Abstract

This study describes the solvent and catalyst-free Ugi reaction by way of twin screw extrusion (TSE). Multicomponent chemical synthesis can be converted into a single process without repeated use of solvents through TSE. High synthetic yields are achieved in short reaction times and produced in solvent-free conditions, which lead to a more environmentally friendly process.

Introduction

Mechanochemistry can be used to speed up chemical reactions while eliminating and reducing the use of solvents, thereby making chemical synthesis less hazardous and comparatively inexpensive.1 Mechanochemistry has made significant headway in the field of synthetic chemistry in the last few years, with ever-increasing research activities and the implementation of improved steps and methods for future applications.2,3

Mortar and pestle are being used in grinding and remain an efficient mechanochemical method that is used for the synthesis of chemical compounds.4,5 However, mechanical milling provides appreciably greater energy and is a more reliable and sophisticated choice in contrast to hand grinding. This is for the reason that the latter may deliver economic benefits for various experimental results due to its dependence on the grinding power and velocity of the operator. Recently, mechanochemical strategies have made significant progress in comparison to their humble beginnings and now consist of the use of planetary or vibrational ball mills and even extruders. Ball mills have been successfully applied in a range of organic synthetic yields, specifically C–C, C–N, C–O, and C–X bond formation,6−8 heterocycle synthesis,9−12 and even the synthesis of peptides,13,14 organic reactions, and metal-catalyzed reactions.15,16

Extrusion is used to describe a set of techniques that involve the transport of compound via a restricted space. Consequently, shear and forces of pressure are applied to the material, which, in turn, can stimulate and complete the chemical reaction.17 Initially, Paradkar et al. reported on the use of extraction with hot melt for the preparation of cocrystals.18 Subsequently, TSE was used for the production of organic metal structures19 and deep eutectic solvents.20 Owing to the advantages indicated concerning the use of TSE for the preparation of high-quality materials, in most cases, the products did not require purification after the process.

It should be noted that the reactions conducted on the ball mills lack temperature control and scalability. However, this can be overcome with the use of TSE. Chemical reactions such as aldol condensations, Michael reactions, Biginelli reaction, imine formation reactions, Knoevenagel condensations, molecular organic structures, papain-catalyzed oligopeptide, and even multicomponent and multistep reactions have been successfully undertaken by means of TSE.21−23

Multicomponent reactions (MCRs) is a green protocol that works by collecting molecules with great diversity, which are generated with a minimal synthetic effort, time, and the formation of by-products,24,25 wherein three or more compounds begin to react to each other to form a single new product, which has all the atoms of the starting compounds.

In recent years, we have worked constantly on the development of new tools and methodologies for bioactive compounds synthesized using green methodologies.26−28

In the present work, we describe a simple and excellent performance protocol for the synthesis of the Ugi reaction of four components in one pot by means of TSE without a catalyst and solvent.

Materials and Methods

General Procedure for Synthetic Ugi Reaction by Solvent-Free Twin Screw Extrusion

A mixture of aldehyde (0.2 mol), aromatic amine (0.2 mol), aromatic acid (0.2 mol), and isocyanide (0.2 moles) was taken in a glass mortar and gently mixed to ensure that the liquid reagents are adsorbed on solid compounds. The mixture was introduced manually into the extruder hopper. The extrusion was performed at various screw speeds in co-rotational mode and at different temperatures with the aim of optimizing the reaction. Care was taken to avoid overfilling the barrel. The extruded product was subsequently stirred while adding ice to the reaction, and the precipitated product was filtered using a vacuum pump. The precipitate was then washed with cold water, dried under vacuum, and recrystallized from ethanol to give the pure products.

The extruder employed in this study was a LechTech Scientific 26 mm twin screw extruder. The screws have a diameter of 26 mm and an L/D ratio of 40:1.

All the products are reported in the literature.29,30 The 1H-NMR and 13C-NMR spectra were recorded on a 400 MHz Bruker using TMS as the internal reference and CDCl3 as the solvent. Purity of a compound can be determined by TLC checking.

Compound 5a

M.P.: 71–73 °C; IR (KBr, νmax, cm–1): 3221, 3043, 2970, 1710, 1671, 779; 1H-NMR (400 MHz; CDCl3) δ: 7.34–7.25 (m, 7H), 7.21–7.10 (m, 3H), 7.02 (s, 5H), 6.11 (s, 1H), 5.80 (s, 1H), 1.40 (s, 9H); 13C-NMR (100 MHz; CDCl3) δ: 171.10, 168.71, 141.40, 137.00, 135.01, 130.18, 130.02, 129.48, 128.57, 128.45, 128.36, 128.31, 127.61, 127.01, 67.22, 51.68, 28.71.

Compound 5b

M.P.: 108–110 °C; IR (KBr, νmax, cm–1): 3198, 3021, 2983, 1712, 1669, 779; 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 7.21–6.75 (m, 14H), 4.95 (br, 1H), 4.45 (s, 2H), 4.21–4.15 (m, 2H), 3.75 (s, 6H), 3.54 (m, 2H), 1.85–1.77 (m, 1H), 1.44–1.36 (m, 2H), 0.80–0.75 (d, 6H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 173.40, 170.53, 158.91, 134.55, 130.31, 129.25, 129.01, 128.97, 128.80, 128.77, 128.65, 127.29, 114.22, 114.01, 56.55, 55.25, 48.25, 42.83, 41.31, 37.00, 25.14, 22.75, 22.40.

Compound 5c

M.P.: 78–80 °C; IR (KBr, νmax, cm–1): 3213, 3051, 2977, 1707, 1675, 777; 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 7.29–6.72 (m, 14H), 4.99 (br, 1H), 4.41 (m, 2H), 4.30–4.21 (m, 2H), 3.77 (s, 6H), 2.90–2.83 (m, 2H), 2.60–2.54 (m, 2H), 1.85–1.80 (m, 1H), 1.45–1.40 (m, 2H), 0.93–0.80 (m, 6H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 174.63, 170.64, 158.79, 140.87, 130.45, 129.32, 128.99, 128.81, 128.42, 128.40, 127.22, 126.18, 114.11, 114.01, 56.29, 55.26, 47.98, 42.81, 37.02, 35.71, 31.38, 25.14, 22.71, 22.43.

Compound 5d

M.P.: 124–126 °C; IR (KBr, νmax, cm–1): 3223, 3043, 2987, 1703, 1668, 780; 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 7.18–6.55 (m, 9H), 4.99 (br, 1H), 4.43 (s, 2H), 4.21–4.15 (m, 2H), 3.76 (s, 6H), 3.54 (m, 2H), 1.85–1.77 (m, 1H), 1.47 (s, 3H), 0.80–0.75 (d, 6H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 172.99, 170.71, 158.87, 158.81, 130.37, 129.33,129.29, 128.97, 127.31, 114.18, 114.00, 56.08, 55.23, 48.74, 42.78, 37.16, 25.18, 22.73, 22.41.

Compound 5e

M.P.: 93–95 °C; IR (KBr, νmax, cm–1): 3244, 3066, 2981, 1711, 1667, 781; 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 7.21–6.45 (m, 14H), 4.95 (br, 1H), 4.45 (s, 2H), 4.21–4.15 (s, 2H), 3.75 (s, 6H), 3.54 (s, 2H), 1.44–1.36 (d, 3H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 173.44, 170.55, 158.90, 134.55, 130.31, 129.25, 129.01, 128.97, 128.80, 128.79, 128.65, 56.55, 55.25, 48.25, 42.85, 41.31, 37.03, 25.14, 22.75, 20.40, 14.15.

Compound 5f

M.P.: 115–117 °C; IR (KBr, νmax, cm–1): 3210, 3033, 2980, 1708, 1666, 780; 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 7.19–6.75 (m, 14H), 4.99 (br, 1H), 4.47 (s, 2H), 4.17–4.15 (m, 2H), 3.73 (s, 6H), 3.55–3.52 (m, 2H), 1.92–1.88 (m, 1H), 1.53–1.50 (m, 1H), 1.25 (q, 3H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 173.34, 170.27, 158.92, 134.62, 130.35, 130.01, 129.32, 129.00, 128.73, 128.67, 127.27, 127.00, 126.98, 114.24, 114.01, 59.96, 55.27, 48.27, 42.78, 41.20, 21.70, 10.95.

Compound 5g

M.P.: 87–89 °C; IR (KBr, νmax, cm–1): 3222, 3013, 2982, 1703, 1669, 782; 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 7.20–6.67 (m, 15H), 4.98 (br, 1H), 4.44 (s, 2H), 4.19–4.13 (m, 2H), 3.77 (s, 3H), 3.54 (m, 2H), 1.85–1.77 (m, 1H), 1.44–1.36 (m, 2H), 0.80–0.75 (d, 6H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 173.43, 170.44, 158.91, 137.55, 134.53, 130.31, 129.25, 129.01, 128.97, 128.80, 128.77, 128.65, 127,39, 114.02, 56.55, 55.25, 48.25, 42.83, 37.03, 25.14, 22.75, 22.40.

Compound 5h

M.P.: 88–90 °C; IR (KBr, νmax, cm–1): 3245, 3033, 2980, 1709, 1674, 781; 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 7.18–6.67 (m, 10H), 5.00 (br, 1H), 4.23–4.13 (m, 2H), 3.72 (s, 3H), 3.61 (s, 2H), 3.25–3.02 (m, 2H), 1.85–1.77 (m, 1H), 1.44–1.36 (m, 2H), 1.14–0.98 (m, 11H), 0.80–0.75 (d, 6H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 172.72, 171.34, 158.82, 134.85, 130.48, 129.30, 129.00, 128.22, 126.94, 114.01, 55.84, 45.80, 42.76, 41.00, 36.74, 31.28, 29.96, 26.74, 24.81, 22.80, 22.51, 22.36, 13.92.

Compound 5i

M.P.: 105–107 °C, IR (KBr, νmax, cm–1): 3225, 3043, 2980, 1707, 1666, 781; 1H-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 7.20–6.66 (m, 10H), 5.00 (br, 1H), 4.32–4.04 (m, 2H), 3.71 (s, 3H), 3.65–3.55 (m, 2H), 1.89–1.06 (m, 14H), 0.80–0.75 (d, 6H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3) δ: 173.15, 169.48, 158.80, 134.53, 129.76, 129.12, 128.58, 127.12, 126.84, 114.08, 56.40, 55.15, 47.29, 41.28, 36.88, 32.72, 25.38, 25.05, 24.57, 22.61, 22.30.

Results and Discussion

The Ugi reaction is one of the most significant multicomponent reactions among aldehydes 1, amines 2, aromatic acid 3, and isocyanides 4, prompting us to study a new method such as mechanochemical reactions by means of TSE that gave products 5a–5i. We examined the influence of different (polar and nonpolar) solvents on the performance of this reaction. The results are presented in Table 1. Water was the best among the solvents tested, in view of the fact that it supplied product 5a with a yield of 66% (Table 1, entry 1).

Table 1. Solvent Effect on the Model Ugi Reactiona.

| entry | solvent | temperature (°C) | time (min) | yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | H2O | room temp. | 240 | 66 |

| 2 | MeOH | room temp. | 240 | 46 |

| 3 | EtOH | room temp. | 240 | 23 |

| 4 | acetonitrile | room temp. | 240 | 36 |

| 5 | DMF | room temp. | 240 | 21 |

| 6 | DCM | room temp. | 240 | 44 |

| 7 | benzene | room temp. | 240 | 35 |

| 8 | CCl4 | room temp. | 240 | 49 |

| 9 | solvent-free | room temp. | 240 | 63 |

| 10 | solvent-free | 60 | 100 | 69 |

| 11 | solvent-free | 80 | 100 | 72 |

| 12 | solvent-free | 100 | 60 | 77 |

Reaction conditions: benzaldehyde (1a, 0.5 mmol), aniline (2a, 0.5 mmol), benzoic acid (3a, 0.5 mmol), and tert-butyl isocyanide (4a, 0.5 mmol) gave isolated yields of 5a.

The reactions conducted in MeOH, EtOH, acetonitrile, DMF (N,N-dimethyl formamide), DCM (dichloromethane), benzene, and CCl4 (carbon tetrachloride) gave the yields of the appropriate products (Table 1, entries 2–8). The reaction was conducted without a solvent at room temperature (Table 1, entry 9) to establish the reference yields, with which it was possible to compare the yields obtained using our new process. As the temperature of the data obtained increased, it became evident that the best yields were attained in solvent-free conditions (Table 1, entries 10–12). We also sought to perform the reaction at temperatures above 100 °C; we noticed that a dark solid product was obtained. This is assumed to be caused by thermal degradation.

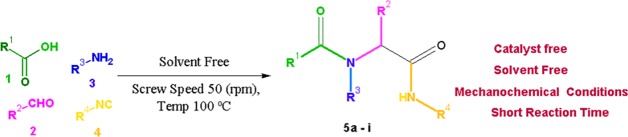

We then undertook reference reaction 5a (Scheme 1) by means of the mechanochemical method (TSE), primarily based on the hypothesis that the shear and compression of the reaction mass carried out between the screws would resolve the problem of bad mixing noticed in the batch reaction and therefore lead to higher product yields. In addition, in accordance with Le Chatelier’s principle of equilibrium, water obtained as a by-product of the Ugi reaction will evaporate during the extrusion process that caused the reaction to take place.

Scheme 1. Solvent- and Catalyst-Free Ugi Reaction 5a–5i by Means of Twin Screw Extrusion.

The reagent mixture was initially introduced into the extruder, and the extrusion was performed at 60 rpm and at room temperature (see Table 2). However, it was observed that the product only produced a low yield. Consequently, we started to increase the barrel temperature to 100 °C, at which point we achieved a 90% yield (Table 2, entry 5).

Table 2. Optimization of the Model Ugi Reaction by TSE.

| entry | temperature (°C) | screw speed (rpm) | yielda (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | room temp. | 60 | 16 |

| 2 | 60 | 60 | 51 |

| 3 | 80 | 60 | 68 |

| 4 | 90 | 60 | 76 |

| 5 | 100 | 60 | 90 |

| 6 | 100 | 40 | 84 |

| 7 | 100 | 50 | 93 |

Isolated yield.

This made us change the speed of the screw to assess its effect on product performance. At the optimal temperature of 100 °C, it was established that, by decreasing the speed of the screw, the total yield obtained would decrease (Table 2, entry 6) due to the lack of sufficient rotation and mixing. A higher screw speed also signifies that the reaction mixture remained in contact with the heated cylinder and was then exposed to high temperatures for a shorter time, thus giving submaximal yields (Table 2, entry 5). The optimal speed of the screw was 50 rpm (rounds per minute). At this rpm, the residence time was 15–20 min approximately. Therefore, it was determined that the magnitude and efficiency of the mixture with sufficient time at an elevated temperature had a direct influence on the yields of the product.

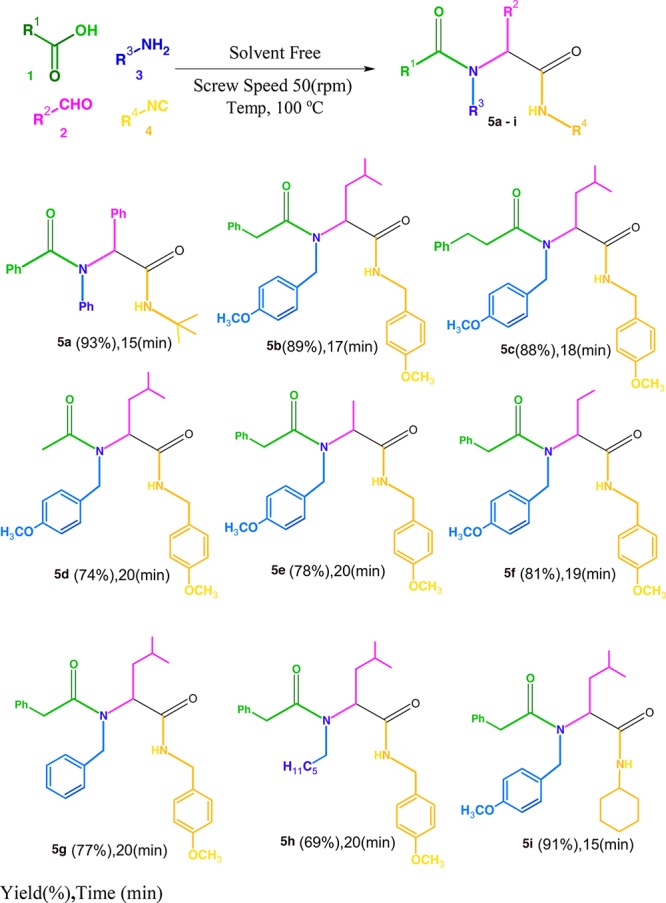

Subsequently, we also evaluated the substrate range for this process by using different aldehydes, amines, acids, and isocyanides to obtain Ugi products (Scheme 1). The reactions were performed using the optimum temperature and the speed of the screw obtained from previous reactions (Table 2, entry 7). From the data obtained, it can be concluded that the nature of the substituent does not have a significant effect on the product’s yield when the twin screw extruder is employed. The yields obtained by extrusion were also significantly higher than those achieved by means of the normal reaction without the corresponding solvent.

Conclusions

We have shown that multicomponent chemical synthesis can be converted into a continuous solvent-free process by using twin screw extrusion (TSE). The Ugi reaction was successfully performed in solvent-free conditions by using TSE. The yields obtained were higher than those attained with the classical techniques. Not only higher yields were obtained for the products, but also higher purity was achieved than those produced with the aforementioned methods. Therefore, it required less purification. This study reported an environmentally friendly process with a very short reaction time for organic synthesis.

Acknowledgments

This work is dedicated to Prof. Ahmed. M. M. Soliman on the occasion of his 60th birthday.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- James S. L.; Adams C. J.; Bolm C.; Braga D.; Collier P.; Friščić T.; Grepioni F.; Harris K. D. M.; Hyett G.; Jones W.; Krebs A.; Mack J.; Maini L.; Orpen A. G.; Parkin I. P.; Shearouse W. C.; Steed J. W.; Waddell D. C. Mechanochemistry: opportunities for new and cleaner synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 413–447. 10.1039/C1CS15171A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baláž P.; Achimovičová M.; Baláž M.; Billik P.; Cherkezova-Zheleva Z.; Criado J. M.; Delogu F.; Dutková E.; Gaffet E.; Gotor F. J.; Kumar R.; Mitov I.; Rojac T.; Senna M.; Streletskii A.; Wieczorek-Ciurowa K. Hallmarks of mechanochemistry: from nanoparticles to technology. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 7571–7637. 10.1039/c3cs35468g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takacs L. The historical development of mechanochemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 7649–7659. 10.1039/c2cs35442j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Tumanov I. A.; Michalchuk A. A. L.; Politov A. A.; Boldyreva E. V.; Boldyrev V. V. Inadvertent liquid assisted grinding: a key to “dry” organic mechano-co-crystallisation. CrystEngComm 2017, 19, 2830–2835. 10.1039/C7CE00517B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Leonardi M.; Villacampa M.; Menéndez J. C. Multicomponent mechanochemical synthesis. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 2042. 10.1039/C7SC05370C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Achar T. K.; Bose A.; Mal P. Mechanochemical synthesis of small organic molecules. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2017, 13, 1907–1931. 10.3762/bjoc.13.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Polindara-García L. A.; Juaristi E. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 2016, 1095–1102. 10.1002/ejoc.201501371. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira P. F. M.; Baron M.; Chamayou A.; André-Barrès C.; Guidetti B.; Baltas M. Solvent-free mechanochemical route for green synthesis of pharmaceutically attractive phenol-hydrazones. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 56736–56742. 10.1039/C4RA10489G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mashkouri S.; Naimi-Jamal M. R. Mechanochemical solvent-free and catalyst-free one-pot synthesis of pyrano[2,3-d]pyrimidine-2,4(1H,3H)-diones with quantitative yields. Molecules 2009, 14, 474–479. 10.3390/molecules14010474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- M’Hamed M. O. Ball Milling for Heterocyclic Compounds Synthesis in Green Chemistry: A Review. Synth. Commun. 2015, 45, 2511–2528. 10.1080/00397911.2015.1058396. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sayed T. H.; Aboelnaga A.; Hagar M. Ball Milling Assisted Solvent and Catalyst Free Synthesis of Benzimidazoles and Their Derivatives. Molecules 2016, 21, 1111. 10.3390/molecules21091111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma H.; Singh N.; Jang D. O. A ball-milling strategy for the synthesis of benzothiazole, benzimidazole and benzoxazole derivatives under solvent-free conditions. Green Chem. 2014, 16, 4922–4930. 10.1039/C4GC01142B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martins M. A. P.; Frizzo C. P.; Moreira D. N.; Buriol L.; Machado P. Solvent-Free Heterocyclic Synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 4140–4182. 10.1021/cr9001098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández J. G.; Juaristi E. Green Synthesis of α,β- and β,β-Dipeptides under Solvent-Free Conditions. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 7107–7111. 10.1021/jo101159a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Declerck V.; Nun P.; Martinez J.; Lamaty F. Solvent-free synthesis of peptides. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 9318–9321. 10.1002/anie.200903510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G.-W. Mechanochemical organic synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 7668–7700. 10.1039/c3cs35526h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boldyreva E. Mechanochemistry of inorganic and organic systems: what is similar, what is different?. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 7719–7738. 10.1039/c3cs60052a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford D. E.; Miskimmin C. K. G.; Albadarin A. B.; Walker G.; James S. L. Organic synthesis by Twin Screw Extrusion (TSE): continuous, scalable and solvent-free. Green Chem. 2017, 19, 1507–1518. 10.1039/C6GC03413F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford D. E.; Miskimmin C. K.; Cahir J.; James S. L. Continuous multi-step synthesis by extrusion – telescoping solvent-free reactions for greater efficiency. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 13067–13070. 10.1039/C7CC06010F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhumal R. S.; Kelly A. L.; York P.; Coates P. D.; Paradkar A. Cocrystalization and Simultaneous Agglomeration Using Hot Melt Extrusion. Pharm. Res. 2010, 27, 2725. 10.1007/s11095-010-0273-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford D.; Casaban J.; Haydon R.; Giri N.; McNally T.; James S. L. Synthesis by extrusion: continuous, large-scale preparation of MOFs using little or no solvent. Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 1645–1649. 10.1039/C4SC03217A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford D. E.; Wright L. A.; James S. L.; Abbott A. P. Efficient continuous synthesis of high purity deep eutectic solvents by twin screw extrusion. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 4215. 10.1039/C5CC09685E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Cioc R. C.; Ruijter E.; Orru R. V. A. Multicomponent reactions: advanced tools for sustainable organic synthesis. Green Chem. 2014, 16, 2958–2975. 10.1039/C4GC00013G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Carvalho R. B.; Joshi S. V. Solvent and catalyst free synthesis of 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones/thiones by twin screw extrusion. Green Chem. 2019, 21, 1921–1924. 10.1039/C9GC00036D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ruijter E.; Scheffelaar R.; Orru R. V. A. Multicomponent reaction design in the quest for molecular complexity and diversity. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 6234–6246. 10.1002/anie.201006515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardila-Fierro K. J.; Crawford D. E.; Körner A.; James S. L.; Bolm C.; Hernández J. G. Papain-catalysed mechanochemical synthesis of oligopeptides by milling and twin-screw extrusion: application in the Juliá–Colonna enantioselective epoxidation. Green Chem. 2018, 20, 1262–1269. 10.1039/C7GC03205F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dömling A. Recent Developments in Isocyanide Based Multicomponent Reactions in Applied Chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2006, 106, 17. 10.1021/cr0505728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boger D. L.; Desharnais J.; Capps K. Solution-phase combinatorial libraries: modulating cellular signaling by targeting protein-protein or protein-DNA interactions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2003, 42, 4138. 10.1002/anie.200300574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a El-Remaily M. A. E. A. A. A.; Hamad H. A. Synthesis and characterization of highly stable superparamagnetic CoFe2O4 nanoparticles as a catalyst for novel synthesis of thiazolo [4,5-b]quinolin-9-one derivatives in aqueous medium. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 2015, 404, 148–155. [Google Scholar]; b El-Remaily M. A. E. A. A. A.; Abu-Dief A. M. CuFe2O4 nanoparticles: an efficient heterogeneous magnetically Separable catalyst for Synthesis of some novel propynyl-1H imidazoles derivatives. Tetrahedron 2015, 71, 2579–2584. 10.1016/j.tet.2015.02.057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c El-Remaily M. A. E. A. A. A. Synthesis of Pyranopyrazoles Using Magnetic Fe3O4 Nanoparticles as Efficient and Reusable Catalyst. Tetrahedron 2014, 70, 2971–2975. 10.1016/j.tet.2014.03.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Mohamed S. K.; Soliman A. M.; El-Remaily M. A. A.; Abdel-Ghany H. Eco-Friendly Synthesis of Pyrimidine and Dihydropyrimidinone Derivatives under Solvent Free Condition and their Anti-microbial Activity. Chem. Sci. J. 2013, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- a El-Remaily M. A. E. A. A. A. Bismuth Triflate: A highly efficient catalyst for the Synthesis of bio-active coumarin compounds via one-pot multi-component reaction. Chin. J. Catal. 2015, 36, 1124–1130. 10.1016/S1872-2067(14)60308-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b El-Remaily M. A. E. A. A. A.; Mohamed S. K. Eco- Friendly synthesis of guanidinyltetrazole compounds and 5-substituted 1H-tetrazoles in water under microwave irradiation. Tetrahedron 2014, 70, 270–275. 10.1016/j.tet.2013.11.069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Soliman A. M.; Mohamed S. K.; El-Remaily M. A. A.; Abdel-Ghany H. Synthesis and biological activity of Dihydroimidazole and 3,4-dihydrobenzo[4,5]imidazo[1,2-a][1,3,5] triazins. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 47, 138–142. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2011.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d El-Remaily M. A. E. A. A. A.; Mohamed S. K.; Soliman A. M. M.; Abdel-Ghany H. Synthesis of Dihydroimidazole Derivatives under Solvent Free Condition and Their Antibacterial Evaluation. Biochem. Physiol. 2014, 03, 2. 10.4172/2168-9652.1000139. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a El-Remaily M. A. E. A. A. A.; Elhady O. M. Iron (III)-porphyrin Complex FeTSPP as an efficient catalyst for synthesis of tetrazole derivatives via [2 + 3]cycloaddition reaction in aqueous medium. Appl. Organometal. Chem. 2019, 33, 4989. 10.1002/aoc.4989. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b El-Remaily M. A. E. A. A. A.; Abu-Dief A. M.; Elhady O. Green synthesis of TiO2 nanoparticles as an efficient heterogeneous catalyst with high reusability for synthesis of 1,2-dihydroquinoline derivatives. Appl. Organometal. Chem. 2019, 33, 5005. 10.1002/aoc.5005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c El-Remaily M. A. E. A. A. A.; Elhady O. M. Cobalt (III)-porphyrin Complex (CoTCPP) as an efficient and recyclable homogeneous catalyst for the synthesis of tryptanthrin in aqueous media. Tetrahedron Lett. 2016, 57, 435–437. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2015.12.052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d El-Remaily M. A. E. A. A. A.; Abu-Dief A. M.; El-Khatib R. M. A robust Synthesis and Characterization of Superparamagnetic CoFe2O4 Nanoparticles as an Efficient and Reusable Catalyst for Synthesis of some Heterocyclic rings. Appl. Organometal. Chem 2016, 30, 1022–1029. 10.1002/aoc.3536. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ingold M.; Colella L.; Dapueto R.; López G. V.; Porcal W. Ugi Four-component Reaction (U-4CR) Under Green Conditions Designed for Undergraduate Organic Chemistry Laboratories. World J. Chem. Educ. 2017, 5, 153–157. 10.12691/wjce-5-5-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Madej A.; Paprocki D.; Koszelewski D.; Dobrowolska A. Ż.; Brzozowska A.; Walde P.; Ostaszewski R. Efficient Ugi reactions in an aqueous vesicle system. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 33344. 10.1039/C7RA03376A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]