Abstract

Excessive body iron or iron overload occurs under conditions such as primary (hereditary) hemochromatosis and secondary iron overload (hemosiderosis), which are reaching epidemic levels worldwide. Primary hemochromatosis is the most common genetic disorder with an allele frequency greater than 10% in individuals of European ancestry, while hemosiderosis is less common but associated with a much higher morbidity and mortality. Iron overload leads to iron deposition in many tissues especially the liver, brain, heart and endocrine tissues. Elevated cardiac iron leads to diastolic dysfunction, arrhythmias and dilated cardiomyopathy, and is the primary determinant of survival in patients with secondary iron overload as well as a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in primary hemochromatosis patients. In addition, iron-induced cardiac injury plays a role in acute iron toxicosis (iron poisoning), myocardial ischemia–reperfusion injury, Friedreich ataxia and neurodegenerative diseases. Patients with iron overload also routinely suffer from a range of endocrinopathies, including diabetes mellitus and anterior pituitary dysfunction. Despite clear connections between elevated iron and clinical disease, iron transport remains poorly understood. While low-capacity divalent metal and transferrin-bound transporters are critical under normal physiological conditions, L-type Ca2+ channels (LTCC) are high-capacity pathways of ferrous iron (Fe2+) uptake into cardiomyocytes especially under iron overload conditions. Fe2+ uptake through L-type Ca2+ channels may also be crucial in other excitable cells such as pancreatic beta cells, anterior pituitary cells and neurons. Consequently, LTCC blockers represent a potential new therapy to reduce the toxic effects of excess iron.

Keywords: Hemochromatosis, Iron, L-type Ca2+ channels, Cardiomyopathy, Endocrinopathy, Oxidative stress

Introduction

Iron is a transition metal that is essential for many biochemical, metabolic and biological processes. Iron is a component of hemoglobin, myoglobin, mitochondrial electron transport chain enzymes, cytochrome p450 system and many other proteins [1–3]. The biological importance of iron, as well as its toxicity, results from rapid oxidation–reduction cycling between ferric (Fe3+) and ferrous (Fe2+) states at physiological temperatures. Consequently, iron levels are precisely regulated under normal physiological conditions [1, 2] via several intricate feedback mechanisms involving transporters, iron-binding proteins and receptors (Fig. 1) [2]. Under several clinical conditions including primary hemochromatosis and secondary iron overload, iron metabolism is perturbed, which, combined with modifying environmental factors, leads to increased morbidity and mortality [4–7]. As a result of reductions in childhood mortality and increased use of blood transfusions, disease caused by iron overload is rapidly increasing in worldwide prevalence [4–7].

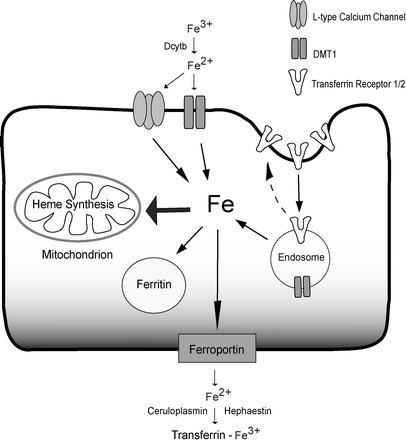

Fig. 1.

Cellular iron transporters and enzymes involved in iron uptake and export and the redox cycling of iron. DMT1 divalent metal transporter 1. Dcytb is a ferri-reductase, while ceruloplasmin and hephaestin are ferro-oxidases; broken arrow refers to the recycling of transferrin receptors

Under iron-overload conditions, iron in the circulation typically exceeds the capacity of iron binding by serum transferrin, leading to the appearance of highly reactive, non-transferrin-bound iron (NTBI) [8–10]. Uptake of NTBI into cells bypasses the normal negative-feedback mechanisms regulating cellular iron uptake and metabolism [2, 9–14]. Excess uptake of NTBI combined with the lack of an effective iron excretory pathway leads to the expansion of the labile intracellular iron pool (LIP) as well as the formation of highly reactive oxygen free radicals, causing peroxidation of membrane lipids and oxidative damage to cellular proteins [1, 2, 15]. Iron-mediated cellular damage plays a key pathophysiological role in multiple disorders including acute iron toxicosis [16, 17], iron-overload cardiomyopathy [18, 19], Friedreich-ataxia-associated cardiomyopathy [20], iron-overload endocrinopathies [21–24] and bone disease [25–27], myocardial ischemia–reperfusion injury [28, 29], atherosclerosis [30, 31] and neurodegenerative diseases [32, 33]. In this review, we will discuss the clinical disorders associated with iron overload, as well as the role of L-type Ca2+ channels (LTCC) in iron transport and pathophysiology of iron-overload cardiomyopathy and endocrinopathy.

Iron-overload conditions

Primary hemochromatosis

Primary hemochromatosis (hereditary or idiopathic) is a common inherited disorder that presents as four distinct subtypes (see Table 1) [1, 7]. In this condition, excessive iron accumulation results primarily from increased gastrointestinal absorption of iron that coupled with modifying environmental factors leads to iron overload [1, 2, 7]. Type 1 primary hemochromatosis (classic hereditary hemochromatosis) is an autosomal recessive disorder linked to mutations of the HFE gene that is involved in controlling gastrointestinal absorption of iron. Mutations of HFE genes involve either tyrosine for cysteine substitutions at position 282 (C282Y) [1, 7] or substitution of aspartate for histidine at position 63 (H63D) [1, 7]. The C282Y mutation is primarily limited to individuals of northern European ancestry and has an allele frequency of about 10%, while the H63D mutation occurs at allele frequencies greater than 5% in Mediterranean/Middle East regions and the Indian subcontinent [34]. There is a low and variable penetrance of the C282Y mutation with 0.5–1% of homozygotes developing frank clinical hemochromatosis [1, 7, 35]. Clinical effects of H63D mutations are generally limited to 1–2% of persons with compound heterozygosity for C282Y and H63D [7, 34].

Table 1.

Primary hemochromatosis and secondary iron overload

| Inheritance | Iron deposition | Molecular/cellular correlates | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary hemochromatosis type 1 | AR1 | Liver, heart, endocrine glands | HFE (HFE) 282C → Y; 63H → D | [7, 168, 169] |

| Primary hemochromatosis type 2 (JH) | AR | Liver, heart, endocrine glands | HJV (hemojuvelin); subtype A HAMP (hepcidin); subtype B | [7, 36, 170] |

| Primary hemochromatosis type 3 | AR | Liver, heart, endocrine glands | TfR2 (TFR2) | [7, 171, 172] |

| Primary hemochromatosis type 4 | AD | Macrophages2, liver, heart, endocrine glands | SLC40A1 (ferroportin) | [7, 173, 174] |

| Secondary iron overload | ||||

| α-Thalassemia, β-thalassemia | AR AD3 | Heart, pancreas, pituitary gland, liver | ↓ Synthesis of â globin (minor, intermedia and major) | [5, 175, 176] |

| SCA | AR AD4 | Liver, heart | Glu β Val (β-globin gene) | [177, 178] |

| Sideroblastic anemia5 | X-linked AR AD | Neurons, heart, mitochondria6 | ↓ Synthesis of heme | [179, 180] |

| CDA | AR (types I, II) AD (type III) | Liver, heart, endocrine | Ineffective erythropoiesis | [181] |

| CRF | Acquired (polygenic) | – | Oral and intravenous iron supplementation | [49, 50, 51, 182] |

Gene is italicized with gene product in parenthesis. ↓ indicates a reduction

AR Autosomal recessive, AD autosomal dominant, HFE gene encoding for an atypical member of the class I major histocompatibility protein family that heterodimerizes with â2-microglobulin, JH juvenile hemochromatosis, SCA sickle cell disease, aCDA congenital dyserythropoesis anemia, CRF chronic renal failure

1Variable penetrance

2Early iron accumulation occurs in macrophages/monocytes

3Dominantly inherited form of β-thalassemia resulting from a mutation in exon 3 of the β-globin gene

4Hemoglobin S Antilles, because of its low oxygen affinity, causes pathologic changes in heterozygotes

5Includes both acquired and hereditary forms

6Iron accumulates mainly in the erythroblast mitochondria

Type 2 primary hemochromatosis is also called juvenile hemochromatosis and shows an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern. Patients with this disorder generally present at younger ages with larger iron burdens and severe organ damage before age 30 years (Table 1) [7, 36]. Most patients with juvenile hemochromatosis have mutations in the HJV gene (formerly called HFE2) that encodes for hemojuvelin, a protein with a central role in iron metabolism (see below) [7, 36]. A rarer form of juvenile hemochromatosis is caused by inactivation of hepcidin, another key regulator of iron homeostasis whose expression is modulated by hemojuvelin (Table 1) [7]. Type 3 primary hemochromatosis is another autosomal recessive condition that is linked to mutations in the transferrin receptor, TfR2 [7, 37]. In contrast to the other types of hemochromatosis, type 4 primary hemochromatosis is inherited in an autosomal-dominant manner and is linked to altered function of the iron exporter ferroportin, as discussed below (Table 1 and Fig. 1) [7, 38, 39]. Next to mutations in HFE, mutations in ferroportin are the most common cause of hemochromatosis [7, 38, 39].

In addition to inherited hemochromatosis, high dietary iron intake is also implicated in iron overload of sub-Saharan Africans, although a genetic component for this disease has also been implicated [40]. The presence of high serum ferritin (<200 μg/l) and normal transferrin saturation [41] is associated with NTBI and possible excess myocardial iron accumulation in some men without known genetic defects in iron metabolism.

Secondary iron overload

Unlike primary hemochromatosis that generally involves mutations in proteins involved in iron transport and metabolism, secondary iron overload occurs in patients with hereditary anemias including α-thalassemia [42], β-thalassemia [5] and sickle cell anemia [43]. In these patients, excessive iron exposure and secondary iron overload ensue primarily because of repeated blood transfusions coupled with increased gastrointestinal iron absorption in the setting of ineffective erythropoiesis [1, 2, 5, 44]. A reduction in childhood mortality (due to infection and malnutrition) combined with increased use of chronic blood transfusions has led to a growing incidence of iron overload in patients with hereditary anemia [4, 6, 43, 45]. α- and β-thalassemias are caused by mutations resulting in defective synthesis of the α- and β-globin chains of hemoglobin, respectively, and are the most common monogenetic diseases in humans (Table 1) [5, 6, 42]. Patients with thalassemia originate primarily from the Mediterranean regions, the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia, where the estimated gene frequency is typically 3–10% but can be as high as 30–40% within certain subpopulations [5, 6, 42]. The clinical manifestations of thalassemia range from the silent carriers to severe iron overload. Sickle cell anemia is the most common and severe form of sickle cell disease (SCD) caused by homozygous presence of a glutamate to valine mutation in the beta-globulin gene (Hgb S) (Table 1). Sickle cell anemia occurs most commonly in individuals of African ancestry, and in the United States, 9% of African Americans carry the sickle cell trait and one in 600 has sickle cell anemia [46, 47].

In addition to thalassemia and SCD, several other clinical disorders are associated with secondary iron overload including sideroblastic anemia, myelodysplastic syndrome, acute myeloid leukemia, congenital dyserythropoietic anemia and chronic renal failure (Table 1). Sideroblastic anemia is characterized by mitochondrial iron overload in erythroblast and is associated with systemic iron overload, suggesting an important role for mitochondria in cellular iron metabolism (Table 1) [44, 48]. In patients with chronic renal failure and end-stage kidney disease, anemia is common due in part to erythropoietin deficiency that often necessitates therapy with intravenous iron [49–51]. A growing recognition of the toxicity of excess iron levels has increased concerns regarding the use of parenteral iron [49] in treating these patients [50, 51].

Acute iron poisoning

Acute iron toxicosis is a common cause of pediatric drug-overdose mortality [52–54]. Acute iron poisoning in these patients leads to gastrointestinal, liver and myocardial injury coupled with microvascular dysfunction, and shock [52–54]. Mortality observed with acute iron toxicity is linked to cardiovascular effects that include impaired myocardial contractility, bradycardia and hypotension, as discussed further below [16, 17].

Iron metabolism and transport

Transport of iron

The human body uses about 20 mg of iron per day for hemoglobin synthesis and the production of approximately 200 billion erythrocytes [1, 2]. Consequently, most of the iron in the body is contained in hemoglobin. An additional 4–5 mg of iron is utilized daily for the production of other cellular proteins such as mitochondrial proteins, muscle myoglobin and others. A significant amount of iron is also stored at relatively high levels in hepatocytes and macrophages of the reticulo-endothelial system. Hepatocytes extract dietary iron delivered from the intestines, while reticulo-endothelial macrophages recycle iron from ingested senescent red blood cells. Once in the body, iron is delivered to most cells of the body via the blood as ferric iron bound to the abundant serum protein transferrin (i.e. diferric-transferrin). Despite large daily iron fluxes within the body, the total iron content in normal individuals is relatively fixed, with men (50 mg Fe/kg) having slightly higher iron levels than women (40 mg/kg).

Movement of iron within the body is mediated by a combination of transporters whose activity is complexly regulated and modulated by various factors [2]. The best described “traditional” transporters include dimetal transporter 1 (DMT1), transferrin receptors (TfR1 and TfR2), ferroportin and the putative “heme receptor”. Our recent studies have established that iron can also be transported in excitable cells like cardiomyocytes by voltage-dependent L-type Ca2+ channels, which are promiscuous divalent transporters. Generally, iron transport involves redox cycling between ferrous (Fe2+) and ferric (Fe3+) states (Fig. 1 and Table 2) that are catalyzed by several ferric reductases such as duodenal-cytochrome b (Dcytb) as well as ferroxidases such as ceruloplasmin and hephaestin (Fig. 1) [2, 7]. Both ceruloplasmin and hephaestin are multi-copper-containing ferroxidases that are present in the serum and as a transmembrane protein in the basolateral surface of the duodenum, respectively, and are necessary for iron egress from intestinal enterocytes into the circulation and binding to transferrin [2, 55].

Table 2.

Expression and regulation of iron transporters

| Expression | Permeant/bound Fe species | IRE present | IO/ID | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transferrin (and TfR) | Blood | Fe3+ | Yes | ↓/↑ | [2] |

| DMT1 | Gut, kidney, heart | Fe2+ | Yes | ↓/↑ | [2, 59] |

| Ferroportin | Gut, kidney | Fe2+ | Yes | ↓/↑ | [2] |

| LTCC | Heart, endocrine, VSM, CNS | Fe2+ | Noa | ↔ | [18, 68] |

↓ indicates decreased expression/activity; ↑, increased expression/activity; ↔, no change in expression/activity

TfR Transferrin receptor, IRE iron-responsive element, CNS central nervous system, IO iron overload, ID iron depletion, VSM vascular smooth muscle

aRefers to alpha1C (CaV1.2) and alpha1D (CaV1.3) subunits

Transferrin–transferrrin receptor system

The best characterized and most prevalent method for iron transport involves the binding of plasma diferric-transferrin iron (i.e. transferrin-bound iron) to type I or type II transferrin receptors (i.e. TfR1 or TfR2). In individuals with normal iron levels, plasma iron is almost exclusively bound to transferrin (Tf), an abundant plasma protein with an extraordinarily high affinity for ferric iron at normal plasma pH [1, 2]. Transferrin-bound ferric iron is relatively “non-reactive” and is extracted from the plasma by most cells of the body following binding of ferritin to transferrin receptors (TfR1 and TfR2) in clathrin-coated regions of the cell membrane [1, 2]. Complexes of transferrin and TfR1/2 are internalized into acidic endosomes where the iron is reduced (to Fe2+) and released into the cytosol by the divalent metal transporter 1, DMT-1 (see below) [2]. While the type 1 transferrin receptor, TfR1, is ubiquitously expressed, the TfR2 expression is restricted to hepatocytes, duodenum and erythroid precursors [2, 56]. Both receptors are expressed at relatively high levels in hepatocytes of the liver and enterocytes of the small intestine, especially the duodenum. The expression of TfR1 is profoundly down-regulated under iron-overload conditions, particularly in the liver, through the action of iron-response elements [1, 2]. By contrast, TfR2 protein expression is up-regulated when iron is elevated, making TfR2 a potential sensor or marker of iron status [56, 57]. TfR2 up-regulation is probably an important contributor to excessive hepatic iron uptake in iron overload [56, 57].

Divalent metal transporter 1

In addition to transferrin-bound iron, iron also enters cells by DMT1 transporters (also called Nramp2, DCT1 or SLC11A2), which are H+/divalent metal symporters capable of transporting many other divalent metals including Mn2+, Cu2+, Zn2+ and Cd2+ [58–60]. DMT1 is highly expressed in the kidney and intestines while being expressed at much lower levels in brain and heart [58–60]. In the brush borders of the duodenum, DMT1 transports iron into enterocytes from the intestinal lumen following reduction in dietary non-Tf-bound ferric to ferrous iron by intestinal ferric reductase Dcytb, a process that is facilitated by low pH in the duodenum where most of the dietary iron is absorbed (Fig. 1) [58–60]. As already mentioned, DMT1 also mediates iron export from the intracellular endosomes following iron uptake via the transferrin and heme uptake systems.

Heme–iron transport

Iron can also be imported as a heme–iron complex into selected tissues such as intestinal enterocytes and reticulo-endothelial macrophages by a putative “heme receptor”, whose molecular identity remains unclear. A membrane receptor called feline leukemia virus type C receptor (FLVCR) can facilitate transport of heme into erythrocytes and may also impact on heme transport in the intestine and liver [61]. Once internalized, heme-bound iron is released by heme oxygenase.

Ferroportin

Ferroportin (Fpn), a divalent iron export protein that is also known as iron-regulated protein (IREG1), metal-transporter protein (MTP1) or SLC11A3, is highly expressed on the surface of enterocytes, macrophages, hepatocytes and placental cells [7, 38, 39]. In these cells, Fpn exports reduced iron into the plasma, whereupon the iron is oxidized by ceruloplasmin or hephaestin, which are copper-containing ferroxidases found in the serum as well as the basolateral surface of enterocytes. Once oxidized, iron binds to transferrin [2, 55]. Fpn levels are regulated by the binding of hepcidin, a critical iron regulatory protein (see below), which leads to Fpn internalization and degradation, thereby decreasing export of cellular iron [38, 39]. As already mentioned, type 4 primary hemochromatosis is associated with Fpn mutations leading to impaired export of cellular iron and the subsequent accumulation of iron and iron overload (see Fig. 1) [7, 38, 39]. There are multiple Fpn mutations leading either to defective cell surface localization, decreased ability to be internalized and degraded in response to hepcidin, or dominant negative mutants, which may explain the phenotypic variation as well as the dominant inheritance of the disease [38, 39]. In addition to controlling the exit and release of intracellular iron, ferroportin also controls the intestinal uptake of extracellular iron at the apical membrane, possibly by modulating the activity of DMT1 [62].

Non-transferrin bound iron

Although iron absorption is normally tightly regulated in order to maintain iron at levels that prevent tissue damage due to oxidative stress, elevated body iron does occur under several disease conditions due to excessive intestinal iron absorption or repeated blood transfusions leading to surplus iron accumulation in tissues such as liver, spleen, bone marrow, pancreas, heart, pituitary and central nervous system. As transferrin becomes iron-saturated, iron increasingly resides as NTBI, which is readily transported into selected tissues of the body, particularly heart, endocrine tissue and brain [8, 9]. In patients with secondary iron overload, total serum iron levels range from 20 to 60 μM (normal range=8–15 μM) with estimated NTBI levels ranging from 1 to 10 μM [2, 8, 9, 63]. Excessive iron levels in the cell saturate the ferritin binding capacity, leading to iron binding to low molecular weight compounds that form the LIP. This iron is highly catalytically active and participates in free-radical-generating reactions [2, 14].

Although the mechanism for the transport of NTBI into cells remains unclear, it is clear that selected tissues are particularly susceptible to excess iron uptake when NTBI is present. Several transport mechanisms have been proposed to participate in NTBI uptake. Recent evidence suggests that TfR2 is responsible for the excessive iron uptake into liver hepatocytes since TfR2 expression levels increase in iron overload, leading to liver cirrhosis and hepatic tumors [56, 57]. However, NTBI uptake into excitable cells such as cardiomyocytes, neurons, beta cells of the pancreas and pituitary cells requires reduction of ferric iron (Fe3+) to ferrous iron (Fe2+) by a membrane-associated ferri-reductase system, properties that clearly distinguish it from transferrin-receptor-mediated ferric iron uptake [11, 12, 64]. In these excitable tissues, it has been suggested that NTBI uptake is DMT1-dependent [59]. However, the maximum NTBI uptake rate (i.e. V max) in cardiomyocytes increases without changes in sensitivity to iron (i.e. K D), which contrasts with DMT1 whose protein expression decreases when iron is elevated [60]. In addition, DMT1 is expressed at extremely low levels in most excitable tissue including the heart [59, 60]. We have shown that NTBI uptake into cardiomyocytes is dependent on L-type Ca2+ channels, which are known to be promiscuous divalent metal transporters [65–68]. Importantly, L-type Ca2+ channels satisfy all the criteria consistent with the NTBI transporter, and most importantly, this transporter readily explains the pattern of tissues at risk for damage and dysfunction under iron-overload conditions. Specifically, tissues with the greatest risk in iron overload are excitable tissues with high duty cycles for L-type Ca2+ channel activity: cardiomyocytes, anterior pituitary cells, pancreatic beta cells and neurons (see Table 3). Evidence supporting a critical role for NTBI uptake by L-type Ca2+ channels in cardiomyocytes of the heart is reviewed below.

Table 3.

Correlation between tissue containing LTCC and iron-mediated injury

| Organ | Cell type | LTCC isoform | Function | Disease | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart | Cardiomyocyte | Cav1.2 | EC coupling | Cardiomyopathy | [18, 68, 89, 106, 128] |

| AV node(and SA node) Purkinje fibre | Cav1.2,Cav1.3 | Pacemaker activity and conduction | AV nodal and bundle branch blocks | [89–92, 128, 134, 136, 137] | |

| Anterior pituitary | Gonadotrophs | Cav1.2, Cav1.3 | ES coupling | Hypogonadism (secondary) | [22, 23, 129, 149, 150, 151, 183] |

| Thyrotrophs | Cav1.2, Cav1.3 | ES coupling | Hypothyroidism (secondary) | [22, 152, 183] | |

| Corticotrophs | Cav1.2, Cav1.3 | ES coupling | Impaired ACTH reserve | [21, 23, 183, 184] | |

| Endocrine pancreas | Beta cells (and alpha cells) | Cav1.2, Cav1.3 | ES coupling | Insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus | [21, 22, 128, 158, 185] |

| Vasculature | VSMC | Cav1.2 | ES coupling | Hypotension | [87, 128, 132] |

| Parathyroid gland | PTH-producing cells | Cav1.2 | EC coupling | Hypo-parathyroidism | [22, 154, 157] |

| Bone | Osteoblast | Cav1.2 | ES coupling | Osteomalacia, osteoporosis | [25, 26, 126] |

| Brain | Neurons | Cav1.2, Cav1.3 | Neuro-transmitter release | Neurodegenerative diseases | [32, 33, 128, 183] |

EC Excitation–contraction, ES excitation–secretion, AV atrioventricular, SA sinoatrial, PTH parathyroid hormone, ACTH adrenocorticotrophin, VSMC vascular smooth muscle cell, Cav1.2 alpha1C subunit, Cav1.3 alpha1D subunit

Mechanisms for the regulation of iron

Iron homeostasis necessitates tight control of iron uptake, storage and export as well as management of intracellular iron distribution [1, 2]. A major requirement for proper iron homeostasis is limiting the labile intracellular iron while simultaneously ensuring iron availability for many essential iron-containing proteins and enzymes. Since the loss of iron from the body is, under normal circumstances, largely independent of the total body iron, alterations in total body iron are primarily set by modulation of its absorption in the small intestines, especially in the duodenum. Iron uptake by the small intestine appears to be regulated by two interrelated processes: crypt programming and hepcidin expression levels [2, 7]. Crypt programming involves setting the iron uptake rates in mature villus enterocytes based on the total body iron levels sensed by developing enterocytes within the intestinal crypts via TfR1/2. Specifically, iron levels in the developing enterocytes influences the expression pattern of various iron transporters. Intestinal iron uptake also appears to be regulated in immature enterocytes by HFE, the gene involved in type I hemochromatosis [7]. With mutations in HFE in human (as well as in HFE knockout mice), transferrin-bound iron uptake is decreased in association with enhanced expression and activity of FPN1, resulting in increased iron export from enterocytes into the blood [69, 70]. Regulation of iron uptake in enterocytes may also involve beta 2-microglobulin that forms a macromolecular complex with HFE and TfR1.

Modulation of iron transport in small intestinal enterocytes and reticulo-endothelial macrophages by hepcidin represents an alternate mechanism for regulating iron. Hepcidin is a small (20–25 amino acids) cysteine-rich antimicrobial peptide that is expressed and secreted into the blood by the liver in response to elevated iron and inflammation [2, 7, 36]. Hepcidin inhibits iron excretion in macrophages and enterocytes by binding to Fpn1, leading to internalization and loss of function of Fpn1 [38]. By contrast, in iron deficiency and anemia as well as in type 1 primary hemochromatosis, hepcidin levels are reduced, which increases Fpn1 expression as well as iron release from enterocytes and macrophages [70]. Indeed, loss of HFE function in type 1 primary hemochromatosis impairs the ability of hepcidin to regulate duodenal iron absorption, which may be the mechanism responsible for excessive iron absorption under this condition [70, 71]. Thus, post-translational regulation of Fpn1 by hepcidin forms a homeostatic loop whereby iron regulates secretion of hepcidin, which in turn controls the concentration of Fpn1 and thereby iron export at the enterocyte surface [38, 72]. This loop also operates in the regulation of iron levels under inflammatory conditions, which may explain the anemia in chronic inflammation as well as the antimicrobial actions of hepcidin [2, 7, 70, 73]. Although the precise physiological role of hemojuvelin (HJV; also known as RGMc and HFE2), a glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored protein, remains to be elucidated, recent experimental and clinical studies indicate that HJV is involved in the inflammation-induced increases of hepcidin expression [7, 36, 74, 75]. This connection helps explain the central role of hepcidin (and HJV) in the pathogenesis of juvenile hemochromatosis as well as anemia in chronic diseases (see Table 1) [7, 36, 74, 75].

The regulation of iron crypt programming and hepcidin, as well as the regulation of iron uptake in many cells of the body, involves tight negative-feedback regulation [2, 7, 9, 58] via iron regulatory proteins (IRP1 and IRP2) that recognize iron-responsive elements (IRE) located on the 3′ or 5′ untranslated regions (UTR) of mRNA for many iron-regulated genes. For example, the transferrin receptors and H and L subunits of the intracellular iron-storage protein, ferritin [76, 77], contain IREs in the 3′-UTR and 5′-UTR of their mRNAs, respectively [2, 78]. Under conditions of low iron, IRP binding to IREs blocks translation of ferritin mRNA and stabilizes transferrin receptor mRNA. When labile intracellular iron increases, IRP1 binding to IREs leads to IRP2 degradation, resulting in efficient translation of ferritin and rapid degradation of transferrin receptor mRNA [2, 77, 78]. DMT1 and FPN1 also contain IREs in their mRNA UTRs that are suggested to be responsible for the decreased DMT1 expression in the heart (and intestine) observed with iron overload (Table 2) [2, 7, 59, 60].

Iron-overload cardiomyopathy

Clinical description

Iron-overload cardiomyopathy is a common cause of death due to cardiovascular complications especially in the second and third decades of life [4–6, 79, 80]. Indeed, in European [81], North American [79, 80] and Chinese [24] patients with thalassemia major, the severity of cardiac dysfunction is the primary determinant of survival, while in patients with primary hemochromatosis, cardiovascular disease also contributes significantly to their mortality and morbidity [82–85]. In addition, cardiac iron accumulation in beta-thalassemia patients correlates directly with both heart disease and mortality [5, 79, 80]. Although iron chelation therapy is widely used for treating iron-overload patients, cardiomyopathy and mortality are still common in these patients [24, 86]. Regardless of its origin, iron overload in patients [13, 87, 88] and animal models [18, 19] leads to a restrictive cardiomyopathy with prominent early diastolic dysfunction that invariably progresses to end-stage dilated cardiomyopathy characterized by impaired systolic function and reduced mean arterial blood pressure often accompanied by arrhythmias including atrioventricular (AV) block, conduction defects, bradyarrhythmias, tachyarrhythmias and sudden cardiac death (Fig. 3) [79, 80, 84, 89–92]. AV nodal block is a particularly common occurrence, which is due to an especially high accumulation of iron in the AV nodal compared to other tissues of the heart (see Fig. 3 and Table 3) [89].

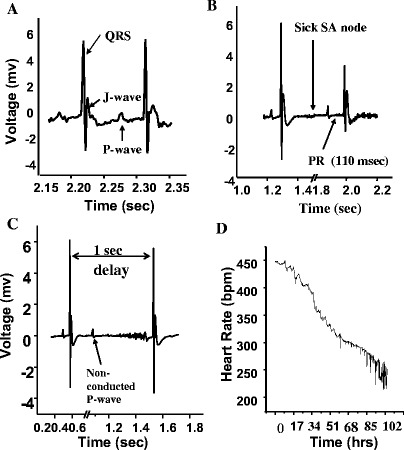

Fig. 3.

Telemetric recordings from conscious mice that were injected with placebo or iron (n=6) over a 4-week period as previously reported [18]; baseline heart rate=500–600 bpm. a Normal ECG tracing. b Iron-overload-induced first-degree AV block (PR interval=42±2.1 vs 89.2± ms; p<0.01) and sinus arrest (sick SA node). c Iron-overload-induced AV block as illustrated by Mobitz type II block and conduction delay with widened QRS complex (QRS duration=16.4±0.6 vs 41.2±4.9 ms; p<0.01). d Progressive bradycardia in an iron-overloaded mouse that occurred over a 5-day interval culminated into an idioventricular rhythm and death; mv millivolt, bpm beats per minute

Pathophysiology

The precise mechanism underlying cardiomyocyte dysfunction induced by iron overload is not entirely clear. Iron within cells can be divided into the “unavailable” or tightly bound pool, which includes iron in ferric hydroxide precipitates and iron complexed with ferritin, and the “available” LIP. The LIP is more readily available for Fenton-type reactions whereby the conversion of reduced iron (Fe2+) into oxidized iron (Fe3+) generates various free radicals [15, 93]. Under normal physiological conditions, the generation of free radicals is minimized by a repertoire of enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant mechanisms [93]. However, when iron levels are chronically elevated, excessive free radical generation leads to depletion of antioxidants and increased cellular damage due to oxidation of lipids, proteins and nucleic acids [19, 93]. in animal models [18, 19, 94] as well as in patients with primary hemochromatosis, beta-thalassemia major and end-stage kidney disease [95–97]. Oxidation of lipids (i.e. lipid peroxidation) is of particular importance in iron overload that leads to marked increases in unsaturated (malondialdehyde and hydroxynonenal) and saturated (hexanal) aldehydes in the heart and plasma [18, 19]. These compounds are associated with cellular dysfunction, cytotoxicity and cell death [18, 19, 93, 98, 99]. Consistent with a critical role of oxidative stress in iron-overload cardiomyopathy, the risk of developing iron-overload cardiomyopathy in patients with primary hemochromatosis is strongly influenced by polymorphisms of the manganese-superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) gene [100]. Additional factors that may also modulate the amount of oxidative stress observed under iron-overload conditions include inflammation [101, 102] and ApoE polymorphisms (indicator of low intrinsic antioxidant status) [103].

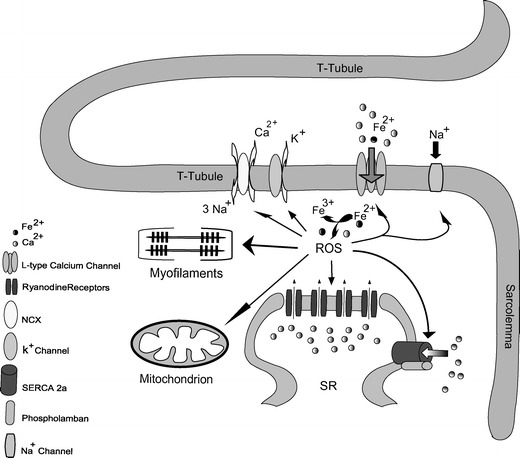

Iron-induced oxidative damage can have multiple effects on cardiac function. For example, iron overload has been linked to cardiomyocyte loss due to apoptosis [19, 29, 93], which can be reduced by antioxidant treatment [19]. Enhanced apoptosis and/or necrosis in iron-overload cardiomyopathy could be linked to altered mitochondrial function as seen in Friedreich ataxia [93, 104, 105]. Increased myocyte loss is probably a major contributor to the prominent interstitial fibrosis seen in iron-overload cardiomyopathy, although iron-mediated effects on cardiac fibroblasts might also contribute [9]. Regardless, reduced cardiomyocyte numbers combined with increased myocardial interstitial fibrosis are predicted to contribute to impaired systolic and diastolic function in iron-overloaded hearts. Increased iron-mediated oxidative stress can also directly alter myocyte electrical and contractile properties by affecting the function of several regulators of cardiac excitation–contraction coupling [106–108]. Specifically, with elevated oxidative stress, sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+ leak through ryanodine receptors (Ca2+ release channels) [109] is increased, sarcoendoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) activity is inhibited, sodium–calcium exchanger (NCX) [110] currents are elevated, LTCCs are reduced [111, 112] and sodium as well as potassium currents can be either enhanced or depressed (see Fig. 2) [113]. These effects can occur by direct protein oxidation or by the generation of lipid peroxidation products [114, 115]. Collectively, elevated oxidative stress leads to reduced peak systolic Ca2+ levels, slowed rates of Ca2+ relaxation and elevated diastolic Ca2+ levels, which probably contribute to the impaired systolic and diastolic function observed in iron-overload cardiomyopathy and also leads to arrhythmias, impaired electrical conduction and sudden death [116].

Fig. 2.

Interaction between iron-mediated oxidative stress and the excitation–contraction coupling in a cardiomyocyte. ROS reactive oxygen species, SERCA2a sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ATPase isoform 2, NCX sodium–calcium exchanger, SR sarcoplasmic reticulum

Altered function of ion channels and electrogenic transporters in response to iron overload and elevated oxidative stress can lead to increased susceptibility and generate arrhythmias in the heart [113, 116, 117], which are commonly observed under iron-overload conditions [79, 113, 116]. For example, spontaneous Ca2+ release combined with slowed Ca2+ re-uptake in the SR and increased NCX activity predisposes to increased triggered arrhythmias and delayed after-depolarization that are observed under iron-overload conditions. In iron-overloaded gerbils, ventricular action potential duration has been shown to be abbreviated in connection with increased transient outward K+ current (I to) densities coupled with reduced Na+ currents [113], although reduced L-type Ca2+ currents might also contribute. In iron-treated mice and gerbils, common electrophysiological observations include QRS prolongation accompanied by slowed conduction velocity, bradycardia and prolongation of the PR interval in association with first- and second-degree AV block (Fig. 3) [92]. Slowed conduction in the heart may be related to the observation that elevated oxidative stress reduces cardiac voltage-gated Na+ currents [118]. Action potential shortening and abnormal impulse conduction [92, 113] in the setting of increased interstitial fibrosis observed in iron overload [18, 19] increase the propensity for unidirectional conduction block, wavefront breakup and creation of arrhythmic ventricular re-entry circuits [92, 117]. The reduced heart rates and AV block may be related to a combination of preferential iron deposition and increased interstitial fibrosis in these regions [18, 89–91]. In addition, iron deposition in the myocardium is heterogeneous, which can further promote arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death by increasing the heterogeneity of ventricular repolarization and QT dispersion, which is linearly correlated with iron burden [89, 113, 119].

In addition to the direct effects on the heart, elevated iron can also affect the function of vascular smooth muscle cells and endothelial cells. Indeed, endothelial dysfunction and increased arterial stiffness are commonly observed in patients with primary hemochromatosis [120], beta-thalassemia major [121] and sickle cell anemia [122]. These vascular changes can in turn affect myocardial perfusion and function.

NTBI transport by L-type Ca2+ channels in heart

The basis for the high sensitivity of the heart (and other excitable tissues) to excessive iron uptake, damage and dysfunction under conditions of iron overload was an enigma for many years. However, several classical characteristics of NTBI transport and of the cardiomyopathy under iron-overload conditions provide important insights into the possible mechanism of iron transport into the heart under these conditions. For example, NTBI transport in cardiomyocytes requires divalent ferrous, not trivalent ferric, iron, and its rate increases markedly with chronic iron elevations [12, 64, 68]. These two features argue strongly against TfR-mediated or DMT1-mediated mechanisms for NTBI transport in the heart. Specifically, TfR1 transports ferric iron and TfR1 mRNA expression is reduced in association with a 63% decline in IRP1 in cardiomyocytes exposed to chronic elevations in iron [123]. Similarly, while DMT1 can transport ferrous iron, myocardial DMT1 mRNA expression has been shown either to decrease with elevated iron in adult hearts [60] or to be uncorrelated with changes in iron accumulation in cultured myocytes despite the absence of mRNA changes [123]. The lack of involvement of these iron transporters in myocardial NTBI uptake is further supported by low-level TfR1-dependent iron uptake into heart as well as the extremely low expression levels of TfR1 and DMT1 in the heart [60, 123].

Unlike DMT1 and TfR, L-type Ca2+ channels satisfy all the known properties of NTBI transport. Indeed, while LTCCs are primarily utilized for the transport of Ca2+, they are able to transport many other divalent, but not trivalent, cations including Fe2+, Zn2+, Co2+, Sr2+, Ba2+ and Mn2+ [66–68, 124]. Consistent with a dominant role of LTCC in myocardial iron transport, iron uptake is increased by the selective LTCC agonist, Bay K 8644, as well as following beta-adrenergic stimulation in proportion to the degree of LTCC current enhancement while being inhibited by LTCC blockers [68]. Moreover, low Fe2+ levels slow the rate of LTCC current inactivation, resulting in increased Fe2+ entry per heartbeat [68], and L-type Ca2+ currents are not decreased in iron overload [18], consistent with the absence of IREs in the mRNA of the pore-forming subunits of cardiac LTCCs (i.e. CaV1.2) (see Table 2). The Fe2+-mediated slowing of Ca2+ current inactivation could arise from competition between Fe2+ and Ca2+ for the C-terminal cytoplasmic Ca2+ binding site involved in Ca2+-mediated inactivation of LTCCs [108]. Thus, LTCCs are the only Fe2+ transporter whose activity increases with elevated iron, consistent with NTBI uptake in the heart under iron-overload conditions [9, 12, 18, 68]. Remarkably, the amount of myocardial iron accumulation predicted to occur via LTCCs over 20 years, a relevant period for patients with iron overload, is estimated to be about 10 mg of iron per gram of myocardial tissue [68], which matches closely to the 3–10 mg/gm of myocardial iron measured in patients with iron-overload cardiomyopathy [89] and in animal models [18, 19].

A more definitive link between LTCCs and myocardial iron deposition was obtained in mouse studies where LTCC blockers, like amlodipine and verapamil, reduced intracellular myocardial iron accumulation and reduced oxidative stress while protecting diastolic and systolic cardiac function [18]. Total myocardial iron level was determined by atomic absorption spectrophotometry, while intracellular iron deposition was examined by Prussian blue histological staining coupled with analytical electron microscopy [18, 19]. Moreover, cardiac-specific LTCC overexpression caused increases in myocardial iron accumulation and oxidative damage in proportion to the elevated Ca2+ currents that were, again, reduced with LTCC blockers [18]. These beneficial cardiac effects of LTCC blockers in iron-overload mice were not observed in the liver, as would be expected, since hepatocytes express minimal levels of functional LTCCs [125]. Involvement of LTCC in iron transport is also supported by the protective actions of taurine (i.e. 2-aminoethane-sulphonic acid) supplementation against myocardial iron accumulation, oxidative damage, and altered cardiac structure and function [19]. The link between LTCCs and iron uptake in excitable tissues is consistent with the observation that the maximal rates of iron uptake (V max) are approximately tenfold higher in cardiomyocytes than in fibroblasts [12, 64, 123] that have few if any LTCCs. The link between LTCC and myocardial iron transport is further substantiated by the high susceptibility to iron-mediated injury and disease observed in excitable cells that require high LTCC activity for proper functioning such as excitation–contraction coupling in vascular smooth muscle cells [106–108] as well as in excitation–secretion coupling in osteoblasts [126], endocrine cells and neurons [106, 127–129].

The molecular basis for iron permeation in LTCC has not previously been examined. However, ion selectivity, permeability and blocking properties of LTCCs are dictated by electrostatic binding of ions within the pore [130, 131]. Strong electrostatic interactions between ions and the selectivity filter combined with a large pore radius (i.e. 6.2 nm) allows many divalent cations to readily permeate LTCCs, independent of their ionic radius (i.e. r Ca=2.4 nm vs r Fe=2 nm), although some permeant ions also “block” LTCC currents depending on the relative binding affinity [65, 124]. By contrast, under normal biological conditions, monovalent cations cannot easily permeate LTCC, while trivalent cations are often potent blockers of LTCCs. These biophysical properties of cardiac LTCCs originate from the pore-forming α1 subunits that are comprised of four internal repeat domains (I–IV) each made up of six membrane-spanning segments (S1–S6) [106, 108, 132] and which co-assemble with β-subunits and α2/δ-subunits to form functional LTCCs [106, 108]. The cardiac α1 subunits are members of a highly homologous family of high-voltage-activated Ca2+ channel genes (i.e. the Cav1 family) that includes Cav1.1, Cav1.2 (α1C) and Cav1.3 (also called α1S, α1C and α1D) [106, 108, 132] Cardiomyocytes express Cav1.2 [128, 133, 134], which is also expressed (as spliced variants) in vascular smooth muscle [128], brain [128] and endocrine tissue including pancreatic beta cells [127, 128]. Cav1.3 shows a far more restricted expression pattern, being found in sinoatrial (SA) nodal cardiomyocytes [133] as well as pancreatic beta cells where it plays a relatively minor role in insulin release [128]. Cav1.1 subunits are expressed in skeletal muscle [106]. Given the high degree of amino acid identity and thereby structural similarity between the Cav1 family members, it seems likely that LTCCs also participate in NTBI uptake in excitable tissues other than the heart. Indeed, as already mentioned, the cells most susceptible to damage and dysfunction in iron overload are precisely those having high densities of LTCC. One potential glaring exception to this pattern is skeletal muscle cells, which have high densities of LTCC. However, skeletal muscle cells utilize LTCCs for excitation–contraction coupling without requiring ion permeation [106], consistent with the relative resistance of skeletal muscle to the effects of iron overload.

Involvement of LTCC in iron transport helps explain several key clinical features of iron-overload cardiomyopathy. For example, second- and third-degree heart blocks are commonly observed in iron overload, and these patients often require pacemaker device implantation [89–91]. Prominent AV node pathology is consistent with the essential requirement of LTCC in AV nodal conduction [135] that is reflected in the very high baseline LTCC current densities recorded in AV nodal myocytes (i.e. 14–18 pA/pF) [136, 137]. Iron transport by LTCC could explain the observation that the L-type Ca2+ channel blocker diazepam protects the heart against acute iron-induced toxicity and mortality without affecting iron absorption and excretion [138, 139]. Similarly, Ca2+ channel blockers protect the myocardium from ischemia–reperfusion injury [140, 141], which has been linked to iron-mediated injury [29, 142].

NTBI entering cardiomyocytes is effectively trapped in the cytosol following rapid redox cycling to ferric iron and binding to ferritin [76, 143], conversion to the insoluble ferric iron (hemosiderin) deposits [113] or expansion of the reactive LIP leading to iron-mediated oxidative damage. Permeation of reduced, reactive iron (Fe2+) through LTCCs in iron overload may help explain the profound contractile dysfunction, Ca2+ overload and impaired diastolic function commonly observed during the early stages of iron overload [13, 42, 84, 88]. Specifically, the reduced iron entering through LTCCs has preferential access to the major regulators of excitation–contraction coupling (Fig. 2). Moreover, Fe2+-induced slowing of LTCC current inactivation by Fe2+ leads to increased Ca2+ entry and Ca2+ overload [68]. Since elevated Ca2+, particularly through LTCCs, is involved in the initiation and progression of heart disease in a calcineurin-dependent manner [144], it is conceivable that the slowing of LTCC inactivation by NTBI may contribute to the cardiomyopathy seen in iron overload. Additionally, slowed inactivation of LTCCs positively feedback to further increase NTBI Fe2+ entry into cardiomyocytes, thereby amplifying alterations in cellular function. Elevations in cytosolic iron also lead to iron uptake into mitochondria where it normally becomes incorporated into Fe–S clusters and is utilized for heme biosynthesis [3]. Iron homeostasis in the mitochondria requires frataxin, a ferroxidase that detoxifies redox-active iron, thereby providing a critical anti-oxidative defense against iron-derived radicals in the mitochondria [145, 146]. Frataxin deficiency causes a clinical syndrome called Friedreich ataxia that involves neurodegeneration, dilated cardiomyopathy and diabetes mellitus [147].

Although our previous results provide unequivocal evidence for NTBI transport by LTCC in heart, the application of LTCC blockers failed to alter iron uptake rates in cultured rat neonatal myoctes [64]. However, these studies should be interpreted with caution for several reasons. First, neonatal myocytes have much smaller L-type Ca2+ current compared to adult myocardium [148]. Second, when culturing neonatal cardiomyocytes at low densities, the fraction of beating myocytes is very low and beating rates are slow compared to normal heart rates. Therefore, it is imperative that electrical pacing be used in conjunction with high-density cultures when examining the role of LTCC in iron transport. Third, neonatal cultures suffer from high rates of myocytes death, particularly in the presence of iron, making it essential to consider the number of viable cells in the calculation of iron uptake rates. Fourth, our results predict that LTCCs also contribute to ferrous iron export. Consequently, at non-physiologically high iron loads (as used in the cultured myocyte studies), LTCC blockers are predicted to have a limited impact on the net iron uptake. Collectively, the validity of the neonatal cultured myocyte system as a tool to test the role of LTCCs as iron transporters is questionable [64].

Endocrine dysfunction in patients with iron-overload: a potential role for LTCC

L-type Ca2+ channels are present in large numbers in pancreatic beta cells [127, 128] and in various cell types of the anterior pituitary gland including gonadotrophs [149–151], thyrotrophs [152], corticoptrophs [153] and in the parathyroid-hormone-producing cells of the parathyroid gland (Table 3) [154]. In these endocrine cells, LTCCs are critically involved in excitation–secretion coupling whereby membrane depolarization activate (open) LTCCs, allowing extracellular Ca2+ entry and stimulation of exocytosis [127, 149, 151]. Given the important role of LTCC in mediating cellular NTBI uptake, it seems plausible to suggest a link between LTCCs and iron-overload-induced dysfunction in these endocrine tissues. Similar to cardiomyocytes, excessive Fe2+ entry through LTCCs is expected to impair secretion and increase cell loss (see Table 3). Consistent with this mechanism, histological and immunohistochemical analyses have confirmed deposition of iron in human beta cells [155], while imaging studies have shown iron accumulation in the anterior pituitary gland in patients with iron overload [156].

These observations help explain the observation that endocrinopathies are common co-morbidities present in patients with iron overload and include diabetes mellitus [21, 22, 24, 155], hypoparathyroidism [22, 157] and anterior pituitary dysfunction associated with hypopituitary hypogonadism [22–24], impaired adrenocorticotrophin reserve [21, 23] and hypothyroidism [22]. Diabetes mellitus in patients with iron overload is associated with reduced insulin reserve and impaired insulin release. Consequently, most patients often progress to be insulin-dependent relatively early during the course of illness [21, 22, 158]. In addition, up to 50% of patients with beta-thalassemia major have a short stature and failure of puberty associated with primary and secondary amenorrhea in women [22, 24].

Therapeutic implications for CCBs under iron-overload conditions

Calcium channel blockers (CCBs) are widely used to treat cardiovascular diseases in both pediatric [159] and adult [160, 161] populations. The recognition that LTCCs are critical transporters of iron under conditions of iron overload opens up the possibility of using CCBs in the treatment and/or prevention of iron-overload cardiomyopathy in combination with standard chelation therapy. Unlike iron chelators that are effective in removing excess iron accumulation in cells, CCBs are expected to be particularly effective early in iron overload by reducing tissue iron uptake and preventing disease progression. In advanced iron overload, the potential effectiveness of CCBs may be limited, but they should block further iron uptake, thereby enhancing the effectiveness of iron chelation therapies. However, the applicability of CCBs in the setting of advanced dilated cardiomyopathy or conduction block may be limited due to their negative inotropic and chronotropic effects.

While the data supporting the potential effectiveness of CCBs in the treatment of iron-overload cardiomypathy has been obtained in rodents, pharmacological blockade of LTCC might have an even greater therapeutic benefit in humans for two reasons: (a) humans lack iron excretory pathways that are present in rodents [1, 2], and (b) humans have proportionately larger trans-sarcolemmal I Ca,L influx per cardiac cycle [162]. The translation of the rodent studies to humans is bolstered by the observation that the plasma concentration of CCBs required to reduce iron accumulation in murine hearts [18] is similar to levels reported in patients [163–165]. Blockade of the LTCC may also provide additional benefits beyond a direct inhibition of Fe2+ entry into cardiomyocytes and endocrine tissues. For example, CCBs could potentially reduce Fe2+-induced Ca2+ overload as a result of LTCC inactivation [68] and thereby facilitate diastolic ventricular filling [166]. Finally, calcium channel blockers may promote myocardial microvascular perfusion by vasodilating coronary arterioles while improving coronary endothelial function [132, 167]. LTCC blockers like amlodipine also possess antioxidant properties that could help offset the oxidative effects of iron overload [167]. Given the high degree of oxidative stress, diastolic dysfunction and possibility for coronary endothelial dysfunction in iron-overload cardiomyopathy, these effects may increase the potential therapeutic benefits of CCBs in patients with iron overload. In addition to protecting the heart, pharmacological blockade of LTCCs may also reduce the endocrinopathies observed in iron-overload patients. Clearly, clinical trials are warranted to establish the clinical efficacy and safety of CCB treatment in patients with iron overload.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the financial support from the Canadian Institute for Health Research (P.H.B. and P.L.). G.Y.O. is a recipient of a Postdoctoral Fellowship from the Canadian Institute for Health Research, Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada and from the TACTICS program, and P.H.B. is a Career Investigator of the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario.

Abbreviations

- LTCC

L-type calcium channel

- ICa

LTCC current

- NTBI

Non-transferrin bound iron

- CCB

Calcium channel blocker

- AV

Atrioventricular

- SA

Sinoatrial

- VSMCs

Vascular smooth muscle cells

- LIP

Labile intracellular iron pool

- DMT1

Divalent metal transporter 1

- TfR

Transferrin receptor

Contributor Information

Gavin Y. Oudit, Email: gavin.oudit@utoronto.ca

Peter H. Backx, Phone: +1-416-9468112, FAX: +1-416-9468380, Email: p.backx@utoronto.ca

References

- 1.Andrews NC. Disorders of iron metabolism. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1986–1995. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912233412607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hentze MW, Muckenthaler MU, Andrews NC. Balancing acts; molecular control of mammalian iron metabolism. Cell. 2004;117:285–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00343-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Napier I, Ponka P, Richardson DR. Iron trafficking in the mitochondrion: novel pathways revealed by disease. Blood. 2005;105:1867–1874. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-3856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weatherall DJ, Clegg JB. Thalassemia—a global public health problem. Nat Med. 1996;2:847–849. doi: 10.1038/nm0896-847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olivieri NF. The beta-thalassemias. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:99–109. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199907083410207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weatherall DJ, Clegg JB. Inherited haemoglobin disorders: an increasing global health problem. Bull World Health Organ. 2001;79:704–712. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pietrangelo A. Hereditary hemochromatosis—a new look at an old disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2383–2397. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra031573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Breuer W, Hershko C, Cabantchik ZI. The importance of non-transferrin bound iron in disorders of iron metabolism. Transfus Sci. 2000;23:185–192. doi: 10.1016/s0955-3886(00)00087-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Templeton DM, Liu Y. Genetic regulation of cell function in response to iron overload or chelation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1619:113–124. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(02)00497-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Esposito BP, Breuer W, Sirankapracha P, Pootrakul P, Hershko C, Cabantchik ZI. Labile plasma iron in iron overload: redox activity and susceptibility to chelation. Blood. 2003;102:2670–3677. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaplan J, Jordan I, Sturrock A. Regulation of the transferrin-independent iron transport system in cultured cells. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:2997–3004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Randell EW, Parkes JG, Olivieri NF, Templeton DM. Uptake of non-transferrin-bound iron by both reductive and nonreductive processes is modulated by intracellular iron. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:16046–16053. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu P, Olivieri N. Iron overload cardiomyopathies: new insights into an old disease. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 1994;8:101–110. doi: 10.1007/BF00877096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee DH, Jacobs DR., Jr. Serum markers of stored body iron are not appropriate markers of health effects of iron: a focus on serum ferritin. Med Hypotheses. 2004;62:442–445. doi: 10.1016/S0306-9877(03)00344-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gutteridge JM, Rowley DA, Griffiths E, Halliwell B. Low-molecular-weight iron complexes and oxygen radical reactions in idiopathic haemochromatosis. Clin Sci (Colch) 1985;68:463–467. doi: 10.1042/cs0680463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Artman M, Olson RD, Boucek RJ, Jr., Boerth RC. Depression of contractility in isolated rabbit myocardium following exposure to iron: role of free radicals. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1984;72:324–332. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(84)90317-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vernon DD, Banner W, Jr., Dean JM. Hemodynamic effects of experimental iron poisoning. Ann Emerg Med. 1989;18:863–866. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(89)80214-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oudit GY, Sun H, Trivieri MG, Koch SE, Dawood F, Ackerley C, Yazdanpanah M, Wilson GJ, Schwartz A, Liu PP, Backx PH. L-type Ca(2+) channels provide a major pathway for iron entry into cardiomyocytes in iron-overload cardiomyopathy. Nat Med. 2003;9:1187–1194. doi: 10.1038/nm920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oudit GY, Trivieri MG, Khaper N, Husain T, Wilson GJ, Liu P, Sole MJ, Backx PH. Taurine supplementation reduces oxidative stress and improves cardiovascular function in an iron-overload murine model. Circulation. 2004;109:1877–1885. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000124229.40424.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seznec H, Simon D, Monassier L, Criqui-Filipe P, Gansmuller A, Rustin P, Koenig M, Puccio H. Idebenone delays the onset of cardiac functional alteration without correction of Fe–S enzymes deficit in a mouse model for Friedreich ataxia. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:1017–1024. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schafer AI, Cheron RG, Dluhy R, Cooper B, Gleason RE, Soeldner JS, Bunn HF. Clinical consequences of acquired transfusional iron overload in adults. N Engl J Med. 1981;304:319–324. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198102053040603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Italian Working Group Multicentre study on prevalence of endocrine complications in thalassaemia major. Italian Working Group on Endocrine Complications in Non-endocrine Diseases. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1995;42:581–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1995.tb02683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hempenius LM, Van Dam PS, Marx JJ, Koppeschaar HP. Mineralocorticoid status and endocrine dysfunction in severe hemochromatosis. J Endocrinol Invest. 1999;22:369–376. doi: 10.1007/BF03343575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li CK, Luk CW, Ling SC, Chik KW, Yuen HL, Shing MM, Chang KO, Yuen PM. Morbidity and mortality patterns of thalassaemia major patients in Hong Kong: retrospective study. Hong Kong Med J. 2002;8:255–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sinigaglia L, Fargion S, Fracanzani AL, Binelli L, Battafarano N, Varenna M, Piperno A, Fiorelli G. Bone and joint involvement in genetic hemochromatosis: role of cirrhosis and iron overload. J Rheumatol. 1997;24:1809–1813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsushima S, Torii M, Ozaki K, Narama I. Iron lactate-induced osteomalacia in association with osteoblast dynamics. Toxicol Pathol. 2003;31:646–654. doi: 10.1080/01926230390241990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mahachoklertwattana P, Sirikulchayanonta V, Chuansumrit A, Karnsombat P, Choubtum L, Sriphrapradang A, Domrongkitchaiporn S, Sirisriro R, Rajatanavin R. Bone histomorphometry in children and adolescents with beta-thalassemia disease: iron-associated focal osteomalacia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:3966–3972. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Voest EE, Vreugdenhil G, Marx JJ. Iron-chelating agents in non-iron overload conditions. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120:490–499. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-120-6-199403150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Turoczi T, Jun L, Cordis G, Morris JE, Maulik N, Stevens RG, Das DK. HFE mutation and dietary iron content interact to increase ischemia/reperfusion injury of the heart in mice. Circ Res. 2003;92:1240–1246. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000076890.59807.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Valk B, Marx JJ. Iron, atherosclerosis, and ischemic heart disease. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:1542–1548. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.14.1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ramakrishna G, Rooke TW, Cooper LT. Iron and peripheral arterial disease: revisiting the iron hypothesis in a different light. Vasc Med. 2003;8:203–210. doi: 10.1191/1358863x03vm493ra. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaur D, Yantiri F, Rajagopalan S, Kumar J, Mo JQ, Boonplueang R, Viswanath V, Jacobs R, Yang L, Beal MF, DiMonte D, Volitaskis I, Ellerby L, Cherny RA, Bush AI, Andersen JK. Genetic or pharmacological iron chelation prevents MPTP-induced neurotoxicity in vivo: a novel therapy for Parkinson's disease. Neuron. 2003;37:899–909. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00126-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Todorich BM, Connor JR. Redox metals in Alzheimer's disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1012:171–178. doi: 10.1196/annals.1306.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rochette J, Pointon JJ, Fisher CA, Perera G, Arambepola M, Arichchi DS, De Silva S, Vandwalle JL, Monti JP, Old JM, Merryweather-Clarke AT, Weatherall DJ, Robson KJ. Multicentric origin of hemochromatosis gene (HFE) mutations. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;64:1056–1062. doi: 10.1086/302318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bulaj ZJ, Ajioka RS, Phillips JD, LaSalle BA, Jorde LB, Griffen LM, Edwards CQ, Kushner JP. Disease-related conditions in relatives of patients with hemochromatosis. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1529–1535. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011233432104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Papanikolaou G, Samuels ME, Ludwig EH, MacDonald ML, Franchini PL, Dube MP, Andres L, MacFarlane J, Sakellaropoulos N, Politou M, Nemeth E, Thompson J, Risler JK, Zaborowska C, Babakaiff R, Radomski CC, Pape TD, Davidas O, Christakis J, Brissot P, Lockitch G, Ganz T, Hayden MR, Goldberg YP. Mutations in HFE2 cause iron overload in chromosome 1q-linked juvenile hemochromatosis. Nat Genet. 2004;36:77–82. doi: 10.1038/ng1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roetto A, Daraio F, Alberti F, Porporato P, Cali A, De Gobbi M, Camaschella C. Hemochromatosis due to mutations in transferrin receptor 2. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2002;29:465–470. doi: 10.1006/bcmd.2002.0585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nemeth E, Tuttle MS, Powelson J, Vaughn MB, Donovan A, Ward DM, Ganz T, Kaplan J. Hepcidin regulates cellular iron efflux by binding to ferroportin and inducing its internalization. Science. 2004;306:2090–2093. doi: 10.1126/science.1104742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.De Domenico I, Ward DM, Nemeth E, Vaughn MB, Musci G, Ganz T, Kaplan J. The molecular basis of ferroportin-linked hemochromatosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:8955–8960. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503804102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gordeuk VR. African iron overload. Semin Hematol. 2002;39:263–269. doi: 10.1053/shem.2002.35636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Loreal O, Gosriwatana I, Guyader D, Porter J, Brissot P, Hider RC. Determination of non-transferrin-bound iron in genetic hemochromatosis using a new HPLC-based method. J Hepatol. 2000;32:727–733. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80240-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen FE, Ooi C, Ha SY, Cheung BM, Todd D, Liang R, Chan TK, Chan V. Genetic and clinical features of hemoglobin H disease in Chinese patients. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:544–550. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200008243430804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Olivieri NF. Progression of iron overload in sickle cell disease. Semin Hematol. 2001;38:57–62. doi: 10.1016/s0037-1963(01)90060-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bottomley SS. Iron overload in sideroblastic and other non-thalassemic anemias. In: Barton JC, Edwards CQ, editors. Hemochromatosis: genetics, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2001. pp. 442–467. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Quinn CT, Rogers ZR, Buchanan GR. Survival of children with sickle cell disease. Blood. 2004;103:4023–4027. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-11-3758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Steinberg MH. Management of sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1021–1030. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199904013401307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Serjeant GR, Serjeant BE. Sickle cell disease. 3. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fleming MD. The genetics of inherited sideroblastic anemias. Semin Hematol. 2002;39:270–281. doi: 10.1053/shem.2002.35637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zager RA, Johnson AC, Hanson SY, Wasse H. Parenteral iron formulations: a comparative toxicologic analysis and mechanisms of cell injury. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;40:90–103. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2002.33917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Don BR, Rodriguez RA, Humphreys MH. Serum ferritin is a marker of morbidity and mortality in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;37:564–572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kletzmayr J, Horl WH. Iron overload and cardiovascular complications in dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17(Suppl 2):25–29. doi: 10.1093/ndt/17.suppl_2.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Engle JP, Polin KS, Stile IL. Acute iron intoxication: treatment controversies. Drug Intell Clin Pharm. 1987;21:153–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tenenbein M, Kopelow ML, deSa DJ. Myocardial failure and shock in iron poisoning. Human Toxicol. 1988;7:281–284. doi: 10.1177/096032718800700310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fine JS. Iron poisoning. Curr Probl Pediatr. 2000;30:71–90. doi: 10.1067/mps.2000.104055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vulpe CD, Kuo YM, Murphy TL, Cowley L, Askwith C, Libina N, Gitschier J, Anderson GJ. Hephaestin, a ceruloplasmin homologue implicated in intestinal iron transport, is defective in the sla mouse. Nat Genet. 1999;21:195–199. doi: 10.1038/5979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Robb A, Wessling-Resnick M. Regulation of transferrin receptor 2 protein levels by transferrin. Blood. 2004;104:4294–4299. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-06-2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Johnson MB, Enns CA. Diferric transferrin regulates transferrin receptor 2 protein stability. Blood. 2004;104:4287–4293. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-06-2477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gunshin H, Mackenzie B, Berger UV, Gunshin Y, Romero MF, Boron WF, Nussberger S, Gollan JL, Hediger MA. Cloning and characterization of a mammalian proton-coupled metal-ion transporter. Nature. 1997;388:482–488. doi: 10.1038/41343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gunshin H, Allerson CR, Polycarpou-Schwarz M, Rofts A, Rogers JT, Kishi F, Hentze MW, Rouault TA, Andrews NC, Hediger MA. Iron-dependent regulation of the divalent metal ion transporter. FEBS Lett. 2001;509:309–316. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)03189-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ke Y, Chen YY, Chang YZ, Duan XL, Ho KP, Jiang de H, Wang K, Qian ZM. Post-transcriptional expression of DMT1 in the heart of rat. J Cell Physiol. 2003;196:124–130. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Quigley JG, Yang Z, Worthington MT, Phillips JD, Sabo KM, Sabath DE, Berg CL, Sassa S, Wood BL, Abkowitz JL. Identification of a human heme exporter that is essential for erythropoiesis. Cell. 2004;118:757–766. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Thomas C, Oates PS. Ferroportin/IREG-1/MTP-1/SLC40A1 modulates the uptake of iron at the apical membrane of enterocytes. Gut. 2004;53:44–49. doi: 10.1136/gut.53.1.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Scheiber-Mojdehkar B, Lutzky B, Schaufler R, Sturm B, Goldenberg H. Non-transferrin-bound iron in the serum of hemodialysis patients who receive ferric saccharate: no correlation to peroxide generation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:1648–1655. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000130149.18412.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Parkes JG, Olivieri NF, Templeton DM. Characterization of Fe2+ and Fe3+ transport by iron-loaded cardiac myocytes. Toxicology. 1997;117:141–151. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(96)03566-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lansman JB, Hess P, Tsien RW. Blockade of current through single calcium channels by Cd2+, Mg2+, and Ca2+. Voltage and concentration dependence of calcium entry into the pore. J Gen Physiol. 1986;88:321–347. doi: 10.1085/jgp.88.3.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Winegar BD, Kelly R, Lansman JB. Block of current through single calcium channels by Fe, Co, and Ni. Location of the transition metal binding site in the pore. J Gen Physiol. 1991;97:351–367. doi: 10.1085/jgp.97.2.351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Atar D, Backx PH, Appel MM, Gao WD, Marban E. Excitation–transcription coupling mediated by zinc influx through voltage-dependent calcium channels. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:2473–2477. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.6.2473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tsushima RG, Wickenden AD, Bouchard RA, Oudit GY, Liu PP, Backx PH. Modulation of iron uptake in heart by L-type Ca2+ channel modifiers: possible implications in iron overload. Circ Res. 1999;84:1302–1309. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.11.1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Townsend A, Drakesmith H. Role of HFE in iron metabolism, hereditary haemochromatosis, anaemia of chronic disease, and secondary iron overload. Lancet. 2002;359:786–790. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07885-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Laftah AH, Ramesh B, Simpson RJ, Solanky N, Bahram S, Schumann K, Debnam ES, Srai SK. Effect of hepcidin on intestinal iron absorption in mice. Blood. 2004;103:3940–3944. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ludwiczek S, Theurl I, Bahram S, Schumann K, Weiss G. Regulatory networks for the control of body iron homeostasis and their dysregulation in HFE mediated hemochromatosis. J Cell Physiol. 2005;204:489–499. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yamaji S, Sharp P, Ramesh B, Srai SK. Inhibition of iron transport across human intestinal epithelial cells by hepcidin. Blood. 2004;104:2178–2180. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-0829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Muckenthaler M, Roy CN, Custodio AO, Minana B, deGraaf J, Montross LK, Andrews NC, Hentze MW. Regulatory defects in liver and intestine implicate abnormal hepcidin and Cybrd1 expression in mouse hemochromatosis. Nat Genet. 2003;34:102–107. doi: 10.1038/ng1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Celec P. Hemojuvelin: a supposed role in iron metabolism one year after its discovery. J Mol Med. 2005;83:521–525. doi: 10.1007/s00109-005-0668-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Niederkofler V, Salie R, Arber S. Hemojuvelin is essential for dietary iron sensing, and its mutation leads to severe iron overload. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2180–2186. doi: 10.1172/JCI25683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ward RJ, Kuhn LC, Kaldy P, Florence A, Peters TJ, Crichton RR. Control of cellular iron homeostasis by iron-responsive elements in vivo. Eur J Biochem. 1994;220:927–931. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb18696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pantopoulos K. Iron metabolism and the IRE/IRP regulatory system: an update. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1012:1–13. doi: 10.1196/annals.1306.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Meyron-Holtz EG, Ghosh MC, Rouault TA. Mammalian tissue oxygen levels modulate iron-regulatory protein activities in vivo. Science. 2004;306:2087–2090. doi: 10.1126/science.1103786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Olivieri NF, Nathan DG, MacMillan JH, Wayne AS, Liu PP, McGee A, Martin M, Koren G, Cohen AR. Survival in medically treated patients with homozygous beta-thalassemia. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:574–578. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199409013310903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Brittenham GM, Griffith PM, Nienhuis AW, McLaren CE, Young NS, Tucker EE, Allen CJ, Farrell DE, Harris JW. Efficacy of deferoxamine in preventing complications of iron overload in patients with thalassemia major. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:567–573. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199409013310902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zurlo MG, De Stefano P, Borgna-Pignatti C, Di Palma A, Piga A, Melevendi C, Di Gregorio F, Burattini MG, Terzoli S. Survival and causes of death in thalassaemia major. Lancet. 1989;2:27–30. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90264-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Niederau C, Fischer R, Purschel A, Stremmel W, Haussinger D, Strohmeyer G. Long-term survival in patients with hereditary hemochromatosis. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:1107–1119. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8613000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cecchetti G, Binda A, Piperno A, Nador F, Fargion S, Fiorelli G. Cardiac alterations in 36 consecutive patients with idiopathic haemochromatosis: polygraphic and echocardiographic evaluation. Eur Heart J. 1991;12:224–230. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a059873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Muhlestein JB. Cardiac abnormalities in hemochromatosis. In: Barton JC, Edwards CQ, editors. Hemochromatosis: genetics, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2000. pp. 297–310. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Palka P, Macdonald G, Lange A, Burstow DJ. The role of Doppler left ventricular filling indexes and Doppler tissue echocardiography in the assessment of cardiac involvement in hereditary hemochromatosis. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2002;15:884–890. doi: 10.1067/mje.2002.118032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Modell B, Khan M, Darlison M. Survival in beta-thalassaemia major in the UK: data from the UK Thalassaemia Register. Lancet. 2000;355:2051–2052. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02357-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Veglio F, Melchio R, Rabbia F, Molino P, Genova GC, Martini G, Schiavone D, Piga A, Chiandussi L. Blood pressure and heart rate in young thalassemia major patients. Am J Hypertens. 1998;11:539–547. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(97)00263-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kremastinos DT, Tsiapras DP, Tsetsos GA, Rentoukas EI, Vretou HP, Toutouzas PK. Left ventricular diastolic Doppler characteristics in beta-thalassemia major. Circulation. 1993;88:1127–1135. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.3.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Buja LM, Roberts WC. Iron in the heart. Etiology and clinical significance. Am J Med. 1971;51:209–221. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(71)90240-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mattheyses M, Hespel JP, Brissot P, Daubert JC, Hita de Nercy Y, Lancien G, Le Treut A, Pony JC, Simon M, Ferrand B, Gouffault J, Bourel M. The cardiomyopathy of idiopathic hemochromatosis. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss. 1978;71:371–379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Rosenqvist M, Hultcrantz R. Prevalence of a haemochromatosis among men with clinically significant bradyarrhythmias. Eur Heart J. 1989;10:473–478. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a059512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Laurita KR, Chuck ET, Yang T, Dong WQ, Kuryshev YA, Brittenham GM, Rosenbaum DS, Brown AM. Optical mapping reveals conduction slowing and impulse block in iron-overload cardiomyopathy. J Lab Clin Med. 2003;142:83–89. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2143(03)00060-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Eaton JW, Qian M. Molecular bases of cellular iron toxicity. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;32:833–840. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00772-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kadiiska MB, Burkitt MJ, Xiang QH, Mason RP. Iron supplementation generates hydroxyl radical in vivo. An ESR spin-trapping investigation. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:1653–1657. doi: 10.1172/JCI118205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Young IS, Trouton TG, Torney JJ, McMaster D, Callender ME, Trimble ER. Antioxidant status and lipid peroxidation in hereditary haemochromatosis. Free Radic Biol Med. 1994;16:393–397. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(94)90041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Livrea MA, Tesoriere L, Pintaudi AM, Calabrese A, Maggio A, Freisleben HJ, D'Arpa D, D'Anna R, Bongiorno A. Oxidative stress and antioxidant status in beta-thalassemia major: iron overload and depletion of lipid-soluble antioxidants. Blood. 1996;88:3608–3614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lim PS, Chan EC, Lu TC, Yu YL, Kuo SY, Wang TH, Wei YH. Lipophilic antioxidants and iron status in ESRD patients on hemodialysis. Nephron. 2000;86:428–435. doi: 10.1159/000045830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Esterbauer H, Schaur RJ, Zollner H. Chemistry and biochemistry of 4-hydroxynonenal, malonaldehyde and related aldehydes. Free Radic Biol Med. 1991;11:81–128. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(91)90192-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lee SH, Oe T, Blair IA. Vitamin C-induced decomposition of lipid hydroperoxides to endogenous genotoxins. Science. 2001;292:2083–2086. doi: 10.1126/science.1059501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Valenti L, Conte D, Piperno A, Dongiovanni P, Fracanzani AL, Fraquelli M, Vergani A, Gianni C, Carmagnola L, Fargion S. The mitochondrial superoxide dismutase A16V polymorphism in the cardiomyopathy associated with hereditary haemochromatosis. J Med Genet. 2004;41:946–950. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.019588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]