Abstract

Objectives

To determine the effect of bovine lactoferrin on prevention of late onset sepsis (LOS) and neurodevelopment delay.

Study design

Randomized double blind controlled trial in neonates with a birth weight of 500–2000g in three neonatal units in Lima, Peru, comparing BLF 200mg/kg/day vs. placebo administered for 8 weeks. The primary outcome was the first episode of culture-proven LOS or sepsis-associated death. Neurodevelopment delay was assessed by the Mullen Scales at 24 months corrected age.

Results

Of the 414 infants enrolled, 209 received BLF and 205 received placebo. LOS or sepsis-associated death occurred in 22 (10.5%) infants in the BLF group vs. 30(14.6%) in the placebo group; there was no difference after adjusting for hospital and birth weight; hazard ratio 0.73 (95% CI 0.42–1.26). For infants with birth weights <1500g the hazard ratio was 0.69 (95%CI, 0.39–1.25). The mean age-adjusted normalized Mullen composite score at 24 months was 83.3 ± 13.6 in the BLF group vs 82.6 ± 13.1 in the placebo group. Growth outcomes and re-hospitalization rates during the 2-year follow-up were similar in both groups, except for significantly less bronchiolitis in the BLF group; rate ratio 0.34 (95% CI 0.14–0.86).

Conclusions

Supplementation with BLF did not reduce the incidence of sepsis in infants with birth weights <2000g. Growth and neurodevelopment outcomes at 24 months of age were similar. Neonatal BLF supplementation had no adverse effects.

Trial registration

Keywords: neonate, premature, milk, infection, mortality

Breast milk protects preterm infants from infections and improves cognitive development.1–3 One of the multiple bioactive components in milk4 is lactoferrin a glycoprotein with antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties.5 LF has multiple mechanisms for protection against infection, including bacteriostatic effects (iron sequestration); disruption of bacterial cell membranes by binding lipopolysacccharide in gram-negative bacteria; binding pathogen-host cell receptors; inhibiting biofilm formation; modulating intestinal flora; promoting intestinal cell proliferation, differentiation and maturation; regulating immune response; and anti-oxidative effects.6,7

There is growing interest in LF clinical applications, including protection against neonatal infections8,9 with published trials of bovine LF for protection against sepsis and necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants10–17, including our pilot study.18 However, most trials, had small sample sizes. All trials followed infants until hospital discharge without information on long-term outcomes. It is postulated that preterm brain exposure to inflammatory mediators during infection contributes to brain injury and poor neurodevelopment.19–20 We hypothesized that BLF would improve neurodevelopment by immunoregulation, reducing infection-related inflammation.

This study aimed to determine the effect of BLF on prevention of late-onset sepsis (LOS) or sepsis-associated death in infants with <2000g birth weight (BW) (aim1); and the effect on neurodevelopment and growth at 24 months (m) corrected age (c.a.) (aim2).

METHODS

The study was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in three neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) in Lima, Peru (Cayetano, Almenara, Sabogal). The study was approved by the ethics committee of Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, each hospital, and Peruvian regulatory institutions (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01525316).

Infants were included if they weighed 500–2000g at birth and were inborn or referred to the NICUs in the first 72 hours (h) after birth. Infants were excluded if they had underlying gastrointestinal problems preventing enteral intake, predisposing conditions profoundly affecting growth and development, family history of cow’s milk allergy or were unlikely to complete the study. Written informed consent was obtained from both parents.

The randomization list was performed with fixed, equal allocation to each group, in random blocks of 4, stratified by BW (500–1000g, 1001–1500g, 1501–2000g) and hospital. Infants were assigned a consecutive number in the order of enrollment after calling the central coordination office. Randomization occurred immediately after recruitment. BLF or placebo capsules were opened and dissolved in breast milk or formula for masking. Only the research nurse knew treatment assignment; clinical and research staff and parents were blinded until the end of the study.

Enteral BLF (Friesland Campina, The Netherlands) or placebo (maltodextrin) (Montana, Lima, Peru) 200mg/kg/day was administered in 3 divided doses for 8 weeks (w) (maximum 600mg daily). Capsules containing 100 or 200 mg of BLF or placebo were dissolved in breast milk or formula; 100mg dissolved in a minimum volume of 4mL (maximum BLF concentration 25mg/mL). The first dose was given on enrollment day or as soon as she/he tolerated enteral intake. The NICU nurse prepared and administered the intervention.

Hospital data was collected daily until discharge. Sepsis or meningitis evaluations were done per standard care at each hospital; in general, two sets of blood cultures were drawn for each episode of suspected sepsis and sent to the hospital microbiology laboratory and a centralized laboratory. Cultures were monitored for growth with automated systems (BACTEC and/or BacT/ALERT) and positive cultures were processed according to conventional techniques. The hospitals had no protocols for feeding, fluconazole prophylaxis or antibiotic prophylaxis. All human milk was mother’s own fresh expressed milk; no donor milk or probiotics were used. Breast milk (2–3mL) was collected in the first 7d of life (colostrum) and at 1 month to measure human-LF using an ELISA (Assaypro, St.Charles, MO, USA).

We followed infants up to 24 months corrected age by phone every 2 weeks. Pediatric evaluations were performed at 3, 6, 12, 18 and 24 months; auditory brainstem response examination at 37–44 weeks postmenstrual age or at hospital discharge; neurological evaluations at 6, 12 and 24 months; and ophthalmology evaluations at 24 months. Infants completed the Mullen Scales of Early Learning (Mullen)21 at 12, 18 and 24 months and the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development,3rd-Edition (Bayley-III)22 at 24 months. The Mullen is a standardized assessment of five domains from 0–68m: Gross Motor, Fine Motor, Visual Reception, Receptive and Expressive Language. The Early Learning Composite is a standard score (mean=100, SD=15) representing overall cognitive ability, derived from the latter subscales. The Mullen has favorable test-retest reliability for individual scales and excellent interrater reliability. Prior studies have shown that Mullen scores are significant predictors of later-developing intelligence and executive function scores.23–25– At 24 months, parents answered two questionnaires, the Adaptive Behavior Assessment System, 2nd-Edition (ABAS-II)26 and the Modified-Checklist for Autism in Toddlers, Revised (M-CHAT-R). 27

Culture-proven LOS was defined as clinical signs and symptoms of infection and ≥1 positive blood and/or cerebrospinal fluid cultures obtained after 72 hours of age. For coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS), we required two positive blood cultures or one positive blood culture plus a C-reactive protein >10mg/L.28 Probable sepsis or culture-negative infection was defined by the presence of clinical signs and symptoms of infection plus ≥2 abnormal laboratory results29; or one CoNS positive blood culture with ≥7 days of treatment with anti-staphylococcal agents. Each LOS episode was classified based on an algorithm30 and an expert blinded committee.

Study outcomes

For aim 1, the primary study outcome was a composite outcome of the first culture-proven LOS or sepsis-associated death (deaths associated with probable sepsis). Secondary outcomes were: the composite outcome in very low birth weight infants (VLBW, <1500g); pathogen-specific LOS; necrotizing enterocolitis (Bell stage ≥2); retinopathy of prematurity requiring surgery; intraventricular hemorrhage (grade III-IV); bronchopulmonary dysplasia (oxygen requirement >28d); serious infections prior to discharge; hospitalization duration; rehospitalization; overall mortality, infection-related mortality; and frequency of adverse events or intolerance.

For aim 2, the primary outcome was the mean age-adjusted normalized Mullen composite score at 24m. Secondary outcomes were: neurodevelopmental delay (Mullen composite score ≤70, Bayley-III scores <85),31,32 delayed adaptive skills (ABAS-II general adaptive composite score <70); neurodevelopmental impairment (Mullen composite score ≤70, moderate to severe cerebral palsy, bilateral hearing impairment requiring amplification or bilateral blindness); and growth delay (height-for-age and weight-for-height Z-scores <−2). All study outcomes were pre-specified in the protocol.

An independent Data Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) monitored the study for safety and integrity. Serious adverse events were reported to the DSMB, IRBs and regulatory institutions.

The quality and purity of the BLF sample used was analyzed and compared with BLF from our pilot study.18 Samples were tested for purity and impurities using a Reversed Phase High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (Patheon-Pharmaceuticals, Cincinnati, USA); and for bacterial endotoxin (Nelson-Labs, Salt Lake City, USA).

Statistical Analyses

Assuming 25% confirmed-LOS episodes in the placebo group (based on the NICUs’ statistics) and a 15% attrition rate, 207 children were needed in each group to detect a 45% reduction in the number of sepsis episodes (α=0.05; power=0.80). For neurodevelopment, with this sample size and a 30% attrition rate for the 24-m follow-up, we estimated a power of 0.81 to detect a difference of 5 in the Mullen composite between the arms. Statistical analyses were adjusted for weight category and hospital. Two-sided tests at the 0.05 significance level were used. Cox regression was used to evaluate the primary outcome for aim 1on an intention-to-treat analysis; time-at-risk started at day 3 and ended at day 56, at discharge or LOS, whichever came first. Secondary outcomes were evaluated using Cox regression analyses, incidence rate ratios or prevalence ratios. For aim 2, linear regression was used for numerical variables and generalized linear models for binary variables. For the Mullen composite score aggregating data from the 12, 18 and 24m evaluation, we used mixed-effects ML regression, with random intercepts and slopes, and independent correlation. Post-hoc analysis on human LF intake was performed using general linear models. Stata 8.2 was used (StataCorp, College Station, USA).

RESULTS

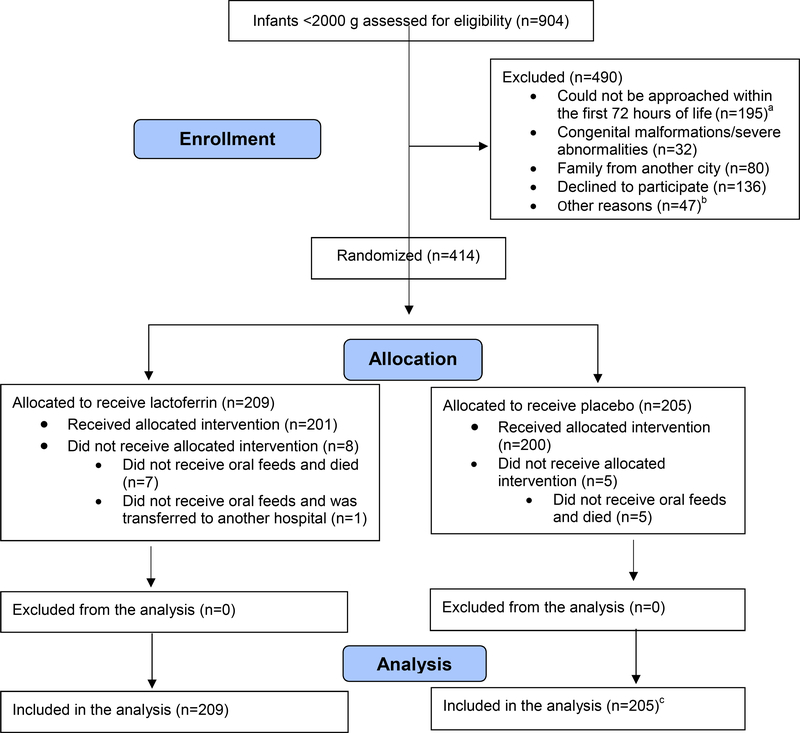

Enrollment occurred from May 2012 to July 2014; of 905 infants within the BW range; 414 were enrolled and randomized, 209 allocated to receive BLF and 205 placebo (Figure 1; available at www.jpeds.com). Mean birth weight and gestational age were 1380±365g and 30.8±3.0 weeks, respectively; 256 were VLBW infants; 4, term; 97 infants (23.4%) from Cayetano, 137 (33.1%) from Almenara and 180 (43.5%) from Sabogal Hospital. Baseline characteristics and risk factors for LOS were comparable between groups (Table I). Treatment compliance was similar; 82.3% of 16,852 prescribed BLF doses were administered completely per protocol vs. 83.5% of 15,880 placebo doses. The diluents used were fresh motheŕs milk (57.7% of the doses), infant formula (42.2%) and dextrose (0.1%).

Figure 1.

Consort diagram Lactoferrin vs Placebo.

a Infants that died during the first 72 hours of life (n=75), were discharged (n=17), or whose parents were not available for enrollment during that period (n=103).

b Infants of single mothers (n=8), adolescent mothers (n=13), mothers in the UCI (n=10), father outside the city (n=5), father absent (n=10), father participating in the trial (n=1).

c This analysis includes a patient that was diagnosed after randomization with esophageal atresia, a condition that prevented oral intake, an exclusion criterion.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics

| Characteristic | Lactoferrin (n=209) | Placebo (n=205) |

|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | No. (%) | |

| Pregnancy and delivery | ||

| Maternal age, mean (SD), y | 29.8 (6.4) | 29.4 (6.5) |

| Single mothera | 16 (8.0) | 14 (7.0) |

| Mother, higher educationb | 96 (47.5) | 88 (44.4) |

| Monthly family income, mean (SD), US dollars | 567 (492) | 536 (430) |

| ATB use in the last month of pregnancy | 41 (20.9) | 39 (20.4) |

| Multiple pregnancy | 45 (21.6) | 47 (22.9) |

| Preeclampsia/eclampsia | 62 (29.8) | 60 (29.3) |

| Peripartum infection | 54 (28.6) | 50 (26.2) |

| Peripartum fever | 18 (9.3) | 16 (8.2) |

| Chorioamnionitis (clinical or suspected diagnosis) | 63 (30.9) | 58 (28.6) |

| Premature rupture of membranes | 76 (36.9) | 58 (29.3) |

| Antenatal steroidsc | 152 (82.6) | 141 (75.0) |

| Cesarean delivery | 168 (80.8) | 164 (80.0) |

| Antibiotics during labor | 68 (38.2) | 52 (28.9) |

| Neonatal | ||

| Gestational age at birth, mean (SD), weeks | 30.8 (2.8) | 30.8 (3.2) |

| Birth weight, mean (SD), g | 1382 (371) | 1378 (353) |

| Small for gestational age | 57 (27.3) | 59 (28.8) |

| Male sex | 114 (54.5) | 116 (56.6) |

| 5-min Apgar score, mean (SD) | 8.5 (1.1) | 8.3 (1.2) |

| Neonatal resuscitation needed | 117 (56.3) | 119 (58.0) |

| Early-onset sepsis | 90 (43.1) | 92 (44.9) |

| Post randomization risk factors for LOS until discharge or death, mean (SD) | ||

| Hospitalization in NICU, days | 14.8 (18.7) | 16.2 (18.1) |

| CVC use, daysd | 12.2 (17.0) | 14.2 (16.5) |

| Mechanical ventilation, days | 3.9 (10.2) | 4.0 (10.4) |

| CPAP use, days | 3.4 (7.4) | 3.5 (5.9) |

| Treatment with antibiotics, days | 10.3 (14.8) | 11.3 (15.0) |

| Use of steroids, days | 0.1 (1.4) | 0.1 (0.9) |

| Use of H2-receptor antagonists, days | 0.6 (2.1) | 0.4 (1.5) |

| TPN use, days | 9.2 (13.7) | 10.9 (13.4) |

| Age at establishment of full enteral feeding, days | 6.8 (8.8) | 7.2 (9.9) |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; LOS, late-onset sepsis; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit; CVC, central venous catheters; CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; TPN, total parenteral nutrition.

Unmarried or without a partner.

Higher education defined as post-secondary education including college, university and/or institutes of technology.

At least one dose administered.

Central inserted, peripheral inserted central catheter (PICC) and umbilical catheter.

During the 8 weeks of intervention, there were 97 culture-proven or probable sepsis episodes (43 in LF vs. 54 in placebo). The mean day of onset of first culture-proven LOS was 15.2±10.4 in the BLF group vs. 15.0± 12.1 in placebo. Among 67 positive blood cultures, there were fewer gram-negative bacteria, CoNS and Candida isolates in the BLF group. However, there was no significant effect of BLF on the primary composite outcome adjusting for clustering within hospital and BW; hazard ratio (HR) 0.73 (95% CI, 0.42–1.26, p=0.26) (Table 2). Among VLBW infants, the primary outcome occurred in 19 (14.6%) infants in the BLF group vs. 27 (21.4%) in placebo, HR 0.69 (95%CI, 0.39–1.25, P = .22).

Table 2.

Late-onset sepsis (LOS) and secondary outcomes

| Outcomesa | Lactoferrin (n=209) | Placebo (n=205) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sepsis outcomes | No. (%) | No. (%) | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) |

| Primary composite outcome, No. (%) | 22 (10.5) | 30 (14.6) | 0.73 (0.42 – 1.26) |

| First culture-proven LOS, No. (%) | 17 (8.1) | 22 (10.7) | |

| Sepsis-related deaths, No. (%) | 5 (2.6) | 8 (4.4) | |

| Primary composite outcome by birth weight group, n/N (%) | |||

| 500g - 1000g | 7/39 (17.9) | 15/38 (39.5) | 0.45 (0.18 – 1.10)b |

| 1001g - 1500g | 12/91 (13.6) | 12/88 (13.8) | 0.99 (0.45 – 2.21) |

| 1501g - 2000g | 3/79 (3.8) | 3/79(3.8) | 1.04 (0.21 – 5.16) |

| First culture-proven or probable LOS, No. (%) | 34 (16.3) | 44 (21.5) | 0.76 (0.48 – 1.19) |

| All culture-proven and probable LOSc, No. (%) | 43 (43.1) | 54 (53.6) | 0.82 (0.55 – 1.23) |

| Isolated pathogens (all culture-proven and probable sepsis), No. | 29 | 38 | |

| Gram negative bacteriad | 8 | 12 | |

| Gram positive bacteria (excluding CoNS)e | 5 | 3 | |

| CoNS | 15 | 19 | |

| Candida | 1 | 4 | |

| Secondary outcomes | No. (IR/104)f | No. (IR/104)f | Rate ratio (95% CI) |

| NEC Bell’s stage ≥2 | 5 (0.5) | 11 (11) | 0.46 (0.16 – 1.31) |

| ROP requiring surgery | 8 (8.4) | 11 (11.4) | 0.74 (0.30 – 1.83) |

| Intraventricular hemorrhage III-IV (3–4week)c | 3 (1.9) | 7 (4.6) | 0.42 (0.17 – 1.02) |

| Periventricular leukomalacia (3–4weeks)c | 2 (1.3) | 4 (2.6) | 0.48 (0.23 – 1.01) |

| Bronchopulmonary dysplasiac | 25 (12.0) | 26 (12.7) | 0.94 (0.85 – 1.05) |

| Serious infections prior to discharge | |||

| Pneumonia | 24 (40.3) | 25 (40.1) | 1.01 (0.58 – 1.78) |

| Meningitis / encephalitis | 4 (6.4) | 6 (9.5) | 0.64 (0.18 – 2.27) |

| UTI | 7 (11.2) | 4 (6.3) | 0.50 (0.05 – 5.52) |

| Conditions requiring re-hospitalization | |||

| Pneumonia | 20 (1.6) | 21 (1.6) | 1.00 (0.54 – 1.84) |

| Meningitis/encephalitis | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.2) | 0.51 (0.05 – 5.62) |

| UTI | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.2) | 0.50 (0.55 – 5.52) |

| Bronchiolitis | 6 (0.5) | 18 (1.4) | 0.34 (0.14 – 0.86)g |

| Wheezing | 7 (0.6) | 3 (0.2) | 2.49 (0.64 – 9.64) |

| Pertussis-like syndrome | 3 (0.2) | 3 (0.2) | 1.04 (0.21 – 5.15) |

| Mortality | |||

| Mortality in the first 8 weeks | 29 (29.8) | 24 (24.5) | 1.23 (0.72 – 2.11) |

| In-hospital mortality | 30 (48.1) | 26 (40.7) | 1.13 (0.67 – 1.91) |

| Overall 24-month mortality | 37 (2.6) | 29 (2.1) | 1.32 (0.81 – 2.15) |

| Infection-associated mortalityh | 17 (1.3) | 16 (1.2) | 1.13 (0.57 – 2.24) |

Abbreviations: LOS, late-onset sepsis; CoNS, coagulase-negative staphylococci; NEC; necrotizing enterocolitis; ROP, retinopathy of prematurity; UTI, urinary tract infection.

Adjusted for hospital and weight category (≤1000 g, 1001–1500 g, 1501–2000 g), considering follow up from day 3 to day 56 or death for all neonatal outcomes for all infants.

p=0.08

Cumulative incidences/100 cases and cumulative incidence ratio (95% CI).

Klebsiella (4 and 3), E. coli (3 and 3), Enterobacter (1 and 2), Pseudomona (0 and 2), Acinetobacter (0 and 1) and Empedobacter (0 and 1) among BLF and placebo groups respectively.

Enterococcus (3 and 1), Staphylococcus aureus (1 and 2) and Streptococcus (1 and 0) among BLF and placebo groups respectively.

IR/104, Incidence rate per 10,000 child-days.

p=0.02

Mortality associated with sepsis and pneumonia, excluding early-onset sepsis. No infant died of meningitis/encephalitis, UTI or diarrhea.

There were no significant differences in secondary outcomes of aim 1, except for less re-hospitalization due to bronchiolitis in the BLF group; rate ratio, 0.34 (95% CI, 0.14–0.86, p=0.02) (Table 2). The length of hospitalization was 31.8±25.6 days in the BLF group vs. 33.2±22.4 days in the placebo group. Mortality rates were similar between groups (Table 2). Overall mortality was high among extremely-low-birth-weight infants (ELBW, <1000g), 59.0% (23/39) in the BLF group vs. 52.6% (20/38) in placebo; as well as sepsis-related mortality: 20.5% (8/39) in BLF vs. 28.9% (11/38) in placebo. The mortality rates for ELBW infants reported are similar to rates in the same NICUs and others in Lima.

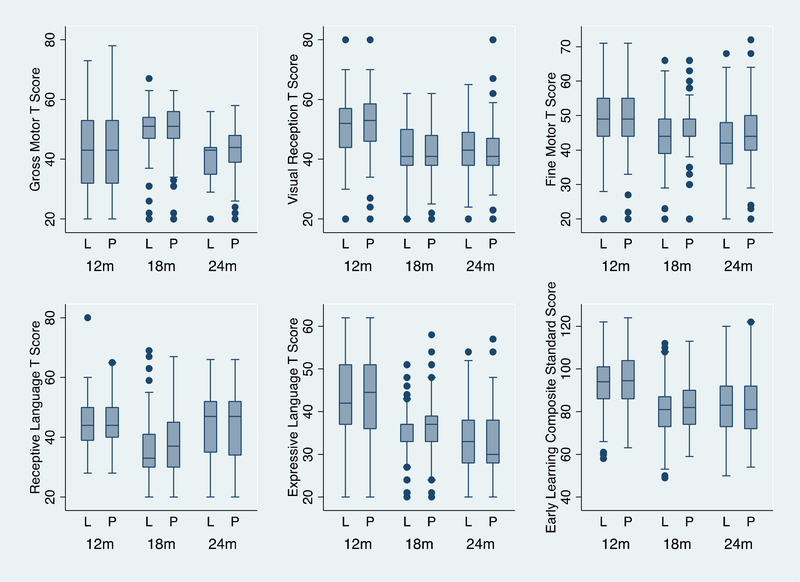

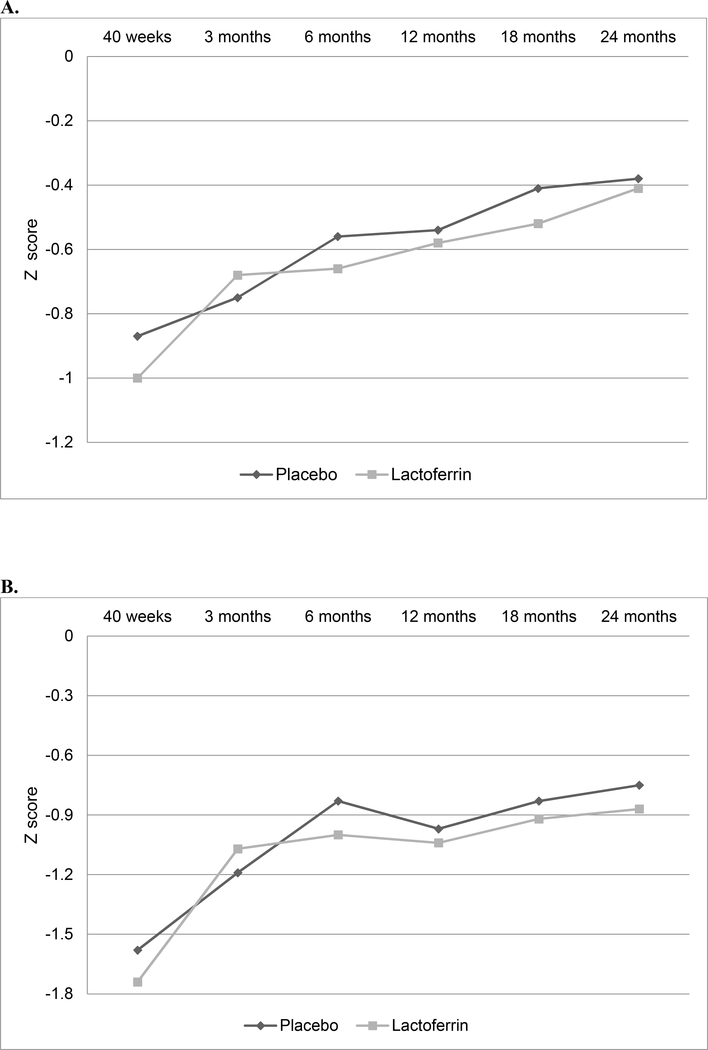

For Aim 2, 152 infants (72.7%) completed the 24 month follow-up in the BLF group (20 dropped out, 37 died) vs. 158 infants (77.1%) in placebo (18 dropped out, 29 died). The 24 month drop-out rate was 9.2% (38/414). Follow-up was completed in October 2016. Table 3 (available at www.jpeds.com) shows demographic information comparing infants lost to follow up with those who were seen for the developmental follow up at 24 months. A total of 899 Mullen tests were performed (Figure 2; available at www.jpeds.com). The Mullen, Bayley-III and ABAS-II results at 24 months were similar among groups (Table 4). Neurodevelopmental delay in VLBW infants was 18.8% (15/80) in the BLF group vs. 21.2% (18/85) in placebo (Table 5; available at www.jpeds.com). Growth outcomes were comparable during the 2-year follow-up (Figure 3; available at www.jpeds.com).

Table 3.

Demographic characteristics of infants that completed the 24-month evaluation and infants lost to follow-up.

| Mullen at 24 months | Dead | Lost to follow-up | Cerebral palsy | Othera | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lactoferrin | ||||||

| n | 143 | 37 | 20 | 5 | 4 | 209 |

| Birth weight, g, mean (SD) | 1462 (323) | 978 (325) | 1572 (274) | 1118 (228) | 1655 (185) | 1382 (371) |

| Gestational age at birth, weeks, mean (SD) | 31.4 (2.4) | 28.2 (2.5) | 31.8 (2.8) | 27.8 (2.7) | 31.0 (3.3) | 30.8 (2.8) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 79 (55.2) | 19 (51.4) | 9 (45.0) | 3 (60.0) | 4 (100.0) | 114 (54.6) |

| SGA, n (%) | 37 (25.9) | 14 (37.8) | 5 (25.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (25.0) | 57 (27.3) |

| Placebo | ||||||

| n | 149 | 29 | 18 | 6 | 3 | 205 |

| Birth weight, g, mean (SD) | 1432 (309) | 947 (248) | 1661 (313) | 1214 (295) | 1475 (117) | 1378 (353) |

| Gestational age at birth, weeks, mean (SD) | 31.2 (2.8) | 27.6 (2.8) | 32.8 (3.1) | 29.8 (4.1) | 31.3 (1.5) | 30.8 (3.2) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 87 (58.4) | 12 (41.4) | 11 (61.1) | 3 (50.0) | 3 (100.0) | 116 (56.6) |

| SGA, n (%) | 46 (30.9) | 5 (17.2) | 6 (33.3) | 1 (16.7) | 1 (33.3) | 59 (28.8) |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; SGA, small for gestational age

Other: Completed the 24-month follow up, but did not completed the Mullen test

Figure 2.

Mullen Scores at 12, 18 and 24 months corrected age among infants supplemented with lactoferrin (L) or placebo (P) in the neonatal period.

A total of 299 tests were performed at 12 months, 299 at 18 months and 301 at 24 months corrected age; 438 in the lactoferrin group and 461 in the placebo.

Table 4.

Neurodevelopmental and growth outcomes at 24 months corrected age

| Outcomea | Lactoferrin | Placebo | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mullen, mean (SD) | (n=143) | (n=149) | Adjusted difference (95% CI) |

| Composite | 83.3 (13.6) | 82.6 (13.1) | 0.62 (−3.07 – 4.31) |

| Gross Motor | 41.5 (7.0) | 42.5 (7.9) | −1.04 (−3.38 – 1.31) |

| Visual Reception | 43.2 (9.4) | 42.6 (9.2) | 0.66 (−1.88 – 3.20) |

| Fine Motor | 43.2 (10.3) | 43.8 (9.9) | −0.53 (−1.91 – 0.84) |

| Receptive Language | 44.2 (11.5) | 43.9 (12.2) | 0.23 (−2.83 – 3.29) |

| Expressive Language | 33.8 (7.7) | 32.9 (7.4) | 0.97 (−1.48 – 3.42) |

| Composite combined (12, 18 and 24 months)b, mean | 84.1 | 85.2 | −1.34 (−3.40 – 0.73) |

| Bayley-III, mean (SD) | (n=112) | (n=112) | Adjusted difference (95% CI) |

| Cognitive | 94.0 (8.3) | 94.7 (6.9) | −0.76 (−2.11 – 0.59) |

| Language | 86.9 (9.6) | 85.7 (9.0) | 1.26 (−1.74 – 4.24) |

| Motor | 95.4 (10.7) | 96.3 (10.9) | −0.91 (−2.02 – 0.21) |

| Social emotional score | 110.7 (20.4) | 111.7 (17.5) | −1.00 (−5.66 – 3.66) |

| Neurodevelopmental delay | n/N (%) | n/N (%) | Relative risk (95% CI) |

| Mullen Composite ≤70 | 22/143 (15.4) | 30/149 (20.1) | 0.76 (0.44 – 1.32) |

| Bayley-III Cognitive <85 | 8/112 (7.1) | 5/112 (4.5) | 1.60 (0.68 – 3.75) |

| Bayley-III Language <85 | 40/110 (36.4) | 46/110 (41.8) | 0.87 (0.57 – 1.31) |

| Bayley-III Motor <85 | 12/110 (10.9) | 12/110 (10.9) | 1.00 (0.46 – 2.16) |

| ABAS-II, GAC <70 | 42/111 (37.8) | 39/112 (34.8) | 1.09 (0.84 – 1.41) |

| M-CHAT-R, Score ≥3c | 16/126 (12.7) | 12/125 (9.6) | 1.32 (0.69 – 2.54) |

| Neurodevelopmental impairment (NDI)d | 31/147 (21.1) | 39/153 (25.5) | 0.83 (0.56 – 1.22) |

| Growth outcomes | n/N (%) | n/N (%) | Relative risk (95% CI) |

| Weight-for-length Z-score ≤−2(wasting) | 4/117 (3.4) | 6/125 (4.1) | 0.71 (0.24 – 2.14) |

| Length-for-age Z-score ≤−2(stunting) | 15/117 (12.8) | 15/125 (12.0) | 1.07 (0.54 – 2.11) |

| Weight-for-age Z-score ≤−2(underweight) | 9/120 (7.5) | 13/126 (10.3) | 0.73 (0.29 – 1.85) |

| Head circumference Z-score ≤−2 (microcephaly) | 7/103 (6.8) | 7/113 (6.2) | 1.10 (0.56 – 2.15) |

Abbreviations: Mullen, Mullen Scales of Early Learning; SD, standard deviation; Bayley-III, Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development Third Edition; ABAS-II, Adaptive Behavior Assessment System Second Edition; GAC, general adaptive composite; M-CHAT-R, Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers-Revised; NDI, neurodevelopmental impairment.

Adjusted for hospital and weight category (≤1000 g, 1001–1500 g, 1501–2000 g), excluding patients with cerebral palsy (5, BLF; 7, placebo). Corrected age is reported for all outcomes.

Generalized estimating equations.

Medium to high risk for autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

NDI (composite outcome): defined as the presence of any of the following: Early Learning Composite Mullen Score ≤ 70, moderate to severe cerebral palsy, bilateral hearing impairment requiring amplification or bilateral blindness.

Table 5.

Neurodevelopmental outcomes at 24 month corrected age in VLBW infants

| Outcome | Lactoferrin | Placebo | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mullena, mean (SD) | (n=80) | (n=85) | Adjusted difference (95% CI) |

| Composite | 83.5 (14.4) | 81.8 (12.3) | 1.59 (−7.12 – 10.30) |

| Gross Motor | 41.6 (7.0) | 41.7 (7.6) | −0.09 (−2.20 – 2.01) |

| Visual Reception | 43.7 (9.3) | 42.0 (8.7) | 1.68 (−4.25 – 7.61) |

| Fine Motor | 42.0 (10.1) | 42.8 (9.1) | −0.80 (−4.43 – 2.83) |

| Receptive Language | 44.7 (11.9) | 43.5 (12.2) | 1.23 (−5.20 – 7.66) |

| Expressive Language | 34.3 (7.7) | 33.2 (7.3) | 1.13 (−5.67 – 7.92) |

| Composite combined (12, 18 and 24 months)b, mean | 84.1 | 85.2 | −1.34 (−3.40 – 0.73) |

| Bayleya, mean (SD) | (n=63) | (n=66) | Adjusted difference (95% CI) |

| Cognitive | 94.3 (9.2) | 94.5 (6.8) | −1.22 (−2.87 – 0.43) |

| Language | 86.0 (10.6) | 85.6 (10.0) | 0.37 (−5.78 – 6.52) |

| Motor | 95.4 (12.5) | 96.9 (11.3) | −1.44 (−2.89 – 0.01) |

| Social emotional score | 113.2 (18.4) | 111.7 (18.1) | 1.45 (−0.78 – 3.67) |

| Neurodevelopmental delaya | n/N (%) | n/N (%) | Relative risk (95% CI) |

| Mullen Composite ≤70 | 15/80 (18.8) | 18/85 (21.2) | 0.89 (0.40 – 1.95) |

| Bayley Cognitive <85 | 6/63 (9.5) | 4/66 (6.1) | 1.57 (0.54 – 4.61) |

| Bayley Language <85 | 27/61 (44.3) | 25/65 (38.5) | 1.15 (0.72 – 1.84) |

| Bayley Motor <85 | 8/62 (12.9) | 7/65 (10.8) | 1.20 (0.84 – 1.71) |

| ABAS-II, GAC <70 | 24/59 (40.7) | 21/64 (32.9) | 1.24 (0.86 – 1.80) |

| M-CHAT-R, Score ≥3c | 9/72 (12.5) | 8/72 (11.1) | 1.13 (0.81 – 1.56) |

Abbreviations: Mullen, Mullen Scales of Early Learning (MSEL); SD, standard deviation; Bayley-III, Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development Third Edition (BSID-III); ABAS-II, Adaptive Behavior Assessment System Second Edition; GAC, general adaptive composite; M-CHAT-R, Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers-Revised

Adjusted for hospital and weight category (≤1000 g, 1001–1500 g, 1501–2000 g), excluding patients with cerebral palsy (5, LF; 7, placebo). Corrected age is reported for all outcomes.

Generalized estimating equations.

Medium to high risk for autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

Figure 3.

Comparison of growth measurements from 40 weeks to 24 months corrected age. A. Weight-for-age Z-scores (mean); B. Length-for-age Z scores (mean); C. Weight-for-length Z-scores (mean); D. Head circumference Z-scores (mean).

The infants’ nutritional characteristics were similar in both groups, except for more motheŕs milk intake in the placebo group (Table 6); a higher percentage of child-days of observation in which infants received only mother’s milk (32.6% vs. 38.0%, p<0.001). In addition, we found high levels of human-LF in breast milk in both arms (Table 6). We explored the amount of human-LF consumed by the infants and found non-significant higher mean human milk LF intake within the first week of life in the placebo group (Table 6). Post-hoc analyses adjusting for human-LF intake showed no statistically significant differences for the primary composite outcome, HR, 0.87 (95% CI, 0.46–1.63). No differences between groups were found adjusting for breast milk consumption (cc/kg) either, HR, 0.67 (95% CI, 0.39–1.18).

Table 6.

Nutritional characteristics and human milk lactoferrin intake

| Characteristic | Lactoferrin (n=209) mean (SD) |

Placebo (n=205) mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Age of enteral feeding initiation in days | 2.2 (3.1) | 2.1 (3.3) |

| Age of full enteral feeding establishment in days | 6.8 (8.8) | 7.2 (9.9) |

| Daily mother’s milk consumption in cc/kg during complete hospitalization | 50.2 (56.0) | 54.4 (54.8) |

| Percentage of daily mother’s milk consumption during complete hospitalization | 53.7 (42.0) | 60.0 (40.7) |

| Cumulative mother’s milk intake entire hospitalization in L, mean | 2.0 | 2.3 |

| Number of days with at least 1 direct oral take of breast milk | 5.5 (7.2) | 5.8 (6.7) |

| Direct daily oral takes of breast milk | 2.2 (0.9) | 2.3 (0.9) |

| 6284 child-days | 6461 child-days | |

| No. (%) | No. (%) | |

| NPO | 613 (9.9) | 648 (10.2) |

| Use of TPN | 1931 (30.7) | 2231 (34.6) |

| Fed only with mother’s milk | 2019 (32.6) | 2414 (38.0)a |

| Fed only with artificial formula | 1132 (18.3) | 793 (12.5) |

| Fed both with breast milk and artificial formula | 2421 (39.1) | 2490 (39.2) |

| Breast milk human lactoferrin (hLF) concentration and intake | mean (SD) [n]b | mean (SD) [n]b |

| hLF concentration in colostrum, mg/mL | 14.3 (7.3) [145] | 15.6 (8.6) [132] |

| hLF concentration at 1 month, mg/mL | 9.9 (6.1) [130] | 10.8 (6.5) [129] |

| hLF intake from colostrum, mg/day | 266 (267) [141] | 317 (363) [126] |

| hLF intake at one month, mg/day | 554 (571) [57] | 663 (676) [64] |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; NPO, nothing per mouth; TPN, total parenteral nutrition; hLF, breast milk human lactoferrin.

p<0.001

[n], number of infants with hLF determination in their mother’s milk sample.

Adverse Events: Signs or symptoms of allergic reactions or intolerance were closely monitored. Among 12,745 child-days of observation, vomiting was present in 0.2% vs. 0.1% in the BLF and placebo group respectively, >2cm increase in abdominal circumference in 0.3% vs. 0.8%, and diarrhea in 0.1% in both. No infant was diagnosed with cowś milk allergy. There were 141 re-hospitalizations (67, B LF group; 74, placebo) and 66 deaths (37, BLF; 29 placebo); the DSMB evaluated all serious adverse events, none was found attributable to the intervention.

Overall the purity of the two BLF lots was similar at 95.3% and 94.8%. The percentage of label claim was slightly less for one BLF lot (89.0% vs. 97.5%) but still very close to the industry standard 90–110% of label claim. Bacterial endotoxin was <0.500EU/mg for both lots.

DISCUSSION

This study found that BLF supplementation in low birth weight infants had no significant effect on LOS, sepsis-associated death, neurodevelopment and growth outcomes. A non-significant 55% reduction in the risk for the composite outcome (LOS and sepsis-associated death) was observed in infants with birth weight <1000 g (ELBW), similar to Manzonís studies in Italy; they found significantly lower incidence of LOS mainly among ELBW infants.10,11 The ELFIN study17 found no significant effect in the subgroup analysis by gestational age. Other previous trials have not analyzed BLF effect by birth weight category, due to their small sample size.13–16,18 ELBW infants are the most vulnerable population33 and most likely the ones that will benefit from this intervention. In the first days after birth, small infants receive minimal amounts of human milk; therefore, BLF supplementation may be critical during this period when they need additional protection.

Fewer pathogens were isolated from all culture-proven and probable sepsis episodes in the lactoferrin group, including fewer gram negative bacteria and Candida species (9 vs. 16 isolates). BLF may target pathogens in the gut, by modulating the intestinal microbiome and preventing translocation of bacteria from the gut.7 On the other hand, it is unlikely that BLF can target CoNS, as it predominantly originates from the skin.

Our study differs from previous trials in several aspects. We used a BLF dose based on the infantś weight (200 mg/Kg/day), whereas previous studies used a fixed dose (100, 200, 300 mg/day),10–13, 15,16 The study by Kaur et al14, our pilot study18 (200 mg/Kg/day) and the ELFIN study17 (150 mg/Kg/day) used weight-based dosing. The dose chosen was the effective dose in the smallest infants (500g) in the Manzoni study10. Moreover, we administered BLF three times daily for 8 weeks to mimic the effect of breast milk LF, administered continuously with each feeding, during the period at-risk; most studies used BLF once daily for 4 weeks or until discharge. All trials including ours used BLF, except for the study by Sherman et al, with recombinant human-LF.15 LF purified from human and bovine milk have similar structural and biochemical properties; their bioactivity, assessed in-vitro and in animal models, is comparable, but not identical.5

A contribution of our study to the body of knowledge of BLF in neonates is the neurodevelopmental and long-term follow-up. If LF becomes a standard of care it needs to be demonstrated to be safe. Although we were not able to prove our hypothesis that BLF improves neurodevelopment in preterm neonates, safety was demonstrated because outcomes for infants in the BLF group were similar to those in the placebo group for neurodevelopmental delays and overall neurodevelopmental impairments. In both the BLF and placebo groups, Mullen expressive language subscale scores were lower than scores for gross motor, visual reception, fine motor and receptive language, as previously described for ELBW infants.34 Neonatal infections in very preterm infants are associated with worse neurodevelopment20,33 including higher incidence of cerebral palsy,35,36 representing an economic burden for families and society.37

We found significantly fewer re-hospitalizations for bronchiolitis in the BLF group. This was in line with a previous study;38 children receiving a BLF-enhanced formula had significantly fewer lower respiratory tract illnesses in the first year (0.5 vs. 1.5 episodes/year). This is worth exploring given the high burden of respiratory infections in preterm populations, especially in ELBW infants as they have the highest rate of respiratory hospital readmissions in early childhood.39

Some prior trials showed significantly decreased rates of sepsis but others,16–18 including our pilot study18 and the ELFIN trial17 (2203 participants) had negative results, as did the current study. There are several explanations for this discordant outcome. First, this study was underpowered; the overall number of sepsis episodes in both arms was lower than expected. For our sample size calculation we estimated a 25% sepsis rate in the placebo group; the final LOS rate was only 10.7%, mainly because infants >1500g contributed few sepsis episodes; with <4% sepsis rate. The discrepancy between the pre-study LOS rates and the actual ones, probably related to our more strict definition of LOS due to CoNS. Second, the infants had higher human-LF intake from colostrum and breast milk40 than prior studies.41 Therefore, the high LF levels in human milk and the high breast milk consumption overall could have diluted the effect of BLF. Third, another possible explanation for the lack of effect is the quality and purity of the BLF. However, both BLF preparations were similar, with optimal purity and no bacterial endotoxin. This analysis is critical, because there are many commercial BLF preparations with potentially different degrees of denaturation and purity42 and no standard guidelines for the quality of products in clinical studies.

This study has some limitations. First, we had a small number of enrolled VLBW infants. Initially, we did not plan a quota for each birth weight category; however, in the middle of the study, reviewing the sepsis rates by birth weight category (blinded to the treatment allocation), we decided to stop enrolling infants >1500g to increase the power of the study; nevertheless, the number of VLBW infants (256) enrolled at completion of the sample size (414), was not sufficient. Second, the clinical evaluation of suspected sepsis episodes was done according to standard care of each hospital; therefore, the appropriateness and timing of blood cultures and antibiotic use43 varied between centers; however, the analysis of the main study outcome was performed adjusting for this variable. Third, the Mullen test is not validated in preterm infants or our population. With the company’s approval (Pearson, San Antonio, TX), we translated the test from English to Spanish and back-translated to English, but have not done a validation study. However, the Bayley-III, validated in Spanish, showed similar results.

In summary, supplementation with BLF did not reduce the incidence of sepsis in infants with birth weights <2000g but the use of BLF as a broad-spectrum antimicrobial protective protein may have potential effect in infants <1000g on LOS that needs to be confirmed in future trials. One additional large ongoing study, the LIFT trial (Australia)44 will provide further evidence on BLF effectiveness on sepsis, mortality and neurodevelopment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank all members of the participating hospitals for their support and collaboration in the study. We thank the pediatricians, study research nurses, and neonatal nurses from each hospital for their dedication and careful work in this project. We thank Gary Gelbfish for the BLF quality and purity studies. We also thank the members of the DSMB for their independent and critical review of the data and safety of the study. Finally, we thank Jan Jacobs and Veerle Cossey for the critical review of the manuscript.

Funded by the National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (NICHD) (R01-HD067694). The funder of the study had no role in the study design; data collection, analysis, interpretation; or report writing. The corresponding author had full access to data and final responsibility for deciding to publish. M.R. serves on the Editorial Board for The Journal of Pediatrics. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix

Additional members of the NEOLACTO Research Group

Pilar Medina, MD, Department of Pediatrics, School of Medicine, Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, Lima, Peru.

María Rivas, MD, Hospital Nacional Docente Madre Niño San Bartolome, Lima, Peru Irene Chea, PharmD, Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, Lima, Peru.

Alicia Villar, MD, School of Medicine, Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, Lima, Peru. Carolina Navarro, MD, School of Medicine, Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, Lima, Peru. Lourdes Tucto, RN, Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, Lima, Peru.

Patricia Mallma, MSc, School of Public Health and Administration, Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, Lima, Peru.

Renzo Calderon-Anyosa, MD, School of Medicine, Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, Lima, Peru

María Luz Rospigliosi, MD, Department of Pediatrics, School of Medicine, Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, Lima, Peru.

Geraldine Borda, MD, Department of Pediatrics, School of Medicine, Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, Lima, Peru.

Orialit Minauro, MD, Department of Pediatrics, School of Medicine, Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, Lima, Peru.

Verónica Webb, MD, Department of Pediatrics, School of Medicine, Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, Lima, Peru.

Erika Bravo, MD, Department of Pediatrics, School of Medicine, Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, Lima, Peru.

Karen Pacheco, MD, Department of Pediatrics, School of Medicine, Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, Lima, Peru.

Ana Lino, MD, Hospital Nacional Alberto Sabogal, Lima, Peru

Augusto Cama, MD, Hospital Nacional Alberto Sabogal, Lima, Peru

Raúl Llanos, MD, Hospital Nacional Guillermo Almenara, Lima, Peru

Oscar Chumbes, MD, Hospital Nacional Guillermo Almenara, Lima, Peru

Liliana Cuba, MD, Hospital Nacional Guillermo Almenara, Lima, Peru

Julio Tresierra, MD, Hospital Nacional Guillermo Almenara, Lima, Peru

Carmen Chincaro, MD, Hospital Nacional Guillermo Almenara, Lima, Peru

Alfredo Tori, MD, Hospital Nacional Guillermo Almenara, Lima, Peru

Footnotes

Data sharing statement

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vohr BR, Poindexter BB, Dusick AM, McKinley LT, Wright LL, Langer JC,et al. Beneficial effects of breast milk in the neonatal intensive care unit on the developmental outcome of extremely low birth weight infants at 18 months of age. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e115–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meinzen-Derr J, Poindexter B, Wrage L, Morrow A, Stoll B, Donovan E . Role of human milk in extremely low birth weight infants’ risk of necrotizing enterocolitis or death. J Perinatol 2009;29:57–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lechner BE, Vohr BR. Neurodevelopmental outcomes of preterm infants fed human milk: A systematic review. Clin Perinatol. 2017;44:69–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ballard O, Morrow AL. Human Milk Composition: Nutrients and Bioactive Factors. Pediatr Clin North Am 2013;60:49–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vogel HJ. Lactoferrin, a bird’s eye view. Biochem Cell Biol. 2012;90:233–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Embleton ND, Berrington JE, McGuire W, Stewart CJ, Cummings SP. Lactoferrin: Antimicrobial activity and therapeutic potential. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2013;18:143–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ochoa TJ, Sizonenko SV. Lactoferrin and prematurity: a promising milk protein? Biochem Cell Biol. 2016;95:22–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turin CG, Zea-Vera A, Pezo A, Cruz K, Zegarra J, Bellomo S, et al. Lactoferrin for prevention of neonatal sepsis. BioMetals. 2014;27:1007–1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pammi M, Suresh G. Enteral lactoferrin supplementation for prevention of sepsis and necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017; 6:CD007137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manzoni P, Rinaldi M, Cattani S, Pugni L, Romeo MG, Messner H, et al. Bovine Lactoferrin Supplementation for Prevention of Late-Onset Sepsis in Very Low-Birth-Weight Neonates: A Randomized Trial. JAMA. 2009;302:1421–1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manzoni P, Stolfi I, Messner H, Cattani S, Laforgia N, Romeo MG, et al. Bovine lactoferrin prevents invasive fungal infections in very low birth weight infants: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2012;129:116–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manzoni P, Meyer M, Stolfi I, Rinaldi M, Cattani S, Pugni L, et al. Bovine lactoferrin supplementation for prevention of necrotizing enterocolitis in very-low-birth-weight neonates: a randomized clinical trial. Early Hum Dev. 2014;90:S60–S65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akin I, Atasay B, Dogu F, Okulu E, Arsan S, Karatas HD, et al. Oral Lactoferrin to Prevent Nosocomial Sepsis and Necrotizing Enterocolitis of Premature Neonates and Effect on T-Regulatory Cells. Am J Perinatol 2014;31:1111–1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaur G, Gathwala G. Efficacy of Bovine Lactoferrin Supplementation in Preventing Late-onset Sepsis in low Birth Weight Neonates: A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. J Trop Pediatr 2015;61:370–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sherman MP, Adamkin DH, Niklas V, Radmacher P, Sherman J, Wertheimer, et al. Randomized Controlled Trial of Talactoferrin Oral Solution in Preterm Infants. J Pediatr. 2016;175:68–73.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barrington KJ, Assaad M-A, Janvier A. The Lacuna Trial: a double-blind randomized controlled pilot trial of lactoferrin supplementation in the very preterm infant. J Perinatol 2016;36:666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.ELFIN trial investigators group. Enteral lactoferrin supplementation for very preterm infants: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet. 2019;393:423–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ochoa TJ, Zegarra J, Cam L, Llanos R, Pezo A, Cruz K, et al. Randomized controlled trial of lactoferrin for prevention of sepsis in peruvian neonates less than 2500 g. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2015;34:571–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adams-Chapman I, Stoll BJ. Neonatal infection and long-term neurodevelopmental outcome in the preterm infant. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2006;19:290–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Vliet EOG, de Kieviet JF, Oosterlaan J, van Elburg RM. Perinatal infections and neurodevelopmental outcome in very preterm and very low-birth-weight infants: a meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:662–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mullen EM. Mullen Scales of Early Learning Manual. American Guidance Service; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bayley N Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development. Harcourt Assessment, Psych. Corporation; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Girault JB, Langworthy BW, Goldman BD, Stephens RL, Cornea E, Reznick JS, et al. The Predictive Value of Developmental Assessments at 1 and 2 for Intelligence Quotients at 6. Intelligence. 2018;68:58–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stephens RL, Langworthy B, Short SJ, Goldman BD, Girault JB, Fine JP, et al. Verbal and nonverbal predictors of executive function in early childhood. J Cogn Dev. 2018;19:182–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Atukunda P, Muhoozi GKM, van den Broek TJ, Kort R, Diep LM, Kaaya AN, et al. Child development, growth and microbiota: follow-up of a randomized education trial in Uganda. J Glob Health. 2019;9:010431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harrison P, Oakland T. Adaptive Behavior Assessment System-Second Edition. San Antonio TX: The Psychological Corporation; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robins DL, Casagrande K, Barton M, Chen C-MA, Dumont-Mathieu T, Fein D. Validation of the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers, Revised With Follow-up (M-CHAT-R/F). Pediatrics. 2014;133:37–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stoll BJ, Hansen N, Fanaroff AA, Wright LL, Carlo WA, Ehrenkranz RA, et al. Late-onset sepsis in very low birth weight neonates: the experience of the NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Pediatrics. 2002;110:285–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haque K Definitions of bloodstream infection in the newborn. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005;6:S45–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zea-Vera A, Turin CG, Ochoa TJ. [Unifying criteria for late neonatal sepsis: proposal for an algorithm of diagnostic surveillance]. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica. 2014;31:358–363. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnson S, Moore T, Marlow N. Using the Bayley-III to assess neurodevelopmental delay: which cut-off should be used? Pediatr Res. 2014;75:670–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anderson PJ, Burnett A. Assessing developmental delay in early childhood - concerns with the Bayley-III scales. Clin Neuropsychol. 2017;31:371–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Adams-Chapman I, Fanaroff AA, Hintz SR, Vohr B, et al. Neurodevelopmental and Growth Impairment Among Extremely Low-Birh-Weight Infants With Neonatal Infection. JAMA. 2004;292:2357–2365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adams-Chapman I, Bann C, Carter SL, Stoll BJ. Language Outcomes Among ELBW Infants in Early Childhood. Early Hum Dev 2015;91:373–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mitha A, Foix-L’Hélias L, Arnaud C, Marret S, Vieux R, Aujard Y, et al. Neonatal infection and 5-year neurodevelopmental outcome of very preterm infants. Pediatrics. 2013;132:e372–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alshaikh B, Yusuf K, Sauve R. Neurodevelopmental outcomes of very low birth weight infants with neonatal sepsis: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Perinatol. 2013;33:558–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saigal S, Doyle LW. An overview of mortality and sequelae of preterm birth from infancy to adulthood. The Lancet. 2008;371:261–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.King JC, Cummings GE, Guo N, Trivedi L, Readmond BX, Keane V, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled, pilot study of bovine lactoferrin supplementation in bottle-fed infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;44:245–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Doyle LW, Ford G, Davis N. Health and hospitalisations after discharge in extremely low birth weight infants. Semin Neonatol 2003;8:137–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Turin CG, Zea-Vera A, Rueda MS, Mercado E, Carcamo CP, Zegarra J, et al. Lactoferrin concentration in breast milk of mothers of low-birth-weight newborns. J Perinatol. 2017;37:507–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rai D, Adelman AS, Zhuang W, Rai GP, Boettcher J, Lonnerdal B. Longitudinal Changes in Lactoferrin Concentrations in Human Milk: A Global Systematic Review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2014;54:1539–1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang B, Timilsena YP, Blanch E, Adhikari B. Lactoferrin: Structure, function, denaturation and digestion. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr September 2017:1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rueda MS, Calderon-Anyosa R, Gonzales J, Turin CG, Zea-Vera A, Zegarra J, et al. Antibiotic Overuse in Premature Low Birth Weight Infants in a Developing Country. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2019;38:302–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martin A, Ghadge A, Manzoni P, Lui K, Brown R, Tarnow-Mordi W. Protocol for the Lactoferrin Infant Feeding Trial (LIFT): a randomised trial of adding lactoferrin to the feeds of very-low birthweight babies prior to hospital discharge. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e023044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.