Abstract

Natural disasters, industrial accidents, terrorism attacks, and pandemics all have the capacity to result in large numbers of critically ill or injured patients. This supplement provides suggestions for all of those involved in a disaster or pandemic with multiple critically ill patients, including front-line clinicians, hospital administrators, professional societies, and public health or government officials. The current Task Force included a total of 100 participants from nine countries, comprised of clinicians and experts from a wide variety of disciplines. Comprehensive literature searches were conducted to identify studies upon which evidence-based recommendations could be made. No studies of sufficient quality were identified. Therefore, the panel developed expert-opinion-based suggestions that are presented in this supplement using a modified Delphi process. The ultimate aim of the supplement is to expand the focus beyond the walls of ICUs to provide recommendations for the management of all critically ill or injured adults and children resulting from a pandemic or disaster wherever that care may be provided. Considerations for the management of critically ill patients include clinical priorities and logistics (supplies, evacuation, and triage) as well as the key enablers (systems planning, business continuity, legal framework, and ethical considerations) that facilitate the provision of this care. The supplement also aims to illustrate how the concepts of mass critical care are integrated across the spectrum of surge events from conventional through contingency to crisis standards of care.

ABBREVIATION: CCTL, Critical Care Team Leader; CHEST, American College of Chest Physicians; HC/RHA, health-care coalition/regional health authority; IT, information technology; MCC, mass critical care; NGO, nongovernmental organization; Spo2, oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry; WHO, World Health Organization

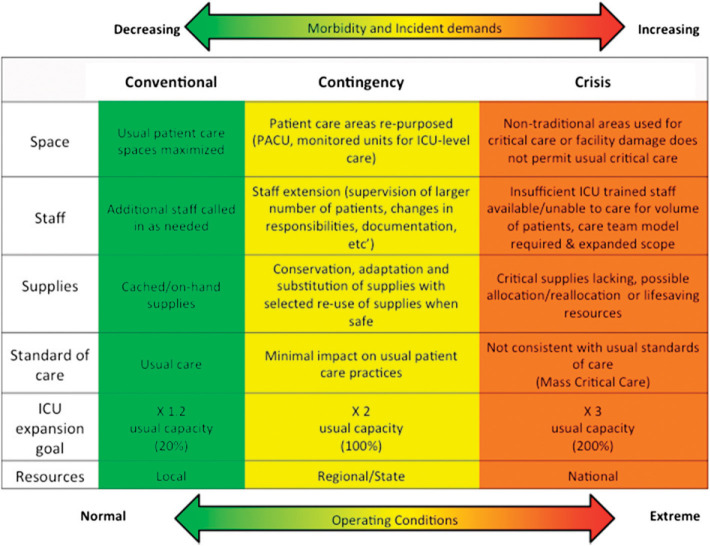

Natural disasters, industrial accidents, terrorism attacks, and pandemics all have the capacity to result in large numbers of critically ill or injured patients.1 Depending on their magnitude, the response to these surges may vary from a conventional response, where critically ill patients are managed with no significant alterations in standards or process of care, to a crisis response, where resource limitations dictate significant alterations in both standards and process of care to provide minimal basic critical care to the maximum number of patients (Fig 1 ).2, 3, 4, 5, 6 This supplement provides suggestions for all of those involved in a disaster or pandemic with multiple critically ill patients, including front-line clinicians, hospital administrators, professional societies, and public health or government officials. Although it is important for all providers to be familiar with the aspects of critical care disaster/pandemic management, Table 1 provides an overview of the suggestions of most interest to each of the groups.

Figure 1.

This figure depicts the spectrum of surge from minor through major. The magnitude of surge is illustrated by the alterations in the balance between demand (stick people) and supply (medication boxes). As surge increases, the demand-supply imbalance worsens. Conventional, contingency, and crisis responses are used to respond to the varying magnitude of surge. Varying response strategies are associated with each level of response. As the magnitude of the surge increases, the strategies used to cope with the response gradually depart from the usual standard of care (default defining the standards of disaster care) until such point that even with crisis care, critical care is no longer able to be provided.

TABLE 1.

Primary Audience For Suggestions

| Suggestion No. | Primary Target Audience | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinicians | Hospital Administrators | Public Health/Government | Medical Societies | |

| Surge capacity principles | ||||

| 1 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 2 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 3 | ✓ | |||

| 4a | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 4b | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 4c | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 5 | ✓ | |||

| 6 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 7 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 8a | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 8b | ✓ | |||

| 8c | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 9a | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 9b | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 10a | ✓ | |||

| 10b | ✓ | |||

| 10c | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Surge capacity logistics | ||||

| 1 | ✓ | |||

| 2 | ✓ | |||

| 3 | ✓ | |||

| 4 | ✓ | |||

| 5 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 6 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 7 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 8 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 9 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 10 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 11 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 12 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 13 | ✓ | |||

| 14 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 15 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 16 | ✓ | |||

| 17 | ✓ | |||

| 18 | ✓ | |||

| 19 | ✓ | |||

| 20 | ✓ | |||

| 21 | ✓ | |||

| 22 | ✓ | |||

| Evacuation of the ICU | ||||

| 1a | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 1b | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 2a | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 2b | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 2c | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 3a | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 3b | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 3c | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 4a | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 4b | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 4c | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 4d | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 4e | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 5a | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 5b | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 6a | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 6b | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 7a | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 7b | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 8a | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 8b | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 8c | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 8d | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 9a | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 9b | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| i | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| ii | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| iii | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 9c | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 9d | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 10a | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 10b | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 10c | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 10d | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 11a | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 11b | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 12a | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 12b | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 12c | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 13a | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 13b | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 13c | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 13d | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Triage | ||||

| 1 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 2 | ✓ | |||

| 3 | ✓ | |||

| 4 | ✓ | |||

| 5 | ✓ | |||

| 6 | ✓ | |||

| 7 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 8 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 9 | ✓ | |||

| 10 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 11 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Special populations | ||||

| 1 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 2 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 3 | ✓ | |||

| 4 | ✓ | |||

| 5 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 6 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 7 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 8 | ✓ | |||

| 9 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 10a | ✓ | |||

| 10b | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 10c | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 11 | ✓ | |||

| 12 | ✓ | |||

| System level planning, coordination, and communication | ||||

| 1 | ✓ | |||

| 2 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 3 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 4 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 5 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 6 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 7 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 8 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Business and continuity of operations | ||||

| 1 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 2 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 3 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 4 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 5 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 6 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 7 | ✓ | |||

| 8 | ✓ | |||

| 9 | ✓ | |||

| 10 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 11 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 12 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 13 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 14 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 15 | ✓ | |||

| 16 | ✓ | |||

| 17 | ✓ | |||

| 18 | ✓ | |||

| Engagement and education | ||||

| 1 | ✓ | |||

| 2 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 3 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 4 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 5 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 6 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 7 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 8 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 9 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 10 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 11 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 12 | ✓ | |||

| 13 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 14 | ✓ | |||

| 15 | ✓ | |||

| 16 | ✓ | |||

| 17 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 18 | ✓ | |||

| 19 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 20 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 21 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 22 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 23 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Legal preparedness | ||||

| 1a | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 1b | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 1c | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 2 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 3a | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 3b | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 4 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Ethical considerations | ||||

| 1 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 2 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 3 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 4 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 5 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 6 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 7 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 8 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 9 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 10 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 11 | ✓ | |||

| 12 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 13 | ✓ | |||

| 14 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 15 | ✓ | |||

| 16 | ✓ | |||

| 17 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 18 | ✓ | |||

| 19 | ✓ | |||

| 20 | ✓ | |||

| 21 | ✓ | |||

| 22 | ✓ | |||

| 23 | ✓ | |||

In 2008, the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) Task Force on Mass Critical Care published its first series of disaster critical care suggestions.1, 5, 7, 8, 9 Their published document reflected their consensus deliberations and proposed suggestions regarding the care of critically ill and injured patients from disasters. The supplement was received enthusiastically by both the medical and broader public health communities, becoming the second most frequently downloaded supplement from CHEST's website, and papers from the supplement have been cited in 157 publications indexed on the Web of Science (http://thomsonreuters.com/web-of-science). The effort was timely, as many hospitals applied the suggestions to respond to regional crises related to the 2009 influenza A(H1N1) pandemic.10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 Several recent disasters have brought new learning since the original documents were published. Also, the 2008 documents had minimal direction for the management of pediatrics, trauma, subspecialty ICU populations, or critical care outside of developed countries. Consequently, the Task Force for Mass Critical Care was reconvened with an expanded scope and expertise to provide a rigorously developed set of usable guidelines to critical care providers responding to disasters or pandemics throughout the world.

The assumptions1 upon which the first Task Force suggestions were based remain largely unchanged. Since 2008, the world has coped with the 2009 A(H1N1) pandemic as well as a myriad of other events that have either resulted in or have had the potential to create large numbers of critically ill patients or disrupt existing regional critical care infrastructure: Japan earthquake/tsunami 2011,17 Buenos Aires train crash 2012, Brazil night club fire 2013, Boston marathon bombing 2013,18, 19 Spanish train crash 2013, super-storm Sandy,20, 21 and the Westgate mall attack 2013 Nairobi. The horizon is studded with potential pandemics, such as H7N922 and MERS CoV23; in addition, conflicts and regional instability increase the risk of conventional and chemical weapons attacks.24, 25, 26 Clearly, hospitals and clinicians still need to be prepared to manage large numbers of critically ill or injured patients.

Cognizant of the burgeoning experience since the 2008 supplement, the Task Force for Mass Critical Care reconvened in 2012 and 2013 to review, update, and expand the suggestions presented in the 2008 supplement. In this iteration we have made a number of attempts to bolster the expertise of the Task Force itself as well as used a more rigorous methodology to develop the suggestions (see the “Methodology” article by Ornelas et al27 in this consensus statement). The current Task Force included a total of 100 participants (14 content experts, 68 panelists, and 18 topic editors) from nine countries, comprising clinicians and experts from disciplines including critical care, surgery, trauma, burn, pulmonary medicine, internal medicine, military medicine, disaster medicine, infectious diseases, hospital medicine, ethics, law, and public health, representing a diverse number of professions caring for both the adult and pediatric populations. Members of the Task Force were drawn from 15 different professional societies and organizations.

Our methodology had to recognize that there is still a paucity of high-quality evidence upon which to develop evidence-based recommendations for Mass Critical Care. The Task Force met in Chicago, Illinois in June 2012 to develop key questions. We then conducted comprehensive literature searches to identify evidence that could be used to answer the questions and provide evidence-based “recommendations.” Although some relevant studies were identified, none of the studies provided a sufficient quality of evidence upon which to make recommendations; therefore, expert opinion was solicited to provide answers (“suggestions”) to the key questions. To improve the rigor of the expert opinion, a modified Delphi process was used following the structure and guidelines established by the CHEST Guidelines Oversight Committee.27 All participants developing the Task Force's suggestions (panelists and topic editors) were vetted through the CHEST conflict of interest policy.

The ultimate aim of the Task Force is to expand the focus to provide recommendations for the management of all critically ill adults and children resulting from a disaster or pandemic wherever that care may be provided, not solely the clinical management of critically ill patients within the walls of an ICU. Considerations for the management of critically ill patients include clinical priorities, logistics (supplies, evacuation, and triage), and the key enablers (systems planning, business continuity, legal framework, and ethical considerations) that facilitate the provision of this care. Finally, the supplement aims to illustrate how the concepts of mass critical care (MCC) are integrated across the spectrum of surge events from conventional through contingency to crisis standards of care (Figure 1, Figure 2 ).2

Figure 2.

A framework outlining the conventional, contingency, and crisis surge responses. PACU = postanesthesia care unit. (Adapted with permission from Hick et al.2)

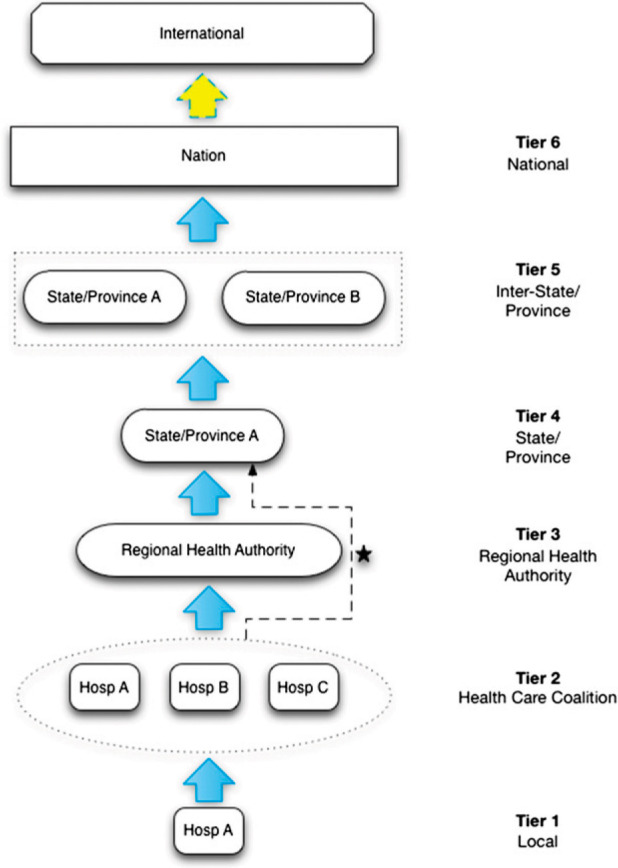

The primary context for the Task Force's suggestions remains health-care systems in the developed world. The language used throughout this supplement is not intended to refer to any one specific national context but rather should be viewed to be applicable in most large countries organized with a geographically based political structure incorporating a single national government with successive tiers of governments extending to local levels (Fig 3 ).28, 29 Because the audience for these suggestions is those in resource-rich settings in developed countries, the Task Force has separately addressed the issue of mass critical care in resource-poor settings and provides suggestions to improve the provision of care in this context by strengthening existing systems and leveraging strategic relationships with world bodies and organizations from developed countries.

Figure 3.

This figure illustrates the various tiers of authority involved in health-care surge response. Not all jurisdictions have Regional Health Authorities, in which cases Health Care Coalitions will work directly with the state/province. (Adapted with permission from Barbera et al.29)

Summary of Suggestions

We provide a summary of the suggestions from the 13 articles included in the supplement. Please refer to the appropriate article for a detailed discussion of the suggestions.

Surge Capacity Principles

Role of Critical Care in Disaster Planning

1. We suggest hospital and local/regional disaster committees include a critical care expert to optimize critical care surge capacity planning.

Surge Continuum: Conventional, Contingency, and Crisis Care

2. We suggest utilization of the existing framework for surge response that recognizes the shift in surge response across thresholds that distinguish conventional surge from contingency surge from crisis surge and delivery of crisis care is important in ensuring consistency in planning for critical care surge response.

Targets for Surge Response

3. We suggest in the presence of a slow onset, impending disaster/threat, targets for surge capacity and capability be focused, where possible, on projected patient loads.

4a. We suggest hospital critical care resources be able to expand immediately by at least 20% above the baseline ICU maximal capacity for a conventional response.

4b. In a contingency response, we suggest hospital critical care resources be able to expand rapidly by at least 100% above the baseline ICU capacity to meet patient demand using local and regional resources.

4c. We suggest hospital critical care resources be able to expand by at least 200% above baseline ICU capacity to meet patient demand in a crisis response using any combination of local, regional, national, and international resources.

5. We suggest more prolonged demands on critical care compared with the demands placed on other sections of the hospital (ie, days rather than hours) be taken into consideration when resuming routine hospital activities that may require ICU support.

Situational Awareness and Information Sharing

6. We suggest facilities, coalitions, and other components of the emergency response system, including those related to government entities, study how information about patients, events, and epidemiology are shared on a routine basis and during a major incident. Information technology (IT) should be leveraged to provide better indicators, more rapid alerting, and better patient data to facilitate decision-making.

7. We suggest the ability to provide dynamic forecasting of the functioning and sustainability of the supply chain be supported by hospitals.

Mitigating the Impact on Critical Care

8a. We suggest medically fragile patients be supported and protected by pre-event planning for ongoing medical support in the community to mitigate their reliance on hospital-based resources during a disaster event.

8b. We suggest local and regional authorities be responsible for integration of preventive community medical support in the plans to treat medically fragile patients during disasters.

8c. Given a situation where mitigation measures fail, medically fragile patients and victims of a disaster or pandemic should be given equal consideration for access to ICU resources.

Planning of Surge Capacity for Unique Populations

9a. We suggest regional planning include the expectation that the hospital be able to provide initial stabilization care to unique populations that they may not normally serve such as pediatrics, burn and trauma patients.

9b. We suggest access to regional expertise for care of all patients who require specialty critical care services including participation in the planning phase and access to just-in-time consultation for care coordination during a response.

Service Deescalation and Engineered Failure

10a. We suggest hospitals adopt a process of engineered systems cessation when the staff and/or material resources required for the ongoing critical care of a small number of patients could be used to save a greater number of lives.

10b. We suggest hospital cessation of the delivery of critical care services be considered if such endeavors are likely to entail significant personal risk to the treating team despite the availability of personal protective equipment and appropriate medical countermeasures.

10c. We suggest a hospital's decision to restrict or expand the delivery of critical care be made as part of a local/regional decision-making process with consultation and input provided by hospital ICU leadership.

Surge Capacity Logistics

Stockpiling of Equipment, Supplies, and Pharmaceuticals

1. We suggest hospital support services, including pharmacy, laboratory, radiology, respiratory therapy, and nutrition services, also be included in the planning of critical care surge.

2. We suggest equipment, supplies, and pharmaceutical stockpiles specific to the delivery of mass critical care (MCC) be interoperable and compatible at the regional level and ideally at the state/provincial level, so as to ensure uniformity of response capabilities, coordinated training, and a mechanism for exchange of material among facilities.

3. We suggest facilities should ensure adequate availability of disaster supplies through facility-based caches, with vendor agreements and understanding of supply chain resources and limitations.

4. We suggest the existing MCC hospital target lists for basic equipment, supplies, and pharmaceuticals remain relevant for institutions seeking to plan for MCC response.

5. We suggest regional and hospital stockpiles include equipment, supplies, and pharmaceuticals that can be used to accommodate the needs of unique populations that are likely to require critical care in centers other than specialty care centers, including pediatric, burn, and trauma patients.

Staff Preparation and Organization

6. We suggest hospitals use adaptive measures to compensate for reduced staffing, such as additional shifts, workload, and changes in shift structure/time, should be planned in collaboration with the critical care staff representatives.

7. We suggest hospital staff preparation for response to a disaster is vitally important to the successful outcomes of such events and should include emphasis on role definition, integration with the incident command system, and the ability to perform cross-trained functions.

8. We suggest hospital staff preparedness to support critical care surge response include knowledge of the following: standard operating procedures, role definition, use of hospital incident command system, cross-training of additional staff, and training in the use of situational awareness tools, particularly those that can assist in decision-making regarding critical care surge planning, operations, response, and recovery.

9. We suggest once a disaster or pandemic has occurred, hospitals should implement measures to mitigate preventable causes of staff shortage, including sheltering of staff and their families, provision of mental health support, measures to mitigate fatigue, access to transportation services, and maintenance of a safe working environment.

10. We suggest critical care nurse-to-patient ratios in an event requiring critical care surge be determined by provider experience, available support (ancillary staff), and clinical demands.

11. During a disaster or pandemic, we suggest critical care physician oversight and direction of the clinical care teams who provide critical care services, including scheduled patient assessment and treatment plan evaluation. If direct oversight is unavailable, a means of remote consultation should be used.

12. Should expert consultation (eg, pediatrics, trauma, burn, or critical care) not be available locally, we suggest every effort be made by hospitals to ensure that such expertise be provided at a minimum through remote consultation.

13. We suggest hospitals consider the utilization of technology (eg, telemedicine) as an important adjunct to the delivery of critical care services in a disaster to serve as a force multiplier to support response to disaster events. Where no such systems are currently in place, development of a telemedicine or other electronic platform to support patient care delivery is suggested.

Patient Flow and Distribution

14. We suggest decisions regarding in-hospital placement of critically ill patients during an MCC (after initial survey and treatment) be performed by an experienced clinician who makes similar triage decisions on a daily basis.

15. Early discharge of ICU patients to the general ward is a complex process, requiring critical care expertise. To enable rapid admission of critically ill patients to the ICU immediately after termination of ED/operating room workup and treatment, we suggest discharge of ICU patients (when possible) during preparation for an impending MCC be given priority simultaneous to decisions made about initial ED patient distribution.

Deployable Critical Care Services

16. We suggest deployable critical care services be considered a temporary alternative to critical care when loss of hospital infrastructure limits provision of critical care.

17. We suggest deployable critical care services are not definitive critical care facilities but may be used as a temporizing measure for delivery of critical care in a disaster setting. Expansion of critical care resources in the hospital environment, with temporary facilities for lesser acuity patients, is preferred over provision of deployable critical care when possible.

18. We suggest deployable critical care services may serve as temporary critical care locations provided there is a clear plan for patient transfer, within a few hours to days, to a definitive treatment location.

19. In crisis surge response, we suggest less intensive treatment of moderately injured patients be prioritized over the deployment of temporary critical care services when it would result in improved outcomes for larger numbers of patients.

Using Transportation Assets to Support Surge Response

20. We suggest surge capacity plans include predetermined standards that define minimal ongoing critical care capability in order to define the framework for decisions regarding patient transfer as the demands on the system gradually increase during a disaster or pandemic.

21. We suggest priority be given to transfer of assets to patients, particularly when transfer of patients to definitive care is limited by dangerous conditions (including considerable risk posed by available transportation options).

22. Transportation used for patient evacuations may also be used to bring in assets (eg, specialty providers and equipment), particularly when access/transport capacity is the limiting factor in patient movement.

Evacuation of the ICU

Form Hospital and Transport Agreements

1a. We suggest local and regional mutual-aid agreements should be established with other appropriately staffed and resourced hospitals to redistribute critically ill and injured patients from an evacuating hospital(s), and these agreements should be integrated within the framework of disaster preparedness plans.

1b. We suggest creation of predisaster formal agreements between hospitals and transport agencies or between Health Coalitions or Regional Health Authorities and transport agencies for air or ground transport of critically ill patients during a disaster.

Prepare for and Simulate Critical Care Evacuation

2a. We suggest staffing requirements within disaster plans should take into account the staffing resources necessary for desired surge capability to both safely move patients and to provide continuous care for patients remaining in the ICU.

2b. We suggest developing a detailed vertical evacuation plan using stairs when applicable for critically ill and injured patients.

2c. We suggest hospital exercises should simulate a mass critical care event and include vertical evacuation when applicable that evaluates (1) patient movement using specialized evacuation equipment and (2) the ability to maintain effective respiratory and hemodynamic support while moving down stairs.

Prepare for and Simulate Critical Care Transport

3a. We suggest specialized care is resource intensive, and specialized ground and aeromedical teams may be required to ensure appropriate initial and ongoing care prior to and during evacuation.

3b. We suggest preidentifying unique transport resources that are required for movement of specific populations, such as critically ill neonates, children, and technology-dependent patients, at a regional level. This information can then be used in real time to match allocated resources to patients.

3c. We suggest conducting detailed and realistic exercises that require ICU evacuation with local and regional ground and air transport agencies.

Designate a Critical Care Team Leader

4a. We suggest the Incident Management System at the evacuating ICU hospital should support early and frequent communication between Incident Command and a designated Critical Care Team Leader (CCTL) during an impending evacuation to provide close coordination and support of ICU evacuation preparations.

4b. We suggest the CCTL coordinating the critical care evacuation should be responsible for (1) categorizing ICU patients by ICU resource requirement and (2) communicating these ICU patient resource requirements with the Hospital Incident Command and to any Regional or National Emergency Command Center supporting hospital evacuation.

4c. We suggest when preparing for and during an ICU evacuation, a primary role of the CCTL should be to categorize each candidate ICU patient evacuee by (1) ICU resources required and (2) skill set of transport staff required.

4d. We suggest CCTLs and staff should receive special training, education, and practice on patient categorization and transport requirements.

4e. Expert providers from evacuation teams and outside facilities, when possible through face-to-face communication on site, can help ensure appropriate transport planning and distribution based on available resources during transport and in receiving facilities.

Initiate Pre-Event ICU Evacuation Plan

5a. If pre-event hospital evacuation of critically ill patients might be required, then we suggest planning for patient evacuation or shelter in place using an Incident Command System should begin as early as possible. Possible strategies include shelter in place, partial evacuation, or early evacuation, depending on the circumstances.

5b. We suggest Hospital Incident Command during a threatened hospital evacuation should have a clear and direct mechanism for communication with local governing bodies that control the timing and issuance of regional evacuation orders. To prevent obstruction of ground medical transport during hospital evacuation, coordination with local government regarding timing of recommendations for evacuation of the general population may be required. Efficient ground medical transport of patients during a hospital evacuation may be facilitated by providing a time period for hospital evacuation prior to recommendations for evacuation of the general population.

Requesting Assistance for Evacuation

6a. We suggest during a disaster or pandemic that overwhelms local and regional resources and requires large-scale hospital evacuations assistance, from national and/or international government medical support and evacuation agencies should be requested.

6b. We suggest the CCTL should be aware of the process for requesting evacuation assistance and the resources available at a regional and national level.

Ensure Adequate Power and Transport Ventilation Equipment

7a. We suggest surge ventilators with flexible electrical power and oxygen requirements should be available to support patients with respiratory failure that can maintain function while either (1) sheltering in place or (2) evacuating to an outside facility. These ventilators should be portable, run on alternating current power with battery backup, and have the ability to run on low-flow oxygen without a high-pressure gas source. Surge ventilators may be of limited capability but should be able to ventilate and oxygenate patients with acute lung injury or ARDS as well as airflow obstruction. This requires capability to deliver a high minute ventilation, high flow, and high positive end-expiratory pressure. They should be safe (disconnect alarm) and relatively easy for staff to operate.

7b. We suggest availability of adequate portable energy and medical gas flexible ventilators that can provide accurate small tidal volumes or pressure limits for the premature and neonatal patients expected at designated hospitals (for instance pediatric centers or hospitals with a neonatal ICU). Special consideration should be given to creating a standard, quickly accessible regional stockpile of mechanical ventilators for evacuation of neonatal patients as it may not be feasible for some nonpediatric centers to have adequate numbers of portable energy and gas flexible neonatal ventilators.

Prioritizing Critical Care Patients for Evacuation

8. We suggest evacuation order and identification of appropriate facility should be based on the following factors:

8a. In a time-limited evacuation, less critical patients can be evacuated faster and with fewer resources per patient and, thus, may be moved first in order to evacuate the most patients in the fastest time.

8b. When there is adequate time for evacuation, then more critically ill patients may be moved first and in parallel with less ill patients. Similar acuity patients often use similar transport resources and strain the same group of sending staff members. Thus, moving both the less critical and more critical patients simultaneously in parallel, as compared with sequentially in series (when there is adequate time to evacuate the entire hospital), may decrease the overall time to evacuation.

8c. In some situations, moving groups of similar-type patients to a single hospital entity may enable the sending hospital to provide staff to a single location to facilitate continuity of care and allow receiving hospitals to preplan to surge for specific types of patients and cluster disaster resources.

8d. The most critically ill patients dependent on mechanical devices for life support may, in some conditions, be safely cared for with a shelter-in-place strategy if it is deemed the risk of evacuation is too high.

Critical Care Patient Distribution

9a. We suggest during isolated, small, or pre-event ICU evacuations, CCTLs should coordinate with Hospital Incident Command and identify receiving hospitals for patient evacuation via the usual practice of provider-to-provider communication.

9b. We suggest during multiple-facility, large, or late ICU evacuations, the usual provider-to-provider system of communication for identification of receiving facilities should be augmented by other Regional or National Incident Management Systems.

9b.i. Every hospital should be specifically affiliated with (and drill evacuation with) a Regional or National Command Center for such events. Regional or National Command Centers may need to assume responsibility for designation of the receiving facilities for their patients.

9b.ii. We suggest when a Regional or National Emergency Command Center assumes responsibility for patient distribution, they should be responsible for identifying receiving facilities that match ICU patient resource requirements.

9b.iii. We suggest the Regional or National Emergency Command Center should enlist assistance of regional specialist experts to assist in the above matching process for distribution of patients requiring highly specialized care among receiving centers.

9c. We suggest assignment of transportation resources and lines of critical care patient evacuation should follow common existing referral patterns provided receiving facilities retain adequate capacity to care for these patients.

9d. We suggest patients who require advanced specialty care should be directed to high-volume centers and distribution take into account the capacity and resources required to provide ongoing care to these patients.

Preparing the Critical Care Patient for Evacuation

10a. We suggest standardized preparation of critically ill patients should be performed prior to hospital-to-hospital transfer, including initial stabilization, diagnostic procedures, damage control procedures, and medical interventions, to address anticipated physiologic changes during transport.

10b. We suggest the transport team should provide the equipment used for transport to ensure compatibility and familiarity during transport and retain important resources at the source institution for ongoing care of the remaining patients.

10c. We suggest evacuation planning and coordination should include the provision of additional expert providers, staff, and equipment to assist in the ongoing provision of care in situations where patient volume, acuity, or nature of illness or injury exceeds the capabilities of the CCTL and staff.

10d. We suggest utilizing a staging area for patients prepared and awaiting transport. This area should ideally be located near the point of embarkation and be staffed by medical personnel with training and experience in critical care evacuation. These personnel should be prepared to provide triage and perform ongoing medical care interventions prior to transport. The area should have the capability for additional surgical and medical stabilization pretransport if necessary.

Sending Critical Care Patient Information With Patient

11a. We suggest electronic transfer of patient information to the receiving hospital is optimal because a complete medical record can be included. Electronic transfer may be through an intranet or by copying patient information onto a USB flash memory drive or compact disk and transferring the information with the patient (see the “Business and Continuity of Operations” article in this consensus statement).

11b. We suggest a paper medical record be required to travel with the patient because there may be no ability to send an electronic copy of the medical record, or the receiving facility may not be able to read the electronic format of the medical record. A backup paper system may require (a) a printed copy of the electronic medical record or (b) a handwritten patient identification on a standardized patient tracking form. Any paper system should include basic patient identification, problem lists, and medications on forms that travel with the patient.

Transporting Critical Care Patients to Receiving Hospitals

12a. We suggest transportation methods should prioritize moving the greatest number of patients as rapidly and safely as possible to locations with adequate capacity and expertise where definitive care can be provided.

12b. We suggest local evacuation of highest acuity patients to hospitals with additional capacity by ground or rotary transport may be most appropriate to minimize risk and reduce ongoing critical care demands at the incident facility.

12c. We suggest alteration in the usual standards for modes of transport may be required during a disaster where transport resources are overwhelmed and evacuation and transport of critically ill patients to a receiving hospital ICU is required.

Tracking Critical Care Patients and Equipment

13a. We suggest tracking of patients should commence in the sending clinical unit, continue to the point of embarkation, and if possible, continue to the destination facility. Tracking of the patient and equipment should commence prior to being loaded onto the transportation. Minimum data sets for tracking should include the patient first and last name, date of birth, medical record number or tracking number or triage number, time leaving facility, transportation company name and transport vehicle number, and expected destination and next of kin.

13b. We suggest both the evacuating and receiving hospitals should track patients and equipment.

13c. We suggest tracking systems may be electronic or paper. In the event of complete power failure, however, a redundant paper system for tracking of patients and equipment should be performed by both sending and receiving hospitals, with communications provided to the sending hospital and/or a centralized coordinating center to confirm receipt of the patients.

13d. We suggest evacuation drills should test tracking of patients and equipment both by electronic and paper systems.

Triage

1. In the event of an incident with mass critical care casualties, we suggest all hospitals within a defined geographic/administrative region (eg, state), health authority, or health-care coalition should implement a uniform triage process and cooperate when critical care resources become scarce.

2. We suggest critical care only be rationed when resources have, or will shortly be, overwhelmed despite all efforts at augmentation and a regional-level authority that holds the legal authority and adequate situational awareness has declared an emergency and activated its mass critical care plan.

3. We suggest health-care systems provide oversight for any triage decisions made under their authority via activation of a mass critical care plan to ensure they comply with the prescribed process and include appropriate documentation.

4. We suggest health-care systems that have instituted a triage policy have a central process to update the triage protocol/system so that information that becomes available during an event informs the process in order to promote the most effective allocation of resources.

5. We suggest health-care systems establish in advance, a formal legal and systematic structure for triage in order to facilitate effective implementation of triage in the event of an overwhelming disaster.

6. We suggest health-care systems that have instituted a triage policy triage patients based on improved incremental survival rather than on a first-come, first-served basis when a substantial incremental survival difference favors the allocation of resources to another patient.

7. Triage officers:

7a. We suggest health-care systems that have instituted a triage policy have clinicians with critical care triage training function as triage officers (tertiary triage) to provide optimum allocation of resources.

7b. We suggest triage officers should have situational awareness at both a regional level and institutional level.

7c. We suggest in trauma or burn disasters, triage be carried out by triage officers who are senior surgeons/physicians with experience in trauma, burns, or critical care and experience in care of the age-group of the patient being triaged.

7d. We suggest in environments where triage is not usual, individual triage officers or teams consisting of a senior intensive care physician and an acute care physician be designated to make mass critical care triage decisions in accordance with previously prepared, publicly vetted, and widely disseminated guidelines.

7e. We suggest in limited resource settings in which there is a limited need for expansion of critical care resources, a continuation of well-established systems is appropriate.

8. We suggest triage protocols (clinical decision support systems), rather than clinical judgment alone, be used in triage whenever possible.

9. We suggest in health-care systems that have instituted a triage policy, technology such as baseline ultrasound, oxygen saturation as measured by pulse oximetry, mobile phone/Internet, and telemedicine be leveraged in triage where appropriate and available to augment clinical assessment in an effort to improve incremental survival and efficiency of resource allocation.

10. We suggest triage decision processes, whenever possible, provide for an appeals mechanism in case of deviation from an approved process (which may be a prospective or retrospective review) or a clinician request for reevaluation in light of novel or updated clinical information (prospective).

11. Triage process:

11a. We suggest tertiary-care triage protocols for use during a disaster that overwhelms or threatens to overwhelm resources be developed with inclusion and exclusion criteria.

11b. We suggest the inclusion criteria for admission to intensive care.

11c. We suggest patients who will have such a low probability of survival that significant benefit is unlikely be excluded from ICUs when resources are overwhelmed.

11d. We suggest consideration be given to excluding patient groups that have a life expectancy < 1 year.

11e. We suggest if a physiologic (nondisease-specific) outcome prediction score can be demonstrated to reliably predict mortality in a specified population upon screening for ICU admission, it is reasonable to use this to exclude admission for patients with a predicted mortality rate > 90%. Similarly if a disease-specific score can be demonstrated to reliably predict mortality when used in the same manner for patients with the disease, we suggest it is reasonable to use this to exclude admissions for patients with a predicted mortality rate of > 90%.

11f. We suggest each patient's condition be reassessed after a suitable time period (eg, 72 h) by the triage officer or triage team. If at that point the patient meets the criteria for exclusion from ICU, consideration should be given to withdrawal of therapy. If in the future a score is demonstrated to reliably predict high mortality when the patient is assessed during ICU stay, this should be used in preference to or as a supplement to clinical judgment.

Special Populations

Defining Special Populations for Mass Critical Care

1. We suggest the definition of special populations for mass critical care be those patients that may be at increased risk for morbidity and mortality outside a fully functional critical care environment or those patients that present unique challenges to providers when a full complement of supportive services is not available. We include the chronically ill and technologically dependent as the fragility of their baseline health puts them at significant risk for progression to a higher level of medical need.

Special Population Planning

2. We suggest critical care disaster planning include special populations.

3. We suggest professional societies, advocacy groups, governmental, and nongovernmental organizations be consulted when planning special population disaster preparedness and just-in-time care.

4. We suggest daily needs assessment of shelters include identification of those residents from special populations susceptible to decompensation to critical illness. A system to refer those identified to appropriate medical care should be in place.

5. We suggest disaster preparedness for special populations be part of their primary health-care maintenance. These patients should also be identified pre-event by their community (ie, nursing home facilities, health-care services, and social services providers) as an at-risk group for decompensation during a disaster and measures be taken to ensure they have a continuum of care during the event.

Planning for Access to Regionalized Services for Special Populations

6. We suggest identification of regionalized centers and establishment of communication be included in mass critical care planning.

7. We suggest regional specialized centers have mass disaster plans in place that include easily accessible, multidimensional, round-the-clock expertise available for consultation by local providers during mass critical care events.

8. Some special populations of mass critical care may require early transfer to specialized centers to maximize outcomes so should be identified early.

Triage and Resource Allocation of Special Populations

9. We suggest triage and resource allocation of special populations adhere to the same resource allocation strategy and process as the general population.

Therapeutic Considerations

10a. We suggest local, regional, and national critical care pharmacists and resources be identified during disaster preparedness.

10b. We suggest access to critical care or specialist pharmacist and resources include consideration for special populations such as those with burns, cirrhosis, organ transplant, and need for dialysis.

10c. We suggest pharmacists, especially those with critical care and specialty training, be an integral part of any mass critical care disaster team.

Crisis Standards of Care for Special Populations

11. We suggest research be conducted in crisis standard of care triggers for special populations that includes clinical, planning, and ethical domains across the life cycle of a disaster.

12. We suggest experts in the care of technology- and resource-dependent special populations convene to discuss and determine the acceptable parameters for crisis standards of care for a disaster.

System-Level Planning, Coordination, and Communication

National Government Support of Health-care Coalitions/Regional Health Authorities—Policy

1a. We suggest political leadership at national levels should support health-care preparedness through financial assistance, support of market driven incentives, and preparedness requirements to health-care coalitions/regional health authorities (HC/RHAs).

1b. We suggest national governments should support the development of responsive and nimble disaster/pandemic research processes that can both organize and assess information from prior disasters/pandemics, acquire real-time data in an ongoing one to provide situational awareness, and which can also learn from and support international disaster relief efforts.

1c. We suggest national, state/province/regional, and city/district governments should:

• Working with health-care experts and leadership, develop formal legal disaster/pandemic activation mechanisms to initiate, implement, and support disaster/pandemic plans and standards of care for HC/RHAs and health-care professionals; and legally initiate step down termination procedures and processes as conditions and criteria warrant in the recovery phase

• Work with health-care experts and leadership in the greater health-care community to develop and refine specific “trigger” criteria for formal legal activation and step down termination procedures and processes of disaster/pandemic plans and standards of care.

1d. We suggest local governments and government agencies should be formal partners in their local health-care coalition(s), and be actively engaged with their ongoing preparedness and response activities.

Teamwork Within HC/RHAs—Foundational Principles

2. We suggest health-care coalition partners should work together, with the following objectives:

2a. HC/RHA clinical and administrative leaders from all partners meet together on a routine, scheduled basis. Clinician leaders must include critical care medicine experts.

2b. HC/RHA clinical and administrative leaders from all partners work together at least yearly with primary focus on developing and updating joint disaster/pandemic preparedness plans based on likely events (Hazard Vulnerability Analyses).

2c. HC/RHA clinical and administrative leaders from all partners jointly practice activation and implementation of disaster/pandemic plans and standards of care through exercises.

2d. HC/RHA partners activate their communication and collaboration mechanisms for virtually all actual or potential surge events, or unusual or large scale planned or unplanned events requiring cooperation, to ensure optimal responses and enable experience working together.

2e. HC/RHAs identify clinical experts to oversee and address the needs of specific populations, especially pediatrics, and also specialty populations such as trauma, burns, oncologic, etc.

2f. HC/RHA clinical and administrative leadership should be defined by position, not specific personnel, consistent with Incident Command System (ICS) nomenclature or equivalent, and designed with appropriate redundancy.

Systems-Level Communication—Foundational Principles

3a. We suggest HC/RHAs should have secure online and/or published directories for all partners' clinical and administrative leadership, with emergency contact information (phone numbers, e-mail addresses, pagers, cell phone texting preferences, other means) and current call schedules.

3b. We suggest HC/RHA's should have defined communication vehicles which may include (but are not limited to): dedicated secure health-care coalition web sites; conference call lines and teleconferencing technologies (eg, Skype, others); hospital phones (land lines and cell phones); pagers, hand held walkie-talkies, ham radios, or other similar means of communication; telemedicine technologies, such as E-ICU, integrated into their disaster plans.

3c. We suggest HC/RHA partners should attempt to routinely use those agreed upon communication vehicles when working together.

3d. We suggest all agreed upon communication vehicles should be tested on a scheduled basis, with objective criteria to validate the test.

3e. We suggest the choice of communication vehicles and testing may be based on likely disaster/pandemic events (Hazard Vulnerability Analyses), and/or other appropriate considerations.

3f. We suggest developing defined disaster/pandemic plans for monitoring and leveraging popular social media (eg, Twitter, Facebook, others) during all actual or potential surge events, or unusual or large scale planned or unplanned events requiring cooperation, as both a means for gathering and transmitting information, as appropriate.

3g. We suggest HC/RHAs should have defined communication tools designated for each level of organizational leadership, which should be consistent with ICS structure or equivalent.

System-Level Surge Capacity and Capability

4a. We suggest HC/RHA surge objectives should be consistent with individual hospital surge goals and include the capability to surge to:

• Up to 200% above routine maximal capacity based on the nature and severity of the disaster (contingency to crisis)

• Up to the limit of the total number of ventilators available to coalition partners.

• Up to projected patient loads in a slow onset, slow evolving disaster.

4b. We suggest HC/RHAs should be able to monitor and track their defined surge capacity supplies and equipment, ideally “real-time” and electronically, with the intent of being able to use all HC/RHA assets. These supplies and equipment may include identified caches of important medications or equipment, and bed availability among partners.

4c. We suggest HC/RHAs should have the ability to track the number of available ICU capable personnel (“force multipliers”) and other designated specialist “resources” (eg, pediatric and special populations) through their partner hospitals. Partners with telemedicine capability (such as tele-ICU's) should have plans for how to use this resource to optimize the use of pediatric and specialty expertise across hospitals served by the telemedicine resource.

4d. We suggest HC/RHAs should have defined policies and procedures for emergency privileging for all health-care professionals designated as coalition resources.

4e. We suggest fair and adequate reimbursement for expenditures and loss of revenue related to delivery of acute critical care services during a disaster or pandemic must be ensured. This should include the guarantee of payments from governmental sources, as well as by insurance companies and other payers of health-care services.

Pediatric Patients and Specialty Populations

5a. We suggest HC/RHAs have identified, and be familiar with, the following pediatric disaster/pandemic designated resources including, but not limited to:

• Pediatric consultative specialists available by dedicated phone line support and/or dedicated video or telemedicine consultation.

• Designated pediatric surge personnel (eg, pediatric hospitalists, others) available to non-pediatric hospitals and health systems to support surge in contingency or crisis level events, with a defined plan for how to activate this resource when needed.

• Identified pediatric capable transport resources for allocation and matching of pediatric patients to available HC/RHA pediatric resources.

• Knowledge of available key supplies, medications, and other pediatric assets; location of these assets with a defined process for how they may be accessed urgently; and ability to monitor when asset reserves fall below a defined critical threshold.

• Pediatric educational resources. If web-based, they should be found on HC/RHA websites, or with links to appropriate resources. If published, resources should be readily available to all partners.

5b. We suggest HC/RHAs should have plans to provide care for specialty populations routinely found in their catchment area or region in parallel as described for pediatrics. Resources should include consultative services, potential surge personnel, transport resources, specialty supplies/medications, and educational resources. These populations include but are not limited to trauma, nephrology, burns, oncologic patients.

5c. Health-care coalitions, health systems, and hospitals identify patients with high-level chronic disease care needs, such as a home ventilator, home oxygen, chronic dialysis, and work to ensure their needs are met at home to help prevent these patients from having to seek assistance at hospitals.

HC/RHAs and Networks

6a. We suggest during a disaster requiring transfer of patients, whether from emergency medicine departments or inpatient areas, transferring partners may have initial choice of where patients are referred based on traditional referral patterns. However, HC/RHA leadership must oversee this process, and be able to intercede as both a resource and with the authority to redirect transfers based on anticipated or actual events. Defined health-care coalition coordination processes and transfer resources should be planned and identified ahead of time.

6b. Health-care coalitions should designate neighboring health-care coalitions as potential partners during a contingency or crisis event, and have readily available leadership contact information, and knowledge of these potential partners' size and capabilities.

Models of Advanced Regional Care Systems

7. Advanced Regional Care Systems instituted within large hospitals, and across hospitals, health systems and HC/RHAs, will have the greatest chance for success if they are established with the following goals:

• Clear and transparent objectives for what those programs are to accomplish, and the programs are well integrated and accepted across their hospital and health system partners.

• Have administrative and financial resources sufficient to support the objectives desired

• Are evaluated based on objective outcome measures and best-practice process indicators, and strive for consistent data definitions and goals, which facilitate outcome comparison with other systems.

• Are driven by an impassioned performance improvement culture.

• Have effective communication systems and processes across their hospitals, health systems, and health-care coalitions/regional health authority partners, between potential pre- and post-hospital partners, and with patients and families.

• Develop clear expectations and supportive clinical and educational resources for patients and their families, especially those patients with chronic medical illnesses.

The Use of Simulation for Preparedness and Planning

8. We suggest hospitals, health systems, and HC/RHAs promote the use of computer modeling to gain insight into their operational capabilities and limitations, in the following ways:

• Support the creation of computer models utilizing industry templates in collaboration with their own administrative, clinical, and technical resource experts from participating system partners. Models should include government and military resources when applicable, and include provision of maintenance of chronically ill patient populations.

• Collaborate with modelers in the design, implementation, and testing of these models; and with the interpretation and application of these results.

• Support the data requirements for such system models, and develop repositories for operationally relevant data that can be used in future modeling efforts.

• Leverage their relationships with national, regional, and local governments and public health agencies and emergency medical service providers to obtain necessary data on the transportation and patient logistic components of such models as required.

Business and Continuity of Operations

Supply Chain Vulnerabilities in Mass Critical Care

1. We suggest highest priority critical care supplies and medications needed for routine day-to-day care, and crucial in mass casualty events, for which no substitutions are available be identified (eg, ventilator circuits, N95 masks, insulin, etc). Once identified, dual sourcing should be used for routine purchasing of these key supplies and medications to reduce the impact of a supply chain disruption.

2. We suggest available alternatives for routinely used critical care supplies and medications (eg, sedatives, vasopressors, antimicrobials, etc) be identified in routine practice and pre-event planning to anticipate solutions to supply chain disruptions.

3. We suggest health-care systems use integrated electronic systems to track purchase, storage, and use of medical supplies.

4. We suggest these systems be used to identify equipment, supplies, and medications that are in short supply and for which increased routine inventory levels would be needed to adequately address both day-to-day and mass casualty event planning.

5. We suggest modified use protocols, which restrict routine use of affected medications and supplies and encourage use of alternatives, be implemented at the earliest opportunity when impending medication and medical supply shortages are identified, and for which adequate resupply may not be available in a timely manner.

6. We suggest health-care facilities, health systems, and health-care coalitions encourage, comply with, and support ongoing governmental and non-governmental organizational efforts to reduce global medical supply chain vulnerabilities.

Health Information Technology Continuity in Disasters

Portable Mobile Support Information Networks

7. We suggest hospitals have the mobile technology necessary to identify patients quickly and effectively, including in austere parts of the hospital (eg, parking lots).

8. We suggest hospitals have the ability to set up ad-hoc secure networks in austere sections of the hospital campuses for mobile technology.

9. We suggest hospitals have a strategy for supplying austere sites with electric power to charge the mobile devices, provide local network facilities, and provide essential services for an extended period of time.

10. We suggest hospitals be capable of transferring patient identification, identification of next of kin with contact information, and a defined minimal database of medical history with every patient. This minimal database of medical history should be able to be printed, or hand written if necessary, in the absence of computer technology.

11. We suggest hospitals have the ability to effectively and quickly download all patient-related information into a mobile package (eg, a flash drive or disk) that can be easily read by other information systems, and can be rapidly prepared for transport with the patient. This should obey the clinical document architecture/continuity of care document documents currently specified under meaningful use proposals, making them both human and digitally readable.

12. We suggest hospitals have real-time connection to databases for uploading and downloading clinical information.

13. We suggest hospitals have the necessary information technology (IT) functionality to store health information when hospital systems are not available, and be able to rapidly upload and download clinical information once connections are reestablished.

14. We suggest hospitals have the means to ensure confidentiality of all patient protected information.

15. We suggest patient information may be uploaded and stored in central, off site databases, similar to that used by the Veterans Administration system in the United States, and consistent with local health-care laws and regulation pertaining to patient privacy and protections.

Hospitals and Health-Care IT Preparedness Planning

16. We suggest hospitals have a plan for rapid movement of the data center to offsite remote operations in the case of prolonged local power disruption for critical functions.

17. We suggest a plan be in place to provide power to the client machines, analyzers, networking equipment, etc along with the data center for an extended period of time.

18. We suggest hospitals plan around extended supply disruption of critical IT supplies, such as servers and disk drives.

Engagement and Education

1. We suggest integrated communication systems and a robust infrastructure of the electronic health record system to facilitate tracking the number of people affected by a mass event, including the types and severity of injuries and detection of secondary illnesses.

2. We suggest, when power is intact, virtual ICUs, point-of-care testing, portable monitoring systems with Global Positioning System, and telemedicine facilitate transfer and sharing of clinical information. Such technologies need to be established and used prior to mass critical care delivery in order to provide familiarity to the users.

3. We suggest aggregated essential clinical information be included with other key ICU logistical communication so that bidirectional transfer of information permits a consistent delivery of health care across the spectrum.

4. We suggest public health/government officials at centralized or regional emergency management coordinating centers use expert medical guidance, such as burn, neuro, or trauma critical care, specific to the nature of the incident to inform decision-making for mass critical care delivery.

5. We suggest every ICU clinician participate in disaster response training and education.

6. We suggest expectations regarding clinician response to disasters or pandemics be delineated in contractual agreements, medical staff bylaws, or other formal documents that govern the array of responsibilities to the health-care system.

7. We suggest hospitals employ and/or train ICU physicians in disaster preparedness and response.

8. We suggest hospitals ensure appropriate ICU leadership with knowledge and expertise in the management of surge capacity, disaster response, and ICU evacuation.

9. We suggest critical care leaders be invited to participate in health-care coalitions so they can facilitate sharing expertise, resources, and knowledge between ICUs in the event of a regional disaster.

10. We suggest incorporation of disaster medicine into critical care training curricula will facilitate future ICU clinician training and engagement in disaster preparedness and response activities.

11. We suggest expert opinions be considered in mass critical care education curricula.

12. We suggest an independent panel of multidisciplinary specialty society experts determine the core competencies for mass critical care education curriculum.

13. We suggest translating competencies into multidisciplinary learning modules become a core focus of academic, professional organizations, governmental, and nongovernmental organizations whose students and responsible agencies may be called upon to provide mass critical care.

14. We suggest standing committees in education, or a reasonable equivalent in relevant stakeholder groups, review and endorse the curriculum and competencies.

15. We suggest educational activities draw on all modern modalities of education (including access via web-based learning, simulation, or other modalities for remote learners) and include incremental (individual, organizational, community), realistic, and challenging training opportunities.

16. We suggest stakeholder organizations determine the thresholds and milestones for trainer education and certification.

17. We suggest individuals with board certification in critical care medicine be tested on the core competencies (when developed) by their certification process.

18. We suggest those involved with critical care disaster education develop ongoing, internal process improvement methodologies and metrics to ensure their programs remain current, responsive, and relevant.

19. We suggest accreditation bodies that ensure safe and effective critical care delivery processes for hospitals consult with professional societies to develop metrics and tools of assessment to ensure ICUs can continue to provide quality care during a disaster or pandemic.

20. We suggest engagement of critical care clinicians in disaster preparedness efforts occur in advance of and in preparation for pandemics and disasters in order to enhance mass critical care delivery and coordination.

21. We suggest ICU clinicians and disaster planners incorporate community values into critical care decision-making through pre-event inclusion of clinicians and community perspectives.

22. We suggest hospitals provide education, training, and community conversation opportunities for their ICU clinicians on the topic of mass critical care delivery.

23. We suggest successful critical care clinician-community engagement strategies include: (a) physician-related initiatives, (b) public-private partnerships with governmental agencies and hospitals, (c) community partnerships, (d) sharing of best practices, and (e) family engagement and community guidance during resource allocation.

Legal Preparedness

1a. We suggest health agencies at all levels of government (ie, Local, Regional, State/Province, and National) and relevant health-care system entities (eg, hospitals, long-term care facilities, and clinics) develop mass critical care (MCC) response plans in furtherance of a legal duty to prepare for mass critical care emergencies. These plans should be integrated into or with existing crisis standards of care, surge capacity, or other applicable health emergency plans and frameworks. The regional health authority (eg, in the US, state health departments) should facilitate and ensure the development of mass critical care plans at the sub-national and health-care facility levels to promote inter-jurisdictional consistency and collaboration within the state/province, across state/province lines, and with national partners.

1b. We suggest MCC plans clarify approaches and processes for evacuating patients and for sheltering-in-place. This includes identifying the lines of authority for evacuation and shelter-in-place decision-making and the potential legal and ethical implications associated with such decisions.

1c. We suggest MCC plans recognize the importance of responsible and accountable MCC decision making among clinicians, government, and individual health-care entities by addressing how reviews of decisions made under the auspices of MCC plans will occur. Further, we suggest separate, efficient processes be developed to: (1) during the response, address fact–based appeals by ICU providers of decisions made during the response before resources are reallocated; and (2) following the response, review patient/family member or ICU provider concerns about fidelity to the processes outlined in properly-vetted and adopted MCC plans.

2. We suggest during declared emergencies: (1) government MCC plans be officially activated by the applicable governmental authority; and (2) individual health-care facility MCC plans be officially activated by clinical administrative leadership. We also suggest governments and individual health-care facilities develop approaches for the official deactivation of their MCC plans.

3a. We suggest clinicians (both employees and volunteers) and health-care entities involved in the provision of critical care that follow properly-vetted and officially-activated (1) governmental and (2) individual facility-level MCC plans in good faith should be protected legally from liability.

3b. In sudden-onset emergencies (or in the early phases of other emergencies), it might not be feasible for governments to declare an emergency, or for governments and health-care facilities to immediately and officially activate their MCC plans. In such cases we suggest clinicians and health-care entities that provide MCC reasonably and in good faith be afforded liability protections (ie, absent gross negligence, willful misconduct, or criminal acts) through retroactive activation or application of declarations and plans or other appropriate legal routes.

4. We suggest governments develop approaches to formally and temporarily expand the available pool of qualified practitioners to address MCC staffing shortages and to ensure that all responding practitioners receive appropriate liability protections during a MCC response. Further, we suggest this could occur through implementing efficient processes for licensing, credentialing, and certifying in-country practitioners who are not normally authorized to practice in the impacted area to facilitate the emergency response; temporarily expanding professional scopes of practice for applicable types of health-care practitioners; and, if appropriate, accepting and using official, formally vetted foreign medical teams.

Ethical Considerations

Triage and Allocation

1. We suggest resources not be held in reserve once a mass disaster protocol is in effect.

2. We suggest disaster and pandemic policies reflect the broad consensus that there is no ethical difference between withholding and withdrawing care and that education regarding such policies be incorporated into training.

3. We suggest triage systems based even on limited evidence are ethically preferable to those based on clinical judgment alone.

4. We suggest critical care resources be allocated based on specific triage criteria, irrespective of whether the need for resources is related to the current disaster/pandemic or an unrelated critical illness or injury.

5. We suggest it may be ethically permissible to use exclusion criteria for critical care resources, since the advantages of objectivity, equity, and transparency generally outweigh potential disadvantages.

6. We suggest protocols permitting the exclusion of patients from critical care during a mass disaster based on a high level of ongoing resource consumption may be ethically permissible.

7. We suggest it is ethically permissible to identify certain resource intensive therapies, procedures or diagnostic tests that should be limited or excluded during crisis standards of care.

8. We suggest policies permitting the withdrawal of critical care treatment to reallocate to someone else based on higher likelihood of benefit may be ethically permissible.

9. We suggest patients who do not qualify under a mass critical care (MCC) protocol for critical care receive do not resuscitate (DNR) orders.

10. We suggest specific groups, eg, health-care workers or first responders, not receive enhanced access to scarce critical care resources when crisis standards of care are in effect.

11. We suggest age of entry for adult critical care units be adjusted down during MCC emergencies that effect substantial numbers of children.

12. We suggest active life-ending procedures are not ethically permissible, even during disasters or pandemics.

Responding to Ethical Concerns of Patients and Families

13. We suggest hospitals communicate the definition of crisis standards of care clearly to patients and families both on admission to the hospital and when triage decisions are communicated.

14. We suggest patients triaged to palliative care be notified of their right to discuss concerns and receive support from hospital personnel, including palliative care, social work, or ethics.

15. We suggest hospitals include ethics resources in planning for MCC and should anticipate a need for ethics consultative services during the event.

Responsibilities to Providers

16. We suggest hospitals make plans to assist with moral distress in providers involved in providing MCC.

17. We suggest critical care clinicians who are unable to accept implementation of crisis standards of care be transferred into support or non-clinical roles during disaster response, if possible, but not be absolved of their obligation to participate in the response.

18. We suggest hospitals plan to protect worker safety and encourage providers/workers to create personal/family disaster preparedness plans.

Conduct of Research

19. We suggest researchers collaborate on a national guidance document that develops standards for obtaining institutional review board (IRB) approval in advance of disasters, and offers ethically, clinically, and legally acceptable mechanisms for research in the disaster context.

20. We suggest research conducted during pandemics and disasters focus specifically on improving treatment, safety, and outcomes.

International Disaster Response

21. We suggest international disaster responders coordinate efforts with local officials and clinicians to focus on interventions that will provide sustainable benefits to the population after the disaster.

22. We suggest international disaster responders have an ethical obligation to familiarize themselves with the predominant cultural and religious practices of the affected population.

23. We suggest international disaster responders demonstrate culturally and religiously appropriate respect for the dead within the disaster context by coordinating responses with local institutions.

Resource-Poor Settings: Infrastructure and Capacity Building

Definition

1. We suggest the term “resource poor or constrained setting” defines a locale where the capability to provide care for life-threatening illness is limited to basic critical care resources, including oxygen and trained staff. It may be stratified by categories: No resources, limited resources, and limited resources with possible referral to higher care capability.

2. We suggest “critical care in a resource poor or constrained setting” be defined by the provision of care for life threatening illness without regard to the location, including the pre-hospital, emergency, hospital wards, and intensive care setting.

Infrastructure and Capacity Building

3. We suggest in order to provide quality critical care, at any capability level, resource limited countries or health-care bodies should strengthen their primary care, basic emergency care, and public health systems.

4. We suggest capacity building in public health include education for families, community health-care workers, and clinicians in addition to infrastructure support such as transportation and communication systems.

5. We suggest developing countries strive to build capacity by leveraging critical care expertise and resources that exist in such disciplines as surgery, obstetrics, internal medicine, and pediatrics.