Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this paper is to show that 2009 H1N1 “swine” influenza pandemic vaccination policies deviated from predictions established in the theory of political survival, and to propose that pandemic response deviated because it was ruled by bureaucratized experts rather than by elected politicians.

Design/methodology/approach

Focussing on the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, the paper employs descriptive statistical analysis of vaccination policies in nine western democracies. To probe the plausibility of the novel explanation, it uses quantitative and qualitative content analyses of media attention and coverage in two deviant cases, the USA and Denmark.

Findings

Theories linking political survival to disaster responses find little empirical support in the substantial cross-country variations of vaccination responses during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic. Rather than following a political logic, the case studies of media coverage in the USA and Denmark demonstrate that the response was bureaucratized in the public health agencies (CDC and DMHA, respectively). Hence, while natural disaster responses appear to follow a political logic, the response to pandemics appears to be more strongly instituted in the hands of bureaucratic experts.

Research limitations/implications

There is an added value of encompassing bureaucratic dynamics in political theories of disaster response; bureaucratized expertise proved to constitute a strong plausible explanation of the 2009 pandemic vaccination response.

Practical implications

Pandemic preparedness and response depends critically on understanding the lessons of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic; a key lesson supported by this paper is that expert-based agencies rather than political leaders are the pivotal actors.

Originality/value

This paper is the first to pinpoint the limitations of political survival theories of disaster responses with respect to the 2009 pandemic. Further, it is among the few to analyze the causes of variations in cross-country pandemic vaccination policies during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic.

Keywords: Aftercare, Disasters, Emergency response, Manmade disaster

Introduction

The theory of political survival has proved adept at explaining the behavior of both voters and governments in the wake of disasters. Empirical evidence overwhelmingly suggests that voters are retrospective and electorally punish governments for inadequate disaster responses. Risk-averse governments, aware of this, pursue visible and proactive disaster policies – in particular in competitive political settings and close to elections.

However, the great variation in vaccination rates across several western democracies following the 2009 pandemic runs counter to this prediction of political behavior. This paper addresses why the theory of political survival appears to have limited predictive power with respect to government behavior in the case of the 2009 pandemic.

The paper's thesis is that pandemic responses are led by national public health agencies (i.e. guided by expertise) rather than government executives (i.e. guided by principles of political survival). This is important because the source of leadership has critical implications for pandemic vaccination policies. In contrast to other disasters, where the logic of political survival usually incites executives to choose a politically precautionary response strategy, public health agencies follow their expert judgments and practice in opting for pandemic responses that could either follow a precautionary or a proportional strategy. Hence, national pandemic responses such as vaccine purchases and distribution become highly divergent, depending upon which strategy health authorities use.

To identify the source of leadership, the paper assesses expectations of an expertise-based approach to pandemic response with expectations of an approach based on political survival. This is accomplished using qualitative and quantitative analyses of the USA and Danish responses to the 2009 pandemic. The paper supports that, counter to dominant expectations, pandemic responses in mature democracies are led by expertise rather than for political survival.

The political survival logical of government responses to disasters

Political theory of disaster management generally hypothesizes that democratic governments will go to great lengths to help victims of disasters (Gasper and Reeves, 2011a, b; Morrow et al., 2008; Boin et al., 2008, 2005; Diamond, 2008; Mesquita et al., 2003; Sen, 1999, 2009). Drawing on rational choice theory, the basic assumption is that governments are interested in maximizing their time in office, which has famously been coined the logic of political survival (Morrow et al., 2008; Mesquita et al., 2003).

The support of the electorate is the primary concern for governments in democracies due to the inherent opportunity for citizens to oust incumbent governments at the subsequent election. The electorates tend to be retrospective when casting their votes and they might therefore punish governments that have not appeared to do their utmost to mitigate the adverse consequences of disasters in the preceding election period (Downs, 1957; Key, 1966; Fiorina, 1981). Government responsiveness in times of crisis is thus not necessarily linked to benevolence but to the fact that governments – fighting for survival (re-election) – will go to great lengths to avoid a humanitarian catastrophe. A free and active media improves conditions for retrospection by performing two basic functions: one as a mediator of information and one as a watchdog scrutinizing the government's disaster management (Sen, 1999; Besley and Burgess, 2002). The existence of vibrant opposition parties is also important because they present voters with a credible ruling alternative; they might even be able to overturn the government directly though parliamentary procedures (a vote of no-confidence, for instance); and they will generally be highly critical of the government's handling of the disaster. Hence, the opposition, the electorate and the media form a trinity responsible for the political dynamic that spurs the government to respond to disasters (Diamond, 2008; Boin et al., 2005).

There is ample empirical evidence supporting the two basic assumptions underlying the logic of political survival in response to disasters: first, studies overwhelmingly confirm that voters are retrospective and punish incumbent government for deficient responses to natural hazards (Cole et al., 2012; Healy and Malhotra, 2009, 2010; Achen and Bartels, 2004); and second, studies also suggest that incumbent governments are well aware of this and that they adjust their disaster responses accordingly (Bechtel and Hainmueller, 2011; Healy and Malhotra, 2009; Reeves, 2011; Gasper and Reeves, 2011a, b).

The logic of political survival applied to the 2009 pandemic

The theory of political survival leads to three specific expectations about government response policies to influenza pandemic disasters.

One is that, all else being equal, mature democracies will respond to influenza pandemics such as the novel “swine flu” in 2009 with vaccination policies that are fairly uniform and precautionary. The costs of pursuing a precautionary strategy of purchasing and distributing enough vaccines for all citizens are miniscule compared to the political costs of inadequate protection in case of a full-blown epidemic. If the disease turns out to be serious, the expected fallout in subsequent elections is likely to be far worse than the fallout over having spent too much on vaccines against a mild disease.

A second expectation is that the response intensity will correlate with the electoral cycle of the individual countries. The importance of election cycles in retrospective voting behavior is well established, and the timing of the disaster has been shown to have electoral consequences. Imminent elections prompt government to implement more comprehensive responses, while longer periods to the next election reduce the electoral impact (Cole et al., 2012; Bechtel and Hainmueller, 2011; Lenz, 2010).

A third expectation is that, if pluralistic competitiveness and participation vary between countries, then response intensity will vary with these factors. A high level of electoral competition spurs more disaster declarations and emergency aid allocations to sway voters after controlling for the actual impact of the natural hazards (Reeves, 2011; Gasper and Reeves, 2011a, b). Variations in pluralistic competitiveness and participation should thus be correlated with variations in the pandemic responses.

In order to assess these three hypotheses we have collected data on vaccination responses to the 2009 H1N1 pandemic across nine mature western democracies from which data were available. The comparative approach is based on a most-similar case design where different crisis responses take place in otherwise similar socio-political contexts (Przeworski and Teune, 1970; Landmann, 2008). The countries have been purposely selected to constitute a group of critical cases (Eckstein, 1975; George and Bennett, 2005) that have strategic importance: if the political theory of survival fails to predict government responses under the most optimal of conditions (mature and rich democracies), then the same is likely to also hold true in countries with less favorable conditions where centralism, patronage, corruption and red tape are prevalent. In these countries politicians could be capable of both ignoring their popularity among voters as well as any advice from the independent (external or internal) expert agencies. The data on vaccine purchases and coverage (uptake) are presented in Table I.

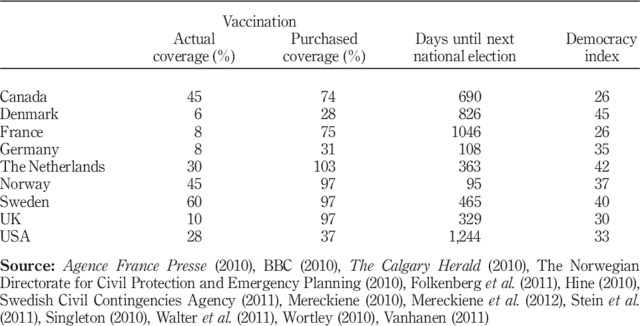

Table I.

Cross-country table of 2009 vaccination responses, election proximity and electoral competition

The first two columns in Table I can be used to assess the first prediction. The table reveals that there were huge variations in both purchased vaccination coverage (government orders of vaccine courses) and actual coverage (uptake by the population of vaccination). Some countries, such as the UK, Sweden, the Netherlands and Norway, pursued the precautionary policy predicted by the political survival logic: the governments purchased vaccines to cover the entire electorate. But others, such as the USA, Germany and Denmark, pursued something very much at odds – none came close to having vaccine courses available for all residents. Hence, the first prediction of extensive and uniform vaccination policies across all countries does not hold for the 2009 pandemic.

The second prediction can be evaluated by calculating the number of days to the next election from the day the WHO declared a pandemic on June 11, 2009 (column 3). The table reveals no pattern whatsoever between the two indices of vaccination responses and the number of days to the next election. This is supported statistically with an insignificant correlation-coefficient (Pearson's) of −0.41 between days to the next election and purchased vaccine coverage.

Column 4 addresses the third prediction by relating vaccination coverage to Vanhanen's democracy index (Vanhanen, 2011). Vanhanen's democracy index combines proxies for democratic competition (percentage of votes gained by the smaller parties in elections to proxy for the influence of smaller parties) and participation (percentage of the total population who voted in the election to proxy for voter involvement in the political process). The index is calculated for 2009 as a product of the two variables; a higher index implies greater competition and participation. The table reveals no systematic pattern between purchased vaccine coverage and the level of democratic competition and participation (insignificant correlation-coefficient of −0.089).

All in all, the theory of political survival, which has previously successfully accounted for government responses to disasters in democracies, does not have as much explanatory power when it comes to the behavior of governments during the 2009 pandemic.

The bureaucratized expert sources of disease outbreak response

The remainder of this paper probes the plausibility of a bureaucratic logic rather than a political logic to explain variations in national pandemic vaccination policies: the key differentiator between national pandemic responses is the judgment of public health experts, and of government agencies that employ them as bureaucrats, in national response policy making.

The outputs of national public health agencies are primarily developed by physicians with public health training and experience and by biomedical research scientists. These professions have established records as forces in health policy processes. Physicians’ organizations are notoriously powerful (Friedson, 1970; Immergut, 1992; Lewis, 2005). Government agencies that build on biomedical scientific expertise have considerable autonomous authority (Carpenter, 2001, 2010; Maor, 2011). As the loci of powerful professions, public health agencies are thus likely to enjoy substantial deference from government executives and departments. In their roles as experts of disease outbreak control, the agencies are likely to be called on to guide and publicly legitimate their governments’ pandemic responses. Each agency is thus likely in practice to decide within its own bureaucratic expert ranks what the “best” course of pandemic vaccination is for a whole nation. This autonomy includes being able to ignore vaccination policies in other countries.

These bureaucratized expert decision processes could produce two alternative strategies with highly divergent response implications (Baldwin, 2005; Hine, 2010). “Precautionary” response is associated with expert judgment that privileges sanitation by calling on the entire community to make sacrifices for the sake of vulnerable individuals. In contrast, “proportional” responses are associated with expert judgment that privileges isolation by calling on vulnerable individuals to protect themselves or infected individuals to stay clear of healthy ones. The causal mechanism is that expert agencies build on traditions and accepted practices for public health that vary by country. Hence, pandemic vaccination policies diverge significantly between countries because expert judgments differ significantly.

To test whether national public health agencies are indeed the locus of leadership and guidance in pandemic response, we have focussed on two deviant cases (Lijphart, 1971) (George and Bennett, 2005), Denmark and the USA, where both governments appear to have followed a proportional response with very limited vaccination coverage. According to our hypothesis this is because pandemic responses – unlike other disaster responses – are bureaucratized (and hence depoliticized) in powerful expert agencies. Quantitative and qualitative content analyses of media coverage in these two countries are used to assess public perceptions of responsibility and legitimacy in the pandemic response. They show that public attention overwhelmingly centered on the respective national public health agencies rather than on the national health departments or executives. This finding indicates that a bureaucratized expert logic rather than the political survival logic can dictate vaccination policies against pandemic influenza.

Expert agencies or elected politicians as leaders of the Danish pandemic response?

The Danish pandemic response constitutes an interesting outlier. Denmark is very similar to the two other Scandinavian countries, Sweden and Norway, along most socio-political dimensions (Esping-Andersen, 1990; Hall and Soskice, 2001). In terms of disaster responses, the countries’ emergency and evacuation policies to the 2004 Tsunami were also remarkably similar. Due to the many vacationing Scandinavians in Thailand, the Tsunami was the most deadly disaster due to a shock occurring in nature for more than a century for both Sweden (543 fatalities) and Denmark (46 fatalities) (EM-DAT, 2012). The disaster responses were all based on direct Prime Ministerial involvement, and the evacuation efforts were harmonized across the Scandinavian countries ( Politiken, 2005b). All three governments were faced with public criticism for responding too hesitantly, and the disaster responses were subsequently subject to much debate and independent inquiries ( Politiken, 2005a). With regard to pandemic responses, the institutional setups are also very similar: the countries have strong agencies of pandemic prevention and a great deal of flexibility with regard to the number of vaccines they can purchase ( Kristeligt Dagblad, 2009). During the 2009 pandemic, however, the Danish Government pursued a much more restrictive vaccination policy based on risk group coverage rather than the universal coverage pursued by the other Scandinavian countries (see Table I).

If indeed the pandemic response was bureaucratized, we would expect the media to primarily focus on the key health organization, the Danish Health and Medicines Authority (DHMA), and not the Danish Government. This expectation is confirmed by the data. To assess the hypothesis, a content analysis was performed of Danish media reports mentioning the terms “pandemic” or “H1N1” between May 1 and July 31, 2009. Taking advantage of the limited size of the media-landscape in Denmark, we were able to collect articles and features from all of the nine major Danish nationwide newspapers as well as from two major national news broadcasts, using the database Infomedia.

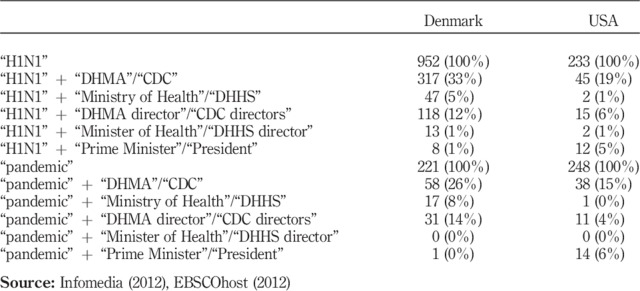

In the three months from the first novel swine flu infection of a Danish citizen (May 1-July 31, 2009), the nationwide media carried 952 features and articles mentioning the H1N1 virus (see Table II) (Infomedia, 2012). Pandemic response resides formally with the national government leaders and the DHMA only has an advisory role. But the mass media focussed almost exclusively on the DHMA. The agency was mentioned in 33 percent of the stories while the Ministry of Health was mentioned in merely 5 percent. The pattern is repeated for actors rather than institutions. The DHMA director, Else Smith, was mentioned in 12 percent of the H1N1 stories whereas her formal superior, the Minister of Health, was mentioned in just 1 percent of the stories. The Prime Minister, who leads the government, was barely mentioned (0.2 percent).

Table II.

Keyword searches of pandemic media coverage in Denmark and USA (May 1-July 31 2009)

Replacing the somewhat sterile medical term “H1N1” with the more politically explosive term “pandemic” does not alter the general pattern (Table II). Of the 221 pandemic stories in the period, the DHMA appeared in 26 percent while the Ministry of Health was mentioned in 8 percent. Else Smith was referenced in 14 percent of the stories while the Prime Minister and the Minister of Health were mentioned in only 0.5 percent. Hence, the quantitative data on media coverage and pressure strongly support the hypothesis of a decoupling in the general public's perception between the pandemic response and the government leadership.

Qualitative analysis of the media story contents in the same period provides additional evidence in support of the hypothesis. While the Danish pandemic response was indeed subject to some criticism and contrasted to the more comprehensive response in Sweden, the criticism was directed solely at the DHMA. Furthermore, the criticism originated neither from the opposition nor the media but was to a large extent reduced to technocratic disagreements between DHMA and health experts from other institutions such as the Swedish Institute for Communicable Disease Control ( Politiken, 2009; Berlingske, 2009a), a Danish University professor in health economics ( Politiken, 2009) and the chairman of the Danish association of local government doctors ( BT, 2009). Only one Member of Parliament publicly questioned the vaccination strategy of not providing universal coverage ( Politiken, 2009), and again the critique was targeted at the DHMA.

The attacks gained little significant traction. While voters’ general level of confidence in politicians was low (82 percent of poll respondents had no or very limited confidence in politicians; YouGov, 2009), DHMA enjoyed widespread public approval. A national survey at the end of July 2009 found that 86 percent of respondents approved of how the pandemic was being handled by the DHMA ( Berlingske, 2009b). Remarkably, the public's approval of the government's or individual ministers’ handling of the pandemic was not even polled. The public accepted and even endorsed that pandemic response was located at the agency rather than among government leaders.

The Danish case reveals how the government to a very great extent was insulated from the usual public scrutiny and accountability during the 2009 pandemic response. The health bureaucracy acted as a lightning rod for criticism, and the critique was mainly technical. The key dynamics of the logic of political survival appear to have been disabled in Denmark, allowing for proportional pandemic responses and greater cross-country variations.

Expert agencies or elected politicians as leaders of the US pandemic response?

Leadership of pandemic response in the USA resembles the Danish. US healthcare providers and the general public look to the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta rather than to the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) or to the Presidency for guidance and information on an emerging disease. Since its successful handling of polio using mass vaccination in the 1950s, the CDC has been the center of epidemic (and pandemic) response (Etheridge, 1992). To an extent, the executive branch has been particularly discredited as a leader of responses to epidemic influenza due to past mismanagement (Neustadt and Fineberg, 1978). Hence, history suggests that public health emergencies are bureaucratized rather than politicized in the USA. As in Scandinavia, this stands in stark contrast to other disasters, such as the hurricane flooding of New Orleans in 2005 (Katrina), where peak-level, executive (presidential and/or departmental) leadership has been the focus for public guidance and attention (Gerber and Cohen, 2008; Preston, 2008).

Given our expectations about the importance of the national public health agency in setting H1N1 vaccination policies in 2009 and the historical record, the pattern identified in Denmark should also be found in the US media. To assess the hypothesis, a similar content analysis was conducted on articles mentioning the search terms “H1N1” or “pandemic” between May 1 and July 31, 2009 in the three major US nationwide daily newspapers, the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal and USA Today. The articles were collected and analyzed using systematic searches of the EBSCOhost databases of news articles and other publications.

All in all, 233 articles in the selection mentioned H1N1 in the title and/or the body (Table II). Of these, 45 (19 percent) referred to the CDC and just two (<1 percent) to the DHHS. In all, 15 articles (6 percent) mentioned Richard Besser or Thomas Frieden, the CDC Directors before and after June 2009, respectively. Just two mentioned Kathleen Sebelius, the DHHS Secretary. President Obama was mentioned in 12 (5 percent) of the articles.

In all, 246 articles in the selection mentioned the pandemic in the title and/or the body (Table II). Of these, 38 (15 percent) mentioned the CDC while just one mentioned the DHHS. In all, 11 articles (4 percent) mentioned Richard Besser or Thomas Frieden, while none mentioned Kathleen Sebelius. President Obama was mentioned in 14 articles (6 percent).

The quantitative content data thus indicate that the CDC was by far the most referenced public authority in the leading news media in the USA during the summer of 2009. Among individuals, the CDC directors were mentioned in similar numbers of articles to the president (more when H1N1 was mentioned, fewer when pandemic was mentioned). If mention of the president is treated as equivalent to mention of the executive branch, the CDC was mentioned three to four times more often.

Qualitatively, the selected US newspaper coverage of vaccination and other pandemic response policies treated pandemic response as mostly a medical technical issue. Vaccination-related articles tended to summarize interviews or press materials from the CDC and other specialized federal agencies, particularly the Food and Drug Administration ( New York Times, 2009b; Wall Street Journal, 2009a, b, c d). The texts focussed on the timelines for developing vaccines, the approval process, the likely timing of the pandemic waves, and risk group assignments. On rare occasions, the elected political level was mentioned, in particular in early May as pandemic response was being organized ( New York Times, 2009a). In relation to vaccines, the president, DHHS secretary and CDC director presented the federal government's vaccine purchasing program in a joint teleconference call on July 9, 2009 ( Wall Street Journal, 2009a). But even here, coverage focussed on information rather than critique. The media's substantive focus on pandemic response as a question of technical solutions rather than political priorities supports the quantitative picture: in the public perception, the pandemic response was clearly led by bureaucratized expertise.

Hence, in the H1N1 pandemic in 2009, the US public turned far more to the CDC than to any other public authority for guidance and leadership. This is consistent with the hypothesized importance of the public health agencies, rather than the national government or executive, as the locus of leadership in pandemic response.

Conclusion

The disaster literature implies that national leaders will take charge of pandemic response policies. Responses such as pandemic vaccination purchasing and distribution will then converge on the “precautionary” logic because it carries the lowest political risk. But this fails to explain why 2009 H1N1 pandemic vaccination varied greatly between countries and why national public health agencies rather than national executives were looked to by the Danish and US publics for response guidance and leadership.

The evidence instead supports the hypothesis that a key distinction between responses to pandemics and other natural hazards is the role of expertise, and particularly the government agencies constituted of epidemiological and medical experts. In pandemics, these expert agencies are in charge, with significant effects on policy. Bureaucratized national responses can diverge because public health expert judgments, and the professional practices and traditions that shape them, can vary between countries. Hence, factors other than those that keep top-level politicians in power can be drivers of disaster response. Indeed, the 2009 pandemic showed that expertise can be a source of real authority in public health disasters.

The power of bureaucratized expert public health agencies in pandemic response ensures that cutting-edge results of biomedical sciences and epidemiology have a good chance of dominating policy. Pandemics may thus be more likely than other hazards to be overcome with the best of our knowledge. However, such dominance creates a real risk to legitimacy in mature democracies. Since experts are elected by no one, the great interventions in society and individual lives that policies such as mass vaccination exemplify are not held to proper account.

A remaining question is whether the risks to democratic legitimacy from expert-led national pandemic responses are outweighed by the benefits of gaining policies that are legitimated by epidemiological and medical science. A preliminary hypothesis emerging from this paper's analysis is that the potential gain from expert-led responses may be greater in countries with weaker democratic institutions, ceteris paribus. Directly strengthening expert communities in countries with weak democratic institutions (e.g. through agency support and training) could boost the likelihood of a more scientific response to pandemics. This could be preferable to a political response void of well-functioning mechanisms for accountability to the populace. Further research could provide answers through case-specific, in-depth analyses and process tracing of the political and expert dynamics of specific disasters.

Acknowledgments

This paper was made possible by funding from the Danish Research Council (2009-2014) for the study of the politics of natural disasters and from the US National Science Foundation for study of global infectious disease response (Grant No. SES-0826995; 2008-2011). The authors wish to thank Ann Keller and Chris Ansell of the University of California, Berkeley, for their support and encouragement and the journal's anonymous reviewers for their insights and comments.

About the authors

Dr Erik Baekkeskov (PhD Political Science) researches public health emergency responses and reforms of government services in several European countries and the USA. Erik Baekkeskov is the corresponding author and can be contacted at: baekkesk@ruc.dk

Dr Olivier Rubin (PhD Political Science) has researched on the politics and social determinants of famine and natural disasters publishing the monograph “Democracy and Famine” (Routledge 2010) together with several peer-reviewed articles on famine, climate change and natural disasters.

References

- Achen, C. and Bartels, L. (2004), “Blind retrospection: electoral responses to drought, flu, and shark attacks”, presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, Boston, MA, available at: www.international.ucla.edu/media/files/PERG.Achen.pdf (accessed May 30, 2012).

- Agence France Presse (2010), “France joins Europe flu vaccine sell-off”, January 3, Accessed through Lexis-Nexis Academic, February 13, 2011.

- Baldwin, P. (2005), Disease and Democracy: The Industrialized World Faces AIDS, University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA. [Google Scholar]

- BBC (2010), “France sells off surplus swine flu vaccine”, January 3, available at: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/health/8438663.stm (accessed May 30, 2012).

- Bechtel, M. and Hainmueller, J. (2011), “How lasting is voter gratitude? An analysis of the short- and long-term electoral returns to beneficial policy”, American Journal of Political Science, Vol. 55 No. 4, pp. 851-867.

- Berlingske (2009a), “Sverige: dansk H1N1-strategi ok”, July 30, available at: www.b.dk/danmark/sverige-dansk-h1n1-strategi-ok (accessed May 30, 2012).

- Berlingske (2009b), “Danmark får vaccine nok”, July 31, p. 6, available at: www.b.dk/danmark/danmark-faar-vaccine-nok (accessed May 30, 2012).

- Besley, T. and Burgess, R. (2002), “The political economy of government responsiveness: theory and evidence from India”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 117 No. 4, pp. 1415-1451.

- Boin, A., Mcconnell, A. and Hart, P. (Eds), (2008), Governing after Crisis – the Politics of Investigation, Accountability and Learning, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- Boin, A., Hart, P., Stern, E. and Sundelius, B. (2005), The Politics of Crisis Management: Public Leadership Under Pressure, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- BT (2009), “Vacciner alle børn”, August 1, available at: http://apps.infomedia.dk/Ms3E/ShowArticle.aspx?outputFormat=Full&Duid=e19d9b39 (accessed May 30, 2012).

- (The) Calgary Herald (2010), “Canada will donate flu shots to UN agency; Excess supply of H1N1 doses will be used overseas”, January 28, p. A5, accessed through Lexis-Nexis Academic, February 13, 2011.

- Carpenter, D. (2001), The Forging of Bureaucratic Autonomy: Reputation, Networks, and Policy Innovation in Executive Agencies, 1862-1928, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter, D. (2010), Reputation and Power: Organizational Image and Pharmaceutical Regulation at the FDA, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, S., Healy, A. and Werker, E. (2012), “Do voters demand responsive governments? Evidence from Indian disaster relief”, Journal of Development Economics, Vol. 97 No. 2, pp. 167-181.

- Diamond, L. (2008), The Spirit of Democracy: The Struggle to Build Free Societies Throughout the World, Times Books, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Downs, A. (1957), An Economic Theory of Democracy, Harper and Row, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- EBSCOhost (2012), “all databases”, available at: http://web.ebscohost.com/ehost (accessed May 30, 2012).

- Eckstein, H. (1975), “Case study and theory in political science”, in Greenstein, I.F. and Polsby, N. (Eds), Handbook of Political Science, Addison-Wesley, Reading, pp. 79-137. [Google Scholar]

- EM-DAT (2012), “Emergency database”, available at: www.emdat.be/database (accessed May 30, 2012).

- Esping-Andersen, G. (1990), The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism, Polity Press, Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- Etheridge, E.W. (1992), Sentinel for Health: A History of the Centers for Disease Control, University of California Press, Berkeley, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Fiorina, M. (1981), Retrospective Voting in American National Elections, Yale University Press, Yale. [Google Scholar]

- Folkenberg, M., Callreus, T., Svanström, H., Valentiner-Branth, P. and Hviid, A. (2011), “Spontaneous reporting of adverse events following immunisation against pandemic influenza in Denmark, November 2009-March 2010”, Vaccine, Vol. 29 No. 6, pp. 1180-1184. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Friedson, E. (1970), Professional Dominance: the Social Structure of Medical Care, Atherton Press, Chicago, IL. [Google Scholar]

- Gasper, J. and Reeves, A. (2011a), “Governors as opportunists: evidence from disaster declaration requests”, working paper for the American Political Science Association 2010 Annual Meeting, August 27, available at: www.andrew.cmu.edu/user/gasper/WorkingPapers/govreqs.pdf (accessed May 30, 2012).

- Gasper, J. and Reeves, A. (2011b), “Make it rain: retrospection and the attentive electorate in the context of natural disasters”, American Journal of Political Science, Vol. 55 No. 2, pp. 340-355.

- George, A.L. and Bennett, A. (2005), Case Studies and Theory Development in the Social Sciences, MIT Press, Cambridge and London. [Google Scholar]

- Gerber, B. and Cohen, D. (2008), “Katrina and her waves: presidential leadership and disaster management in an intergovernmental context”, in Pinkowski, J. (Ed.), Disaster Management Handbook, CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, pp. 51-74. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, P.A. and Soskice, D. (2001), “An introduction to varieties of capitalism”, in Hall, I.P.A. and Soskice, D. (Eds), Varieties of Capitalism: The Institutional Foundations of Comparative Advantage, Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 1-70. [Google Scholar]

- Healy, A. and Malhotra, N. (2009), “Myopic voters and natural disaster policy”, American Political Science Review, Vol. 103 No. 3, pp. 387-406.

- Healy, A. and Malhotra, N. (2010), “Random events, economic losses, and retrospective voting: implications for democratic competence”, Quarterly Journal of Political Science, Vol. 5 No. 2, pp. 193-208.

- Hine, D. (2010), “The 2009 influenza pandemic: an independent review of the UK response to the 2009 influenza pandemic”, Cabinet Office, London, available at: http://apps.infomedia.dk/Ms3E/ShowArticle.aspx?outputFormat=Full&Duid=e02f48d9 (accessed May 30, 2012).

- Immergut, E. (1992), “The rules of the game: the logic of health policy-making in France, Switzerland and Sweden”, in Steinmo, S. Thelen, K. and Longstreth, F. (Eds), Structuring Politics: Historical Institutionalism in Comparative Analysis, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 57-89. [Google Scholar]

- Infomedia (2012), “Media monitoring database”, available at: www.infomedia.dk/servicemenu/english/english/ (accessed May 30, 2012).

- Key, V.O. (1966), The Responsible Electorate: Rationality in Presidential Voting 1936–1960, Belknap Press, Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- Kristeligt Dagblad (2009), “Blød Kamp mod H1N1 herhjemme”, July 16, p. 3, available at: www.kristeligt-dagblad.dk/artikel/331404:Danmark--Bloed-kamp-mod-H1N1-herhjemme (accessed May 30, 2012).

- Landmann, T. (2008), Issues and Methods in Comparative Politics, Routledge, Abingdon. [Google Scholar]

- Lenz, G. (2010), “Understanding and curing myopic voting”, Preliminary Draft, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, available at: www.princeton.edu/csdp/events/Lenz%2012092010/Lenz-12092010.pdf (accessed May 30, 2012).

- Lewis, J. (2005), Health Policy and Politics: Networks, Ideas and Power, IP Communications, Melbourne. [Google Scholar]

- Lijphart, A. (1971), “Comparative politics and the comparative method”, American Political Science Review, Vol. 65 No. 3, pp. 682-693. [Google Scholar]

- Maor, M. (2011), “Organizational reputations and the observability of public warnings in 10 pharmaceutical markets”, Governance, Vol. 24 No. 3, pp. 557-582. [Google Scholar]

- Mereckiene, J. (2010), “Overview of pandemic A(H1N1) 2009 influenza vaccination in Europe”, Preliminary results of survey conducted by VENICE, ESCAIDE 2010, Lisbon, available at: http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/ESCAIDE/Materials/Presentations%202010/ESCAIDE2010_Late_Breakers_Mereckiene.pdf (accessed May 30 2012).

- Mereckiene, J., Cotter, S., Weber, J.T., Nicoll, A., D'Ancona, F.D., Lopalco, P.L., Johansen, K., Wasley, A.M., Jorgensen, P., Lévy-Bruhl, D., Giambi, C., Stefanoff, P., Dematte, L. and O'Flanagan, D. (2012), “Influenza A(H1N1)PDM09 vaccination policies and coverage in Europe”, Eurosurveillance, Vol. 17 No. 4, pp. 1-10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Mesquita, B., Smith, A., Siverson, R. and Morrow, J. (2003), The Logic of Political Survival, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Morrow, J., Mesquita, B., Siverson, R. and Smith, A. (2008), “Retesting selectorate theory: separating the effects of W from other elements of democracy”, American Political Science Review, Vol. 102 No. 3, pp. 393-400.

- Neustadt, R.E. and Fineberg, H.V. (1978), The Swine Flu Affair: Decision-Making on a Slippery Disease, US Department of Health, Education and Welfare, Washington, DC. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- New York Times (2009a), “President enlists cabinet for a pandemic”, May 2, p. A8, available at: www.nytimes.com/2009/05/02/us/politics/02crisis.html (accessed May 30, 2012).

- New York Times (2009b), “The next steps: predictions, protection and prevention”, May 22, available at: http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9C04E4DC143BF931A15756C0A96F9C8B63 (accessed May 30, 2012).

- (The) Norwegian Directorate for Civil Protection and Emergency Planning (2010), “Ny influensa A(H1N1) 2009: Gjennomgang av erfaringene i Norge”, Oslo, available at: www.dsbinfo.no/DSBno/2010/Rapport/Pandemirapport/ (accessed May 30, 2012).

- Politiken (2005a), “Hård kritik af tsunami-indsats i flere lande”, May 24, available at: http://politiken.dk/indland/ECE114024/haard-kritik-af-tsunami-indsats-i-flere-lande (accessed May 30, 2012).

- Politiken (2005b), “Flodbølge i Asien: 60.000 døde efter flodbølge – tallet stiger”, December 29, p. 1, available at: http://apps.infomedia.dk/Ms3E/ShowArticle.aspx?outputFormat=Full&Duid=e02f48d9 (accessed May 30, 2012).

- Politiken (2009), “Findes der en vaccine mod panik?”, August 3, p. 1, available at: http://politiken.dk/debat/ledere/ECE761707/leder-vaccine-mod-panik (accessed May 30, 2012).

- Preston, T. (2008), “Weathering the politics of responsibility and blame: the Bush administration and its response to Hurricane Katrina”, in Boin, A. Mcconnell, A. and Hart, P. (Eds), Governing After Crisis – the Politics of Investigation, Accountability and Learning, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 33-61. [Google Scholar]

- Przeworski, A. and Teune, H. (1970), The Logic of Comparative Social Inquiry, John Wiley, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Reeves, A. (2011), “Political disaster: unilateral powers, electoral incentives, and presidential disaster declarations”, Journal of Politics, Vol. 73 No. 4, pp. 1142-1151. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. (1999), Development as Freedom, Knopf, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. (2009), The Idea of Justice, Allen Lane, London. [Google Scholar]

- Singleton, J.A. (2010), H1N1 Vaccination Coverage: Updated Interim Results, CDC Immunization Services Division, Atlanta, GA. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, M.L., van Vliet, J.A. and Timen, A. (2011), “Chronological overview of the 2009/2010 H1N1 influenza pandemic and the response of the centre for infectious disease control RIVM”, Netherlands National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM), Bilthoven, available at: www.rivm.nl/bibliotheek/rapporten/215011006.pdf (accessed May 30 2012).

- Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency (2011), “Influensa A(N1N1) 2009 – utvärdering av förberedelser och hantering av pandemin”, Edita Västra Aros, Västerås, available at: www.socialstyrelsen.se/Lists/Artikelkatalog/Attachments/18243/2011-3-3.pdf (accessed May 30, 2012).

- Vanhanen, T. (2011), “Measures of democracy 1810-2010”, FSD1289, version 5.0 (2011-07-07), Finnish Social Science Data Archive, Tampere, available at: www.fsd.uta.fi/en/data/catalogue/FSD1289/meF1289e.html (accessed May 30, 2012).

- Wall Street Journal (2009a), “Plans for vaccination campaign begin”, July 10, available at: http://online.wsj.com/article/SB124714942306818305.html (accessed May 30, 2012).

- Wall Street Journal (2009b), “US to Buy H1N1 vaccine components from four firms”, July 14, available at: http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052970203739404574286602600418542.html (accessed May 30, 2012).

- Wall Street Journal (2009c), “Pregnant women, kids get vaccine first – swine flu panel says health-care workers and groups with highest risk of complications should jump to from of line”, July 30, available at: http://online.wsj.com/article/SB124887563173290207.html (accessed May 30, 2012).

- Wall Street Journal (2009d), “For flu vaccine, US sets aside $1 Billion”, May 23, available at: http://online.wsj.com/article/SB124303594956748749.html (accessed May 30, 2012).

- Walter, D., Böhmer, M.M., an der Heiden, M., Reiter, S., Krause, G. and Wichmann, O. (2011), “Monitoring pandemic influenza A(H1N1) vaccination coverage in Germany 2009/10 -- results from thirteen consecutive cross-sectional surveys”, Vaccine, Vol. 29 No. 23, pp. 4008-4012. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wortley, P. (2010), H1N1 Vaccine: Implementation Update, Immunization Services Division, CDC, Atlanta, GA. [Google Scholar]

- YouGov (2009), “Survey of trust: who do the danes trust?”, available at: www.mm.dk/sites/default/files/tillid2009_0.pdf (accessed May 30, 2012).

Further reading

- Public Health Agency of Canada (2010), “Lessons learned review: public health agency of Canada and health Canada response to the 2009 H1N1 pandemic”, November, available at: www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/about_apropos/evaluation/reports-rapports/2010-2011/h1n1/index-eng.php (accessed May 30, 2012).