Abstract

Lau HM-C, Lee EW-C, Wong CN-C, Ng GY-F, Jones AY-M, Hui DS-C. The impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome on the physical profile and quality of life. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2005;86:1134–40.

Objective

To investigate the impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) on the physical fitness and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) among SARS survivors.

Design

A cohort study.

Setting

An outpatient physiotherapy department in a major hospital in Hong Kong.

Participants

SARS patients (N=171) discharged from the hospital. Their mean age was 37.36±12.65 years, and the average number of days of hospitalization was 21.79±9.93 days.

Interventions

Not applicable.

Main Outcome Measures

Subjects’ cardiorespiratory (6-minute walk test [6MWT], Chester step test for predicting maximal oxygen uptake [V̇o2max]), musculoskeletal (proximal/distal muscle strength and endurance test), and HRQOL status (Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey [SF-36]) were measured and compared with the normative data matched for age and sex.

Results

Seventy-eight (45.61%) patients continued to require prednisolone (<0.5mg·kg−1·d−1) for residual lung opacities when data were collected. The values of 6MWT distance, predicted V̇o2max, proximal and distal muscle strength, and the scores from all SF-36 domains, particularly perceived role-physical, were significantly lower than the normative data (P<.05).

Conclusions

SARS survivors had deficits in cardiorespiratory and musculoskeletal performance, and their HRQOL appeared to be significantly impaired.

Key Words: Muscles, Oxygen consumption, Physical endurance, Quality of life, Rehabilitation, SARS virus

IN MARCH 2003, AN OUTBREAK of atypical pneumonia in which patients had fever plus 1 or more respiratory symptoms such as cough, shortness of breath, and difficulty in breathing 1, 2 was defined by the World Health Organization as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). 3 Chest radiographs and tomography of the patients revealed varying degrees of lung injury characterized by multiple areas of peripheral ground-glass appearances and consolidation. 1, 4 Three months after the first reported case of SARS, 1755 patients in Hong Kong were diagnosed with this syndrome and 299 patients died.

Patients were hospitalized an average of approximately 3 weeks; all who were discharged from Prince of Wales Hospital were followed up through the hospital’s newly established SARS review clinic. Its purpose was to monitor their medications and to evaluate their physical and pulmonary function. Many patients had varying degrees of tremor in their hands, general muscle weakness, tachycardia, and exertional dyspnea. These patients complained of difficulty with daily living activities such as walking (level, uphill), climbing stairs, and simple housework. Many received short bursts of high-dose systemic steroid during hospitalization, 1 and most continued to require maintenance doses of prednisolone for residual lung opacities on radiographic study. 5 The post-SARS weakness could have been a consequence of prolonged bedrest, steroid myopathy, 6 residual disease pathology, deconditioning of the cardiopulmonary system, or a combination of these factors.

Because SARS is a new disease, there are no reports of its effect on the physical fitness and quality of life (QOL) of patients recovering from it. This is important because knowing the effects of SARS on these parameters may guide the design of rehabilitation programs and assessment. Therefore, our objective in this study was to assess the physical profile and QOL of patients recovering from SARS in the subacute and stable phase and to compare these with age- and sex-matched normative data.

Methods

Participants

All patients followed up at the SARS review clinic of the Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, between May and July 2003 were invited to participate in the study. Excluded were patients who were hemodynamically unstable (fluctuating blood pressure and resting heart rate), poorly motivated, uncooperative, unable to communicate, had poor pre-SARS mobility, and had an unstable medical condition (eg, known cardiopulmonary disorders) or a musculoskeletal condition that affects mobility (such as rheumatoid arthritis and avascular necrosis).

Approval for the study was obtained from the Joint Chinese University of Hong Kong-New Territories East Cluster Clinical Research Ethics Committee and informed written consent was obtained from each subject. A total of 171 subjects met the inclusion criteria during the studied period; assessment of cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal function, and QOL status for each subject was conducted 2 weeks after discharge from the hospital (≈5wk after syndrome onset).

Assessments of Functional Performance and QOL Status

Cardiorespiratory fitness

Maximal oxygen uptake (V̇o2max) is the usual measure of cardiorespiratory endurance. 7 Use of a maximal exercise test to measure V̇o2max was not feasible in this study because it requires more sophisticated equipment and participants must exercise to the point of volitional fatigue under physician supervision. 8 Submaximal exercise testing is therefore a common alternative to determine and predict a patient’s cardiorespiratory fitness. 8 Cardiorespiratory fitness was assessed by the 6-minute walk test (6MWT) 9 and the Chester step test. 10

The 6MWT is a simple functional assessment commonly applied in long-term follow-up of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) 11 and survivors of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). 12 Subjects are required to walk at their own pace but to cover the farthest distance in the 6-minute time interval. 9, 11 The Chester step test is another economical method used to predict V̇o2max. 8 It is an incremental 5-level step test, commencing at the relatively slow pace of 15 steps per minute and increasing every 2 minutes to 20, 25, 30, and 35 steps per minute. The test is terminated when the subject reaches approximately 80% of maximum heart rate or a rating of perceived exertion of 6 (moderately hard). V̇o2max can then be predicted by plotting the corresponding heart rate at different step levels, with a minimum of 3 points (level 3). 10

Musculoskeletal fitness

Clinically, many SARS survivors appeared to suffer from certain degrees of weakness involving central, proximal, and distal muscles. We used a digital handheld dynamometer a to assess the isometric strength of the anterior deltoid and gluteus maximus muscles. Strength is measured as the subject attempts to hold an isometric contraction while the tester pushes against the body part with the dynamometer to break the contraction. 13 We used a Jamar handheld dynamometer b to measure the handgrip (distal muscle) strength. 14, 15 All patients also performed 1-minute curl-up and push-up tests. The numbers of curl-ups and push-ups were recorded to evaluate the endurance of their abdominal and upper-limb muscles. 16 One assessor was assigned to take all measurements.

Health-related quality of life status

We used the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) 17, 18 to evaluate each subject’s health-related quality of life (HRQOL) status. The SF-36 is comprised of 36 questions with 8 subscales, including physical functioning, role-physical, role-emotional, bodily pain, social functioning, general health, mental health, and vitality. A score between 0 and 100 is assigned to each domain, with higher scores indicating more favorable functional status. 17

Data Analysis

The data were subjected to descriptive analysis, including the mean, median, standard deviation (SD), 95% confidence interval (CI), and floor and ceiling effect. An independent t test was used for mean comparison with normative data matched for age and sex. We used a Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons with α adjusted to .05. Scale scores from the SF-36 were calculated using the standard scoring algorithm. 17 Missing data were treated with SPSS means series correction. We used SPSS, version 11.0, c for data analysis and GraphPad InStat, version 2.00, d for mean comparisons with normative data.

Results

Demographic and Baseline Characteristics

Of 258 SARS patients admitted to the Prince of Wales Hospital, 31 (12.02%) were not accessible, 54 (20.93%) declined to participate in the assessment process, and 2 (.78%) died. The remaining 171 (111 women, 60 men) patients (66.28%) who consented to participate had a mean hospitalization stay of 21.8 days, with intensive care unit (ICU) admission from 0 to 120 days (n=24; mean, 2.63±11.2d). The demographic data for all subjects are listed in table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic Data and Cardiorespiratory Fitness Profile of the 171 Patients

| Characteristics | Men (n=60) | Women (n=111) | All Patients (N=171) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) (range, 17–89y) | 38.72±14.21 | 36.63±11.72 | 37.36±12.65 |

| Days of hospitalization | 24.05±13.73 | 20.60±6.97 | 21.79±9.93 |

| Post-SARS duration (d) | 84.36±17.99 | 80.45±18.64 | 81.79±18.46 |

| Resting heart rate (beats/min) | 86.10±12.42 | 86.91±12.50 | 86.63±12.44 |

| Resting rate of perceived exertion (median) | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Resting Spo2 (%) | 97.73±1.07 | 98.36±1.14 | 98.14±1.16 |

| Resting respiratory rate (breath/min) | 18.52±4.47 | 19.39±4.35 | 19.08±4.40 |

| Medication⁎ (%) | |||

| No medication | 53.30 | 51.40 | 52 |

| Steroid | 45.00 | 45.90 | 45.6 |

| Others | 1.70 | 2.70 | 2.4 |

| 6-minute walk distance | |||

| Distance covered (m) | 624.32±119.03 (n=60) | 583.66±94.34 (n=111) | 597.92±105.14 (n=171) |

| Chester step test | |||

| Predicted V̇o2max (mL·kg−1·min−1) | 38.47±7.39 (n=43) | 36.19±7.42 (n=91) | 36.92±7.46 (n=134) |

| No. of patients completing 5 test levels (%) | 24 (40) | 46 (41) | 70 (41) |

NOTE. Values are mean ± SD unless otherwise stated.

Abbreviation: Spo2, oxygen saturation as measured by pulse oximetry.

Any steroids or medications taken in the postdischarge phase.

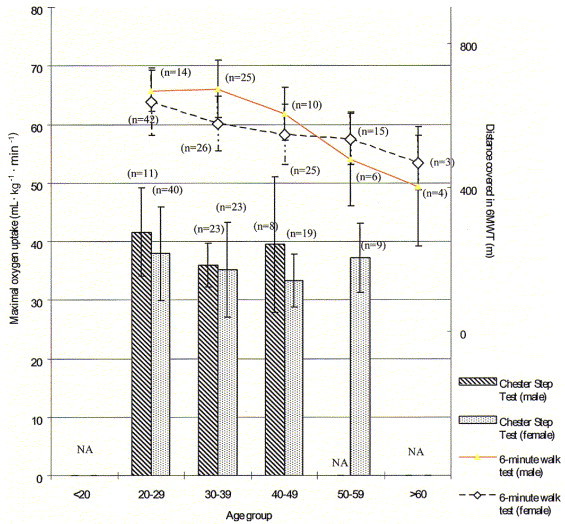

Cardiorespiratory Fitness

Figure 1 shows the means ± SDs of the 6-minute walk distance covered by the patients. It shows that distance covered declined with advancing age, from 667.57±57.13m for men who were 20 to 29 years old to 402.43±166.33m for men who were more than 60 years old, and from 636.64±93.08m for women who were 20 to 29 years old to 467.43±75.05m for women more than 60 years old. When compared with the normative data matched for age, 19 there was a significant decrease in the mean performance of our patients across different age groups (P≤.005), as analyzed by independent t test (table 2). Further analysis revealed that the 6-minute walk distance correlated significantly and positively with the post-SARS duration but correlated negatively with the number of hospitalization days (table 3).

Fig 1.

Means and SDs of the 6MWT and the Chester step test of SARS patients with sex comparison. Abbreviation: NA, not applicable (for age groups <5 patients).

Table 2.

Comparison of 6-Minute Walk Distance Between SARS Patients and Normative Data

| Group | Age (y) | Patients | Mean ± SD | P | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | <20 | SARS (n=1) | NA | NA | NA |

| 2 | 20–29 | SARS (n=56) | 644.37±86.10 | .005⁎ | 621.31–667.43 |

| Normative | 698.00±76.00 | ||||

| 3 | 30–39 | SARS (n=51) | 623.53±91.22 | .001⁎ | 597.87–649.19 |

| Normative | 698.00±76.00 | ||||

| 4 | 40–49 | SARS (n=35) | 563.90±84.17 | .001⁎ | 534.99–592.82 |

| Normative | 635.00±57.00 | ||||

| 5 | 50–59 | SARS (n=21) | 517.88±91.62 | .001⁎ | 476.18–559.59 |

| Normative | 635.00±57.00 | ||||

| 6 | >60 | SARS (n=7) | 430.29±130.07 | .004⁎ | 309.99–550.58 |

| Normative | 512.00±79.00 |

NOTE. Normative data provided by Coordinating Committee for Physiotherapy, Hospital Authority.19

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable (for age group <5 patients).

Statistically significant at P<.05 (independent t test).

Table 3.

Relation Between Dependent Variables and Days of Hospitalizion, Post-SARS Duration, and Total Dosage of Medication

| Variables | HR | 6MWT | V̇o2max | AD | GM | Curl-Up | Push-Up | SF-36 (physical) | SF-36 (mental) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospitalization days | .022⁎ (.18) | .03⁎ (−.15) | NS | .006⁎ (−.19) | NS | NS | NS | .005⁎ (−.22) | NS |

| Post-SARS duration | NS | .009⁎ (.17) | NS | .021⁎ (.16) | .021⁎ (.17) | NS | NS | .007⁎ (.20) | NS |

| Total medication dosage | NS | NS | .007⁎ (−.24) | NS | NS | .014⁎ (−.18) | NS | NS | NS |

NOTE. Values are P and (standardized β coefficient).

Abbreviations: AD, anterior deltoid strength; GM, gluteus maximus strength; HR, heart rate; NS, not significant.

Statistically significant at P<.05 (stepwise linear regression).

The predicted V̇o2max ranged from 41.63±7.57mL·kg−1·min−1 (age range, 20–29y) to 39.50±11.60mL·kg−1·min−1 (age range, 40–49y) for men and from 37.94±8.05mL·kg−1·min−1 (age range, 20–29y) to 37.22±5.88mL·kg−1·min−1 (age range, 50–59y) for women (see fig 1). The percentage of subjects who completed all 5 levels of the Chester step test was 41% (see table 1). Further analysis showed the predicted V̇o2max correlated negatively with the total dosage of prednisolone consumed while the resting heart rate correlated positively with the number of days of hospitalization (P=.022) (see table 3).

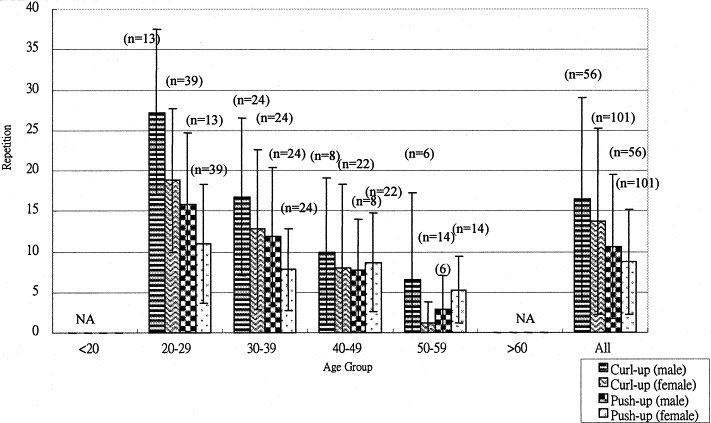

Musculoskeletal Fitness

When compared with the normative data, 20 performance in handgrip strength was subnormal while curl-up and push-up performances were “below average” to “poor.” Strength of the gluteus maximus and anterior deltoid (summation of both sides) was recorded but no normative data were available for comparison; results are displayed in table 4. The means and SDs of the curl-up and push-up tests are shown in figure 2.

Table 4.

Results of Musculoskeletal Profile of SARS Patients

| Outcomes | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|

| Anterior deltoid strength⁎ (kgf) | 26.50±10.32 | 17.37±5.99 |

| Gluteus maximus strength⁎ (kgf) | 33.98±15.43 | 24.24±11.84 |

| Handgrip strength⁎ (kgf) | 69.25±18.81 | 45.04±12.89 |

| Curl-up (repetitions in 1min) | 16.41±12.58 | 13.74±11.49 |

| Push-up (maximum repetitions in 1 trial) | 10.59±8.86 | 8.71±6.46 |

NOTE. Values are mean ± SD.

Summation of both sides.

Fig 2.

Means and SDs of number of curl-ups (repetitions per minute) and push-ups (maximum repetitions per trial) stratified by sex and age group.

HRQOL Status

A total of 164 (95.91%) subjects completed the SF-36. The scores for each domain are shown in table 5. This analysis revealed a significantly lower score in every domain of the QOL status (total subscores of men and women) compared with Hong Kong norms. 21 More than 50% of the patients scored at the floor effect on the role-physical domain.

Table 5.

Comparison of HRQOL Outcomes Between SARS Patients and Subjects With Normal Health

| Scale/Sample | Mean ± SD | % Floor⁎ | % Ceiling† | P | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PF | |||||

| Men (n=55) | 74.36±22.20 | 0.00 | 9.09 | <.001‡ | 68.35–80.37 |

| Normative | 94.02±10.88 | ND | |||

| Women (n=108) | 67.08±20.98 | 0.00 | 3.70 | <.001‡ | 63.07–71.09 |

| Normative | 89.82±14.19 | ND | |||

| Total (n=163) | 69.54±21.61 | 0.00 | 5.52 | <.001‡ | 66.23–72.85 |

| Normative | 91.83±12.89 | 91.32–92.35 | |||

| RP | |||||

| Men (n=55) | 37.27±41.63 | 47.27 | 23.64 | <.001‡ | 26.01–48.53 |

| Normative | 85.31±28.38 | ND | |||

| Women (n=108) | 29.40±38.95 | 57.41 | 14.81 | <.001‡ | 21.96–36.84 |

| Normative | 79.79±32.96 | ND | |||

| Total (n=163) | 32.06±39.92 | 53.99 | 17.79 | <.001‡ | 25.95–38.17 |

| Normative | 82.43±30.97 | 81.19–83.67 | |||

| RE | |||||

| Men (n=55) | 56.36±45.30 | 34.55 | 45.45 | .003‡ | 44.11–68.62 |

| Normative | 72.34±37.88 | ND | |||

| Women (n=108) | 43.21±41.08 | 37.96 | 26.85 | <.001‡ | 35.37–51.05 |

| Normative | 71.04±38.80 | ND | |||

| Total (n=163) | 47.65±42.87 | 36.81 | 33.13 | <.001‡ | 41.09–54.21 |

| Normative | 71.66±38.36 | 70.13–73.19 | |||

| BP | |||||

| Men (n=55) | 76.36±23.38 | 0.00 | 33.36 | <.001‡ | 70.04–82.69 |

| Normative | 87.07±18.98 | ND | |||

| Women (n=108) | 64.94±25.15 | 0.00 | 23.15 | <.001‡ | 60.14–69.74 |

| Normative | 81.14±23.91 | ND | |||

| Total (n=163) | 68.79±25.09 | 0.00 | 27.61 | <.001‡ | 64.95–72.63 |

| Normative | 83.98±21.89 | 83.11–84.85 | |||

| SF | |||||

| Men (n=55) | 68.41±23.31 | 0.00 | 18.18 | <.001‡ | 62.10–74.72 |

| Normative | 91.45±16.00 | ND | |||

| Women (n=108) | 59.14±23.90 | 0.00 | 12.96 | <.001‡ | 54.58–63.70 |

| Normative | 90.96±17.08 | ND | |||

| Total (n=163) | 62.27±24.04 | 0.00 | 14.72 | <.001‡ | 58.59–65.95 |

| Normative | 91.19±16.57 | 90.53–91.82 | |||

| GH | |||||

| Men (n=55) | 55.89±20.90 | 1.82 | 1.82 | .203 | 50.24–61.44 |

| Normative | 59.32±19.43 | ND | |||

| Women (n=108) | 48.00±20.99 | 0.00 | 0 | .016‡ | 43.99–52.01 |

| Normative | 52.92±20.38 | ND | |||

| Total (n=163) | 50.66±21.33 | 0.61 | 0.61 | .001‡ | 47.41–53.91 |

| Normative | 55.98±20.18 | 55.17–56.79 | |||

| MH | |||||

| Men (n=55) | 72.51±19.26 | 0.00 | 12.73 | .801 | 67.30–70.72 |

| Normative | 73.07±15.93 | ND | |||

| Women (n=108) | 64.11±17.97 | 0.00 | 2.77 | <.001‡ | 60.68–67.64 |

| Normative | 72.53±17.13 | ND | |||

| Total (n=163) | 66.95±18.78 | 0.00 | 6.13 | <.001‡ | 64.08–69.82 |

| Normative | 72.79±16.57 | 72.13–73.45 | |||

| VT | |||||

| Men (n=55) | 58.09±19.09 | 0.00 | 0 | .142 | 52.93–63.25 |

| Normative | 61.67±17.59 | ND | |||

| Women (n=108) | 45.74±17.43 | 0.93 | 0.93 | <.001‡ | 42.41–49.07 |

| Normative | 59.00±19.48 | ND | |||

| Total (n=163) | 49.91±18.88 | 0.61 | 0.61 | <.001‡ | 47.02–52.80 |

| Normative | 60.27±18.65 | 59.53–61.02 |

NOTE. Normative data refers to the study conducted by Lam et al.21 Values are mean ± SD unless otherwise noted.

Abbreviations: BP, bodily pain; GH, general health; MH, mental health; ND, no data; PF, physical functioning; RE, role-emotional; RP, role-physical; SF, social functioning; VT, vitality.

Proportion of subjects with the lowest possible score.

Proportion of subjects with the highest possible score.

Statistically significant at P<.05.

Discussion

SARS is a highly infectious disease with a formidable morbidity and mortality rate. Many patients who recovered from it appeared to show a considerable decline in their physical fitness, with major complaints of varying degrees of tremor, dyspnea, fatigue, and emotional distress. 22, 23 Note that the results of predicted V̇o2max using the Chester step test differed slightly from those of the 6MWT. Some patients achieved an excellent V̇o2max according to the rating system, 10 despite their failure to complete 5 levels of the test and their subjective complaints of distress and lower-limb weakness.

The SARS patients had a higher baseline heart rate, and the heart rate increased slowly and steadily during the Chester step test. This would then project a better value for the final predicted V̇o2max level, and the V̇o2max was “inflated” in these patients. One advantage of applying the Chester step test is the ease of documenting the percentage of subjects who successfully complete all 5 levels, thus allowing for future comparison (see table 1). Clinically, the 6MWT is a feasible and sensitive test in assessing SARS patients’ cardiorespiratory status.

Our analysis suggests that cardiorespiratory and musculoskeletal function during the early phase of recovery from SARS is worse than normative data. However, exercise performance of recovering SARS patients was superior to patients with COPD. The 6-minute walk distance covered by our post-SARS patients (597.9m) was greater than the distance reported in studies of patients with COPD (473.5m). 24 Also, the predicted V̇o2max in SARS patients who required ICU admission was 36mL·kg−1·min−1, whereas for those recovering from ARDS after intensive care was 24mL·kg−1·min−1, 25 and for those with COPD was as low as 12.4mL·kg−1·min−1. 26

The decrease in cardiorespiratory and musculoskeletal function in patients who were hospitalized for a mean of 3 weeks was not surprising. At the time of our assessment (82±19d from disease onset), 78 patients (45.61%) were still on maintenance steroid therapy (<0.5mg·kg−1·d−1 of prednisolone) for residual ground-glass opacities. 5 The cause of the decreased function is believed to be multifactorial, including immobility, anxiety, drug-induced hemolytic anemia from ribavirin treatment, high-dose steroid-induced myopathy, and underlying lung pathology such as atelectasis and fibrosis. 1, 22, 23

Because SARS is a new disease, there are no previous reports on the disease profile of patients with this condition. Our findings suggest that physical and cardiorespiratory impairments in post-SARS patients are comparable to patients with ARDS. In view of their moderate physical impairment, full recovery of cardiorespiratory and musculoskeletal function should be possible through early and intensive rehabilitation programs.

Despite moderate impairment of cardiorespiratory and musculoskeletal function, the reported SF-36 score reflects relatively greater HRQOL disability, particularly in the role-physical domain, in which more than 50% of the patients showed a floor effect. Our patients had lower role-physical (32.1), role-emotional (47.7), and social functioning (62.3) scores than did patients with ARDS (role-physical, 65; role-emotional, 75; social functioning, 81). 27, 28 It appears that SARS survivors experienced greater subjective physical, psychologic, and social deficits than ARDS patients, despite better performance in exercise testing and a higher predicted V̇o2max level.

The high mortality and social dislocation caused by SARS, and the universal publicity given to it, resulted in stress, anxiety, and vulnerability during the patients’ acute illnesses and during a phase of clinical deterioration with an average length of hospitalization of more than 3 weeks. 1, 22, 23 Patients with SARS were banned from visiting with relatives, some of whom became infected and some of whom died. These factors, not surprisingly, resulted in the low SF-36 scores. And it appears that this predominately pulmonary disease has a greater impact on one’s physical health than on one’s mental health, with more profound adverse effects on women because men could probably tolerate more stress in both functional and psychological aspects. 29, 30

Because there are obvious deficits in the cardiopulmonary performance and muscular strength and endurance among our SARS patients, we intend to evaluate further the effect of a physical rehabilitation program to improve their physical profiles and HRQOL. Some patients with specific muscular deficiencies may need more professional assessment, supervision, and advice. Apart from the safety issue, a supervised exercise program is necessary to encourage and motivate patients who may experience the unpleasant sensation of exertional dyspnea in the early rehabilitation phase. These patients require coaching and monitoring to overcome their fear-avoidance behavior when participating in the exercise program. We hope a supervised and tailored exercise program may boost their physical and emotional performance.

We were able to recruit only 171 of the 258 SARS survivors (66.28%) in our hospital. These findings may therefore be biased and not be representative of the whole SARS spectrum. Because of limited resources and our concern that many patients might be too weak to perform maximal stress tests, we chose submaximal exercise testing to determine and predict the cardiorespiratory fitness of the patients.

Conclusions

This descriptive study provides a database for the physical profile and QOL status of patients with SARS. Despite moderately impaired cardiopulmonary performance and musculoskeletal fitness, the HRQOL impairment was significant. We propose that early initiation of a comprehensive physical program to assist SARS patients in regaining full cardiorespiratory and musculoskeletal function may also help in their psychosocial recovery after SARS.

Suppliers

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Professor Chan Kai Ming, Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, the Chinese University of Hong Kong, for his invaluable assistance throughout the process, and all the staff of the Physiotherapy Department, Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, in preparing the SARS rehabilitation program.

Footnotes

No commercial party having a direct financial interest in the results of the research supporting this article has or will confer a benefit upon the author(s) or upon any organization with which the author(s) is/are associated.

Nicholas manual muscle tester, model 01160; Lafayette Instrument, 3700 Sagamore Pkwy N, PO Box 5729, Lafayette, IN 47904.

Sammons Preston Rolyan, 4 Sammons Ct, Bolingbrook, IL 60440-5071.

SPSS Inc, 233 S Wacker Dr, 11th Fl, Chicago, IL 60606.

GraphPad Software Inc, 11452 El Camino Real, #215, San Diego, CA 92130.

References

- 1.Lee N., Hui D., Wu A. A major outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1986–1994. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Donnelly C.A., Ghani A.C., Leung G.M. Epidemiological determinants of spread of causal agent of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong [published erratum in Lancet 2003;361:1832] Lancet. 2003;361:1761–1766. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13410-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization . Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS): status of the outbreak and lessons for the immediate future. WHO; Geneva: 2003. pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong K.T., Antonio G.E., Hui D.S. Severe acute respiratory syndrome: radiographic appearances and pattern of progression in 138 patients. Radiology. 2003;228:401–406. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2282030593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Antonio G.E., Wong K.T., Hui D.S. Thin-section CT in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome following hospital discharge: preliminary experience. Radiology. 2003;228:810–815. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2283030726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Decramer M., de Bock V., Dom R. Functional and histologic picture of steroid-induced myopathy in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;153(6 Pt 1):1958–1964. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.6.8665061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American College of Sports Medicine position stand The recommended quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory and muscular fitness in healthy adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998;30:975–991. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199806000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stevens N., Sykes K. Aerobic fitness testing: an update. Occup Health (Lond) 1996;48:436–438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Thoracic Society Statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:111–117. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.166.1.at1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sykes K. The Chester step test-ASSIST physiological measurement resources manual. Version 3. ASSIST Creative Resources Ltd; Liverpool, UK: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sciurba F., Criner G.J., Lee S.M. Six-minute walk distance in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: reproducibility and effect of walking course layout and length. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:1522–1527. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200203-166OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herridge M.S., Cheung A.M., Tansey C.M. One-year outcomes in survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:683–693. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bohannon R.W. Reference values for extremity muscle strength obtained by hand-held dynamometry from adults aged 20 to 79 years. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1997;78:26–32. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(97)90005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bellace J.V., Healy D., Besser M.P., Byron T., Hohman L. Validity of the Dexter Evaluation System’s Jamar dynamometer attachment for assessment of hand grip strength in a normal population. J Hand Ther. 2000;13:46–51. doi: 10.1016/s0894-1130(00)80052-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peolsson A., Hedlund R., Oberg B. Intra- and inter-tester reliability and reference values for hand strength. J Rehabil Med. 2001;33:36–41. doi: 10.1080/165019701300006524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heyward V.H. Advanced fitness assessment and exercise prescription. 4th ed. Human Kinetics; Champaign: 2002. pp. 113–134. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ware J.E., Snow K.K., Kosinski M., Gandek B. SF-36 health survey manual and interpretation guide. QualityMetric Inc; Lincoln: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lam C.L., Gandek B., Ren X.S., Chan M.S. Tests of scaling assumptions and construct validity of the Chinese (HK) version of the SF 36 health survey. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:1139–1147. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00105-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coordinating Committee for Physiotherapy, Hospital Authority. Normative data of 6-minute walk test. Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Hospital Authority, Hong Kong; 2003.

- 20.Normative data of physical fitness parameters. Available at: http://hk.geocities.com/physicalfitnesshk/. Accessed March 30, 2004

- 21.Lam C.L., Lauder I.J., Lam T.P., Gandek B. Population based norming of the Chinese (HK) version of the SF 36 health survey. Hong Kong Practitioner. 1999;21:460–470. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hui D.S., Sung J.J. Severe acute respiratory syndrome [editorial] Chest. 2003;124:12–15. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.1.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wong G.W., Hui D.S. Severe acute respiratory syndrome: epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment. Thorax. 2003;58:558–560. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.7.558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berry M.J., Rejeski W.J., Adair N.E., Ettinger W.H., Jr, Zaccaro D.J., Sevick M.A. A randomized, controlled trial comparing long-term and short-term exercise in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2003;23:60–68. doi: 10.1097/00008483-200301000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neff T.A., Stocker R., Frey H.R., Stein S., Russi E.W. Long-term assessment of lung function in survivors of severe ARDS. Chest. 2003;123:845–853. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.3.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoshikawa M., Yoneda T., Takenaka H. Distribution of muscle mass and maximal exercise performance in patients with COPD. Chest. 2001;119:93–98. doi: 10.1378/chest.119.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rothenhausler H.B., Ehrentraut S., Stoll C., Schelling G., Kapfhammer H.P. The relationship between cognitive performance and employment and health status in long-term survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome: results of an exploratory study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2001;23:90–96. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(01)00123-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schelling G., Stoll C., Vogelmeier C. Pulmonary function and health-related quality of life in a sample of long-term survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 2000;26:1304–1311. doi: 10.1007/s001340051342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holbrook T.L., Hoyt D.B., Anderson J.P. The importance of gender on outcome after major trauma: functional and psychologic outcomes in women versus men. J Trauma. 2001;50:270–273. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200102000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holbrook T.L., Hoyt D.B., Stein M.B., Sieber W.J. Gender differences in long-term posttraumatic stress disorder outcomes after major trauma: women are at higher risk of adverse outcomes than men. J Trauma. 2002;53:882–888. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200211000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]