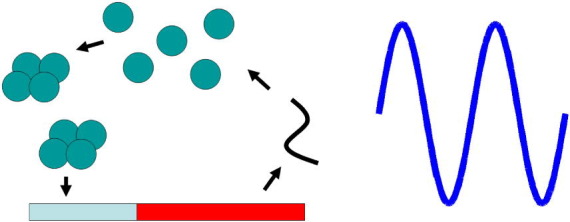

Graphical abstract

We observe reliable, coherent oscillation in a self-repressing gene with realistic cooperative binding and intermediate steps.

Abstract

Biological oscillators are vital to living organisms, which use them as clocks for time-sensitive processes. However, much is unknown about mechanisms which can give rise to coherent oscillatory behavior, with few exceptions (e.g., explicitly delayed self-repressors and simple models of specific organisms’ circadian clocks). We present what may be the simplest possible reliable gene network oscillator, a self-repressing gene. We show that binding cooperativity, which has not been considered in detail in this context, can combine with small numbers of intermediate steps to create coherent oscillation. We also note that noise blurs the line between oscillatory and non-oscillatory behavior.

1. Introduction

Biological oscillation and its mechanisms have recently become a subject of intense study by a number of experimental and theoretical groups. Its study is still in the early stages, and while the phenomenon itself is believed to be of great importance, knowledge of mechanisms by which it can occur is quite incomplete.

Oscillation is used in a number of biological systems, most notably in the circadian rhythms responsible for keeping organisms’ biochemical processes in line with the day–night schedule of the Earth. A number of mechanisms can be used by organisms to give a reasonably coherent oscillation, including three-gene repressilator systems [1], [2], [3], self-repressors with maturation times or other explicit, deterministic time delays (as opposed to intermediate steps which would result from a full treatment of chemical intermediates) [4], [5], [6], [7], more complex negative feedback loops tied to population dynamics [8] combined repression and activation loops [9], highly non-linear protein degradation [10], very large numbers (hundreds) of intermediate steps [11], and self-repressors whose production and gene repression involve diffusion through the nuclear membrane [12], [13]. A self-activator with one stable and one metastable state, and stochastic switching between the two, can cause what may be called incoherent oscillation [14]. Additionally, certain kinds of self-repression can cause behavior which is not coherent oscillation when one considers the deterministic average protein and mRNA concentrations, but which still appear quite oscillatory and reasonably coherent when one considers any given system’s stochastic trajectory through protein and mRNA concentration space over time [15].

This last example is of particular interest because in part of its simplicity; it is an uncomplicated system, easily modelled using straightforward Markov chain Monte Carlo methods. 1 There is, however, another reason for interest in the work. The binding mechanism suggested by the mathematics presented by McKane and Newman in Ref. [15] is in fact a combination of multiple n-mer bindings of regulatory proteins to the gene. In addition, the which n contributes most to the genetic activity here depends on the single parameter which McKane and Newman used to tweak their system and the average number of proteins present in the system. While this in itself may be non-physical, it inherently suggests that the number of bound proteins may be able to change the system from non-oscillatory to oscillatory with noise to (possibly) oscillatory even without noise.

We note that the simplest possible version of this last suggestion, a deterministic model with mRNA and with n regulatory proteins binding directly and instantaneously to the gene, cannot be oscillatory. A brief proof of this is included in the section on linear stability analysis (however, the stochastic version of the system can have oscillation-like behavior, and we explore this briefly).

2. Methods

We performed both deterministic and stochastic calculations. For ease of calculation and interpretation, the time units used were mRNA lifetimes (also monomer protein lifetimes). The following were constant for all calculations: the degradation rate of mRNA (hence, ); the degradation rate of monomer protein (hence, ); the rates of gene binding and unbinding (and so the system is very adiabatic); the ratio of the n-mer dissolution constant f to the formation constant h is ; the rate of n-mer dissolution in the simplest case, Fig. 1 , and in all other calculations; the number of complete n-mers which will cause the gene to be repressed by a factor of , ; the protein synthesis rate from a single strand of mRNA ; and the ratio of mRNA synthesis in the repressed versus the unrepressed gene state . It should be noted that and can be rescaled in systems without internal noise; only when the actual number becomes important, as opposed to relative concentrations, does do these quantities have any significant effect other than a rescaling. It should also be noted that the ratio is in rough agreement with the average for this sort of gene in yeast, given as approximately 2 in Ref. [16].

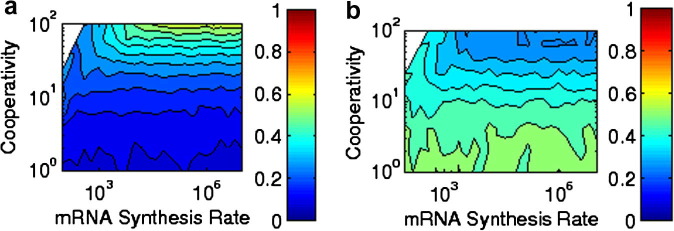

Fig. 1.

(a) Stochastic calculation of coherence in a system which has mRNA and proteins cooperatively binding to the gene, with coherence given by where is the difference in angle in mRNA–protein space. (b) Stochastic calculation of the standard deviation of the period distribution divided by its mean. Both colormaps are on the same scale as Fig. 3.

Deterministic calculations (involving the average numbers of mRNA, proteins, and protein aggregates) used the simple set of equations

where m is the number of mRNA molecules, is the probability or fraction of the time that the gene is repressed (unrepressed), p is the number of monomer proteins, and c is the number of n-mer proteins in the system at time t. Simple modifications made additional intermediate steps possible (c becoming , n becoming , additional terms in the last equation for the step, the extra equations for in terms of and , etc.).

We should also note that we assume all binding steps involved are fast compared to the other processes involved in the system, though binding events are relatively rare, and binding is highly cooperative. Slower binding, or binding that is less cooperative, can introduce very different elements to a system, as shown in Ref. [17].

The authors used time-series data to determine the oscillatory nature of the systems. A general solution to the linear stability analysis of the system would involve analytically solving an -degree polynomial with non-integer parameter-dependent coefficients, which is infeasible [18]. Even numerical solutions to the linear stability analysis problem alone could have glossed over complex behavior less useful to an organism than regular oscillation (i.e., chaos). However, individual points in different regions identified by the time-series data have been checked numerically using linear stability analysis. In the regime noted as ‘oscillatory’ via the time-series data, the Jacobian at the equilibrium point has one real negative eigenvalue and two complex eigenvalues with positive real parts, confirming that the point can be oscillatory. Outside that region, all three eigenvalues’ real parts are negative, confirming the non-oscillatory classification. We note that the line between the zones labeled ‘decaying oscillation’ and ‘no oscillation’ is much less well-defined than the line between those labeled ‘oscillation’ and ‘decaying oscillation’, as a system which displays decaying oscillation given one set of initial conditions can have no oscillations with another set of initial conditions. However, we believe the general trend is correct and useful, and so we indicate the distinction in the figure.

Stochastic calculations were straightforward, using the following equations:

In the calculations for Fig. 1 (in which binding to the gene is coupled with n-mer formation), we used

derived from the standard master equation rates of binding and unbinding f. For other stochastic calculations, in which the proteins bind to each other before binding to the gene, we used instead

A time-step dt was then calculated using these rates, ensuring that events generally occurred one at a time by using (this is subtly different from the traditional Gillespie simulation in that multiple events were in theory allowed, if quite unlikely; however, the difference is very small and may reasonably be considered to be an advantage of our algorithm.) For practicality’s sake, at very high levels of synthesis, multiple synthesis and decay events were allowed and occurred in the background of other events, but were kept to at most a 0.01% mean change in the number of molecules.

Each process was then treated as a Poisson process using the same dt, with the probability of a events of type b occurring being .

The programs used were written in C, and run using Fedora 10 Linux on a Dell desktop computer.

3. Linear stability analysis

We present, as an aside, a brief proof of the non-oscillation of the system described without delays. This system is described by the equations

The Jacobian of the system is given by

with eigenvalues that add to a real negative number and multiply to a real positive number. If the eigenvalues are complex, due to the result of multiplication they have the same real part. Due to this and the result of the addition, both eigenvalues must have negative real parts, meaning oscillation is impossible. If the eigenvalues are real, both must be negative, again making oscillation impossible.

It should be noted that we made these conclusions based on the structure of the Jacobian without finding the fixed point, based on the fact that there are only two eigenvalues. The more complex cases described in this work would have three or more eigenvalues, which would make finding the fixed point necessary. They also add to the complexity of the equations for finding the fixed point, which are already of degree with multiple terms and non-integer coefficients.

4. Results

We begin with the stochastic system described first, in which binding to the gene is coupled with n-mer formation (this could be either because the binding to the gene is itself cooperative or because it is very fast once the n-mer is formed). In the described regime, whose deterministic solutions yield at best decaying oscillation, we now explore the possibility of noise-induced oscillation. We note that the system in this case is between truly oscillatory and simply two-state with reasonably frequent switching. Simple two-state switching would lead to a ‘period distribution’ (time between maxima) with a normalized standard deviation of that period of . Fig. 1b shows , and Fig. 1a shows the coherence (generalized from the definition used in Ref. [2]). Coherence is defined as where is the angle in mRNA–protein space from the average concentration, and . It is, in essence, a measure of how often a system goes forward (clockwise) instead of backward (counterclockwise) in its oscillation. Both the coherence and strongly imply that increased cooperativity yields a steadier oscillatory behavior, but that in the regions explored there is no coherent oscillation (which would require a coherence close to 1 and a value of significantly less than 1).

So far, the only pieces of the puzzle considered have been multimer binding of proteins to genes, mRNA, and noise. We now add the final piece, the possibility of proteins binding together before they bind to the gene. The number of steps involved here keeps oscillation from occurring at a cooperativity of 1, but increased n causes oscillatory behavior when combined with the rest of the system.

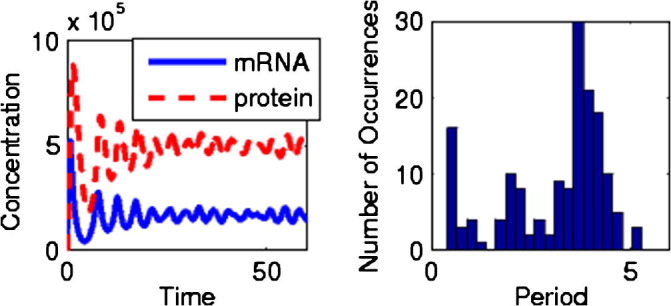

Specifically, Fig. 2 shows a stochastic system with and the distribution of periods, defined here as time between local maxima in protein number which are at least (in order to remove less significant fluctuations from consideration). This system is clearly oscillatory, with a reasonably sharp period distribution.

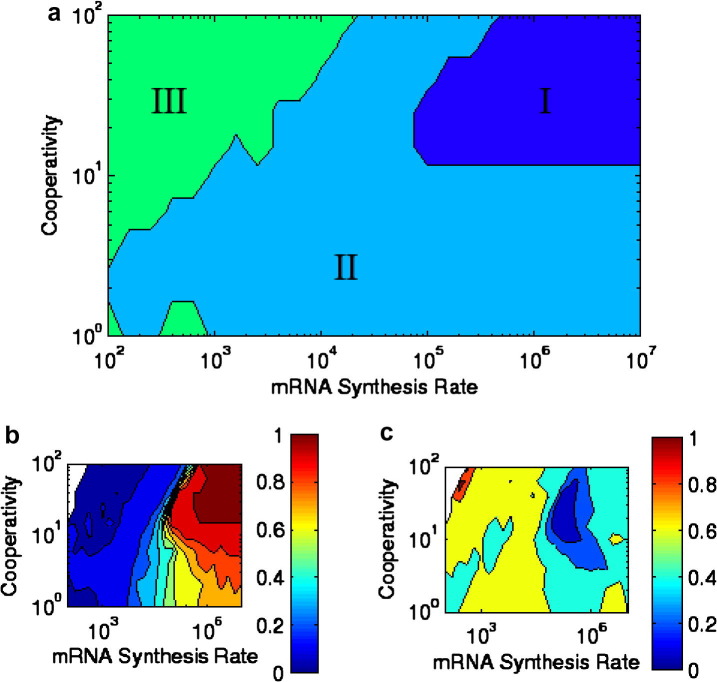

Fig. 2.

Left graph: oscillation due to an intermediate step with a cooperativity of 16 and noise. Right graph: period distribution for the same system.

It should be noted that 16 is at best a marginally reasonable value for cooperativity in a simple genetic system. However, it is clear now that simple intermediate steps can interact with cooperativity, and between them can produce oscillations in which neither is the primary factor in the behavior. Furthermore, examining the parameter space in more detail, we find telling behavior in both deterministic and stochastic cases. Fig. 3 a shows the deterministic phase diagram of the system, made using time-series calculations. Region I is oscillatory, region II displays decaying oscillation, and region III is non-oscillatory. High cooperativity and synthesis rate are both clearly necessary for this; also, it should again be noted that the additional intermediate step as compared with the system from Fig. 1 is necessary for deterministic oscillation.

Fig. 3.

(a) Deterministic calculation of oscillatory features in a system with mRNA, cooperative binding of proteins to each other, and a separate step binding to the gene; region I is oscillatory, region II has decaying oscillations, and region III is non-oscillatory. Due to the fact that the distinction betweeen II and III is somewhat dependent on initial conditions, there may be some overlap between those two regions as discussed in the Methods section. (b) Stochastic calculation of coherence, given by where is the difference in angle in mRNA–protein space. (c) Stochastic calculation of the standard deviation of the period distribution divided by its mean.

In Fig. 3b, we see, in the same region, a graph of the coherence. It corresponds well with the deterministic calculations: the system reliably goes in the correct direction (associated with time going forward) in the stochastic case when its parameters would predict that it is deterministically oscillatory. Fig. 3c shows , which again corresponds well, although not perfectly; some loss of specificity in period at very high cooperativity and synthesis implies that the oscillation may be imperfect or require that other parameters be very specific at some level. However, the increase in at these points is slight.

From these figures, it is apparent that coherence is possible with higher rates of synthesis, and that there is a tendency towards higher coherence with higher cooperativity. Additionally, we note that in the stochastic case there is no jump in coherence or as we would find if the system exhibited the phase-transition behavior from the deterministic system, Fig. 3a; in the stochastic case (Fig. 3b and c), the line between oscillatory and non-oscillatory is blurred. It is important to note that noise alone is not sufficient for reliable or even semi-reliable oscillation. The deterministically oscillating region clearly has more stable oscillation in the stochastic regime, and systems close to it are more capable of reliable behavior than those far away from it.

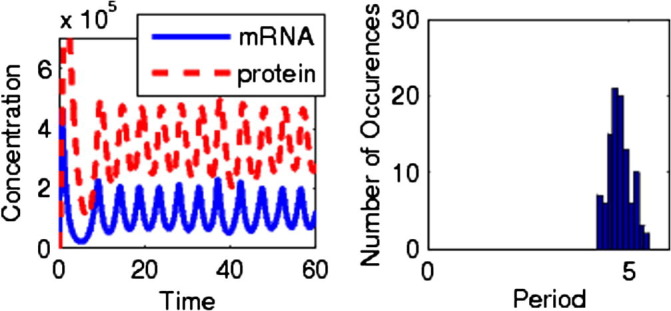

For comparison, we now choose a point in the region of deterministic decaying oscillations, and make plots comparable to Fig. 2. In Fig. 4 we see a system whose behavior seems similar in many ways; the main difference in this case is a slightly widened period distribution. While this system is definitely in region II of Fig. 3a (with a cooperativity of 8), and the period distribution may be too wide for a truly accurate clock, it is obvious that the line between coherent oscillation and incoherent oscillation-like behavior is blurred in this case by noise.

Fig. 4.

Left graph: behavior with small oscillatory tendencies due to an intermediate step with a cooperativity of 8 and noise. Right graph: period distribution for the same system.

We see in these figures that the optimal cooperativity for this number of intermediate steps in binding is still, at best, at the very high end of cooperativity in reasonable biological systems. Therefore, we have attempted a less complete search of parameters considering additional steps (instead of monomer to n-mer, monomer to dimer to tetramer, etc.). While our searches were not exhaustive, we found at least one region in which such a system can oscillate at quite reasonable values for n, as low as 8 (octamer). For reference, this is not an uncommon amount of cooperativity for these sorts of proteins. SARS–CoV nsp10, for instance, forms a dodecameric structure () [19]; Rhizobium leguminosarum NodD has been shown to bind to DNA preferentially in octamer form [20]; and phage CI, while it has a small autoregulatory effect with tetramer and even dimer forms, only fully represses itself when an octamer form of the protein links distant sites on DNA together [21].

5. Conclusions

Our data show that oscillation occurs when cooperativity and intermediate steps are both present, when neither cooperativity nor intermediates would otherwise be sufficient. More, it implies that, with many intermediate steps, lower cooperativity can yield oscillation, while with higher cooperativity fewer intermediate steps are necessary. Oscillation behavior in deterministic calculations gives rise to more stable oscillation in the stochastic case.

Additionally, it should be noted that, even though we found no coherent oscillation for lower values of cooperativity, moderate coherence in an oscillation-like behavior may not necessarily be detrimental to a biological system which relies on it as a clock for functions which are not truly vital. Many biological clocks receive input of some kind from outside sources, whether light and food for 24-h clocks or some other form [22], [23]. These inputs can reset a biological clock, and one may argue that they might be able to do so more easily in a fundamentally inexact clock than a single-mode oscillator.

In summary, we have discovered a relationship between generally realistic intermediate steps (as opposed to set-time time delays of the form , which are realistic for a limited set of systems), cooperativity, and oscillation. Intermediate steps resulting from slow cooperative binding can cause oscillation at biologically relevant cooperativity. We have also explored the noise effect, in which the line between oscillatory and non-oscillatory (relatively clear in the deterministic case) is blurred in the stochastic case.

Footnotes

Deterministic time delays of the type the most common method used to get a simple self-repressor to oscillate, can reproduce most results from other methods. However, for stochastics they require non-Markov simulation. Furthermore, while the equations are straightforward, the authors know of no way to determine a priori the numerical values of time delays that substitute for the delaying steps. The methods outlined in this Letter, in contrast, are purely Markov and involve only the actual chemical rates of the represented processes.

References

- 1.Elowitz M.B., Leibler S. Nature. 2000;403:335. doi: 10.1038/35002125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yoda M., Ushikubo T., Inoue W., Sasai M. J. Chem. Phys. 2007;126:115101. doi: 10.1063/1.2539037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim K.Y., Lepzelter D., Wang J. J. Chem. Phys. 2007;126:034702. doi: 10.1063/1.2424933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lewis J. Curr. Biol. 2003;13:1398. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00534-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mather W., Bennett M.R., Hasty J., Tsimring L.S. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009;102:068105. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.068105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stricker J., Cookson S., Bennett M.R., Mather W.H., Tsimring L.S., Hasty J. Nature. 2008;456:516. doi: 10.1038/nature07389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morant P.-E., Thommen Q., Lemaire F., Vendermoëre C., Parent B., Lefranc M. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009;102:068104. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.068104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Balagaddé F.K., You L., Hansen C.L., Arnold F.H., Quake S.R. Science. 2005;309(5731):137. doi: 10.1126/science.1109173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsai T.Y.-C., Choi Y.S., Ma W., Pomerening J.R., Tang C., Ferrell J.E.J. Science. 2008;231:126. doi: 10.1126/science.1156951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tyson J.J., Hong C.I., Thron D., Novak B. Biophys. J. 1999;77:2411. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77078-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morelli L.G., Jülicher F. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007;98:228101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.98.228101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldbeter A. Proc. Roy. Soc. B. 1995;261:319. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1995.0153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang J., Xu L., Wang E. PMC Biophys. 2008;1:7. doi: 10.1186/1757-5036-1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schultz D., Jacob E.B., Onuchic J.N., Wolynes P.G. PNAS. 2007;104:17582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707965104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McKane A.J., Nagy J.D., Newman T.J., Stefanini M.O. J. Stat. Phys. 2007;128:165. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shahrezaei V., Swain P.S. PNAS. 2008;105(45):17256. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803850105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Santillán M. Math. Model. Nat. Phenom. 2008;3(2):85. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fraleigh J.B. fifth edn. Addison-Wesley; Chennai: 1994. A First Course in Abstract Algebra. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Su D. J. Virol. 2006;80(16):7902. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00483-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Songtao L., Huafeng L., Guofan H. Sci. China C. 1998;41(6):592. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dodd I.B., Perkins A.J., Tsemitsidis D., Egan J.B. Genes Dev. 2001;15(22):3013. doi: 10.1101/gad.937301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aschoff J., Daan S. The Entrainment of Circadian Systems. vol. 12. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2001. (Handbook of Behavioral Neurobiology). p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Challet E., Caldelas I., Graff C., Pévet P. Synchronization of the molecular clockwork by light- and food-related cues in mammals. Biol. Chem. 2003;384:711. doi: 10.1515/BC.2003.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]