Public health services are considered integral to homeland security and defense, and public health workers are at the forefront of emergency preparedness and response [1]. Anthrax threats and scares and the emergence of new infectious diseases such as West Nile virus, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), and avian influenza have put an increased focus on the essential functions of the country's public health infrastructure. Nurses make up the largest group of health care professionals who work in state and local public health departments across the nation [2] and provide a wide range of services. The new challenges for public health come at a time when there are fewer resources to support such efforts.

The increased need for public health services comes at a time when the current national public health infrastructure of 3000 local health departments has been weakened by years of financial and administrative neglect. There appears to be a lack of funding or political will to support population-based interventions for promoting health and preventing disease. The public health workforce is challenged to function as first responders (ie, the initial health care professionals who contact victims during a public health emergency) and to help rebuild the basic infrastructure necessary to protect the public's health. This article identifies issues in the role of public health nurses in bioterrorism preparedness.

Issues in preparing for bioterrorism

Lack of experience

Bioterrorism threatens national security when large, susceptible populations deliberately are exposed to highly virulent organisms that produce widespread illness. The ability of terrorists to disrupt health care services was seen when unsuspecting victims intentionally were exposed to anthrax in the United States in the fall of 2001. Before that time, anthrax had been considered as the exotic wool-sorters disease [3]. Multiple victims were exposed, and several agencies responded. The agencies were unable to delineate their roles and the responsibilities of each partner. There was not a clear understanding of the chain of command, how to communicate specialized knowledge, or communicate through the media to the general public. Public health officials had difficulty identifying the limits of their own knowledge, authority, and responsibility. In the midst of the chaos, public health nurses were asked to conduct communicable disease investigations, perform clinical tasks, administer mass medication clinics, and communicate with the worried well.

Terminology

The confusion regarding bioterrorism is caused somewhat by terminology. Terms such as disasters, mass casualty incidents, terrorism, and bioterrorism sometimes are used interchangeably. Although there are similarities between the four terms, there are important differences, and Table 1 provides an overview. Veenema describes a disaster as an event that occurs suddenly, causes damage that exceeds the capacity of the responders, and requires outside help. The causes of a disaster are described as nature, equipment malfunction, human error, biological hazards, and disease [4].

Table 1.

Comparison of terms related to bioterrorism

| Term | Caused by | Characteristics | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disaster [4] Sudden event | Nature | Exceeds capacity | Earthquake, floods, fire, hurricane |

| Equipment failure | Causes damage | Hazardous materials spill | |

| Human error | Ecological | Air crash | |

| Biological hazard | Loss of life | Epidemic | |

| Disease | Civil strife | ||

| Mass Casualty [5] Single event | Natural forces | Significant disruption of health and safety | Hurricane, tornado |

| Infrastructure failure | Exceeds capability | Plane crash | |

| Conduct of people | Power outage | ||

| Terrorist attack | |||

| Act of war | |||

| Terrorism [1] Violence, force | Political motivation | Overwhelms capacity | May involve weapons of mass destruction (CBRNE) |

| Against civilians | Cyber-terrorism, agro-terrorism and eco terrorism | ||

| Instills fear | |||

| Crime | |||

| Bioterrorism [1] Violence, force—may emerge slowly | Political motivation | Against civilians | Bioagents |

| Instill fear | |||

| Crime | |||

The International Nursing Coalition for Mass Casualty Education (INCMCE) was “organized to facilitate the systematic development of sustainable and scalable educational policies related to mass casualty events” [5]. INCMCE emphasizes that a mass casualty event exceeds the day-to-day operational ability of the local responders and compels planners to provide for surge capacity [5].

Terrorism has additional dimensions not specifically seen in the definitions of disaster and mass casualty incidents. Levy and Sidel [1] emphasize that terrorism is politically motivated and intentionally directed toward civilians. Terrorists use the threat or actual act of violence, such as biological, chemical, incendiary, explosive, or nuclear agents as a weapon to instill fear. Bioterrorism frequently is used colloquially to describe all weapons of mass destruction (WMD), which sometimes are referred to as chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, and explosive (CBRNE) or biological, nuclear, incendiary, chemical, and explosive (BNICE).

Nature of bioterrorism

The nature of a bioterrorist event is like other types of terrorist events in intent but different in terms of agent and timing of events. Bioterrorism creates real or potential victims in a civilian population who fear contracting or dying from a serious communicable disease [1]. The most effective bioterrorism agent is a biological organism that is highly communicable from person to person and can cause high morbidity and mortality. Infectious diseases caused by a bioterrorist organism are not like a naturally occurring acute event (eg, varicella) that is relatively time-limited. Instead, an intentionally released agent will appear as an index case, then spread to close and secondary contacts over an extended period of time. It is the terrorist's intent is to instill anxiety during large outbreaks of disease and death that evolve slowly over time.

The role of public health nurses in bioterrorism

Public health nurses who work in a local or state health department are actively involved in all phases of planning, detecting, controlling and responding to an outbreak caused by a bioterrorist agent. Unlike most acute care clinicians who specialize in the care of certain disorders, the scope of the public health nurses' practice can extend from pre-disaster planning, to delivering care during an event, to post-disaster evaluation. Public health nurses are accustomed to handling outbreaks of communicable disease and routinely collaborate with other health care workers in primary care and hospital settings. If an incident is suspected bioterrorism, the case will involve working with local and federal law enforcement agencies conducting a criminal investigation. Bioterrorism will generate media coverage and a nationwide scare.

Local planning

Local public health departments should have an emergency management coordinator who is responsible for emergency and disaster planning. Local resources are necessary, because a community needs to be able to initiate and sustain its own local response for the first 48 hours following a disaster. It takes time to mobilize distant resources, and how a community responds within those first hours will affect the overall morbidity and mortality associated with the incident [6]. The local coordinator works with law enforcement, emergency management, medical care systems, and public health agencies to ensure a quick and comprehensive response can be provided until state and federal help arrives.

Public health agencies need established relationships with other local agencies to effectively plan and respond to an event. Common wisdom suggests that emergency preparedness partners do not want to meet for the first time while an actual bioterrorism event is unfolding. While working together, the agencies create plans, conduct exercises, and practice drills to build the trust and relationships that will be needed in the first hours and over the long term. Local agencies will need to be able to continue to work together post disaster to provide follow-up and remediation after state and federal agencies retreat from a community.

In order for a public health agency to fulfill its role in a bioterrorism event, whether it is in the lead, collaborative, or secondary/supportive role, all staff must be competent to carry out individual responsibilities [7]. Nurses represent the largest single professional group practicing public health, and they have considerable knowledge of resources in a local community. They are grounded in population-based health practice for individuals, families, groups, and communities. Public health nurses work within three sets of competencies to better prepare for their responsibilities.

Competencies

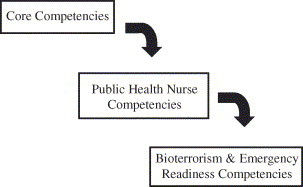

“A competency is a complex combination of knowledge, skills, and abilities demonstrated by organization members that are critical to the effective and efficient function of the organization” [7]. The three sets of competencies relevant to the public health nurse to prepare for bioterrorism and emergency preparedness are core competencies, public health nursing competencies, and specific bioterrorism and emergency preparedness competencies [7], [8], [9]. The bioterrorism competencies include specialty knowledge, skills, and attitudes that flow from the public health nursing competencies that flow from the original core competencies identified for all public health workers ( Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Competencies for bioterrorism and emergency readiness: public health nursing.

The Council on Linkages between Academia and Public Health Practice identified core competencies that encompass eight domains for all public health professionals, not just public health nurses. These domains of core competencies are:

-

•

Analytic assessment skills

-

•

Basic public health sciences

-

•

Cultural competency

-

•

Communications

-

•

Community dimensions of practice

-

•

Financial management

-

•

Leadership and systems thinking

-

•

Policy development/program planning

The Quad Council of Public Health Nursing Organizations is an alliance of four national nursing organizations that address public health nursing issues. The members include the Association of Community Health Nurse Educators, American Nurses Association, American Public Health Association Public Health Nursing Section, and the Association of State and Territorial Directors of Nursing. The council developed a list of public health nursing competencies that flowed from most of the domains identified within the original core competencies. Although most of the public health nurse competencies relate tangentially to bioterrorism and emergency preparedness, the most specific for public health nurses reads, “prepares and implements emergency response plan” [9].

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have endorsed competencies for public health clinical staff and defined the roles for public health nurses [7]. The purpose of the competencies is to assure workforce readiness for bioterrorism and emergency preparedness. The CDC also have established competency-based training in schools of public health through a network of centers for public health preparedness. The mission of the network, in partnership with state and local public health departments, is to provide training for the public health workforce. Competency-based training promotes the public health nurse's ability to master the behaviors necessary to execute the role in the event of an incident.

Roles for public health nursing

The specific role for public health nurses is defined by the bioterrorism and emergency competencies and by the agency preparedness plan where they are employed. Levy and Sidel [1] identified four overall roles for all health professionals in terrorism and public health. These are: (1) develop improved preparedness, (2) respond to the health consequences of terrorist acts and threats, (3) take action to prevent terrorism, and (4) promote a balance between response to terrorism and other public health concerns. These roles can be adapted to nurses working in state and local governmental public health settings by cross-walking with the competency sets.

Develop improved preparedness

Public health departments across the nation are organized around similar missions but have strategically different ways of functioning. These differences are based on structure, funding sources, and the leadership of the organization. Public health leaders set policy and direction and assume overall responsibility for assuring that their agency is prepared for bioterrorism. Public health nurses are active participants in writing, updating, reviewing, and exercising emergency response plans for their agencies. The plan establishes relationships with other partners involved in emergency response and addresses clinical protocols, surge capacity, and safety measures needed in the event of an actual occurrence [7].

A critical competency for all is knowledge of the chain of command. Public health professionals have adopted the incident command system used by the military, law enforcement, and fire fighters for use in bioterrorism and emergency preparedness. Also known as the incident management system, this system provides a common organizational structure and terminology, integrated communications, and consolidated action plans to protect life, property, and the environment [10].

The public health nurses' functional role is outlined in their agency's plan. Nurses are expected to seek out training and identify key system resources to assure effective preparedness to meet the responsibilities identified in the plan. Staff nurses, supervisors, and nurse administrators are educated before an event to be better able to communicate accurate information to clients, media, the general public, and other health professionals. Continuing education about the clinical manifestations of biological agents can be obtained readily through print and online sources [11], [12], [13]. For example, the CDC has categorized biological agents according to accessibility, ease of use, potential for social disruption, morbidity, and mortality [11]. Category A, B. and C agents result in diseases not normally seen in everyday public health practice, and the very mention of names such as smallpox, anthrax, and plague raises grave concerns among the public. Nurses are among the most trusted and accessible of all health professionals. Therefore, family, friends, neighbors, patients, and clients frequently ask a nurse for health information about emerging infectious diseases and bioterrorism. The nurse can use or refer the lay public to fact sheets on biological agents that are available through the CDC [13]. The goal is to help the public to become educated, follow a rational response, and avoid false information that could cause panic.

Public health nurses are responsible for obtaining and sending biological and chemical specimens for laboratory analysis, and nurses need access to updated information. Biological analysis is coordinated through the national public health laboratory system, which was developed to promote effective working relationships between clinical and public health laboratories and to strengthen the country's ability to test for all types of biological agents. Each biosafety-level laboratory performs a different function [14], and clinicians must be aware of the different requirements for each type of agent and specimen.

In contrast, the chemical laboratory program is being developed across the nation, and testing for chemical metabolites associated with chemical terrorism is not as advanced as for biological agents. The chemical laboratory network consists of different levels of laboratories with roles similar to those for biological testing. In the case of a suspected terrorist event, chemical specimens would be considered as criminal and forensic evidence and would need to have a documented chain of custody. Public health agencies need education regarding creating a chain of custody, the forms to use, and how each agency retains its own written document to assure continuous accountability.

Respond to health consequences

The public health nurse's functional role in bioterrorism is outlined by each agency; however, a need remains to allow for creative problem solving and flexible thinking [5]. An act of bioterrorism is difficult to identify early, because biological agents cause diseases that present with symptoms similar to common illnesses such as influenza [11]. An astute physician or nurse will likely be the first to recognize an unusual illness. He or she will need to diagnose and quickly report suspected cases immediately to public health and law enforcement authorities.

Public health nurses are active in the epidemiology and surveillance functions of public health agencies and participate in disease outbreak investigations. Because nurses identify and interview persons potentially exposed to bioterrorism agents, they need to know the signs and symptoms of all suspected diseases. They will assess, triage, isolate, treat, and provide public health support for victims and responders [5]. Many plans call for public health nurses to staff mass clinics to dispense vaccines, antimicrobials, and antitoxins made available through local sources or the CDC's Strategic National Stockpile. Other plans deploy public health nurses to assist with shelters, schools, or places with other vulnerable populations.

In the event of a suspected bioterrorist event, a community can provide medical resources through the Modular Emergency Medical System (MEMS). The MEMS model directs people away from overcrowded emergency departments to satellite community-based centers that triage, treat, and give supportive care. The centers are called acute care centers and are designed to relieve the overcrowding of hospitals and other acute care clinics. The MEMS model includes neighborhood emergency help centers and a community outreach component. Public health nurses may be asked to staff the neighborhood emergency help centers and community outreach centers to triage, give prophylaxis, refer to resources, and give self-help information [15].

Regardless of the setting, the public health nurse must be competent to respond to the psychological impact of a bioterrorism event for the victims, the public, and the workers responding to the event [5]. The psychosocial impact was documented for the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks and the anthrax incidents that occurred later that same year [16]. Taintor states, “the mental health of the population is a prime target of terrorists” [17].

Bioterrorism response plans should include reviewing practitioners' teaching and counseling skills and how to help victims who need emotional support. Public health nurses work with vulnerable populations and are acquainted with children, families, and communities at high risk for psychosocial difficulties. In a disaster, even normal-functioning individuals may experience problems directly related to the disaster [18]. Nurses need to be able to recognize the signs and symptoms of human stress responses (ie, acute stress reactions or post-traumatic stress disorder), anxiety, depression, fear, and grief and be able to make referrals to the appropriate resources for care [19]. Nurses may be involved in more structured programs, such as critical incident stress management teams or become specifically trained in peer-to-peer counseling [20]. Nurses must be cautious not to overextend themselves and ignore their own physical and mental health needs. The excitement and adrenalin involved in the initial quick response is replaced by exhaustion over the long term. An incident of biological terrorism will require a sustained effort on the part of the public health workforce.

Take action to prevent terrorism

Public health agencies are responsible for ensuring the safety of the general public by preventing communicable diseases. Nurses routinely conduct screening activities and provide anti-infective medications and immunizations to susceptible populations. Although the ideal biological weapon is an organism that does not have a means of preventing or effective treatment, there are highly virulent agents that have been used, despite a vaccine being available. Smallpox would pose a significant threat to public health in the United States, because the general population is virtually unvaccinated and thus unprotected. The smallpox threat has received considerable national attention [21], and a major health care initiative was launched in late 2002 to vaccinate a core group of health care workers and emergency response personnel. The intent of vaccinating this group is to develop a work force that could respond to suspected cases.

Most nurses have limited or no clinical experience with the smallpox vaccine, its administration, and adverse reactions. As public health agencies develop smallpox preparedness plans, additional nurses will need to be vaccinated so they can administer the vaccine in massive vaccination clinics. All nurses are challenged to become familiar with the disease, the vaccine, and the method of administration as part of a nationwide smallpox preparation initiative.

Other potentially lethal diseases also have vaccines available. Anthrax can be prevented if vaccine is given pre-exposure. Unfortunately, the safety of the vaccine came into question after it was mandated for members of the US military, and there is ongoing research on the product [12].

Influenza vaccine seldom is considered as part of the bioterrorism and emergency preparedness prevention efforts; however, preventing the disease has added benefits. Illnesses caused by bioterrorism agents can present with signs and symptoms similar to influenza. Immunizations should be encouraged to reduce the background incidence of influenza that could mask the diagnosis and early identification of a more serious bioterrorist attack. Public health nurses currently conduct massive community influenza immunization clinics that contribute to developing the herd immunity of a population at risk.

A long-term goal for all health care clinicians to prevent bioterrorism is to reduce access to potential bioterrorist agents [1]. The security of public health and research laboratories has been strengthened since the anthrax events, and all health care providers should be aware of and follow the stringent federal guidelines and regulations for laboratory security [14]. Another long-term effort is to advocate for the control, reduction, and elimination of WMDs. Several countries, including the United States, have developed, produced, and tested biological weapons. The history of their use is a sobering chronicle of how science and technology can be counterproductive to the ideals of nursing and public health [1], [22].

Promote a balance

Public health nurses are on the front lines of delivering community-focused, population-based services. Daily, nurses find that they must balance several priorities and competing demands, such as undoing health disparities; providing care for the uninsured; and treating the chronic effects of obesity, tobacco, drugs, infectious diseases, violence, and injury control [22]. Now the new efforts to combat bioterrorism have presented a paradox for many clinicians.

The CDC, under the direction of national and state public health policy makers, has invested considerable resources into state and local health departments to improve bioterrorism preparedness. Money has been allocated to bolster the capacity for epidemiology, laboratory services, training, communications, and planning functions. The efforts to improve the infrastructure created for bioterrorism and emergency readiness already have shown their usefulness for response to other public health problems, such as West Nile virus, SARS, and other infectious disease outbreaks. Unfortunately, the new resources also have been viewed as a distraction from addressing other urgent problems that require the attention of public health. State and local health departments are subject to increased scrutiny by policy makers to use the money wisely to address bioterrorism and emergency preparedness [23] and must not risk using the new money to supplant funding in areas where support has been decreased. Public health providers will struggle with how to use the resulting products to support other aspects of population-based interventions without violating the original intent of the investment.

Public health nurses provide further balance to bioterrorism preparedness programs by evaluating the effectiveness, accessibility, and quality of public health services [24]. Well-designed studies are needed to test a plan, clarify the nurse's role, improve coordination and communication, identify gaps in resources, and provide an opportunity for improvement. One study [25] evaluated emergency preparedness training and perceived barriers for public health nurses to work during a public health emergency. The study concluded that the training was useful; however, nurses needed to better balance their personal and professional lives and to develop disaster plans for their home, family, workplace and community. Anyone can become a disaster victim and will have to face competing personal and professional responsibilities [25], [26]. Resources, such as the American Red Cross and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), have made information easily available for individuals to access and tailor for their own personal preparation for any kind of disaster.

Summary

Recent terrorist events in the United States have accentuated the role of public health nurses as first responders in bioterrorism incidents. Diseases caused by a bioterrorist agent are not likely to be detected and will evolve slowly over time, taxing the resources of local public health agencies. Because their role is competency-based, public health nurses participate in disease prevention efforts, such as providing immunizations, identifying new cases by signs and symptoms, and participating in disease investigations. If a bioterrorism event is suspected, nurses work within agency plans and established chains of command to staff outreach sites, conduct mass clinics, promote responsible communications, and provide teaching and psychosocial support. Nurses also continually re-evaluate their role and performance by participating in exercises and drills, and they extend the planning to their personal lives also.

Footnotes

This project was supported under a cooperative agreement from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention through the Association of Schools of Public Health (ASPH). Grant Number A1023-21/21.

References

- 1.Levy B.S., Sidel V.W. Challenges that terrorism poses to public health. In: Levy B.S., Sidel V.W., editors. Terrorism and public health, a balanced approach to strengthening systems and protecting people. Oxford University Press; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gebbie K.M. Holding society, and nursing, together. Am J Nurs. 2002;102:73. doi: 10.1097/00000446-200209000-00045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benenson A. 16th edition. American Public Health Association; Washington (DC): 1995. Control of communicable diseases manual. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Veenema T.G. Springer Publishing Company; New York: 2003. Disaster nursing and emergency preparedness for chemical biological and radiological terrorism and other hazards. [Google Scholar]

- 5.International Nursing Coalition for Mass Casualty Education. International nursing coalition for mass casualty education mission statement. Available from: http://www.mc.vanderbilt.edu/nursing/coalitions/INCMCE/missnstmnt.pdf-7.5KB. Accessed March 19, 2004.

- 6.Geberding J.L., Hughes J.M., Kooplan J.P. Bioterrorism preparedness and response: clinicians and public health agencies as essential partners. In: Henderson D., Inglesby T.V., O'Toole T., editors. Bioterrorism: guidelines for medical and public health management. AMA; Chicago: 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Columbia University School of Nursing Center for Health Policy . Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta (GA): 2002. Bioterrorism and emergency readiness competencies for all public health workers. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Council on Linkages Between Academia and Public Health Practice . Public Health Foundation; Washington (DC): 2001. Core competencies for public health professionals. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quad Council of Public Health Nursing Organizations. Core competencies for public health nurses, a project of the council on linkages between academia and public health practice funded by the Health Resources and Services Administration, 2003.

- 10.Johnson M. Incident management system local and state public health agencies. Proceedings of Michigan Department of Community Health training on incident management. Lansing (MI): Michigan Department of Community Health; 2002.

- 11.Weinstein R.S., Alibek K. Thieme Medical; New York: 2003. Biological and chemical terrorism, a guide for healthcare providers and first responders. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henderson D., Inglesby T., O'Toole T. American Medical Association; Chicago: 2002. Bioterrorism guidelines for medical and public health management. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Bioterrorism agents/diseases. Available from: http://www.bt.cdc.gov/agent/agentlist.asp. Accessed March 20, 2004.

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Laboratory security and emergency response guidance for laboratories working with select agents. MMWR. 2002;51(No. RR-19) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Church J, Skidmore S. Modular emergency medical system (MEMS): how's it going? Proceedings of Michigan Department of Community Health, Office of Public Health Preparedness on Challenging our Assumptions. Lansing (MI): Michigan Department of Community Health; 2003.

- 16.Allds M, Ludwick R. One year later: the impact and aftermath of September 11. Available at: http://www.nursingworld.org/ojin/topic19/tpc19lnx.htm. Accessed September 18, 2003.

- 17.Taintor Z. Addressing mental health needs. In: Levy B.S., Sidel V.W., editors. Terrorism and public health: a balanced approach to strengthening systems and protecting people. Oxford University Press, Incorporated; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gordon N.S., Farberow N.L., Maida C.A. Taylor & Francis; Philadelphia: 1999. Children and disasters. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haggerty B, Williams RA. Psychosocial issues related to bioterrorism for nurses subcompetencies. Presented at the University of Michigan Academic Center for Public Health Preparedness. Ann Arbor (MI), September 15, 2003.

- 20.Antai-Otong D. Critical incident stress debriefing: a health promotion model for workplace violence. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2001;37:125. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6163.2001.tb00644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Addressing the smallpox threat: issues, strategies and tools. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/news/ulp/btbriefs/btbrief1.htm. Accessed March 16, 2004.

- 22.Berkowitz B. Public health nursing practice: aftermath of September 11, 2001. Online Journal of Issues in Nursing. 2002;7:11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frist B. Public health and national security: the critical role of increased federal support. Health Aff. 2002;21:117. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.6.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gebbie K.M. Emergency and disaster preparedness: core competencies for nurses: what every nurse should but may not know. Am J Nurs. 2002;102:46. doi: 10.1097/00000446-200201000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qureshi K., Merrill J., Gershon R. Emergency preparedness training for public health nurses: a pilot study. J Urban Health. 2002;79:413. doi: 10.1093/jurban/79.3.413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Silva M.C., Ludwick R. Ethics and terrorism: September 11, 2001, and its aftermath. Online Journal of Issues in Nursing. 2003;8:5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]