Abstract

Viral infections have been implicated as the cause of cardiomyopathy in several mammalian species. This study describes hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) and myocarditis associated with feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) infection in five cats aged between 1 and 4 years. Clinical manifestations included dyspnoea in four animals, one of which also exhibited restlessness. One animal showed only lethargy, anorexia and vomiting. Necropsy examination revealed marked cardiomegaly, marked left ventricular hypertrophy and pallor of the myocardium and epicardium in all animals. Microscopical and immunohistochemical examination showed multifocal infiltration of the myocardium with T lymphocytes and fewer macrophages, neutrophils and plasma cells. An intense immunoreaction for FIV antigen in the cytoplasm and nucleus of lymphocytes and the cytoplasm of some macrophages was observed via immunohistochemistry (IHC). IHC did not reveal the presence of antigen from feline calicivirus, coronavirus, feline leukaemia virus, feline parvovirus, Chlamydia spp. or Toxoplasma gondii. The results demonstrate the occurrence of FIV infection in inflammatory cells in the myocardium of five cats with myocarditis and HCM.

Keywords: feline immunodeficiency virus, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, immunohistochemistry, myocarditis

Viral infections have been suggested to be a possible cause of cardiomyopathy in various mammalian species (Barbaro et al., 1998, Badorff et al., 1999, Meurs et al., 2000, Yearley et al., 2006, Sani, 2008). Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) have been detected in myocarditis lesions in man and apes, respectively (Barbaro et al., 1998, Yearley et al., 2006, Pozzan et al., 2009). However, the ability of HIV to infect cardiomyocytes is surrounded by controversy, as the entry pathway of HIV into these cells has not been established, given that they do not express CD4 receptors (Barbaro et al., 2001, Currie and Boon, 2003). Moreover, it is likely that other factors also play a role in the aetiopathogenesis of HIV-induced heart lesions, such as opportunistic infections, the immune response to the viral infection, cardiotoxic drugs, malnutrition and prolonged immunosuppression (Sani, 2008).

Myocardial inflammation is often observed in systemic diseases, yet rarely does it manifest as primary changes in the heart. The possible causes of this condition include infection by Trypanosoma cruzi, Toxoplasma gondii, feline parvovirus (FPV), Bartonella henselae and, in some cases, opportunistic fungi (Maxie and Robinson, 2007, Varanat et al., 2012).

Feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) is a Lentivirus whose structure, replication cycle and pathogenesis are similar to those of HIV (Hosie et al., 2011). Infected cats are generally presented with lesions associated with immunodeficiency such as gingivostomatitis, chronic rhinitis, lymphadenopathy, immune-mediated glomerulonephritis and dermatitis, although some animals may not exhibit any lesions (Hosie et al., 2009; Hartmann, 2011). Thus far, FIV has not been associated with lesions in the cardiovascular system. This study describes myocarditis associated with FIV infection in five cats with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM). Virus was detected in cardiac lesions via immunohistochemistry (IHC). The myocarditis associated inflammatory infiltrate was characterized using cell markers for lymphocytes and macrophages.

The five cats were submitted for routine necropsy examination to the Department of Veterinary Pathology, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS), between 2010 and 2012. The cats had gross and microscopical changes consistent with HCM. Organ and tissue samples were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 24–48 h, then processed routinely and embedded in paraffin wax. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) and sections of myocardium were also stained by Grocott's methenamine silver and modified Brown–Hopps (Gram) protocols.

Tissue sections were subjected to IHC to detect the following pathogens: FIV, feline calicivirus (FCV), feline coronavirus, feline leukaemia virus (FeLV), FPV, Chlamydia spp. and T. gondii. The inflammatory infiltrate was also characterized by IHC using markers specific for CD3 (T lymphocytes), CD79 (B lymphocytes) and lysozyme (macrophages). The IHC protocols are described in Table 1 . Positive controls included previously tested samples that were assessed simultaneously with the test slides. Negative controls consisted of tissue samples incubated with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) instead of primary antibody. Anti-FIV IHC was also carried out on samples from every cat that presented with heart lesions during the period between 2010 and 2012.

Table 1.

Primary antibodies and immunohistochemical protocols applied in the study

| Antibody | Antigen retrieval | Dilution | Detection method | Chromogen |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monoclonal | ||||

| Mouse anti-feline immunodeficiency virus, p24 gag (AbD Serotec, Kidlington, UK) | 40 min, 100°C, 0.01 M citrate buffer pH 6.0 | 1 in 100 | LSAB-AP | PR |

| Mouse anti-feline calicivirus, FCV2-16 (Custom Monoclonals, Sacramento, California, USA) | 20 min, 37°C, P-XIV | 1 in 50 | MACH 4 | AEC |

| Mouse anti-coronavirus, FIPV3-70 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, Texas, USA) | 20 min, 100°C, 0.01 M citrate buffer pH 6.0 | 1 in 300 | LSAB-HRP | DAB |

| Mouse anti-feline leukaemia virus, gp 70 (AbD Serotec) | 40 min, 100°C, Tris–EDTA buffer pH 9.0 | 1 in 500 | LSAB-AP | PR |

| Mouse anti-feline/canine parvovirus (AbD Serotec) | 20 min, 37°C, P-XIV | 1 in 1,000 | LSAB-HRP | AEC |

| Mouse anti-Chlamydia spp., ACI (Fitzgerald Industries, Acton, Massachusetts, USA) | 5 min, 37°C P-K (ready to use) | 1 in 100 | LSAB-HRP | AEC |

| Mouse anti-CD79αcy, HN57 (Dako, Carpinteria, California, USA) | 20 min, 100°C, Tris–EDTA buffer pH 9.0 | 1 in 100 | LSAB-HRP | DAB |

| Polyclonal | ||||

| Goat anti-Toxoplasma gondii (VMRD, Pullman, Washington, USA) | 10 min, 37°C trypsin 0.1% and microwave (700 W), 2 min, 0.01 M citrate buffer, pH 6.0 | 1 in 1,000 | LSAB-HRP | DAB |

| Rabbit anti-human lysozyme, EC 3.2.1.17 (Dako) | 10 min, 37°C P-K | 1 in 200 | LSAB-HRP | DAB |

| Rabbit anti-human CD3 (Dako) | 20 min, 37°C P-XIV | 1 in 500 | LSAB-AP | PR |

P-XIV, protease XIV (Sigma); P-K, proteinase-K (Dako); LSAB-HRP, biotin–peroxidase–streptavidin (Dako); LSAB-AP, streptavidin–biotin–alkaline phosphatase (Dako); MACH 4, universal HRP-polymer (Biocare); AEC, 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole (Dako); DAB, 3, 3′ diaminobenzidine (Dako); PR, permanent red (Dako).

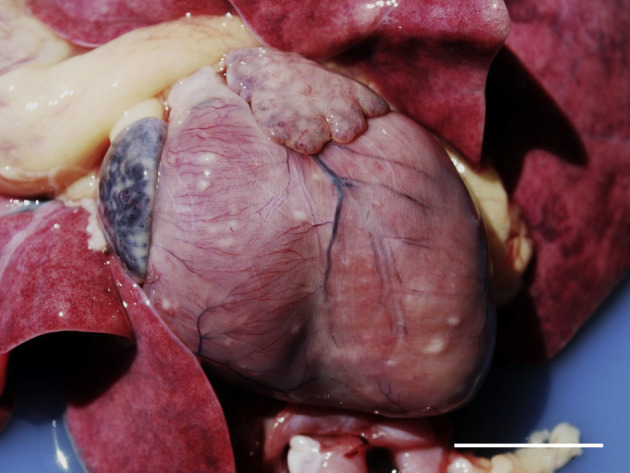

During the period between 2010 and 2012 there was a total of 358 feline necropsy examinations, among which 22 cases (6.1%) exhibited heart lesions. Sixteen cats (72.7%) were diagnosed only with HCM (without myocarditis), five (22.7%) had myocarditis and HCM and one (4.5%) had dilated cardiomyopathy. The breed, sex, age, clinical signs and gross lesions observed in the five cats with myocarditis and HCM are shown in Table 2 . Clinically, the majority of animals had dyspnoea (cats 1, 2, 3 and 5). One cat also exhibited restlessness (cat 2), while one only displayed lethargy and anorexia (cat 4) and suffered from vomiting. All of the animals died spontaneously and did not receive any treatment, except for cat 5 that was treated with antibiotics because of suspected pneumonia due to dyspnoea. Among the other 17 cats with heart lesions, 15 were of mixed breed and two were Persians, 11 were male and six were female and the average age was 6.2 years. At necropsy examination, all cases had marked cardiomegaly, accentuated concentric left ventricular hypertrophy and pallor of the myocardium and epicardium (Fig. 1, Fig. 2 ). Cat 3 had pericardial effusion containing fibrin strands. A thrombus in the right atrium was observed in cat 5. All of the animals had red, aerated lungs, which released large volumes of red fluid when sectioned. Hepatomegaly (cats 2 and 5) and blue-tinged (cats 3 and 5) or pale (cat 4) mucosae, in addition to hydrothorax (cats 3, 4 and 5), were also noted. The abdominal aorta of all animals was examined, but there was no evidence of thrombosis in any case.

Table 2.

Signalment, clinical presentation and gross post-mortem findings in cats of this study

| Cat number | Breed, age and sex | Clinical signs | Gross lesions (non-cardiac) | Cardiac lesions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Persian, 10 months, male | Dyspnoea | Lungs oedematous and heavy | Cardiomegaly, left ventricular hypertrophy, multifocal to coalescing white–tan areas in myocardium and epicardium |

| 2 | Persian, 4 years, male | Restlessness, dyspnoea | Lungs oedematous and heavy, liver enlarged and dark | Cardiomegaly, left ventricular hypertrophy, multifocal to coalescing white–tan areas in myocardium and epicardium |

| 3 | Crossbred, 3 years, female | Dyspnoea | Blue tongue and oral mucosae, moderate hydrothorax, lungs oedematous and heavy | Moderate pericardial effusion with fibrin. Irregular epicardial surface. Cardiomegaly, left ventricular hypertrophy, multifocal to coalescing white–tan areas in myocardium and epicardium |

| 4 | Crossbred, 1.5 years, male | Lethargy, anorexia, vomiting | Pale mucous membranes. Hydrothorax and ascites with fibrin. Lungs odematous and heavy | Cardiomegaly, left ventricular hypertrophy, myocardial pallor |

| 5 | Crossbred, 1 year, male | Dyspnoea | Blue oral mucosae. Cervical and thoracic vessels engorged. Moderate hydrothorax. Lungs oedematous and heavy. Liver enlarged and dark | Cardiomegaly, left ventricular hypertrophy, myocardial pallor, thrombus in right atrium |

Fig. 1.

Myocarditis and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in a cat infected with FIV. There is moderate cardiomegaly with pallor of the epicardium. Small white nodules are scattered over the epicardial surface. Bar, 3 cm.

Fig. 2.

Myocarditis and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in a cat infected with FIV. Cross-sections of different levels of the heart showing marked hypertrophy of the ventricular muscles, mainly in the left ventricle, with narrowing of the ventricular lumen. There is also myocardial pallor. Bar, 3 cm.

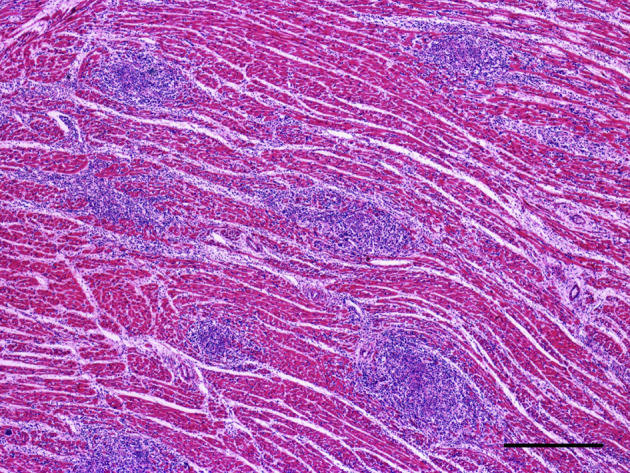

Histological examination revealed multifocal to coalescing areas of infiltration of the myocardium, consisting mainly of lymphocytes and, to a lesser extent, macrophages, neutrophils and plasma cells (Fig. 3 ). Variable amounts of loosely-packed connective tissue were observed between cardiomyocytes. Discrete to moderate caseous necrosis was also observed associated with the infiltrates. No fungal or bacterial structures were detected by Grocott's methenamine silver and modified Brown–Hopps (Gram) stains. However, diffuse and marked congestion and alveolar oedema was observed in the lungs of all cats. In cats 2 and 5 there was diffuse hepatic congestion. No microscopical lesions were observed in other organs.

Fig. 3.

Histopathological change in the heart of a cat infected with FIV and presenting with myocarditis and HCM. There is marked multifocal inflammatory infiltration. HE. Bar, 350 μm.

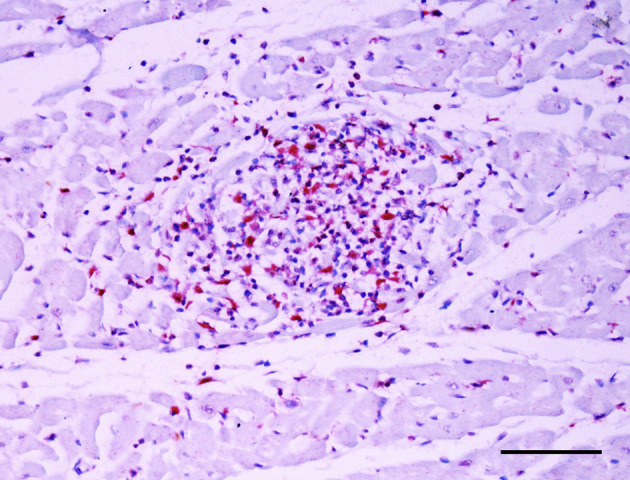

Anti-FIV IHC revealed immunoreaction in the cytoplasm and nucleus of infiltrating lymphocytes (and to a lesser extent within the cytoplasm of some macrophages) in all five cats (Fig. 4 ). The intensity of the immune reactivity of the samples is shown in Table 3 . An anti-FIV immunoreaction was also observed in the cytoplasm and nucleus of lymphocytes in the spleen, lymph nodes, liver and bone marrow of all cats. No immunoreaction was detected for FCV, feline coronavirus, FeLV, FPV, Chlamydia spp. or T. gondii. Immunoreaction for CD3 and CD79 was observed in the cytoplasm of T and of B lymphocytes, respectively. Anti-lysozyme IHC showed immunoreaction in the cytoplasm of macrophages and neutrophils. The intensity of these immunoreactions is shown in Table 3. No immunohistochemical labelling was observed in the other 16 cases of HCM or the case of dilated cardiomyopathy.

Fig. 4.

Immunoreaction for FIV antigen (red colour) in the cytoplasm of lymphocytes present in the myocardium. IHC. Bar, 100 μm.

Table 3.

Intensity of immunohistochemical labelling for FIV, CD3, lysozyme and CD79

| Cat number | FIV | CD3 | CD79 | Lysozyme in macrophages | Lysozyme in neutrophils |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ++ | ++ | − | + | ++ |

| 2 | +++ | +++ | − | + | +++ |

| 3 | ++ | ++ | − | + | + |

| 4 | + | ++ | − | + | +++ |

| 5 | +++ | +++ | − | ++ | + |

−, negative; +, mild; ++, moderate; +++, marked.

Evidence points to a viral aetiology of myocarditis (Barbaro et al., 1998, Badorff et al., 1999, Meurs et al., 2000, Yearley et al., 2006, Sani, 2008); however, the associated cell invasion and aetiopathogenic mechanisms have not been clarified (Barbaro et al., 1998, Barbaro et al., 2001, Currie and Boon, 2003, Yearley et al., 2006, Pozzan et al., 2009). The present study has shown the presence of FIV antigens in myocarditis lesions in cats. Previous studies have detected two other lentiviruses, HIV and SIV, in human and simian hearts with myocarditis, respectively (Barbaro et al., 1998, Yearley et al., 2006, Pozzan et al., 2009). FIV has also been associated with myopathy in adult cats (Podell et al., 1998) and HIV and SIV are similarly implicated in myopathy in man and simians, respectively (Dalakas et al., 1987, Chan et al., 2007).

In a study conducted in HIV patients, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) allowed the detection of HIV nucleic acid sequences in the heart tissue of 76% of patients with cardiomyopathy and in 57% of patients with myocarditis, suggesting that HIV acts directly in the myocardium, inducing myocarditis and dilated cardiomyopathy (Barbaro et al., 1998). However, a positive immunoreaction was observed in the dendritic and interstitial cells in only one case of myocarditis of undetermined cause (Pozzan et al., 2009). The comparatively higher rate of identification achieved using PCR may be related to the greater sensitivity of this technique. Here, the performance of IHC was satisfactory in that it afforded a good degree of sensitivity, with positive immunoreaction being observed in all cats with myocarditis.

FIV is considered to be endemic throughout the world. The virus is most commonly detected in adult male cats that are exposed to contact with other cats or that live in shelters, because the main route of infection is via biting (Hosie et al., 2009). In the present study, most of the sick animals that were examined (four out of five) were males; however, no information regarding the management of these cats or how frequently they were given access to the street was obtained.

The mean age of the cats in this study was 2.5 years, which is younger than the mean age of 4–6 years reported for FIV-positive cats presenting with clinical signs of immunodeficiency (Hosie et al., 2009). Nevertheless, the clinical signs and lesions observed in this study are not listed in classical descriptions of feline immunodeficiency (Hosie et al., 2009, Hartmann, 2011); instead, these signs and lesions are associated with different types of direct effects of FIV or inflammatory cells on the heart.

The heart lesions in these cats were classified as HCM due to the gross appearance of marked concentric hypertrophy, mainly in the left ventricle, with narrowing of the ventricular lumen. In a retrospective study on idiopathic feline cardiomyopathy, HCM was considered to be the main form of the condition, accounting for 57.5% of cases (Ferasin et al., 2003). Viral myocarditis may induce secondary cardiomyopathy, leading to heart failure, possibly due to morphological changes in the cytoskeleton (Meurs et al., 2000).

HCM is the most common cause of heart disease in cats (Maxie and Robinson, 2007), as observed in the present study (68.1%). However, the presence of FIV was only observed in cases associated with myocarditis, as none of the other hearts with cardiac lesions were positive for FIV antigen by IHC.

In this study, the inflammatory infiltrate involved T lymphocytes and macrophages. In a study of apes with myocarditis, IHC also revealed T lymphocytes and macrophages infiltrating the heart lesions. Similar to HIV and SIV, FIV infects helper T lymphocytes and macrophages in heart lesions. These cells play an important immunological role, assisting in both humoural and cell-mediated immunity (Hosie et al., 2009).

The present study identified FIV antigen in inflammatory cells in the hearts of cats with myocarditis and HCM. However, the specific relationship between FIV and myocarditis was not established. Further studies are required to explore the relationship between FIV, myocarditis and HCM in cats.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq).

References

- Badorff C., Lee G., Lamphear B.J., Martone M.E., Campbell K.P. Enteroviral protease 2A cleaves dystrophin: evidence of cytoskeletal disruption in an acquired cardiomyopathy. Nature. 1999;5:320–326. doi: 10.1038/6543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbaro G., di Lorenzo G., Grisorio B., Barbarini G. Incidence of dilated cardiomyopathy and detection of HIV in myocardial cells of HIV-positive patients. New England Journal of Medicine. 1998;339:1093–1099. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199810153391601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbaro G., Fisher S.D., Lipshultz S.E. Pathogenesis of HIV-associated cardiovascular complications. Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2001;1:115–124. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(01)00067-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan A.T., Kirton C., Estanislao L., Simpson D.M. Myopathy in HIV infection. In: Portegies P., Berger J.R., editors. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. 3rd Edit. Elsevier Saunders; Philadelphia: 2007. pp. 139–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie P.F., Boon N.A. Immunopathogenesis of HIV-related heart muscle disease: current perspectives. AIDS. 2003;17:21–28. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200304001-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalakas M.C., Gravell M., London W.T., Cunningham G., Sever J.L. Morphological changes of an inflammatory myopathy in rhesus monkeys with simian acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine. 1987;185:368–376. doi: 10.3181/00379727-185-42556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferasin L., Sturgess C.P., Cannon M.J., Caney S.M.A., Gruffydd-Jones T.J. Feline idiopathic cardiomyopathy: a retrospective study of 106 cats (1994–2001) Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. 2003;5:151–159. doi: 10.1016/S1098-612X(02)00133-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann K. Clinical aspects of feline immunodeficiency and feline leukemia virus infection. Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology. 2011;143:190–201. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosie M.J., Addie D., Bélak S., Boucraut-Baralon C., Egbering H. Feline immunodeficiency ABCD guidelines on prevention and management. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. 2009;11:575–584. doi: 10.1016/j.jfms.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxie M.G., Robinson W.F. Cardiovascular system. In: Maxie M.G., editor. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals. 3rd Edit. Elsevier Saunders; Philadelphia: 2007. pp. 1–106. [Google Scholar]

- Meurs K.M., Fox P.R., Magnon A.L., Liu S.K., Towbin J.A. Molecular screening by polymerase chain reaction detects panleukopenia virus DNA in formalin-fixed hearts from cats with idiopathic cardiomyopathy and myocarditis. Cardiovascular Pathology. 2000;9:119–126. doi: 10.1016/S1054-8807(00)00031-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podell M., Chen E., Shelton G.D. Feline immunodeficiency virus associated myopathy in the adult cat. Muscle and Nerve. 1998;21:1680–1685. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4598(199812)21:12<1680::aid-mus9>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozzan G., Pagliari C., Tuon F.F., Takanura C.F., Kaufmann M.R. Diffuse-regressive alterations and apoptosis of myocytes: possible causes of myocardial dysfunction in HIV-related cardiomyopathy. International Journal of Cardiology. 2009;132:90–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.10.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sani M.U. Myocardial disease in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection: a review. Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift. 2008;4:77–87. doi: 10.1007/s00508-008-0935-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varanat M., Broadhurst J., Linder K.E., Maggi R.G., Breitschwerdt E.B. Identification of Bartonella henselae in 2 cats with pyogranulomatous myocarditis and diaphragmatic myositis. Veterinary Pathology. 2012;49:608–611. doi: 10.1177/0300985811404709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yearley J.H., Pearson C., Carville A., Shannon R.P., Mansfield K.G. SIV-associated myocarditis: viral and cellular correlates of inflammation severity. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses. 2006;22:529–540. doi: 10.1089/aid.2006.22.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]