Abstract

Identifying the factors that shape protein expression variability in complex multi-cellular organisms has primarily focused on promoter architecture and regulation of single-cell expression in cis. However, this targeted approach has to date been unable to identify major regulators of cell-to-cell gene expression variability in humans. To address this, we have combined single-cell protein expression measurements in the human immune system using flow cytometry with a quantitative genetics analysis. For the majority of proteins whose variability in expression has a heritable component, we find that genetic variants act in trans, with notably fewer variants acting in cis. Furthermore, we highlight using Mendelian Randomization that these variability-Quantitative Trait Loci might be driven by the cis regulation of upstream genes. This indicates that natural selection may balance the impact of gene regulation in cis with downstream impacts on expression variability in trans.

Author summary

Genetic variation can change how much a gene is turned on or off in a tissue or a population of cells of the same type. However, this averaging of expression levels across a cell population masks an important aspect of gene expression regulation, namely its variability. Recent work in humans has indicated that nearby (cis) genetic factors minimally influence this variability. We have combined genetic measurements with flow cytometry single-cell protein levels to resolve the genetic control of gene expression variability in human immune cells. Importantly, we have demonstrated that whilst genetic variants near the target genes (cis) rarely influence variability, there is still an extensive genetic contribution from genetic loci faraway, or on a separate chromosome (trans). Furthermore, we have resolved that these trans genetic effects regulate the expression of other nearby genes, which leads to changes in gene expression variability of our target proteins. Our findings can be explained by an evolutionary balance between the cis regulation of gene expression levels, and the downstream consequences on gene expression variability.

Introduction

Cell-to-cell variability in gene expression levels is a ubiquitous feature of life on earth. This heterogeneity, broadly referred to as expression noise, is a function of transcriptional and translational regulation [1], as well as cellular state and environment [2–5]. The delineation of expression noise into “intrinsic” and “extrinsic” components [6] is mirrored by the separation of genetic influences on gene expression into cis and trans components. Intrinsic noise represents the differences in promoter output between two alleles of the same gene, whilst extrinsic noise represents all other sources of variability [6]. Intrinsic noise is largely attributed to the stochastic activation of a promoter that produces bursts of mRNA molecules [7]. The consequences of cell-to-cell expression variability (i.e. the sum of all noise sources [8]) manifest as therapeutic resistance in cancer [9,10], environmental adaptation in yeast [11] and prokaryotes [11,12], as well as lineage plasticity in murine T cells [5,13], to highlight just a few examples.

To understand the broader determinants of gene expression variability within and between cells, or organisms, previous studies have used targeted approaches to perturb individual genes [14], or probed how cis regulatory elements influence transcriptional dynamics [15–17], and how this is shaped by sequence variation, notably in yeast [11,14,15,18]. Additional mechanistic studies have uncovered the role of promoter architecture and distal regulatory elements in determining the magnitude of gene expression variability in mammals [19,20]. Moreover, several biological processes have been identified that influence gene expression variability in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes, including nuclear transport and post-transcriptional regulation [1,21]. However, with the exception of a recent CRISPR/Cas9-based screen [22], it has been hard to systematically evaluate the contributions of different biological processes to gene expression variability.

Quantitative genetics, and by extension genome-wide association studies, have been highly successful at providing novel insights into the biological pathways that influence complex phenotypes, including human diseases [23,24], and how they have been shaped by natural selection. We have combined a genome-wide quantitative genetics approach with single-cell protein measurements in the human immune system to elucidate the genetic architecture and regulation of cell-to-cell gene expression variability. Firstly, we demonstrate that expression variability differences between individuals are heritable. Conducting scans for common genetic variation in two independent cohorts of related (TwinsUK) and unrelated individuals (Milieu Intérieur), we identify trans genetic influences, distributed across the genome, on 155 protein expression variability traits—which we call variability-pQTLs. Curiously, we note fewer cis variability-pQTLs compared to mean expression QTL (97 vs 1210). The enrichment of trans variability-pQTLs around protein-coding genes indicates that they may act to influence the expression and dynamics of nearby genes in cis. Employing a Mendelian Randomization (MR) analysis we highlight specific examples where cis-eQTLs in immune cells contribute to cell-to-cell expression variability. These findings demonstrate the marked skew in cis vs. trans regulation of cell-to-cell gene expression variability, and suggest an evolutionary trade-off between noise control and the evolution of mean expression levels.

Results

A systematic evaluation of protein expression variability across the human immune system

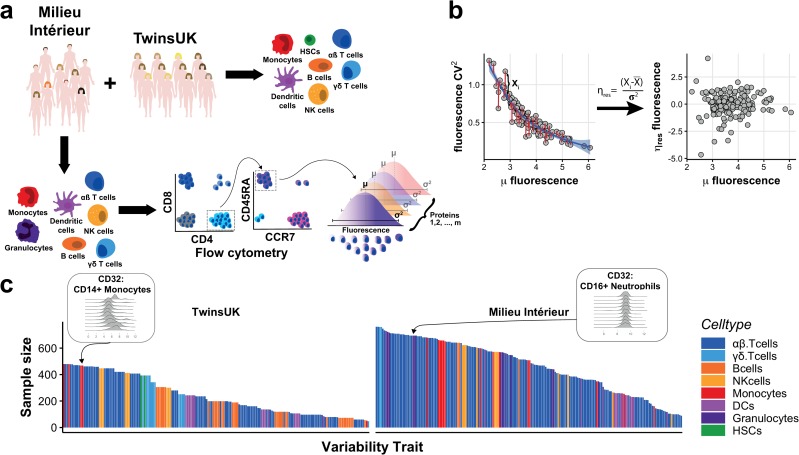

To quantify cell-to-cell protein expression variability we took advantage of two recently published immune-profiling flow cytometry studies in ~480 human twins (TwinsUK) [25] and ~1000 unrelated individuals from France (Milieu Intérieur) [26]. Flow-cytometry evaluates the expression level of target proteins at single-cell resolution using fluorescence-conjugated antibodies. This provides the ability to simultaneously define cell populations, and measure the cell-to-cell variability within each population across a number of target proteins [27], albeit semi-quantitively. We collated the flow-cytometry measurements across all sets of (previously validated) antibody panels in each study [26], which collectively targeted 47 proteins and 59 different peripheral blood immune cell (sub)types (Fig 1A, S1 Table).

Fig 1. Surveying cell-to-cell protein expression variability across the human peripheral blood immune system.

(a) Overview of the experimental design, showing how flow cytometry is used to profile immune cell type populations across multiple individuals from two cohorts. (b) Average expression and cell-to-cell protein expression variability are calculated for each cell type and protein combination (trait) in each individual (grey circles). Variability is quantified by the CV2 (y-axis left) which is inversely proportional to mean expression (x-axis). Using a local polynomial fit between the CV2 and mean (μ) expression, the mean-adjusted variability is taken as the standardised deviance from this fit (y-axis right, ηres). (c) Bar charts showing the sample size for each trait in the TwinsUK (left, range 48–479) and Milieu Intérieur cohorts (right, range 89–761) after quality control. Colours denote broad cell type categories—for details of specific cell types see S1 Table.

One of the largest known influences on expression variability between single cells is cell volume [28,29]. Therefore, we normalised all single-cell fluorescence measurements by their cell volume, after removing doublets, to remove any individual, technical, environmental or genetic influences on cell size from our study (Methods). Finally, to control for the previously described relationship between variability and gene expression [27] (S1 Note), we used a local polynomial regression to model the relationship between the mean and squared coefficient of variation (CV2) across individuals (separately in each cohort). Taking the standardised residuals, ηres, from this fit, yields a mean-adjusted measure of gene expression variability for each individual that is unconfounded with mean expression (Fig 1B).

Following quality control to remove fluorescence measurements on fewer than 100 cells, (see Methods), we calculated the mean and ηres for each individual for whom data were measured for a specific protein:cell-type combination (defined hereafter as a ‘trait’). In total we analysed 171 mean and 171 variability traits in the TwinsUK cohort, and 229 mean and 229 variability traits from the Milieu Intérieur study. This represents the richest survey of cell-to-cell protein expression variability in the human immune system to date (Fig 1C).

Estimating the influence of genetics and environment on protein expression variability in twins

Previous studies have observed inter-individual and inter-strain differences in gene expression variability in yeast and plants [30–32], and identified specific genetic variants that are correlated with protein expression variability in T cells [33]. However, none of these studies quantified the total genetic contribution to expression variability across proteins. Therefore, to estimate the extent to which heritable factors influence protein expression variability, we performed variance components analysis. Leveraging the known genetic relationships between mono and di-zygotic twins in the TwinsUK cohort we estimated the genetic, as well as shared (within family) and unique environmental components, for each of 171 variability traits. As a comparison we applied the same analysis to mean expression for 171 mean traits (Fig 2A, S1–S7 Figs).

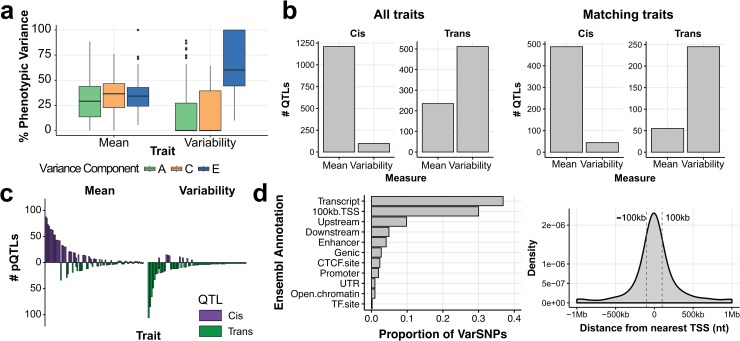

Fig 2. A relative depletion of cis genetic control of protein expression variability.

(a) Boxplots summarising the variance decomposition of all mean and expression variability traits into additive genetic (A), common environment (C) and unique environmental (E) components. (b) A summary of cis and trans QTL mapping for mean and variability traits demonstrates a depletion of cis variability-pQTLs using all traits tested (left) and the subset of matching traits (right). (c) Bar plots of the numbers of cis and trans QTLs across mean (left) and variability (right) traits illustrates the relative depletion of cis regulation of cell-to-cell expression variability. (d) varSNP annotations demonstrate (left) gene-centric association signals and (right) the proximity of varSNPs to the nearest protein-coding gene TSS.

Across the majority of variability traits, the unique environmental component is the prime influence, indicating that cell-to-cell expression variability is a consequence of the individual life histories of study participants, as well as experimental, stochastic and technical influences. In particular, the latter includes the non-specific binding of antibodies selected against the target proteins, reflecting a limitation of using indirect fluorescence measurements. Although the shared environment did not contribute to explaining variability in 53.8% of the traits considered, in the remainder its contribution was relatively substantial (median 40.3% of the trait variance). The shared environmental component includes in utero effects, as well as shared up-bringing, social and non-additive genetic effects and chronological age. In particular, age has previously been associated with changes in gene expression variability in a number of different cell types and organisms [34], including näive CD4+ T cells [35] (S3 Note, S8–S10 Figs).

For 59/171 (34.5%) of the variability traits the additive genetic component (σg2) was significantly greater than 0 (permutation test p-value≤0.05; S11 and S12 Figs). We observed that the genetic contributions to expression variability differ between cell types for the same protein (S13 Fig). The narrow-sense heritability estimates reveal that genetic factors have a broad range of influence on cell-to-cell gene expression variability (median 43%, range 0.019–89%). In comparison, 88.3% (151/171) of mean expression traits have a detectable heritable influence (Fig 2A), with a median contribution of 32% (range 0.01–88.6%). Overall, we have demonstrated that genetic variation contributes to inter-individual differences in protein expression variability in a cell-type specific manner.

Variability quantitative trait loci mapping

Given these results, we next sought to identify specific genetic loci that could explain the observed heritability. We scanned, separately in each cohort, for genetic variants that influence mean and expression variability in cis and in trans using a linear mixed model to account for the genetic relationships between individuals [36,37] (S14–S17 Figs). Collectively we tested 380 mean (MI: 229 traits, TwinsUK: 151 traits) and 288 variability traits (MI: 229 traits, TwinsUK: 59 traits) for both cis and trans effects across both cohorts. After grouping association signals for each trait based on linkage disequilibrium [38,39] (LD clumping), we noted that the number of significant cis effects was ~10-fold higher for mean traits than variability (Fig 2B). This was not driven by the larger number of mean traits tested (n = 380 vs. 288), as this difference in number of cis-pQTLs remained when we subset to the same trait for both mean and variability (Fig 2B). In comparison, we identified many more trans pQTLs for variability traits than we did for mean traits, which likewise was not due to differences in the number of mean and variability traits that we tested (Fig 2B), nor due to a small number of traits with many QTLs (Fig 2C). This imbalance in the genetic architectures of mean and expression variability suggests that between-individual differences in gene expression variability are primarily influenced by trans effects. Moreover, when looking at the small number of traits that were measured in both cohorts, the replication rate was greater than expected by chance (binomial test p-value = 6.5x10-5; S18 Fig), giving confidence in the robustness of our findings.

To interpret the variability-pQTLs that act in trans, we considered all loci across both cohorts and annotated the lead SNPs with the smallest p-value at each locus (henceforth called varSNPs) based on their overlap with regulatory and genome annotations using the Ensembl database. We observed that 36.9% of varSNPs mapped to transcribed regions, with a further 9.8% and 4.9% in upstream and downstream regions, respectively (Fig 2D). We also note a subtle enrichment of varSNPs located within 100kb of the nearest transcriptional start site (TSS) compared to MAF-matched control SNPs (OR 1.33, p-value 0.048; Fig 2D).

Cis genetic modulation of gene expression potentially drives protein expression variability-pQTLs

Our finding that most variability-pQTLs act in trans to the measured protein begs the question: what mechanism leads to these cell-to-cell expression level differences? Genetic control of average gene expression levels in cis has been the subject of extensive research, revealing widespread cis-regulation of gene expression levels [40–46]. Given this, and based on enrichment of varSNPs around genic regions, we hypothesised that cis genetic modulators of mean expression by variability-pQTLs may mediate cell-to-cell fluctuations in levels of the target proteins. To this end, we searched for variability-pQTLs that overlapped with cis-eQTLs in equivalent cell types [47–51] (S2 Table). Across matching cell types, we identified 260 cis-eQTLs that could be compared with 94 of our trans variability-pQTLs (18.4% of all trans variability-pQTLs).

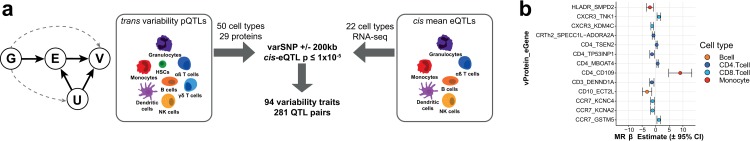

Where concordant SNPs were present in our study and each eQTL study, we used Mendelian Randomisation (MR) analysis between each protein-coding eGene and the protein expression variability trait to infer causality (Fig 3A). Specifically, we tested the hypothesis that the exposure (eGene expression level) is causally associated with the outcome (protein expression variability; vProtein), conditional on the genetic instrument (varSNP) (Fig 3A) using 281 pairs of varSNP and cis-eQTL eGenes. Adjusting for multiple testing (FDR 10%), we found that 62.8% (59/94) of tested trans variability QTLs could be explained by at least one mean cis-eQTL of a different gene (S19 Fig).

Fig 3. cis-eQTLs potentially drive protein expression variability of downstream genes.

(a) A schematic of Mendelian Randomisation as a directed acyclic graph (left) and cell type matching between variability pQTLs and mean cis-eQTLs (right). G denotes the genetic instrument used to mediate the potential causal relationship between gene expression (E) and protein expression variability (V). Unobserved confounding (U) and the presence of direct or indirect pleiotropy (grey dashed lines) can induce false positive associations. (b) Common genetic predictors between cis-eQTLs and variability-pQTLs in human immune cells (shown are those with an FDR < 5%). The x-axis denotes the MR regression estimate (β), error bars denote the 95% CI. Y-axis labels show the vProtein and eGene. Points are coloured by the cell type in which the eGene and variability QTL are both present.

These results provide candidate explanatory relationships between cis-eQTLs and our trans variability-pQTLs. For instance, rs971419521 is associated with increased CD3 variability in CD4+ regulatory T cells (β 1.00, SE 0.17, p = 8.35x10-9). We find a common genetic predictor between lower DENND1A expression in memory Tregs [47] and increased CD3 variability in Tregs (MR adjusted p-value 2.6x10-3, Fig 3B). DENND1A encodes DENN/MADD domain containing 1A, a guanosine exchange factor that regulates clathrin-mediated endocytosis [52]. CD3 subunits contain endocytosis signals for internalisation [53–56], which is key for T cell receptor turnover. We therefore speculate that fluctuations in endocytosis may lead to variable levels of CD3 on the surface of regulatory T cells, with the potential to influence regulatory T cell activation.

By integrating cis-eQTL information with variability-pQTLs we have highlighted how cis gene expression can potentially impact cell-to-cell protein expression variability in trans.

Discussion

Here we have provided insights into the control of cell-to-cell protein expression variability in the human immune system by means of a novel re-analysis of publicly available flow cytometry data. We have presented the first systematic analysis of the impact of genetic factors on cell-to-cell protein expression variability across human cohorts. Notably we have demonstrated that protein expression variability, often referred to as noise, is a heritable and polygenic trait in humans, as it is in yeast [31] and plants [32]. Curiously, the latter reported extensive trans variability eQTLs in Arabidopsis thaliana for > 20,000 transcripts, but observed that cis effects generally had larger effect sizes, more similar to the genetic architecture of mean mRNA levels [57,58]. This contrast with our findings might be explained by genetic regulation of cell type composition within A.thaliana as has been observed in humans [25,26], or may reflect the larger contribution of trans factors to protein levels compared to mRNA [59]. Secondly, our analyses illustrate how cell-to-cell expression variability, for the proteins studied, is primarily shaped by the actions of genetic variants that act in trans, suggesting that variability is primarily impacted by the cellular environment, a notion supported by the observation that genetic influences on protein networks are primarily mediated by non-transcriptional mechanisms [59]. Using quantitative genetics and Mendelian Randomisation, we were further able to infer that many of these trans-acting variants, which lie within 100kb of another gene, might function in cis. By so doing, they not only influence the expression of the proximal gene, but also impact the wider cellular microenvironment, thereby driving variability of downstream genes. Importantly, whilst we and others have observed a lack of cis-genetic effects on variability in humans [60], this does not imply that variability is not regulated in cis. Indeed, the study of experimentally induced sequence variation in transcriptional regulatory elements has revealed key mechanisms by which variability is controlled at the molecular level [11,14,15,18]. However, it is crucial to note that whilst common standing genetic variation in humans does not have a large influence on variability in cis, at least for the proteins included in this study, this is not the same as saying that there is no influence of cis-regulatory elements on variability. Instead, it supports a model whereby any cis-regulatory elements that do influence protein expression variability are not altered by common single nucleotide polymorphisms.

Moving forward, we anticipate that one way of increasing power to detect variability-pQTLs will be to obtain a better resolution of cell types both within and across studies. Single-cell RNA-sequencing provides a natural means for doing this, since it is able to profile all expressed genes, providing a more fine-grained ability to cluster cells into physiologically meaningful groups. Moreover, recently developed protocols allow mRNA and cell-surface proteins to be profiled in parallel [61], meaning that variability across multiple regulatory layers can be interrogated. Finally, our study was limited to the 47 proteins included in the original studies; extending these investigations proteome-wide and using larger cohorts will provide a more global picture of the impact of common genetic variants on gene expression variability. Using larger cohorts is especially important since, consistent with Sarkar et al. [60], our power to detect variability pQTLs is highly sensitive to sample size (S4 Note; S37 Fig).

From a broader perspective, our results have implications for our understanding of how natural selection can shape gene expression levels. The lack of genetic variants that act in cis to modulate gene expression variability is consistent with the action of purifying selection[14]. However, somewhat counterintuitively, we observe that cis-acting variants can have knock-on effects that manifest themselves in trans by increasing variability in expression of downstream genes. Why, if natural selection acts to remove variants that act in cis, is this increased variability tolerated? We speculate that there might exist a trade-off between regulating a gene’s expression directly and downstream impacts upon variability of other genes. This complex interplay might explain why variability-eQTL studies using single-cell RNA-sequencing data have struggled to identify regulatory variants associated with variability [60] since they have focused on studying this phenomenon in cis.

Methods

Flow cytometry data processing and immune cell gating

Flow cytometry data on TwinsUK participants were downloaded from FlowRepository.org (February 2018) in FCS 3.1 format. Flow cytometry data from the Milieu Intérieur cohort were provided directly by the Milieu Intérieur consortium. A total of 17455 FCS files were processed across both cohorts, with each file representing flow cytometry measurements for a single individual and a specific antibody panel (see S1 Table). The gating schema for each antibody panel (S20–S34 Figs) followed the original study designs for consistency. Prior to cell gating we removed samples with < 1000 recorded events in total. Non-scatter based fluorescence parameter measurements were transformed onto a common scale using a biexponential transform implemented in the R package flowCore [62]. To reduce the effects of confounding between technical factors and fluorescence measurements we performed normalization between individuals within an antibody panel (using a warping function estimated from the data) to align feature landmarks for each flow cytometer channel. Function parameter values were set for each target protein, including the number of principal landmarks (peakNr), number of spline sections to approximate the expression profile for each protein (nbreaks), and the bandwidth of the smooth density estimate (bwFac). Subsequently, for each cell type defined by the gating schema, we extracted the fluorescence values across all recorded parameters (protein and scatter-based). For each individual we removed measurements on each cell type where there were fewer than 100 cells. All flow cytometry processing used the flowCore, flowWorkspace, flowStats and ggcyto packages implemented in R [63].

Protein expression variability calculation

Single cell protein fluorescence measurements for each individual were log10 transformed and normalized to cell volume. Cell volume was calculated as the log10 of the cubed forward-scatter area. Protein expression variability was calculated across all single cells in each cell type for each individual using the squared coefficient of variation, i.e. variance divided by the squared mean, . The mean-adjusted measure of noise, denoted ηres, was calculated for each combination of protein, cell type and individual to yield a single trait value. Briefly, a local polynomial regression was used to estimate the mean-CV2 relationship across individuals for a given protein expressed in a specific cell type (see S1 Note). The residuals from this fit were standardized, that is they were rescaled to 0 mean and variance of 1, across individuals. Therefore, the final measure of protein expression variability, ηres, is expressed in terms of the number of relative standard deviations of the residual mean-adjusted CV2.

Genome-wide genotyping and processing

Imputed genome-wide genotyping on TwinsUK participants were provided by the TwinsUK Data Access Committee. Genotypes were imputed using IMPUTE2 [64] as previously described [25], using the 1000 Genomes phase 3 EUR reference panel [65]. Imputed genome-wide genotypes from the Milieu Intérieur cohort were obtained from the European Genome-Phenome archive, accession number EGAD00010001489, approved by the Data Access Committee (DAC). Imputed genotypes, generated by IMPUTE2 from the 1000 Genomes phase 1 EUR reference panel [66], were also downloaded. Binary genotype files in Plink format [38] were used as input for all analyses. Genetic relationship matrices (GRM) were calculated for each cohort of participants using autosomal SNPs. Genetic variants with a cohort minor allele frequency (MAF) < 1% and/or a Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium () p-value ≤1x10-50 were excluded from all analyses. For the linear mixed model-based genetic association testing, separate GRMs were pre-computed using genetic variants on each chromosome (Achromosome), as well as the complementary set of genetic variants, i.e. all genetic variants not on the chromosome in question. All GRMs were calculated using GCTA [67].

Variance components analysis and heritability estimation

Variance components analysis of each protein expression mean and variability trait was performed in the TwinsUK cohort. An expected genetic relationship matrix was calculated across all twins, with entries defined by twin zygosity, i.e. 1 for monozygotic twins, 0.5 for dizygotic twins and 0 for unrelated individuals. A second shared environment matrix contained a 1 for twin pairs and 0 for unrelated individuals. These matrices were included as random effects in a model to partition the trait variance into additive genetic (A), common environment (C; indistinguishable from non-additive genetic components) and unique environmental (E) components. Variance decomposition was performed in a structural equation modelling framework, implemented in the R package umx [68], which uses a Cholesky decomposition to estimate the model (variance) components as a fraction of the total variance. Variance component standard errors were estimated by a non-parametric bootstrapping procedure using a random sample of 75% of twin pairs. Permutation p-values were computed for each variance component by generating a null distribution of variance component estimates by randomly permuting the twin zygosity labels 100 times for each trait. P-values were then calculated as: .

Variability-quantitative trait loci genome-wide analysis

Variability-pQTLs were identified genome-wide for each protein expression variability trait using a linear mixed model. Each genetic variant was regressed on trait values measured across individuals, accounting for genetic relatedness between individuals (twins and “unrelated” individuals separately), as well as individual-level covariates. Specifically, a linear mixed model was fit for each trait:

Where yi is a vector of expression variability trait values (ηres) for trait i, α is the model intercept, g is a vector of SNP genotypes encoded as an additive model (0, 1, 2 copies of the minor allele), γ is the fixed effect maximum-likelihood coefficient estimate of the genetic variant on ηres, X is a matrix of fixed-effect covariates, β is a vector of maximum-likelihood coefficient estimates for the fixed-effect covariates, Z is a genetic covariance matrix calculated from autosomal genetic variants not on the chromosome encoding the protein of interest, u is the random-effects coefficient associated with this genetic covariance matrix, and ϵ is the residual trait variance. The matrix X contains in its columns age (years) and FCGR2A rs4657041 genotype (see S3 Note). We tested if there was sufficient evidence to reject the null hypothesis that the SNP effect γ = 0, using a t-test.

For cis-pQTL testing we extracted all genetic variants within a 1Mb window centered on the transcriptional start site of the gene encoding the target protein, and tested for a SNP-effect using LIMIX [37]. We adjusted for multiple testing first across genetic variants for each cis window using a beta-approximation to a permutation null distribution [69], then using a false-discovery control for the total number of traits tested [70]. Trans-pQTLs were tested for genome-wide using the same model described above implemented in GCTA [67].

Discrete genetic association signals and lead genetic variants (varSNPs) were assigned at each locus using an LD-based clumping procedure implemented in Plink v1.9. Index variants were selected with a test p-value ≤ 1x10-4 for trans associations and FDR ≤ 0.05 for cis. Additional variants were assigned to clumps within 250kb and r2>0.5 of each index variant.

Mendelian randomization analysis

Cis-eQTLs have the potential to drive the trans-variability QTLs we identify. For each variability-pQTL we extracted the cis-eQTL summary statistics in a 200kb window with a test p-value ≤ 1x10-5 for matching cell types (S3 Table). Where overlapping SNPs were present from both data sets we tested the hypothesis of a causal relationship (or shared genetic predictor) between the variability-pQTL and cis-eQTL signals. Mendelian Randomization (MR) uses the random assortment of alleles during meiosis as a conditioning factor to determine causal relationships from observational data [71,72]. To assign a meaningful causal relationship between a modifiable exposure (gene expression) and an outcome (eGene expression variability) requires 3 assumptions about the genetic variant (instrumental variable): 1) association between the genetic variant and exposure, 2) uncorrelated with any confounding effects between the exposure and outcome, and 3) conditionally independent of the outcome, given the exposure and confounders. Based on these assumptions, and a linear relationship for all associations, the unbiased causal effect of gene expression on expression variability can be estimated as the ratio of the linear model per-allele effect estimates:

This causal effect can be estimated directly from summary statistics in independent cohorts, known as 2-sample MR [73]. For each eGene and variability-pQTL pair we estimated the causal effect estimate (βcausal) using the MR maximum likelihood approach implemented in the R package MendelianRandomization [74]. In analyses where summary statistics were available for multiple SNPs for each trait we combined effect estimates across SNPs using MR-Egger regression [75], implemented in the R package MendelianRandomization. In the latter case, we also report Cochrane’s Q-statistic, a measure of genetic instrument heterogeneity as an indication of horizontal pleiotropy [76] (S36 Fig).

Sensitivity analysis

We determined the sensitivity of both cis and trans QTL mapping analyses to changes in sample size by down-sampling the number of individuals for a specific trait and repeating the analysis as described above. We randomly selected between 10 and 100% of unrelated individuals from the Milieu Intérieur cohort for two traits for which we had detected both cis and trans pQTLs: FcεR1A on basophils as a mean trait and HLA-DR on plasmacytoid DCs as a variability trait. Sensitivity was determined as the proportion of QTLs recovered compared to the full sample size. Results are presented in S37 Fig.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Listed are the lead VarSNP, MR analysis summary statistics (Beta, SE, P-value), eGene data set, MR heterogeneity statistics and variability-pQTL summary statistics, position and gene information.

(CSV)

Plotted are proportion of phenotypic variance of components for additive genetic (green), common environment (orange) and unique environment (blue). Each trait is listed on the y-axis for mean (left) and variability (right) traits.

(EPS)

Plotted are proportion of phenotypic variance of components for additive genetic (green), common environment (orange) and unique environment (blue). Each trait is listed on the y-axis for mean (left) and variability (right) traits.

(EPS)

Plotted are proportion of phenotypic variance of components for additive genetic (green), common environment (orange) and unique environment (blue). Each trait is listed on the y-axis for mean (left) and variability (right) traits.

(EPS)

Plotted are proportion of phenotypic variance of components for additive genetic (green), common environment (orange) and unique environment (blue). Each trait is listed on the y-axis for mean (left) and variability (right) traits.

(EPS)

Plotted are proportion of phenotypic variance of components for additive genetic (green), common environment (orange) and unique environment (blue). Each trait is listed on the y-axis for mean (left) and variability (right) traits.

(EPS)

Plotted are proportion of phenotypic variance of components for additive genetic (green), common environment (orange) and unique environment (blue). Each trait is listed on the y-axis for mean (left) and variability (right) traits.

(EPS)

Plotted are proportion of phenotypic variance of components for additive genetic (green), common environment (orange) and unique environment (blue). Each trait is listed on the y-axis for mean (left) and variability (right) traits.

(EPS)

(a) Scatter plot of effect sizes from a robust linear regression model of variability (x-axis) and mean (y-axis) with age (years). (b) Traits for which age increases variability (FDR 1%). (c) Traits for which variability decreases with age (FDR 1%). (d) Scatter plot of effect sizes of the influence of gender on expression variability (x-axis) and mean expression (y-axis). (e) Traits (x-axis) for which variability is increased in males relative to females. (f) Variability which are decreased in males relative to females. Purple points in (a) and (b) are associations only with variability, blue points are associations only with mean traits, and orange points are associations with both mean and variability. Points in (b, c, e, f) are regression model effect sizes with 95% confidence intervals.

(EPS)

Variability traits that increase (top) and decrease (bottom) with age (FDR 1%). Points are regression model coefficients; error bars are 95% confidence intervals.

(EPS)

Mean expression traits that decrease (a) and increase (b) with age. Mean expression traits that are lower (c) and higher (d) in males than females. Points are model regression coefficients; error bars are 95% confidence intervals.

(EPS)

Error bars represent bootstrapped standard errors from 100 permutations. Orange points are those with h2 +/- SE that fall within the interval [0, 1] (defined by the light grey box).

(EPS)

Distribution of empirical p-values of additive genetic variance components for expression variability traits.

(EPS)

Variance components estimates grouped by protein for mean (blue) and variability (orange) traits across cell types. Y-axis shows the % phenotypic variance, X-axis shows the variance components (A-additive genetic, C-common environment, E-unique environment).

(EPS)

Linear mixed model -log10 association p-values (y-axis) between expression variability and genome-wide genetic variants (x-axis). The purple horizontal line represents genome-wide significance threshold (5x10-8), and the orange line represents the Bonferroni corrected threshold (8.47x10-10).

(EPS)

Linear mixed model -log10 association p-values (y-axis) between expression variability and genome-wide genetic variants (x-axis). The purple horizontal line represents genome-wide significance threshold (5x10-8), and the orange line represents the Bonferroni corrected threshold (8.47x10-10).

(EPS)

Linear mixed model -log10 association p-values (y-axis) between expression variability and genome-wide genetic variants (x-axis). The purple horizontal line represents genome-wide significance threshold (5x10-8), and the orange line represents the Bonferroni corrected threshold (8.47x10-10).

(EPS)

Linear mixed model -log10 association p-values (y-axis) between mean expression levels and genome-wide genetic variants (x-axis). The purple horizontal line represents genome-wide significance threshold (5x10-8), and the orange line represents the Bonferroni corrected threshold (8.47x10-10).

(EPS)

Venn diagrams showing the overlap of mean (a) and expression variability traits (b) between the Milieu Intérieur (red) and TwinsUK (blue).

(EPS)

Shown are the MR regression estimate (β), error bars denote the 95% CI for relationships at FDR 10%. Y-axis labels show the vProtein and eGene. Points are coloured by the cell type in which the eGene and variability QTL are both present.

(EPS)

(EPS)

(EPS)

(EPS)

(EPS)

(EPS)

(EPS)

(EPS)

(EPS)

(EPS)

(EPS)

(EPS)

(EPS)

(EPS)

(EPS)

(EPS)

Linear mixed model -log10 association p-values (y-axis) between CD3 expression variability in granulocytes and genome-wide genetic variants (x-axis) without (top) and with (bottom) adjustment for FCGR2A genotype at rs4657041. The purple horizontal line represents genome-wide significance threshold (5x10-8), and the orange line represents the Bonferroni corrected threshold (8.47x10-10).

(EPS)

Shown are the Cochrane’s Q-values from the MR-Egger regression across SNPs (x-axis) for each pair of varSNP and eGene (y-axis). Points are coloured by the broad matching cell type between the trans variability-pQTL and cis-eQTL. Point size is proportional to the -log10 p-value from a χ2 test.

(EPS)

Shown are the proportion of QTLs detected (y-axis) as a function of the sample size (x-axis) for both mean (salmon) and variability (turquoise) traits. (a) Cis-QTL mapping and (b) trans-QTL mapping were performed separately. Numbers denote the total number of QTLs detected with the largest sample size.

(EPS)

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr Arianne Richard and Dr Luis Barreiro for their critical reading of the manuscript. The authors also wish to extend their gratitude to TwinsUK for sharing data. TwinsUK is funded by the Wellcome Trust, Medical Research Council, European Union, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)-funded BioResource, Clinical Research Facility and Biomedical Research Centre based at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust in partnership with King’s College London.

Data Availability

Genotype data from the Milieu Intérieur cohort are available via managed access in the European Genome-Phenome Archive (EGAD00010001489). TwinsUK genotype data are available by approval via the TwinsUK data access committee (https://twinsuk.ac.uk/). All summary statistics are publicly available via:https://content.cruk.cam.ac.uk/jmlab/VariabilityGenetics/. Processing and analysis code are publicly available via https://github.com/MarioniLab/VariabilityGenetics2019.

Funding Statement

MDM was supported by the Wellcome Trust (grant 105045/Z/14/Z). JCM was supported by core funding from the European Molecular Biology Laboratory and from Cancer Research UK (award number 17197). LQM is supported by the French Government’s Investissement d’Avenir Program, Laboratoire d’Excellence “Milieu Intérieur” (Grant ANR-10-LABX-69-01) and the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (Equipe FRM DEQ20180339214). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Ozbudak EM, Thattai M, Kurtser I, Grossman AD, van Oudenaarden A. Regulation of noise in the expression of a single gene. Nat Genet. 2002;31: 69–73. 10.1038/ng869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swain PS, Elowitz MB, Siggia ED. Intrinsic and extrinsic contributions to stochasticity in gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2002;99: 12795–12800. 10.1073/pnas.162041399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zopf CJ, Quinn K, Zeidman J, Maheshri N. Cell-Cycle Dependence of Transcription Dominates Noise in Gene Expression. Kondev J, editor. PLoS Comput Biol. 2013;9: e1003161 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kiviet DJ, Nghe P, Walker N, Boulineau S, Sunderlikova V, Tans SJ. Stochasticity of metabolism and growth at the single-cell level. Nature. 2014;514: 376–379. 10.1038/nature13582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fang M, Xie H, Dougan SK, Ploegh H, van Oudenaarden A. Stochastic Cytokine Expression Induces Mixed T Helper Cell States. Bhandoola A, editor. PLoS Biol. 2013;11: e1001618 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elowitz MB. Stochastic Gene Expression in a Single Cell. Science. 2002;297: 1183–1186. 10.1126/science.1070919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanchez A, Golding I. Genetic Determinants and Cellular Constraints in Noisy Gene Expression. Science. 2013;342: 1188–1193. 10.1126/science.1242975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eling N, Morgan MD, Marioni JC. Challenges in measuring and understanding biological noise. Nat Rev Genet. 2019. [cited 22 May 2019]. 10.1038/s41576-019-0130-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Charlebois DA, Abdennur N, Kaern M. Gene Expression Noise Facilitates Adaptation and Drug Resistance Independently of Mutation. Phys Rev Lett. 2011;107 10.1103/PhysRevLett.107.218101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shaffer SM, Dunagin MC, Torborg SR, Torre EA, Emert B, Krepler C, et al. Rare cell variability and drug-induced reprogramming as a mode of cancer drug resistance. Nature. 2017;546: 431–435. 10.1038/nature22794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duveau F, Hodgins-Davis A, Metzger BP, Yang B, Tryban S, Walker EA, et al. Fitness effects of altering gene expression noise in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. eLife. 2018;7 10.7554/eLife.37272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schultz D, Wolynes PG, Jacob EB, Onuchic JN. Deciding fate in adverse times: Sporulation and competence in Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2009;106: 21027–21034. 10.1073/pnas.0912185106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Antebi YE, Reich-Zeliger S, Hart Y, Mayo A, Eizenberg I, Rimer J, et al. Mapping Differentiation under Mixed Culture Conditions Reveals a Tunable Continuum of T Cell Fates. Bhandoola A, editor. PLoS Biol. 2013;11: e1001616 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Metzger BPH, Yuan DC, Gruber JD, Duveau F, Wittkopp PJ. Selection on noise constrains variation in a eukaryotic promoter. Nature. 2015;521: 344 10.1038/nature14244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharon E, van Dijk D, Kalma Y, Keren L, Manor O, Yakhini Z, et al. Probing the effect of promoters on noise in gene expression using thousands of designed sequences. Genome Res. 2014;24: 1698–1706. 10.1101/gr.168773.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morgan MD, Marioni JC. CpG island composition differences are a source of gene expression noise indicative of promoter responsiveness. Genome Biol. 2018;19 10.1186/s13059-018-1461-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Faure AJ, Schmiedel JM, Lehner B. Systematic Analysis of the Determinants of Gene Expression Noise in Embryonic Stem Cells. Cell Syst. 2017. [cited 9 Nov 2017]. 10.1016/j.cels.2017.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hornung G, Bar-Ziv R, Rosin D, Tokuriki N, Tawfik DS, Oren M, et al. Noise-mean relationship in mutated promoters. Genome Res. 2012;22: 2409–2417. 10.1101/gr.139378.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larsson AJM, Johnsson P, Hagemann-Jensen M, Hartmanis L, Faridani OR, Reinius B, et al. Genomic encoding of transcriptional burst kinetics. Nature. 2019;565: 251–254. 10.1038/s41586-018-0836-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bartman CR, Hamagami N, Keller CA, Giardine B, Hardison RC, Blobel GA, et al. Transcriptional Burst Initiation and Polymerase Pause Release Are Key Control Points of Transcriptional Regulation. Mol Cell. 2019;73: 519–532.e4. 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Battich N, Stoeger T, Pelkmans L. Control of Transcript Variability in Single Mammalian Cells. Cell. 2015;163: 1596–1610. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Torre EA, Arai E, Bayatpour S, Beck LE, Emert BL, Shaffer SM, et al. Genetic screening for single-cell variability modulators driving therapy resistance. bioRxiv. 2019. [cited 22 May 2019]. 10.1101/638809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boyle EA, Li YI, Pritchard JK. An Expanded View of Complex Traits: From Polygenic to Omnigenic. Cell. 2017;169: 1177–1186. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Visscher PM, Wray NR, Zhang Q, Sklar P, McCarthy MI, Brown MA, et al. 10 Years of GWAS Discovery: Biology, Function, and Translation. Am J Hum Genet. 2017;101: 5–22. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roederer M, Quaye L, Mangino M, Beddall MH, Mahnke Y, Chattopadhyay P, et al. The Genetic Architecture of the Human Immune System: A Bioresource for Autoimmunity and Disease Pathogenesis. Cell. 2015;161: 387–403. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patin E, Bergstedt J, Rouilly V, Libri V, Urrutia A, Alanio C, et al. Natural variation in the parameters of innate immune cells is preferentially driven by genetic factors. Nat Immunol. 2018;19: 302–314. 10.1038/s41590-018-0049-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bar-Even A, Paulsson J, Maheshri N, Carmi M, O’Shea E, Pilpel Y, et al. Noise in protein expression scales with natural protein abundance. Nat Genet. 2006;38: 636–643. 10.1038/ng1807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kempe H, Schwabe A, Crémazy F, Verschure PJ, Bruggeman FJ. The volumes and transcript counts of single cells reveal concentration homeostasis and capture biological noise. Matera AG, editor. Mol Biol Cell. 2015;26: 797–804. 10.1091/mbc.E14-08-1296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tanouchi Y, Pai A, Park H, Huang S, Stamatov R, Buchler NE, et al. A noisy linear map underlies oscillations in cell size and gene expression in bacteria. Nature. 2015;523: 357–360. 10.1038/nature14562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wills QF, Livak KJ, Tipping AJ, Enver T, Goldson AJ, Sexton DW, et al. Single-cell gene expression analysis reveals genetic associations masked in whole-tissue experiments. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31: 748–752. 10.1038/nbt.2642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ansel J, Bottin H, Rodriguez-Beltran C, Damon C, Nagarajan M, Fehrmann S, et al. Cell-to-Cell Stochastic Variation in Gene Expression Is a Complex Genetic Trait. PLOS Genet. 2008;4: e1000049 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jimenez-Gomez JM, Corwin JA, Joseph B, Maloof JN, Kliebenstein DJ. Genomic Analysis of QTLs and Genes Altering Natural Variation in Stochastic Noise. Gibson G, editor. PLoS Genet. 2011;7: e1002295 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu Y, Biancotto A, Cheung F, Remmers E, Shah N, McCoy JP, et al. Systematic Analysis of Cell-to-Cell Expression Variation of T Lymphocytes in a Human Cohort Identifies Aging and Genetic Associations. Immunity. 2016;45: 1162–1175. 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.10.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bahar R, Hartmann CH, Rodriguez KA, Denny AD, Busuttil RA, Dollé MET, et al. Increased cell-to-cell variation in gene expression in ageing mouse heart. Nature. 2006;441: 1011–1014. 10.1038/nature04844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martinez-Jimenez CP, Eling N, Chen H-C, Vallejos CA, Kolodziejczyk AA, Connor F, et al. Aging increases cell-to-cell transcriptional variability upon immune stimulation. Science. 2017;355: 1433–1436. 10.1126/science.aah4115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kang HM, Sul JH, Service SK, Zaitlen NA, Kong S, Freimer NB, et al. Variance component model to account for sample structure in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2010;42: 348–354. 10.1038/ng.548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Casale FP, Rakitsch B, Lippert C, Stegle O. Efficient set tests for the genetic analysis of correlated traits. Nat Methods. 2015;12: 755–758. 10.1038/nmeth.3439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chang CC, Chow CC, Tellier LC, Vattikuti S, Purcell SM, Lee JJ. Second-generation PLINK: rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. GigaScience. 2015;4 10.1186/s13742-015-0047-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MAR, Bender D, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81: 559–575. 10.1086/519795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.The Multiple Tissue Human Expression Resource (MuTHER) Consortium, Grundberg E, Small KS, Hedman ÅK, Nica AC, Buil A, et al. Mapping cis- and trans-regulatory effects across multiple tissues in twins. Nat Genet. 2012;44: 1084–1089. 10.1038/ng.2394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Consortium GTEx. Genetic effects on gene expression across human tissues. Nature. 2017;550: 204–213. 10.1038/nature24277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Deutsch S, Lyle R, Dermitzakis ET, Attar H, Subrahmanyan L, Gehrig C, et al. Gene expression variation and expression quantitative trait mapping of human chromosome 21 genes. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14: 3741–3749. 10.1093/hmg/ddi404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stranger BE, Forrest MS, Clark AG, Minichiello MJ, Deutsch S, Lyle R, et al. Genome-wide associations of gene expression variation in humans. PLoS Genet. 2005;1: e78 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stranger BE, Nica AC, Forrest MS, Dimas A, Bird CP, Beazley C, et al. Population genomics of human gene expression. Nat Genet. 2007;39: 1217–1224. 10.1038/ng2142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dimas AS, Deutsch S, Stranger BE, Montgomery SB, Borel C, Attar-Cohen H, et al. Common regulatory variation impacts gene expression in a cell type-dependent manner. Science. 2009;325: 1246–1250. 10.1126/science.1174148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhernakova DV, Deelen P, Vermaat M, van Iterson M, van Galen M, Arindrarto W, et al. Identification of context-dependent expression quantitative trait loci in whole blood. Nat Genet. 2017;49: 139–145. 10.1038/ng.3737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schmiedel BJ, Singh D, Madrigal A, Valdovino-Gonzalez AG, White BM, Zapardiel-Gonzalo J, et al. Impact of Genetic Polymorphisms on Human Immune Cell Gene Expression. Cell. 2018;175: 1701–1715.e16. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.10.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kasela S, Kisand K, Tserel L, Kaleviste E, Remm A, Fischer K, et al. Pathogenic implications for autoimmune mechanisms derived by comparative eQTL analysis of CD4+ versus CD8+ T cells. Lappalainen T, editor. PLOS Genet. 2017;13: e1006643 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ishigaki K, Kochi Y, Suzuki A, Tsuchida Y, Tsuchiya H, Sumitomo S, et al. Polygenic burdens on cell-specific pathways underlie the risk of rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Genet. 2017;49: 1120–1125. 10.1038/ng.3885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen L, Ge B, Casale FP, Vasquez L, Kwan T, Garrido-Martín D, et al. Genetic Drivers of Epigenetic and Transcriptional Variation in Human Immune Cells. Cell. 2016;167: 1398–1414.e24. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fairfax BP, Makino S, Radhakrishnan J, Plant K, Leslie S, Dilthey A, et al. Genetics of gene expression in primary immune cells identifies cell type–specific master regulators and roles of HLA alleles. Nat Genet. 2012;44: 502 10.1038/ng.2205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Allaire PD, Marat AL, Dall’Armi C, Di Paolo G, McPherson PS, Ritter B. The Connecdenn DENN Domain: A GEF for Rab35 Mediating Cargo-Specific Exit from Early Endosomes. Mol Cell. 2010;37: 370–382. 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.12.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dietrich J, Hou X, Wegener A-MK, Pedersen LØ, Ødum N, Geisler C. Molecular Characterization of the Di-leucine-based Internalization Motif of the T Cell Receptor. J Biol Chem. 1996;271: 11441–11448. 10.1074/jbc.271.19.11441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dietrich J, Hou X, Wegener AM, Geisler C. CD3 gamma contains a phosphoserine-dependent di-leucine motif involved in down-regulation of the T cell receptor. EMBO J. 1994;13: 2156–2166. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06492.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Luton F, Buferne M, Legendre V, Chauvet E, Boyer C, Schmitt-Verhulst AM. Role of CD3gamma and CD3delta cytoplasmic domains in cytolytic T lymphocyte functions and TCR/CD3 down-modulation. J Immunol Baltim Md 1950. 1997;158: 4162–4170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Borroto A, Lama J, Niedergang F, Dautry-Varsat A, Alarcón B, Alcover A. The CD3 epsilon subunit of the TCR contains endocytosis signals. J Immunol Baltim Md 1950. 1999;163: 25–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Petretto E, Mangion J, Dickens NJ, Cook SA, Kumaran MK, Lu H, et al. Heritability and Tissue Specificity of Expression Quantitative Trait Loci. PLoS Genet. 2006;2: e172 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gibson G, Weir B. The quantitative genetics of transcription. Trends Genet. 2005;21: 616–623. 10.1016/j.tig.2005.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Foss EJ, Radulovic D, Shaffer SA, Goodlett DR, Kruglyak L, Bedalov A. Genetic Variation Shapes Protein Networks Mainly through Non-transcriptional Mechanisms. Eisen MB, editor. PLoS Biol. 2011;9: e1001144 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sarkar AK, Tung P-Y, Blischak JD, Burnett JE, Li YI, Stephens M, et al. Discovery and characterization of variance QTLs in human induced pluripotent stem cells. Cotsapas C, editor. PLOS Genet. 2019;15: e1008045 10.1371/journal.pgen.1008045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stoeckius M, Hafemeister C, Stephenson W, Houck-Loomis B, Chattopadhyay PK, Swerdlow H, et al. Simultaneous epitope and transcriptome measurement in single cells. Nat Methods. 2017;14: 865–868. 10.1038/nmeth.4380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hahne F, LeMeur N, Brinkman RR, Ellis B, Haaland P, Sarkar D, et al. flowCore: a Bioconductor package for high throughput flow cytometry. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10 10.1186/1471-2105-10-106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2017. Available: https://www.R-project.org [Google Scholar]

- 64.Howie BN, Donnelly P, Marchini J. A Flexible and Accurate Genotype Imputation Method for the Next Generation of Genome-Wide Association Studies. Schork NJ, editor. PLoS Genet. 2009;5: e1000529 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.The 1000 Genomes Project Consortium. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature. 2015;526: 68–74. 10.1038/nature15393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.The 1000 Genomes Project Consortium. A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature. 2010;467: 1061–1073. 10.1038/nature09534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yang J, Lee SH, Goddard ME, Visscher PM. GCTA: A Tool for Genome-wide Complex Trait Analysis. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88: 76–82. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.11.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bates TC, Maes H, Neale MC. umx: Twin and Path-Based Structural Equation Modeling in R. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2019;22: 27–41. 10.1017/thg.2019.2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ongen H, Buil A, Brown AA, Dermitzakis ET, Delaneau O. Fast and efficient QTL mapper for thousands of molecular phenotypes. Bioinforma Oxf Engl. 2016;32: 1479–1485. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Storey JD, Tibshirani R. Statistical significance for genomewide studies. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2003;100: 9440–9445. 10.1073/pnas.1530509100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lawlor DA, Harbord RM, Sterne JAC, Timpson N, Davey Smith G. Mendelian randomization: Using genes as instruments for making causal inferences in epidemiology. Stat Med. 2008;27: 1133–1163. 10.1002/sim.3034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Didelez V, Sheehan N. Mendelian randomization as an instrumental variable approach to causal inference. Stat Methods Med Res. 2007;16: 309–330. 10.1177/0962280206077743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pierce BL, Burgess S. Efficient Design for Mendelian Randomization Studies: Subsample and 2-Sample Instrumental Variable Estimators. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178: 1177–1184. 10.1093/aje/kwt084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yavorska OO, Burgess S. MendelianRandomization: an R package for performing Mendelian randomization analyses using summarized data. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46: 1734–1739. 10.1093/ije/dyx034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bowden J, Davey Smith G, Burgess S. Mendelian randomization with invalid instruments: effect estimation and bias detection through Egger regression. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44: 512–525. 10.1093/ije/dyv080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bowden J, Hemani G, Davey Smith G. Invited Commentary: Detecting Individual and Global Horizontal Pleiotropy in Mendelian Randomization—A Job for the Humble Heterogeneity Statistic? Am J Epidemiol. 2018. [cited 29 Jul 2019]. 10.1093/aje/kwy185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Listed are the lead VarSNP, MR analysis summary statistics (Beta, SE, P-value), eGene data set, MR heterogeneity statistics and variability-pQTL summary statistics, position and gene information.

(CSV)

Plotted are proportion of phenotypic variance of components for additive genetic (green), common environment (orange) and unique environment (blue). Each trait is listed on the y-axis for mean (left) and variability (right) traits.

(EPS)

Plotted are proportion of phenotypic variance of components for additive genetic (green), common environment (orange) and unique environment (blue). Each trait is listed on the y-axis for mean (left) and variability (right) traits.

(EPS)

Plotted are proportion of phenotypic variance of components for additive genetic (green), common environment (orange) and unique environment (blue). Each trait is listed on the y-axis for mean (left) and variability (right) traits.

(EPS)

Plotted are proportion of phenotypic variance of components for additive genetic (green), common environment (orange) and unique environment (blue). Each trait is listed on the y-axis for mean (left) and variability (right) traits.

(EPS)

Plotted are proportion of phenotypic variance of components for additive genetic (green), common environment (orange) and unique environment (blue). Each trait is listed on the y-axis for mean (left) and variability (right) traits.

(EPS)

Plotted are proportion of phenotypic variance of components for additive genetic (green), common environment (orange) and unique environment (blue). Each trait is listed on the y-axis for mean (left) and variability (right) traits.

(EPS)

Plotted are proportion of phenotypic variance of components for additive genetic (green), common environment (orange) and unique environment (blue). Each trait is listed on the y-axis for mean (left) and variability (right) traits.

(EPS)

(a) Scatter plot of effect sizes from a robust linear regression model of variability (x-axis) and mean (y-axis) with age (years). (b) Traits for which age increases variability (FDR 1%). (c) Traits for which variability decreases with age (FDR 1%). (d) Scatter plot of effect sizes of the influence of gender on expression variability (x-axis) and mean expression (y-axis). (e) Traits (x-axis) for which variability is increased in males relative to females. (f) Variability which are decreased in males relative to females. Purple points in (a) and (b) are associations only with variability, blue points are associations only with mean traits, and orange points are associations with both mean and variability. Points in (b, c, e, f) are regression model effect sizes with 95% confidence intervals.

(EPS)

Variability traits that increase (top) and decrease (bottom) with age (FDR 1%). Points are regression model coefficients; error bars are 95% confidence intervals.

(EPS)

Mean expression traits that decrease (a) and increase (b) with age. Mean expression traits that are lower (c) and higher (d) in males than females. Points are model regression coefficients; error bars are 95% confidence intervals.

(EPS)

Error bars represent bootstrapped standard errors from 100 permutations. Orange points are those with h2 +/- SE that fall within the interval [0, 1] (defined by the light grey box).

(EPS)

Distribution of empirical p-values of additive genetic variance components for expression variability traits.

(EPS)

Variance components estimates grouped by protein for mean (blue) and variability (orange) traits across cell types. Y-axis shows the % phenotypic variance, X-axis shows the variance components (A-additive genetic, C-common environment, E-unique environment).

(EPS)

Linear mixed model -log10 association p-values (y-axis) between expression variability and genome-wide genetic variants (x-axis). The purple horizontal line represents genome-wide significance threshold (5x10-8), and the orange line represents the Bonferroni corrected threshold (8.47x10-10).

(EPS)

Linear mixed model -log10 association p-values (y-axis) between expression variability and genome-wide genetic variants (x-axis). The purple horizontal line represents genome-wide significance threshold (5x10-8), and the orange line represents the Bonferroni corrected threshold (8.47x10-10).

(EPS)

Linear mixed model -log10 association p-values (y-axis) between expression variability and genome-wide genetic variants (x-axis). The purple horizontal line represents genome-wide significance threshold (5x10-8), and the orange line represents the Bonferroni corrected threshold (8.47x10-10).

(EPS)

Linear mixed model -log10 association p-values (y-axis) between mean expression levels and genome-wide genetic variants (x-axis). The purple horizontal line represents genome-wide significance threshold (5x10-8), and the orange line represents the Bonferroni corrected threshold (8.47x10-10).

(EPS)

Venn diagrams showing the overlap of mean (a) and expression variability traits (b) between the Milieu Intérieur (red) and TwinsUK (blue).

(EPS)

Shown are the MR regression estimate (β), error bars denote the 95% CI for relationships at FDR 10%. Y-axis labels show the vProtein and eGene. Points are coloured by the cell type in which the eGene and variability QTL are both present.

(EPS)

(EPS)

(EPS)

(EPS)

(EPS)

(EPS)

(EPS)

(EPS)

(EPS)

(EPS)

(EPS)

(EPS)

(EPS)

(EPS)

(EPS)

(EPS)

Linear mixed model -log10 association p-values (y-axis) between CD3 expression variability in granulocytes and genome-wide genetic variants (x-axis) without (top) and with (bottom) adjustment for FCGR2A genotype at rs4657041. The purple horizontal line represents genome-wide significance threshold (5x10-8), and the orange line represents the Bonferroni corrected threshold (8.47x10-10).

(EPS)

Shown are the Cochrane’s Q-values from the MR-Egger regression across SNPs (x-axis) for each pair of varSNP and eGene (y-axis). Points are coloured by the broad matching cell type between the trans variability-pQTL and cis-eQTL. Point size is proportional to the -log10 p-value from a χ2 test.

(EPS)

Shown are the proportion of QTLs detected (y-axis) as a function of the sample size (x-axis) for both mean (salmon) and variability (turquoise) traits. (a) Cis-QTL mapping and (b) trans-QTL mapping were performed separately. Numbers denote the total number of QTLs detected with the largest sample size.

(EPS)

Data Availability Statement

Genotype data from the Milieu Intérieur cohort are available via managed access in the European Genome-Phenome Archive (EGAD00010001489). TwinsUK genotype data are available by approval via the TwinsUK data access committee (https://twinsuk.ac.uk/). All summary statistics are publicly available via:https://content.cruk.cam.ac.uk/jmlab/VariabilityGenetics/. Processing and analysis code are publicly available via https://github.com/MarioniLab/VariabilityGenetics2019.