Key Points

Crosstalk between pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) expressed by dendritic cells orchestrates T helper (TH) cell differentiation through the induction of specific cytokine expression profiles, tailored to invading pathogens. C-type lectin receptors (CLRs) have an important role in orchestrating the induction of signalling pathways that regulate adaptive immune responses.

CLRs can control adaptive immunity at various levels by inducing signalling on their own, through crosstalk with other PRRs or by inducing carbohydrate-specific signalling pathways.

DC-specific ICAM3-grabbing non-integrin (DC-SIGN) interacts with mannose-carrying pathogens including Mycobacterium tuberculosis, HIV-1, measles virus and Candida albicans to activate the serine/threonine protein kinase RAF1. RAF1 signalling leads to the acetylation of Toll-like receptor (TLR)-activated nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) subunit p65 and affects cytokine expression, such as inducing the upregulation of interleukin-10 (IL-10).

DC-associated C-type lectin 1 (dectin 1) triggering by a broad range of fungal pathogens, such as C. albicans, Aspergillus fumigatus and Pneumocystis carinii, results in protective antifungal immunity through the crosstalk of two independent signalling pathways — one through spleen tyrosine kinase (SYK) and one through RAF1 — that are essential for the expression of TH1 and TH17 cell polarizing cytokines.

Crosstalk between the SYK and RAF1 pathways is both synergistic and antagonizing to fine-tune NF-κB activity: although Ser276 phosphorylation of p65 leads to enhanced transcriptional activity of p65 itself through acetylation, it also inhibits the transcriptional activity of the NF-κB subunit RELB by sequestering it in p65–RELB dimers, which are transcriptionally inactive.

The diversity in CLR-mediated signalling provides some major challenges for the researches to elucidate and manipulate the signalling properties of this exciting family of receptors. However, the recent advances strongly support the use of CLR targeting vaccination strategies using dendritic cells to induce or redirect adaptive immune responses as well as improve antigen delivery.

Here, Teunis Geijtenbeek and Sonja Gringhuis discuss the role of the signalling pathways induced by C-type lectin receptors in determining T helper cell lineage commitment and describe how these pathways can be exploited for the development of new vaccination strategies.

Abstract

C-type lectin receptors (CLRs) expressed by dendritic cells are crucial for tailoring immune responses to pathogens. Following pathogen binding, CLRs trigger distinct signalling pathways that induce the expression of specific cytokines which determine T cell polarization fates. Some CLRs can induce signalling pathways that directly activate nuclear factor-κB, whereas other CLRs affect signalling by Toll-like receptors. Dissecting these signalling pathways and their effects on host immune cells is essential to understand the molecular mechanisms involved in the induction of adaptive immune responses. In this Review we describe the role of CLR signalling in regulating adaptive immunity and immunopathogenesis and discuss how this knowledge can be harnessed for the development of innovative vaccination approaches.

Main

Dendritic cells (DCs) are located throughout the body to capture and internalize invading pathogens, and subsequently process and present antigen on MHC class I and class II molecules to CD8+ and CD4+ T cells, respectively1. Antigen presentation by DCs is in itself not sufficient to induce effective T cell responses against pathogens. CD4+ T cells need to differentiate into distinct T helper (TH) cell subsets depending on the type of infection; TH1 cells secrete interferon-γ (IFNγ), which activates macrophages to fight intracellular microorganisms, TH2 cells secrete interleukin-4 (IL-4), IL-5 and IL-13 to induce humoral immune responses against helminths, and IL-17-secreting TH17 cells mobilize phagocytes to clear extracellular fungi and bacteria1. Furthermore, regulatory T cells are needed to control the activity of effector TH cells. Thus, DCs need to translate information about the invading pathogen into a cytokine gene expression profile that directs the correct TH cell differentiation pathway.

Pathogen recognition is central to the induction of T cell differentiation. Although the variety of pathogens is immense, groups of pathogens share similar structures known as pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), which enable their recognition2. DCs express numerous pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) that interact with PAMPs to induce cytokine expression. PRRs include the archetypical Toll-like receptors (TLRs), as well as non-TLRs such as intracellular nucleotide-binding domain and leucine-rich-repeat-containing family (NLRs), retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I)-like receptors and C-type lectin receptors (CLRs)2. Triggering of several PRRs simultaneously can induce diverse innate immune responses, which provides the diversity that is required to shape an effective adaptive immune response. Distinct pathogens express different PAMPs, and the combination of these PAMPs functions as a fingerprint that triggers a specific set of PRRs, leading to the integration of signalling pathways to tailor the immune response to that specific pathogen.

Recent studies have identified CLRs as an important family of PRRs that are involved in the induction of specific gene expression profiles to specific pathogens, either by modulating TLR signalling or by directly inducing gene expression3,4,5,6. In this Review we discuss the recently published literature describing the innate signalling pathways induced by CLRs and describe how these pathways can be used in vaccine development to tailor specific immune responses for the treatment of not only infectious diseases but also cancer and immunological diseases such as allergy and autoimmunity.

CLRs as signalling receptors

The term C-type lectin was introduced to distinguish between Ca2+-dependent and Ca2+-independent carbohydrate-binding lectins. CLRs share at least one carbohydrate recognition domain, which is a compact structural module that contains conserved residue motifs and determines the carbohydrate specificity of the CLR7. The CLR family now includes proteins that have one or more domains that are homologous to carbohydrate recognition domains but do not always bind carbohydrate structures7. CLRs exist both as soluble and transmembrane proteins. In this Review we discuss the transmembrane CLRs that function as PRRs. These CLRs can be divided into two groups: group I CLRs belong to the mannose receptor family and group II CLRs belong to the asialoglycoprotein receptor family and include the DC-associated C-type lectin 1 (dectin 1; also known as CLEC7A) and DC immunoreceptor (DCIR; also known as CLEC4A) subfamilies (Table 1).

Table 1.

C-type lectin receptors, pathogen recognition and signalling

| CLR* | Expression | Glycan PAMPs | Pathogenic (exogenous) ligands | Signalling motif or adaptor | Signalling proteins involved | Immunological outcome | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group II CLRs (asialoglycoprotein receptor family) | |||||||

| DC-SIGN (CD209) | Myeloid DCs | High mannose and fucose (LeX, LeY, LeA, LeB) |

˙ Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Mycobacterium leprae, BCG, Lactobacilli spp. and Helicobacter pylori ˙ HIV-1, measles virus, dengue virus, SARS coronavirus and filoviruses ˙ Candida albicans ˙ Leishmania spp. ˙ Tick Ixodes scapularis saliva protein Salp15, peanut allergen Ara h1 and Schistosoma mansoni soluble egg antigens |

None | LSP1, LARG, RhoA, Ras proteins, RAF1, Src kinases and PAKs |

˙ Upregulation of TLR-induced IL-10 production ˙ Induction of TH1, TH2, TH17 and regulatory T cell differentiation‡ ˙ Inhibition of TH1 cell differentiation‡ ˙ Induction of regulatory T cells‡ ˙ Antigen presentation |

3,20,22,26,29,68,85–93 |

| Langerin (CLEC4K, CD207) | Langerhans cells and dermal DC subset | High mannose, fucose (LeY, LeB) and GlcNAc |

˙ M. leprae ˙ HIV-1 |

Putative proline-rich domain | ND |

˙ M. leprae endocytosis and antigen presentation ˙ HIV-1 internalization and degradation |

84,94,95 |

| MGL (CLEC10A, CD301) | Myeloid DCs and macrophages | Terminal GalNAc (Tn antigen, LDN) |

˙ Filoviruses ˙ S. mansoni |

None | ND | ND | 96 |

| CLEC5A (MDL1) | Monocytes and macrophages | ND | Dengue virus | DAP10 and DAP12 | ND | Induction of TNF production | 13,69,97 |

| Group II CLRs (asialoglycoprotein receptor family; dectin 1 subfamily) | |||||||

| Dectin 1 (CLEC7A) | Myeloid DCs, monocytes, macrophages and B cells | β-1,3-glucan |

˙ M. tuberculosis and Mycobacterium abscessus ˙ C. albicans, Aspergillus fumigatus, Pneumocystis carinii, Penicillium marneffei, Coccidioides posadasii and Histoplasma capsulatum |

YxxL§ | SYK, PLCγ2, CARD9, BCL-10, MALT1, NIK and RAF1 |

˙ Induction of TH1 and TH17 cell differentiation through induction of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12 and IL-23 production ˙ Induction of TNF and CXCL2 production ˙ Phagocytosis ˙ LTB4 synthesis |

4,5,17,42,43,59,65,98 |

| MICL (CLEC12A, DCAL2) | Myeloid DCs, monocytes, macrophages and neutrophils | ND | ND | ITIM | SHP1, SHP2 and ERK | Inhibition of TLR4-induced IL-12 production | 14,16 |

| CLEC2 (CLEC1B) | Platelets | ND |

˙ HIV-1 ˙ Snake venom protein rhodocytin |

YxxL§ | SYK, LAT, RAC1 and PLCγ2 | ND | 99–101 |

| DNGR1 (CLEC9A) | BDCA3+ DCs, monocytes and B cells | ND | ND | YxxL§ | SYK |

˙ Induction of TNF production ˙ Antigen cross-presentation |

78,82,102 |

| CLEC12B | Macrophages | ND | ND | ITIM | SHP1 and SHP2 | ND | 103 |

| Group II CLRs (asialoglycoprotein receptor family; DCIR subfamily) | |||||||

| Dectin 2 (CLEC6A) | Myeloid DCs, pDCs, monocytes, macrophages, B cells and neutrophils | High mannose |

˙ M. tuberculosis ˙ C. albicans, Trichophyton rubrum, A. fumigatus, Microsporum audouinii and Paracoccoides brasiliensis ˙ House dust mite Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus allergens |

FcRγ | Src kinases and SYK |

˙ Induction of TNF and IL-6 production ˙ Cysteinyl leukotriene synthesis |

10,58 |

| BDCA2 (CLEC4C, CD303) | pDCs, monocytes, macrophages and neutrophils | ND | ND | FcRγ | SYK, BTK, BLNK and PLCγ2 |

˙ Inhibition of TLR9-induced type I IFN, TNF and IL-6 production ˙ Upregulation of TLR9-induced IL-10 production |

11,31,33 |

| Mincle (CLEC4E) | Myeloid DCs, monocytes and macrophages | α-mannose | Malassezia spp. | FcRγ | SYK and CARD9 | ˙ Induction of TNF, IL-10 and CXCL2 production | 12,18 |

| DCIR (CLEC4A) | Myeloid DCs, pDCs, monocytes, macrophages, B cells and neutrophils | ND | HIV-1 | ITIM | SHP1 and SHP2 |

˙ Inhibition of TLR8-induced TNF and IL-12 production ˙ Inhibition of TLR9-induced TNF and IFNα production |

6,15,38 |

| Group I CLRs (mannose receptor family) | |||||||

| Mannose receptor (CD206) | Myeloid DCs and macrophages | High mannose, fucose and sulphated sugars (sLex) |

˙ M. tuberculosis, Mycobacterium kansasii, Francisella tularensis, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Streptococcus pneumoniae ˙ HIV-1 and dengue virus ˙ C. albicans, Cryptococcus neoformans and P. carinii ˙ Leishmania spp. |

ND | CDC42, RhoB, PAKs and ROCK1 | Phagocytosis and antigen presentation | 104–106 |

| DEC205 (LY75, CD205) | Myeloid DCs | ND | ND | ND | ND | Endocytosis and antigen presentation | 76 |

| *Alternative names are provided in brackets. | |||||||

| ‡Effect on T cell differentiation is ligand dependent. | |||||||

| §In this motif, x denotes any amino acid. BCG, Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette–Guérin; BCL-10, B cell lymphoma 10; BDCA, blood dendritic cell antigen protein; BLNK, B cell linker; BTK, Bruton's tyrosine kinase; CARD9; caspase-recruitment domain family, member 9; CDC42, cyclin-dependent kinase 42; CLEC, C-type lectin domain family member; CLR, C-type lectin receptor; CXCL2, CXC-chemokine ligand 2; DC, dendritic cell; DCIR, DC immunoreceptor; DC-SIGN, DC-specific ICAM3-grabbing non-integrin; dectin, DC-associated C-type lectin; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; FcRγ, Fc receptor γ-chain; GalNAc, N-acetylgalactosamine; GlcNAc, β1,6-N-acetylglucosamine; IL, interleukin; ITIM, immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif; LARG, leukaemia-associated Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor; LAT, linker for activation of T cells; LSP1, lymphocyte-specific 1; LTB4, leukotriene B4; MALT1, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma translocation gene; MICL, C-type lectin-like receptor; mincle, macrophage-inducible C-type lectin; ND, not determined; NIK, nuclear factor-κB-inducing kinase; PAK, p21-activated kinase; PAMP, pathogen-associated molecular pattern; pDC, plasmacytoid DC; PLCγ2; phospholipase Cγ2; RHO, Ras homologue; ROCK1, Rho-associated coiled-coil-containing protein kinase 1; SARS, severe acute respiratory syndrome; SHP, SH2-domain-containing protein tyrosine phosphatase; sLe, sialyl Lewis; SYK, spleen tyrosine kinase; TLR, Toll-like receptor; TH, T helper; TNF, tumour necrosis factor. | |||||||

CLRs expressed by DCs interact with pathogens primarily through the recognition of mannose, fucose and glucan carbohydrate structures. Together, these CLRs recognize most classes of human pathogens; mannose specificity allows the recognition of viruses, fungi and mycobacteria, fucose structures are more specifically expressed by certain bacteria and helminths and glucan structures are present on mycobacteria and fungi8,9. Recognition by CLRs leads to the internalization of the pathogen, its degradation and subsequent antigen presentation9 (Box 1). These properties are important for vaccine design1. However, an even more powerful application has remained largely unexplored: targeting of the signalling pathways downstream of CLRs to tailor immune responses to break tumour-induced immunosuppression, to induce TH1-type responses against virus infections or to redirect allergic TH2 cell responses to protective TH1 cell responses.

CLR triggering by different pathogens can induce diverse immune responses (Table 1). The underlying signalling processes are complex and depend on crosstalk with other PRRs, the ligand- or carbohydrate-specific signalling pathway and the DC subset. Recent studies suggest that there are two general ways by which CLRs induce signalling pathways. CLRs, such as macrophage-inducible C-type lectin (mincle; also known as CLEC4E), dectin 2 (also known as CLEC6A), blood DC antigen 2 protein (BDCA2; also known as CLEC4C) and C-type lectin domain family 5, member A (CLEC5A), are associated with and induce signalling pathways through immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM)-containing adaptor molecules, such as Fc receptor γ-chain (FcRγ) or DAP12 (Refs 10–13). Other CLRs, such as dectin 1, DC-specific ICAM3-grabbing non-integrin (DC-SIGN; also known as CD209), DCIR and myeloid C-type lectin-like receptor (MICL; also known as CLEC12A) induce signalling pathways through the activation of protein kinases or phosphatases that either directly or indirectly interact with their cytoplasmic domains3,5,14,15. Several CLRs, such as DC-SIGN, BDCA2, DCIR and MICL, induce signalling pathways that modulate TLR-induced gene expression at the transcriptional or post-transcriptional level. However, to date these receptors have not been shown to induce gene expression in the absence of other PRR signalling3,6,11,16. By contrast, other CLRs, such as dectin 1, dectin 2 and mincle, induce gene expression following carbohydrate recognition independently of other PRRs5,10,17,18. The transcription factor nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) is a key mediator of inducible gene expression in the immune system, although many other transcription factors have an equally essential role. Indeed, the activation of the transcription factors activator protein 1 and members of the IFN regulatory factor family by diverse PRRs provides flexibility and variability to the regulation of cytokine gene expression, which is needed to combat different pathogens2,19. CLR-induced signal transduction seems to mainly activate or modulate NF-κB functions, and the regulation of other transcription factors by CLRs has received little attention to date. In the following sections we first discuss the signalling pathways induced by CLRs that modulate TLR-induced gene expression and then describe the mechanisms used by CLRs to induce gene expression by themselves.

CLR and TLR signalling crosstalk

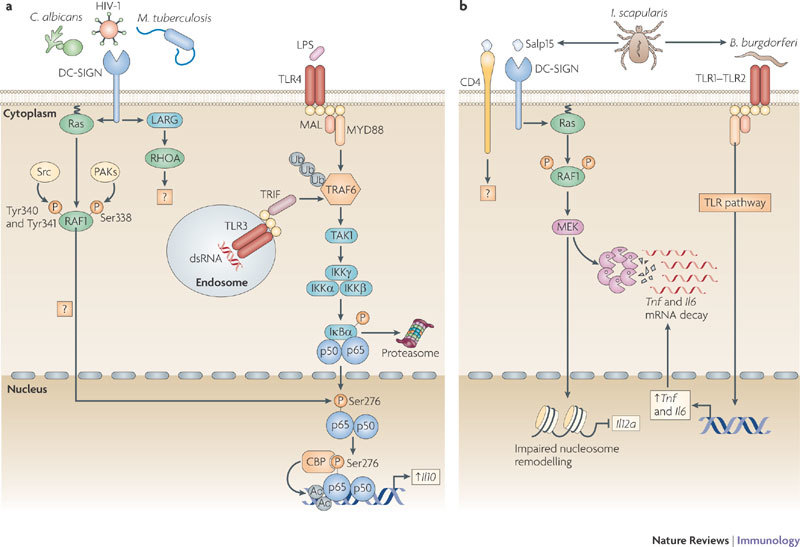

DC-SIGN signalling. DC-SIGN interacts with a wide range of pathogens through mannose and fucose recognition (Table 1), and recent studies have shed more light on its signalling properties (Fig. 1). The interaction of DC-SIGN with mannose-containing pathogens, such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Mycobacterium leprae, HIV-1, measles virus and Candida albicans, affects TLR4-mediated immune responses by DCs3,20. The crosstalk between TLR4 and DC-SIGN depends on the prior activation of NF-κB by TLR signalling and is therefore not limited to TLR4, but also includes triggering of other NF-κB-inducing PRRs, such as TLR3 and TLR5 (Ref. 3). DC-SIGN triggering activates the serine/threonine protein kinase RAF1, which induces the phosphorylation of the NF-κB subunit p65 at Ser276 (Ref. 3). The activation of RAF1 by DC-SIGN does not depend on TLR signalling3 and involves a complex sequence of events, including its release from autoinhibition, dephosphorylation, transformational changes and finally phosphorylation to activate its kinase activity21. Specifically, DC-SIGN triggering activates the small GTPase Ras proteins, which is the first essential step in RAF1 activation. Subsequent binding of GTP–Ras to RAF1 leads to the phosphorylation of RAF1 at residues Ser338, Tyr340 and Tyr341 (Ref. 3). Phosphorylation of RAF1 at Ser338 is mediated by p21-activated kinases (PAKs), which in turn are activated by members of the Rho family of small GTPases, and phosphorylation at Tyr340 and Tyr341 is mediated by Src kinases3,21. However, it is unknown how DC-SIGN triggering results in the activation of these downstream effector kinases. Recently, it was shown that DC-SIGN triggering by HIV-1 or the activating antibody H200 induces the activation of leukaemia-associated Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor (LARG), which is essential for the formation of the infectious synapse between DCs and T cells that facilitates HIV-1 transmission22. LARG is recruited to DC-SIGN after stimulation, which leads to the recruitment and activation of the small GTPase RHOA22; LARG and RHOA might be involved in the activation of the upstream effectors of RAF1.

Figure 1. DC-SIGN signalling modulates TLR signalling through RAF1-dependent acetylation of p65.

a | DC-specific ICAM3-grabbing non-integrin (DC-SIGN) binding to pathogens such as HIV-1, Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Candida albicans activates the small GTPase Ras proteins, which associate with the serine/threonine protein kinase RAF1 to allow its phosphorylation at residues Ser338, and Tyr340 and Tyr341 by p21-activated kinases (PAKs) and Src kinases, respectively. The upstream effectors that activate PAKs and Src kinases are unknown but might involve leukaemia-associated Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor (LARG) and Ras homologue A (RHOA), as these proteins are activated by HIV-1 binding to DC-SIGN. RAF1 activation leads to modulation of Toll-like receptor (TLR)-induced nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) activation. TLR3 and TLR4 activation by double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS), respectively, leads to the recruitment of the ubiquitin ligase TNF receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6) by myeloid differentiation primary response protein 88 (MYD88), TIR-domain-containing adaptor protein inducing IFNβ (TRIF) and other factors (not depicted). Self-induced polyubiquitylation (Ub) of TRAF6 mediates the recruitment of TGFβ-activating kinase 1 (TAK1), which activates the IκB kinase (IKK) complex. IKKβ phosphorylates inhibitor of NF-κBα (IκBα), thereby targeting it for proteasomal degradation and releasing NF-κB from inhibition, which then translocates into the nucleus, where it binds to NF-κB sites in the enhancer and promoter regions of target genes. RAF1 induces the phosphorylation of p65 at Ser276 through an unknown pathway. Phosphorylated Ser276 serves as a binding site for the histone acetyltransferases CREB-binding protein (CBP) and p300 (not depicted) to acetylate (Ac) p65 at different lysines. Acetylated p65 exhibits enhanced transcriptional activity as well as prolonged nuclear presence owing to impaired binding by IκB, which increases the rate of Il10 (interleukin-10) transcription and prolongs the binding of NF-κB to the Il10 promoter, thereby increasing the production of IL-10. b | Binding of the salivary protein Salp15 from the tick Ixodes scapularis to DC-SIGN activates RAF1, but co-ligation with another receptor, presumably CD4, changes downstream effectors of RAF1, leading to MEK (MAPK/ERK kinase) but not ERK (extracellular signal-regulated kinase) activation. The spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi exploits the effects of Salp15 to infect humans. Salp15-induced MEK-dependent signalling decreases B. burgdorferi-induced TLR1–TLR2-dependent pro-inflammatory cytokine production by enhancing the decay of Il6 and Tnf (tumour necrosis factor) mRNA while impairing nucleosome remodelling at the Il12a promoter, which is required for transcriptional initiation. MAL, MYD88-adaptor-like protein.

The phosphorylation of the NF-κB subunit p65 at Ser276 by RAF1 enables binding of the histone acetyltransferases CREB-binding protein (CBP) and p300 to p65, which leads to the acetylation of p65 on several lysine residues3,23. Acetylation affects the activity of p65 by increasing its DNA binding affinity, prolonging its nuclear activity and enhancing transcriptional rate24. In particular, the acetylation of p65 mediated by DC-SIGN increases and prolongs transcriptional activation from the Il8 and Il10 promoter3. In addition to this, RAF1-mediated acetylation of p65 by DC-SIGN might also increase the transcription of other cytokine genes such as Il6 and Il12b (see below), as shown for dectin 1 (Ref. 4); therefore, acetylation of p65 by DC-SIGN signalling has a central role in the immune responses induced by various mannose-containing pathogens.

The signalling route downstream of RAF1 leading to p65 phosphorylation remains to be fully defined. RAF1 is a well-known component of the classical RAF1–MEK–ERK (RAF1–MAPK/ERK kinase–extracellular signal-regulated kinase) signalling cascade21, but ERK activation is not observed after binding of mannose-containing pathogens by DC-SIGN3. By contrast, the DC-SIGN specific antibody MR1 has been shown to induce ERK activation25, although it is not clear whether this reflects what occurs in the presence of an actual pathogen. Stimulation of DCs with the DC-SIGN ligand Ara h1, which is the major peanut allergen, or Schistosoma mansoni soluble egg antigens induces ERK activation, although a role for DC-SIGN triggering was not formally established in these studies26,27. Similarly, binding of HIV-1 gp120 to DCs has been linked to ERK activation, but it was not specified whether DC-SIGN, the mannose receptor or chemokine receptors were involved in this activation28. Another ligand of DC-SIGN, the tick Ixodes scapularis saliva protein Salp15, activates RAF1, but the downstream signalling pathway it triggers differs from that induced by mannose-containing pathogens as it does not involve the acetylation of p65 (Ref. 29). RAF1 activation by Salp15 leads to MEK but not ERK activation, and this specific signalling pathway might reflect modulation of the RAF1–p65 acetylation pathway as a result of the involvement of signalling pathways induced through other receptors. Indeed, Salp15 is known to interact with receptors such as CD4 (Ref. 30), and this could result in the activation of kinases that are different to those induced by other DC-SIGN ligands. The Salp15-induced RAF1–MEK-dependent signalling pathway decreases Borrelia burgdorferi-induced TLR-dependent inflammatory cytokine production by enhancing Il6 and Tnf (tumour necrosis factor) mRNA decay and by impairing nucleosome remodelling at the Il12a promoter, which is required for transcriptional initiation29 (Fig. 1b). These studies emphasize that although advances have been made in our understanding of DC-SIGN-induced signalling pathways, more remains to be learned. Preliminary data indicate that DC-SIGN-mediated signalling is even more complex, as immune responses induced by the recognition of fucose-containing structures by DC-SIGN are independent of RAF1 activation (S.I.G., J. den Dunnen, M. Litjens, M. van der Vlist and T.B.H.G., unpublished observations). This suggests a high degree of plasticity in DC-SIGN signalling.

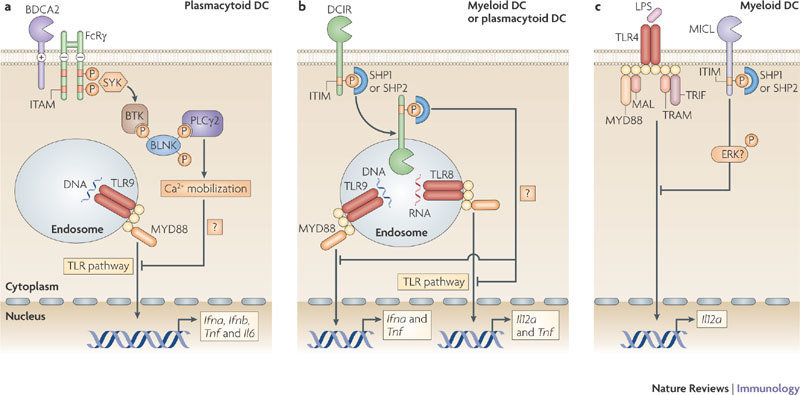

BDCA2 signalling through the ITAM-containing FcRγ. BDCA2 pairs with the ITAM-containing signalling adaptor molecule FcRγ (Fig. 2), which recruits spleen tyrosine kinase (SYK) following phosphorylation of its ITAM11,31. Although many receptors pair with FcRγ to activate NF-κB through a signalling complex involving SYK, CARD9 (caspase recruitment domain family, member 9), B cell lymphoma 10 (BCL-10) and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma translocation gene 1 (MALT1)32, BDCA2 activation by antibodies does not induce NF-κB activation or cytokine expression31,33. By contrast, BDCA2 ligation leads to calcium mobilization through the SYK-dependent activation of a signalling complex involving B cell linker (BLNK), Bruton's tyrosine kinase (BTK) and phospholipase Cγ2 (PLCγ2)11,31. Whether activation of this signalling pathway is involved in the potent suppression of TLR9-induced type I IFN (IFNα and IFNβ) production as well as TLR-induced IL-6 and TNF following BDCA2 ligation remains to be established11,31,33. Notably, tonic calcium signalling has previously been shown to inhibit TLR signalling by inducing the continuous activation of the serine phosphatase calcineurin34. Active calcineurin presumably interacts in an inhibitory manner with the TLR-adaptor protein myeloid differentiation primary response protein 88 (MYD88), thus preventing TLR signalling34. This suggests that BDCA2 activation of PLCγ2 and subsequent calcium mobilization might prevent MYD88 recruitment and thereby reduce the production of TLR-induced cytokines. Tonic calcium signalling is induced by low-avidity ligands of TREM2 (triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2), which, similarly to BDCA2, pairs with an ITAM-bearing signalling adaptor protein (DAP12) and negatively regulates TLR responses in macrophages35,36. By contrast, high-avidity ligation of ITAM-associated receptors induces transient calcium signalling and strongly activates NF-κB and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways, which synergize with TLR signalling and hence drive pro-inflammatory cytokine production37. It will be of interest to see whether natural BDCA2 ligands function as low- or high-avidity ligands and attenuate TLR signalling similarly to BDCA2-specific antibodies or whether they induce TLR-independent cytokine responses.

Figure 2. Signalling by BDCA2, DCIR and MICL antagonizes TLR signalling.

a | Activation of blood DC antigen 2 protein (BDCA2) leads to the recruitment of spleen tyrosine kinase (SYK) to the phosphorylated immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM) of the paired signalling adaptor Fc receptor γ-chain (FcRγ). SYK activation leads to the activation of a complex consisting of B cell linker (BLNK), Bruton's tyrosine kinase (BTK) and phospholipase Cγ2 (PLCγ2), which induces Ca2+ mobilization. The signalling pathway downstream of this complex is not fully known, but results in the downregulation of Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9)-induced production of interferon-α (IFNα), IFNβ, tumour necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) by plasmacytoid dendritic cells (DCs). Calcium mobilization might be involved in inhibiting the recruitment of myeloid differentiation primary response protein 88 (MYD88) and thereby reducing the production of TLR-induced cytokines. b | Activation of DC immunoreceptor (DCIR) leads to its internalization into endosomal compartments, where TLR8 and TLR9 reside. The phosphorylation of its immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif (ITIM) recruits the phosphatases SH2-domain-containing protein tyrosine phosphatase 1 (SHP1) or SHP2, which induces the activation of an unidentified signalling pathway that leads to the downregulation of TLR8-induced IL-12 and TNF production or TLR9-induced IFNα and TNF production by either myeloid or plasmacytoid DCs, respectively. c | Cross-linking of myeloid C-type lectin-like receptor (MICL) on myeloid DCs also results in the phosphorylation of its ITIM and the recruitment of SHP1 or SHP2. MICL activation has been shown to induce the activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK). However, it is not known whether ERK activation is involved in the downregulation of TLR4-induced IL-12 production. LPS, lipopolysaccharide; MAL, MYD88-adaptor-like protein; TRAM, TRIF-related adaptor molecule; TRIF, TIR-domain-containing adaptor protein inducing IFNβ.

CLR signalling through ITIMs. DCIR and MICL are the only known CLRs that contain immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motifs (ITIMs) in their cytoplasmic tails, which serve to recruit the phosphatases SH2-domain-containing protein tyrosine phosphatase 1 (SHP1) or SHP2 following ligand binding14,15 (Fig. 2). Similar to DC-SIGN, neither DCIR nor MICL have been shown to induce immune responses on their own, but instead modulate signalling pathways induced by other PRRs. The immunomodulatory effects of DCIR and MICL are distinct and depend on the identity of the other PRRs involved6,16,38. DCIR triggering by an antibody leads to internalization and trafficking of the DCIR–antibody complex into endosomal compartments, where TLR8 and TLR9 reside6,38. Activation of DCIR induces the phosphorylation of its ITIM, which recruits SHP1 or SHP2 to its cytoplasmic domain. This induces an unidentified signalling pathway that selectively inhibits TLR8-mediated IL-12 and TNF production by myeloid DCs or TLR9-induced IFNα and TNF production by plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs)6,38.

Similarly, antibody-mediated cross-linking of MICL expressed by myeloid DCs results in the phosphorylation of its ITIM and recruitment of SHP1 or SHP2 (Ref. 14). However, the downstream effectors and subsequent immune responses are unclear. Triggering of MICL is thought to lead to the activation of ERK and the suppression of TLR-induced IL-12 expression16. Although SHP1 and SHP2 have been shown to activate ERK39, it remains to be determined whether this is the pathway downstream of MICL.

So, the ITIM-bearing CLRs seem to suppress cytokine responses induced by other PRRs through the recruitment of SHPs. Both SHP1 and SHP2 have previously been reported to be negative regulators of TLR signalling40,41. Notably, although activation of SHP1 decreases the production of TLR-induced pro-inflammatory cytokines, it has also been shown to increase the production of type I IFNs induced by TLRs and the helicase RIG-I40. Activation of SHPs might allow for plasticity in the immune responses induced by DCIR and MICL, which not only depends on the DC subset but also on the PRRs involved. Although natural ligands might induce signalling pathways that differ from those induced by antibodies (used in these studies) and could lead to cytokine expression independently of simultaneous TLR activation, these studies show how CLR signalling regulates TLR signalling and thereby adaptive immune responses.

TLR-independent signalling by CLRs

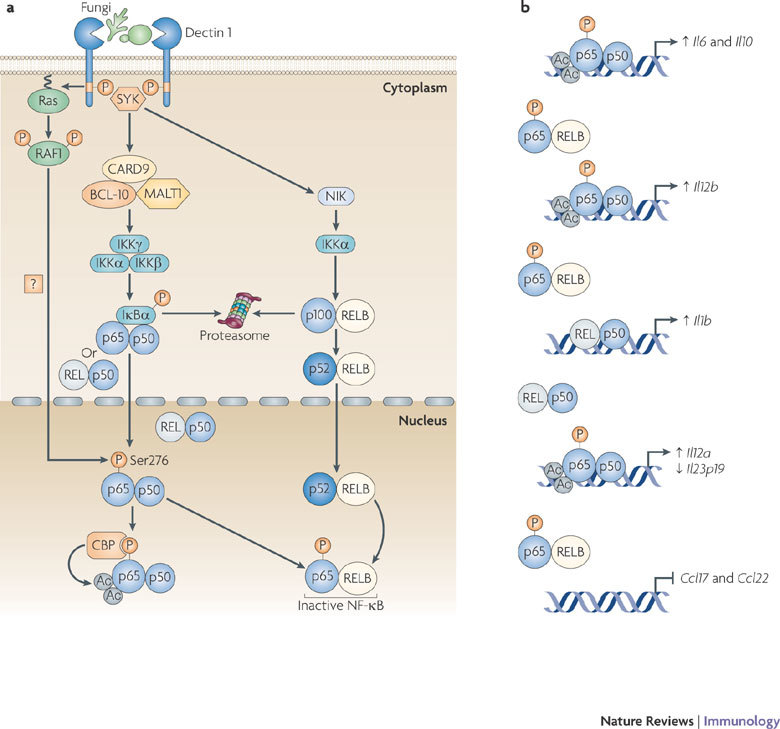

Dectin 1 signalling. Dectin 1 induces a gene expression profile independently of other PRRs. Specifically, dectin 1 activates gene expression through the recognition of β-1,3-glucan PAMPs expressed by a broad range of fungal pathogens, including C. albicans, Aspergillus fumigatus and Pneumocystis carinii, which then leads to the activation of NF-κB4,17,42,43 (Fig. 3). A role for SYK in the dectin 1-induced activation of NF-κB was established a few years ago, but the signalling pathway that links SYK with NF-κB has been revealed only recently17. Recruitment of SYK to the phosphorylated YxxL (in which x denotes any amino acid) motif in the cytoplasmic tails of two dectin 1 molecules5,44 is required for the assembly of a scaffold complex that consists of CARD9, BCL-10 and MALT1 (Ref. 17). Dectin 1-induced NF-κB activation and cytokine production by DCs from mice deficient in CARD9, BCL-10 or MALT1 is severely defective, and the survival of CARD9-deficient mice following infection with C. albicans is greatly impaired17. It remains to be established how the CARD9–BCL-10–MALT1 complex relays the activation signals for NF-κB, but it seems possible that this involves the recruitment and activation of the TNF receptor-associated factor 2 (TRAF2)–TRAF6 complex in an analogous manner to how lymphocyte antigen receptors use the CARMA1–BCL-10–MALT1 complex to activate NF-κB45. Dectin 1 triggering of the SYK–CARD9 pathway results in the activation of the NF-κB subunits p65 and REL, which are part of the the canonical NF-κB pathway4,17. Recently, it was shown that MALT1 is responsible for the specific recruitment of REL-containing NF-κB dimers to the CARMA1–BCL-10 complex following B cell receptor ligation46; it is therefore possible that MALT1 in the CARD9–BCL-10–MALT1 complex might have a similar role in REL activation by dectin 1.

Figure 3. Dectin 1 signalling through SYK and RAF1 directs NF-κB-mediated cytokine expression.

a | The binding of fungi to DC-associated C-type lectin 1 (dectin 1) induces phosphorylation of the YxxL (in which x denotes any amino acid) motif in its cytoplasmic domain. Spleen tyrosine kinase (SYK) is recruited to the two phosphorylated receptors, which leads to the formation of a complex involving CARD9 (caspase recruitment domain family, member 9), B cell lymphoma 10 (BCL-10) and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma translocation gene 1 (MALT1); this induces the activation of the IκB kinase (IKK) complex through an unknown pathway. IKKβ phosphorylates inhibitor of NF-κBα (IκBα), thereby targeting it for proteasomal degradation. This results in the release of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB; consisting of either p65–p50 or REL–p50 dimers), which then translocates into the nucleus. SYK activation also leads to the activation of the non-canonical NF-κB pathway that is mediated by NF-κB inducing kinase (NIK) and IKKα, which target p100 for proteolytic processing to p52; this subsequently leads to nuclear translocation of RELB–p52 dimers. In a SYK-independent manner, dectin 1 activation leads to the phosphorylation and activation of the serine/threonine protein kinase RAF1 by Ras proteins, which leads to the phosphorylation of p65 at Ser276. Phosphorylated Ser276 serves as a binding site for the histone acetyltransferases CREB-binding protein (CBP) or p300 (not depicted) to acetylate (Ac) p65 at different lysine residues. Ser276-phosphorylated p65 also dimerizes with RELB to form inactive dimers that cannot bind DNA, and hence attenuates the transcriptional activity of RELB. b | Binding of acetylated p65 to the Il10 (interleukin-10) enhancer and Il6 promoter increases the transcription of both genes. The RAF1-mediated formation of inactive p65–RELB dimers results in the binding of acetylated p65 to the Il12b promoter and REL–p50 to the Il1b promoter, which leads to increased IL-12p40 and IL-1β expression, respectively. The higher DNA binding affinity of acetylated p65 displaces REL–p50 dimers from the Il12a and Il23p19 promoters, which leads to increased expression of IL-12p35. However, the expression of IL-23p19 is decreased, as REL–p50 dimers are stronger transactivators of Il23p19 than p65–p50 dimers. The formation of inactive p65–RELB dimers blocks binding of RELB–p52 to the promoters of the chemokine genes Ccl17 (CC-chemokine ligand 17) and Ccl22, thereby blocking chemokine expression.

In addition to the activation of the canonical NF-κB subunits, a recent study has shown that the activation of the SYK pathway by dectin 1 leads to the induction of the non-canonical NF-κB pathway, which mediates the nuclear translocation of RELB–p52 dimers through the successive activation of NF-κB-inducing kinase (NIK) and IκB kinase-α (IKKα)4. It is unclear how SYK activation by dectin 1 results in the induction of the non-canonical NF-κB pathway. Activation of this pathway has previously been described only for a few members of the TNF receptor superfamily, such as lymphotoxin-β receptor, B cell activating factor receptor (BAFFR) and CD40, none of which signals through SYK47,48. Furthermore, the induction of nuclear RELB–p52 by lymphotoxin-β receptor, BAFFR and CD40 shows delayed kinetics compared with the activation induced by dectin 1 (Ref. 4); this suggests that dectin 1 induces an unique signalling pathway that leads to the activation of the non-canonical NF-κB pathway.

Finally, a recent study in mice has proposed a role for the SYK–CARD9-dependent pathway that is activated in response to C. albicans infection in the activation of the NLR family, pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3; also known as NALP3) inflammasome, which is required for the processing of pro-IL-1β to active IL-1β by caspase 1 through the generation of reactive oxygen species49. However, the details and relevance of this pathway require clarification, as caspase 1-deficient mice can still clear primary C. albicans infections50. Together, the data suggest that SYK activation downstream of dectin 1 activates different signalling pathways that lead to the activation of the canonical and non-canonical NF-κB pathways, as well as the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome.

In addition to SYK activation, dectin 1 induces a second signalling pathway that leads to RAF1 activation. Although RAF1 does not depend on SYK signalling for its activation, the two pathways converge at the level of NF-κB activation, as RAF1 activation leads to the phosphorylation of SYK-induced p65 at Ser276 (Ref. 4). Similarly to the crosstalk between TLR-induced p65 activation and DC-SIGN-induced RAF1 signalling, dectin 1-induced phosphorylation of p65 at Ser276 subsequently leads to acetylation and increased transcriptional activity of p65, which results in the induction of Il6, Il10, Il12a and Il12b transcription3,4. In addition, owing to its enhanced DNA binding affinity as a result of acetylation, p65 competes for binding with and replaces REL at target genes, such as Il12a and Il23p19, which results in increased IL-12p35 (encoded by Il12a) expression but reduced IL-23p19 expression4, as REL is a better transactivator of the Il23p19 promoter than p65 (Ref. 51).

The SYK- and RAF1-dependent pathways do not only synergistically activate p65, but they also fine-tune NF-κB-induced cytokine responses through a cross-regulatory mechanism between canonical and non-canonical NF-κB pathways. The phosphorylation of p65 at Ser276 by RAF1 results in the formation of p65 and RELB dimers4, which cannot bind DNA52,53. Sequestration of RELB in inactive RELB–p65 dimers has important functional consequences for adaptive immune responses, as this decreases the amount of active RELB–p52 dimers. Active RELB–p52 dimers inhibit transcription from the Il1b and Il12b promoters, thereby limiting the expression of IL-1β, IL-12 and IL-23, which are cytokines with key functions in TH cell differentiation4. Dectin 1 triggering also induces the limited expression of CC-chemokine ligand 17 (CCL17) and CCL22, which are involved in the recruitment of other leukocytes, as the expression of these chemokines depends on transcriptional activation by RELB–p52 dimers4. Dectin 1 is the only CLR known to induce the non-canonical NF-κB pathway and it is therefore probably an important control point for the induction of specific T cell responses: IL-12p40 (encoded by Il12b) is an essential subunit for bioactive IL-12 and IL-23, which are important for the development of TH1 and TH17 cell responses, respectively, whereas IL-1β is involved in TH17 cell differentiation54,55,56,57. Thus, the activation of two signalling pathways by dectin 1 allows more specific regulation of the cytokine gene transcription profile.

These new data also provide the molecular basis for the SYK-independent TLR2–dectin 1 crosstalk that had previously been observed5, as RAF1 is involved in the modulation of TLR2 and TLR4 signalling through p65 acetylation (Ref. 4). RAF1 activation by dectin 1 is independent of SYK activation and leads to the phosphorylation and subsequent acetylation of TLR-induced p65, which increases TLR-induced cytokine expression, including that of IL-6, IL-10 and IL-12p35 (Ref. 4). Moreover, the SYK pathway modulates TLR signalling by inducing the NF-κB subunits REL and RELB, which increase Il23p19 and decrease Il12b transcription, respectively4. Because RAF1 signalling counteracts RELB activation by sequestering RELB in inactive dimers, the crosstalk between the RAF1 and SYK pathways increases the production of TLR-induced IL-6, IL-10 and IL-12 (Ref. 4). Therefore, the crosstalk between TLR and dectin 1 signalling is complex and involves both the SYK and RAF1 signalling pathways, which integrate at the level of NF-κB to shape adaptive immune responses.

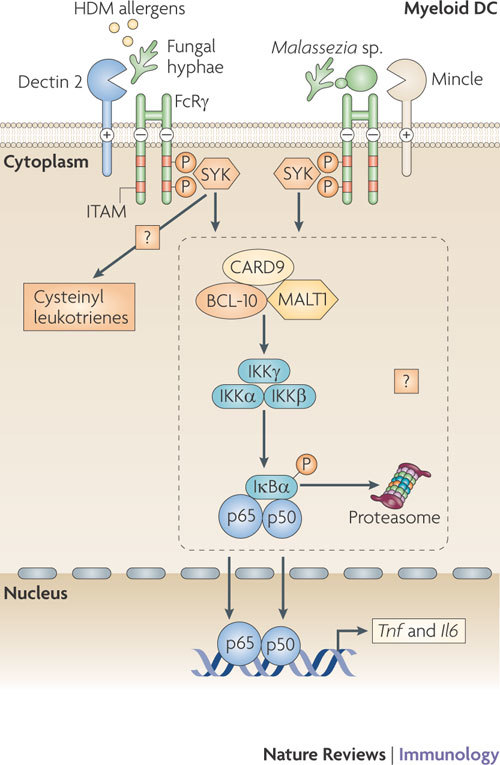

Dectin 2 and mincle signalling through FcRγ. Similarly to BDCA2, dectin 2 and mincle are known to associate non-covalently with the ITAM-bearing signalling adaptor molecule FcRγ10,11,12,31 (Fig. 4). Ligand binding to these CLRs leads to phosphorylation of the ITAM of the paired adaptor protein and the subsequent recruitment of SYK12,58. The signalling pathways downstream of SYK for dectin 2 and mincle remain largely unknown but might be similar to those downstream of other receptors that use FcRγ. FcRγ couples several receptors to NF-κB activation through a SYK–CARD–BCL-10–MALT1 complex32. Indeed, pairing of dectin 2 with FcRγ results in NF-κB activation10,58, although a role for the SYK-CARD9–BCL-10–MALT1 complex has not yet been confirmed. Thus, dectin 2 triggering alone might induce an adaptive immune response, which is supported by data showing that dectin 2 recognition of fungal hyphae from C. albicans, Trichophyton rubrum and Microsporum audouinii leads to TLR-independent production of the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF and IL-6 (Ref. 10). Furthermore, dectin 2 recognition of house dust mite allergens activates SYK through FcRγ to generate cysteinyl leukotrienes, an important mediator of allergic inflammation in the lungs58. Notably, recognition of Histoplasma capsulatum β-glucans by dectin 1 also leads to the production of leukotrienes59, suggesting that a common SYK-dependent pathway is involved in leukotriene synthesis after CLR triggering.

Figure 4. Signalling by dectin 2 and mincle leads to cytokine expression.

Both DC-associated C-type lectin 2 (dectin 2) and macrophage-inducible C-type lectin (mincle) pair with the signalling adaptor molecule Fc receptor γ-chain (FcRγ) through the presence of a positively charged amino acid residue in their transmembrane regions. The phosphorylation of the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs (ITAMs) of FcRγ following C-type lectin receptor (CLR) activation serves to recruit spleen tyrosine kinase (SYK) and induces signalling pathways that modulate cytokine expression. Dectin 2 binds to pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) expressed by fungal hyphae, and mincle binds to α-mannosyl PAMPs on Malassezia spp. fungi. Both signalling pathways lead to Toll-like receptor (TLR)-independent production of cytokines such as tumour necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukin-6 (IL-6); dectin 2 triggering is known to result in nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) p50–p65 activation, and mincle triggering induces a CARD9 (caspase recruitment domain family, member 9)-dependent signalling pathway. Similarities with the dectin 1 signalling pathway suggest that both these CLRs couple SYK activation to NF-κB activation using a complex involving CARD9, B-cell lymphoma-10 (BCL-10) and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma translocation gene 1 (MALT1). Dectin 2 binding of house dust mite (HDM) allergens activates SYK through FcRγ to generate cysteinyl leukotrienes, which are secreted and mediate allergic inflammation in lungs.

The related CLR mincle also pairs with FcRγ and induces gene transcription through the SYK–CARD9–BCL-10–MALT1 complex12. In macrophages, recognition of dead cells by mincle through the endogenous ligand SAP130 (SIN3A-associated protein, 130 kDa) mediates CXC-chemokine ligand 2 (CXCL2) and TNF production in a SYK- and CARD9-dependent manner, which induces neutrophils to migrate into damaged tissues12. Mincle also interacts with α-mannosyl PAMPs expressed by the pathogenic fungus Malassezia spp. and induces gene transcription and TNF production without the involvement of TLRs, further suggesting that mincle, similarly to dectin 2, couples FcRγ-signalling to NF-κB activation18. The similarities of mincle downstream signalling with the dectin 1 pathway suggest that both CLRs couple SYK activation to NF-κB activation through the CARD9–BCL-10–MALT1 complex.

In contrast to dectin 2 and mincle, BDCA2 does not induce TLR-independent cytokine production even though it also pairs with FcRγ. The unusual signalling pathway induced by BDCA2 might be because it is expressed only by pDCs, whereas dectin 2 and mincle are expressed by myeloid-derived antigen presenting cells (Table 1). A recent study has shown that lymphoid and myeloid cells have differential requirements for CARD proteins in BCL-10-mediated NF-κB activation32, which might explain why dectin 2 and mincle couple FcRγ-signalling to NF-κB activation and BDCA2 does not. Further studies will have to answer this intriguing question.

CLRs and T cell differentiation

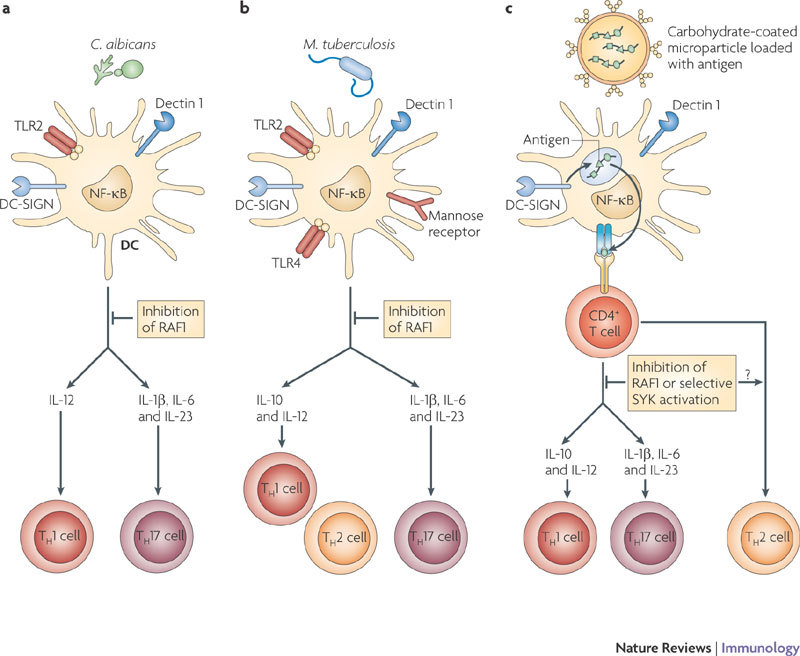

Tailoring of T cell differentiation to pathogens relies on the cooperation and crosstalk between signalling pathways induced by the combination of PRRs (Fig. 5). M. tuberculosis and M. leprae induce the production of IL-10 because they trigger TLRs and DC-SIGN, which enhances TLR-induced NF-κB activity through the RAF1 signalling pathway as described above3. The effect of DC-SIGN signalling on the expression of other cytokines that are crucial for TH cell differentiation has not yet been described but needs to be resolved to understand its effect on adaptive immune responses. Recent studies suggest that DC-SIGN triggering by M. tuberculosis induces TH1 cell differentiation60, whereas Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) induces a mixed TH1- and TH2-type response61 Interestingly, treatment of DCs with the TLR4 ligand lipopolysaccharide and the mycobacterial cell wall component ManLAM also results in the generation of both TH1 and TH2 cells (J. den Dunnen, S.I.G., S.C.M. Bruijns and T.B.H.G., unpublished observations). These data suggest that differences between the observed TH cell differentiation and DC-SIGN-induced IL-10 expression might depend on other PRRs that are also triggered by the pathogens. As well as inducing TH1 cell differentiation , M. tuberculosis has been reported to induce TH17 cell differentiation60. The expression of IL-23 is crucial for the maintenance of TH17 cells and is expressed in response to M. tuberculosis challenge60,62. The DC-SIGN signalling pathway through RAF1 probably has a role in the TH17 cell differentiation, as IL-23 expression by ManLAM-treated DCs is greatly diminished when RAF1 activation is blocked (S.I.G., J. den Dunnen and T.B.H.G., unpublished observations). In addition to TLRs and DC-SIGN, other PRRs such as dectin 1 and an unknown FcRγ-paired receptor8,63,64 recognize mycobacterial PAMPs and contribute to the differentiation of distinct TH cell subsets.

Figure 5. CLR signalling can be harnessed in vaccination approaches to tailor adaptive immune responses to pathogens.

a | Simultaneous triggering of DC-specific ICAM3-grabbing non-integrin (DC-SIGN) and DC-associated C-type lectin 1 (dectin 1) on dendritic cells (DCs) by Candida albicans induces a T helper 1 (TH1) and TH17 cell-mediated immune response that is essential to clear the fungi. Binding of fungi to dectin 1 triggers the spleen tyrosine kinase (SYK)-dependent activation of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) dimers p65–p50, REL–p50 and RELB–p52 (see Fig. 2). Both DC-SIGN and dectin 1 induce the RAF1 pathway, which controls NF-κB activation by inducing p65 acetylation and attenuating the activity of the RELB–p52 dimer. The sequestration of RELB into an inactive RELB–p65 dimer allows the induction of interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-12p70 and IL-23 production and therefore the induction of TH1 and TH17 cells. Inhibition of RAF1 abrogates the expression of cytokines that promote TH1 and TH17 cell development and induces TH2 cell responses. b | Mycobacterium tuberculosis interacts with TLRs, DC-SIGN, mannose receptor and dectin 1 and induces a TH1 and TH17 cell response. Although the signalling pathways that are activated by M. tuberculosis have not been elucidated completely, M. tuberculosis has been shown to trigger DC-SIGN to induce the RAF1 pathway and dectin 1 to induce SYK-dependent NF-κB activation. Integration of these pathways results in a TH1 and TH17 cell response. Inhibition of RAF1 might induce a TH2 cell response given that dectin 1-induced SYK signalling in the absence of RAF1 activation inhibits the production of cytokines that promote TH1 and TH17 cell development. c | Vaccination strategies that specifically target DCs can harness the antigen presentation as well as the signalling ability of CLRs to induce strong tailored immune responses to specific antigens. A carbohydrate-coated microparticle containing antigens can specifically target dectin 1 and DC-SIGN, leading to efficient uptake and presentation of the antigen. Triggering of both dectin 1 and DC-SIGN by the carbohydrate ligands on the microparticle could induce specific TH1 and TH17 cell responses. Differential activation of RAF1 or SYK allows the modulation of the immune responses.

Fungal pathogens such as C. albicans are recognized by dectin 1 through β-glucan structures65 and by DC-SIGN through mannose structures66. This results in protective antifungal immune responses through the induction of both TH1 and TH17 cell-mediated responses in mice and humans4,65 (Fig. 5a). Activation of dectin 1 by β-glucans on mouse DCs results in SYK–CARD9-dependent secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, TNF and IL-23, but little IL-12, and induces TH17 cell responses in vitro65. In vivo immunization using a dectin 1 agonist or C. albicans infection promotes the differentiation of TH1 and TH17 cells. Furthermore, mice deficient in components of the dectin 1 signalling pathway, such as CARD9, do not induce TH17 cell responses and are more susceptible to infections with C. albicans17,65. Notably, dectin 1 is redundant in the TH17 cell response65, suggesting that in the absence of dectin 1 other CLRs, such as dectin 2, might use the SYK–CARD9 complex to induce protective immunity against fungi. It has been shown that the fungal cell wall component zymosan, a stimulus for TLR2 and dectin 1, regulates IL-10 secretion by DCs and transforming growth factor-β production by macrophages to induce immunological tolerance in vivo67. IL-10 secretion by DCs depends on the activation of the ERK signalling pathway, but the direct involvement of dectin 1 was not examined in this study67. Nevertheless, these data suggest that collaboration between dectin 1 and different PRRs results in distinct immune responses, including TH17 cell responses and tolerance, which might depend on the crosstalk between signalling pathways. Manipulation of this signalling crosstalk will allow control of TH cell differentiation. For example, the RAF1 signalling pathway induced by DC-SIGN and dectin 1 seems to control the differentiation of naive T cells to both the TH1 and TH17 cell lineages in response to C. albicans infection. Inhibition of RAF1 abrogates IL-12 expression and skews TH cell differentiation towards a TH2 cell response4. Moreover, TH17 cell differentiation seems equally dependent on the activation of RAF1 in response to dectin 1 triggering, which induces the expression of IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-23, crucial cytokines in promoting the proliferation of TH17 cells in humans4. RAF1 inhibition abrogates TH17 cell differentiation in response to dectin 1 triggering by the β-glucan curdlan (J. den Dunnen, S.I.G., E.C. de Jong and T.B.H.G., unpublished observations). Future studies will show whether some pathogens might manipulate these pathways to skew immune responses in favour of survival. The signalling pathways might also be exploited in vaccine development to fight infections and inflammatory diseases.

Therapeutic potential of CLR signalling

The interaction of several CLRs with pathogens promotes infection by virus dissemination68, immune suppression29 or induction of specific immune responses69. Therefore, targeting these CLRs might prevent pathogenesis; indeed, CLEC5A inhibition during dengue virus infection was shown to prevent virus-induced plasma leakage and vital organ haemorrhaging and to reduce mortality in a mouse infection model69. CLRs are also involved in regulating immune homeostasis, and aberrant CLR expression and/or signalling might drive autoimmune diseases. For example, patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) have significantly reduced numbers of BDCA2-expessing pDCs, and this might account for the excessive production of type I IFNs by pDCs, which is a major pathophysiological factor in SLE, as BDCA2 signalling inhibits TLR-induced type I IFN production by pDCs11,33,70. Furthermore, polymorphisms in the human gene encoding DCIR are associated with rheumatoid arthritis, and DCIR deficiency in mice leads to the development of autoimmune disorders owing to unrestrained growth of DCs, which is consistent with a role for DCIR in the negative regulation of DC expansion71,72. CLRs also seem to be involved in allergic disorders. Dectin 2 triggering by house dust mite allergens leads to cysteinyl leukotriene production, which mobilizes innate immune cells and subsequently aggravates allergic inflammation58. Furthermore, the major peanut allergen Ara h1 interacts with DC-SIGN and induces TH2 cell responses, although a direct involvement of DC-SIGN in this process has not been shown26. These studies suggest that CLR signalling is essential to control immune homeostasis; developing CLR agonists might activate the appropriate signalling pathway to prevent autoimmune disorders, and CLR antagonists could attenuate infections or allergic inflammation.

The signalling functions of CLRs could also be exploited for the development of vaccines. Traditional vaccination strategies are not successful in combating numerous severe infectious diseases, such as AIDS and tuberculosis, cancer or inflammatory diseases, such as asthma or autoimmune diseases. Therefore, new DC vaccination strategies are being developed that not only allow specific delivery of antigens to the antigen-presenting machinery of DCs but also induce or redirect beneficial immune responses1,73,74. Clinical trials of vaccinations with ex vivo-generated DCs pulsed with tumour antigens have provided proof-of-principle that therapeutic immune responses can be elicited through this process1,73,74. However, this type of vaccination approach is laborious and expensive.

A more promising vaccination strategy relies on the in vivo targeting of specific receptors by antibodies coupled to antigens; this allows the efficient delivery of antigens to DCs74. Because of their restrictive expression by DC subsets and their function as uptake receptors (Box 1), CLRs have been prime candidates for this in vivo targeting vaccination strategy. Targeting of CLRs such as DEC205, DC-SIGN or mannose receptor by antibodies efficiently induces antigen-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses73,74,75. In these studies, targeting of DEC205 by antibodies did not result in DC maturation and therefore induced tolerance in the absence of an adjuvant such as CD40 or TLR ligands (for example CpG-containing DNA or polyinosinic–polycytidylic acid)76. This ability can be exploited in vivo to induce disease-specific tolerance to pancreatic islet β-cells77 thereby preventing the development of type 1 diabetes, an autoimmune disease resulting from defects in central and peripheral tolerance and characterized by T cell-mediated destruction of β-cells. Targeting of β-cell antigens to DEC205 expressed by DCs resulted in deletion of β-cell antigen-specific autoreactive CD8+ T cells in a mouse model of type 1 diabetes. Notably, tolerance was induced even in the context of ongoing autoimmunity in a mouse model with known tolerance defects77. Targeting of DEC205 with an antibody does not result in immune activation, which is pivotal to the induction of tolerance, but also suggests that DEC205 does not induce signalling after antibody cross-linking. Identification of its natural ligands will reveal whether DEC205 induces or modulates immune responses after ligand triggering. Recently, CLEC9A has been shown to be involved in the recognition of dead cell remnants that are phagocytosed by DCs for cross-presentation to CD8+ T cells78. Notably, SYK activation seems essential for the observed cross-presentation in vitro, suggesting that signalling by CLRs might also determine the fate of the antigen in the presentation routes (Box 1).

CLR signalling also shapes specific adaptive immune responses and can therefore be exploited to tailor adaptive immune responses to the patient's need (Fig. 5c). Indeed, in vivo immunization of mice with the dectin 1 ligand curdlan induces antigen-specific CD4+ TH1-type and TH17-type, as well as CD8+ T cell, responses through the SYK–CARD9 signalling pathway (see above)65. Immune activation by dectin 1 through zymosan or curdlan in mice that are genetically prone to produce arthritogenic self-reactive T cells can evoke T cell-mediated autoimmune arthritis79. However, immunization with zymosan can also induce tolerance in vivo67, thereby protecting mice from developing type 1 diabetes in a non-obese diabetic mouse model even at early hyperglycaemic stages by inducing regulatory T cells80. Although the mechanisms by which dectin 1 signalling is activating or tolerizing are unclear and might depend on the mouse model and genetic background, these studies suggest that CLR ligands can be used as adjuvants to redirect immune responses.

The recent identification of the RAF1 and SYK signalling pathways induced by dectin 1 provides a rationale for developing immunomodulatory vaccines. RAF1 inhibition induces TH2 cell responses and abrogates TH1 and TH17 cell responses (Ref. 4 and S.I.G., J. den Dunnen, E.C. de Jong and T.B.H.G., unpublished observations). These data suggest that administration of the dectin 1 ligand curdlan in the presence or absence of RAF1 inhibitors could be used to tailor immune responses. However, this is not practical as a general vaccination strategy; RAF1 is involved in cellular processes such as proliferation, differentiation and survival21, and systemic RAF1 inhibition might result in unwanted side effects. However, dectin 1 agonists might be developed that specifically trigger either the SYK or RAF1 pathway, thereby allowing the tailoring of specific immune responses. The collaboration between these pathways with unidentified pathways might explain the data showing that different dectin 1 ligands such as curdlan, fungi and zymosan induce distinct immune responses, including the development of TH1, TH17 and regulatory T cells4,65,67. A better understanding of the different CLRs and pathways involved might provide new targets for modulating immune responses.

Approaches to target CLRs on DCs for antigen delivery involve the administration of carbohydrate-expressing ligands for CLRs or antibodies against CLRs1,74. Vaccinations with carbohydrate-expressing ligands lack specificity, as several CLRs recognize similar carbohydrate moieties. Carbohydrate-expressing ligands can trigger specific signalling properties that might facilitate immune activation1,74, although tumour antigens use the interaction with CLRs to induce immune suppression. Thus, it is essential to investigate in detail the immune response induced by the different targeting strategies. By contrast, antibodies allow specific targeting of the CLRs, but most antibodies do not induce signalling pathways or might induce aberrant signalling. However, antibodies with different signalling properties can be generated to allow antigen delivery in combination with the induction of a specific T cell response. Alternatively, a more complex delivery system, such as liposomes or microparticles, can be used to deliver multiple antigens and a tailored PAMP fingerprint to DCs; this would trigger specific signalling pathways to induce a tailored immune response. Thus, CLRs are attractive targets in DC vaccinations, not only for antigen delivery but also as inducers of adaptive immune responses.

Future directions

The recent advances in our understanding of antigen routing by CLRs and the antigen presenting capacity of specific DC subsets have greatly contributed to the design of vaccines that deliver the antigen to the desired intracellular compartment for MHC class I or II presentation1,73,74. This is crucial for the development of an effective DC vaccine that elicits high-avidity antigen-specific CD4+ T cells and effective CD8+ T cells in vivo to fight cancer or infectious diseases. As CLRs are not just antigen uptake receptors but also modulators or even initiators of adaptive immune responses, targeting CLRs with antibodies or ligands without knowing or understanding the signalling events they induce might have detrimental consequences. New vaccines that harness these powerful signalling properties of CLRs will allow us to tailor immune responses against a specific pathogen or disease. The recent advances in the elucidation of the SYK–CARD9 signalling pathway by dectin 1, the identification of the RAF1 signalling pathway induced by both DC-SIGN and dectin 1, and the importance of NF-κB modulation in fine-tuning cytokine expression have contributed to our understanding of signalling in the induction of adaptive immune responses. However, these studies also suggest that we have only just started to uncover the tip of the signalling iceberg; CLR signalling seems to be carbohydrate specific, and some CLRs such as dectin 1 can induce different signalling pathways by themselves that are integrated in the final immune response. The DC subset that expresses the CLR might also be important32,81,82. Although some CLRs might share signalling pathways, it is to be expected that the diversity in CLR signalling will be great, which is required to combat the diversity of pathogens. However, this diversity will provide some major challenges in elucidating and manipulating the signalling properties of this exciting family of receptors. Nevertheless, although we are just starting to unravel the signalling potential of CLRs, recent advances strongly support the use of CLR targeting in DC vaccinations to induce or redirect adaptive immune responses and improve antigen delivery.

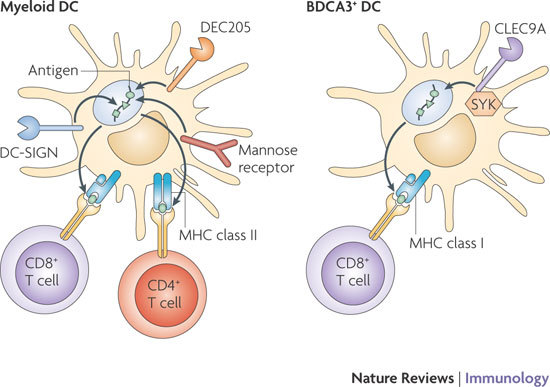

Box 1: Targeting CLRs to enhance antigen presentation.

The recognition of pathogens by C-type lectin receptors (CLRs) is important for their internalization and degradation for innate immune protection and antigen presentation. Notably, the ability of CLRs to deliver antigens to different compartments for processing and presentation has been one of the main reasons that CLRs are targeted in vaccine studies to increase antigen-specific immune responses1,74 (see the figure). The pioneering study targeting DEC205 (also known as LY75) showed that DEC205-specific antibodies that were linked to an antigen of interest resulted in enhanced antigen uptake and presentation by dendritic cells (DCs) to both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells compared with antigen alone83. Since those early studies, it has become clear that targeting of CLRs is a powerful method to enhance antigen presentation and, depending on the CLR that is targeted, can determine whether the antigen is presented in the context of MHC class I or MHC class II molecules or both1. MHC class I presentation is crucial for inducing strong CD8+ T cell responses, which are necessary for immunity to HIV-1 and cancer.

CLRs have a specific expression pattern, and some CLRs, such as DC-specific ICAM3-grabbing non-integrin (DC-SIGN) and DC-associate C-type lectin (dectin 1), are expressed by several DC subsets, such as subepithelial DCs and some myeloid DCs in the blood. By contrast, the expression of other CLRs is restricted to specific DC subsets with specialized functions; langerin (also known as CLEC4K and CD207) expression is restricted to Langerhans cells and a dermal DC subset84, whereas blood DC antigen 2 protein (BDCA2; also known as CLEC4C) is expressed by plasmacytoid DCs33 (Table 1). As distinct DC subsets differentially process and present antigens and thereby induce distinct patterns of T cell activation, the targeting of CLRs allows the delivery of antigen to specific DC subsets, further tailoring the vaccination strategy.

CLR signalling is crucial in shaping adaptive immunity, but a recent study suggests that signalling by CLRs is also involved in antigen routing. C-type lectin domain family 9 member A (CLEC9A; also known as DNGR1) is expressed by mouse CD8α+ DCs and recognizes necrotic cells. Ligand binding to CLEC9A recruits spleen tyrosine kinase (SYK), and, notably, SYK activation is required for cross-presentation of necrotic cell-associated antigens by CLEC9A78(see the figure). Thus, a better understanding of CLR signalling will help to design new vaccination strategies that not only enhance antigen presentation but also direct the activation of specific T cell subsets.

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of the Host–Pathogen Interactions group for their valuable input. S.I.G. and T.B.H.G. are supported by the Dutch Asthma Foundation (grant number 3.2.03.39) and the Dutch Scientific Research program (grant number NWO VIDI 917-46-367), respectively.

Glossary

- T helper (TH) cell

A T cell subset that secretes a distinct set of cytokines after activation, which occurs through the ligation of the T cell receptor with its cognate ligand (peptide–MHC complex), together with the recognition of the appropriate co-stimulatory molecules. Naive TH cells differentiate into TH1, TH2 or TH17 cells, depending on the cytokines and co-stimulatory molecules presented to them by antigen-presenting cells.

- Regulatory T cell

A T cell belonging to a specialized subset of CD4+ T cells that suppresses immune responses to maintain tolerance to antigens, including self antigens.

- Pathogen-associated molecular pattern

A small conserved molecular motif that is consistently found on pathogens; for example, lipopolysaccharides, carbohydrate moieties, double-stranded RNA and unmethylated DNA motifs.

- Tonic calcium signalling

Signalling that is characterized by sustained increased basal intracellular calcium levels, which induces constitutive calcineurin activity. Tonic calcium signalling occurs as a result of exposure of ITAM-coupled receptors to low-avidity ligands.

- Canonical NF-κB pathway

A pathway that involves the activation of IκB kinase-β (IKKβ), which leads to phosphorylation-induced proteolysis of inhibitor of NF-κB (IκB) and consequent nuclear translocation of the nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) subunits p65, REL and p50.

- Non-canonical NF-κB pathway

A pathway that involves the activation of IκB kinase-α (IKKα) by NF-κB-inducing kinase (NIK), which results in the processing of the nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) subunits p100 to p52 and consequent formation of RelB–p52 dimers, which translocate into the nucleus and activate gene transcription.

- Tolerance

A state of lymphocyte non-responsiveness to antigen. The term implies an active process, not simply a passive lack of response.

- Systemic lupus erythematosus

(SLE). An autoimmune disease in which autoantibodies that are specific for DNA, RNA or proteins associated with nucleic acids form immune complexes that damage small blood vessels, especially in the kidney. Patients with SLE generally have abnormal B and T cell function.

- Rheumatoid arthritis

An autoimmune disease that leads to chronic inflammation in the joints and subsequent destruction of the cartilage and erosion of the bone. It is divided into two main phases: initiation and establishment of autoimmunity to collagen-rich joint components, and later events associated with the evolving destructive inflammatory processes.

Biographies

Teunis B. H. Geijtenbeek is a professor of molecular immunology at the Center for Experimental and Molecular Medicine, Academic Medical Center, University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands. He obtained his Ph.D. in chemistry from the University of Utrecht, The Netherlands, and received further postdoctoral training in Nijmegen and New York, after which he started his own research group in the Department of Medical Cell Biology at the VU University Medical Center of Amsterdam, the Netherlands. His laboratory studies the molecular mechanisms of host–pathogen interactions that shape adaptive immunity or promote infection.

Sonja I. Gringhuis received her Ph.D. in molecular biology from the University of Groningen, The Netherlands, where she first encountered the field of signal transduction and transcriptional regulation. She is an assistant professor at the Center for Experimental and Molecular Medicine of the Academic Medical Center, where her research, together with T. Geijtenbeek, now focuses on the molecular mechanisms of C-type lectin receptor signalling following pathogen recognition and the effects on adaptive immunity.

Related links

FURTHER INFORMATION

References

- 1.Steinman RM, Banchereau J. Taking dendritic cells into medicine. Nature. 2007;449:419–426. doi: 10.1038/nature06175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akira S, Uematsu S, Takeuchi O. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell. 2006;124:783–801. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gringhuis SI, et al. C-type lectin DC-SIGN modulates Toll-like receptor signaling via Raf-1 kinase-dependent acetylation of transcription factor NF-κB. Immunity. 2007;26:605–616. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gringhuis SI, et al. Dectin-1 directs T helper cell differentiation by controlling noncanonical NF-κB activation through Raf-1 and SYK. Nature Immunol. 2009;10:203–213. doi: 10.1038/ni.1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rogers NC, et al. SYK-dependent cytokine induction by Dectin-1 reveals a novel pattern recognition pathway for C type lectins. Immunity. 2005;22:507–517. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meyer-Wentrup F, et al. DCIR is endocytosed into human dendritic cells and inhibits TLR8-mediated cytokine production. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2009;85:518–525. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0608352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zelensky AN, Gready JE. The C-type lectin-like domain superfamily. FEBS J. 2005;272:6179–6217. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.05031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rothfuchs AG, et al. Dectin-1 interaction with Mycobacterium tuberculosis leads to enhanced IL-12p40 production by splenic dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 2007;179:3463–3471. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.3463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Kooyk Y, Rabinovich GA. Protein-glycan interactions in the control of innate and adaptive immune responses. Nature Immunol. 2008;9:593–601. doi: 10.1038/ni.f.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sato K, et al. Dectin-2 is a pattern recognition receptor for fungi that couples with the Fc receptor γ chain to induce innate immune responses. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:38854–38866. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606542200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cao W, et al. BDCA2/Fc ɛRIγ complex signals through a novel BCR-like pathway in human plasmacytoid dendritic cells. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e248. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamasaki S, et al. Mincle is an ITAM-coupled activating receptor that senses damaged cells. Nature. Immunol. 2008;9:1179–1188. doi: 10.1038/ni.1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bakker ABH, Baker E, Sutherland GR, Phillips JH, Lanier LL. Myeloid DAP12-associating lectin (MDL)-1 is a cell surface receptor involved in the activation of myeloid cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:9792–9796. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marshall AS, et al. Identification and characterization of a novel human myeloid inhibitory C-type lectin-like receptor (MICL) that is predominantly expressed on granulocytes and monocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:14792–14802. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313127200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Richard M, Thibault N, Veilleux P, Gareau-Pagé G, Beaulieu AD. Granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor reduces the affinity of SHP-2 for the ITIM of CLECSF6 in neutrophils: a new mechanism of action for SHP-2. Mol. Immunol. 2006;43:1716–1721. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen CH, et al. Dendritic-cell-associated C-type lectin 2 (DCAL-2) alters dendritic-cell maturation and cytokine production. Blood. 2006;107:1459–1467. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gross O, et al. Card9 controls a non-TLR signalling pathway for innate anti-fungal immunity. Nature. 2006;442:651–656. doi: 10.1038/nature04926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamasaki S, et al. C-type lectin Mincle is an activating receptor for pathogenic fungus, Malassezia. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:1897–1902. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805177106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goriely S, Neurath MF, Goldman M. How microorganisms tip the balance between interleukin-12 family members. Nature Rev. Immunol. 2008;8:81–86. doi: 10.1038/nri2225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geijtenbeek TBH, et al. Mycobacteria target DC-SIGN to suppress dendritic cell function. J. Exp. Med. 2003;197:7–17. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wellbrock C, Karasarides M, Marais R. The Raf proteins take centre stage. Nature Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004;5:875–885. doi: 10.1038/nrm1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hodges A, et al. Activation of the lectin DC-SIGN induces an immature dendritic cell phenotype triggering Rho-GTPase activity required for HIV-1 replication. Nature Immunol. 2007;8:569–577. doi: 10.1038/ni1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen L-F, et al. NF-κB RelA phosphorylation regulates RelA acetylation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;25:7966–7975. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.18.7966-7975.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen LF, Mu Y, Greene WC. Acetylation of RelA at discrete sites regulates distinct nuclear functions of NF-κB. EMBO J. 2002;21:6539–6548. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caparros E, et al. DC-SIGN ligation on dendritic cells results in ERK and PI3K activation and modulates cytokine production. Blood. 2006;107:3950–3958. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shreffler WG, et al. The major glycoprotein allergen from Arachis hypogaea, Ara h 1, is a ligand of dendritic cell-specific ICAM-grabbing nonintegrin and acts as a Th2 adjuvant in vitro. J. Immunol. 2006;177:3677–3685. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.6.3677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Agrawal S, et al. Different Toll-like receptor agonists instruct dendritic cells to induce distinct Th responses via differential modulation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase–mitogen-activated protein kinase and c-fos. J. Immunol. 2003;171:4984–4989. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.4984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shan M, et al. HIV-1 gp120 mannoses induce immunosuppressive responses from dendritic cells. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e169. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hovius JW, et al. Salp15 binding to DC-SIGN inhibits cytokine expression by impairing both nucleosome remodeling and mRNA stabilization. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e31. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0040031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garg R, et al. CD4 is the receptor for the tick saliva immunosuppressor, Salp15. J. Immunol. 2006;177:6579–6583. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.6579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rock J, et al. CD303 (BDCA-2) signals in plasmacytoid dendritic cells via a BCR-like signalosome involving Syk, Slp65 and PLCγ2. Eur. J. Immunol. 2007;37:3564–3575. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hara H, et al. The adaptor protein CARD9 is essential for the activation of myeloid cells through ITAM-associated and Toll-like receptors. Nature Immunol. 2007;8:619–629. doi: 10.1038/ni1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dzionek A, et al. BDCA-2, a novel plasmacytoid dendritic cell-specific type II C-type lectin, mediates antigen capture and is a potent inhibitor of interferon α/β induction. J. Exp. Med. 2001;194:1823–1834. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.12.1823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kang YJ, et al. Calcineurin negatively regulates TLR-mediated activation pathways. J. Immunol. 2007;179:4598–4607. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.7.4598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hamerman JA, et al. Inhibition of TLR and FcR responses in macrophages by triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells (TREM)-2 and DAP12. J. Immunol. 2006;177:2051–2055. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.4.2051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Turnbull IR, et al. TREM-2 attenuates macrophage activation. J. Immunol. 2006;177:3520–3524. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.6.3520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ivashkiv LB. A signal-switch hypothesis for cross-regulation of cytokine and TLR signalling pathways. Nature Rev. Immunol. 2008;8:816–822. doi: 10.1038/nri2396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meyer-Wentrup F, et al. Targeting DCIR on human plasmacytoid dendritic cells results in antigen presentation and inhibits IFN-α production. Blood. 2008;111:4245–4253. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-081398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]