Dear Editor,

Detractors of corticosteroids use in patients affected by severe H1N1 virus infections advocate the World Health Organization (WHO) statements to support their argumentations [1]. However, it should be noted that some of WHO’s recommendations are not evidence-based. WHO recommendations that “corticosteroids should be avoided” in severely ill H1N1-infected patients seem to be based on the possibility of viral shedding by using corticosteroids during severe H1N1 infection [2]. Really, there is not any evidence in the literature that the viral load could return to peak levels for the administration of corticosteroids, whilst only the detection of some viral RNA in body samples during convalescence may have no clinical significance [3]. Moreover, data from quantitative analysis of viral shedding may have more important implications for formulating clinical prognosis and risks.

We had the opportunity to treat with methylprednisolone (MP) infusion (1 mg/kg/24 h) a previously healthy 30-year-old man with H1N1-related acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and severe sepsis who did not respond to oseltamivir (150 mg bid for 7 days) started 4 days after the onset of symptoms.

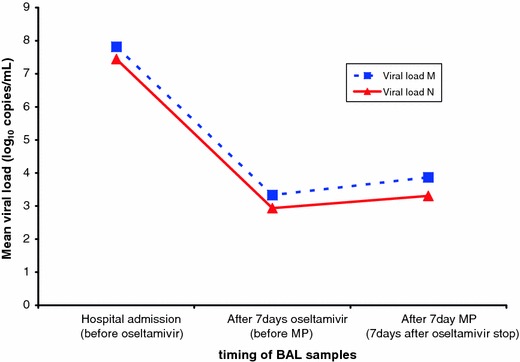

Molecular diagnosis of pandemic influenza H1N1 virus infection was performed on bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) with the CDC Realtime RTPCR (rtPCR) on hospital admission and a viral load profile was assessed on weekly repeated BAL samples. The quality of RNA purified from the samples was assessed by an rRTPCR primers/probe panel directed to the human RNase P gene (Invitrogen SuperScript™ III Platinum® One-Step Quantitative Kit). At ICU admission, the physician in charge avoided treating the patient with corticosteroids in accordance with the recommendations of WHO, but after a week of oseltamivir, protective mechanical ventilation (MV), pronation, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), the patient was still in a life-threatening condition, so MP infusion was initiated. Within a few days, the patient significantly improved and, after 6 and 10 days, respectively, he was weaned from ECMO and MV without any major adverse effect. The initial viral load in BAL before oseltamivir was 6.54 × 108 copies/ml, then reduced to 2.14 × 103 copies/ml when oseltamivir stopped and MP started, and mildly increased to a maximum of 7.40 × 103 copies/ml after 7 days of MP infusion (Fig. 1). The magnitude of virus copies amount was consistent with a clear reduction in comparison to the initial viral load in spite of adjunct corticosteroids. The viral load was determined by using the Quantification of Swine H1N1 Influenza Human Pandemic Strain-Advanced Kit (PrimerDesign, Southampton, UK). No viral mutations associated with virulence (D222G) and resistance to oseltamivir (H274Y) were detected by sequencing Ha and NA genes.

Fig. 1.

Treatment time course and viral load profile on BAL samples. Quantification of viral load was performed by using M1 (viral load M) and N1 (viral load N) primers/probes directed to regions of matrix and neuraminidase genes, respectively. MP methylprednisolone, BAL bronchoalveolar lavage, M matrix gene, N neuraminidase gene

The efficacy of corticosteroids needs to be adequately demonstrated in patients with severe influenza. Nevertheless, at least a third of H1N1 cases in the literature were treated with corticosteroids [4] with some indication of a favourable outcome [5] and no report of harmful consequences [4]. The supposed viral shedding by corticosteroids use should not be advocated to avoid corticosteroid therapy in H1N1 severe infections, but it should be determined with quantitative viral load profile.

References

- 1.Salluh JIF, Póvoa P. Corticosteroids for H1N1 associated acute lung injury: is it just wishful thinking? Intensive Care Med. 2010;36:1098. doi: 10.1007/s00134-010-1815-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization (2009) Clinical management of human infection with pandemic (H1N1) 2009: revised guidance, November 2009. (http://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/swineflu/clinical_management_h1n1.pdf). Accessed 6 May 2010

- 3.Witkop CT, Duffy MR, Macias EA, Gibbons TF, Escobar JD, Burwell KN, Knight KK. Novel influenza A (H1N1) outbreak at the US Air Force Academy: epidemiology and viral shedding duration. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38:121–126. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Falagas ME, Vouloumanou EK, Baskouta E, Rafailidis PI, Polyzos K, Rello J. Treatment options for 2009 H1N1 influenza: evaluation of the published evidence. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2010;35:421–430. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Quispe-Laime AM, Bracco JD, Barberio PA, Campagne CG, Rolfo VE, Umberger R, Meduri GU. H1N1 influenza A virus-associated acute lung injury: response to combination oseltamivir and prolonged corticosteroid treatment. Intensive Care Med. 2009;36:33–41. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1727-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]