Abstract

This article describes the nursing shortage situation in China and the causes for it. China is a major donor of nurses to other parts of the world and this article discusses the solutions China has implemented to address its nursing shortage, and the challenges that it is currently facing. The strategies that have been employed include: improving the health care system, improving work cultures for increased retention through policy and regulation, making greater investments in nursing education to build sustainable nursing education infrastructures, and enhancing the image of the nursing profession. These solutions may serve as a reference to other countries to deal with the crisis of a nursing shortage.

Today's health sectors worldwide face the challenge of providing high quality care, despite increasing healthcare costs and limited resources.1 In particular, the scarcity of qualified health personnel, including nurses, is being highlighted as one of the biggest obstacles to achieving the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) for improving the health and well-being of the global population.2

The term “nursing shortage” refers to the situation in which the demand for nurses is greater than the supply. According to the International Council of Nurses, the shortage is global in scale. In Canada, for instance, the shortfall of nurses is expected to be around 78 000 by 2011, and Australia projects a shortage of 40 000 nurses by 2010.2 The United States has the largest professional nurse workforce in the world, approximately 3 million, but it also does not produce enough nurses to meet the growing demand. In the US, a shortage of nearly 1 million professional nurses is predicted by 2020. 3 Inadequate supplies of hospital nurses will increase the workload for all nurses, lower the quality of nursing care and subsequently threaten the safety of patients. Studies have even reported a shortage of nurses to be associated with higher rates of patient mortality. 4 Other outcomes include increased risks for occupational injury, increased nursing turnover, and greater chances for nurses to solicit psychiatric assistance as a resource at high levels of job stress.5 Insufficient numbers of nurse educators are also an issue and leads to fewer students graduating from nursing schools to keep up with the demand which, ultimately, aggravates the nursing shortage.6, 7

This nursing shortage crisis is of concern to nursing leaders all over the world. In 1999, the planning committee of the Lillian Carter Centre for International Nursing (LCCIN), sponsored by the International Council of Nurses (ICN) and the World Health Organization (WHO), developed a questionnaire to identify the specific needs and challenges being faced by chief nursing officers (CNOs) all over the world. The shortage of nurses was reported as a major problem for 84% of CNOs responding to the survey.8

In order to alleviate this critical situation, recruiting nurses from abroad has been a strategy employed by many countries.9 However, most of the recipients are wealthy, industrialized countries such as the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Ireland, Australia, and New Zealand.10, 11 In other words, highly developed countries are the desired destinations for thousands of migrating nurses who seek adequate pay and good working conditions.1 As a result, this flow aggravates the imbalance between the supply and the demand in human resources in developing countries. For example, Africa, which has been a big supplier for qualified nurses for other countries, became the worst hit area and faces a serious shortage of nursing manpower.12 Though the critical situation in developing countries had been reported, few studies were focused on its actual reasons and potential solutions in these donor countries.

The purpose of this article is to share information and experiences about the nursing shortage in China. This article describes the situation and causes for the nursing shortage in China which is a major donor of nurses to other countries. Potential solutions for addressing this challenging issue by Chinese nurses are presented.

Nursing Shortage in China

China is a large developing country with abundant human resources. The nursing profession constitutes a large segment of the workforce in the health care system and very few professions offer the chance to create as much of an impact on the health of Chinese citizens as nursing. In spite of this, China is on the verge of a critical nursing shortage.

To assess whether there is a nursing shortage, data must be obtained on the demand for registered nurses as well as on the supply. When demand exceeds supply, there is a shortage. The World Health Organization has set a minimum standard of 1 nurse for every 500 people to make sure that the countries could achieve adequate coverage rates for selected primary health care interventions as prioritized by the Millennium Development Goals framework.

However, China had 1.65 million nurses by the end of 2008, which means, with a population of 1.3 billion, the country needs 5 million more nurses to catch up with the global standard. Although the country saw a large increase of 80 000 nurses in 2008, the number still cannot meet the demands for patient care.13 In July 2007, there was an investigation of 696 comprehensive Grade A hospitals in 31 provinces, municipalities, and autonomous regions. In China, Grade A hospitals are the hospitals that provide high quality and specialized medical health care service to several districts and are responsible for the education of nurses in the baccalaureate, master's and doctoral programs, as well as research. According to the investigation, these hospitals all had a very low ratio of nurses to beds (about 0.38 to 1) which was far lower than in other countries. According to the World Health Statistics 2009, the nurses-to-beds ratio ranges from a low of 1.1 in the African Region to a high of 1.25 to 1 in the European region.14 In that investigation, ward nurses in China were expected to provide care for at least 10-14 patients. For some, this figure was > 30 patients to 1 nurse. Sixty-five percent of “first line” nurses worked > 10 hours every day.15 In 2005, the Ministry of Health of the People's Republic of China (MOH, PRC) published the Nursing Development Plan in China (2005-2010), expecting that the nursing vacancy rate would reach 50% of all health worker positions by 2010. By the end of 2008, the vacancy rate of nursing was 27%, which means that there are at least 1.4 million vacancies for registered nurses (RN) that need to be filled. In fact, the total number of health professional graduates—including nurses, doctors, and dentists—will only be approximately 0.9 million based on the number of entrants to the colleges and secondary schools. It is no doubt that China is in a state of serious imbalance between the demand and the supply for nurses.

Causes for the Nursing Shortage in China

In China, the nursing shortage is complicated and is affected by many factors. There is, however, widespread consensus that major causes of the shortage of nurses fall within 2 categories: (1) inequities and imperfections within China's healthcare system, and (2) the recruitment of Chinese nurses by developed countries.

Inequity and Imperfections in China's Healthcare System

These are the most critical and internal factors that contribute to the nursing shortage in China. Changes in political structures, technology, and general globalization have led to the evolution of Chinese health care and the nursing profession just as they have in other parts of the world.16

At present, the reform of the health system in China, including innovations in the healthcare workforce, is still in process. Old and new systems exist in parallel in this particular era of reform, which leads to many unusual and inequitable practices. In China, nurses can be categorized into 2 kinds: formal employed nurses and contract supernumerary employed nurses (ie, temporary nurses). Most temporary nurses don't receive equal pay for equal work when compared to formal nurses. In a number of health institutions, a contract nurse earns half of the pay bonus of a formal nurse. As a result, many hospitals have reduced certain nurses' income by classifying them as temporary workers, which means they can pay them reduced salaries in order to cut costs. Additionally, in some hospitals, nurses employed by supernumerary contract cannot participate in continuing education, job promotions, and are not paid for public holidays.15 At the same time, hospital administrators in China are prone to hire more physicians than nurses because physicians are seen as a source of income generation related to surgeries and expensive medications.17 As a result, China has more physicians than nurses, which differs from most countries in the world. Table 1 depicts the nurse-to-physician ratio of the Western Pacific region (WPRO) as 1:4, which is the lowest of the 6 WHO regions. As a member of WPRO, the ratio in China (0.7) was far lower than the average level of even the WPRO.14 It is possible that the duties or responsibilities of nurses in China are different from nurses in other countries and could be a factor influencing the low ratio of nurses to physicians. Nurses are only permitted to do basic treatments, as the majority of nurses are not educated in higher academic degree programs but rather hold associate degrees and diplomas. In addition, patients often rely mostly on doctors in the traditional health system of China.

Table 1.

Ratio of Nurses and Midwives to Physicians in WHO Region and China, 2000-2007

| Region | Nursing and Midwifery Personnel Density∗ | Physicians Density | Ratio of Nurses and Midwives to Physicians |

|---|---|---|---|

| African Region | 11 | 2 | 5.5 |

| Region of the Americas | 49 | 19 | 2.6 |

| South-East Asia Region | 12 | 5 | 2.4 |

| European Region | 79 | 32 | 3.3 |

| Eastern Mediterranean Region | 15 | 10 | 1.5 |

| Western Pacific Region | 20 | 14 | 1.4 |

| China | 10 | 14 | 0.7 |

Density: per 10 000 population

Sources: World Health Organization. (2009). World Health Statistics 2009

This situation seriously affects the stability of the nursing team, and the inequities related to pay and status affect morale. Many nurses leave their posts in protest of a hospitals' poor working conditions, their own low socioeconomic and professional status, and poor job availability. As a result, hospital nurses who remain suffer from even heavier workloads and stress. In order to relieve the pressure on nurses, much of the patient care in hospitals is supplied by patients' relatives, or by unlicensed personnel, which obviously lowers the quality of nursing and subsequently threatens the safety of patients. Eventually, young women who would consider nursing, as well as dissatisfied nurses, seek other career opportunities, so it is expected that the shortage will worsen. It is reported that Shanghai has lost 13% of its nurses over the last 5 years.18 Among these nurses, 93% felt their job was too hard; 85% said the salary was too low; 84% felt that they were under too much pressure; and 81% complained about poor professional status.18

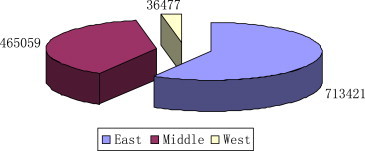

Why is China suffering a shortfall of 5 million nurses? Some believe this is due to poor labor planning, poor distribution of nurses, and imperfections in the healthcare system.19 Although jobs are always available in rural areas, the pay and working conditions are usually not attractive to many nurses. According to the statistics of the Ministry of Health of China, nurse density in urban areas is much higher than that in rural areas. There are 18.8 RNs per 10 000 population in urban cities and only 5.5 RNs per 10 000 population in rural areas. Hence, in rural China, the shortage is even worse (Table 2 ).20 The nurse distribution is also inequitable in regions with low incomes (Figure 1 ).20 Most RNs (713 421) work in eastern China with a highly developed economy. By contrast, there are many fewer RNs (only 36 477) in western China, which is also the poorest area in the country.20 Yet the unemployment rate in urban areas keeps increasing because many students with a diploma are denied by hospitals in urban and wealthy provinces, leading to a worsening imbalance and a waste of human resources. Sudhir Anand et al concluded these inequalities may also be associated with corresponding economic disparities (eg, between countries, between provinces, and between strata). 21

Table 2.

Registered Nurses in China, 2007

| Area | Number | Density∗ |

|---|---|---|

| Urban | 1165456 | 18.8 |

| Rural | 377801 | 5.5 |

| Total | 1543257 | 11.8 |

Density: per 10 000 population

Source: Chinese Health Statistics Yearbook 2008

Figure 1.

Area Distribution of Nurses in China

Nursing Recruitment of Chinese Nurses by Developed Countries

China, a big donor of nurse exports, has been experiencing the loss of valuable human resources in recent years. Since the adoption of the Opening-Up policy in 1978 (the Chinese economic reform led by Deng Xiaoping which opened up the economy to whole world), great progress has been achieved in China.22 Economic improvements and well-coordinated public health initiatives have resulted in dramatic decreases in the rates of most infectious diseases, lower infant mortality, and a corresponding increase in longevity of Chinese people. However, it has also brought about great foreign challenge and competition, especially after China's entry to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001. China, like other countries including India, the Philippines, South Africa, and Zimbabwe, becomes a major donor in this global nursing shortage as a result of its abundant supply and high unemployment rate for nurses. As discussed previously, many Chinese nurses are leaving the profession due to poor working conditions, low socioeconomic and professional status, and poor job availability. Others believe it is a good choice for them to move to developed countries in search of increased wages, better working conditions and continued educational opportunities. The average salary for entry-level nurses in some Chinese urban hospitals is equivalent to that of a janitor. By contrast, Chinese nurses can earn 30-50 times more if employed in the United States.23 As a result of China's very high level of unemployment and underemployment, these nurses are even being encouraged by the government to pursue international opportunities.

Receivers of Chinese nurses can be divided into 3 types: (1) the highly developed countries such as USA, Canada, Australia, UK, etc; (2) countries where Chinese constitute their main population, such as Singapore; (3) the Middle East countries which are near China geographically, such as Saudi Arabia. Some experts are concerned that this significant departure of Chinese nurses, especially the advanced nurses, will result in a crisis and hinder the healthy and sustainable development of nurses in China. Nurses who go abroad to work are primarily educated in college degree programs and communicate well in English. But China has a scarcity of these advanced nurses and can ill-afford this potential “brain drain.” In China, of all the registered nurses, only 2-3% have college degrees. Ninety percent of Chinese nurses hold an associate degree and about 7% hold a diploma.20

Solutions to the Nursing Shortage in China

An official of the Chinese Nursing Association (CNA) once stated that the organization hopes the resultant nurse shortage and subsequent negative effects on patient outcomes in China will be the ultimate trigger for Chinese healthcare reform. The Chinese Nursing Association believes the backlash of a national nurse shortage might improve the welfare of Chinese nurses.21 Solutions in several areas have been proposed and are discussed here. These include reform in the healthcare system, education, policy and regulations, and image improvement.

From Withdrawal to Re-engagement of Government

On April 6, 2009, the Chinese Government published the Healthcare Reform Plan, in part, on the basis of recommendations from WHO and the World Bank, as well as comments from the public.24 The government took a dominant role again after 2 decades of market-oriented healthcare reforms which have exposed increasing numbers of Chinese households to increasing catastrophic expenditures for health care. The government plans to invest 850 billion yuan in health services to provide basic insurance for 90% of the people by 2010, which will fill many gaps in the present system. For nursing, there has been a commitment to accelerated training of the nurse workforce, improved education, continuing professional development, and higher standards of training.

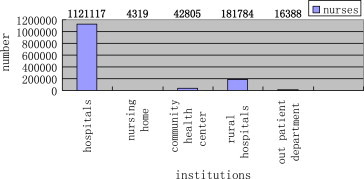

The report states clearly that one major objective is to develop urban health service centers for communities, which will become a new growth area for nurses' employment. Community nurses constitute half of the nurse workforce in developed countries.25 However, in China, few nurses work in community health service centers. According to the statistics from the Ministry of Health, PRC, there are only 0.04 million community nurses, which are far fewer than 1.12 million nurses employed in urban hospitals and the 0.18 million in rural hospitals (Figure 2 ).

Figure 2.

Nurses in various health institutions, 2007

In addition, the government will establish an “essential drugs” list with fixed prices, and construct a standard, open, and transparent guarantee “System for Pharmaceutical Supply” in China. As a result, the phenomenon of increasing the revenue of hospitals by excessive sales of drugs will be eliminated eventually. It is hoped that health managers and administrators will realize the importance of efficiency and quality and the imbalance of nurse-to-physician ratio in China will be addressed.

Develop and Sustain Cultures to Retain Nurses

Policies and regulations have been published to support development of professional cultures which will support and retain nurses. On January 23, 2008, the “Nursing Act” was signed by Premier Wen Jiabao to deal with major problems that existed in nursing. The head of the Office of Legislative Affairs claimed the primary objective for publishing occupational regulations was to safeguard the legitimate rights and interests of nurses. The act is viewed as a milestone in the process of nursing development in China. The rights of nurses were stated explicitly and fell into 4 categories: (1) better wages, benefits, and social security rights; (2) health protection and healthcare services; (3) improved individual development opportunities, and (4) professional development. In addition, the provision of encouragement and reward for outstanding nurses was also specified in the Act.26 The premier hoped these provisions would inspire the enthusiasm of nurses, attract more talented people to the nursing profession, and improve the overall quality of life for Chinese nurses.

Other policies were also published to provide for more nursing positions to address the increased unemployment rate of nursing students with associate or even lower degree. The government also plans to expand the scope of community nursing which will generate more nursing jobs for nurses.27 Research conducted by the Ministry of Health predicted that 1.036 million vacancies must be filled to meet the need by 2015.25 On the other hand, the Ministry has also, in past years, urged hospitals to lower the nurse-to-bed ratio (ie, less beds per nurse) by listing it as an important factor for appraising work of hospitals. The Nursing Act required that the nurse-to-bed ratio should reach the national standard for all hospitals in 2010. Finally, in 2004, nursing was identified as a profession requiring high technical talent for increased health demands in China, which promoted nursing as a rewarding career choice. This news encouraged people to enter and remain in nursing careers, thus reducing the growing shortage.28

Build Sustainable Nursing Education Infrastructures

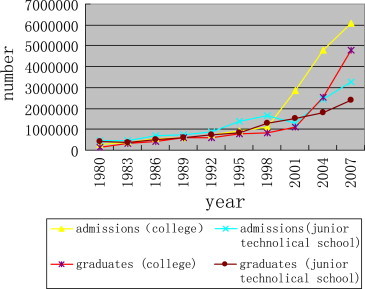

In the field of nursing education, the government has made a large investment to build sustainable nursing education infrastructures since higher education was revived in 1983. At present, the nursing education system in China includes diploma, associate degrees, baccalaureate and master's degrees, and doctoral programs. Over recent decades, there has been a massive expansion in the number of individuals admitted to medical, nursing, and other health-related education programs. Since 1998, the government has made a substantial effort to expand health professions education. From 1998-2007, the number of admissions to college level programs in medical and health-related fields expanded by 461% (increased from 1.1 million in 1998 to 6.1 million in 2007), while admissions to all junior technical schools in the same fields expanded by 94% (increased from 1.7 million in 1998 to 3.3 million in 2007). In the same period, the number of nurses grew by 27% (and by 7% for all health workers) (Figure 3 ). 20 Experts proposed that the average number of all nursing programs admissions should be about 150 000 annually from 2003-2010.25 By the year 2010, enrollment of nursing students from senior or junior schools will be reduced to 50%, while there will be a significant increase in the number of students of junior colleges or secondary technical schools by 30%, and an increase at the college level or above by 20%. In the past, most nurses were educated after they graduated from junior schools, but now the number of these programs are being gradually reduced. If that occurs, nurses with a diploma degree or above (ie, baccalaureate) will comprise > 30% of the nurses. In the third level hospitals, 50% of the nurses will have a diploma degree or above and, in the second level hospitals, 30% of the nurses will have a diploma degree or above.29 In China, the hospitals are divided into 3 levels according their function. Third level hospitals are Grade A hospitals, as described earlier. Second level hospitals are district hospitals that provide comprehensive medical and health care services to multiple communities and carry out some teaching and research activities. First level hospitals are community hospitals that directly provide primary healthcare services including disease prevention, medical care, health care and rehabilitation, to a certain population in the community. In addition, specialized nurse training has been an important goal of nursing education in recent years. Between 2005-2010, China also plans to develop programs to educate clinical nurse specialists (CNS) in the area of critical care nursing, organ transplant, operative nursing, nursing care of tumor patients, etc. However, in China, there is still much discussion about the level of education for the CNS program (i.e., bachelor or master's degree). According to the investigation of Shen Ning, 53% of nursing experts propose the CNS program should be at the bachelor degree level considering the actual situation of nursing in China.30

Figure 3.

Education of health workers, 1980-2007

Due to the limited educational resources, various methods have been tried to train nursing students in China. Military and civilian universities have cooperated with each other to reciprocally train students, which has proved to be a successful model in China. In China, military nursing education is of top quality. For example, the first nursing doctoral program in China was opened in the Second Military Medical University. However, in the era of peace, the demand for nurses in the military is not very high. Therefore, these advanced and abundant nursing faculties and other resources are available in the military. Nursing programs for non-military service are also run in military medical schools. In addition, military faculty members are asked to give lectures in civilian universities. The students trained in military school are welcomed by hospitals, for they are not only proficient in clinical skills but also have a strong physical capability to deal with the heavy workload in nursing practice.

At the same time, military institutions also educate the military students in cooperation with local institutions. Freshmen go to civilian universities to learn professional and liberal arts knowledge, and then come back to receive military training in military schools. In this way, educational resources can be best utilized, and the growing shortage can be reduced effectively.

The recruitment of nursing students by private schools also provides another solution. In the past, education was totally controlled by the government. Private schools for nursing are a new innovation in the education system in China. The private sector has been created to meet the need of healthcare facilities facing critical nursing shortages. However, it is a concern of some that the quality of these educational programs is often ignored by these agencies based on their economic interests. As a result, a higher education evaluation was initiated by the Ministry of Education (MOE) to improve the quality of education and to build a high quality, competent workforce. The entire process of the nursing educational program would be evaluated, and the outcome will be related to the funding received and discipline enforced if standards are not met. This evaluation process is expected to be an effective tool to ensure the quality of all nursing programs.

International organizations have also provided support that helps retain Chinese faculty. Through collaborative models with other universities, nursing leaders in China are moving towards development of their own models that merge the uniqueness of Eastern philosophy with elements of Western models. Supported by the China Medical Board (CMB), the Program on Higher Education Degrees in China (POHNED) was created to train competent nursing faculty and leaders in order to achieve higher retention rates. The first graduate nursing program in China was developed in cooperation with Chiang Mai University in Thailand. The Chiang Mai faculty were the primary faculty and they mentored returning graduates of the Committee on Graduate Nursing Education program(COGNE). Students spent one semester at Chiang Mai University to concentrate on community health nursing and gerontology, while practical learning experiences related to clinical, teaching, and research were conducted in the student's home university. By remaining more closely connected to their home institutions with less disruption on daily life and their families, the program was highly successful with all graduates initially returning to their home institutions. The POHNED programs demonstrate a unique model of international collaboration between developed and developing countries to meet the challenges of nursing education yet retain indigenous culture and control.31

The Image of the Nursing Profession in China

What the public generally thinks about nursing and how the media portrays nursing shapes the current image of the profession.32 Some studies in China found the image of nurses has improved based on their excellent performances during great disasters, including Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS, 2003) and the Sichuan earthquake (2008). According to Gu Hongwen's investigation, 91% of citizens surveyed thought that nurses should be included in middle social status group after SARS, compared with 77% before SARS.33 Researchers have found that media plays an important role in the improvement of image.33 A large number of reports during the SARS epidemic made people more aware of the important role of nurses in health care system and helped increase respect for nurses. In addition, the President awarded nurses the Nightingale Prize and granted other awards to them which were also widely covered by the mass media.

Of course, Chinese nurses have also made great efforts by themselves to shape the image of nurses. During the 2008 Olympic Games in Beijing, the volunteers team constituted by Chinese nurses had been well recognized for its high-quality and efficient service. The Chinese Nursing Association (CAN), an advocate for Chinese nurses, has worked hard to resume its seat in the International Council of Nurses . It is believed this will greatly enhance the international status of nursing in China. With an enhanced image of the nursing profession, a continuous flow of nursing students will be assured, which will hopefully end the continual shortage of nurses.

Conclusion

The nursing shortage—especially the faculty shortage—exists in many countries, including the US, which has the most advanced and extensive nursing system in the world. Many causes for nursing shortages are the same for China and other countries, despite significant cultural, political, and historical differences. Job dissatisfaction due to increased workloads, poor wages, and low social status are the common causes for nurses' movement into other occupations, or their reluctance to ever consider nursing as a viable career option.

The solutions implemented by nurses in China and by the Chinese government to eliminate factors that have undermined the desirability of nursing as a career have achieved a success in some areas. These strategies may also work in other countries to avert continued nursing shortages. The POHNED program, a unique collaborative model resulting in higher retention, can be introduced in other countries who have developed nursing to the initial stage, and also need larger numbers of qualified nursing faculty. To solve the nursing shortage via collaboration with the military may be another good strategy in some countries. For example, corpsmen could be encouraged to serve in civilian hospitals when they retire from the army. More nurses could be co-developed by greater cooperation of civilian universities and military colleges.

In the global context, a nursing shortage is not a single problem for a single country. It is the common challenge for all of us. In order to evade the deteriorating situation, it would serve nurses worldwide to unite to overcome the shortage crisis.

Biographies

Hu Yun is a doctoral candidate at the Nursing School of Second Military Medical University, Shanghai, China.

Shen Jie, MS, is a lecturer at the Nursing School of Second Military Medical University, Shanghai, China.

Jiang Anli, MEd, is a Professor at the Nursing School of Second Military Medical University, Shanghai, China.

Footnotes

This study was funded by the Foundation of Shanghai Key Discipline B903.

References

- 1.Kingma M. Nursing migration: Global treasure hunt or disaster-in-the-making? Nurs Inq. 2001;8:205–212. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1800.2001.00116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buchan J. Calman L. The Global Nursing Review Initiative. The Global Shortage of Registered Nurses: An Overview of Issue and Actions. International Council of Nurses, Geneva, Swizterland. Available at: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/summary?doi=10.1.1.138.3083&rep=rep1&type=pdf.

- 3.Nurse workforce challenges in The United States: Implications for Policy. Available at: http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/34/9/41431864.pdf. Accessed on January 29, 2010.

- 4.Shipman D., Hooten J. Without enough nurse educators there will be a continual decline in RNs and the quality of nursing care: Contending with the faculty shortage. Nurse Educ Today. 2008;28:521–523. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lovell V. U.S. Institute for Women's Policy Research; Washington, DC: 2006. Solving the Nursing Shortage through Higher Wages. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Janet D., Aldebron A., Aldebron J. A systematic assessment of strategies to address the nursing faculty shortage U.S. Nurs Outlook. 2008;56:286–297. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nally T.L. Nurse Faculty Shortage: The case for action. J Emerg Nurs. 2008;34:243–245. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Swenson M.J., Salmon, Wold J., Sibley L. Addressing the challenges of the global nursing community. Int Nurs Rev. 2005;52:173–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2005.00422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buchan J., O'May F. Globalisation and healthcare labour markets: A case study from the United Kingdom. HRDJ. 1999;3:199–209. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kline D.S. Push and Pull Factors in International Nurse Migration. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2003;35:107–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2003.00107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aiken L.H., Buchan J., Sochaiski J., Nichols B., Powell M. Trends in nurse migration. Health Aff. 2004;23:69–77. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.3.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oyowe A. Brain drain: Colossal loss of investment for developing countries. The Courier ACP-EU. 1996;159:59–60. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ministry of Health P.R China. The health reform and development of China in 2008. Available at: http://www.moh.gov.cn/publicfiles/business/htmlfiles/mohbgt/s6690/200902/39109.htm Accessed on March 13, 2009.

- 14.World Health Organization. World Health Statistics 2009. Available at: http://www.who.int/whosis/whostat/EN_WHS09_Full.pdf. Accessed on October 29, 2009.

- 15.yanhong Guo. “Nurses Act,” The background of the development and main content. Chinese Nursing Management. 2008;8:4–6. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ungos K., Thomas E. Lessons learned from China's healthcare system and nursing profession. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2008;40:275–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2008.00238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ministry Warns of Nurse Shortage. Available at: http://english.people.com.cn/200605/11/eng20060511/264646.html. Accessed on June 27, 2007.

- 18.Li L. Thinking about the trend of nursing migration. Today Nurse. 2008;1:16–17. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu Y., Zhang J. One size doesn't fit all: Ethics of international nurse recruitment from the conceptual framework of stakeholder interests. Nurs Ethics. 2005;12:571–581. doi: 10.1191/0969733005ne827oa. [Electronic version] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chinese Health Statistics Yearbook 2008. Available at: http://www.moh.gov.cn/publicfiles/business/htmlfiles/zwgkzt/pwstj/%3Cx:INFOURL%3E%3C/x:INFOURL%3E. Accessed on March 19, 2009.

- 21.Anand S., Fan V.Y., Zhang J., Zhang L., Ke Y., Dong Z. China's human resources for health: quantity, quality, and distribution. Lancet. 2008;372:1774–1781. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61363-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dong Z., Phillips M.R. Evolution of China's health-care system. Lancet. 2008;372:1715–1716. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61351-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu Y. International Nurse Migration. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2004;36:189. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Advice of the CPC Central Committee and State Council on Deepening the Reform of the Medical and Health Care System. Available at: http://www.moh.gov.cn/publicfiles//business/htmlfiles/wsb/%3Cx:INFOURL%3E%3C/x:INFOURL%3E. Accessed on April 6, 2009.

- 25.Liu H. Situation of nursing human resources in China and suggestions on enhancing training of nursing talents who are located as high-technical talent for rush demands. J Zhengzhou Railway Vocational College. 2004;16:7–8. [Google Scholar]

- 26.The State Council Nursing Act. J Nurs Adm. 2008;8:7–9. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Decisions of the central committee of the communist party of China and the State Council concerning public health reform and development. 1997. Available at: http://www.zuowenw.com/Article/200706/283902.html. (Published June19, 2007). Accessed on December 2, 2008.

- 28.The establishment of vocational institutions to train nurses who located as high-technical talent for rush demands. Available at: http://www.moe.edu.cn/edoas/website18/74/info274.htm. (Published August 7, 2004). Accessed on December 2, 2008.

- 29.Ministry of Health P.R China Nursing Development Plan in China (2005-2010) Chinese Hospitals. 2005:26–28. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xiaojie W., Ning S. A study on cultivation of clinical nurse specialist and related problems in China. Chinese Nurs Res. 2007;21:3197–3201. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sherwood G., Liu H. International collaboration for developing graduate education in China. Nurs Outlook. 2005;53:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ferri RS. Nurses and the Media: The Center for Nursing Advocacy 2006. Available at: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/524602. (Published March 16, 2006). Accessed on October 29, 2009.

- 33.Hongwen G., Lihong W., Lijuan L. Changes of nurses' social position before and after SARS and analysis on its related factors. Nurs Res. 2006;20:3139–3141. [Google Scholar]