Abstract

The Aspergillus fumigatus CAS21 tannase was spray dried with β-cyclodextrin, Capsul® starch, soybean meal, lactose, and maltodextrin as adjuvants. The moisture content and water activity of the products ranged from 5.6 to 11.5% and from 0.249 to 0.448, respectively. The maximal tannase activity was achieved at 40–60 ºC and pH 5.0–6.0 for the powders containing β-cyclodextrin and Capsul® starch, which was stable at 40 ºC and 40–60 ºC for 120 min, respectively. For all the dried products, tannase retained its activity of over 80% for 120 min at pH 5.0 and 6.0. Salts and solvents influenced the activity of the spray-dried tannase. The activity of the spray-dried tannase was maintained when preserved for 1 year at 4 ºC and 28 ºC. Spray-dried tannase reduced the content of tannins and polyphenolic compounds of leather effluent and sorghum flour and catalyzed the transesterification reaction. The spray drying process stabilized the tannase activity, highlighting the potential of dried products for biotechnological applications.

Keywords: Aspergillus, Enzyme stabilization, Spray drying, Tannin, Tannin acyl hydrolase

Introduction

Tannase (tannin acyl hydrolase, E.C. 3.1.1.20) is an enzyme that catalyzes the hydrolysis of hydrolyzable tannins. Tannase acts on esters and depsidic bonds, releasing glucose and gallic acid from gallotannins or glucose and ellagic acid from ellagitannins (Govindarajan et al. 2016; Chávez-González et al. 2016; Dhiman et al. 2018). Tannins are secondary phenolic metabolites responsible for the astringency of fruits and vegetables and for the precipitation in juices and drinks. These molecules also influence the assimilation of nutrients in animal feed (Govindarajan et al. 2016; Kumar et al. 2018).

Microorganisms are the most important source for obtaining tannase due to the high synthesis, lower production cost, possibility of genetic modifications, and greater enzymatic stability (Aguilar-Zárate et al. 2014). Most of the tannases commercialized by different companies (Sangherb, China; Kikkoman, Japan; ASA Special enzyme, Germany) are produced by fungi, such as Aspergillus ficuum, Aspergillus oryzae, and Arxula adeninivorans LS3 (Govindarajan et al. 2016). These enzymes can be applied in a number of industrial sectors, such as in the processing of instant teas and in the manufacturing of drinks (Govindarajan et al. 2016; Dhiman et al. 2018). In the animal nutrition industry, tannase can be used to remove the tannins from feed, promoting beneficial effects, like the improvement of digestibility and assimilation of nutrients (Kumar et al. 2018). Tannase can also be applied in the treatment of tannin-rich effluents, such as those generated during the tanning process in the leather industry (Cavalcanti et al. 2018). The most important application of these enzymes is in the production of gallic acid, which is used in the chemical, pharmaceutical, and food industry as intermediates in the synthesis of propyl gallate, pyrogallol and trimethoprim (Yao et al. 2014; Chávez-González et al. 2016).

The maintenance of enzyme stability during storage is one of the challenges for obtaining enzymes for commercial purposes. Dehydrated formulations have advantages, such as greater stability, longer shelf-life, easy handling and transport, as well as storage at room temperature (Langford et al. 2018; Zhang et al. 2018). Spray drying is one of the methodologies used for the drying of enzymes, producing powders from liquid solutions in a single step (Lee et al. 2018; Abdel-Madeeg et al. 2019). Generally, the spray-dried powder presents high stability and resistance to oxidative degradation and microbial attack (Lee et al. 2018). Spray drying is widely applied in chemical, biochemical, food, and pharmaceutical industry, being effective, simple, and economic. It is possible to control the properties of the dried product through modifications in the compositions of the formulations and through optimization of the process variables (Langford et al. 2018; Lee et al. 2018). However, samples subjected to drying in spray dryers can lead to denaturation of proteins due to high temperatures, shear stress, and dehydration (Amara et al. 2016). The process is generally carried out with a gas temperature of 100 °C, which could impair conformational stability of some of the biological molecules (Zhang et al. 2018). Hence, the addition of compounds (adjuvants/carriers) that act as protectors to avoid denaturation and loss of biological activities is almost mandatory. Carbohydrates, gums, lipids, proteins, and surfactants are commonly the adjuvants used (Lee et al. 2018; Costa et al. 2015). Some properties should be considered when choosing an adjuvant, such as solubility, molecular weight, emulsifying and crystalline properties, as well as cost and product use (Ray et al. 2016; Lee et al. 2018). According to the adjuvant used, the properties of the powder product, such as bulk density, glass transition temperature, color index and texture, particle size, and solubility are differently affected (Lee et al. 2018).

An overview of the current literature reveals a number of reports on the use of the technique of spray drying for various enzymes, such as lysozyme (Amara et al. 2016), α-amylase (Obón et al. 2020), lipase (Torres et al. 2016), peptidase (Hamin Neto et al. 2014), cellulase (Libardi et al. 2020), β-galactosidase (Lipiäinen et al. 2018), trypsin (Zhang et al. 2018), phytase (Sato et al. 2014), savinase (Torres et al. 2016), avicelase, CMCase, and FPase (Sarteshnizi et al. 2018). However, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, no reports on spray drying of tannases in the presence of carbohydrates as carriers are available up to the present date.

Tannases from Aspergillus have interesting properties that can be employed for several industrial applications. Some of such applications have recently been demonstrated for the enzyme produced by the endophytic fungus A. fumigatus CAS21, which was able to remove tannins from leather effluents and produce propyl gallate (Cavalcanti et al. 2018). Thus, the aim of this study was to improve the enzymatic activity and demonstrate stability toward different temperatures, solvents, and storage periods of A. fumigatus CAS21 tannase by spray drying in the presence of different adjuvants. In addition, the potential application of the spray-dried enzyme was also investigated.

Materials and methods

Microorganism

The endophytic fungus Aspergillus fumigatus CAS21 was isolated from the bark of the cashew tree (Anacardium occidentale L.) (Cavalcanti et al. 2017) and stored in the Laboratory of Microbiology of the Faculdade de Filosofia, Ciências e Letras de Ribeirão Preto at the University of São Paulo, Brazil. The fungus was maintained on Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) slants at 37 ºC for 96 h and then stored at 4 ºC.

Tannase production

Submerged cultures (SbmF) were obtained with the inoculation of 1-mL spore suspension (105 spores mL−1) of the Aspergillus in a medium containing 0.1% (w/v) KH2PO4, 0.2% (w/v) MgSO4·7H2O, 0.1% (w/v) CaCl2, 0.3% (w/v) NH4Cl, and 0.1% (w/v) peptone, and 2% (w/v) tannic acid as additional carbon source. The culture medium was previously autoclaved at 120 °C and 1.5 atm for 20 min, and the tannic acid was sterilized by means of microfiltration using a syringe filter (0.22 μm) before being added to the medium (Cavalcanti et al. 2017). The cultures were kept at 37 °C for 24 h and shaking at 120 rpm. After cultivation, the medium was harvested using a vacuum pump and Whatman filter paper No. 1. The cell-free filtrate containing tannase was dialyzed overnight for 24 h at 4 °C against distilled water and used in the spray drying process.

Preparation of formulations

Five different formulations (samples) were prepared using a similar procedure. Adjuvants, such as β-cyclodextrin, Capsul® starch, soybean meal (< 106 μm), lactose, and maltodextrin DE 10 were added to the enzymatic extract at a concentration of 10% (w/v) for the protection of the enzyme. The samples were shaken for 2 h and then stored overnight for 15 h at 4 °C. The resulting formulations were submitted to spray drying.

Spray drying

The samples were spray dried using Lab-Plant SD-05 (Huddersfield, UK), with a drying chamber of 215 mm diameter and 500 mm height and operating in a co-current flow regime. The main components of the system were a feed system of the drying gas, temperature control system of the drying gas, and product-collecting system. The sample was fed into the feed system composed of a peristaltic pump and a two-fluid atomizer with an orifice diameter of 1.0 mm connected to an air compressor. The experimental conditions for drying were set as follows: Wg (drying air flow) 60 m3/h, Wsusp (sample feed rate) 4 g/min, Patm (spray pressure) 1.5 kgf/cm2, and Watm (atomization flow rate) 17 lpm. The inlet gas temperature was regulated at 100 °C and the air outlet temperature ranged from 55.25 to 59.75 °C. The collected powders were used to determine product recovery, physical, and chemical characteristics of the product by determining their moisture content, size distribution, and relative enzymatic activity.

Characterization of the spray-dried product

Water activity and moisture content

The water activity was measured using an Aqua Lab 4TEV water meter (Decagon—Devices Inc. Pullman, WA) at 25 ºC using the dew point sensor. Residual moisture content was determined with Karl Fischer titration on a Tritino plus 870 equipment (Metrohm Ltd., Herisau, Switzerland). The tests were performed in triplicate, and the results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

Particle size

Particle size of dried powders was determined using a light scattering Beckman Coulter LS 13 320 (Brea, CA, USA) coupled with a universal liquid module capable of analyzing a particle size range of 0.375–2000 µm. The samples were prepared by dispersing approximately 20 mg of powder in filtered water (β-cyclodextrin, Capsul® starch, and soybean meal) and ethyl alcohol (lactose, and maltodextrin A and B) (0.45-µm pore size membrane).

Product recovery

The product recovery rate (REC) (%) or process yield was determined with the mass balance, defined as the percentile ratio of the collected mass of the dried product to the solids mass fed into the equipment (Eq. 1) (Souza and Oliveira 2006). The solids content for the enzyme formulations added to the adjuvants was determined with a gravimetric method using a moisture analyzer balance (Sartorius-MA 35). The solids content was determined after the samples reached a constant mass and the result was expressed as percentage:

| 1 |

where Mc represents collected mass (g); xp represents product moisture; Ws represents feed flow rate (g/min); Cs represents total solids content (g/g); Ɵ represents process time (min).

Tannase activity

The spray-dried powders were suspended in 100 mmol L−1 sodium acetate buffer at pH 5.0 considering the same solids content calculated for the enzyme extract. The tannase activity was determined using 0.2% (w/v) methyl gallate as substrate in 100 mmol L−1 sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.0) according to the methanolic rhodanine method (Sharma et al. 2000). The reaction mixture containing 250 μL of substrate solution and 250 μL of enzyme sample was incubated at 30 °C for 5 min and stopped by the addition of 300 μL of methanolic rhodanine (0.667%; w/v) at 30 °C. After 5 min, 200 μL of 0.5 N potassium hydroxide was added and the mixture was maintained at 30 °C. Finally, the mixture was diluted with 4 mL of distilled water and incubated at 30 °C for 10 min. The absorbance was recorded at 520 nm using a spectrophotometer (UV Mini-1240, Shimadzu). One unit (U) of enzymatic activity was defined as the amount of enzyme necessary to produce 1 μmol of gallic acid per minute under the assay conditions.

Enzyme stability testing

The extracellular crude extract and the spray-dried tannase powders were characterized biochemically. The influence of temperature on tannase activity was evaluated by performing enzymatic reactions at temperatures ranging from 30 to 80 ºC. Thermal stability was determined by incubating the enzyme samples (crude extract and spray dried) in an aqueous solution at temperatures of 30 ºC, 40 ºC, 50 ºC, and 60 ºC for 120 min. After each time interval, aliquots were withdrawn, kept in an ice bath and assayed for the tannase activity. The influence of pH on the tannase activity was determined at pH values ranging from 3.0 to 7.0 using 100 mmol L−1 citric acid buffer (pH 3.0 and 4.0), 100 mmol L−1 sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.0 and 6.0), and 100 mmol L−1 Tris–HCL buffer (pH 7.0). The stability of the samples at different pH values was evaluated by maintaining the enzyme samples in 50 mmol L−1 sodium acetate buffer at pH 5.0 and 6.0 in an ice bath for 120 min. Aliquots were withdrawn at different time intervals, and residual enzyme activity was determined.

Influence of different compounds on tannase activity

The influence of different compounds (1 mmol L−1) and the organic solvents (1% v/v), such as methanol, acetonitrile, ethanol, acetone, isopropanol, and butanol, on tannase activity was analyzed, and the stability of the enzyme to these organic solvents was determined for 120 min. The compounds were selected according to the activation or inhibition of enzymatic activity reported previously for purified tannase of A. fumigatus CAS21 (Cavalcanti et al. 2018).

Treatment of sorghum with spray-dried tannase

Sorghum grains were purchased in the State of Paraíba- Brazil, washed several times with water, dried at 60 ºC, and shredded in a blender to obtain sorghum flour. In 25-mL Erlenmeyer flasks, 1 g of sorghum flour was added and 0.1 g of spray-dried tannase using lactose was sprinkled on the flours, followed by the addition of 1 mL distilled water, and the flasks were incubated for 120 h at 30 ºC. As a control, only sorghum flour was added to 1 mL distilled water. Control and treated samples were analyzed for the contents of tannins and polyphenolic compounds.

Quantification of tannins and phenolic compounds

The phenolic compounds were estimated using the methanol extraction procedure as described by Schons et al. (2012). Extraction was carried out at 200 rpm, at 25 °C for 2 h. After the extract was centrifuged at 1320xg for 15 min at 5 °C, the precipitate was discarded and the supernatant was used to quantify the phenolic compounds. Determination of the total phenolic compounds was performed using the Folin-Ciocalteu reagent, according to Rao et al. (2018). The tannin content was determined with the protein precipitation method (Hagerman and Butler 1978).

Treatment of leather effluent

The leather effluent samples were obtained from the tanning process of he-goat leather in the Arteza Cooperative, Paraíba, Brazil. Effluent samples, obtained through mechanical and manual processes, were treated with spray-dried tannase (0.5:1 m/v) using lactose for 2 h at 30 °C. In the manual process, leather is treated using angico burk (Anadenanthera colubrina Vell.) in a tank for 15 days, while in the mechanical process, the treatment is carried out using tannin powder either from angico or from cotton and soybean oils. After treatment, the samples were centrifuged at 2800xg for 15 min; the precipitate was discarded and the supernatant was used to quantify total phenolic compounds and tannins as described above.

Production of propyl gallate using spray-dried tannase

The spray-dried tannase using lactose was applied for the production of propyl gallate throughout the transesterification of the tannic acid in the presence of 1-propanol. The reaction mixture was composed of 250 μL of tannic acid (5 mmol L−1 in 100 mmol L−1 MES buffer pH 5.0), 250 μL of 1-propanol, and 0.04 g of spray-dried tannase. The reaction mixture was shaken slightly and maintained at 30 °C for 48 h, 72 h and 96 h. After the samples were centrifuged for 15 min at 2800xg, the supernatant was used to detect the presence of propyl gallate by Fourier Transform Infrared Spectrometry (FTIR) using Bruker Vertex 70 infrared spectrometer with attenuated total reflection (ATR). The software used was OPUS 7.5 with 4 cm−1 resolution, scan time of 64 scans and wavelength of 4000 cm−1 to 400 cm−1. Propyl gallate (Sigma®) was used as a standard. These analyses were carried out in the Multiuser Laboratory of Chemical Analyses of the Chemistry Institute of Araraquara (UNESP).

Storage stability

The stability of the spray-dried product in the presence of different adjuvants was investigated after storage at 4 ºC and 28 ºC for 1 year by determining the tannase activity as described previously.

Statistical analysis

Microsoft Office Excel 2007 (Microsoft), OriginPro 8 (OriginLab Corporation), and BioStat 5.3 programs were used for data analysis and graphical representations. Tukey’s test (p < 0.05) was applied to the spray-drying experiments. The assays were performed in triplicates and analyzed based on means ± standard error of the samples.

Results and discussion

The spray-drying technology is an important way to improve the enzyme stability aiming at different biotechnological applications. In this context, Table 1 shows the experimental results of process yield, tannase activity, and outlet drying temperature during spray drying of A. fumigatus CAS21 tannase in the presence of different adjuvants. The inlet temperature was set at 100 °C and the outlet spray-drying temperature varied between 55.8 and 59.3 °C depending on the adjuvant used. Temperature is the main parameter studied in drying processes since it affects the process yield, physicochemical properties of the final product, and the enzyme activity (Langford et al. 2018; Abdel-Madeeg et al. 2019). The outlet spray-drying temperature is generally considered as the maximum temperature to which the product is exposed and is directly influenced by the inlet temperature, drying rate, and the drying gas flow rate (Abdel-Madeeg et al. 2019). It was observed that the maximum outlet temperatures did not exceed 60 °C. The highest temperatures (59.3 ºC) were observed when soybean meal was used as an adjuvant; consequently, the product formed exhibited the lowest enzymatic activity (10.3 U/mL). However, Gupta et al. (2014) observed that the powder containing xylanase obtained at inlet temperatures of 140 °C and outlet ones at approximately 65.2 °C retained 99% of the residual activity after the spray-drying process. According to the authors, at lower temperatures, a viscous liquid was obtained, which increased product losses due to product adhering onto the walls of the drying chamber. If the product is retained with a high amount of moisture at low inlet temperatures, the yield of the product is significantly reduced (Schutyser et al. 2012; Ray et al. 2016). In contrast, higher outlet spray-drying temperatures would result in enzymatic denaturation (Torres et al. 2016; Libardi et al. 2020). Obón et al. (2020) observed greater retention of α-amylase activity at 120 ºC and 56 ºC as inlet and outlet temperatures, respectively. However, under these temperatures, lowest process yields were obtained. The same was observed for the spray drying of cellulase using maltodextrin as adjuvant, with maintenance of 40% of the activity at 120 ºC, although the highest yield observed at 180 ºC (Libardi et al. 2020).

Table 1.

Effects of the type of drying adjuvants on process yield, relative tannase activity and outlet drying temperature (Tgo)

| Adjuvants (10% w/v) | Tgo (ºC) | Ws (g/min) | REC (%) | Relative activity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soluble tannase | – | – | – | 100.0A ± 8.3 |

| β-Cyclodextrin | 58.0 ± 0 | 4.2 | 27.4 | 123.8B ± 2.6 |

| Capsul® starch | 58.3 ± 0.5 | 4.2 | 32.2 | 69.7C ± 4.1 |

| Soybean meal | 59.3 ± 1.0 | 4.2 | 29.8 | 47.0E ± 7.9 |

| Lactose | 55.6 ± 1.3 | 4.4 | 53.5 | 64.5CE ± 6.6 |

| Maltodextrin A | 57.3 ± 1.0 | 4.2 | 28.7 | 109.8AB ± 5.0 |

| Maltodextrin B | 57.3 ± 1.0 | 4.2 | 28.4 | 99.7A ± 8.6 |

100% activity corresponds to 23.0 ± 1.9 U mL−1. Tgo, outlet drying gas temperature; Ws, measured feed flow rate of enzyme composition. REC, product recovery. Values with the same letter in column do not differ by Tukey’s test at 5% probability (P ≤ 0.05)

It is shown in Table 1 that higher yields with spray drying were obtained with the formulations containing lactose (53.5%) and Capsul® starch (32.2%). Conversely, the formulation loaded with β-cyclodextrin exhibited the lowest yield (27.4%). Factors, such as dryer types, resident time, chamber size, and geometry, affect the performance of the drying process and, consequently, the quality of the final product and its physico-chemical properties (Costa et al. 2015; Keshani et al. 2015). The yield is also affected by the adherence of the product onto the walls of the drying chamber of a cyclone dryer or by elutriation (Estevinho et al. 2015; Abdel-Madeeg et al. 2019). When maltodextrin was used as adjuvant, a considerable amount of the powder was retained on the walls of the cyclone dryer. The samples from the collector flask (maltodextrin A) and the cyclone (maltodextrin B) were then collected separately. In general, the yields obtained were similar to those reported for spray drying of enzymes in bench-top spray dryers. Estevinho et al. (2015) reported yield of around 30% during the spray drying of β-galactosidase using chitosan as adjuvant, while Hamin Neto et al. (2014), during the spray drying of peptidases, obtained yields ranging from 35.8 to 63.0% depending on the operating conditions. According to Costa et al. (2015), the optimization of the drying conditions and an efficient dust collection system are important factors to be considered to increase the yield of products.

Interestingly, the product containing β-cyclodextrin exhibited an enzymatic activity of 28.5 U/mL, which was 23% higher than the initial activity from the crude extract (23.0 U/mL). Costa-Silva et al. (2014), during the spray drying of lipase from Cercospora kikuchii, also reported a higher activity of the powder containing β-cyclodextrin. The powder obtained with maltodextrin as adjuvant provided 100% preservation of the tannase activity after the spray-drying process. There are a number of reports highlighting the positive effects of maltodextrin during the drying of several enzymes, such as lysozyme (Amara et al. 2016), cellulase (Libardi et al. 2020), amylase, avicellase, CMCase, and FPase (Sarteshnizi et al. 2018). Maltodextrin is a carbohydrate additive used in spray-drying processes because of its bulking properties and low cost. Additionally, it has low emulsifying capacity and also a direct impact on powder solubility (Lee et al. 2018). The use of Capsul® starch and lactose promoted a lower retention of enzymatic activity (around 60%). Two mechanisms are reported to explain the performance of carbohydrates to avoid protein denaturation, namely by replacing water in interactions with the protein or by forming a glassy matrix, thus stabilizing the protein structure (Abdel-Mageed et al. 2018; Schutyser et al. 2012). According to Tonnis et al. (2014), hydrogen bonds between proteins and water molecules are replaced by hydrogen bonds between proteins and sugar hydroxyl groups.

The worst retention of the enzymatic activity (10.3 U/mL) was observed when soybean meal was used as an adjuvant, with a reduction of 53% compared to the values found in an aqueous solution of tannase. The efficiency of an adjuvant varies according to its physico-chemical properties and concentration used. In this study, all the adjuvants were employed at identical concentrations of 10% (w/v). According to Cabral et al. (2017), an adjuvant does not effectively protect enzymes from thermal stress during the drying process at low concentrations. However, high concentrations could also affect the secondary structure of the enzyme, leading to reduced enzymatic activity. Interestingly, the use of soybean meal at concentrations of 2, 5, and 10% (w/v) allowed higher retention of enzymatic activities during the spray-drying process of phytase from Rhizopus microsporus var. microsporus (Sato et al. 2014). The main reasons for the reduction of enzymatic activity observed for the spray-dried tannase in the presence of soybean meal may include reduction in the enzyme mobility and difficulty in the interaction between the substrate and the active site of the enzyme due to enzyme-adjuvant interaction (Amara et al. 2016).

Table 2 presents the residual moisture content, water activity (Aw), and particle size of spray-dried tannase powders. The moisture content of the product ranged from 5.6 to 11.5% according to the adjuvant used. A higher value was observed for the product with β-cyclodextrin rather than with other adjuvants. Low moisture values are recommended because they may prevent the occurrence of agglomeration in the dried powders (Silva et al. 2013) during storage and are essential for maintaining product stability. The water activities ranged from 0.249 to 0.448, which are the desired values to ensure the physicochemical and microbiological quality of the product. According to Syamaladevi et al. (2016), water activity refers to the estimation of thermodynamically available water for chemical and biological reactions. The lower the water activity of the dried product, the better the stability and storage potential, as it prevents the risk of chemical and biological spoilage (Gharsallaoui et al. 2007). The values of water activity and moisture content reported in these studies were similar to those reported for spray-dried products containing lipase (Costa-Silva et al. 2014), phytase (Sato et al. 2014), trypsin (Zhang et al. 2018), and cellulase (Libardi et al. 2020).

Table 2.

Physical–chemical characteristics of spray-dried powders containing tannase in the presence of different adjuvants

| Adjuvants (10% w/v) | Xp (%) | Aw (−) | Particle size (µm) | SPAN | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d10 | d50 | d90 | ||||

| β-Cyclodextrin | 11.5 ± 0.4 | 0.28 ± 0 | 4.01 | 32.66 | 111.1 | 3.28 |

| Capsul® starch | 7.0 ± 0.1 | 0.25 ± 0 | 4.66 | 11.04 | 17.70 | 1.18 |

| Soybean meal | 5.7 ± 0.1 | 0.36 ± 0 | 2.69 | 11.75 | 34.28 | 2.69 |

| Lactose | 5.6 ± 0 | 0.33 ± 0 | 1.98 | 13.66 | 43.97 | 3.07 |

| Maltodextrin A | 6.1 ± 0.1 | 0.32 ± 0 | 2.47 | 12.60 | 26.43 | 1.90 |

| Maltodextrin B | 7.3 ± 0.3 | 0.45 ± 0 | 3.09 | 10.60 | 38.37 | 3.33 |

Xp, product moisture content; Aw, water activity; dp, particle diameter

The properties of the powder can be controlled by the process parameters. The sizes of the particles are influenced by the adjuvant, atomizing pressure, size, and the position of the spray nozzle (Schutyser et al. 2012; Mahdavi et al. 2014). From the analyses of size distributions, the particle sizes at the 10, 50, and 90 percentiles, as well as the SPAN, given by the ratio ((d90−d10)/d50), were determined (Table 2). The results of particle sizes of all the formulations tested in this study were within the reported range for spray-dried enzymes (Costa-Silva et al. 2014; Sato et al. 2014). It is evident that the type of the drying carriers and their concentrations affect particle sizes of the spray-dried product, as also observed by Abdel-Madeeg et al. (2019) for the spray drying of α-amylase. Moreover, it was noted that the SPAN value of formulation with β-cyclodextrin, lactose, and maltodextrin B were higher than the other formulations, indicating a higher polydispersity.

Effect of temperature and pH on the activity of the spray-dried tannase

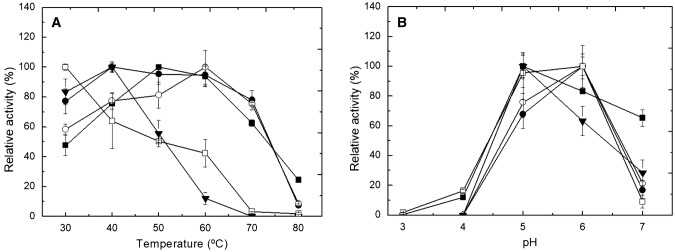

The spray-dried products in the presence of different adjuvants that bore tannase activity above 50% were biochemically characterized. The soluble tannase produced by A. fumigatus CAS21 presented an optimum activity at temperatures ranging from 50 to 60 °C, whereas in spray-dried powders, the temperature varied according to the adjuvant used in the drying process (Fig. 1a). The best tannase activity of the powder obtained in the presence of β-cyclodextrin as an adjuvant was achieved in the range of 40–60 °C and for the Capsul® starch powder at 60 °C. The spray-dried enzyme with maltodextrin and lactose as adjuvants presented the lowest optimum temperatures, 30 ºC and 40 ºC, respectively. For the powders obtained with these adjuvants, high temperatures decreased the tannase activity, with enzyme denaturation at 80 ºC.

Fig. 1.

Influence of temperature (a) and pH (b) on the activity of the soluble A. fumigatus CAS21 tannase (■) and on spray-dried powders containing tannase in presence of β-cyclodextrin (●), Capsul® starch (○), lactose (▼), and maltodextrin (□) as stabilizing agents

Using lactose as an adjuvant, soluble tannase and spray-dried powder of tannase demonstrated enzyme activities at similar optimum pH values, with maximum activity at around pH 5.0, which in turn decreased at higher pH values. For the spray-dried enzyme in the presence of β-cyclodextrin, Capsul® starch, and maltodextrin, the highest activity was found at pH 6.0 (Fig. 1b). However, the enzymatic activities were drastically reduced at pH 7.0 for all the spray-dried powders analyzed. Microbial tannases are characterized by having an optimum temperature of activity between 30 and 60 ºC in the soluble forms, and they are active at optimum pH range of around 5.0–6.0 (Yao et al. 2014; Kumar et al. 2018). However, the characteristics observed for the spray-dried tannase in the presence of Capsul® starch and β-cyclodextrin differed from those described for the pure enzyme that possessed an optimum enzymatic activity at temperatures from 30 to 40 ºC and at pH 5.0 (Cavalcanti et al. 2018).

Considering the thermal stability of the soluble and spray-dried tannase in the presence of different adjuvants, it can be observed that the enzyme remained stable at 30 °C for over 120 min for all the conditions analyzed (Fig. 2). At the same temperature, the purified A. fumigatus CAS21 tannase was stable only for 60 min (Cavalcanti et al. 2018). Reduction of 30% in the activity was observed when the soluble tannase was incubated at 40 ºC, 50 ºC, and 60 ºC for 120 min. In contrast, the spray-dried enzyme in the presence of β-cyclodextrin was stable at 40 ºC for 120 min, and maintained 80% of its initial activity at 50 and 60 ºC. The spray-dried tannase using Capsul® starch and maltodextrin as adjuvants was fully stable at 40, 50, and 60 °C for over 120 min, while the tannase stability in the spray-dried powder using lactose was reduced at these temperatures. Figure 3 shows the profiles of the enzymatic stability at pH 5.0 and 6.0 for 120 min. The soluble and spray-dried tannases were stable at both pH values analyzed, showing similar activities—except for the one containing Capsul® starch, which presented a 20% reduction in the enzymatic activity at pH 6.0 with 120 min of incubation.

Fig. 2.

Thermal stability at 30 °C (a), 40 °C (b), 50 °C (c), and 60 °C (d) for the soluble A. fumigatus CAS21 tannase (■) and for the spray-dried powders containing tannase in the presence of β-cyclodextrin (●), Capsul® starch (○), lactose (▼), and maltodextrin (□) as stabilizing agents

Fig. 3.

Stability at pH 5.0 (a) and pH 6.0 (b) of the soluble tannase (■) from A. fumigatus CAS21 and for spray-dried powders containing tannase in the presence of β-cyclodextrin (●), Capsul® starch (○), lactose (▼), and maltodextrin (□) as adjuvants

Tannase activity was also analyzed for each dried powder obtained after 1 year of storage at 4 °C and 28 ºC (Table 3). In general, all the adjuvants used in the drying process were efficacious as stabilizing agents, maintaining the enzymatic activity for long storage times at 4 ºC and 28 ºC. However, after 1 year of storage at 28 ºC, reduction in activity (-37.5%) was observed for the product containing soybean meal. Drying is an efficient alternative to minimize the negative effects for molecules in aqueous solutions, such as long-term storage instability. Water molecules facilitate chemical modifications in the structure of proteins, thereby leading to a loss of enzymatic activity (Libardi et al. 2020). Therefore, the adjuvants act to preserve the structures of dried products during the drying and storage processes (Ray et al. 2016). Hamin Neto et al. (2017) reported that using maltodextrin as adjuvant for spray-drying protease and collagenase preserved their activities for 180 days when stored at 30 ºC. Spray-dried α-amylase in the presence of sucrose as adjuvant retained 72% of initial activity after storage for 2 months (Abdel-Madeeg et al. 2019). Costa-Silva et al. (2014) reported maintenance of lipase activity of the spray-dried products in the presence of lactose, maltodextrin, and β-cyclodextrin above 70% after 6 months of storage at 5 ºC. Cellulase activity after spray drying using maltodextrin as adjuvant was maintained at about 91% after 2 months of storage (Libardi et al. 2020).

Table 3.

Storage stability of the A. fumigatus CAS21 spray-dried tannase for 1 year at 4 ºC and 28 ºC

| Adjuvants (10% w/v) | Relative tannase activity (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| 4 ºC | 28 ºC | |

| β-Cyclodextrina | 146.3 ± 14.8 | 101.8 ± 11.6 |

| Capsul® Starchb | 119.0 ± 14.3 | 111.9 ± 10.7 |

| Soybean mealc | 121.8 ± 12.2 | 62.5 ± 0.3 |

| Lactosed | 121.9 ± 0.2 | 122.2 ± 0.7 |

| Maltodextrine | 122.1 ± 13.1 | 111.0 ± 2.1 |

a100% activity corresponds to 28.5 ± 0.6 U mL−1

b100% activity corresponds to 16.1 ± 0.9 U mL−1

c100% activity corresponds to 10.8 ± 1.8 U mL−1

d100% activity corresponds to 14.8 ± 1.5 U mL−1

e100% activity corresponds to 25.3 ± 1.1 U mL−1

In general, spray-dried enzymes showed improved biochemical characteristics when compared to those of their soluble forms, as reported for the phytase (Sato et al. 2014) and trypsin (Zhang et al. 2018). According to Sato et al. (2014), interaction with adjuvants replaces the protein-water interactions and promotes the formation of a vitreous matrix, showing an increase in the stability of the enzyme against changes in temperature and pH.

Influence of chemicals on enzymatic activity

The influence of different chemical compounds on the enzymatic activity of the dried products is presented in Table 4. The enzymatic activities were inhibited when iron ions were added. The compounds FeCl3 and Fe2(SO4)3 have already been reported in literature to act as inhibitors of the tannase activity of purified enzymes from A. fumigatus CAS21 (Cavalcanti et al. 2018), A. carbonarius (Valera et al. 2015), and A. oryzae (Abdel-Nabey et al. 2016). Urea also had a negative effect on enzymatic activity of aqueous solutions and powders. Urea is shown to alter the polar groups and weaken the hydrophobic interactions of proteins (Wu et al. 2010). Generally, enzymatic activity is inhibited in the presence of heavy metals, such as silver, but the addition of AgNO3 did not alter the enzymatic activities for the spray-dried products. Interestingly, AgNO3 was able to activate (> 20%) spray-dried tannase containing the adjuvants, lactose, and maltodextrin. Similar results were obtained for the purified tannases from A. fumigatus CAS21 (Cavalcanti et al. 2018) and A. carbonarius (Valera et al. 2015).

Table 4.

Influence of different compounds on the enzymatic activity of the aqueous and spray-dried tannase of A. fumigatus CAS21

| Compounds | Soluble tannase | Β-Cyclodextrin | Capsul® starch | Lactose | Maltodextrin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 100a ± 2.0 | 100b ± 6.2 | 100c ± 13.0 | 100d ± 8.8 | 100e ± 14.4 |

| Salts | |||||

| AgNO3 | 77.1 ± 9.1 | 108.3 ± 4.4 | 82.4 ± 8.5 | 127.7 ± 5.0 | 123.7 ± 8.9 |

| FeCl3 | 46.1 ± 8.5 | 58.6 ± 8.37 | 74.4 ± 6.3 | 3.9 ± 2.7 | 56.2 ± 16.1 |

| FeSO4 | 51.2 ± 3.0 | 52.6 ± 0.79 | 23.5 ± 0.1 | 48.8 ± 13.1 | 39.9 ± 4.1 |

| KH2PO4 | 72.3 ± 8.9 | 93.8 ± 12.5 | 52.7 ± 9.7 | 78.8 ± 13.1 | 120.4 ± 14.5 |

| MnSO4 | 104.1 ± 12.3 | 95.8 ± 10.7 | 44.2 ± 7.8 | 75.3 ± 3.8 | 94.2 ± 6.3 |

| Urea | 73.5 ± 10.3 | 47.2 ± 2.7 | 89.8 ± 8.0 | 46.7 ± 1.5 | 60.1 ± 1.8 |

| Solvents | |||||

| Acetone | 107.7 ± 13.3 | 86.5 ± 13.4 | 69.2 ± 2.6 | 100.6 ± 4.6 | 58.0 ± 8.4 |

| Acetonitrile | 153.1 ± 13.0 | 105.1 ± 11.5 | 73.1 ± 4.2 | 134.7 ± 11.5 | 81.2 ± 16.6 |

| Butanol | 96.7 ± 13.4 | 75.1 ± 6.2 | 64.0 ± 9.9 | 145.3 ± 6.3 | 51.0 ± 13.0 |

| Ethanol | 76.8 ± 13.3 | 60.4 ± 8.4 | 90.7 ± 5.6 | 98.5 ± 4.4 | 83.4 ± 12.2 |

| Isopropanol | 107.7 ± 7.1 | 47.2 ± 11.2 | 99.8 ± 13.0 | 112.9 ± 8.7 | 70.3 ± 6.3 |

| Methanol | 89.2 ± 4.9 | 128.8 ± 14.9 | 104.5 ± 6.8 | 91.4 ± 6.6 | 42.9 ± 7.8 |

a100% activity corresponds to 28.1 ± 1.0 U mL−1

b100% activity corresponds to 14.6 ± 0.9 U mL−1

c100% activity corresponds to 23.4 ± 3.1 U mL−1

d100% activity corresponds to 19.1 ± 1.7 U mL−1

e100% activity corresponds to 18.7 ± 1.3 U mL−1

For the solvents analyzed, the soluble tannase activity was increased (+ 53%) in the presence of 1% (v/v) acetonitrile and remained without significant alterations in the presence of acetone, butanol, and isopropanol. However, addition of ethanol and methanol reduced the tannase activity (-23.2% and -10.9%, respectively). Regarding the dried powders obtained using different adjuvants, the enzymatic activity was reduced for all the solvents tested when maltodextrin was used, especially in the presence of butanol, with reduction of 50% in the enzyme activity. The use of β-cyclodextrin allowed the maintenance of the tannase activity in the presence of acetonitrile and increased its activity in the presence of methanol (+ 28%). When Capsul® starch was used as an adjuvant, the tannase activity of the spray-dried powder was maintained without significant alterations in the presence of isopropanol and methanol, surpassing the activity obtained for the soluble enzyme. The tannase activity of the powder dried with lactose as an adjuvant was also increased in the presence of isopropanol (+ 12%) and butanol (+ 45%), as compared to the control, and was maintained without significant alterations in the presence of ethanol and methanol. Different activities were observed for spray-dried tannase depending on the solvents and adjuvants used. The enzyme-adjuvant interaction can positively or negatively influence tannase activity in the presence of solvents. In general, solvents act either by inhibiting the enzymatic activity through the breakdown of hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions, essential for the native conformation of the enzyme, or by removing the water around the enzyme molecule (Kumar et al. 2016). According to Yu et al. (2004) and Gonçalves et al. (2011), despite the inhibitory effects, some solvents can improve solubility of the substrate or promote modifications in the native conformation by regulating the reaction medium.

Lactose as an adjuvant maintains tannase activity in all the solvents added in the reaction medium with a relative activity higher than 90%. Therefore, the stability of dried tannase in lactose was analyzed in different solvents (50% v/v) for 120 min (Fig. 4). The enzyme remained stable for 60 min in methanol (log P = -0.76), but the activity was reduced by 43% when treated for longer times. Incubation in acetone drastically reduced the activity by 94% (log P = − 0.23) after 120 min. The enzyme was completely stable in the presence of butanol (log P = 0.8), while in the solvents, ethanol (log P = − 0.24) and isopropanol (log P = 0.05), the enzymatic activity was maintained at around 80%. It is reported that increasing polarity of organic solvents promotes the removal of water of hydration present on the surface of the enzyme. However, in the present work, there was no correlation observed between the log P function and the enzymatic activity. Other properties also influence the catalytic activity of enzymes in the presence of solvents, such as the overall size of the solvent molecules, high solubility of the substrate, and low solubility of the product (Kumar et al. 2016).

Fig. 4.

Stability of the enzymatic activity of spray-dried tannase from A. fumigatus CAS21 in the presence of lactose as adjuvant to the solvents − acetone (■), acetonitrile (●), butanol (▲), ethanol (▼), isopropanol (□), and methanol (○)

It is speculated that lactose may have acted as a protective agent for the enzyme molecules by forming a layer that envelops the enzyme, in turn preventing direct contact with the solvent. Possibly, this mechanism is similar to the one involved in providing greater stability of microencapsulated enzymes (Yu et al. 2004). It is also reported that dried enzymes in the presence of sugars are more stable in organic solvents due to the strengthening of hydrophobic interactions between non-polar amino acid residues, thus presenting more rigid protein structures (Stepankova et al. 2013). According to Kumar et al. (2016), most enzymes are less active and stable in the presence of organic solvents, restricting their industrial application. Thus, the stability of some spray-dried products containing tannase in the presence of solvents suggests their suitability for industrial applications, such as esterification and transesterification reactions, for example, to synthesize propyl gallate from gallic acid in a non-aqueous medium (Cavalcanti et al. 2018).

Application of the spray-dried product

The spray-dried tannase using lactose as an adjuvant was chosen to be applied in the sorghum and leather effluent treatment due to a higher recovery of the product and maintenance of the enzymatic activity after the drying process. According to Table 5, the content of total tannins and phenolic compounds present in the sorghum flour were reduced by 52.6% and 12.5%, respectively, after a 120-h treatment with spray-dried tannase using lactose as adjuvant. Vegetables and agro-industrial by-products, such as sorghum, barley, and corn straw are commonly used in animal feed for chickens and ruminants. Also, the use of tannases can improve the nutritional value of animal feed by removing tannins (Kumar et al. 2018), which can influence nutrient assimilation because of their property of precipitating proteins and forming cross-links with some carbohydrates (Kumar et al. 2018). Raghuwanshi et al. (2014) verified a 91.1% reduction in tannin content of wheat straw after tannase treatment. Abdulla et al. (2016) concluded that field beans treated with tannase improved nutrient utilization, metabolizable dietary energy and improved feed efficiency of broiler chickens.

Table 5.

Application of spray-dried tannase with lactose in the degradation of tannins present in industrial effluents and sorghum

| Samples | Tannin content (%) | Total phenolic compounds (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Without treatment | 100 ± 8.0 | 100 ± 1.1 |

| Sorghum + enzyme | 47.7 ± 5.4 | 87.5 ± 0.4 |

| Leather effluenta + enzyme | 45.4 ± 8.6 | 82.0 ± 8.7 |

| Leather effluentb + enzyme | 32.3 ± 8.3 | 98.4 ± 0.5 |

aEffluent obtained from leather treatment using mechanical

bEffluent obtained from the manual leather treatment

In Table 5, it is shown that the application of spray-dried tannase with lactose in the treatment of mechanical and manual effluents of the tannery industry reduced the tannins content by 54.5% and 67.7%, respectively. Balakrishnan et al. (2018) reported that to increase the efficiency of biological treatment of wastewater produced by leather industry, tannins must be degraded before biological treatment for the decomposition of other constituents is carried out. One negative consequence of the pollution of the aquatic environments by tannery effluents is the blockage of sunlight, impairing the photosynthesis and, consequently, reducing the dissolved oxygen levels in the natural waters (Dhiman et al. 2018). The use of the spray-dried tannase was also able to reduce the content of total phenolic compounds especially in the effluent obtained from the mechanical process of the leather treatment. Therefore, tannase may be useful in reducing environmental pollution caused by tannins, thus improving the efficiency of the other biological methods of reducing pollution already in use.

Some microbial tannases are also able to catalyze transesterification reaction producing propyl gallate as reported for the enzyme from A. fumigatus CAS 21 (Cavalcanti et al. 2018). The FTIR spectra for the propyl gallate produced throughout the transesterification of the tannic acid by the action of the spray-dried tannase with lactose are shown in Fig. 5. The FTIR spectra showed similar bands observed for both the commercial propyl gallate and the one that was produced in-house. The bands between 2960 and 2850 cm−1 regions indicate the presence of CO2 group, while bands between 1750 and 1500 cm−1 correspond to carbonyl ester and aromatic − both characteristics of the propyl gallate molecule (Bouaziz et al. 2010; Beena et al. 2011). Similar spectra were obtained for the production of propyl gallate using A. awamori BTMFW021 tannase (Beena et al. 2011).

Fig. 5.

FTIR spectra for the commercially available propyl gallate (a) and that produced in-house (b–d) using spray-dried powder containing A. fumigatus CAS21 tannase in the presence of lactose as adjuvant at 48 h (b), 72 h (c), and 96 h (d) of transesterification reaction using tannic acid as a substrate in the presence of 1-propanol

Conclusion

The enzymatic activity of tannase from A. fumigatus CAS21 was successfully preserved during spray drying. Moreover, the values of water activity, moisture content, and particle size agreed with the expected values for dried products. The spray-dried tannase had improved thermostability and was resistant to different solvents. In addition, the dried products maintained the tannase activity for a long storage period. All these characteristics indicate the biotechnological potential of the spray-dried tannase, which can be applied in the food and pharmaceutical industries, animal feed, and propyl gallate synthesis.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support from Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo-FAPESP (Process no 2016/11311-5) and Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia, Inovações e Comunicações (CNPq) (142389/2017-0). They also thank Maurício de Oliveira for the technical assistance and Laboratório de P&D em Processos Farmacêuticos e Biotecnológicos from Universidade de São Paulo (LAPROFAR/USP) for development of the drying tests and Carlos Ambrosio from ARTEZA, who provided the effluent samples. The manuscript is a part of the doctoral thesis of R.M.V.F., who is financed by Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia, Inovações e Comunicações (CNPq).

Authors’ contributions

RMFC performed the laboratory work, studied, and prepared the MS; MLLM supported the spray-drying assays; WPO planned and supervised the spray-drying assays and prepared the MS, and LHSG planned and supervised the whole work, and prepared the manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Abdel-Madeeg HM, Fouad SH, Teaima MH, Abdel-Aty AM, Fahmy AS, Shaker DS, Mohamed SA. Optimization of nano spray drying parameters for production of α-amylase nanopowder for biotherapeutic applications using factorial design. Dry. Technol. 2019 doi: 10.1080/07373937.2019.1565576. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Nabey MA, El-Tanash AB, Sherief ADA. Structural characterization, catalytic, kinetic and thermodynamic properties of Aspergillus oryzae tannase. Int J Biol Macromol. 2016;92:803–811. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.06.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdulla J, Rose SP, Mackenzie AM, Mirza W, Pirgozliev V. Exogenous tannase improves feeding value of a diet containing field beans (Vicia faba) when fed to broilers. Br Poult Sci. 2016;57:246–250. doi: 10.1080/00071668.2016.1143551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar-Zárate P, Cruz-Hernández MA, Montãnezl JC, Belmares-Cerda RE, Aguilar CN. Bacterial tannases: production, properties and applications. Rev Mex Ingeniería Quím. 2014;13:63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Amara CB, Eghbal N, Degraeve P, Gharsallaoui A. Using complex coacervation for lysozyme encapsulation by spray-drying. J Food Eng. 2016;183:50–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2016.03.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishnan A, Kameswari KSB, Kalyanaraman C. Assessment of aerobic biodegradability for vegetable tanning process wastewater generated from leather industry. Water Qual Manag. 2018;79:151–160. doi: 10.1007/978-981-10-5795-3_14. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beena PS, Basheer SM, Bhat SG, Bahkali AH, Chandrasekaran M. Propyl gallate synthesis using acidophilic tannase and simultaneous production of tannase and gallic acid by marine Aspergillus awamori BTMFW032. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2011;164:612–628. doi: 10.1007/s12010-011-9162-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouaziz A, Horchani H, Salem NB, Chaari A, Chaabouni M, Gargouri Y, Sayari A. Enzymatic propyl gallate synthesis in solvent-free system: optimization by response surface methodology. J Mol Cat B: Enzym. 2010;67:242–250. doi: 10.1016/j.molcatb.2010.08.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cabral TPF, Bellini NC, Assis KR, Teixeira CCC, Lanchote AD, Cabral H, Freitas LAP. Microencapsulate Aspergillus niger peptidases from agroindustrial waste wheat bran: spray process evaluation and stability. J Microencapsul. 2017;34:560–570. doi: 10.1080/02652048.2017.1367851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalcanti RMF, Jorge JA, Guimarães LHS. Characterization of Aspergillus fumigatus CAS-21 tannase with potential for propyl gallate synthesis and treatment of tannery effluent from leather industry. Biotech. 2018;8:270. doi: 10.1007/s13205-018-1294-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalcanti RMF, Ornela PHO, Jorge JA, Guimarães LHS. Screening, selection and optimization of the culture conditions for tannase production by endophytic fungi isolated from Caatinga. J Appl Biol Biotechnol. 2017;5:1–9. doi: 10.7324/JABB.2017.50101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chávez-González ML, Buenrostro-Figueroa J, Rodríguez Durán LV, Zárate PA, Rodríguez R, Rodríguez-Jasso RM, Ruiz HA, Aguilar CN. Tannases. In: Pandey A, Negi S, Soccol C, editors. Current developments in biotechnology and bioengineering: production, isolation and purification of industrial products. New York: Elsevier; 2016. pp. 471–489. [Google Scholar]

- Costa SS, Machado BAS, Martin AR, Bagnara F, Ragadalli SA, Alves ARC. Drying by spray drying in the food industry: micro-encapsulation, process parameters and main carriers used. Afr J Food Sci. 2015;9:462–470. doi: 10.5897/AJFS2015.1279. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Costa-Silva TA, Souza CRF, Oliveira WP, Said S. Characterization and spray drying of lipase produced by the endophytic fungus Cercospora kikuchii. Braz J Chem Eng. 2014;31:849–858. doi: 10.1590/0104-6632.20140314s00002880. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dhiman S, Mukherjee G, Singh AK. Recent trends and advancements in microbial tannase-catalyzed biotransformation of tannins: a review. Int Microbiol. 2018;21:175–195. doi: 10.1007/s10123-018-0027-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estevinho BN, Ramos I, Rocha F. Effect of the pH in the formation of β-galactosidase microparticles produced by a spray-drying process. Int J Biol Macromol. 2015;78:238–242. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gharsallaoui A, Roudaut G, Chambin O, Voilley A, Saurel R. Applications of spray-drying in microencapsulation of food ingredients: an overview. Food Res Int. 2007;40:1107–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2007.07.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves HB, Riul AJ, Terenzi HF, Jorge JA, Guimarães LHS. Extracellular tannase from Emericella nidulans showing hypertolerance to temperature and organic solvents. J Mol Catal B: Enzym. 2011;71:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.molcatb.2011.03.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Govindarajan RK, Revathi S, Rameshkumar N, Krishnan M, Kayalvizhi N. Microbial tannase: current perspectives and biotechnological advances. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.bcab.2016.03.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta G, Sahai V, Mishra S, Gupta RK. Spray-drying of xylanase from thermophilic fungus Melanocarpus albomyces—effect of carriers and binders on enzyme stability. Indian J Chem Technol. 2014;21:89–95. doi: 10.15421/081321. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hagerman AE, Butler LG. Protein precipitation method for the quantitative determination of tannins. J Agric Food Chem. 1978;26:809–812. doi: 10.1021/jf60218a027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamin Neto YAA, Coitinho LB, Freitas LAP, Cabral H. Multivariate analysis of the stability of spray-dried Eupenicillium javanicum peptidases. Dry Technol. 2014;32:614–621. doi: 10.1080/07373937.2013.853079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamin Neto YAA, Coitinho LB, Freitas LAP, Cabral H. Box-Behnken analysis and storage of spray-dried collagenolytic proteases from Myceliophthora thermophila submerged bioprocess. Prep Biochem Biotechnol. 2017;47:473–480. doi: 10.1080/10826068.2017.1292289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshani S, Daud WRW, Nourouzi MM, Namvar F, Ghasemi M. Spray drying: an overview on wall deposition, process and modeling. J Food Eng. 2015;146:152–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2014.09.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Dhar K, Kanwar SS, Arora PK. Lipase catalysis in organic solvents: advantages and applications. Biol Proced Online. 2016 doi: 10.1186/s12575-016-0033-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar SS, Sreekumar R, Sabu A. Tannase and its applications in food processing. In: Parameswaran B, Varjani S, Raveendran S, editors. Green bio-processes energy, environment, and sustainability. Singapore: Springer; 2018. pp. 357–381. [Google Scholar]

- Langford A, Bhatnagar B, Walters R, Tchessalov S, Ohtake S. Drying technologies for biopharmaceutical applications: recent developments and future direction. Dry Technol. 2018;36:677–684. doi: 10.1080/07373937.2017.1355318. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JKM, Taip FS, Abdullah Z. Effectiveness of additives in spray drying performance: a review. Food Res. 2018;2:486–499. doi: 10.26656/fr.2017.2(6).134. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Libardi N, Soccol CR, Tanobe VOA, Vandenberghe LPS. Definition of liquid and powder cellulase formulations using domestic wastewater in bubble column reactor. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2020;190:113–128. doi: 10.1007/s12010-019-03075-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipiäinen T, Räikkönen H, Kolu AM, Peltoniemi M, Juppo A. Comparison of melibiose and trehalose as stabilising excipients for spray-dried β-galactosidase formulations. Int J Pharm. 2018;543:21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2018.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahdavi SA, Jafari SM, Ghorbani M, Assadpoor E. Spray-drying microencapsulation of anthocyanins by natural biopolymers: a review. Dry Technol. 2014;32:509–518. doi: 10.1080/07373937.2013.839562. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Obón JM, Luna-Abad JP, BermejoFernández-López BB. Thermographic studies of cocurrent and mixed flow spray drying of heat sensitive bioactive compounds. J Food Eng. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2019.109745. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raghuwanshi S, Misra S, Saxena RK. Treatment of wheat straw using tannase and white-rot fungus to improve feed utilization by ruminants. J Anim Sci Biotechnol. 2014;5:1–8. doi: 10.1186/2049-1891-5-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao S, Santhakumar AB, Chinkwo KA, Wu G, Johnson SK, Blanchard CL. Characterization of phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity in sorghum grains. J Cereal Sci. 2018;9:103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.jcs.2018.07.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ray S, Raychaudhuri U, Chakraborty R. An overview of encapsulation of active compounds used in food products by drying technology. Food Biosci. 2016;13:76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.fbio.2015.12.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sarteshnizi FR, Benemar HA, Seifdavati J, Greiner R, Salem AZM, Behroozyar HK. Production of an environmentally friendly enzymatic feed additive for agriculture animals by spray drying abattoir’s rumen fluid in the presence of different hydrocolloids. J Clean Prod. 2018;197:870–874. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.06.220. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sato VS, Jorge JA, Oliveira WP, Souza CR, Guimarães LHS. Phytase production by Rhizopus microsporus var. microsporus biofilm: characterization of enzymatic activity after spray drying in presence of carbohydrates and nonconventional adjuvants. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;24:177–187. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1308.08087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schons PF, Battestin V, Macedo GA. Fermentation and enzyme treatments for sorghum. Braz J Microbiol. 2012;43:89–97. doi: 10.1590/S1517-83822012000100010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schutyser MAI, Perdana JA, Boom RM. Single droplet drying for optimal spray drying of enzymes and probiotics. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2012;27:73–82. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2012.05.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S, Bhat TK, Dawra RK. A spectrophotometric method for assay of tannase using rhodanine. Anal Biochem. 2000;279:85–89. doi: 10.1006/abio.1999.4405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva FC, Fonseca CR, Alencar SM, Thomazini M, Balieiro JCC, Pittia P, Favaro-Trindade CS. Assessment of production efficiency, physicochemical properties and storage stability of spray-dried propolis, a natural food additive, using gum Arabic and OSA starch-based carrier systems. Food Bioprod Process. 2013;91:28–36. doi: 10.1016/j.fbp.2012.08.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Souza CRF, Oliveira WP. Powder properties and system behavior during spray drying of Bauhinia forficata link extract. Dry Technol. 2006;24:735–749. doi: 10.1080/07373930600685905. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stepankova V, Bidmanova S, Koudelakova T, Prokop Z, Chaloupkova R, Damborsky J. Strategies for stabilization of enzymes in organic solvents. ACS Catal. 2013;3:2823–2836. doi: 10.1021/cs400684x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Syamaladevi RM, Tang J, Villa-Rojas R, Sablani S, Carter B, Campbell G. Influence of water activity on thermal resistance of microorganisms in low-moisture foods: a review. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2016;15:353–370. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonnis WF, Amorij JP, Vreeman MA, Frijlink HW, Kersten GF, Hinrichs WLJ. Improved storage stability and immunogenicity of hepatitis B vaccine after spray-freeze drying in presence of sugars. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2014;55:36–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres A, Ferrándiz M, Capablanca L, Franco E, Mira E, Moldovan S. Microencapsulation of lipase and savinase enzymes by spray drying using arabic gum as wall material. J Encapsul Adsorpt Sci. 2016;6:161–217. doi: 10.4236/jeas.2016.64012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Valera L, Jorge JA, Guimarães LHS. Characterization of a multi-tolerant tannin acyl hydrolase II from Aspergillus carbonarius produced under solid-state fermentation. Electr J Biotechnol. 2015;18:464–470. doi: 10.1016/j.ejbt.2015.09.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu XQ, Wang J, Lü ZR, Tang HM, Park D, Oh SH, Bhak J, Shi L, Park YD, Zou F. Alpha-glucosidase folding during urea denaturation: enzyme kinetics and computational prediction. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2010;160:1341–1355. doi: 10.1007/s12010-009-8636-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao J, Guo GS, Ren GH, Liu YH. Production, characterization and applications of tannase. J Mol Catal B. 2014;101:137–147. doi: 10.1016/j.molcatb.2013.11.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X, Li Y, Wu D. Enzymatic synthesis of gallic acid esters using microencapsulated tannase: effect of organic solvents and enzyme specificity. J Mol Catal B. 2004;30:69–73. doi: 10.1016/j.molcatb.2004.03.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Lei H, Gao X, Xiong X, Wu WD, Wu Z, Chen XD. Fabrication of uniform enzyme-immobilized carbohydrate microparticles with high enzymatic activity and stability via spray drying and spray freeze drying. Powder Technol. 2018;30:40–49. doi: 10.1016/j.powtec.2018.02.02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]