In Thailand, hotels are requiring visitors from certain countries to check in at separate counters. In India, airline pilots are refusing to fly to some parts of the world. In Singapore, thousands of people must stay home and appear in front of government-installed cameras at random times, and the Roman Catholic Church there has banned confessions until further notice.

This is just a small sampling of responses to the threat of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). As of 14 April, the disease, which originated in the Guangdong province of China, had claimed the lives of 122 people in seven nations and infected more than 3,000 others. The leading hypothesis is that the flu-like illness is caused by a new strain of coronavirus.

Since the World Health Organization sounded the alarm about SARS in March, universities, international companies and governments are recalling people from Hong Kong, major airlines have canceled flights to the region and the WHO has released an unprecedented travel advisory.

Governments across the world have also been struggling to find ways to defend against the disease and many have invoked long-dormant quarantine laws. Several nations, including Vietnam, Malaysia, Taiwan, New Zealand and Australia, are either barring visitors from SARS-affected nations or are requiring them to wear masks for 10 days under threat of hefty fines. In Hong Kong and Singapore, the governments have placed thousands of people under forced quarantine.

“It's totally predictable—those are the kinds of things that are going to occur,” says Joseph Barbera, co-director for the Institute for Crisis, Disaster and Risk Management at George Washington University. But such measures, Barbera says, are bound to fail. “When you look carefully at quarantine history, it was always a failure,” Barbera says. “The objective is to contain disease, not to contain human beings.”

Life as usual—almost: residents of Hong Kong go about their daily business wearing masks to protect against SARS.

(AP photo/Anat Givon)

At best, quarantine can delay the spread of a disease and buy time, says Barbera. Even then, he adds, governments must be rational and provide workers' compensation or workers' insurance to those in quarantine and, most important, educate the public on how best to protect themselves.

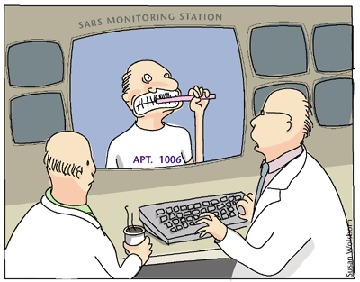

WE'RE CALLING IT "REAL WORLD SINGAPORE"

For many nations, this is the first quarantine experience in decades. In the US, for example, the last mass quarantine was during the 1918–19 Spanish flu epidemic, when the government closed down schools, shops and church services, interrupted train and ship routes and began placing people in quarantine camps. The global response to SARS, 85 years later, has not been much different. “We will do, in this country, whatever is necessary to contain the spread of the epidemic,” said Anthony Fauci, head of the US National Institute of AIDS and Infectious Diseases. “If that's quarantine, so be it.”

Isolation of infected individuals is standard procedure in treating infectious diseases such as tuberculosis. Quarantine, on the other hand, applies to people who have been exposed to the disease but may not yet be ill. Separating exposed people and restricting their movements is intended to stop the spread of that illness—but it doesn't, says Lisa Sattenspiel, associate professor of anthropology at the University of Missouri. “Isolation at least does something,” she says. “Quarantine is much, much less effective.”

Although experts have maintained for hundreds of years that quarantine doesn't work, governments intuitively turn to it because it keeps people from moving around, Sattenspiel says. But what they don't realize, she adds, is the level of compliance required for it to succeed.

Sattenspiel has constructed mathematical models of quarantine based on simulations of the 1918 flu epidemic. “If you're really able to limit everybody and keep all those people from moving, it does work,” she says. “It's just that you never have a perfect quarantine because you're trying to convince perfectly healthy people to stay put. There's always going to be people who find a way around it.”

In Hong Kong, for example, authorities first used barricades and tape to seal people inside Amoy Gardens apartment building, which produced several hundred of the city's SARS cases, then placed them in quarantine camps. But when police arrived at the building, residents of more than half the apartments were missing and still remain at large.

The Singapore government enforced large-scale quarantines soon after the disease first struck and hired a security company to place electronic cameras at the homes of those under quarantine. It also began issuing electronic wrist tags to monitor the movements of quarantine violators. In spite of those measures, Singapore's numbers rose on 14 April to 147 cases, the third highest in Asia.

That may partly be because of the high ratio of 'superspreaders' or hypertransmitters of SARS, some experts say. But others warn that the harsh environment may drive people to seek alternative medicines and steer clear of hospitals for fear of being taken from their families. Still, “if you have 20 [exposed] people and only 10 in quarantine, that's better than none in quarantine,” says Fauci. “That's what's called a common-sense mathematical model.”