Abstract

Introduction

Training in humanism provides skills important for improving the quality of care received by patients, achieving shared decision-making with patients, and navigating systems-level challenges. However, because of the dominance of the biomedical model, there is potentially a lack of attention to humanistic competencies in global oncology curricula. In the present study, we aimed to explore the incorporation of humanistic competencies into global oncology curricula.

Methods

This analysis considered 17 global oncology curricula. A curricular item was coded as either humanistic (as defined by the iecares framework) or non-humanistic. If identified as humanistic, the item was coded using an aspect of humanism, such as Altruism, from the iecares framework. All items, humanistic and not, were coded under the canmeds framework using 1 of the 7 canmeds competency domains: Medical Expert, Communicator, Collaborator, Leader, Scholar, Professional, or Health Advocate.

Results

Of 7792 identified curricular items in 17 curricula, 780 (10%) aligned with the iecares humanism framework. The proportion of humanistic items in individual curricula ranged from 2% to 26%, and the proportion increased from 3% in the oldest curricula to 11% in the most recent curricula. Of the humanistic items, 35% were coded under Respect, 31% under Compassion, 24% under Empathy, 5% under Integrity, 2% under Excellence, 1% under Altruism, and 1% under Service. Within the canmeds domains, the humanistic items aligned mostly with Professional (35%), Medical Expert (31%), or Communicator (25%).

Conclusions

The proportion of humanistic competencies has been increasing in global oncology curricula over time, but the overall proportion remains low and represents a largely Western perspective on what constitutes humanism in health care. The representation of humanism focuses primarily on the iecares attributes of Respect, Compassion, and Empathy.

Keywords: Global oncology curricula, humanism, canmeds, professionalism, oncology education

INTRODUCTION

Calls for curricular reform to focus on person-centred care are growing, and the concept of humanism is at the centre of those discussions1,2. The concept of humanism in the medical education literature is evolving, but has been a core element of the medical profession since its inception1. A broad conceptualization of humanism in medicine is “any system or mode of thought or action in which human interests, values, and dignity predominate”1. A more specific definition describes humanism in health care as “a respectful and compassionate relationship between physicians, as well as all other members of the healthcare team, and their patients. It reflects attitudes and behaviours that are sensitive to the values and the cultural and ethnic backgrounds of others”3. The latter definition is the basis of the Arnold P. Gold Foundation’s framework of humanism, which describes 7 attributes of the humanistic health care professional: Integrity, Excellence, Collaboration and Compassion, Altruism, Respect and Resilience, Empathy, and Service (iecares)3. Table I sets out the definitions of those attributes. In line with those attributes, a humanistic physician has been described as one who considers the influence of social, cultural, and spiritual experiences in patient care4.

TABLE I.

IECARES framework from the Arnold P. Gold Foundation, 20183

| Integrity | The congruence between expressed values and behaviour |

| Excellence | Clinical expertise |

| Collaboration and compassion | The awareness and acknowledgment of the suffering of another and the desire to relieve it |

| Altruism | The capacity to put the needs and interests of another before your own |

| Respect and resilience | The regard for the autonomy and values of another person |

| Empathy | The ability to put oneself in another’s situation—for example, physician as patient |

| Service | The sharing of one’s talent, time, and resources with those in need; giving beyond what is required |

Training physicians as scientists is central to the biomedical model of medical education5, including education and training in oncology. However, centring the role of science in medical training might also inadvertently undermine the role of humanism in Western medical practice6. In cancer care, in which communication and team-based care are essential skills, training in humanism could have particular relevance. In addition, ongoing and forthcoming changes to professional practice such as artificial intelligence and the implementation of curricula in global contexts might also challenge the capacity of providers to practice humanistic care. For example, artificial intelligence has the potential to radically change the nature of medical practice by replacing large portions of the diagnostic work currently done by physicians7. Such changes in the delivery of care have implications for patient interactions with health care providers in how the patients experience their overall care. Furthermore, it has been argued that, as with other health care professionals, oncologists are not receiving the training they need to meet the needs of all patients, families, and the health care system8. That mismatch between training and clinical practice, including gaps in team-based competencies and communication skills has been attributed to outdated curricula8 and potentially to a lack of attention to humanistic competencies such as an awareness of how context and culture affects health care behaviours, experiences, and outcomes.

The high rate of burnout among oncologists calls for a different approach to education9. Training in humanism has been argued to increase physician job satisfaction10, to improve both patient clinical outcomes and satisfaction with care7, and to provide health professionals with the skills to achieve shared decision-making with patients and their families, to navigate systems-level challenges, and to function positively within the health care team6. The skills afforded by humanistic education—including engaging with complexity and ambiguity, mitigating physician burnout, and navigating power relationships—could be critical in closing the current training-to-practice gap that has been identified for health care curricula11.

Despite growing recognition of the potential of humanism for medical education, the current understanding of the integration of humanism into curricula is limited, specifically in light of increasing efforts to establish and implement global curricula. Global oncology curricula have been identified for oncology specialities including radiation, medical, and surgical oncology. The purpose of those curricula is to improve the quality of patient care, to harmonize training standards across jurisdictions, and ultimately to facilitate physician mobility (Giuliani M, Frambach J, Broadhurst M, Papadakos J, Driessen E, Martimianakis T. A critical review of representation in global oncology curricula development and the influence of neocolonialism. In preparation). That effort might be problematic, considering that the understanding of humanism and its integration into curricula is culturally specific2,12. Humanistic competencies such as ethics and altruism are socially constructed ideas and practices, and the way in which they are conceptualized, performed, and received can therefore vary by region13. As a result, adopting humanistic competencies from Western to non-Western contexts14 is a difficult educational process. A known challenge in establishing global curricula is the tension between meeting local needs and achieving international standards15,16. That challenge of balancing the local and the global is particularly effortful for humanistic competencies17.

Understanding the current state of the integration of humanism into global oncology curricula could yield insight into a possible source of the mismatch between curricula and the competencies needed for practice. Efforts to internationalize curricula are growing, and there is a potential for overdominance of a Western viewpoint at the expense of other perspectives in those efforts. Although no clear consensus has been reached on how to prioritize curricular content, having a greater understanding of the content of existing curricula can assist in informing future work in global jurisdictions to prepare health care professionals for practice. The aims of the present study were to explore the extent to which humanistic competencies are included in global oncology curricula and to identify the nature of the included humanistic competencies.

METHODS

Sampling

In the present study, we analyzed the content of published global oncology curricula, using 17 global oncology curricula identified in a systematic review conducted for another manuscript (Giuliani M, Frambach J, Broadhurst M, Papadakos J, Driessen E, Martimianakis T. A critical review of representation in global oncology curricula development and the influence of neocolonialism. In preparation). Of the 17 curricula, 5 were from medical oncology, 5 were from radiation oncology, and 4 were from surgical oncology. Two well-known and internationally recognized medical competency frameworks were used to analyze those curricula: the Arnold P. Gold Foundation’s iecares framework (Table I) and the canmeds framework. Keyword codes—Integrity, Excellence, Collaboration and Compassion, Altruism, Respect and Resilience, Empathy, and Services—were derived from the components of the iecares framework and were assigned to each curricular item.

The curricula were also coded according to the canmeds competency framework18. The canmeds framework was selected because it has been implemented or adopted in multiple jurisdictions around the world and because it aligns well with other competency frameworks such as the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education framework. In addition, canmeds has a detailed elaboration of the components and attributes assigned to each of the 7 competency domains, allowing for appropriate application of the framework to the curricular documents. Applying canmeds—a Western framework with broad uptake around the world—allowed us to understand one system through which medical education is currently operationalized in the global context. By coding according to canmeds, we were able to assess areas that might currently be overregulated or overemphasized compared with their use in other areas in regions of the world adopting canmeds. Those data could provide insight into how oncology education has organized and prioritized curricular content.

We hypothesized that there would be a relative lack of humanism in global curricula and that that lack might signal an under-emphasis on humanistic issues in curriculum forums in which Western voices dominate or a limited ability to attend to the complexity of including such competencies in global curricula.

Curricular Content Analysis

A priori, a coding structure was determined. During several meetings, 2 reviewers (MG, MB) discussed the application of the iecares and canmeds frameworks to the curricula. As the analysis progressed, it was discussed with other authors at regular meetings. The 2 investigators then independently reviewed each curricular document. Consensus was reached on the nature of each competency item, and any disagreements were resolved by adjudication involving the whole research team as necessary. The analysis was performed using the NVivo software application (version 11: QSR International, Melbourne, Australia).

Each curricular item was coded as either humanistic (as defined by the iecares framework) or non-humanistic. If an item was identified as humanistic, the specific aspect of humanism from the iecares framework, such as Altruism, was coded. A competency item could be attributed to more than one aspect of iecares. All items, humanistic and not, were coded under the canmeds framework using 1 of the 7 canmeds competency domains of Medical Expert, Communicator, Collaborator, Leader, Scholar, Professional, or Health Advocate18. A competency item could be attributed to more than one canmeds domain.

To determine the level of agreement between coders, the kappa statistic and percentage agreement were determined. Between the 2 reviewers, the kappa statistic for humanism and non-humanism coding was 0.92, and the percentage agreement was 99%. Descriptive statistics are used to describe the proportion of each curricula that address humanistic competencies, the nature of the humanistic competencies, and the proportions of the canmeds competency items.

RESULTS

To What Extent Are Humanistic Competencies Included?

The 17 identified curricula contained 7792 curricular items. Of the 7792 items, 780 (10%) were identified as humanistic, and 7012 (90%), as non-humanistic. In individual curricula, the proportion of humanistic items ranged from 2% to 26%. Of 17 curricula, 12 had less than 10% of their items coded as humanistic. The proportion of humanistic items has been increasing: to a mean of 11% for curricula published in 2010–2017 from a mean of 3% for curricula published in 1980–1989 (range: 4%–25%; Table II).

TABLE II.

Proportion of humanism in curricula

| Variable | Humanism content (%) | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Mean | Range | |

| Publication period | ||

| 1980–1989 | 3 | NA |

| 1990–1999 | — | |

| 2000–2009 | 5 | 2–7 |

| 2010–2017 | 11 | 4–25 |

|

| ||

| Publication region | ||

| Africa | — | |

| Asia | — | |

| Oceania | 10 | 5–15 |

| Europe | 9 | 2–26 |

| Latin Americas | — | |

| North America | 5 | 3–6 |

NA = not applicable.

What Is the Nature of the Humanistic Competencies?

Of the 780 items coded as humanistic, 886 alignments with the iecares framework were identified. Of those 886 alignments, 48 (5%) represented Integrity; 18 (2%), Excellence; 272 (31%), Compassion; 12 (1%), Altruism; 311 (35%), Respect; 212 (24%), Empathy; and 13 (1%), Service (Table III). Table IV provides examples of competency items in each of the iecares domains.

TABLE III.

Distribution of humanistic competencies within the IECARES framework

| Humanistic items [n (%)] | IECARES framework item | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Integrity | Excellence | Compassion | Altruism | Respect | Empathy | Service | |

| 48 (5) | 18 (2) | 272 (31) | 12 (1) | 311 (35) | 212 (24) | 13 (1) | |

TABLE IV.

Examples of competency items for each aspect of the IECARES framework

| Humanism domain | Sample competency item |

|---|---|

| Integrity | “Practice medicine in accordance with medical ethics and patient rights”19 |

| “The surgical oncologist must take responsibility for their actions and outcomes with honesty and a desire to continually improve, always putting the patient’s needs first”20 | |

|

| |

| Excellence | “Surgical oncologists have a professional duty to maintain and continually update their expertise to enable them to offer patient care that maximizes beneficial outcomes within the limits of the healthcare environment in which they practice”20 |

|

| |

| Compassion and collaboration | “Ability to elicit the patient’s wishes with regard to the aims of treatment and to give the treatment alone or in collaboration with other specialists”21 |

| “Listening to patients and responding to their questions, concerns and preferences and keeping them informed about the progress of their care”22 | |

|

| |

| Altruism | “The surgical oncologist must take responsibility for their actions and outcomes with honesty and a desire to continually improve, always putting the patient’s needs first”20 |

|

| |

| Respect and resilience | “Always considerate, polite and thoughtful of patients and colleagues”23 |

| “Ability to elicit the patient’s wishes with regard to the aims of treatment and to give the treatment alone or in collaboration with other specialists”21 | |

|

| |

| Empathy | “Recognizes the impact of bad news on the patient, carers, staff members and self”22 |

| “Depression and anxiety, the role of the clinical nurse specialist. How to recognise the symptoms and signs of psychological distress and secondary mental illness. Management strategies”24 | |

|

| |

| Service | “Accepts additional duties in situations of unavoidable and unpredictable absence of colleagues ensuring that the best interests of the patient are paramount”22 |

What Is the Relationship of Humanism to Non–Medical Expert Competencies?

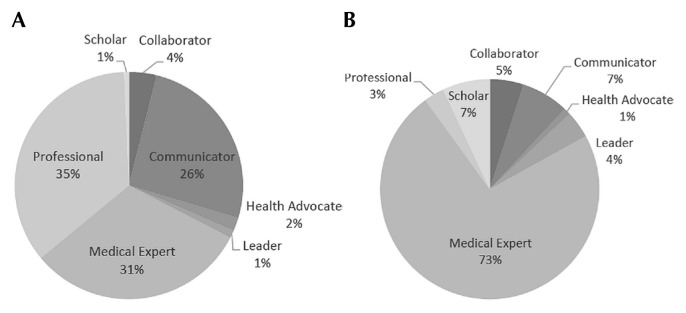

Of the 8023 canmeds attributions identified, 5549 (69%) represented Medical Expert; 685 (9%), Communicator; 391 (5%), Collaborator; 267 (3%), Leader; 528 (7%), Scholar; 518 (6%), Professional; and 85 (1%), Health Advocate. Most of the humanistic items were attributed to the Professional (n = 261, 35%), Medical Expert (n = 232, 31%), and Communicator (n = 190, 26%) canmeds domains (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Proportion of (A) humanistic and (B) non-humanistic competency items by CanMEDs role.

DISCUSSION

Our analysis of global oncology curricula shows that humanistic competencies comprise a wide range, 2%–26%, of curricular content. Although the proportion of humanism has increased over time, with a greater proportion of humanism represented in more recently published curricula, most curricula contain less than 10% humanistic competencies. Although no consensus has been reached about the ideal proportion of curricula that should reflect humanistic competencies, such skills are perceived as important for improving the quality of care received by patients, realizing shared decision-making with patients, and addressing systems-level issues8,25. Devoting less than 10% of curricula to humanistic competencies could therefore be problematic.

Defining and describing curricula to meet the wide breadth of competencies while accounting for and appreciating regional and cultural differences is a challenge—especially when curricular planning is intended to have global application. However, as efforts continue to revise, update, and improve global curricula, there is a need to reflect on the risk of reductionism in the definition of competencies and to ensure that humanistic concepts conducive to supporting local needs of patients are preserved26. The integration of humanistic competencies into global oncology curricula requires advocates for those skills. Educators have been successful in implementing humanism in medical curricula by creating a sense of urgency27. Our data might assist in articulating that imperative platform for oncology by providing a description of the current and highly variable state of humanism in global oncology curricula.

It was previously noted by Martimianakis et al.2 that most publications addressing humanism in medical education originate from a North American context and that a conflation exists between humanistic competencies and Professionalism. Our analysis supports that finding, with the highest proportion of humanistic items attributed to the Professionalism domain (35%). Since the start of the 2000s, a focus on including non–Medical Expert competencies, such as Professionalism, into training frameworks in Western contexts has indeed been growing18. Although we are not able to ascertain the reason for that conflation between humanism and Professionalism, it is possible that the focus on directing and shaping the behaviour of individuals to conform to regulatory and professional norms supersedes other aspects of care such as Empathy and Service. In the Western setting, most medical schools have made efforts to incorporate humanism into medical training, and those efforts have been operationalized through a link to Professionalism28. Health Advocate represents 2% of humanistic items in existing curricula. The lack of focus on Health Advocate that emerged in our analysis is surprising given the global lack of access to cancer care and the recognized need for addressing health inequities in treatment access. One possible challenge in implementing humanistic curricula more comprehensively is a lack of shared understanding of complex concepts such as Empathy. In addition, where measurement for assessment is important, lack of a clear understanding of what to measure in humanistic competencies represents a potential barrier29. The method most commonly used for assessment of humanistic competencies is self-report, and most of the reports in the literature originate from North America30. In addition, Professionalism is the dimension that has received the most assessment attention, which might be a contributing factor to the conflation between humanism and professionalism. Future efforts to more comprehensively include the diverse aspects of humanism within oncology curricula can be assisted by understanding the current state of existing curricula as reported in this paper. Our data show that the representation of humanism in existing curricula focuses on Respect, Compassion, and Empathy, and that there is a conflation between humanism and Professionalism and a relative paucity of humanism connected with Health Advocate.

The cultural influence of Western ideas has been reported for humanistic competencies in medicine10. A mismatch might therefore exist between a Western concept of humanism and its suitability in non-Western domains31, creating a potential barrier to integrating health care and delivery practices associated with humanism into global curricula. The known East–West differences in health care ecosystems for cancer care add to the complexity of the discussion32. Literature about the potential global applicability of Western frameworks of humanism is lacking12. Cultural diversity and contextual factors limit the direct transfer of Western pedagogic approaches and priorities to non-Western settings33. However, local contextualization of Western approaches has been achieved—albeit with significant effort and time dedicated to that achievement. A Chinese research group showed that, using Nominal Group Technique, it was feasible to contextualize and locally apply Western frameworks in a Chinese setting10. A Taiwanese group used the 6-step curriculum development framework as a method to integrate local cultural and societal needs into Western-framed humanistic profiles34.

One driving factor for the integration of humanistic competencies into non-Western settings can be the objective to meet international accreditation standards35. In East Asian settings, Pan et al.14 demonstrated both cultural influence and conflict with Western ideologies. The cultural basis of humanistic competencies has necessitated a call for a global approach to integrate those competencies17,36. Skills in humanistic domains extend beyond an empathetic, caring relationship with patients and families and involve the recognition and ability to navigate differences in values and to understand the impacts of power relationships in health care26. Although the need for humanism in health care transcends culture, further work is needed to understand the barriers to inclusion of greater humanistic competencies in global curricula.

The present work has several limitations. We applied 2 specific frameworks, canmeds and iecares, in our analysis, but we acknowledge the existence of other frameworks of medical competency and conceptualizations of humanism. Moreover, the 2 frameworks we used have a Western focus. However, the curricula that formed the basis of this analysis were developed largely by Western authors. In addition, we are not currently aware of a non-Western framework that addresses humanism. If one were to be available, an analysis comparing the application of Western and non-Western frameworks would provide essential information about the degree of relevance of global curricular frameworks that currently rely on Western perspectives. Such data could serve as a basis for critically reviewing the content of future oncology curricula. In addition, the language of competency items is negotiated by members of the curriculum development group and reflects their sociocultural orientation and biases37. Individual competency items are therefore open to interpretation by individuals with diverse socio-geographic orientations, and we cannot ascertain the degree of variability in the interpretation of those global oncology curriculum items. Any differences might be best elucidated using a qualitative approach.

CONCLUSIONS

The proportion of humanistic competencies in global oncology curricula has been increasing over time; however, the overall proportion remains low and represents a largely Western perspective concerning what constitutes humanism in health care. The representation of humanism focuses primarily on the iecares attributes of Respect, Compassion, and Empathy. Future efforts in shaping a global curriculum might benefit from attention to the incorporation of all aspects of humanistic competencies. Further work is needed to understand how humanism might be perceived differently in various cultural and geographic contexts.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project was made possible by a Mapping the Landscape, Journeying Together grant from the Arnold P. Gold Foundation.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

We have read and understood Current Oncology’s policy on disclosing conflicts of interest, and we declare that we have none.

REFERENCES

- 1.Thibault GE. Humanism in medicine: what does it mean and why is it more important than ever? Acad Med. 2019;94:1074–7. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martimianakis MA, Michalec B, Lam J, Cartmill C, Taylor JS, Hafferty FW. Humanism, the hidden curriculum, and educational reform: a scoping review and thematic analysis. Acad Med. 2015;90(suppl):S5–13. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arnold P. Gold Foundation. FAQs > What is humanism in healthcare [Web page] Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Arnold P. Gold Foundation; 2018. [Available at: https://www.gold-foundation.org/about-us/faqs; cited 1 May 2018] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller SZ, Schmidt HJ. The habit of humanism: a framework for making humanistic care a reflexive clinical skill. Acad Med. 1999;74:800–3. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199907000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whitehead C. Scientist or science-stuffed? Discourses of science in North American medical education. Med Educ. 2013;47:26–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hartzband P, Groopman J. Keeping the patient in the equation—humanism and health care reform. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:554–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0904813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robbins JA, Bertakis KD, Helms LJ, Azari R, Callahan EJ, Creten DA. The influence of physician practice behaviors on patient satisfaction. Fam Med. 1993;25:17–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA, et al. Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet. 2010;376:1923–58. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61854-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shanafelt TD, Gradishar WJ, Kosty M, et al. Burnout and career satisfaction among US oncologists. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:678–86. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.8480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horowitz CR, Suchman AL, Branch WT, Jr, Frankel RM. What do doctors find meaningful about their work? Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:772–5. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-9-200305060-00028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumagai AK. Beyond “Dr. Feel-Good”: a role for the humanities in medical education. Acad Med. 2017;92:1659–60. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gosselin K, Norris JL, Ho MJ. Beyond homogenization discourse: reconsidering the cultural consequences of globalized medical education. Med Teach. 2016;38:691–9. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2015.1105941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al-Eraky MM, Chandratilake M. How medical professionalism is conceptualised in Arabian context: a validation study. Med Teach. 2012;34(suppl 1):S90–5. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.656754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pan H, Norris JL, Liang YS, Li JN, Ho MJ. Building a professionalism framework for healthcare providers in China: a nominal group technique study. Med Teach. 2013;35:e1531–6. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2013.802299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sefton AJ. New approaches to medical education: an international perspective. Med Princ Pract. 2004;13:239–48. doi: 10.1159/000079521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ho MJ, Abbas J, Ahn D, Lai CW, Nara N, Shaw K. The “glocalization” of medical school accreditation: case studies from Taiwan, South Korea, and Japan. Acad Med. 2017;92:1715–22. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jha V, McLean M, Gibbs TJ, Sandars J. Medical professionalism across cultures: a challenge for medicine and medical education. Med Teach. 2015;37:74–80. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2014.920492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frank JR, Snell L, Sherbino J, editors. CanMEDS 2015 Physician Competency Framework. Ottawa, ON: Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coffey MA, Mullaney L, Bojen A, Vaandering A, Vandevelde G. Recommended ESTRO Core Curriculum for Radiation Oncologists/Radiotherapists. 3rd ed. Brussels, Belgium: European Society for Radiotherapy and Oncology; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Are C, Berman RS, Wyld L, Cummings C, Lecoq C, Audisio RA. Global curriculum in surgical oncology. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2016;42:754–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2016.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dittrich C, Kosty M, Jezdic S, et al. esmo/asco recommendations for a global curriculum in medical oncology edition 2016. ESMO Open. 2016;1:e000097. doi: 10.1136/esmoopen-2016-000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Royal College of Radiologists (rcr), Faculty of Clinical Oncology. Specialty Training Curriculum for Clinical Oncology. London, U.K.: RCR; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joint Royal Colleges of Physicians Training Board (jrcptb) Speciality Training Curriculum for Medical Oncology. London, UK: JRCPTB; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 24.ESSO Curriculum Committee. ESSO core curriculum 2013. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2013;39(suppl 1):S1–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2013.07.084. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horlait M, Leys M, De Greve J, Van Belle S. Integrating communication as a core skill in the global curriculum for medical oncology. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:670–1. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gaufberg E, Hodges B. Humanism, compassion and the call to caring. Med Educ. 2016;50:264–6. doi: 10.1111/medu.12961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steinert Y, Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Boudreau JD, Fuks A. Faculty development as an instrument of change: a case study on teaching professionalism. Acad Med. 2007;82:1057–64. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000285346.87708.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Montgomery L, Loue S, Stange KC. Linking the heart and the head: humanism and professionalism in medical education and practice. Fam Med. 2017;49:378–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holmboe E. Bench to bedside: medical humanities education and assessment as a translational challenge. Med Educ. 2016;50:275–8. doi: 10.1111/medu.12976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buck E, Holden M, Szauter K. A methodological review of the assessment of humanism in medical students. Acad Med. 2015;90(suppl):S14–23. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ho MJ, Yu KH, Hirsh D, Huang TS, Yang PC. Does one size fit all? Building a framework for medical professionalism. Acad Med. 2011;86:1407–14. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31823059d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Agarwal JP, Lee VHF. East meet West: convergence of the art and science of oncology. Clin Oncol. 2019;31:487–9. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2019.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frambach JM, Driessen EW, Chan LC, van der Vleuten CP. Rethinking the globalisation of problem-based learning: how culture challenges self-directed learning. Med Educ. 2012;46:738–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2012.04290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsai SL, Ho MJ, Hirsh D, Kern DE. Defiance, compliance, or alliance? How we developed a medical professionalism curriculum that deliberately connects to cultural context. Med Teach. 2012;34:614–17. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.684913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chiu CH, Arrigo LG, Tsai D. Historical context for the growth of medical professionalism and curriculum reform in Taiwan. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2009;25:510–14. doi: 10.1016/S1607-551X(09)70558-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Al-Rumayyan A, Van Mook WNKA, Magzoub ME, et al. Medical professionalism frameworks across non-Western cultures: a narrative overview. Med Teach. 2017;39(suppl 1):S8–14. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2016.1254740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lurie SJ, Mooney CJ, Lyness JM. Commentary: pitfalls in assessment of competency-based educational objectives. Acad Med. 2011;86:412–14. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31820cdb28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]