Autophagy maintains cell, tissue and organism homeostasis through degradation. Codogno, Boya and Reggiori review recent data that have uncovered unexpected functions of autophagy, such as regulation of metabolism, membrane transport and modulation of host defenses.

Subject terms: Membrane trafficking, Macroautophagy, Autophagy

Abstract

Autophagy maintains cell, tissue and organism homeostasis through degradation. Complex post-translational modulation of the Atg (autophagy-related) proteins adds additional entry points for crosstalk with other cellular processes and helps define cell-type-specific regulations of autophagy. Beyond the simplistic view of a process exclusively dedicated to the turnover of cellular components, recent data have uncovered unexpected functions for autophagy and the autophagy-related genes, such as regulation of metabolism, membrane transport and modulation of host defenses — indicating the novel frontiers lying ahead.

Main

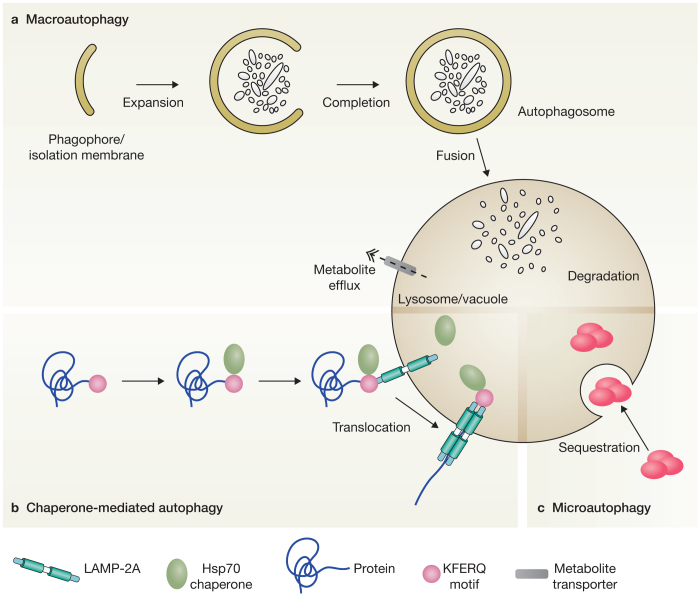

The word autophagy, derived from the Greek word for “self-eating”, refers to the catabolic processes through which the cell turns over its own constituents1. The proteasome is also involved in cellular degradation, but autophagy refers only to those pathways that lead to the elimination of cytoplasmic components by delivering them into mammalian lysosomes or plant and yeast vacuoles. Autophagy is often labelled as degradative, but it is more accurate to describe it as a recycling pathway to highlight its important contribution to cell physiology. Metabolites generated in the lysosomes or vacuoles as a result of autophagy are reused either as sources of energy or building blocks for the synthesis of new macromolecules. So far, three major types of autophagy have been described: macroautophagy, microautophagy and chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA) (Fig. 1). This Review will focus on macroautophagy, hereafter referred to as autophagy.

Figure 1. The different types of autophagy.

(a) Macroautophagy is characterized by the sequestration of structures targeted for destruction into double-membrane vesicles called autophagosomes. Complete autophagosomes first fuse with endosomes before finally exposing their content to the hydrolytic interior of lysosomes. The resulting metabolites are transported into the cytoplasm and used either for the synthesis of new macromolecules or as a source of energy. (b) During chaperone-mediated autophagy, proteins carrying the pentapeptide KFERQ-like sequence are recognized by the Hsc70 chaperone, which then associates with the integral lysosome membrane protein LAMP-2A, triggering its oligomerization. This event leads the translocation of the bound protein into the lysosome interior through a process that requires Hsc70. (c) Microautophagy entails the recruitment of targeted components in proximity with the lysosomal membrane, which subsequently invaginates and pinches off.

Autophagy is characterized by the formation of double-membrane vesicles called autophagosomes, which sequester the cytoplasmic structures targeted for destruction (Fig. 1). Following autophagy induction, the Atg proteins (Table 1) assemble at a specialized site that has been named the phagophore assembly site or the pre-autophagosomal structure (PAS)2. From here, they participate (probably together with specific SNAREs and tethering factors) in the orchestrated fusion of Golgi-, endosome- and plasma-membrane-derived membranes to form the phagophore3. The PAS has been shown to emerge from regions of the mammalian endoplasmic reticulum enriched in the phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate (PtdIns3P)-binding protein DFCP1, which have been named omegasomes4. The visualization of contact points between omegasomes and phagophores have led to the hypothesis that lipids are supplied to the nascent autophagosomes by direct transfer from the endoplasmic reticulum5,6, but other lipid sources, such as mitochondria, have also been implicated in this process7. Complete autophagosomes subsequently fuse with the lysosomes (or vacuoles in plants and yeast) to expose their content to the hydrolases in the interior of these organelles.

Table 1.

The key proteins mediating the biogenesis of an autophagosome

| Protein | Yeast | High eukaryotes | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atg1/ULKs | + | + | Protein kinase involved in the induction of autophagy and possibly in PAS/phagophore biogenesis |

| Atg2 | + | + | Interacts with Atg18/WIPI4; possibly involved in PAS/phagophore biogenesis |

| Atg3 | + | + | E2-like enzyme for the ubiquitin-like conjugation system that catalyses Atg8/LC3's lipidation involved in phagophore expansion |

| Atg4 | + | + | Cysteine protease processing and delipidating Atg8/LC3, thus involved in phagophore expansion |

| Atg5 | + | + | Covalently linked to Atg12, generating the Atg12–Atg5 conjugate involved in phagophore expansion |

| Atg6/beclin 1 | + | + | Component of various PI(3)K complexes, one of which is involved in induction of autophagy and PAS/phagophore biogenesis |

| Atg7 | + | + | E1-like enzyme for the two ubiquitin-like conjugation systems, thus involved in phagophore expansion |

| Atg8/LC3s | + | + | Ubiquitin-like protein involved in phagophore expansion |

| Atg9 | + | + | Transmembrane protein involved in the induction of autophagy and possibly in PAS/phagophore biogenesis |

| Atg10 | + | + | E2-like enzyme for the ubiquitin-like conjugation system that mediates the formation of the Atg12–Atg5 conjugate involved in phagophore expansion |

| Atg12 | + | + | Ubiquitin-like protein involved in phagophore expansion |

| Atg13 | + | + | Binding partner and regulator of Atg1/ULKs, thus involved in the induction of autophagy and possibly PAS/phagophore biogenesis |

| Atg14 | + | + | Component of the PI(3)K complex I involved in induction of autophagy and possibly PAS/phagophore biogenesis |

| Atg16 | + | + | Associates with Atg12–Atg5 to form a large complex, which acts as an E3 ligase to direct LC3 lipidation on autophagosomal membranes, and thus involved in phagophore expansion |

| Atg17/FIP200 | + | + | Binding partner and regulator of Atg1/ULKs, thus involved in the induction of autophagy and possibly PAS/phagophore biogenesis |

| Atg18/WIPIs | + | + | PtsIns3P-binding proteins possibly involved in PAS/phagophore biogenesis |

| Atg23 | + | − | Binding partner and regulator of Atg9, thus involved in the induction of autophagy and possibly in PAS/phagophore biogenesis |

| Atg27 | + | − | Binding partner and regulator of Atg9, thus involved in the induction of autophagy and possibly in PAS/phagophore biogenesis |

| Atg29 | + | − | Binding partner and regulator of Atg1, thus involved in the induction of autophagy and possibly in PAS/phagophore biogenesis |

| Atg31 | + | − | Binding partner and regulator of Atg1, thus involved in the induction of autophagy and possibly in PAS/phagophore biogenesis |

| Atg101 | − | + | Binding partner and regulator of ULKs, thus involved in the induction of autophagy and possibly in PAS/phagophore biogenesis |

| Ambra1 | − | + | Regulator of the PI(3)K and Atg1/ULK complexes, and thus involved in the induction of autophagy |

| DFCP1 | − | + | PtdIns3P-binding proteins concentrating at the omegasome, possibly involved in the induction of autophagy |

| VMP1 | − | + | Transmembrane protein regulating autophagy induction |

| Vps15/p150 | + | + | Kinase regulating Vps34/hVps34 activity; component of various PI(3)K complexes, one of which is involved in the induction of autophagy and PAS/phagophore biogenesis |

| Vps34/PtdIns3PKC3 | + | + | Component of various PI(3)K complexes, one of which is involved in the induction of autophagy and PAS/phagophore biogenesis |

Autophagy has been shown to participate in physiological processes ranging from adaptation to starvation, cell differentiation and development, the degradation of aberrant structures, turnover of superfluous or damaged organelles, tumour suppression, innate and adaptive immunity, lifespan extension and cell death8,9,10. The identification of the Atg proteins in autophagy was a milestone in the understanding of the importance of this process1,9. Furthermore, the post-translational modifications of the Atg proteins documented so far confer great plasticity for the integrated transduction of multiple stimuli into the Atg machinery. More recently, additional functions have been assigned to autophagic structures beyond their fusion with the lysosomal compartment, as well as a plethora of non-autophagic roles for the Atg proteins.

Selective types of autophagy

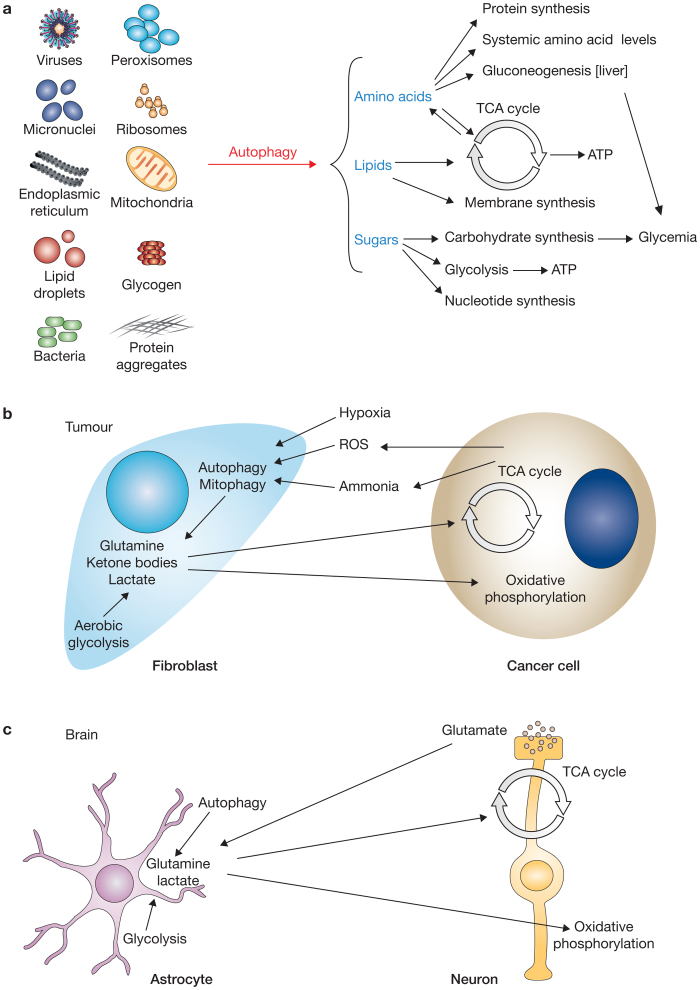

Autophagy has long been considered a non-selective process for bulk degradation of either long-lived proteins or cytoplasmic components during nutrient deprivation. Numerous types of selective autophagy have been uncovered recently11. Under specific conditions, autophagosomes can thus exclusively sequester and degrade mitochondria, peroxisomes, endoplasmic reticulum, endosomes, lysosomes, lipid droplets, secretory granules, cytoplasmic aggregates, ribosomes and invading pathogens (Fig. 2a). Protein complexes in signalling cascades such as the inflammasome are also regulated through selective autophagy12. In this case, it seems that their degradation does not always require the stimulation of autophagy per se, but rather the induction of their targeting to the autophagosomes formed by basal autophagy.

Figure 2. Relationship between autophagy and the main metabolic pathways.

(a) The catabolic products of the intracellular structures that are targeted by autophagosomes, such as amino acids, lipids and sugars, are used for anabolic reactions to generate new proteins, glycans, oligonucleotides and membranes to sustain cell functions. Amino acids can also be used to maintain their systemic levels and for de novo synthesis of glycogen (gluconeogenesis) in the liver. Lipids and amino acids can enter the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and oxidative phosphorylation to generate energy in the form of ATP. Sugars can also be metabolized to generate ATP through glycolysis and to maintain systemic glucose levels. (b,c) Metabolic compartmentalization between different cell types. (b) Inside tumours, hypoxia and oxidative stress trigger autophagy and mitophagy in the stromal fibroblasts. This induces a metabolic switch towards aerobic glycolysis (known as the Warburg effect), leading to the production of lactate and other metabolites that are liberated into the intracellular space and reabsorbed by tumour cells. A more oxidative metabolism in these cells generates oxidative stress and ammonia (from glutaminolysis), which signals back to fibroblasts to further stimulate autophagy. (c) In brain tissue, astrocytes produce lactate from glucose through glycolysis and glutamine through autophagy. These metabolites are taken up by neurons and oxidized to generate ATP. Moreover, the neurotransmitter glutamate, released by neurons, can be retransformed into glutamine by astrocytes.

Selective autophagy relies on cargo-specific autophagy receptors that facilitate cargo sequestration into autophagosomes. Autophagy receptors interact directly with the structure that needs to be specifically eliminated by autophagy, as well as the pool of the Atg8 (yeast homologue of mammalian LC3) protein family members present in the internal surface of the growing autophagosomes11,13. The latter interaction is mostly mediated through a specific amino acid sequence present in the autophagy receptors and commonly referred to as the LC3-interacting region (LIR) or the Atg8-interacting (AIM) motif13,14.

The study of the biosynthetic transport route present in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the cytosol-to-vacuole targeting (Cvt) pathway15, has been pivotal in understanding selective autophagy in other eukaryotic cells. This pathway mediates the delivery into the vacuole lumen of three hydrolases that are all part of a large oligomeric structure. The recruitment of this cargo into autophagosomes depends on Atg11 and the autophagy receptor Atg19 (Atg11 and Atg19 are not required for starvation-induced autophagy). The distribution of Atg19 on the surface of the cargo and its interaction with Atg8 through an LIR motif allow the hermetic formation of a double-membrane vesicle around the targeted structure. Atg32 and Atg36 are yeast autophagy receptors for mitochondria and peroxisomes, respectively; they are found on the surface of these organelles and seem to operate in the same way as Atg19 (refs 16,17,18).

An emerging theme in high eukaryotes is that structures targeted for destruction by autophagy are often ubiquitinated, and a series of autophagy receptors with a ubiquitin-binding domain and an LIR motif (such as p62/SQSTM1, NBR1, NDP52 or optineurin) promote their engulfment into autophagosomes13,19. With ubiquitination being a key regulatory element during selective types of autophagy, E3 ligases and/or their eventual adaptors and regulators must have central roles in these processes. However, only a handful of these molecules have been identified so far. Those include the Pink1 kinase, the Parkin ligase and the mitochondrial outer membrane protein FUNDC (all of which were linked to mitophagy20,21,22), and the SMURF1 ligase and the STING adaptor, which participate in the clearance of pathogens23,24.

Post-translational modifications in the regulation of autophagy

As for all degradative pathways, regulation is key to specifically 'switch on' autopahgy for the limited time that it is required. Several signalling molecules and cascades modulate autophagy in response to numerous cellular and environmental cues25,26. The best-characterized regulator of autophagy is mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1). This kinase negatively regulates autophagy by inhibiting the activity of the Atg1 (ULK1) complex through direct phosphorylation. The activity of mTORC1 is stimulated by a variety of anabolic inputs, which include the energy and nutrient status of the cell as well as the presence of amino acids and growth factors. Conversely, mTORC1 is inhibited when amino acids are scarce, growth factor signalling is reduced and/or ATP concentrations fall, and this results in a de-repression of autophagy26.

The mTOR-dependent phosphorylation of the Atg1 (ULK1) complex and the ubiquitination-like reactions are central during autophagosome biogenesis through the generation of the Atg12–Atg5 and the Atg8–phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) conjugates. Although these were initially considered to be the only post-translational modifications in autophagy, proteins linked to the Atg machinery are now known to be substrates for a wide range of post-translational modifications such as phosphorylation, ubiquitination and acetylation27.

Yeast protein kinase A (PKA) phosphorylates Atg13 in the presence of nutrients to prevent its association with the PAS (ref. 28). In mammalian cells, ULK1 is directly phosphorylated by the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) in response to energy restriction29,30. Thus, AMPK triggers autophagy by both positively regulating the Atg1/ (ULK1) complex and inhibiting mTOR (ref. 25).

The phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase (PI(3)K) complex I is also a major point of regulation for the kinases that modulate autophagy induction. Beclin 1 is one of the subunits of the PI(3)K complex I and its incorporation into this complex, which is essential to stimulate PtdIns3P synthesis, is usually kept in check by its association with other proteins, such as Bcl-2, 14-3-3 or the intermediate filament protein vimentin 1 (VMP1). The phosphorylation of beclin 1 by the death-associated protein kinase (DAPK) or phosphorylation of Bcl-2 by the c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) triggers the dissociation of the beclin-1–Bcl-2 complex in response to various stimuli, allowing beclin 1 to associate with the PI(3)K complex I (refs 31,32). More recently, it has been shown that beclin 1 phopshorylation by Akt and protein kinase B (PKB) inhibits autophagy by favouring the interaction of beclin 1 with 14-3-3 and the vimentin intermediate filament protein 1 (ref. 33). Furthermore, AMPK stimulates autophagy in response to glucose starvation by phosphorylating beclin 1 on a different residue to that of the inhibitory kinases, a modification that promotes its incorporation into the PI(3)K complex I (ref. 34).

Downstream of the ULK and the PI(3)K complexes, phosphorylation can regulate the activity of LC3-II. When phosphorylated by PKA or protein kinase C (PKC), LC3 becomes inoperative in autophagosome formation28,35. How exactly phosphorylation inhibits LC3 function remains to be elucidated. The PKA site is highly conserved in the human, mouse and rat isoforms of LC3, but is not present in yeast Atg8 (ref. 28).

Phosphorylation of autophagy receptors also increases their affinity for binding to substrates and LC3 during selective types of autophagy. Phosphorylation of p62 by the casein kinase 2 favours its interaction with ubiquitinated proteins36, whereas phosphorylation of optineurin by the TANK-binding kinase 1 enhances its affinity for LC3 to promote the elimination of cytosolic Salmonella37.

Although ubiquitination plays an important role in the selection of the cargo targeted for destruction during selective types of autophagy, there are so far no indications that this post-translational modification occurs on Atg proteins. Recently, the formation of an Atg12–Atg3 conjugate though the action of Atg7 and the autocatalytic activity of Atg3 has been described in mammalian cells38. This conjugate plays a role in cell death pathways and in the control of mitochondrial expansion.

An initial study showed that some of the Atg proteins are acetylated39 and an analysis of the acetylome has revealed the importance of this modification in the regulation of autophagy. Atg5, Atg7, LC3 and Atg12 are acetylated by the p300 acetyltransferase when cells are maintained in nutrient-rich media and deacetylated by Sirt1 in response to starvation, an event necessary to induce autophagy40,41. More recently, the acetylation of Atg3 by Esa1 in yeast and by the Esa1 orthologue TIP60 in mammals under autophagy-inducing conditions has been shown to promote the interaction between Atg3 and Atg8, which is required for Atg8 lipidation42. TIP60 also acetylates ULK1 in a glycogen synthase kinase-dependent manner in response to growth factor deprivation43. Thus, ULK1 is activated by either phosphorylation or acetylation in response to amino acid (or glucose) and growth factor deprivation, respectively44.

Autophagy and Atg proteins in membrane transport and secretion

Until recently, the Cvt pathway has been the only transport pathway depending on Atg proteins that is not associated with degradation. The Atg machinery has now been shown to participate in the release of cargoes into the extracellular medium, shedding light on the mechanism of a few types of unconventional protein secretion45,46,47. This mechanism seems to be involved in the secretion of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1 and IL-18 in mammalian cells47. This process depends on Atg5, the inflammasome, the peripheral Golgi protein GRASP55 and the small GTPase Rab8a. This autophagy-based unconventional secretion mechanism can probably be extended to modulators of the immune response such as HMGB1 (ref. 47). The morphology of the autophagy-related organelles involved in secretion and the molecular basis for their formation, however, remain to be identified. In yeast, the putative carriers for this type of secretion were suggested to come from a hitherto-unknown compartment for unconventional protein secretion (aptly named CUPS)48. Like the PAS, CUPS also contains PtdIns3P as well as Atg8 and Atg9. However, although these two Atg proteins are required for the generation of the PAS, they seem to be unnecessary for CUPS formation. In mammalian systems, this mode of secretion could explain the non-lytic release of viruses that subverts the autophagy machinery for egression49 or the expulsion of cellular material by autophagosomes at the late stages of reticulocyte maturation into erythrocytes50.

In oncogene-induced senescent cells, a specialized compartment known as the mTOR-autophagy special coupling compartment (TASCC) is juxtaposed next to the Golgi apparatus and stimulates the extracellular release of a specific subset of proteins through the conventional secretory pathway51. Lysosomes and autophagosomes (which supply lysosomes with proteins) both accumulate adjacent to the TASCC. Importantly, mTOR located at the lysosomal surface is activated by amino acid efflux from lysosomes and positively regulates protein synthesis and cell growth52. Interactions between TASCC, lysosomes and autophagosomes could be key in coordinating cell metabolism by coupling autophagic degradation with both the synthesis and secretion of proteins. TASCC-like structures have also been observed in non-senescent cells, suggesting that this mechanism for protein secretion may be widely used51.

Autophagy and Atg proteins, including the Atg8 conjugate LC3-II, also modulate secretion in several specialized tissues including the middle ear, osteoclasts, mast cells, Paneth cells and pancreatic β-cells53. Independently of autophagosome formation, LC3-II mediates the fusion of vesicular carriers containing the protease cathepsin K with the ruffled border of osteoclasts, which is an important step in bone resorption54. This situation mirrors the recruitment of LC3-II on to phagosomes to enhance their fusion with lysosomes in phagocytic cells55. The role of LC3-II and other members of the Atg8 protein family in these processes probably relies on their capacities in mediating tethering or fusion of vesicular structures56,57 and/or binding the cytoskeleton58.

Autophagy as a regulator of tissue microenvironment metabolism

Starvation is the classical autophagy stimulus that induces the degradation of intracellular components to generate metabolites essential to maintain cell viability (Fig. 2a), which are used to fuel mitochondrial respiration and ATP production59,60. In yeast, amino acids generated by autophagy can be used to sustain new protein synthesis and to maintain mitochondrial functions under nutrient deprivation61. Amino acids generated in the liver by autophagy are used for gluconeogenesis to maintain systemic glycemia under starvation (Fig. 2a)62. Moreover, in addition to the activity of hepatic triglyceride lipases, the selective degradation of lipid droplets in the liver by autophagy also produces free fatty acids from triglycerides63.

The role of autophagy in cancer metabolism has been the subject of intense investigation. Autophagy protects cancer cells from metabolic stress (such as decreased nutrient availability and hypoxic conditions) by reducing oxidative stress and maintaining genomic stability64. It is now clear that cancer cells reprogram their metabolism to support their rapid proliferation and growth. To increase their nutrient uptake, cancer cells also perform aerobic glycolysis to oxidize glucose into lactate to produce ATP and intermediary metabolites used for anabolic reactions that sustain cell growth65. This metabolic switch includes the expression of specific isoforms of glycolytic enzymes, as well as expression of enzymes metabolizing amino acids and lipids, with distinct enzymatic activities and substrate preferences66. In this context, the activation of the hypoxia-responsive factor HIF-1 regulates the expression of many glycolytic enzymes and also induces mitophagy67. A recent metabolomic study has demonstrated that cells can maintain minimal levels of mitochondrial respiration to produce ATP under hypoxia (1% oxygen), and these cells also display increased levels of autophagy activity and intermediates resulting from protein and lipid catabolism68. Autophagy inhibition under these conditions reduces intracellular ATP levels and induces cell death, indicating that the degradation products resulting from autophagy are able to fuel the tricarboxylic acid cycle for ATP synthesis to maintain cell viability even under low oxygen conditions68. This cyto-protective role of autophagy under hypoxic conditions may be modulated through microRNA-dependent regulation of ATG7 expression in hepatic tumour cell lines and in vivo xenographs69. It is still unknown whether the autophagy-dependent degradation of mitochondria is an additional mechanism responsible for metabolic reprogramming, although observations in non-tumorigenic cells would support this notion70. Indeed, overexpression of the RCAN1-1L protein induces mitophagy and a shift from oxidative to glycolytic metabolism in neuronal cells70.

Metabolic coupling, a phenomenon in which two different cell types differentially coordinate their metabolism, has been associated with autophagy and has been observed in several tissues including tumours and brain tissue (Fig. 2b,c)71. Tumours are composed of several cell types, and it has been postulated that metabolic coupling is essential for tumour development. In particular, fibroblasts perform aerobic glycolysis inside tumours and display an increased expression of glycolytic enzymes, elevated HIF-1 activity, autophagy and mitophagy71. Metabolites resulting from elevated autophagy and glycolysis in these fibroblasts, such as lactate, ketone bodies and amino acids, are released into the tumour microenvironment and sequestered by cancer cells to fuel the oxidative phosphorylation necessary to sustain tumour growth71. The autophagy stimulation in fibroblasts also results in increased senescence, which boosts both the production of ketone bodies and mitochondrial metabolism in adjacent cancer cells to promote metastasis72. In contrast to these positive effects of autophagy on tumour growth, autophagy upregulation in the cancer cells themselves actually inhibit tumour growth72. Other metabolites, such as the ammonia generated from glutaminolysis in cancer cells, stimulate autophagy in neighbouring cells73.

Similar features of metabolism coupling have been observed in the brain, where astrocytes and neurons exchange metabolites to support their cellular functions (Fig. 2c). Impairment of lysosomal functions and autophagy affects specific cell types such as astrocytes, preventing them from supporting and protecting neighbouring neurons, ultimately resulting in cortical neurodegeneration in vivo74.

Together, these data indicate that autophagy in specific cell types could be key in regulating the survival and growth of the surrounding tissue (Fig. 2c).

The role of ATG genes in other cellular processes

Analysis of the Atg protein interactome suggested that they can function in cellular pathways independently of their role in autophagy75. This emerging topic has been recently reviewed76, and some of the non-autophagic functions of ATG genes are shown in Table 2. Some modules involved in autophagosome formation, such as the two conjugation systems (ATG5–ATG12 and LC3–PE) and the PI(3)K complex I, are recruited to the phagosomal membrane to promote the fusion between phagosomes and lysosomes during phagocytosis triggered by the engagement of Toll-like receptors55. These conjugation systems are also required for the generation of the osteoclast ruffled border, a key structure for bone resorption54.

Table 2.

Detailed list of the ATG genes that have been implicated in non-autophagic pathways

| Gene | Autophagy-independent pathways | References |

|---|---|---|

| ULK1 | Brucella vacuole biogenesis | 80 |

| ATG3 | Mitochondrial homeostasis (conjugated to Atg12) | 38 |

| ATG4B | Osteoclast bone resorption | 54 |

| ATG5 | Osteoclast bone resorption; phagocytosis; IFN-α/IFN-β/IFN-γ antiviral response (conjugated to Atg12); pro-apoptotic role | 54,55,77,78,84,94 |

| Beclin 1 | Phagocytosis; Brucella vacuole biogenesis | 80,95 |

| ATG7 | Osteoclast bone resorption; phagocytosis; IFN-γ antiviral response | 54,55,78,94 |

| LC3 | Osteoclast bone resorption; tuning of endoplasmic-reticulum-associated degradation; coronavirus infection | 54,55,81,82 |

| ATG12 | Mitochondrial apoptosis; IFN-α/IFN-β/IFN-γ antiviral response (conjugated to Atg5); mitochondrial homeostasis (conjugated to Atg3) | 38,77,78,83 |

| ATG14 | Brucella vacuole biogenesis | 80 |

| ATG16 | IFN-γ antiviral response | 78 |

| p150 | Brucella vacuole biogenesis | 80 |

| PtdIns3PKC3 | Phagocytosis; Brucella vacuole biogenesis | 80,94 |

The ATG5–ATG12/ATG16L1 complex, independently of the LC3 conjugation system, can modulate the innate viral immune response. ATG5–ATG12 suppresses the type I interferon (IFN) production by direct association with the retinoic-acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I) and IFN-β promoter stimulator (IPS-1)77. This complex is also required for type II IFN-mediated host defense against norovirus by inhibiting the formation of its membranous replication complex78. Similarly, ATG5 is required for the clearance of the parasite Toxoplasma gondii in macrophages79.

Complexes acting upstream of the conjugation systems, such as the ULK1 complex and PI(3)K complex I, are necessary for the intracellular cycle of the bacterium Brucella abortus. They are used to subvert clearance by participating in the formation of a vacuole containing the bacteria that promote infection80.

In addition to the conventional ATG12–ATG5 cassette, an ATG12–ATG3 conjugate has been shown to regulate mitochondria homeostasis and cell death without affecting the formation of autophagosomes in response to starvation38. Both LC3 and ATG12 can also function independently of their conventional conjugation to PE and ATG5, respectively. LC3-I is involved in the formation of carriers derived from the endoplasmic reticulum, called EDEMosomes81, a pathway hijacked by coronaviruses to form structures needed for the transcription and replication of the viral genome82. ATG12 is a positive mediator of mitochondrial apoptosis by inactivating members of the pro-survival Bcl-2 protein family. The activity of ATG12 is independent of ATG5 or ATG3, and requires a BH3-like motif in ATG12 (ref. 83). ATG proteins also act in an autophagy-independent manner following proteolytic processing. For example, ATG5 cleavage by calpains generates a pro-apoptotic fragment that interferes with the anti-apoptotic activity of Bcl-xL (ref. 84). Moreover, beclin 1 processing by caspase 3 generates two fragments that do not have the capacity to induce autophagy85,86. The C-terminal fragment resulting from this processing localizes to mitochondria and sensitizes cells to apoptosis86. Thus, similarly to proteins involved in apoptosis that also function beyond apoptosis87, ATG components, as well as other proteins involved in autophagy such as AMBRA1, VPS34 and p62 (for which autophagy-independent roles are not discussed here), are engaged in non-autophagic functions. This notion has to be taken into account when we experimentally explore the role of autophagy in vivo on the basis of the ablation of a single ATG gene.

Conclusions and perspectives

Despite the progresses made in our understanding of autophagy, numerous key aspects of this catabolic pathway remain enigmatic. For example, we still know very little about the regulation of basal autophagy, which operates under normal growing conditions. The modulation of this process engages actin filaments and the histone deacetylase HDAC6, which are both dispensable for autophagosome maturation under starvation conditions88.

The coordination of Atg protein recruitment to the PAS from different membrane origins, as well as their hierarchical assembly at this specialized site, are aspects of the autophagosome biogenesis that should be carefully considered in the future. Although a hierarchical recruitment of the Atg proteins has been proposed for yeast on a genetic basis89, their temporal association and the functional consequences of the hierarchy remain to be investigated. Examination of the selective sequestration of mitochondria or Salmonella by autophagosomes has indicated a different hierarchy than the one postulated, according to which groups or clusters of Atg proteins could independently associate to form the PAS (refs 90,91). Similarly, further analyses of the different forms of non-canonical autophagy described to date, which only require a subset of Atg proteins, or of the autophagy-independent functions of Atg proteins, can yield a better understanding of the functional importance of these factors during the generation of autophagosomes92.

It remains to be seen why metazoans possess several isoforms of the same Atg protein, which apparently have identical functions. For example, the human genome contains 6 homologues of the single yeast Atg8 protein, yet the role of these counterparts remains to be elucidated. Some members of this protein family, that is, GABARAPL1 and GABARAPL2, were shown to participate in autophagosome closure57, whereas LC3C also acts as a specific receptor during selective antibacterial autophagy93.

The importance of autophagy in many aspects of physiology is now recognised. Not surprisingly, defects in this process are intimately associated with numerous human diseases. Better knowledge of the molecular bases of autophagy and of its control by physiological regulators, from cytokines and hormones to dietary restriction or physical exercise, may provide simple and non-invasive ways to modulate this pathway for preventive or therapeutic interventions in the future25.

Acknowledgements

P.B. is supported by the SAF-2009-08086 and SAF-2012-36079 grants. F.R. is supported by the ECHO (700.59.003), ALW Open Program (821.02.017 and 822.02.014), DFG-NWO cooperation (DN82-303) and ZonMW VICI (016.130.606) grants. P.C. is supported by INSERM and grants from ANR and INCa.

Contributor Information

Patricia Boya, Email: patricia.boya@csic.es.

Fulvio Reggiori, Email: F.Reggiori@umcutrecht.nl.

Patrice Codogno, Email: patrice.codogno@inserm.fr.

References

- 1.Yang Z, Klionsky DJ. Eaten alive: a history of macroautophagy. Nat. Cell Biol. 2010;12:814–822. doi: 10.1038/ncb0910-814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mizushima N, Yoshimori T, Ohsumi Y. The role of Atg proteins in autophagosome formation. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2011;27:107–132. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rubinsztein DC, Shpilka T, Elazar Z. Mechanisms of autophagosome biogenesis. Curr. Biol. 2012;22:R29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Axe EL, et al. Autophagosome formation from membrane compartments enriched in phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate and dynamically connected to the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Cell Biol. 2008;182:685–701. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200803137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hayashi-Nishino M, et al. A subdomain of the endoplasmic reticulum forms a cradle for autophagosome formation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2009;11:1433–1437. doi: 10.1038/ncb1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yla-Anttila P, Vihinen H, Jokitalo E, Eskelinen EL. 3D tomography reveals connections between the phagophore and endoplasmic reticulum. Autophagy. 2009;5:1180–1185. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.8.10274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hailey DW, et al. Mitochondria supply membranes for autophagosome biogenesis during starvation. Cell. 2010;141:656–667. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deretic V, Levine B. Autophagy, immunity, and microbial adaptations. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:527–549. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mizushima N, Levine B, Cuervo AM, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy fights disease through cellular self-digestion. Nature. 2008;451:1069–1075. doi: 10.1038/nature06639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levine B, Kroemer G. Autophagy in the pathogenesis of disease. Cell. 2008;132:27–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reggiori F, Komatsu M, Finley K, Simonsen A. Autophagy: more than a nonselective pathway. Int. J. Cell Biol. 2012;2012:219625. doi: 10.1155/2012/219625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shi CS, et al. Activation of autophagy by inflammatory signals limits IL-1β production by targeting ubiquitinated inflammasomes for destruction. Nat. Immunol. 2012;13:255–263. doi: 10.1038/ni.2215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johansen T, Lamark T. Selective autophagy mediated by autophagic adapter proteins. Autophagy. 2011;7:279–296. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.3.14487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noda NN, Ohsumi Y, Inagaki F. Atg8-family interacting motif crucial for selective autophagy. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:1379–1385. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lynch-Day MA, et al. Trs85 directs a Ypt1 GEF, TRAPPIII, to the phagophore to promote autophagy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:7811–7816. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000063107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Motley AM, Nuttall JM, Hettema EH. Pex3-anchored Atg36 tags peroxisomes for degradation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 2012;31:2852–2868. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanki T, Wang K, Cao Y, Baba M, Klionsky DJ. Atg32 is a mitochondrial protein that confers selectivity during mitophagy. Dev. Cell. 2009;17:98–109. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okamoto K, Kondo-Okamoto N, Ohsumi Y. Mitochondria-anchored receptor Atg32 mediates degradation of mitochondria via selective autophagy. Dev. Cell. 2009;17:87–97. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shaid S, Brandts CH, Serve H, Dikic I. Ubiquitination and selective autophagy. Cell Death Differ. 2013;20:21–30. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2012.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vives-Bauza C, et al. PINK1-dependent recruitment of Parkin to mitochondria in mitophagy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:378–383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911187107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Narendra D, Tanaka A, Suen DF, Youle RJ. Parkin is recruited selectively to impaired mitochondria and promotes their autophagy. J. Cell Biol. 2008;183:795–803. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200809125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu L, et al. Mitochondrial outer-membrane protein FUNDC1 mediates hypoxia-induced mitophagy in mammalian cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2012;14:177–185. doi: 10.1038/ncb2422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Watson RO, Manzanillo PS, Cox JS. Extracellular M. tuberculosis DNA targets bacteria for autophagy by activating the host DNA-sensing pathway. Cell. 2012;150:803–815. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Orvedahl A, et al. Image-based genome-wide siRNA screen identifies selective autophagy factors. Nature. 2011;480:113–117. doi: 10.1038/nature10546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rubinsztein DC, Codogno P, Levine B. Autophagy modulation as a potential therapeutic target for diverse diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2012;11:709–730. doi: 10.1038/nrd3802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meijer AJ, Codogno P. Autophagy: regulation and role in disease. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2009;46:210–240. doi: 10.1080/10408360903044068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McEwan DG, Dikic I. The Three Musketeers of Autophagy: phosphorylation, ubiquitylation and acetylation. Trends Cell Biol. 2011;21:195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stephan JS, Yeh YY, Ramachandran V, Deminoff SJ, Herman PK. The Tor and PKA signaling pathways independently target the Atg1/Atg13 protein kinase complex to control autophagy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:17049–17054. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903316106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Egan DF, et al. Phosphorylation of ULK1 (hATG1) by AMP-activated protein kinase connects energy sensing to mitophagy. Science. 2011;331:456–461. doi: 10.1126/science.1196371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim J, Kundu M, Viollet B, Guan KL. AMPK and mTOR regulate autophagy through direct phosphorylation of Ulk1. Nat. Cell Biol. 2011;13:132–141. doi: 10.1038/ncb2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wei Y, Pattingre S, Sinha S, Bassik M, Levine B. JNK1-mediated phosphorylation of Bcl-2 regulates starvation-induced autophagy. Mol. Cell. 2008;30:678–688. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zalckvar E, et al. DAP-kinase-mediated phosphorylation on the BH3 domain of beclin 1 promotes dissociation of beclin 1 from Bcl-X(L) and induction of autophagy. EMBO Rep. 2009;30:30. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang RC, et al. Akt-mediated regulation of autophagy and tumorigenesis through Beclin 1 phosphorylation. Science. 2012;338:956–959. doi: 10.1126/science.1225967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim J, et al. Differential regulation of distinct Vps34 complexes by AMPK in nutrient stress and autophagy. Cell. 2013;152:290–303. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cherra SJ, 3rd., et al. Regulation of the autophagy protein LC3 by phosphorylation. J. Cell Biol. 2010;190:533–539. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201002108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matsumoto G, Wada K, Okuno M, Kurosawa M, Nukina N. Serine 403 phosphorylation of p62/SQSTM1 regulates selective autophagic clearance of ubiquitinated proteins. Mol. Cell. 2011;44:279–289. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wild P, et al. Phosphorylation of the autophagy receptor optineurin restricts Salmonella growth. Science. 2011;333:228–233. doi: 10.1126/science.1205405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Radoshevich L, et al. ATG12 conjugation to ATG3 regulates mitochondrial homeostasis and cell death. Cell. 2010;142:590–600. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morselli E, et al. Spermidine and resveratrol induce autophagy by distinct pathways converging on the acetylproteome. J. Cell Biol. 2011;192:615–629. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201008167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee IH, et al. A role for the NAD-dependent deacetylase Sirt1 in the regulation of autophagy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:3374–3379. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712145105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee IH, Finkel T. Regulation of autophagy by the p300 acetyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:6322–6328. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807135200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yi C, et al. Function and molecular mechanism of acetylation in autophagy regulation. Science. 2012;336:474–477. doi: 10.1126/science.1216990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lin SY, et al. GSK3-TIP60-ULK1 signaling pathway links growth factor deprivation to autophagy. Science. 2012;336:477–481. doi: 10.1126/science.1217032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hamai A, Codogno P. New targets for acetylation in autophagy. Sci. Signal. 2012;5:pe29. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2003187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Duran JM, Anjard C, Stefan C, Loomis WF, Malhotra V. Unconventional secretion of Acb1 is mediated by autophagosomes. J. Cell Biol. 2010;188:527–536. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200911154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Manjithaya R, Anjard C, Loomis WF, Subramani S. Unconventional secretion of Pichia pastoris Acb1 is dependent on GRASP protein, peroxisomal functions, and autophagosome formation. J. Cell Biol. 2010;188:537–546. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200911149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dupont N, et al. Autophagy-based unconventional secretory pathway for extracellular delivery of IL-1β. Embo J. 2011;30:4701–4711. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bruns C, McCaffery JM, Curwin AJ, Duran JM, Malhotra V. Biogenesis of a novel compartment for autophagosome-mediated unconventional protein secretion. J. Cell Biol. 2011;195:979–992. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201106098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jackson WT, et al. Subversion of cellular autophagosomal machinery by RNA viruses. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e156. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Griffiths RE, et al. Maturing reticulocytes internalize plasma membrane in glycophorin A-containing vesicles that fuse with autophagosomes before exocytosis. Blood. 2012;119:6296–6306. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-376475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Narita M, et al. Spatial coupling of mTOR and autophagy augments secretory phenotypes. Science. 2011;332:966–970. doi: 10.1126/science.1205407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zoncu R, et al. mTORC1 senses lysosomal amino acids through an inside-out mechanism that requires the vacuolar H(+)-ATPase. Science. 2011;334:678–683. doi: 10.1126/science.1207056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Deretic V, Jiang S, Dupont N. Autophagy intersections with conventional and unconventional secretion in tissue development, remodeling and inflammation. Trends Cell Biol. 2012;22:397–406. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2012.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.DeSelm CJ, et al. Autophagy proteins regulate the secretory component of osteoclastic bone resorption. Dev. Cell. 2011;21:966–974. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sanjuan MA, et al. Toll-like receptor signalling in macrophages links the autophagy pathway to phagocytosis. Nature. 2007;450:1253–1257. doi: 10.1038/nature06421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nakatogawa H, Ichimura Y, Ohsumi Y. Atg8, a ubiquitin-like protein required for autophagosome formation, mediates membrane tethering and hemifusion. Cell. 2007;130:165–178. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weidberg H, et al. LC3 and GATE-16 N termini mediate membrane fusion processes required for autophagosome biogenesis. Dev. Cell. 2011;20:444–454. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Monastyrska I, Rieter E, Klionsky DJ, Reggiori F. Multiple roles of the cytoskeleton in autophagy. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 2009;84:431–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2009.00082.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mellén MA, de la Rosa EJ, Boya P. The autophagic machinery is necessary for removal of cell corpses from the developing retinal neuroepithelium. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:1279–1290. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Qu X, et al. Autophagy gene-dependent clearance of apoptotic cells during embryonic development. Cell. 2007;128:931–946. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Suzuki SW, Onodera J, Ohsumi Y. Starvation induced cell death in autophagy-defective yeast mutants is caused by mitochondria dysfunction. PloS One. 2011;6:e17412. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ezaki J, et al. Liver autophagy contributes to the maintenance of blood glucose and amino acid levels. Autophagy. 2011;7:727–736. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.7.15371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Singh R, et al. Autophagy regulates lipid metabolism. Nature. 2009;458:1131–1135. doi: 10.1038/nature07976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.White E. Deconvoluting the context-dependent role for autophagy in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2012;12:401–410. doi: 10.1038/nrc3262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lunt SY, Vander Heiden MG. Aerobic glycolysis: meeting the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2011;27:441–464. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Porporato PE, Dhup S, Dadhich RK, Copetti T, Sonveaux P. Anticancer targets in the glycolytic metabolism of tumors: a comprehensive review. Front Pharmacol. 2011;2:49. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2011.00049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Semenza GL. HIF-1: upstream and downstream of cancer metabolism. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2010;20:51–56. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Frezza C, et al. Metabolic profiling of hypoxic cells revealed a catabolic signature required for cell survival. PloS One. 2011;6:e24411. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chang Y, et al. miR-375 inhibits autophagy and reduces viability of hepatocellular carcinoma cells under hypoxic conditions. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:177–187. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ermak G, et al. Chronic expression of RCAN1-1L protein induces mitochondrial autophagy and metabolic shift from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis in neuronal cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:14088–14098. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.305342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pavlides S, et al. Warburg meets autophagy: cancer-associated fibroblasts accelerate tumor growth and metastasis via oxidative stress, mitophagy, and aerobic glycolysis. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2012;16:1264–1284. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Capparelli C, et al. Autophagy and senescence in cancer-associated fibroblasts metabolically supports tumor growth and metastasis via glycolysis and ketone production. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:2285–2302. doi: 10.4161/cc.20718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Eng CH, Abraham RT. Glutaminolysis yields a metabolic by-product that stimulates autophagy. Autophagy. 2010;6:968–970. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.7.13082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Di Malta C, Fryer JD, Settembre C, Ballabio A. Astrocyte dysfunction triggers neurodegeneration in a lysosomal storage disorder. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:E2334–2342. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209577109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Behrends C, Sowa ME, Gygi SP, Harper JW. Network organization of the human autophagy system. Nature. 2010;466:68–76. doi: 10.1038/nature09204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Subramani S, Malhotra V. Non-autophagic roles of autophagy-related proteins. EMBO Rep. 2013;14:143–151. doi: 10.1038/embor.2012.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jounai N, et al. The Atg5 Atg12 conjugate associates with innate antiviral immune responses. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:14050–14055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704014104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hwang S, et al. Nondegradative role of Atg5-Atg12/Atg16L1 autophagy protein complex in antiviral activity of interferon gamma. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;11:397–409. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhao Z, et al. Autophagosome-independent essential function for the autophagy protein Atg5 in cellular immunity to intracellular pathogens. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;4:458–469. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Starr T, et al. Selective subversion of autophagy complexes facilitates completion of the Brucella intracellular cycle. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;11:33–45. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cali' T, Galli C, Olivari S, Molinari M. Segregation and rapid turnover of EDEM1 by an autophagy-like mechanism modulates standard ERAD and folding activities. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008;371:405–410. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.04.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Reggiori F, et al. Coronaviruses hijack the LC3-I-positive EDEMosomes, ER-derived vesicles exporting short-lived ERAD regulators, for replication. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;7:500–508. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rubinstein AD, Eisenstein M, Ber Y, Bialik S, Kimchi A. The autophagy protein Atg12 associates with anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family members to promote mitochondrial apoptosis. Mol. Cell. 2011;44:698–709. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yousefi S, et al. Calpain-mediated cleavage of Atg5 switches autophagy to apoptosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006;8:1124–1132. doi: 10.1038/ncb1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Luo S, Rubinsztein DC. Apoptosis blocks Beclin 1-dependent autophagosome synthesis: an effect rescued by Bcl-xL. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17:268–277. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wirawan E, et al. Caspase-mediated cleavage of Beclin-1 inactivates Beclin-1-induced autophagy and enhances apoptosis by promoting the release of proapoptotic factors from mitochondria. Cell Death Dis. 2010;1:e18. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2009.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Galluzzi L, Kepp O, Trojel-Hansen C, Kroemer G. Non-apoptotic functions of apoptosis-regulatory proteins. EMBO Rep. 2012;13:322–330. doi: 10.1038/embor.2012.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lee JY, et al. HDAC6 controls autophagosome maturation essential for ubiquitin-selective quality-control autophagy. Embo J. 2010;29:969–980. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Suzuki K, Kubota Y, Sekito T, Ohsumi Y. Hierarchy of Atg proteins in pre-autophagosomal structure organization. Genes Cells. 2007;12:209–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2007.01050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Itakura E, Kishi-Itakura C, Koyama-Honda I, Mizushima N. Structures containing Atg9A and the ULK1 complex independently target depolarized mitochondria at initial stages of Parkin-mediated mitophagy. J. Cell Sci. 2012;125:1488–1499. doi: 10.1242/jcs.094110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kageyama S, et al. The LC3 recruitment mechanism is separate from Atg9L1-dependent membrane formation in the autophagic response against Salmonella. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2011;22:2290–2300. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-11-0893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Codogno P, Mehrpour M, Proikas-Cezanne T. Canonical and non-canonical autophagy: variations on a common theme of self-eating? Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011;13:7–12. doi: 10.1038/nrm3249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.von Muhlinen N, et al. LC3C, bound selectively by a noncanonical LIR motif in NDP52, is required for antibacterial autophagy. Mol. Cell. 2012;48:329–342. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Florey O, Kim SE, Sandoval CP, Haynes CM, Overholtzer M. Autophagy machinery mediates macroendocytic processing and entotic cell death by targeting single membranes. Nat. Cell Biol. 2011;13:1335–1343. doi: 10.1038/ncb2363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Martinez J, et al. Microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 alpha (LC3)-associated phagocytosis is required for the efficient clearance of dead cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:17396–17401. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113421108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]