Abstract

Drawing on advances in chronic pain metrics, a simplified Graded Chronic Pain Scale Revised (GCPS-R) was developed to differentiate mild, bothersome and high impact chronic pain. GCPS-R was validated among adult enrollees of two health plans (N=2021). In this population, the prevalence of chronic pain (pain present most or every day, prior 3 months) was 40.5%: 15.4% with mild chronic pain (lower pain intensity and interference); 10.1% bothersome chronic pain (moderate to severe pain intensity with lower life activities interference); and 15.0% high impact chronic pain (sustained pain-related activity limitations). Persons with mild chronic pain versus those without chronic pain showed small differences on ten health status indicators (unfavorable health perceptions, activity limitations, receiving long-term opioid therapy), with non-significant differences for 7 of 10 indicators. Persons with bothersome versus mild chronic pain differed significantly on 6 of 10 indicators (e.g., negative pain coping beliefs, psychological distress, unfavorable health perceptions and pain-related interference with overall activities). Persons with high impact chronic pain differed significantly from those with mild chronic pain on all 10 indicators. Persons with high impact chronic pain, relative to those with bothersome chronic pain, were more likely to have substantial activity limitations (significant differences for 4 of 5 disability indicators) and more often received long-term opioid therapy. GCPS-R strongly predicted five activity limitation indicators with area under receiver operating characteristic curve coefficients of 0.76 to 0.89. We conclude that the 5 item GCPS-R and its scoring rules provide a brief, simple and valid method for assessing chronic pain.

INTRODUCTION

The Graded Chronic Pain Scale (GCPS) is widely used to assess chronic pain [37] for anatomically-defined pain conditions [10,11,27,32,36,37].

Its unique value is differentiating severity grades based on a small number of test items, while providing a brief dimensional measure of chronic pain severity (meaning pain intensity and impact on life activities). A brief, simple, easy to score scale can increase chronic pain assessment in health research and clinical practice.

Three developments in pain metrics necessitate replacing the original GCPS with new test items and grading criteria: 1) new operational definitions of chronic pain and high impact chronic pain [8,9,14,38]; 2) simpler test items for assessing chronic pain persistence and severity [8,38]; and, 3) growing evidence that generic assessment of chronic pain severity is valid [26,38]. Persons debilitated by chronic pain often have pain at multiple sites [7,25,38], providing a rationale for assessment without reference to anatomically defined pain conditions. The Graded Chronic Pain Scale-Revised (GCPS-R) asks about pain in general, rather than grading specific pain conditions separately.

GCPS-R identifies persons with chronic pain and grades chronic pain severity (mild, bothersome, high impact chronic pain). Chronic pain has been operationally defined as pain present on at least half the days over 3, 6, or 12 months [9,14]. High impact chronic pain has been defined by sustained pain-related limitations in work, social and self-care activities [8,38]. GCPS-R employs 2 simple questions [8] to identify chronic pain and high impact chronic pain. .

The 3 item Pain, Enjoyment and General Activities (PEG) scale is responsive to change [21] and widely used to assess pain severity over a one week period [22]. Research has found that pain ratings of about 4 to 5 on 0 to 10 rating scales differentiate mild from bothersome pain severity [3,13,17,34], providing empirically-derived cut points. . These findings support use of the PEG to differentiate mild and bothersome chronic pain and to provide a continuous measure of chronic pain severity, in place of six 0–10 pain ratings in the original GCPS.

The original GCPS offered alternative time frames (1, 3 or 6 months), which complicated scoring and affected pain grading results. Based on this experience, GCPS-R time frames were standardized. Diary studies of chronic pain have found good agreement between pain recall over 3 months with corresponding daily diary measures [29,33,36], whereas longer recall intervals have not been tested. The GCPS-R employs a standard 3 month recall period for assessing chronic pain and high impact chronic pain, and the PEG’s one week time frame for assessing current pain severity.

Due to the varying time frames and complexities in scoring GCPS pain days items in combination with 0–10 pain ratings, GCPS scoring rules were complex. By simplifying the test items and classification rules, and standardizing time frames, GCPS-R grading rules were simplified.

This paper reports initial assessment of GCPS-R validity for concurrent prediction of ten indicators of unfavorable health and chronic pain status. We discuss issues in transitioning to the GCPS-R for legacy studies using the original GCPS.

METHODS

Analyses assessing GCPS-R and its concurrent validity employ survey data and linked electronic health care data. The surveys were conducted in the adult populations of Kaiser Permanente Washington and Kaiser Permanente Northwest (Oregon). The research was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of both health care organizations.

Survey methods:

Stratified random samples of the adult populations served by each health care system were drawn for web-based surveys among those with email addresses on file. The populations were stratified into those with frequent pain-related health care visits in the prior two years (in the top 6% of pain-related health care use) and those with less frequent pain-related health care visits (the remaining 94% of the population). Within each stratum, approximately equal numbers of persons were sampled for inclusion in the survey. This sampling method was employed to increase the yield of respondents with high impact chronic pain.

Health plan enrollees selected for the sample were mailed a letter describing the survey with a $2 pre-incentive payment. They were informed that they would be contacted by email and potentially by telephone; that participation was voluntary; and that completing the survey would take about 10 to 15 minutes.

Persons choosing to participate could complete the survey by linking to a web-based self-administered survey. The survey was carried out from August 2017 through March 2018. Persons who did not complete the web-based survey within two weeks were called by survey interviewers working for the Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute Survey Center. When telephoned, persons were offered the option of completing the survey by telephone interview. Persons who did not agree to linkage of their electronic health care data to survey responses were considered non-respondents.

After respondents completed the survey, demographic information and utilization data for the two years prior to sample selection were obtained from electronic health plan records and linked to survey questionnaire data. Sample weights were estimated and applied to permit unbiased estimates for the populations surveyed.

GCPS-R Items and Scoring

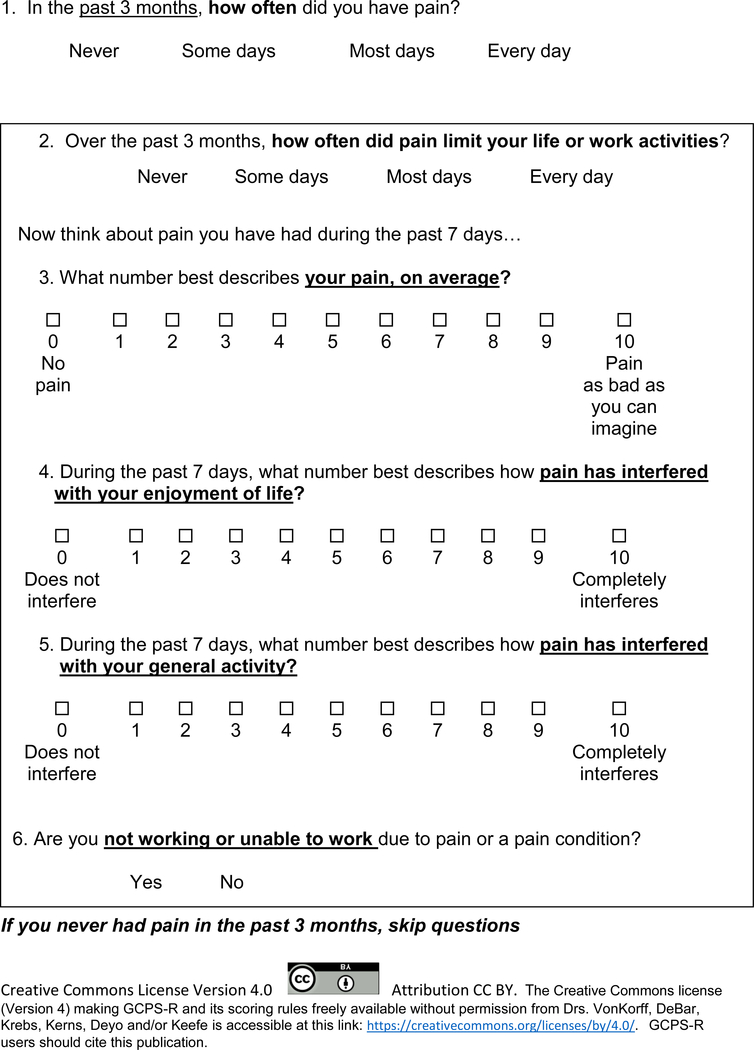

Proposed GCPS-R items are shown in Figure 1. The rationale and empirical support for each GCPS-R item is described here in order of appearance in the GCPS-R.

Figure 1:

Graded Chronic Pain Scale - Revised

Chronic pain and high impact chronic pain (Items 1 and 2):

To identify persons with chronic pain, respondents were asked on how many days they had pain during the prior 3 months: never, some days, most days, every day. The accuracy of self-reported pain days has been validated for 3 months in daily diary studies [33]. We assessed the agreement of this classification of chronic pain with the report of pain on more than half of the days in the past 6 months (see Results section).

To identify persons with high impact chronic pain, respondents were asked how often pain limited life or work activities (never, some days, most days, every day) [8], with high impact chronic pain defined by pain limiting life or work activities most or every day in the prior 3 months. The rationale for a 3 month time period is based in studies using daily diary data to assess validity [29,33,36], which have found good agreement between pain-related activity limitation days assessed by daily diary over 3 months and retrospective self-report of pain-related activity limitation days.

These items were developed through work carried out for the United States National Pain Strategy. In 2014, an initial pilot survey was conducted to assess test items for identifying chronic pain and high impact chronic pain [38]. For this pilot survey, chronic pain was defined as pain present “on at least half the days in 6 months.” Among persons with chronic pain, high impact chronic pain was defined by reporting severe interference with life activities (on a none, mild, moderate or severe rating scale), and/or by reporting pain limiting life or work activities usually or always (on a never, rarely, sometimes, usually or always rating scale).

The pilot survey found that the item assessing frequency of limitations with life activities performed well in identifying persons with high impact chronic pain and showed good agreement with the severity rating (kappa agreement statistic = 0.57). The frequency ratings for pain interference showed very high agreement across items asking about different kinds of activities.

In 2014, the United States Public Health Service set national goals pertaining to reducing the prevalence of high impact chronic pain for Healthy People 2020 [15]. As a result, the United States National Center for Health Statistics agreed to include a few items in the 2016 National Health Interview Survey to determine the prevalence of chronic pain and high impact chronic pain in a large probability sample of the United States adult population. Relevant items from the National Pain Strategy pilot survey were assessed by the National Center for Health Statistics cognitive laboratory. Based on this work, cognitive laboratory staff reported that it was easier for persons to report how often pain was present as “Not at all, Some days, Most days, Every day”. The same rating scale was employed for the item asking how often pain limited life or work activities. Based on National Health Interview Survey results for the U.S. adult population, the prevalence of high impact chronic pain was estimated to be 8%, defined by reporting that pain limited life or work activities most days or every day in the prior 6 months, while the prevalence of chronic pain was 20%, defined as pain present on most days or every day in the prior 6 months [8].

PEG Scale (Items 3–5):

Participants rated the 3 item PEG (pain, enjoyment, general activity) scale assessing pain severity over the past week (7 days) on 0–10 rating scales [22]. The reasons for selecting these 3 items are described elsewhere [22], but included simplicity, favorable psychometric properties and comparable performance among depressed and non-depressed persons. A sum score of 12 or greater was used for the GCPS-R to identify those with moderate to severe pain (i.e. the mean of the 3 PEG items was 4 or greater). Prior research has placed optimal cut points differentiating mild and moderate pain around 4 to 5 on 0–10 rating scales [3,13,17]. This research also suggests that optimal cut points for mild versus moderate pain severity varies somewhat across populations and measures. But the large majority of patients report that they would find a pain rating of less than 4 acceptable if that pain level were sustained long-term [34]. Based on these results, we set a PEG summary score of 12 or greater (i.e. equivalent to an average score of 4 or greater across the 3 items) as defining bothersome chronic pain, while a PEG score of 11 or less was classified as mild chronic pain.

The 3 item PEG has been shown to be more responsive to change than the 7 item GCPS [21]. The PEG’s 7 day time frame is appropriate for assessing current pain severity, which is important if GCPS-R were used to assess changes in pain severity over time, in a clinical trial for example. The test-retest reliability, internal consistency, and responsiveness to change of the PEG have been established in prior research [5,19,21,22].

Unable to work due to pain (Item 6):

The GCPS-R includes an additional item not used to grade chronic pain severity: “Are you not working or unable to work due to pain or a pain condition.” This developmental item is included to permit identification of persons currently not working due to pain.

GCPS-R:

The six items included in the GCPS-R are provided in Figure 1. Person who report no pain in the prior 3 months on the first item can skip the remaining five items.

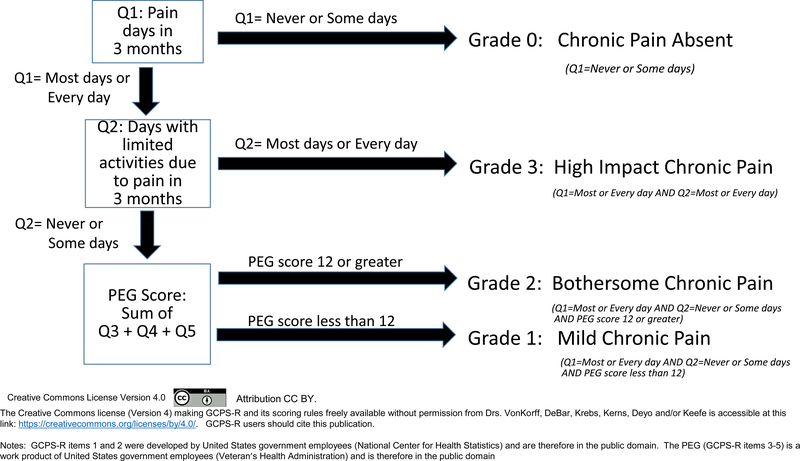

GCPS-R scoring:

The scoring algorithm for the GCPS-R is explained in Figure 2. Persons reporting no pain or pain on some days on Item 1 (i.e., pain not present on most days or every day) are placed at Grade 0—chronic pain absent. Some persons with pain that may be bothersome or have high impact, but who do not report chronic pain, may be included in Grade 0.

Figure 2:

Chronic pain grade scoring rules for Graded Chronic Pain Scale – Revised

Persons with chronic pain are placed at Grades 1, 2 or 3. Among persons with chronic pain, those who report that pain limits their life activities or work on most days or every day in the past 3 months (Item 2) are placed at Grade 3 (High impact chronic pain). Among the remaining persons with chronic pain, those with a PEG total score of 12 or greater are placed at Grade 2 (Bothersome chronic pain). Those with chronic pain that is not high impact and whose PEG score is less than 12 are placed at Grade 1 (Mild chronic pain).

There are several differences between the GCPS-R and original GCPS scoring algorithms. The original GCPS did not differentiate persons with and without chronic pain per se. The original GCPS included an extra item asking about pain days in the prior 6 months that could be used to assess chronic pain status [36], but it was not incorporated in GCPS scoring. In the original GCPS, persons with high pain-related disability could be placed at Grade 3 or 4, whereas GCPS-R places all persons with high pain-related disability in a single grade (GCPS-R Grade 3), corresponding to high impact chronic pain [8,38]. The GCPS-R distinction between Grades 1 and 2 (mild versus bothersome chronic pain) is based on a PEG score of 12 or greater (corresponding to an average item rating of 4 on 0 to 10 pain ratings). For the original GCPS, Grades 1 and 2 differentiated persons with low versus high pain intensity, with high pain intensity defined by an average pain intensity rating of 5 or greater on ratings of average pain, worst pain and current pain. The lower threshold for bothersome pain was selected because: 1) the PEG includes not only a pain intensity item but also ratings of pain-related interference with activities and enjoyment of life, whereas the original GCPS only considered pain intensity in differentiating Grades 1 and 2, and 2) research has established that patients typically would regard a pain level of less than 4 acceptable if sustained long-term [34].

Indicators for assessing GCPS-R concurrent validity

The GCPS-R’s concurrent validity was assessed relative to 2 indicators of unfavorable health status, 2 indicators of negative pain coping beliefs, 5 indicators of activity limitations, and 1 indicator of long-term opioid therapy. We also assessed GCPS-R high impact chronic pain (Grade 3) sensitivity in identifying persons with chronic pain who rated their pain as “severe”, and persons who said they were unemployed, laid off, or unable to work due to pain.

Health status

Self-rated health status:

Survey respondents rated their health as excellent, very good, good, fair or poor, with fair or poor ratings being classified as unfavorable. Self-rated health status predicts a wide range of unfavorable health outcomes, including increased mortality [39].

Depressive and anxiety symptoms:

The Patient Health Questionnaire 4 item scale (PHQ-4) was used to assess psychological distress. PHQ-4 items rate the frequency of two depressive and two anxiety symptoms in the past 2 weeks as “not at all (0)”, “a few days (1)”, “more than half the days (2)”: and “nearly every day (3)”, with a sum score of 6 or greater used to identify persons with moderate to severe symptoms [24]. Depressive and anxiety symptoms predict unfavorable chronic pain outcomes and greater disability among persons with chronic pain [1,2,23,35].

Negative pain coping beliefs

Negative perceptions related to pain coping were assessed using two items from the Start Back screener [16] adapted from items assessing pain-related fear-avoidance and pain coping strategies.

Fear avoidance:

The first item assessed fear-avoidance beliefs (It’s not really safe for a person with a pain condition like mine to be physically active. Agree/disagree).

Catastrophizing:

The second item assessed pain catastrophizing (I feel that my pain is terrible and it’s never going to get any better. Agree/Disagree).

These items were selected because of their prognostic significance for unfavorable chronic pain outcomes [16].

Activity limitations

Activity limitations were assessed with one item that asked about pain-related activity limitations, and four items that asked about health-related activity limitations without referring to pain.

Pain-related activity limitations:

Respondents were asked “Over the past 3 months, how much has pain interfered with your life activities?” rated as No interference, Mild interference, Moderate interference, or Severe interference [38]. We examined the association of the revised chronic pain grade with ratings of moderate to severe interference with life activities.

Health-related activity limitations:

Questions assessing health-related activity limitations without specifically mentioning pain were adapted from items used in the United States National Health Interview Survey [28]. The four activity limitation items were: (1) Participating in social or leisure activities; (2) Getting out with friends or family; (3) Doing household chores such as cooking and cleaning; and (4) Using transportation to get places you want to go. These activity limitations were rated as “No, not limited at all”; “Yes, limited a little”; or “Yes, limited a lot”. We examined the association of the revised chronic pain grade with reports of being limited a lot for each of the specific activity limitations.

Long-term opioid therapy:

Using electronic health records, we identified persons with prescriptions filled for opioids for at least 60 days’ supply in the 3 months prior to the sampling date, a validated classification of receiving long-term opioid therapy [4,12]. Opioid use was included as a validating measure because it is an indicator of unfavorable chronic pain status not based on self-report.

Unable to work due to pain:

Respondents were asked their current employment status (working full time or part time, retired, homemaker, student, unemployed, laid off, or unable to work). Persons who were unemployed, laid off, or unable to work were asked if they were unable to work due to pain or a pain condition.

Analyses:

We report population estimates based on conventional survey weighting methods for a stratified random sample [20]. Survey weights were estimated by dividing the number of persons in the source population within strata (high utilizer of pain-related services or not) by the number of survey respondents in each stratum. Weights were calculated for each population separately. These weights adjust for sample selection probabilities within each stratum as well as for differences in response rates within stratum. Weighted data provides unbiased estimates of means, variances and proportions for the surveyed population as a whole, not for the persons included in the survey which over-sampled persons with frequent use of health care for pain.

We compared the percent of persons with unfavorable health status and chronic pain status indicators by revised chronic pain grade using PROC SURVEYFREQ for a stratified random sample [30], providing unbiased estimates of population percentages.

We used the SAS logistic regression procedure for a stratified random sample [31] to assess whether there were differences in unfavorable health status indicators by chronic pain grade after adjusting for age and sex. The c-statistic estimated from the logistic regression models was used to estimate area under the receiver operating characteristic curve for prediction of each of the unfavorable health status indicators [18]. This logistic regression procedure provides unbiased population estimates of regression parameters and the c-statistic. A c-statistic of 0.5 means that prediction is no better than chance agreement, whereas a c-statistic of 0.7 or greater indicates good prediction and 0.8 or greater indicates strong prediction [18].

We evaluated differences in proportions across the 4 chronic pain grades by estimating ordinary chi-square statistics. P-values for the chi-square statistics are for two-sided tests. We also report odds ratios estimated via the logistic regression models with age and gender included as covariates. The adjusted odds ratios are reported with 95% confidence intervals. Confidence intervals that do not include an adjusted odds ratio (AOR) of 1.0 indicate that the difference exceeds chance expectation.

In unweighted analyses, we assessed the sensitivity of GCPS-R high impact chronic pain (Grade 3) for identifying persons with chronic pain who rated their pain as “severe” and persons with chronic pain who said they were unemployed, laid off or unable to work due to pain.

RESULTS

Survey response:

Among the 3462 persons sampled for the surveys and mailed an invitation letter, 134 were found to be ineligible. Of the 3328 who were eligible, usable surveys among persons agreeing to electronic health records linkage were obtained from 2021 (60.7%), with 1738 surveys completed by web survey and 283 completed by telephone interview. There were 1059 interviews completed among persons with frequent use of health care for pain, and 962 interviews completed among persons with less frequent use of health care for pain. As noted above, weighted estimates correct for the over-sampling of persons with frequent use of health care for pain conditions.

Description of the study sample:

Sixty-four percent of survey respondents were female and 42% were 65 years of age or older (unweighted data, Table 1). After applying survey weights, the weighted percentage female was 60% and the weighted percentage age 65 or older was 37%. The respondents were predominately White, non-Hispanic, reflecting the demographic characteristics of the health plan populations.

Table 1:

Description of the study sample

| Unweighted Number | Unweighted Percent | Weighted Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 725 | 35.9 % | 40.2 % |

| Female | 1296 | 64.1 % | 59.8 % |

| Age 18–44 | 466 | 23.1 % | 27.7 % |

| 45–64 | 714 | 35.3 % | 35.5 % |

| 65 + | 841 | 41.6 % | 36.8 % |

| Race/Ethnicity White, non-Hispanic | 1690 | 83.6 % | 82.9 % |

| Hispanic | 83 | 4.1 % | 4.3 % |

| Afro-American | 58 | 2.9 % | 2.3 % |

| Asian/Pacific Is. | 116 | 5.7 % | 7.2 % |

| Other | 40 | 2.0 % | 1.7 % |

| Unknown | 34 | 1.7 % | 2.1 % |

| Self-rated health Excellent/Very Good | 761 | 37.9 % | 48.0 % |

| Good | 783 | 39.0 % | 36.4 % |

| Fair/Poor | 464 | 23.1 % | 15.6 % |

| Employment Working FT/PT | 983 | 49.2 % | 57.3 % |

| Homemaker | 69 | 3.5 % | 3.2 % |

| Student | 17 | 0.9 % | 1.1 % |

| Retired | 793 | 39.7 % | 34.9 % |

| Unemployed/laid off | 29 | 1.5 % | 1.0 % |

| Unable to work pain-related | 76 | 3.8 % | 1.5 % |

| Unable to work-not pain-related | 33 | 1.7 % | 1.1 % |

| High utilizer of pain-related services (number of pain-related visits in the prior 2 years greater than 94% of adults) | 1059 | 52.4 % | 5.7 % |

| Pain > half the days prior 6 months | 1290 | 64.3 % | 48.4 % |

| Pain on most days prior 3 months | 1136 | 56.2 % | 40.5 % |

| Pain limited activities most days | 569 | 28.1 % | 15.6 % |

| Number of pain sites bothered alot | |||

| None | 216 | 11.9 % | 16.0 % |

| 1 | 499 | 27.5 % | 34.7 % |

| 2 | 557 | 30.7 % | 31.6 % |

| 3+ | 544 | 30.0 % | 17.7 % |

| Chronic Pain Grade – Revised | |||

| 0 - No chronic pain | 885 | 43.8 % | 59.5 % |

| 1 - Mild Chronic Pain | 317 | 15.7 % | 15.4 % |

| 2 - Bothersome Chronic Pain | 270 | 13.4 % | 10.1 % |

| 3 – High Impact Chronic Pain | 549 | 27.2 % | 15.0 % |

| All persons | 2021 | 100.0 % | 100.0 % |

Agreement of 3 and 6 month reports of chronic pain:

We compared self-report of pain on most days or every day for 3 months with report of pain on more than half the days for 6 months. The weighted estimate of the kappa agreement statistic [6] was 0.80 comparing 3 month and 6 month recall, reflecting excellent agreement between the two time frames. There was near perfect specificity of 3 month chronic pain classification relative to six months (specificity=97%). The sensitivity of 3 month report of pain on most days was also high (82%) relative to the 6 month classification. Given high agreement of chronic pain classification with 3 month versus 6 month pain days recall, the 3 month recall period was preferred for GCPS-R based on prior research confirming the validity of 3 month recall when compared to daily diary data. A second consideration was that persons reporting pain on most days in the prior 6 months, but not in the prior 3 months, may not be experiencing pain on most days in the most recent 3 month time period, suggesting that their chronic pain may have become less persistent in the 3 months preceding the assessment.

Prevalence of chronic pain:

In this survey population, the weighted estimate of the prevalence of chronic pain, defined as pain on most days or every day in the prior 3 months, was 40.5%. The weighted estimate of the prevalence of high impact chronic pain, defined as being limited in life or work activities on most days or every day in the prior 3 months was 15.0%. The weighted estimates of the prevalence of bothersome chronic pain was 10.1% while the prevalence of mild chronic pain was 15.4%.

Sensitivity of GCPS-R high impact chronic pain:

Among 246 survey respondents with chronic pain who rated their pain as “severe”, 236 (95.9%) were classified by the GCPS-R as having high impact chronic pain (Grade 3). Among the 129 persons with chronic pain who reported they were not working or unable to work due to pain, 112 (86.8%) were classified by the GCPS-R as having high impact chronic pain. Thus, the GCPS-R high impact chronic pain was highly sensitive in identifying persons with other indicators of high impact chronic pain.

Prevalence of unfavorable health status indicators by revised chronic pain grade:

There was a marked increase in the prevalence of each of the 10 unfavorable health status indicators among persons with bothersome chronic pain and high impact chronic pain relative to those without chronic pain and those with mild chronic pain (see Table 2). The differences in the prevalence of unfavorable health status indicators by Chronic Pain Grade Revised was highly statistically significant for each of the ten indicators (p<0.001).

Table 2.

Percent with unfavorable indicators by chronic pain grade (weighted estimates)

| Grade 0: Chronic Pain Absent | Grade 1: Mild Chronic Pain | Grade 2: Bothersome Chronic Pain | Grade 3: High Impact Chronic Pain | Chi-square (p-value) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative pain coping beliefs | |||||

| It’s not safe for a person with a pain condition like mine to be physically active (% agree) | 4.5 % | 2.1 % | 11.7 % | 17.0 % | X2= 76.8 p<.0001 |

| I feel that my pain is terrible and will never get better (% agree) | 4.3 % | 8.9 % | 24.1 % | 37.1 % | X2= 260.8 p<.0001 |

| Unfavorable health status | |||||

| Self-rated health (% Fair or poor) | 9.5 % | 13.5 % | 32.8 % | 30.7 % | X2= 131.7 p<.0001 |

| Elevated PHQ-4 depression/anxiety score (% 6 or greater) | 8.0 % | 7.9 % | 23.9 % | 26.9 % | X2= 109.3 p<.0001 |

| Activity limitations | |||||

| Pain interference with life activities (% Moderate or severe) | 9.7 % | 17.2 % | 60.0 % | 94.4 % | X2= 972.1 p<.0001 |

| Health limits doing household chores (% limited a lot) | 3.6 % | 3.1 % | 13.3 % | 37.5 % | X2= 336.9 p<.0001 |

| Health limits using transportation (% limited a lot) | 2.9 % | 2.4 % | 5.8 % | 11.7 % | X2= 47.6 p=.<.0001 |

| Health limits leisure activities (% limited a lot) | 4.2 % | 6.2 % | 6.2 % | 33.9 % | X2= 263.1 p<.0001 |

| Health limits getting out with friends or family (% limited a lot) | 3.7 % | 3.6 % | 6.3 % | 24.5 % | X2= 166.4 p<.0001 |

| Pain medication use | |||||

| Receipt of long-term opioid therapy (% received 60+ days supply of opioids in 3 months) | 0.3 % | 2.4 % | 2.7 % | 17.7 % | X2= 221.6 p<.0001 |

Persons with mild chronic pain compared to those without chronic pain:

Differences in the prevalence of unfavorable health perceptions and activity limitations between persons with mild chronic pain versus those without chronic pain were typically modest (Table 2). These differences exceeded chance expectation, as indicated by adjusted odds ratio (AOR) 95% confidence intervals that did not include 1, for only 3 of 10 comparisons (Tables 3 and 4). Significant differences were observed for one of two negative pain coping beliefs, one measure of pain-related activity limitation, and long-term opioid use, but not for any of four measures of health-related activity limitations, self-rated health status or elevated depression/anxiety symptoms.

Table 3.

Age-sex adjusted odds ratios (AOR) and 95% confidence intervals for comparison of negative pain coping beliefs and unfavorable health status indicators between persons at differing chronic pain grades

| Grade 0: Chronic Pain Absent (Relative to Grade 1) | Grade 1: Mild Chronic Pain (Reference category) | Grade 2: Bothersome Chronic Pain (Relative to Grade 1) | Grade 3: High Impact Chronic Pain (Relative to Grade 1) | Grade 3 relative to Grade 2 | c-statistic | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative pain coping beliefs | |||||||

| It’s not safe for a person with a pain condition like mine to be physically active (% agree) |

AOR = 2.0 (0.73 – 5.4) | AOR=1.0 | AOR=6.0 (2.0 – 18.3) | AOR=9.9 (3.6 – 27.0) | AOR=1.6 (0.8 – 3.6) | c=0.72 | |

| I feel that my pain is terrible and will never get better (% agree) |

AOR = 0.41 (0.19 – 0.87) | AOR=1.0 | AOR=3.3 (1.6 – 6.9) | AOR=6.6 (3.5 – 12.4) | AOR=2.0 (1.1 – 3.5) | c=0.79 | |

| Unfavorable health status | |||||||

| Self-rated health (% Fair or poor) | AOR = 0.68 (0.39 – 1.18) | AOR=1.0 | AOR=3.3 (1.8 – 6.1) | AOR=2.9 (1.7 – 5.1) | AOR=0.9(0.5 – 1.5) | c=0.71 | |

| Elevated PHQ-4 depression/anxiety score (% 6 or greater) | AOR = 0.83 (0.43 – 1.6) | AOR=1.0 | AOR=3.4 (1.6 – 7.1) | AOR=4.8 (2.4 –9.4) | AOR=1.4 (1.0 – 2.4) | c=0.72 |

NOTES: Adjusted odds ratios and their 95% confidence intervals shown in boldface have confidence intervals that do not include the estimate for the reference chronic pain grade, indicating that the differences exceed chance expectation.

The c statistic is interpreted as the probability that a randomly selected subject with the indicator (negative pain coping belief or unfavorable health status) will have a higher predicted probability of the indicator than a randomly selected subject without the indicator.

Table 4.

Age-sex adjusted odds ratios (AOR) and 95% confidence intervals for comparison of activity limitations and chronic opioid use between persons at differing chronic pain grades.

| Grade 0: Chronic Pain Absent (Relative to Grade 1) | Grade 1: Mild Chronic Pain (Reference category) | Grade 2: Bothersome Chronic Pain (Relative to Grade 1) | Grade 3: High Impact Chronic Pain (Relative to Grade 1) | Grade 3 Relative to Grade 2 | c-statistic | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activity limitations | |||||||

| Pain interference with life activities (% Moderate or severe) | AOR = 0.52 (0.31 – 0.87) | AOR=1.0 | AOR=7.1 (3.9 – 12.6) | AOR=82.0 (37.9 – 177.1) | AOR=11.6 (5.4 – 24.7) | c=0.89 | |

| Health limits doing household chores (% limited a lot) | AOR = 1.26 (0.49 – 3.2) | AOR=1.0 | AOR=4.7 (1.7 – 12.8) | AOR=18.2 (7.7 – 43.1) | AOR=3.9 (2.0 – 7.7) | c=0.82 | |

| Health limits using transportation (% limited a lot) | AOR = 1.5 (0.46 – 4.8) | AOR=1.0 | AOR=2.7 (0.69 –10.7) | AOR=5.3 (1.7 – 16.6) | AOR=1.9 (0.7 – 5.1) | c=0.76 | |

| Health limits leisure activities (% limited a lot) | AOR = 0.68 (0.31 – 1.5) | AOR=1.0 | AOR=0.96 (0.35 – 2.6) | AOR=7.6 (3.6 – 15.8) | AOR=7.9 (3.5 – 17.8) | c=0.78 | |

| Health limits getting out with friends or family (% limited a lot) | AOR = 1.0 (0.39 – 2.7) | AOR=1.0 | AOR=1.7 (0.54 – 5.5) | AOR=8.4 (3.4 – 21.0) | AOR=4.8 (2.1 – 11.5) | c=0.78 | |

| Long-term opioid therapy | |||||||

| Percent received 60+ days supply of opioids in 3 months | AOR = 0.11 (0.02 – 0.60) | AOR=1.0 | AOR=1.05 (0.3 – 3.6) | AOR=8.3 (3.2 – 21.7) | AOR=8.0 (3.0 – 21.4) | c=0.81 |

NOTES: Adjusted odds ratios and their 95% confidence intervals shown in boldface have confidence intervals that do not include the estimate for the reference chronic pain grade, indicating that differences exceed chance expectation.

The c statistic is interpreted as the probability that a randomly selected subject with the indicator (activity limitations) will have a higher predicted probability of the indicator than a randomly selected subject without the indicator.

Bothersome and high impact chronic pain compared to mild chronic pain:

In logistic regression analyses adjusted for respondent age and sex, we assessed whether adjusted odds ratio (AOR) confidence intervals showed differences between persons with bothersome and with high impact chronic pain relative to those with mild chronic pain.

Relative to persons with mild chronic pain, those with bothersome chronic pain were more likely to report negative pain coping beliefs, depressive/anxiety symptoms and unfavorable self-rated health status (Table 3). Similarly, those with high impact chronic pain were consistently more likely to report negative pain coping beliefs, unfavorable health perceptions and elevated levels of psychological distress than persons with mild chronic pain (Table 3).

Differences in activity limitations and in use of long-term opioid therapy were less consistent and pronounced when persons with bothersome chronic pain were compared to persons with mild chronic pain. Pain-related interference was significantly elevated among those with bothersome chronic pain relative to persons with mild chronic pain (Table 4), but only one of the four items assessing health-related activity limitations was significantly increased (limitations doing household chores) comparing persons with bothersome chronic pain to mild chronic pain. Likewise, the AOR confidence intervals for receiving long-term opioid therapy included 1.0 comparing persons with bothersome chronic pain to those with mild chronic pain (Table 4).

In contrast, persons with high impact chronic pain were consistently more likely to manifest activity limitations (including limitations in doing household chores, using transportation, leisure activities, and getting out with friends) than persons with mild chronic pain (AOR confidence intervals did not include 1.0 for each of the 5 activity limitation measures assessed, as shown in Table 4). Persons with high impact chronic pain were also more likely to receive long-term opioid therapy than persons with mild chronic pain (see Table 4, last row).

High impact chronic pain compared to bothersome chronic pain:

Tables 3 and 4 also include adjusted odds ratios comparing persons with high impact chronic pain to those with bothersome chronic pain as the reference group (AOR’s shown in the column comparing Grade 3 relative to Grade 2). Differences were inconsistent between high impact chronic pain and bothersome chronic pain for negative pain coping beliefs, depressive/anxiety symptoms and self-rated health status (Table 3) The contrast was greater than chance expectation for only one of two negative pain coping beliefs (“I feel that my pain is terrible and will never get better”) and for depressive symptoms. In contrast, persons with high impact chronic pain showed consistently higher levels of activity limitation relative to persons with bothersome chronic pain, and for receiving long-term opioid therapy (Table 4). The adjusted odds ratios comparing persons with high impact chronic pain to those with bothersome chronic pain did not include 1.0 (indicating differences exceeding chance expectation) for 4 of 5 activity limitation measures, and for receiving long-term opioid therapy.

GCPS-R prediction of unfavorable health status indicators:

The c-statistic from the logistic regression models, estimating the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve, are reported in the last columns of Tables 3 and 4. A c-statistic exceeding 0.7 indicates a good predictive model, while a value of 0.8 or greater indicates a strong predictive model [18]. In logistic regression models including only GCPS-R, age and sex, the c-statistics for concurrent prediction of negative pain coping beliefs, depressive/anxiety symptoms and unfavorable self-rated health indicated good prediction (c-statistics of 0.71 to 0.79). As shown in Table 4, the c-statistics for GCPS-R concurrent prediction of measures of activity limitation showed good to strong prediction (c-statistics of 0.76 to 0.89). GCPS-R concurrent prediction of receiving long-term opioid therapy was also strong (c-statistic = 0.81).

DISCUSSION

There is a need for brief, simple methods for identifying persons with mild, bothersome and high impact chronic pain while providing a brief, dimensional measure of pain severity. A brief, simple, easy to score scale can increase chronic pain assessment in health research and in clinical practice. To our knowledge, these needs have not been met by any existing generic pain scale. The Graded Chronic Pain Scale was revised to meet these needs.

The analyses reported in this paper supported the concurrent validity of the Graded Chronic Pain Scale Revised (GCPS-R). The GCPS-R showed highly significant differences across the 4 chronic pain grades for all ten indicators of unfavorable health status assessed. Differences between persons with bothersome chronic pain or high impact chronic pain relative to persons with mild chronic pain or without chronic pain were large and consistent. Differences between persons with mild chronic pain and those without chronic pain were inconsistent and modest, suggesting that persons with mild chronic pain experience quality of life, perceived health status, and levels of participation in key life activities similar to persons not affected by chronic pain.

Differences between persons with high impact chronic pain and those with bothersome chronic pain were large and consistent for measures of activity limitation, but not for pain coping beliefs, depressive/anxiety symptoms or self-rated health status. This suggests that high impact chronic pain differs from bothersome chronic pain primarily on the extent of activity limitations, consistent with the original definition of high impact chronic pain [8,38].

Generic versus condition-specific pain grading:

An important difference between the original GCPS and the revised version is that the GCPS-R grades chronic pain in general, whereas the original GCPS graded anatomically defined pain conditions separately. While the GCPS-R could be adapted to ask about condition-specific pain severity, accumulating evidence that persons with high impact chronic pain typically have multiple chronic pain conditions suggests conceptual advantages for generic assessment of chronic pain severity.

GCPS-R additional item:

The GCPS-R includes an additional item asking whether the person was not working or unable to work due to pain or a pain condition. This developmental item is not used to grade chronic pain. This additional item was included due to the clinical importance of identifying persons not working or unable to work due to pain. This item may be excluded or modified at the discretion of GCPS-R users without affecting chronic pain grade results based on the 5 item scale.

Implications for tailoring pain treatments:

Further studies using GCPS-R in diverse populations are needed to determine whether differences between persons with mild and bothersome chronic pain are predominately characterized by differences in measures of pain coping beliefs, psychological distress and health perceptions, while differences in life activity limitations differentiate persons with high impact chronic pain from those with mild chronic pain. If these findings replicated, it would have implications for tailoring cognitive-behavioral interventions by chronic pain grade to address psychological versus behavioral consequences of chronic pain.

GCPS-R advantages:

The revised Graded Chronic Pain Scale (GCPS-R) has simpler test items, and markedly simpler scoring than the original GCPS. Unlike the original GCPS, the GCPS-R differentiates persons with and without chronic pain, defined as pain present on most or every day in the prior 3 months. The 3 month time frame, rather than 6 months or one year, for defining chronic pain was used for two reasons. Retrospective reporting of pain days has been validated by daily diary studies for 3 month intervals but not for longer time periods [29,33,36]. And, there was high agreement between classification of chronic pain based on 3 month and 6 month recall in this study.

Among those with chronic pain, the GCPS-R differentiates persons with mild, bothersome and high impact chronic pain. The GCPS-R includes the widely used 3 item PEG scale [22], providing a brief, responsive, continuous measure of current pain severity which can be used to assess change in pain severity over time. All GCPS-R items are in the public domain and the GCPS-R scale and its scoring rules have been placed in the Creative Commons meaning that the scale and its scoring rules can be freely used without permission of GCPS-R authors.

Limitations:

This initial validation study had limitations. The study population was from the Pacific Northwest, and was predominately White, Non-Hispanic. The original GCPS has been tested in diverse populations worldwide and translated into many different languages. While the prior international experience with the original GCPS suggests the likely feasibility of using the GCPS-R in diverse populations, validation in diverse populations has not yet been done. The study population was also older than a representative population and was over 60 percent female, which may partially explain the higher prevalence of chronic pain and high impact chronic pain in the study population than reported for the U.S. adult population [8]. Further research testing the GCPS-R in diverse populations is needed. The GCPS-R identified persons with high impact chronic pain based on self-reported activity limitations related to pain, and was validated based on other measures of self-reported activity limitations. Assessment of validity would be strengthened based on activity limitation measures not based on self-report (e.g. observer ratings, employment records). This research was carried out through a web-survey with telephone follow-up. Response rates were about 60%, so non-response bias may affect results.

It should be noted that GCPS-R scoring places persons in Grade 0 (Chronic pain absent) who report pain that was not present on most days or every day in the prior 3 months. Some persons with acute pain may have significant pain-related activity limitations. The implications of grouping persons with and without pain in the chronic pain absent group merits future investigation.

There is no gold standard for grading chronic pain, so we did not validate the GCPS-R in comparison to a reference standard. Our survey did not include the original GCPS items, so it was not possible to directly compare the performance of the original GCPS to the revised version. This cross-sectional survey did not assess the test-retest reliability of the GCPS-R or its prospective predictive validity. However, the psychometric properties of the PEG have been previously assessed [5,19,21,22], and extensive research has been carried out on similar test items included in the original GCPS [35,37], including studies of prospective predictive validity.

Future research may identify improved classification rules for grading chronic pain, as well as improved items for brief assessment of chronic pain. Clinical application of the GCPS-R and its classification rules should be tentative until further research on its measurement properties and clinical interpretation is available across diverse populations and settings.

Transitioning from the original GCPS to GCPS-R:

Given the favorable results of this initial validity study, should the GCPS-R replace the original GCPS? Since GCPS-R identifies persons with chronic pain and high impact chronic pain based on current operational definitions [8,38], we recommend including the GCPS-R items in any newly initiated research that will grade chronic pain status. For ongoing studies using the original GCPS, if it is possible, we recommend adding at least GCPS-R items 1 and 2, to permit identification of chronic pain and high impact chronic pain using GCPS-R grading rules and current operational definitions. For legacy datasets based on the original GCPS, and for ongoing studies unable to add GCPS-R items, it may be possible to identify chronic pain and high impact chronic pain using the GCPS additional item on pain days and the GCPS item concerning activity limitation days due to pain. Mild and bothersome chronic pain could be differentiated using the original GCPS 0–10 pain ratings. Further studies are needed to develop methods to grade chronic pain based on current operational definitions identifying chronic pain and differentiating mild, bothersome and high impact chronic pain using the original GCPS items.

Conclusions:

In conclusion, the GCPS-R grades chronic pain based on 5 simple test items. Being unable to work due to pain is assessed by an additional item. The GCPS-R includes the widely used 3 item PEG which provides a brief, responsive, continuous measure of current chronic pain severity. The GCPS-R showed good concurrent prediction of negative pain coping beliefs, depression and unfavorable self-rated health status, and good to strong concurrent prediction of activity limitations and chronic opioid use. GCPS-R high impact chronic pain was highly sensitive in identifying persons with chronic pain who rated their pain severe, and persons who said they were unable to work due to pain. Our results support use of the GCPS-R and its simplified scoring rules for chronic pain assessment in epidemiologic and health services research. Since the GCPS-R incorporates the widely used PEG scale [22], the GCPS-R may be used in clinical settings requiring brief, simple chronic pain assessment, recognizing the need for further research assessing its clinical validity and interpretation. .

Acknowledgements:

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Common Fund, through a cooperative agreement (UH2AT007788, UH3NS088731) from the Office of Strategic Coordination within the Office of the NIH Director. The views presented here are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. No conflicts of interest exist for the authors of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arnow BA, Blasey CM, Constantino MJ, Robinson R, Hunkeler E, Lee J, Fireman B, Khaylis A, Feiner L, Hayward C. Catastrophizing, depression and pain-related disability. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2011; 33:150–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bair MJ, Poleshuck EL, Wu J, Krebs EK, Damush TM, Tu W, Kroenke K, Anxiety but not Social Stressors Predict 12-Month Depression and Pain Severity. Clin J Pain. 2013. February; 29(2):95–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boonstra AM, Schiphorst Preuper HR, Balk GA, Stewart RE. Cut-off points for mild, moderate, and severe pain on the visual analogue scale for pain in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Pain 2014; 155:2545–2550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bree Collaborative. Bree Collaborative Opioid Prescribing Metrics. http://www.breecollaborative.org/wp-content/uploads/Bree-Opioid-Prescribing-Metrics-Final-2017.pdf. Accessed 8/7/2019.

- 5.Chen CX, Kroenke K, Stump T, Kean J, Krebs EE, Bair MJ, Damush T, Monahan PO. Comparative responsiveness of the PROMIS pain interference short forms with legacy pain measures: results from three randomized clinical trials. J Pain 2019;20(6):664–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen J. “A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales”. Educational and Psychological Measurement 1960; 20(1):37–44 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Creed FH, Tomenson B, Chew-Graham C, Macfarlane GJ, Davies I, Jackson J, Littlewood A, McBeth J. Multiple somatic symptoms predict impaired health status in functional somatic syndromes. Int J Behav Med 2013; 20:194–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dahlhamer J, Lucas J, Zelaya C, Nahin R, Mackey S, DeBar L, Kerns R, Von Korff M, Porter L, Helmick C. Prevalence of Chronic Pain and High-Impact Chronic Pain Among Adults — United States, 2016 MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018. September 14; 67(36):1001–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deyo RA, Dworkin SF, Amtmann D, Andersson G, Borenstein D, Carragee E, Carrino J, Chou R, Cook K, DeLitto A, Goertz C, Khalsa P, Loeser J, Mackey S, Panagis J, Rainville J, Tosteson T, Turk D, Von Korff M, Weiner DK. Report of the NIH Task Force on research standard for chronic low back pain. J Pain 2014; 15:569–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elliott AM, Smith BH, Smith WC, Chambers WA. Changes in chronic pain severity over time: The Chronic Pain Grade as a valid measure. Pain 2000; 88:303–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elliott AM, Smith BH, Hannaford PC, Smith WC, Chambers WA. Assessing change in chronic pain severity: the chronic pain grade compared with retrospective perceptions. Br J Gen Pract 2002; 52:269–274. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fulton-Kehoe D, Von Korff M, Mai J, Weir V, Lofy K, Sabel J, Tauben D, Franklin G. Surveillance of Opioid Prescribing as a Public Health Intervention Washington State Bree Collaborative Opioid Metrics. J Public Health Management and Practice, In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerbershagen HJ, Rothaug J, Kalkman CJ, Meissner W. Determination of moderate-to-severe postoperative pain on the numeric rating scale: a cut-off point analysis applying four different methods. British Journal of Anaesthesia 2011; 107: 619–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society. ”The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 2nd Edition. Cephalalgia 2004; 24 (Supplement 1):1–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Helmick C. Adding chronic pain objectives to Healthy People 2020. Interagency pain research coordinating committee; September 22, 2014. https://www.iprcc.nih.gov/sites/default/files/2Helmick_HP2020.pdf. Accessed October 26, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hill JC, Dunn KM, Lewis M, Mullis R, Main CJ, Foster NE, Hay EM. A primary care back pain screening tool: identifying patient subgroups for initial treatment. Arthritis Care & Research 2008; 59:632–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirschfeld G, Zernikow B. Variability of “optimal” cut points for mild, moderate, and severe pain: neglected problems when comparing groups. Pain 2013; 154:154–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression (2nd Edition). New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kean J, Monahan P, Kroenke K, Wu J, Yu Z, Krebs EE. Comparative responsiveness of the PROMIS Pain Interference short forms, the Brief Pain Inventory, PEG, and SF-36 Bodily Pain subscale. Med Care 2016;54(4):414–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kish L. Survey sampling. Chapter 3: Stratified Sampling. pp 75–120. J. Wiley, 1965. 643 pages. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krebs EE, Bair MJ, Damush TM, Tu W, Wu J, Kroenke K. Comparative responsiveness of pain outcome measures among primary care patients with musculoskeletal pain. Med Care 2010; 48:1007–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krebs EE, Lorenz KA, Bair MJ, Damush TM, Jingwel W. Sutherland JM, Asch SM, Kroenke K. Development and initial validation of the PEG, a three-item scale assessing pain intensity and interference. J Gen Intern Med. 2009; 24: 733–738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kroenke K, Outcalt S, Krebs E, Bair MJ, Wu J, Chumbler N, Yu Z. Association between anxiety, health-related quality of life and functional impairment in primary care patients with chronic pain. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013; 35(4); 359–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Löwe B. (2009). An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ-4 Psychosomatics, 50: 613–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maixner W, Fillingim RB, Williams DA, Smith SB, Slade GD. Overlapping Chronic Pain Conditions: Implications for Diagnosis and Classification. J Pain 2016; 17: Supplement T93–T107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mallen CD, Thomas E, Belcher J, Rathod T, Croft P, Peat G. Point-of-care prognosis for common musculoskeletal pain in older adults. Jama Internal Med 2013; 173:1119–1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Penny KI, Purves AM, Smith BH, Chambers WA, Smith WC. Relationship between the chronic pain grade and measures of physical, social and psychological well-being. Pain 1999; 79:275–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pitcher MH, VonKorff M, Bushnell MC, Porter L. Prevalence and profile of high-impact chronic pain in the United States. J Pain 2019; 20:146–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salovey P, Seiber WJ, Smith AF, Turk DC, Jobe JB, Willis GB Reporting chronic pain episodes on health surveys. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Statistics 1992; 6:1–71. [Google Scholar]

- 30.SAS Inc. The SAS Survey Freq Procedure. https://support.sas.com/documentation/cdl/en/statug/63962/HTML/default/viewer.htm#surveyfreq_toc.htm. Accessed 8/7/2019.

- 31.SAS Inc. The SAS Survey Logistic Procedure. https://support.sas.com/documentation/cdl/en/statug/63033/HTML/default/viewer.htm#surveylogistic_toc.htm. Accessed 8/7/3019.

- 32.Smith BH, Penny KI, Purves AM, Munro C, Wilson B, Grimshaw J, Chambers WA, Smith WC. The Chronic Pain Grade questionnaire: validation and reliability in postal research. Pain 1997; 71:141–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Simon D, Liberman J, Von Korff M. Validity of an illness severity measure for headache in a population sample of migraine sufferers. Pain 1999; 79: 291–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tubach F, Ravaud P, Martin-Mola E, Awada H, Bellamy N, Bombardier C, Felson DT, Hajjaj-Hassouni N, Hochberg M, Logeart I, Matucci-Cerinic M, van de Laar M, van der Heijde D, Dougados M. Minimum clinically important improvement and patient acceptable symptom state in pain and function in rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, chronic back pain, hand osteoarthritis, and hip and knee osteoarthritis: Results from a prospective multinational study. Arthritis Care Res 2012; 64:1699–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.VonKorff M, Dunn KM. Chronic pain reconsidered. Pain 2008; 138:267–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Von Korff M. Assessment of Chronic Pain in Epidemiological and Health Services Research: Empirical Bases and New Directions Handbook of Pain Assessment: Third Edition Turk Dennis C.and Melzack Ronald, Editors. Guilford Press, New York: 2011; pp 455–473. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Von Korff M, Ormel J, Keefe F and Dworkin SF (1992) Grading the severity of chronic pain. Pain 1992; 50:133–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.VonKorff M, Scher AI, Helmick C, Carter-Pokras O, Dodick DW, Goulet J, Hamill-Ruth R, LeResche L, Porter L, Tait R, Terman G, Veasley C, Mackey S. United States National Pain Strategy for Population Research: Concepts, Definitions and Pilot Data. J Pain 2016; 17:1068–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zaiacova A, Dowd JB. Reliability of self-rated health in US adults. Am J Epidemiol 2011; 174:977–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]