Human coronavirus-EMC (hCoV-EMC) is a new coronavirus that has killed around half of the few humans infected so far; this study now identifies DPP4 as the receptor that this virus uses to infect cells.

Supplementary information

The online version of this article (doi:10.1038/nature12005) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Subject terms: Viral pathogenesis

Human receptor for emerging coronavirus

The emerging pathogenic coronavirus hCoV-EMC, first identified in September 2012, has been fatal in about half of the few humans infected so far. Bart Haagmans and colleagues have now identified the receptor that this virus uses to infect cells. In contrast to the related virus SARS-CoV, which uses angiotensin converting enzyme 2, the functional receptor for hCoV-EMC is dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4, also known as CD26), an exopeptidase found on non-ciliated cells in the lower respiratory tract. This enzyme is highly conserved across different species, and hCoV-EMC can also use bat DPP4 as a functional receptor — a possible clue as to the host range and epidemiological history of this new virus. The findings may also be important for the development of intervention strategies.

Supplementary information

The online version of this article (doi:10.1038/nature12005) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Abstract

Most human coronaviruses cause mild upper respiratory tract disease but may be associated with more severe pulmonary disease in immunocompromised individuals1. However, SARS coronavirus caused severe lower respiratory disease with nearly 10% mortality and evidence of systemic spread2. Recently, another coronavirus (human coronavirus-Erasmus Medical Center (hCoV-EMC)) was identified in patients with severe and sometimes lethal lower respiratory tract infection3,4. Viral genome analysis revealed close relatedness to coronaviruses found in bats5. Here we identify dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4; also known as CD26) as a functional receptor for hCoV-EMC. DPP4 specifically co-purified with the receptor-binding S1 domain of the hCoV-EMC spike protein from lysates of susceptible Huh-7 cells. Antibodies directed against DPP4 inhibited hCoV-EMC infection of primary human bronchial epithelial cells and Huh-7 cells. Expression of human and bat (Pipistrellus pipistrellus) DPP4 in non-susceptible COS-7 cells enabled infection by hCoV-EMC. The use of the evolutionarily conserved DPP4 protein from different species as a functional receptor provides clues about the host range potential of hCoV-EMC. In addition, it will contribute critically to our understanding of the pathogenesis and epidemiology of this emerging human coronavirus, and may facilitate the development of intervention strategies.

Supplementary information

The online version of this article (doi:10.1038/nature12005) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Main

Coronaviruses infect a wide range of mammals and birds. Their tropism is primarily determined by the ability of the spike (S) entry protein to bind to a cell surface receptor. Coronaviruses have zoonotic potential due to the adaptability of their S protein to receptors of other species, most notably demonstrated by SARS-CoV6, the causative agent of the SARS epidemic, which probably originated from bats7. Recently, a new coronavirus, named hCoV-EMC, has been identified in 13 patients to date with seven fatalities that suffered from severe respiratory illness, in some cases accompanied with renal dysfunction3,4,8. Genetically the virus is similar to bat coronaviruses HKU4 and HKU5 and—based on phylogenetic analysis using a small fragment of the virus—to a bat coronavirus found in Pipistrellus pipistrellus in the Netherlands5. In recent years molecular surveillance studies revealed the existence of at least 60 novel bat coronaviruses, including some closely related to SARS-CoV9. As the human cases do not seem to originate from transmission from one source, the epidemiology of hCoV-EMC may be explained by a concealed circulation in the human population or by the repeated introduction from an intermediate animal host. For a better understanding of the biology of this novel coronavirus, timely identification of the receptor could reveal important clues to its zoonotic transmission potential and pathogenesis and to the design of possible intervention strategies. Two types of coronavirus protein receptors have been identified: the Betacoronavirus mouse hepatitis virus uses immunoglobulin-related carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecules (CEACAM)10 to enter cells, whereas for several Alpha- and Betacoronaviruses, two peptidases have been identified as receptors (aminopeptidase N (APN, CD13) for hCoV-229E and several animal coronaviruses11,12, and angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) for SARS-CoV13). In addition, sialic acid may act as a receptor for some coronaviruses14.

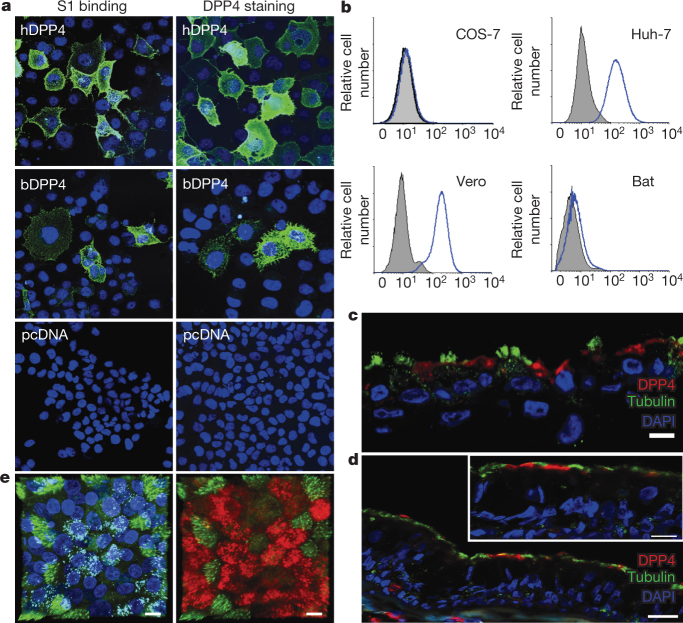

Our initial experiments indicated that hCoV-EMC does not use ACE2 as an entry receptor15. Therefore we first examined whether the amino-terminal receptor-binding spike domain S1 binds to cells and investigated its correlation with cell susceptibility. We expressed the S1 domain fused to the Fc region of human IgG, yielding a recombinant disulphide-bonded dimer of approximately 280 kDa (Supplementary Fig. 1). Highly specific binding was observed to African green monkey kidney (Vero) and human liver (Huh-7) cells by immunofluorescence and fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis, whereas kidney cells of the P. pipistrellus bat showed intermediate staining (Fig. 1). No S1 binding was detectable to COS-7 African green monkey kidney cells (Fig. 1b). Furthermore, no specific binding to any of these cells was observed with a feline coronavirus S1 domain, whereas feline cells (Felis catus whole fetus, FCWF) showed strong reactivity (Supplementary Table 1). Binding of hCoV-EMC S1 was shown to correlate with susceptibility to hCoV-EMC infection and with viral genome detection in the culture medium of infected cells (Fig. 1). The hCoV-EMC S1 domain was demonstrated also to bind to cells from other species but its overall reactivity was more restricted compared to that observed for SARS-CoV S1 (Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 1. Binding of hCoV-EMC S1 to cells is correlated with infection of hCoV-EMC.

a–d, Shown in the left panels are the FACS analyses of hCoV-EMC S1–Fc binding (red line) to Vero (a), COS-7 (b), Huh-7 (c) and bat cells (d). A feline CoV S1–Fc protein (blue line) and mock-incubated cells (grey shading) were used as controls. In the middle panels, hCoV-EMC-infected cells are visualized using an antiserum that recognizes the non-structural protein NSP4. In the right panels, hCoV-EMC RNA levels in supernatants of the infected cells at 0, 20 and 40 h after infection were quantified using a TaqMan assay and expressed as genome equivalents (GE; half-maximal tissue-culture infectious dose (TCID50) per ml). Error bars indicate s.e.m.

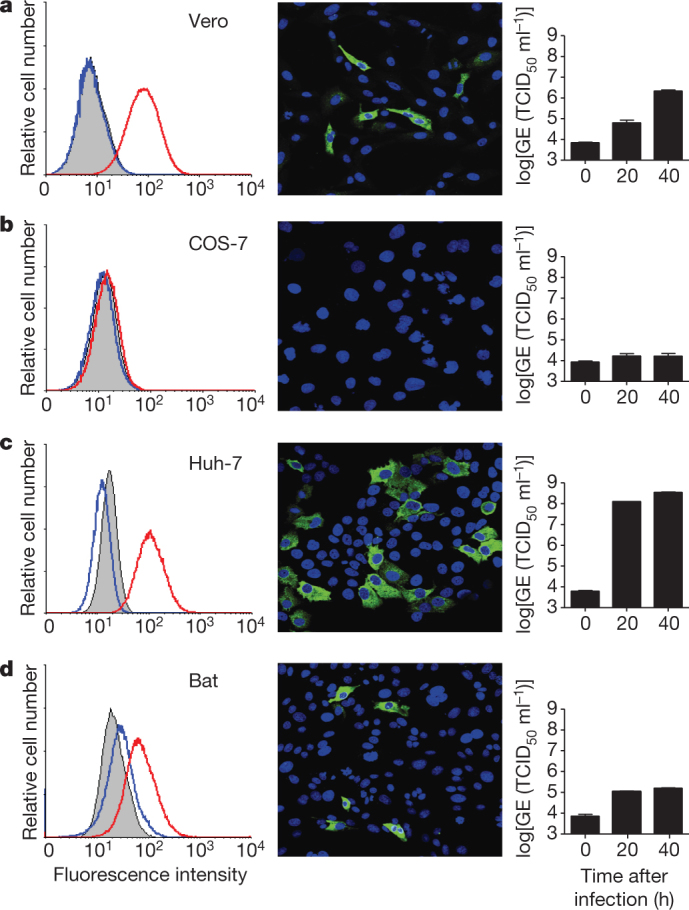

To identify the cell surface protein(s) binding to S1 we affinity-isolated proteins from Vero and Huh-7 cells using the S1–Fc chimaeric proteins. The hCoV-EMC S1–Fc protein—but not SARS-CoV S1–Fc—extracted a protein of ∼110 kDa when analysed under non-reducing conditions from Huh-7 cell lysates (Fig. 2a). Mass spectrometric analysis identified this protein as dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4 or DPP IV, also called CD26; Supplementary Fig. 2). Similar results were obtained using Vero cells (data not shown). We subsequently produced soluble (that is, non-membrane-anchored) forms of DPP4 and ACE2 and found that the hCoV-EMC S1–Fc protein bound the former but not the latter, whereas the opposite was seen with the SARS S1–Fc protein (Fig. 2b). Soluble DPP4, but not soluble ACE2, inhibited infection of Vero cells by hCoV-EMC (Supplementary Fig. 3). Moreover, transient expression of human DPP4 in the non-susceptible COS-7 cells rendered these cells susceptible to binding the hCoV-EMC S1–Fc protein to their surface (Supplementary Fig. 4). These data indicate a direct and specific binding of hCoV-EMC S1 to human DPP4.

Figure 2. hCoV-EMC S1 binding to DPP4.

a, Huh-7 cell lysates were incubated with hCoV-EMC and SARS-CoV S1–Fc proteins and affinity-isolated proteins were subjected to protein electrophoresis under non-reducing conditions. The arrowhead indicates the position of the ∼110-kDa DPP4 protein specifically isolated using the hCoV-EMC S1–Fc protein. b, hCoV-EMC and SARS-CoV S1–Fc proteins were mock-incubated or incubated with soluble DPP4 (sDPP4) or soluble ACE2 (sACE2) followed by protein A sepharose affinity isolation and subjected to protein electrophoresis under non-reducing conditions.

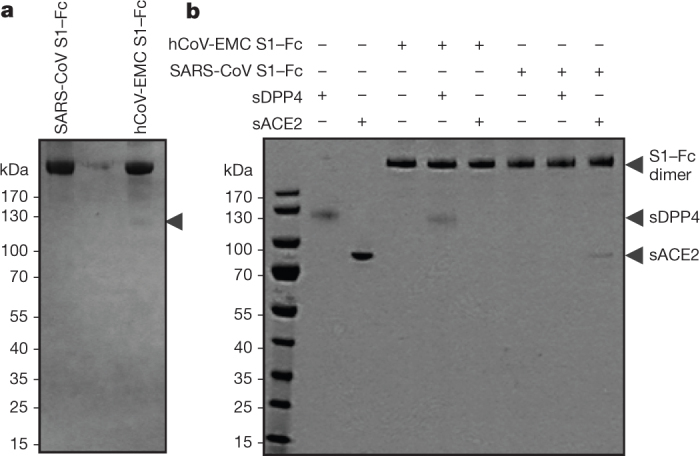

The DPP4 protein displays high amino acid sequence conservation across different species, including the sequence that we obtained from P. pipistrellus bat cells (Supplementary Fig. 5), particularly towards the carboxy-terminal end (Supplementary Fig. 6). Next, we tested surface expression of DPP4 on susceptible and non-susceptible cells using a polyclonal human DPP4 antiserum. The specific reactivity of the anti-DPP4 serum with human and bat DPP4 was demonstrated by staining of human and bat DPP4-transfected cells (Fig. 3a). Expression of bat DPP4 in COS-7 cells allowed hCoV-EMC S1–Fc cell surface binding (Fig. 3a). Consistent with their susceptibility to hCoV-EMC infection and with the hCoV-EMC S1 cell surface binding, Vero and Huh-7 cells expressed high levels of DPP4 on their surface as judged by antibody reactivity, bat cells displayed low-level antibody binding, whereas COS-7 cells did not show any significant binding (Fig. 3b). Thus, DPP4 cell surface expression on the cell lines was consistent with hCoV-EMC S1 cell surface binding and with susceptibility to hCoV-EMC infection. The relevance of these observations was enforced by the finding that DPP4 expression was also found in primary human bronchiolar epithelial cell cultures (Fig. 3c) and in human bronchial lung tissue (Fig. 3d), in both instances localized to the apical surfaces of non-ciliated (tubulin-IV negative) cells. In addition, hCoV-EMC infection of human bronchiolar epithelial cell cultures appeared to be localized to the non-ciliated cells that express DPP4 (Fig. 3e).

Figure 3. DPP4 is present on hCoV-EMC-susceptible cell lines and human bronchiolar epithelial cells.

a, COS-7 cells transfected with plasmids encoding human DPP4 (hDPP4), bat DPP4 (bDPP4) or a control plasmid (pcDNA) were tested for S1 binding and staining with a polyclonal antiserum against DPP4. b, Similarly, COS-7, Huh-7, Vero and bat cells were tested for reactivity with the same antiserum against DPP4 (blue lines) or with a control normal goat serum (grey peak). c, d, DPP4 expression (red) was also found in primary human bronchiolar epithelial cell cultures (c) and human bronchiolar tissue (d) and appeared to be localized to the apical surfaces of non-ciliated cells that do not express β-tubulin IV (green). e, Double-stranded viral RNA (cyan) was detected in hCoV-EMC-infected primary human bronchiolar epithelial cell cultures and appeared to be localized to non-ciliated cells that express DPP4 (red). Stainings were performed using antibodies directed against β-tubulin IV (ciliated cells; green), DPP4 (red), dsRNA (hCoV-EMC; cyan), and DAPI (cell nucleus; blue). All scale bars are 10 μm.

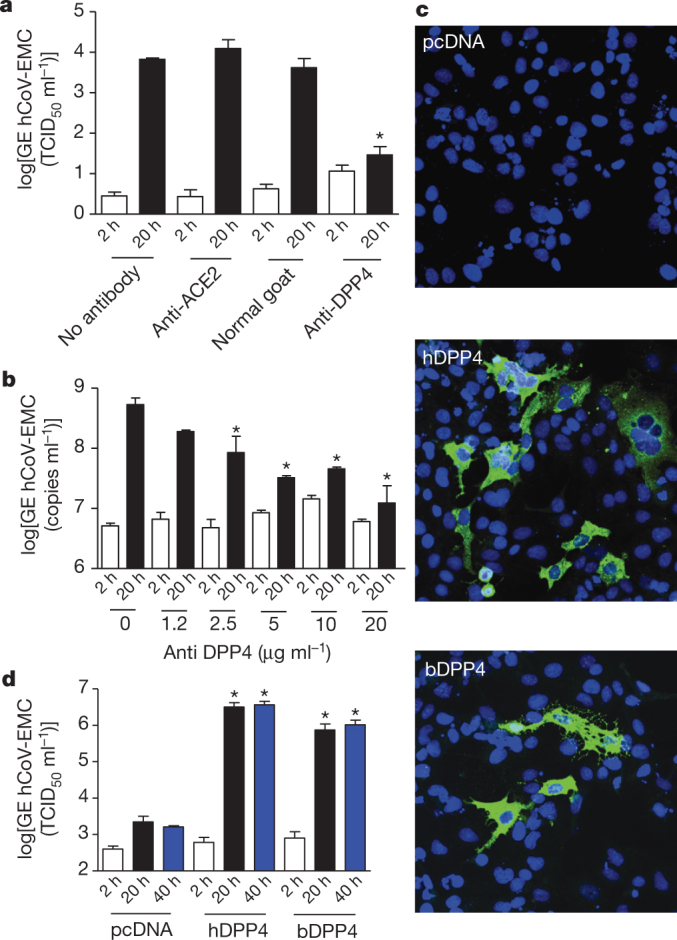

To determine whether DPP4 essentially contributes to infection, susceptible cells were pre-incubated with polyclonal DPP4 antiserum before virus inoculation. Infection of Huh-7 cells was blocked by this serum but not by control serum or ACE2 antibodies, as evidenced by a strong reduction of virus infection, of virus excretion and of virus-induced cytopathic effects (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 7). In addition, infection of primary bronchiolar epithelial cells was blocked by the DPP4 antibodies in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4b). We next examined whether DPP4 expression confers susceptibility to hCoV-EMC infection. COS-7 cells transfected with the human DPP4 expression plasmid, but not with the empty plasmid, were efficiently infected by hCoV-EMC as demonstrated by the presence of viral non-structural proteins in the cells (Fig. 4c) and of viral RNA (Fig. 4d) and infectious virus in the cell supernatants (not shown). Likewise, expression of bat DPP4 in COS-7 cells conferred susceptibility to the virus, although to a lesser extent (Fig. 4c). Transfection of human DPP4 in non-susceptible cells of different species origin (feline, murine and canine) also permitted infection with hCoV-EMC (Supplementary Fig. 8a), whereas other human coronaviruses such as hCoV-NL63, hCoV-229E and hCoV-OC43 were not able to infect human DPP4-transfected cells (Supplementary Fig. 8b–d). Collectively, our data demonstrate that DPP4 of human and bat origin acts as a functional receptor for hCoV-EMC.

Figure 4. DPP4 is essential for virus infection.

a, Inhibition of hCoV-EMC infection of Huh-7 cells by antibodies to DPP4. Supernatants collected at 2 h (open bars) and 20 h (filled bars) were tested for the presence of hCoV-EMC RNA using a TaqMan assay. Results representative of three different experiments are shown as ΔCt values (one-way ANOVA test, *P < 0.05; n = 3 per group), normal goat, normal goat serum. b, Infection of human primary bronchiolar epithelial cells is blocked by the DPP4 antibodies in a dose-dependent manner and samples were analysed at 2 h (open bars) and 20 h (filled bars) after infection (one-way ANOVA test, *P < 0.05; n = 3 per group). c, COS-7 cells transfected with plasmids encoding human DPP4 (hDPP4), bat DPP4 (bDPP4) or a control plasmid (pcDNA) were inoculated with hCoV-EMC at a multiplicity of infection of 1 and left for 1 h. Cells were washed twice and stained at 8 h after infection (original magnification, ×200) or supernatant collected at 2 h (open bars), 20 h (black bars) and 40 h (blue bars) was tested for the presence of hCoV-EMC RNA using a TaqMan assay (d). Results representative of three different experiments are expressed as GE (TCID50 ml−1) values (one-way ANOVA test, *P < 0.05; n = 4 per group). All error bars represent s.e.m.

After ACE2 and APN, DPP4 is the third exopeptidase to be discovered as a receptor for coronaviruses. DPP4 is a multifunctional 766-amino-acid-long type-II transmembrane glycoprotein presented in a dimeric form on the cell surface. It preferentially cleaves dipeptides from hormones and chemokines after a proline amino acid residue, thereby regulating their bioactivity16. Yet the use of peptidases by coronaviruses may be more related to their abundant presence on epithelial and endothelial tissues—the primary tissues of coronavirus infection—rather than to their proteolytic activity, which in the case of APN and ACE2 appeared not to be critical for infection12,13. Consistently, hCoV-EMC infection could not be blocked by the DPP4 inhibitors sitagliptin, vildagliptin, saxagliptin or P32/98 (Supplementary Fig. 9). DPP4 also has a major role in glucose metabolism by its degradation of incretins and has been further implicated in T-cell activation, chemotaxis modulation, cell adhesion, apoptosis and regulation of tumorigenicity16,17. In humans it is primarily expressed on the epithelial cells in kidney, small intestine, liver and prostate, and on activated leukocytes, whereas it occurs as a soluble form in the circulation16,17. At present little is known about the tropism of hCoV-EMC in vivo; the virus has been detected only in upper respiratory swabs, urine, sputum and tracheal aspirate3,4. Our observation of DPP4 being expressed on non-ciliated bronchial epithelial cells together with its reported expression in the kidney is consistent with clinical manifestations of hCoV-EMC infection. It is important to note that most respiratory viruses, including SARS-CoV18, have a marked tropism for ciliated cells that are more widely distributed along the upper and lower respiratory tract.

The epidemiological history of hCoV-EMC remains enigmatic. As for SARS-CoV and hCoV-NL63 (refs 7, 19), a bat origin possibly combined with the existence of an intermediate animal reservoir seems feasible. In view of the evolutionary conservation of DPP4 and the ability of hCoV-EMC to use bat DPP4 as a functional receptor, such host species switching would not be surprising. Adaptive mutations in the SARS-CoV S1 domain allowing improved binding to human ACE2 have been noted, explaining, at least in part, the zoonotic transmission event20,21. Further in-depth characterization of the binding interface of hCoV-EMC S1 and DPP4 may shed light on the possible adaptive processes of this virus or related coronaviruses using DPP4 in novel host species.

Variations in soluble DPP4 levels in serum have been reported as clinically relevant in a number of pathophysiological conditions including type-2 diabetes mellitus and virus infections16,17. It will be important to investigate whether and how varying soluble DPP4 levels affect hCoV-EMC pathogenesis. Downregulation of ACE2 expression after SARS-CoV infection has been shown to contribute to the severity of disease22, consistent with the protective role of soluble ACE2 in lung injury23. Given the importance of DPP4 in regulation of chemokine and cytokine responses16 one may speculate that in vivo downregulation of the hCoV-EMC receptor may potentially influence the pathogenesis of this virus. Preliminary findings in vitro, however, indicate that S1 binding to DPP4 did not result in significant downregulation of DPP4 or of the DPP4 enzymatic activity on Huh-7 cells (not shown), possibly due to the observed active recycling of DPP4 from the plasma membrane16. Manipulation of DPP4 levels or development of inhibitors that target the binding interface between the S1 domain and receptor in vivo may provide therapeutic opportunities to combat hCoV-EMC infection. In addition, future studies should address the development of effective vaccines, including those that elicit antibodies that prevent the binding of hCoV-EMC to DPP4.

Methods Summary

hCoV-EMC infection and detection

Virus stocks of hCoV-EMC were prepared as described earlier5. Vero, COS-7, Huh-7 and kidney cells of the P. pipistrellus bat15 were inoculated with hCoV-EMC for 1 h and incubated with medium containing 1% fetal bovine serum. Formaldehyde-fixed cells were stained using rabbit-anti-SARS-CoV NSP4 antibodies that are cross-reactive for hCoV-EMC, according to standard protocols using a FITC-conjugated swine-anti-rabbit antibody as a second step. Viral replication was quantified by quantitative PCR as described in Methods.

Protein expression

S1 receptor-binding domains of hCoV-EMC, SARS-CoV and FIPV fused to the Fc region of human IgG, and soluble versions of DPP4 and ACE2 were expressed and purified as described in the Methods.

DPP4 cell surface expression measurement using S1–Fc proteins

S1 binding of cells was measured by incubating 2.5 × 105 cells with 15 μg ml−1 of S1–Fc followed by incubation with FITC or DyLight-488-labelled goat-anti-human IgG antibody and analysis by flow cytometry.

Online Methods

Protein expression

A plasmid encoding hCoV-EMC S1–Fc was generated by ligating a fragment encoding the S1 domain (residues 1–747) 3′ terminally to a fragment encoding the Fc domain of human IgG into the pCAGGS expression vector. Likewise, an S1–Fc expression plasmid was made for the SARS-CoV domain S1 subunit (isolate CUHK-W1; residues 1–676), the FIPV S1 domain (isolate 79–1146; residues 1–788) and the human ACE2 ectodomain (sACE2; residues 1–614). Fc chimaeric proteins were expressed by transfection of the expression plasmids into HEK-293T cells and affinity purified from the culture supernatant using protein A sepharose beads (GE Healthcare). Purified ACE2–Fc was cleaved with thrombin and soluble ACE2 was purified by gel-filtration chromatography. A DPP4 expression vector was generated by cloning the full-length human DPP4 gene into the pCAGGS or the pcDNA3 vector. A plasmid encoding the ectodomain of human DPP4 was generated by ligating a fragment encoding residues 39–766 of human DPP4 into a pCD5 expression vector24 encoding the signal sequence of CD5 and an OneSTrEP affinity tag (IBA GmbH). Soluble DPP4 ectodomain was prepared by transfection of the expression plasmid into HEK-293T cells and affinity purification from the culture supernatant using Strep-Tactin sepharose beads (IBA GmbH). S1 binding of cells was measured by incubating 2.5 × 105 cells with 15 μg ml−1 of S1–Fc followed by incubation with FITC or DyLight-488-labelled goat-anti-human IgG antibody and analysis by flow cytometry.

Affinity-purification and detection of DPP4

Huh-7 cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS, scraped off the plastic with a rubber policeman, pelleted and lysed in ice-cold lysis buffer (0.3% n-decyl-β-d-maltopyranoside in PBS) containing protease inhibitors (Roche Complete Mini and phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride) at a final density of ∼2.5 × 107 cells ml−1. The supernatants of centrifuged cell lysates were precleared with protein A sepharose beads after which 10 μg of S1–Fc and 100 μl protein A sepharose beads (50% v/v) was added to 1 ml of cell lysate and incubated for 1 h at 4 °C under rotation. Beads were washed thrice with lysis buffer and once with PBS and subjected to protein electrophoresis (NoVEX 4–12% Tris-glycine gradient gel, Invitrogen) under non-reducing conditions. A distinct ∼110-kDa protein co-purified with hCoV-EMC S1–Fc was visualized by GelCodeBlue staining, excised from the gel, incubated with trypsin and analysed by mass spectrometry.

Mass spectrometry and data analysis

The distinct ∼110-kDa protein which co-purified with hCoV-EMC S1–Fc was excised from the gel and subjected to in-gel reduction with dithiothreitol, alkylation with chloroacetamide and digestion with trypsin (Promega, sequencing grade), essentially as described25. Alternatively, affinity-isolated proteins were reduced and alkylated on beads similarly as described above. Nanoflow LC-MS/MS was performed on either an 1100 series capillary LC system (Agilent Technologies) coupled to an LTQ-Orbitrap XL mass spectrometer (Thermo), or an EASY-nLC coupled to a Q Exactive mass spectrometer (Thermo), operating in positive mode and equipped with a nanospray source. Peptide mixtures were trapped on a ReproSil C18 reversed-phase column (Dr Maisch GmbH; column dimensions 1.5 cm × 100 µm, packed in-house) at a flow rate of 8 µl min−1. Peptide separation was performed on ReproSil C18 reversed-phase column (Dr Maisch GmbH; column dimensions 15 cm × 50 μm, packed in-house) using a linear gradient from 0% to 80% B (A = 0.1% formic acid; B = 80% (v/v) acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid) in 70 or 120 min and at a constant flow rate of 200 nl min−1. The column eluent was directly sprayed into the ESI source of the mass spectrometer. Mass spectra were acquired in continuum mode; fragmentation of the peptides was performed in data-dependent mode by CID or HCD. Peak lists were automatically created from raw data files using the Mascot Distiller software (version 2.3; MatrixScience) or Proteome Discoverer (version 1.3; Thermo). The Mascot algorithm (version 2.2; MatrixScience) was used for searching against a Uniprot database (release 2012_10.fasta, taxonomy: Homo sapiens or Chlorocebus sabaeus). The peptide tolerance was set to 10 p.p.m. and the fragment ion tolerance was set to 0.8 Da for CID spectra (LTQ-Orbitrap) or to 20 milli unified atomic mass unit (mu) for HCD (Q Exactive) spectra. A maximum number of two missed cleavages by trypsin were allowed and carbamidomethylated cysteine and oxidized methionine were set as fixed and variable modifications, respectively.

Blocking of hCoV-EMC replication by DPP4 antiserum

Huh-7 and primary airway epithelial cells (triplicates of one donor) were pre-incubated with antibodies to DPP4 (polyclonal goat-anti DPP4 immunoglobulin, R&D systems) in a range of 0–20 µg ml−1. Cells were infected with hCoV-EMC, incubated for 1 h at 37 °C, washed and subsequently incubated with medium containing the respective antibody concentrations. Supernatants were collected at 2 h and 20 h and were analysed for the presence of hCoV-EMC RNA using a real-time Taqman assay.

Human bronchial epithelial cultures and confocal microscopy analysis

Human bronchial lung tissue was obtained from patients (age >18 years old) who underwent surgical lung resection in their diagnostic pathway for any pulmonary disease and that gave informed consent. This was done in accordance with local regulation of the Kantonal Hospital St Gallen, Switzerland, as part of the St Gallen Lung Biopsy Biobank (SGLBB) which received approval by the ethics committee of the Kanton St Gallen (EKSG 11/044, 27 April 2011; and EKSG 11/103, 23 September 2011).

Primary human bronchial epithelial cultures were generated as previously described26. Human bronchial epithelial cultures were maintained for 1–2 months until pseudostratified and fully differentiated epithelia were obtained. Human bronchial tissue or human bronchial epithelial cultures were fixed with 4% PFA (FormaFix) for 30 min at room temperature. The fixed human bronchial tissue or cultures were mounted in Tissue-Tek OCT medium and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, from which 10 µm horizontal sections were made. The cryosections were immunostained using the procedure as described26, using mouse monoclonal antibody anti-β-tubulin IV (Sigma) and goat anti-hDPP4 polyclonal antibody (R&D Systems) as primary antibodies, and Dylight-488-labelled, anti-mouse IgG (H+L) and Dylight-549-labelled, anti-goat IgG (H+L) as secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch). Counterstaining was done with DAPI (Invitrogen). Fluorescent images were acquired using Plan Apochromat 63×/1.40 oil DIC M27 or EC Plan-Neofluor 40×/1.30 oil DIC M27 objectives on a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope. Image capture, analysis and processing were performed using the ZEN 2010 (Zeiss) software packages.

hCoV-EMC-infected human bronchial epithelial cultures were fixed with 4% PFA (FormaFix) for 30 min at room temperature. Fixed cultures were immunostained using the procedure as described26, with mouse monoclonal antibody anti-dsRNA (J2, English and Scientific Consulting Bt.) and goat anti-hDPP4 polyclonal antibody (R&D Systems) as primary antibodies, and Dylight-488-labelled, anti-mouse IgG (H+L) and Dylight-549-labelled, anti-goat IgG (H+L) as secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch). The rabbit monoclonal anti-β-tubulin conjugated with Alexafluor 647 (9F3, Cell Signaling) was applied as tertiary antibody. Counterstaining was done with DAPI (Invitrogen). Z-stack images were acquired using a Plan Apochromat 63×/1.40 oil DIC M27 objective on a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope from which a three-dimensional reconstruction was made using maximum intensity projection. Image capture, analysis and processing were performed using the ZEN 2010 (Zeiss) and Imaris (Bitplane Scientific Software) software packages.

DPP4 enzymatic activity

DPP4 activity was measured on live cells using DPPIV/CD26 Assay kit for Biological Samples (Enzo Life sciences). Briefly, Vero cells (1 × 104 cells well−1) were grown in 96-well plates, washed twice with PBS, incubated with or without inhibitor (20 µg ml−1) for 10 min after which H-Gly-Pro-AMC substrate was added and incubated for 10 min. Fluorescence intensity was measured at 380/460 nm using Tecan Infinite F200.

Cloning and expression of human and bat DPP4

Total RNA was isolated from Huh-7 and PipNi/1 cells using RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen) and cDNAs were synthesized by using the Superscript reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies). The complete DPP4 genes were amplified using Pfu Ultra II fusion HS DNA polymerase (Stratagene) and cloned into the pcDNA 3.1 (+) expression vector (Life Technologies). After sequencing, alignment was performed using ClustalW in the MEGA 5.0 software package (http://www.megasoftware.net) and the trees were constructed by using the neighbour-joining method with p-distance (gap/missing data treatment; complete deletion) and 1,000 bootstrap replicates as in MEGA 5.0. pcDNA plasmids containing the human or bat DPP4 or the empty pcDNA plasmid were transfected into COS-7 cells using lipofectamine 2000 (Life technologies). After 24 h incubation, cells were stained with both goat-anti-human DPP4 polyclonal antibody (R&D system) and a rabbit anti-goat IgG–FITC antibody (Sigma).

Virus infection, RNA extraction and quantitative RT–PCR

Virus stocks of hCoV-EMC were prepared as described previously5. Vero, COS-7, Huh-7 and kidney cells of the P. pipistrellus bat cells15 were inoculated with hCoV-EMC for 1 h and incubated with medium containing 1% fetal bovine serum. Formaldehyde-fixed cells were stained using rabbit-anti-SARS-CoV NSP4 antibodies that are cross-reactive for hCoV-EMC, according to standard protocols using a FITC-conjugated swine-anti-rabbit antibody as a second step. RNA from 200 μl of culture supernatant was isolated with the Magnapure LC total nucleic acid isolation kit (Roche) and eluted in 100 μl. hCoV-EMC RNA was quantified on the ABI prism 7700, with the TaqMan Fast Virus 1-Step Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) using 20 μl isolated RNA, 1× Taqman mix, 0.5 U uracil-N-glycosylase, 45 pmol forward primer (5′-GGGTGTACCTCTTAATGCCAATTC-3′), 45 pmol reverse primer (5′-TCTGTCCTGTCTCCGCCAAT-3′) and 5 pmol probe (5′-FAM-ACCCCTGCGCAAAATGCTGGG-BHQ1-3′) . Amplification parameters were 5 min at 50 °C, 20 s at 95 °C, and 45 cycles of 3 s at 95 °C, and 30 s at 60 °C. RNA dilutions isolated from an hCoV-EMC stock were used as a standard. hCoV-NL63, hCoV-229E and hCoV-OC43 quantitative PCRs were routinely performed at the diagnostics Department of Viroscience at the Erasmus MC Rotterdam.

Statistics

We compared the mean Ct values and log GE hCoV-EMC using one-way ANOVA with post-test Bonferroni. Statistical analysis was performed with Prism 4.0 (Graphpad).

Supplementary information

This file contains Supplementary Figures 1-9 and Supplementary Table 1. (PDF 783 kb)

Acknowledgements

We thank E. Snijder for providing the anti-SARS-CoV NSP4 antibody, and E. Kindler, H. Jónsdóttir, R. Rodriguez, T. Bestebroer, S. Pas, G. Arron, M. van Velzen and W. Ouwendijk for technical assistance. This work was supported by a fellowship from China Scholarship Council to H.M. The study was financed by the European Union FP7 project EMPERIE (contract number 223498), ANTIGONE (contract number 278976), the Swiss National Science Foundation (31003A_132898) and the 3R Research Foundation Switzerland (Project 128-11). C.D. was supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG grant DR 772/3-1, KA1241/18-1) and the German Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF SARS II).

PowerPoint slides

Author Contributions

B.J.B., V.S.R. and B.L.H. designed and coordinated the study. B.J.B. and B.L.H. contributed equally to the study. V.S.R., H.M., S.L.S., D.H.W.D., M.A.M., R.D., D.M., B.J.B. and B.L.H conducted the experiments. A.Z. provided the virus, and R.A.M.F., J.A.A.D., V.T., C.D., A.D.M.E.O. and P.J.M.R. supervised part of the experiments. All authors contributed to the interpretations and conclusions presented. B.J.B. and B.L.H. wrote the manuscript, and A.D.M.E.O. and P.J.M.R. participated in editing it.

Accession codes

Primary accessions

GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ

Data deposits

The P. pipistrellus bat DPP4 sequence has been deposited in GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ under accession number KC249974.

Competing interests

V.S.R., B.J.B., R.A.M.F., A.D.M.E.O. and B.L.H. are inventors on a patent application related to this work.

Footnotes

V. Stalin Raj and Huihui Mou: These authors contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Berend Jan Bosch, Email: b.j.bosch@uu.nl.

Bart L. Haagmans, Email: b.haagmans@erasmusmc.nl

References

- 1.Weiss SR, Navas-Martin S. Coronavirus pathogenesis and the emerging pathogen severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2005;69:635–664. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.69.4.635-664.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peiris JSM, Guan Y, Yuen KY. Severe acute respiratory syndrome. Nature Med. 2004;10:S88–S97. doi: 10.1038/nm1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zaki AM, van Boheemen S, Bestebroer TM, Osterhaus AD, Fouchier RA. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;367:1814–1820. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bermingham A, et al. Severe respiratory illness caused by a novel coronavirus, in a patient transferred to the United Kingdom from the Middle East, September 2012. Euro Surveill. 2012;17:20290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Boheemen S, et al. Genomic characterization of a newly discovered coronavirus associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome in humans. mBio. 2012;3:e00473–12. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00473-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Graham RL, Baric RS. Recombination, reservoirs, and the modular spike: mechanisms of coronavirus cross-species transmission. J. Virol. 2010;84:3134–3146. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01394-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li W, et al. Bats are natural reservoirs of SARS-like coronaviruses. Science. 2005;310:676–679. doi: 10.1126/science.1118391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organisation Interim surveillance recommendations for human infection with novel coronavirus. http://www.who.int/csr/don/2013_02_21/en/index.html (21 February 2013)

- 9.Drexler JF, et al. Genomic characterization of severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus in European bats and classification of coronaviruses based on partial RNA-dependent RNA polymerase gene sequences. J. Virol. 2010;84:11336–11349. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00650-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams RK, Jiang GS, Holmes KV. Receptor for mouse hepatitis virus is a member of the carcinoembryonic antigen family of glycoproteins. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1991;88:5533–5536. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.13.5533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yeager CL, et al. Human aminopeptidase N is a receptor for human coronavirus 229E. Nature. 1992;357:420–422. doi: 10.1038/357420a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delmas B, et al. Aminopeptidase N is a major receptor for the entero-pathogenic coronavirus TGEV. Nature. 1992;357:417–420. doi: 10.1038/357417a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li W, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature. 2003;426:450–454. doi: 10.1038/nature02145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schultze B, Herrler G. Bovine coronavirus uses N-acetyl-9-O-acetylneuraminic acid as a receptor determinant to initiate the infection of cultured cells. J. Gen. Virol. 1992;73:901–906. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-4-901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Müller MA, et al. Human coronavirus EMC does not require the SARS-coronavirus receptor and maintains broad replicative capability in mammalian cell lines. mBio. 2012;3:e00515–12. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00515-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lambeir AM, Durinx C, Scharpe S, De Meester I. Dipeptidyl-peptidase IV from bench to bedside: an update on structural properties, functions, and clinical aspects of the enzyme DPP IV. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2003;40:209–294. doi: 10.1080/713609354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boonacker E, Van Noorden CJ. The multifunctional or moonlighting protein CD26/DPPIV. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2003;82:53–73. doi: 10.1078/0171-9335-00302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sims AC, Burkett SE, Yount B, Pickles RJ. SARS-CoV replication and pathogenesis in an in vitro model of the human conducting airway epithelium. Virus Res. 2008;133:33–44. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huynh J, et al. Evidence supporting a zoonotic origin of human coronavirus strain NL63. J. Virol. 2012;86:12816–12825. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00906-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu K, Peng G, Wilken M, Geraghty RJ, Li F. Mechanisms of host receptor adaptation by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:8904–8911. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.325803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li F, Li W, Farzan M, Harrison SC. Structure of SARS coronavirus spike receptor-binding domain complexed with receptor. Science. 2005;309:1864–1868. doi: 10.1126/science.1116480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuba K, et al. A crucial role of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in SARS coronavirus-induced lung injury. Nature Med. 2005;11:875–879. doi: 10.1038/nm1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Imai Y, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 protects from severe acute lung failure. Nature. 2005;436:112–116. doi: 10.1038/nature03712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bosch BJ, et al. Recombinant soluble, multimeric HA and NA exhibit distinctive types of protection against pandemic swine-origin 2009 A(H1N1) influenza virus infection in ferrets. J. Virol. 2010;84:10366–10374. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01035-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van den Berg DL, et al. An Oct4-centered protein interaction network in embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6:369–381. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dijkman, R. et al. Isolation and characterization of current human coronavirus strains in primary human epithelia cultures reveals differences in target cell tropism. J. Virol.10.1128/JVI.03368-12 (2013) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

This file contains Supplementary Figures 1-9 and Supplementary Table 1. (PDF 783 kb)

Data Availability Statement

Primary accessions

GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ

Data deposits

The P. pipistrellus bat DPP4 sequence has been deposited in GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ under accession number KC249974.