una reconstrucción mamaria con un colgajo libre abdominal en pacientes tratadas con PMRT, radioterapia preoperatoria (Neo RT) y sin radioterapia (RT), a fin de establecer los momentos óptimos de la RT y BRR basados en la evidencia, como guía del tratamiento actual.

Métodos

El estudio se registró en la base de datos PROSPERO (CRD42017077945). Se realizaron búsquedas en Embase, MEDLINE, Google Scholar, CENTRAL, Science Citation Index y Clinicaltrials.gov (enero de 2000‐agosto de 2018). La calidad de los estudios y el riesgo de sesgo se evaluaron mediante las herramientas GRADE y ROBINS‐I de la Cochrane, respectivamente.

Resultados

Se identificaron 12 estudios que incluían 1.756 pacientes (350 PMRT, 683 sin RT y 723 Neo RT), con una mediana de seguimiento de 27,1 meses (rango 12,0‐54,0) para PMRT, 16,8 meses (1,0‐50,3) para Neo RT y 18,3 meses (1,0‐48,7) para sin RT. Se incluyeron tres cohortes prospectivas y nueve retrospectivas. No hubo estudios aleatorizados. Los estudios comparativos de RT evaluaron la PMRT (n = 5) y la Neo RT (n = 4). Todos los estudios fueron de baja calidad, con riesgos de sesgo de moderados a graves. Las complicaciones graves fueron similares entre los grupos: PMRT (n = 92) versus sin RT (n = 141), razón de oportunidades (odds ratio, OR) 2,35, i.c. del 95% 0,63‐8,81), P = 0,200; Neo RT (n = 180) versus no RT (n = 392) (OR 1,24, i.c. del 95% 0,76‐2,04), P = 0,390; o RT combinada (PMRT y neoadyuvante) (n = 272) versus no RT (n = 453) (OR 1,38, i.c. del 95% 0,83‐2,32), P = 0,220. Los estudios de calidad de vida y de resultados estéticos utilizaron metodologías poco consistentes.

Conclusión

La evidencia es contradictoria y la calidad de los estudios muy pobre, hechos que limitan las posibles recomendaciones para el momento de la BRR con tejido autólogo y la RT. El impacto de la PMRT o la Neo RT parecen ser similares.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the commonest malignancy and leading cause of cancer‐related mortality in women1, 2. Breast‐conserving surgery (BCS) with radiotherapy or mastectomy are recommended treatments, with comparable oncological outcomes3, 4. Autologous abdominal‐based free flap and implant‐based procedures are the approaches used most frequently in immediate breast reconstruction (BRR)5. Autologous BRR has the inherent advantage of using the patient's own tissues, taken from a different part of the body where there is excess fat and skin, to restore breast volume and appearance after mastectomy. Various donor sites can be used, most commonly the abdomen6.

Adjuvant locoregional postmastectomy radiotherapy (PMRT) of the chest wall, and potentially of the regional lymph nodes, has been indicated historically for locally advanced disease7, 8. These indications increased following the Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group9 meta‐analyses, which showed significantly improved disease‐free and overall survival after PMRT and regional node irradiation in women at intermediate risk (tumour size 50 mm or less and 1–3 positive lymph nodes)10. Newly proposed US guidelines11 emphasize the need to consider the lower recurrence rates associated with contemporary practice and the benefits of systemic therapy12. Current recommendations for PMRT in the intermediate‐risk group remain controversial, pending the results of the SUPREMO (Selective Use of Postoperative Radiotherapy aftEr MastectOmy) trial, evaluating chest wall and/or axillary radiotherapy13, 14.

Adjuvant radiotherapy (PMRT) may have deleterious effects on breast cosmetic outcomes, quality of life (QOL) and surgical complications after immediate BRR15. Previous studies evaluating the impact of PMRT on types of immediate BRR showed its potential feasibility in this setting, with lower morbidity rates compared with those of implant‐based procedures5, 16, 17, 18. Surprisingly, the rapid adoption of immediate implant‐based reconstruction in about 70 per cent of women, compared with 34 per cent of autologous procedures when PMRT is recommended, may be influenced by surgeon and patient preferences, regardless of current evidence15, 17, 19.

Increasing recommendations for PMRT and immediate BRR have prompted a need to consider their optimal sequence. Previous systematic reviews have not provided clarity concerning the choice between immediate and delayed BRR9. Despite this, immediate autologous BRR is commonly recommended in the setting of PMRT, given the potential long‐term benefits on patients' QOL and breast cosmetic satisfaction20, 21. Currently, immediate autologous BRR and PMRT recommendations are variable22, 23. A systematic review24 in 2011 showed methodological variations in the definitions of surgical complications, precluding interstudy comparisons.

Complications of autologous breast reconstruction with PMRT include: poor wound‐healing, flap‐related fat necrosis, fibrosis and contracture, which reduce breast volume5. Surgical complications contribute variably to decreased patient satisfaction and impaired cosmetic outcomes5. A standardized core set of outcomes for BRR has been proposed25 involving a range of complications, including flap‐related complications and the need for further unplanned surgery. The BRR core outcome set has yet to recommend a standardized measurement tool for evaluating surgical complications. Most surgeons use the Clavien–Dindo classification (CDC)26. Patient‐reported QOL outcomes using validated BRR questionnaires, such as the BREAST‐Q and the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality‐of‐Life Questionnaire (QLQ)‐BRECON23, are recommended to evaluate comparative effectiveness20, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32.

This systematic review aimed to evaluate the quality and strengths of the current evidence regarding surgical complications in autologous abdominal flaps in the context of the receipt and timing of radiotherapy related to PMRT5, 6 and, less commonly, neoadjuvant radiotherapy, generally administered before skin‐sparing mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction33, including assessment of QOL34.

Methods

The protocol was registered and published on the Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews PROSPERO (CRD42017077945)35. The authors adhered to the PRISMA statement36.

Search strategies

A comprehensive search of the MEDLINE (Ovid SP), Embase (Ovid SP), Google Scholar, Cochrane Controlled Register of Trials (CENTRAL), Science citation index databases and http://clinicaltrials.gov (January 2000 to August 2018) was conducted, identifying the relevant studies. Combinations of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms and free text were used, including Boolean logical operators for the search strategy. References of included articles were also screened for their relevance. The example of an Embase (Ovid SP) search strategy was adopted for other databases (Appendix S1, supporting information).

Identification and selection of studies

Database‐related searches were entered into an EndNote™ X8 library (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA). Study screening was performed independently in two stages by two investigators using prespecified screening criteria.

In stage 1, two authors independently screened titles and abstracts. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus with the senior author. Remaining doubts regarding an article resulted in a review of the complete publication.

In stage 2, full‐text studies from stage 1 were screened independently for their eligibility by two reviewers. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus with a third reviewer. Authors of eligible studies were contacted (via e‐mail) to reconcile any methodological issues or to provide more detailed information on data for individual types of autologous flap.

Study design

All primary human studies evaluating surgical complications for autologous free flap (microvascular) abdominal BRR in breast cancer and types of radiotherapy (PMRT, neoadjuvant and no radiotherapy) were included. Outcomes also included patient‐reported QOL and cosmetic assessments. Radiotherapy groups were compared with a control or no radiotherapy group in comparative studies, compatible with immediate and delayed BRR. Commonly performed autologous abdominal flaps included: deep inferior epigastric perforator (DIEP), transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous (TRAM) and the superficial inferior epigastric artery perforator (SIEA)6.

Inclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were: women aged at least 18 years with a diagnosis of invasive breast cancer (TNM categories: T0–3, N1–3, Mx, M0), undergoing immediate or delayed abdominal autologous BRR using free flaps (DIEP, TRAM or SIEA) who received adjuvant radiotherapy (PMRT), neoadjuvant radiotherapy or no radiotherapy.

Clinical studies that involved at least 50 patients were included (RCTs, prospective and retrospective comparative observational studies, and case series).

Exclusion criteria

Review articles, conference abstracts, simulation studies and clinical studies in non‐human subjects were not included, along with studies involving patients who received segmental or partial mastectomy, technical descriptions of operative repair with no outcome measures, BRR unrelated to breast cancer, implant‐based reconstructions and other non‐abdominal autologous flaps.

Risk of bias and quality of studies

Cochrane's ROBINS‐I (Risk Of Bias In Non‐randomised Studies – of Interventions) tool was used for comparative studies37. This comprises seven domains from which the risk of bias may be ascertained to produce an overall risk‐of‐bias score37. The Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations (GRADE) tool38 was used to evaluate the methodological quality of individual studies.

Study outcomes

Primary outcomes were surgical complications including: Clavien–Dindo classification (CDC) grades II and III26; partial flap loss; total flap loss; fat necrosis (CDC grades, when reported)39; number(s) of unplanned reoperations for surgical complications (excluding cosmetic revisions); and number(s) of total complications. A surgical complication was defined as an adverse, postoperative, surgery‐related event that required additional treatment16. If CDC grades were not defined, the complications reported by the included studies were graded retrospectively according to the CDC by two independent authors; any discrepancy was discussed and agreed with the senior author.

Secondary outcomes were assessed using patient‐reported QOL‐validated questionnaires (COnsensus‐based Standards for the Selection of health Measurement INstruments (COSMIN)40, 41, Breast Questionnaire (BREAST‐Q), the EORTC Quality‐of‐Life Questionnaire (QLQ) – Breast Cancer 2342, the Quality‐of‐Life Cancer Generic Questionnaire (QLQ‐C30)43, the Numerical Pain Rating Scale (NPRS)44, 45, the Patient‐Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System – Profile 29 (PROMIS‐29)46, the McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ)47, the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD‐7)48 and the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ‐9)49), as well as assessment of cosmetic outcomes using independent panel or self assessments of medical photographs, and surface imaging using the Vectra® XT three‐dimensional system50 (Canfield Scientific, Parsippany, New Jersey, USA).

Data extraction, collection and management

Two authors independently extracted data from full‐text articles using a standard data form. Any discrepancies were resolved by consensus with a third reviewer. Reporting authors of original articles were contacted on up to two occasions relating to missing data or where additional information was required.

Data extraction included: first author, year of publication, study design, study setting, number of centres, duration of follow‐up, study population and participant demographics (mean age, BMI, smoking, co‐morbidities).

Surgical complications were recorded using CDC: grades II–III26. Two authors reviewed eligible studies and classified each complication according to the CDC26 if unreported.

QOL and cosmetic outcomes were listed.

Statistical analysis

When two or more studies reported outcome data, these were pooled using Review Manager 5.3 software (The Cochrane Collaboration, The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark). Odds ratios with 95 per cent confidence intervals were used to evaluate dichotomous outcomes (surgical complications). Standard mean differences (with 95 per cent c.i.) were used for continuous outcomes between treatment groups. Rates of each complication (fat necrosis, partial and total flap loss, infection and wound complications (dehiscence and delayed wound healing)) were compared for PMRT (versus no radiotherapy) and neoadjuvant radiotherapy (versus no radiotherapy). Data were also pooled to provide an overall summary measure of combined radiotherapy (adjuvant and neoadjuvant) compared with no radiotherapy.

Heterogeneity between studies51 was assessed in Review Manager 5.3 using the Higgins and Thompson I 2 statistic52. Levels of heterogeneity were defined as: low (I 2 less than 50 per cent), moderate (I 2 = 50–80 per cent) and high (I 2 above 80 per cent). A random‐effects model was used for cohorts with heterogeneity (I 2 above 50 per cent)53. As heterogeneity was generally moderate or high, and outcome measures differed between studies, these were combined using the DerSimonian and Laird random‐effects model. Results of meta‐analyses are shown as forest plots. A sensitivity analysis was performed where possible, to evaluate whether outcomes differed when restricting the analysis exclusively to high‐quality studies.

Clinically meaningful differences in QOL items/questions or domain scores may vary depending on response shift, that is a change in the meaning of QOL scores over time54. This is relevant in longitudinal studies and may influence clinical significance, defined as greater than 5‐point score differences for EORTC QLQ‐C30 and QLQ‐BR2342, 43, 54. Clinically meaningful differences are currently being evaluated using a number of methods such as qualitative interviews and using predefined clinical anchors55. Clinically meaningful differences in QOL should be differentiated from statistical significance55. BREAST‐Q findings have been compared with large population‐derived normative data, facilitating clinically meaningful interpretation of data56, 57.

Results

A total of 697 studies were identified. Of these, 12 studies58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69 (including 1756 patients) evaluated adjuvant radiotherapy (350 patients), neoadjuvant radiotherapy (723) and no radiotherapy (683) (Fig. 1). There were three prospective study designs59, 60, 62 and nine that were retrospective58, 61, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, but no RCTs. There were two multicentre (1 prospective62 and 1 retrospective66) and ten single‐centre studies (2 prospective59, 60 and 8 retrospective58, 61, 63, 64, 65, 67, 68, 69) (Table 1). Study quality (GRADE) was low in eight studies58, 59, 61, 63, 64, 65, 66, 68 and moderate in the other four60, 62, 67, 69, with an overall high risk of bias. A summary of baseline characteristics, including numbers of centres, country of origin, dates, patient numbers, breast cancer pathology and adjuvant medical treatments in comparative adjuvant and neoadjuvant radiotherapy groups, including non‐comparative studies, is provided in Table S1 (supporting information).

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram for the review RT, radiotherapy; BRR, breast reconstruction.

Table 1.

Study summaries: comparative adjuvant or neoadjuvant radiotherapy in autologous breast reconstruction, and non‐comparative studies (adjuvant radiotherapy or neoadjuvant radiotherapy only)

| Reference | Years | Country | No. of centres | Type of BRR flap | Overall follow‐up (months) | Group differences in baseline characteristics¶ | RT dose and regimen |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baumann et al.69, ‡ | 2005–2009 | USA | 1 | msTRAM; DIEP; SIEA | 11* | n.a. | Total 60 Gy; missing details |

| Billig et al.62, § | 2012–2017 | USA and Canada | 11 | TRAM; DIEP; SIEA | 24 | Adjuvant RT: more non‐Hispanic patients (P = 0·001), bilateral BRR (P = 0·002), DIEP/SIEA (P < 0·001), adjuvant chemotherapy (P < 0·001); less TRAM (P < 0·001)# | Total 50·4 Gy over 4 weeks, daily (28 fractions of 1·8 Gy) |

| Chatterjee et al.59, § | 1995–2005 | UK | 1 | DIEP | 42 (12–120)† | Adjuvant RT: more IDC (P = 0·02), LVI (P = 0·044), positive axillary LN (P < 0·001) | Total 45 Gy over 4 weeks (20 fractions) |

| Cooke et al.60, § | 2012–2015 | Canada | 1 | DIEP; SIEA | 12 | Adjuvant RT: higher TNM staging, positive LN, more chemotherapy (P values not provided) | Total 50/50·4 Gy over 4 weeks, daily (25 fractions of 2 Gy/28 fractions of 1·8 Gy) |

| Huang et al.63, ‡ | 1997–2001 | Taiwan | 1 | TRAM | 40 (24–74)† | n.a. | Total 50 Gy; missing details |

| Levine et al.67, ‡ | 1999–2011 | USA | 1 | msTRAM; DIEP; SIEA | 22·7* | n.a. | Missing details |

| Modarressi et al.64, ‡ | 2007–2013 | Switzerland | 1 | DIEP | 1 | n.a. | Missing details |

| Mull et al.65, ‡ | 2003–2014 | USA | 1 | msTRAM; TRAM; DIEP | 1 | Neoadjuvant RT: more chemotherapy (P < 0·01), higher TNM staging (P < 0·01); less hypertension/CAD (P = 0·03) | Missing details |

| O'Connell et al.58, ‡ | 2009–2014 | UK | 1 | DIEP | 44·3 (i.q.r. 31·1–56·4)† | Adjuvant and neoadjuvant RT: more chemotherapy and endocrine therapy as less DCIS/less advanced invasive disease (P values not provided) | Total 40 Gy over 3 weeks (15 fractions) |

| Peeters et al.66, ‡ | 1997–2003 | Belgium | 2 | DIEP | ≥ 12 | n.a. | Total 50 Gy; missing details |

| Rogers and Allen61, ‡ | 1994–1999 | USA | 1 | DIEP | 18·7* | n.a. | Total 50·5 Gy over 6·5 weeks (missing details) |

| Temple et al.68, ‡ | 1990–2001 | USA | 1 | TRAM | ≥ 12 | n.a. | Total 58 Gy; missing details |

Values are *mean and †median (range), unless indicated otherwise. ‡Retrospective study; §prospective study. ¶Radiotherapy (RT) versus no RT, except #group difference values are for adjuvant RT versus neoadjuvant RT. BRR, breast reconstruction; (ms)TRAM, (muscle‐sparing) transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous; DIEP, deep inferior epigastric artery perforator; SIEA, superficial inferior epigastric artery perforator; IDC, invasive ductal carcinoma; LVI, lymphovascular invasion; LN, lymph node; n.a., not applicable/available; CAD, coronary artery disease; DCIS, ductal carcinoma in situ.

Clinical outcomes (Tables 2, 3, 4, 5)

Table 2.

Surgical complications: immediate autologous breast reconstruction and adjuvant radiotherapy including non‐comparative studies (adjuvant radiotherapy only)

| No. of patients | Follow‐up (months) | Total no. of complications | No. of reoperations for complications | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | GRADE | ROBINS‐I | Adjuvant RT | No adjuvant RT | Adjuvant RT | No adjuvant RT | Adjuvant RT | No adjuvant RT | Adjuvant RT | No adjuvant RT |

| Chatterjee et al.59 | Low | Serious | 22 | 46 | 54* | 36* | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Cooke et al.60 | Moderate | Moderate | 64 | 61 | 12 | 12 | 20 | 16 | 6 | 1 |

| O'Connell et al.58 | Low | Serious | 28 | 80 | 27·5* | 48·7* | 11 | 20 | 4 | 8 |

| Peeters et al.66 | Low | Serious | 16 | 109 | ≥ 12 | ≥ 12 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Rogers and Allen61 | Low | Serious | 30 | 30 | 19·9 | 17·4 | 65 | 41 | 32 | 26 |

| Billig et al.62 | Moderate | Moderate | 108 | n.a. | 24 | n.a. | 81 | n.a. | 5 | n.a. |

| Huang et al.63 | Low | Serious | 82 | n.a. | 40* | n.a. | 131 | n.a. | 5 | n.a. |

Values are median. GRADE, Grading of Recommendation, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (tool for grading the quality of evidence); ROBINS‐I, Risk Of Bias In Non‐randomised Studies – of Interventions (tool for assessing risk of bias); RT, radiotherapy; n.a., not applicable/available.

Table 3.

Clavien–Dindo classification of surgical complications: immediate autologous breast reconstruction and adjuvant radiotherapy including non‐comparative studies (adjuvant radiotherapy only)

| Adjuvant RT versus no adjuvant RT | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clavien‐Dindo complication grade† | |||||||

| Reference | Total flap loss | Partial flap loss* | Fat necrosis* | Wound dehiscence and delayed wound healing* | II | IIIa | IIIb |

| Chatterjee et al.59 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Cooke et al.60 | 0 versus 0 | 9 versus 6 | 2 versus 1 | 3 versus 5 | 2 versus 4 | n.a. | 6 versus 1 |

| O'Connell et al.58 | 0 versus 0 | 0 versus 0 | 1 versus 2 | 4 versus 9 | 3 versus 3 | 3 versus 3 | 1 versus 5 |

| Peeters et al.66 | n.a. | n.a. | 6 versus 36 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Rogers and Allen61 | n.a. | n.a. | 7 versus 0‡ | 11 versus 8 | 5 versus 7 | 7 versus 0 | 25 versus 26 |

| Billig et al.62 | 0 versus n.a. | n.a. | 4 versus n.a. | 17 versus n.a. | 8 versus n.a. | n.a. | 5 versus n.a. |

| Huang et al.63 | 0 versus n.a. | n.a. | 7 versus n.a. | n.a. | 82 versus n.a. | 5 versus n.a. | n.a. |

*Complication grades were not always defined or classified. †Grade II, complications requiring pharmacological treatment with drugs other than those allowed for grade I complications (drugs other than antiemetics, antipyretics, analgesics, diuretics and electrolytes); grade IIIa, complications requiring surgical intervention not under general anaesthesia; grade IIIb, complications requiring surgical intervention under general anaesthesia. RT, radiotherapy; n.a. not applicable/available. ‡P < 0·050.

Table 4.

Surgical complications: delayed autologous breast reconstruction and neoadjuvant radiotherapy including non‐comparative studies (neoadjuvant radiotherapy only)

| No. of patients | Follow‐up (months) | Total no. of complications | No. of reoperations for complications | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | GRADE | ROBINS‐I | Neoadjuvant RT | No neoadjuvant RT | Neoadjuvant RT | No neoadjuvant RT | Neoadjuvant RT | No neoadjuvant RT | Neoadjuvant RT | No neoadjuvant RT |

| Modarressi et al.64 | Low | Serious | 60 | 45 | 1 | 1 | 20 | 9 | n.a. | n.a. |

| Mull et al.65 | Low | Serious | 142 | 312 | 1 | 1 | 26 | 45 | 26 | 45 |

| O'Connell et al.58 | Low | Serious | 38 | 80 | 50·3* | 48·7* | 12 | 20 | 3 | 8 |

| Peeters et al.66 | Low | Serious | 77 | 109 | ≥ 12 | ≥ 12 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Baumann et al.69 | Moderate | Moderate | 189 | n.a. | 11† | n.a. | 88 | n.a. | 69 | n.a. |

| Billig et al.62 | Moderate | Moderate | 67 | n.a. | 24 | n.a. | 37 | n.a. | 1 | n.a. |

| Levine et al.67 | Moderate | Moderate | 50 | n.a. | 22·7† | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 3 | n.a. |

| Temple et al.68 | Low | Serious | 100 | n.a. | ≥ 12 | n.a. | 41 | n.a. | 18 | n.a. |

Values are *median and †mean. GRADE, Grading of Recommendation, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (tool for grading the quality of evidence); ROBINS‐I, Risk Of Bias In Non‐randomised Studies – of Interventions (tool for assessing risk of bias); RT, radiotherapy; n.a., not applicable/available.

Table 5.

Clavien–Dindo classification of surgical complications: delayed autologous breast reconstruction and neoadjuvant radiotherapy including non‐comparative studies (neoadjuvant radiotherapy only)

| Neoadjuvant RT versus no neoadjuvant RT | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clavien‐Dindo complication grade† | |||||||

| Reference | Total flap loss | Partial flap loss* | Fat necrosis* | Wound dehiscence and delayed wound healing* | II | IIIa | IIIb |

| Modarressi et al.64 | 2 versus 1 | 12 versus 2 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Mull et al.65 | 5 versus 15 | 7 versus 5‡ | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 26 versus 45 |

| O'Connell et al.58 | 0 versus 0 | 0 versus 0 | 2 versus 2 | 7 versus 9 | 2 versus 3 | 0 versus 3 | 3 versus 5 |

| Peeters et al.66 | n.a. | n.a. | 29 versus 36 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Baumann et al.69 | 5 versus n.a. | 14 versus n.a. | 15 versus n.a. | 22 versus n.a. | 4 versus n.a. | n.a. | 69 versus n.a. |

| Billig et al.62 | 0 versus n.a. | n.a. | 7 versus n.a. | 11 versus n.a. | 4 versus n.a. | n.a. | 1 versus n.a. |

| Levine et al.67 | n.a. | 1 versus n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Temple et al.68 | 2 versus n.a. | 7 versus n.a. | 16 versus n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 18 versus n.a. |

Complication grades were not always defined or classified.

Grade II, complications requiring pharmacological treatment with drugs other than those allowed for grade I complications (drugs other than antiemetics, antipyretics, analgesics, diuretics and electrolytes); grade IIIa, complications requiring surgical intervention not under general anaesthesia; grade IIIb, complications requiring surgical intervention under general anaesthesia. RT, radiotherapy; n.a. not applicable/available.

P < 0·050.

No study prospectively graded surgical complications according to an accepted classification such as CDC (fat necrosis, partial or total flap loss, infection and wound complications). One study64 graded partial flap loss using a novel flap necrosis classification system, adapted from Kwok et al.70. Only 30 per cent of all surgical complications (30 of 99) reported across the 12 included studies were defined a priori.

Adjuvant post‐mastectomy radiotherapy

Meta‐analyses comparing PMRT (350 patients; mean follow‐up 27·1 (range 12·0–54·0) months) and no radiotherapy (326 patients; mean follow‐up 25·2 (12·0–48·7) months) showed no interstudy differences in rates of: overall complications (233 patients; odds ratio (OR) 1·52 (95 per cent c.i. 0·84 to 2·75), Z = 1·40, P = 0·160) (Fig. 2 a); CDC grade III surgical complications (233 patients; OR 2·35 (0·63 to 8·81), Z = 1·27, P = 0·200) (Fig. 2 b); CDC grade II (293 patients; OR 0·94 (0·32 to 2·76), Z = 0·11, P = 0·910) (Fig. 2 c); or fat necrosis (418 patients; OR 1·83 (0·67 to 5·00), Z = 1·18, P = 0·240) (Fig. 2 d). There were no differences in rates of infection (293 patients; OR 0·94 (0·32 to 2·76), Z = 0·11, P = 0·910) (Fig. S1 a, supporting information) or wound complications (293 patients; OR 1·16 (0·56 to 2·39), Z = 0·40, P = 0·690) (Fig. S1 b, supporting information). There were no total flap losses.

Figure 2.

Forest plots comparing adjuvant radiotherapy with no radiotherapy a Overall complications, b Clavien–Dindo classification (CDC) grade III complications, c CDC grade II complications, d fat necrosis. A Mantel–Haenszel random‐effects model was used for meta‐analysis. Odds ratios are shown with 95 per cent confidence intervals. RT, radiotherapy.

Neoadjuvant radiotherapy

Comparisons between neoadjuvant radiotherapy (723 patients; mean follow‐up 16·8 (range 1·0–50·3) months) and no radiotherapy (546 patients; mean follow‐up 15·7 (1·0–48·7) months) showed no differences in overall complications (677 patients; OR 1·45 (95 per cent c.i. 0·97 to 2·18), Z = 1·82, P = 0·070) (Fig. 3 a) and CDC grade III surgical complications (572 patients; OR 1·24 (0·76 to 2·04), Z = 0·85, P = 0·390) (Fig. 3 b). One comparative study58 reported similar CDC grade II complications between neoadjuvant and no radiotherapy (118 patients; OR 1·43 (0·23 to 8·91), Z = 0·38, P = 0·700). There were no differences in rates of fat necrosis (304 patients; OR 1·29 (0·72 to 2·30), Z = 0·85, P = 0·400) (Fig. 3 c). Rates of partial flap loss were higher for neoadjuvant radiotherapy than for no radiotherapy (559 patients; OR 3·85 (1·51 to 9·76), Z = 2·83, P = 0·005) (Fig. S2 a, supporting information), with no differences in rates of total flap loss (559 patients; OR 0·81 (0·31 to 2·09), Z = 0·44, P = 0·660) (Fig. S2 b, supporting information).

Figure 3.

Forest plot comparing neoadjuvant radiotherapy with no radiotherapy a Overall complications, b Clavien–Dindo classification (CDC) grade III complications, c fat necrosis. A Mantel–Haenszel random‐effects model was used for meta‐analysis. Odds ratios are shown with 95 per cent confidence intervals. RT, radiotherapy.

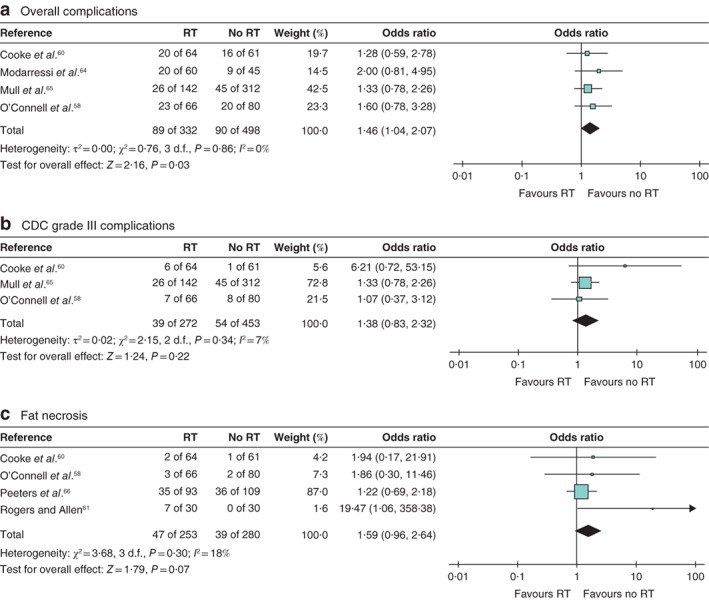

Combined adjuvant and neoadjuvant radiotherapy

Meta‐analyses of pooled PMRT and neoadjuvant radiotherapy compared with pooled no radiotherapy groups (mean follow‐up 18·3 (range 1·0–48·7) months) were performed as a potential hypothesis‐generating exercise. This showed significantly higher overall complications in the combined radiotherapy groups compared with no radiotherapy (830 patients; OR 1·46 (95 per cent c.i. 1·04 to 2·07), Z = 2·16, P = 0·030) (Fig. 4 a). There were no interstudy differences in: CDC grade III complications (725 patients; OR 1·38 (0·83 to 2·32), Z = 1·24, P = 0·220) (Fig. 4 b); CDC grade II complications (331 patients; OR 0·89 (0·37 to 2·10), Z = 0·28, P = 0·780) (Fig. S3 a, supporting information); rates of fat necrosis (533 patients; OR 1·59 (0·96 to 2·64), Z = 1·79, P = 0·070) (Fig. 4 c); or emergency reoperations for complications (725 patients; OR 1·38 (0·83 to 2·32), Z = 1·24, P = 0·220) (Fig. S3 b, supporting information). Rates of partial flap loss were also higher in the combined versus no radiotherapy groups (684 patients; OR 2·59 (1·27 to 5·28), Z = 2·63, P = 0·009) (Fig. S3 c, supporting information), with no differences in rates of total flap loss (559 patients; OR 0·81 (0·31 to 2·09), Z = 0·44, P = 0·660) (Fig. S3 d, supporting information), infection (331 patients; OR 0·89 (0·37 to 2·10), Z = 0·28, P = 0·780) (Fig. S3 e, supporting information) or wound complications (dehiscence/delayed wound healing) (331 patients; OR 1·29 (0·68 to 2·47), Z = 0·78, P = 0·430) (Fig. S3 f, supporting 1information).

Figure 4.

Forest plot comparing combined adjuvant and neoadjuvant radiotherapy with no radiotherapy a Overall complications, b Clavien–Dindo classification (CDC) grade III complications, c fat necrosis. A Mantel–Haenszel random‐effects model was used for meta‐analysis. Odds ratios are shown with 95 per cent confidence intervals. RT, radiotherapy.

Assessment of heterogeneity and meta‐analyses

Clinical outcomes within studies of PMRT versus no radiotherapy were homogeneous (I 2 values below 50 per cent). All remaining meta‐analyses of outcomes were similar (neoadjuvant radiotherapy versus no radiotherapy, pooled PMRT and neoadjuvant radiotherapy versus no radiotherapy).

Quality of life

There was limited reporting of patient‐reported QOL; outcomes were detailed in only two prospective studies60, 62 and one retrospective study58, with small patient numbers and short follow‐ups for the PMRT groups58, 60, 62. A priori hypothesis‐driven selection of QOL domains was absent from methods58, 60, 62, with no reporting of missing data or how this problem was tackled34.

Three studies58, 60, 62 used the BREAST‐Q and one60 used the breast cancer‐specific questionnaire (EORTC QLQ‐BR23)42. One small study58 reported significantly better ‘satisfaction with breast’ (P = 0·008) after a median follow‐up of 27·5 months for PMRT compared with 48·7 months for no radiotherapy (Table S2 , supporting information). The moderate‐quality comparative prospective study60 found a significant adverse impact of PMRT on breast symptoms at 1 year (P < 0·001) compared with no radiotherapy (Table S2 , supporting information).

The third study62 evaluated serial QOL outcomes, concluding a significant impact of PMRT on QOL domains (BREAST‐Q) at 1 and 2 years, despite the absence of a control group (no radiotherapy). Moreover, clinical significance was defined as P = 0·05, which may not account for multiple variables (Table S2 , supporting information)43, 62. Highly significant abdominal adverse effects in a small patient group (108 patients) may be unrelated to PMRT, but rather an indication of donor site morbidity. Interestingly, when evaluating the impact of neoadjuvant radiotherapy in a small non‐comparative study62, significant time‐related improvements in most QOL domains were observed, except lower physical well‐being relating to the abdomen at 1 year (Table S3 , supporting information).

Cosmetic outcomes

Three studies58, 61, 63 evaluated PMRT and the effects on aesthetic outcomes (187 patients). There was no standardized evaluation of cosmetic outcomes, precluding meta‐analyses. Studies lacked robust methodology.

Discussion

The mixture of underpowered observational studies included in this review were, in large part, lacking contemporaneous data to reflect current practice. Most were retrospective single‐centre cohorts, demonstrating poor levels of clinical evidence (levels 3 and 4) with insufficient follow‐up11.

A previous study24 of over 40 000 women undergoing BRR in 134 studies found that only 20 per cent reported a priori surgical complications, as well as inconsistent interstudy definitions24. The present review found similar interstudy discrepancies, without uniform adoption of the CDC26. The present authors graded all reported surgical complications using the CDC. All surgical interventions were graded as CDC IIIa or IIIb, and surgical reoperations were differentiated according to whether they were for complications or cosmetic revisions. Some complications were not amenable to retrospective grading in three studies64, 66, 67. In one66, it was not possible to determine whether fat necrosis required surgical revision for each radiotherapy group (adjuvant or neoadjuvant), compared with no radiotherapy. A second64 omitted individual abdominal complications relative to timings of radiotherapy, and the third67 omitted overall numbers of complications. Reviewed studies also failed to define postoperative wound infections according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention criteria71.

The IDEAL (Idea, Development, Exploration, Assessment, Long‐term study) Collaboration describes key methodological criteria for robust prospective cohort studies72: studies should be powered on the effect size of primary outcomes evaluating interventions of interest. The Mastectomy and Breast Reconstruction Outcomes Collaborative (MROC) is a multicentre prospective cohort study that provides IDEAL level 2b evidence for clinical safety and satisfactory QOL outcomes in the evaluation of surgical complications in immediate autologous reconstructions with PMRT versus no radiotherapy (delayed BRR) in 11 US centres17, 60. The MROC cohort data were excluded from this systematic review based on its reporting of group‐related summative data for all types of autologous reconstruction, as opposed to individual abdominal donor sites.

The MROC has reported all surgical complications at 2 years and demonstrated that PMRT (versus no radiotherapy) was significantly associated with a greater risk of developing any complication (OR 1·50 (95 per cent c.i. 1·20 to 1·86); P < 0·001), reoperative complications (OR 1·52 (1·17 to 1·97); P < 0·002) and wound infection (OR 2·77 (1·78 to 4·31); P < 0·001)16. Autologous BRR was done more commonly in irradiated than non‐irradiated patients (38 versus 25 per cent respectively; P < 0·001), with similarly low rates (1–2·4 per cent) of reconstruction failure at 2 years17.

Eligible studies in the present systematic review were significantly underpowered in comparison with the MROC study, which evaluated irradiated autologous BRR at 1 year (236 patients) and 2 years (199), and non‐irradiated procedures at 1 year (1625) and 2 years (332). The MROC data showed no differences between radiotherapy and no radiotherapy groups in the rates of total complications (25·6 versus 28·3 per cent respectively), major complications (17·6 versus 22·9 per cent) or flap failure (1·0 versus 2·4 per cent) at 2 years after immediate autologous reconstruction17. Studies in the present review showed significantly lower rates of major complications after radiotherapy compared with the MROC results, suggesting suboptimal overall reporting of surgical complications in the reviewed studies24.

The retrospective grading of surgical complications in the two moderate‐quality studies reported showed a rate of major complications (CDC grade IIIb) of 9 per cent (6 of 64) at 1 year, and 4·6 per cent (5 of 108) at 2 years60, 62. These rates are also likely to reflect under‐reporting compared with the MROC rates of 14·8 per cent (35 of 236) at 1 year and 17·6 per cent (35 of 199) at 2 years17. Despite its strengths, the MROC cohort is based on the review of complications from electronic patient records, potentially also underestimating true complication rates17.

One way to measure what matters to patients is to use patient‐reported outcome measures (PROMs) to assess the effects of disease or treatment on symptoms, functioning and health‐related QOL34. In this systematic review, PROMs were poorly reported and underpowered for overall small effect sizes of individual QOL domains43. Preliminary conclusions regarding statistical significance were not substantiated by adequate patient numbers, lack of a comparator group or prospectively defined time points for questionnaire collection58. Standardized and objective evaluations of cosmetic outcome have also remained elusive with emerging adoption of newer technologies such as the Vectra® XT58. Robust study designs evaluating these innovations should be accompanied by surgery‐ and disease‐specific questionnaires34.

Clear recommendations for the optimal timing of radiotherapy in relation to autologous BRR will remain elusive until information from high‐quality systematic reviews forms part of shared preoperative decision‐making73.

Adequately powered prospective studies and ongoing audits, to allow comparisons of postoperative radiotherapy with neoadjuvant radiotherapy, are warranted. Current evidence for irradiating autologous abdominal flaps remains weak, involving only two moderate‐quality studies of the 12 included in this report. Future cohort studies should be designed and powered to take advantage of newly evolving study designs, such as multiple‐cohort RCTs or trials within cohorts74. These designs permit collection of big data within registry or cohort platforms, and allow multiple synchronous randomized trials to be conducted in a cost‐effective manner74.

Supporting information

Table S1 Baseline characteristics of eligible studies

Table S2 Study evaluating patient‐reported quality of life in immediate autologous breast reconstruction comparing adjuvant radiotherapy with no radiotherapy, and non‐comparative study (adjuvant radiotherapy only)

Table S3 Study evaluating patient‐reported quality of life in delayed autologous breast reconstruction comparing neoadjuvant radiotherapy with no radiotherapy, and non‐comparative study (neoadjuvant radiotherapy only)

Fig. S1 Forest plot comparisons for adjuvant radiotherapy versus no adjuvant radiotherapy

Fig. S2 Forest plot comparisons for neoadjuvant radiotherapy versus no neoadjuvant radiotherapy

Fig. S3 Forest plot comparisons for combined adjuvant and neoadjuvant radiotherapy versus no radiotherapy

Acknowledgements

The authors thank R. Davidson, who assisted in the formatting of tables and figures for this publication, and K. Cocks (Chartered Medical Statistician in QOL and clinical trials, Select Statistics, UK) for her advice on ‘clinically meaningful differences’ in QOL assessment.

A.K. is a Kellogg Scholar at the University of Oxford and receives funding equating to the scholarship amount. A.L.P. is the co‐developer of the BREAST‐Q and receives royalties when the BREAST‐Q is used in industry‐sponsored clinical trials. Z.E.W. is the co‐developer of the EORTC QLQ‐BRECON23.

Disclosure: The authors declare no other conflict of interest.

Funding information

No funding

Presented to the Tenth Congress of the World Society of Reconstructive Microsurgery, Bologna, Italy, June 2019

References

- 1. Ginsburg O, Bray F, Coleman MP, Vanderpuye V, Eniu A, Kotha SR et al The global burden of women's cancers: a grand challenge in global health. Lancet 2017; 389: 847–860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Winters S, Martin C, Murphy D, Shokar NK. Breast cancer epidemiology, prevention, and screening. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci 2017; 151: 1–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Veronesi U, Cascinelli N, Mariani L, Greco M, Saccozzi R, Luini A et al Twenty‐year follow‐up of a randomized study comparing breast‐conserving surgery with radical mastectomy for early breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2002; 347: 1227–1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. van Maaren MC, le Cessie S, Strobbe LJA, Groothuis‐Oudshoorn CGM, Poortmans PMP, Siesling S. Different statistical techniques dealing with confounding in observational research: measuring the effect of breast‐conserving therapy and mastectomy on survival. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2019; 145: 1485–1493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ho AY, Hu ZI, Mehrara BJ, Wilkins EG. Radiotherapy in the setting of breast reconstruction: types, techniques, and timing. Lancet Oncol 2017; 18: e742–e753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. O'Halloran N, Potter S, Kerin M, Lowery A. Recent advances and future directions in postmastectomy breast reconstruction. Clin Breast Cancer 2018; 18: e571–e585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yang TJ, Ho AY. Radiation therapy in the management of breast cancer. Surg Clin North Am 2013; 93: 455–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Macdonald SM, Harris EE, Arthur DW, Bailey L, Bellon JR, Carey L et al ACR Appropriateness Criteria® locally advanced breast cancer. Breast J 2011; 17: 579–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. EBCTCG (Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group) , McGale P, Taylor C, Correa C, Cutter D, Duane F, Ewertz M et al Effect of radiotherapy after mastectomy and axillary surgery on 10‐year recurrence and 20‐year breast cancer mortality: meta‐analysis of individual patient data for 8135 women in 22 randomised trials. Lancet 2014; 383: 2127–2135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Marks LB, Kaidar‐Person O, Poortmans P. Regarding current recommendations for postmastectomy radiation therapy in patients with one to three positive axillary lymph nodes. J Clin Oncol 2017; 35: 1256–1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Recht A, Comen EA, Fine RE, Fleming GF, Hardenbergh PH, Ho AY et al Postmastectomy radiotherapy: an American Society of Clinical Oncology, American Society for Radiation Oncology, and Society of Surgical Oncology focused guideline update. Ann Surg Oncol 2017; 24: 38–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kunkler IH, Dixon JM, Maclennan M, Russell NS. European interpretation of North American post mastectomy radiotherapy guideline update. Eur J Surg Oncol 2017; 43: 1805–1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Russell NS, Kunkler IH, van Tienhoven G. Determining the indications for post mastectomy radiotherapy: moving from 20th century clinical staging to 21st century biological criteria. Ann Oncol 2015; 26: 1043–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Donker M, van Tienhoven G, Straver ME, Meijnen P, van de Velde CJ, Mansel RE et al Radiotherapy or surgery of the axilla after a positive sentinel node in breast cancer (EORTC 10981‐22023 AMAROS): a randomised, multicentre, open‐label, phase 3 non‐inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol 2014; 15: 1303–1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. O'Halloran N, Lowery A, Kalinina O, Sweeney K, Malone C, McLoughlin R et al Trends in breast reconstruction practices in a specialized breast tertiary referral centre. BJS Open 2017; 1: 148–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bennett KG, Qi J, Kim HM, Hamill JB, Pusic AL, Wilkins EG. Comparison of 2‐year complication rates among common techniques for postmastectomy breast reconstruction. JAMA Surg 2018; 153: 901–908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jagsi R, Momoh AO, Qi J, Hamill JB, Billig J, Kim HM et al Impact of radiotherapy on complications and patient‐reported outcomes after breast reconstruction. J Natl Cancer Inst 2018; 110: 157–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Barry M, Kell MR. Radiotherapy and breast reconstruction: a meta‐analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2011; 127: 15–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Potter S, Conroy EJ, Cutress RI, Williamson PR, Whisker L, Thrush S et al; iBRA Steering Group; Breast Reconstruction Research Collaborative . Short‐term safety outcomes of mastectomy and immediate implant‐based breast reconstruction with and without mesh (iBRA): a multicentre, prospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol 2019; 20: 254–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Santosa KB, Qi J, Kim HM, Hamill JB, Wilkins EG, Pusic AL. Long‐term patient‐reported outcomes in postmastectomy breast reconstruction. JAMA Surg 2018; 153: 891–899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Velikova G, Williams LJ, Willis S, Dixon JM, Loncaster J, Hatton M et al; MRC SUPREMO trial UK investigators . Quality of life after postmastectomy radiotherapy in patients with intermediate‐risk breast cancer (SUPREMO): 2‐year follow‐up results of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2018; 19: 1516–1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Momoh AO, Colakoglu S, de Blacam C, Gautam S, Tobias AM, Lee BT. Delayed autologous breast reconstruction after postmastectomy radiation therapy: is there an optimal time? Ann Plast Surg 2012; 69: 14–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kelley BP, Ahmed R, Kidwell KM, Kozlow JH, Chung KC, Momoh AO. A systematic review of morbidity associated with autologous breast reconstruction before and after exposure to radiotherapy: are current practices ideal? Ann Surg Oncol 2014; 21: 1732–1738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Potter S, Brigic A, Whiting PF, Cawthorn SJ, Avery KN, Donovan JL et al Reporting clinical outcomes of breast reconstruction: a systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst 2011; 103: 31–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Potter S, Holcombe C, Ward JA, Blazeby JM; BRAVO Steering Group . Development of a core outcome set for research and audit studies in reconstructive breast surgery. Br J Surg 2015; 102: 1360–1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg 2004; 240: 205–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pusic AL, Klassen AF, Scott AM, Klok JA, Cordeiro PG, Cano SJ. Development of a new patient‐reported outcome measure for breast surgery: the BREAST‐Q. Plast Reconstr Surg 2009; 124: 345–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Winters ZE, Benson JR, Pusic AL. A systematic review of the clinical evidence to guide treatment recommendations in breast reconstruction based on patient‐reported outcome measures and health‐related quality of life. Ann Surg 2010; 252: 929–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Winters ZE, Thomson HJ. Assessing the clinical effectiveness of breast reconstruction through patient‐reported outcome measures. Br J Surg 2011; 98: 323–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cano SJ, Klassen AF, Scott AM, Cordeiro PG, Pusic AL. The BREAST‐Q: further validation in independent clinical samples. Plast Reconstr Surg 2012; 129: 293–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Klassen AF, Pusic AL, Scott A, Klok J, Cano SJ. Satisfaction and quality of life in women who undergo breast surgery: a qualitative study. BMC Womens Health 2009; 9: 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tevis SE, James TA, Kuerer HM, Pusic AL, Yao KA, Merlino J et al Patient‐reported outcomes for breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2018; 25: 2839–2845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zinzindohoué C, Bertrand P, Michel A, Monrigal E, Miramand B, Sterckers N et al A prospective study on skin‐sparing mastectomy for immediate breast reconstruction with latissimus dorsi flap after neoadjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy in invasive breast carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 2016; 23: 2350–2356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Calvert M, Kyte D, Price G, Valderas JM, Hjollund NH. Maximising the impact of patient reported outcome assessment for patients and society. BMJ 2019; 364: k5267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Khajuria A, Winters Z, Mosahebi A. A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis of Clinical and Patient‐Reported Outcomes (PROs) of Immediate versus Delayed Autologous Abdominal‐Based Flap Breast Reconstruction in the Context of Post‐Mastectomy Radiotherapy [PROSPERO 2017 CRD42017077945] https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42017077945 [accessed 26 October 2019].

- 36. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP et al The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta‐analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009; 339: b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savović J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M et al ROBINS‐I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non‐randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016; 355: i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA, Eccles M, Falck‐Ytter Y, Flottorp S et al; GRADE Working Group . Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2004; 328: 1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wagner IJ, Tong WM, Halvorson EG. A classification system for fat necrosis in autologous breast reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg 2013; 70: 553–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Terwee CB, Prinsen CAC, Chiarotto A, Westerman MJ, Patrick DL, Alonso J et al COSMIN methodology for evaluating the content validity of patient‐reported outcome measures: a Delphi study. Qual Life Res 2018; 27: 1159–1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mokkink LB, Prinsen CA, Bouter LM, Vet HC, Terwee CB. The COnsensus‐based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments (COSMIN) and how to select an outcome measurement instrument. Braz J Phys Ther 2016; 20: 105–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Winters ZE, Afzal M, Rutherford C, Holzner B, Rumpold G, da Costa Vieira RA et al; European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Group . International validation of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ‐BRECON23 quality‐of‐life questionnaire for women undergoing breast reconstruction. Br J Surg 2018; 105: 209–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Winters ZE, Afzal M, Balta V, Freeman J, Llewellyn‐Bennett R, Rayter Z et al; Prospective Trial Management Group . Patient‐reported outcomes and their predictors at 2‐ and 3‐year follow‐up after immediate latissimus dorsi breast reconstruction and adjuvant treatment. Br J Surg 2016; 103: 524–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Williamson A, Hoggart B. Pain: a review of three commonly used pain rating scales. J Clin Nurs 2005; 14: 798–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jensen MP, Turner JA, Romano JM, Fisher LD. Comparative reliability and validity of chronic pain intensity measures. Pain 1999; 83: 157–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cella D, Yount S, Rothrock N, Gershon R, Cook K, Reeve B et al; PROMIS Cooperative Group . The Patient‐Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): progress of an NIH Roadmap cooperative group during its first two years. Med Care 2007; 45: S3–S11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Melzack R. The McGill pain questionnaire: major properties and scoring methods. Pain 1975; 1: 277–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD‐7. Arch Intern Med 2006; 166: 1092–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ‐9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001; 16: 606–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. O'Connell RL, Khabra K, Bamber JC, deSouza N, Meybodi F, Barry PA et al Validation of the Vectra XT three‐dimensional imaging system for measuring breast volume and symmetry following oncological reconstruction. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2018; 171: 391–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Liu Z, Yao Z, Li C, Liu X, Chen H, Gao C. A step‐by‐step guide to the systematic review and meta‐analysis of diagnostic and prognostic test accuracy evaluations. Br J Cancer 2013; 108: 2299–2303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta‐analysis. Stat Med 2002; 21: 1539–1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta‐analysis in clinical trials revisited. Contemp Clin Trials 2015; 45: 139–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ousmen A, Conroy T, Guillemin F, Velten M, Jolly D, Mercier M et al Impact of the occurrence of a response shift on the determination of the minimal important difference in a health‐related quality of life score over time. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2016; 14: 167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Musoro ZJ, Hamel JF, Ediebah DE, Cocks K, King MT, Groenvold M et al; EORTC Quality of Life Group . Establishing anchor‐based minimally important differences (MID) with the EORTC quality‐of‐life measures: a meta‐analysis protocol. BMJ Open 2018; 8: e019117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Cano SJ, Klassen AF, Scott A, Alderman A, Pusic AL. Interpreting clinical differences in BREAST‐Q scores: minimal important difference. Plast Reconstr Surg 2014; 134: 173e–175e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Mundy LR, Homa K, Klassen AF, Pusic AL, Kerrigan CL. Normative data for interpreting the BREAST‐Q: augmentation. Plast Reconstr Surg 2017; 139: 846–853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. O'Connell RL, Di Micco R, Khabra K, Kirby AM, Harris PA, James SE et al Comparison of immediate versus delayed DIEP flap reconstruction in women who require postmastectomy radiotherapy. Plast Reconstr Surg 2018; 142: 594–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Chatterjee JS, Lee A, Anderson W, Baker L, Stevenson JH, Dewar JA et al Effect of postoperative radiotherapy on autologous deep inferior epigastric perforator flap volume after immediate breast reconstruction. Br J Surg 2009; 96: 1135–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Cooke AL, Diaz‐Abele J, Hayakawa T, Buchel E, Dalke K, Lambert P. Radiation therapy versus no radiation therapy to the neo‐breast following skin‐sparing mastectomy and immediate autologous free flap reconstruction for breast cancer: patient‐reported and surgical outcomes at 1 year‐a mastectomy reconstruction outcomes consortium (MROC) substudy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2017; 99: 165–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Rogers NE, Allen RJ. Radiation effects on breast reconstruction with the deep inferior epigastric perforator flap. Plast Reconstr Surg 2002; 109: 1919–1924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Billig J, Jagsi R, Qi J, Hamill JB, Kim HM, Pusic AL et al Should immediate autologous breast reconstruction be considered in women who require postmastectomy radiation therapy? A prospective analysis of outcomes. Plast Reconstr Surg 2017; 139: 1279–1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Huang CJ, Hou MF, Lin SD, Chuang HY, Huang MY, Fu OY et al Comparison of local recurrence and distant metastases between breast cancer patients after postmastectomy radiotherapy with and without immediate TRAM flap reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 2006; 118: 1079–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Modarressi A, Müller CT, Montet X, Rüegg EM, Pittet‐Cuénod B. DIEP flap for breast reconstruction: is abdominal fat thickness associated with post‐operative complications? J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2017; 70: 1068–1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Mull AB, Qureshi AA, Zubovic E, Rao YJ, Zoberi I, Sharma K et al Impact of time interval between radiation and free autologous breast reconstruction. J Reconstr Microsurg 2017; 33: 130–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Peeters WJ, Nanhekhan L, Van Ongeval C, Fabré G, Vandevoort M. Fat necrosis in deep inferior epigastric perforator flaps: an ultrasound‐based review of 202 cases. Plast Reconstr Surg 2009; 124: 1754–1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Levine SM, Patel N, Disa JJ. Outcomes of delayed abdominal‐based autologous reconstruction versus latissimus dorsi flap plus implant reconstruction in previously irradiated patients. Ann Plast Surg 2012; 69: 380–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Temple CL, Strom EA, Youssef A, Langstein HN. Choice of recipient vessels in delayed TRAM flap breast reconstruction after radiotherapy. Plast Reconstr Surg 2005; 115: 105–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Baumann DP, Crosby MA, Selber JC, Garvey PB, Sacks JM, Adelman DM et al Optimal timing of delayed free lower abdominal flap breast reconstruction after postmastectomy radiation therapy. Plast Reconstr Surg 2011; 127: 1100–1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Lie KH, Barker AS, Ashton MW. A classification system for partial and complete DIEP flap necrosis based on a review of 17 096 DIEP flaps in 693 articles including analysis of 152 total flap failures. Plast Reconstr Surg 2013; 132: 1401–1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Mangram AJ, Horan TC, Pearson ML, Silver LC, Jarvis WR. Guideline for prevention of surgical site infection, 1999. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Am J Infect Control 1999; 27: 97–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Hirst A, Philippou Y, Blazeby J, Campbell B, Campbell M, Feinberg J et al No surgical innovation without evaluation: evolution and further development of the IDEAL framework and recommendations. Ann Surg 2019; 269: 211–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Elwyn G, Durand MA, Song J, Aarts J, Barr PJ, Berger Z et al A three‐talk model for shared decision making: multistage consultation process. BMJ 2017; 359: j4891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Young‐Afat DA, van Gils CH, van den Bongard H, Verkooijen HM; UMBRELLA Study Group . The Utrecht cohort for Multiple BREast cancer intervention studies and Long‐term evaLuAtion (UMBRELLA): objectives, design, and baseline results. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2017; 164: 445–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Baseline characteristics of eligible studies

Table S2 Study evaluating patient‐reported quality of life in immediate autologous breast reconstruction comparing adjuvant radiotherapy with no radiotherapy, and non‐comparative study (adjuvant radiotherapy only)

Table S3 Study evaluating patient‐reported quality of life in delayed autologous breast reconstruction comparing neoadjuvant radiotherapy with no radiotherapy, and non‐comparative study (neoadjuvant radiotherapy only)

Fig. S1 Forest plot comparisons for adjuvant radiotherapy versus no adjuvant radiotherapy

Fig. S2 Forest plot comparisons for neoadjuvant radiotherapy versus no neoadjuvant radiotherapy

Fig. S3 Forest plot comparisons for combined adjuvant and neoadjuvant radiotherapy versus no radiotherapy