ABSTRACT

Purpose

This scoping review explores what is known about the role of organizational and professional cultures in medication safety. The aim is to increase our understanding of ‘cultures’ within medication safety and provide an evidence base to shape governance arrangements.

Data sources

Databases searched are ASSIA, CINAHL, EMBASE, HMIC, IPA, MEDLINE, PsycINFO and SCOPUS.

Study selection

Inclusion criteria were original research and grey literature articles written in English and reporting the role of culture in medication safety on either organizational or professional levels, with a focus on nursing, medical and pharmacy professions. Articles were excluded if they did not conceptualize what was meant by ‘culture’ or its impact was not discussed.

Data extraction

Data were extracted for the following characteristics: author(s), title, location, methods, medication safety focus, professional group and role of culture in medication safety.

Results of data synthesis

A total of 1272 citations were reviewed, of which, 42 full-text articles were included in the synthesis. Four key themes were identified which influenced medication safety: professional identity, fear of litigation and punishment, hierarchy and pressure to conform to established culture. At times, the term ‘culture’ was used in a non-specific and arbitrary way, for example, as a metaphor for improving medication safety, but with little focus on what this meant in practice.

Conclusions

Organizational and professional cultures influence aspects of medication safety. Understanding the role these cultures play can help shape both local governance arrangements and the development of interventions which take into account the impact of these aspects of culture.

Keywords: medication safety, medication errors, organizational culture, professional culture, safety culture

Introduction

Ensuring the safe use of medicines is a key priority of health systems worldwide, with an estimated annual global cost of US$42 billion [1]. Medication safety refers not only to the safe prescribing, dispensing and administration of medicines [2] but also to medication errors, defined as ‘preventable events that lead to actual harm’ [3]. Medication safety is a complex concept, with errors often having multifactorial origins across the different stages of the prescribing, dispensing and administration [3].

The contribution of organizational culture to health systems and its role in failures in care is well-known [4–7]. Organizational culture can be defined as ‘the way things are done around here,’ encompassing shared values, behaviours and attitudes among members in an organization, thus influencing the way day-to-day activities are carried out [8–10]. The role of organizational culture is discussed both in pharmacy and nursing research. In pharmacy practice research, organizational culture has been discussed in the context of patient safety, for example, in light of dispensing errors, but also wider within its role in implementing organizational change [11, 12]. Within the nursing literature, organizational culture is viewed in light of wider healthcare performance [13]—for example, in light of facilitating systems change [14] and nursing turnover and satisfaction [15]. In the medical literature, there is less of a focus on organizational culture’s role on both wider performance and patient safety more generally.

‘Sub-cultures’ within organizations may also exist, serving to reinforce or challenge wider organizational aims [10, 16–18]. It has been argued that professional sub-cultures can be among the ‘strongest’ cultures within an organization [19, 20]. It is suggested that a safety culture can only be sustained if there are a shared set of beliefs, attitudes and norms around what is ‘safe’ [21]. Therefore, culturally accepted norms attached to professions may impact medication safety [22, 23]. Research into incident reporting and operating theatre safety has identified the important role that cultures and sub-cultures can play [21, 24]. Currently, there is limited medication safety research identifying the role of these cultures. The aims of this scoping review were first, to explore the way in which culture was understood within medication safety—that is, how it is being defined and used within the context of medication safety research and second, to explore the role of professional and organizational cultures in medication safety.

Methods

Arksey and O’Malley’s scoping review framework was used, which involves four steps: identifying the research question and relevant studies, selecting the studies, charting the information and reporting the results [25]. Scoping review methodologies have been used in recent years within the patient safety literature [26–28] and are useful in enabling a mapping of a broad field of research including different study designs and identifying gaps in the literature [25, 29]. Although later modifications of scoping review methodology have aimed to include a quality assessment stage [29–31], we did not include a quality assessment to ensure that relevant studies were included (e.g. insights into hospital reports of medication errors).

Search strategy

The following databases were searched: The Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (MEDLINE), EMBASE, SCOPUS, International Pharmaceutical Abstracts (IPA), Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA), PsycINFO, Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC) and the Cochrane Library. We searched these databases using key words attached to medication safety, culture and professional groups. Tables 1 and 2 highlight how these concepts were operationalized for the review. We focused on nurses, doctors and pharmacists as they have explicit roles within medication safety. An example search strategy can be found in the supplementary material.

Table 1.

Concepts included in review

| Concept | Keywords |

|---|---|

| Medication safety | Medication errors, adverse events, medicines reconciliation, medicines optimization, reporting errors, near-misses |

| Culture | Organizational culture, professional culture, safety culture, shared values, shared beliefs, shared attitudes and shared behaviours |

| Professional groups | Nurses, nursing, doctors, physicians, medicine, pharmacists and pharmacy |

Table 2.

Working definitions of the two aspects of culture

| Concept | Definition |

|---|---|

| Organizational culture | ‘the pattern of shared basic assumptions-invented, discovered or developed by a given group as it learns to cope with its problems of external adaptation and internal integration … to (teach) new members as the correct way to perceive, think and feel in relation to those problems’ [8] |

| Professional culture | ‘Values, beliefs, attitudes, customs and behaviours attached to a profession’ [81, 82] |

Study selection

Titles and abstracts were screened by SM based on the eligibility criteria available in the supplementary material. Studies were included if they clearly defined or conceptualized ‘culture’ and its role on any aspects of medication safety. To ensure reliability of the full-text review, 10% of the full-text articles were screened and reviewed by YJ. If agreement was >90%, then SM continued the screening process alone and at this stage agreement was 100%.

Charting the data and synthesis of results

Data were extracted for the following characteristics: author(s), title, year of publication, study location, methods used, medication safety focus, professional groups, culture focus and role of culture upon medication safety focus. We utilized both integrative and interpretive methods [32, 33]. Integrative methods combine and pool data, whereas interpretive methods use induction and interpretation to synthesize different types of literature [32, 33]. Integrative methods were used to summarize findings from the included studies and interpretative methods were used based on an extensive iterative-inductive analysis framework [34]. Relationships within tabulated themes were explored; for example, comparing professional attitudes and norms across different aspects of medication safety, different professions and studies. Themes were reviewed by all authors.

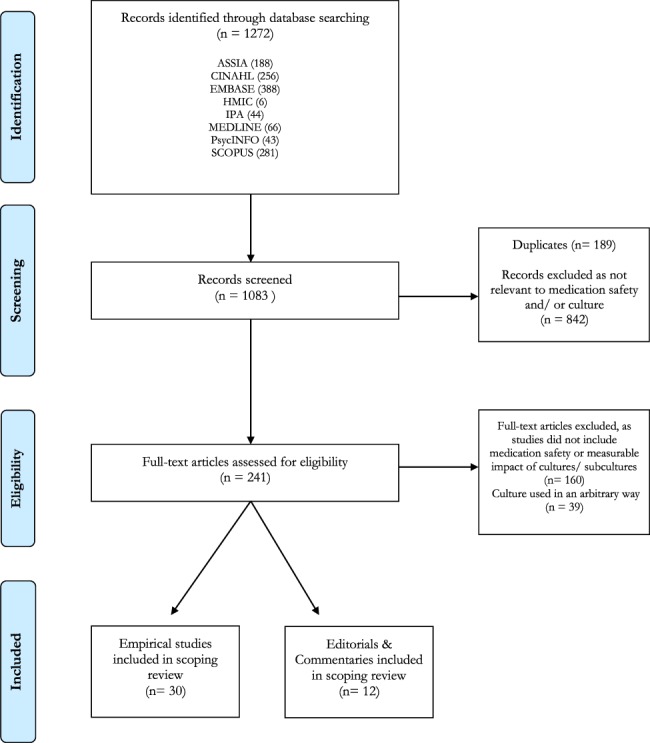

Results

A total of 42 articles were selected for review after removal and duplicates and screening (Fig. 1), with 30 empirical studies and 12 pieces of grey literature. These articles are summarized in Table 3. Study characteristics can be seen in Tables 4–6. In studies looking at professions, the main focus was on solely nursing staff (n = 19), nurses, doctors and pharmacists (n = 10) and nurses and doctors (n = 6). Of the 30 empirical studies, 17 utilized quantitative methods, 10 qualitative methods and 3 mixed-methods.

Figure 1.

PRISMA(92) flow chart diagram of the scoping review process.

Table 3.

List of all included studies in review

| Article | Country | Year | Medication safety focus | Role of culture |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aarts [70] | The Netherlands | 2013 | Prescribing | Prescribing is a social act which shows the authority of the doctor in being able to ‘solve’ the patient’s problem. Electronic prescribing challenges embedded social norms attached to professions. The author argues that interventions should take into account cultural nuances that may exist |

| Aboshaiqah [83] | Saudi Arabia | 2013 | Medication error reporting | Administrative response to error and fear was an important barrier to nurses in reporting medication administration errors. Staff believed there was too much emphasis placed upon errors as a marker of quality of care and errors weren’t looked upon from the perspective of the system-only the individual |

| Alqubaisi et al. [44] | United Arab Emirates | 2016 | Medication error reporting | Nurses and pharmacists’ likelihood to report errors was impacted by the perceived professional hierarchy and ‘power’ of doctors-with doctors wanting less formal platforms for errors to be discussed (i.e. a conversation). Pharmacists, doctors and nurses elicited a fear of reporting-worrying it would impact their reputation or result in litigation. Nurses elicited a greater fear of litigation |

| Andersen [84] | Denmark | 2001 | Prescribing | Professional culture as a barrier to collaborative working. The authors report that nurses and doctors had strong professional identities and when implementing a new drugs record system, the intervention challenged established roles of nurses and doctors. The authors characterized nurses by collectivism, whereas the doctors were more competitive and individualistic |

| Boyle et al. [55] | Canada | 2011 | Medication error reporting | Supportive organizational culture, defined as ‘enthusiasm about improved reporting … creating a safe reporting environment,’ was found to be an significant variable in ensuring reporting of medication safety incidents |

| Chiang et al. [85] | Taiwan | 2010 | Medication error reporting | Failure to report was strongly influenced by nurses’ experience of making medication administration errors. Barriers to reporting included fear, perception of nursing quality and perception of nursing professional development |

| Debono et al. [69] | Australia | 2013 | Compliance with protocols | There are deviations of medication safety practices across areas—for example, not checking identification bands in long term wards, as the staff are familiar with the patients |

| Dickinson et al. [68] | USA | 2012 | Safe Medicines Administration | Norms are passed on within professions and role modelling of these norms by professionals ensure they become common practice |

| Dolansky et al. [60] | USA | 2013 | Reducing medication errors/investigation into errors | Case study of a medication error. Looking at the error from an organizational and professional lens, the study identified that the unit level’s response to an error is important, as well as communication between nurses and senior staff |

| Federwisch et al. [86] | USA | 2014 | Interventions | This study, an evaluation of an intervention to reduce interruptions to nurses during their drug rounds, found that nurses elicited that the signs (to not interrupt) were not respected. The vests worn by nurses were poorly received, with the authors postulating that the ‘vests signify unavailability which didn’t mesh well with a nursing culture that values flexibility and availability’ |

| Flanders and Clark [49] | USA | 2010 | Reducing medication errors/investigation into errors | Interventions aiming to limit interruptions to nurses during their drug rounds were fraught with difficulties because they implicitly challenged a nursing culture that pride themselves on availability and ability to multitask |

| Furmedge and Burrage [71] | UK | 2012 | Prescribing | Doctors arrived with limited knowledge of prescribing, however the authors argue that due to exposure to other colleagues within the profession, bad habits flourish which become difficult to ‘stamp out’ |

| Gill et al. [66] | Australia | 2012 | Compliance with protocols | Medication related practices became routine practices by ‘the nursing gaze’—a term coined by the authors which was defined as a ‘surveillance strategy by which nurses examined each other’s activities.’ ‘Ward culture’ was important, where some areas were more diligent than others in complying with protocols. Junior nurses were discouraged from following protocols (e.g. checking ID bands) by their senior colleagues-with the authors concluding negative role modelling and active discouragement were key influences on practices being reinforced |

| Gimenes et al. [57] | Brazil | 2016 | Safe Medicines Administration | Trust and cooperation among staff in an intensive care unit influenced medication safety culture. On a wider organizational level, the trust had a zero tolerance to errors and the frequent firing strengthened a culture of punishment. There was a focus on the person making the error, rather than improving processes. On a professional level, nurses believed pharmacists didn’t understand their day-to-day difficulties and there was a lack of communication |

| Hammoudi et al. [58] | Saudi Arabia | 2018 | Medication error reporting | Medication errors were influenced by the communication process between nurses and doctors, and the reporting of these errors was influenced by nurses’ fear of reporting, and the administration response to the error—for example, a nurse being individually blamed for the error |

| Hartnell et al. [43] | Canada | 2012 | Medication error reporting | Professionals reported a fear that reporting an error would threaten their professional identity by appearing incompetent to colleagues. Organizational barriers, or ‘how things are done around here,’ resulted in an ineffective reporting system and no learning from errors |

| Hawkins et al. [63] | USA | 2017 | Systems evaluation | Pharmacists were an important ‘stop-gap’ between errors getting to the patient, however the authors reported that the pharmacists did not formally supporting the reporting of these errors. There were examples of interventions taken by the pharmacist to correct doctors’ errors but there were no examples of pharmacists informing the doctors of their error. This lead the authors to conclude that inter-professional hierarchies remain an issue within medication safety |

| Hemphill [56] | USA | 2015 | Interventions | The authors argue that while organizations may feel punitive responses to error are justified; it will not serve to be useful in understanding the processes and systems that contributed to the error. They claim that leadership is the ‘driving force’ behind a safety culture, where frontline staff will only believe safety is important if their senior leaders encourage this |

| Hong and Li [38] | China | 2017 | Medication error reporting | Safety climate was the most important domain impacting a unit’s safety culture. Nurses considered the unit’s overall safety culture as influential in reporting adverse events—where a flexible organizational culture promoted patient safety and reporting of adverse events due to instilling trust among the nurses |

| Hughes and Ortiz [52] | USA | 2005 | Reducing medication errors/investigation into errors | Clinicians have preconceptions about patient safety more generally which impacts their likelihood to engage in reporting and learning from errors. The authors comment that common feelings attached to reporting error are fear of being blamed, fear of litigation or serious impacts to the individual’s career |

| Hughes et al. [87] | UK | 2007 | Prescribing | Patterns of prescribing represent the visible artefacts of organization members but greater focus should be placed upon how these cultural patterns are created, communicated and maintained |

| Jacobs et al. [46] | Manchester, UK | 2011 | Medicines reconciliation/advanced pharmacy | There is a range of evidence describing aspects of organizational culture and its impact upon community pharmacy without explicitly defining this as organizational culture in this context. Authors identified five dimensions of organizational culture: the professional-business role dichotomy; workload, management style, social support and autonomy; professional culture; attitudes to change and innovation; and entrepreneurial orientation |

| Janmano et al. [62] | Thailand | 2018 | Medication error reporting | In a social network analysis of reporting medication errors, pharmacists were found to be central in the network of consultation on medication and were discussed to be ‘bridges’ between nurses and doctors |

| Kagan and Barnoy [35] | Israel | 2013 | Medication error reporting | The correlation between patient safety culture at an organizational level and error reporting rate was significant, leaving the authors to deduce that the ‘better’ the organizational culture for patient safety was, the more likely nurses were to report errors |

| Kavanagh [50] | Republic of Ireland | 2017 | Reducing medication errors/investigation into errors | Discusses the role of medication incidents on nurses-identifying that they feel guilt or too heavily bear the blame, leaving them to feel incompetent. There is a need for a blame free culture which can empower staff to report, with the authors arguing that this will have a significant impact on whether or not errors are noticed and reported |

| Kaissi et al. [64] | USA | 2007 | Reducing medication errors/investigation into errors | The use of practice guidelines was associated with reduced medication error rates in groups with a more ‘collegial’ culture-defined as a culture fostering coordination within doctors and between nurses and doctors |

| Kelly et al. [67] | USA | 2016 | Interventions | This article discusses the role of workarounds which can serve as a barrier to successful implementation of an intervention. These solutions, implemented by the nurses as solutions to their everyday issues, were found to be deeply ingrained into practice-so instead of being seen as workarounds or hazards to the staff, they are common and accepted practice |

| Liu et al. [61] | Australia | 2011 | Medication error reporting | Communication is influenced by hierarchy that exists in organizations and relates generally to vertical hierarchies, resulting in role conflict and struggles with interpersonal power and relationships |

| McBride-Henry and Foureur [88] | New Zealand | 2006 | Safe Medicines Administration | Staff nurses did not feel that senior leaders in their hospitals listened to their concerns and at times, nurses believed that they felt powerless to address the medication safety incidents they identified because it was beyond the scope of their position. Communication across the multi-disciplinary team was seen as important to nurses |

| Moody [48] | USA | 2006 | Medication error reporting | On the behavioural motivation scale, items involving worry, fear, anger and criticism relative to medication errors were scored highly by nurses. Nurses felt that the authority gradient in their organization hindered their ability to confidently engage and ask questions with someone of ‘higher’ authority. 2/3 of nurses described themselves as ‘prudent’ when dealing with authority and would only speak up if they deemed themselves to have ‘proper’ authority. Across different organizations, significant differences in nurses’ perceptions of their safety culture relative to different managers and supervisors |

| Ramsay et al. [22] | UK | 2014 | Compliance with protocols | Nurses were more engaged with medication score-card feedback than doctors, which identified contrasting approaches to improvement in the two professions. Nurses reported being more likely to be removed from their responsibilities if a drug error happened. Examples of ‘normalised deviance’ where errors were seen to be normal or unsurprising across areas and professions |

| Reid-Searl and Happell [59] | Australia | 2011 | Safe Medicines Administration | Participants of the study referred to the culture of the specific units and hospitals and claimed this had an important influence on the way they administered drugs and discussed the need to ‘fit in’ to the environment |

| Sahay et al. [53] | Australia | 2015 | Medication error reporting | Graduate nurses reported feeling reluctant to approach nursing colleagues for advice on medication administration. Graduate nurses experienced condescending language and felt nurses were impatient with their questions. Nurses also identified they felt blamed for medication errors that were made by doctors or other nurses |

| Salem et al. [51] | UK | 2013 | Medication error reporting | There was an organization-wide apathy to reporting as respondents elicited it was unlikely to respond with any meaningful feedback or change. Junior staff reported anxiety in challenging their more ‘superior’ colleagues. The authors identified that reporting errors was influenced by a feeling of protecting oneself and subsequent obligation. Respondents found that the response to an error by a nurse was more of an ‘open book,’ but when a doctor made a mistake it was ‘kept quiet’ with no learning of what happened as a result |

| Samsuri et al. [36] | Malaysia | 2015 | Medication error reporting | Pharmacists working in health clinics were 3.7 times more likely to have positive overall safety culture scores compared to pharmacists working in the hospitals. Reporting practices were impacted by the overall safety culture |

| Sarvadikar and Williams [45] | UK | 2009 | Medication error reporting | Nurses, doctors and pharmacists felt criticism and blame would follow if they reported an error. Nurses showed a greater fear of disciplinary action or even losing their jobs after an error compared to pharmacists and doctors. Nurses and pharmacists indicated they would report all errors irrespective of the patient outcome, whereas doctors were more likely to report the error if the patient’s condition worsened |

| Smetzer et al. [54] | USA | 2003 | Safe Medicines Administration | Hospitals that elicited a non-punitive approach to error reductions were more likely to be better at detecting, reporting and analysing errors. There were strong correlations between a strong supportive culture and the reporting of errors |

| Smits et al. [89] | The Netherlands | 2012 | Reducing medication errors/investigation into errors | In the same hospital, surgical and medical units were more likely to report errors compared to the emergency department. Non-punitive response to error, hospital management support and willingness to report were influenced by the overall safety culture in the units |

| Tricarico et al. [90] | Italy | 2017 | Medication error reporting | Incident reporting rates by profession were analysed prospectively and saw an increase of doctors engaging with reporting. The authors state that doctors started with initial scepticism before increasing involvement and reporting practices and that the incident reporting system was nor fully accepted by their own professional improvement ideologies |

| Turner et al. [23] | UK | 2013 | Medicines reconciliation/advanced pharmacy | Attitudes towards medication safety varied across professions-with pharmacists believing it was central to their hospital socialization. Attitudes were shaped by the social norms practices within the specialities and therefore awareness of medication safety practices differed across different specialties. Nurses elicited a higher likelihood to report errors due to their fear of litigation |

| Vogus and Sutcliffe [91] | USA | 2001 | Medication error reporting | Units within hospitals exhibit significant variation in safety organization and perceived trust in leadership. Unit-level leaders are able to enhance the effects of safety organizing on patient safety by fostering trust, thus making clinicians feel safe to discuss near-misses and errors |

| Wakefield et al. [37] | USA | 2011 | Medication error reporting | Explored role between four culture types, group-type culture, development-type culture, hierarchical-type culture and rational-type culture and reasons why medication administration errors were not reported. A hierarchical or rational-type culture was negatively associated with reporting of medication administration errors |

Table 4.

Included articles by culture focus

| Culture focus | Included in analysis (%) |

|---|---|

| Organizational culture | 11 (26) |

| Organizational culture and professional culture | 14 (44) |

| Professional culture | 17 (40) |

Table 6.

Included articles by country/region

| Country/region | Included in analysis (%) | Country/region | Included in analysis (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | 5 (11.9) | Republic of Ireland | 1 (2.38) |

| Brazil | 1 (2.38) | Saudi Arabia | 2 (4.76) |

| Canada | 2 (4.76) | Taiwan | 1 (2.38) |

| China | 1 (2.38) | Thailand | 1 (2.38) |

| Denmark | 1 (2.38) | The Netherlands | 2 (4.76) |

| Israel | 1 (2.38) | The UK | 7 (16.67) |

| Italy | 1 (2.38) | The USA | 13 (30.95) |

| Malaysia | 1 (2.38) | UAE | 1 (2.38) |

| New Zealand | 1 (2.38) |

Conceptualization of culture

We aimed to explore the way in which culture was conceptualized in medication safety, on both organizational and professional levels. Of the 241 full text articles assessed, 39 were excluded as they were judged to use the term ‘culture’ in an unfocused and arbitrary way. In some cases, articles cited improving culture as a means of improving medication safety but without defining or conceptualizing culture. Excluded articles also discussed improving culture as a mediator in achieving organizational or improvement aims, yet offered little on what this meant in practice.

In studies focusing on organizational culture, the majority of articles utilized a tool to measure organizational culture, for example, the Stanford/Patient Safety Centre of Inquiry culture survey [35], the Safety Attitudes Questionnaire [36] and the Culture Inventory [37]. At times, unit level culture was used interchangeably with safety culture, a just and a blame-free culture. In the studies focusing on professional cultures, only one utilized a tool (the Patient Safety Culture Assessment Scale [38]), with the remaining articles referring to shared values, attitudes, norms, behaviours or views among and within professions, which matched our definition of professional culture. ‘Professional culture’ as a phrase was used less often in the articles than ‘organizational culture.’

Table 5.

Included articles by medication safety focus

| Medication safety focus | Included in analysis (%) |

|---|---|

| Compliance with protocols | 3 (7.14) |

| Interventions | 3 (7.14) |

| Medication error reporting | 18 (42.86) |

| Medicines reconciliation/advanced pharmacy | 2 (4.76) |

| Prescribing safety | 4 (9.52) |

| Reducing medication errors/investigation into errors | 6 (14.29) |

| Safe medication administration | 5 (11.9) |

| Systems evaluation | 1 (2.38) |

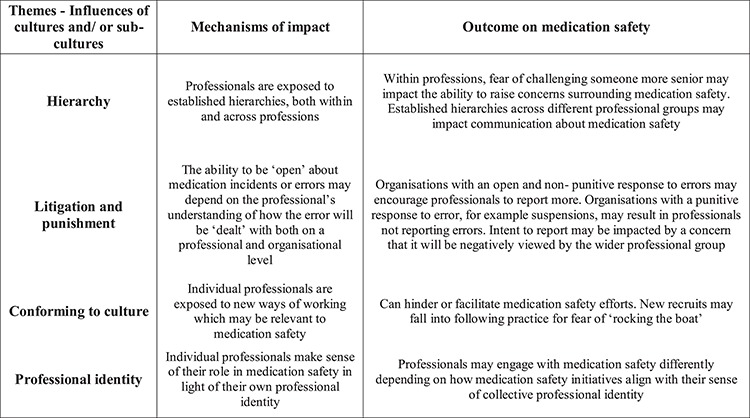

Themes

Four themes emerged from the data synthesis, describing both the direct and indirect impact of organizational and professional culture on medication safety practices. Three of the four themes were cross-cutting across professional and organizational levels, alluding to the difficulties in disentangling professional and organizational cultures, as individuals and communities may be a function of both their profession and their organizational setting. A visual depiction of these themes can be found in Fig. 2.

Figure 2.

Themes from the review.

Theme 1: professional identity

This theme focuses on the way professionals make sense of their role in medication safety relative to their professional identity. Professional identity is defined as ‘the various meanings attached to oneself by self and others’ [39] and it is an important cognitive mechanism impacting professionals’ attitudes, behaviour, values and beliefs in the work place [40–42]. For pharmacists, medication safety was inherent in their role and resulted in a belief that it was their place to ‘champion’ medication safety [23]. Nurses shared the view that medication safety was important and maintained through their professional role [43], which resulted in engagement with reporting structures [44], aligning with a profession already engaged in incident reporting. Doctors were less likely to see medication safety as part of their professional role relative to other clinical skills [23] and less likely to report medication errors as they believed nurses were more likely to do so for them [44]. Nurses and pharmacists were more likely to report an error irrespective of the level of patient harm, whereas doctors were more likely to report if patient outcomes worsened due to the error [45]. Fear of tainting their professional reputation by reporting an error was discussed by nurses, doctors and pharmacists [44, 46–50].

Theme 2: litigation and punishment

This theme relates to the professional and organizational response to medication errors. On a professional level, fear of litigation and punishment due to medication error was identified by nurses, pharmacists and doctors [23, 47, 48, 51, 52]. For nurses, this resulted in increased reporting of errors and compliance to documentation in order to protect themselves [23, 51]. Nurses believed they were more likely to be held accountable for errors compared with doctors [45, 48, 53]. Organizations fostering a non-punitive response to errors were said to result in better detection, reporting and analysing of medication errors [54–56]. Hospitals with a punitive response to error, cited as having a ‘blame culture,’ resulted in poor reporting and learning across the organization [47, 55, 57]. In one case, the ‘frequent firing’ of staff committing serious drug errors strengthened a culture of fear and punishment [57]. Professionals elicited a concern that medication safety reports were not used ‘correctly’ by their organization, for example, not to drive improvement but as a measure of the quality of nursing care [58].

Theme 3: hierarchy

The concept of professional hierarchy operated both within and across the three professions. Hierarchy within the nursing and medical profession negatively impacted nurses’ and doctors’ intention to report errors [37, 51, 59, 60]. Junior doctors saw their perceived lack of experience and knowledge as a barrier to seeking support or challenging senior colleagues, thus inhibiting them from reporting errors and near-misses [51]. Newly qualified nurses felt intimidated by senior nurses due to their grading or experience [60], and felt obliged to fall in line with existing, and at times unsafe, practices for fear of ‘rocking the boat’ [59]. On an inter-professional level, nurses and pharmacists argued that perceived importance or ‘power’ of doctors inhibited reporting doctors’ medication errors or near-misses [44, 48, 61]. One article identified that nurses saw themselves as ‘prudent’ when dealing with authority—only challenging another professional if they had the ‘proper authority’ [48], however what constituted ‘proper authority’ was not explored. Interruptions to nurses’ drug rounds were accepted based on hierarchical organizational relationships—for example, the nurse’s perceived ‘power’ of the person wanting their attention [49]. Pharmacists were considered central figures within medication safety, supporting positive interactions across the professional groups and acting as ‘bridges’ between professional groups [62]. However, one study reported that while pharmacists were an important ‘stop-gap’ between errors getting to the patient, doctors were not informed of their errors leaving the author to conclude inter-professional hierarchies were a barrier to learning from errors [63]. Areas with a more ‘collegial culture,’ defined by increased coordination and communication between physicians and nurses, were statistically more likely to engage in medication safety practice guidelines and report lower medications error rates [37, 64].

Theme 4: conforming to culture

This theme relates to the role of enculturation of individuals into medication safety practices. Enculturation refers to the process of an individual’s socialization into the accepted norms, practices, attitudes and values of the group [65]. New recruits discussed a pressure to conform to the expected and established norms in an area or within their professional group. The priority given to medication safety was influenced by social networks and the attitudes and practices within their professional group or organizational setting [63]. The enculturation of new recruits was well discussed within the nursing profession and could either serve to facilitate or hinder medication safety [53, 59, 66–68]. Some wards were cited as having a ‘better’ safety culture—facilitating the reporting of errors [35] and here were examples of medication safety practices (e.g. second checking intra-venous drugs) varying significantly across different wards within the same hospital [66, 69, 70]. Junior or inexperienced nurses felt pressured to ‘fit in’ with the established practices as their colleagues were impatient with the time it took them to complete a drug round, which in some cases resulted in the administration of drugs they knew to be incorrect [53, 60]. These embedded and established practices were communicated explicitly and implicitly to new members of nursing staff [66]. One study coined this implicit communication as the ‘nursing gaze,’ where medication-related practices became routine as nurses surveyed each other’s activities and practices [66]. Within medicine, newly qualified doctors started out with little knowledge of prescribing and picked up ‘bad habits’ as they were exposed to prevailing informal practices [71].

Discussion

We set out to identify how the concept of ‘culture’ has been used in the medication safety literature. 16% of the articles screened for inclusion used ‘culture’ in an arbitrary way—that is, used rhetorically without being critically explored. While the increased focus on ‘culture’ in health care has facilitated a better understanding of how health care organizations work, it has been argued at times that culture as a concept has been poorly conceptualized or used superficially as a panacea for improvement [72]. This inadequate conceptualization is not only due to culture being used in a remedial sense, but also due to the complex and conflicting schools of thought of what culture is and how it can be conceptualized in health care. Defining culture has well-established difficulties [73, 74], famously demonstrated by anthropologists Krober and Klukholm, who sought to review different concepts and definitions of culture and assembled 164 different definitions from this research [75].

What culture ‘is’ is also a well-established debate. Organizational culture has been studied in a dual way, as either a root metaphor or variable. Culture as variable identifies a positivist view where culture is something an organization has, where specific cultural aspects may be isolated or manipulated in light of organizational aims [73]. Culture as a root metaphor identifies culture as something the organization is and therefore not readily identifiable or separate to the organization. As culture is a function of the specific context and subtle social and historical processes in the organization [76, 77], it may offer less power for managerial control [78]. In the wider patient safety literature, the role of culture is presented in two different ways: as a ‘culprit’ for poor outcomes and also as a remedy for improving outcomes [5]. The arbitrary use of the term ‘culture’ in some of the reviewed articles alluded to this positivist and remedial view of culture as a variable, which can be manipulated or ‘improved,’ to achieve medication safety aims. There is a continuing rhetoric and normative desire within health care to move from a toxic or ineffective culture towards a positive, supportive and open culture. While this overarching aim is undeniably important, at times it results in research which incorporates this message, but with little understanding of the depth or sophistication of enquiry needed to support such a message.

We set out to explore the impact of professional and organizational culture on medication safety. Established aspects of professional organization, for example, a profession’s hierarchy, was identified as having an impact on medication safety practices. During this review, collective attitudes and norms held within professions and towards other professional groups (e.g. others´ perceived ‘power’) featured heavily in the papers included. As medication safety involves collaboration between nurses, doctors and pharmacists, comparing collective cultural views expressed by professionals with their actual daily practice would aid understanding of how power affects collaboration on medication safety (e.g. by triangulating interviews and observational evidence). This particular finding echoes a recent inquiry into the prescribing practices at Gosport War Memorial Hospital in England, where inappropriate and unsafe opioid prescribing by doctors went largely unchallenged by nurses and pharmacists [79]. The way professionals make sense of their role and others’ roles is important in understanding engagement with medication safety and subsequent initiatives. This corroborates a study of reporting practices among doctors, where they believed that ‘form filling’ and ‘paper work’ associated with reporting was more appropriate for professions suited to bureaucratic procedures and more amenable to managerial control—for example, nurses [24]. Finally, the role of enculturation meant that new recruits were socialized into accepted norms which, at times, resulted in unsafe practices. This illuminates the role of professional communities in passing on norms explicitly and implicitly which supports previous research identifying informal communication between processionals as a key model of learning within health care, with such models important in organizational learning [80].

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first review that has explored the role of organizational and professional cultures within medication safety. Individual articles included in this review focused on one aspect of medication safety or from the perspective of one professional group; and by synthesizing findings from different studies, the role of shared norms, attitudes and practices in professional groups upon medication safety can be better understood. De Bono has previously suggested that professional sub-cultures are ‘often stronger than other groupings within an organisation’ [19, 20] and this review helps to explore the role of professional cultures. If we see organizations, for example, hospitals, as being made up of different sub-cultures, then this review enables an understanding of why interventions must take these sub-cultures into account. This raises the importance of ensuring managers are engaged with understanding the nuances in collective views, values or ‘cultures’ that exist in professional groups and organizational settings and how these may inform, and influence, governance of medication safety.

Limitations

Due to aforementioned complexities, conducting a sensitive and precise search strategy was challenging. This review compared reports of ‘culture’ across different health care settings and as professional practice may vary significantly across countries and organizations, comparisons of professional cultures may be best served to be conducted in the same country and/or organization. This review has surfaced the intricate link between organizational and professional cultures and as these two concepts are not mutually exclusive, this added to the challenges in conducting a review on such a nebulous concept. Recent debates in scoping review methodology include arguments for discussing findings with relevant stakeholders, originally an optional step in Arksey and O’Malley’s framework, which would add insight by bringing actors’ experiences to bear on provisional findings [30]. This review did not include such feedback on the findings, and therefore this is a limitation. Finally, 45% of included articles focused solely on the nursing profession and therefore, future research should endeavour to study nurses, doctors and pharmacists within the same organizational setting (both wards and hospitals) to explore the role of sub-cultures upon medication safety practices.

Conclusion

Our scoping review provides a wider understanding of the importance and role of cultures in medication safety. Differences in perception of professional roles acted both as a barrier and facilitator to medication safety. Inter and intra-professional hierarchies influenced the communication within and across professional groups, with some cases professionals hesitant to question medication orders for fear of challenging their superiors. Implicit and explicit socialization into culturally accepted norms, both across an organization setting and a profession, was important in embedding medication safety practices. Medication safety is high on the current policy agenda and understanding the role of organizational and professional cultures allows for interventions and governance strategies to be shaped in light of the impact of these important concepts.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at INTQHC Journal online.

Funding

Health Foundation Improvement Science PhD Fellowship and supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care North Thames at Barts Health NHS Trust. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. YY is an NIHR Senior Investigator.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. World Health Organisation Medication Without Harm. WHO Global Patient Safety Challenge, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2. Smith J. Building a Safer NHS for Patients: Improving Medication Safety. Department of Health, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dean Franklin B, Tully MP. Introduction: Safety in Medication Use, 2015, 3–4.

- 4. Braithwaite J, Herkes J, Ludlow K et al. Association Between Organisational and Workplace Cultures, and Patient Outcomes: systematic Review, 2017,e017708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5. Mannion R, Davies H. Understanding Organisational Culture for Healthcare Quality Improvement, 2018,k4907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6. Francis R. Report of the mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation trust. Public Inquiry London: The Stationery Office; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kennedy I. The Report of the Public Inquiry into Children’s Heart Surgery at the Bristol Royal Infirmary 1984–1995—Learning from Bristol, 2001. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20090811143745/http:/www.bristol-inquiry.org.uk/final_report/the_report.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8. Schein EH. Organisational Culture and Leadership. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Peters T, Waterman R In: Ha R. (ed.). In search of Excellence. Sydney, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bloor G, Dawson P. Understanding professional culture in organizational context. Organ Stud 1994;15:275–95. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Scahill S, Harrison J, Carswell P, Babar Z-U-D. Organisational culture: an important concept for pharmacy practice research. Pharm World Sci 2009;31:517–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Phipps DL, Ashcroft DM. Psychosocial influences on safety climate: evidence from community pharmacies. BMJ Qual Saf 2011;20:1062–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yamaguchi S. Nursing culture of an operating theater in Italy. Nurs Health Sci 2004;6:261–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Van Ess Coeling H, Wilcox JR. Using organizational culture to facilitate the change process. ANNA J 1990;17:231–6discussion 41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jacobs E, Roodt G. Organisational Culture of Hospitals to Predict Turnover Intentions of Professional Nurses, 2008.

- 16. Martin J, Siehl C. Organizational culture and counterculture: an uneasy symbiosis. Organ Dyn 1983;12:52–64. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Danielsson M, Nilsen P, Rutberg H, Carlfjord S. The professional culture among physicians in Sweden: potential implications for patient safety. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18:543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rose RA. Organizations as multiple cultures: a rules theory analysis. Hum Relat 1988;41:139–70. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hall P. Interprofessional teamwork: professional cultures as barriers. J Interprof Care 2005;19:188–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. De Bono S, Heling G, Borg MA. Organizational culture and its implications for infection prevention and control in healthcare institutions. J Hosp Infect 2014;86:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. McDonald R, Waring J, Harrison S et al. Rules and guidelines in clinical practice: a qualitative study in operating theatres of doctors' and nurses' views. Qual Saf Health Care 2005;14:290–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ramsay AI, Turner S, Cavell G et al. Governing patient safety: lessons learned from a mixed methods evaluation of implementing a ward-level medication safety scorecard in two English NHS hospitals. BMJ Qual Saf 2014;23:136–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Turner S, Ramsay A, Fulop N. The role of professional communities in governing patient safety. J Health Organ Manag 2013;27:527–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Waring JJ. Beyond blame: cultural barriers to medical incident reporting. Soc Sci Med 2005;60:1927–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8:19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cooke M, Fisher J, Freeman K et al. Patient Safety in Ambulance Services: a Scoping Review, 2015. [PubMed]

- 27. Godfrey C, Harrison M, Lang A et al. Homecare Safety and Medication Management: a Scoping Review of the Quantitative and Qualitative Evidence, 2013, 357–71.

- 28. Viana De Lima Neto A, Da Fonseca Silva M, Gomes De Medeiros S et al. Patient safety culture in health organizations: scoping review. Int Arch Med 2017;10:2344. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci 2010;5:69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Daudt HML, van Mossel C, Scott SJ. Enhancing the scoping study methodology: a large, inter-professional team’s experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s framework. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Colquhoun HL, Levac D, O'Brien KK et al. Scoping reviews: time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. J Clin Epidemiol 2014;67:1291–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Noblit G, Hare R. Meta-Ethnography: Synthesizing Qualitative Studies. California, SAGE Publications, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dixon-Woods M, Agarwal S, Jones D et al. Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: a review of possible methods. J Health Serv Res Policy 2005;10:45–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. O'Reilly K. Ethnographic Methods. Routledge, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kagan I, Barnoy S. Organizational safety culture and medical error reporting by Israeli nurses. J Nurs Scholarsh 2013;45:273–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Samsuri SE, Pei Lin L, Fahrni ML. Safety culture perceptions of pharmacists in Malaysian hospitals and health clinics: a multicentre assessment using the safety attitudes questionnaire. BMJ Open 2015;5:e008889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wakefield B, Blegen MA, Uden-Holman T et al. Organizational culture, continuous quality improvement, and medication administration error reporting. Am J Med Qual 2001;16:128–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hong S, Li Q. The Reasons for Chinese Nursing Staff to Report Adverse Events: a Questionnaire Survey, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39. Gecas V, Burke P. Self and identity In: Cook K, Fine GA, House J (eds.). Sociological Perspectives on Social Psychology. Needham Heights, MA, Allyn and Bacon, 1995, 336–8. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Caza B, Creary S. School of Hotel Administration, The Construction of Professional Identity, 2016.

- 41. Ibarra H. Provisional selves: experimenting with image and identity in professional adaptation. Adm Sci Q 1999;44:764–91. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Schein EH. Career Dynamics: Matching Individual and Organizational Needs. Addison Wesley, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hartnell N, MacKinnon N, Sketris I, Fleming M. Identifying, understanding and overcoming barriers to medication error reporting in hospitals: a focus group study. BMJ Qual Saf 2012;21:361–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Alqubaisi M, Tonna A, Strath A, Stewart D. Exploring behavioural determinants relating to health professional reporting of medication errors: a qualitative study using the theoretical domains framework. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2016;72:887–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sarvadikar A, Prescott G, Williams D. Attitudes to reporting medication error among differing healthcare professionals. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2010;66:843–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Jacobs S, Ashcroft D, Hassell K. Culture in community pharmacy organisations: what can we glean from the literature? J Health Organ Manag 2011;25:420–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mohammad A, Aljasser I, Sasidhar B. Barriers to reporting medication administration errors among nurses in an accredited Hospital in Saudi Arabia. BJEMT 2016;11:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Moody RF, Pesut DJ, Harrington CF. Creating safety culture on nursing units: human performance and organizational system factors that make a difference. J Patient Saf 2006;2:198–206. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Flanders S, Legal CA. Ethical: interruptions and medication errors clinical nurse specialist. J Adv Nurs 2010;31:281–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kavanagh C. Medication governance: preventing errors and promoting patient safety. Br J Nurs 2017;26:159–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Salem A, Jones C, Elkharam WM. Attitudes to causes of failure to report service errors. Br J Healthc Manag 2013;19:75–84. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hughes RG, Ortiz E. Medication errors: why they happen, and how they can be prevented. AJN 2005;105:14–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sahay A, Hutchinson M, East L. Exploring the influence of workplace supports and relationships on safe medication practice: a pilot study of Australian graduate nurses. Nurse Educ Today 2015;35:e21–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Smetzer JL, Vaida AJ, Cohen MR et al. Findings from the ISMP medication safety self-assessment for hospitals. Jt Comm J Qual Saf 2003;29:586–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Boyle TA, Mahaffey T, Mackinnon NJ et al. Determinants of medication incident reporting, recovery, and learning in community pharmacies: a conceptual model. RSAP 2011;7:93–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Hemphill RR. Medications and the culture of safety: conference title: at the precipice of quality health care: the role of the toxicologist in enhancing patient and medication safety venue ACMT pre-meeting symposium, 2014 North American congress of clinical toxicology, New Orleans, LA. J Med Toxicol 2015;11:253–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Gimenes FRE, Torrieri MCGR, Gabriel CS et al. Applying an ecological restoration approach to study patient safety culture in an intensive care unit. J Clin Nurs 2016;25:1073–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hammoudi BM, Ismaile S, Abu Yahya O. Factors associated with medication administration errors and why nurses fail to report them. Scand J Caring Sci 2018;32:1038–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Reid-Searl K, Happell B. Factors influencing the supervision of nursing students administering medication: the registered nurse perspective. Collegian 2011;18:139–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Dolansky MA, Druschel K, Helba M, Courtney K. Nursing student medication errors: a case study using root cause analysis. J Prof Nurs 2013;29:102–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Liu W, Manias E, Gerdtz M. Understanding medication safety in healthcare settings: a critical review of conceptual models. Nurs Inq 2011;18:290–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Janmano P, Chaichanawirote U, Kongkaew C. Analysis of medication consultation networks and reporting medication errors: a mixed methods study. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18:221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hawkins SF, Nickman NA, Morse JM. The paradox of safety in medication management. Qual Health Res 2017;27:1910–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Kaissi A, Kralewski J, Dowd B, Heaton A. The effect of the fit between organizational culture and structure on medication errors in medical group practices. Health Care Manag Rev 2007;32:12–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Herskovits MJ. Man and his Works; the Science of Cultural Anthropology Oxford. Alfred A. Knopf, England, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Gill F, Corkish V, Robertson J et al. An exploration of pediatric nurses' compliance with a medication checking and administration protocol. J Spec Pediatr Nurs 2012;17:136–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Kelly K, Harrington L, Matos P et al. Creating a culture of safety around Bar-code medication administration: an evidence-based evaluation framework. J Nurs Adm 2016;46:30–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Dickinson CJ, Wagner DS, Shaw BE et al. A systematic approach to improving medication safety in a pediatric intensive care unit. Crit Care Nurs Q 2012;35:15–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Debono DS, Greenfield D, Travaglia JF et al. Nurses’ workarounds in acute healthcare settings: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13:175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Aarts J. The social act of electronic medication prescribing. Stud Health Technol Inform 2013;183:327–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Furmedge DS, Burrage DR. Hospital prescribing: it's all about the culture. Br J Hosp Med 2012;73:304–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Allen D, Braithwaite J, Sandall J, Waring J. Towards a sociology of healthcare safety and quality. Sociol Health Illn 2016;38:181–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Smircich L. Concepts of culture and organizational analysis. Adm Sci Q 1983;28:339–58. [Google Scholar]

- 74. MacLachlan M. Culture and Health: A Critical Perspective Towards Global Health. WIley, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 75. Kroeber A, Kluckhohn C. Culture: A Critical Review of Concepts and Definitions. Vintage Books, 1952. [Google Scholar]

- 76. Kaufman G, McCaughan D. The effect of organisational culture on patient safety. Nurs Stand 2013;27:50–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Meyerson D, Martin J. Cultural change: an integration of three different views. J Manag Stud 1987;24:623–47. [Google Scholar]

- 78. Davies HTO, Nutley SM, Mannion R. Organisational culture and quality of health care. Qual Health Care 2000;9:111–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Jones J. Gosport War Memorial Hospital: The Report of the Gosport Independent Panel, 2018.

- 80. Waring JJ, Bishop S. "water cooler" learning: knowledge sharing at the clinical "backstage" and its contribution to patient safety. J Health Organ Manag 2010;24:325–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Beales J, Walji R, Papoushek C, Austin Z. Exploring professional culture in the context of family health team interprofessional collaboration. HIP 2011;1:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 82. Helmreich RM. A. Culture at Work in Aviation and Medicine. Routledge, National, Organizational and Professional Influences, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 83. Aboshaiqah AE. Barriers in reporting medication administration errors as perceived by nurses in Saudi Arabia. Middle-East J Sci Res 2013;17:130–6. [Google Scholar]

- 84. Andersen SE. Implementing a new drug record system: a qualitative study of difficulties perceived by physicians and nurses. Qual Saf Health Care 2002;11:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Chiang HY, Lin SY, Hsu SC, Ma SC. Factors determining hospital nurses' failures in reporting medication errors in Taiwan. Nurs Outlook 2010;58:17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Federwisch M, Ramos H, Adams SC. The sterile cockpit: an effective approach to reducing medication errors? Am J Nurs 2014;114:47–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Hughes CM, Lapane K, Watson MC, Davies HT. Does organisational culture influence prescribing in care homes for older people? A new direction for research. Drugs Aging 2007;24:81–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. McBride-Henry K, Foureur M. Organisational culture, medication administration and the role of nurses. Prac Dev Health Car 2006;5:208–22. [Google Scholar]

- 89. Smits M, Wagner C, Spreeuwenberg P et al. The role of patient safety culture in the causation of unintended events in hospitals. J Clin Nurs 2012;21:3392–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Tricarico P, Castriotta L, Battistella C et al. Professional attitudes toward incident reporting: can we measure and compare improvements in patient safety culture? Int J Qual Health Care 2017;29:243–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Vogus TJ, Sutcliffe KM. The safety organizing scale: development and validation of a behavioral measure of safety culture in hospital nursing units. Med Care 2007;45:46–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009;339:b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.