Summary

Tissues from nine ferrets with granulomatous lesions similar to those seen in feline infectious peritonitis were examined histopathologically and immunohistochemically. Four main types of lesions were observed: diffuse granulomatous inflammation on serosal surfaces; granulomas with areas of necrosis; granulomas without necrosis; and granulomas with neutrophils. Other less commonly seen lesions were granulomatous necrotizing vasculitis and endogenous lipid pneumonia. FCV3-70 monoclonal antibody produced immunolabelling of group 1 coronavirus antigen in tissue samples from eight animals, the antigen being present in the cytoplasm of macrophages in the different types of granulomatous lesions.

Keywords: coronavirus, feline coronavirus, ferret, granuloma, Mustela putorius furo, viral infection

Introduction

Feline infectious peritonitis (FIP) is a common and fatal disease in cats and some non-domestic felids, caused by the feline coronavirus (FCoV) (Wack, 2003; Hartmann, 2005). This virus is included in the Coronaviridae family, a group of enveloped positive-stranded RNA viruses. FCoV belongs to group 1, which includes human coronavirus strain 229E, porcine transmissible gastroenteritis virus, canine coronavirus, porcine epidemic diarrhoea virus and ferret enteric coronavirus (FECV) (Wise et al., 2006).

Over the past few decades, ferrets (Mustela putorius furo) have become popular in the exotic pet trade. These animals usually share their habitat with other domestic animals and are therefore at risk of being infected with viral diseases, such as canine distemper or rabies (Brown, 2004). Recently, clinicians in the Barcelona area reported domestic ferrets with clinical signs and visceral lesions similar to those in cats with FIP. In 2004–5, tissues from ferrets affected by this novel disease were submitted to our laboratory. Some showed granulomatous lesions similar to those produced by FCoV in felids, and in some tissues FCoV virus-like antigen was detected (Martínez et al., 2006).

The purpose of this retrospective study was to characterize these granulomatous lesions and to demonstrate group 1 coronavirus antigen by immunohistochemical methods.

Materials and Methods

Samples

Paraffin wax-embedded tissues obtained in 2004–5 from nine ferrets (nos 1–9; Table 1 ) with granulomatous lesions were selected from the archive of the Pathology Diagnostic Service, Facultat de Veterinària, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. Because it was not possible to collect every tissue from each ferret, the samples consisted of kidney (n=8), spleen (7), lung (6), lymph node (5), intestine (5), liver (5), heart (4), pancreas (2) and adrenal gland (1) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Immunohistochemical examination of tissues from affected ferrets

|

Immunohistochemical results in |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ferret no. | kidney | spleen | lung | lymph node | intestine | liver | heart | pancreas | adrenal gland |

| 1 | − | − | − | + | − | N | N | N | N |

| 2 | − | N | N | + | N | N | N | N | N |

| 3 | + | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | + |

| 4 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | N | N |

| 5 | − | − | + | N | − | + | + | N | N |

| 6 | − | + | − | + | + | + | N | N | N |

| 7 | + | − | + | + | N | − | − | + | N |

| 8 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | N |

| 9 | N | + | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

+, Positive; –, negative; N, no available tissue.

Histopathology

Sections (4 μm) were cut from each tissue and stained with haematoxylin and eosin (HE). Granulomatous lesions were classified as proposed by Kipar et al. (1998a), with one minor modification, namely the addition of a new category of lesion (granuloma with neutrophils), described below. Additional sections were stained by the Ziehl–Neelsen, periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) and Warthin–Starry methods to exclude aetiological agents such as mycobacteria, other bacteria (including Helicobacter spp.), and fungal organisms.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

FCV3-70 monoclonal antibody (Custom Monoclonal Internationals, West Sacramento, CA, USA) was used to detect FCoV by the peroxidise-anti-peroxidase method described by Kipar et al. (1998a), positive and negative control tissues being included.

Results

Clinical Observations

The ferrets consisted of five males and four females, aged 4–24 months. All were privately owned and kept indoors. One was in contact with cats and four were housed with other ferrets. Clinical signs, which were non-specific, included diarrhoea, hind-limb weakness, anorexia and weight loss. Enlarged lymph nodes, splenomegaly, anaemia and hypergammaglobulinaemia were also present. Aleutian disease serology (Quickchek® ADV, Avecon Diagnostics, Bath, PA, USA) was negative in all cases. Treatment with corticosteroids, antibiotics and supportive care was unsuccessful and all animals eventually died or were humanely destroyed. Post-mortem examination was conducted by the clinician, who then submitted samples in formalin to the laboratory.

Immunohistochemical and Histopathological Findings

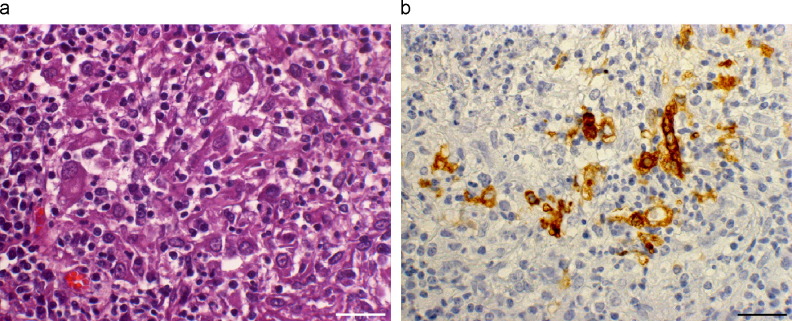

Various tissues from eight of the nine ferrets were positive by IHC for coronavirus antigen. Positive labelling was represented by a granular cytoplasmic precipitate in macrophages in the granulomatous lesions (Fig. 1a, b ). The numbers of positive tissues were as follows: lymph node (4 animals), kidney (2), spleen (2), lung (2), liver (2), pancreas (2), intestine (1), heart (1), and adrenal gland (1) (Table 1).

Fig. 1a,b.

Lung of ferret naturally infected by coronavirus. (a) Accumulation of macrophages, intermingled with lymphoplasmacytic cells, consituting histiocytic inflammation. HE. (b) Some macrophages show positive labelling for coronavirus antigen, consisting of a granular precipitate in the cytoplasm. IHC. Bars, 25 μm.

In the eight IHC-positive animals, the granulomatous lesions were variable. According to their cellular composition and distribution, the lesions were classified as: diffuse granulomatous inflammation on serosal surfaces; granulomas with areas of necrosis; granulomas without necrosis; granulomas with neutrophils.

Diffuse granulomatous inflammation on serosal surfaces was mainly observed in tissue from lymph nodes (5 animals) and intestine (3), and occasionally in kidney (1) and heart (1). It consisted of a moderate-to-severe inflammatory infiltrate composed mainly of macrophages, with a few lymphoplasmacytic cells, accompanied by destruction of mesothelial cells and extension into the surrounding adipose tissue. In some cases, the serosal surfaces were covered with layers of precipitated exudate containing numerous small granulomas. In the lymph nodes, this exudate was generally accompanied by a fibroblastic proliferation; in the intestine, underlying muscle fibres and submucosa were occasionally affected, and in the heart the infiltration extended into large areas of the myocardium. Coronavirus antigen, restricted to a small number of infiltrating macrophages, was observed in most of these lesions.

Granulomas with areas of necrosis were restricted principally to serosa and the parenchyma of lymph nodes (4 animals). In one case this type of granuloma was found in the pancreatic parenchyma. A large area of central necrosis was surrounded by a small rim of macrophages and a thin layer of lymphoplasmacytic cells. In two lymph nodes (ferrets nos 2 and 6), patchy liquefactive necrosis was accompanied by small accumulations of cholesterol crystals and foamy macrophages. In most cases viral antigen was detected, but usually in only small numbers of macrophages.

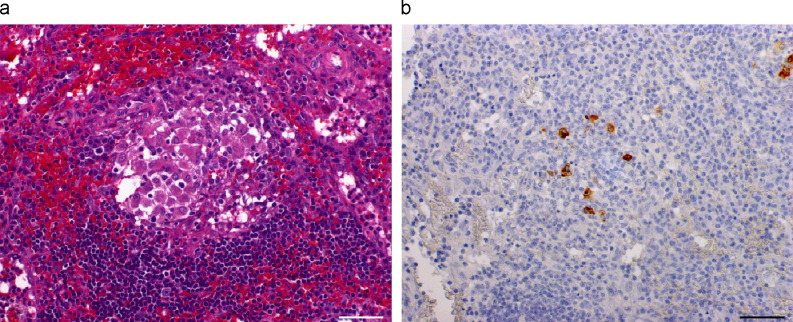

Granulomas without necrosis were observed in the spleen (3 animals), lymph nodes (2) lung (1), pancreas (1), Peyer's patches (1) and omentum (1). These granulomas were small, with a core of macrophages surrounded by a broad rim of lymphoplasmacytic cells (Fig. 2a ). Focal, moderate accumulations of connective tissue were observed in three tissue samples from spleen and one lung tissue sample. In the omentum, some of these granulomas were seen to be adjacent to vessels. In most of the granulomas, viral antigen was observed in a large number of macrophages (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2a,b.

Lymph node of ferret naturally infected by coronavirus. (a) Granuloma without necrosis, showing centre composed of macrophages surrounded by lymphoplasmacytic cells. HE. (b) Coronavirus antigen is present in some macrophages in the centre of the granuloma. IHC. Bars, 50 μm.

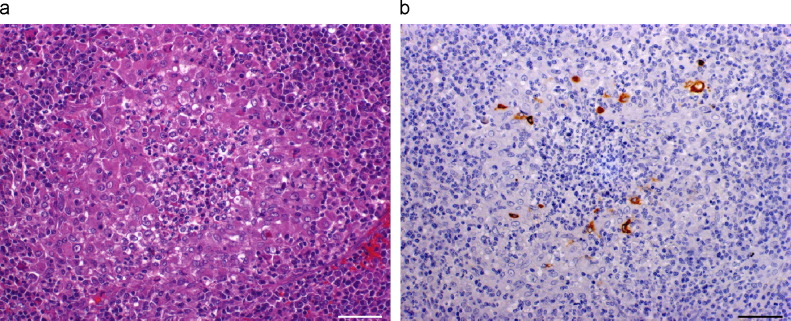

Granulomas with neutrophils were found in various organs including kidney (2 animals), spleen (1), lung (1), lymph node (1), liver (1), and adrenal gland (1). The centre of each granuloma contained a large accumulation of neutrophils, surrounded by a thick layer of macrophages and lymphoplasmacytic cells (Fig. 3a ). In the renal cortex and lungs, the granulomas were numerous and confluent. Numerous IHC-positive macrophages were seen in most of the lesions (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3a,b.

Spleen of ferret naturally infected by coronavirus. (a) Granuloma with neutrophils. Large accumulation of neutrophils in the centre, surrounded by a broad rim of macrophages and lymphoplasmacytic cells. HE. (b) Coronavirus antigen present in a moderate number of macrophages surrounding neutrophils. IHC. Bars, 50 μm.

Other lesions were observed less frequently. Granulomatous necrotizing vasculitis was seen within a diffuse granulomatous reaction in the serosa of one lymph node, and a few macrophages contained coronavirus antigen. In addition, focal perivascular lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates were detected in the omentum of the intestine, but no viral antigen was detected.

Finally, together with other granulomatous lesions in other organs, lung tissue showed evidence of endogenous lipid pneumonia in two ferrets (nos 1 and 5). It varied from mild, with a patchy subpleural distribution, to severe, with diffuse alveolar accumulation of cholesterol crystals and foamy macrophages, intermingled with normal macrophages, lymphoplasmacytic cells and fibrosis. Immunohistochemical labelling was positive in a small number of macrophages in the lesions of ferret 5.

No coronavirus antigen was detected in any tissue from ferret 4. However, the microscopical lesions seen in this animal were similar to those observed in the other eight ferrets, namely small granulomas without necrosis in the spleen and a diffuse granulomatous reaction on the serosa of the lymph node.

No evidence of other possible pathogenic agents was observed with Ziehl–Neelsen, PAS or Warthin–Starry stains.

Discussion

The FCV3-70 monoclonal antibody used to detect group 1 coronavirus antigen, and the criteria used to classify the granulomatous lesions, were basically the same as those previously used in cats (Kipar et al., 1998a). Eight of the nine ferrets showed coronavirus antigen in at least one of the tissues examined.

The histological lesions were closely similar to those described in cats with FIP, but three features merit comment. (1) The number of neutrophils among infiltrating cells in necrotizing lesions in cats have been found to vary greatly between studies (Kipar et al., 1998a; Berg et al., 2006), whereas when neutrophils occurred in the present study they were always abundant. As a result of this observation, a new granuloma category was established, namely granulomas with neutrophils. This suggests that neutrophils may have an important pathogenic role in ferrets. (2) Endogenous lipid pneumonia (alveolar histiocytosis) was observed in lung samples from two ferrets. Additionally, granulomatous inflammation with necrosis and lipid accumulation was seen in the lymph nodes of two other ferrets. In three of these four cases, IHC revealed viral antigen in macrophages associated with these lesions. Despite the small number of animals with such lesions, these observations may indicate that some ferrets have a natural predisposition to develop granulomatous lesions with accumulation of lipids, not necessarily associated with coronavirus infection. Consistent with this interpretation, endogenous lipid pneumonia has been related to a non-specific response to injury compounded by as yet unknown inherent species-dependent factors (Dungworth, 1993). (3) Granulomatous necrotizing vasculitis was observed less frequently than in cats. It is possible, however, that the granulomatous lesions were so extensive and severe in the ferrets that the vascular structures could not be detected.

The FCoV-like antigen distribution and the percentage of affected animals showing positive immunolabelling resembled these features as reported in cats with FIP, particularly with regard to necrotic granulomas, which usually showed a large area of necrosis, FCoV antigen being restricted to a few macrophages. Possibly, unlabelled macrophages contained only minimal amounts of virus, or reduced numbers of macrophages decreased the likelihood of detecting viral antigen (Kipar et al., 1998a).

It should be emphasized that, as in cats, the different types of lesion previously described and the viral antigen expression varied within the same animal and even within the same organ. It has been hypothesized that recurrent bouts of monocyte-associated viraemia with development of new lesions in each viraemic phase is responsible for this variation (Kipar et al., 2005). Such a hypothesis might explain the negative IHC results in ferret 4, in which lesions consistent with coronavirus infection were observed. In our opinion, because this animal had probably suffered previous bouts of coronavirus viraemia, the quantity of virus present was minimal in the final stage of the disease when the animal was killed. Studies on FIP suggested that the examination of many more granulomatous tissue sections might have revealed occasional antigen-positive macrophages in occasional granulomas.

In cats with FIP, coronavirus antigen has been demonstrated by immunofluorescence or immunohistochemistry (Pedersen and Boyle, 1980; Tammer et al., 1995). In the present study, the primary antibody used for IHC was FCV3-70, which is known to react with feline, canine, porcine and ferret coronaviruses (Kipar et al., 1998a, Kipar et al., 1998b; Williams et al., 2000). Canine and porcine coronavirus have not been reported to produce granulomatous lesions in heterologous species and FECV has been reported to produce epizootic catarrhal enteritis in only one such species, namely the ferret (Williams et al., 2000; Wise et al., 2006). There would seem to be three possible explanations for the presence of coronavirus antigen in the granulomatous lesions described in this report: an infection by FCoV; an infection by a mutated FECV (as in the case of FCoV in cats); or infection by an unknown coronavirus. Further research is therefore required to clarify the type of coronavirus responsible for the appearance of these lesions in ferrets.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Ms Blanca Pérez and Ms Aida Neira for expert technical assistance with histological processing. We also thank Carlos López from “Maragall Exotics Centre Veterinari” (Barcelona) for his collaboration. M. E. Kerans provided assistance with English usage.

References

- Berg A.L., Ekman K., Belak S., Berg M. Cellular composition and interferon-gamma expression of the local inflammatory response in feline infectious peritonitis (FIP) Veterinary Microbiology. 2006;111:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2005.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S.A. (2004). Basic anatomy, physiology, and husbandry, In: Ferrets, Rabbits, and Rodents Clinical Medicine and Surgery, Quesenberry, K.E., Carpenter, J.W. (Eds.), 3rd Edit., W.B. Saunders, Philadelphia, pp. 2–12.

- Dungworth, D.L. (1993). The respiratory system. In: Pathology of Domestic Animals, Jubb, K.V.F., Kennedy, P.C., Palmer, N. (Eds.), Vol. 2, 4th Edit., Academic Press, London, pp. 539–698.

- Hartmann K. Feline infectious peritonitis. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice. 2005;35:39–79. doi: 10.1016/j.cvsm.2004.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kipar A., Bellmann S., Kremendahl J., Kohler K., Reinacher M. Cellular composition, coronavirus antigen expression and production of specific antibodies in lesions in feline infectious peritonitis. Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology. 1998;65:243–257. doi: 10.1016/S0165-2427(98)00158-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kipar A., Kremendahl J., Addie D.D., Leukert W., Grant C.K., Reinacher M. Fatal enteritis associated with coronavirus infection in cats. Journal of Comparative Pathology. 1998;119:1–14. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9975(98)80067-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kipar A., May H., Menger S., Weber M., Leukert W., Reinacher M. Morphologic features and development of granulomatous vasculitis in feline infectious peritonitis. Veterinary Pathology. 2005;42:321–330. doi: 10.1354/vp.42-3-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez J., Ramis A.J., Reinacher M., Perpiñán D. Detection of feline infectious peritonitis virus-like antigen in ferrets. Veterinary Record. 2006;158:523. doi: 10.1136/vr.158.15.523-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen N.C., Boyle J.F. Immunologic phenomena in the effusive form of feline infectious peritonitis. American Journal of Veterinary Research. 1980;41:868–876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tammer R., Evensen O., Lutz H., Reinacher M. Immunohistological demonstration of feline infectious peritonitis virus antigen in paraffin-embedded tissues using feline ascites or murine monoclonal antibodies. Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology. 1995;49:177–182. doi: 10.1016/0165-2427(95)05459-J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wack, R.F. (2003). Felidae. In: Zoo and Wild Animal Medicine, Fowler, M.E., Miller, R.F. (Eds.), 2nd Edit., W.B. Saunders, Philadelphia, pp. 491–501.

- Williams B.H., Kiupel M., West K.H., Raymond J.T., Grant C.K., Glickman L.T. Coronavirus-associated epizootic catarrhal enteritis in ferrets. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2000;217:526–530. doi: 10.2460/javma.2000.217.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise A.G., Kiupel M., Maes R.K. Molecular characterization of a novel coronavirus associated with epizootic catarrhal enteritis (ECE) in ferrets. Virology. 2006;349:164–174. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.01.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]