Key Points

Plus-stranded RNA viruses induce large membrane structures that might support the replication of their genomes. Similarly, cytoplasmic replication of poxviruses (large DNA viruses) occurs in associated membranes. These membranes originate from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) or endosomes.

Membrane vesicles that support viral replication are induced by a number of RNA viruses. Similarly, the poxvirus replication site is surrounded by a double-membraned cisterna that is derived from the ER.

Analogies to autophagy have been proposed since the finding that autophagy cellular processes involve the formation of double-membrane vesicles. However, molecular evidence to support this hypothesis is lacking.

Membrane association of the viral replication complex is mediated by the presence of one or more viral proteins that contain sequences which associate with, or integrate into, membranes.

Replication-competent membranes might contain viral or cellular proteins that contain amphipathic helices, which could mediate the membrane bending that is required to form spherical vesicles.

Whereas poxvirus DNA replication occurs inside the ER-enclosed site, for most RNA viruses the topology of replication is not clear. Preliminary results for some RNA viruses suggest that their replication could also occur inside double-membrane vesicles.

We speculate that cytoplasmic replication might occur inside sites that are 'enwrapped' by an ER-derived cisterna, and that these cisternae are open to the cytoplasm. Thus, RNA and DNA viruses could use a common mechanism for replication that involves membrane wrapping by cellular cisternal membranes.

We propose that three-dimensional analyses using high-resolution electron-microscopy techniques could be useful for addressing this issue. High-throughput small-interfering-RNA screens should also shed light on molecular requirements for virus-induced membrane modifications.

Many viruses induce the formation of altered membrane structures upon replication in host cells. This Review examines how viruses modify intracellular membranes, highlights similarities between the structures that are induced by viruses from different families and discusses how these structures could be formed.

Abstract

Viruses are intracellular parasites that use the host cell they infect to produce new infectious progeny. Distinct steps of the virus life cycle occur in association with the cytoskeleton or cytoplasmic membranes, which are often modified during infection. Plus-stranded RNA viruses induce membrane proliferations that support the replication of their genomes. Similarly, cytoplasmic replication of some DNA viruses occurs in association with modified cellular membranes. We describe how viruses modify intracellular membranes, highlight similarities between the structures that are induced by viruses of different families and discuss how these structures could be formed.

Main

Viruses are small, obligatory-intracellular parasites that contain either DNA or RNA as their genetic material. They depend entirely on host cells to replicate their genomes and produce infectious progeny. Viral penetration into the host cell is followed by genome uncoating, genome expression and replication, assembly of new virions and their egress. These steps can occur in close association with cellular structures, in particular cellular membranes and the cytoskeleton. Viruses are known to manipulate cells to facilitate their replication cycle, and some induce impressive intracellular membrane alterations that are devoted to the efficient replication of their genomes. Of these, viruses that have a single-stranded RNA genome of positive polarity ((+)RNA viruses) are the best investigated. However, membrane-bound viral-cytoplasmic replication is not restricted to RNA viruses, as exemplified by poxviruses, which are large DNA viruses that replicate their DNA in the cytoplasm.

The observation that viruses induce membrane alterations in infected cells was made many decades ago by electron microscopy (EM). Based on morphological resemblance it was proposed that the formation of these structures must be similar to cellular-membrane biogenesis. A recent focus of research at the interface between virology and cell biology is the dissection of the molecular requirements that underlie the formation of virus-induced membrane rearrangements. In this Review, we discuss how viruses modify intracellular membranes, highlight possible similarities between the structures that are induced by viruses of different families and discuss how these structures could be formed. Given that the biogenesis of these striking structures involves interplay between the virus and the host cell, the role of both viral and cellular proteins is addressed.

Viruses and membranes

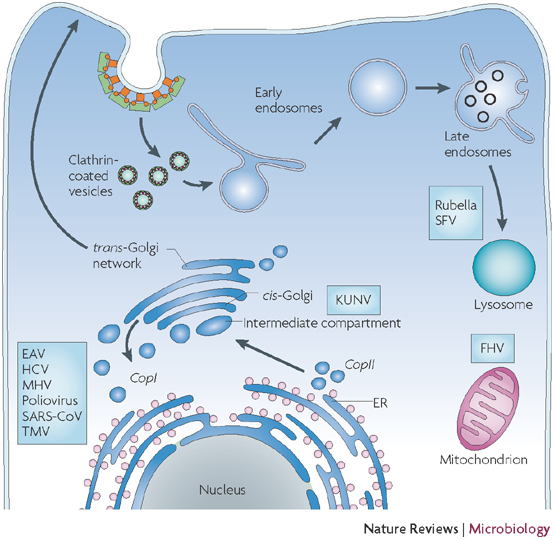

The cellular players. Cells are equipped with two major trafficking pathways to secrete and internalize material: the secretory and endocytic pathways (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Intracellular trafficking pathways and sites of membrane alterations that are induced by different viruses.

Schematic representation of a cell and different intracellular organelles. Proteins that are destined for secretion enter the secretory pathway by co-translational translocation into the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (pink dots represent ribosomes). These proteins are then transported in a coatomer protein complex (COP) II-dependent way to the Golgi complex in a process that probably involves COPII-coated vesicles and membrane structures that are located in the intermediate compartment between the ER and the Golgi complex. Proteins can be recycled back to the ER using COPI-coated vesicles or can be transported through the Golgi complex. At the trans–Golgi network, they leave the Golgi and are transported to the plasma membrane. Endocytosis is initiated at the plasma membrane, and proteins are packed into clathrin-coated vesicles before being transported to early and late endosomes. From there, they are either recycled back to the plasma membrane or are degraded in lysosomes. The putative sites where different viruses modify intracellular membranes to assemble their replication complexes are indicated. EAV, equine arteritis virus; FHV, flock house virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; KUNV, Kunjin virus; MHV, murine hepatitis virus; SARS-CoV, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus; SFV, Semliki Forest virus; TMV, tobacco mosaic virus.

Proteins that are destined for the extracellular environment enter the secretory pathway upon co-translational translocation into the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). They are subsequently transported through vesicular intermediates from the ER to the Golgi complex and then to the cell surface, where, upon fusion of the vesicle and the plasma membrane, they are either released to the extracellular milieu or inserted into the plasma membrane.

Endocytosis is initiated at the plasma membrane, and proteins can be transported to both early and late endosomes. Depending on their fate, internalized molecules can be degraded in late endosomes or lysosomes or be recycled to earlier endocytic compartments and the plasma membrane. Transport vesicles of between 50 and 80 nm in size are thought to mediate transport between cellular compartments1: they bud from the donor compartment and fuse with the acceptor compartment to deliver their cargo. Budding and vesicle formation is mediated by coat proteins, such as coatomer protein complex (COP) I and II, and clathrin coats. COPI and II have been proposed to mediate retrograde and anterograde transport between the ER and the Golgi complex respectively, whereas clathrin is associated with endocytic trafficking (reviewed in Ref. 2) (Fig. 1).

The viral players. (+)RNA viruses are well known for replicating their genomes on intracellular membranes (Tables 1, 2). Examples of (+)RNA viruses include members of the Picornaviridae, Flaviviridae, Togaviridae, Coronaviridae and Arteriviridae families, the insect viruses of the Nodaviridae family and many plant viruses, such as tobacco mosaic virus (TMV). One of the best-documented examples of a virus that induces membrane alterations is the human pathogen poliovirus (PV), a member of the Picornaviridae family and the causative agent of poliomyelitis. Other members of this family are the coxsackieviruses, human pathogens that usually cause only mild diseases. Members of the Flaviviridae family are small, enveloped viruses, and include the Flavivirus, Pestivirus and Hepacivirus genera. The Flavivirus genus comprises more than 70 viruses, many of which are arthropod-borne human pathogens that cause a range of diseases, including fevers, encephalitis and haemorrhagic fever. Flaviviruses include yellow fever virus (YFV), dengue virus (DENV), West Nile virus (WNV) and Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV)3. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is the best-studied member of the Hepacivirus genus. HCV infection is a major cause of chronic hepatitis, liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, and affects 170 million people worldwide4. Two viruses that are closely related to HCV, GB virus (GBV) and bovine viral diarrhoea virus (BVDV), are often used as model systems for HCV owing to the ease of handling of these viruses in cell culture. Two well-studied viruses from the Togaviridae family are the alphavirus Semliki Forest virus (SFV) and the rubivirus rubella virus. The mosquito-borne SFV, which is endemic in Africa, India and south-eastern parts of Asia, is non-pathogenic for humans. By contrast, rubella virus infection causes a self-limiting disease in humans that is known as rubella or German measles. In utero infection with this virus can have serious consequences for the developing foetus. The Coronaviridae and Arteriviridae families, which are unified in the order Nidovirales, include murine hepatitis virus (MHV), equine arteritis virus (EAV) and the human pathogen severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV).

Table 1.

Overview of viruses and their induced membranes*

| Poliovirus | Coxsackieviruses | Kunjin virus | Dengue virus | Hepatitis C virus | Semliki Forest virus | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family | Picornaviridae | Picornaviridae | Flaviviridae | Flaviviridae | Flaviviridae | Togaviridae |

| Genus | Enterovirus | Enterovirus | Flavivirus | Flavivirus | Hepacivirus | Alphavirus |

| Host | Humans | Humans | Humans, mosquitoes and birds | Humans and mosquitoes | Humans | Rodents, humans and mosquitoes |

| Disease | Gastrointestinal infections and poliomyelitis | Asymptomatic and hand-foot-and-mouth disease | Asymptomatic and encephalitis | Dengue fever, haemorrhagic fever and shock syndrome | Hepatitis | Encephalitis |

| Enveloped | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Approximate genome size | 8,000 bases | 8,000 bases | 10,000 bases | 10,000 bases | 10,000 bases | 13,000 bases |

| Approximate particle size | 30 nm | 30 nm | 50 nm | 50 nm | 50 nm | 70 nm |

| Name of induced intracellular structures | Vesicles or rosette-like structures | Vesicles | Convoluted membranes or paracrystalline arrays and smooth membrane structures (after chemical fixation) or vesicle packets (after cryofixation120) | Vesicle packets; double-membrane vesicles | Membranous web | Cytopathic vacuoles |

| Description of induced intracellular structures | Clusters of vesicles, which, after isolation, are associated as rosette-like structures | Cluster of vesicles | Convoluted membranes or paracrystalline arrays, randomly folded or ordered membranes; smooth membrane structures or vesicle packets, clusters of double-membrane vesicles | Clusters of double-membrane vesicles | Cluster of tiny vesicles that are embedded in a membranous matrix | Spherule-lined cytopathic vacuoles |

| Approximate size of induced intracellular structures | 70–400 nm | 70–400 nm | 50–150 nm per vesicle | 80–150 nm per vesicle | 80–150 nm per vesicle | 600–4,000 nm; spherules 50 nm |

| Origin of induced intracellular structures | Endoplasmic reticulum (ER), trans–Golgi and lysosomes | Endoplasmic reticulum (ER), trans–Golgi and lysosomes | Convoluted membranes or paracrystalline arrays, ER and ER–Golgi intermediate compartments; smooth membrane structures or vesicle packets, trans-Golgi | Probably ER | Probably ER | Endosomes and lysosomes |

| Assumed function of induced intracellular structures | Viral RNA replication | Viral RNA replication | Convoluted membranes or paracrystalline arrays, translation and polyprotein processing; smooth membrane structures or vesicle packets, viral RNA replication | Viral RNA replication | Viral RNA replication | Viral RNA replication |

| *Continued in Table 2. | ||||||

Table 2.

Overview of viruses and their induced membranes*

| Rubella virus | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus | Murine hepatitis virus | Equine arteritis virus | Flock house virus | Tobacco mosaic virus | Vaccinia virus | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family | Togaviridae | Coronaviridae | Coronaviridae | Arteriviridae | Nodaviridae | Unranked | Poxviridae |

| Genus | Rubivirus | Coronavirus | Coronavirus | Arterivirus | Alphanodavirus | Tobamovirus | Orthopoxvirus |

| Host | Humans | Humans | Mice | Horses and donkeys | Insects | Plants (Solanaceae) | Humans |

| Disease | German measles | Severe acute respiratory syndrome | Epidemic murine illness | Asymptomatic and haemorrhagic fever | None | Plant diseases | Vaccine strain (smallpox vaccination) |

| Enveloped | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Approximate genome size | 10,000 bases | 30,000 bases | 30,000 bases | 13,000 bases | 4,500 bases | 6,400 bases | 190,000 bases |

| Approximate particle size | 70 nm | 80–160 nm | 80–160 nm | 40–60 nm | 30 nm | 300 × 18 nm | 360 × 270 × 250 nm |

| Name of induced intracellular structures | Cytopathic vacuoles | Double-membrane vesicles | Double-membrane vesicles | Double-membrane vesicles | Spherule-like invaginations | Vesicular structures | Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) enclosure of replication site |

| Description of induced intracellular structures | Spherule-lined cytopathic vacuoles | Vesicular structures that have a double membrane | Vesicular structures that have a double membrane | Perinuclear granules and double-membrane vesicles | Outer mitochondrial membrane that contains numerous spherule-like invaginations | Cytoplasmic inclusions | ER enclosure of replication site |

| Approximate size of induced intracellular structures | 600–4,000 nm; spherules 50 nm | More than 200 nm per vesicle | 80–160 nm per vesicle | 80 nm per vesicle | 40–60 nm per invagination | Unknown | 1–2 μm |

| Origin of induced intracellular structures | Endosomes and lysosomes | Probably rough ER or ER–Golgi intermediate compartment | Probably rough ER or ER–Golgi intermediate compartment | ER | Mitochondria | ER | ER |

| Assumed function of induced intracellular structures | Viral RNA replication | Viral RNA replication | Viral RNA replication | Viral RNA replication | Viral RNA replication | Viral RNA replication | Viral DNA replication |

| *Continued from Table 1. | |||||||

Despite differences in genome organization, virion morphology and host range (Tables 1, 2), these viruses have fundamentally similar strategies for genome replication. By definition, the viral (+)RNA genome has the same polarity as cellular mRNA. Therefore, the genome can be translated by the host cell translation machinery into one or multiple viral polyproteins, which are co- and post-translationally cleaved by viral and host cell proteases into proteins. A large part of the viral genome is devoted to non-structural proteins, which are not part of the virion and carry out important functions during viral replication. Following translation and polyprotein processing, a complex is assembled that includes the viral-RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), further accessory non-structural proteins, viral RNA and host cell factors. These so-called replication complexes (RCs) carry out viral-RNA synthesis. For all (+)RNA viruses that have been investigated so far, the RC seems to be associated with virus-induced membrane structures that are derived from different cellular compartments (Fig. 1). The RCs of members of the flaviviruses, hepaciviruses, coronaviruses, arteriviruses and picornaviruses associate with membranes that are derived from the ER. Togaviruses associate with membranes of endocytic origin instead, whereas nodaviruses associate with mitochondrial membranes (Fig. 1).

Membrane-bound viral cytoplasmic replication is not restricted to (+)RNA viruses, as exemplified by the Poxviridae family. Poxviruses are large, complex DNA viruses that encode approximately 200 proteins5. The prototypic member of this family, vaccinia virus, was used as a live vaccine in a unique worldwide programme that led to the successful eradication of variola virus, the cause of smallpox. Unlike most DNA viruses, poxviruses replicate their DNA in the cytoplasm rather than in the nucleus. As discussed below, this process also occurs in association with intracellular membranes, and we speculate that the way this virus modifies the ER might not be that different to RNA viruses.

Morphology of virus-induced membranes

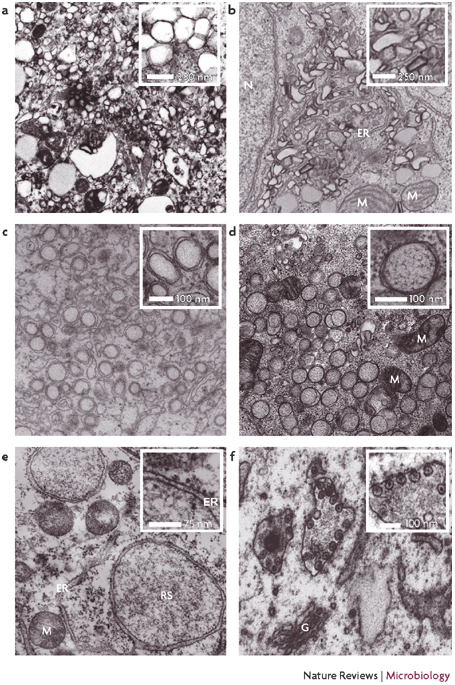

Rather than discussing individual viruses in detail— for which the reader is referred to several excellent reviews6,7,8— we instead aim to highlight similarities among the membrane structures that are induced by different viruses (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Electron microscopy (EM) images of the membrane alterations that are induced by different viruses.

a | Poliovirus-infected HeLa cells fixed 6–8 hours post infection. b | Hepatitis C virus-infected Huh7 cells. c | Dengue virus-infected Huh7 cells fixed 24 hours post infection. d | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-infected Vero cells, showing a cluster of double-membrane vesicles (DMVs). The inset shows one DMV at a higher magnification. e | Vaccinia virus-infected cells, showing a replication site that is surrounded by the rough ER. The inset shows the ER membrane at a higher magnification, with the ribosomes on the outer membrane facing the cytoplasm. f | Semliki Forest virus-infected baby hamster kidney cells fixed 3 hours post infection, showing the typical cytopathic vacuoles that are induced upon infection. ER, endoplasmic reticulum; G, Golgi apparatus; M, mitochondrion; N, nucleus; RS, replication site. Part a is courtesy of K. Bienz and D. Egger, University of Basel, Switzerland; parts b and c are courtesy of R. Bartenschlager, University of Heidelberg, Germany; part d is courtesy of E. Snijder, M. Mommas and K. Knoops, Leiden University, The Netherlands; part e is reproduced, with permission, from Ref. 77 © (2005) Blackwell Publishing; and part f is courtesy of T. Ahola and G. Balistrer, University of Helsinki, Finland.

Modifications of the ER. EM observations made more than 40 years ago described clusters of heterogeneously sized vesicles of 70–400 nm in diameter that were present in the perinuclear regions of PV-infected cells9 (Fig. 2a). PV is the paradigm for a virus that induces membrane alterations to be the site of RNA replication10,11,12, as assessed by in situ hybridization13. PV-induced vesicle clusters are probably derived from the ER, although sub-cellular fractionation revealed that they also contain endocytic and Golgi-complex markers, suggesting a complex biogenesis of these structures (discussed below)14. Other members of the Picornaviridae family have also been shown to replicate their RNA genomes on modified membranes that accumulate in the cytosol of infected cells15. The membrane rearrangements that are involved in RNA replication of HCV, a member of the Flaviviridae family that belongs to the Hepacivirus genus, constitute the membranous web16,17. This structure, which consists of clusters of membrane vesicles that are embedded in a membranous matrix (Fig. 2b), was found to contain HCV non-structural proteins and is probably derived from the ER. Detection of viral (+)RNA that was associated with these web structures using metabolic labelling of the nascent viral RNA with 5-bromouridine 5′-triphosphate (Box 1), revealed that the membranous web is the site of viral-RNA synthesis17. (+)RNA viruses that belong to the Flaviviridae family and the Nidovirales order typically induce the formation of double-membrane vesicles (DMVs) — spherical membrane structures that are 50–400 nm in diameter (Tables 1, 2) and composed of two closely apposed membrane bilayers (Figs 2, 3). The intracellular membrane rearrangements that are induced by the Flaviviridae family are best characterized for Kunjin virus (KUNV), which is the Australian variant of WNV18. KUNV induces two distinct membrane structures (reviewed in detail in Ref. 6): large clusters of DMVs (each vesicle is approximately 50–150 nm in diameter) and a second membrane structure that consists of convoluted membranes and paracrystalline arrays. Immunolabelling studies that used an anti-double-stranded-RNA (dsRNA) antibody revealed that DMVs are the site of viral replication, whereas convoluted membranes are the sites of viral polyprotein processing19. Clusters of DMVs have also been observed for other flaviviruses (for example, DENV) (Fig. 2c), but these have not been characterized in the same detail as for KUNV. For the coronavirus MHV and the arterivirus EAV, both of which are members of the Nidovirales order, newly synthesized RNA was found to localize to virus-induced DMVs20,21. These DMVs, which are approximately 80–160 nm in diameter, seem to be derived from the ER. DMVs with a diameter of up to 400 nm were also observed in cells that were infected with the human pathogen SARS-CoV (Fig. 2d). In common with EAV and MHV, microscopic studies identified the ER as the most likely source of membranes for the SARS-CoV DMVs22,23. One of the many (+)RNA plant viruses that are known to induce membrane rearrangements in infected cells24,25,26,27 is TMV28. In TMV-infected cells, viral RCs associate with cytoplasmic inclusions, which consist of membrane rearrangements and amorphous proliferation of the ER, which expands throughout infection29.

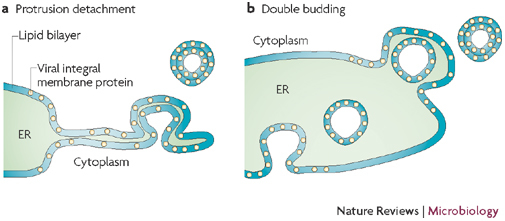

Figure 3. Models for the formation of virus-induced double-membrane vesicles.

The protrusion and detachment model (a) proposes that part of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) cisterna starts to bend, pinches off and then seals to form a double-membrane vesicle (DMV). Interactions between the lumenal domains of viral membrane proteins (coloured yellow in the ER membrane) could mediate the tight apposition of the two bilayers and induce curvature. In the double-budding model (b), a single-membrane vesicle buds into the lumen of the ER and then buds out again, and the membrane proteins could mediate inward as well as outward budding. Figure adapted, with permission, from Ref. 20 © (1999) American Society for Microbiology.

As observed by EM, clusters of vesicles or DMVs that are induced by some of the RNA viruses might be intimately associated with the ER. The DMVs that are found in EAV- and MHV-infected cells seem to be connected to the ER by their outer membranes20. KUNV vesicle packets are completely surrounded by the ER, which led to the suggestion that the DMVs are actually inside the lumen of the ER (reviewed in Ref. 6). Similarly, the HCV membranous web is delineated by a cisterna that is reminiscent of the rough ER (Fig. 2b).

The poxvirus vaccinia virus represents a striking example in which cisternae that are derived from the rough ER enclose the cytoplasmic site of viral-DNA replication. DNA viruses commonly replicate their DNA in the nucleus of infected cells, but poxviruses are an exception, as they can replicate their DNA in discrete cytoplasmic foci30,31. These foci, which label positively for the DNA dye Hoechst or anti-DNA antibodies, were first thought to be free in the cytoplasm. However, EM studies revealed that the foci become surrounded by the rough ER and eventually resemble a cytoplasmic mini-nucleus32 (Fig. 2e).

Modification of endosomes: the Togaviridae. Other well-known (+)RNA viruses that are able to induce membrane reorganization in infected cells belong to the Togaviridae family. RNA synthesis of togaviruses takes place in the cytoplasm in association with characteristic virus-induced membrane rearrangements that are named cytopathic vacuoles (CPVs) (Fig. 2f). Both nascent viral RNA and viral non-structural proteins localize to the CPVs that are induced by SFV and rubella virus33,34,35. CPVs are modified endosomal and lysosomal structures that are 600–2,000 nm in size. The use of endosomes and lysosomes as sites of viral replication seems to be unique to the Togaviridae family36. The CPV surface consists of small vesicular invaginations or spherules of homogenous size that have a diameter of approximately 50 nm and line the vacuole membrane at regular intervals37,38,39. EM analysis revealed that thread-like ribonucleoprotein structures extend from the inside of the spherules to the cytoplasmic face of SFV CPVs. Viral RNA polymerase is also present in large, branching, granular and thread-like structures that are anchored to the cytoplasmic surface of CPVs at the spherules. Interestingly, the ER is present in close proximity to alphavirus CPVs and is implicated in providing efficient translation of the viral glycoproteins that are required for assembly.

Replication on mitochondria and peroxisomal membranes: insect viruses. In addition to the viruses described above, which mainly infect humans and other mammals, many (+)RNA viruses use insect and plant cells as their natural hosts. For example, flock house virus (FHV), an insect virus that belongs to the Nodaviridae family, assembles its RC on mitochondrial membranes. The outer-mitochondrial membrane of FHV-infected Drosophila spp. cells contains numerous virus-induced spherule-like invaginations that are 40–60 nm in diameter and are connected to the cytoplasm by necked channels40. These invaginations are the putative sites of viral-RNA replication. Other plant viruses are known to replicate on the surface of peroxisomes; for example, tomato bushy stunt virus (TBSV), a member of the Tombusviridae family41. However, in the absence of peroxisomes, replication of this virus switches to the ER42. This might indicate that at least some RNA viruses have remarkable flexibility for using different host membranes to anchor their RC.

Functions of membrane alterations

The role of the virus-induced membrane structures discussed above in regards to viral-RNA synthesis is not well understood. However, they have been proposed to help to increase the local concentration of components required for replication; provide a scaffold for anchoring the RC; confine the process of RNA replication to a specific cytoplasmic location; aid in preventing the activation of certain host defence mechanisms that can be triggered by dsRNA intermediates of RNA-virus replication; tether viral RNA during unwinding; and provide certain lipids that are required for genome synthesis. The ER, endosomes or mitochondrial membranes provide an abundant membrane source that can easily expand and be rearranged, which could be the reason why these membranes are preferentially used.

Biogenesis of membrane structures

Although viruses have long been known to induce membrane rearrangements, it is only recently that some of the mechanisms that are responsible for the formation of these structures have begun to be unravelled. Despite the substantial progress that has been made during the past few years, we are still far from understanding this complex process in detail. In the following sections, we summarize what is known about the role of both viral and cellular proteins in virus-induced membrane reorganization.

Membrane alterations induced by individual viral proteins. Several studies showed that the ectopic expression of individual viral proteins in cultured cells induces membrane structures that seem to be similar to those observed in infected cells. Thus, expression of the enterovirus non-structural protein 2BC, possibly in conjunction with the 3A protein, induces the formation of membrane vesicles that are comparable to the membranes involved in viral-RNA replication in infected cells12,43,44,45. Furthermore, the flavivirus non-structural protein 4A, a small, hydrophobic transmembrane protein that localizes to the presumed sites of RNA replication and polyprotein processing46,47, induces intracellular membrane rearrangements that might form the scaffold for the viral RC47,48. Expression of the small, polytopic transmembrane protein NS4B of HCV was shown by EM to induce a membrane alteration that is similar to the membranous web that is found in cells which express the entire polyprotein or harbour subgenomic HCV replicons17. For EAV, heterologous expression of the nsp2–nsp3 region of the viral replicase induces the formation of paired membranes and DMVs that, at the ultra-structural level, resemble those seen in EAV-infected cells. However, no DMVs were observed when these proteins, which are both tightly associated with intracellular membranes21, were expressed individually49.

Although these studies are promising, how individual viral proteins can promote the formation of these remarkable membrane alterations remains largely unexplained. Given that the membranes involved are of cellular origin, it is likely that cellular factors play an important part, as discussed in the examples below.

The role of cellular factors. The potential role of cellular proteins has been best investigated, but is far from being completely understood, for the enteroviruses PV and the coxsackieviruses, members of the Picornaviridae family. Both preferentially use molecules that are involved in intracellular transport. Components of the COPII complex, which is known to be responsible for ER–Golgi transport, were found to colocalize with virus-induced vesicles in the case of PV50, and it was therefore proposed that ER–Golgi transport intermediates might initiate formation of the PV-modified membranes that are involved in RNA replication.

ADP-ribosylation factors (ARFs) and their associated proteins were also shown to localize to the membranes that are modified by PV. ARFs are a family of small GTPases that play a central part in the regulation of membrane dynamics and protein transport. ARFs cycle between an active GTP- and an inactive GDP-bound form. In their active states, ARFs can initiate formation of a vesicular intermediate by inducing membrane curvature (discussed below) and attracting effectors that are required for vesicle formation. Activation of GDP-bound ARFs is mediated by so-called guanine nucleotide-exchange factors (GEFs), which form a transient complex with ARF–GDP51. ARF1 in particular is implicated in the recruitment of the COPI complex, which is involved in retrograde ER–Golgi transport. Biochemical and light-microscopy analyses showed that the PV non-structural proteins 3A and 3CD recruit the ARF–GEFs GBF1 and BIG1/2, respectively, which, in turn recruit ARF1, 3 and 5 to virus-induced membrane structures52,53. ARF1 recruitment to membranes was shown to be required for viral replication in vitro, and was proposed to be involved in virus-induced membrane remodelling in vivo53. The putative involvement of components of both the anterograde and retrograde pathways, which are required for ER–Golgi trafficking, allows for a highly speculative model on the biogenesis of PV vesicle clusters. The use of COPII components could mediate the initial formation of the vesicle clusters that are formed from ER-derived transport intermediates. ARF1 or GBF1 recruitment could prevent COPI binding and consequently prevent recycling of membranes of the vesicles clusters back to the ER, thereby leading to a stable membrane compartment that supports viral replication (reviewed in detail in Ref. 54).

The possible involvement of ARFs in membrane remodelling might not apply, however, to the coxsackieviruses. Coxsackievirus 3A was shown to interact with the ARF–GEF GBF1. However, in contrast to PV, this interaction led to dissociation of ARF1 from membranes55, which excluded a role for this GTPase in coxsackievirus membrane remodelling. Consistent with this, and in contrast to PV, the interaction of coxsackievirus 3A with GBF1 is not essential for virus replication55,56,57. The interaction between coxsackievirus 3A and GBF1 instead seems to result in an inhibition of ER–Golgi transport. It has been known for some time that in both PV- and coxsackievirus-infected cells, ER–Golgi transport is blocked58,59. For PV, ARF1 recruitment to membranes could underlie this inhibition by diverting GTPase from its normal function in ER–Golgi trafficking. For coxsackieviruses, however, the interaction of 3A with GBF1 actually inhibits ARF1 activation and membrane recruitment by stabilizing ARF–GEF GBF1 on membranes, thereby inhibiting ER–Golgi transport15. The interaction of both PV and coxsackievirus 3A with GBF1 could also explain the sensitivity of enterovirus infection to brefeldin A, as this drug is known to inhibit the activation and function of some GEFs60,61,62,63. Therefore, although both PV and coxsackievirus 3A interact with ARF–GEFs, the function and mode of action of this interaction might be different.

The hepacivirus HCV proteins NS5A and NS5B have been shown to interact with vesicle-associated-membrane protein-associated protein (VAP)64. VAP is a multifunctional protein65,66,67,68,69,70 that is involved in intracellular transport, including the regulation of COPI-mediated transport71,72. VAP was found to be crucial for the formation of HCV RCs and RNA replication73, and was shown to interact with the cellular protein NIR2 and remodel the structure of the ER74. NIR2 belongs to a highly conserved family of proteins, the NIR/RdgB family, which are implicated in the regulation of membrane trafficking, phospholipid metabolism and signalling75. It was thus proposed that VAPs remodel the ER by interacting with NIR2 to mediate formation of the HCV membranes that are involved in replication76.

For vaccinia virus, ER wrapping around the viral replication site seemed to be a dynamic process. Early in infection, individual ER cisternae were found to be attracted to the replication site until it became almost entirely surrounded by the ER, and late in infection, when DNA-replication ceased, the ER typically dissociated from the replication site. It was proposed that a viral membrane protein is involved in the initial recruitment of ER cisternae and that their fusion to form a sealed double envelope around the DNA sites is mediated by the host cell ER-fusion machinery77; however, further experiments are required to support this theory. Taken together, the findings discussed above indicate that viruses have evolved elaborate strategies to modify cellular mechanisms that are involved in vesiculation and transport for their own purposes. Although some cellular-interaction partners have been identified, a detailed understanding of the molecular mechanisms of membrane remodelling by viruses is still lacking.

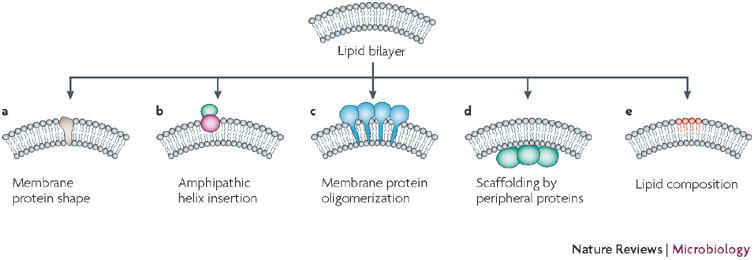

Viral proteins, membrane curvature and vesicle induction — a speculative model. Although individual viral proteins can induce alterations of intracellular host cell membrane structures (discussed above), how these proteins act is not clear. The formation of a double-membrane vesicle implies two fundamental cellular mechanisms: membrane bending and formation of two parallel lipid bilayers. Membrane bending can be induced in several different ways (Fig. 4); for example, membrane proteins could induce curvature by a characteristic conical shape or oligomerization. Curvature can also be induced by peripheral association of scaffolding proteins, such as coat proteins (reviewed in Refs 2,78,79,80) (Fig. 3). Well-investigated examples are the coatomer proteins COPI and II, as well as clathrin (reviewed in Refs 2,78), which induce curvature of cellular membranes, followed by budding of vesicles from donor compartments. Of particular interest to this Review are proteins that have an amphipathic helix and internal α-helical stretches, which have one polar (charged) and one hydrophobic side; these proteins have the ability to associate with one of the two leaflets of a membrane, thereby creating asymmetry and membrane bending79 (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Mechanisms of membrane-curvature induction.

Several mechanisms of membrane deformation by cellular proteins have been described. a | Integration of membrane proteins that have a conical shape induces curvature, as they act like a wedge that is inserted into the membrane. b | Amphipathic helices, stretches of alpha helices that have one polar and one hydrophobic side, are positioned flat on the membrane, with the hydrophobic side dipping into one of the two membrane layers: this causes destabilization of the membrane and membrane bending. c,d | Membrane bending can be induced by oligomerization of proteins that are integrated into, or associated with, cellular membranes. Proteins form a scaffold that makes the membrane bend. e | The lipid composition of a membrane can also induce membrane curvature. In this context, the head group, as well as the acyl chain of the membrane constituents, can have an effect on membrane curvature. Figure adapted, with permission, from Nature Ref. 79 © (2005) Macmillan Publishers Ltd.

Viral factors could activate or recruit cellular components that are required for membrane bending. As described above, individual viral proteins of PV recruit ARFs and ARF–GEFs. Interestingly, ARFs contain an amino-terminal amphipathic helix and are able to induce membrane bending81,82. PV therefore seems to recruit more than one cellular factor that has been shown to be implicated in membrane curvature to its RCs. Definitive proof that these cellular proteins mediate the curvature of PV vesicles is lacking. Moreover, as explained above for the coxsackieviruses, the involvement of ARF1 in membrane remodelling and curvature seems unlikely.

Alternatively, viral-replicase subunits could induce membrane curvature on their own, using mechanisms that are similar to those described for cellular proteins. Interestingly, a substantial number of viral proteins that are implicated in membrane-bound viral-RNA-replication (discussed above) seem to contain amphipathic helices83,84,85,86,87. PV protein 2C, as well as the NS4A and NS5A proteins of HCV, GBV and BVDV, which are involved in replication, also contain conserved amphipathic helices. One function of these sequences is to mediate membrane association of these proteins84,88. Recent observations of HCV NS4B suggest that such a sequence could also be involved in membrane bending or curvature89. NS4B was shown to induce membrane alterations when expressed independently17 and contains an amino-terminal amphipathic helix that might be required for the induction of membrane alterations. NS4B has also been reported to form homo-oligomers that seem to be required for the induction of membrane alterations89,90. Thus, analogous to the cellular process of membrane bending, a speculative model is that NS4B induces curvature by inserting its amphipathic helix into membranes. Oligomerization might then lead to large complexes that force the membrane to remain curved. A similar mechanism could be used by the DENV and KUNV flavivirus NS4A proteins, which can both induce membrane alterations47,48. Flavivirus NS4A contains a region that seems to span only one of the two lipid layers of the membrane, and has been proposed to form oligomers46,47. Given that a large number of non-structural proteins of (+)RNA viruses contain amphipathic helices91,92 and are able to oligomerize, it is possible that this highly speculative model could also apply to other RNA viruses. An additional function of oligomerization could be to concentrate and cluster the non-structural proteins into a functional RC, such as that proposed for PV93. Lyle et al.93 found that membranous vesicles isolated from PV-infected cells were covered with a catalytic shell of oligomerized polymerase molecules, which might represent the site of RNA replication. The observed two-dimensional lattices of enzyme might act in an analogous way to surface catalysts.

What mechanism underlies formation of the paired membranes that characterize DMVs? One model suggests that DMVs originate from the ER by protrusion and detachment20 (Fig. 4). In this model, part of an ER cisterna bends and the two lipid bilayers become more tightly apposed. The curved cisternal membranes may then pinch off and seal to form a double-membraned vesicle. Formation of paired membranes could be a result of an interaction between the lumenal domains of viral transmembrane proteins across the ER lumen. The mechanisms that are proposed to induce curvature (for example, amphiphatic helix insertion and oligomerization) could then aid in stabilizing membranes and prevent back-fusion with the ER or other membranes.

An alternative model for DMV formation is the so-called double-budding mechanism20 (Fig. 4). In this model, a vesicle buds into the ER lumen, from which it is subsequently released by a second budding event, thereby acquiring a second membrane to give rise to a DMV. This model would require a mechanism that prevents the transient lumenal vesicle from fusing with the ER membrane and instead allows it to bud out. Although there is no precedent for this mechanism in the cell, similar to the protrusion and detachment model, interactions between viral membrane proteins that are exposed on the vesicle surface and in the ER lumen could underlie such a mechanism.

Viral replication and autophagy

Autophagy is a cellular process that results in degradation of part of the cell's cytoplasm and can be initiated in response to stress, infection by pathogens and starvation. Nutrient-limiting conditions have been used extensively to dissect autophagy both at the morphological and molecular levels94,95. Morphologically, the process starts with sequestration of the cytoplasmic content into a crescent-shaped double membrane. The origin of this membrane is debated, but it is probably derived from a specialized domain of the ER96. The crescent matures into double-membraned vesicles that enclose the cytoplasmic content, known as the autophagosome, which has a diameter of up to 1,500 nm in mammalian cells and 900 nm in yeast. Upon fusion with late endosomes or lysosomes, the autophagosome acquires lysosomal enzymes that degrade its internal content. The molecules that are involved in autophagy have been dissected in detail using yeast genetics. At least 27 autophagy-related (Atg) genes have been identified in yeast. It is beyond the scope of this Review to describe the roles of Atg genes in detail (reviewed in Refs 94,95). However, two are worth mentioning: Atg5, a protein that is required for formation of the crescent membrane, and Atg8. Furthermore, the light-chain 3 (LC3) protein becomes lipidated in response to autophagy and is associated with the autophagosomal membrane95. A putative link between virus-induced vesicles and the process of autophagy was proposed many years ago by George Palade and colleagues9, who used EM studies to show that PV induced vesicles that resembled autophagosomal membranes.

Could the formation of vesicles that are induced by coronaviruses, poliovirus and flaviviruses, which are, on average, significantly smaller in diameter than autophagosomes, be caused by mechanisms that are similar to autophagy? Like autophagosomal membranes, most virus-induced vesicles are ER derived. PV vesicle clusters have been shown to contain LC3 and lysosomal markers, suggesting the possible involvement of late steps of autophagy45. However, small-interfering-RNA (siRNA)-mediated knockout of LC3 and Atg12, an Atg that forms a complex with Atg5, inhibited the release of infectious virus without significantly affecting replication97. These results inspired the authors to propose a scenario in which the PV replicative vesicles are involved in virus egress, a step that requires LC3 and Atg12 (Ref. 97). In one study, LC3 was also shown to localize to coronavirus-induced vesicles98, but this could not be confirmed in two subsequent studies of SARS-CoV22,23. Infection of cells that were derived from Atg5-knockout mice with the coronavirus MHV was shown to significantly affect virus yields, suggesting that initial stages of autophagy might be required for the production of infectious progeny98. Morphological similarities to the process of autophagy are particularly striking in two steps of the poxvirus replication cycle. The dynamics of ER wrapping around the sites of cytoplasmically synthesized viral DNA resembles the formation of autophagosomes: ER-derived cisternae are recruited to the cytoplasmic sites of replication and, eventually, almost entirely enclose the replication sites with a double membrane that is derived from the ER32. Another morphological similarity is observed during the assembly of new virions; for poxviruses, the precursor membrane of virus assembly is a crescent-shaped membrane that is ER derived and associates with cytoplasmically synthesized viral core proteins. These then form a spherical immature virion that is composed of a membrane which encloses cytoplasmic core proteins99. A recent study, however, showed that Atg5 is not required for the formation of infectious progeny virus, which provides compelling evidence against a role for autophagy in the vaccinia virus replication cycle100.

Thus, despite the striking morphological similarities, these collective data argue against a role for autophagy in the formation of virus-modified membranes that are involved in replication.

The topology of replication

Membrane binding of the RC. Most of the viruses described in this Review encode one or more membrane proteins in the non-structural region of the viral genome, which ensures membrane-association of the RC. Examples include: the NS4A and NS4B proteins of DENV and HCV; FHV protein A; and PV 3A47,89,101,102,103. By analogy to cellular-membrane proteins, membrane association of these viral membrane proteins could occur via co-translational membrane insertion on ER-bound ribosomes. An exception seems to be the catalytic subunit of the HCV RdRp NS5B. NS5B contains a carboxy-terminal hydrophobic region, and, similar to tail-anchored cellular proteins104, is inserted post-translationally into membranes4. Membrane-association of viral replication factors can also be mediated by an amphipathic helix, as shown for SFV NSP1 and HCV NS4B and NS5A83,85,105,106. Membrane binding via lipid modifications has also been described (for example, palmitoylation of SFV NSP1)107. Viral non-structural proteins that lack membrane anchors associate with membranes through a tight interaction with viral-membrane-anchored proteins. Indeed, non-structural proteins of several viruses have been shown to exist in large complexes and, in many cases, protein–protein interactions of helicase and polymerase domains have been described108,109,110,111,112.

As mentioned previously, the genomes of (+)RNA viruses are expressed as one or more polyproteins. This strategy evidently facilitates the targeting and assembly of all factors to the same location. Strictly regulated processing events of the polyprotein may further contribute to the proper membrane-associated assembly of the RC. The importance of tightly regulated assembly is exemplified by the fact that it is difficult to trans-complement some proteins in the RCs of several (+)RNA viruses113.

Orientation of the viral RC. In profiles of conventional EM, virus-induced vesicles appear to be 'closed' upon themselves (Fig. 2). A closed vesicle structure implies that viral RNA is synthesized on, and localized to, the cytoplasmically oriented outer membrane, as the RNA is subsequently packaged by core proteins that are localized in the cytoplasm. In fact, nascent PV RNA and viral replication proteins are reported to be associated with the outside surfaces of virus-induced vesicles. Extensive studies have shown that viral RNA replication occurs in the space that is enclosed and surrounded by the cluster of induced-vesicle rosettes11,114,115. By contrast, it was proposed that the non-structural proteins and viral RNA of HCV are associated with the inner membrane of HCV induced vesicles116. These vesicles could contain a small, neck-like structure that allows the constant supply of nucleotides for RNA synthesis. Presumably, molecules that are larger than 16 kDa cannot pass through this neck owing to size limitations116 (Fig. 5). Such neck-like connections have also been postulated for other viruses; for example, togaviruses, arteriviruses and nodaviruses20,33,40. Consequently, these vesicles could wrap the RC inside a membrane cisterna, thereby shielding it, but not closing it off, from the surrounding cytoplasm. Importantly, such a structure (known as an open membrane wrap) cannot be formed by single membrane structures, as these are inherently closed upon themselves; this might explain why several viruses from different families form DMVs for replication. Finally, putative neck-like structures could provide a means to regulate trafficking of molecules between the inside of the vesicle and the surrounding cytoplasm.

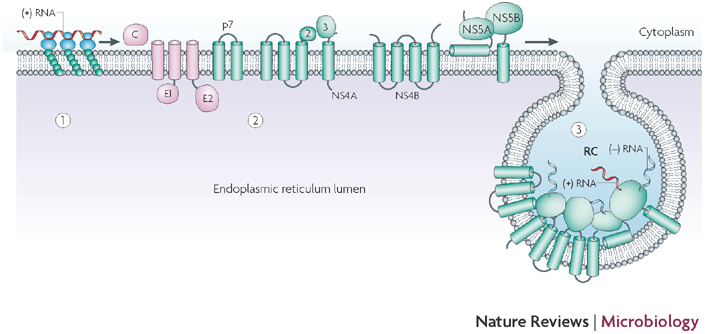

Figure 5. Hypothetical model for biogenesis and topology of the hepatitis C virus replication complex.

Upon release of viral genomic RNA into the cytoplasm of the infected cell (1), the viral genome is translated into a polyprotein that carries the structural (pink) and non-structural (green) proteins (2). The viral non-structural protein NS4B induces the formation of membrane alterations, which serve as a scaffold for the assembly of the viral replication complex (RC) (3). The RC consists of viral non-structural proteins, viral RNA and host cell factors. Within the induced vesicles, viral RNA is amplified via a negative-strand RNA intermediate. Figure adapted, with permission, from Ref. 116 © (2005) American Society for Microbiology.

EM has shown that the poxvirus replication site, which seems to be entirely surrounded by an ER membrane, also has interruptions32. Similar to DMV neck-like structures, these interruptions could provide ways to exchange molecules between the inside and outside of the poxvirus replication site77. The DMV formation or ER wrapping that has been observed in RNA and DNA viruses would thus underlie the same principle: the wrapping of an ER-derived cisterna around the replication machinery and newly synthesized genomes, the function of which is to shield the replication site without completely closing it off from the surrounding cytoplasm.

As mentioned above, the impression that virus-induced vesicles are closed upon themselves might be biased by observations that have been made using conventional EM: the thin sectioning that is used in this technique provides two-dimensional images of vesicles and, because the putative neck-like structures are located in only one small part of the vesicle structure, in most EM profiles they could look closed. To overcome this technical limitation, three-dimensional imaging using electron tomography is a useful tool. This method relies on tilting the EM sample and acquiring multiple two-dimensional images that are used to make a three-dimensional model (reviewed in Ref. 117). Indeed, in a recent study on FHV, electron tomography was used to analyse the viral RCs that are associated with mitochondria, and three-dimensional analyses revealed that each spherule maintains an open connection to the cytoplasm that has a diameter of approximately 10 nm118.

Future perspectives

Despite major recent advances in our understanding of the molecular requirements of the viral replication process, many important questions remain unresolved. It is still unclear how viral and cellular proteins contribute to induction of the remarkable membrane alterations that are found in virus-infected cells. Both genetic manipulation of viruses and cell-biology techniques, such as genome-wide siRNA screens119, will probably contribute to identification of the molecules that are involved in this process. Modern ultra-structural techniques, in particular electron tomography (discussed above), might substantially contribute to our understanding of the three-dimensional structure of viral membrane-bound RCs at the highest possible resolution. Electron tomography is also the method of choice to determine to what extent viral RCs are connected to each other and to other organelles, which could contribute to our understanding of the origin and biogenesis of virally induced RCs. If replicative membrane structures rely on the existence of pores or necks, important questions include: how are these structures formed and how do they regulate the transport of molecules into and out of the vesicle? Furthermore, such studies will increase our understanding of membrane dynamics and, hopefully, lead to new ways to combat viruses.

Box 1 | Detection of viral RNA in infected cells.

Several methods are used to specifically detect intracellular viral RNA. One way is to use antibodies that recognize double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), which is an intermediate of plus-stranded RNA-virus replication. The use of dsRNA-specific antibodies in electron or immunofluorescence microscopy can provide information about the putative site of active replication. Another commonly used method is the labelling of newly synthesized viral RNA with 5-bromouridine 5′ triphosphate. This brominated ribonucleotide is an excellent substrate for RNA polymerases, and replaces the natural substrate uridine diphosphate. To specifically label viral RNA, it is necessary to inhibit cellular polymerases using actinomycin D before and during the labelling process. The labelled viral RNA can be localized using electron or immunofluorescence microscopy following labelling with an antibody that is directed against 5-bromouridine. Viral RNA can also be detected by in situ hybridization using single-stranded riboprobes. These probes can be directed against either the negative strand or the plus-strand of viral RNA, and thus it is possible to differentiate between these two RNA species. Virus-specific probes can be generated by either in vitro transcription or PCR. To facilitate detection of probes after in situ hybridization with the corresponding strand of virus RNA, the probes must be labelled with a substance against which a specific antibody is available. A commonly used marker for labelling is digoxigenin, which is conjugated to a single species of RNA nucleotide triphosphate (typically uridine) and incorporated into the riboprobe during synthesis.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank L. Dale, C. Dale, G. Griffiths, J. Mackenzie and E. Snijder for critical reading of the manuscript, and apologize to those colleagues whose work could not be cited appropriately owing to space limitation.

Glossary

- Coatomer

A coat complex that functions in anterograde and retrograde transport between the endoplasmic reticulum and the Golgi apparatus.

- Clathrin

First vesicle coat protein to be identified; involved in membrane trafficking to, and through, the endocytic pathway.

- ARF–GEF

Guanine nucleotide-exchange factor (GEF) for a small G protein of the ARF class. ARFs belong to the Ras superfamily of small GTP-binding proteins. GEFs mediate the conversion, of GTP to GDP.

Biographies

Sven Miller collaborated with Ralf Bartenschlager to obtain his Ph.D. on different aspects of the dengue virus life cycle from the University of Heidelberg, Germany. He became proficient in electron microscopy at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory, Heidelberg, and at the University of Oslo, Norway, while working with Gareth Griffiths, Heinz Schwarz and Norbert Roos. Currently, he works at 3-V Biosciences, Zurich, Switzerland, a spin-off company of the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology.

Jacomine Krijnse-Locker obtained her Ph.D. in 1994 in virology from the University of Utrecht, The Netherlands, before moving to the cell-biology programme at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory in Heidelberg, Germany. She focuses on understanding viruses at the cellular level, using poxviruses as a model system. Currently, she studies and teaches cellular aspects of virology at the University of Heidelberg, using high-resolution electron microscopy techniques.

Related links

DATABASES

Entrez Genome

Contributor Information

Sven Miller, Email: millersven@gmx.de.

Jacomine Krijnse-Locker, Email: krijnse@embl-heidelberg.de.

References

- 1.Klumperman J. Transport between ER and Golgi. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2000;12:445–449. doi: 10.1016/S0955-0674(00)00115-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirchhausen T. Three ways to make a vesicle. Nature Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2000;1:187–198. doi: 10.1038/35043117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mackenzie JS, Gubler DJ, Petersen LR. Emerging flaviviruses: the spread and resurgence of Japanese encephalitis, West Nile and dengue viruses. Nature Med. 2004;10:S98–S109. doi: 10.1038/nm1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moradpour D, Penin F, Rice CM. Replication of hepatitis C virus. Nature Rev. Microbiol. 2007;5:453–463. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moss B, et al. Fields Virology. 2001. pp. 2849–2883. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mackenzie J. Wrapping things up about virus RNA replication. Traffic. 2005;6:967–977. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2005.00339.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Novoa RR, et al. Virus factories: associations of cell organelles for viral replication and morphogenesis. Biol. Cell. 2005;97:147–172. doi: 10.1042/BC20040058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salonen A, Ahola T, Kaariainen L. Viral RNA replication in association with cellular membranes. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2005;285:139–173. doi: 10.1007/3-540-26764-6_5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dales S, Eggers HJ, Tamm I, Palade GE. Electron microscopic study of the formation of poliovirus. Virology. 1965;26:379–389. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(65)90001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bienz K, Egger D, Pasamontes L. Association of polioviral proteins of the P2 genomic region with the viral replication complex and virus-induced membrane synthesis as visualized by electron microscopic immunocytochemistry and autoradiography. Virology. 1987;160:220–226. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(87)90063-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bienz K, Egger D, Pfister T, Troxler M. Structural and functional characterization of the poliovirus replication complex. J. Virol. 1992;66:2740–2747. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.5.2740-2747.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bienz K, Egger D, Rasser Y, Bossart W. Intracellular distribution of poliovirus proteins and the induction of virus-specific cytoplasmic structures. Virology. 1983;131:39–48. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(83)90531-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Egger D, Bienz K. Intracellular location and translocation of silent and active poliovirus replication complexes. J. Gen. Virol. 2005;86:707–718. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80442-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schlegel A, Giddings TH, Jr, Ladinsky MS, Kirkegaard K. Cellular origin and ultrastructure of membranes induced during poliovirus infection. J. Virol. 1996;70:6576–6588. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.10.6576-6588.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wessels E, et al. A viral protein that blocks Arf1-mediated COP-I assembly by inhibiting the guanine nucleotide exchange factor GBF1. Dev. Cell. 2006;11:191–201. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Egger D, et al. Expression of hepatitis C virus proteins induces distinct membrane alterations including a candidate viral replication complex. J. Virol. 2002;76:5974–5984. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.12.5974-5984.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gosert R, et al. Identification of the hepatitis C virus RNA replication complex in Huh-7 cells harboring subgenomic replicons. J. Virol. 2003;77:5487–5492. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.9.5487-5492.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hall RA, Scherret JH, Mackenzie JS. Kunjin virus: an Australian variant of West Nile? Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 2001;951:153–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb02693.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Westaway EG, Mackenzie JM, Khromykh AA. Kunjin RNA replication and applications of Kunjin replicons. Adv. Virus Res. 2003;59:99–140. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(03)59004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pedersen KW, van der Meer Y, Roos N, Snijder EJ. Open reading frame 1a-encoded subunits of the arterivirus replicase induce endoplasmic reticulum-derived double-membrane vesicles which carry the viral replication complex. J. Virol. 1999;73:2016–2026. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.3.2016-2026.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Meer Y, van Tol H, Locker JK, Snijder EJ. ORF1a-encoded replicase subunits are involved in the membrane association of the arterivirus replication complex. J. Virol. 1998;72:6689–6698. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.8.6689-6698.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Snijder EJ, et al. Ultrastructure and origin of membrane vesicles associated with the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus replication complex. J. Virol. 2006;80:5927–5940. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02501-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stertz S, et al. The intracellular sites of early replication and budding of SARS-coronavirus. Virology. 2007;361:304–315. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prod'homme D, Le Panse S, Drugeon G, Jupin I. Detection and subcellular localization of the turnip yellow mosaic virus 66K replication protein in infected cells. Virology. 2001;281:88–101. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Restrepo-Hartwig MA, Ahlquist P. Brome mosaic virus helicase- and polymerase-like proteins colocalize on the endoplasmic reticulum at sites of viral RNA synthesis. J. Virol. 1996;70:8908–8916. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.8908-8916.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rouleau M, Bancroft JB, Mackie GA. Partial purification and characterization of foxtail mosaic potexvirus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Virology. 1993;197:695–703. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Der Heijden MW, Carette JE, Reinhoud PJ, Haegi A, Bol JF. Alfalfa mosaic virus replicase proteins P1 and P2 interact and colocalize at the vacuolar membrane. J. Virol. 2001;75:1879–1887. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.4.1879-1887.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mas P, Beachy RN. Replication of tobacco mosaic virus on endoplasmic reticulum and role of the cytoskeleton and virus movement protein in intracellular distribution of viral RNA. J. Cell Biol. 1999;147:945–958. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.5.945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reichel C, Beachy RN. Tobacco mosaic virus infection induces severe morphological changes of the endoplasmic reticulum. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:11169–11174. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cairns HJF. The initiation of vaccinia infection. Virology. 1960;11:603–623. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(60)90103-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kit S, Dubbs DR, Hsu TC. Biochemistry of vaccinia-infected mouse fibroblasts (strain L-M). III. Radioautographic and biochemical studies of thymidine-3H uptake into DNA of L-M cells and rabbit cells in primary culture. Virology. 1963;19:13–22. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(63)90019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tolonen N, Doglio L, Schleich S, Krijnse-Locker J. Vaccinia virus DNA-replication occurs in ER-enclosed cytoplasmic mini-nuclei. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2001;12:2031–2046. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.7.2031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kujala P, et al. Intracellular distribution of rubella virus nonstructural protein P150. J. Virol. 1999;73:7805–7811. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.9.7805-7811.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kujala P, et al. Biogenesis of the Semliki Forest virus RNA replication complex. J. Virol. 2001;75:3873–3884. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.8.3873-3884.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee JY, Marshall JA, Bowden DS. Characterization of rubella virus replication complexes using antibodies to double-stranded RNA. Virology. 1994;200:307–312. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Magliano D, et al. Rubella virus replication complexes are virus-modified lysosomes. Virology. 1998;240:57–63. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Froshauer S, Kartenbeck J, Helenius A. Alphavirus RNA replicase is located on the cytoplasmic surface of endosomes and lysosomes. J. Cell Biol. 1988;107:2075–2086. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.6.2075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grimley PM, Berezesky IK, Friedman RM. Cytoplasmic structures associated with an arbovirus infection: loci of viral ribonucleic acid synthesis. J. Virol. 1968;2:1326–1338. doi: 10.1128/jvi.2.11.1326-1338.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grimley PM, Levin JG, Berezesky IK, Friedman RM. Specific membranous structures associated with the replication of group A arboviruses. J. Virol. 1972;10:492–503. doi: 10.1128/jvi.10.3.492-503.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miller DJ, Schwartz MD, Ahlquist P. Flock house virus RNA replicates on outer mitochondrial membranes in Drosophila cells. J. Virol. 2001;75:11664–11676. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.23.11664-11676.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McCartney AW, Greenwood JS, Fabian MR, White KA, Mullen RT. Localization of the tomato bushy stunt virus replication protein p33 reveals a peroxisome-to-endoplasmic reticulum sorting pathway. Plant Cell. 2005;17:3513–3531. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.036350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jonczyk M, Pathak KB, Sharma M, Nagy PD. Exploiting alternative subcellular location for replication: tombusvirus replication switches to the endoplasmic reticulum in the absence of peroxisomes. Virology. 2007;362:320–330. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barco A, Carrasco L. A human virus protein, poliovirus protein 2BC, induces membrane proliferation and blocks the exocytic pathway in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 1995;14:3349–3364. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07341.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cho MW, Teterina N, Egger D, Bienz K, Ehrenfeld E. Membrane rearrangement and vesicle induction by recombinant poliovirus 2C and 2BC in human cells. Virology. 1994;202:129–145. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Suhy DA, Giddings TH, Jr, Kirkegaard K. Remodeling the endoplasmic reticulum by poliovirus infection and by individual viral proteins: an autophagy-like origin for virus-induced vesicles. J. Virol. 2000;74:8953–8965. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.19.8953-8965.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mackenzie JM, Khromykh AA, Jones MK, Westaway EG. Subcellular localization and some biochemical properties of the flavivirus Kunjin nonstructural proteins NS2A and NS4A. Virology. 1998;245:203–215. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miller S, Kastner S, Krijnse-Locker J, Buhler S, Bartenschlager R. The non-structural protein 4A of dengue virus is an integral membrane protein inducing membrane alterations in a 2K-regulated manner. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:8873–8882. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609919200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roosendaal J, Westaway EG, Khromykh A, Mackenzie JM. Regulated cleavages at the West Nile virus NS4A-2K-NS4B junctions play a major role in rearranging cytoplasmic membranes and Golgi trafficking of the NS4A protein. J. Virol. 2006;80:4623–4632. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.9.4623-4632.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Snijder EJ, van Tol H, Roos N, Pedersen KW. Non-structural proteins 2 and 3 interact to modify host cell membranes during the formation of the arterivirus replication complex. J. Gen. Virol. 2001;82:985–994. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-82-5-985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rust RC, et al. Cellular COPII proteins are involved in production of the vesicles that form the poliovirus replication complex. J. Virol. 2001;75:9808–9818. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.20.9808-9818.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.D'Souza-Schorey C, Chavrier P. ARF proteins: roles in membrane traffic and beyond. Nature Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;7:347–358. doi: 10.1038/nrm1910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Belov GA, et al. Hijacking components of the cellular secretory pathway for replication of poliovirus RNA. J. Virol. 2007;81:558–567. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01820-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Belov GA, Fogg MH, Ehrenfeld E. Poliovirus proteins induce membrane association of GTPase ADP-ribosylation factor. J. Virol. 2005;79:7207–7216. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.11.7207-7216.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Belov GA, Ehrenfeld E. Involvement of cellular membrane traffic proteins in poliovirus replication. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:36–38. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.1.3683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wessels E, et al. A viral protein that blocks Arf1-mediated COP-I assembly by inhibiting the guanine nucleotide exchange factor GBF1. Dev. Cell. 2006;11:191–201. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Deitz SB, Dodd DA, Cooper S, Parham P, Kirkegaard K. MHC I-dependent antigen presentation is inhibited by poliovirus protein 3A. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:13790–13795. doi: 10.1073/pnas.250483097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dodd DA, Giddings TH, Jr, Kirkegaard K. Poliovirus 3A protein limits interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-8, and beta interferon secretion during viral infection. J. Virol. 2001;75:8158–8165. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.17.8158-8165.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Doedens JR, Giddings TH, Jr, Kirkegaard K. Inhibition of endoplasmic reticulum-to-Golgi traffic by poliovirus protein 3A: genetic and ultrastructural analysis. J. Virol. 1997;71:9054–9064. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9054-9064.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Doedens JR, Kirkegaard K. Inhibition of cellular protein secretion by poliovirus proteins 2B and 3A. EMBO J. 1995;14:894–907. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07071.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cuconati A, Molla A, Wimmer E. Brefeldin A inhibits cell-free, de novo synthesis of poliovirus. J. Virol. 1998;72:6456–6464. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.8.6456-6464.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Doedens J, Maynell LA, Klymkowsky MW, Kirkegaard K. Secretory pathway function, but not cytoskeletal integrity, is required in poliovirus infection. Arch. Virol. Suppl. 1994;9:159–172. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-9326-6_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gazina EV, Mackenzie JM, Gorrell RJ, Anderson DA. Differential requirements for COPI coats in formation of replication complexes among three genera of Picornaviridae. J. Virol. 2002;76:11113–11122. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.21.11113-11122.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Maynell LA, Kirkegaard K, Klymkowsky MW. Inhibition of poliovirus RNA synthesis by brefeldin A. J. Virol. 1992;66:1985–1994. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.4.1985-1994.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hamamoto I, et al. Human VAP-B is involved in hepatitis C virus replication through interaction with NS5A and NS5B. J. Virol. 2005;79:13473–13482. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.21.13473-13482.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Foster LJ, et al. A functional role for VAP-33 in insulin-stimulated GLUT4 traffic. Traffic. 2000;1:512–521. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2000.010609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lapierre LA, Tuma PL, Navarre J, Goldenring JR, Anderson JM. VAP-33 localizes to both an intracellular vesicle population and with occludin at the tight junction. J. Cell Sci. 1999;112:3723–3732. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.21.3723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nishimura Y, Hayashi M, Inada H, Tanaka T. Molecular cloning and characterization of mammalian homologues of vesicle-associated membrane protein-associated (VAMP-associated) proteins. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999;254:21–26. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schoch S, et al. SNARE function analyzed in synaptobrevin/VAMP knockout mice. Science. 2001;294:1117–1122. doi: 10.1126/science.1064335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Skehel PA, Fabian-Fine R, Kandel ER. Mouse VAP33 is associated with the endoplasmic reticulum and microtubules. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:1101–1106. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Skehel PA, Martin KC, Kandel ER, Bartsch D. A VAMP-binding protein from Aplysia required for neurotransmitter release. Science. 1995;269:1580–1583. doi: 10.1126/science.7667638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Girod A, et al. Evidence for a COP-I-independent transport route from the Golgi complex to the endoplasmic reticulum. Nature Cell Biol. 1999;1:423–430. doi: 10.1038/15658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Soussan L, et al. ERG30, a VAP-33-related protein, functions in protein transport mediated by COPI vesicles. J. Cell Biol. 1999;146:301–311. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.2.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gao L, Aizaki H, He JW, Lai MM. Interactions between viral nonstructural proteins and host protein hVAP-33 mediate the formation of hepatitis C virus RNA replication complex on lipid raft. J. Virol. 2004;78:3480–3488. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.7.3480-3488.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Amarilio R, Ramachandran S, Sabanay H, Lev S. Differential regulation of endoplasmic reticulum structure through VAP–Nir protein interaction. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:5934–5944. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409566200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lev S. The role of the Nir/rdgB protein family in membrane trafficking and cytoskeleton remodeling. Exp. Cell Res. 2004;297:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Moriishi K, Matsuura Y. Host factors involved in the replication of hepatitis C virus. Rev. Med. Virol. 2007;17:343–354. doi: 10.1002/rmv.542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schramm B, Krijnse-Locker J. Cytoplasmic organization of POXvirus DNA-replication. Traffic. 2005;6:839–846. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2005.00324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Antonny B. Membrane deformation by protein coats. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2006;18:386–394. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.McMahon HT, Gallop JL. Membrane curvature and mechanisms of dynamic cell membrane remodelling. Nature. 2005;438:590–596. doi: 10.1038/nature04396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zimmerberg J, Kozlov MM. How proteins produce cellular membrane curvature. Nature Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;7:9–19. doi: 10.1038/nrm1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bielli A, et al. Regulation of Sar1 NH2 terminus by GTP binding and hydrolysis promotes membrane deformation to control COPII vesicle fission. J. Cell Biol. 2005;171:919–924. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200509095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lee MC, et al. Sar1p N-terminal helix initiates membrane curvature and completes the fission of a COPII vesicle. Cell. 2005;122:605–617. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Brass V, et al. An amino-terminal amphipathic α-helix mediates membrane association of the hepatitis C virus nonstructural protein 5A. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:8130–8139. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111289200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Brass V, et al. Conserved determinants for membrane association of nonstructural protein 5A from hepatitis C virus and related viruses. J. Virol. 2007;81:2745–2757. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01279-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Elazar M, Liu P, Rice CM, Glenn JS. An N-terminal amphipathic helix in hepatitis C virus (HCV) NS4B mediates membrane association, correct localization of replication complex proteins, and HCV RNA replication. J. Virol. 2004;78:11393–11400. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.20.11393-11400.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sapay N, et al. NMR structure and molecular dynamics of the in-plane membrane anchor of nonstructural protein 5A from bovine viral diarrhea virus. Biochemistry. 2006;45:2221–2233. doi: 10.1021/bi0517685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Spuul P, et al. Role of the amphipathic peptide of Semliki forest virus replicase protein nsP1 in membrane association and virus replication. J. Virol. 2007;81:872–883. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01785-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Teterina NL, et al. Testing the modularity of the N-terminal amphipathic helix conserved in picornavirus 2C proteins and hepatitis C NS5A protein. Virology. 2006;344:453–467. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.08.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lundin M. Topology and Membrane Rearrangements of the Hepatitis C Virus Protein NS4B. 2006. pp. 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yu GY, Lee KJ, Gao L, Lai MM. Palmitoylation and polymerization of hepatitis C virus NS4B protein. J. Virol. 2006;80:6013–6023. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00053-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Strauss DM, Glustrom LW, Wuttke DS. Towards an understanding of the poliovirus replication complex: the solution structure of the soluble domain of the poliovirus 3A protein. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;330:225–234. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(03)00577-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.van Kuppeveld FJ, Galama JM, Zoll J, van den Hurk PJ, Melchers WJ. Coxsackie B3 virus protein 2B contains cationic amphipathic helix that is required for viral RNA replication. J. Virol. 1996;70:3876–3886. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.3876-3886.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]