This survey study examines national trends in the care of different mental health problems and in different treatment settings among adolescents who responded to the 2005-2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health.

Key Points

Question

How did mental health problems for which adolescents received care and the service settings where they received care change from 2005 to 2018?

Findings

In this survey study of 47 090 adolescents, a greater proportion of adolescents in more recent years received care for internalizing problems, such as depressive symptoms or suicidal ideations, whereas a smaller proportion received care for externalizing and relationship problems. Care in inpatient and outpatient mental health settings increased, and care in school counseling services modestly decreased.

Meaning

These findings suggest that the demand for care of internalizing problems and for care in mental health specialty settings has increased among US adolescents in the past decade.

Abstract

Importance

The prevalence of adolescent depression and other internalizing mental health problems has increased in recent years, whereas the prevalence of externalizing behaviors has decreased. The association of these changes with the use of mental health services has not been previously examined.

Objective

To examine national trends in the care of different mental health problems and in different treatment settings among adolescents.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Data for this survey study were drawn from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, an annual cross-sectional survey of the US general population. This study focused on adolescent participants aged 12 to 17 years interviewed from January 1, 2005, to December 31, 2018. Data were reported as weighted percentages and adjusted odds ratios (aORs) and analyzed from July 20 to December 1, 2019.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Time trends in 12-month prevalence of any mental health treatment or counseling in a wide range of settings were examined overall and for different sociodemographic groups, types of mental health problems (internalizing, externalizing, relationship, and school related), and treatment settings (inpatient mental health, outpatient mental health, general medical, and school counseling). Trends in the number of visits and nights in inpatient settings were also examined.

Results

A total of 47 090 of the 230 070 adolescents across survey years (19.7%) received mental health care. Of these, 57.5% were female; 31.3%, aged 12 to 13 years; 35.8%, aged 14 to 15 years; and 32.9%, aged 16 to 17 years. The overall prevalence of mental health care did not change appreciably over time. However, mental health care increased among girls (from 22.8% in 2005-2006 to 25.4% in 2017-2018; aOR, 1.11; 95% CI, 1.04-1.19; P = .001), non-Hispanic white adolescents (from 20.4% in 2005-2006 to 22.7% in 2017-2018; aOR, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.03-1.14; P = .004), and those with private insurance (from 19.4% in 2005-2006 to 21.2% in 2017-2018; aOR, 1.11; 95% CI, 1.04-1.18; P = .002). Internalizing problems, including suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms, accounted for an increasing proportion of care (from 48.3% in 2005-2006 to 57.8% in 2017-2018; aOR, 1.52; 95% CI, 1.39-1.66; P < .001), whereas externalizing problems (from 31.9% in 2005-2006 to 23.7% in 2017-2018; aOR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.62-0.73; P < .001) and relationship problems (from 30.4% in 2005-2006 to 26.9% in 2017-2018; aOR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.69-0.82; P < .001) accounted for decreasing proportions. During this period, use of outpatient mental health services increased from 58.1% in 2005-2006 to 67.3% in 2017-2018 (aOR, 1.47; 95% CI, 1.35-1.59; P < .001), although use of school counseling decreased from 49.1% in 2005-2006 to 45.4% in 2017-2018 (aOR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.79-0.93; P < .001). Outpatient mental health visits (eg, private mental health clinicians, from 7.2 in 2005-2006 to 9.0 in 2017-2018; incidence rate ratio, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.23-1.37; P < .001) and overnight stays in inpatient mental health settings (from 4.0 nights in 2005-2006 to 5.4 nights in 2017-2018; incidence rate ratio, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.02-1.37; P = .03) increased.

Conclusions and Relevance

This study’s findings suggest that the growing number of adolescents who receive care for internalizing mental health problems and the increasing share who receive care in specialty outpatient settings are placing new demands on specialty adolescent mental health treatment resources.

Introduction

Considerable evidence supports separating child and adolescent mental health problems into internalizing problems (anxiety, depressive, and somatic symptoms) and externalizing problems (impulsive, conduct, and substance use symptoms).1,2 The prevalence of some internalizing problems, including depression and suicide, have recently increased among US adolescents,3,4,5 whereas externalizing behaviors, including substance use, have declined.5,6,7,8 These contrasting trends are puzzling, especially in light of possible common causal factors9,10 and earlier declines in internalizing and externalizing problems.11 Moreover, some research suggests the presence of reciprocal relationships between internalizing and externalizing youth behaviors.12,13,14,15

Few studies to date have explored the implications of recent national trends in the prevalence of internalizing and externalizing problems for service delivery. Specifically, little is known about recent changes in the clinical distribution of adolescent mental health care provided by specialty mental health, general medical, and school services. A claims-based study (1995-2000)16 found a dramatic increase in the proportion of children diagnosed with anxiety and depressive disorders and a decrease in those diagnosed with oppositional and substance use disorders. A more recent study (1995-2010) of office-based practices17 revealed increased treatment of internalizing and externalizing problems. Whether similar recent trends have occurred across the full range of treatment settings is not currently known.

We herein examine trends in a wide range of mental health services using data from nationally representative samples of adolescents surveyed from 2005 to 2018. We characterize trends in care for internalizing, externalizing, relationship, and school-related problems and from outpatient mental health, inpatient mental health, general medical, and school counseling service settings. The findings have implications for understanding the association of changes in the prevalence of mental health problems with use of services and mental health care needs of US adolescents.

Methods

Sample

The National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) is a cross-sectional annual survey of the US population 12 years or older in all 50 states and the District of Columbia sponsored by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.3,18,19 Persons without a household address (eg, homeless persons not living in shelters), active-duty military, and institutional residents are excluded. Interviews are conducted using computer-assisted interviewing. After the study was described to participants, verbal informed consent was obtained from parents or guardians, and verbal assent was obtained from adolescent participants. The NSDUH data collection protocol was approved by the institutional review board at RTI International. The present study used publicly available, deidentified data and was deemed exempt from review by the institutional review board of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

For this survey study, a total of 230 070 adolescents aged 12 to 17 years were interviewed in the NSDUH from January 1, 2005, through December 31, 2018. The NSDUH adolescent samples response rates ranged from 87.1% in 200520 to 73.9% in 201821 (according to Response Rate 2 of the American Association for Public Opinion Research22). All adolescents answered questions about at least 1 type of service for mental health problems.

Assessments

Mental health care was defined as receiving treatment or counseling in 1 or more of the queried settings in the past 12 months. In some analyses, mental health care was distinguished by service setting. Survey questions asked about “treatment and counseling for problems with behaviors or emotions that were not caused by alcohol or drugs.” Participants were next asked about settings where they had received care. These included inpatient mental health services, defined as overnight or longer stays at “any type of hospital” or “a residential treatment center”; outpatient mental health services, defined as “a partial day hospital or day treatment program,” “a mental health clinic or center,” “a private therapist, psychologist, psychiatrist, social worker, or counselor,” or “an in-home therapist, counselor, or family preservation worker”; general medical setting, defined as treatment or counseling from “a pediatrician or other family doctor”; and school counseling, defined as treatment or counseling from a “school counselor, school psychologist, or one of your regular teachers.” The wording of the last response choice was changed to “a school social worker, a school psychologist, or a school counselor” beginning in 2009. In addition, participants were asked about the number of visits to outpatient mental health and general medical services and number of nights spent in inpatient settings.

Participants were also asked about placement in “foster care or in a therapeutic foster care home.” Furthermore, beginning in 2009, participants were asked about attending “a school for students with emotional or behavioral problems” or participating in “a school program that was just for students with emotional or behavioral problems” and about receiving treatment or counseling for emotional or behavioral problems while in “a juvenile detention center, prison, or jail.” Placement in foster care, therapeutic foster care, schools or school programs for students with emotional problems, and treatment in the justice system were not included in analyses for trends in mental health care because these services were not assessed consistently over time.

After questions about each setting, participants were asked about the reason for receiving care during their last visit at each setting. Reasons were classified into internalizing problems (“thought about killing yourself or tried to kill yourself,” “felt depressed,” “felt very afraid and tense,” or “had eating problems”), externalizing problems (“breaking rules and ‘acting out’,” “trouble controlling your anger,” or “gotten into physical fights”), relationship problems (“problems at home or in your family,” “problems with your friends,” or “problems with people other than your friends or family”), school problems (“problems at school”), and other reasons.19,23 Questions about special schools or school programs and receiving treatment in the criminal justice settings were not followed by further questions about the nature of the mental health problem.

Information was also collected concerning participant age, sex, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, or non-Hispanic other), annual family income (categorized according to the federal poverty level), health insurance (private, Medicaid/Children’s Health Insurance Program [CHIP], other, or none), and metropolitan status of county of residence (large metropolitan, small metropolitan, or nonmetropolitan). Questions about income and health insurance were asked from adult household informants.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed from July 20 to December 1, 2019. Analyses were conducted in 3 stages. First, trends in 12-month mental health care overall and in specific sociodemographic groups were assessed across survey years using logistic regression models adjusted for sex, race/ethnicity, age, family income, health insurance, and metropolitan status of county of residence.

Second, trends in care for different types of mental health problems and service setting were examined. Similar adjusted logistic regression models were fit. Models for service setting were also adjusted for type of mental health problem. Stratified trend analyses were performed for type of mental health problem in each service setting. All trend analyses in this stage were limited to adolescents who had sought care in the past year.

Third, trends in the number of visits for mental health problems in various outpatient services and nights in inpatient services were examined using negative binomial regression models. These analyses were also limited to adolescents who had sought care in the past year.

To assess changes in care using regression models, the survey year variable was transformed to range from 0 to 1 so that odds ratios (ORs) from logistic regressions and incidence rate ratios (IRRs) from negative binomial regressions represent change in ORs or IRRs, respectively, during the 2005-2018 survey period. To test for deviations from linearity across survey years, the squared term of survey year was also entered into the logistic regression models and tested. Data from each period of 2 consecutive years were combined to produce more stable estimates.

All analyses were conducted using Stata, version 15 (StataCorp LLC), which takes into account the complex survey design and sampling weights of the NSDUH. All percentages reported are weighted. Two-sided P < .05 indicated significance.

Results

Overall Trend in Care

A total of 47 090 (19.7%) of the 230 070 adolescents across the survey years reported receiving mental health care during the past year. Of these, 27 132 (57.5%) were female and 19 958 (42.5%) were male; 14 773 (31.3%), aged 12 to 13 years; 16 647 (35.8%), aged 14 to 15 years; and 15 670 (32.9%), aged 16 to 17 years. The proportion who reported receiving care was stable over time (20.3% in 2005-2006 and 20.8% in 2017-2018; adjusted OR [aOR], 1.01; 95% CI, 0.96-1.06; P = .60). This proportion corresponds to a mean of approximately 4 868 000 adolescents having received mental health care each year from 2005 to 2018.

The squared term for survey year in the regression model for mental health care on the variable of the survey year was statistically significant (design-based F = 26.11; P < .001), revealing a nonlinear trend. Prevalence of care initially decreased to 18.7% (2009-2010) before rising in later years.

Trends in Care Within Sociodemographic Groups

Temporal trends in care varied across sociodemographic groups (Table 1). Mental health care increased among girls (from 22.8% in 2005-2006 to 25.4% in 2017-2018; aOR, 1.11; 95% CI, 1.04-1.19; P = .001) and decreased among boys (from 17.8% in 2005-2006 to 16.4% in 2017-2018; aOR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.84-0.96; P = .002). Moreover, although care slightly but significantly increased in non-Hispanic white adolescents (from 20.4% in 2005-2006 to 22.7% in 2017-2018; aOR, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.03-1.14; P = .004), it decreased in non-Hispanic black adolescents (from 22.6% in 2005-2006 to 18.5% in 2017-2018; aOR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.67-0.85; P < .001).

Table 1. Trends in Mental Health Care Among 230 070 Adolescent Participants of the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2005-2018, by Sociodemographic Characteristics.

| Characteristic | No. of participants | Mental health care, weighted % of participants | Change in odds of receiving carea | Test of departure from linearityb | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005-2006 | 2007-2008 | 2009-2010 | 2011-2012 | 2013-2014 | 2015-2016 | 2017-2018 | aOR (95% CI) | P value | F test | P value | ||

| Overall | 230 070 | 20.3 | 19.7 | 18.7 | 18.9 | 19.9 | 19.7 | 20.8 | 1.01 (0.96-1.06) | .60 | 26.11 | <.001 |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Female | 112 848 | 22.8 | 22.8 | 21.8 | 22.1 | 23.5 | 23.5 | 25.4 | 1.11 (1.04-1.19) | .001 | 16.06 | <.001 |

| Male | 117 222 | 17.8 | 16.8 | 15.8 | 15.8 | 16.4 | 16.0 | 16.4 | 0.90 (0.84-0.96) | .002 | 8.83 | .004 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 131 882 | 20.4 | 20.4 | 19.3 | 19.6 | 21.2 | 21.3 | 22.7 | 1.08 (1.03-1.14) | .004 | 21.43 | <.001 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 31 139 | 22.6 | 20.8 | 19.9 | 19.4 | 20.0 | 17.9 | 18.5 | 0.76 (0.67-0.85) | <.001 | 1.35 | .25 |

| Hispanic | 43 927 | 18.8 | 17.6 | 16.9 | 17.3 | 17.7 | 18.0 | 19.4 | 1.02 (0.91-1.13) | .75 | 6.64 | .01 |

| Other | 23 122 | 17.6 | 17.2 | 16.7 | 17.4 | 17.7 | 17.6 | 17.6 | 1.03 (0.88-1.20) | .74 | 0.07 | .80 |

| Age, y | ||||||||||||

| 12-13 | 72 913 | 19.6 | 19.9 | 18.5 | 19.3 | 20.2 | 18.6 | 20.1 | 1.00 (0.92-1.08) | .96 | 1.19 | .28 |

| 14-15 | 77 939 | 21.6 | 20.5 | 19.9 | 19.9 | 20.9 | 20.7 | 21.3 | 0.97 (0.90-1.04) | .41 | 6.95 | .01 |

| 16-17 | 79 218 | 19.5 | 18.7 | 17.8 | 17.4 | 18.6 | 19.6 | 20.9 | 1.07 (1.00-1.15) | .06 | 30.31 | <.001 |

| Family income compared with federal poverty level, % | ||||||||||||

| ≤100 | 46 394 | 22.0 | 22.3 | 20.0 | 21.1 | 20.7 | 20.6 | 19.9 | 0.88 (0.80-0.98) | .02 | 0.10 | .76 |

| >100 to 200 | 51 754 | 20.8 | 20.0 | 19.1 | 18.5 | 20.5 | 19.2 | 19.2 | 0.90 (0.81-1.00) | .051 | 1.58 | .21 |

| >200 | 131 922 | 19.5 | 18.8 | 18.1 | 18.2 | 19.3 | 19.5 | 21.7 | 1.11 (1.04-1.18) | .001 | 37.03 | <.001 |

| County of residence | ||||||||||||

| Large metropolitan | 102 410 | 20.6 | 19.3 | 19.0 | 18.8 | 20.2 | 20.0 | 20.8 | 1.04 (0.97-1.11) | .31 | 11.75 | .001 |

| Small metropolitan | 78 279 | 20.0 | 20.6 | 18.8 | 19.1 | 20.3 | 19.6 | 21.3 | 1.01 (0.94-1.09) | .75 | 6.92 | .01 |

| Nonmetropolitan | 49 381 | 19.5 | 19.3 | 17.8 | 18.6 | 18.1 | 18.6 | 20.1 | 0.93 (0.83-1.03) | .15 | 5.73 | .02 |

| Health insurance | ||||||||||||

| Private | 139 864 | 19.4 | 18.6 | 17.7 | 18.1 | 19.3 | 19.0 | 21.2 | 1.11 (1.04-1.18) | .002 | 31.58 | <.001 |

| Medicaid/CHIP | 66 577 | 24.3 | 24.0 | 22.2 | 21.3 | 21.9 | 21.4 | 21.6 | 0.87 (0.81-0.94) | .001 | 4.90 | .03 |

| Other | 7936 | 21.0 | 19.3 | 19.5 | 17.9 | 21.5 | 18.3 | 17.8 | 0.88 (0.69-1.12) | .30 | 0.01 | .90 |

| No health insurance | 12 928 | 15.8 | 16.4 | 14.7 | 16.0 | 15.9 | 16.2 | 12.7 | 0.92 (0.75-1.14) | .45 | 1.29 | .26 |

Abbreviations: aOR, adjusted odds ratio computed in logistic regression; CHIP, Children’s Health Insurance Program.

Based on binary logistic regressions of each dummy-coded variable on the variable of survey year. The variable of survey year was scaled to range from 0 (representing 2005-2006) to 1 (representing 2017-2018). Thus, regression coefficients represent change from the 2005-2006 to 2017-2018 period. The logistic regression models were adjusted for sex, age, race/ethnicity, family income compared with the federal poverty level, health insurance, and metropolitan status of county of residence.

Indicates adjusted Wald F test, with 1 and 110 df associated with the squared survey year variable.

Temporal increases were also noted among adolescents from families with income of more than 200% of the federal poverty level (from 19.5% in 2005-2006 to 21.7% in 2017-2018; aOR, 1.11; 95% CI, 1.04-1.18; P = .001) and among those with private insurance (from 19.4% in 2005-2006 to 21.2% in 2017-2018; aOR, 1.11; 95% CI, 1.04-1.18; P = .002). Care decreased among adolescents with Medicaid/CHIP (from 24.3% in 2005-2006 to 21.6% in 2017-2018; aOR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.81-0.94; P = .001) (Table 1).

Some trends were nonlinear. The increases in care noted above were limited to or more pronounced in the time after 2011-2012 among adolescent girls, non-Hispanic white adolescents, adolescents with family income of more than 200% of the federal poverty level, and those with private insurance. Furthermore, the decreases noted above among adolescent boys and Medicaid/CHIP beneficiaries were limited to the 2005-2006 to 2009-2010 period (Table 1). Similar to the overall trend, care somewhat declined after 2005 before increasing again in later years among Hispanic adolescents (16.9% in 2009-2010 to 19.4% in 2017-2018), those aged 14 to 15 (19.9% in 2009-2010 to 21.3% in 2017-2018) and 16 to 17 (17.4% in 2011-2012 to 20.9% in 2017-2018) years, adolescents living in large (18.8% in 2011-2012 to 20.8% in 2017-2018) and small (18.8% in 2009-2010 to 21.3% in 2017-2018) metropolitan areas, and those living in nonmetropolitan areas (17.8% in 2009-2010 to 20.1% in 2017-2018) (Table 1).

Types of Mental Health Problems and Trends in Care

Of those who received care, 51.8% received care for internalizing problems, 29.7% for externalizing problems, 29.7% for relationship problems, and 18.4% for school-related problems. These percentages sum to greater than 100% because some respondents received care for problems in more than 1 domain.

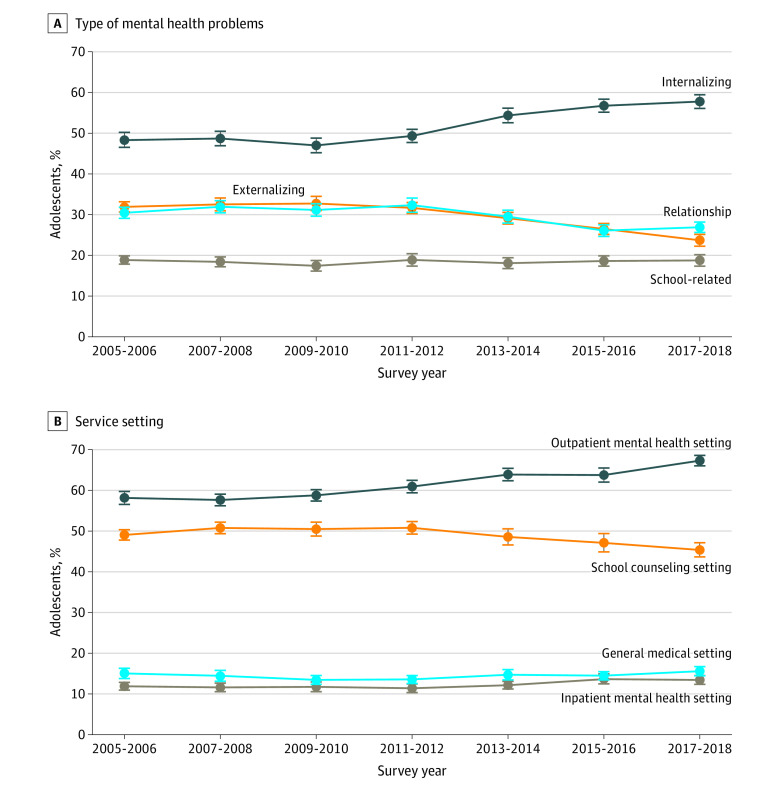

The proportion who received care for internalizing problems increased from 48.3% in 2005-2006 to 57.8% in 2017-2018 (aOR, 1.52; 95% CI, 1.39-1.66; P < .001) (Table 2 and Figure, A). The proportionate increase was especially marked for suicidal thoughts or suicide attempts (from 15.0% in 2005-2006 to 24.5% in 2017-2018; aOR, 2.11; 95% CI, 1.89-2.35; P < .001).

Table 2. Trends in Mental Health Care Among 47 090 Adolescent Participants of the National Survey on Drug Use and Health Who Received Mental Health Care in the Past Year by Type of Mental Health Problem and Service Setting.

| Variable | No. of participants | Survey year, weighted % of participants receiving mental health care in the past year | Change in odds of receiving carea | Test of departure from linearityb | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005-2006 | 2007-2008 | 2009-2010 | 2011-2012 | 2013-2014 | 2015-2016 | 2017-2018 | aOR (95% CI) | P value | F test | P value | ||

| Types of Mental Health Problems | ||||||||||||

| Internalizing problems | ||||||||||||

| Feeling depressed | 20 358 | 39.5 | 39.4 | 37.6 | 40.2 | 43.9 | 47.2 | 47.7 | 1.46 (1.34-1.59) | <.001 | 13.49 | <.001 |

| Suicidal ideation or attempt | 8619 | 15.0 | 13.5 | 14.7 | 16.1 | 19.5 | 22.9 | 24.5 | 2.11 (1.89-2.35) | <.001 | 15.36 | <.001 |

| Feeling afraid and tense | 8658 | 14.8 | 15.0 | 16.5 | 17.4 | 20.2 | 22.5 | 22.9 | 1.81 (1.64-2.01) | <.001 | 0.10 | .76 |

| Eating problems | 3964 | 7.4 | 7.6 | 6.6 | 7.2 | 8.9 | 10.3 | 8.7 | 1.34 (1.18-1.53) | <.001 | 0.50 | .48 |

| Any | 24 751 | 48.3 | 48.7 | 47.0 | 49.3 | 54.4 | 56.8 | 57.8 | 1.52 (1.39-1.66) | <.001 | 11.82 | .001 |

| Externalizing problems | ||||||||||||

| Breaking rules and acting out | 9694 | 22.9 | 22.2 | 22.1 | 21.6 | 19.0 | 17.6 | 15.7 | 0.64 (0.58-0.69) | <.001 | 7.06 | .009 |

| Trouble controlling anger | 6287 | 12.7 | 13.6 | 14.2 | 14.3 | 13.7 | 12.0 | 10.6 | 0.85 (0.76-0.95) | .004 | 18.35 | <.001 |

| Getting into physical fights | 2097 | 5.3 | 5.1 | 4.6 | 4.2 | 3.3 | 3.1 | 2.9 | 0.51 (0.43-0.62) | <.001 | 0.04 | .84 |

| Any | 14 345 | 31.9 | 32.5 | 32.7 | 31.7 | 29.1 | 26.5 | 23.7 | 0.67 (0.62-0.73) | <.001 | 19.21 | <.001 |

| Relationship problems | ||||||||||||

| Problems at home or in family | 9993 | 21.0 | 21.7 | 21.2 | 22.1 | 21.0 | 18.3 | 18.7 | 0.79 (0.72-0.87) | <.001 | 8.96 | .003 |

| Problems with friends | 6562 | 13.6 | 14.6 | 14.4 | 14.3 | 13.0 | 11.4 | 12.5 | 0.80 (0.71-0.90) | <.001 | 3.76 | .06 |

| Problems with other people | 4147 | 8.7 | 9.9 | 8.5 | 9.5 | 8.4 | 8.2 | 7.7 | 0.82 (0.72-0.92) | .002 | 2.92 | .09 |

| Any | 14 289 | 30.4 | 31.9 | 31.1 | 32.3 | 29.5 | 26.1 | 26.9 | 0.75 (0.69-0.82) | <.001 | 13.65 | <.001 |

| Problems at school | 8655 | 18.9 | 18.4 | 17.4 | 18.9 | 18.1 | 18.6 | 18.8 | 1.01 (0.91-1.11) | .89 | 0.78 | .38 |

| Service Setting | ||||||||||||

| Outpatient mental health care | ||||||||||||

| Private mental health clinician | 24 765 | 48.7 | 48.9 | 50.8 | 52.1 | 54.8 | 55.1 | 58.9 | 1.49 (1.37-1.61) | <.001 | 1.29 | .26 |

| In-home counselor | 7604 | 14.2 | 14.9 | 14.6 | 17.0 | 16.9 | 17.2 | 18.1 | 1.31 (1.16-1.47) | <.001 | 0.11 | .74 |

| Mental health clinic | 6914 | 12.2 | 11.9 | 12.4 | 12.3 | 15.2 | 18.2 | 19.3 | 1.73 (1.55-1.92) | <.001 | 14.21 | <.001 |

| Day treatment | 4324 | 8.6 | 7.9 | 7.9 | 8.9 | 9.8 | 9.8 | 9.4 | 1.13 (0.98-1.29) | .10 | 0 | .95 |

| Any | 29 127 | 58.1 | 57.6 | 58.8 | 60.9 | 63.9 | 63.8 | 67.3 | 1.47 (1.35-1.59) | <.001 | 3.12 | .08 |

| Inpatient mental health care | ||||||||||||

| Hospital stay | 5165 | 10.2 | 10.2 | 9.8 | 9.7 | 10.9 | 12.4 | 12.2 | 1.19 (1.06-1.34) | .003 | 4.07 | .046 |

| Residential care | 2471 | 4.4 | 4.2 | 4.8 | 5.1 | 4.7 | 5.9 | 5.9 | 1.25 (1.06-1.47) | .007 | 0.84 | .36 |

| Any | 5921 | 11.9 | 11.6 | 11.7 | 11.4 | 12.1 | 13.6 | 13.4 | 1.11 (1.00-1.24) | .057 | 2.97 | .09 |

| School counseling | 22 736 | 49.1 | 50.8 | 50.5 | 50.8 | 48.6 | 47.1 | 45.4 | 0.86 (0.79-0.93) | <.001 | 9.08 | .003 |

| General medical clinician | 6776 | 15.0 | 14.5 | 13.4 | 13.6 | 14.7 | 14.5 | 15.6 | 0.97 (0.86-1.10) | .66 | 5.73 | .02 |

| Foster care | 1135 | 2.8 | 2.5 | 2.2 | 2.5 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 0.54 (0.41-0.71) | <.001 | 0.37 | .54 |

| Special school | 3552 | NAc | NAc | 10.5 | 11.0 | 10.9 | 12.4 | 11.5 | 1.28 (1.04-1.58) | .02 | 0.05 | .83 |

| Criminal justice setting | 349 | NAc | NAc | 1.4 | 1.3 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 0.20 (0.10-0.40) | <.001 | 1.89 | .17 |

Abbreviations: aOR, adjusted odds ratio computed in logistic regressions; NA, not applicable.

Based on binary logistic regression of each dummy-coded variable on the variable of survey year. The variable of survey year was scaled to range from 0 (representing 2005-2006) to 1 (representing 2017-2018). Thus, regression coefficients represent change from the 2005-2006 to 2017-2018 period. The logistic regression models were adjusted for sex, age, race/ethnicity, family income compared with the federal poverty level, health insurance, and metropolitan status of county of residence. Analyses for service setting additionally adjusted for type of mental health problems (internalizing, externalizing, relationship, and school-related).

Indicates adjusted Wald F test, with 1 and 110 df associated with the squared survey year variable.

This type of service was not queried in these years.

Figure. Adjusted Trends in Mental Health Care Among Adolescent Participants of the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2005-2018.

The trend in care for internalizing problems was not uniform and deviated from a linear trend with relatively stable rates before 2011-2012, followed by a rapid increase (47.0% in 2009-2010 to 57.8% in 2017-2018) (Table 2). In contrast, the proportion who received care for externalizing problems declined (from 31.9% in 2005-2006 to 23.7% in 2017-2018; aOR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.62-0.73; P < .001), as did the proportion receiving care for relationship problems (from 30.4% in 2005-2006 to 26.9% in 2017-2018; aOR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.69-0.82; P < .001). The trend in care for externalizing problems was not uniform over the years and was limited to years after 2011-2012. The proportion receiving care for school-related problems did not appreciably change (Table 2).

Service Settings and Trends in Care

The most commonly used service settings were outpatient mental health services (61.5%), followed by school counseling (48.8%), general medical services (14.5%), and inpatient mental health services (12.3%). Most adolescents (69.7%) used only 1 service setting; 30.3% used more than 1. Adolescents who received mental health care in a general medical setting were most likely to receive care in other settings as well (65.1%), whereas those who received care in school counseling were least likely (45.4%).

The care settings changed over time (Table 2 and Figure, B). The proportion of adolescents cared for in outpatient mental health settings increased from 58.1% in 2005-2006 to 67.3% in 2017-2018 (aOR, 1.47; 95% CI, 1.35-1.59; P < .001). There was a marked increase in use of mental health clinics after 2011-2012 (12.3% to 19.3% in 2017-2018) (Table 2). Hospital stays (10.2% in 2005-2006 to 12.2% in 2017-2018; aOR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.06-1.34; P = .003) and residential treatment stays (4.4% in 2005-2006 to 5.9% in 2017-2018; aOR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.06-1.47; P = .007) also increased significantly over time (Table 2). However, the overall increase in inpatient mental health care was not significant (P = .06) because of increasing overlap between these settings (from 2.7% in 2005-2006 to 4.7% in 2017-2018). In contrast, care by school counselors decreased (from 49.1% in 2005-2006 to 45.4% in 2017-2018; aOR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.79-0.93; P < .001).

Only a small percentage of adolescents reported receiving mental health care in foster care or therapeutic foster care (2.8% in 2005-2006 to 1.8% in 2017-2018) or in criminal justice settings (1.4% in 2009-2010 to 0.4% in 2017-2018). The proportion of adolescents receiving care in these settings declined over time, whereas the proportion placed in special educational programs or special schools increased (10.5% in 2009-2010 to 11.5% in 2017-2018) (Table 2).

Analyses stratified by service setting revealed similar temporal trends across settings in care for internalizing, externalizing, relationship, and school-related problems (Table 3). Internalizing problems increased in adolescents receiving care in outpatient mental health settings (from 62.9% in 2005-2006 to 74.2% in 2017-2018; aOR, 1.76; 95% CI, 1.58-1.97; P < .001), inpatient mental health settings (from 75.5% in 2005-2006 to 86.1% in 2017-2018; aOR, 2.24; 95% CI, 1.66-3.03, P < .001), school counseling settings (from 50.1% in 2005-2006 to 62.3% in 2017-2018; aOR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.48-1.84; P < .001), and general medical settings (from 66.6% in 2005-2006 to 78.9% in 2017-2018; aOR, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.38-2.52; P < .001). Externalizing problems decreased in outpatient mental health settings (from 37.7% in 2005-2006 to 27.9% in 2017-2018; aOR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.55-0.70; P < .001), inpatient mental health settings (from 35.3% in 2005-2006 to 26.8% in 2017-2018; aOR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.49-0.81; P < .001), school counseling settings (from 36.3% in 2005-2006 to 24.4% in 2017-2018; aOR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.52-0.68; P < .001), and general medical settings (from 26.1% in 2005-2006 to 18.8% in 2017-2018; aOR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.52-0.89; P = .005). Similarly, relationship problems decreased in outpatient mental health settings (from 35.8% in 2005-2006 to 31.3% in 2017-2018; aOR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.67-0.83; P < .001), school counseling settings (from 34.6% in 2005-2006 to 28.3% in 2017-2018; aOR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.58-0.74; P < .001), and general medical settings (from 14.1% in 2005-2006 to 13.6% in 2017-2018; aOR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.45-0.89; P = .008). School-related problems did not change in outpatient or inpatient mental health settings or in school counseling settings. However, these problems decreased in general medical settings (from 18.7% in 2005-2006 to 13.4% in 2017-2018; aOR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.50-0.98; P = .04).

Table 3. Trends in Mental Health Care Among 47 090 Adolescent Participants of the National Survey on Drug Use and Health Who Received Mental Health Care in the Past Year by Service Setting and Type of Mental Health Problem.

| Service setting by mental health problem | No. of participants | Survey year, weighted % of participants who received mental health care in the past year | Change in odds of receiving care for different mental health problemsa | Test of departure from linearityb | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005-2006 | 2007-2008 | 2009-2010 | 2011-2012 | 2013-2014 | 2015-2016 | 2017-2018 | aOR (95% CI) | P value | F test | P value | ||

| Outpatient mental health services | ||||||||||||

| Internalizing problems | 17 050 | 62.9 | 62.4 | 60.9 | 62.1 | 68.2 | 72.4 | 74.2 | 1.76 (1.58-1.97) | <.001 | 21.48 | <.001 |

| Externalizing problems | 9116 | 37.7 | 39.2 | 39.8 | 38.7 | 33.1 | 31.5 | 27.9 | 0.62 (0.55-0.70) | <.001 | 14.82 | <.001 |

| Relationship problems | 8909 | 35.8 | 36.6 | 37.5 | 38.7 | 34.7 | 31.1 | 31.3 | 0.74 (0.67-0.83) | <.001 | 14.22 | <.001 |

| School-related problems | 4748 | 18.2 | 18.1 | 19.0 | 19.9 | 18.0 | 19.3 | 19.3 | 1.08 (0.96-1.22) | .22 | 0.17 | .68 |

| Inpatient mental health services | ||||||||||||

| Internalizing problems | 3315 | 75.5 | 76.6 | 76.5 | 79.7 | 83.0 | 87.0 | 86.1 | 2.24 (1.66-3.03) | <.001 | 0.78 | .38 |

| Externalizing problems | 1287 | 35.3 | 30.2 | 32.5 | 35.3 | 24.2 | 25.7 | 26.8 | 0.63 (0.49-0.81) | <.001 | 0.01 | .93 |

| Relationship problems | 570 | 15.8 | 12.9 | 11.5 | 14.0 | 12.0 | 12.5 | 13.7 | 0.82 (0.55-1.23) | .33 | 0.99 | .32 |

| School-related problems | 497 | 14.1 | 11.7 | 11.9 | 13.4 | 9.1 | 12.0 | 14.3 | 0.94 (0.60-1.48) | .80 | 1.35 | .25 |

| School counseling | ||||||||||||

| Internalizing problems | 10 727 | 50.1 | 51.4 | 49.7 | 51.3 | 57.8 | 59.6 | 62.3 | 1.65 (1.48-1.84) | <.001 | 7.50 | .007 |

| Externalizing problems | 6279 | 36.3 | 34.0 | 36.1 | 32.0 | 30.5 | 27.3 | 24.4 | 0.59 (0.52-0.68) | <.001 | 4.34 | .04 |

| Relationship problems | 6726 | 34.6 | 36.1 | 38.1 | 37.3 | 31.4 | 27.9 | 28.3 | 0.66 (0.58-0.74) | <.001 | 18.72 | <.001 |

| School-related problems | 4415 | 23.8 | 22.8 | 21.0 | 23.4 | 22.8 | 22.7 | 23.7 | 1.02 (0.87-1.19) | .80 | 1.17 | .28 |

| General medical services | ||||||||||||

| Internalizing problems | 3602 | 66.6 | 64.5 | 68.4 | 75.2 | 74.2 | 78.5 | 78.9 | 1.87 (1.38-2.52) | <.001 | 0.05 | .82 |

| Externalizing problems | 1249 | 26.1 | 31.1 | 29.3 | 24.2 | 25.4 | 23.4 | 18.8 | 0.68 (0.52-0.89) | .005 | 2.27 | .14 |

| Relationship problems | 710 | 14.1 | 20.4 | 18.7 | 12.3 | 12.1 | 11.5 | 13.6 | 0.63 (0.45-0.89) | .008 | 0.03 | .85 |

| School-related problems | 641 | 18.7 | 15.3 | 15.2 | 12.3 | 11.4 | 13.1 | 13.4 | 0.70 (0.50-0.98) | .04 | 2.15 | .15 |

Abbreviation: aOR, adjusted odds ratio computed in logistic regressions.

Based on binary logistic regression of each dummy-coded variable on the variable of survey year. The variable of survey year was scaled to range from 0 (representing 2005-2006) to 1 (representing 2017-2018). Thus, regression coefficients represent change from the 2005-2006 to 2017-2018 period. The logistic regression models were adjusted for sex, age, race/ethnicity, family income compared with federal poverty level, health insurance, and metropolitan status of county of residence.

Indicates adjusted Wald F test, with 1 and 110 df associated with the squared survey year variable.

Trends in Number of Visits and Overnight Stays

The mean number of visits to private mental health clinicians increased (from 7.2 in 2005-2006 to 9.0 in 2017-2018; adjusted IRR [aIRR], 1.30; 95% CI, 1.23-1.37; P < .001), as did the number of in-home counseling visits (from 6.0 in 2005-2006 to 7.7 in 2017-2018; aIRR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.17-1.44; P < .001), mental health clinic visits (from 6.9 in 2005-2006 to 8.4 in 2017-2018; aIRR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.09-1.39; P = .001), day treatment visits (from 5.5 in 2005-2006 to 7.2 in 2017-2018; aIRR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.07-1.47; P = .006), and general medical visits (from 3.2 in 2005-2006 to 3.7 in 2017-2018; aIRR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.11-1.47; P = .001). The number of overnight hospital stays also increased over time (from 4.0 nights in 2005-2006 to 5.4 nights in 2017-2018; aIRR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.02-1.37; P = .03) (Table 4).

Table 4. Trends in Number of Mental Health Visits or Overnight Stays Among 47 090 Adolescent Participants of the National Survey on Drug Use and Health Who Received Mental Health Care in the Past Year, According to Setting.

| No. of visits or overnight stays | No. of adolescents | Survey year, % of participants who received mental health carea | Change in incidence of nights or visits during the 2005-2018 periodb | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005-2006 | 2007-2008 | 2009-2010 | 2011-2012 | 2013-2014 | 2015-2016 | 2017-2018 | aIRR (95% CI) | P value | ||

| Private mental health clinician visits, No. | ||||||||||

| 1 | 4096 | 22.9 | 24.0 | 22.4 | 20.2 | 18.7 | 17.5 | 17.4 | 1.30 (1.23-1.37) | <.001 |

| 2 | 2852 | 15.7 | 15.9 | 14.2 | 14.2 | 13.6 | 11.9 | 12.3 | ||

| 3-6 | 6187 | 28.9 | 30.2 | 30.0 | 30.4 | 30.3 | 31.2 | 30.4 | ||

| 7-24 | 5221 | 22.6 | 22.1 | 24.7 | 24.4 | 27.2 | 26.2 | 27.8 | ||

| ≥25 | 2310 | 9.9 | 7.9 | 8.7 | 10.8 | 10.2 | 13.3 | 12.2 | ||

| Mean No. of visitsa | 20 666 | 7.2 | 7.0 | 7.5 | 8.1 | 8.3 | 9.2 | 9.0 | ||

| In-home counseling visits, No. | ||||||||||

| 1 | 1627 | 30.8 | 30.0 | 32.8 | 25.5 | 25.9 | 25.8 | 22.5 | 1.30 (1.17-1.44) | <.001 |

| 2 | 1021 | 15.8 | 16.9 | 14.1 | 17.8 | 15.8 | 14.3 | 17.3 | ||

| 3-6 | 1646 | 29.2 | 27.6 | 25.6 | 27.1 | 27.5 | 25.7 | 26.5 | ||

| 7-24 | 1353 | 17.5 | 19.0 | 19.6 | 22.4 | 23.6 | 23.0 | 24.0 | ||

| ≥25 | 563 | 6.7 | 6.5 | 7.9 | 7.2 | 7.3 | 11.3 | 9.7 | ||

| Mean No. of visitsa | 6210 | 6.0 | 6.2 | 6.6 | 6.8 | 6.9 | 8.1 | 7.7 | ||

| Mental health clinic visits, No. | ||||||||||

| 1 | 1505 | 31.3 | 28.9 | 28.0 | 35.0 | 29.1 | 20.0 | 21.8 | 1.23 (1.09-1.39) | .001 |

| 2 | 800 | 9.1 | 15.4 | 13.5 | 13.1 | 14.5 | 13.1 | 13.6 | ||

| 3-6 | 1473 | 25.8 | 23.8 | 27.0 | 23.2 | 23.1 | 25.9 | 26.8 | ||

| 7-24 | 1438 | 24.7 | 25.8 | 22.3 | 19.6 | 23.8 | 28.1 | 27.6 | ||

| ≥25 | 574 | 9.1 | 6.1 | 9.2 | 9.1 | 9.5 | 13.0 | 10.2 | ||

| Mean No. of visitsa | 5790 | 6.9 | 6.8 | 7.1 | 6.8 | 7.4 | 9.1 | 8.4 | ||

| Day treatment visits, No. | ||||||||||

| 1 | 1216 | 37.3 | 34.7 | 38.8 | 36.8 | 30.1 | 29.6 | 31.2 | 1.25 (1.07-1.47) | .006 |

| 2 | 567 | 29.6 | 38.4 | 29.0 | 28.0 | 41.3 | 31.4 | 28.0 | ||

| 3-6 | 780 | 19.1 | 19.5 | 16.7 | 22.6 | 17.0 | 25.0 | 25.1 | ||

| 7-24 | 737 | 23.7 | 18.5 | 23.0 | 19.9 | 23.1 | 21.8 | 23.0 | ||

| ≥25 | 289 | 4.3 | 5.8 | 5.7 | 6.5 | 8.7 | 10.1 | 8.5 | ||

| Mean No. of visitsa | 3589 | 5.5 | 5.7 | 5.8 | 6.0 | 6.8 | 7.6 | 7.2 | ||

| Hospital mental health stays, No. of nights | ||||||||||

| 1 | 1953 | 60.0 | 53.9 | 44.4 | 48.0 | 40.1 | 39.8 | 42.0 | 1.18 (1.02-1.37) | .03 |

| 2 | 484 | 10.2 | 8.3 | 11.0 | 10.6 | 12.8 | 10.0 | 12.3 | ||

| 3-6 | 821 | 15.9 | 14.4 | 24.5 | 16.0 | 22.9 | 21.3 | 20.1 | ||

| 7-24 | 848 | 11.0 | 17.2 | 15.0 | 20.2 | 20.3 | 22.9 | 20.3 | ||

| ≥25 | 251 | 2.9 | 6.1 | 5.1 | 5.1 | 4.0 | 6.0 | 5.3 | ||

| Mean No. of visitsa | 4357 | 4.0 | 5.1 | 5.0 | 5.3 | 5.1 | 5.7 | 5.4 | ||

| Residential mental health stays, No. of nights | ||||||||||

| 1 | 631 | 35.3 | 36.0 | 37.2 | 30.7 | 26.6 | 27.7 | 29.3 | 0.94 (0.74-1.18) | .58 |

| 2 | 243 | 16.0 | 9.9 | 10.8 | 12.6 | 13.6 | 10.8 | 12.7 | ||

| 3-6 | 382 | 15.5 | 12.5 | 17.0 | 16.6 | 25.4 | 20.9 | 22.8 | ||

| 7-24 | 551 | 23.1 | 22.4 | 17.9 | 26.5 | 26.6 | 31.7 | 25.5 | ||

| ≥25 | 317 | 10.1 | 19.2 | 17.2 | 13.7 | 7.9 | 8.9 | 9.6 | ||

| Mean No. of visitsa | 2124 | 7.0 | 9.3 | 8.6 | 8.6 | 7.0 | 7.6 | 7.6 | ||

| General medical clinician visits, No. | ||||||||||

| 1 | 2620 | 44.2 | 41.4 | 47.3 | 41.7 | 41.4 | 36.2 | 35.2 | 1.27 (1.11-1.47) | .001 |

| 2 | 1513 | 24.2 | 26.9 | 23.1 | 22.8 | 25.6 | 23.4 | 27.7 | ||

| 3-6 | 1407 | 21.7 | 23.8 | 20.0 | 24.5 | 23.2 | 25.6 | 25.0 | ||

| 7-24 | 536 | 8.6 | 6.6 | 8.4 | 8.8 | 7.6 | 9.3 | 10.2 | ||

| ≥25 | 141 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 5.6 | 1.9 | ||

| Mean No. of visitsa | 6217 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.6 | 3.4 | 4.7 | 3.7 | ||

Abbreviation: aIRR, adjusted incidence rate ratio.

Values are weighted.

Based on negative binomial regressions adjusting for sex, age, race/ethnicity, family income compared with federal poverty level, health insurance, metropolitan status of county of residence, and type of mental health problems (internalizing, externalizing, relationship, and school-related). The variable of survey year was scaled to range from 0 (representing 2005-2006) to 1 (representing 2017-2018). Thus, regression coefficients represent aIRRs of visits or overnight stays from the 2005-2006 to 2017-2018 period.

Discussion

Each year, nearly 1 in 5 adolescents receives care for mental health problems. This proportion has remained nearly constant from 2005 to 2018. However, changes occurred in the sociodemographic profile of adolescents who received care, the reasons for which they received care, the service settings, and the number of contacts.

Care increased modestly among girls, non-Hispanic white adolescents, those from higher-income families, and adolescents covered by private insurance. By contrast, mental health care declined among boys, non-Hispanic black adolescents, and those covered by Medicaid/CHIP. Furthermore, care for internalizing problems increased, whereas care for externalizing and relationship problems decreased.

Changes also occurred in service settings. Although the share of care from outpatient and inpatient specialty mental health services increased, the share from school services modestly decreased. Across settings, similar trends occurred in the types of treated problems.

These trends parallel recent trends in adolescent mental health problems in the US and in some other industrialized countries.3,4,5,6,7,8,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32 Substantial evidence exists for increasing trends in depressive and anxiety symptoms and suicidal behavior3,4,5 alongside declining externalizing behaviors among US adolescents.5,6,7,8 Moreover, changes in the demographic characteristics of adolescents who received mental health care paralleled sex and racial/ethnic trends in major depressive episodes in adolescents3,4 and a greater increase in national suicide rates among adolescent girls than boys.33

The causes of the recent trends in adolescent psychopathology are not known. A possible role of social media use and texting in the recent increase in adolescent depression is debated.4,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42 Declining child victimization,43 increased use of psychiatric medication prescribed to children and adolescents,44,45 and a decrease in childhood lead exposure46,47,48 may have contributed to the decline in prevalence of externalizing behaviors. Although the causes have yet to be elucidated, implications for services deserve attention.

The observed trends in adolescent mental health care raise questions about the extent to which these problems are matched to appropriate services. School counseling and general medical services may not be optimally equipped to manage more severe forms of internalizing problems that account for a large and increasing share of the adolescent mental health problems they encounter.49,50,51 Optimal management of more severe conditions often calls for coordination and collaboration across different health care professionals and settings.52 However, many adolescents with mental health problems detected in school or primary care services never complete referrals to mental health clinicians.53 In the present study, only a minority of adolescents seen by school counselors received care in other settings. Other research indicates that adolescents from racial/ethnic minorities, those with public insurance, and those from low-income households may be more likely to use services in school settings only.19

Access to adolescent mental health services may be further hindered by workforce shortages. Many schools face shortages in counselors.54 In several US cities, mean wait times for child psychiatrist appointments greatly exceed wait times for pediatricians.55 From 2005 to 2018, the share of adolescent mental health care provided in outpatient and inpatient mental health settings significantly increased, along with the increasing number of outpatient visits, which suggests an increasing demand for child and adolescent mental health specialists. These trends are in tension with recent projections from the Health Resources Services Administration of a national oversupply of child and adolescent psychiatrists by 2030.56 Although state and federal policies have improved financial access to needed mental health services for children and adolescents,57,58 workforce and referral barriers persist.55 Bridging these gaps calls for innovative interventions to improve referrals and integration across services.59,60

The present results are consistent with rising national rates of hospitalizations of adolescents with suicidal ideation and behaviors from 2008 to 2015.61 A study from Finland also reported an increase in depression, anxiety, and eating disorder diagnoses and a reduction in conduct and oppositional disorders from 2000 to 2011 on child and adolescent psychiatry wards.62 The present findings may appear at odds with a report of a higher prevalence of adolescent mental health visits to general medical clinicians than to psychiatrists in the 2007-2010 period.17 That previous report, however, was limited to office-based practices. Furthermore, a significant increase in adolescent depression occurred after 2010,3 as did most of the changes documented in this study.

Limitations

The study findings should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. First, the study was based on self-report that may not correspond with objective assessments or assessments by parents and teachers.63 Mental health care rates from the NSDUH are higher than treatment rates from claims data.64 However, claims data only capture inpatient and outpatient services that are reimbursed by insurance, whereas the NSDUH assessed a much broader range of services. Second, the NSDUH reports the number of visits or overnight stays in the past 12 months and therefore does not permit determining the number or length of care episodes. Third, this study examined only care patterns rather than the prevalence of mental health problems. The NSDUH assessed prevalence of major depressive episodes, and prior reports have examined correlates and temporal trends of this condition.3,4,65 Fourth, the NSDUH did not collect information on the nature, quality, or effectiveness of the mental health care. Fifth, although the NSDUH assessed treatment for substance disorders, a different set of questions were used for the care of substance use disorders than for the care of mental health problems. Sixth, wording of the question about school counseling was changed in 2009. Therefore, trends in this type of service should be interpreted with caution. However, it is notable that prevalence of school counseling was remarkably stable from the 2007-2008 to 2009-2010 periods. Finally, informal sources of help were not assessed.

Conclusions

In the context of these limitations, this study provides a broad view of temporal trends in mental health problems for which adolescents received care in the United States, the settings in which they received mental health care, and the volume of services they received. Trends in types of problems for which adolescents received care correspond with recent national trends of adolescent psychopathology and appear to highlight the growing importance of recognizing and managing internalizing problems across the major treatment settings.

References

- 1.Achenbach TM, Ivanova MY, Rescorla LA, Turner LV, Althoff RR. Internalizing/externalizing problems: review and recommendations for clinical and research applications. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;55(8):647-656. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zahn-Waxler C, Klimes-Dougan B, Slattery MJ. Internalizing problems of childhood and adolescence: prospects, pitfalls, and progress in understanding the development of anxiety and depression. Dev Psychopathol. 2000;12(3):443-466. doi: 10.1017/S0954579400003102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Han B. National trends in the prevalence and treatment of depression in adolescents and young adults. Pediatrics. 2016;138(6):e20161878. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Twenge JM, Cooper AB, Joiner TE, Duffy ME, Binau SG. Age, period, and cohort trends in mood disorder indicators and suicide-related outcomes in a nationally representative dataset, 2005-2017. J Abnorm Psychol. 2019;128(3):185-199. doi: 10.1037/abn0000410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kann L, McManus T, Harris WA, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance: United States, 2017. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2018;67(8):1-114. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6708a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grucza RA, Krueger RF, Agrawal A, et al. Declines in prevalence of adolescent substance use disorders and delinquent behaviors in the USA: a unitary trend? Psychol Med. 2018;48(9):1494-1503. doi: 10.1017/S0033291717002999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patrick ME, Terry-McElrath YM, Miech RA, Schulenberg JE, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD. Age-specific prevalence of binge and high-intensity drinking among US young adults: changes from 2005 to 2015. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2017;41(7):1319-1328. doi: 10.1111/acer.13413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Terry-McElrath YM, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD, Bray BC, Patrick ME, Schulenberg JE. Longitudinal patterns of marijuana use across ages 18-50 in a US national sample: a descriptive examination of predictors and health correlates of repeated measures latent class membership. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;171:70-83. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.11.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fergusson DM, Lynskey MT, Horwood LJ. Origins of comorbidity between conduct and affective disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35(4):451-460. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199604000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolff JC, Ollendick TH. The comorbidity of conduct problems and depression in childhood and adolescence. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2006;9(3-4):201-220. doi: 10.1007/s10567-006-0011-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Achenbach TM, Dumenci L, Rescorla LA. Are American children’s problems still getting worse? a 23-year comparison. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2003;31(1):1-11. doi: 10.1023/A:1021700430364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lilienfeld SO. Comorbidity between and within childhood externalizing and internalizing disorders: reflections and directions. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2003;31(3):285-291. doi: 10.1023/A:1023229529866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agrawal A, Tillman R, Grucza RA, et al. Reciprocal relationships between substance use and disorders and suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in the Collaborative Study of the Genetics of Alcoholism. J Affect Disord. 2017;213:96-104. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.12.060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee EJ, Bukowski WM. Co-development of internalizing and externalizing problem behaviors: causal direction and common vulnerability. J Adolesc. 2012;35(3):713-729. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boylan K, Vaillancourt T, Boyle M, Szatmari P. Comorbidity of internalizing disorders in children with oppositional defiant disorder. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;16(8):484-494. doi: 10.1007/s00787-007-0624-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harpaz-Rotem I, Rosenheck RA. Changes in outpatient psychiatric diagnosis in privately insured children and adolescents from 1995 to 2000. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2004;34(4):329-340. doi: 10.1023/B:CHUD.0000020683.08514.2d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olfson M, Blanco C, Wang S, Laje G, Correll CU. National trends in the mental health care of children, adolescents, and adults by office-based physicians. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(1):81-90. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.3074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health public use file codebook. Published October 23, 2018. Accessed August 24, 2019. https://samhda.s3-us-gov-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/field-uploads-protected/studies/NSDUH-2017/NSDUH-2017-datasets/NSDUH-2017-DS0001/NSDUH-2017-DS0001-info/NSDUH-2017-DS0001-info-codebook.pdf

- 19.Ali MM, West K, Teich JL, Lynch S, Mutter R, Dubenitz J. Utilization of mental health services in educational setting by adolescents in the United States. J Sch Health. 2019;89(5):393-401. doi: 10.1111/josh.12753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Results from the 2005 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings NSDUH Series H-30, DHHS Publication No. SMA 06-4194. Published September 2006. Accessed August 5, 2019. http://www.dpft.org/resources/NSDUHresults2005.pdf

- 21.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: methodological summary and definitions. Published August 2019. Accessed February 18, 2020. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/cbhsq-reports/NSDUHMethodsSummDefs2018/NSDUHMethodsSummDefs2018.htm

- 22.American Association for Public Opinion Research Standard definitions: final dispositions of case codes and outcome rates for surveys, 8th edition. Revised April 2015. Accessed February 18, 2020. https://www.aapor.org/AAPOR_Main/media/MainSiteFiles/Standard-Definitions2015_8thEd.pdf

- 23.Mitchell KS, Wolf EJ, Reardon AF, Miller MW. Association of eating disorder symptoms with internalizing and externalizing dimensions of psychopathology among men and women. Int J Eat Disord. 2014;47(8):860-869. doi: 10.1002/eat.22300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Collishaw S. Annual research review: secular trends in child and adolescent mental health. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2015;56(3):370-393. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Collishaw S, Maughan B, Goodman R, Pickles A. Time trends in adolescent mental health. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004;45(8):1350-1362. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00335.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fichter MM, Xepapadakos F, Quadflieg N, Georgopoulou E, Fthenakis WE. A comparative study of psychopathology in Greek adolescents in Germany and in Greece in 1980 and 1998–18 years apart. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;254(1):27-35. doi: 10.1007/s00406-004-0450-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fleming TM, Clark T, Denny S, et al. Stability and change in the mental health of New Zealand secondary school students 2007-2012: results from the National Adolescent Health Surveys. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2014;48(5):472-480. doi: 10.1177/0004867413514489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sigfusdottir ID, Asgeirsdottir BB, Sigurdsson JF, Gudjonsson GH. Trends in depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms and visits to healthcare specialists: a national study among Icelandic adolescents. Scand J Public Health. 2008;36(4):361-368. doi: 10.1177/1403494807088457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sweeting H, Young R, West P. GHQ increases among Scottish 15 year olds 1987-2006. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2009;44(7):579-586. doi: 10.1007/s00127-008-0462-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tick NT, van der Ende J, Verhulst FC. Twenty-year trends in emotional and behavioral problems in Dutch children in a changing society. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2007;116(6):473-482. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01068.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tick NT, van der Ende J, Verhulst FC. Ten-year trends in self-reported emotional and behavioral problems of Dutch adolescents. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2008;43(5):349-355. doi: 10.1007/s00127-008-0315-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.von Soest T, Wichstrøm L. Secular trends in depressive symptoms among Norwegian adolescents from 1992 to 2010. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2014;42(3):403-415. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9785-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Curtin SC, Warner M, Hedegaard H. Increase in Suicide in the United States, 1999–2014. National Center for Health Statistics; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bickham DS, Hswen Y, Rich M. Media use and depression: exposure, household rules, and symptoms among young adolescents in the USA. Int J Public Health. 2015;60(2):147-155. doi: 10.1007/s00038-014-0647-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hoge E, Bickham D, Cantor J. Digital media, anxiety, and depression in children. Pediatrics. 2017;140(suppl 2):S76-S80. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1758G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin LY, Sidani JE, Shensa A, et al. Association between social media use and depression among US young adults. Depress Anxiety. 2016;33(4):323-331. doi: 10.1002/da.22466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seo JH, Kim JH, Yang KI, Hong SB. Late use of electronic media and its association with sleep, depression, and suicidality among Korean adolescents. Sleep Med. 2017;29:76-80. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2016.06.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Woods HC, Scott H. #Sleepyteens: social media use in adolescence is associated with poor sleep quality, anxiety, depression and low self-esteem. J Adolesc. 2016;51:41-49. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Augner C, Hacker GW. Associations between problematic mobile phone use and psychological parameters in young adults. Int J Public Health. 2012;57(2):437-441. doi: 10.1007/s00038-011-0234-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lenhart A. Teen, Social Media and Technology Overview. Pew Research Center; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Przybylski AK, Weinstein N. A large-scale test of the Goldilocks hypothesis. Psychol Sci. 2017;28(2):204-215. doi: 10.1177/0956797616678438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Orben A, Przybylski AK. Screens, teens, and psychological well-being: evidence from three time-use-diary studies. Psychol Sci. 2019;30(5):682-696. doi: 10.1177/0956797619830329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Finkelhor D, Shattuck A, Turner HA, Hamby SL. Trends in children’s exposure to violence, 2003 to 2011. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(6):540-546. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.5296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Finkelhor D, Johnson M. Has psychiatric medication reduced crime and delinquency? Trauma Violence Abuse. 2017;18(3):339-347. doi: 10.1177/1524838015620817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marcotte DE, Markowitz S. A cure for crime? psycho-pharmaceuticals and crime trends. J Policy Anal Manage. 2010;30(1):29-56. doi: 10.1002/pam.20544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nevin R. Trends in preschool lead exposure, mental retardation, and scholastic achievement: association or causation? Environ Res. 2009;109(3):301-310. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2008.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nevin R. Understanding international crime trends: the legacy of preschool lead exposure. Environ Res. 2007;104(3):315-336. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2007.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nevin R. How lead exposure relates to temporal changes in IQ, violent crime, and unwed pregnancy. Environ Res. 2000;83(1):1-22. doi: 10.1006/enrs.1999.4045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carlson LA, Kees NL. Mental health services in public schools: a preliminary study of school counselor perceptions. Prof School Counsel. Published online February 15, 2018. doi: 10.1177/2156759X12016002S03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stein RE, Horwitz SM, Storfer-Isser A, Heneghan A, Olson L, Hoagwood KE. Do pediatricians think they are responsible for identification and management of child mental health problems? results of the AAP periodic survey. Ambul Pediatr. 2008;8(1):11-17. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2007.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Girio-Herrera E, Ehrlich CJ, Danzi BA, La Greca AM. Lessons learned about barriers to implementing school-based interventions for adolescents: ideas for enhancing future research and clinical projects. Cognit Behav Pract. 2019;26(3240):466-477. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2018.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aupont O, Doerfler L, Connor DF, Stille C, Tisminetzky M, McLaughlin TJ. A collaborative care model to improve access to pediatric mental health services. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2013;40(4):264-273. doi: 10.1007/s10488-012-0413-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Glied S, Cuellar AE. Trends and issues in child and adolescent mental health. Health Aff (Millwood). 2003;22(5):39-50. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.22.5.39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gagnon DJ, Mattingly MJ. Most US School Districts Have Low Access to School Counselors. University of New Hampshire Carsey School of Public Policy; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cama S, Malowney M, Smith AJB, et al. Availability of outpatient mental health care by pediatricians and child psychiatrists in five US cities. Int J Health Serv. 2017;47(4):621-635. doi: 10.1177/0020731417707492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Health Services Resources Administration Behavioral health workforce projections, 2016-2030: psychiatrists (adult), child and adolescent psychiatrists. Published 2018. Accessed February 18, 2020. https://bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bhw/nchwa/projections/psychiatrists-2018.pdf

- 57.Kapphahn C, Morreale M, Rickert VI, Walker L. Financing mental health services for adolescents: a background paper. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39(3):318-327. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Walter AW, Yuan Y, Cabral HJ. Mental health services utilization and expenditures among children enrolled in employer-sponsored health plans. Pediatrics. 2017;139(suppl 2):S127-S135. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2786G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Herman KC, Cho E, Marriott BR, Walker LY. Bridging the gap in psychiatric care for children with a school-based psychiatry program. School Ment Health. 2018;10(2):181-189. doi: 10.1007/s12310-017-9222-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Walter HJ, Kackloudis G, Trudell EK, et al. Enhancing pediatricians’ behavioral health competencies through child psychiatry consultation and education. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2018;57(8):958-969. doi: 10.1177/0009922817738330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Plemmons G, Hall M, Doupnik S, et al. Hospitalization for suicide ideation or attempt: 2008-2015. Pediatrics. 2018;141(6):e20172426. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-2426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kronström K, Ellilä H, Kuosmanen L, Kaljonen A, Sourander A. Changes in the clinical features of child and adolescent psychiatric inpatients: a nationwide time-trend study from Finland. Nord J Psychiatry. 2016;70(6):436-441. doi: 10.3109/08039488.2016.1149617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Olfson M, Druss BG, Marcus SC. Trends in mental health care among children and adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(21):2029-2038. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1413512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Larson MJ, Miller K, Fleming KJ, Teich JL. Mental health services for children in large, employer-based health plans, 1999. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2007;34(1):56-72. doi: 10.1007/s11414-006-9028-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Breslau J, Gilman SE, Stein BD, Ruder T, Gmelin T, Miller E. Sex differences in recent first-onset depression in an epidemiological sample of adolescents. Transl Psychiatry. 2017;7(5):e1139. doi: 10.1038/tp.2017.105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]