Abstract

The host response to viral infection includes the induction of type I interferons and the subsequent upregulation of hundreds of interferon-stimulated genes. Ubiquitin-like protein ISG15 is an interferon-induced protein that has been implicated as a central player in the host antiviral response. Over the past 15 years, efforts to understand how ISG15 protects the host during infection have revealed that its actions are diverse and pathogen-dependent. In this Review, we describe new insights into how ISG15 directly inhibits viral replication and discuss the recent finding that ISG15 modulates the host damage and repair response, immune response and other host signalling pathways. We also explore the viral immune-evasion strategies that counteract the actions of ISG15. These findings are integrated with a discussion of the recent identification of ISG15-deficient individuals and a cellular receptor for ISG15 that provides new insights into how ISG15 shapes the host response to viral infection.

Subject terms: Viral host response, Viral infection, Virus-host interactions

Ubiquitin-like protein ISG15 is an interferon-induced protein that has been implicated as a central player in the host antiviral response. In this Review, Perng and Lenschow provide new insights into how ISG15 restricts and shapes the host response to viral infection and the viral immune-evasion strategies that counteract ISG15.

Introduction

During pathogen invasion, the host elicits various defence mechanisms to protect the host. Type I interferons have a central role in regulating this response through the induction of hundreds of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) (reviewed in ref.1). Among these ISGs, ubiquitin-like protein ISG15 is one of the most strongly2 and rapidly3 induced, and recent work has shown that it can directly inhibit viral replication and modulate host immunity.

ISG15 is a member of the ubiquitin family, which includes ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like modifiers (Ubls). Ubiquitin and Ubls are involved in the regulation of a variety of cellular activities, including protein stability, intracellular trafficking, cell cycle control and immune modulation. Whereas some Ubls are constitutively present in the host cell, others are induced by different stimuli. ISG15 and the members of the enzymatic cascade that mediate ISG15 conjugation (ISGylation) are strongly induced by type I interferons3. ISG15 can be covalently conjugated onto target proteins via an enzymatic cascade, yet the fate of these modified proteins is still largely unknown. In addition, ISG15 exists as an unconjugated protein that has been reported to function as a cytokine and can also interact with various intracellular protein partners. Progress has been made in defining some of the mechanisms by which ISGylation of both viral and host proteins inhibit viral replication and the viral evasion strategies that have evolved to circumvent ISG15, yet recent advances in the field have highlighted the complexity of this pathway. There is increasing evidence that unconjugated ISG15 can regulate viral replication and host responses through both non-covalent protein interactions and its action as a cytokine. Human genetic evidence from ISG15-null patients has revealed the importance of ISG15 in the regulation of the type I interferon response4. ISG15-null patients display type I interferon autoinflammation and no apparent increase in susceptibility to viral infection, as compared with ISG15-deficient mice, indicating functional diversity between species5.

In this Review, we discuss the basic biology and characteristics of ISG15 and the ISGylation pathway, how ISG15 regulates viral replication, the immunomodulatory properties of ISG15 and the viral evasion strategies that have evolved to circumvent ISG15.

ISG15 and the ISGylation pathway

ISG15, first identified from the study of type I interferon-treated cells6,7, is composed of two ubiquitin-like domains that have ~30% amino acid sequence homology to ubiquitin, linked by a short hinge region7–10. In addition to being strongly induced by type I interferons, ISG15 is also induced by viral and bacterial infections11,12, lipopolysaccharide (LPS)13, retinoic acid14 or certain genotoxic stressors15, indicating that the expression of ISG15 represents a host response to pathogenic stimuli.

ISG15 exists as a 17 kDa precursor protein that is rapidly processed into its mature 15 kDa form via protease cleavage to expose a carboxy-terminal LRLRGG motif11,16. ISG15 is covalently conjugated to target proteins through this motif by a three-step process known as ISGylation (reviewed in ref.17) (Fig. 1). To date, hundreds of putative targets of ISGylation have been identified using mass spectrometry; however, only a subset of these has been validated18,19 (Table 1). The functional consequence of ISGylation is still poorly understood. Unlike ubiquitylation, ISGylation does not appear to directly target proteins for proteasome-mediated degradation20. Studies of specific ISGylated proteins have found that ISG15 can compete with ubiquitin for ubiquitin binding sites on a protein, thereby indirectly regulating protein degradation21. In addition, ISG15-ubiquitin mixed chains have been observed and may negatively regulate the turnover of ubiquitylated proteins22. However, for every ISGylated protein studied, only a small fraction of the total pool of a protein is modified by ISG15, making it a challenge to understand how ISGylation can impact the overall function of a protein. One possibility is that modification of a protein alters its cellular localization and function, as was seen with the ISGylation of filamin B23. In addition, for proteins that multimerize or polymerize, the modification of only a small fraction of the protein could disrupt the assembly of protein complexes, as has been observed with influenza B virus (IBV) and human papilloma virus (HPV) (see discussion below).

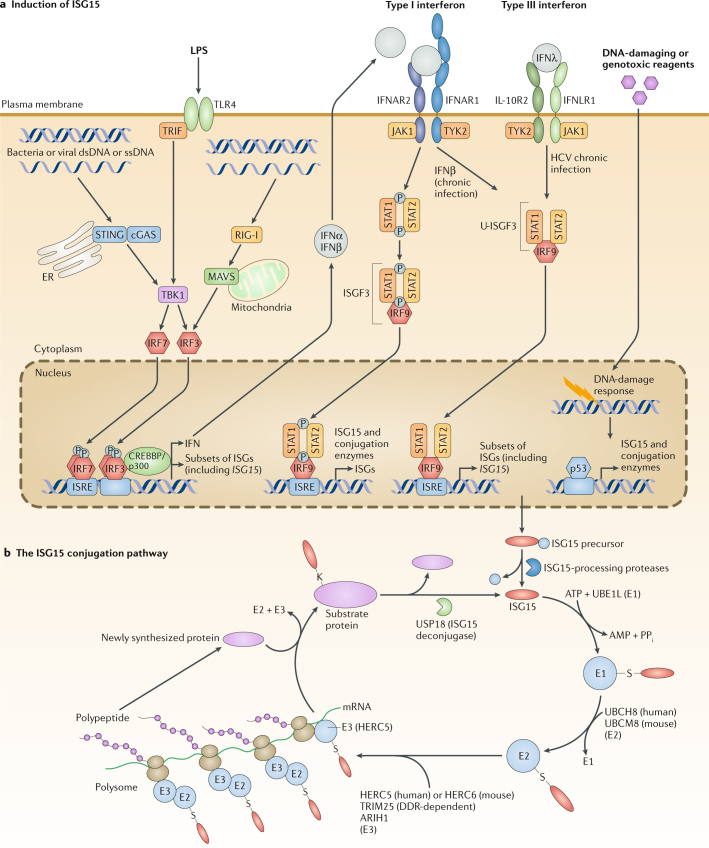

Fig. 1. The ISG15 conjugation pathway.

a | Induction of ubiquitin-like protein ISG15. The expression of ubiquitin-like protein ISG15 and members of the ISG15 conjugation pathway is strongly induced by type I interferons (IFNs). Upon type I interferon stimulation, interferon regulatory factor 9 (IRF9) interacts with phosphorylated signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1) and STAT2 and forms the interferon-stimulated gene factor 3 (ISGF3) complex, which recognizes the interferon-sensitive response element (ISRE) promoters of ISG15 and its conjugation enzymes to induce their expression. During chronic viral infection, both IFNβ and type III interferons lead to the formation of an unphosphorylatyed ISGF3 (U-ISGF3) complex, which is composed of IRF9 and unphosphorylated STAT1–STAT2 (refs127,128), to induce the expression of a subset of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs), including ISG15 (ref.89). Additional stimuli, including lipopolysaccharide (LPS), foreign DNA or RNA, retinoic acid and DNA-damaging agents, are also able to induce the expression of ISG15. LPS was shown to induce ISG15 expression via TIR domain-containing adapter protein inducing IFNβ (TRIF; also known as TICAM1)–IRF3 signalling pathways, but this stimulation still functioned in a type I interferon-dependent manner129. Retinoic acid can also induce ISG15 expression through its induction of type I interferons14,130. By contrast, the introduction of double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) could induce ISG15 expression via IRF3 in an interferon-independent manner131. IRF3 forms a complex with CREB-binding protein (CREBBP)/p300 and binds to the ISRE elements to induce ISG15 expression132,133. Bacterial DNA can also induce ISG15 expression independent of type I interferon and can signal through a cytosolic surveillance pathway that requires stimulator of interferon genes protein (STING), serine/threonine-protein kinase TBK1, IRF3 and IRF7 (ref.12). Notably, the expression of ISG15 and its conjugation enzymes is controlled by the ISRE elements, mediated by various IRFs. However, a recent study found that ISG15, as well as its conjugation enzymes, including ubiquitin-activating enzyme E1 homologue (UBE1L), ubiquitin/ISG15-conjugating enzyme E2 L6 (UBCH8) and E3 ubiquitin/ISG15 ligase TRIM25, possess cellular tumour antigen p53-responsive elements in their promoters134. DNA-damaging (for example, ultraviolet light or doxorubicin134) or agents (for example, camptothecin15) induce p53, which binds to these p53-responsive elements to transactivate the ISG15 pathway. b | The ISG15 conjugation pathway. ISG15 is initially expressed as a 17 kDa precursor protein that is then processed into its mature 15 kDa form via protease cleavage11,16. Conjugation of ISG15, commonly referred to as ISGylation, utilizes a three-step enzymatic cascade similar to that of ubiquitination. The activating E1 enzyme UBE1L functions only in the ISG15 pathway135,136, forming an ATP-dependent thioester bond with ISG15 (ref.137). Following activation, ISG15 is transferred to the active-site cysteine of the ubiquitin/ISG15-conjugating enzyme E2 L6 (UBCM8) (in mouse) and UBCH8 (in human)138,139. Finally, an E3 ligase facilitates the conjugation of ISG15 to target proteins. Although several enzymes, including E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase ARIH1 and TRIM25, have been found to act as E3 ligases within the ISG15 pathway140,141, human HERC5 (mouse HERC6) appears to be the dominant E3 ligase that coordinates the conjugation of the majority of substrates to ISG15 (refs91,142–145). However, during DNA-damage responses (DDRs),TRIM25 also serves as a p53-specific ISG15 E3 ligase134. Notably, its corresponding E2 enzyme for ISG15 conjugation has not been identified. HERC5 associates with polyribosomes and appears to target newly synthesized proteins, including viral proteins and many interferon-induced proteins54. ISGylation is also reversible via the specific removal of ISG15 from conjugated proteins by the deconjugating enzyme Ubl carboxy-terminal hydrolase 18 (USP18)24,25. cGAS, cyclic GMP-AMP synthase; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; HCV, hepatitis C virus; IFNAR1, interferon α/β receptor 1; IFNAR2, interferon α/β receptor 2; IFNLR1, interferon-λ receptor 1; IL-10R2, interleukin-10 receptor subunit 2; JAK1, Janus kinase 1; MAVS, mitochondrial antiviral-signalling protein; RIG-I, retinoic acid-inducible gene I; ssDNA, single-stranded DNA; TLR4, Toll-like receptor 4.

Table 1.

ISGylation of host and viral proteins and the impact on their functions

| Protein | Biological effects of ISGylation | Impact on infection |

|---|---|---|

| ISGylation of host proteins | ||

| STAT1 | Preserves STAT1 phosphorylation and activation84 | Suppression of STAT1 ISGylation exacerbates HCV pathogenesis84 |

| RIG-I | Downregulates RIG-I-mediated signalling162 | Reduces interferon promoter activity but does not impact NDV viral replication162 |

| TSG101 | Modulates TSG101-mediated intracellular trafficking66,67 | Blocks HIV budding and release71 and IAV HA protein transportation66 |

| PKR | Results in increased phosphorylation of eIF2α and decreased protein synthesis83 | May impact viral protein translation |

| CHMP5 | Inhibits LIP5–VPS4 interaction mediated by CHMP5 (ref.72) | Inhibits HIV-1 and ASLV VLP budding and release72 |

| IRF3 | Sustains IRF3 activation by attenuating its interaction with PIN1 (ref.79) | Inhibits SeV replication79 |

| Golgi apparatus and ER proteins | Increases secretion of cytokines12 | Restricts Listeria monocytogenes infection12 |

| Ubiquitin | Negatively regulates cellular turnover of ubiquitylated proteins22 | Unknown |

| BECN1 | Negatively regulates autophagy and EGFR degradation51 | Unknown |

| JAK1, phospholipase Cγ1 and ERK1 | Key regulators of signal transduction82, but the functional importance of ISGylation has not been evaluated | Unknown |

| IFIT1 and MxA | Human ISG15 conjugation targets; the functional significance of ISGylation has not been evaluated19 | Unknown |

| p53 | Degrades misfolded, dominant-negative p53 (ref.163); suppresses cell growth and tumorigenesis under DNA-damaging conditions134 | Unknown |

| Filamin B | Impairs interferon-induced JNK1 activation and apoptosis23 | Unknown |

| PCNA | Prevents excessive mutagenesis during DNA-damage repair164 | Unknown |

| β-Catenin | Elicits antitumour activity by suppressing WNT signalling165 | Unknown |

| HIF1α | Impairs HIF1α-mediated gene expression and tumorigenic growth166 | Unknown |

| Parkin | Increases ubiquitin E3 ligase activity of parkin and its cytoprotective effect167 | Unknown |

| IQGAP1 | Reduces active CDC42 and RAC1, which are critical in compensating for DOCK6 disruption in Adams–Oliver syndrome168 | Unknown |

| UBC13 | Suppresses its ubiquitinase activity169 | Unknown |

| UBCH6 | Suppresses its ubiquitinase activity170 | Unknown |

| PP2Cβ | Suppresses NF-κB activation171 | Unknown |

| TRIM25 | Inhibits its own ISGylase activity172 | Unknown |

| 4EHP | Enhances mRNA 5′ cap structure-binding activity141 | Unknown |

| Cyclin D1 | Inhibits cyclin D1 and suppresses cancer cell growth173 | Unknown |

| PML–RARα | Represses PML–RARα upon RA treatment174 | Unknown |

| ΔNp63α | Unable to promote cell growth and tumour formation175 | Unknown |

| ISGylated viral proteins | ||

| IAV NS1 | Inhibits its nuclear translocation55 and restores host antiviral responses56 | Inhibits IAV replication55,56 |

| CVB3 2APro | Inhibits its protease activity to restore host protein translation48 | Inhibits CVB3 replication48 |

| IBV NP | ISGylated NPs act as a dominant-negative inhibitor of oligomerization of unmodified NPs, which impedes viral RNA synthesis62 | Inhibits IBV replication62 |

| HPV-16 capsid protein L1 | Impedes release of viral particles and decreases infectivity54 | Reduces infectivity of HPV-16 (ref.54) |

| HCMV pUL26 | Restores NF-κB signalling64 | Suppresses HCMV growth64 |

2Apro, 2A protease; 4EHP, eIF4E-homologous protein; ΔNp63α, alternative splice variant of tumour protein p63-α; ASLV, avian sarcoma leukosis virus; BECN1, beclin 1; CHMP5, charged multivesicular body protein 5; CVB3, coxsackievirus B3; DOCK6, dedicator of cytokinesis protein 6; eIF2α, eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 subunit-α; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; ERK1, extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1; HA, haemagglutinin; HCMV, human cytomegalovirus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIF1α, hypoxia inducible factor 1α; HPV-16, human papilloma virus 16; IAV, influenza A virus; IBV, influenza B virus; ISG15, ubiquitin-like protein ISG15; IQGAP1, RAS GTPase-activating-like protein IQGAP1; IRF3, interferon regulatory factor 3; IFIT1, interferon-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 1; JAK1, Janus kinase 1; JNK1, c-Jun N-terminal kinase 1 (also known as MAPK8); LIP5, LYST-interacting protein 5 (also known as VTA1); MxA, interferon-regulated resistance GTP-binding protein MxA; NDV, Newcastle disease virus; NF-κB, nuclear factor-κB; NPs, nucleoproteins; NS1, non-structural protein 1; PCNA, proliferating cell nuclear antigen; PKR, dsRNA-activated protein kinase R; PIN1, peptidyl-prolyl cis–trans isomerase NIMA-interacting 1; PML–RARα, promyelocytic leukaemia–retinoic acid receptor-α oncofusion protein; PP2Cβ, protein phosphatase 2C isoform-β; RAC1, RAS-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1; RA, retinoic acid; RIG-I, retinoic acid-inducible gene I protein; SeV, Sendai virus; STAT1, signal transducer and activator of transcription 1; TRIM25, E3 ubiquitin/ISG15 ligase; TSG101, tumour susceptibility gene 101 protein; UBC13, ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 N; UBCH6, ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 E1; VLP, virus-like particle; VPS4A, vacuolar protein sorting-associated protein 4A.

ISGylation can be reversed by the deconjugating enzyme Ubl carboxy-terminal hydrolase 18 (USP18)24,25. The specificity of USP18 for ISG15 is achieved through the hydrophobic interaction between a hydrophobic patch in USP18 and a hydrophobic region unique to ISG15 (ref.25). Of note, independent of its deconjugating activity, USP18 also binds to the second chain of the interferon α/β receptor 2 (IFNAR2) complex, competing with Janus kinase 1 (JAK1) for binding and, therefore, functions as a negative regulator of interferon signalling26. Thus, studies involving USP18 need to be interpreted with caution to differentiate between effects on ISG15 conjugation or dysregulated interferon signalling27.

ISG15 also exists as an unconjugated protein. In vivo, ISG15 has been detected in the serum of patients treated with interferon and in virally infected mice28–31. Extracellular ISG15 has been proposed to function as a cytokine with several immunomodulatory activities, including the induction of natural killer (NK) cell proliferation32, the stimulation of interferon-γ (IFNγ) production5 and the induction of dendritic cell maturation33, and to function as a chemotactic factor for neutrophils34. Its mechanism of release is unclear as ISG15 does not contain a leader signal; however, recent studies have shown that it could be released via non-conventional secretion, including in exosomes35, through the release of neutrophil granules from secretory lysosomes or via apoptosis36. Recently, lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 (LFA1) was identified as a cell surface receptor for extracellular ISG15. Binding of ISG15 to LFA1 stimulated the release of IFNγ and interleukin-10 (IL-10) from IL-12 primed cells37. The impact that extracellular ISG15 exerts during viral infection remains to be determined.

It has recently been shown that, similar to ubiquitin, free, intracellular ISG15 can non-covalently bind to intracellular proteins and modulate their functions3,38 (Fig. 2). Free intracellular ISG15 has been shown to bind to and block the enzymatic activities of enzymes39,40. ISG15 has also been shown to regulate type I interferon signalling by stabilizing USP18 (ref.4) and by interacting with leucine-rich repeat-containing protein 25 (LRRC25) to mediate the autophagic degradation of retinoic acid-inducible gene I protein (RIG-I; also known as DDX58)41. In the following sections, we discuss recent insights into ISGylation and the role of free intracellular and extracellular ISG15 during viral infections.

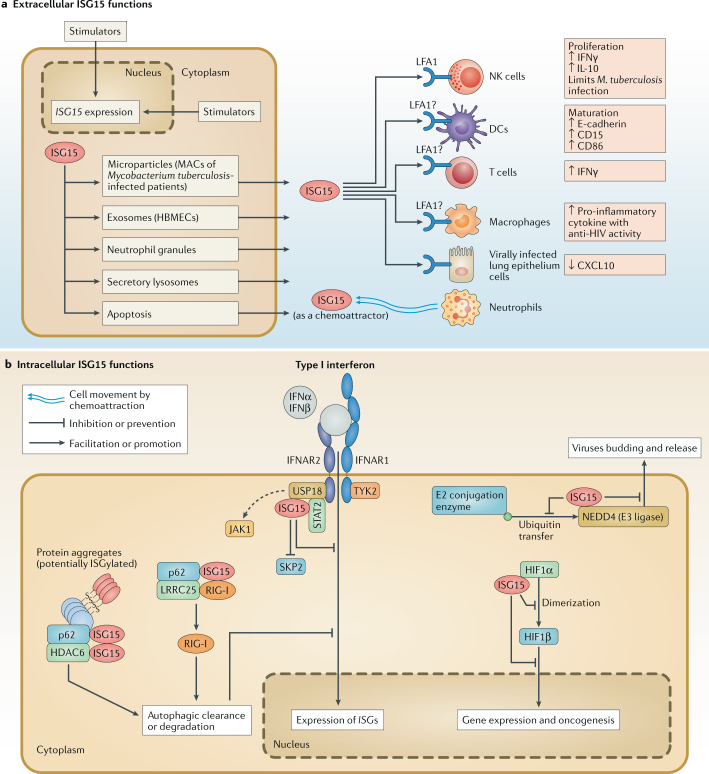

Fig. 2. Extracellular and intracellular functions of unconjugated ISG15.

a | Extracellular functions. Several immunomodulatory and cytokine functions have been ascribed to ubiquitin-like protein ISG15. Although it does not possess a leader signal sequence to direct its secretion, ISG15 has been found to be released through microparticles146, exosomes35 and neutrophilic granules5; from secretory lysosomes36; and via apoptosis36. It has been described as influencing the functions of several different types of cells. Natural killer (NK) cells: ISG15 induces NK cell proliferation32 and stimulates interferon-γ (IFNγ) production5. Dendritic cells (DCs): ISG15 induces DC maturation and upregulates the expression of E-cadherin, CD15 and CD86 (ref.33). Neutrophils: ISG15 functions as a chemotactic factor and an activator of neutrophils34. T cells: ISG15 was found to induce the secretion of IFNγ147. Macrophages: ISG15-containing microparticles and exosomes have been found to stimulate macrophages to secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines146 and mediate anti-HIV activity35, respectively. It remains to be determined whether it is a stand-alone effect of ISG15 or an effect synergistic with those of other molecules in the secretory vesicles. Lung epithelium cells: recombinant ISG15 reduces CXC-chemokine ligand 10 (CXCL10) protein production in human rhinovirus-16 (HRV-16)-infected human bronchial epithelial (HBE) cells148. ISG15 receptor: lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 (LFA1; also known as αLβ2 integrin, or CD11a/CD18) was recently identified as a cell surface receptor for extracellular ISG15. Binding of ISG15 to LFA1 on NK cells stimulated the release of IFNγ and interleukin-10 (IL-10) from IL-12 primed NK cells37. Whether LFA1 senses extracellular ISG15 in other cell types remains to be determined. b | Intracellular functions: Ubl carboxy-terminal hydrolase 18 (USP18) and S-phase kinase-associated protein 2 (SKP2): USP18, which is induced by type I interferons, mediates the negative feedback regulation of interferon signalling independent of its deISGylase activity. USP18 is recruited by signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT2) and binds to interferon α/β receptor 2 (IFNAR2) of the interferon receptor complex, displacing Janus kinase 1 (JAK1) and suppressing interferon signalling and the downstream expression of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs)149. Notably, human ISG15 binds to USP18 and inhibits SKP2-mediated ubiquitylation and proteasomal-mediated degradation4,114. In the absence of human ISG15, human USP18 is degraded, and this allows for continued JAK1 binding to the IFNAR2 complex and prolonged IFNAR signalling and ISG expression26. By contrast, mouse ISG15 does not alter the stability of mouse USP18 and its ability to suppress IFNAR signalling, although the precise reason for this difference is still unclear, as discussed in Box 1 (ref.53). Histone deacetylase 6 (HDAC6) and ubiquitin-binding protein p62 (also known as SQSTM1): intracellular ISG15 binds to HDAC6 and p62 to regulate autophagic clearance of proteins, especially ISGylated proteins40. Leucine-rich repeat-containing protein 25 (LRRC25)–retinoic acid-inducible gene I protein (RIG-I)–p62: intracellular ISG15 binds to LRRC25, p62 and RIG-I to mediate the autophagic degradation of RIG-I, which is critical to LRRC25-mediated downregulation of type I interferon signalling41. Hypoxia inducible factor 1α (HIF1α): ISG15 has been shown to interact with HIF1α, preventing its dimerization with HIF1β to initiate downstream gene expression. E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase NEDD4: ISG15 has been shown to bind to the NEDD4 and disrupt its interaction with ubiquitin E2 conjugating enzymes, preventing ubiquitin from being transferred to NEDD4 for ubiquitylation. The E3 ubiquitin ligase activity of NEDD4 is critical to Ebola virus-like particle virus budding39,69. HBMECs, human brain microvascular endothelial cells; MACs, macrophages.

ISG15 and viral infection

Early on, it was hypothesized that ISG15 would regulate the host antiviral response42. This stemmed from the rapid upregulation of ISG15 and members of the conjugation cascade by both type I interferons and several viruses43.

Early in vitro experiments used either the overexpression or knockdown of mouse or human ISG15 in cultured cells and found that ISG15 inhibited the growth of many viruses (reviewed in refs44,45, Fig. 3). Additional evidence that ISG15 functions as an antiviral molecule came from the study of infected mice in which ISG15 or genes of the conjugation cascade were knocked out (Fig. 3). Mice lacking ISG15 or the ISG15 E1 enzyme, ubiquitin-activating enzyme E1 homologue (UBE1L; also known as UBA7), were more susceptible to Sindbis virus46, influenza A virus (IAV) and IBV30,46,47 than wild-type mice. During infection with IBV, mice lacking ISG15 or UBE1L displayed a 3–4 log increase in virus in their lungs compared with wild-type mice, and cells derived from these mice supported increased viral replication, supporting the hypothesis that protein ISGylation restricts viral replication30. Studies with coxsackievirus B3 virus (CVB3) also confirmed an antiviral role for ISG15 that is mediated through its conjugation activity48. Both Isg15−/− and Ube1l−/− mice infected with CVB3 displayed more severe myocarditis, increased viral loads and increased lethality following infection48. The development of Usp18-knock-in mice (in which the deconjugating activity of USP18 was disrupted while leaving its ability to regulate interferon signalling intact) revealed that an accumulation of ISG15 conjugates resulted in increased resistance to infection during IBV and vaccinia virus infection49. In these examples, ISG15 protected the host by functioning as a bona fide antiviral protein, inhibiting viral replication in a conjugation-dependent manner. Whether these targets are viral or host proteins is still under investigation. Perhaps the strongest evidence that ISG15 has an important antiviral role is the increasing number of viral immune-evasion proteins that target the ISG15 pathway. Efforts are now focused on determining the mechanisms by which ISG15 regulates these responses (see discussion below and Fig. 4).

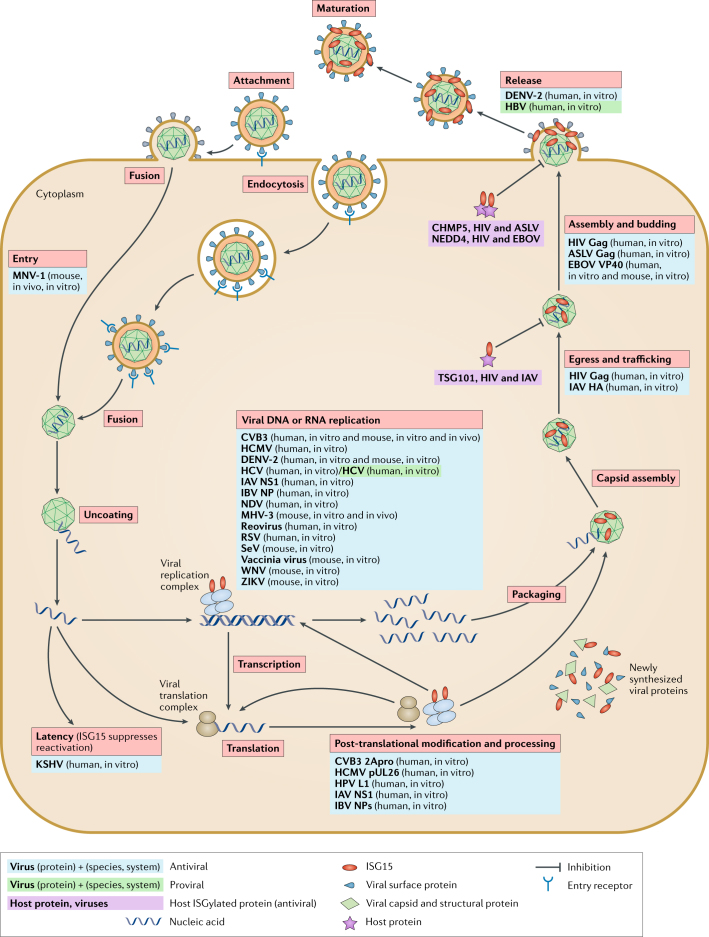

Fig. 3. Direct effects of ISG15 on viral replication.

In general, the viral replication cycle consists of the following steps: attachment, entry, uncoating, viral replication complex formation, transcription, translation, post-translational modification and processing of viral proteins, packaging, capsid assembly, egress and trafficking, assembly and budding, release and virion maturation. Ubiquitin-like protein ISG15 was found to restrict the infection of murine norovirus at the virus entry or uncoating step150. This inhibition was conjugation-dependent, but the precise mechanism is still unknown. Viral DNA or RNA replication: many studies of the antiviral activity of ISG15 analysed the replication of viral DNA or RNA in the presence or absence of ISG15 and its conjugation machinery. During IBV infection, ISG15 disrupts the viral replication machinery through conjugation to the viral nucleoprotein (NP), disrupting its ability to oligomerize and form viral nucleoproteins (vRNPs), thus inhibiting viral RNA synthesis62. In addition, the replication of many viruses (blue) was inhibited by ISG15 (refs48,50,64,79,85,88,92,98,151–155), yet the precise mechanisms by which ISG15 inhibits their replication remain unclear. During chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection (green), ISG15 appeared to have a proviral role86,87 because its overexpression reduced the responsiveness of the cell to interferon-α (IFNα) by maintaining the abundance of Ubl carboxy-terminal hydrolase 18 (USP18), a negative regulator of type I interferon receptor signalling89. In post-translational modification and processing, ISG15 conjugation has been shown to target newly synthesized proteins, including viral proteins and several interferon-stimulated genes during the type I interferon response54. ISGylation of viral proteins acts as a host antiviral strategy. ISGylation of such proteins elicits antiviral effects by impairing their function, for example, essential effectors of viral replication complex (influenza B virus (IBV) NP62 and influenza A virus (IAV) NS1/A55), proteins involved in host shut-off (coxsackie virus 3 (CVB3) 2A protease (2APro)48), counteractors of host immunity (human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) pUL26 (ref.64)) and capsid proteins (human papilloma virus (HPV)-16 L1)54. Egress and trafficking and assembly and budding: both ISG15 and ISG15 conjugation have been shown to restrict intracellular trafficking of viruses and/or subsequent viral release from the cell surface65,72, mostly by targeting host proteins necessary for trafficking (for example, tumour susceptibility gene 101 protein (TSG101)66) or for release and/or budding (for example, ubiquitin protein ligase NEDD4 (refs39,69)) and preventing their interactions with either viral proteins or members of the host transportation complex65,73. Viral release: for specific viruses, ISG15 was found to modulate the amount of released infectious viral particles while intracellular viral replication remains intact. Interestingly, whereas the molecular mechanism is unclear, such effects can be either antiviral (for example, dengue virus 2 (DENV-2))156 or proviral (for example, hepatitis B virus (HBV))157 depending on the type of virus. Viral latency: ISG15 was also shown to maintain viral latency and prevent reactivation of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) infection via the regulation of specific KSHV microRNAs74,158. ASLV, avian sarcoma leukosis virus; CHMP5, charged multivesicular body protein 5; CVB3, coxsackievirus B3; EBOV, Ebola virus; HA, haemagglutinin; MHV-3, murine hepatitis virus 3; MNV-1, murine norovirus 1; NDV, Newcastle disease virus; NS1, non-structural protein 1; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; SeV, Sendai virus; WNV, West Nile virus; ZIKV, Zika virus.

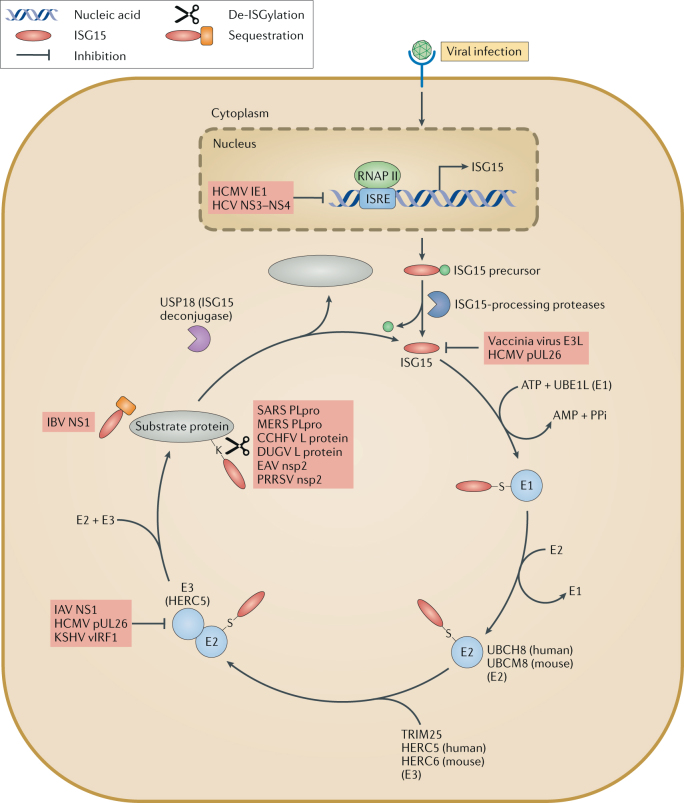

Fig. 4. Viral immune-evasion strategies targeting the ISG15 pathway.

Viral immune-evasion strategies have been identified that target the ubiquitin-like protein ISG15 pathway. Certain viruses, for example, human cytomegalovirus (HCMV)64,159 and hepatitis C virus (HCV)160,161, suppress the expression of ISG15 at the transcriptional level. Vaccinia virus E3L92 and HCMV pUL26 (ref.64) proteins bind to ISG15 to inhibit ISG15 conjugation by undefined mechanisms. HCMV pUL26 (ref.64), influenza A virus (IAV) non-structural protein 1 (NS1)55 and Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) viral interferon regulatory factor 1 (vIRF1)75 also interact with an E3 ISG15–protein ligase HERC5 to reduce protein conjugation by ISG15. Even when the viral and host proteins are conjugated to ISG15, viruses have also developed strategies to deconjugate or sequester ISGylated viral proteins. Influenza B virus (IBV) NS1 protein counteracts ISG15 antiviral activity by sequestering ISGylated viral proteins, particularly viral nucleoproteins (NPs), to prevent their incorporation into NP oligomers, thus disrupting viral RNA synthesis62. Several virus families encode enzymes possessing deISGylase activities, including papain-like protease (PLpro) of coronaviruses and viral ovarian tumour domain (OTU) proteases of nairoviruses and arteriviruses, to remove ISG15 from conjugated proteins93. CCHFV, Crimean–Congo haemorrhagic fever virus; DUGV, Dugbe virus; EAV, equine arteritis virus; HERC5, E3 ISG15–protein ligase HERC5; HERC6, E3 ISG15–protein ligase HERC6; IE1, immediate-early protein 1; ISRE, interferon-stimulated response elements; MERS, Middle East respiratory syndrome; NS3, non-structural protein 3; PRRSV, porcine respiratory and reproductive syndrome virus; RNAP II, RNA polymerase II; SARS, severe acute respiratory syndrome; TRIM25, E3 ubiquitin/ISG15 ligase; UBCH8, ubiquitin/ISG15-conjugating enzyme E2 L6; UBCM8, ubiquitin/ISG15-conjugating enzyme E2 L6; UBE1L, ubiquitin-activating enzyme E1 homologue; USP18, Ubl carboxy-terminal hydrolase 18.

However, recent findings have challenged the notion that the dominant function of ISG15 is as an antiviral protein that directly inhibits viral replication. First, Isg15−/− mice are not susceptible to all viruses, and even for virus challenge experiments in which Isg15−/− mice have increased lethality, it is not always due to increased viral replication31,50. As discussed below, ISG15 can regulate cytokine responses31 and the host damage and repair response50. In addition, ISG15 has been shown to regulate cellular processes that include autophagy40,41,51 and metabolism52. Regulation of these processes could indirectly affect the outcome during viral infection. Second, the identification of ISG15-null patients who have a type I interferon autoinflammatory condition and, to date, no increased susceptibility to viral infection raises questions as to whether ISG15 is an essential antiviral molecule (reviewed in ref.45) (Box 1). This phenotype is in contrast to Isg15−/− mice that do not display type I interferon autoinflammation53, indicating that ISG15 may have divergent functions between different species. These observations increase our understanding of the ISG15 pathway but must also be taken into consideration when interpreting future studies on ISG15. For the remainder of this Review, we explore our understanding of the mechanism by which ISG15 regulates viral replication and the host response in both mice and humans.

Box 1 | Insights into ISG15 functions from ISG15-deficient individuals.

In recent years, several individuals with inherited ubiquitin-like protein ISG15 deficiency have been identified and have provided insights into the biological function of human ISG15. Initially, three patients with inherited ISG15 deficiency were found in Turkey and Iran5. They clinically presented with a Mendelian susceptibility to mycobacterial disease5. The initial analyses supported the hypothesis that these individuals had reduced levels of interferon-γ (IFNγ) upon bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccine challenge owing to a lack of extracellular ISG15, which had been previously shown to act as a cytokine to stimulate IFNγ production5. In vitro experiments using fibroblasts derived from these individuals demonstrated that such defects could be partially rescued by recombinant ISG15 or fully recovered by a combination of ISG15 and interleukin-12 (IL-12). In a second study, three individuals with ISG15 deficiency were identified in China4. These individuals presented with seizures and had intracranial calcifications, a phenotype seen in patients with Aicardi–Goutières syndrome (AGS), in which various mutations result in enhanced type I interferon production. In vitro characterization using cells isolated from these individuals showed elevated type I interferon levels and hyperresponsiveness to type I interferon stimulation, including prolonged signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1) and STAT2 phosphorylation4. This hyperresponsive phenotype was similar to that previously observed in Usp18−/− mice113. Indeed, individuals lacking ISG15 expressed lower levels of Ubl carboxy-terminal hydrolase 18 (USP18), which was rescued by complementation with either wild-type or a non-conjugatable form of ISG15 (ref.4). ISG15 was shown to bind to and prevent USP18 degradation mediated by S-phase kinase-associated protein 2 (SKP2)-dependent ubiquitylation4,114. Therefore, in the absence of ISG15, USP18 is ubiquitylated and degraded, and an important negative regulator of type I interferon receptor signalling is lost. Notably, neonates with USP18 deficiency were also recently identified and were found to die soon after birth owing to the dysregulation of type 1 interferon responses115. Together, these findings indicate that ISG15 has an important role in the regulation of the type 1 interferon response.

Surprisingly, individuals with ISG15 deficiency were not reported to have any clinical presentations consistent with severe viral infections despite having antibodies confirming the exposure to many viruses. Cells derived from these individuals also did not support increased viral replication when challenged with a variety of viruses5. In a follow-up study, it was found that following prolonged interferon pre-treatment, cells derived from ISG15-deficient individuals were in some cases resistant to viral infection53. This finding raises questions as to why mice lacking ISG15 have a substantial increase in susceptibility to viral infection. A subsequent analysis of cells derived from ISG15-deficient mice and humans demonstrated that, unlike human ISG15, which can bind to human USP18 and prevent its ubiquitylation and subsequent SKP2-mediated degradation, mouse ISG15 was not able to stabilize USP18 (ref.53). Biochemical experiments indicated that this was due to an inability of mouse ISG15 to bind to USP18 (ref.53). However, a recent study solved the crystal structure of mouse ISG15 in complex with USP18, which suggested that the sites of interactions are well conserved among several species, raising questions as to why these mouse proteins do not stably bind to each other in in vitro biochemical experiments25. Further studies are needed to determine why human ISG15 but not mouse ISG15 appears to be able to stabilize USP18 and regulate interferon signalling.

Direct effects of ISG15 on viral replication

Recent studies have shown that the ISGylation of both host and viral proteins and the non-covalent binding of ISG15 to host proteins can disrupt viral replication. Several of these examples are discussed below.

ISGylation of viral proteins

ISGylation, through the localization of E3 ISG15–protein ligase HERC5 to polyribosomes, can target nascent proteins, making viral proteins, which are the dominant proteins within an infected cell, likely targets54. Although an extensive characterization of protein ISGylation during different viral infections has not been reported, several viral proteins have been identified as substrates for ISG15 conjugation (Fig. 3). In these studied examples, ISGylation of viral proteins can disrupt their interaction with host pathways that are required for replication, disrupt the oligomerization of viral proteins and/or the geometry of the virus, or disrupt viral protein function, resulting in reduced viral replication or the alteration of the host immune response.

The first viral protein that was found to be modified was the non-structural protein 1 of IAV (NS1/A)55,56. NS1/A is crucial to viral replication as it inhibits the induction of type I interferons57, blocks the activation of protein kinase R (PKR)58, selectively enhances viral mRNA translation59 and interferes with cellular mRNA processing60,61. Modification of the lysine at position 41 (K41) of NS1/A inhibited the nuclear translocation of NS1/A by disrupting its interaction with importin-α55, leaving the virus susceptible to inhibition by interferon. In a second study, ISGylation of NS1/A at distinct sites disrupted its interaction with several binding partners, including the amino terminus of PKR, the RNA-binding domain of NS1/A, U6 small nuclear RNA (snRNA) and double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), limiting its ability to disrupt the host antiviral response56. Together, these findings provided the initial evidence that ISG15 can modify viral proteins and directly antagonize virus replication.

The CVB3 protease 2 A (2APro) is also targeted for ISGylation48. The 2APro protein mediates the cleavage of the mammalian eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4γ1 (eIF4G1), resulting in shut-off of host cell protein synthesis, which in turn promotes viral replication. ISGylation of 2APro hinders the cleavage of eIF4G during CVB3 infection, diminishing host cell shut-off and reducing CVB3 replication48.

Studies of IBV and HPV have suggested that ISGylation of viral proteins blocks oligomerization, disrupting the function and geometry of viral complexes. Oligomerization of IBV nucleoprotein (NP) forms the viral ribonucleoprotein (vRNP), which is required for viral RNA synthesis. ISGylated IBV NP acts as a dominant-negative inhibitor of the oligomerization of unmodified NP, which restricts viral RNA synthesis and reduces IBV replication62. The HPV capsid protein L1 can also be ISGylated and then incorporated into viral particles. Both the number and infectivity of particles that have incorporated ISGylated L1 protein were found to be decreased, possibly owing to alterations in the geometry of the viral capsid54.

In addition to disrupting viral replication, ISGylation of viral proteins can dampen the host innate immune response. The ISGylation of NS1/A disrupted its ability to interact with components of the interferon response, such as PKR, U6 snRNA and dsRNA, limiting the ability of NS1/A to disrupt the innate immune response56. ISGylation also inhibited human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) gene expression and virion release. HCMV pUL26 is known to inhibit tumour necrosis factor-α (TNFα)-induced nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) activation63. It was shown that the HCMV pUL26 protein forms both covalent and non-covalent interactions with ISG15. ISGylation of pUL26 altered pUL26 stability and inhibited its ability to suppress NF-κB signalling64. Therefore, the ISGylation of viral proteins can also interfere with the viral modulation of the host immune response.

Altogether, these examples illustrate the ability of ISGylation of viral proteins to reduce the efficiency and quality of viral progeny production and to limit the ability of viral proteins to regulate the host immune response.

Inhibition of virus egress

Several studies have found that ISG15 can impact virus egress. In these examples, it is not the ISGylation of viral proteins but rather the modification of host proteins that are required for viral release that are impacted by ISG15 (Fig. 3).

The first evidence of ISG15 inhibiting virus release came from studies on HIV-1 replication. Co-transfection of a plasmid expressing ISG15 with HIV-1 proviral DNA inhibited the release of HIV-1 but had no impact on HIV-1 protein production65. Expression of ISG15 inhibited the mono-ubiquitylation of the HIV-1 Gag polyprotein and disrupted the interaction between Gag and the host tumour susceptibility gene 101 protein (TSG101), both of which are required for HIV-1 budding and release. Recent studies also found that the transport of IAV haemagglutinin (HA) to the cell surface in a semi-intact cell system was inhibited by the ISGylation of TSG101. In this study, HA transport was restored when samples were treated with deISGylases such as USP18 or the ovarian tumour domain (OTU)-containing L protein of Crimean–Congo haemorrhagic fever virus (CCHFV)66. A recent study further indicated that ISG15 conjugation decreases the number of multivesicular bodies (MVBs) and impairs exosome secretion by triggering the aggregation and degradation of MVB proteins by lysosomes, including TSG101 (ref.67).

ISG15 was also shown to inhibit budding and release of Ebola virus-like particles (VLPs) and avian sarcoma leukosis virus (ASLV). Release of Ebola VLPs requires the ubiquitylation of the viral matrix protein VP40, which is mediated by host ubiquitin protein ligase NEDD4 (ref.68). ISG15, when co-expressed with VP40, inhibited Ebola VLP release. ISG15 inhibited the activity of NEDD4 and blocked the ubiquitylation of VP40 and the interaction between NEDD4 and ubiquitin E2 conjugating enzymes, preventing ubiquitin from being transferred to NEDD4 (refs39,69). Interestingly, a recent study found that ITCH, another E3 ubiquitin ligase, also interacts with VP40 to regulate viral budding via an identical protein domain that is used by NEDD4. Whether the anti-budding function of ISG15 extends to ITCH ligases as well remains unknown70. ISG15 also inhibited ASLV VLP release by inhibiting the recruitment of the host ATPase vacuolar protein sorting-associated protein 4A (VPS4A) to the endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT), which is required for ASLV budding71–73. This inhibition correlated with ISGylation of the host protein charged multivesicular body protein 5 (CHMP5), which is required for VPS4A recruitment. Therefore, ISG15 is able to limit the replication of some viruses through covalent and non-covalent modifications of host proteins that are involved in protein sorting and transport pathways.

Modulation of viral latency

Recent studies have implicated ISG15 in the regulation of viral latency. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) is the causative agent of Kaposi's sarcoma, the most common HIV/AIDS-associated cancer worldwide. Transcriptional analysis of KSHV-infected primary human oral fibroblasts identified a series of strongly induced ISGs, including ISG15. Knockdown of ISG15 expression with small interfering RNA (siRNA) in these latently infected cells increased the expression of viral lytic genes and increased virion release, implicating ISG15 in the maintenance of KSHV latency74. One proposed mechanism for this was through the regulation of specific KSHV microRNAs that are known to modulate KSHV latency74. In a second study, KSHV infection was reactivated in primary effusion lymphoma cells by various means, and both ISG15 and ISG15 conjugate levels were found to be increased, along with activation of the type I interferon system75. Knockdown of either ISG15 or the E3 ligase HERC5 resulted in an increase in KSHV reactivation and an increase in the production of infectious virus75. These results suggest that ISG15 conjugation modulates both KSHV replication and reactivation from viral latency.

Indirect effects of ISG15 on viral infection

In addition to direct effects on viral replication, recent studies have also found that ISG15 influences the host response by functioning as an immunomodulatory protein, regulating the host damage and repair response during viral infection and modulating host signalling pathways that can indirectly limit or alter viral pathogenesis. In some cases, these actions are mediated by ISGylation of target proteins, and more recently, it has been found that unconjugated ISG15 can mediate these effects.

Immunomodulatory functions of ISG15

Early reports noted that ISG15 could be released from cells and that recombinant ISG15 could stimulate IFNγ production. This was recently confirmed in a study of individuals with ISG15 deficiency that presented with increased susceptibility to mycobacterial infection5 (Box 1). In this study, the production of IFNγ by NK cells and lymphocytes that was induced by ISG15 was increased when the cells were co-stimulated with IL-12. Earlier studies also implicated that the cytokine activity of ISG15 drives NK cell proliferation, dendritic cell maturation and neutrophil recruitment. Recently, LFA1 was identified as a cell surface receptor for ISG15, and its binding to this receptor mediated the release of IFNγ and IL-10 from cells pretreated with IL-12 (ref.37). Whether LFA1 also contributes to other activities that have been attributed to ISG15 and whether the cytokine-like activity of ISG15 has a role during viral infection remain to be elucidated.

The unconjugated form of ISG15 has also been shown to counteract the inflammatory response during viral infection. During chikungunya infection, neonatal mice lacking ISG15 were found to be more susceptible to viral infection; however, this protection was independent of UBE1L-mediated ISGylation, and the increased lethality observed in the Isg15−/− mice was not due to an increase in viral titres31. Instead, the infected Isg15−/− mice developed an exaggerated immune response, displaying a significant increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines compared with wild-type or Ube1−/−mice31. Preliminary data indicate that death of the animals occurred in a manner that is consistent with a cytokine storm, and the survival of Isg15−/− mice could be prolonged when they were treated with TNFα-blocking antibody before infection76. In a separate study, ISG15-deficient mice were more susceptible to vaccinia virus infection and produced elevated levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-6 (ref.77). Taken together, these findings suggest that unconjugated ISG15 negatively regulates the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines during certain viral infections. It is still unclear whether these effects are mediated by intracellular or extracellular unconjugated ISG15 and which cell types are responsible for the increased cytokine production.

Regulation of host damage and repair pathways

The host response to a pathogen includes the upregulation of genes that limit pathogen replication (disease resistance) and protect the host from tissue damage, independent of controlling pathogen burden (disease tolerance)78. Recent findings support a role for ISG15 in the regulation of disease tolerance. In a mouse model of IAV and Sendai virus infection (SeV), ISG15 protected mice from virus-induced lethality47,79. Both in vitro and in vivo analyses revealed that the ISG15-mediated protection neither restricted viral replication nor modulated cytokine or chemokine production within the lung tissue. Instead, it was determined that ISG15 regulated the damage and/or repair of the respiratory epithelium following infection50. To date, this is the only evidence that the ISG15 pathway regulates disease tolerance during viral infection. However, recent studies identified pathways that are targeted by ISG15 and are involved in homeostasis, including the regulation of apoptosis and autophagy23,40,51,80,81. It will be important to determine if ISG15 facilitates disease tolerance by coordinating these pathways.

Modulation of host signalling pathways that impact viral infection

Proteomic studies have identified hundreds of host proteins that are ISGylated upon interferon stimulation18,19. Many of these are ISGs that are involved in the regulation of the innate immune response, including signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1), JAK1 (ref.82), RIG-I, interferon-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 1 (IFIT1)19, PKR and interferon-regulated resistance GTP-binding protein MxA (also known as Mx1)19. For a subset of these potential targets, modification has been validated, and the impact of ISGylation on their function has been investigated in detail (Table 1).

PKR is an interferon-induced protein that binds to dsRNA and, once activated, can phosphorylate the eukaryotic translation initiation factor eIF2α and inhibit cellular mRNA translation. PKR is ISGylated on lysines 69 and 159 after interferon or LPS stimulation83. ISGylated PKR exhibited an RNA-independent, constitutive activation that resulted in decreased protein synthesis83. However, it remains unclear whether ISGylation of PKR results in direct antagonism of virus replication.

The ISGylation of interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) and STAT1 interferes with ubiquitylation and subsequent degradation of these proteins79,84. IRF3 is a transcription factor that, once phosphorylated, moves from the cytoplasm to the nucleus to form a complex with CREB-binding protein (CREBBP) and activates the transcription of IFNα, IFNβ and additional ISGs. STAT1 is a member of the STAT protein family and functions as a transcription factor involved in the upregulation of genes induced by type I, II and III interferons. During SeV infection, IRF3 is ISGylated, and this inhibits the interaction between IRF3 and peptidyl-prolyl cis–trans isomerase NIMA-interacting 1 (PIN1), preventing the ubiquitylation and subsequent degradation of IRF3 (ref.79). Similarly, STAT1 is ISGylated in human cells82, which was found to maintain the levels of phosphorylated, activated STAT1 and downstream signalling. In both cases, the result of ISGylation is a more robust interferon response that limits viral replication. Recent studies of individuals with inherited ISG15 deficiency who displayed signs of type I interferon autoinflammation4,5 (Box 1) revealed that intracellular unconjugated ISG15 has immunomodulatory functions. In vitro characterization of cells isolated from these patients showed elevated type I interferon secretion and a hyperresponsiveness to type I interferon stimulation, including prolonged STAT1 and STAT2 phosphorylation. This was attributed to the low level of USP18 protein expression in these cells4. This defect could be restored by either wild-type or non-conjugatable ISG15, implicating non-covalent interactions between ISG15 and USP18. Mechanistic studies demonstrated that ISG15 binds to and stabilizes USP18 by preventing its ubiquitylation by S-phase kinase-associated protein 2 (SKP2)4 (Fig. 2). These results suggest that human intracellular unconjugated ISG15 is crucial for USP18-mediated downregulation of type 1 interferon signalling during viral infections. Consistent with this, human ISG15-deficient cells primed with interferons displayed prolonged ISG expression, which in some cases provided resistance to viral infection53. Interestingly, this enhanced type I interferon signalling has not been observed in mice (Box 1), raising interesting questions about the divergent function of ISG15 between species.

The regulation of interferon signalling by ISG15 and USP18 also contributes to the unexpected proviral activity for ISG15 that has been associated with chronic viral hepatitis. The expression of ISG15 and members of its conjugation cascade was found to be upregulated in individuals persistently infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV) who had failed treatment with IFNα85–87. Consistent with this, in vitro studies also showed that knockdown of ISG15 increased the sensitivity of HCV-infected cells to IFNα or IFNα–ribavirin therapies87,88. Mechanistic studies found that ISG15 expression was induced under these conditions by unphosphorylated interferon-stimulated gene factor 3 (U-ISGF3)89 (Fig. 1). U-ISGF3 is a tripartite transcription factor composed of interferon regulatory factor 9 (IRF9) and unphosphorylated STAT1 and STAT2. The level of U-ISGF3 is significantly increased in response to IFNλ and IFNβ during chronic HCV infection and sustains the expression of ISG15 and a subset of ISGs, which restricts HCV replication. The sustained ISG15 expression led to stabilization of USP18 levels, which decreased signalling through the type I interferon receptor84,89. Therefore, the regulation of interferon signalling that is mediated by ISG15 contributes to the maintenance of chronic HCV.

ISG15 can also modulate the metabolic activities and function of macrophages during the host antiviral response52. Cells lacking ISG15 were deficient in mitochondrial respiration, oxidative phosphorylation, mitophagy and reactive oxygen species production52. In the absence of ISG15, interferon-primed, bone marrow-derived macrophages failed to produce nitric oxide and arginase 1, molecules that limit vaccinia virus infection. Although the detailed molecular mechanism remains unclear, this finding demonstrates that, in this cell type, ISG15 can also modulate cellular metabolic activities.

The ISG15 pathway has also been implicated in non-viral infectious diseases (Box 2), non-infectious diseases, such as cancers, and other cellular functions, such as the regulation of interferon-induced apoptosis23. The identification of further host proteins that are modified by or interact with ISG15 may provide important insights into the function of the ISG15 pathway.

Box 2 | Role of ISG15 in non-viral infections.

Although extensive work has evaluated the function of ubiquitin-like protein ISG15 during viral infection, recent studies have also highlighted the potential importance of ISG15 in the regulation of non-viral infections.

Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium

Studies of mice lacking the deconjugating enzyme Ubl carboxy-terminal hydrolase 18 (USP18) were the first to explore the role of the ISG15 pathway in regulating the host response to bacterial infection. Mice deficient in USP18 were found to be more susceptible to infection with Salmonella enterica subsp. serovar Typhimurium. However, this phenotype was due to a lack of regulation of type I interferon signalling by USP18, rather than a lack of deISGylase activity, as mice carrying a knockout of both USP18 and ISG15 did not show improved survival with S. Typhimurium challenge116. The infection of Isg15−/− cells with S. Typhimurium revealed no differences in bacterial growth compared with wild-type cells12.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

Type I interferons are thought to exacerbate tuberculosis; therefore, it was hypothesized that ISG15 deficiency would be protective117–122. However, survival studies have yielded conflicting results. Initial studies found that mice lacking ISG15 displayed increased susceptibility to Mycobacterium tuberculosis, displaying increased lethality after 150 days of infection5. Whether this increased susceptibility was due to increases in bacterial burden, more severe pathology or dependence upon ISG15 conjugation was not explored. In a separate study, no significant difference in lethality was observed between wild-type and ISG15-deficient mice123. Isg15−/− mice had a lower bacterial burden in their spleens and lungs during acute (day 7) and early chronic disease (day 77), indicating that ISG15 was detrimental at these time points. Therefore, the effects of ISG15 on M. tuberculosis infection in mice vary depending upon the time point and readout being analysed.

Individuals who have a mutation in ISG15 (resulting in ISG15 deficiency) display Mendelian susceptibility to mycobacterial disease5. Whole blood leukocytes isolated from these patients were found to produce decreased levels of interferon-γ (IFNγ) compared with controls after stimulation with either bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccine alone or in combination with interleukin-12 (IL-12), which could be partially rescued with recombinant ISG15 (ref.5). Subsequent studies also found that individuals lacking ISG15 are more responsive to type I interferon owing to the dysregulation of USP18 (ref.4) (Box 1). As an increase in type I interferon signalling has been correlated with an increased severity of mycobacterial infections124,125, it is likely that both mechanisms contribute to the observed increased susceptibility.

Listeria monocytogenes

The expression of ubiquitin-like protein ISG15 and ISGylation is induced during Listeria monocytogenes infection by a cytosolic DNA-sensing pathway that is dependent upon stimulator of interferon genes protein (STING), serine/threonine-protein kinase TBK1, interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) and IRF7 (ref.12). ISG15 is protective against L. monocytogenes challenges in a conjugation-dependent manner both in vitro and in vivo, with cells and mice displaying increased bacterial replication in the absence of ISG15. Studies of ISG15 overexpressing cells revealed that the secretion of IL-6 and IL-8 was enhanced by both tumour necrosis factor-α (TNFα) and L. monocytogenes infection, providing a potential mechanism by which ISGylation could counteract L. monocytogenes infection12. The induction of ISG15 by DNA-sensing pathways, independent of type I interferons, and its potential regulation of cytokine signalling suggest that ISG15 has a broader role in the host response to pathogens, including bacterial and fungal infection.

Candida albicans

Recently, the impact of ISG15 on fungal infections was explored in a mouse model of fungal keratitis. Candida albicans was shown to induce the expression of ISG15, ubiquitin-activating enzyme E1 homologue (UBE1L), ubiquitin/ISG15-conjugating enzyme E2 L6 (UBCH8; also known as UBE2L6) and E3 ISG15–protein ligase (HERC5) in corneal epithelial cells (CECs), resulting in the upregulation of ISGylation126. Knockdown of Isg15 in CECs that were exposed to C. albicans following ocular scarification increased the severity of keratitis. The CECs released ISG15 into the cell culture media following C. albicans exposure, and treatment with recombinant ISG15 increased the expression of IL-1RA and CXC-chemokine ligand 10 (CXCL10) and protected the cells from damage, suggesting that in this model, ISG15 functions as an immunomodulatory protein that protects against C. albicans126.

To date, the role of ISG15 in non-viral infections is largely immunomodulatory. Whether ISG15 inhibits bacterial or fungal replication directly and whether any of these pathogens have evasion strategies that target ISG15 or the ISG15 conjugation pathway remain unknown.

Viral evasion strategies

Viruses acquired different immune-evasion strategies to counteract the ISG15 pathway, highlighting the importance of ISG15 in the host antiviral response (Fig. 4).

Influenza B virus NS1

The NS1 protein of IBV (NS1/B) was the first viral protein identified to have immune-evasion activity against the ISG15 pathway11. Initially, NS1/B was found to only bind human and primate ISG15 and inhibit its interaction with the E1 enzyme UBE1L, thereby inhibiting IFNβ-induced ISGylation90,91. However, recent studies in which a recombinant IBV was engineered to encode an NS1/B protein that is defective in ISG15 binding revealed that NS1/B does not inhibit ISGylation in IBV-infected cells. Instead, NS1/B binds to and sequesters ISGylated viral proteins, particularly ISGylated viral NP62. This prevents the incorporation of ISGylated NPs into vRNPs, which was previously shown to inhibit viral RNA synthesis.

Vaccinia virus E3

The vaccinia virus E3L protein inhibits ISG15 conjugation to promote viral replication. In in vitro assays, the vaccinia virus E3L protein binds to both human and mouse ISG15 and antag-onizes ISGylation77. Infection of mouse embryonic fibroblasts with a ΔE3L mutant vaccinia virus resulted in ISG15 conjugate formation and reduced viral replication in wild-type cells compared with ISG15-deficient cells. Isg15−/− mice exhibited increased lethality compared with wild-type mice when infected with the ΔE3L mutant vaccinia virus. The mutant virus also exhibited a ~25-fold increase in virus replication in Isg15−/− cells compared with wild-type cells92. These results suggest that ISG15 conjugation restricts vaccinia virus replication and that the E3L protein functions as an immune-evasion effector.

Deconjugating proteases

Several viruses, especially members of the order Nidovirales, which includes the coronaviruses, encode enzymes capable of deconjugating ubiquitin and ISG15 from target proteins to antagonize host responses. CCHFV, porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PPRSV) and equine arteritis virus (EAV) encode an L protein that contains OTU-containing proteases. These proteins have been shown to reduce the total pool of both ubiquitin and ISG15 conjugates in a cell93. Coronaviruses, including severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus (SARS-CoV), Middle East respiratory syndrome-coronavirus (MERS-CoV), mouse hepatitis virus strain 3 (MHV-3) and human coronavirus-NL63 (HCoV-NL63), encode papain-like proteases (PLPs) that also deubiquitylate and deISGylate target proteins94–97. The pharmacological inhibition of the PLP2 enzyme in vitro led to an increase of protein ISGylation and decreased viral replication during MHV-3 replication98. A recombinant Sindbis virus system has been used with both CCHFV and SARS-CoV to evaluate the impact of the deISGylating activity of these proteases on viral pathogenesis93,99. For example, co-expression of either the CCHFV L protein OTU domain or the SARS-CoV PLpro with ISG15 by a recombinant Sindbis virus abolished the protection provided by the expression of ISG15 alone during infection of Ifnar−/− mice. Mutation of the catalytic cysteine residue of PLpro or addition of a PLpro inhibitor blocked de-ISGylation in infected cells, and the administration of a PLpro inhibitor protected these mice from lethal infection, demonstrating the efficacy of a coronavirus protease inhibitor in a mouse model. Although these examples highlight another potential mechanism of circumventing ISG15, direct evidence for ISG15 antagonism by these proteins during viral infection remains to be demonstrated. Recent biochemical and structural studies have revealed that viral deconjugating enzymes have different specificities for the various forms of polyubiquitin chains and bind to ISG15 in a species-specific manner100–106. Therefore, the biological consequences of these different viral proteases will vary depending upon the virus and host being studied107.

HCMV IE1 and puL26

ISG15 conjugation inhibits HCMV growth by reducing viral gene expression and inhibiting virion release64. To overcome this, HCMV has evolved multiple countermeasures. The major immediate-early protein IE1 reduces ISG transcription by sequestering STAT2 and preventing interferon-sensitive response element (ISRE) binding. Ectopic expression of HCMV IE1 limited ISG15 protein conjugation, presumably through the decreased expression of components of the ISG15 conjugation machinery, such as HERC5 (ref.108). An IE1 deletion virus robustly induced interferon signalling, including the expression of ISG15 and ISG15 conjugates64. In addition, p21 and p27, two tegument proteins encoded by the gene pUL26 that are involved in virion stability and downregulation of NF-κB signalling, non-covalently interact with ISG15, UBE1L and HERC5 (ref.64). The expression of UL26–p21 reduced the levels of ISG15 conjugates in cells co-transfected with ISG15 and the conjugating enzymes. Interestingly, as discussed earlier, pUL26 itself is a target of ISG15 conjugation. ISGylation of pUL26 alters its stability and inhibited its ability to suppress NF-κB signalling. In the absence of pUL26, HCMV growth is more sensitive to IFNβ treatment.

KSHV vIRF1

ISG15 conjugation limits KSHV replication and modulates viral latency74,75. KSHV vIRF1 protein, which is expressed upon Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) activation and interferon induction, interacts with ISG15 E3 ligase HERC5. Interaction between vIRF1 and HERC5 decreased the levels of TLR3-induced ISG15 conjugation and cellular IRF3, suggesting that vIRF1 affects ISG15 conjugation and the interferon response, which could contribute to effective KSHV replication75.

Taken together, these examples highlight the convergent evolution of viral proteins that antagonize the ISG15 pathway, providing further support for the importance of this pathway in viral pathogenesis.

Conclusions

ISG15 has been shown to have an important role during infection for a broad range of viruses. Recent studies have advanced our understanding by elucidating how ISG15 antagonizes viral replication during acute and latent infections; identifying immune-evasion strategies; beginning to characterize how ISG15 alters disease pathogenesis, including its ability to limit tissue damage and to modulate human type I interferon signalling; and identifying the first cell surface receptor for unconjugated ISG15, which can regulate cytokine release. The recent identification of ISG15-deficient patients5 and the subsequent characterization of ISG15 regulation of type I interferon signalling have shed light on the complexity of this pathway and have prompted a re-evaluation of the role of ISG15 (ref.4). There are still many important questions that will need to be answered for this pathway to be fully understood.

How does protein ISGylation reshape the global post-translational modification profile of infected or immune cells in response to pathogen invasion? How ISGylation modulates viral proteins, viral replication and host homeostasis is still poorly understood. The ISG15 conjugation system has been intimately tied to protein translation, but it also results in the targeted modification of proteins, as outlined above. How the modification of a small fraction of the total pool of a protein can affect its overall function within a cell is still unclear. Possibilities include the ability of ISGylated proteins to disrupt oligomerization of proteins or to alter the cellular localization of proteins. Another intriguing possibility is that ISGylation could serve as a warning sign to the cell that it is infected. Recent studies have shown that ISG15 can interact with the autophagy pathway, which is known to regulate a variety of processes, including protein degradation, antigen presentation, cytokine signalling and cell death40,41,51. ISGylated proteins, through their interaction with autophagy pathways or other cellular pathways yet to be determined, could function as a danger signal, activating host responses that could serve to limit the infection and protect the host. The application of novel proteome analyses12,109 will be crucial for determining the conjugation preference, scope and potential biological outcomes of protein ISGylation. Although initial proteomic studies to identify ISGylated proteins have been performed in interferon-stimulated cells, this analysis will need to be expanded to different cell types and viruses.

What role does extracellular ISG15 have in the host response to viruses? Utilizing tools that inhibit ISG15 conjugation has allowed researchers to begin to decipher whether phenotypes that are attributed to ISG15 deficiency are conjugation-dependent or independent. However, tools that differentiate between the functions of unconjugated extracellular and intracellular ISG15 are lacking. The recent identification of LFA1 as an ISG15 receptor may facilitate the biological characterization of extracellular ISG15.

How does intracellular, unconjugated ISG15 modulate cellular pathways to limit pathogen burden or damage during infection? In vivo studies have provided evidence that it functions during viral pathogenesis to limit tissue damage, independent of its ability to directly antagonize viral replication50. The ability of ISG15 to non-covalently bind to USP18 and to regulate type I interferon signalling in humans indicates that ISG15 may interact with other unidentified intracellular proteins, independent of conjugation, to regulate additional cellular processes. Uncovering the binding partners will be instrumental in understanding its molecular mechanism of action.

In recent years, ISG15 has been used as a marker of antiviral treatment110,111 and as an immune adjuvant to enhance T cell antitumour immunity112. Further characterization of the ISGylation pathway could help to identify druggable targets, offering new opportunities to intervene in the progression of many diseases.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the members of the Lenschow laboratory for their critical reading of the manuscript during its preparation. The authors gratefully acknowledge support from the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) R01 AI080672 and Pew Charitable Trusts. Y.P. is funded through a Children Discovery Institute postdoctoral fellowship and the NIH postdoctoral training grant T32 CA009547.

Glossary terms

- Ubiquitin

A small regulatory protein that can be added to a substrate protein by a process known as ubiquitylation and can alter the function of the substrate protein through degradation, localization and protein–protein interactions.

- Ubiquitin-like modifiers

(Ubls). Small regulatory proteins that possess ubiquitin folds and are often conjugated onto a target protein similar to ubiquitin to alter function.

- Genotoxic stressors

Agents that damage the genetic information within a cell, causing mutations or diseases.

- Proteasome-mediated degradation

A cellular process to regulate the concentration of proteins and to degrade misfolded proteins by proteolysis, a chemical reaction that breaks peptide bonds.

- Leader signal

A short peptide present at the amino terminus of newly synthesized proteins that are destined for the secretory pathway.

- Secretory lysosomes

Dual-function organelles that could be used as a lysosome for degradation and hydrolysis and for storage of secretory proteins within the cell.

- RIG-I

A double-stranded RNA helicase enzyme that functions as a cytosolic pattern-recognition receptor that recognizes short double-stranded or single-stranded RNA from viruses and triggers an antiviral response.

- Usp18-knock-in mice

Mice in which the endogenous USP18 gene was replaced with a USP18 gene mutated so that it maintains its ability to bind to and inhibit signalling through the type I interferon receptor but its de-ISGylating capacity is lost, resulting in the accumulation of ISG15 conjugates.

- Protein kinase R

(PKR). An interferon-induced, dsRNA-activated protein kinase that phosphorylates the eukaryotic translation initiation factor (eIF2α) in response to dsRNA and cellular stress, including viral infections.

- Ovarian tumour domain

(OTU domain). A domain that is a shared protein region of a family of deubiquitylating proteolytic enzymes involved in processing of ubiquitin precursors.

- Exosome secretion

A cellular secretion pathway mediated by the release of small membrane vesicles from multivesicular endosomes.

- Viral latency

A type of persistent viral infection in which the pathogenic virus lies dormant without killing infected cells until it is reactivated by certain stimuli.

- Aicardi–Goutières syndrome

(AGS). A rare, early-onset childhood inflammatory disorder characterized by elevated levels of type I interferons that results in skin and central nervous system manifestations.

- Pathogen burden

The number of pathogens in an infected host that require the immune system for eradication.

- Ribavirin

An antiviral medication used to treat hepatitis C, respiratory syncytial virus and other viral infections.

- Mitophagy

A type of autophagy in which a defective and/or dysfunctional mitochondrion is selectively degraded by the lysosome.

- Interferon-sensitive response element

(IRSE). A specific nucleotide sequence located in the promoters of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) that can bind to interferon stimulated gene factor 3 (ISGF3) or other transcriptional complexes upon type I interferon stimulation to initiation transcription of ISGs.

Author contributions

Y.P. researched data for the article. Y.P. and D.J.L. substantially contributed to discussion of content, wrote the article and reviewed and edited the manuscript before submission.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Schneider WM, Chevillotte MD, Rice CM. Interferon-stimulated genes: a complex web of host defenses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2014;32:513–545. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Der SD, Zhou A, Williams BR, Silverman RH. Identification of genes differentially regulated by interferon alpha, beta, or gamma using oligonucleotide arrays. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:15623–15628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loeb KR, Haas AL. The interferon-inducible 15-kDa ubiquitin homolog conjugates to intracellular proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:7806–7813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang X, et al. Human intracellular ISG15 prevents interferon-alpha/beta over-amplification and auto-inflammation. Nature. 2015;517:89–93. doi: 10.1038/nature13801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bogunovic D, et al. Mycobacterial disease and impaired IFN-gamma immunity in humans with inherited ISG15 deficiency. Science. 2012;337:1684–1688. doi: 10.1126/science.1224026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Korant BD, Blomstrom DC, Jonak GJ, Knight E., Jr. Interferon-induced proteins. Purification and characterization of a 15,000-dalton protein from human and bovine cells induced by interferon. J. Biol. Chem. 1984;259:14835–14839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haas AL, Ahrens P, Bright PM, Ankel H. Interferon induces a 15-kilodalton protein exhibiting marked homology to ubiquitin. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:11315–11323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blomstrom DC, Fahey D, Kutny R, Korant BD, Knight E., Jr. Molecular characterization of the interferon-induced 15-kDa protein. Molecular cloning and nucleotide and amino acid sequence. J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:8811–8816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dao CT, Zhang DE. ISG15: a ubiquitin-like enigma. Front. Biosci. 2005;10:2701–2722. doi: 10.2741/1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Narasimhan J, et al. Crystal structure of the interferon-induced ubiquitin-like protein ISG15. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:27356–27365. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502814200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yuan W, Krug RM. Influenza B virus NS1 protein inhibits conjugation of the interferon (IFN)-induced ubiquitin-like ISG15 protein. EMBO J. 2001;20:362–371. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.3.362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Radoshevich L, et al. ISG15 counteracts Listeria monocytogenes infection. eLife. 2015;4:e06848. doi: 10.7554/eLife.06848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malakhova O, Malakhov M, Hetherington C, Zhang DE. Lipopolysaccharide activates the expression of ISG15-specific protease UBP43 via interferon regulatory factor 3. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:14703–14711. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111527200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pitha-Rowe I, Hassel BA, Dmitrovsky E. Involvement of UBE1L in ISG15 conjugation during retinoid-induced differentiation of acute promyelocytic leukemia. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:18178–18187. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309259200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu M, Hummer BT, Li X, Hassel BA. Camptothecin induces the ubiquitin-like protein, ISG15, and enhances ISG15 conjugation in response to interferon. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2004;24:647–654. doi: 10.1089/jir.2004.24.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Potter JL, Narasimhan J, Mende-Mueller L, Haas AL. Precursor processing of pro-ISG15/UCRP, an interferon-beta-induced ubiquitin-like protein. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:25061–25068. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.35.25061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang D, Zhang DE. Interferon-stimulated gene 15 and the protein ISGylation system. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2011;31:119–130. doi: 10.1089/jir.2010.0110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giannakopoulos NV, et al. Proteomic identification of proteins conjugated to ISG15 in mouse and human cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005;336:496–506. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.08.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao C, Denison C, Huibregtse JM, Gygi S, Krug RM. Human ISG15 conjugation targets both IFN-induced and constitutively expressed proteins functioning in diverse cellular pathways. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:10200–10205. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504754102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu M, Li XL, Hassel BA. Proteasomes modulate conjugation to the ubiquitin-like protein, ISG15. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:1594–1602. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208123200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Desai SD, et al. Elevated expression of ISG15 in tumor cells interferes with the ubiquitin/26 S proteasome pathway. Cancer Res. 2006;66:921–928. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fan JB, et al. Identification and characterization of a novel ISG15-ubiquitin mixed chain and its role in regulating protein homeostasis. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:12704. doi: 10.1038/srep12704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jeon YJ, et al. ISG15 modification of filamin B negatively regulates the type I interferon-induced JNK signalling pathway. EMBO Rep. 2009;10:374–380. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malakhov MP, Malakhova OA, Kim KI, Ritchie KJ, Zhang DE. UBP43 (USP18) specifically removes ISG15 from conjugated proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:9976–9981. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109078200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Basters A, et al. Structural basis of the specificity of USP18 toward ISG15. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2017;24:270–278. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Malakhova OA, et al. UBP43 is a novel regulator of interferon signaling independent of its ISG15 isopeptidase activity. EMBO J. 2006;25:2358–2367. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]