Abstract

We newly designed a functionalized monomer (PhAVE-AcOH) containing a phenylacetylene (PhA) group and a 1-(acetoxy)ethoxy group, the latter of which is expected to act as an initiator moiety in combination with Lewis acid-based activators under living cationic polymerization conditions. A polyPhA-based multifunctional initiator poly(PhAVE-AcOH) with a narrow molecular weight distribution (Mw/Mn = 1.02) was synthesized by Rh complex-mediated living coordination polymerization of PhAVE-AcOH. Then, living cationic graft polymerization of isobutyl vinyl ether (IBVE) was performed employing the pendant 1-(acetoxy) ethoxy initiating moiety of poly(PhAVE-AcOH) to form polyIBVE-grafted polyPhA(polyPhA-g-polyIBVE), where both the main chain and side chains possessed well-controlled structures (Mw/Mn = 1.05–1.10). We found that UV–vis absorption spectra of polyPhA-g-polyIBVE were progressively redshifted with increasing molecular weights of the graft chain.

Introduction

The precision synthesis of graft polymers has been of considerable interest following the discovery of the living polymerization technique.1−6 Compared to linear polymers, densely grafted polymers having corresponding molar masses generally show smaller hydrodynamic radii, lower melt and solution viscosities, lower glass transition temperatures, lower crystallinities, and higher solubilities that arise from their compact structures and flexible graft chains.7−12 Synthesis of brush-shaped polymers has been mainly achieved by the following three methodologies: (1) the “grafting-onto” method where separately synthesized end-functionalized polymers are attached onto a multifunctional linear backbone polymer;13−15 (2) the “grafting-from” method involving the graft polymerization of monomers from a linear macromolecular initiator having multiple initiating sites;16−18 and (3) the “grafting-through” method (so-called macromonomer methodology) in which macromonomers are polymerized to form grafted polymers.19−21 Thus, for the synthesis of well-defined macromonomers and multi-functionalized macromolecular initiators, not only the molecular design of multi-functionalized monomers containing functional groups of different reaction characteristics but also their selective reactions are important.

Poly(phenylacetylene)s (polyPhAs) have attracted much attention because of their interesting physical and physicochemical properties.22−26 Recently, external stimuli-responsive properties of a series of polyPhA-bearing functionalized side chains have been investigated experimentally and theoretically.27−29 In addition, it has already been recognized that the side chain structures of polyPhAs play important roles not only to enhance their solubility but also to affect conjugation lengths in the main chain. Thus, the optical properties of such polyPhA-based materials can be controlled by the total molecular design of the side chain structure or the graft copolymer structure. Synthesis of well-defined graft polymers based on the polyPhA main chain has been studied extensively. Miura and Okada developed a series of grafted polyPhAs bearing polystyrene branches by living radical polymerization with a polyPhA-based initiator having multiple initiating sites via the “grafting-from” methodology.30,31 On the other hand, homo- and copolymerization of PhA-end-capped macromonomers using Rh-based catalysts via the “grafting-through” methodology has been well investigated to yield various functionalized grafted polyPhAs.32−35 Recently, we have reported that PhA-end-capped poly(vinyl ether) (polyVE)-based macromonomers can produce a brush-shaped polyPhA bearing polyVE side chains via Rh complex-mediated homopolymerization.36 However, with this methodology, grafted polymers having a main chain structure with a high degree of polymerization (DP) were difficult to synthesize due to steric hindrance of the macromonomers for living coordination homopolymerization (Scheme 1, route A). Here, we propose a synthetic strategy combining two types of controlled polymerizations to design well-defined grafted polymers consisting of a polyPhA backbone and polyVE pendants via the “grafting-from” methodology. In this study, we first synthesized a PhA derivative (PhAVE-AcOH) bearing a 1-(acetoxy)ethoxy group, which is an initiating site for living cationic polymerization. Next, we synthesized a polyPhA-based multifunctional initiator [poly(PhAVE-AcOH)] by Rh complex-mediated living coordination polymerization of PhAVE-AcOH. The resulting poly(PhAVE-AcOH) was then employed as a macromolecular multifunctional initiator in living cationic polymerization of isobutyl vinyl ether (IBVE) to afford the target polyPhA having both well-defined main chain and the side chains structures (Scheme 1; route B). Solutions of the resulting graft polymers showed intriguing changes in color depending on the side chain lengths, i.e., molecular weight of polyIBVE. Our strategy to combine two types of living polymerization techniques thus will enable the design of a wide variety of polyPhA-based graft polymers, where the length and type of pendant polyVEs can be modified concurrently.

Scheme 1. Two Routes for the Synthesis of Poly(vinyl ether)-Grafted Poly(phenylacetylene)s by a Combination of Living Coordination Polymerization and Living Cationic Polymerization.

Results and Discussion

In our previous report,36 we presented the synthesis of a novel bifunctional compound having both phenylacetylene and VE moieties, revealed that its trifluoroacetic acid adduct with 1-(trifluoroacetoxy)ethoxy group can act as novel initiators for living cationic polymerization of VEs, and then succeeded in the controlled synthesis of a novel PhA-end-capped polyVE macromonomer. Moreover, we described that the polymerization of the PhA-end-capped polyVE-based macromonomer using Rh catalysis ([(nbd)RhCl]2 (nbd = 2,5-norbornadiene)) allowed the synthesis of graft copolymers consisting of a polyPhA main chain and well-defined polyVE side chains. We initially attempted to synthesize a graft copolymer with well-defined main chain and side chains using the “grafting-through” strategy by living coordination polymerization with the Rh catalyst system [1/(Ph-F)3P; 1 = Rh(CPh = CPh2)(nbd)(Ph-F)3P, (Ph-F)3P = tris(4-fluorophenyl)phosphine], which is an effective catalyst for the living polymerization of PhA derivatives37 in toluene at 25 °C (Scheme 1; route A). However, size exclusion chromatography (SEC) analysis indicated that the polymerization failed because no molecular weight increase was observed. The elution peak of the major compound in the reaction mixture did not shift to a higher-molecular-weight region as compared to the corresponding macromonomer. The graft copolymer synthesis was then attempted by the “grafting-from” methodology, that is, graft polymerization of VEs was carried out with a macromolecular multifunctional initiator bearing pendant 1-(acetoxy)ethoxy groups. As shown in Scheme 1 route B, the synthesis of graft copolymer polyPhA-g-polyIBVE was based on a two-step synthetic strategy: (1) synthesis of the macromolecular initiator [poly(PhAVE-AcOH)] by living coordination polymerization and (2) synthesis of the graft copolymer of IBVE with poly(PhAVE-AcOH) by living cationic polymerization. It should be noted that the combination of the two types of controlled polymerization techniques allows multiple means to control the structure of the graft copolymers, where the lengths of the pendant polyIBVEs and the backbone polyPhA can be concurrently regulated.

Synthesis of PhAVE-AcOH

Recently, we have focused on the 1-(trifluoroacetoxy)ethoxy group, which can act as an initiator for living cationic polymerization of VEs, and succeeded in the synthesis of various types of end-functionalized polyVEs.36,38−42 However, introduction of the 1-(trifluoroacetoxy)ethoxy group to polymer side chains as a macromolecular initiator is difficult due to its moisture sensitivity. To attain an effective macromolecular initiator, we instead focus on the 1-(acetoxy)ethoxy group, which can be prepared by the addition of acetic acid and has already been recognized as an initiator moiety in combination with Lewis acid-based activators under living cationic polymerization conditions.43,44 As depicted in Scheme 1, PhAVE reacted with 2 equivs of acetic acid at 60 °C for 4 h to give PhAVE-AcOH in 97% yield. The structure of PhAVE-AcOH was characterized by 1H and 13C NMR. As shown in Figure 1a, 1H NMR analysis of PhAVE-AcOH showed a series of characteristic resonances, including those of the phenyl protons (peak c at δ 8.0 and peak b at δ 7.6 ppm), the 1-(acetoxy)ethoxy group protons (peak f at δ 6.0, peak h at δ 2.1, and peak g at δ 1.4 ppm), and the ethynyl protons (peak a at δ 3.2 ppm). The integration area ratios of a:c:f are 1.00:2.00:1.00, which were in good agreement with the proton number ratios of the proposed structure.

Figure 1.

1H NMR spectra of (a) PhAVE-AcOH, (b) poly(PhAVE-AcOH), and (c) polyPhA-g-polyIBVE in CDCl3 (asterisk, CHCl3; x, remaining solvents).

Polymerization of PhAVE-AcOH with the Rh Catalyst

Polymerization of PhAVE-AcOH was investigated in toluene at 25 °C for 1.5 h using a binary Rh catalyst system [1/(Ph-F)3P] ([PhAVE-AcOH]0/[1]0/[(Ph-F)3P]0 = 250/1/5, [PhAVE-AcOH]0 = 50 mmol L–1). The reaction was quenched with acetic acid through hydrogenation of the ω-terminal.45 The resulting polymer [poly(PhAVE-AcOH)] was analyzed by refractive index (RI)-detected SEC in THF. The SEC curve of the obtained poly(PhAVE-AcOH) shows a unimodal peak with relatively broad molecular weight distribution (MWD) (Mn = 15,000, Mw/Mn = 1.43, as estimated using polystyrene standards). However, we found that the present polymerization proceeded in a controlled manner at 0 °C. As shown in Figure 2a, the recorded SEC chromatogram of the poly(PhAVE-AcOH) showed a unimodal and narrow elution peak (Mn = 42,000, Mw/Mn = 1.02). The 1H NMR spectrum of the isolated poly(PhAVE-AcOH) is depicted in Figure 1b. The signals of phenyl and −CH=C– protons (peaks c′, b′, and a′) coming from the polyPhA repeating units appeared at δ 7.6, 6.7, and 5.7 ppm, respectively. The ratio of the resonance intensities of the methine proton versus aromatic protons in poly(PhAVE-AcOH) (peaks f′ and c′) was 0.998:2.00, indicating that the pendant 1-(acetoxy)ethoxy group was intact under the living coordination polymerization conditions. In addition, a clear signal at δ 5.7 ppm (peak a′) was assigned to the cis olefinic proton, indicating that the backbone of polyPhA possessed a cis-transoidal structure. The cis content of poly(PhAVE-AcOH) was estimated to be 92%. The cis content is nearly identical to those of the polyPhA derivatives synthesized by using the same Rh catalyst system [1/(Ph-F)3P].46 All the resonances are relatively broad due the rigid conformation of the main chain that restricted the motion of the backbone. These results clearly indicate that the controlled coordination polymerization of PhAVE-AcOH resulted in the successful synthesis of a well-defined macromolecular multifunctional initiator [poly(PhAVE-AcOH)].

Figure 2.

(a) RI-detected (solid line) and UV-detected (254 nm, dotted line) SEC curves of poly(PhAVE-AcOH) and the respective graft copolymers prepared by cationic polymerization of IBVE with poly(PhAVE-AcOH) as a macromolecular multifunctional initiator. (b) Time–conversion curve for the polymerization of IBVE. (c) First-order kinetic plot of monomer conversion. (d) Mn estimated by PSt-calibrated SEC (open circle) and SEC-MALLS (closed circle) and Mw/Mn values of polyPhA-g-polyIBVE plotted against monomer conversion. Polymerization of IBVE was conducted with poly(PhAVE-AcOH)/EtAlCl2/dioxane in toluene at −35 °C ([IBVE]0 = 1.0 M, [EtAlCl2]0 = 50 mM, [dioxane]0 = 2.0 M, [PhAVE-AcOH*]0 = 20 mM; [PhAVE-AcOH*], concentration based on repeating units).

Cationic Polymerization of IBVE with Poly(PhAVE-AcOH)

There have been reports about living cationic polymerization of a number of vinyl monomers, such as alkyl vinyl ether, isobutylene, and styrene-type monomers.47 Among them, the adducts with a 1-(acetoxy)ethoxy group, which are prepared from acetic acid and alkyl vinyl ethers, can induce living cationic polymerization of VEs in the presence of an activator, such as ZnCl2 or EtAlCl2.43,44 In the present paper, pendant 1-(acetoxy)ethoxy groups were employed as initiating sites for cationic polymerization of IBVE. The cationic polymerization of IBVE was carried out with poly(PhAVE-AcOH) as a macromolecular multifunctional initiator, EtAlCl2 as an activator, and dioxane as an added base at −35 °C in toluene under dry nitrogen for 1–12 h ([PhAVE-AcOH*]0/[IBVE]0/[EtAlCl2]0/[dioxane]0 = 1/100/5/200; [PhAVE-AcOH*], concentration based on repeating units). The reaction was quenched by using sodiomalonic ester as an end-capping agent.48 The polymerization product was obtained as a reddish yellow sticky solid that is soluble in common organic solvents such as toluene, CHCl3, and THF. Figure 2b shows the time–conversion curve obtained for the polymerization of IBVE, showing that the polymerization proceeded smoothly without an induction phase then reaching over 90% conversion within 12 h. The first-order kinetic plot for the polymerizations of IBVE revealed a linear dependence indicating a constant carbocationic species concentration indicative of the absence of significant termination reactions (Figure 2c). The resulting graft copolymer was analyzed in THF using a size exclusion chromatograph equipped with RI and UV (254 nm) dual detectors. The SEC traces for the obtained copolymer are shown in Figure 2a; the peak of the macromolecular initiator completely disappeared after the graft polymerization, and two new peaks emerged. The ratio of the two polymerization products was ∼8:2, as determined from their peak areas in the SEC eluogram. The higher-molecular-weight peaks have much larger molecular weights (Mn = 159,000–356,000) compared to the macromolecular initiator (Mn = 42,000), and these peaks obtained with RI and UV detectors were nearly identical, indicating that the polymers possess a chromophoric polyPhA backbone. On the other hand, the lower-molecular-weight peaks were detected only by an RI detector, showing that no chromophoric moieties are included. These peaks were assignable to free polyIBVE, probably caused by the cationic polymerization initiated with the adventitious water in the polymerization system. Focusing on the higher-molecular-weight peaks, the SEC curves exhibited a unimodal peak and the peak top shifted to higher-molecular-weight regions as the reaction time increased (Table 1). Figure 2d is the plot of the values of Mn and Mw/Mn of the polymers against monomer conversion in the experiment shown in Figure 2b. The Mn values of the obtained copolymers (the open circles in Figure 2d), which were measured by polystyrene (PSt)-calibrated SEC, were much smaller than the calculated values (the solid line in Figure 2d), which is due to the significant difference in the hydrodynamic volume of the polyPhA with densely grafted polyIBVE pendants with respect to PSt standards. For isolation of polyPhA-g-polyIBVE, the reaction mixture was subjected to reprecipitation from toluene into EtOH to remove the lower-molecular-weight product followed by centrifugation. The SEC trace of the obtained polymer suggested the successful isolation of the high-molecular-weight product generated in the cationic polymerization. The isolated polymers were subjected to SEC–multi-angle laser light scattering (MALLS) to determine the absolute molecular weight (Mn,MALLS) of polyPhA-g-polyIBVE. The observed Mn,MALLS values (the closed circles in Figure 2d) were found to increase in direct proportion to the monomer conversion and were also in good agreement with the calculated values, supporting that the side chain lengths of the graft copolymer polyPhA-g-polyIBVE are well controlled by the living cationic polymerization. The isolated polymer was subjected to 1H NMR analysis (Figure 1c). In addition to the signals of the aromatic protons in polyPhA at δ 6.5–7.0 and 7.5–8.0 ppm (peaks B and C), the broad aliphatic protons in the pendant polyIBVE segments were clearly observed at δ 0.9 and 3.0–4.0 ppm. Furthermore, signals assignable to the polyPhA backbone protons were highly broadened, probably due to decreased mobility of the aromatic moieties substituted by the polyIBVE chains and directly attached to the stiff polyPhA backbone.49−51 This result indicates that the pendant 1-(acetoxy)ethoxy groups on the poly(PhA-AcOH) are active enough to induce living cationic polymerization of IBVE and useful for the synthesis of graft copolymer polyPhA-g-polyIBVE via “grafting-from” methodology. However, a small peak was also observed at δ 5.9 ppm (peak f″), which was attributable to the proton signal of an 1-(acetoxy)ethoxy group. The graft efficiencies or initiation efficiencies (fs) for the living cationic polymerization process were preliminarily estimated through the integration area ratios of f″:A as 60–67%. Indeed, the initiation of the graft polymerization was not quantitative, but the residual pendant 1-(acetoxy)ethoxy groups induced no side reactions throughout the graft polymerization.

Table 1. Results from Polymerization of IBVE from Poly(PhAVE-AcOH)a.

| reaction time (h) | conversion (%)b | Mn,theoryc(g mol–1) | DPn,theoryd | Mn,SECe(g mol–1) | Mw/Mne | Mn,MALLSf(g mol–1) | fb (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| poly(PhAVE-AcOH) | 69,300 | 42,000 | 1.02 | 69,000 | |||

| 1 | 27 | 745,000 | 27 | 159,000 | 1.05 | 395,000 | 60 |

| 2 | 40 | 1,071,000 | 40 | 215,000 | 1.08 | 890,000 | 66 |

| 3 | 76 | 1,972,000 | 76 | 297,000 | 1.10 | 1,330,000 | 62 |

| 12 | 98 | 2,523,000 | 98 | 356,000 | 1.07 | 1,706,000 | 67 |

Polymerization was conducted with EtAlCl2/dioxane in toluene at −35 °C, [IBVE]0 = 1.0 mol L–1; [PhAVE-AcOH*]0/[IBVE]0/[EtAlCl2]0/[dioxane]0 = 1/100/5/200; [PhAVE-AcOH*], concentration based on repeating units. The reaction was quenched with a solution of sodiomalonic ester in toluene/dioxane.

Determined by 1H NMR.

Calculated from Mn,theory = ([IBVE]0/[PhAVE-AcOH*]0 × (molecular weight)IBVE × (conversion)IBVE × (DPn)poly(PhAVE-AcOH)) + (molecular weight)poly(PhAVE-AcOH).

Calculated from DPn,theory of polyIBVE side chains = [IBVE]0/[PhAVE-AcOH*]0 × (conversion)IBVE.

Estimated by PSt-calibrated SEC in THF.

Estimated by SEC in THF with a multi-angle laser light scattering detector.

Further investigation about the graft copolymers structure can give useful information for the extent of control in the polyIBVE-based side chain formation. To this end, direct analysis of the side chains was performed.52 In the present study, graft copolymers with well-controlled architecture are defined as the polymers possessing controlled length of either the backbone or side chains. Because the graft copolymer has the cleavable ester linkage between the main chain and side chains, direct analysis of the pendant polyIBVE can be achieved by cleaving the linkages. We carried out hydrolysis by refluxing the graft copolymer in the MeOH/THF mixture in the presence of KOH.53 The polymers obtained from the cleavage reactions were then characterized by SEC to examine the growth of the side chains with increasing the monomer conversion (Figure 3 and Table 2). Following the hydrolysis reactions, only a single low-molecular-weight polymer was observed in each experiment, which indicates that the cleavage reaction was nearly quantitative. Because the polyPhA backbone makes up a low percentage of the overall mass of the graft copolymer, it is undetectable after the side chains are removed. MWDs of polyIBVEs obtained from the graft copolymer were ca. 1.4 or below. This result again indicates that the graft polymerization of IBVE proceeded in a controlled manner. Furthermore, we note that the Mns of the cleaved polyIBVE side chains agree with those of the small peaks observed in the lower-molecular-weight region of SEC traces of the graft copolymer in Figure 2a. For example, the Mn of the small peak observed for the graft copolymer at 98% conversion of IBVE (reaction time = 12 h) is 12,000 and that for the polyIBVE obtained by hydrolysis is also 12,000. On the basis of this agreement, the peak was also assignable to the polyIBVE-free polymer. Both the 1H NMR and SEC measurements indicate that the graft copolymers having controlled molecular weight and narrow molecular weight distribution with a polyPhA backbone and polyIBVE side chains were prepared by the combination of living coordination polymerization and living cationic polymerization.

Figure 3.

SEC curves of the cleaved side chains from the graft polymers (polyPhA-g-polyIBVE) obtained at various IBVE conversions.

Table 2. Molecular Weights and Dispersity of PolyIBVE Side Chains Cleaved from the Graft Copolymer PolyPhA-g-polyIBVE.

| reaction time (h) | IBVE conversion (%)a | Mn,theoryb (g mol–1) | Mn,cleavedc (g mol–1) | Mw/Mnc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 27 | 2700 | 3800 | 1.37 |

| 2 | 40 | 4000 | 5000 | 1.30 |

| 3 | 76 | 7600 | 9900 | 1.16 |

| 12 | 98 | 9800 | 12,000 | 1.07 |

Determined by 1H NMR.

Calculated from Mn,theory = ([IBVE]0/[PhAVE-AcOH*]0 × (molecular weight)IBVE × (conversion)IBVE)

Estimated by PSt-calibrated SEC in THF.

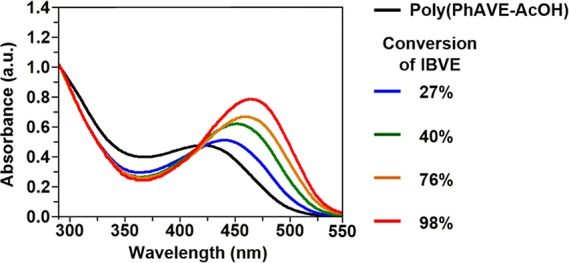

Optical Properties of PolyPhA-g-polyIBVE

As depicted in Figure 4, we have discovered a very interesting fact that the UV–vis absorption maxima of polyPhA-g-polyIBVE were redshifted depending on the polyIBVE side chain length. The normalized UV–vis absorption spectrum of poly(PhAVE-AcOH) in dichloromethane at 25 °C exhibits a peak in the range of 375–550 nm with maximum at 425 nm, while the maxima of polyPhA-g-polyIBVE at 27, 40, 76, and 98% conversion of IBVE were 450, 455, 460, and 470 nm, respectively. This result indicates that the graft copolymer have longer conjugation lengths in the main chain than poly(PhAVE-AcOH). It has been reported that the absorption peak of a polyPhA derivative shifts to a longer wavelength as the steric effect of ring substituents increases.54 For example, poly[(o-methylphenyl)acetylene] exhibits an absorption at 440 nm,55,56 while poly{[o-(trimethylsilyl)phenyl]-acetylene}, which possesses a bulkier trimethylsilyl substituent, has an absorption at 520 nm. Grubbs and co-workers have proposed an idea that the steric requirements of the substituents impose a planar conformation on the polymer backbone.57 The bulky polyIBVE side chain of the grafted copolymer should prevent the polyPhA backbone from bending and twisting and force the main chain to take a more planar conformation.

Figure 4.

Normalized absorption spectra of poly(PhAVE-AcOH) and polyPhA-g-polyIBVE in dichloromethane obtained at various IBVE conversions in the cationic polymerization.

Conclusions

In summary, we have demonstrated an efficient and convenient route to the synthesis of a graft copolymer (polyPhA-g-polyIBVE) containing a well-defined polyPhA backbone and well-defined polyIBVE side chains. This achievement was brought about by a successful combination of living coordination polymerization and living cationic polymerization. First, living coordination polymerization of PhAVE-AcOH led to the formation of polyPhA-based macromolecular multifunctional initiators [poly(PhAVE-AcOH)] with well-defined structures. Next, these macromolecular initiators are useful for the synthesis of polyPhA-g-polyIBVE via “grafting-from” methodology. Solutions of the resulting polymers showed intriguing changes in absorption color depending on the length of side chains. The conjugation lengths of the polyPhA main chain would be closely related to the pendant polyIBVE structure; we therefore expect to design various polyVEs-grafted conjugated polymers that are capable of responding to external stimuli such as pH, temperature, and addition of metal ions or biomolecules.

Experimental Section

Instruments

1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded at 25 °C on a Bruker model AC-500 spectrometer operating at 500 and 125 MHz, respectively, where chemical shifts (δ in ppm) were determined with respect to nondeuterated solvent residues as internal standards. Analytical size exclusion chromatography (SEC) was performed at 40 °C using 8.0 mm × 300 mm polystyrene gel columns (Shodex KF-804 x 2) on a TOSOH model DP-8020 equipped with a UV-8000 variable-wavelength UV–vis detector and a RI-8022 RI detector. The number-average molecular weight (Mn) and polydispersity ratio (Mw/Mn) were calculated from the chromatographs with respect to 15 polystyrene standards (Scientific Polymer Products, Inc.; Mn = 580–670,000 g mol–1, Mw/Mn = 1.01–1.07). SEC–multi-angle laser light scattering (MALLS) measurements were performed on a TOSOH GPC-8020 system, equipped with a column (Shodex KF-805 L), a Wyatt Technology, DAWN HELEOS multi-angle laser light scattering photometer with a He–Ne laser (λ0 = 658 nm), and a Wyatt Technology Optilab rEX differential refractometer, using CHCl3 as an eluent at a flow rate of 0.40 mL min–1. The SEC–MALLS profiles were recorded and analyzed using ASTRA software (ver.6.1.1, Wyatt Technology). Differential refractive index increments (∂n/∂c) for the polymers in CHCl3 were determined based on the peak area of the refractive index chromatograms and the polymer mass concentration (c) of the injected solutions assuming that all the injected polymers were fully recovered. UV–vis spectra were recorded using a quartz cell of 1 cm path length on a SHIMADZU Type UV-2550 spectrometer.

Materials

Unless otherwise stated, all commercial reagents were used as received. Ethyl aluminum dichloride (EtAlCl2; FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, 1.0 mol L–1 in n-hexane) was used as received. 2-Vinyloxyethyl 4-ethynylbenzoate (PhAVE) was prepared according to literature.39 Rh catalyst (1) was prepared according to literature.40 Isobutyl vinyl ether (IBVE; Aldrich, 99%) was dried overnight over KOH pellets and distilled twice over CaH2. Anhydrous solvents for reactions were purchased from Kanto Chemicals.

Synthesis of PhAVE-AcOH

Acetic acid (220 mg, 3.6 mmol) was added to PhAVE (400 mg, 1.8 mmol), and the mixture was stirred for 4 h at 60 °C under dry nitrogen. The reaction mixture was concentrated by evaporating off the unreacted acetic acid under reduced pressure. By column chromatography using mixed solvents of ethyl acetate and hexane (1/5 v/v), PhAVE-AcOH was obtained as pearl yellow solids (480 mg, 1.7 mmol) in 97% yield. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3, δ): 8.00 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H, Ar H), 7.55 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H, Ar H), 5.98 (q, J = 5.3 Hz, 1H, OCH(CH3)OCO), 4.45 (m, 2H, OCH2CH2), 3.92 (m, OCH2CH2), 3.23 (s, 1H, CH), 2.06 (s, 3H, COCH3), 1.42 (d, d, J = 5.3 Hz, 3H, CHCH3); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3, δ): 170.7, 165.8, 132.1, 130.0, 129.9, 126.9, 69.3, 82.8, 80.2, 66.9, 64.0, 21.2, 20.7.

Polymerization of PhAVE-AcOH with Rh Catalyst (1)

The polymerization using 1/(Ph-F)3P was carried out under the following conditions: [PhAVE-AcOH]0 = 50 mmol L–1, [1]0 = 0.2 mmol L–1, and [(Ph-F)3P]0 = 1.0 mmol L–1. A typical procedure is as follows: Rh catalyst (1; 2.4 mg, 3.2 μmol) was added to a toluene solution (16 mL) of PhAVE-AcOH (220 mg, 800 μmol) and (Ph-F)3P (5.1 mg, 16 μmol) under a dry nitrogen atmosphere. After being vigorously stirred for 24 h, the polymerization was quenched with acetic acid (4.5 mL). The reaction mixture was evaporated to dryness under reduced pressure and poured into a large amount of MeOH to precipitate the polymers. The resultant polymer was collected by centrifugation and dried under reduced pressure. Poly(PhAVE-AcOH) was obtained as red solid (200 mg) in 91% yield. The polymer structure was analyzed by 1H NMR measurement and analytical SEC in THF. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3, δ): 7.61 (2H), 6.71 (2H), 5.92 (1H), 5.72 (1H), 4.35 (2H), 3.85 (2H), 2.01 (3H), 1.34 (3H).

Cationic Polymerization of IBVE with Poly(PhAVE-AcOH)

The cationic polymerization of IBVE with poly(PhAVE-AcOH) was carried out under a dry nitrogen atmosphere in baked glass tubes equipped with a three-way stopcock. A typical example for the polymerization procedure is as follows: to a toluene solution (2.68 mL) of poly(PhAVE-AcOH) (11 mg, 0.04 mmol; the value based on repeating units), IBVE (0.52 mL, 4.0 mmol) and dioxane (0.68 mL, 8 mmol) was added EtAlCl2 (in hexane, 1.6 mol L–1; 0.12 mL, 0.20 mmol) at −35 °C under a dry nitrogen atmosphere. After the reaction time of 1, 2, 5, and 12 h, each polymerization was quenched with sodiomalonic ester solution (in toluene/dioxane (1.2/1 v/v), 0.23 mol L–1; 5.0 mL, 1.2 mmol). The conversion of IBVE was determined by 1H NMR analysis. The solution was diluted with toluene, then washed with brine, evaporated under reduced pressure, and then vacuum-dried to yield the target polymer (polyPhA-g-polyIBVE). Mn and Mw/Mn of the obtained polymers were determined by analytical SEC in THF. The toluene solution of the reaction mixture was poured into a large amount of EtOH to precipitate the polymers to remove the lower-molecular-weight product. The resultant polymer was collected by centrifugation and dried under reduced pressure. The isolated polymer structure was analyzed by 1H NMR measurement.

Hydrolysis of Graft Copolymer

To a solution of graft copolymer (20 mg) in THF (9 mL) was added a solution of KOH (9 g) in MeOH (18 mL); the resultant mixture was gently refluxed for 2 h. After cooling to room temperature, it was neutralized with a diluted aqueous HCl and the mixture was evaporated under reduced pressure. The residue was dissolved in toluene, washed with water, and evaporated under reduced pressure. The resulting polymer was subjected to SEC analysis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by KAKENHI (Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists B no. 26820314, 18 K05235) of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS), the Cooperative Research Program of ″Network Joint Research Center for Materials and Devices″, the Foundation for the Promotion of Ion Engineering, and the Kyoto Technoscience Center. We thank Fumitaka Ishiwari and Takanori Fukushima for their support with the SEC-MALLS measurements. We are indebted to Maruzen Petrochemical Co. (Tokyo, Japan) for donating 2-hydoxyethyl vinyl ether.

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Hsieh H. L.; Quirk R. P.. Anionic Polymerization: Principles and Practical Applications; Marcel Dekker; New York, 1996, Chapter 14, 369–392. [Google Scholar]

- Iha R. K.; Wooley K. L.; Nyström A. M.; Burke D. J.; Kade M. J.; Hawker C. J. Applications of Orthogonal “Click” Chemistries in the Synthesis of Functional Soft Materials. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 5620–5686. 10.1021/cr900138t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Y.; Li Y.; Burts A. O.; Ottaviani M. F.; Tirrell D. A.; Johnson J. A.; Turro N. J.; Grubbs R. H. EPR Study of Spin Labeled Brush Polymers in Organic Solvents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 19953–19959. 10.1021/ja2085349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng C.; Li Y.; Yang D.; Hu J.; Zhang X.; Huang X. Well-defined graft copolymers: from controlled synthesis to multipurpose applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 1282–1295. 10.1039/B921358A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito S.; Goseki R.; Ishizone T.; Hirao A. Synthesis of well-controlled graft polymers by living anionic polymerization towards exact graft polymers. Polym. Chem. 2014, 5, 5523–5534. 10.1039/C4PY00584H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Polymeropoulos G.; Zapsas G.; Ntetsikas K.; Bilalis P.; Gnanou Y.; Hadjichristidis N. 50th Anniversary Perspective: Polymers with Complex Architectures. Macromolecules 2017, 50, 1253–1290. 10.1021/acs.macromol.6b02569. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hadjichristidis N.; Pitsikalis M.; Pispas S.; Iatrou H. Polymers with Complex Architecture by Living Anionic Polymerization. Chem. Rev. 2001, 101, 3747–3792. 10.1021/cr9901337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin S.; Matyjaszewski K.; Xu H.; Sheiko S. S. Synthesis and Visualization of Densely Grafted Molecular Brushes with Crystallizable Poly(octadecyl methacrylate) Block Segments. Macromolecules 2003, 36, 605–612. 10.1021/ma021472w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Viville P.; Leclère P.; Deffieux A.; Schappacher M.; Bernard J.; Borsali R.; Brédas J.-L.; Lazzaroni R. Atomic force microscopy study of comb-like vs. arborescent graft copolymers in thin films. Polymer 2004, 45, 1833–1843. 10.1016/j.polymer.2004.01.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Desvergne S.; Héroguez V.; Gnanou Y.; Borsali R. Polymacromonomers: Dynamics of Dilute and Nondilute Solutions. Macromolecules 2005, 38, 2400–2409. 10.1021/ma0487958. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hadjichristidis N.; Iatrou H.; Pitsikalis M.; Mays J. Macromolecular architectures by living and controlled/living polymerizations. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2006, 31, 1068–1132. 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2006.07.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Uhrig D.; Mays J. Synthesis of well-defined multigraft copolymers. Polym. Chem. 2011, 2, 69–76. 10.1039/C0PY00185F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schappacher M.; Deffieux A. New Polymer Chain Architecture: Synthesis and Characterization of Star Polymers with Comb Polystyrene Branches. Macromolecules 2000, 33, 7371–7377. 10.1021/ma0001436. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu S. W.; Hirao A. Anionic Synthesis of Well-Defined Poly(m-halomethylstyrene)s and Branched Polymers via Graft-onto Methodology. Macromolecules 2000, 33, 4765–4771. 10.1021/ma991793g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gacal B.; Durmaz H.; Tasdelen M. A.; Hizal G.; Tunca U.; Yagci Y.; Demirel A. L. Anthracene–Maleimide-Based Diels–Alder “Click Chemistry” as a Novel Route to Graft Copolymers. Macromolecules 2006, 39, 5330–5336. 10.1021/ma060690c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng G.; Böker A.; Zhang M.; Krausch G.; Müller A. H. E. Amphiphilic Cylindrical Core–Shell Brushes via a “Grafting From” Process Using ATRP. Macromolecules 2001, 34, 6883–6888. 10.1021/ma0013962. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Börner H. G.; Beers K.; Matyjaszewski K.; Sheiko S. S.; Möller M. Synthesis of Molecular Brushes with Block Copolymer Side Chains Using Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization. Macromolecules 2001, 34, 4375–4383. 10.1021/ma010001r. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H.-i.; Jakubowski W.; Matyjaszewski K.; Yu S.; Sheiko S. S. Cylindrical Core–Shell Brushes Prepared by a Combination of ROP and ATRP. Macromolecules 2006, 39, 4983–4989. 10.1021/ma0604688. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukahara Y.; Mizuno K.; Segawa A.; Yamashita Y. Study on the radical polymerization behavior of macromonomers. Macromolecules 1989, 22, 1546–1552. 10.1021/ma00194a007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Breitenkamp K.; Simeone J.; Jin E.; Emrick T. Novel Amphiphilic Graft Copolymers Prepared by Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization of Poly(ethylene glycol)-Substituted Cyclooctene Macromonomers. Macromolecules 2002, 35, 9249–9252. 10.1021/ma021094v. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai A.; Ochiai B.; Endo T. Synthesis and Radical Polymerization of a Novel Macromonomer Obtained by Living Cationic Ring-Opening Polymerization of an Optically Active Cyclic Thiourethane by a New Initiator Carrying Styryl Group. Macromolecules 2004, 37, 4417–4421. 10.1021/ma040009b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yashima E.; Maeda K.; Iida H.; Furusho Y.; Nagai K. Helical Polymers: Synthesis, Structures, and Functions. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 6102–6211. 10.1021/cr900162q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiwari F.; Nakazono K.; Koyama Y.; Takata T. Rational control of a polyacetylene helix by a pendant rotaxane switch. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 11739–11741. 10.1039/c1cc14404a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motoshige A.; Mawatari Y.; Yoshida Y.; Motoshige R.; Tabata M. Synthesis and solid state helix to helix rearrangement of poly(phenylacetylene) bearing n-octyl alkyl side chains. Polym. Chem. 2014, 5, 971–978. 10.1039/C3PY01000G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Freire F.; Quiñoá E.; Riguera R. Supramolecular Assemblies from Poly(phenylacetylene)s. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 1242–1271. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda T. Substituted Polyacetylenes: Synthesis, Properties, and Functions. Polym. Rev. 2017, 57, 1–14. 10.1080/15583724.2016.1170701. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu A.; Masuda T.; Zhang A. Stimuli-Responsive Polyacetylenes and Dendronized Poly(phenylacetylene)s. Polym. Rev. 2016, 57, 138–158. 10.1080/15583724.2016.1169547. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiwari F.; Fukasawa K.-i.; Sato T.; Nakazono K.; Koyama Y.; Takata T. A Rational Design for the Directed Helicity Change of Polyacetylene Using Dynamic Rotaxane Mobility by Means of Through-Space Chirality Transfer. Chem. – Eur. J. 2011, 17, 12067–12075. 10.1002/chem.201101727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai R.; Okade S.; Barasa E. B.; Kakuchi R.; Ziabka M.; Umeda S.; Tsuda K.; Satoh T.; Kakuchi T. Efficient Colorimetric Anion Detection Based on Positive Allosteric System of Urea-Functionalized Poly(phenylacetylene) Receptor. Macromolecules 2010, 43, 7406–7411. 10.1021/ma1016852. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miura Y.; Okada M. Synthesis of densely grafted copolymers by nitroxide-mediated radical polymerization of styrene using poly(phenylacetylene)s as a macroinitiator. Polymer 2004, 45, 6539–6546. 10.1016/j.polymer.2004.07.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miura Y.; Okada M. Synthesis of graft copolymer by ATRP of MMA from poly(phenylacetylene). J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem. 2006, 44, 6697–6707. 10.1002/pola.21758. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sanda F.; Gao G.; Masuda T. Helical polymer carrying helical grafts from peptide-based acetylene macromonomers: synthesis. Macromol. Biosci. 2004, 4, 570–574. 10.1002/mabi.200400019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda K.; Kamiya N.; Yashima E. Poly(phenylacetylene)s Bearing a Peptide Pendant: Helical Conformational Changes of the Polymer Backbone Stimulated by the Pendant Conformational Change. Chem. – Eur. J. 2004, 10, 4000–4010. 10.1002/chem.200400315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsuka I.; Sakai R.; Satoh T.; Kakuchi R.; Kaga H.; Kakuchi T. Metal–cation–induced chiroptical switching for poly(phenylacetylene) bearing a macromolecular ionophore as a graft chain. J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem. 2005, 43, 5855–5863. 10.1002/pola.21090. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W.; Shiotsuki M.; Masuda T.; Kumaki J.; Yashima E. Synthesis of Polymer Brushes Composed of Poly(phenylacetylene) Main Chain and Either Polystyrene or Poly(methyl methacrylate) Side Chains. Macromolecules 2007, 40, 178–185. 10.1021/ma061964z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Motoyanagi J.; Higashi K.; Minoda M. Synthesis of brush-shaped polymers consisting of a poly(phenylacetylene) backbone and pendant poly(vinyl ether)s via selective reaction of 2-Vinyloxyethyl 4-Ethynylbenzoate. J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem. 2014, 52, 2800–2805. 10.1002/pola.27304. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miyake M.; Misumi Y.; Masuda T. Living Polymerization of Phenylacetylene by Isolated Rhodium Complexes, Rh[C(C6H5)C(C6H5)2](nbd)(4-XC6H4)3P (X = F, Cl). Macromolecules 2000, 33, 6636–6639. 10.1021/ma000497x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Motoyanagi J.; Miyabara R.; Suzuki M.; Miki S.; Minoda M. A novel [60]fullerene-appended initiator for living cationic polymerization and its application to the synthesis of [60]fullerene-end-capped poly(vinyl ether)s. Polym. Chem. 2012, 3, 329–331. 10.1039/C2PY00522K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Motoyanagi J.; Kurata A.; Minoda M. Self-Assembly Behavior of Amphiphilic C60-End-Capped Poly(vinyl ether)s in Water and Dissociation of the Aggregates by the Complexing of the C60 Moieties with Externally Added γ-Cyclodextrins. Langmuir 2015, 31, 2256–2261. 10.1021/la504341s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motoyanagi J.; Ishikawa T.; Kurata A.; Minoda M. Design of Novel Brush-Shaped π-Conjugated Polymers Based on the Controlled Synthesis of Poly(Vinyl ether)s with a Terminal Ethynylbenzene Moiety. Kobunshi Ronbunshu 2015, 72, 318–323. 10.1295/koron.2014-0094. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa T.; Motoyanagi J.; Minoda M. Synthesis of Brush-shaped π-Conjugated Polymers Based on Well-defined Thiophene-end-capped Poly(vinyl ether)s. Chem. Lett. 2016, 45, 415–417. 10.1246/cl.160022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Motoyanagi J.; Ishikawa T.; Minoda M. Stimuli-Responsive Brush-Shaped Conjugated Polymers with Pendant Well-Defined Poly(Vinyl Ether)s. J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem. 2016, 54, 3318–3325. 10.1002/pola.28220. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aoshima S.; Higashimura T. Living cationic polymerization of vinyl monomers by organoaluminum halides. 3 Living polymerization of isobutyl vinyl ether by ethyldichloroaluminum in the presence of ester additives. Macromolecules 1989, 22, 1009–1013. 10.1021/ma00193a001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kamigaito M.; Sawamoto M.; Higashimura T. Living cationic polymerization of isobutyl vinyl ether by RCOOH/Lewis acid initiating systems: effects of carboxylate ions and Lewis acid activators. Macromolecules 1991, 24, 3988–3992. 10.1021/ma00014a003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumazawa S.; Castanon J. R.; Onishi N.; Kuwata K.; Shiotsuki M.; Sanda F. Characterization of the Polymerization Catalyst [(2,5-norbornadiene)Rh{C(Ph)=CPh2}(PPh3)] and Identification of the End Structures of Poly(phenylacetylenes) Obtained by Polymerization Using This Catalyst. Organometallics 2012, 31, 6834–6842. 10.1021/om300642b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nakazato A.; Saeed I.; Katsumata T.; Shiotsuki M.; Masuda T.; Zednik J.; Vohlidal J. Polymerization of Substituted Acetylenes by Various Rhodium Catalysts: Comparison of Catalyst Activity and Effect of Additives. J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem. 2005, 43, 4530–4536. 10.1002/pola.20934. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aoshima S.; Kanaoka S. A Renaissance in Living Cationic Polymerization. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 5245–5287. 10.1021/cr900225g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawamoto M.; Enoki T.; Higashimura T. End-functionalized polymers by living cationic polymerization. 1. Mono- and bifunctional poly(vinyl ethers) with terminal malonate or carboxyl groups. Macromolecules 1987, 20, 1–6. 10.1021/ma00167a001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simionescu C. I.; Percec V. Progress in polyacetylene chemistry. Prog. Polym. Sci. 1982, 8, 133–214. 10.1016/0079-6700(82)90009-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tabata M.; Yang W.; Yokota K. 1H-NMR and UV studies of Rh complexes as a stereoregular polymerization catalysts for phenylacetylenes: Effects of ligands and solvents on its catalyst activity. J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem. 1994, 32, 1113–1120. 10.1002/pola.1994.080320613. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kishimoto Y.; Eckerle P.; Miyatake T.; Kainosho M.; Ono A.; Ikariya T.; Noyori R. Well-Controlled Polymerization of Phenylacetylenes with Organorhodium(I) Complexes: Mechanism and Structure of the Polyenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 12035–12044. 10.1021/ja991903z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sumerlin B. S.; Neugebauer D.; Matyjaszewski K. Initiation Efficiency in the Synthesis of Molecular Brushes by Grafting from via Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization. Macromolecules 2005, 38, 702–708. 10.1021/ma048351b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hawker C. J. Architectural Control in “Living” Free Radical Polymerizations: Preparation of Star and Graft Polymers. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1995, 34, 1456–1459. 10.1002/anie.199514561. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W.; Shiotsuki M.; Masuda T. Synthesis and Characteristics of Poly(macromonomers) and Graft Copolymers Composed of Poly(phenylacetylene) Main Chain and Poly(ethylene oxide) Side Chains. Macromolecules 2007, 40, 1421–1428. 10.1021/ma062290v. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abe Y.; Masuda T.; Higashimura T. Polymerization of (o-methylphenyl)acetylene and polymer characterization. J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem. 1989, 27, 4267–4279. 10.1002/pola.1989.080271304. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda T.; Hamano T.; Tsuchihara K.; Higashimura T. Synthesis and characterization of poly[[o-(trimethylsilyl)phenyl]acetylene]. Macromolecules 1990, 23, 1374–1380. 10.1021/ma00207a023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsburg E. J.; Gorman C. B.; Grubbs R. H.. Modern Acetylene Chemistry; Stang P. J.; Diederich F., Eds.; VCH: New York, 1995; p 353. [Google Scholar]