Abstract

Background

Lung cancer (lc) is a complex disease requiring coordination of multiple health care professionals. A recently implemented lc multidisciplinary clinic (mdc) at Kingston Health Sciences Centre, an academic tertiary care hospital, improved timeliness of oncology assessment and treatment. This study describes patient, caregiver, and physician experiences in the mdc.

Methods

We qualitatively studied patient, caregiver, and physician experiences in a traditional siloed care model and in the mdc model. We used purposive sampling to conduct semi-structured interviews with patients and caregivers who received care in one of the models and with physicians who worked in both models. Thematic design by open coding in the ATLAS.ti software application (ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development, Berlin, Germany) was used to analyze the data.

Results

Participation by 6 of 72 identified patients from the traditional model and 6 of 40 identified patients from the mdc model was obtained. Of 9 physicians who provided care in both models, 8 were interviewed (2 respirologists, 2 medical oncologists, 4 radiation oncologists). Four themes emerged: communication and collaboration, efficiency, quality of care, and effect on patient outcomes. Patients in both models had positive impressions of their care. Patients in the mdc frequently reported convenience and a positive effect of family presence at appointments. Physicians reported that the mdc improved communication and collegiality, clinic efficiency, patient outcomes and satisfaction, and consistency of information provided to patients. Physicians identified lack of clinic space as an area for mdc improvement.

Conclusions

This qualitative study found that a lc mdc facilitated patient communication and physician collaboration, improved quality of care, and had a perceived positive effect on patient outcomes.

Keywords: Quality of care, multidisciplinary models, process improvement, lung cancer, patient experiences

INTRODUCTION

Lung cancer (lc) is the leading cause of cancer-related mortality, with a 5-year survival of less than 20%1. Delays in lc diagnosis and management are common2,3 and have been attributed in part to the complexity of lc care, which requires the coordination of a diverse group of physicians, including respirologists, medical and radiation oncologists, and thoracic surgeons4,5. Unfortunately, delays in care can lead to tumour progression6 and patient distress7,8.

Multidisciplinary clinic (mdc) models have demonstrated effectiveness in patient management for other cancer types9,10. Unfortunately, mdcs are uncommon in lc care5, and until recently, there has been a paucity of data supporting their implementation for this patient group11,12. However, evidence is increasingly showing that lc mdcs might improve care coordination, communication between providers, and compliance with guidelines, and might reduce delays in diagnosis and treatment11–14. Nonetheless, development and implementation of lc mdc models have been limited by a scarcity of literature identifying optimal clinic characteristics and structures, ideal mixes of specialist and allied health providers, and implementation strategies2,5,12,15. Evaluation of lc mdcs is limited by the heterogeneity of existing models and the challenges in defining essential components12,16,17. Additionally, very few studies have evaluated the effect of lc mdcs on patient and health care provider experiences5,12,18. A better understanding of those experiences can help to inform the development of such care models.

The Kingston Health Sciences Centre (khsc) recently implemented a lc mdc that reduced the time from lc diagnosis to oncology assessment by 10 days and the time to treatment by 25 days14. Time to treatment improved substantially (more than time to oncology assessment), which was hypothesized to be attributable to improved provider communication and real-time collaborative physician management discussions. To further study the potential benefits and drawbacks of the mdc, we collected patient, caregiver, and health care provider experiences within that care model.

METHODS

Context

As an academic tertiary care centre, khsc serves a predominantly rural catchment area of more than 500,000 people. The region served by khsc sees 600–700 new lc patients annually, 60% of whom are managed through the Lung Diagnostic Assessment Program (ldap), a rapid assessment clinic responsible for the management of patients from initial suspicion of malignant disease to diagnosis. At khsc, approximately 75% of patients with suspected lc are seen by a respirologist in the ldap; the remaining 25% with suspected operable disease are triaged directly to a parallel thoracic surgery clinic. The region served by khsc has the lowest 5-year lc survival in the province of Ontario, at 15.0% in 201719.

Intervention

Within the ldap, we implemented a weekly mdc involving respirologists, medical oncologists, and radiation oncologists. Patients with a new lc diagnosis were offered concurrent, same-visit oncology consultation. Physicians participated in the weekly mdc on a rotating schedule, with a usual attendance of at least 1 physician per specialty, and a minimum attendance of 1 respirologist and 1 oncologist. At every mdc, physicians met in a short case conference to do an advance chart review for patients booked into the clinic, to discuss the need for oncology consultation, and to begin to develop management plans. Stone et al.14 summarized the details of the mdc implementation and improvement process.

Study of the Interventions

When designing the present study, we planned to correlate our previously documented and published improvements in timeliness of care14 with patient and provider experiences in the mdc. Our expectation was that reducing siloed care would improve the patient and caregiver experience. We therefore conducted a qualitative research study and adopted an exploratory design20 to describe patient, caregiver, and health care provider experiences in a traditional model of care compared with the mdc.

Eligible patients in the mdc model were those who had received a new diagnosis of lc of any stage (i–iv) after having undergone investigations coordinated by an ldap respirologist and who were returning to the mdc (February 2017 onward), where at least 2 physician assessments took place (respirologist plus at least 1 oncologist). Patients recruited from the traditional model of care were seen by a respirologist either within the 3 months before mdc implementation (November 2016 to January 2017) or after mdc implementation (February 2017), but outside the mdc model (usually because of scheduling conflicts). In all cases, the primary caregivers of the patients were invited to participate in interviews. A random number generator was used to create a randomized list of patients from the database of those who had been assessed at the ldap of the Cancer Centre of Southeastern Ontario. Patients who were deceased, who had moved, or who had a non-lc diagnosis were excluded (supplementary Figure 1). One researcher (GL) contacted patients initially with a letter in the mail, followed by a telephone call inviting participation. One researcher (RE) used e-mail messages to invite the participation of all physicians involved in the mdc. The study was approved by the Queen’s University Health Sciences and Affiliated Hospitals Research Ethics Board.

Data Collection

Before leading the patient and caregiver interviews, a team of 4 researchers received training on how to conduct qualitative research. One researcher (RE) conducted the physician interviews and focus group. Interview protocols for patients and physicians were informed by a systematic review previously published by our research team12 and were developed through team discussion and consensus. To mitigate bias and address reflexivity21, researchers involved in the development, design, or implementation of the mdc did not conduct interviews. However, 1 researcher (GCD) was a focus group participant, and 1 researcher (AR) was an interview participant. Both GCD and AR were physicians in the mdc. Two researchers (CJLS, GCD) had been involved in quantitative data collection and analysis of the mdc. All team members were aware of the improved timeliness of care demonstrated in the mdc model. To allow for arm’s length discussion and to reduce power differentials, health care providers were interviewed by a qualitative researcher without a medical background (RE). All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. We reached data saturation when no new information was collected from the interviews. Pseudonyms replaced all identifying information before data analysis.

Patient and Caregiver Interviews

We used purposive sampling22 to ensure that data were obtained from patients who met the inclusion criteria [supplementary Figure 1(A)]. Interviewers coordinated the interview, obtained written consent, and met with the patient with or without their caregiver for an in-person interview in a secure confidential location. The semi-structured interviews used questions designed to elicit information from patients and caregivers about their lc journey, the process, and their perceptions of the quality of their care [supplemental Appendix 1(A)]. Interviews lasted between 30 and 60 minutes.

Physician Interviews

Convenience sampling was used to invite physician participants. The original plan was to conduct physician focus groups for each subspecialty to ensure freedom to discuss challenges in synchronous care coordination between specialties. However, because of scheduling difficulties, one “focus group” (labelled as such for the purposes of this paper) was conducted with 2 respirologists in the form of a joint interview (approximately 60 minutes in duration), and all medical and radiation oncologists were interviewed independently. The same open-ended interview protocol was used for the focus group and for the individual physician interviews. Interview questions focused on the barriers and challenges in the mdc, recommendations for the mdc, and perceptions of effects on patient care and health outcomes [supplemental Appendix 1(B)].

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using an inductive thematic design20. We first immersed ourselves in the data by having 3 researchers (ACB, GCD, ND) read 1 patient and 1 physician transcript. Transcripts were coded using open coding in the ATLAS.ti qualitative data analysis software application (version 8: ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development, Berlin, Germany). To ensure interrater reliability, codes were then compared. When differences arose between the researchers, a discussion ensued until a shared meaning of the codes and consensus was reached. A codebook was developed, and 1 researcher (ACB) coded the remaining transcripts, with new codes added as additional interviews were conducted and new viewpoints emerged. Coding the transcripts occurred throughout the data collection process. Once all transcripts were coded, the research team met to discuss the codes, to determine subthemes, and to identify overarching emergent themes. Using comparative analysis23, we identified commonalities and differences between the participant groups as they related to each theme.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

For the specified time frames, we identified from the database 182 patients seen in the traditional model of care and 77 patients seen in the mdc model of care. A random number generator was used to identify 72 patients from the traditional model and 40 patients from mdc model to serve as our contact list, with many patients excluded before contact for the reasons outlined in supplementary Figure 1(A,B). The remaining 15 patients in the traditional model and 25 patients in the mdc model served as our final contact list. Interviews were conducted with 6 patients from each model. Table I presents the demographics of the interviewed patients.

TABLE I.

Demographics of the interviewed patients

| Variable | Model | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Traditional | MDC | |

| Patients interviewed (n) | 6 | 6 |

| Caregiver included in interview [n (%)] | 5 (83.3) | 4 (66.7) |

|

| ||

| Patient age (years) | ||

| Mean | 71 | 72 |

| Range | 52–79 | 50–82 |

|

| ||

| Sex (n) | ||

| Men | 5 | 3 |

| Women | 1 | 3 |

|

| ||

| Distance from KHSC [n (%)] | ||

| <50 km | 2 (33.3) | 2 (33.3) |

| 50–100 km | 4 (66.7) | 3 (50) |

| >100 km | 0 | 1 (16.7) |

|

| ||

| Lung cancer stage [n (%)] | ||

| I | 2 (33.3) | 3 (50) |

| II | 0 | 0 |

| III | 1 (16.7) | 0 |

| IV | 3 (50) | 3 (50) |

|

| ||

| Lung cancer pathology [n (%)] | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 1 (16.7) | 4 (66.7) |

| Squamous | 2 (33.3) | 0 |

| Small-cell | 1 (16.7) | 1 (16.7) |

| Carcinoid | 0 | 1 (16.7) |

| Unknown or not biopsied | 2 (33.3) | 0 |

|

| ||

| Lung cancer treatment [n (%)] | ||

| Radiation therapy | 3 (50.0) | 5 (83.3) |

| Systemic therapy | 3 (50) | 1 (16.7) |

| Both radiation and systemic therapy | 1 (16.7) | 2 (33.3) |

MDC = multidisciplinary clinic; KHSC = Kingston Health Sciences Centre.

Of 9 physicians who had participated in the mdc clinic at the time of study recruitment, 8 (88.9%) agreed to participate in the qualitative study, including 2 respirologists, 2 medical oncologists, and 4 radiation oncologists.

The analysis resulted in 57 codes, which were grouped into 12 subthemes, from which 4 overarching themes emerged. Those themes were communication and collaboration, efficiency, quality of patient care, and effects on patient outcomes.

We identified each interview and focus group participant using pseudonyms: MDC1–6 for patients treated in the mdc model, T1–6 for patients treated in the traditional model patient, FG1 for the respirologist focus group, MO1 and MO2 for the medical oncologists, and RO1–4 for the radiation oncologists. Tables II–V identify selected quotations for each subtheme identified.

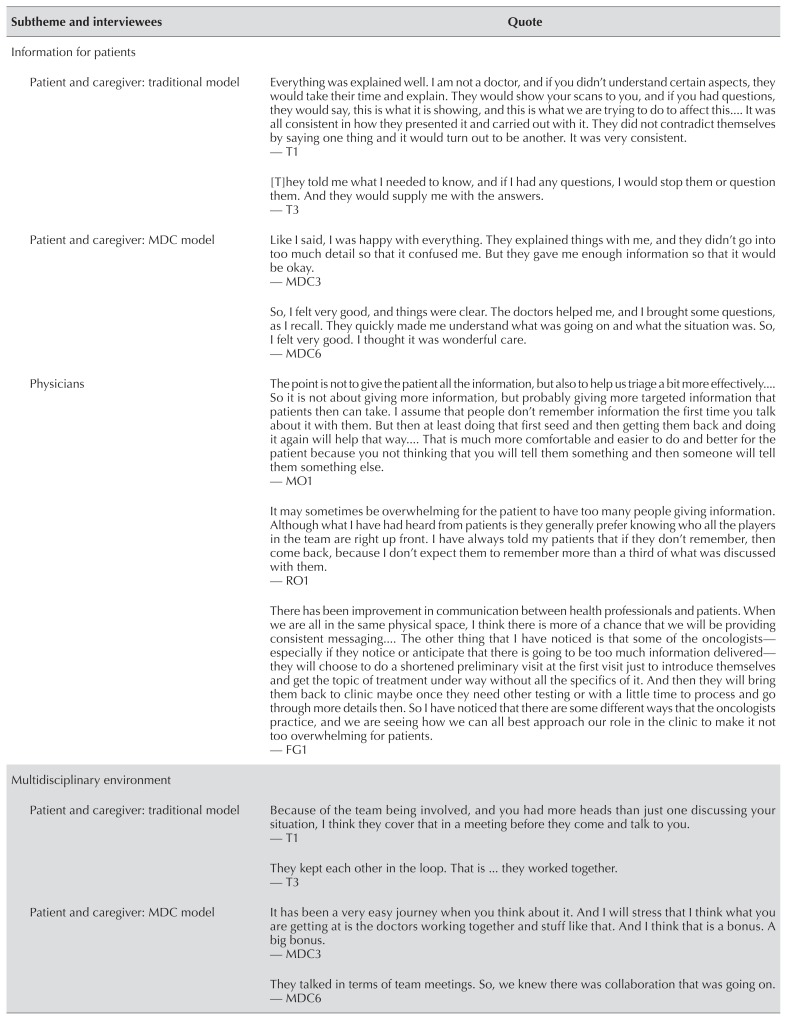

TABLE II.

Theme 1: Communication and collaboration—selected patient, caregiver, and physician quotes

| Subtheme and interviewees | Quote |

|---|---|

| Information for patients | |

| Patient and caregiver: traditional model | Everything was explained well. I am not a doctor, and if you didn’t understand certain aspects, they would take their time and explain. They would show your scans to you, and if you had questions, they would say, this is what it is showing, and this is what we are trying to do to affect this It was all consistent in how they presented it and carried out with it. They did not contradict themselves by saying one thing and it would turn out to be another. It was very consistent. — T1 [T]hey told me what I needed to know, and if I had any questions, I would stop them or question them. And they would supply me with the answers. — T3 |

| Patient and caregiver: MDC model | Like I said, I was happy with everything. They explained things with me, and they didn’t go into too much detail so that it confused me. But they gave me enough information so that it would be okay. — MDC3 So, I felt very good, and things were clear. The doctors helped me, and I brought some questions, as I recall. They quickly made me understand what was going on and what the situation was. So, I felt very good. I thought it was wonderful care. — MDC6 |

| Physicians | The point is not to give the patient all the information, but also to help us triage a bit more effectively So it is not about giving more information, but probably giving more targeted information that patients then can take. I assume that people don’t remember information the first time you talk about it with them. But then at least doing that first seed and then getting them back and doing it again will help that way That is much more comfortable and easier to do and better for the patient because you not thinking that you will tell them something and then someone will tell them something else. — MO1 It may sometimes be overwhelming for the patient to have too many people giving information. Although what I have had heard from patients is they generally prefer knowing who all the players in the team are right up front. I have always told my patients that if they don’t remember, then come back, because I don’t expect them to remember more than a third of what was discussed with them. — RO1 There has been improvement in communication between health professionals and patients. When we are all in the same physical space, I think there is more of a chance that we will be providing consistent messaging The other thing that I have noticed is that some of the oncologists— especially if they notice or anticipate that there is going to be too much information delivered— they will choose to do a shortened preliminary visit at the first visit just to introduce themselves and get the topic of treatment under way without all the specifics of it. And then they will bring them back to clinic maybe once they need other testing or with a little time to process and go through more details then. So I have noticed that there are some different ways that the oncologists practice, and we are seeing how we can all best approach our role in the clinic to make it not too overwhelming for patients. — FG1 |

|

| |

| Multidisciplinary environment | |

| Patient and caregiver: traditional model | Because of the team being involved, and you had more heads than just one discussing your situation, I think they cover that in a meeting before they come and talk to you. — T1 They kept each other in the loop. That is ... they worked together. — T3 |

| Patient and caregiver: MDC model | It has been a very easy journey when you think about it. And I will stress that I think what you are getting at is the doctors working together and stuff like that. And I think that is a bonus. A big bonus. — MDC3 They talked in terms of team meetings. So, we knew there was collaboration that was going on. — MDC6 |

| Physicians | It has allowed earlier multidisciplinary care so you get the right answer for the patient quicker. So the quality goes up. Because lung cancer is a dynamic disease. It changes over time, and so the earlier that you avoid mistakes and see patients the better. — MO1 So the treatment plans are often multidisciplinary, and so it allows us to have a direct conversation and look at the imaging together. And I can ask a pulmonologist and say, “Can you sample these lymph nodes for me?” And they can tell me then and there if it is possible or not. Or instead of me having to wait 2 weeks to find out that the patient is not going to get [chemotherapy] which impacts what I do from the radiation standpoint. I can ask the medical oncologist then and there if they will give [chemotherapy] or not, and when they will start? — RO4 I think that is as an opportunity for health care providers ... to take us out of those silos and to a more multidisciplinary fashion. — FG1 |

|

| |

| Communication between physicians | |

| Physicians | From a quality perspective, it has allowed communication between the specialists involved— pulmonologists and radiation oncologists and medical oncologists is significantly better in real time than in waiting for notes to be transcribed and trying to figure out what people are thinking and so on and so forth. — MO1 So that is also a big advantage, where we have a dialogue amongst the three physician groups, and we will basically determine So instead of waiting for a free moment or sending out an e-mail or waiting until tumour board ... you can say, what are your thoughts on this patient? So, you can ... Some of the treatment decisions made are very dependent on what our colleagues say about the patients I think, for the medical oncologist, myself, we are both approaching this from a therapeutic decision-making perspective. So, we will talk to the pulmonologist and say, “What do you think about this aspect of the patient?” And that feedback will help us make a clinical treatment decision. And between medical and radiation oncology, we will say, “Based upon this, here are my thoughts. What do you think?” And we can have a bit of dialogue and come up with the treatment plan faster, as I mentioned before. — RO2 |

|

| |

| Improving collegial relationships | |

| Physicians | It [the MDC] has been great for building a relationship and building understanding. We educate each other on what we do and what we need and what is possible. — RO2 I think from a quality-of-care perspective, it has strengthened our relationships with our oncology colleagues, too. Where we communicate more with them and work a lot more with them and that has helped us to be a better team as well. — FG1 |

T1–6 = patients seen in the traditional model; MDC1–6 = patients seen in the multidisciplinary clinic (MDC) model; MO1–2 = medical oncologists; RO1–4 = radiation oncologists; FG1 = focus group (2 respirologists).

TABLE V.

Theme 4: Impact on Patient Outcomes—selected physician quotes

| But maybe access to care and some patients maybe even being referred for workup. I can see a big improvement for the whole community just to know that there is [the MDC]. I am on call for oncology, and I get a lot of calls from family doctors who say they have a patient with a lung mass, and they want to know where to send them. So just to know where to send the patient. The benefits are more qualitative rather than quantitative. I don’t think survival will be impacted that much, but some quality indicators like time to see an oncologist and time to start treatment. Those, in my mind, are the biggest improvements. — MO2 |

| As I have said earlier, it potentially avoids unnecessary tests, and that has a big impact on patients as well. It will save them traveling to Ottawa or Toronto for a PET scan. And so, there is the quality of life component. — RO1 |

| I like to think that, if we can initiate treatment sooner, then our outcomes will potentially be better. We know that, in some disease sites, delays in treatment result in worse outcomes. So, if I can see the patient a week after their PET scan is done instead of a month after it is done, I would like to think that there is less chance for the tumour to grow, and my curative potential is better But I think we have an opportunity to issue treatment sooner, which I think will hopefully lead to better outcomes. And also, if we can issue palliative treatment sooner, we can try to improve quality of life sooner as well. — RO2 |

| What we know from the data is that there has been a reduction in time to treatment from an average of 40 days to 20 days. And even less in some months, when things are running really smoothly. What we don’t know yet is how that will translate to long-term health outcomes such as survival and quality of life and stuff like that, because it is driven by so many pieces of puzzle in lung cancer care. — FG1 |

MO1–2 = medical oncologists; PET = positron-emission tomography; RO1–4 = radiation oncologists; FG1 = focus group (2 respirologists).

Theme 1: Communication and Collaboration

The Communication and Collaboration theme describes interactions between physicians and patients, and also those between physician specialties, including information provided to patients (Table II).

Information Provided to Patients

All patients seen in the mdc described receiving sufficient information, having it explained in a way that helped them to understand their illness, and receiving consistent information between physicians (MDC3, MDC6). Of the 6 patients in the traditional model, 5 also spoke about receiving sufficient and consistent information (T1, T3). One patient seen in the traditional model (T2) spoke of receiving disjointed information and receiving the news of their diagnosis without further information about next steps, although this patient’s circumstances were unique in that transfer to the emergency room from the clinic was required, and the individual expressed dissatisfaction about being “seen by several doctors” there. Notably, 2 physicians spoke of consistent messaging (FG1, MO1), and 6 spoke about providing focused information to patients to avoid overwhelming them (MO1, RO1, FG1).

Multidisciplinary Environment

All patients in the mdc model and 5 patients in the traditional model felt that that their physicians operated as a team (MDC3, MDC6, T1, T3), given their observations that physicians were working and meeting together on their plan of care. Of the physicians, 6 discussed the benefits of working in a multidisciplinary environment and the effect it had on removing professional silos (MO1, RO4, FG1).

Communication Between Physicians

All physicians reported perceived improvements in communication with each other in the mdc model, repeatedly referencing their ability to have synchronous communication with the other physician specialists (MO1, RO2).

Improving Collegial Relationships

The respirologists and 2 radiation oncologists believed that the clinic improved collegial relationships through a better understanding and appreciation of each other’s roles and responsibilities—facilitating peer education and helping to develop treatment plans as a team (RO2, FG1).

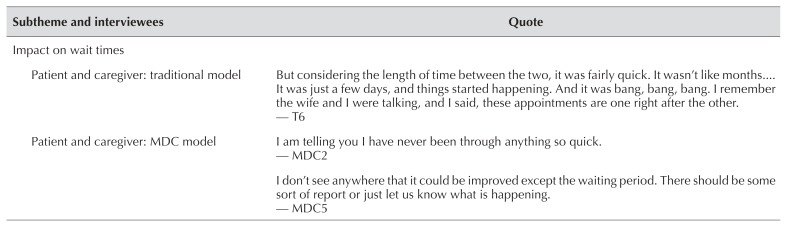

Theme 2: Efficiency

The Efficiency theme identifies perceived changes in efficiency because of the mdc (Table III). Patients and physicians in the mdc model discussed wait times for cancer diagnoses and treatment. Physicians also discussed improvements to work efficiency.

TABLE III.

Theme 2: Efficiency selected patient, caregiver, and physician quotes

| Subtheme and interviewees | Quote |

|---|---|

| Impact on wait times | |

| Patient and caregiver: traditional model | But considering the length of time between the two, it was fairly quick. It wasn’t like months It was just a few days, and things started happening. And it was bang, bang, bang. I remember the wife and I were talking, and I said, these appointments are one right after the other. — T6 |

| Patient and caregiver: MDC model | I am telling you I have never been through anything so quick. — MDC2 I don’t see anywhere that it could be improved except the waiting period. There should be some sort of report or just let us know what is happening. — MDC5 |

| Physicians | In terms of quality of care, I think what is the most improvement is the time they wait to see a medical oncologist. I also think that starting treatment for patients who are seen in the LDAP clinic is also improved. So the time not just to see the oncologist, but to start treatment. So those are the two big quality improvements from my point of view. — MO2 My experience is that I am getting patients onto the simulator quickly and getting them treated quicker as well. — RO1 Well, the shortened time to actually see an oncologist and overall shortening of the diagnostic pathway times I think improves patient care. — FG1 |

|

| |

| Seeing more patients per clinic | |

| Physicians | From a radiation point of view, I think they see it as getting patients into treatment earlier ... so again, the triage piece, where hopefully having [fewer] patients booked in through the emergency department and so on. — MO1 It has increased efficiency of use of clinic time and allows me to see a large number of patients in a single clinic. Some of that is a function of [Hotel Dieu Hospital] versus [Kingston General Hospital] processes. — RO1 Note: Hotel Dieu Hospital is the location of the MDC clinic; oncologists typically see patients in the Cancer Centre at Kingston General Hospital. The other thing that I have had some of them comment on is that they actually enjoy the clinic because they like being able to see in an efficient way ... that a physician has already pre-screened and problems that have arisen since the last visit, and they have a fresh update. So they can just go in and talk about their piece of the puzzle instead of starting from fresh. So they know where we have left off, and they can take the ball from there instead of having to start from scratch. — FG1 |

T1–6 = patients seen in the traditional model; MDC1–6 = patients seen in the multidisciplinary clinic (MDC) model; LDAP = Lung Diagnostic Assessment Program; MO1–2 = medical oncologists; RO1–4 = radiation oncologists; FG1 = focus group (2 respirologists).

Effect on Wait Times

One patient in the mdc described their journey as being quick (MDC2). Another mdc patient reported frustration with waiting for tests between appointments and believed that it took too long to start treatment (MDC5). Of the patients in the traditional model, 4 also acknowledged that appointments, testing, and treatment start happened quickly (T6), although 1 of those patients (T3) later expressed a feeling that there “was a lot of hurry up and wait” with regard to completion of testing, receipt of test results, and formulation of a management plan. All 3 physician groups (all physicians) believed that the mdc reduced wait times to see oncologists, shortened time to diagnosis, and reduced time to treatment (MO2, RO1, FG1).

Seeing More Patients per Clinic

All 3 physician groups (6 physicians) spoke about the perceived increased efficiency in having only 1 nursing assessment or preliminary screening completed for the 3 physician assessments (MO1, RO1, FG1). The radiation oncologists specifically believed that the mdc clinic increased the number of patients they could see in clinic because of more efficient nursing assessments and improved patient flow.

Theme 3: Quality of Patient Care

The Quality of Patient Care theme describes patient comfort, confidence, and satisfaction with care; the convenience of multiple same-day assessments; and the effects on the patient experience and availability of family support (Table IV).

TABLE IV.

Theme 3: Quality of Patient Care—selected patient, caregiver, and physician quotes

| Subtheme and interviewees | Quote |

|---|---|

| Patient comfort, confidence and satisfaction | |

| Patient and caregiver: traditional model | Actually, I was very confident in the doctors and everyone else who I talked to. — T5 Well, we are thankful for the program that he is in, but at the time of diagnosis, we are very thankful that we had LK here who was a spokesman for us. I am not sure we would be where we are today without him The medical team should be the advocate. — T2 I felt comfortable. I felt at ease. I found that people who looked after me in Belleville and in Kinston, I trusted them. I had a lot of trust ad faith in. And so, I was at ease in both places. — T6 |

| Patient and caregiver: MDC model | I was satisfied with everything that they did. They were very knowledgeable. They told me as it is, and what was going to happen to me You are going through something that you never expected to be going through. But I was quite comfortable But how they have approached it, and how they said it was great. And after the fact it is like, we have all the confidence in the world that we will know exactly what is going on and what stage we are at and everything. I don’t think we can say much better about these guys because the whole team ... it is hard to find anything. How can we improve? — MDC2 |

| Physicians | It has improved outcomes One is sort of reducing patient’s uncertainty, anxiety, quality of life and so on, where even if they don’t live any longer is still important. And I think that [has] likely been improved. — MO1 Once the patient knows that there is a suspected malignancy or cancer, there is a heightened level of anxiety for patients and the family. So, if the times are shortened, and they come to know about treatment plan, it is a huge stress reliever in a way, because otherwise they don’t know what is going to happen next. — RO3 And I think maybe a bit more confidence in the treatment team by hearing the consistent message. I think sometimes patients hear it from one person and then say, “Oh, I will see what someone else thinks. Maybe they got it wrong.” But I have seen that when it comes from 2 or 3 care providers they tend ... they have stopped me in the hallway and have said they appreciate the consistent message. And they hear it in different ways, and it sinks in a bit better than hearing it once. — FG1 |

|

| |

| Impact on family presence | |

| Patient and caregiver: traditional model | It was very convenient, and of course my daughter took me every time. She just had to ask for time off work. There wasn’t any problem. — T5 |

| Patient and caregiver: MDC model | Because you have your family with you and you take everything in on the one day instead of having to come back, and you hear something different, and then next time it is something different. You might as well just get it all done right then and there. — MDC4 |

| Physicians | Once the patient knows that there is a suspected malignancy or cancer, there is a heightened level of anxiety for patients and the family. So, if the times are shortened, and they come to know about treatment plan, it is a huge stress reliever in a way, because otherwise they don’t know what is going to happen next. — RO3 Again, it comes down to their family being present for the whole discussion and fewer trips in [to appointments]. — FG1 |

|

| |

| Impact of same-day assessments | |

| Patient and caregiver: traditional model | The only thing I would like to see is, when we come for appointments for someone else ... like we are not in treatment now, but to do with seeing Dr. X and Dr. Y ... so if the appointments could be together for anyone out of town. It is all right if you live five minutes from here. They try to do their best, but it doesn’t always work out. — T4 |

| Patient and caregiver: MDC model | [T]he radiation oncologist and the medicine oncologist were both there on the same day, so they could talk to the patients individually. It was a matter of convenience, and it was an intelligent way of doing business, in my opinion. As opposed to having appointments here and there and everywhere. — MDC1 |

| Physicians | So, if that is a limitation, then whether there is other clinic space available at [MDC] which would allow for a larger space where we could have enough computers for all of us and for learners who may want to participate as well It is probably reasonable to correct. — RO4 |

|

| |

| Meeting patient expectations | |

| Patient and caregiver: traditional model | I would not change anything. Everyone has been just fantastic with the way they have treated us and respect and know what you are going through. You didn’t feel like just another person that has troubles. I mean everyone has troubles, but you like to have someone at your side who is there to help you go through it. And that is what I felt through this process. Both of us. — T1 |

| Patient and caregiver: MDC model | They didn’t make us guess as to what was going to happen. They knew it, and they explained everything down to the letter. I had no qualms. I was fine with everything they did. If they told me to do this then I did it. — MDC2 |

T1–6 = patients seen in the traditional model; MDC1–6 = patients seen in the multidisciplinary clinic (MDC) model; MO1–2 = medical oncologists; RO1–4 = radiation oncologists; FG1 = focus group (2 respirologists).

Patient Comfort, Confidence, and Satisfaction

All patients seen in the mdc spoke about feeling confident and satisfied with their care and feeling comforted by having multiple physicians addressing their concerns (MDC2). Of the 6 patients seen in the traditional model, 5 also expressed feelings of comfort, confidence, and satisfaction with their care (T2, T5, T6). However, the 1 patient in the traditional model who required transfer to the emergency room from the clinic expressed significant concern over the perceived lack of advocacy in his treatment plan. All 3 physician groups (6 physicians) believed that the mdc increased patient comfort, confidence, and satisfaction. They also perceived an overall reduction in patient and provider anxiety about treatment and outcomes (MO1, RO3, FG1).

Effect on Family Presence

Of the patients seen in the traditional model, 3 commented on the need to coordinate with family members to make multiple trips to attend appointments, and 1 patient (T5) commented on a family member having to take time off work for that purpose. Meanwhile, all patients seen in the mdc model described how their families were able to physically attend appointments because of reduced time away from work and minimized travel time (MDC4). Of the physicians, 4 indicated that the mdc and same-day assessments would improve patient support by enabling caregiver accompaniment (RO3, FG1).

Effect of Same-Day Assessments

Of patients seen in the traditional model, 3 noted the inconvenience of multiple appointments on separate days (T4). Of patients seen in the mdc model, 5 expressed appreciation for same-day assessments (MDC1). A 6th patient seen in the mdc clinic required an additional physician assessment on another day and expressed no concern about making the additional trip. Of the physicians, 3 (RO4) commented on a lack of physical workspace and computer workstations and a need to redesign the workspace to suit the needs of multiple physicians working in the mdc clinic. The issue of space was not remarked upon by patients.

Meeting Patient Expectations

All patients seen in the mdc model found that the clinic met or exceeded their expectations for care (MDC2). Of patients seen in the traditional model, 5 also expressed overall satisfaction with their care (T1).

Theme 4: Effect on Patient Outcomes

The Effect on Patient Outcomes theme describes the predicted effect of the mdc as perceived by the physician groups (Table V).

Physician Predicted Effect

Each group of physicians expressed their views about how the mdc clinic could positively affect patient outcomes by reducing the time to oncology assessment and treatment (MO2, RO2, FG1). Many physicians also discussed the potential to improve resource use, including decreased testing and consolidation of appointments (RO1).

DISCUSSION

This study describes patient, caregiver, and health care provider experiences in a novel lc mdc model compared with a traditional siloed model of care. We identified 4 themes from our interviews: communication and collaboration, efficiency, quality of patient care, and effect on patient outcomes. Patients in both care models had, overall, a very positive impression of their care. Patients seen at the mdc consistently reported the convenience of consolidating multiple physician assessments into one visit and the positive effect that consolidation had on facilitating caregiver presence at appointments. Our results are consistent with a previous study by Kedia et al.13 of patients with lc and their caregivers in a mdc model, which found that the mdc improved physician collaboration and patient convenience, while reducing patient confusion and anxiety and decreasing test redundancy.

We build on previous work by evaluating physician perspectives of the mdc model, an area that has not previously been assessed12,13. Physicians reported several perceived benefits of the mdc model, including improvements in communication and collaboration, clinic efficiency, quality of care, and patient outcomes. All physician groups described improved communication (attributed to real-time face-to-face discussions with colleagues) and indicated that the mdc improved collegiality and collaborative relationships through a better appreciation of each other’s roles and expertise. Finally, physicians felt that the mdc increased patient comfort and satisfaction by combining physician assessments and that it reduced overall patient and caregiver anxiety through consistent messaging, facilitation of caregiver attendance, and reduced wait times.

Physician perceptions of the benefits of the mdc are important because the physicians were the only individuals in the study to experience both models of care, providing a direct comparison between the models. Importantly, the benefits reported by physicians were consistent with measured improvements in the timeliness of oncology assessment and treatment14 and provide plausible explanations for the previously identified improvement in time to lc treatment in the mdc model. The improved collegiality and interpersonal relationships reported by the physician group is noteworthy. Physician burnout is common, and one of the best studied organizational strategies to prevent burnout has been cultivating a work community and creating connectedness between physicians24. Burnout affects the quality of patient care in that it influences patient safety, patient satisfaction, physician turnover, and health care system costs24,25. An unanticipated benefit of the mdc appears to be an improved collegial and team-based culture among thoracic oncologists, which could be contributing to an improved work experience for physicians, warranting further evaluation.

Patients seen in both care models generally reported high satisfaction, despite data from the mdc model demonstrating improved wait times and physician-perceived improvements. One possible explanation for that observation is that most patients with cancer who were living and well enough to be interviewed would report positive experiences of the health care system. That explanation is supported by a study showing that patients with cancer underreport adverse events26. It also points to a possible limitation, in that patients experienced only a single model of care at the time of their lc diagnosis, making a comparison of perceived efficiency between models challenging.

Patients did report two notable differences between the traditional and mdc models. First, patients seen at the mdc consistently reported the convenience and efficiency of the model, a finding that is in keeping with previous research13. Additionally, several patients seen at the mdc reported that having concurrent appointments made it more likely that family members could attend for support. Caregiver attendance at appointments is important, because many patients with newly diagnosed advanced lc have an inaccurate understanding of their diagnosis27, and caregivers assist with medical decision-making, psychosocial support, and health care system navigation28. Although 1 patient seen under the traditional model reported dissatisfaction with perceived disjointed communication and poor patient advocacy, that patient had a unique clinical course that required urgent transfer to the emergency department directly from the ldap clinic.

Our interviews explored patient perceptions of being overwhelmed with information from multiple physician assessments and the potential for inconsistent messaging from mdc physicians, because those factors had been raised as potential concerns in prior studies13. We found that patients and caregivers seen in the mdc reported receiving an appropriate level of detail about their diagnosis and plan; furthermore, consistent messaging and collaboration between team members was a perceived strength of the mdc. Physicians had primarily positive impressions of the mdc, but as an improvement opportunity, identified a need to design clinic space to better support multidisciplinary work.

Our study has several unique strengths. First, we were able to correlate our results with a simultaneous quantitative analysis of the mdc, which corroborated physician perceptions of improved clinic efficiency and reduced wait times14. Additionally, although most analyses of lc mdcs to date have emerged from American institutions using private pay systems12, ours represents a unique initiative in Ontario, where patients have universal health coverage, which helps with the potential generalizability of our findings. In addition, the relatively small size of the thoracic oncology program at our centre enabled participation by almost all physicians involved in the mdc program. Finally, as opposed to focus groups used in other studies13, we used individual in-person interviews of patients and caregivers, which facilitated a more natural and confidential interaction and allowed for interviewers to ask follow-up questions when necessary.

As with any attempt to evaluate subjective experiences, our study has inherent limitations. The retrospective nature of the study could have led to both selection bias and recall bias, in that patients who remained alive to be interviewed might have been likely to have more favourable disease characteristics or better response to therapy. Given the high mortality associated with lc, many of the patients we identified for interview were unfortunately deceased or too unwell to participate. Furthermore, patients who declined to be interviewed might have had a less positive clinical experience. Similarly, facilitating in-person interviews for patients outside of the city was challenging and might have affected the type of patients we were able to recruit. Another limitation to our study is the lack of an evaluation of the thoracic surgery presence in the mdc. We have been working with thoracic surgery to increase their involvement in the mdc clinic, but none of the patients in our study received a same-day thoracic surgery consultation. Future qualitative studies of patient and caregiver experiences in mdcs could ideally enrol and interview participants prospectively to reduce the effect of selection and recall bias.

CONCLUSIONS

Diagnosis and management of lc is complex—in part because it requires the contributions of multiple medical specialists. Previous studies have shown that creating a multidisciplinary environment can minimize the time to oncologic assessment and treatment. Our qualitative assessment of patient, caregiver, and physician experiences found that a lc mdc model has additional benefits compared with a traditional clinic model, including improved communication with patients, collaboration between physicians, clinic efficiency, and quality of care. Physicians perceived the mdc to have positive effects on patient outcomes, an observation that correlates with measurable data. Future studies of a lc mdc care model are warranted.

Supplementary Information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding for this study was obtained from the Department of Medicine Research Award at Queen’s University. The sponsor had no role in the study design or conduct.

Portions of this work were previously published in abstract form: Linford G, Robinson D, Wakeham S, et al. Patient, caregiver, and provider perceptions of care before and after implementation of a multidisciplinary lung cancer clinic: a qualitative assessment of an improvement initiative. Poster presented at: the International Forum for Quality and Safety in Healthcare; Glasgow, Scotland; 27–29 March 2019; and moderated poster presented at: the Canadian Respiratory Conference; Ottawa, Ontario, Canada; 11–13 April 2019.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

We have read and understood Current Oncology’s policy on disclosing conflicts of interest, and we declare that we have none.

REFERENCES

- 1.Canadian Cancer Statistics Advisory Committee. Canadian Cancer Statistics 2018. Toronto, ON: Canadian Cancer Society; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacobsen MM, Silverstein SC, Quinn M, et al. Timeliness of access to lung cancer diagnosis and treatment: a scoping literature review. Lung Cancer. 2017;112:156–64. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2017.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buccheri G, Ferrigno D. Lung cancer: clinical presentation and specialist referral time. Eur Respir J. 2004;24:898–904. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00113603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.asco–esmo consensus statement on quality cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3498–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.4021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Osarogiagbon RU. Overcoming the implementation gap in multidisciplinary oncology care programs. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12:888–91. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2016.014688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Byrne SC, Barrett B, Bhatia R. The impact of diagnostic imaging wait times on the prognosis of lung cancer. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2015;66:53–7. doi: 10.1016/j.carj.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brocken P, van der Heijden EH, Oud KT, et al. Distress in suspected lung cancer patients following rapid and standard diagnostic programs: a prospective observational study. Psychooncology. 2015;24:433–41. doi: 10.1002/pon.3660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yiu KCY, Juergens RA, Swaminath A. Multidisciplinary influence on care of lung cancer patients at the time of diagnosis: a patient survey. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2016;28:667. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2016.04.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davies AR, Deans DA, Penman I, et al. The multidisciplinary team meeting improves staging accuracy and treatment selection for gastroesophageal cancer. Dis Esophagus. 2006;19:496–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2006.00629.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Junor EJ, Hole DJ, Gillis CR. Management of ovarian cancer: referral to a multidisciplinary team matters. Br J Cancer. 1994;70:363–70. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1994.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coory M, Gkolia P, Yang IA, Bowman RV, Fong KM. Systematic review of multidisciplinary teams in the management of lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2008;60:14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stone CJL, Vaid HM, Selvam R, Ashworth A, Robinson A, Digby GC. Multidisciplinary clinics in lung cancer care: a systematic review. Clin Lung Cancer. 2018;19:323–30.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2018.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kedia SK, Ward KD, Digney SA, et al. “One-stop shop”: lung cancer patients’ and caregivers’ perceptions of multidisciplinary care in a community healthcare setting”. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2015;4:456–64. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2218-6751.2015.07.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stone CJL, Robinson A, Brown E, et al. Improving timeliness of oncology assessment and cancer treatment through implementation of a multidisciplinary lung cancer clinic. J Oncol Pract. 2019;15:e169–77. doi: 10.1200/JOP.18.00214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Honein-AbouHaidar GN, Stuart-McEwan T, Waddell T, et al. How do organisational characteristics influence teamwork and service delivery in lung cancer diagnostic assessment programmes? A mixed-methods study. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e013965. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soukup T, Lamb BW, Arora S, Darzi A, Sevdalis N, Green JS. Successful strategies in implementing a multidisciplinary team working in the care of patients with cancer: an overview and synthesis of the available literature. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2018;11:49–61. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S117945. [Erratum in: J Multidiscip Healthc 2018; 11:267] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leo F, Venissac N, Poudenx M, Otto J, Mouroux J on behalf of the Groupe d’Oncologie Thoracique Azuréen. Multidisciplinary management of lung cancer: how to test its efficacy? J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:69–72. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31802bff56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Osarogiagbon RU. Making the evidentiary case for universal multidisciplinary thoracic oncologic care. Clin Lung Cancer. 2018;19:294–300. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2018.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ontario Health (Cancer Care Ontario) [oh(cco)] Home > Data and Research > View Data > Cancer Statistics > Ontario Cancer Profiles [Web resource] Toronto, ON: OH(CCO); 2018. [Available by searching at: https://www.cancercareontario.ca/en/data-research/view-data/cancer-statistics/ontariocancer-profiles; cited 31 January 2019] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Creswell JW. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. 5th ed. Vol. 2018. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications; p. 304. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palaganas EC, Sanchez MC, Molintas MV, Caricativo RD. Reflexivity in qualitative research: a journey of learning. Qual Rep. 2017;22:426–38. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patton MQ. Qualitative research. In: Everitt BS, Howell DC, editors. Encyclopedia of Statistics in Behavioral Science. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fram SM. The constant comparative analysis method outside of grounded theory. Qual Rep. 2013;18:1–25. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH. Executive leadership and physician well-being: nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:129–46. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med. 2018;283:516–29. doi: 10.1111/joim.12752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mazor KM, Roblin DW, Greene SM, et al. Toward patient-centered cancer care: patient perceptions of problematic events, impact, and response. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1784–90. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Temel JS, Greer JA, Admane S, et al. Longitudinal perceptions of prognosis and goals of therapy in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: results of a randomized study of early palliative care. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2319–26. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.4459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mitnick S, Leffler C, Hood VL on behalf of the American College of Physicians Ethics, Professionalism and Human Rights Committee. Family caregivers, patients and physicians: ethical guidance to optimize relationships. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:255–60. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1206-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.