This cohort study examines whether a mental disorder diagnosis, the type of disorder, and other variables play a role in the decision to take the ninth-grade final examination and in the examination outcome among young people in Denmark.

Key Points

Question

What are the educational achievements at the final examination of compulsory schooling in Denmark among individuals with or without a mental disorder?

Findings

In this nationwide cohort study of 629 622 individuals, 52% of those with a mental disorder took the final examination compared with 88% of those without a mental disorder. Students with a mental disorder who took the examination attained considerably lower grades on the examination.

Meaning

The findings of this study suggest that a mental disorder in childhood or adolescence is associated with lower educational achievements and that additional educational support for these individuals may be needed.

Abstract

Importance

Onset of mental disorders during childhood or adolescence has been associated with underperformance in school and impairment in social and occupational life in adulthood, which has important implications for the affected individuals and society.

Objective

To compare the educational achievements at the final examination of compulsory schooling in Denmark between individuals with and those without a mental disorder.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This population-based cohort study was conducted in Denmark and obtained data from the Danish Civil Registration System and other nationwide registers. The 2 cohorts studied were (1) all children who were born in Denmark between January 1, 1988, and July 1, 1999, and were alive at age 17 years (n = 629 622) and (2) all children who took the final examination at the end of ninth grade in both Danish and mathematics subjects between January 1, 2002, and December 31, 2016 (n = 542 500). Data analysis was conducted from March 1, 2018, to March 1, 2019.

Exposures

Clinical diagnosis by a psychiatrist of any mental disorder or 1 of 29 specific mental disorders before age 16 years.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Taking the final examination at the end of ninth grade and mean examination grades standardized as z scores with differences measured in SDs (standardized mean grade difference).

Results

Of the total study population (n = 629 622; 306 209 female and 323 413 male), 523 312 individuals (83%) took the final examination before 17 years of age and 38 001 (6%) had a mental disorder before that age. Among the 542 500 individuals (274 332 female and 268 168 male), the mean (SD) age was 16.1 (0.33) years for the females and 16.2 (0.34) years for the males. Among the 15 843 female and 22 158 male students with a mental disorder, a lower proportion took the final examination (0.52; 95% CI, 0.52-0.53) compared with individuals without a mental disorder (0.88; 95% CI, 0.88-0.88). Mental disorders affected the grades of male individuals (standardized mean grade difference, –0.30; 95% CI, –0.32 to –0.28) more than the grades of their female peers (standardized mean grade difference, –0.24; 95% CI, –0.25 to –0.22) when compared with same-sex individuals without mental disorders. Most specific mental disorders were associated with statistically significantly lower mean grades, with intellectual disability associated with the lowest grade in female and male students (standardized mean grade difference, –1.07 [95% CI, –1.23 to –0.91] and –1.03 [95% CI, –1.17 to –0.89]; P = .76 for sex differences in the mean grades). Female and male students with anorexia nervosa achieved statistically significantly higher grades on the final examination (standardized mean grade difference, 0.38 [95% CI, 0.32-0.44] and 0.31 [95% CI, 0.11-0.52]; P = .54 for sex differences in the mean grades) compared with their peers without this disorder. For those with anxiety, attachment, attention-deficit/hyperactivity, and other developmental disorders, female individuals attained relatively lower standardized mean grades compared with their male counterparts.

Conclusions and Relevance

Results of this study suggest that, in Denmark, almost all mental disorders in childhood or adolescence may be associated with a lower likelihood of taking the final examination at the end of ninth grade; those with specific disorders tended to achieve lower mean grades on the examination; and female, compared with male, individuals with certain mental disorders appeared to have relatively more impairment. These findings appear to emphasize the need to provide educational support to young people with mental disorders.

Introduction

Low educational achievement in childhood is associated with a range of adverse outcomes during adulthood, such as low socioeconomic status,1 poor mental and physical health,2 substance use problems,3 suicidal behavior,4 and premature death.5 In general, educational challenges have important individual, societal, and public health consequences.

Children and adolescents with mental health problems often struggle to succeed at school. Compared with their peers, they have more missed school days, their suspension and expulsion rates are 3 times higher,6,7 they are more likely to drop out of high school,8,9 and they have lower attendance in final examinations and lower test scores.10 Inattention, anxiety, depressed mood, or psychotic experiences can interfere with learning while in the classroom and can result in difficulties with finishing homework and lower performance during tests.11 Adverse effects of pharmacotherapy (eg, antipsychotics) may be another possible explanation.12 Moreover, genetic associations have been found between mental disorders and educational attainment, reading and spelling abilities,13,14 and intelligence.15 Students with heritable mental disorders, whose parents are more likely to also have mental health disorders, may receive less parental support in attending examinations and/or doing their homework.16

Childhood symptoms of inattentiveness and hyperactivity,17,18,19 anxiety and depression,20,21 and conduct problems20,22 have been associated with lower school achievement later during adolescence. Several types of childhood-onset mental disorders, including autism spectrum disorder (ASD),23 attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder (ADHD),24,25,26,27 oppositional defiant disorder/conduct disorder (ODD/CD),28 substance use disorder,29 learning disorder and other developmental disorders,3 tic disorder,30 early-onset schizophrenia,31 bipolar disorder,32 obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD),33,34 and depression,35 have also been associated with low educational achievement. However, in most of these studies, the sample sizes were small, often only male participants were included, and the designs were retrospective. In addition, to our knowledge, no study has examined the implications of the full spectrum of mental disorders for educational achievement.

In this cohort study, we used nationwide population-based data and followed up a large cohort of children and adolescents prospectively with the aim of investigating the associations between mental disorders and subsequent school performance. First, we estimated the proportion of individuals with or without a mental disorder who took their final examination at the end of ninth grade (before age 17 years). Second, among those who completed the final examination, we estimated the standardized mean grade differences between groups of individuals with or without mental disorders.

Methods

Data Sources

Data for this study were obtained from the Danish Civil Registration System,36 which includes information on all people alive and residing in Denmark from January 1, 1968, to the present. This system contains data on sex, date of birth, vital status, and a personal identification number, which enable accurate linkage across all public registers in Denmark.

This study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency, Statistics Denmark, and the Danish National Board of Health. Danish law does not require informed consent for registry-based studies.

Another source of information was the Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register.37 This registry contains data on all admissions to Danish psychiatric hospitals since 1969, and since 1995, it also includes all contacts to outpatient psychiatric services and visits to psychiatric emergency care units. Data for each hospital contact include diagnoses of mental disorders, according to the International Classification of Diseases, Eighth Revision (ICD-8),38 codes for records from 1969 and according to the ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Diagnostic Criteria for Research (ICD-10-DCR) codes for records from 1994.39

In Denmark, attending 9 years of school is compulsory for children and adolescents, and all students are assessed in the ninth grade with a final examination in the following subjects: Danish, English, mathematics, and physics or chemistry. The Student Register40 stores data on whether students have completed the examination, the date of the examination, and the examination grade.

Study Population

We studied 2 cohorts. The first cohort comprised all children born in Denmark between January 1, 1988, and July 1, 1999, who were alive at age 17 years. The second cohort included all Denmark-born children who, between January 1, 2002, and December 31, 2016, took the final examination in both Danish and mathematics. To reduce confounding by migrant status,41 we restricted the cohorts to individuals whose parents were both born in Denmark.

Exposures

As exposures, we examined a clinical diagnosis by a psychiatrist of any mental disorder or 1 of the following 29 mental disorders before 16 years of age and before the final examination at the end of ninth grade: organic mental disorder; substance use disorder, including alcohol and cannabis abuse; schizophrenia spectrum disorder, including schizophrenia; mood disorder, including bipolar disorder and unipolar depression; anxiety disorder, including OCD; eating disorder, including anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and eating disorder not otherwise specified; personality disorder; intellectual disability; ASD, including childhood autism and Asperger syndrome; ADHD, including ADHD-combined presentation; ODD/CD; other developmental disorders, including language disorder, learning disorder, and motor skills disorder; attachment disorder; and tic disorder. eTable 1 in the Supplement shows the ICD-8 and ICD-10-DCR diagnostic codes.

Outcomes

The first outcome was taking the ninth-grade examination in both Danish and mathematics before the age of 17 years. The second outcome was the mean examination grades in these 2 subjects. The third outcome was the individual examination grades in the 2 subjects. From 2002 to 2006, a 10-point scale for grades was used in Denmark. We converted the grades from the 10-point scale to a 7-point scale, which has been used since 2007, using the table shown in eTable 2 in the Supplement. We standardized the grades as z scores by subtracting the mean and dividing by the SD. Therefore, the estimated standardized mean grade differences were changes measured in SDs.

Statistical Analysis

Sex-specific proportions of individuals who took the final examination at the end of ninth grade were calculated for those with or without mental disorders, with 95% CIs. The associations between sex and these proportion differences were tested by adding the interaction term in a linear regression of the indicator of taking the examination. The calculation included the proportion of male students without the mental disorder in question taking the examination, minus the proportion of males with the mental disorder taking the examination, minus the same difference in their female counterparts. Positive values of the interaction term indicated that the disorder in question was associated with a lower prevalence of taking the examination for male, compared with female, students when accounting for the prevalence difference in female and male individuals without the mental disorder in question.

In addition, using linear regression, we estimated the differences in standardized mean grades and 95% CIs by mental disorder status. We adjusted for the calendar year of examination as a categorical variable, allowing for modification by sex. The associations between mental disorders and examination grades were also adjusted for variables that had previously been associated with IQ test scores at draft board examination scores.42 These variables included parental age (in 5-year bands), parental educational level (on 5 levels), birth order (first-, second-, third-, or fourth-born or later), singleton or multiples, and being small for gestational age (defined as the lowest 10% of birth weight for a given gestational week) in term-born (ie, gestational age of 37 weeks or later) or preterm offspring.

Stata, version 13 (StataCorp LLC), was used for all statistical analyses. An unpaired, 2-tailed t test was used to calculate P values for sex differences in mean grades. Two-sided P < .05 was a priori designated as statistically significant. Data analysis was conducted from March 1, 2018, to March 1, 2019.

Results

Of the total study population (n = 629 622; 306 209 female and 323 413 male), 523 312 individuals (83%) took the final examination before 17 years of age and 38 001 (6%) had a mental disorder before that age. Among the 542 500 individuals (274 332 female and 268 168 male) in cohort 2, the mean (SD) age was 16.1 (0.33) years for the females and 16.2 (0.34) years for the males.

Proportion Taking the Final Examination

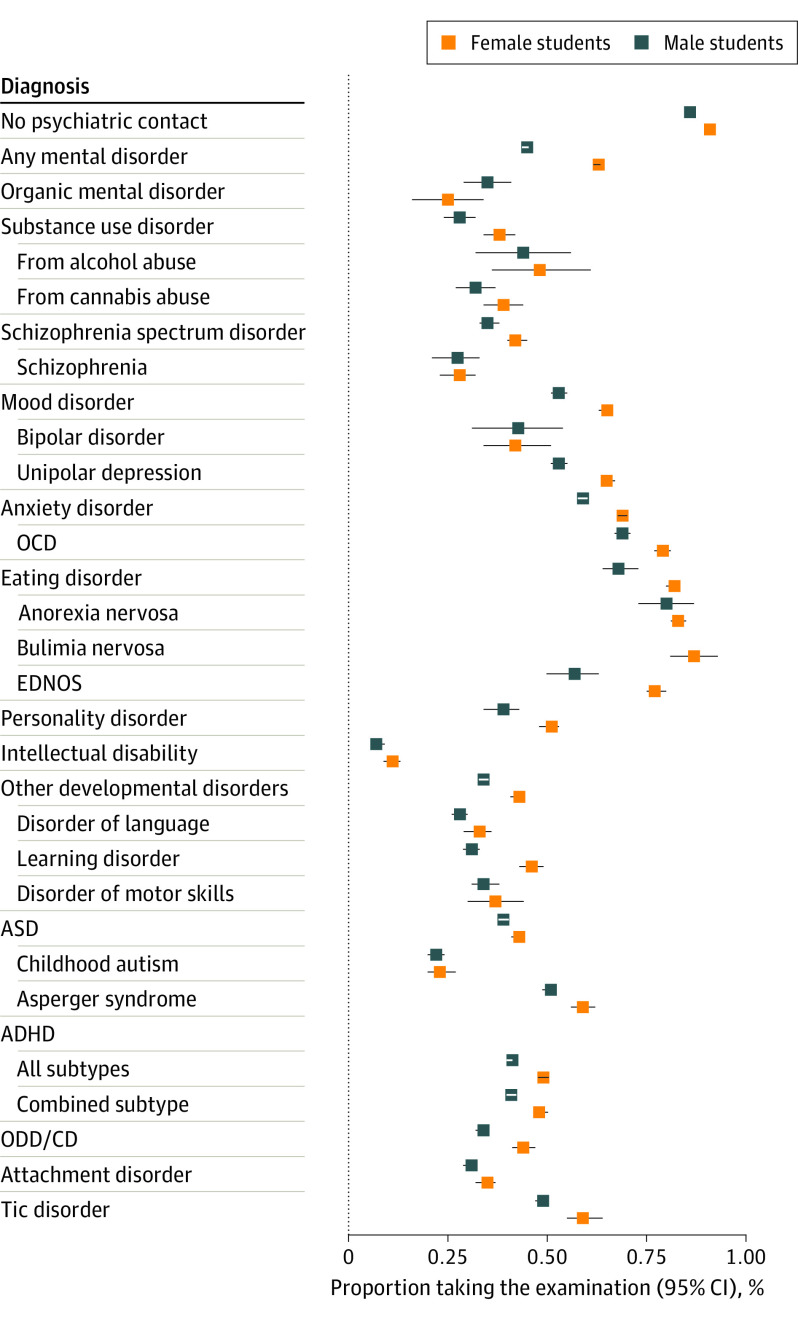

The proportion taking the ninth-grade final examination was lower among individuals with a mental disorder compared with those without such a diagnosis (0.52 [95% CI, 0.52-0.53] vs 0.88 [95% CI, 0.88-0.88]). The proportions taking the examination varied across the spectrum of mental disorders considered in this study and were lowest for individuals with intellectual disability (female: 0.11 [95% CI, 0.09-0.13]; male: 0.7 [95% CI, 0.06-0.09]) and highest for individuals with anorexia nervosa (female: 0.83 [95% CI, 0.81-0.85]; male: 0.80 [95% CI, 0.73-0.86]) (Figure). The proportions taking the final examination were significantly higher in female, compared with male, students both without (0.91 [95% CI, 0.91-0.91] vs 0.86 [95% CI, 0.86-0.86]; P < .001) and with (0.63 [95% CI, 0.62-0.63] vs 0.45 [95% CI, 0.44-0.45]; P < .001) mental disorders. Some of the categories of mental disorders also showed proportions that were higher for female than male individuals (organic disorders: 0.25 [95% CI, 0.16-0.34] vs 0.35 [95% CI, 0.29-0.41]; mood disorder: 0.65 [95% CI, 0.63-0.66] vs 0.53 [95% CI, 0.51-0.55]; anxiety disorder: 0.69 [95% CI, 0.68-0.70] vs 0.59 [95% CI, 0.58-0.60]; ASD: 0.43 [95% CI, 0.41-0.44] vs 0.39 [95% CI, 0.3-0.40]; and ADHD: 0.49 [95% CI, 0.48-0.50] vs 0.41 [95% CI, 0.40 to 0.41]), although the absolute difference was small for most of these disorders (Table 1).

Figure. Proportion of Young Individuals With or Without Mental Disorders Taking the Ninth-Grade Final Examination, With 95% CIs .

ADHD indicates attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ASD, autism spectrum disorder; EDNOS, eating disorder not otherwise specified; OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder; ODD/CD; oppositional defiant disorder/conduct disorder.

Table 1. Proportion of Denmark-Born Individuals With or Without Mental Disorders Taking the Ninth-Grade Final Examination Before Age 17 Years.

| Diagnosis | Proportion (95% CI) | Interaction term (95% CI)a | No. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | Female (n = 306 209) |

Male (n = 323 413) |

||

| No psychiatric contact | 0.91 (0.91 to 0.91) | 0.86 (0.86 to 0.86) | 290 366 | 301 255 | |

| Any mental disorder | 0.63 (0.62 to 0.63) | 0.45 (0.44 to 0.45) | 0.13 (0.12 to 0.13)b | 15 843 | 22 158 |

| Organic mental disorder | 0.25 (0.16 to 0.34) | 0.35 (0.29 to 0.41) | −0.17 (−0.28 to −0.05)c | 52 | 129 |

| Substance use disorder | 0.38 (0.34 to 0.42) | 0.28 (0.24 to 0.32) | 0.04 (−0.02 to 0.09) | 281 | 321 |

| From alcohol abuse | 0.48 (0.36 to 0.61) | 0.44 (0.32 to 0.56) | −0.02 (−0.19 to 0.15) | 29 | 32 |

| From cannabis abuse | 0.39 (0.34 to 0.44) | 0.32 (0.27 to 0.37) | −0.00 (−0.07 to 0.07) | 162 | 189 |

| Schizophrenia spectrum disorder | 0.42 (0.40 to 0.45) | 0.35 (0.33 to 0.38) | 0.00 (−0.04 to 0.04) | 764 | 547 |

| Schizophrenia | 0.28 (0.23 to 0.32) | 0.27 (0.21 to 0.33) | −0.06 (−0.14 to 0.01) | 203 | 137 |

| Mood disorder | 0.65 (0.63 to 0.66) | 0.53 (0.51 to 0.55) | 0.05 (0.02 to 0.07) d | 2363 | 1154 |

| Bipolar disorder | 0.42 (0.34 to 0.51) | 0.43 (0.31 to 0.54) | −0.07 (−0.22 to 0.07) | 64 | 35 |

| Unipolar depression | 0.65 (0.64 to 0.67) | 0.53 (0.51 to 0.55) | 0.05 (0.03 to 0.08)d | 2228 | 1030 |

| Anxiety disorder | 0.69 (0.68 to 0.70) | 0.59 (0.58 to 0.60) | 0.03 (0.02 to 0.04)d | 6845 | 4309 |

| OCD | 0.79 (0.77 to 0.81) | 0.69 (0.67 to 0.71) | 0.04 (0.01 to 0.07) | 1242 | 1107 |

| Eating disorder | 0.82 (0.80 to 0.83) | 0.68 (0.64 to 0.73) | 0.07 (0.02 to 0.11) | 2280 | 247 |

| Anorexia nervosa | 0.83 (0.81 to 0.85) | 0.80 (0.73 to 0.87) | −0.04 (−0.11 to 0.04)c | 1088 | 95 |

| Bulimia nervosa | 0.87 (0.81 to 0.93) | NA | NA | 134 | <5 |

| EDNOS | 0.77 (0.75 to 0.80) | 0.57 (0.50 to 0.63) | 0.14 (0.07 to 0.21)d | 797 | 109 |

| Personality disorder | 0.51 (0.48 to 0.53) | 0.39 (0.34 to 0.43) | 0.05 (−0.00 to 0.10) | 815 | 204 |

| Intellectual disability | 0.11 (0.09 to 0.13) | 0.07 (0.06 to 0.09) | −0.03 (−0.05 to −0.00)c | 1178 | 2386 |

| Other developmental disorders | 0.43 (0.41 to 0.44) | 0.34 (0.33 to 0.35) | 0.02 (0.00 to 0.04)c | 1519 | 4521 |

| Disorder of language | 0.33 (0.29 to 0.36) | 0.28 (0.26 to 0.30) | −0.02 (−0.06 to 0.02) | 402 | 1173 |

| Learning disorder | 0.46 (0.43 to 0.49) | 0.31 (0.29 to 0.33) | 0.08 (0.04 to 0.12)d | 385 | 1070 |

| Disorder of motoric skills | 0.37 (0.30 to 0.44) | 0.34 (0.31 to 0.38) | −0.04 (−0.12 to 0.04) | 92 | 461 |

| ASD | 0.43 (0.41 to 0.44) | 0.39 (0.38 to 0.40) | −0.02 (−0.04 to −0.00)c | 1729 | 5948 |

| Childhood autism | 0.23 (0.20 to 0.27) | 0.22 (0.20 to 0.24) | −0.05 (−0.09 to −0.01)c | 342 | 1406 |

| Asperger syndrome | 0.59 (0.56 to 0.62) | 0.51 (0.49 to 0.52) | 0.02 (−0.02 to 0.05) | 530 | 2107 |

| ADHD | |||||

| All subtypes | 0.49 (0.48 to 0.50) | 0.41 (0.40 to 0.41) | 0.03 (0.01 to 0.04)d | 2721 | 8172 |

| Combined subtype | 0.48 (0.47 to 0.50) | 0.41 (0.40 to 0.42) | 0.01 (−0.01 to 0.03) | 1525 | 5358 |

| ODD/CD | 0.44 (0.41 to 0.47) | 0.34 (0.32 to 0.35) | 0.04 (−0.00 to 0.07) | 417 | 1407 |

| Attachment disorder | 0.35 (0.32 to 0.37) | 0.31 (0.29 to 0.32) | 0.02 (−0.05 to 0.00) | 824 | 1501 |

| Tic disorder | 0.59 (0.55 to 0.64) | 0.49 (0.47 to 0.50) | 0.04 (−0.01 to 0.09) | 240 | 1322 |

Abbreviations: ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ASD, autism spectrum disorder; EDNOS, eating disorder not otherwise specified; NA, not applicable; OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder; ODD/CD, oppositional defiant disorder/conduct disorder.

Proportion of male students without a mental disorder taking the examination minus the proportion of male students with a mental disorder taking the examination, minus the same difference in their female counterparts; for example, for any disorder: (0.86 − 0.45) − (0.91 − 0.63) = 0.13.

P < .001.

P < .05.

P < .001.

Mean Final Examination Grades

Individuals with a mental disorder had lower mean grades on the final examination compared with those without a mental disorder. We found a statistically significant difference by sex, with male students with a mental disorder having lower mean grades than their female counterparts (standardized mean difference, –0.30 [95% CI, –0.32 to –0.28] vs –0.24 [95% CI, –0.25 to –0.22]; P < .001) compared with same-sex individuals without a mental disorder (Table 2).

Table 2. Standardized Mean Grade Difference at the Final Examination From 2002 to 2016 Between Denmark-Born Individuals With and Without Mental Disorders.

| Diagnosis | No. | Standardized mean grade difference (95% CI)a,b,c | P value for difference by sexd | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female (n = 274 332) | Male (n = 268 168) | Female | Male | ||

| Any mental disorder | 9923 | 9924 | −0.24 (−0.25 to −0.22) | −0.30 (−0.32 to −0.28) | <.001 |

| Organic mental disorder | 13 | 45 | −0.36 (−0.85 to 0.14) | −0.25 (−0.52 to 0.02) | .72 |

| Substance use disorder | 107 | 90 | −0.72 (−0.90 to −0.55) | −0.72 (−0.92 to −0.53) | >.99 |

| Alcohol abuse | 14 | 14 | −0.99 (−1.47 to −0.51) | −0.87 (−1.37 to −0.37) | .73 |

| Cannabis abuse | 63 | 61 | −0.67 (−0.90 to −0.44) | −0.76 (−0.99 to −0.53) | .61 |

| Schizophrenia spectrum disorder | 324 | 194 | −0.35 (−0.45 to −0.25) | −0.27 (−0.40 to −0.14) | .34 |

| Schizophrenia | 56 | 37 | −0.24 (−0.48 to 0.01) | −0.10 (−0.40 to 0.19) | .49 |

| Mood disorder | 1526 | 613 | −0.11 (−0.15 to −0.06) | −0.12 (−0.19 to −0.04) | .82 |

| Bipolar disorder | 27 | 15 | −0.09 (−0.43 to 0.26) | −0.06 (−0.52 to 0.40) | .92 |

| Unipolar depression | 1450 | 545 | −0.10 (−0.15 to −0.05) | −0.11 (−0.19 to −0.03) | .83 |

| Anxiety disorder | 4705 | 2540 | −0.21 (−0.24 to −0.19) | −0.16 (−0.19 to −0.12) | .02 |

| OCD | 985 | 763 | 0.01 (−0.05 to 0.07) | 0.07 (0.00 to 0.14) | .19 |

| Eating disorder | 1866 | 169 | 0.20 (0.16 to 0.24) | 0.14 (0.00 to 0.29) | .48 |

| Anorexia nervosa | 904 | 76 | 0.38 (0.32 to 0.44) | 0.31 (0.11 to 0.52) | .54 |

| Bulimia nervosa | 117 | <5 | 0.09 (−0.08 to 0.25) | NA | NA |

| EDNOS | 616 | 62 | −0.02 (−0.09 to 0.05) | −0.04 (−0.28 to 0.20) | .86 |

| Personality disorder | 412 | 79 | −0.38 (−0.47 to −0.29) | −0.35 (−0.56 to −0.14) | .76 |

| Intellectual disability | 129 | 171 | −1.07 (−1.23 to −0.91) | −1.03 (−1.17 to −0.89) | .76 |

| Other developmental disorders | 649 | 1541 | −0.71 (−0.78 to −0.64) | −0.56 (−0.61 to −0.52) | .001 |

| Disorder of language | 131 | 328 | −0.77 (−0.93 to −0.62) | −0.60 (−0.70 to −0.50) | .07 |

| Learning disorder | 177 | 333 | −0.98 (−1.12 to −0.84) | −0.83 (−0.93 to −0.73) | .08 |

| Disorder of motoric skills | 34 | 159 | −0.51 (−0.83 to −0.18) | −0.15 (−0.30 to −0.01) | .050 |

| ASD | 738 | 2301 | −0.14 (−0.20 to −0.07) | −0.13 (−0.17 to −0.09) | .90 |

| Childhood autism | 80 | 310 | −0.27 (−0.47 to −0.07) | −0.36 (−0.46 to −0.25) | .44 |

| Asperger syndrome | 312 | 1071 | −0.01 (−0.11 to 0.09) | 0.02 (−0.04 to 0.08) | .63 |

| ADHD | |||||

| All subtypes | 1338 | 3310 | −0.62 (−0.67 to −0.57) | −0.52 (−0.55 to −0.48) | .001 |

| Combined subtype | 739 | 2199 | −0.63 (−0.69 to −0.56) | −0.50 (−0.54 to −0.46) | .002 |

| ODD/CD | 183 | 474 | −0.56 (−0.69 to −0.42) | −0.43 (−0.51 to −0.35) | .12 |

| Attachment disorder | 287 | 461 | −0.59 (−0.70 to −0.48) | −0.24 (−0.33 to −0.16) | <.001 |

| Tic disorder | 142 | 643 | −0.16 (−0.31 to −0.01) | −0.17 (−0.24 to −0.09) | .95 |

Abbreviations: ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ASD, autism spectrum disorder; EDNOS, eating disorder not otherwise specified; NA, not applicable; OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder; ODD/CD, oppositional defiant disorder/conduct disorder.

Differences are measured in SDs, standardized as z scores by subtracting the mean and dividing by the SD.

Mean of the sum of the grade in the 2 subjects included in the ninth-grade final examination in Denmark: Danish and mathematics.

Analyses adjusted for year of final examination, parental age, parental educational level, birth order, singleton or multiples, preterm birth, and being small for gestational age.

P value for relative differences by sex in standardized mean grade in individuals with a specific mental disorder, compared with same-sex individuals without that mental disorder; for example, for any mental disorder, it tests if the difference in female students (−0.24) equals that in their male counterparts (−0.30).

Most of the specific mental disorders were associated with statistically significantly lower mean grades on the final examination. Female and male individuals with an intellectual disability received the lowest grades (standardized mean grade differences, –1.07 [95% CI, –1.23 to –0.91] and –1.03 [95% CI, –1.17 to –0.89]; P = .76 for sex differences in the mean grades). The mental disorders associated with the second and third lowest mean grades for female and male individuals were alcohol use disorder (standardized mean grade difference, –0.99 [95% CI, –1.47 to –0.51] and –0.87 [95% CI, –1.37 to –0.37]; P = .73) and learning disorder (standardized mean grade difference, –0.98 [95% CI, –1.12 to –0.84] and –0.83 [95% CI, –0.93 to –0.73]; P = .08). The mean grades differed across several categories of mental disorders. Female students, compared with male students, with ADHD obtained statistically significantly lower mean grades (standardized mean grade differences, –0.62 [95% CI, –0.67 to –0.57] vs –0.52 [95% CI, –0.55 to –0.48]; P = .001). Similar differences by sex were found in students with an anxiety disorder or attachment disorder, with female students attaining lower mean grades than male students vs same-sex individuals without an anxiety disorder (anxiety disorder: −0.21 [95% CI, −0.24 to −0.19] vs −0.16 [95% CI, −0.19 to −0.12]; P = .02; attachment disorder: −0.59 [95% CI, −0.70 to −0.48] vs −0.24 [95% CI, −0.33 to −0.16]; P < .001).

A few of the specific mental disorders were associated with significantly higher mean grades on the examination. The highest grades were found in both female and male individuals with anorexia nervosa (standardized mean difference, 0.38 [95% CI, 0.32-0.44] and 0.31 [95% CI, 0.11-0.52]; P = .54 for sex differences in the mean grades). Male students with OCD also had statistically significantly higher mean grades compared with male students without OCD (standardized mean difference, 0.07; 95% CI, 0.00-0.14). Individuals with Asperger syndrome received mean grades equal to the grades of those without this disorder (standardized mean grade difference in female and male students, –0.01 [95% CI, –0.11 to 0.09] vs 0.02 [95% CI, –0.04 to 0.08]; P = .63). The supplemental analyses of the obtained mean grades at examinations in Danish and mathematics, separately, produced similar findings as in the main analyses (eTables 3 and 4 in the Supplement).

Discussion

This nationwide cohort study on school achievement in children and adolescents with mental disorders has 3 main findings. First and foremost, all mental disorders diagnosed in childhood or adolescence were associated with a statistically significantly lower likelihood of taking the final examination at the end of ninth grade, the last year of compulsory schooling in Denmark. Second, among those who took the examination, the mean grades were significantly lower for individuals with mental disorders. The few exceptions to this finding were individuals who received a diagnosis of anorexia nervosa (both sexes) or OCD (male students only); they achieved statistically significantly higher mean grades on the examination than individuals without these mental disorders. Third, differences in school achievement by sex were observed for specific mental disorders. To our knowledge, this study is the first to address the association between the full spectrum of mental disorders and school achievement; therefore, its findings are largely unprecedented.

We found an association between a diagnosis of ADHD, ODD/CD, substance use disorder, learning disorder, language disorder, intellectual disability, or attachment disorder and lower mean grades for both female and male students. As expected, intellectual disability was associated with the lowest likelihood of taking the examination and the lowest mean grades in individuals who did take the examination. Childhood autism, unipolar depression, anxiety disorder, motor skills disorder, tic disorder (only in male individuals), schizophrenia spectrum disorder, and personality disorder were also associated with lower mean grades. Overall, these findings were consistent with those of previous single-disorder studies, including reports commissioned by US and European governmental offices,6,7 the National Comorbidity Survey,8,9 worldwide epidemiological studies,17,18,19,20,21,22 and numerous studies with small clinical samples focusing on a single mental disorder.3,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,32,33,34,35

Although most specific mental disorders were associated with lower grades on the examination, anorexia nervosa and OCD were associated with higher grades. These findings are novel yet supported by previous findings of high levels of perfectionism in both disorders,43,44 which correlates with higher academic achievement in college students.45

The identified associations between mental disorders and educational achievement are also supported by more recent evidence from genetic studies. These studies suggest that a negative genetic correlation existed between educational attainment and ADHD,13,14 cannabis use,46 ODD/CD,47 anxiety disorder,14 and depression,14,48 and a positive genetic correlation with bipolar disorder,14 childhood autism,49 Asperger syndrome,49 ASD,14,49 OCD,14 childhood cognitive ability,50 and anorexia nervosa14,51 was found. Findings on schizophrenia are consistent with previous findings of lower educational achievement in this group of patients31 as well as negative genetic correlations with educational attainment52 and intelligence.15 The association with schizophrenia is complex, as other studies have found schizophrenia to have positive genetic correlations with educational attainment but negative genetic correlations with intelligence.14,53 Mendelian randomization analysis suggests that the association with intelligence is bidirectional, given that intelligence has a protective effect on the risk of schizophrenia and, to some extent, schizophrenia also is associated with cognitive impairments.15

The present and previous findings for ASD are not supported by genetic studies, which have reported positive genetic correlations between ASD and educational attainment and IQ across different samples.14,49 We suggest 2 explanations for this divergence. The first is the presence of other phenotypic domains of ASD (also with a genetic correlation), such as low subjective well-being,49 low social attention,54 and neuroticism,49 that are associated with lower levels of school achievement. The second is the presence of comorbid mental disorders, such as ADHD and depression,55 which have a positive genetic correlation with ASD and a negative genetic correlation with educational attainment.13 Future studies of phenotypic and genetic correlations between ASD and education should scrutinize the implications of these confounders.

In addition, we found differences by sex, which may be of importance. For anxiety disorder, mood disorder, ADHD, and other developmental disorders, female individuals were more likely than their male peers with the same diagnoses to take the examination. However, for 3 of these disorders (not mood disorders), female students had substantially lower standardized mean grades than their male counterparts. This finding suggests that female students with these disorders may be perceived as being less impaired and/or more obedient, and their parents and/or teachers may be viewed as more likely to recommend taking the examination, although in reality these female students may be equally (or more) impaired than their male peers with the same disorders. In one study, among children with mental health problems, girls were perceived by both parents and teachers to be less impaired than boys.56 Detection of impairments across different diagnostic domains also depended on sex; for example, externalizing symptoms was more likely to go undetected in girls, whereas internalizing symptoms could go undetected in boys.57

In observational studies, low educational achievement in adolescence has been associated with serious long-term adverse outcomes. For instance, education was an important factor in future employment and higher income.58 Furthermore, low educational achievement was associated with less ability to access appropriate health services58,59 and with increased mortality rates.60 Among individuals with mental disorders, low educational attainment was found to be a risk factor in suicidal behavior.4

In a recent study, Lawrence et al61 found that students with mental disorders had lower mean school attendance rates compared with those without such disorders. The lower attendance started in primary school and worsened throughout secondary school, and school absences were mainly associated with symptoms of mental disorders. The disorders associated with the lowest attendance in the final 2 years of secondary school were anxiety, depression, and ADHD.61 Low school attendance in students with mental health disorders may exacerbate these symptoms and lead to even more absences.61 Therefore, we believe that breaking this vicious cycle by supporting consistent school attendance among children with mental disorders is critical to ensure optimal long-term educational achievement for this vulnerable group. Educational achievement may be improved among students with low school attendance, no matter the reason for absenteeism, if the teachers express their belief in the students’ capabilities.62 Similarly, a systematic review found that parental encouragement, teachers’ beliefs about students’ success, and early interventions were associated with better academic performance among students with socioeconomic disadvantages.63 Furthermore, strategies that can improve student mental health and well-being may also improve school attendance61 and grades.64

For children and adolescents, school is not merely for learning skills such as mathematics and writing but also for achieving developmental milestones and interacting with peers. Poor academic performance at the end of high school can have negative educational implications across one’s life span65 and can be an important factor associated with low socioeconomic attainment, family formation, health, and mortality.66 Mental health clinicians and other professionals serving children and adolescent populations should monitor school performance and work closely with school administrators, psychologists, and nurses as well as primary care physicians to improve educational achievements for this vulnerable group.

Strengths and Limitations

Although this study has methodological strengths, including availability of a large, nationwide population-based cohort enriched with validated clinical diagnoses67,68,69,70,71 and school achievement for all included individuals, it also has several limitations. Specifically, only hospitals report diagnoses to the Danish registries, and the small fraction of youths with a diagnosis by a private practice psychiatrist were not included.57 According to a recent study, 14% of all ADHD cases in Denmark were diagnosed outside the hospital72 and virtually no cases were diagnosed by general practitioners because only psychiatrists are allowed to treat mental disorders in persons younger than 18 years.73 Although we included the total Danish population (ie, a large comparison group), inclusion of missed (true) cases may have led to a slight underestimation of the generally negative association between mental disorders and educational achievement. However, this misclassification may not be random given that low parental socioeconomic status and female sex have been associated with a higher threshold for referral to clinical assessment for at least some mental disorders in children and adolescents.74 Economic factors are less likely to affect referral because public health care in Denmark is free. Still, those who received a diagnosis from psychiatrists in private practices (vs in hospitals) are most likely to have less severe impairment. Our findings, therefore, relate mainly to youths with moderately to severely impairing mental disorders.

Conclusions

This nationwide cohort study of school achievement in Denmark found that individuals with a mental disorder in childhood or adolescence appeared to be less likely than individuals without such a diagnosis to take the final examination at the end of compulsory school education. Furthermore, among those who took the examination, the individuals with a mental disorder obtained statistically significantly lower mean grades on the examination, compared with individuals without a mental disorder. We believe that these findings emphasize the need to provide additional support in school for children and adolescents with mental disorders.

eTable 1. Diagnostic Classification of Mental Disorders According to the ICD-10 and Corresponding ICD-8 Diagnoses

eTable 2. Transformation of Grades From Old Scale (Used Until 2007) to New Scale

eTable 3. Standardized Mean Grade Difference at the Final 9th Grade Exam in Danish During 2002-2016, in Individuals Who Sat the Exam (274,332 girls and 268,168 boys) for Individuals With Mental Disorders as Compared to Individuals Without Mental Disorders, Stratified on Sex and With 95% Confidence Intervals

eTable 4. Standardized Mean Grade Difference at the Final 9th Grade Exam in Mathematics During 2002-2016, in Individuals Who Sat the Exam (274,332 girls and 268,168 boys) for Individuals With Mental Disorders as Compared to Individuals Without Mental Disorders, Stratified on Sex and With 95% Confidence Intervals

References

- 1.Davies NM, Dickson M, Smith GD, van den Berg G, Windmeijer F. The causal effects of education on health outcomes in the UK Biobank. Nat Hum Behav. 2018;2(2):117-125. doi: 10.1038/s41562-017-0279-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doubeni CA, Laiyemo AO, Major JM, et al. Socioeconomic status and the risk of colorectal cancer: an analysis of more than a half million adults in the National Institutes of Health-AARP Diet and Health Study. Cancer. 2012;118(14):3636-3644. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patterson ML, Moniruzzaman A, Frankish CJ, Somers JM. Missed opportunities: childhood learning disabilities as early indicators of risk among homeless adults with mental illness in Vancouver, British Columbia. BMJ Open. 2012;2(6):e001586. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Osler M, Nybo Andersen AM, Nordentoft M. Impaired childhood development and suicidal behaviour in a cohort of Danish men born in 1953. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62(1):23-28. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.053330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh GK, Miller BA, Hankey BF, Edwards BK. Area Socioeconomic Variations in U.S. Cancer Incidence, Mortality, Stage, Treatment, and Survival, 1975–1999 NCI Cancer Surveillance Monograph Series, Number 4. NIH Publication No. 03-0000. National Cancer Institute; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blackorby J, Wagner M, Cameto R, et al. Engagement, Academics, Social Adjustment, and Independence: The Achievements of Elementary and Middle School Students With Disabilities. Office of Special Education Programs, US Department of Education. SRI International; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blackorby J, Wagner M, Levine P, et al. Changes in School Engagement and Academic Performance of Students With Disabilities. Office of Special Education Programs, US Department of Education. SRI International; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Breslau J, Lane M, Sampson N, Kessler RC. Mental disorders and subsequent educational attainment in a US national sample. J Psychiatr Res. 2008;42(9):708-716. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.01.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kessler RC, Foster CL, Saunders WB, Stang PE. Social consequences of psychiatric disorders, I: educational attainment. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(7):1026-1032. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.7.1026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fergusson DM, McLeod GF, Horwood LJ. Leaving school without qualifications and mental health problems to age 30. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2015;50(3):469-478. doi: 10.1007/s00127-014-0971-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corder K, Atkin AJ, Bamber DJ, et al. Revising on the run or studying on the sofa: prospective associations between physical activity, sedentary behaviour, and exam results in British adolescents. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2015;12:106. doi: 10.1186/s12966-015-0269-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van der Schans J, Vardar S, Çiçek R, et al. An explorative study of school performance and antipsychotic medication. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16(1):332. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-1041-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Demontis D, Walters RK, Martin J, et al. Discovery of the first genome-wide significant risk loci for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Nat Genet. 2019;51(1):63-75. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0269-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anttila V, Bulik-Sullivan B, Finucane HK, et al. ; Brainstorm Consortium . Analysis of shared heritability in common disorders of the brain. Science. 2018;360(6395):eaap8757. doi: 10.1126/science.aap8757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Savage JE, Jansen PR, Stringer S, et al. Genome-wide association meta-analysis in 269,867 individuals identifies new genetic and functional links to intelligence. Nat Genet. 2018;50(7):912-919. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0152-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Westerlund H, Rajaleid K, Virtanen P, Gustafsson PE, Nummi T, Hammarström A. Parental academic involvement in adolescence as predictor of mental health trajectories over the life course: a prospective population-based cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:653. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1977-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sayal K, Washbrook E, Propper C. Childhood behavior problems and academic outcomes in adolescence: longitudinal population-based study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;54(5):360-8.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2015.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sijtsema JJ, Verboom CE, Penninx BW, Verhulst FC, Ormel J. Psychopathology and academic performance, social well-being, and social preference at school: the TRAILS study. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2014;45(3):273-284. doi: 10.1007/s10578-013-0399-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Galéra C, Melchior M, Chastang JF, Bouvard MP, Fombonne E. Childhood and adolescent hyperactivity-inattention symptoms and academic achievement 8 years later: the GAZEL Youth study. Psychol Med. 2009;39(11):1895-1906. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709005510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Riglin L, Frederickson N, Shelton KH, Rice F. A longitudinal study of psychological functioning and academic attainment at the transition to secondary school. J Adolesc. 2013;36(3):507-517. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maurizi LK, Grogan-Kaylor A, Granillo MT, Delva J. The role of social relationships in the association between adolescents’ depressive symptoms and academic achievement. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2013;35(4):618-625. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang F, Chen X, Wang L. Relations between aggression and adjustment in chinese children: moderating effects of academic achievement. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2014;43(4):656-669. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.782816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keen D, Webster A, Ridley G. How well are children with autism spectrum disorder doing academically at school? An overview of the literature. Autism. 2016;20(3):276-294. doi: 10.1177/1362361315580962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barkley RA. Major life activity and health outcomes associated with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(suppl 12):10-15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tosto MG, Momi SK, Asherson P, Malki K. A systematic review of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and mathematical ability: current findings and future implications. BMC Med. 2015;13(1):204. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0414-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Currie J, Stabile M. Child mental health and human capital accumulation: the case of ADHD. J Health Econ. 2006;25(6):1094-1118. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2006.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Babinski DE, Pelham WE Jr, Molina BS, et al. Late adolescent and young adult outcomes of girls diagnosed with ADHD in childhood: an exploratory investigation. J Atten Disord. 2011;15(3):204-214. doi: 10.1177/1087054710361586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pajer K, Chung J, Leininger L, Wang W, Gardner W, Yeates K. Neuropsychological function in adolescent girls with conduct disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47(4):416-425. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181640828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hooper SR, Woolley D, De Bellis MD. Intellectual, neurocognitive, and academic achievement in abstinent adolescents with cannabis use disorder. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2014;231(8):1467-1477. doi: 10.1007/s00213-014-3463-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wei MH. The social adjustment, academic performance, and creativity of Taiwanese children with Tourette’s syndrome. Psychol Rep. 2011;108(3):791-798. doi: 10.2466/04.07.10.PR0.108.3.791-798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hakulinen C, McGrath JJ, Timmerman A, et al. The association between early-onset schizophrenia with employment, income, education, and cohabitation status: nationwide study with 35 years of follow-up. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2019;54(11):1343-1351. doi: 10.1007/s00127-019-01756-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arango C, Fraguas D, Parellada M. Differential neurodevelopmental trajectories in patients with early-onset bipolar and schizophrenia disorders. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40(suppl 2):S138-S146. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbt198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thomsen PH. Obsessive-compulsive disorder in children and adolescents. A 6-22 year follow-up study of social outcome. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;4(2):112-122. doi: 10.1007/BF01977739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pérez-Vigil A, Fernández de la Cruz L, Brander G, et al. Association of obsessive-compulsive disorder with objective indicators of educational attainment: a nationwide register-based sibling control study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(1):47-55. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.3523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ding W, Lehrer SF, Rosenquist JN, Audrain-McGovern J. The impact of poor health on academic performance: new evidence using genetic markers. J Health Econ. 2009;28(3):578-597. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2008.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pedersen CB, Gøtzsche H, Møller JØ, Mortensen PB. The Danish Civil Registration System: a cohort of eight million persons. Dan Med Bull. 2006;53(4):441-449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mors O, Perto GP, Mortensen PB. The Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7)(suppl):54-57. doi: 10.1177/1403494810395825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.World Health Organization International Classification of Diseases: Manual of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Injuries and Causes of Death (ICD-8). ed 8 rev. World Health Organization; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 39.World Health Organization The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders. Diagnostic Criteria for Research. World Health Organization; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jensen VM, Rasmussen AW. Danish education registers. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7)(suppl):91-94. doi: 10.1177/1403494810394715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cantor-Graae E, Pedersen CB. Full spectrum of psychiatric disorders related to foreign migration: a Danish population-based cohort study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(4):427-435. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McGrath JJ, Wray NR, Pedersen CB, Mortensen PB, Greve AN, Petersen L. The association between family history of mental disorders and general cognitive ability. Transl Psychiatry. 2014;4(7):e412. doi: 10.1038/tp.2014.60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bulik CM, Tozzi F, Anderson C, Mazzeo SE, Aggen S, Sullivan PF. The relation between eating disorders and components of perfectionism. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(2):366-368. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.2.366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Soreni N, Streiner D, McCabe R, et al. Dimensions of perfectionism in children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;23(2):136-143. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yanover T, Thompson JK. Eating problems, body image disturbances, and academic achievement: preliminary evaluation of the eating and body image disturbances academic interference scale. Int J Eat Disord. 2008;41(2):184-187. doi: 10.1002/eat.20483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Verweij KJ, Huizink AC, Agrawal A, Martin NG, Lynskey MT. Is the relationship between early-onset cannabis use and educational attainment causal or due to common liability? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;133(2):580-586. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.07.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tielbeek JJ, Johansson A, Polderman TJC, et al. ; Broad Antisocial Behavior Consortium collaborators . Genome-wide association studies of a broad spectrum of antisocial behavior. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(12):1242-1250. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.3069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wray NR, Ripke S, Mattheisen M, et al. ; eQTLGen; 23andMe; Major Depressive Disorder Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium . Genome-wide association analyses identify 44 risk variants and refine the genetic architecture of major depression. Nat Genet. 2018;50(5):668-681. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0090-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grove J, Ripke S, Als TD, et al. ; Autism Spectrum Disorder Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium; BUPGEN; Major Depressive Disorder Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium; 23andMe Research Team . Identification of common genetic risk variants for autism spectrum disorder. Nat Genet. 2019;51(3):431-444. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0344-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hagenaars SP, Harris SE, Davies G, et al. ; METASTROKE Consortium, International Consortium for Blood Pressure GWAS; SpiroMeta Consortium; CHARGE Consortium Pulmonary Group, CHARGE Consortium Aging and Longevity Group . Shared genetic aetiology between cognitive functions and physical and mental health in UK Biobank (N=112 151) and 24 GWAS consortia. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21(11):1624-1632. doi: 10.1038/mp.2015.225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Watson HJ, Yilmaz Z, Thornton LM, et al. ; Anorexia Nervosa Genetics Initiative; Eating Disorders Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium . Genome-wide association study identifies eight risk loci and implicates metabo-psychiatric origins for anorexia nervosa. Nat Genet. 2019;51(8):1207-1214. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0439-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sørensen HJ, Debost JC, Agerbo E, et al. Polygenic risk scores, school achievement, and risk for schizophrenia: a Danish population-based study. Biol Psychiatry. 2018;84(9):684-691. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2018.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Okbay A, Beauchamp JP, Fontana MA, et al. ; LifeLines Cohort Study . Genome-wide association study identifies 74 loci associated with educational attainment. Nature. 2016;533(7604):539-542. doi: 10.1038/nature17671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang L, Wang Y, Xu Q, et al. Heritability of reflexive social attention triggered by eye gaze and walking direction: common and unique genetic underpinnings. Psychol Med. Published online March 4, 2019. doi: 10.1017/S003329171900031X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lee PH, Anttila V, Won HJ, et al. ; Cross-Disorder Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Electronic address: plee0@mgh.harvard.edu; Cross-Disorder Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium . Genomic relationships, novel loci, and pleiotropic mechanisms across eight psychiatric disorders. Cell. 2019;179(7):1469-1482.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.11.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sellers R, Maughan B, Pickles A, Thapar A, Collishaw S. Trends in parent- and teacher-rated emotional, conduct and ADHD problems and their impact in prepubertal children in Great Britain: 1999-2008. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2015;56(1):49-57. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dalsgaard S, Thorsteinsson E, Trabjerg BB, et al. Incidence rates and cumulative incidences of the full spectrum of diagnosed mental disorders in childhood and adolescence. JAMA Psychiatry. Published online November 20, 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.3523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Galobardes B, Shaw M, Lawlor DA, Lynch JW, Davey Smith G. Indicators of socioeconomic position (part 1). J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(1):7-12. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.023531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Galobardes B, Shaw M, Lawlor DA, Lynch JW, Davey Smith G. Indicators of socioeconomic position (part 2). J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(2):95-101. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.028092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bonaccio M, Di Castelnuovo A, Costanzo S, et al. Interaction between education and income on the risk of all-cause mortality: prospective results from the MOLI-SANI study. Int J Public Health. 2016;61(7):765-776. doi: 10.1007/s00038-016-0822-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lawrence D, Dawson V, Houghton S, Goodsell B, Sawyer MG. Impact of mental disorders on attendance at school. Aust J Educ. 2019;63(1):5-21. doi: 10.1177/0004944118823576 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rubie-Davies C, Hattie J, Hamilton R. Expecting the best for students: teacher expectations and academic outcomes. Br J Educ Psychol. 2006;76(pt 3):429-444. doi: 10.1348/000709905X53589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Banerjee PA. A systematic review of factors linked to poor academic performance of disadvantaged students in science and maths in schools. Cogent Education. 2016;3(1):1-3. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2016.1178441 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Franklin C, Kim JS, Tripodi SJ. A meta-analysis of published school social work practice studies: 1980-2007. Res Soc Work Pract. 2009;19(6):667-677. doi: 10.1177/1049731508330224 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Needham BL, Crosnoe R, Muller C. Academic failure in secondary school: the inter-related role of health problems and educational context. Soc Probl. 2004;51(4):569-586. doi: 10.1525/sp.2004.51.4.569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Crosnoe R, Riegle-Crumb C, Muller C. Gender, self-perception, and academic problems in high school. Soc Probl. 2007;54(1):118-138. doi: 10.1525/sp.2007.54.1.118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Linnet KM, Wisborg K, Secher NJ, et al. Coffee consumption during pregnancy and the risk of hyperkinetic disorder and ADHD: a prospective cohort study. Acta Paediatr. 2009;98(1):173-179. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2008.00980.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dalsgaard S, Hansen N, Mortensen PB, Damm D, Thomsen PH. Reassessment of ADHD in a historical cohort of children treated with stimulants in the period 1969-1989. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;10(4):230-239. doi: 10.1007/s007870170012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mohr-Jensen C, Vinkel Koch S, Briciet Lauritsen M, Steinhausen HC. The validity and reliability of the diagnosis of hyperkinetic disorders in the Danish Psychiatric Central Research Registry. Eur Psychiatry. 2016;35:16-24. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2016.01.2427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Uggerby P, Østergaard SD, Røge R, Correll CU, Nielsen J. The validity of the schizophrenia diagnosis in the Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register is good. Dan Med J. 2013;60(2):A4578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jakobsen KD, Frederiksen JN, Hansen T, Jansson LB, Parnas J, Werge T. Reliability of clinical ICD-10 schizophrenia diagnoses. Nord J Psychiatry. 2005;59(3):209-212. doi: 10.1080/08039480510027698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Christensen J, Pedersen L, Sun Y, Dreier JW, Brikell I, Dalsgaard S. Association of prenatal exposure to valproate and other antiepileptic drugs with risk for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in offspring. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(1):e186606. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.6606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.The Danish Health Authority Clinical Guidelines for Pharmacological Treatment of Children and Adolescents With Psychiatric Disorders. Vol 9194 In Danish. Ministry of Health; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Madsen KB, Ravn MH, Arnfred J, Olsen J, Rask CU, Obel C. Characteristics of undiagnosed children with parent-reported ADHD behaviour. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2018;27(2):149-158. doi: 10.1007/s00787-017-1029-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Diagnostic Classification of Mental Disorders According to the ICD-10 and Corresponding ICD-8 Diagnoses

eTable 2. Transformation of Grades From Old Scale (Used Until 2007) to New Scale

eTable 3. Standardized Mean Grade Difference at the Final 9th Grade Exam in Danish During 2002-2016, in Individuals Who Sat the Exam (274,332 girls and 268,168 boys) for Individuals With Mental Disorders as Compared to Individuals Without Mental Disorders, Stratified on Sex and With 95% Confidence Intervals

eTable 4. Standardized Mean Grade Difference at the Final 9th Grade Exam in Mathematics During 2002-2016, in Individuals Who Sat the Exam (274,332 girls and 268,168 boys) for Individuals With Mental Disorders as Compared to Individuals Without Mental Disorders, Stratified on Sex and With 95% Confidence Intervals