Abstract

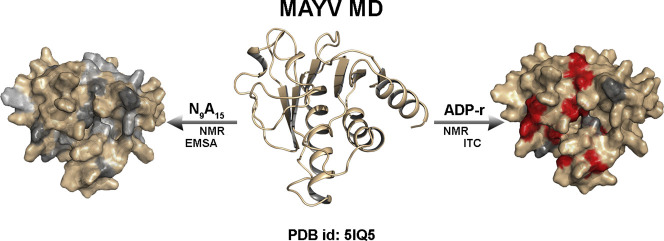

Mayaro virus (MAYV) is a member of Togaviridae family, which also includes Chikungunya virus as a notorious member. MAYV recently emerged in urban areas of the Americas, and this emergence emphasized the current paucity of knowledge about its replication cycle. The macro domain (MD) of MAYV belongs to the N-terminal region of its non-structural protein 3, part of the replication complex. Here, we report the first structural and dynamical characterization of a previously unexplored Alphavirus MD investigated through high-resolution NMR spectroscopy, along with data on its ligand selectivity and binding properties. The structural analysis of MAYV MD reveals a typical “macro” (ββαββαβαβα) fold for this polypeptide, while NMR-driven interaction studies provide in-depth insights into MAYV MD–ligand adducts. NMR data in concert with thermodynamics and biochemical studies provide convincing experimental evidence for preferential binding of adenosine diphosphate ribose (ADP‐r) and adenine-rich RNAs to MAYV MD, thus shedding light on the structure–function relationship of a previously unexplored viral MD. The emerging differences with any other related MD are expected to enlighten distinct functions.

Abbreviations: MAYV, Mayaro virus; CHIKV, Chikungunya virus; VEEV, Venezuelan Equine Encephalitis virus; SINV, Sindbis virus; MD, macro domain; ss(+) RNA, positive-sense single-stranded RNA; ADP-r, adenosine diphosphate ribose; ADP, adenosine diphosphate; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; AMP, adenosine monophosphate; NAD, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; HSQC, heteronuclear single quantum coherence; NOESY, nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy; CSP, chemical shift perturbation; ITC, isothermal titration calorimetry; EMSA, electrophoretic mobility shift assay

Keywords: Mayaro virus, Alphavirus, macro domain, ADP-ribose, RNA

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

First conformational and dynamics study of a previously unexplored Alphavirus macro domain (Mayaro virus macro domain, or MAYV MD)

-

•

MAYV MD selectivity and binding of ADP-ribose revealed by NMR spectroscopy and ITC

-

•

Identification of critical residues for the ADP-ribose binding

-

•

MAYV MD preference for binding of RNAs rich in adenine observed by NMR spectroscopy

-

•

Binding studies provide new insights for the design of novel ligands for MAYV and other Alphaviruses MDs.

Introduction

Alphaviruses belong to the Togaviridae family, whose members form enveloped particles characterized by icosahedral symmetry enclosing their genome. They cause mainly mosquito-borne diseases in vertebrates such as birds and rodents, which act as reservoir hosts. The genus Alphavirus is divided in two subcategories depending on the viruses' primary areas of endemicity and clinical manifestations [1], [2]. Old World Alphaviruses were initially identified in Asia and Africa, where they have been considered as causal agent of arthropathies [3], [4]. By contrast, New World Alphaviruses are usually implicated in neurological diseases with complications such as dysarthria, motor disorders and abnormal reflexes, and were detected solely in the Americas [5]. Mayaro virus (MAYV) is an exception to this classification. Despite its endemic distribution in South America, the induced disease has a clinical picture similar to the Old World Alphaviruses [6]. In particular, symptoms include mild-to-severe Dengue-like febrile syndrome, characterized by fever, headache, rash, myalgia, arthralgia and arthritis, which can be debilitating and can persist for months [4], [7], [8]. These clinical manifestations are reported also in the Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) disease.

The resemblance of MAYV and CHIKV diseases, the worldwide outbreaks of CHIKV, and the ability of MAYV to be reproduced into mosquitoes inhabiting urban environments underline the importance of this “neglected virus” [6], [9], [10], [11]. It is worth mentioning that MAYV is mainly transmitted by mosquitos of Haemagogus and Aedes genera, the latter being also responsible for the distribution of Zika, Dengue and Chikungunya viruses. The recent Alphavirus outbreaks in concert with the absence of vaccines and targeted antiviral therapy emphasize the necessity to understand their replication mechanisms in detail [3], [12]. The global distribution and the constantly reported outbreaks of these viral infections point out the significance of preventing the potentially chronic, disabling and long-lasting complications caused by these viruses, in order to reduce the social and economic impacts of these zoonoses.

The replication of Alphavirus occurs in spherules [13], [14] containing four non-structural proteins (nsP1 to nsP4) [15] resulting from processing of the precursors P123 and P1234. NsP1 is carrying the enzymatic activities for the mRNA cap formation, nsP2 has a N-terminal domain with multiple enzymatic activities (e.g., ATPase, RNA helicase, RNA triphosphatase) [16], [17], [18]. Its C-terminal part is carrying a protease activity for polyprotein processing with a papain-like domain and is followed by a classical 2’O-methyltransferase fold [19], [20]. NsP4 is carrying the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase activity [21] in charge of the replication/transcription. Many functions have been attributed to nsP3 in recent years [22]. Its C-terminal region, named HVR (hypervariable region), is a hub for interactions with several partners while its N-terminal region contains a globular macro domain (MD).

MDs are conserved and widely distributed versatile structural motifs of 130–190 amino acids. They are found both in prokaryotes and eukaryotes as well as in viruses [23], [24], [25], [26], [27].

Only few genera of positive-sense single-stranded RNA ((+)ss RNA) viruses contain MD folds, for example, Alphavirus, Coronovirus (CoV), Rubella virus and Hepatitis E virus. The Alphaviruses MDs are located at the N-terminal region of nsP3 and adopt a β/α/β mixed sandwich topology. Initially, MD's biological functions were linked to their ability to bind adenosine diphosphate ribose (ADP-r), its derivative (Poly-) ADP-r and RNA. In addition, Alphaviruses MDs were found to be adenosine di-phosphoribose 1″-phosphate phosphatases, but the role of this activity in viral replication remained elusive [27]. Subsequently, several studies proved its significance to viral replication and virulence, while recent studies proposed that the function of MDs is associated with their activity as ADP-ribosylhydrolases, suggesting their implication in counteracting responses to infection [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36]. In general, viral MDs are postulated to be critically involved in replication complex formation, cell-specific viral replication and ADP-ribosylation dependent interactions with host proteins [37]. It remains to be investigated if and how distinct properties of different Alphaviruses MDs such as sequence, structure, dynamics and ligand binding can be correlated to different functions and different viral replication profiles.

ADP-ribosylation is a fundamental nucleotide-based post-translational modification that is vital to cellular processes including cell signaling, DNA repair, RNA regulation and probably many others in various organisms. The addition and the removal of an ADP-r moiety to or from cellular targets are strongly regulated processes leading to functional changes through mono-ADP-ribosylation (MARylation) and/or poly-ADP-ribosylation (PARylation). The induced alterations of enzymatic activities and the ability of ADP-ribosylated proteins to serve as “anchors” for biomolecular interactions are connected with their assigned biological roles. These include DNA damage response, transcription signaling, cellular stress response, protein degradation and immune response. Most of the aforementioned functions require the cross-talk of proteins participating in the ADP-ribosylation and in other post-translational modifications, such as ubiquitination [38], [39], [40], [41], [42]. Recently, it was reported that ADP-ribosylation is induced upon Alphavirus infection in an interferon-independent manner [37].

The enzymes and protein domains involved in ADP-ribosylation are characterized as writers, erasers and readers [42], [43], [44], [45] based on their ability to transfer, remove and recognize ADP-r or ADP-ribosylated substrates. Among proteins binding ADP-r, MDs are classified as readers or/and erasers [42].

Herein, we address the structure–function relationship of the MAYV MD through the determination of its high-resolution NMR structure and dynamics. Furthermore, interaction studies with ADP-r, other adenosine derivatives and RNA oligonucleotides were performed through heteronuclear NMR spectroscopy, isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) and electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) analysis. The characterization on both a structural and a biochemical level elucidates physicochemical features of the MAYV MD, reveals that non-conserved loops are crucial for the structural plasticity and substrate selectivity of the domain, and provides novel mechanistic insights into the binding of various adenosine-based ligands.

Results and Discussion

NMR solution structure of MAYV MD

The solution structure of MAYV MD was determined from more than 1600 NMR-derived geometrical restraints (PDB ID: 5IQ5; BMRB accession no. 30043) (Fig. 1a and Table S2) [46], [47], [48]. The MAYV MD, spanning residues 1335 to 1493 of P1234, is characterized by a six-stranded β-sheet (β1 4–6, β2 18–21, β3 56–60, β4 63–67, β5 103–107, β6 138–142) surrounded at both sides by four major α-helices (α1 34–43, α2 78–98, α3 121–134, α4 149–157) (Fig. 1b). The secondary structure elements are arranged in a ββαββαβαβα topology, with β3 being the only antiparallel β-strand. This type of folding has also been encountered in other MDs exhibiting the typical three-layered β/α/β sandwich topology.

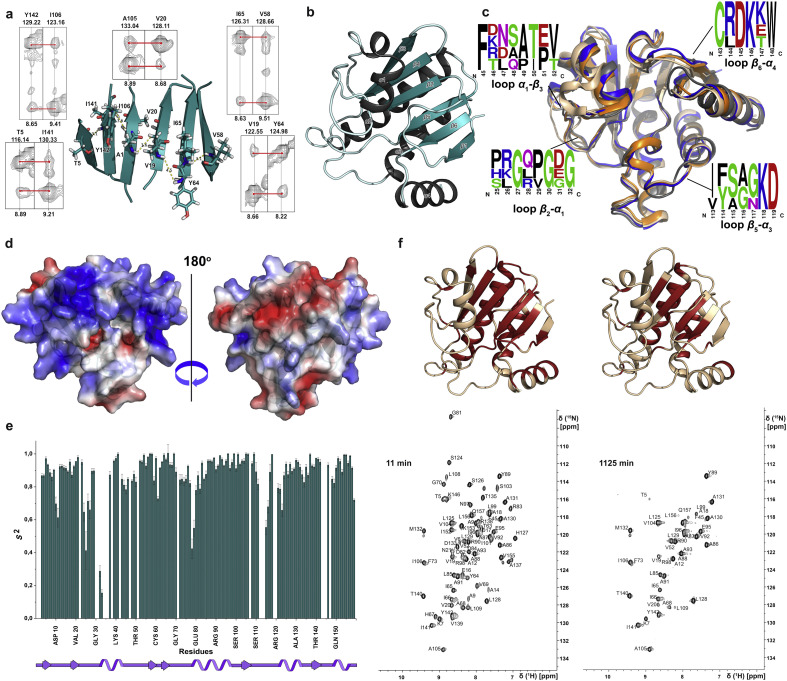

Fig. 1.

(a) Characteristic NOE restraints derived from a 15N-edited 3D NOESY–HSQC experiment. (b) Ribbon representation of the energy minimized average NMR model of MAYV MD. (c) Backbone superposition of MDs from MAYV (gray; PDB 5IQ5), CHIKV (orange; PDB 3GPG), SINV (blue; PDB 4GUA),and VEEV (beige; PDB 3GQE) showing also the degree of sequence conservation in four loops. (d) Representation of the electrostatic surface potential of MAYV MD (red, − 4; blue, + 4; calculated with the PyMol APBS extension). (e) S2 order parameters of the backbone of MAYV MD. Residues with values close to one have a decreased mobility on the ps/ns timescale. (f) Mapping of residues with slowly exchanging backbone amide protons in the core region of MAYV MD (dark red). The corresponding 1H,15N HSQC spectra at time points 11 and 1125 min of the H/D exchange experiment are shown below.

As expected, its structural homologs according to DALI database [49] are the MDs of CHIKV (PDB ID: 3GPG, Z score: 27, RMSD: 1.3 Å), Sindbis virus (SINV; PDB ID: 4GUA, Z score: 27, RMSD: 1.4 Å), and Venezuelan Equine Encephalitis virus (VEEV; PDB ID: 3GQE Z score: 24, RMSD: 1.7 Å), all of them exhibit significant topological similarities with MAYV MD. Structural differences between these proteins are mainly localized in four loop regions (β2–α1, α1–β3, β5–α3, β6–α4) (Fig. 1c), which are believed to be responsible for the catalytic properties [50] and the different affinities of MDs for ADP-r [51]. A striking example is the loop β2–α1 with only two conserved glycine residues, which is considered crucial for the catalysis [50] and adopts different orientations in the four structures.

Specifically, MAYV, CHIKV and SINV MDs have at position 31 Asp or Glu instead of Gly in the VEEV sequence, while position 35 is usually occupied by charged amino acids, such as Arg (MAYV and CHIKV) or Lys (SINV), in contrast to a Gly residue in the VEEV sequence. In addition, MAYV MD has Val and Ala at positions 29 and 38, respectively, whereas these positions are occupied by Pro and Tyr in the other three MDs.

The other three loops are important for ligand binding and exhibit ~ 30% sequence identity (Fig. 1c). Loop α1–β3 contains only a single conserved residue at position 45 (Phe) and exhibits different conformations in the four MDs. The only conserved residues of the loop β5–α3 are at its C-terminal end (Lys118, Asp119). The MDs of MAYV and CHIKV differ in three positions of this loop: 113 (Ile versus Val) 114 (Phe versus Tyr), and 116 (Ala versus Gly). Finally, the β6–α4 loop is the one with the highest number of conserved residues (four out of six residues) but plays only a minor role in ligand binding and catalysis.

Analysis of the electrostatic surface potential of MAYV MD identified a solvent accessible cleft surrounded by positively charged surface areas. Helices α1 and α4 and the loops connecting the secondary structure elements β1–β2–α1–β3 and β6–α4 contribute to the formation of this cleft that could serve as a binding site for negatively charged molecules such as RNA or (Poly-) ADP-r. The opposite side of MAYV MD is negatively charged (Fig. 1d).

Dynamic properties of MAYV MD

The dynamic properties of the polypeptide on the ps/ns timescale were derived from 15N R 1 and R 2 relaxation rates and the heteronuclear {1HN}–15N NOEs (Fig. S1) (average values of 1.53 ± 0.19 s−1, 14.14 ± 2.52 s−1 and 0.84 ± 0.04, respectively, for residues 2–159). The correlation time for isotropic tumbling in solution as calculated from the R 2/R 1 ratio is 8.8 ns, which roughly corresponds to MW ~ 17.6 kDa (theoretical MW 18.1 kDa) and clearly indicates that the protein is a monomer in solution. Calculation of the S 2 order parameter (Fig. 1e) showed that the N- and C-terminal regions of MAYV MD are as rigid as most of the protein. Increased mobility on the ps/ns timescale was only found for three segments, which comprise the loops β2–α1 (Gly32-Val33), β4–α2 (Ser77-Ala79), and β5–α3 (Ser115–Gly117). Note that signals of the neighboring residues Gly30–Asp31, Cys34–Ala36, Ala38, Gly112–Phe114 and Asp119–Arg120 are broadened beyond detection in the 1H,15N heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) spectrum of the apo form of MAYV MD. Thus, their 1H,15N correlation peaks could not be assigned, strongly suggesting that the loops upstream to helices α1 and α3 undergo conformational exchange processes that may be relevant for the selectivity of substrate binding [52]. These data support the plasticity of two functionally important loops (Fig. 1c). According to our NMR data, the MAYV MD loop β2–α1 seems to be more dynamic (lower S 2 values and negative values {1HN}–15N NOEs, while at the same region, CHIKV exhibits only positive values; data not shown) than the corresponding segment of CHIKV MD (Fig. S2). In addition, the fact that the HN resonances of the neighboring residues mentioned above (Cys34–Ala36 and Ala38) remain unidentified while the HNs of the corresponding segment in CHIKV apo MD could be assigned [53] (Fig. S2c), shows that an exchange process on an intermediate NMR timescale is present in the β2–α1 loop of MAYV MD, but not in CHIKV MD.

An H/D exchange experiment in which a 15N-labeled sample was lyophilized and dissolved in 100% D2O provided additional information on the mobility of MAYV MD on the timescale of minutes to hours. All loops, helix α1 and the outer part of helix α4 as well as the first residues of strands β1 and β3 show complete exchange of the backbone amide protons in the first 11 min of the experiment (Fig. 1f) [54]. After an exchange time of 1125 min, the HN resonances of residues that belong to the solvent-inaccessible core of the protein, which is formed by specific parts of (i) strands β2 (Ala18–Val20), β4 (Ile65–Ile66, Ala68), β5 (Val104–Ile106), and β6 (Thr139–Tyr142) and (ii) helices α2 (Leu85–Ile96), α3 (Leu128–Met132), and α4 (Leu156–Gln157), are still visible (Fig. 1f). Hence, there is a stable hydrogen bond network in this rigid core region of MAYV MD, in contrast to the mobility of the majority of residues on the min/h timescale (Fig. 1f).

MAYV MD nucleotide selectivity and binding

A series of adenosine-based molecules was used to explore the ability of MAYV MD to bind adenosine derivatives as well as to elucidate the impact of individual chemical moieties on the MAYV MD–ligand interaction and the role of certain residues in ligand recognition. Titrations of MAYV MD with ADP-r, ADP, adenosine triphosphate (ATP), adenosine monophosphate (AMP) and NAD+ were monitored by acquisition of 1H,15N HSQC spectra and showed chemical exchange between free and ligand-bound MD ranging from fast to slow on the NMR timescale.

NMR titration of the MAYV MD with ADP-r suggests a strong interaction of both molecules and complex formation at 1:1 molar ratio (Fig. 2a). Furthermore, the analysis of the backbone amide chemical shift perturbations (CSPs) identifies the residues that are involved in this process (Fig. 2c and d). To this end, a complete backbone and side-chain resonance assignment of the MAYV MD–ADP-r complex was obtained (BMRB accession no. 27612). Specifically, residues Asp10, Ala23, Asn24, Gln28, Gly32, Val33, Lys56, Val69, Ser110 and Ala116 exhibited the largest CSPs while undergoing chemical exchange between the free and the bound form in the slow exchange regime (~ 0.1–1 s, k ex < <| Δν | and usually K d ≈ μΜ or lower [52]). In addition, adjacent amino acids like Ala9, Ala12, Thr13, Gly27, Val29, Asn72, Phe73, Leu109, Ser115 and G117 were also affected exhibiting a slow-exchange process during the interaction. The backbone HN resonances of Ile11, His25, Val37, Phe45, Ala68 and Lys146 broadened beyond detection, while those of Ala22, Gly30, Asp31, Cys34, Arg35, Ala36, Ala38, Gly112, Cys143 and Arg144, which were unassigned in the spectra of the apo MAYV MD, could be assigned in the 1H,15N HSQC spectrum of the MAYV MD–ADP-r complex. These data suggest that the majority of the residues, which participate in ligand recognition and binding, are located near the positively charged ligand-binding cleft (Figs. 1d and 2d). It is worth mentioning that upon binding of ADP-r, the backbone and side-chain resonances of residues in the loops that comprise the positively charged cavity are observable, while they were not detectable in the free state of the protein. All these findings prove the high-affinity interaction of MAYV MD with ADP-r and indicate ligand binding via loops β1–β2, β2–α1, β4–α2, and β5–α3, which should comprise or be located nearby the anticipated binding cleft (Fig. 2d) [52]. Most residues in these loops show relatively low-order parameters (Fig. 1e) or conformational averaging in the apo state.

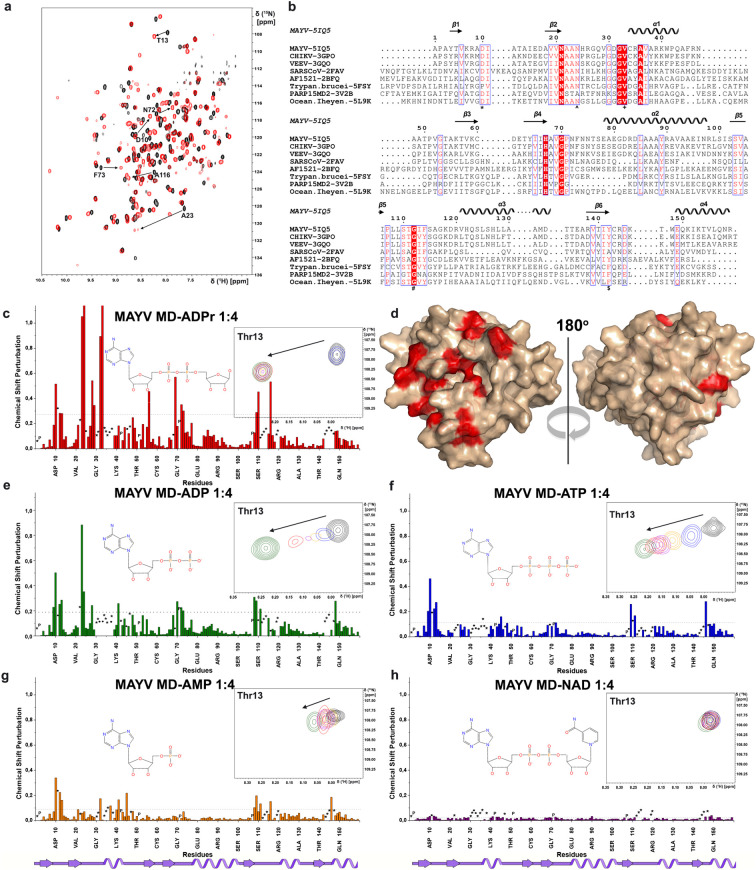

Fig. 2.

(a) Superposition of the 1H,15N HSQC spectra of MAYV MD in the absence (black) and presence of ADP-r at a 1:1 molar ratio (red). Arrows indicate the changes of the peak positions of characteristic amino acids. (b) Sequence alignment of PDB-deposited MD structures in complex with ADP-r; symbols below indicate the key residues that interact with the ADP-r molecule. (c, e, f, g, h) Plots of combined amide chemical shift changes, Δδ, induced by binding of adenine-based molecules to MAYV MD versus amino acid sequence at the given molar ratios of protein:ligand. In each plot, the dotted line indicates the applied threshold of chemical shift perturbation calculated as the average value plus 1 SD. An asterisk indicates an unassigned residue of apo-MD, p indicates a proline residue and a dot indicates a residue whose HN resonance could not be detected at each titration step. The Δδ values of Asn24 and Val33 in panel c (binding of ADP-r) are 2.2 and 3.8, respectively. Inset at right of each CSP plot: behavior of the amide peak of Thr13 during the titration indicating different binding regimes for the tested ligands (color code for the molar ratio protein:ligand: 1:0, black; 1:0.25, blue; 1:0.5, orange; 1:0.75, purple; 1:1, red; 1:3. green). (d) Surface representation of MAYV MD depicting in dark red the amino acids exhibiting CSP values above the threshold in the presence of ADP-r.

Then NMR data showed that the complex formation with ADP required a 1:3 (protein:ligand) molar ratio (no further chemical shift changes observed at higher ligand concentrations up to a 1:4 molar ratio) and that the exchange occurred in the intermediate time regime (k ex ~|Δν |), strongly suggesting that ADP interacts more weakly than ADP-r. Similar to ADP-r, the addition of ADP to MAYV MD induced the largest chemical shift perturbations in the loops connecting the β1 and the β2 strands (Ala9–Thr13), the β2 strand and the α1 helix (Ala23–His25), the β4 strand and the α2 helix (Asn72, Phe73), and the β5 strand and the α3 helix (Leu108–Thr111) (Fig. 2e). During the titration with ADP the HN resonances of Ala9, Asp10, Ala12, Thr13 (Fig. 2e, inset), Ala23–Gly27, Val37, Gly70, Leu108, Leu109, Thr111, Ser115 and Gly117 are shifted and broadened, exhibiting intermediate-to-fast exchange, different from the slow-exchange process that they undergo during interaction with ADP-r. The HN resonances of the residues Ile11, Gly32, Val33, Val37, Val69, Ser110 and Ala116 could not be identified at the final step of the titration due to broadening of the corresponding peaks, indicating chemical exchange processes on an intermediate NMR timescale (Fig. 2e).

ATP was subsequently tested as a putative ligand for MAYV MD to explore the role of the negatively charged phosphate groups. The complex formation is achieved at a molar ratio of 1:4 (protein:ligand) and led to smaller CSP values than the intermediate or slow chemical exchange during the titrations with ADP and ADP-r, respectively. However, the residues exhibiting CSPs are practically the same as in the case of ADP. Similarly, the 1H,15N HSQC cross peaks of Ile11, Ala23, Asn24, Gly32, Val33, Val69, Leu108, Ser110 and Ala116 remained broadened beyond detection even after the last addition of ATP (Fig. 2f). On the other hand, Asp10, a key residue for the ligand binding, is in the fast-exchange regime upon addition of ATP to MAYV MD. The same behavior was observed for the other key residues Thr13 (Fig. 2f) and Leu109. Therefore, the interaction can be characterized best as fast exchange on the NMR timescale (k ex > > | Δν |). Such an analysis of the binding kinetics can also provide an estimate of the binding affinity [52], [55], which in this case implies a weak binding with a K d of the order of ~ 10−3 M. Therefore, it may be concluded that ATP binds less tightly than ADP.

Titration of MAYV MD with AMP, the simplest adenosine derivative used in this study, was characterized by relatively small CSPs and fast exchange, while the affected regions are the same as with the other ligands. (Fig. 2g). As with ATP, Asp10 in the β1–β2 loop is in fast exchange and shows a prominent chemical shift change. Note that Ala23 in the β2–α1 loop whose HN resonance was broadened beyond detection during the ATP titration was observed up to the last stage of the titration with AMP. Moreover, the CSP of Val37 in the first turn of helix α1 could be followed at all titration steps for the first time. Ala116 in the β5–α3 loop showed slow exchange with ADP-r, intermediate exchange in the titrations with ADP and ATP, but fast exchange in the case of AMP. These observations exemplify the adaptability of MAYV MD to adenosine-based ligands.

Titration of MAYV MD with NAD+ up to a molar ratio of 1:4 (protein:NAD+) had only a minor influence on the 1H,15N resonances of the protein indicating that NAD+ exhibits the weakest interaction among the five nucleotides tested. The intensities of the cross peaks of Ala23, Asn24, Gly32 and Ser110 are decreased or broadened beyond detection at the final step of titration. These observations indicate that despite the weak protein–NAD+ interaction, these residues are affected more by the addition of NAD+ than by AMP. The segments influenced by NAD+ are the β1–β2 loop, the β5–α3 linker, the C-terminal end of the β6–α4 loop and the first α4 residues (Fig. 2h). Although NAD+ interacts only weakly with the protein, it is the only ligand that induces CSPs above threshold (lower than the threshold of any of the other four nucleotides) for the backbone HN resonances of Gln43 and Ala44 at the C-terminus of helix α1, suggesting a different interaction interface for the relatively bulky NAD+ (Fig. S3).

The screening of adenosine-based molecules for their potential binding to MAYV MD revealed that ADP-r exhibits the strongest interaction and forms a 1:1 complex. In addition, the role of individual chemical moieties of the ADP-r molecule can be evaluated through a comparative analysis of the ligand-induced chemical shift changes (Figs. 2 and S3). The ligands used (ADP-r, ADP, ATP, AMP and NAD+) differ in each case in the chemical group connected to adenosine, thus allowing to elucidate the contribution of each moiety to the chemical shift changes. Absence of the terminal ribose moiety has a significant effect on the interaction, since ADP-r is the only MAYV MD ligand leading to a slow-exchange process on the NMR timescale (k ex < < | Δν |). In general, ADP and AMP interact with the same residues of MAYV MD, but interestingly, the residues that interact with the β-phosphate group of ADP can be identified clearly. According to the literature [50], there are two structural water molecules that are H-bonded to the β-phosphate. In the crystal structures of the MDs from Oceanobacillus iheyensis (PDB ID: 5L9K) and CHIKV (PDB ID: 3GPO) in complexes with ADP-r, these water molecules interact with the conserved residues Ala29, Gly91 and Ala23, Gly70, respectively. Ala23 and Gly70 in MAYV MD exhibit much smaller CSPs (Fig. 2g and e) and undergo a fast-exchange process upon the addition of AMP compared to ADP, indicating an active role in the binding of the second phosphate group.

AMP and especially NAD+ exhibit weak interaction. The addition of a substituted pyridine ring to the distal ribose of ADP-r seems to impede the access of NAD+ to the binding cavity of the smaller adenosine derivatives.

Identification of MAYV MD residues critical for ADP-r binding through NMR and ITC

To further characterize the MAYV MD–ADP-r interaction, MD mutants were designed considering the most affected regions in the CSP analysis (Fig. 2c) as well as available crystal structures of MD–ADP-r complexes [25], [27], [28], [50], [56], [57] from various organisms. These structures reveal conserved patterns of amino acids that mediate the interaction of ADP-r with the protein (Fig. 2b). According to these models, the NH2 group of adenine forms a hydrogen bond with the carboxyl group of an aspartate (Fig. 2b, indicated with “⁎”) at the beginning of the β1–β2 loop. The hydrophobic residue (Ile/Val) following this aspartate is also hydrogen-bonded to adenine via its backbone amide group. In several homologous structures (e.g., PDB ID: 2BFQ), an aromatic residue (Tyr/Phe) (indicated with “$” in Fig. 2b) is found to stabilize further the adenine through π–π stacking to its purine ring. The phosphate groups are connected through their oxygen atoms to the backbone amides of residues in two conserved sequence motifs around almost invariable Gly residues. The first motif is a Gly followed by Val/Leu just before helix α1 (Fig. 2b, indicated with “+”), and the second one is Ser/Gly–X/Thr–Gly–Ile/Val/Asn–Tyr/Phe/Leu/Ala in the β5–α3 loop (Fig. 2b, indicated with “#”). Finally, the distal ribose is stabilized by a hydrogen bond to an Asn residue in the β2–α1 loop (Fig. 2b, indicated with “˄”) [56], [57], [58], [59]. These residues, namely, Asp10/Ile11, Gly32/Val33, Gly112 and Asn24, are also present in MAYV MD (Fig. 2b) and interact with ADP-r as clearly shown by our CSP data (Fig. 2c and Fig. S3a).

Surprisingly, the weakly conserved residues Asn72 and Phe73, in the β4–α2 loop, are also strongly affected by the binding of ADP-r indicating a rearrangement of this loop.

The impact of residues Asp10, Asn24 and Phe114 on the binding of ADP-r to MAYV MD was examined by means of three mutants: D10A, N24A/F114A and the triple mutant D10A/N24A/F114A. Titrations of all mutants with ADP-r were followed by the acquisition of 1H,15N HSQC spectra (Fig. 3a). The comparison of the number of shifted backbone amide signals qualitatively showed that all mutants bind ADP-r more weakly than WT (with the triple mutant losing completely the ability to bind ADP-r), strongly supporting the implication of the three mutated residues in the interaction.

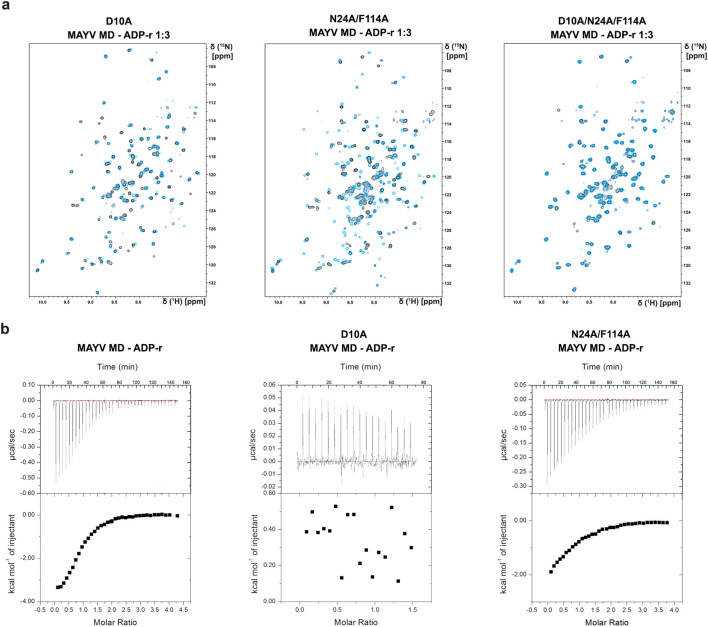

Fig. 3.

(a) Superposition of the 1H,15N HSQC spectra of MAYV MD mutants (D10A, N24A/F114A, D10A/N24A/F114A) in the absence (black) and presence of ADP-r at a 1:3 molar ratio (cyan). (b) ITC data demonstrating the binding of ADP-r to MAYV MD (WT and mutants D10A and N24A/F114A). The corresponding Kd values were 10.9 μM for WT and 52.1 μM for N24A/F114A. For the D10A mutant, a Kd value could not be calculated.

Then, the ADP-r binding properties of three MAYV MD variants were quantified using ITC (Fig. 3b). For MAYV MD WT, the results confirm a 1:1 stoichiometry. The obtained dissociation constant K d is 10.9 ± 0.7 μΜ, while the NMR titration data show a slow-exchange process between free and ADP-r-bound MD. Thus, the slow exchange on the NMR timescale coincides with a relatively strong binding event (Fig. 2c). The binding is enthalpically favored (ΔΗ = − 3993 ± 68.55 cal/mol, ΔS = 9.09 cal/mol/K) indicating the formation of a complex through hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions. The K d for the N24A/F114A mutant is 52.1 ± 3.8 μΜ (ΔΗ = − 2853 ± 123.4 cal/mol, ΔS = 9.86 cal/mol/K). In the case of the D10A mutant and ADP-r, the titration curve could not be fitted by a binding isotherm and no K d value was obtained. This fact emphasizes the key role of the conserved residue Asp10 for ADP-r recognition and binding (Fig. 3b).

Interaction of MAYV MD with RNA oligonucleotides

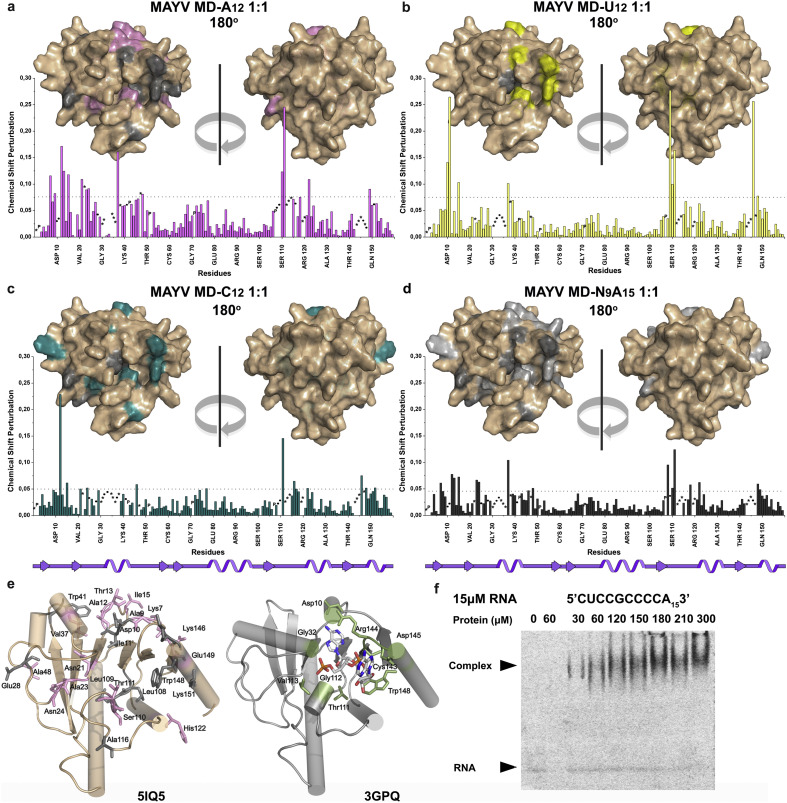

To gain insights into the RNA binding properties of MAYV MD, NMR titration studies and CSP analyses (Fig. 4a, b, c, d and e) were performed to probe the interaction of 15N-labeled MAYV MD with the following RNA substrates: (1) an artificial poly-A tail mimicking natural mRNA (N9A15, a 24mer with the sequence 5’CUCCGCCCCA153’) and (2) 12mers of adenine (A12), cytosine (C12), guanine (G12) and uracil (U12) to investigate the specificity of RNA base recognition. Each titration was conducted up to a 1:1 molar ratio of protein:RNA oligonucleotide.

Fig. 4.

(a–d) Plots of combined amide chemical shift changes, Δδ, induced by the binding of RNA oligos to MAYV MD versus amino acid sequence at a 1:1 molar ratio of protein:RNA oligo (pink-A12, light yellow-U12, dark cyan-C12, gray-N9A15). In each plot, the dotted line indicates the applied threshold of chemical shift perturbation calculated as average value plus 1 SD. The surface representations above each plot show the amino acids exhibiting CSP values above the threshold upon binding of the respective RNA oligo to MAYV MD (color code: pink, A12; light yellow, U12; dark cyan, C12; gray, N9A15) and those with broadened amide cross peaks (in dark gray). An asterisk indicates an unassigned residue of apo-MD, p indicates a proline residue and a dot indicates a residue whose HN resonance could not be detected at each titration step. (e) Left: The amino acids of MAYV MD that are critical for binding of the A12 oligo were mapped on its solution structure using only the amino acids with CSPs above the threshold (shown as pink sticks) and those, whose signals broadened beyond detection during the titration (in gray). Right: Representation of the residues (green sticks) that bind the A3 molecule in the CHIKV MD-A3 complex (PDB 3GPQ). (f) Gel shift assay (EMSA) probing the interaction of MAYV MD with the 24mer 5’CUCCGCCCCA153’ (= N9A15). The protein concentrations used are indicated above the gel.

The CSP analyses were carried out for four out of five tested RNA oligonucleotides. There were no clear results for the NMR titration with the G12 oligonucleotide due to the intensity loss of all HN resonances at the final step of the titration and precipitation of the sample. However, it should be noted that the first affected signals, at a MAYV MD:G12 ratio of 1:0.25, correspond to amino acids located at the periphery of the ADP-r binding pocket (His25–Glu28, Lys40–Trp41, Glu43, Val52, Asn97, Ser110, Gly117, Arg138, Lys146, Gln157). Denaturing PAGE analysis (data not shown) revealed that the precipitate consisted of both protein and RNA. Similar observations have been reported for SUD-M and SUD-MC domains of SARS-CoV, which have also an MD fold [60].

The NMR data showed that the addition of the four RNA oligonucleotides affects the same regions of the polypeptide. In particular the largest CSPs were observed for amino acids in or at the periphery of the positively charged ligand-binding cavity. It is worth mentioning that the presence of the RNA ligands affects residues in this binding cleft, but not in other surface areas of the MD molecule, suggesting specificity of the interaction, which is most likely driven by electrostatic attraction between positively charged surface residues of MD and negative charges of the RNA phosphate groups (Figs. 4a–d and S4).

The interactions between MAYV MD and A12 and N9A15 influence more amino acids (14 residues with CSPs above threshold and 10 HNs broadened beyond detection for A12; 17 residues with CSPs above threshold and 10 HNs broadened for N9A15) compared to U12 (9 CSPs above threshold and 2 HNs broadened) and C12 (10 CSPs above threshold and 8 HNs broadened. In agreement with literature data [27], this finding strongly suggests that MD exhibits higher affinity to the adenine oligonucleotides (N9A15 and A12) than to U12 and C12. Note that the latter oligonucleotides also influence MAYV MD residues in the two loops that seem to surround the negatively charged phosphate groups in the case of ADP-r binding (β2–α1 and β5–α3) [25], [27], [28], [50], [56], [57].

The MD binding surface of A12 is mainly defined by connecting loops and parts of helices α1 and α4. Specifically, the interaction surface is formed by the β1–β2 loop (Lys7, Asp10, Ile11, Ala12, Thr13, Ile15), residue Ala23 in the β2–α1 loop, the amino acids Val37 and Trp41 in the α1-helix, Ala48 in the α1–β3 loop, the residues Leu109, Ser110, Ile111, Ala116, Lys118 in the β5–α3 linker and the amino acids just before and at the beginning of helix α4 (Lys146, Trp148, Glu149). The same areas are affected by N9A15.

A comparison of the interaction data of A12 with the crystal structure of CHIKV MD (PDB ID: 3GPQ) [27] in complex with an A3 RNA oligonucleotide reveals that in both cases the same protein regions participate in the interaction (Fig. 4e). The higher number of amino acids that are influenced in the MAYV MD is due to the bigger size of the RNA oligonucleotide used here.

Complementary to the NMR titrations, EMSAs were conducted to verify the above-mentioned results. Three out of five single-strand RNA oligonucleotides, namely, N9A15 (5’CUCCGCCCCA153’), A12 and G12 were tested. Since MAYV MD does not enter the polyacrylamide gel under the tested condition (theoretical pI: 9.1), the EMSA results were evaluated in terms of the complex detection. The experiments showed that there is a concentration-dependent complex formation of MAYV MD with N9A15 (Fig. 4f). Moreover, binding was observed for A12 and G12 (Fig. S6).

To characterize further the selectivity of MAYV MD for nucleotides, we monitored titrations of the protein with GDP, CDP and UDP through 1H,15N HSQC spectra (CSP plots in Fig. S5). While the addition of CDP and UDP barely causes shifts to the 1H,15N resonances of MAYV MD suggesting that there is no interaction, GDP is apparently bound weakly. The interaction with GDP occurs in the fast-exchange regime, and there are only five residues with significant chemical shift changes: Ile11, Gly32, Leu109, Tyr142, and Lys146 (Fig. S5b). Compared to ADP binding (Fig. S5a), the CSPs are much smaller, no resonances are broadened beyond detection, there are no meaningful CSPs for residues Ala23–Asn24 and Val69–Asn72, and the key residue Asp10 is only minimally involved in the interaction. According to the available x-ray models [25], [50] in the presence of ADP, the carboxyl group of Asp10 of MAYV MD is most likely hydrogen-bonded to the NH2 group of adenine. However, if the orientation of the two nucleotides in the MAYV MD binding cleft were the same, this carboxyl group would repel the carbonyl oxygen on the C6 atom of guanine, which may explain the weaker interaction of GDP observed here. On the other hand, Ile11 usually forms a hydrogen bond to the base moiety of ADP and is still found to interact with GDP.

The data presented here indicate that both nucleotides and RNA oligonucleotides interact with MAYV MD. Our NMR data clearly identify the MD surface region involved in these biomolecular interactions. Adenine-rich RNA and ADP-r make use of the same binding cleft to dock onto the protein, but in the case of RNA binding, the α4 helix is additionally involved in the interactions. The observed interactions of MAYV MD with C12 and U12 RNA oligonucleotides are driven putatively by electrostatic attraction. This hypothesis is based on the absence of interaction between CDP or UDP and MAYV MD (Fig. S5c and d). The oligonucleotides C12 and U12 seem to bind to the positively charged cleft of the protein (Fig. 4b and c) due to their increased negative charge compared to the diphosphate nucleotides.

Concluding Remarks

Overall, this work reports the first solution structure of MAYV MD and identifies the protein residues involved in selective binding of ADP-r and adenine-containing ssRNA oligonucleotides to MAYV MD. This selectivity characterizes a number of MDs, and data reported herein show that MAYV MD shares structural and functional features with other Alphavirus MDs. The MAYV MD polypeptide folds into a well-ordered structure in solution, characterized by the β/α/β “sandwich” topology and peptide segments with functionally relevant intrinsic flexibility. These segments surround a well-defined binding pocket, which provides high selectivity and variable affinity toward adenosine derivatives and adenine-rich RNA oligonucleotides, with a preference for ADP-r. The critical role [27] of Asp10 for ligand binding is confirmed by a dramatic reduction of binding affinity upon its mutation to Ala. Moreover, this study demonstrates that non-conserved residues in loop regions, like β2–α1, α1–β3 and β5–α3, induce different local conformations and backbone dynamics in MAYV MD compared to other homologous MDs, thus customizing its ligand binding properties. This finding may represent a general principle in the structure–function relationship of viral MDs and precludes the prediction of ligand interactions and function on the sole basis of sequence homology [30], [51]. Note that ADP-r binding has recently been correlated in different cell lines with immediate or slow viral replication [42].

According to the literature, there are striking examples of highly homologous MDs with distinct function, such as those from (a) CHIKV and Semliki Forest virus (SFV) and (b) group 1 and group 3 CoV. In the former case, the two MDs have ~ 77% sequence identity, but SFV does not bind ADP-r [30]. In the latter case, a group 3 CoV MD exhibits great structural similarity to a group 1 CoV MD, but does not bind ADP-r, whereas the group 1 CoV MD binds ADP-r with a K d in the μΜ range [61], [62]. A similar finding has also been reported for MDs of the Alphavirus family. Some of us have observed different binding properties for the two MDs from VEEV and CHIKV, when they attempted to form the a MD–ADP-r complex [27]. VEEV MD, which has 59% sequence identity with CHIKV MD, did not bind ADP-r due to an unfavorable reorientation of the N24 and F114 side chains, when VEEV crystals were soaked with ADP-r. This finding suggests that even minor conformational differences in the loops β2–α1 and β5–α3 (Fig. 1c) can fine-tune the substrate binding capacity of closely related MDs. The differences in structure and mobility of the MAYV MD loops β2–α1, α1–β3 and β5–α3 with respect to CHIKV (Figs. 1c, S1 and S2) provide new insights into the structural basis of the functional role of these MD polypeptide segments. In addition, the structure elucidation of the MAYV MD along with the NMR driven interaction studies between the MD and ssRNA defines the positively charged surface illustrated in Fig. 1d, which represents another binding site, distinct from the ADP-r binding crevice, and its role in binding negatively charged biopolymer(s) (Fig. 4). These results are in line with the different roles of MD during the early and late stages of viral replication, in which a multi-functional domain is likely required [37]. The observations presented here enlighten the structural and physicochemical determinants of MD-ligand interactions and provide valuable functional insights into the MD of this neglected virus reinforcing the efforts to design novel structure-based inhibitors of this Alphavirus protein domain.

Methods

Expression and purification of MAYV MD and its variants

The construction of the recombinant vector containing the gene of MAYV MD, the purification procedure of the protein and the preparation of the labeled samples are described elsewhere [46]. The TRVL 4675 strain used in this study has a Thr at position 5 of the polypeptide sequence (GenBank MK070492.1).

In order to obtain high purity for the binding assays, a size exclusion chromatography was added using a Superose 12 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare) on an Äkta Purifier system (GE Healthcare) with 10 mM HEPES, (pH 7.0) and 20 mM NaCl as elution buffer.

The fractions containing MAYV MD were pooled and concentrated to a final volume of 500 μL. The solution was then supplemented with 50 μL of D2O and DTT was added to a final concentration of 1–2 mM. The protein concentration in the NMR samples that were used for the titrations varied from 0.1 to 0.6 mM.

The MAYV MD mutants (D10A, N24A/F114A; D10A/N24A/F114A) were obtained by PCR mutagenesis reaction using the plasmid containing the MAYV MD native gene as template and primers carrying the appropriate mutated codons. The expression and purification of the mutants were done according to the protocol for the native form of the protein.

Structure determination

All NMR experiments were recorded at 298 K on a Bruker Avance 600-MHz NMR spectrometer, equipped with a cryogenically cooled pulsed-field gradient triple-resonance probe (TXI), and on a Bruker Avance III High-Definition four-channel 700-MHz NMR spectrometer equipped with a cryogenically cooled 5 mm 1H/13C/15N/D Z-gradient probe (TCI) (acquisition parameters in Table S1). All chemical shifts were referenced to internal 2,2-dimethyl-2-silapentane-5-sulfonic acid (DSS) [46].

The NMR data were processed with the TOPSPIN 3.3 software and analyzed with XEASY [63] and CARA [64]. Distance constraints for structure determination were obtained from 15N- and 13C-edited 3D nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy (NOESY)–HSQC experiments and 1H–1H 2D NOESY spectra, all recorded on the 700-MHz NMR spectrometer. Eighty-four torsion angle constraints used in the structural calculations were derived from TALOS+ [65]. Structure calculations were then performed through iterative cycles of DYANA [47], followed by restrained energy minimization with AMBER [48] applied to each member of the final family of 20 DYANA models and the average model.

The NMR solution structure is characterized by a target function tf = 0.73 ± 7.87 × 10−2 Å2 and RMSD values of 1.07 ± 0.14 and 1.84 ± 0.14 Å for backbone and heavy atoms, respectively (Table S2). The coordinates of the energy-refined models (21 models, including the energy minimized average model) along with the structural constraints were deposited in the RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB ID: 5IQ5). A small number of backbone and side-chain dihedral angles exhibit non-favorable values due to minor gaps in the assignment and missing experimental data.

All figures showing structures were generated using PyMol [66].

15N-relaxation studies

Relaxation experiments (15N T1, T2 and {1HN}–15N NOE) were conducted using the aforementioned spectrometers at 298 K. The delays for the 15N T1 were 7, 18, 40, 85, 150, 230, 350, 500, 680 and 900 ms, while delays of 16.99, 33.98, 50.98, 67.97, 84.96, 101.95, 135.94, 186.91 and 220.9 ms were used in the 15N T2 experiments. The model-free approach in the TENSOR CEA/CNRS60 program was used in order to obtain the S 2 values. The S 2 values of MAYV MD are presented in Fig. 1e, while comparison of the S 2 values of the MDs from CHIKV and MAYV is shown in Fig. S2.

A H/D exchange experiment was performed with MAYV MD by dissolving a lyophilized sample of fully protonated uniformly 15N-labeled protein in 100% D2O and recording a series of 1H,15N HSQC spectra at 298 K on the 600-MHz NMR spectrometer. Each HSQC spectrum lasted 14 min 40 s, and the midpoint of acquisition of the first spectrum was 11 min after dissolution of the sample in D2O.

NMR binding studies of ADP-r, nucleotides and RNA

The interactions of MAYV MD with adenosine-based ligands, GDP, CDP, UDP and ss RNAs were evaluated by comparing the 2D 1H,15N HSQC spectra in the presence and absence of each tested molecule. The titrations were incremental and a 1H,15N HSQC spectrum was recorded after each addition. The titrations were stopped when no further spectral changes were observed. Combined amide chemical shift perturbations were calculated using the equation: Δδ = [(Δδ HN)2 + (Δδ N/5)2]1/2 [67]. In order to apply a consensus approach for the identification of shifts that are large enough to be considered as indicators of the binding site in more than 10 interaction studies between MAYV MD and small molecules or RNA oligos, we always applied the widely used method to calculate a threshold value [68], [69], [70], [71]. This threshold is based on the calculation of the average CSP value and the SD σ and sets an unbiased criterion to detect the residues that are significantly involved in an interaction.

ITC

ITC measurements were performed at 293 K using a MicroCal ITC200 instrument (Malvern). Experiments were conducted in a buffer containing 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.5) and 150 mM NaCl. The protein concentration in the cell was between 80 μM (wt protein) and 120 μM (mutant protein), whereas the ADP-r concentration in the syringe was 600 to 800 μM. Heats of dilution were measured by injecting the ligand into the protein solution. Titration curves were fitted with the MicroCal Origin software, assuming a one-site binding model, and enthalpy (ΔH), entropy changes (ΔS), dissociation equilibrium constants (K d) and stoichiometry were extracted.

EMSAs

Purified MAYV MD was incubated with ssRNA oligomers in reaction buffer containing 20 mM Tris base (pH 7), 100 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mΜ EDTA and 1 mM DTT in DEPC H2O. The protein–nucleic acid mixtures were incubated at 37 °C for 15 min, followed by 30-min incubation at 25 °C. Then 6% glycerol was added, and the mixtures remained on ice for at least 15 min. The reactions were analyzed on 6% non-denaturing PAGE in the presence of 3 mM Tris-borate buffer (pH 8) at 80 V for 1 h at 4 °C.

Nucleic acid was detected by GelRed (Biotium) staining and visualized using a UV light source equipped with a digital camera. GelRed was washed out and protein was subsequently detected by Coomasie staining (Bio-Rad).

The concentration of each ssRNA transcript was 15 μM. MAYV MD was used in increasing concentrations of 30, 60, 120, 150, 180, 210 and 300 μM.

MAYV MD does not enter the polyacrylamide gel under the conditions used here due to its basic pI (calculated pI = 9.1). Therefore, it could not be detected by PAGE analysis. However, its complexes with RNA carry enough negative charge to enter the gel and to be observed as discrete bands.

Accession numbers

The backbone assignments of the MAYV MD have been deposited to the BMRB (Biological Magnetic Resonance Data Bank) under accession numbers 30043 (apo form of the protein) and 27612 (protein with ADP-r complex), while the 3D structural models have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (ID 5IQ5).

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. C. Stathopoulos and Dr. M. Apostolidi (Department of Medicine, University of Patras) for useful discussions and their support and help with EMSA, and Dr. B. Fakler (University of Freiburg) for continued support. EU FP7 REGPOT CT-2011-285950—“SEE-DRUG” project is acknowledged for financial support (D.B., G.A.S.) as well as for the purchase of UPAT's 700-MHz NMR equipment. The research work was supported by the Hellenic Foundation for Research and Innovation and the Greek General Secretariat for Research and Technology HFRI for a PhD Fellowship grant (A.C.T.; GA. no. 2430) and European program H2020 under the EVAg Research Infrastructure (grant agreement No. 653316). We also acknowledge partial support of this work by the project "INSPIRED - The National Research Infrastructures on Integrated Structural Biology, Drug Screening Efforts and Drug target functional characterization" (MIS 5002550), which is implemented under the Action "Reinforcement of the Research and Innovation Infrastructure", funded by the Operational Programme "Competitiveness, Entrepreneurship and Innovation" (NSRF 2014-2020) and co-financed by Greece and the European Union (European Regional Development Fund).

Edited by M.F. Summers

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2019.04.013.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

References

- 1.Strauss E.G., Strauss J.H. Academic Press; 2007. Viruses and Human Disease. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fauquet C.M., Mayo M.A., Maniloff J., Desselberger U., Ball L.A. Elsevier/Academic Press; London: 2005. Virus Taxonomy, VIIIth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ryman K.D., Klimstra W.B. Host responses to alphavirus infection. Immunol. Rev. 2008;225:27–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwartz O., Albert M.L. Biology and pathogenesis of Chikungunya virus. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2010;8:491–500. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forrester N., Palacios G., Tesh R., Savji N., Guzman H., Sherman M., Weaver S., Lipkin W. Genome-scale phylogeny of the alphavirus genus suggests a marine origin. J. Virol. 2012;86:2729–2738. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05591-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tesh R.B., Watts D.M., Russell K.L., Damodaran C., Calampa C., Cabezas C., Ramirez G., Vasquez B., Hayes C.G., Rossi C.A. Mayaro virus disease: an emerging mosquito-borne zoonosis in tropical South America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1999;28:67–73. doi: 10.1086/515070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodríguez-Morales A.J., Paniz-Mondolfi A.E., Villamil-Gómez W.E., Navarro J.C. Mayaro, Oropouche and Venezuelan equine encephalitis viruses: following in the footsteps of Zika? Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2017;15:72–73. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2016.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Santiago F.W., Halsey E.S., Siles C., Vilcarromero S., Guevara C., Silvas J.A., Ramal C., Ampuero J.S., Aguilar P.V. Long-term arthralgia after Mayaro virus infection correlates with sustained pro-inflammatory cytokine response. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2015;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vasconcelos P.F., Calisher C.H. Emergence of human arboviral diseases in the Americas, 2000–2016. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2016;16:295–301. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2016.1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mackay I.M., Arden K.E. Mayaro virus: a forest virus primed for a trip to the city? Microbes Infect. 2016;18:724–734. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2016.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lwande O., Obanda V., Bucht G., Mosomtai G., Otieno V., Ahlm C. Global emergence of alphaviruses that cause arthritis in humans. Infect. Ecol. Epidemiol. 2015;5 doi: 10.3402/iee.v5.29853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cavalheiro M.G., Costa L.S.D., Campos H.S., Alves L.S., Assuncão-Miranda I., Poian A.T. Macrophages as target cells for Mayaro virus infection: involvement of reactive oxygen species in the inflammatory response during virus replication. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2016;88:1485–1499. doi: 10.1590/0001-3765201620150685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kääriäinen L., Ahola T. vol. 71. Academic Press; Cambridge, MA: 2002. Functions of alphavirus nonstructural proteins in RNA replication; pp. 187–222. (Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pietilä M.K., van Hemert M.J., Ahola T. Purification of highly active alphavirus replication complexes demonstrates altered fractionation of multiple cellular membranes. J. Virol. 2018;92:e01852-17. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01852-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hellström K., Kallio K., Utt A., Quirin T., Jokitalo E., Merits A., Ahola T. Partially uncleaved alphavirus replicase forms spherule structures in the presence and absence of RNA template. J. Virol. 2017;91:e00787-17. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00787-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karpe Y.A., Aher P.P., Lole K.S. NTPase and 5′-RNA triphosphatase activities of Chikungunya virus nsP2 protein. PLoS One. 2011;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Das P.K., Merits A., Lulla A. Functional cross-talk between distant domains of Chikungunya virus non-structural protein 2 is decisive for its RNA-modulating activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:5635–5653. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.503433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Das I., Basantray I., Mamidi P., Nayak T.K., Pratheek B., Chattopadhyay S., Chattopadhyay S. Heat shock protein 90 positively regulates Chikungunya virus replication by stabilizing viral non-structural protein nsP2 during infection. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Russo A.T., White M.A., Watowich S.J. The crystal structure of the Venezuelan equine encephalitis alphavirus nsP2 protease. Structure. 2006;14:1449–1458. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Golubtsov A., Kääriäinen L., Caldentey J. Characterization of the cysteine protease domain of Semliki Forest virus replicase protein nsP2 by in vitro mutagenesis. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:1502–1508. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.01.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen M.W., Tan Y.B., Zheng J., Zhao Y., Lim B.T., Cornvik T., Lescar J., Ng L.F.P., Luo D. Chikungunya virus nsP4 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase core domain displays detergent-sensitive primer extension and terminal adenylyltransferase activities. Antivir. Res. 2017;143:38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2017.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Götte B., Liu L., McInerney G.M. The enigmatic alphavirus non-structural protein 3 (nsP3) revealing its secrets at last. Viruses. 2018;10:105. doi: 10.3390/v10030105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feijs K.L., Forst A.H., Verheugd P., Lüscher B. Macrodomain-containing proteins: regulating new intracellular functions of mono (ADP-ribosyl) ation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2013;14:443–451. doi: 10.1038/nrm3601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Han W., Li X., Fu X. The macro domain protein family: structure, functions, and their potential therapeutic implications. Mutat. Res. Rev. Mutat. Res. 2011;727:86–103. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karras G.I., Kustatscher G., Buhecha H.R., Allen M.D., Pugieux C., Sait F., Bycroft M., Ladurner A.G. The macro domain is an ADP-ribose binding module. EMBO J. 2005;24:1911–1920. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aravind L., Zhang D., de Souza R.F., Anand S., Iyer L.M. The natural history of ADP-ribosyltransferases and the ADP-ribosylation system. In: Koch-Nolte F., editor. vol. 384. Springer International Publishing; Cham: 2015. pp. 3–32. (Endogenous ADP-Ribosylation). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malet H., Coutard B., Jamal S., Dutartre H., Papageorgiou N., Neuvonen M., Ahola T., Forrester N., Gould E.A., Lafitte D. The crystal structures of Chikungunya and Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus nsP3 macro domains define a conserved adenosine binding pocket. J. Virol. 2009;83:6534–6545. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00189-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Egloff M.-P., Malet H., Putics Á., Heinonen M., Dutartre H., Frangeul A., Gruez A., Campanacci V., Cambillau C., Ziebuhr J. Structural and functional basis for ADP-ribose and poly (ADP-ribose) binding by viral macro domains. J. Virol. 2006;80:8493–8502. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00713-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li C., Debing Y., Jankevicius G., Neyts J., Ahel I., Coutard B., Canard B. Viral macro domains reverse protein ADP-ribosylation. J. Virol. 2016;90:8478–8486. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00705-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neuvonen M., Ahola T. Differential activities of cellular and viral macro domain proteins in binding of ADP-ribose metabolites. J. Mol. Biol. 2009;385:212–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.10.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shin G., Yost S.A., Miller M.T., Elrod E.J., Grakoui A., Marcotrigiano J. Structural and functional insights into alphavirus polyprotein processing and pathogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012;109:16534–16539. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210418109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Daugherty M.D., Young J.M., Kerns J.A., Malik H.S. Rapid evolution of PARP genes suggests a broad role for ADP-ribosylation in host–virus conflicts. PLoS Genet. 2014;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rack J.G.M., Perina D., Ahel I. Macrodomains: structure, function, evolution, and catalytic activities. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2016;85:431–454. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060815-014935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Atasheva S., Akhrymuk M., Frolova E.I., Frolov I. New PARP gene with an anti-alphavirus function. J. Virol. 2012;86:8147–8160. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00733-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eckei L., Krieg S., Bütepage M., Lehmann A., Gross A., Lippok B., Grimm A.R., Kümmerer B.M., Rossetti G., Lüscher B. The conserved macrodomains of the non-structural proteins of Chikungunya virus and other pathogenic positive strand RNA viruses function as mono-ADP-ribosylhydrolases. Sci. Rep. 2017;7 doi: 10.1038/srep41746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leung J.Y.-S., Ng M.M.-L., Chu J.J.H. Replication of alphaviruses: a review on the entry process of alphaviruses into cells. Adv. Virol. 2011;2011 doi: 10.1155/2011/249640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abraham R., Hauer D., McPherson R.L., Utt A., Kirby I.T., Cohen M.S., Merits A., Leung A.K., Griffin D.E. ADP-ribosyl-binding and hydrolase activities of the alphavirus nsP3 macrodomain are critical for initiation of virus replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2018;115:E10457–E10466. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1812130115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gupte R., Liu Z., Kraus W.L. PARPs and ADP-ribosylation: recent advances linking molecular functions to biological outcomes. Genes Dev. 2017;31:101–126. doi: 10.1101/gad.291518.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Althaus F.R., Hilz H., Shall S. Springer Verlag; Berlin: 2012. ADP-Ribosylation of Proteins. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hottiger M.O., Boothby M., Koch-Nolte F., Lüscher B., Martin N.M., Plummer R., Wang Z.-Q., Ziegler M. Progress in the function and regulation of ADP-ribosylation. Sci. Signal. 2011;4:mr5. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sharifi R., Morra R., Appel C.D., Tallis M., Chioza B., Jankevicius G., Simpson M.A., Matic I., Ozkan E., Golia B. Deficiency of terminal ADP-ribose protein glycohydrolase TARG1/C6orf130 in neurodegenerative disease. EMBO J. 2013;32:1225–1237. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lüscher B., Bütepage M., Eckei L., Krieg S., Verheugd P., Shilton B.H. ADP-ribosylation, a multifaceted posttranslational modification involved in the control of cell physiology in health and disease. Chem. Rev. 2017;118:1092–1136. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu C., Yu X. ADP-Ribosyltransferases and poly ADP-ribosylation. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2015;16:491–501. doi: 10.2174/1389203716666150504122435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bai P. Biology of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerases: the factotums of cell maintenance. Mol. Cell. 2015;58:947–958. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morales J., Li L., Fattah F.J., Dong Y., Bey E.A., Patel M., Gao J., Boothman D.A. Review of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) mechanisms of action and rationale for targeting in cancer and other diseases. Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr. 2014;24:15–28. doi: 10.1615/critreveukaryotgeneexpr.2013006875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Melekis E., Tsika A.C., Lichière J., Chasapis C.T., Margiolaki I., Papageorgiou N., Coutard B., Bentrop D., Spyroulias G.A. NMR study of non-structural proteins—part I: 1H, 13C, 15N backbone and side-chain resonance assignment of macro domain from Mayaro virus (MAYV) Biomol. NMR Assign. 2015;9:191–195. doi: 10.1007/s12104-014-9572-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Güntert P., Mumenthaler C., Wüthrich K. Torsion angle dynamics for NMR structure calculation with the new program Dyana. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;273:283–298. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pearlman D., Case D., Caldwell J., Ross W., Cheatham T., Ferguson D., Seibel G., Singh U., Weiner P., Kollman P. University of California; San Francisco: 1997. AMBER 5.0. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Holm L., Laakso L.M. Dali server update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:W351–W355. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zapata-Pérez R., Gil-Ortiz F., Martínez-Moñino A.B., García-Saura A.G., Juanhuix J., Sánchez-Ferrer Á. Structural and functional analysis of Oceanobacillus iheyensis macrodomain reveals a network of waters involved in substrate binding and catalysis. Open Biol. 2017;7 doi: 10.1098/rsob.160327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McPherson R.L., Abraham R., Sreekumar E., Ong S.-E., Cheng S.-J., Baxter V.K., Kistemaker H.A., Filippov D.V., Griffin D.E., Leung A.K. ADP-ribosylhydrolase activity of Chikungunya virus macrodomain is critical for virus replication and virulence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2017;114:1666–1671. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1621485114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ziarek J.J., Peterson F.C., Lytle B.L., Volkman B.F. Binding site identification and structure determination of protein–ligand complexes by NMR. Methods Enzymol. 2011;493:241. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-381274-2.00010-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lykouras M.V., Tsika A.C., Lichière J., Papageorgiou N., Coutard B., Bentrop D., Spyroulias G.A. NMR study of non-structural proteins—part III: 1 H, 13 C, 15 N backbone and side-chain resonance assignment of macro domain from Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) Biomol. NMR Assign. 2018;12:31–35. doi: 10.1007/s12104-017-9775-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kleckner I.R., Foster M.P. An introduction to NMR-based approaches for measuring protein dynamics. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2011;1814:942–968. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2010.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zuiderweg E.R. Mapping protein–protein interactions in solution by NMR spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 2002;41:1–7. doi: 10.1021/bi011870b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Haikarainen T., Lehtiö L. Proximal ADP-ribose hydrolysis in trypanosomatids is catalyzed by a macrodomain. Sci. Rep. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/srep24213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Forst A.H., Karlberg T., Herzog N., Thorsell A.-G., Gross A., Feijs K.L., Verheugd P., Kursula P., Nijmeijer B., Kremmer E. Recognition of mono-ADP-ribosylated ARTD10 substrates by ARTD8 macrodomains. Structure. 2013;21:462–475. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wojdyla J.A., Manolaridis I., Snijder E.J., Gorbalenya A.E., Coutard B., Piotrowski Y., Hilgenfeld R., Tucker P.A. Structure of the X (ADRP) domain of nsp3 from feline coronavirus. Acta Crystallogr. D. 2009;65:1292–1300. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909040074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Timinszky G., Till S., Hassa P.O., Hothorn M., Kustatscher G., Nijmeijer B., Colombelli J., Altmeyer M., Stelzer E.H., Scheffzek K. A macrodomain-containing histone rearranges chromatin upon sensing PARP1 activation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2009;16:923–929. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Johnson M.A., Chatterjee A., Neuman B.W., Wüthrich K. SARS coronavirus unique domain: three-domain molecular architecture in solution and RNA binding. J. Mol. Biol. 2010;400:724–742. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Piotrowski Y., Hansen G., Boomaars-van der Zanden A.L., Snijder E.J., Gorbalenya A.E., Hilgenfeld R. Crystal structures of the X-domains of a Group-1 and a Group-3 coronavirus reveal that ADP-ribose-binding may not be a conserved property. Protein Sci. 2009;18:6–16. doi: 10.1002/pro.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lei J., Kusov Y., Hilgenfeld R. Nsp3 of coronaviruses: structures and functions of a large multi-domain protein. Antivir. Res. 2018;149:58–74. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2017.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bartels C., Xia T.-h., Billeter M., Güntert P., Wüthrich K. The program XEASY for computer-supported NMR spectral analysis of biological macromolecules. J. Biomol. NMR. 1995;6:1–10. doi: 10.1007/BF00417486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Keller R. Cantina Verlag; Goldau, Switzerland: 2004. The Computer Aided Resonance Assignment Tutorial. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shen Y., Delaglio F., Cornilescu G., Bax A. TALOS +: a hybrid method for predicting protein backbone torsion angles from NMR chemical shifts. J. Biomol. NMR. 2009;44:213–223. doi: 10.1007/s10858-009-9333-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.DeLano W. Schrödinger LLC; 2010. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 2.0. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Williamson M.P. Using chemical shift perturbation to characterise ligand binding. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 2013;73:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lee S., Lee A.-R., Ryu K.-S., Lee J.-H., Park C.-J. NMR investigation of the interaction between the RecQ C-terminal domain of human bloom syndrome protein and G-quadruplex DNA from the human c-Myc promoter. J. Mol. Biol. 2019;431:794–806. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2019.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Xu J., Sarma A.V., Wei Y., Beamer L.J., Van Doren S.R. Multiple ligand-bound states of a Phosphohexomutase revealed by principal component analysis of NMR peak shifts. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:5343. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-05557-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Qi H., Cantrelle F.o.-X., Benhelli-Mokrani H., Smet-Nocca C., Buée L., Lippens G., Bonnefoy E., Galas M.-C., Landrieu I. Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy characterization of interaction of Tau with DNA and its regulation by phosphorylation. Biochemistry. 2015;54:1525–1533. doi: 10.1021/bi5014613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Contursi P., Farina B., Pirone L., Fusco S., Russo L., Bartolucci S., Fattorusso R., Pedone E. Structural and functional studies of Stf76 from the Sulfolobus islandicus plasmid–virus pSSVx: a novel peculiar member of the winged helix–turn–helix transcription factor family. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:5993–6011. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material