Abstract

Background

Many surgical approaches are available to treat varicose veins secondary to chronic venous insufficiency. One of the least invasive techniques is the ambulatory conservative hemodynamic correction of venous insufficiency method (cure conservatrice et hémodynamique de l'insuffisance veineuse en ambulatoire (CHIVA)), an approach based on venous hemodynamics with deliberate preservation of the superficial venous system. This is an update of the review first published in 2013.

Objectives

To compare the efficacy and safety of the CHIVA method with alternative therapeutic techniques to treat varicose veins.

Search methods

The Trials Search Co‐ordinator of the Cochrane Peripheral Vascular Diseases Group searched the Specialised Register (April 2015), the Cochrane Register of Studies (2015, Issue 3) and clinical trials databases. The review authors searched PubMed (April 2015). There was no language restriction. We contacted study authors to obtain more information when necessary.

Selection criteria

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that compared the CHIVA method versus any other treatments. Two review authors independently selected and evaluated the studies. One review author extracted data and performed the quantitative analysis.

Data collection and analysis

Two independent review authors extracted data from the selected papers. We calculated the risk ratio (RR), mean difference (MD), the number of people needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB), and the number of people needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome (NNTH), with 95% confidence intervals (CI) using Review Manager 5.

Main results

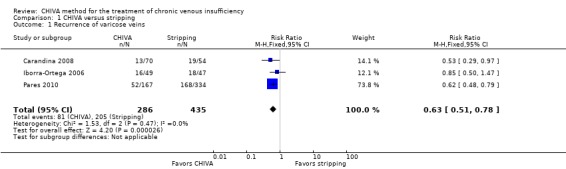

No new studies were identified for this update. We included four RCTs with 796 participants (70.5% women). Three RCTs compared the CHIVA method with vein stripping, and one RCT compared the CHIVA method with compression dressings in people with venous ulcers. We judged the quality of the evidence of the included studies as low to moderate due to imprecision caused by the low number of events and because the studies were open. The overall risk of bias across studies was high because neither participants nor outcome assessors were blinded to the interventions. The primary endpoint, clinical recurrence, pooled between studies over a follow‐up of 3 to 10 years, showed more favorable results for the CHIVA method than for vein stripping (721 people; RR 0.63; 95% CI 0.51 to 0.78; I2 = 0%, NNTB 6; 95% CI 4 to 10) or compression dressings (47 people; RR 0.23; 95% CI 0.06 to 0.96; NNTB 3; 95% CI 2 to 17). Only one study reported data on quality of life (presented graphically) and these results significantly favored the CHIVA method.

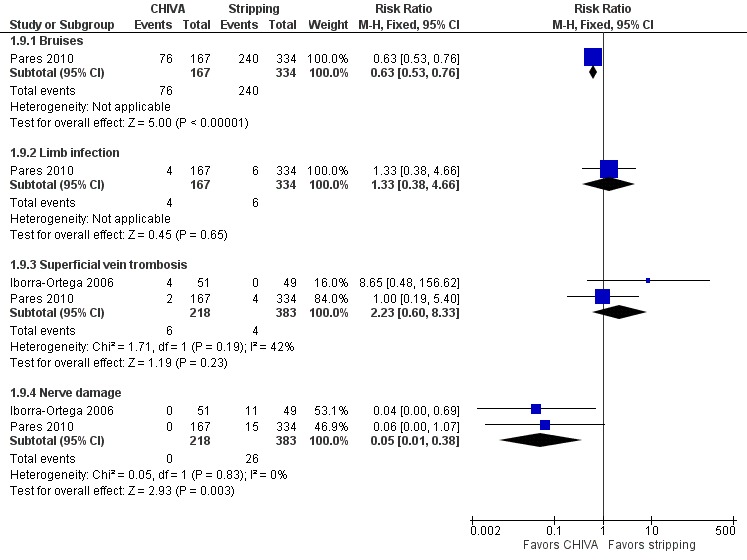

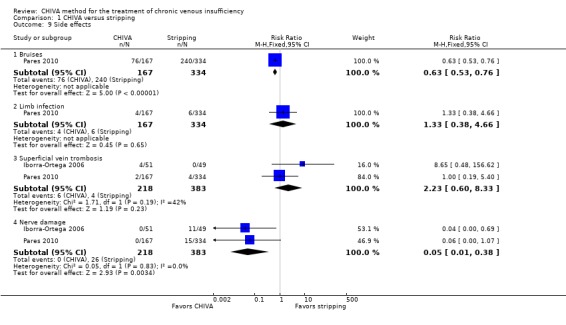

The vein stripping group had a higher risk of side effects than the CHIVA group; specifically, the RR for bruising was 0.63 (95% CI 0.53 to 0.76; NNTH 4; 95% CI 3 to 6) and the RR for nerve damage was 0.05 (95% CI 0.01 to 0.38; I2 = 0%; NNTH 12; 95% CI 9 to 20). There were no statistically significant differences between groups regarding the incidence of limb infection and superficial vein thrombosis.

Authors' conclusions

The CHIVA method reduces recurrence of varicose veins and produces fewer side effects than vein stripping. However, we based these conclusions on a small number of trials with a high risk of bias as the effects of surgery could not be concealed and the results were imprecise due to low number of events. New RCTs are needed to confirm these results and to compare CHIVA with approaches other than open surgery.

Plain language summary

CHIVA method for the treatment of varicose veins

Background

Chronic venous insufficiency (CVI) is a disorder in which veins fail to pump blood back to the heart adequately. It can cause varicose veins, skin ulcers, and superficial or deep vein thrombosis in the legs. The ambulatory conservative hemodynamic correction of venous insufficiency (CHIVA) method is a minimally invasive surgical technique to treat varicose veins. The aim of the CHIVA treatment is to eliminate the venous‐venous shunts by disconnecting the escape points, preserving the saphenous vein and normal venous drainage of the superficial tissues of the limb.

Key results

This review evaluated the effectiveness and safety of the CHIVA method in CVI and included four randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with 796 participants. The evidence is current up to April 2015. Three RCTs compared the CHIVA method with vein stripping, and one RCT compared the CHIVA method with compression dressings in people with venous ulcers. The results showed that the CHIVA method reduced recurrence of varicose veins compared to vein stripping. However, no differences in clinical improvement or cosmetic results, as perceived by participants and investigators, were detected between groups. Quality of life was only assessed in one study and the results favored the CHIVA method. Regarding adverse effects, the CHIVA method showed a lower percentage of bruising and nerve injuries than vein stripping.

Quality of the evidence

Further studies are needed to confirm these conclusions since they are based on a small number of clinical trials with methodological limitations such as high risk of bias mainly because participants and outcome assessors were not blinded to the interventions and the results were imprecise due to low number of events.

Summary of findings

for the main comparison.

| CHIVA compared with stripping for varicose veins | ||||||

|

Patient or population: adults with varicose veins Settings: hospital Intervention: CHIVA Comparison: stripping | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Stripping | CHIVA | |||||

|

Recurrence of varicose veins (follow‐up: 60 months ‐ 10 years) |

Study population |

RR 0.63 (0.51 to 0.78) |

721 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ||

| 471 per 1000 | 297 per 1000 (240 to 368) | |||||

| Moderate6 | ||||||

| 383 per 1000 | 241 per 1000 (195 to 299) | |||||

|

Side effects ‐ bruises (follow‐up: 60 months) |

Study population5 |

RR 0.63 (0.53 to 0.76) |

501 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | ||

| 719 per 1000 | 453 per 1000 (381 to 546) | |||||

|

Side effects ‐ limb infection (follow‐up: 60 months) |

Study population5 |

RR 1.33 (0.38 to 4.66) |

501 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,3 | ||

| 18 per 1000 | 24 per 1000 (7 to 84) | |||||

|

Side effects ‐ superficial vein thrombosis (follow‐up: 60 months ‐ 5 years) |

Study population |

RR 2.23 (0.6 to 8.33) |

601 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 | ||

| 10 per 1000 | 23 per 1000 (6 to 83) | |||||

| Moderate6 | ||||||

| 6 per 1000 | 13 per 1000 (4 to 50) | |||||

|

Side effects ‐ nerve damage (follow‐up: 60 months ‐ 5 years) |

Study population |

RR 0.05 (0.01 to 0.38) |

601 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1,3,4 | ||

| 68 per 1000 | 3 per 1000 (1 to 26) | |||||

| Moderate6 | ||||||

| 135 per 1000 | 7 per 1000 (1 to 51) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 The studies were open: participants and assessors knew the intervention

2 The study was open: participants and assessors knew the intervention

3 There was imprecision due to low number of events

4 CHIVA method is unlikely to cause nerve damage. We have upgraded the quality of evidence for the large effect

5 Assumed risk is mean baseline risk from study population

6 Assumed risk is the median control group risk from studies in meta‐analysis

Background

Description of the condition

Chronic venous insufficiency (CVI) is a complex condition in which the veins do not efficiently return blood from the legs to the heart. CVI develops slowly and its complications often appear years or even decades after the onset of symptoms (Kurz 1999). Its origin is multifactorial and clinical manifestations are widely varied, ranging from dilated cutaneous veins and varicose veins, to edema, skin discoloration, and ulcers in advanced cases. The most common symptoms are pain, fatigue, heaviness, warmth and swelling of the leg, all of which are more intense when standing and under environmental conditions of heat and humidity (Vanhouette 1997). CVI can affect the superficial venous system or the deep venous system, or both, but the most common situation is involvement of the superficial venous system, the main manifestation of which is varicose veins (Table 4; Porter 1995).

1. CEAP clinical classification (C).

| Class | Clinical indication |

| 0 | No visible or palpable signs of venous disease |

| 1 | Telangiectases or reticular veins |

| 2 | Varicose veins |

| 3 | Edema |

| 4 | Skin changes ascribed to venous disease (e.g. pigmentation, venous eczema, lipodermatosclerosis) |

| 5 | Skin changes as defined here with healed ulceration |

| 6 | Skin changes as defined here with active ulceration |

See Porter 1995.

The estimated prevalence of CVI varies depending on the criteria used. On the basis of varicose veins in the physical examination, prevalence has been estimated to range from 30% to 40% in the general adult population (Lee 2003), and to affect up to 50% of women (Carpentier 2004). If we consider the detection of reflux in the superficial venous system by hemodynamic study, prevalence can range from 9% in males to 15% in females (Allan 2000).

Treatment options for CVI have advanced greatly in recent years and involve both medical and surgical methods. The choice of therapy depends on the stage of development of the disease (Agus 2001), and options are often used in combination. Treatment of CVI in general and specific treatments for varicose veins do not cure the disease but they can prevent complications and improve signs and symptoms, even healing of ulcers in some cases. General treatment for CVI includes hygienic and postural measures (such as elevation of the legs or walking around to keep the muscle pump working) (Hamdan 2012), compression therapy (Nelson 2000; Nelson 2011; O'Meara 2009), topical treatment (Aziz 2011; Cullum 2010; Jull 2008; Kranke 2004; O'Meara 2010; Palfreyman 2006), and drug therapy (Martinez‐Zapata 2005; O'Meara 2010). Specific treatment for varicose veins includes sclerotherapy (Tisi 2006), laser therapy (Flemming 1999), radiofrequency ablation (Nesbitt 2011), and surgery (Rigby 2004).

Surgical treatment for varicose veins dates back to the early 20th century when Keller described removal of the saphenous vein through a metal loop in 1905 (Keller 1905) and Lofgren described endoluminal stripping in 1906 (Lofgren 1977). Two years later, Babcock used a vein‐extractor similar to that used today (Lofgren 1977). In 1966, Muller described ambulatory phlebectomy (Muller 1966). Such techniques, however, cannot totally prevent varicose vein recurrence (Blomgren 2004; Labropoulos 2005; Perrin 2000; Winterborn 2004), or remodeling of the venous network of subcutaneous tissue (Juan 2002).

The introduction of duplex scanning in the study of CVI has provided in vivo knowledge of venous hemodynamics (Franceschi 1988). It not only enables a complete morphological study, but also allows mapping of the hemodynamics of the venous system, providing precise information on any changes or abnormalities (Cavezzi 2007; Coleridge‐Smith 2006; Labropoulos 2001; Labropoulos 2005; Nicolaides 2000).

Description of the intervention

In 1988, Franceschi described a procedure for the treatment of varicose veins based on venous hemodynamics with preservation of the superficial venous system. He named this procedure ambulatory conservative hemodynamic correction of venous insufficiency (cure conservatrice et hémodynamique de l'insuffisance veineuse en ambulatoire (CHIVA)) (Franceschi 1997).

CHIVA can be performed via open surgery or via endovascular procedures such as laser, radiofrequency or sclerotherapy. It is based on modifying the hemodynamics of the venous system to eliminate varicose dilations and to preserve the saphenous vein. Findings showing that CHIVA decreases the diameter of the saphenous vein (from 2.6 to 1.6 mm) and the femoral vein (from 0.7 to 0.4 mm) have supported this theory (Escribano 2003; Mendoza 2011).

How the intervention might work

The physiological route of venous blood is an anterograde circuit, draining from the superficial venous system to the deep venous system, and finally, to the heart. Primary varicose veins are characterized by a retrograde circuit or a venous‐venous shunt (Goren 1996). This abnormal circuit consists of a retrograde proximal reflux point (escape point) from which blood from the deep venous system is discharged into the superficial venous system, usually the saphenous veins. This pathological situation is caused by the dysfunction of the valves of the veins. The accumulation of blood in the veins causes a hydrostatic pressure column between the escape point and the point of re‐entry into the deep venous system, and it generally comprises the saphenous vein and the perforating re‐entry vein. This blood in the deep venous system can re‐enter the superficial venous system. This closed circuit is the venous‐venous shunt.

The aim of the CHIVA treatment is to eliminate the venous‐venous shunts by disconnecting the escape points, preserving the saphenous vein and normal venous drainage of the superficial tissues of the limb. The CHIVA method is a minimally invasive surgical procedure, usually performed under local anesthesia, based on the findings of a careful analysis of the hemodynamic superficial venous network by duplex ultrasound. The principles underlying the CHIVA method are fragmentation of the venous pressure column, disconnection of venous‐venous shunts, preservation of the re‐entry perforators and abolition of undrained superficial varicose veins. Fragmentation of the venous pressure column and disconnection of venous‐venous shunts is generally implemented by open surgery, but sclerotherapy, laser or radiofrequency can also be used.

Why it is important to do this review

CHIVA is one of the most widely used methods in several countries and is one of the few strategies that treat varicose veins without seeking their destruction.

Objectives

To compare the efficacy and safety of the CHIVA method with alternative therapeutic techniques to treat varicose veins.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

Types of participants

Men and women over 18 years of age with varicose veins at clinical stage C2‐C6 of the CEAP (clinical, etiology, anatomy, pathophysiology) classification (Porter 1995) (Table 4).

Types of interventions

RCTs that assess the CHIVA method compared with other procedures to treat varicose veins, such as drugs, sclerotherapy, compressive dressings and other surgical methods.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Recurrence of varicose veins was defined as the detection of new varicose veins by clinical or ultrasound evaluation after a minimum follow‐up of one year.

Secondary outcomes

1. Re‐treatment or reintervention, defined as the need for a second intervention due to recurrence of varicose veins or new varicose veins in the same leg and the same area.

2. Clinical or esthetic changes after a minimum follow‐up of one month after the intervention, assessed by the following:

Objective signs:

free from reflux, as defined by reverse flow from the deep venous system to the superficial venous system, and checked by duplex ultrasound;

edema, measured by the dichotomous variable edema and the continuous variables 'ankle perimeter circumference' and 'volume of the leg';

skin manifestations, such as venous ulcers and trophic alterations, which may include telangiectasia (small red points on the skin caused by permanently opened tiny blood vessels), reticular veins (dilated veins that show as a net‐like pattern on the skin), varicose veins (permanently dilated veins) or lipodermatosclerosis (a hardening of the skin that may gain a red or brown pigmentation and is accompanied by wasting of the subcutaneous fat).

Subjective symptoms:

pain;

cramps;

restless legs;

itching;

feeling of heaviness in the legs;

swelling;

paresthesias (abnormal sensations, such as prickling, burning, tingling).

Global assessment measures:

disease‐specific quality of life (QoL) scales (e.g. CVIIQ or Veines‐QoL) or satisfaction of participants, or both.

3. Side effects, including hematoma, infection, superficial or deep venous thrombosis, lung embolism and nerve injury.

Search methods for identification of studies

There was no language restriction.

Electronic searches

The Cochrane Peripheral Vascular Diseases Group Trials Search Co‐ordinator (TSC) searched the Specialised Register (last searched April 2015) and the Cochrane Register of Studies (CRS) http://www.metaxis.com/CRSWeb/Index.asp (CENTRAL, 2015, Issue 3). See Appendix 1 for details of the search strategy used to search the CRS. The TSC maintains the Specialised Register, which is constructed from weekly electronic searches of MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, and AMED, and through handsearching relevant journals. The Specialised Register section of the Cochrane Peripheral Vascular Diseases Group module in the Cochrane Library (www.cochranelibrary.com) provides the full list of the databases, journals and conference proceedings that have been searched, as well as the search strategies used.

The TSC searched the following trial databases for details of ongoing and unpublished studies (April 2015) using the terms chiva or c.h.i.v.a:

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry (apps.who.int/trialsearch/);

ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov/);

ISRCTN Registry (http://www.isrctn.com/);

Nederlands Trials Register (www.trialregister.nl/trialreg/admin/rctsearch.asp).

In addition, the review authors searched PubMed (last searched May 2015) using the search strategy given in Appendix 2.

Searching other resources

We scrutinized reference lists of identified RCTs, systematic reviews and meta‐analyses to find further trials.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (SB and MJM) independently assessed the eligibility of the studies identified in the search. We classified eligible studies as included or excluded. In cases of disagreements, a third review author would have independently evaluated the study and discussed it with the rest of the team. However, it was not necessary, as there were no disagreements.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (SB and MJM) collected data independently on a previously tested standardized form. Data included methodological quality, characteristics of study participants, characteristics of the intervention and control groups, and outcome characteristics of each group of participants. One review author (MJM) entered the data into Review Manager 5.1 and performed the appropriate analyses (RevMan 2011).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (SB and MJM) assessed the quality of the studies, examining the randomization method (sequence generation and allocation concealment). They also assessed the blinding of participants and investigators (caregivers and outcome assessors), the completeness of outcome data and the percentage of participants lost to follow‐up.

Once this information was gathered, the authors classified each study into low, unclear or high risk of bias, based on the criteria specified in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

We also specified whether the studies calculated the sample size needed and whether they included an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis.

Measures of treatment effect

For each study, we calculated risk ratios (RR) for dichotomous variables and mean differences (MD) for continuous variables with 95% confidence intervals (CI). If the continuous variables in the studies were measured using different scales, we calculated the standardized mean difference (SMD) and 95% CIs. We also calculated the number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) and the number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome (NNTH) with 95% CIs.

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis was the individual participant.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted study authors to obtain additional information.

The main analysis was an 'available‐case analysis', analyzing data as provided in the individual studies.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We examined the characteristics of each study to determine clinical heterogeneity. We deemed an I2 statistic greater than 50% as substantial heterogeneity. We also studied the sources of heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We did not perform a funnel plot to assess reporting bias because we included fewer than 10 studies (Sterne 2011).

Data synthesis

We estimated the global effect for each variable through a meta‐analysis. We applied the statistical method of Mantel‐Haenszel for dichotomous measures and the inverse variance for continuous measures, using a fixed‐effect model. When I2 was greater than 50%, we used a random‐effects model. If heterogeneity was greater than 75%, we did not pool the results. We performed all statistical analyses using Review Manager 5 (RevMan 2011). We calculated the NNTB and NNTH, and the corresponding 95% CI.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We considered two sources of clinical heterogeneity to plan subgroup analysis if necessary.

Type of procedure used to implement the CHIVA method: open surgery, sclerotherapy, laser, radiofrequency and any other.

Type of comparison assessed: CHIVA versus drugs, compression dressings or other techniques.

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted a sensitivity analysis to assess the strength of the results and to explain possible heterogeneity between the studies. We re‐analyzed the data by ITT, and imputed data using the worst‐case scenario, that is, imputed missing values for participants who withdrew or were lost to follow‐up as negative events in the experimental group and as positive events in the control group.

We did not conduct a sensitivity analyses by comparing any unpublished studies with published studies or by comparing studies with high risk of bias with those having low risk of bias due to lack of suitable data.

Summary of findings table

We created a table compiling and summarizing the evidence of relevant outcomes for the comparison CHIVA versus stripping. We considered study populations consisting of patients with varicose veins. We selected the most important and clinically relevant outcomes (both desirable and undesirable) that were thought to be essential for decision‐making for the Table 1. These outcomes were "recurrence of varicose veins" as main outcome, "bruises", "limb infection", "superficial vein thrombosis" and "nerve damage". Assumed control intervention risks were calculated by mean baseline risk from study population for each outcome and the median control group risk from studies on meta‐analysis when data were obtained from two or more studies. We used the system developed by the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation Working Group (GRADE working group) for grading the quality of evidence as high, moderate, low and very low, based on within‐study risk of bias, directness of evidence, heterogeneity, precision of effects estimates, and risk of population bias (GRADE 2004).

Results

Description of studies

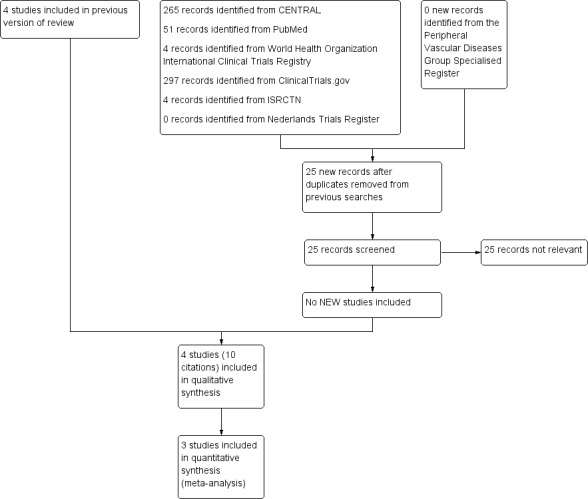

See Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Results of the search

There were no additional studies included in this update. After considering titles and abstracts, we retrieved 15 potentially relevant papers in full text. Finally, after reading the full text, we included 10 papers reporting four RCTs. Three studies compared CHIVA with the stripping technique (Carandina 2008; Iborra‐Ortega 2006; Pares 2010) and one compared CHIVA with the use of compression dressings (Zamboni 2003) (see Characteristics of included studies table). We excluded the remaining five studies (Figure 1) (see Characteristics of excluded studies table).

We contacted three study authors because more information was needed and to clarify doubts regarding missing data (Iborra‐Ortega 2006; Pares 2010; Zamboni 2003).

Included studies

Four included RCTs recruited 796 participants (70.5% women) aged 47 to 63 years (Carandina 2008; Iborra‐Ortega 2006; Pares 2010; Zamboni 2003) (see Characteristics of included studies table).

All participants had CVI and a clinical stage of the CEAP classification between 2 and 6. The study of Iborra‐Ortega 2006 included only people with CEAP 2, whereas the study of Zamboni 2003 included only people with venous ulcers and CEAP 6 (Table 4). Follow‐up of participants also varied between studies, with a minimum of three years (Zamboni 2003) and a maximum of 10 years (Carandina 2008). Three studies compared CHIVA method with stripping (Carandina 2008; Iborra‐Ortega 2006; Pares 2010) and one study compared CHIVA with compression dressings (Zamboni 2003). In all included studies, open surgery was used to implement the CHIVA method.

With the exception of Pares 2010, the studies did not specify sample size calculation.

The funding sources was public in three studies (Iborra‐Ortega 2006; Pares 2010; Zamboni 2003), and not specified in the other (Carandina 2008).

Excluded studies

There were no additional excluded studies in this update. In total, we excluded five studies (see Characteristics of excluded studies table); four controlled studies were not randomized (Maeso 2001; Solis 2009; Zamboni 1995; Zamboni 1998) and one study was not controlled (Zamboni 1996).

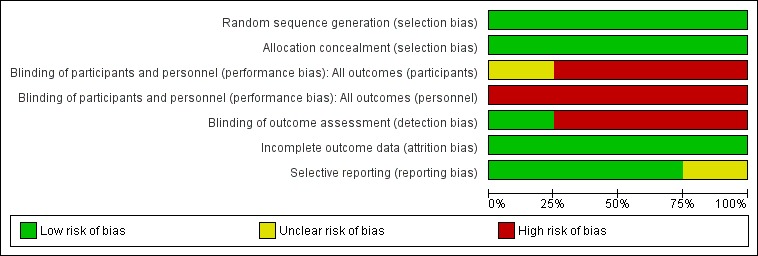

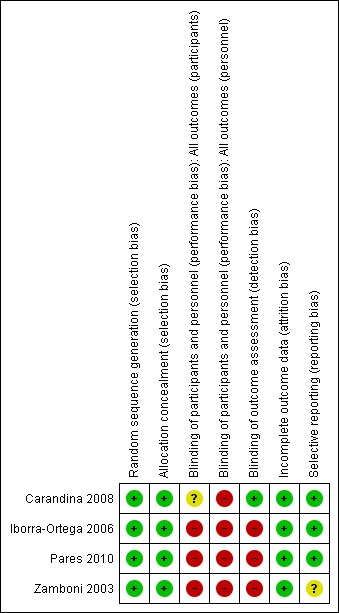

Risk of bias in included studies

Overall, methodological quality of the studies included in this review was low to moderate (Table 1). The risk of bias was generally high, mainly because participants and outcome assessors were not blinded to the interventions (Figure 2; Figure 3).

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

All studies adequately explained how the randomization sequence was generated. Only two of the four studies specified allocation concealment (Carandina 2008; Iborra‐Ortega 2006). We contacted the other two study authors and they provided this information (Pares 2010; Zamboni 2003). Three studies specified that allocation was done by telephone (Iborra‐Ortega 2006; Pares 2010; Zamboni 2003). In the Carandina 2008 study, allocation was blinded to the treating physicians, but it did not state how the blinding was done.

Blinding

Studies could not be blinded because the specific anatomical changes produced by the intervention were easily recognizable by a specialist. In one study, independent assessors evaluated the clinical results in an attempt to compensate for this bias (Carandina 2008).

Incomplete outcome data

The percentage of participants lost to follow‐up was less than 10% in both groups in three of the studies (Iborra‐Ortega 2006; Pares 2010; Zamboni 2003), and in the intervention group in the fourth study (Carandina 2008). However, in the conventional surgery group of the Carandina 2008 study the percentage of losses was 28%.

Selective reporting

In the study of Zamboni 2003, it is not clear if recurrence data were based on ultrasound or clinical parameters. Data about ulcer healing time were incomplete and were not included in this review.

Other potential sources of bias

Other potential sources of bias were not detected.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

We identified only studies comparing CHIVA with vein stripping and with compression dressings.

Comparison of vein stripping versus the CHIVA method

We identified three RCTs that compared vein stripping versus CHIVA (Carandina 2008; Iborra‐Ortega 2006; Pares 2010).

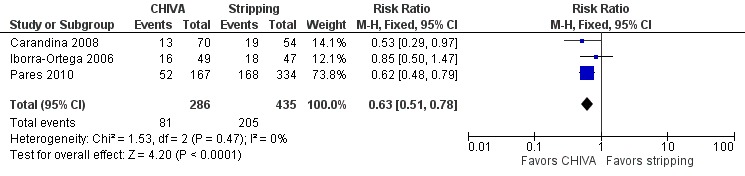

Primary outcome

Recurrence of varicose veins

These three studies included 721 participants. The pooled result was significant and favored the CHIVA method (RR 0.63; 95% CI 0.51 to 0.78; I2 = 0%; NNTB 6; 95% CI 4 to 10) (Figure 4).

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 CHIVA versus stripping, outcome: 1.1 Recurrence of varicose veins.

The sensitivity analysis comparing published studies versus non‐published was not performed because all three studies were published. We did not analyze sensitivity based on the level of risk of bias because all studies had a high risk of bias. None of the studies masked the interventions.

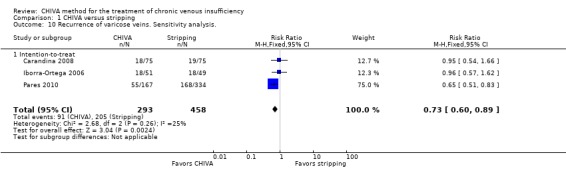

The sensitivity analysis by ITT included 751 people and also favored CHIVA (pooled RR 0.73; 95% CI 0.60 to 0.89; I2 = 25%).

Secondary outcomes

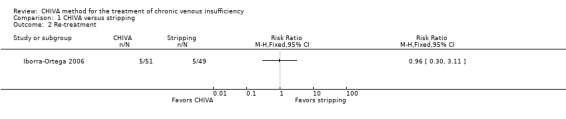

Re‐treatment

Only the Iborra‐Ortega 2006 study reported data about re‐interventions after a five‐year follow‐up. Five participants in each treatment group underwent re‐intervention (RR 0.96; 95% CI 0.30 to 3.11).

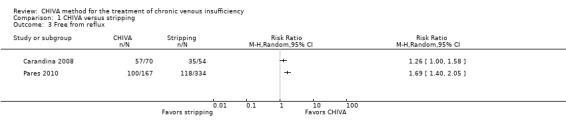

Clinical or esthetic changes

Objective signs:

"Free from reflux", checked by echo‐Doppler (two studies; Carandina 2008; Pares 2010). They had a combined total of 625 participants but their data were not pooled due to the high heterogeneity (I2 = 76%). However, in both studies the results significantly favored the CHIVA method.

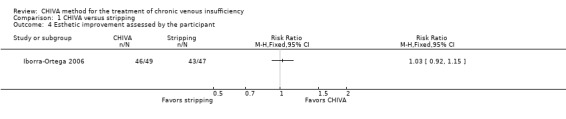

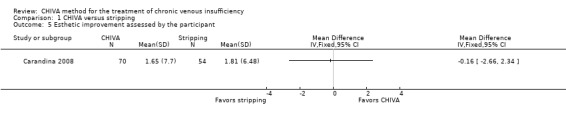

"Edema" was not reported in the included studies.

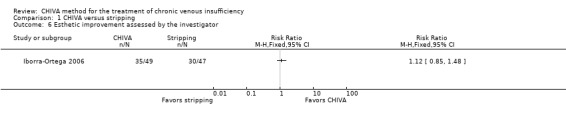

"Aesthetic improvement reported by the patient" was reported in the Iborra‐Ortega 2006 study as a dichotomous outcome. There were no significant differences between the interventions at five‐year follow‐up (RR 1.03; 95% CI 0.90 to 1.18). In the Carandina 2008 study with 124 participants, "aesthetic improvement reported by the patient" was described as a continuous outcome. There were no significant differences between the interventions at 10‐year follow‐up (MD ‐0.16; 95% CI ‐2.66 to 2.34). "Aesthetic improvement reported by the investigator" was reported in the Iborra‐Ortega 2006 study as a dichotomous outcome. There were no significant differences between the interventions at five‐year follow‐up (RR 1.12; 95% CI 0.85 to 1.48).

Subjective symptoms:

None of the three studies specifically measured subjective symptoms. Related outcomes were:

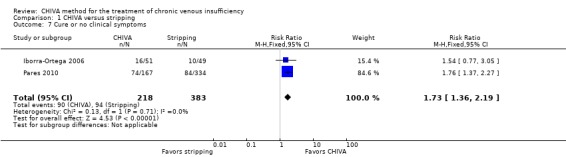

Iborra‐Ortega 2006 and Pares 2010 reported "Cure or no clinical symptoms" in 601 participants. The pooled data significantly favored the CHIVA method (RR 1.73; 95% CI 1.36 to 2.19; I2 = 0%).

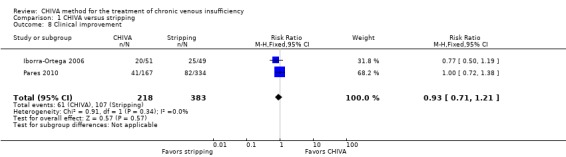

Iborra‐Ortega 2006 and Pares 2010 assessed "Clinical improvement" in 601 participants. The pooled data were not significantly different (RR 0.93; 95% CI 0.71 to 1.21; I2 = 0%).

Global assessment measures:

None of the included trials provided information on QoL or participant satisfaction.

Side effects

Iborra‐Ortega 2006 and Pares 2010 provided information in 601 participants (Figure 5).

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 CHIVA versus stripping, outcome: 1.9 Side effects.

Pares 2010 included information on "Bruises". The CHIVA method reduced the number of participants with bruises compared with stripping (RR 0.63; 95% CI 0.53 to 0.76; NNTH 4; 95% CI 3 to 6). This study also reported information on "Limb infection", finding no significant differences between groups (RR 1.33; 95% CI 0.38 to 4.66).

Iborra‐Ortega 2006 and Pares 2010 included information on "Superficial vein thrombosis". The pooled result was not significant (RR 2.23; 95% CI 0.60 to 8.33; I2 = 42%). The same two studies reported data on "Nerve damage". The pooled result was significant and favored the CHIVA method (RR 0.05; 95% CI 0.01 to 0.38; I2 = 0%; NNTH 12; 95% CI 9 to 20).

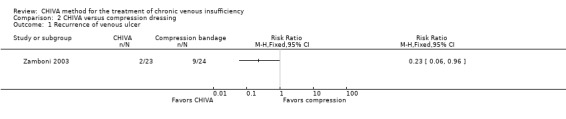

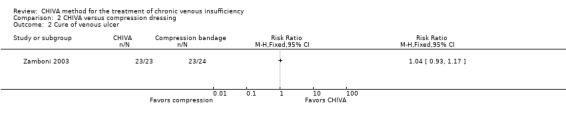

Comparison of compression dressing versus the CHIVA method

One RCT included only participants with venous ulcers. This study compared compression with the CHIVA method in 47 people (Zamboni 2003). The unit of analysis was the ulcer and not the individual, but the data were analyzed because, except for one person, all participants had only one ulcer. The result of the outcome "Recurrence of venous ulcer" significantly favored the CHIVA method (RR 0.23; 95% CI 0.06 to 0.96; NNTH 3; 95% CI 2 to 17). "Cure of venous ulcer" showed no significant differences (RR 1.04; 95% CI 0.93 to 1.17).

The Zamboni 2003 study assessed "Quality of life" measured by the Short Form‐36 (SF‐36) questionnaire, but there were no numerical data presented in the paper. The median score differences (end of observation minus baseline) for the eight domains of SF‐36 questionnaire were shown in a Kaplan‐Meier graph only. The authors concluded that the CHIVA method significantly improved the QoL after a three‐year follow‐up.

Subgroup analysis

All four included studies implemented the CHIVA method by open surgery. Therefore, we did not need to perform a subgroup analysis according to the procedure used to implement the CHIVA method.

Discussion

Summary of main results

This systematic review included four RCTs. All included studies assessed the CHIVA method implemented by open surgery. Three of the four trials compared the CHIVA method with vein stripping for varicose veins, and one compared the CHIVA method with compression for venous ulcers. The results showed that the CHIVA method reduced recurrence of varicose veins compared to other methods. However, no differences in clinical improvement or cosmetic results, as perceived by participants and investigators, were detected between groups. Quality of life was only assessed in the Zamboni 2003 study and the results favored the CHIVA method.

Regarding adverse effects, the CHIVA method showed a lower percentage of bruising and nerve injuries than vein stripping. The risk‐benefit balance therefore favored the CHIVA method over vein stripping.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

We have included all relevant studies that assessed the CHIVA method for treatment of varicose veins in adults. The studies were conducted in Italy and Spain, where the CHIVA method is frequently used (Milone 2011). However, new publications show this method is implemented or considered in other countries such as Taiwan, Switzerland and the USA (Chan 2011; Mendoza 2011; Mowatt‐Larssen 2012).

All participants had venous reflux and the severity of the chronic venous disease was variable, ranging from esthetic alterations to leg ulcers. Three studies compared the CHIVA method implemented by open surgery with vein stripping and only one RCT with 47 participants compared the CHIVA method implemented by open surgery with compression for venous ulcers.

We did not identify any studies that compared the CHIVA method with other surgical approaches such as sclerotherapy, laser or radiofrequency. Evidence, therefore, is limited to the comparison of the CHIVA method implemented by open surgery versus stripping or compression.

All studies included the primary outcome 'recurrence'. The length of follow‐up, from 3 to 10 years, was sufficient to assess recurrence and adverse effects adequately.

Quality of the evidence

Overall, the quality of the evidence in this review was low to moderate due to imprecision caused by the low number of events and because the studies were open. The global risk of bias was high because participants and investigators were not blinded to interventions. Blinded assessment is not possible in clinical trials that assess vein surgery because the intervention has characteristic anatomical consequences.

Potential biases in the review process

The methodological process of our review was rigorous. The search strategy was thorough without language restrictions. We contacted the main authors of included studies for further information. All trials included in the review were funded either by public organizations or non‐profit institutions. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Although one narrative review on the CHIVA method has been published (Mendoza 2008), we found no record of any review with pooled results. Mendoza 2008 included randomized and non‐randomized clinical trials. The conclusions were that the CHIVA method improved subjective and objective outcomes better or equal to stripping, and had lower rate of recurrence and cost.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The CHIVA method appears to result in fewer complications and recurrences than traditional open surgery by stripping. However, there were no data comparing this method to the newer minimally invasive endovenous techniques. CHIVA is an appropriate treatment for varicose veins, although further studies are needed because the results are based on few studies with the quality of the evidence judged to be low to moderate.

Implications for research.

Randomized controlled trials are needed to corroborate the findings reported in this review as they are based on few studies with the methodological quality of the included studies judged to be low to moderate. Quality of life should be included as an outcome of interest in order to measure, with a standardized instrument, the patient satisfaction of the intervention. It could also be of interest to compare the CHIVA method with surgical approaches other than open surgery.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 15 May 2015 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Searches re‐run. No new studies identified. Minor text changes made. No change to conclusions. |

| 15 May 2015 | New search has been performed | Searches re‐run. No new studies identified. Minor text changes made. |

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of the Trials Search Co‐ordinator (Karen Welch) for running searches, Managing Editor (Marlene Stewart), peer reviewers, editors of the Cochrane Peripheral Vascular Diseases Group for their comments on the protocol and review, and Carolyn Newey for their help in editing the manuscript.

Appendices

Appendix 1. CRS search strategy

| #1 | MESH DESCRIPTOR Varicose Veins EXPLODE ALL TREES | 681 |

| #2 | (varicos* near3 (vein* or veno*)):TI,AB,KY | 711 |

| #3 | (tortu* near3 (vein* or veno*)):TI,AB,KY | 6 |

| #4 | (incomp* near3 (vein* or veno* or saphenous or valv*)):TI,AB,KY | 74 |

| #5 | (insuffic* near3 (vein* or veno* or saphenous)):TI,AB,KY | 109 |

| #6 | (((saphenous or vein* or veno*) near3 reflux)):TI,AB,KY | 105 |

| #7 | MESH DESCRIPTOR Saphenous Vein EXPLODE ALL TREES WITH QUALIFIERS SU | 172 |

| #8 | GSV or CVI:TI,AB,KY | 228 |

| #9 | MESH DESCRIPTOR Venous Insufficiency EXPLODE ALL TREES | 333 |

| #10 | #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 | 1455 |

| #11 | ((CHIVA or C.H.I.V.A)):TI,AB,KY | 9 |

| #12 | MESH DESCRIPTOR Ambulatory Surgical Procedures | 1323 |

| #13 | MESH DESCRIPTOR Surgical Procedures, Minimally Invasive | 0 |

| #14 | MESH DESCRIPTOR Vascular Surgical Procedures | 479 |

| #15 | MESH DESCRIPTOR Hemodynamics EXPLODE ALL TREES | 42254 |

| #16 | #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 | 60928 |

| #17 | #10 AND #16 | 265 |

Appendix 2. Authors' PubMed search strategy

| #1 | "Varicose Veins"[MeSH] | 15675 | |

| #2 | varicose vein*[tw] | 13942 | |

| #3 | varice*[tw] | 31203 | |

| #4 | "Venous insufficiency"[MeSH] | 6053 | |

| #5 | venous insufficiency[tw] | 7072 | |

| #6 | #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 | 50984 | |

| #7 | CHIVA[tw] | 54 | |

| #8 | Conservative Haemodynamic Management of Varicose Vein*[tw] | 8 | |

| #9 | Conservative Hemodynamic Management of Varicose Vein*[tw] | 8 | |

| #10 | Conservative Hemodynamic Management[tw] | 3 | |

| #11 | Conservative Haemodynamic Management[tw] | 0 | |

| #12 | hemodynamic correction[tw] | 59 | |

| #13 | haemodynamic correction[tw] | 9 | |

| #14 | #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 | 116 | |

| #13 | #6 AND #14 | 51 | |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. CHIVA versus stripping.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Recurrence of varicose veins | 3 | 721 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.63 [0.51, 0.78] |

| 2 Re‐treatment | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3 Free from reflux | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 4 Esthetic improvement assessed by the participant | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 5 Esthetic improvement assessed by the participant | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 6 Esthetic improvement assessed by the investigator | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 7 Cure or no clinical symptoms | 2 | 601 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.73 [1.36, 2.19] |

| 8 Clinical improvement | 2 | 601 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.71, 1.21] |

| 9 Side effects | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 9.1 Bruises | 1 | 501 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.63 [0.53, 0.76] |

| 9.2 Limb infection | 1 | 501 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.33 [0.38, 4.66] |

| 9.3 Superficial vein trombosis | 2 | 601 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.23 [0.60, 8.33] |

| 9.4 Nerve damage | 2 | 601 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.05 [0.01, 0.38] |

| 10 Recurrence of varicose veins. Sensitivity analysis. | 3 | 751 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.73 [0.60, 0.89] |

| 10.1 Intention‐to‐treat | 3 | 751 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.73 [0.60, 0.89] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CHIVA versus stripping, Outcome 1 Recurrence of varicose veins.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CHIVA versus stripping, Outcome 2 Re‐treatment.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CHIVA versus stripping, Outcome 3 Free from reflux.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CHIVA versus stripping, Outcome 4 Esthetic improvement assessed by the participant.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CHIVA versus stripping, Outcome 5 Esthetic improvement assessed by the participant.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CHIVA versus stripping, Outcome 6 Esthetic improvement assessed by the investigator.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CHIVA versus stripping, Outcome 7 Cure or no clinical symptoms.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CHIVA versus stripping, Outcome 8 Clinical improvement.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CHIVA versus stripping, Outcome 9 Side effects.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CHIVA versus stripping, Outcome 10 Recurrence of varicose veins. Sensitivity analysis..

Comparison 2. CHIVA versus compression dressing.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Recurrence of venous ulcer | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2 Cure of venous ulcer | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 CHIVA versus compression dressing, Outcome 1 Recurrence of venous ulcer.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 CHIVA versus compression dressing, Outcome 2 Cure of venous ulcer.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Carandina 2008.

| Methods | Design: randomized controlled trial Number of participating centers: 1 Setting: hospital Country: Italy Unit of randomization: participant Unit of analysis: participant Follow‐up: participants were reviewed postoperatively at 1, 6, 12 months, and subsequently, after 3 and 10 years |

|

| Participants | Number of participants: 150 (75 surgery and 75 CHIVA) Sex: 33 men and 91 women Age (mean): 48 to 50 years Inclusion criteria: primary chronic venous insufficiency with no history of surgery or sclerotherapy, presence of saphenofemoral reflux and incompetence of the saphenous trunk, presence of a competent deep venous system, at least 1 re‐entry perforator located in the trunk of the saphenous and 1 or more veins and incompetent tributaries of the great saphenous vein Exclusion criteria: aged ≥ 70 years, people with deficiency of the calf muscle pump or unable to walk; people with diabetes, autoimmune diseases, malignancies, severe kidney disease, liver disease, cardio‐respiratory disease, or previous history of deep vein thrombosis |

|

| Interventions | 1) Stripping procedure: saphenofemoral ligation, great saphenous vein stripping from groin to knee, multiple phlebectomies of the tributaries and subfascial ligation of thigh perforating veins 2) CHIVA: saphenofemoral ligation, disconnection from the great saphenous vein of the varicose tributaries and their avulsion through cosmetic incisions Postoperative management: people treated with CHIVA wore class 2 medical compression stockings above the knee for 3 weeks. Limbs that had been treated by saphenous stripping were bandaged to minimize bruising. Bandages were replaced with class 2 medical compression stockings above the knee after 1‐3 days and then worn for 14 days. Study participants were usually discharged from hospital on the day of surgery |

|

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: recurrence of varicose veins at 10 years of follow‐up. Recurrence was defined as class C or D of the Hobbs' score (Hobbs 1974) (Table 5) and the presence of reflux on duplex ultrasonography with a demonstrable escape point Secondary outcome: functional or cosmetic results Both clinical and ultrasound examinations were performed at each visit Clinical assessment of surgical results: 3 independent assessors, who had not been involved in previous surgical decision making and operative procedures, examined all limbs. They assigned a score to each limb according to the method reported by Hobbs. Subsequently, participants were further analyzed by duplex scanning using a standard methodology. Functional and cosmetic results were self assessed by the participants at the time of the last examination in hospital Assessment of recurrences: were considered varicose veins recurrence if: 1) the remaining or newly formed varicose veins had a diameter > 5 mm and the presence of incompetent main trunks and perforator (Hobbs' score C and D) 2) there was presence of reflux, as measured by duplex ultrasonography, with a demonstrable escape point and change of venous network |

|

| Notes | Sample size was specified in the 'methods' section | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Study randomisation was by a computer‐generated randomisation list of the 150 patients, structured in balanced blocks of 4 patients and blinded to the treating physicians. The allocated treatment was disclosed shortly before surgical treatment and patients were treated with saphenous stripping or CHIVA, 75 patients by each technique" Comment: study randomization was by a computer‐generated randomization list, structured in balanced blocks |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Study randomisation was by a computer‐generated randomisation list of the 150 patients, structured in balanced blocks of 4 patients and blinded to the treating physicians. The allocated treatment was disclosed shortly before surgical treatment and patients were treated with saphenous stripping or CHIVA, 75 patients by each technique" Comment: allocation was blinded to the treating physicians. The allocated treatment was disclosed shortly before surgical treatment |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes (participants) | Unclear risk | It is not specified if the participants were blinded |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes (personnel) | High risk | The surgeon that applied the intervention was unblinded |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "At the time of scoring the surgical outcome the assessors were unaware of the procedure each patient" Comment: the assessor was blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | There were 26 (17.3%) participants lost in 10 years of follow‐up, with no differences between groups. The reasons for losses were not specified |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | The results of all outcomes prespecified in the methods of the trial report were presented. The trial protocol was not requested from the study authors |

2. Hobbs' classification and scores.

| Class | Clinical indication |

| Class A (score 1) | No visible and palpable varicose veins |

| Class B (score 2) | A few visible and palpable varicose veins with diameter < 5 mm |

| Class C (score 3) | Remaining or newly formed varicose veins with diameter > 5 mm |

| Class D (score 4) | Incompetent main trunks and perforator |

See Hobbs 1974.

Iborra‐Ortega 2006.

| Methods | Design: randomized controlled trial Number of participating centers: 1 Setting: hospital Country: Spain Unit of randomization: participant Unit of analysis: participant. Follow‐up: first week after surgery; 1, 3, and 6 months; and thereafter annually to 5 years |

|

| Participants | Number of participants: 100 (49 stripping and 51 CHIVA) Sex: 38 men and 62 women Age (mean): 49 years (range 26 to 69) Inclusion criteria: according to the guidelines of the Society of Angiology and Vascular Surgery (SEAVC) including the presence of symptomatic varicose veins with saphenous involvement or perforating veins (or both), or asymptomatic large varicose veins with a potential risk of complications (varicophlebitis or bleeding) Exclusion criteria: people with alterations in the deep venous system, with a history of venous thrombosis, with previous treatment (surgery or sclerotherapy), morbidly obese people, aged ≥ 70 years |

|

| Interventions | 1) CHIVA: according to the cartographic map, different strategies were applied: CHIVA 1 (superficial venous drainage system with a single surgical procedure), CHIVA 2 (required 2 possible surgical steps to ensure the drainage of the system) and CHIVA 1+2 (with a single surgical procedure, the superficial system is not drained and therefore represents a conservative but not hemodynamic treatment) 2) Vein stripping |

|

| Outcomes | Primary endpoint: rate of complications and, clinical and hemodynamic outcomes Secondary outcomes: type of anesthesia, surgical time, level of activity after 1 week of the intervention, time off work and cosmetic results at 1 and 6 months and annually, number of reoperations performed during the follow‐up Assessment: the week after surgery when the stitches were removed; at the first, third and sixth postoperative months; and annually thereafter to complete 5 years of follow‐up Assessment of recurrences: "Finally, a patient was considered cured when he was clinically asymptomatic or was better, he was pleased with the aesthetic results and the objective assessment of varicosities was not visible or they were of a diameter less than 5 mm." "Thus, patients not included in this characterization would be considered as disease recurrence" |

|

| Notes | Grants from Fundació August Pi i Sunyer (Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge) and SEACV (Sociedad Española de Angiología y Cirugía Vascular) Sample size not stated |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "The patients were randomized with the software Excel of Window" Comment: we assume that the generation of random sequence was performed by computer |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "the patients were allocated by phone" Comment: there was allocation concealment because the investigator did not know the random sequence |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes (participants) | High risk | The participants knew the intervention to which they were assigned |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes (personnel) | High risk | The personnel knew the intervention assigned to the participant |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | There was no blinding of outcome assessors |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | The losses were minimal at 4% at 5‐year follow‐up (2 participants in each group) |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | The results of all outcomes prespecified in the methods of the trial report were presented. The trial protocol was not requested from the authors |

Pares 2010.

| Methods | Design: randomized controlled trial Number of participating centers: 1 Setting: hospital Country: Spain Unit of randomization: participant Unit of analysis: participant Follow‐up: immediately postoperatively and 3, 6, 12, 24, 36, 48, and 60 months after surgery |

|

| Participants | Number of participants: 501 (156 striping with clinical marking, 159 stripping with duplex marking, 160 CHIVA) Sex: 147 men and 354 women Age: 48 to 50 years (standard deviation 12) Inclusion criteria: people diagnosed with varicose veins by a vascular surgeon in the outpatient clinic and according to the criteria of the CEAP classification of venous insufficiency Exclusion criteria: people with congenital venous disease, varicose veins secondary to previous thrombosis, post‐thrombotic side effects, sclerotherapy, recurrent varicose veins, associated systemic diseases or people who did not agree to participate in the study, who refused surgery, who could not participate in long‐term monitoring or women who had been pregnant for less than 6 months |

|

| Interventions | 1) Group CHIVA: disconnection of the point reflux and preservation of the superficial venous system drainage Points of venous reflux were closed by ligation and division reflux of the saphenofemoral junction (preserving draining veins and tributaries), ligation and division of the saphenopopliteal union (preserving the Giacomini vein drainage) or subfascial closure of perforating veins, preservation of the incompetent segments of great saphenous vein or short saphenous vein (or both), removal of secondary reflux points originating the varicose vein, the preservation of re‐entry points (perforating vein), and phlebectomy of collateral veins with improper drainage Physical and Doppler ultrasound examination to identify incompetent segments. A map was produced and printed with venous images, points of reflux, the diameter of the saphenous vein and superficial and re‐entry points. These documents were the baseline for comparison in follow‐up 2) Stripping with clinic marking: remove the incompetent superficial venous system Before surgery, the surgeon decided which segments were incompetent and to be removed. The decision was based on physical examination, identification of incompetent segments and points of re‐entry. The surgical procedure consisted of the closing of the points of reflux, by ligation and division of the saphenofemoral junction, tributaries veins in the groin or ligation and division of the saphenopopliteal union or subfascial closure of perforating veins, and removal of all the great saphenous vein or superficial venous system (or both) or phlebectomy. 3) Stripping with duplex marking: remove the incompetent superficial venous system Surgical strategy was based on the closing of the points of reflux by ligation and division of the saphenofemoral junction in the groin, or ligation of tributary veins and division of the union or saphenopopliteal subfascial closure, of perforating veins, removal of only the incompetent segment of great saphenous vein or the superficial venous system (or both), phlebectomy of varicose veins and closing points of re‐entry The physical examination and Doppler ultrasound were used to identify incompetent segments. Authors carried out a map of varicose veins and ultrasound images were stored. Points of reflux were marked, also the diameter of the great saphenous vein and minor saphenous vein and re‐entry points. These documents were the baseline for comparison in follow‐up Postoperative management: pressure bandage from the groin to the foot for 48 hours, then elastic stockings for 4 weeks. Analgesic and antithrombotic prophylaxis treatment were common to all participants |

|

| Outcomes | Primary endpoint: recurrence rate of varicosity (using Hobbs' classification) (Hobbs 1974) (Table 5) Secondary outcomes: ultrasonographic recurrence of varicose veins, descriptive baseline characteristics, type of anesthesia, days of convalescence, clinical cure, clinical improvement and complications (deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary thromboembolism, death, bruises, subcutaneous inguinal hemorrhage, neuralgia of the saphenous nerve, wound infection and phlebitis) Postsurgical complications were evaluated at 8 days' postintervention Clinical follow‐up and duplex ultrasonography with venous mapping were at 3, 6, 12, 24, 36 48, and 60 months after surgery |

|

| Notes | Authors were contacted to obtain information on the randomization process Funding: Institute of Health Carlos III, Ministry of Health (Spanish Ministry of Health) and Consumption, by 2 research grant FIS 94/5365 and FIS 97/0694 (Spain), and a research grant from the Non‐Invasive Vascular Diagnosis Area of the Spanish Society for Angiology and Vascular Surgery and Endovascular (Spanish Society of Angiology and Vascular Surgery), 2003 The sample size was specified in the methods section |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | The publication does not specify the method of generating the randomization sequence. We contacted the authors who explained that the method of sequence generation was centralized and independent of the clinicians: randomization generated by computer in blocks of 6 |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | The publication does not specify the method of allocation concealment. We contacted the authors who explained that the allocation was centralized by telephone and independent of the clinicians |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes (participants) | High risk | Quote: "This was a randomized, open‐label controlled trial" Comment: it was an open study |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes (personnel) | High risk | Quote: "This was a randomized, open‐label controlled trial" Comment: it was an open study |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Quote: "This was a randomized, open‐label controlled trial" Comment: it was an open study |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | The losses were minimal: 15 (3%) participants |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | The results of all outcomes prespecified in the methods of the trial report were presented. The trial protocol was not requested from the authors |

Zamboni 2003.

| Methods | Design: randomized controlled trial Number of participant centers: 1 Setting: hospital Country: Italy Unit of randomization: participant Unit of analysis: ulcer and participant Follow‐up: twice a year for 3 years |

|

| Participants | Number of participants: 45 Ulcers: 47 ulcers (21 people with 23 ulcers treated with CHIVA; 24 people with 24 ulcers treated with compression) Sex: 18 men and 27 women Age (mean): 63 years Inclusion criteria: people with venous ulcer Exclusion criteria: aged ≥ 80 years, inability to walk, ulcers < 2 cm2 or > 12 cm2, diabetes, peripheral arterial disease or an ankle brachial index < 0.9, secondary or congenital venous disease (history of deep venous thrombosis or ultrasound evidence of deep venous obstruction or reflux (or both), congenital angiodysplasia) |

|

| Interventions | 1) CHIVA group: operations were performed under local anesthesia and Doppler ultrasound. Depending on the location of the re‐entry of the perforator were 2 different minimally invasive techniques:

a) The opening was located on the main venous trunk (type I cases)

b) The opening was located in the venous branches (type III cases) Cases of type I: the operation included high ligation of the venous saphenofemoral or popliteal union completed by ligation and division of the venous saphenous trunk and insufficient branches. The result was the creation of a drainage flow down into the venous saphenous trunk re‐entering the deep circulation through perforators Cases of type III: the operation involved ligation and disconnection of the venous saphenous trunk insufficient branches. The process could contain a second step consisting of high ligation Participants began to walk 1 hour after the operation with the ulcer protected with a bandage and with half elastic compression at the ankle. Participants were discharged after 3 hours and were visited twice per week the first week and then every week until the ulcer healed 2) Compression group: treated with foam dressing, zinc oxide and an inelastic bandage applied from the foot to the knee. Antibiotics were used selectively according to sensitivities. The dressing was changed every 3‐5 days the first month and then every 7 days until the ulcer was healed. Once ulcers healed, elastic stockings were prescribed. In the case of recurrence, the dressing protocol was repeated Monitoring: participants in both groups were reviewed clinically, completed the questionnaire on quality of life (SF‐36), and underwent a Doppler ultrasound and plethysmography twice a year for 3 years |

|

| Outcomes | Primary outcomes: healing rate, recurrence rate Secondary outcomes: ulcerated area, quality of life (SF‐36 questionnaire) | |

| Notes | Study authors were contacted to obtain information on the randomization process

Sample size was calculated Grant funding: "Venous Ulcers: TISSUE AND GROWTH FACTORS HAEMODYNAMICS of the Italian Ministry of the University and Scientific and Technological Research (MURST)" |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | We contacted the first study author by e‐mail. His response was: " The study was preceded by a computer‐generated randomisation list, structured in balanced blocks of 4 patients and prepared by the local dept. of mathematics, of course blinded to the treating physicians. Once the patient was included in the study the physician called the secretary of the department, who communicated him/her the arm. I hope this clear" Comment: the generation of random sequence was blinded |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | We contacted the first study author by e‐mail. His response was: " The study was preceded by a computer‐generated randomisation list, structured in balanced blocks of 4 patients and prepared by the local dept. of mathematics, of course blinded to the treating physicians. Once the patient was included in the study the physician called the secretary of the department, who communicated him/her the arm" Comment: there was allocation concealment |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes (participants) | High risk | It was an open study |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes (personnel) | High risk | It was an open study |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | It was an open study |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No losses to follow‐up (3 years) |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | The paper did not report the results of quality of life. It is not clear if data of recurrence were based in ultrasounds or clinical parameters. There were insufficient data about the time to heal the ulcer to include in the analysis of the review |

CHIVA: conservative hemodynamic correction of venous insufficiency; SF‐36: Short Form‐36.

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Maeso 2001 | Controlled trial, not randomized, case‐review study |

| Solis 2009 | Prospective, controlled trial, not randomized |

| Zamboni 1995 | Prospective, controlled trial, not randomized |

| Zamboni 1996 | Prospective, non‐controlled clinical trial |

| Zamboni 1998 | Prospective, controlled trial, not randomized |

Differences between protocol and review

The title has been changed from "CHIVA method for the treatment of varicose veins" to "CHIVA method for the treatment of chronic venous insufficiency".

The name of the primary outcome "Recurrence of varicosity" has been changed to "Recurrence of varicose veins". Varicosity and varicose veins have the same meaning, but varicose veins is the most commonly used term.

Contributions of authors

Conceiving the review: SB, JME Designing the review: SB, MJM Co‐ordinating the review: MJM Designing electronic search strategy: Cochrane Peripheral Vascular Diseases Group editorial base Screening search results: SB, MJM Obtaining copies of trials: SB, MJM Appraising quality of papers: SB, MJM Abstracting data from papers: SB, MJM Data management for the review: MJM Entering data into RevMan: MJM Analysis of data: MJM Interpretation of data: all authors Writing the review: MJM, SB, JME Draft the final review: all authors Guarantor for the review: SB, MJM

Sources of support

Internal sources

Iberoamerican Cochrane Center, Spain.

External sources

-

Chief Scientist Office, Scottish Government Health Directorates, Scottish Government, UK.

The PVD Group editorial base is supported by the Chief Scientist Office.

-

Associazione "Umanizazione" della Chirurgia, Italy.

This is a not‐for‐profit organization that promotes formative and scientific sessions (scientific meetings, workshops, etc.) principally in relation to venous hemodynamics of the lower limbs. This organization partially finances this review because it has an interest in the independent assessment of the CHIVA method but it does not have influence on the review process.

Declarations of interest

SB: reports he received payment from Sanofi‐Aventis for presenting to an Internal expert class and from Otsuka/Ferrer for consultancy at EMA. These activities were not related to this review JME: none known JD: none known MJM: reports that Associazione "Umanizazione" della Chirurgia, Italy paid money to her institution to finance this review

New search for studies and content updated (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Carandina 2008 {published data only}

- Carandina S, Mari C, Palma M, Marcellino MG, Cisno C, Legnaro A, et al. Varicose vein stripping vs haemodynamic correction (CHIVA): a long term randomised trial. European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery 2008;35(2):230‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carandina S, Mari C, Palma M, Marcellino MG, Legnaro A, Liboni A, et al. Stripping vs haemodynamic correction (CHIVA): a long term randomised trial. Phlebology 2006;21(3):151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Iborra‐Ortega 2006 {published data only}

- Iborra E. Comparative clinical study: CHIVA vs phlebectomy [Ensayo clínico comparativo: Fleboextracción versus CHIVA]. Anales de Cirugía Cardíaca y Vascular 2006;12(2):109. [Google Scholar]

- Iborra E, Linares P, Hernández E, Vila R, Cairols MA. Clinical and random study comparing two surgical techniques for varicose veins treatment: immediate results [Estudio cínico y aleatorio que compara dos técnicas quirúrgicas para el tratamiento de las varices: resultados inmedatos]. Angiología 2000;6:253‐8. [Google Scholar]

- Iborra E, Vila R, Barjau E, Cairols MA. Surgical treatment of varicose veins: comparative study between two different techniques. Phlebology 2006;21(3):152. [Google Scholar]

- Iborra‐Ortega E, Barjau‐Urrea E, Vila‐Coll R, Ballon‐Carazas H, Cairols‐Castellote MA. Comparative study of two surgical techniques in the treatment of varicose veins of the lower extremities: results after five years of follow up [Estudio comparativo de dos técnicas quirúrgicas en el tratamiento de las varices de las extremidades inferiores: resultados tras cinco años de seguimiento]. Angiología 2006;58(6):459‐68. [Google Scholar]

Pares 2010 {published data only}

- Pares JO, Juan J, Tellez R, Mata A, Moreno C, Quer FX, et al. Varicose vein surgery: stripping versus the CHIVA method: a randomized controlled trial. Annals of Surgery 2010;251(4):624‐31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pares JO, Juan J, Tellez R, Mata A, Moreno C, Quer FX, et al. Varicose vein surgery: stripping versus the CHIVA method: a randomized controlled trial. Vasomed 2011;23(2):98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pares O, Juan J, Moreno C, Tellez R, Codony I, Mata A, et al. Randomized clinical trial on surgical techniques for the treatment of varicose veins in legs: non‐conservative treatment compared with a conservative one. Five years follow‐up. Phlebology 2008;23(5):243. [Google Scholar]

Zamboni 2003 {published data only}

- Zamboni P, Cisno C, Marchetti F, Mazza P, Fogato L, Carandina S, et al. Minimally invasive surgical management of primary venous ulcers vs. compression treatment: a randomized clinical trial. European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery 2003;25(4):313‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Maeso 2001 {published data only}

- Maeso J, Juan J, Escribano J, Allegue NM, Matteo A, Gonzalez E, et al. Comparison of clinical outcome of stripping and CHIVA for treatment of varicose veins in the lower extremities. Annals of Vascular Surgery 2001;15(6):661‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Solis 2009 {published data only}

- Solís JV, Ribé L, Portero JL, Rio J. Stripping saphenectomy, CHIVA and laser ablation for the treatment of the saphenous vein insufficiency. Ambulatory Surgery 2009;15(1):11‐4. [Google Scholar]

Zamboni 1995 {published data only}

- Zamboni P, Marcellino MG, Feo CV, Pisano L, Vasquez G, Bertasi M, et al. Alternative saphenous vein sparing surgery for future grafting. Panminerva Medica 1995;37(4):190‐7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Zamboni 1996 {published data only}

- Zamboni P, Feo CV, Marcellino MG, Vasquez G, Mari C. Haemodynamic correction of varicose veins (CHIVA): an effective treatment?. Phlebology 1996;11(3):98‐101. [Google Scholar]

Zamboni 1998 {published data only}

- Zamboni P, Marcellino MG, Cappelli M, Feo CV, Bresadola V, Vasquez G, et al. Saphenous vein sparing surgery: principles, techniques and results. Journal of Cardiovascular Surgery 1998;39(2):151‐62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Agus 2001

- Agus GB, Allegra C, Arpaia G, Botta G, Cataldi A, Gasbarro V, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic venous insufficiency. International Angiology 2001;20(1):2‐37. [Google Scholar]

Allan 2000

- Allan PL, Bradbury AW, Evans CJ, Lee AJ, Vaughan Ruckley C, Fowkes FG. Patterns of reflux and severity of varicose veins in the general population ‐ Edinburgh Vein Study. European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery 2000;20(5):470‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Aziz 2011

- Aziz Z, Cullum NA, Flemming K. Electromagnetic therapy for treating venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2011, Issue 3. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002933.pub4] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Blomgren 2004

- Blomgren L, Johansson G, Dahlberg‐Akerman A, Norén A, Brundin C, Nordström E, et al. Recurrent varicose veins: incidence, risk factors and groin anatomy. European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery 2004;27(3):269‐74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Carpentier 2004

- Carpentier PH, Maricq HR, Biro C, Ponçot‐Makinen CO, Franco A. Prevalence, risk factors, and clinical patterns of chronic venous disorders of lower limbs: a population‐based study in France. Journal of Vascular Surgery 2004;40(4):650‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cavezzi 2007

- Cavezzi A, Labropoulos N, Partsch H, Ricci S, Caggiati A, Myers K, et al. Duplex ultrasound investigation of the veins in chronic venous disease of the lower limbs. UIP consensus document. Part II. Anatomy. Vasa 2007;36(1):62‐71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chan 2011

- Chan CY, Chen TC, Hsieh YK, Huang JH. Retrospective comparison of clinical outcomes between endovenous laser and saphenous vein‐sparing surgery for treatment of varicose veins. World Journal of Surgery 2011;35(7):1679‐86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Coleridge‐Smith 2006

- Coleridge‐Smith P, Labropoulos N, Partsch H, Myers K, Nicolaides A, Cavezzi A. Duplex ultrasound investigation of the veins in chronic venous disease of the lower limbs. UIP consensus document. Part I. Basic principles. European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery 2006 ;31(1):83‐92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cullum 2010

- Cullum NA, Al‐Kurdi D, Bell‐Syer SEM. Therapeutic ultrasound for venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010, Issue 6. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001180.pub3] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Escribano 2003

- Escribano JM, Juan J, Bofill R, Maeso J, Rodríguez‐Mori A, Matas M. Durability of reflux‐elimination by a minimal invasive CHIVA procedure on patients with varicose veins. A 3‐year prospective case study. European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery 2003;25(2):159‐63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Flemming 1999

- Flemming K, Cullum NA. Laser therapy for venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 1999, Issue 1. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001182] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Franceschi 1988

- Franceschi C. Theorie et pratique de la cure: conservatrice et hemodynamique de l'insuffisance veineuse en ambulatoire. Precy‐sous‐Thil, France: Editions de l’Armançon, 1988. [Google Scholar]

Franceschi 1997

- Franceschi C. Measures and interpretation of venous flow in stress tests. Manual compression and Parana manoeuver. Dynamic reflux index and Psatakis index [Mesures et interprétation des flux veineux lors des manoevres de stimulation. Compressions manuelles et manoeuvre de Paranà. Indice dynamique de reflux (IDR) et indice de Psatakis]. Journal des Maladies Vasculaires 1997;22(2):96‐136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Goren 1996

- Goren G, Yellin AE. Hemodynamic principles of varicose vein therapy. Dermatologic Surgery 1996;22(7):657‐62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

GRADE 2004

- GRADE Working Group. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2004;328:1490‐4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hamdan 2012

- Hamdan A. Management of varicose veins and venous insufficiency. JAMA 2012;308(24):2612‐21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2011

- Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org.

Hobbs 1974

- Hobbs JT. Surgery and sclerotherapy in the treatment of varicose veins. A random trial. Archives of Surgery 1974;109:793‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Juan 2002

- Juan J, Escribano JM, Maeso J. Hemodynamic after stripping of varicose vein [Hämodynamik des Varizenrezidivs nach Strippingoperation]. 18 Jahreskongress 2002 der Deutschen Gessellschaft für GefäBchirurgie ‐ Gesellschaft für vaskuläre und endovaskuläre Chirurgie. Würzburg (Germany). 2002.

Jull 2008

- Jull AB, Rodgers A, Walker N. Honey as a topical treatment for wounds. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2008, Issue 4. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD005083.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Keller 1905

- Keller WL. A new method of extirpating the internal saphenous and similar veins in varicose conditions. A preliminary report. New York Medical Journal 1905;82:385‐6. [Google Scholar]

Kranke 2004

- Kranke P, Bennett MH, Debus SE, Roeckl‐Wiedmann I, Schnabel A. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for chronic wounds. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2004, Issue 1. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004123.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kurz 1999

- Kurz X, Kahn SR, Abenhaim L, Clement D, Norgren L, Baccaglini U, et al. Chronic venous disorders of the leg: epidemiology, outcomes, diagnosis and management. Summary of an evidence‐based report of the VEINES task force. Venous Insufficiency Epidemiologic and Economic Studies. International Angiology 1999;18(2):83‐102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Labropoulos 2001