Abstract

The widespread use of combination antiretroviral therapies (cART) has converted the prognosis of HIV infection from a rapidly progressive and ultimately fatal disease to a chronic condition with limited impact on life expectancy. Yet, HIV-infected patients remain at high risk for critical illness due to the occurrence of severe opportunistic infections in those with advanced immunosuppression (i.e., inaugural admissions or limited access to cART), a pronounced susceptibility to bacterial sepsis and tuberculosis at every stage of HIV infection, and a rising prevalence of underlying comorbidities such as chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases, atherosclerosis or non-AIDS-defining neoplasms in cART-treated patients aging with controlled viral replication. Several patterns of intensive care have markedly evolved in this patient population over the late cART era, including a steady decline in AIDS-related admissions, an opposite trend in admissions for exacerbated comorbidities, the emergence of additional drivers of immunosuppression (e.g., anti-neoplastic chemotherapy or solid organ transplantation), the management of cART in the acute phase of critical illness, and a dramatic progress in short-term survival that mainly results from general advances in intensive care practices. Besides, there is a lack of data regarding other features of ICU and post-ICU care in these patients, especially on the impact of sociological factors on clinical presentation and prognosis, the optimal timing of cART introduction in AIDS-related admissions, determinants of end-of-life decisions, long-term survival, and functional outcomes. In this narrative review, we sought to depict the current evidence regarding the management of HIV-infected patients admitted to the intensive care unit.

Keywords: Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia, Bacterial sepsis, Antiretroviral therapy, Mechanical ventilation, Outcome, Intensive care unit

Take-home messages

| In the late cART era, most of HIV-infected patients requiring ICU admission present with bacterial sepsis or exacerbated chronic diseases though severe AIDS-related opportunistic infections continue to occur in those with previously unknown seropositivity or limited access to antiretroviral drugs. Short-term survival has dramatically improved over the past decades owing to general advances in ICU practices. |

Introduction

The pandemic of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection remains a pivotal public health challenge more than 20 years after the advent of combination antiretroviral therapies (cART), with 1.8 million new infections and almost 800,000 acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)-related deaths occurring annually [1]. An estimated 37.8 million people are currently living with HIV worldwide, corresponding to a ~ 50% increase since the early 2000s that ensues from both continuous transmission of the disease and a dramatic improvement of life expectancy in patients with access to cART, the latter now accounting for roughly two-thirds of the global seropositive population [1].

HIV-infected patients are at high risk for critical illness due to the occurrence of severe opportunistic infections (OI) in those with advanced immunosuppression, a pronounced susceptibility to bacterial sepsis and tuberculosis at every stage of HIV infection, and a rising prevalence of comorbid conditions in cART-treated patients aging with controlled viral replication [2, 3]. Hence, caring for a patient with HIV infection still represents a common situation for intensivists even though the recruitment of each intensive care unit (ICU) varies substantially depending on local prevalence, sociological parameters, and admission volumes.

Several patterns of intensive care have markedly evolved in this patient population over the late cART era, including a steady decline in AIDS-related admissions, an opposite trend in admissions for exacerbated comorbidities, the emergence of new mechanisms of immunosuppression not directly resulting from AIDS [e.g., anti-neoplastic chemotherapy or solid organ transplantation (SOT)], the management of cART at the acute phase of critical illness, and a considerable enhancement in short-term survival that mainly results from general advances in ICU practices.

This narrative review aims at summarizing the available literature regarding the epidemiology, specific management and short-term outcomes of HIV-infected patients admitted to the ICU. Knowledge gaps and potential axes for future research are also discussed.

The current landscape of HIV infection in the ICU

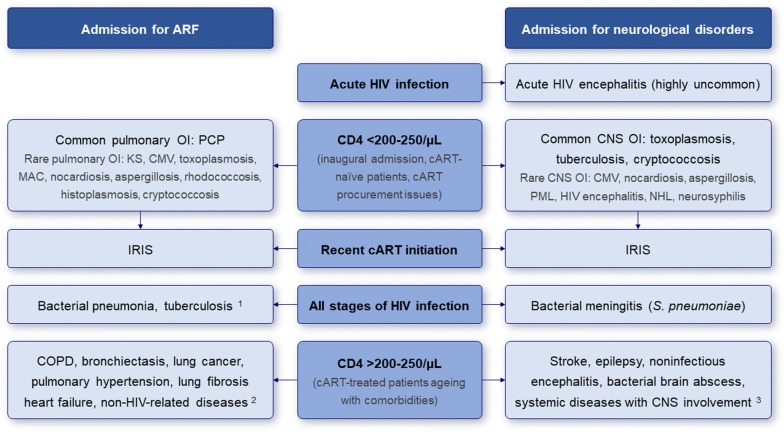

Late-stage HIV infection remains a common reason for ICU admission in settings or sociological clusters with limited access to diagnosis, cART, and specialized aftercare—migrants, homeless people, and other individuals without adequate health insurance coverage are particularly affected in high-income countries. These patients primarily present with severe AIDS-related OIs on a background of poor nutritional status and advanced immunosuppression, similar to the early years of the HIV pandemic (1980–1995). Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (PCP), cerebral toxoplasmosis and tuberculosis are the leading diagnoses, especially for inaugural admissions (Fig. 1) [2, 3]. Such patients account for 10–30% of all ICU admissions of HIV-infected individuals, though this proportion appears dwindling over the past decade [4–9]. Of note, severely immunosuppressed hosts—that is, those with CD4+ T lymphocyte (hereafter referred to as CD4 cells) counts < 100/µL—may not have a single pathological process to account for ICU presentation and intensivists should consider the possibility of two or more co-existing OIs.

Fig. 1.

Etiological spectrum of critical illnesses in HIV-infected patients. ARF acute respiratory failure, OI opportunistic infection, PCP Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia, KS Kaposi sarcoma, MAC Mycobacterium avium complex, cART combination antiretroviral therapy, CNS central nervous system, PML progressive multifocal encephalopathy (JC virus encephalitis), NHL non-Hodgkin lymphoma, IRIS immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases. (1) Pulmonary tuberculosis is also a major cause of IRIS that may lead to ARF; (2) interstitial pneumonitis, drug toxicity, asthma, pulmonary embolism, others; (3) sepsis, endocarditis, anoxia, metabolic disorders, drug toxicity or overdose, malignancies, thrombotic microangiopathy, others

Severe AIDS-defining conditions may also occur in patients with uncontrolled viral replication despite cART. However, the contemporary therapeutic armamentarium enables achieving viral suppression and immunological restoration within 6 months in more than 90% of cases—even those involving resistant strains—with maintenance of OI prophylaxis [e.g., sulfamethoxazole plus trimethoprim (SXT) for PCP] until a protective CD4 cell threshold is achieved [10, 11]. Beside compliance flaws, virological failure in 2020 is mainly linked with procurement issues (i.e., stock-outs, defective supply, or lack of financial resources) in low- and middle-income countries as in other environments with restricted access to cART.

cART-treated patients aging with sustained viral control are at increased risk for a broad spectrum of chronic diseases that predispose to life-threatening complications [4], including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), atherosclerosis (e.g., coronary heart disease or cerebrovascular disease), non-AIDS-defining cancers (especially lung, liver and anal carcinoma), and renal or liver impairment [12–18]. Lifetime low-level inflammation due to silent HIV replication in sanctuary sites, co-infections (e.g., CMV, EBV or HBV/HCV), intestinal dysbiosis, habitus (e.g., tobacco or intravenous drug use), sequelae of past infectious processes and long-term toxicity of certain antiretroviral medications may be implicated to varying degrees in the pathogenesis of these conditions [10, 19, 20]. Up to 70% of HIV-infected patients nowadays managed in the ICU are receiving long-term cART [6, 8, 9, 21–24]. This epidemiological shift translates into a continuous rise in non-AIDS-related ICU admissions which broadly exceeded those for severe OIs in most of recent cohorts. Furthermore, on the basis of encouraging outcomes, HIV infection is no longer a definite contra-indication for SOT in patients with chronic kidney, liver or heart failure, thereby enlarging the scope of critical illnesses in this population [25–27].

At last, acute HIV infection usually presents as a benign mononucleosis-like condition; yet, severe presentations including encephalitis, myocarditis, or multiple organ failure due to hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) have been occasionally reported and may require ICU admission [28–31].

Similarities between critically ill HIV-infected and seronegative patients

As a result of easier access to cART and sequential improvements in intensive care practices, critically ill HIV-infected individuals now share several similarities with the general population of ICU patients. First, the reasons for ICU admission are evenly distributed between seropositive and HIV-uninfected patients, with acute respiratory failure (ARF, 40–60% of all admissions), bacterial sepsis (10–20%, mostly resulting from respiratory, intra-abdominal and bloodstream infections) and impaired consciousness (10–20%) being the main clinical vignettes in both subgroups [5, 22, 24, 32]. Admissions for acute kidney injury (AKI), gastro-intestinal bleeding, acute or chronic liver failure, or scheduled post-operative management become more regular over time, which merely reflects the increasing prevalence of at-risk comorbidities in HIV-infected individuals—for instance, HIV/HCV-coinfected patients are more likely to develop AKI [2].

More than 70% of current admissions are not directly related to AIDS [24, 33], a proportion that is expected to amplify in the years to come. For a given reason of ICU admission, the etiological spectrum is increasingly analogous to what is observed in HIV-uninfected subjects. Indeed, bacterial pneumonia, COPD exacerbation, complicated lung cancer and pulmonary edema due to congestive heart failure have become major causes of ARF, while stroke or Streptococcus pneumoniae meningitis are overtaking classic OIs of the central nervous system (CNS) in patients admitted for life-threatening neurological disorders [2, 3]. Again, chronic HIV infection stands as an independent risk factor for most of these AIDS-unrelated conditions.

Notwithstanding a manifest propensity to these diseases, the clinical presentation of common community-acquired infections does not differ between HIV-infected patients with mild-to-moderate immunosuppression and their seronegative counterparts. This is notably true for pneumonia due to Streptococcus pneumoniae and Legionella pneumophila or bacterial meningitis [34–36]. This also applies for Clostridioides difficile-associated diarrhea and other hospital-acquired infections though HIV-infected patients appear at higher risk for multidrug-resistant pathogens due to frequent healthcare and antimicrobial exposure [37, 38]. Excepting those with profound immune deficiency [6, 39], HIV-infected patients with sepsis exhibit no discrepancies in terms of plasma levels of host response biomarkers, disease severity and survival when compared to HIV-uninfected controls [40, 41]. Therefore, the diagnostic workflow and initial management of HIV-infected patients with a protective CD4 cell count for usual OIs (i.e., above 200–250/µL) has no relevant particularities and should follow standard procedures and guidelines [42].

The spectacular improvement of life expectancy in cART-treated patients offers long-term perspectives that justify maximizing the level of supportive care when indicated. Invasive mechanical ventilation (MV, 40–50% of all admissions), vasopressors (15–30%), and renal replacement therapy for AKI (8–15%) are now used as frequently in seropositive individuals as in the general ICU population [5, 7, 24, 33, 43, 44], with comparable prognoses including in patients at high risk of death such as those admitted following cardiac arrest or with the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [45, 46]. Last-resort veno-venous or veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation can be discussed in selected patients, with auspicious results in published reports [47, 48].

Strikingly, overall in-hospital mortality rates have dropped from more than 80% in the early 80s to 20–40% in most of recent European and US cohorts, a shift that likely reflects general improvement in intensive care such as direct admission from the emergency department, prompt antibiotic initiation and hemodynamic interventions in patients with sepsis, or protective MV settings for ARDS [21–24, 33, 43]. Short-term outcomes of critically ill HIV-infected patients trend to equal those of seronegative subjects with similar demographics, chronic health status and underlying diseases (e.g., HCV or malignancy), reason for admission, and extent of organ dysfunction [32]. CD4 cell count, HIV viral load, prior cART use and an admission for an AIDS-related event (versus other diagnoses) are no longer associated with hospital survival [5, 6, 49, 50].

Common AIDS-defining diagnoses in the ICU

Acute respiratory failure

PCP (overall prevalence, 10–20% of ARF) develops almost exclusively in individuals with CD4 cells < 200/µL, while community-acquired pneumonia (CAP, 30–50%) and pulmonary tuberculosis (up to 20% in high-endemicity areas) may occur at every stage of HIV infection though their incidence increases with lower CD4 cell counts [7, 24, 51–53] (Fig. 1). Severe pneumonia due to non-tuberculosis mycobacteria, CMV, Histoplasma capsulatum, Toxoplasma gondii and Cryptococcus neoformans may rarely occur in patients with CD4 cells < 100/µL [51, 54]. Other features to consider include an history of OI at risk for relapse (e.g., tuberculosis), OI-directed prophylaxis (e.g., second-line PCP prophylaxis such as atovaquone or aerosolized pentamidine are less effective than SXT), the extent of extra-pulmonary failure (e.g., septic shock does not occur during PCP and should trigger the search for bacterial superinfection or a concurrent OI), the presence of HLH (more common with certain OIs such as tuberculosis or disseminated histoplasmosis), radiological patterns, microbiological findings [usual non-invasive samples, plus fiber optic bronchoscopy with bronchoalveloar lavage (BAL) in severely immunosuppressed patients], and a geographical origin at risk for imported OIs. Along this line, an important migratory flow towards Western Europe has occurred throughout the last decade. The prevalence of seropositivity among migrants reflects the epidemiological pattern of their native country, although evidence exists that HIV infection is often acquired in the post-migratory phase [55]. After resettlement, one major driver of AIDS-associated complications in seropositive migrants is the prevalence of a given OI in the country of origin, with tuberculosis being among the greatest concerns [56].

Streptococcus pneumoniae is responsible for 20–40% of CAP in this population [51–53]. Secondary bacteremia and pleuritis are more frequent in patients with CD4 cells < 100/µL, a finding that likely reflects HIV-associated dysfunctions of alveolar macrophages [34, 53]. Legionella pneumophila CAP, an otherwise classic complication of advanced AIDS, is only barely reported in HIV-infected patients admitted to the ICU for ARF [51, 52]. Enterobacterales and Staphylococcus aureus are occasional pathogens, as in HIV-uninfected ICU patients with CAP. Of note, Pseudomonas aeruginosa may cause severe CAP—and should, therefore, be considered in the empirical antimicrobial spectrum—in patients with pulmonary comorbidities and/or severe immunosuppression [51].

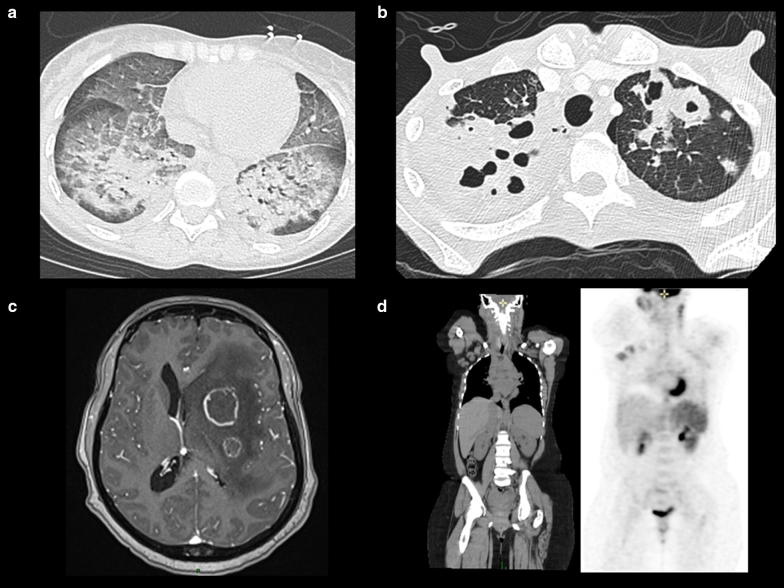

PCP continues to decline in frequency as a cause of ICU admission but remains the most common AIDS-defining OI encountered in the ICU, especially in patients with previously unknown HIV infection [5, 24, 33, 52]. AIDS-related PCP typically presents with worsening exertional dyspnea, non-productive cough and fever over 2–4 weeks—in contrast, PCP arising secondary to SOT or hematological malignancy is often more fulminant [57]. A diagnosis of AIDS-related PCP rests on the identification of cystic or trophic forms of P. jirovecii trough staining and/or immunofluorescence on BAL fluid, which have a > 90% sensitivity and a ~ 100% specificity in patients with a clinical presentation and a CD4 cell count compatible with this condition (Table 1) [54, 58]. The detection of P. jirovecii DNA by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in BAL fluid is highly sensitive but poorly specific in HIV-infected patients due to a high prevalence of colonization (up to 70%) in patients with low CD4 cell counts [59–61]. Serum ß-D-glucan (cut-off level, 80 pg/mL) is also sensitive (> 92%) yet lacks specificity (78–82%) as the test may be positive in other AIDS-related OIs such as invasive candidiasis or histoplasmosis [62, 63]. Typical PCP patterns on high-resolution chest CT scan include reticular infiltrates, intra-parenchymal cysts, patchy or diffuse ground-glass opacities and alveolar consolidation that usually spare the peripheral regions, without pleural effusion or mediastinal lymphadenopathy (Fig. 2). SXT remains the first-choice regimen (Table 1), including in patients developing PCP while receiving this combination as prophylaxis. Whereas its benefit remains debated in other immunosuppressed hosts [64, 65], strong evidence exists for using adjunctive corticosteroid therapy in suspected or proven AIDS-related PCP, with reduced requirement for invasive MV and in-hospital mortality rates when started within 72 h following SXT introduction in patients with PaO2 < 70 mmHg while breathing room air [54, 66].

Table 1.

Adapted from references [3, 54, 58, 71] standard diagnostic methods and therapies for the most common severe opportunistic infections in HIV-infected patients

| Opportunistic infection | Diagnosis | Typical radiological patterns | First-line treatment | Alternative and adjunctive therapies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia |

Staining (e.g., Giemsa or Gomori–Grocott) and immunofluorescence on BAL fluid (Se > 90%) or induced sputum (Se 50–90%) PCR P. jirovecii on BAL fluid: poor specificity, NPV > 95% |

CT scan: patchy or diffuse bilateral ground-glass infiltrates, alveolar consolidations, parenchymal cysts, sparing of subpleural areas, no pleuritis nor lymphadenopathies |

TMP (15–20 mg/kg/day) plus SMX (75–100 mg/kg/day) IV Total duration: 3 weeksa No leucovorin supplementationb |

Pentamidine IV 4 mg/kg/dayc Corticosteroids if PaO2 < 70 mmHg (room air): prednisone PO 40 mg bid (D1–D5), 40 mg daily (D6–D10) then 20 mg daily (D11–D21), or methylprednisolone IV (75% of prednisone dose) |

| Tuberculosis |

All samples: search for AFB, cultures and PCR Mycobacterium tuberculosis CSF (meningitis): variable lymphocytic pleocytosis, low glucose levels, and elevated protein levels (0.5 to > 3 g/L) Serositis and meningitis: adenosine desaminase Tissue biopsies Disseminated tuberculosis: blood cultures |

Pulmonary: usual patterns in patients with CD4 > 200–250/µL (e.g., apical cavitation), common atypical presentations in those with CD4 < 200/µL (e.g., diffuse or miliary pneumonia, lack of cavitation) CNS: basal meningeal inflammation, tuberculomas, hydrocephalus, cerebral vasculitis |

Intensive phase (2 months): isoniazid + rifampin or rifabutin + pyrazinamide + ethambutol Continuation phase: isoniazid + rifampin or rifabutin Total duration: 6–9 months (up to 12 months for CNS tuberculosis) Collaboration with an ID expert for drug-resistant M. tuberculosis |

Consult an ID specialist CNS disease: dexamethasone (0.3–0.4 mg/kg/day for 2–4 weeks, then tapering over 8–10 weeks) Pericardial disease: prednisone or prednisolone (e.g., 60 mg daily with tapering over 6 weeks) |

| Cerebral toxoplasmosis |

Positive IgG serology (uncommon primary infection) PCR Toxoplasma gondii on CSF and blood (Sp > 95%, Se ≤ 50%) |

MRI: multifocal ring-enhanced lesions (sometimes hemorrhagic) in the cortex and/or basal ganglia region, mass effect from peripheral edema, rare solitary lesions or diffuse encephalitis |

Pyrimethamine 200 mg PO once then pyrimethamine 50–75 mg PO daily + sulfadiazine 1000–1500 mg PO q6h + leucovorin 10–25 mg PO daily Total duration > 6 weeksa |

Pyrimethamine (with leucovorin) plus clindamycin, or TMP-SMX Corticosteroids if mass effect |

| Cryptococcus neoformans meningoencephalitis |

CSF: low-to-moderate lymphocytic pleocytosis, mild protein elevation, low-to-normal glucose levels, encapsulated yeasts on Gram or Indian ink staining, positive cultures > 90% Positive blood cultures ~ 50% Cryptococcal antigen on CSF and serum |

MRI: cryptococcal abscesses, hydrocephalus |

Induction therapy (> 2 weeks): AmB-L 3–4 mg/kg IV daily plus flucytosine 25 mg/kg qid Consolidation therapy (> 8 weeks): fluconazole 400 mg dailya |

Induction therapy: high-dose fluconazole with AmB-L or flucytosine No corticosteroids (deleterious outcome effect) |

| Histoplasmosis |

Soluble Histoplasma capsulatum antigen (blood, urines, BAL, low sensitivity in CSF for CNS histoplasmosis) Slowly positive cultures (all samples) > 90% |

Variable depending on disease localizations (mostly disseminated with pulmonary and hepato-splenic involvement, possible CNS, gastro-intestinal and cutaneous lesions) |

Induction therapy (2–6 weeks): AmB-L 3–5 mg/kg/day IV Maintenance therapy (> 12 months): itraconazole PO |

Fluconazole for maintenance therapy |

| Disseminated MAC disease |

Cultures (blood, respiratory sample, bone marrow, others) Species identification though molecular assays |

Variable depending on disease localizations (e.g., diffuse reticulonodular pulmonary infiltrates) | At least two drugs including clarithromycin or azithromycin + ethambutold | – |

| CMV infection |

Positive CMV PCR (e.g., BAL or tissue sample) Histological evidence of CMV infection |

Variable depending on disease localizations (e.g., diffuse interstitial pulmonary infiltrates) |

Ganciclovir 5 mg/kg IV q12h Unsettled optimal treatment duration |

Foscarnet |

| Progressive multifocal encephalopathy (JC virus) | Positive JCV PCR on CSF (70–90%) and/or blood (< 40%) | White matters lesions (demyelination) in deficit-corresponding brain regions | cART |

BAL bronchoalveolar lavage, PCR polymerase chain reaction, NPV negative predictive value, CT computerized tomography, TMP trimethoprim, SMX sulfamethoxazole, AFB acid-fast bacilli, CSF cerebrospinal fluid, CNS central nervous system, IV intravenously, PO per os, AmB-L liposomal amphotericin B, MAC Mycobacterium avium complex, CMV cytomegalovirus, cART combination antiretroviral therapy

aSubsequent switch to secondary prophylaxis/chronic maintenance therapy (usually until a CD4 cell count > 200/µL is reached with cART)

bLeucovorin supplementation does not efficiently prevent myelosuppression and may be associated with treatment failure

cPatients with TMP or SMX adverse events such as allergy or hemolysis due to glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency

dAddition of rifabutin, amikacin and/or fluoroquinolone in patients with CD4 cells < 50/µL, high mycobacterial loads, or cART unresponsiveness

Fig. 2.

Selected imaging examples of AIDS-related opportunistic infections in the ICU. aPneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (chest CT scan showing diffuse ground-glass opacities with focal alveolar consolidations, thickened septal lines, relative sparing of the subpleural regions, and absence of pleural effusion); b pulmonary tuberculosis (chest CT scan showing typical apical excavated lesions with pleural effusion in a patient with CD4 cell count > 250/µL); c cerebral toxoplasmosis (T1-weighted cerebral magnetic resonance imaging showing gadolinium-enhanced lesions of the hemispheric grain matter with peripheral edema and mass effect); d multicentric Castleman disease (positron emission tomography showing enlarged liver, spleen and axillary/cervical lymph nodes with hypermetabolic patterns)

The presentation of pulmonary tuberculosis has no particularity in patients with early HIV infection, while those with CD4 cells < 200/µL more often have atypical lesions (e.g., miliary or diffuse alveolar infiltrates without upper lobe cavitation) and/or extra-respiratory localizations [54, 67]. Nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) should be performed on at least one respiratory sample in HIV-positive patients with suspected tuberculosis, both to distinguish Mycobacterium tuberculosis from other mycobacteria in those with sputum smears positive for acid-fast bacilli (AFB) and to allow earlier detection of M. tuberculosis in AFB-negative sputum smears (sensitivity in AFB-negative/culture-proven tuberculosis, 50–80%) [54, 68]. NAATs including probes for rpoB mutations may also provide information on rifampicin susceptibility weeks before culture-based tests. Interferon-gamma release assays lack sensitivity for diagnosing active tuberculosis and cannot act as a decision-making tool in this indication [54]. The first-line regimen for suspected or definite pulmonary tuberculosis is shown in Table 1. Whether adjunctive corticosteroids exert a beneficial outcome effect in HIV-infected patients with tuberculosis-induced ARF remains to be investigated [69, 70].

Other AIDS-related pulmonary OIs are exceptionally responsible for ARF (Fig. 1).

Neurological admissions

The most prevalent AIDS-related CNS diseases in the ICU are tuberculous meningitis, cerebral toxoplasmosis and cryptococcal meningitis [33, 49] (Fig. 1). These infections occur almost exclusively in patients with CD4 cells < 200/µL. Other CNS OIs such as CMV encephalitis, nocardiosis, aspergillosis or progressive multifocal encephalopathy due to JC virus are highly uncommon. The diagnosis of CNS OIs should be based on clinical signs, temporal evolution, features of contrast-enhanced brain imaging (with magnetic resonance imaging as first-choice procedure), and lumbar puncture for cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis in patients without mass effect at risk for cerebral herniation [71]. Multiple infections may coexist and cerebral OIs may be superimposed on primary HIV-associated neurologic disorders (e.g., HIV encephalitis).

Patients with AIDS-related cerebral toxoplasmosis—an OI resulting from reactivated intra-parenchymal Toxoplasma gondii cysts—may present with impaired mental status, motor deficits or seizures [72]. Fever is inconsistently reported. Multifocal, ring-enhanced, and sometimes hemorrhagic lesions in the cortex and/or basal ganglia are typically observed on MRI (Fig. 2), while single abscess and diffuse encephalitis are more anecdotal. Molecular assays can be helpful in cases of ambiguous clinical presentation or unusual imaging findings [71]. The first-line regimen for suspected cerebral toxoplasmosis is combined pyrimethamine, sulfadiazine, and leucovorin, with adjunctive corticosteroids for patients with threatening mass effect due to lesion-induced edema (Table 1). A brain biopsy must be discussed to search for another OI in patients with atypical presentation, negative IgG serology, or lack of response to empirical therapy as assessed clinically and through repeated brain imaging around day 10.

The clinical presentation of tuberculous meningitis may combine fever, focal signs, subacute mental alterations, and de novo epilepsy [71, 73]. Typical MRI and CSF analysis results are exposed in Table 1. Standard therapy rests on a combination of rifampicin, isoniazid, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide, with no established benefit of high-dose rifampicin or a five-drug regimen including a fluoroquinolone [54, 74]. Adjunctive corticosteroids improve short-term survival—but not the functional prognosis of survivors—and are recommended in this indication [54, 75].

Patients with Cryptococcus neoformans meningitis and meningoencephalitis present with fever, headaches, and impaired mental status due to intra-cranial hypertension. The diagnosis is usually straightforward using CSF analysis (Table 1). The most effective therapeutic regimen includes a combination of amphotericin B and flucytosine for at least 2 weeks then an azole-based consolidation phase after clinical improvement and CSF sterilization [76]. Patients with elevated intra-cranial pressure refractory to repeated removal of large volumes of CSF may benefit from temporary lumbar drain or ventriculo-peritoneal shunt. There is no role for adjunctive acetazolamide, corticosteroids, or sertraline to control CSF pressure [54, 77].

Cytomegalovirus infection

CMV reactivation, detected by quantitative PCR in peripheral blood, is commonly observed in critically ill HIV-infected patients, especially in those with low CD4 cell counts and/or inter-current OIs. Careful assessment should be made for identification of rare end-organ diseases (e.g., retinitis, encephalitis, esophagitis, colitis, or pneumonitis) that require treatment with intravenous ganciclovir or foscarnet [54].

Non-HHV8-associated lymphoma

Non-Hodgkin and Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL and HL, respectively) remain a major cause of mortality in the late cART era, with 33–76% of affected patients having undetectable HIV viral load at diagnosis [78, 79]. NHL are almost constantly aggressive and are often EBV-related [80]. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is still the most frequent type but Burkitt lymphoma (BL) has gained an overgrowing place in recent years and now accounts for 40% of lymphoma-related ICU admissions in seropositive individuals [79]. Primary CNS EBV-induced lymphoma, a hallmark AIDS-defining disease until the early 90s, is now occasional [81].

The reported prevalence of NHL and HL in HIV-infected patients admitted to the ICU may reach 8% and 1.5% in recent cohorts, with inaugural admission in up to 75% of cases [81]. Patients may be admitted for lymphoma-induced HLH, tumor lysis syndrome, organ infiltration or compression, or chemotherapy-related complications such as sepsis in neutropenic patients [81, 82]. Preserving renal function is crucial to optimize subsequent chemotherapy schemes, notably in BL that often requires high-dose methotrexate. NHL at high risk for tumor lysis syndrome—notably DLBCL with large tumor volume and BL—may require preventive ICU admission at the time of induction chemotherapy for fluid management, rasburicase administration, and prompt renal replacement therapy when necessary [83].

In addition to supportive care, the cornerstones of management of HIV-associated lymphoma in the ICU include adequate tissue sampling for diagnostic procedures, whole-body imaging (either CT scan or FDG-positron emission tomography) to appraise tumor burden and localizations, biological evaluation for HLH and tumor lysis syndrome, cardiac evaluation as most chemotherapy regimens are anthracycline-based, prompt administration of etoposide in case of HLH, and timely chemotherapy induction with prevention of tumor lysis syndrome in high-risk patients [84, 85]. Of note, rituximab should not be included in the chemotherapy regimen in patients with CD4 cells < 50/µL due to excess toxicities without survival benefit [86]. The management of cART in this context requires a close collaboration between ICU, hematology and infectious diseases physicians [87]. Overall survival rates depend on tumor characteristics rather than on HIV infection, which does not impact the outcome of lymphoma managed in the ICU [88–90].

HHV8-related diseases

The most frequent human herpes virus 8 (HHV8)-related disease is Kaposi sarcoma (KS), an endothelial cell-derived tumor that may affect various organs and tissues, especially the skin, mucosa, lymph nodes, lungs, and intestinal tract [91, 92]. The severity of KS depends on the presence of life-threatening localizations (e.g., the lower respiratory tract), its extension, and the degree of immune deficiency [51, 91]. The treatment of AIDS-related KS rests on immune restoration through cART and, occasionally, chemotherapy for aggressive presentations. Steroids should be avoided in patients with KS as they can exacerbate the course of the disease [91]. Multicentric Castleman disease is a HHV8-induced polyclonal B lymphoproliferative disorder characterized by recurrent bouts of fever with lymphoid hyperplasia and severe systemic inflammatory symptoms linked to inappropriate release of IL-6, IL-10 and other cytokines, ultimately resulting in HLH and transformation to NHL [93, 94]. Etoposide is the first-line drug for severe associated HLH, while long-term outcomes have markedly improved with the use of rituximab [95]. Primary effusion lymphoma (as diagnosed through positive HHV8 PCR and presence of large B cells in pleural or peritoneal fluid) and DLBCL may also complicate the course of HHV8 infection in seropositive patients.

Combination antiretroviral therapy in the ICU

Admissions for cART-related events

ART-related toxicity accounts for approximately 5% of ICU admissions in this population [2, 3, 7]. Old antiretrovirals are notably associated with lactic acidosis (e.g., AZT, didanosine) or pancreatitis (e.g., didanosine), while proximal tubulopathy with AKI and toxic epidermal necrolysis are well-described adverse events of tenofovir and nevirapine, respectively. New drugs may also cause critical complications such rhabdomyolysis from raltegravir.

Immune recovery may induce paradoxical worsening of an already treated or previously undiagnosed OI within weeks or months after initiating cART. Examples of this immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) include development of ARF in patients with initially mild-to-moderate PCP, or neurological deterioration due to paradoxical enlargement of cerebral tuberculomas, toxoplasma abscesses, or cryptococcal lesions [96]. IRIS-induced HLH has also been reported. Risk factors for IRIS include high baseline viral load, low baseline CD4 cell count, and rapid CD4 cells recovery after starting cART [97]. Steroids are the first-line drugs for severe IRIS, without requirement for interrupting cART in most cases [98].

Starting or continuing cART during critical illness

There are no prospective evaluations of the safety, efficacy and timing of cART administration in the ICU. Clinicians frequently rely on expert opinion to guide decision-making regarding initiating, continuing or stopping cART alongside managing critical illness. Individual case-by-case discussion with an infectious diseases/HIV specialist is recommended.

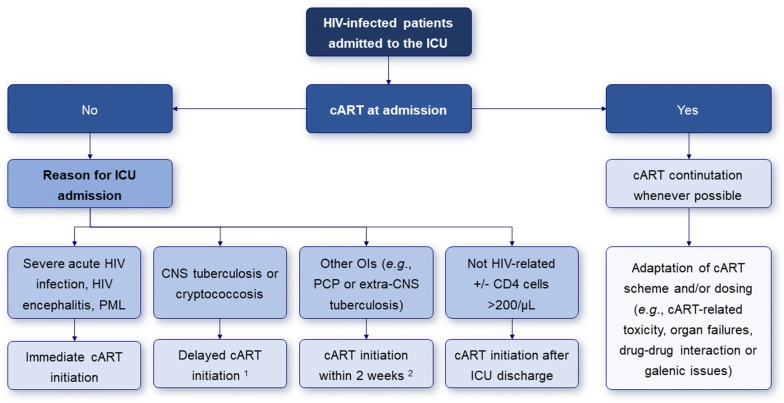

Current US and European guidelines recommend cART initiation at 2 weeks after the start of specific OI treatment, except for those with cryptococcosis or CNS tuberculosis due to the risk of severe IRIS that may outweigh potential benefits from rapid immune recovery—in these situations, cART initiation must be deferred until at least 4 weeks and proven disease control [11, 98]. By contrast, evidence for initiating cART in patients admitted to the ICU with an active OI remains less clear [99]. An algorithm for using cART in the ICU is proposed in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Proposed algorithm for use of combination antiretroviral therapy in the ICU. Authors’ proposal based on the guidelines of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institutes of Health, and the Infectious Diseases Society of America for the use of antiretroviral agents in adults and adolescents with HIV [98]. Note that no academic guidelines exist for the management of antiretroviral drugs in the specific context of critical illnesses. Close collaboration with an infectious disease physician is mandatory in every case. ICU intensive care unit, cART combination antiretroviral therapy, PML progressive multifocal encephalopathy, CNS central nervous system, OI opportunistic infection, PCP Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia. (1) Delayed cART initiation due to the substantial risk of severe immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (e.g., up to 10 weeks in cryptococcal meningoencephalitis with elevated intra-cranial pressure and delayed clinical improvement or CSF culture sterilization); (2) cART initiation may be differed for up to 8 weeks in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis and CD4 cells > 50/µL

In patients treated prior to admission, cART should be continued in the ICU whenever possible. Clinicians should consider the emergence of new HIV resistance mutations due to cART interruption, although the risk is likely limited if the period off cART is short. Factors that may complicate the continuation of cART in critically ill patients include adverse drug reactions, drug–drug interactions, impaired enteral absorption, the need to deliver drugs via a nasogastric tube, avoidance of proton-pump inhibitors, H2 antagonists and other antacids if cART contains components such as atazanavir or rilpivirine (which require gastric acidity for absorption), avoidance of enteral nutrition products containing iron, calcium, magnesium or aluminum to prevent malabsorption of integrase inhibitors, and dose adjustment due to renal and/or hepatic impairment. Drugs available as liquid formulations or that can be crushed are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Important considerations for cART management in ICU patients

| Drug | Most common severe toxicities | Main drug–drug interactions to consider in the ICU | Alternatives for administration in the ICU | Dosage adjustment if renal failure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleoside/nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors | ||||

| Abacavir | Hypersensitivity syndromes in patients with HLA-B*5701 | – | Liquid formulation | No (avoid if end-stage renal failure) |

| Emtricitabine | Neutropenia | – | Liquid formulation, crushable pills | Yes |

| Lamivudine | Rash | – | Liquid formulation, crushable pills | Yes |

| Zidovudine | Lactic acidosis, myopathy, bone marrow toxicity, hepatitis | Rifamycins, valproic acid, fluconazole | Liquid formulation, crushable pills, IV formulation | Yes |

| Tenofovir | Nephrotoxicity (proximal tubular acidosis with Fanconi-like syndrome, acute renal failure), rash, hepatitis | – | Crushable pills | Yes |

| Nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors | ||||

| Efavirenz | Hepatitis, rash | Rifamycins, voriconazole, posaconazole, phenytoin, phenobarbital, carbamazepine, calcium channel blockers, statins, warfarin, midazolam | Crushable pills | No |

| Etravirine | Bone marrow toxicity, hypersensitivity syndromes, hepatitis | Rifamycins, fluconazole, voriconazole, posaconazole, phenytoin, phenobarbital, carbamazepine, digoxin, amiodarone, warfarin, statins, clopidogrel, dexamethasone | Crushable pills | No |

| Nevirapine | Neutropenia, hypersensitivity syndromes, hepatitis | Rifampicin (switch to rifabutin), fluconazole, warfarin | Liquid formulation | Yes |

| Rilpivirine | Bone marrow toxicity, hepatitis, rash | Rifamycins, PPIs, anti-H2, phenytoin, phenobarbital, carbamazepine, dexamethasone | IV formulation | No |

| Integrase inhibitors | ||||

| Raltegravir | Rash | Rifampicin | Liquid formulation, crushable pills | No |

| Dolutegravir | Rash, hepatitis | Rifampicin, phenytoin, phenobarbital, carbamazepine, apixaban, metformin | Crushable pills | No |

| Protease inhibitors (all ritonavir-boosted) | ||||

| Atazanavir | Hyperbilirubinemia, renal lithiasis, QT prolongation | Rifamycins, voriconazole, PPIs, phenytoin, phenobarbital, carbamazepine, fentanyl, midazolam, calcium channel blockers, amiodarone, warfarin, statins | – | No |

| Darunavir | Rash, peripheral neuropathy | Rifamycins, voriconazole, fluconazole, posaconazole, phenytoin, phenobarbital, fentanyl, midazolam, calcium channel blockers, beta-blockers, amiodarone, digoxin, warfarin, apixaban, rivaroxaban, dabigatran, ticagrelor, metformin, statins, salmeterol | Liquid formulation | No |

| Fosamprenavir | Rash | Rifamycins, phenytoin, phenobarbital, fentanyl, midazolam, amiodarone, statins, warfarin | Liquid formulation | No |

| Lopinavir | QT prolongation, bone marrow toxicity, hypersensitivity syndromes, hepatitis | Rifamycins, voriconazole, phenytoin, phenobarbital, valproic acid, fentanyl, midazolam, calcium channel blockers, amiodarone, digoxin, warfarin, rivaroxaban, statins, salmeterol | Liquid formulation | No |

| Tipranavir | Hepatitis, rash | Rifamycins, voriconazole, phenytoin, phenobarbital, carbamazepine, fentanyl, midazolam, PPIs, amiodarone, digoxin, warfarin, statins | Liquid formulation | No |

| Fusion inhibitors | ||||

| Enfuvirtide | Myalgia, lung toxicity, peripheral neuropathy, pancreatitis, renal lithiasis | – | Subcutaneous formulation | No |

| CCR5 inhibitors | ||||

| Maraviroc | Anemia, rash | Rifamycins, phenytoin, phenobarbital, carbamazepine | Liquid formulation | Yes |

Based on Ref. [3] and information obtained from the following sources: http://www.hiv-druginteractions.org, https://liverpool-hiv-hep.s3.amazonaws.com/prescribing_resources/ pdfs/000/000/011/original/ARV_Swallowing_2018_Dec.pdf?1543916096, https://hivclinic.ca/main/drugs_extra_files/Crushing%20and%20Liquid%20ARV%20Formulations.pdf and http://www.eacsociety.org/files/2018_guidelines-9.1-english.pdf. All information refers to licensed use of products and is sourced from individual manufacturers’ Summary of Product Characteristics (emc.medicines.org.uk) and U.S. Prescribing Information. Note that tablet or capsule formulations pooling two or more antiretroviral drugs are not crushable/dissolvable (or available as liquid formulations), except dolutegravir/abacavir/lamivudine, emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and lamivudine/zidovudine; however, individual components of most of combinations are available with such galenic presentations. Dose adjustment may be necessary in patients with renal or hepatic impairment (see the guidelines of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institutes of Health, and the Infectious Diseases Society of America for the use of antiretroviral agents in adults and adolescents with HIV) [98]

PPIs proton-pump inhibitors

Long-term outcomes following critical illness

The widespread use of cART has substantially improved the prognosis of HIV-infected persons and has converted the disorder into a chronic condition, such that successful treatment results in nearly normal life expectancy provided cART is initiated early and there is access to adequate medical care [100, 101]. In some resource-limited regions, however, where access to treatment, availability of appropriate health care facilities (including ICU), social factors, compliance issues and logistics pose serious challenges, this major medical progress may be adversely influenced, potentially affecting long-term outcome. Delayed presentation and impaired functional status are additional factors that impact long-term prognosis following critical illness in these settings. Notwithstanding these challenges, emerging evidence suggests similar and improving trends to those observed in developed settings [102, 103].

Overall, a paucity of data exists with respect to long-term outcomes in this patient population. A recent meta-analysis involving 12 trials revealed significant short-term and long-term (≥ 90 days) mortality benefit following initiation or maintenance of cART in the ICU [99]. A similar beneficial effect has been reported with follow-up extending to 1 year. A deleterious long-term impact of high viral load and low CD4 cell count has been reported though this is not a universal finding. The therapeutic focus of cART is suppression of viral load with concomitant increase in CD4 cell count (Table 3) [104]. Appropriate timing of cART initiation has been associated with improved overall outcomes in critically ill patients with tuberculosis, cryptococcal meningitis and PCP. However, how this impacts long-term survival remains under-investigated.

Table 3.

Expected rise in CD4 cell count following cART initiation

| Time frame | CD4 cell count |

|---|---|

| First month | Increase by 50–75 cells/µL following initiation of cART |

| Each ensuing year | 50–100 cells/µL per year |

| After several years | > 500 cells/µL provided HIV replication remains suppressed (undetectable viral load) |

cART combination antiretroviral therapy

As previously mentioned, seropositive patients surviving to their ICU stay are now at increased hazard of comorbidities associated with aging, chronic HIV infection, and cART-related toxicities [10, 105]. This is especially relevant for cardiovascular and liver diseases, COPD, pulmonary hypertension, certain solid and hematological malignancies, and associated psychiatric disorders, all of which exerting an obvious impact on long-term prognosis. These patients are also exposed to chronic renal disorders that predispose to AKI during the ICU stay, a complication that has been shown to be independently associated with mortality at 1, 2, and 5 years following discharge [106]. Lastly, excessive weight gain has recently emerged as an adverse event of newer antiretrovirals, with the potential for obesity and metabolic disorders [107].

Although major strides have been made, scanty long-term outcome data in critically ill patients necessitates further study to better define and characterize the epidemiology, relevant variables, disparities and regional differences in this group of patients.

Concluding remarks and research perspectives

Once a rapidly progressive and ultimately fatal disease, HIV infection has become a chronic condition with limited impact on quality of life and life expectancy when managed appropriately [108]. Therefore, HIV infection, even at late stages, should never be considered as a stand-alone reason to deny referral to the ICU [2, 3, 109]. Bacterial sepsis and exacerbations of AIDS-unrelated comorbidities—most of them being favored by late HIV infection—now account for the majority of ICU admissions in this population, although severe OIs continue to occur in patients with previously unknown seropositivity or limited access to cART due to sociological or geographical issues (Table 4). As the prevalence of cART use at ICU admission is rising steadily, HIV-infected patients now trend to equal their seronegative counterparts in terms of clinical presentation and short-term outcomes, the latter being mostly impacted by age, performance status, underlying chronic diseases and extent of organ dysfunctions rather than by HIV characteristics.

Table 4.

Ten key features for the management of critically ill HIV-infected patients

| Key features for the management of critically ill HIV-infected patients |

|---|

| 1. Nowadays, up to 70% of HIV-infected patients admitted to the ICU are receiving long-term cART |

| 2. Overall, bacterial sepsis and exacerbated comorbidities have become the leading reasons for ICU admission |

| 3. Admissions for severe AIDS-defining OIs continue to occur in patients with previously unknown HIV infection or restricted access to cART |

| 4. Severely immunocompromised patients may have more than one active AIDS-defining condition at ICU admission |

| 5. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia, tuberculosis and cerebral toxoplasmosis are the most common OIs in the ICU |

| 6. HIV-infected patients are especially at risk for severe HLH secondary to bacterial or opportunistic infections and hematological malignancies |

| 7. The management of cART in the ICU requires a close collaboration between intensivists and HIV specialists |

| 8. In-hospital mortality mostly depends on age, underlying comorbidities and extent of organ dysfunctions rather on HIV-related characteristics (i.e., CD4 cell count, viral load, admission for AIDS-related diagnoses, and prior cART use) |

| 9. Lymphomas, solid neoplasms and SOT are emerging drivers of immunosuppression in cART-treated patients with otherwise controlled HIV replication |

| 10. Ethical issues and long-term outcomes warrant dedicated investigations in this patient population |

Several emerging research areas warrant prospective investigations in HIV-infected patients requiring ICU admission. These notably include (i) the weight of sociological parameters and limited access to HIV-specific care on admission features and prognosis, (ii) the timing and management of cART in the particular context of critical illness, (iii) the long-term outcomes of ICU survivors in terms of HIV control, residual immune deficiency, progression of associated chronic diseases, cognitive status, and quality of life, (iv) the impact of novel drivers of immune impairment—for instance, SOT and solid or hematological malignancies—on the clinical presentation and prognosis of patients with otherwise controlled HIV replication under cART, and (v) ethical issues in an era of improved overall survival, with assessment of decision-making factors (i.e., HIV-specific parameters versus AIDS-unrelated characteristics such as age, comorbidities and nutritional status) for withholding or withdrawal of life-sustaining therapies in the most severely ill patients.

Funding

No funding was received for this work.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflicts of interest

FB: MSD (advisory board, lecture fees, and conference invitation), BioMérieux (lecture fees) and Pfizer (conference invitation). RFM: Gilead (lecture fees and conference invitation). EM: Sanofi (lecture fees). PT: Gilead, Astellas, Coreviome, MSD, Mylan, and Pfizer (consulting fees) and Astellas, BioMérieux, Gilead, Pfizer, and MSD (congress or research activities). EA: Gilead, Pfizer, Baxter and Alexion (lecture fees), and Ablynx, Fisher & Payckle, Jazz Pharma, and MSD (financial support for his research group). Other authors have no potential conflict of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

François Barbier, Email: francois.barbier@chr-orleans.fr.

Élie Azoulay, Email: elie.azoulay@aphp.fr.

References

- 1.World Health Organization (2019) Global HIV and AIDS statistics. http://www.unaids.org. Accessed 1 Nov 2019

- 2.Akgun KM, Miller RF. Critical care in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;37(2):303–317. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1572561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azoulay E, de Castro N, Barbier F. Critically ill patients with HIV: 40 years later. Chest. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akgun KM, Gordon K, Pisani M, Fried T, McGinnis KA, Tate JP, et al. Risk factors for hospitalization and medical intensive care unit (MICU) admission among HIV-infected Veterans. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;62(1):52–59. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318278f3fa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coquet I, Pavie J, Palmer P, Barbier F, Legriel S, Mayaux J, et al. Survival trends in critically ill HIV-infected patients in the highly active antiretroviral therapy era. Crit Care. 2010;14(3):R107. doi: 10.1186/cc9056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Japiassu AM, Amancio RT, Mesquita EC, Medeiros DM, Bernal HB, Nunes EP, et al. Sepsis is a major determinant of outcome in critically ill HIV/AIDS patients. Crit Care. 2010;14(4):R152. doi: 10.1186/cc9221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiang HH, Hung CC, Lee CM, Chen HY, Chen MY, Sheng WH, et al. Admissions to intensive care unit of HIV-infected patients in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: etiology and prognostic factors. Crit Care. 2011;15(4):R202. doi: 10.1186/cc10419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xiao J, Zhang W, Huang Y, Tian Y, Su W, Li Y, et al. Etiology and outcomes for patients infected with HIV in intensive care units in a tertiary care hospital in China. J Med Virol. 2015;87(3):366–374. doi: 10.1002/jmv.24063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kwizera A, Nabukenya M, Peter A, Semogerere L, Ayebale E, Katabira C, et al. Clinical characteristics and short-term outcomes of HIV patients admitted to an african intensive care unit. Crit Care Res Pract. 2016;2016:2610873. doi: 10.1155/2016/2610873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deeks SG, Lewin SR, Havlir DV. The end of AIDS: HIV infection as a chronic disease. Lancet. 2013;382(9903):1525–1533. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61809-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization (2016) Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection: recommendations for a public health approach, 2nd edn. https://www.who.int. Accessed 1 Nov 2019 [PubMed]

- 12.Althoff KN, McGinnis KA, Wyatt CM, Freiberg MS, Gilbert C, Oursler KK, et al. Comparison of risk and age at diagnosis of myocardial infarction, end-stage renal disease, and non-AIDS-defining cancer in HIV-infected vs uninfected adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;60:627–638. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Freiberg MS, Chang CC, Kuller LH, Skanderson M, Lowy E, Kraemer KL, et al. HIV infection and the risk of acute myocardial infarction. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;2013:1–9. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.3728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lanoy E, Spano JP, Bonnet F, Guiguet M, Boue F, Cadranel J, et al. The spectrum of malignancies in HIV-infected patients in 2006 in France: the ONCOVIH study. Int J Cancer. 2011;129(2):467–475. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crothers K, Huang L, Goulet JL, Goetz MB, Brown ST, Rodriguez-Barradas MC, et al. HIV infection and risk for incident pulmonary diseases in the combination antiretroviral therapy era. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(3):388–395. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201006-0836OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sigel K, Wisnivesky J, Gordon K, Dubrow R, Justice A, Brown ST, et al. HIV as an independent risk factor for incident lung cancer. AIDS. 2012;26(8):1017–1025. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328352d1ad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hleyhel M, Belot A, Bouvier A-M, Tattevin P, Pacanowski J, Genet P, et al. Risk of AIDS-defining cancers among HIV-1-infected patients in France between 1992 and 2009: results from the FHDH-ANRS C04 Cohort. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57(11):1638–1647. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gutierrez J, Albuquerque ALA, Falzon L. HIV infection as vascular risk: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12(5):e0176686. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hart BB, Nordell AD, Okulicz JF, Palfreeman A, Horban A, Kedem E, et al. Inflammation-related morbidity and mortality among HIV-positive adults: how extensive is it? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2018;77(1):1–7. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gootenberg DB, Paer JM, Luevano JM, Kwon DS. HIV-associated changes in the enteric microbial community: potential role in loss of homeostasis and development of systemic inflammation. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2017;30(1):31–43. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turtle L, Vyakernam R, Menon-Johansson A, Nelson MR, Soni N. Intensive care usage by HIV-positive patients in the HAART Era. Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis. 2011;2011:847835. doi: 10.1155/2011/847835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Lelyveld SF, Wind CM, Mudrikova T, van Leeuwen HJ, de Lange DW, Hoepelman AI. Short- and long-term outcome of HIV-infected patients admitted to the intensive care unit. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;30(9):1085–1093. doi: 10.1007/s10096-011-1196-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morquin D, Le Moing V, Mura T, Makinson A, Klouche K, Jonquet O, et al. Short- and long-term outcomes of HIV-infected patients admitted to the intensive care unit: impact of antiretroviral therapy and immunovirological status. Ann Intensive Care. 2012;2(1):25. doi: 10.1186/2110-5820-2-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akgun KM, Tate JP, Pisani M, Fried T, Butt AA, Gibert CL, et al. Medical ICU admission diagnoses and outcomes in human immunodeficiency virus-infected and virus-uninfected veterans in the combination antiretroviral era. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(6):1458–1467. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827caa46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Botha J, Fabian J, Etheredge H, Conradie F, Tiemessen CT. HIV and solid organ transplantation: where are we now. Curr HIV AIDS Rep. 2019;16:404–413. doi: 10.1007/s11904-019-00460-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Madan S, Patel SR, Saeed O, Sims DB, Shin JJ, Goldstein DJ, et al. Outcomes of heart transplantation in patients with human immunodeficiency virus. Am J Transplant. 2019 doi: 10.1111/ajt.15257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sawinski D, Bloom RD. Current status of kidney transplantation in HIV-infected patients. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2014;23(6):619–624. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee EJ, Kim YH, Lee JY, Sunwoo JS, Park SY, Kim TH. Acute HIV-1 infection presenting with fulminant encephalopathy. Int J STD AIDS. 2017;28(10):1041–1044. doi: 10.1177/0956462417693734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tattevin P, Camus C, Arvieux C, Ruffault A, Michelet C. Multiple organ failure during primary HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(3):e28–e29. doi: 10.1086/510683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ferrada MA, Xie Y, Nuermberger E. Primary HIV infection presenting as limbic encephalitis and rhabdomyolysis. Int J STD AIDS. 2015;26(11):835–836. doi: 10.1177/0956462414560777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vandi G, Calza L, Girometti N, Manfredi R, Musumeci G, Bon I, et al. Acute onset myopericarditis as unusual presentation of primary HIV infection. Int J STD AIDS. 2017;28(2):199–201. doi: 10.1177/0956462416654852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dickson SJ, Batson S, Copas AJ, Edwards SG, Singer M, Miller RF. Survival of HIV-infected patients in the intensive care unit in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Thorax. 2007;62(11):964–968. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.072256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barbier F, Roux A, Canet E, Martel-Samb P, Aegerter P, Wolff M, et al. Temporal trends in critical events complicating HIV infection: 1999–2010 multicentre cohort study in France. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40:1906–1915. doi: 10.1007/s00134-014-3481-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cilloniz C, Torres A, Manzardo C, Gabarrus A, Ambrosioni J, Salazar A, et al. Community-acquired pneumococcal pneumonia in virologically suppressed HIV-infected adult patients: a matched case-control study. Chest. 2017;152(2):295–303. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cilloniz C, Miguel-Escuder L, Pedro-Bonet ML, Falco V, Lopez Y, Garcia-Vidal C, et al. Community-acquired Legionella pneumonia in Human Immunodeficiency Virus-infected adult patients: a matched case-control study. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;67(6):958–961. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Veen KE, Brouwer MC, van der Ende A, van de Beek D. Bacterial meningitis in patients with HIV: a population-based prospective study. J Infect. 2016;72(3):362–368. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2016.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Imlay H, Kaul D, Rao K. Risk factors for Clostridium difficile infection in HIV-infected patients. SAGE Open Med. 2016;4:2050312116684295. doi: 10.1177/2050312116684295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sanchez TH, Brooks JT, Sullivan PS, Juhasz M, Mintz E, Dworkin MS, et al. Bacterial diarrhea in persons with HIV infection, United States, 1992–2002. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(11):1621–1627. doi: 10.1086/498027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cribbs SK, Tse C, Andrews J, Shenvi N, Martin GS. Characteristics and outcomes of HIV-infected patients with severe sepsis: continued risk in the post-highly active antiretroviral therapy era. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(8):1638–1645. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huson MA, Scicluna BP, van Vught LA, Wiewel MA, Hoogendijk AJ, Cremer OL, et al. The impact of HIV co-infection on the genomic response to sepsis. PLoS One. 2016;11(2):e0148955. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wiewel MA, Huson MA, van Vught LA, Hoogendijk AJ, Klein Klouwenberg PM, Horn J, et al. Impact of HIV infection on the presentation, outcome and host response in patients admitted to the intensive care unit with sepsis; a case control study. Crit Care. 2016;20(1):322. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1469-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, Levy MM, Antonelli M, Ferrer R, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock, 2016. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43(3):304–377. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-4683-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meybeck A, Lecomte L, Valette M, Van Grunderbeeck N, Boussekey N, Chiche A, et al. Should highly active antiretroviral therapy be prescribed in critically ill HIV-infected patients during the ICU stay? A retrospective cohort study. AIDS Res Ther. 2012;9(1):27. doi: 10.1186/1742-6405-9-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Turvey SL, Bagshaw SM, Eurich DT, Sligl WI. Epidemiology and outcomes in critically ill patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection in the era of combination antiretroviral therapy. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2017;2017:7868954. doi: 10.1155/2017/7868954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mongardon N, Geri G, Deye N, Sonneville R, Boissier F, Perbet S, et al. Etiologies, clinical features and outcome of cardiac arrest in HIV-infected patients. Int J Cardiol. 2015;201:302–307. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.08.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mendez-Tellez PA, Damluji A, Ammerman D, Colantuoni E, Fan E, Sevransky JE, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus infection and hospital mortality in acute lung injury patients. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(7):1530–1535. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181e2a44b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Collett LW, Simpson T, Camporota L, Meadows CI, Ioannou N, Glover G, et al. The use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in HIV-positive patients with severe respiratory failure: a retrospective observational case series. Int J STD AIDS. 2018;2018:956462418805606. doi: 10.1177/0956462418805606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Obata R, Azuma K, Nakamura I, Oda J. Severe acute respiratory distress syndrome in a patient with AIDS successfully treated with veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: a case report and literature review. Acute Med Surg. 2018;5(4):384–389. doi: 10.1002/ams2.364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sonneville R, Ferrand H, Tubach F, Roy C, Bouadma L, Klein IF, et al. Neurological complications of HIV infection in critically ill patients: clinical features and outcomes. J Infect. 2011;62(4):301–308. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Medrano J, Alvaro-Meca A, Boyer A, Jimenez-Sousa MA, Resino S. Mortality of patients infected with HIV in the intensive care unit (2005 through 2010): significant role of chronic hepatitis C and severe sepsis. Crit Care. 2014;18(4):475. doi: 10.1186/s13054-014-0475-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barbier F, Coquet I, Legriel S, Pavie J, Darmon M, Mayaux J, et al. Etiologies and outcome of acute respiratory failure in HIV-infected patients. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35(10):1678–1686. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1559-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cilloniz C, Torres A, Polverino E, Gabarrus A, Amaro R, Moreno E, et al. Community-acquired lung respiratory infections in HIV-infected patients: microbial aetiology and outcome. Eur Respir J. 2014;43(6):1698–1708. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00155813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Segal LN, Methe BA, Nolan A, Hoshino Y, Rom WN, Dawson R, et al. HIV-1 and bacterial pneumonia in the era of antiretroviral therapy. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2011;8(3):282–287. doi: 10.1513/pats.201006-044WR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention tNIoH, the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in HIV-infected adults and adolescents. http://www.aidsinfo.nih.gov. Accessed 1 Nov 2019

- 55.Pannetier J, Ravalihasy A, Lydie N, Lert F, du Lou DA. Prevalence and circumstances of forced sex and post-migration HIV acquisition in sub-Saharan African migrant women in France: an analysis of the ANRS-PARCOURS retrospective population-based study. Lancet Public Health. 2018;3(1):e16–e23. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30211-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McCarthy AE, Weld LH, Barnett ED, So H, Coyle C, Greenaway C, et al. Spectrum of illness in international migrants seen at GeoSentinel clinics in 1997–2009, part 2: migrants resettled internationally and evaluated for specific health concerns. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(7):925–933. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Roux A, Canet E, Valade S, Gangneux-Robert F, Hamane S, Lafabrie A, et al. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in patients with or without AIDS, France. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20(9):1490–1497. doi: 10.3201/eid2009.131668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Miller RF, Walzer PD, Smulian AG (2019) Pneumocystis species—Chapter 269 in: Mandell, Douglas and Benett’s Principles and practices of infectious diseases, 9th edn. In: Benett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ (eds) Elsiever Science, Amsterdam

- 59.Morris A, Wei K, Afshar K, Huang L. Epidemiology and clinical significance of pneumocystis colonization. J Infect Dis. 2008;197(1):10–17. doi: 10.1086/523814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Louis M, Guitard J, Jodar M, Ancelle T, Magne D, Lascols O, et al. Impact of HIV infection status on interpretation of quantitative PCR for detection of Pneumocystis jirovecii. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53(12):3870–3875. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02072-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fauchier T, Hasseine L, Gari-Toussaint M, Casanova V, Marty PM, Pomares C. Detection of Pneumocystis jirovecii by quantitative PCR to differentiate colonization and pneumonia in immunocompromised HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54(6):1487–1495. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03174-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li WJ, Guo YL, Liu TJ, Wang K, Kong JL. Diagnosis of pneumocystis pneumonia using serum (1-3)-beta-D-Glucan: a bivariate meta-analysis and systematic review. J Thorac Dis. 2015;7(12):2214–2225. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.12.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Onishi A, Sugiyama D, Kogata Y, Saegusa J, Sugimoto T, Kawano S, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of serum 1,3-beta-d-glucan for Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia, invasive candidiasis, and invasive aspergillosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50(1):7–15. doi: 10.1128/JCM.05267-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wieruszewski PM, Barreto JN, Frazee E, Daniels CE, Tosh PK, Dierkhising RA, et al. Early corticosteroids for Pneumocystis pneumonia in adults without HIV are not associated with better outcome. Chest. 2018;154(3):636–644. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lemiale V, Debrumetz A, Delannoy A, Alberti C, Azoulay E. Adjunctive steroid in HIV-negative patients with severe Pneumocystis pneumonia. Respir Res. 2013;14:87. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-14-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ewald H, Raatz H, Boscacci R, Furrer H, Bucher HC, Briel M. Adjunctive corticosteroids for Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in patients with HIV infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;4:CD006150. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006150.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lanoix JP, Gaudry S, Flicoteaux R, Ruimy R, Wolff M. Tuberculosis in the intensive care unit: a descriptive analysis in a low-burden country. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2014;18(5):581–587. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.13.0901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dorman SE, Schumacher SG, Alland D, Nabeta P, Armstrong DT, King B, et al. Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra for detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and rifampicin resistance: a prospective multicentre diagnostic accuracy study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):76–84. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30691-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Critchley JA, Young F, Orton L, Garner P. Corticosteroids for prevention of mortality in people with tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(3):223–237. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70321-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yang JY, Han M, Koh Y, Kim WS, Song JW, Oh YM, et al. Effects of corticosteroids on critically ill pulmonary tuberculosis patients with acute respiratory failure: a propensity analysis of mortality. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(11):1449–1455. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sonneville R, Magalhaes E, Meyfroidt G. Central nervous system infections in immunocompromised patients. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2017;23(2):128–133. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sonneville R, Schmidt M, Messika J, Ait Hssain A, da Silva D, Klein IF, et al. Neurologic outcomes and adjunctive steroids in HIV patients with severe cerebral toxoplasmosis. Neurology. 2012;79(17):1762–1766. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182704040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cantier M, Morisot A, Guerot E, Megarbane B, Razazi K, Contou D, et al. Functional outcomes in adults with tuberculous meningitis admitted to the ICU: a multicenter cohort study. Crit Care. 2018;22(1):210. doi: 10.1186/s13054-018-2140-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Heemskerk AD, Bang ND, Mai NT, Chau TT, Phu NH, Loc PP, et al. Intensified antituberculosis therapy in adults with tuberculous meningitis. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(2):124–134. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Prasad K, Singh MB, Ryan H. Corticosteroids for managing tuberculous meningitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;4:CD002244. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002244.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Day JN, Chau TT, Lalloo DG. Combination antifungal therapy for cryptococcal meningitis. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(26):2522–2523. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1305981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Beardsley J, Wolbers M, Kibengo FM, Ggayi AB, Kamali A, Cuc NT, et al. Adjunctive dexamethasone in HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(6):542–554. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1509024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Vandenhende MA, Roussillon C, Henard S, Morlat P, Oksenhendler E, Aumaitre H, et al. Cancer-related causes of death among HIV-infected patients in France in 2010: evolution since 2000. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0129550. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ramaswami R, Chia G, Dalla Pria A, Pinato DJ, Parker K, Nelson M, et al. Evolution of HIV-associated lymphoma over three decades. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;72(2):177–183. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gerard L, Meignin V, Galicier L, Fieschi C, Leturque N, Piketty C, et al. Characteristics of non-Hodgkin lymphoma arising in HIV-infected patients with suppressed HIV replication. AIDS. 2009;23(17):2301–2308. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328330f62d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Algrin C, Faguer S, Lemiale V, Lengline E, Boutboul D, Amorim S, et al. Outcomes after intensive care unit admission of patients with newly diagnosed lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2015;56(5):1240–1245. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2014.922181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fardet L, Lambotte O, Meynard JL, Kamouh W, Galicier L, Marzac C, et al. Reactive haemophagocytic syndrome in 58 HIV-1-infected patients: clinical features, underlying diseases and prognosis. AIDS. 2010;24(9):1299–1306. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328339e55b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Canet E, Zafrani L, Lambert J, Thieblemont C, Galicier L, Schnell D, et al. Acute kidney injury in patients with newly diagnosed high-grade hematological malignancies: impact on remission and survival. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e55870. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bigenwald C, Fardet L, Coppo P, Meignin V, Lazure T, Fabiani B, et al. A comprehensive analysis of lymphoma-associated haemophagocytic syndrome in a large French multicentre cohort detects some clues to improve prognosis. Br J Haematol. 2018;183(1):68–75. doi: 10.1111/bjh.15506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zafrani L, Canet E, Darmon M. Understanding tumor lysis syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 2019;45(11):1608–1611. doi: 10.1007/s00134-019-05768-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Barta SK, Xue X, Wang D, Tamari R, Lee JY, Mounier N, et al. Treatment factors affecting outcomes in HIV-associated non-Hodgkin lymphomas: a pooled analysis of 1546 patients. Blood. 2013;122(19):3251–3262. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-04-498964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gerard L, Galicier L, Maillard A, Boulanger E, Quint L, Matheron S, et al. Systemic non-Hodgkin lymphoma in HIV-infected patients with effective suppression of HIV replication: persistent occurrence but improved survival. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;30(5):478–484. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200208150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Montoto S, Shaw K, Okosun J, Gandhi S, Fields P, Wilson A, et al. HIV status does not influence outcome in patients with classical Hodgkin lymphoma treated with chemotherapy using doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine in the highly active antiretroviral therapy era. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(33):4111–4116. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.41.4193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ferre C, de Guzmao BM, Morgades M, Lacoma A, Marcos P, Jimenez-Lorenzo MJ, et al. Lack of impact of human immunodeficiency virus infection on the outcome of lymphoma patients transferred to the intensive care unit. Leuk Lymphoma. 2012;53(10):1966–1970. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2012.543715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Barta SK, Samuel MS, Xue X, Wang D, Lee JY, Mounier N, et al. Changes in the influence of lymphoma- and HIV-specific factors on outcomes in AIDS-related non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(5):958–966. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Dittmer DP, Damania B. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV)-associated disease in the AIDS patient: an update. Cancer Treat Res. 2019;177:63–80. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-03502-0_3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yarchoan R, Uldrick TS. HIV-associated cancers and related diseases. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(22):2145. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1804812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Oksenhendler E, Boutboul D, Fajgenbaum D, Mirouse A, Fieschi C, Malphettes M, et al. The full spectrum of Castleman disease: 273 patients studied over 20 years. Br J Haematol. 2018;180(2):206–216. doi: 10.1111/bjh.15019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Oksenhendler E, Carcelain G, Aoki Y, Boulanger E, Maillard A, Clauvel JP, et al. High levels of HHV8 viral load, human interleukin-6, interleukin-10, and C reactive protein correlate with exacerbation of multicentric castleman disease in HIV-infected patients. Blood. 2000;96(6):2069–2073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gerard L, Michot JM, Burcheri S, Fieschi C, Longuet P, Delcey V, et al. Rituximab decreases the risk of lymphoma in patients with HIV-associated multicentric Castleman disease. Blood. 2012;119(10):2228–2233. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-08-376012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Manzardo C, Guardo AC, Letang E, Plana M, Gatell JM, Miro JM. Opportunistic infections and immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in HIV-1-infected adults in the combined antiretroviral therapy era: a comprehensive review. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2015;13(6):751–767. doi: 10.1586/14787210.2015.1029917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Muller M, Wandel S, Colebunders R, Attia S, Furrer H, Egger M. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in patients starting antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10(4):251–261. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70026-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institutes of Health, America atIDSo. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in adults and adolescents with HIV. http://www.aidsinfo.nih.gov. Accessed 1 Nov 2019

- 99.Andrade HB, Shinotsuka CR, da Silva IRF, Donini CS, Yeh Li H, de Carvalho FB, et al. Highly active antiretroviral therapy for critically ill HIV patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):e0186968. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.May MT, Gompels M, Delpech V, Porter K, Orkin C, Kegg S, et al. Impact on life expectancy of HIV-1 positive individuals of CD4+ cell count and viral load response to antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2014;28(8):1193–1202. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.The Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort Collaboration Survival of HIV-positive patients starting antiretroviral therapy between 1996 and 2013: a collaborative analysis of cohort studies. Lancet HIV. 2017;4(8):e349–e356. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(17)30066-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]