Abstract

Background

Aerobic glycolysis is a hallmark of metabolic reprogramming that contributes to tumor progression. However, the mechanisms regulating expression of glycolytic genes in neuroblastoma (NB), the most common extracranial solid tumor in childhood, still remain elusive.

Methods

Crucial transcriptional regulators and their downstream glycolytic genes were identified by integrative analysis of a publicly available expression profiling dataset. In vitro and in vivo assays were undertaken to explore the biological effects and underlying mechanisms of transcriptional regulators in NB cells. Survival analysis was performed by using Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank test.

Results

Hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 alpha (HNF4A) and its derived long noncoding RNA (HNF4A-AS1) promoted aerobic glycolysis and NB progression. Gain- and loss-of-function studies indicated that HNF4A and HNF4A-AS1 facilitated the glycolysis process, glucose uptake, lactate production, and ATP levels of NB cells. Mechanistically, transcription factor HNF4A increased the expression of hexokinase 2 (HK2) and solute carrier family 2 member 1 (SLC2A1), while HNF4A-AS1 bound to heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein U (hnRNPU) to facilitate its interaction with CCCTC-binding factor (CTCF), resulting in transactivation of CTCF and transcriptional alteration of HNF4A and other genes associated with tumor progression. Administration of a small peptide blocking HNF4A-AS1-hnRNPU interaction or lentivirus-mediated short hairpin RNA targeting HNF4A-AS1 significantly suppressed aerobic glycolysis, tumorigenesis, and aggressiveness of NB cells. In clinical NB cases, high expression of HNF4A-AS1, hnRNPU, CTCF, or HNF4A was associated with poor survival of patients.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that therapeutic targeting of HNF4A-AS1/hnRNPU/CTCF axis inhibits aerobic glycolysis and NB progression.

Keywords: Hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 alpha antisense RNA 1, Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein U, CCCTC-binding factor, Aerobic glycolysis, Tumor progression, Neuroblastoma

Background

Neuroblastoma (NB) is the most common extracranial solid tumor in childhood, and accounts for 15% of pediatric cancer deaths [1]. For high-risk NB, the survival rate of patients still remains low despite multimodal therapy [1]. To maintain tumorigenesis and aggressiveness, tumor cells exert a unique metabolic preference for converting glucose into lactate even in the presence of sufficient oxygen, a process known as “Warburg effect” or “aerobic glycolysis” [2, 3]. Activation of oncogenes or inactivation of tumor suppressors contributes to glycolytic gene expression in tumor cells. For example, c-Myc enhances the alternative splicing of pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2) [4], while inactivation of p53 facilitates the transcription of solute carrier family 2 member 3 (SLC2A3) [5]. Inhibition of aerobic glycolysis by small organic molecules, such as 3-bromopyruvate or 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG), exhibits therapeutic potential for tumors [6, 7]. Thus, it is important to investigate the regulators of aerobic glycolysis for improving therapeutic efficiencies of NB.

Long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs), one type of endogenous RNA longer than 200 nucleotides (nt), play essential roles in NB progression [8–10]. For example, high expression of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A/alternative reading frame intron 2 lncRNA (CAI2) is associated with poor survival of NB patients [8]. In addition, Ets-1 promoter-associated noncoding RNA promotes NB progression through binding with heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K (hnRNPK) and stabilizing β-catenin [9]. Meanwhile, loss of tumor suppressive neuroblastoma-associated transcript-1 (NBAT-1) contributes to NB progression by increasing proliferation and reducing differentiation of neuronal precursors [10]. However, the roles of lncRNAs in aerobic glycolysis during NB progression remain elusive.

In this study, we identify hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 alpha (HNF4A) as a transcription factor facilitating aerobic glycolysis and NB progression, and reveal that HNF4A antisense RNA 1 (HNF4A-AS1), a lncRNA derived from upstream region of HNF4A, is associated with poor outcome of NB. HNF4A-AS1 promotes aerobic glycolysis, growth, and aggressiveness of NB cells by binding to heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein U (hnRNPU) and facilitating its interaction with CCCTC-binding factor (CTCF), resulting in transactivation of CTCF and transcriptional alteration of HNF4A and other genes associated with tumor progression, indicating the crucial roles of HNF4A-AS1/hnRNPU/CTCF axis in NB progression.

Methods

Cell culture

Human non-transformed mammary epithelial MCF 10A (CRL-10317) cells, embryonic kidney HEK293T (CRL-3216) cells, NB cell lines SH-SY5Y (CRL-2266), SK-N-AS (CRL-2137), BE(2)-C (CRL-2268), and IMR-32 (CCL-127) were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD). Cell lines were authenticated by short tandem repeat profiling, and used within 6 months after resuscitation of frozen aliquots. Mycoplasma contamination was regularly examined with Lookout Mycoplasma PCR Detection Kit (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, Grand Island, NY), and treated with insulin or 2-DG (Sigma).

RNA isolation, RT-PCR, and real-time quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR)

Nuclear, cytoplasmic, and total RNA of tissues and cell lines were isolated using RNA Subcellular Isolation Kit (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA) or RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA). Total RNA of each serum was extracted using TRIzol LS reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Reverse transcription reactions were conducted with Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). PCR and real-time PCR were performed with Taq PCR Master Mix or SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and primers (Additional file 1: Table S1). For real-time qRT-PCR assay, the transcript levels were analyzed by 2−ΔΔCt method.

Western blot

Tissue or cellular protein was extracted with 1 × cell lysis buffer (Promega, Madison, WI). Western blot was performed as previously described [9, 11–15], with antibodies for HNF4A (ab181604), hexokinase 2 (HK2, ab104836), solute carrier family 2 member 1 (SLC2A1, ab40084), v-myc avian myelocytomatosis viral oncogene neuroblastoma-derived homolog (MYCN, ab16898), hnRNPU (ab10297), CTCF (ab188408), clusterin (CLU, ab69644), C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4, ab124824), trophoblast glycoprotein (TPBG, ab129058), uveal autoantigen with coiled-coil domains and ankyrin repeats (UACA, ab99323), FLAG (ab125243), Myc (ab9106), glutathione S-transferase (GST, ab19256), histone H3 (ab5103), or β-actin (ab6276, Abcam Inc., Cambridge, MA).

Luciferase reporter assay

Human HNF4A-AS1 (-1418/+45) or HNF4A (-606/+128) promoter was amplified from genomic DNA by PCR (Additional file 1: Table S2) and subcloned into pGL3-Basic (Promega). Mutation of MYCN or CTCF binding site was performed with GeneTailorTM Site-Directed Mutagenesis System (Invitrogen) and primers (Additional file 1: Table S2). Luciferase reporters for transcription factors were established by inserting oligonucleotides containing four canonical binding sites (Additional file 1: Table S2) into pGL3-Basic (Promega). Human p53 luciferase reporter was obtained from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA). Dual-luciferase assay was performed as previously described [9, 11–13], using a luminometer (Lumat LB9507, Berthold Tech., Bad Wildbad, Germany).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay was performed according to instructions of EZ-ChIP kit (Upstate Biotechnology, Temacula, CA) [9, 11, 14], using antibodies specific for HNF4A (ab181604), MYCN (ab16898), CTCF (ab188408), RNA polymerase II (RNA Pol II, ab5131), histone H3 lysine 4 trimethylation (H3K4me3, ab8580), and histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation (H3K27me3, ab6002). Real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed with SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) and primers (Additional file 1: Table S1). Immunoprecipitated DNA was normalized to input DNA, using isotype IgG as a negative control.

Gene over-expression and knockdown

Human HNF4A and MYCN expression vectors were provided by Dr. David Martinez Selva [16] and Dr. Arturo Sala [17], respectively. Human HNF4A-AS1 cDNA (648 bp), hnRNPU cDNA (2478 bp), CTCF cDNA (2184 bp), and their truncations were amplified from NB tissues (Additional file 1: Table S2) and subcloned into pcDNA3.1 (Invitrogen), pCMV-3Tag-1C, pCMV-N-Myc, and pGEX-6P-1 (Addgene, Cambridge, MA), respectively. Mutation of short hairpin RNA (shRNA)-targeting site of HNF4A-AS1 or hnRNPU RGG residues was performed with GeneTailorTM Site-Directed Mutagenesis System (Invitrogen) and primers (Additional file 1: Table S2). Oligonucleotides encoding shRNAs specific for HNF4A, HK2, SLC2A1, MYCN, HNF4A-AS1, hnRNPU, or CTCF (Additional file 1: Table S3) were subcloned into GV298 (Genechem Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China). Single guide RNAs (sgRNAs) targeting downstream region of HNF4A-AS1 transcription start site (Additional file 1: Table S3) were inserted into dCas9-BFP-KRAB (Addgene). Stable cell lines were screened by administration of neomycin or puromycin (Invitrogen).

Rescue of target gene expression

To rescue gene expression altered by hnRNPU, CTCF, or HNF4A knockdown, tumor cells were transfected with HNF4A-AS1 vector. To restore target gene expression induced by over-expression of hnRNPU, CTCF, or HNF4A, shRNA specific for HNF4A-AS1 (Additional file 1: Table S3) was transfected into tumor cells with Genesilencer Transfection Reagent (Genlantis, San Diego, CA). Empty vector and sh-Scb were applied as controls (Additional file 1: Table S3).

Lentiviral packaging

Lentiviral vectors were co-transfected with packaging plasmids psPAX2 and pMD2G (Addgene) into HEK293T cells. Infectious lentivirus was filtered through 0.45 μm PVDF filters, and concentrated 100-fold by ultracentrifugation (2 h at 120,000g). Infectious lentivirus was harvested at 36 and 60 h after transfection and filtered through 0.45 μm PVDF filters. Recombinant lentivirus was concentrated 100-fold by ultracentrifugation (2 h at 120,000g). Lentivirus-containing pellet was dissolved in phosphate buffer saline (PBS) and injected in mice within 48 h.

Rapid amplification of cDNA ends assay

Total RNA was isolated from BE(2)-C cells to prepare rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE)-ready cDNA using SMARTer RACE cDNA Amplification Kit (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA), which was further amplified by PCR primers and nested PCR primers (Additional file 1: Table S1).

Northern blot

The 254-bp probe was in vitro transcribed using DIG Labeling Kit (MyLab Corporation, Beijing, China) and T7 RNA polymerase, and treated with RNase-free DNase I. For Northern blot, 20 μg of total RNA was separated on 3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid (MOPS)-buffered 2% (w/v) agarose gel containing 1.2% (v/v) formaldehyde under denaturing conditions for 4 h at 80 V, and transferred to Hybond-N+ membrane (Pall Corp., Port Washington, NY). Prehybridization was carried out at 65 °C for 30 min in DIG Easy Hyb solution (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). Hybridization was performed at 65 °C for 16–18 h. Blots were washed stringently, detected by anti-digoxigenin (DIG) antibody, and recorded on X-ray films with chemiluminescence substrate CSPD (Roche).

RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization

Antisense or sense RNA probe for HNF4A-AS1 was in vitro transcribed with Biotin RNA Labeling Mix (Roche) and T7 RNA polymerase. Cells were seeded on coverslips, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min, and incubated with 40 nmol·L−1 fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) probe in hybridization buffer (100 mg/ml dextran sulfate, 10% formamide in 2 × SSC) at 80 °C for 2 min. Hybridization was performed at 55 °C for 2 h, with or without RNase A (20 μg) treatment. Cells were incubated with streptavidin-conjugated fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), with nuclei counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI).

Fluorescence immunocytochemical staining

Cells were plated on coverslip, incubated with 5% milk for 1 h, and treated with antibody specific for hnRNPU (ab10297, Abcam Inc., 1:300 dilution) at 4 °C overnight. Then, coverslips were treated with Alexa Fluor 594 goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:1000 dilution) and stained with DAPI (300 nmol·L−1). The images were photographed under a Nikon A1Si Laser Scanning Confocal Microscope (Nikon Instruments Inc, Japan).

RNA sequencing

Total RNA of tumor cells (1 × 106) was isolated using TRIzolTM reagent (Life Technologies, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD). Library preparation and transcriptome sequencing on an Illumina HiSeq X Ten platform were carried out at Novogene Bioinformatics Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China) to generate 100-bp paired-end reads. HTSeq v0.6.0 was applied in counting the numbers of read mapping to each gene, and fragments per kilobase of transcript per million fragments mapped (FPKM) of each gene were calculated. Sequencing results have been deposited in GEO database (accession code GSE143896).

Biotin-labeled RNA pull-down and mass spectrometry analysis

Biotin-labeled RNA probes for HNF4A-AS1 truncations were in vitro transcribed as described above. Nuclear extracts were harvested, resuspended in freshly prepared proteolysis buffer, and incubated with biotin-labeled RNA (10 pmol) and streptavidin-agarose beads (Invitrogen) for 1 h. Precipitated components were separated using SDS-PAGE, followed by Coomassie blue staining or Western blot. Differential bands were harvested for mass spectrometry analysis (Wuhan Institute of Biotechnology, Wuhan, China) [9].

Cross-linking RNA immunoprecipitation

Tumor cells (1 × 108) were ultraviolet light cross-linked at 254 nm (200 J/cm2) in PBS and collected by scraping [9, 13]. RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) assay was performed with Magna RIPTM RNA-Binding Protein Immunoprecipitation Kit (Millipore, Bedford, MA), using antibodies for hnRNPU (ab10297) or hnRNPK (ab39975, Abcam Inc.). Co-precipitated RNAs were detected by RT-PCR or real-time quantitative qRT-PCR with primers (Additional file 1: Table S1). Total RNAs (input) and isotype antibody (IgG) were applied as controls.

In vitro binding assay

A series of hnRNPU truncations were amplified from NB tissues (Additional file 1: Table S2), subcloned into pGEX-6P-1 (Addgene), and transformed into E. coli to produce GST-tagged hnRNPU [9, 11]. HNF4A-AS1 cRNA was in vitro transcribed with TranscriptAid T7 High Yield Transcription Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA), and incubated with GST-tagged hnRNPU. HnRNPU–RNA complexes were pulled down using GST beads (Sigma). Protein was detected by SDS-PAGE and western blot, while RNA was measured by RT-PCR with primers (Additional file 1: Table S1).

RNA electrophoretic mobility shift assay

Biotin-labeled RNA probes for HNF4A-AS1 truncations were prepared as described above. RNA electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) using nuclear extracts or recombinant hnRNPU protein was performed using LightShift Chemiluminescent RNA EMSA Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Co-immunoprecipitation assay

Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) was performed as previously described [9, 12, 14], with antibodies specific for hnRNPU (ab10297), CTCF (ab188408), FLAG (ab125243), or Myc (ab9106, Abcam Inc.). Bead-bound proteins were released and analyzed by Western blot.

Bimolecular fluorescence complementation assay

Human hnRNPU cDNA (2478 bp) and CTCF cDNA (2184 bp) were subcloned into bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) vectors pBiFC-VN173 and pBiFC-VC155 (Addgene) and co-transfected into tumor cells with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) for 24 h. Fluorescence emission was observed under a confocal microscope, using excitation and emission wavelengths of 488 and 500 nm, respectively [14].

Design and synthesis of inhibitory peptides

Inhibitory peptides for blocking interaction between HNF4A-AS1 and hnRNPU were designed. The 11 amino acid long peptide (YGRKKRRQRRR) from Tat protein transduction domain served as a cell-penetrating peptide. Thus, inhibitory peptides were chemically synthesized by linking with biotin-labeled cell-penetrating peptide at N-terminus and conjugating with FITC at C-terminus (ChinaPeptides Co. Ltd, Shanghai, China), with purity larger than 95%.

Biotin-labeled peptide pull-down assay

Cellular proteins were isolated using 1 × cell lysis buffer (Promega), and incubated with biotin-labeled peptide and streptavidin-agarose at 4 °C. Then, incubation of cell lysates with streptavidin-agarose was undertaken at 4 °C for 2 h. Beads were extensively washed, and RNA pulled down was measured by RT-PCR or real-time qRT-PCR.

Aerobic glycolysis and seahorse extracellular flux assays

Cellular glucose uptake, lactate production, and ATP levels were detected as previously described [18]. Extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) and oxygen consumption rate (OCR) were measured in XF media under basal conditions and in response to glucose (10 mmol·L−1), oligomycin (2 μmol·L−1), and 2-deoxyglucose (100 mmol·L−1), using a Seahorse Biosciences XFe24 Flux Analyzer (North Billerica, MA).

Cellular viability, growth, and invasion assays

The 2-(4,5-dimethyltriazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT; Sigma) colorimetric [9, 19], soft agar [9, 11, 12, 14, 20], and matrigel invasion [9, 11, 12, 14, 20, 21] assays for measuring the viability, growth, and invasion capability of tumor cells were conducted as previously described.

In vivo tumorigenesis and aggressiveness assays

All animal experiments were carried out in accordance with NIH Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and approved by the Animal Care Committee of Tongji Medical College (approval number, Y20080290). In vivo tumor growth and experimental metastasis studies were performed with blindly randomized 4-week-old female BALB/c nude mice (n = 5 per group) as previously described [9, 11, 12, 14, 20]. For in vivo therapeutic studies, tumor cells (1 × 106 or 0.4 × 106) stably expressing red fluorescent protein were injected into dorsal flanks or tail vein of nude mice, respectively. One week later, mice were blindly randomized and treated by tail vein injection of synthesized cell-penetrating peptide [22] or lentivirus-mediated shRNA (1 × 107 plaque-forming units in 100 μl PBS), and imaged using In-Vivo Xtreme II small animal imaging system (Bruker Corporation, Billerica, MA).

Patient tissue samples

The Institutional Review Board of Tongji Medical College approved human tissue study (approval number, 2011-S085). All procedures were carried out in accordance with guidelines set forth by Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all legal guardians of patients. Patients with a history of preoperative chemotherapy or radiotherapy were excluded. Human normal dorsal root ganglia tissues were collected from therapeutic abortion. All fresh specimens were frozen in liquid nitrogen, validated by pathological diagnosis, and stored at − 80 °C until use. Blood samples were centrifuged at 2000 r/min for 10 min at 4 °C, and serum was collected and stored at − 80 °C until further processing.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical staining and quantitative evaluation were performed as previously described [9, 11, 12, 14, 20], with antibody specific for Ki-67 (ab92742, Abcam Inc.; 1:100 dilution) or CD31 (ab28364, Abcam Inc.; 1:100 dilution). The degree of positivity was measured according to percentage of positive tumor cells.

Statistical analysis

All data were shown as mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.). Cutoff values were determined by average gene expression levels. Student’s t test, analysis of variance (ANOVA), and χ2 analysis were applied to compare difference in tumor cells or tissues. Fisher’s exact test was applied to analyze statistical significance of overlap between two gene lists. Log-rank test was used to assess survival difference. All statistical tests were two-sided and considered statistically significant when false discovery rate (FDR)-corrected P values were less than 0.05.

Results

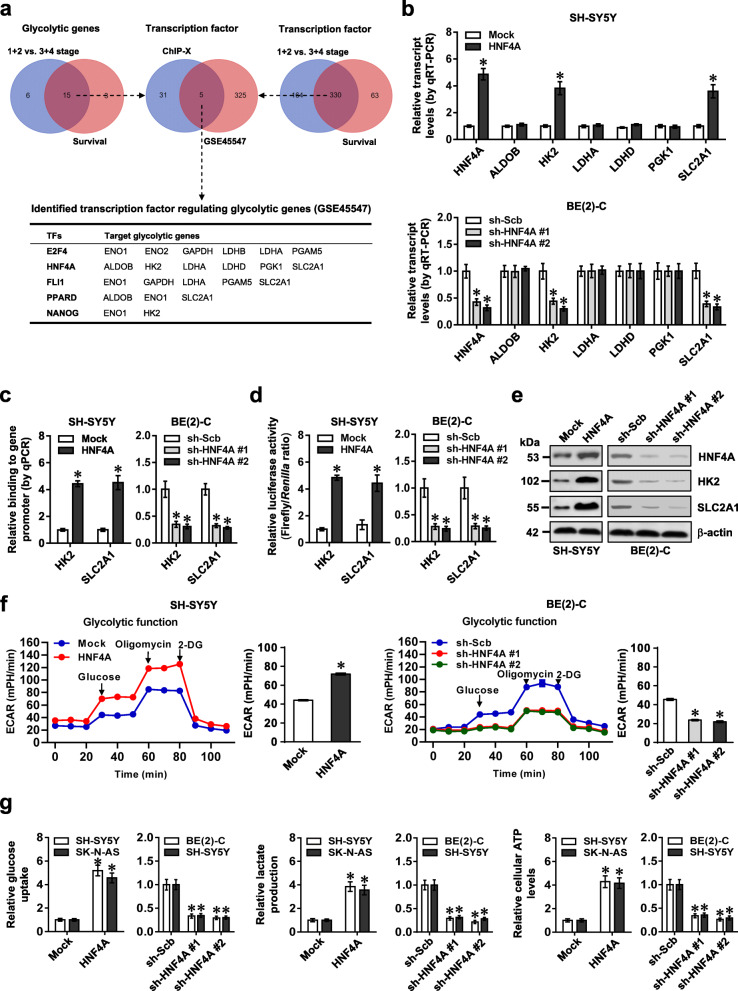

Transcription factor HNF4A facilitates glycolytic gene expression and glycolysis of NB cells

Comprehensive analysis of a public dataset (GSE45547) [23] of 649 NB cases identified 21 and 18 glycolytic genes differentially expressed (P < 0.05) in NB specimens with varied international neuroblastoma staging system (INSS) stages or associated with survival of patients, respectively (Fig. 1a). Over-lapping analysis (P < 0.001) revealed that 15 glycolytic genes were consistently associated with advanced INSS stages and survival of NB (Fig. 1a). Similarly, we found 330 transcription factors consistently associated with these clinical features of NB cases, which were subjective to further over-lapping analysis with 36 transcription factors regulating 15 glycolytic genes analyzed by ChIP-X program [24]. The results indicated that 5 transcription factors might regulate the expression of glycolytic genes (Fig. 1a). Among them, the activity of HNF4A was most significantly elevated in SH-SY5Y cells in response to treatment with insulin, an inducer of aerobic glycolysis [25] (Additional file 1: Figure S1a). In NB tissues and cell lines, P1 promoter-derived HNF4A transcripts were upregulated, while P2-HNF4A was expressed at very low levels (Additional file 1: Figure S1b). By using isoform-specific primers, endogenous expression of α1-α3 isoforms (especially high levels of α1 isoform) of P1-HNF4A (referred as HNF4A) was noted in NB tissues, without detectable levels of α4-α6 isoforms (Additional file 1: Figure S1c). In addition, high HNF4A protein levels were noted in NB cell lines (Additional file 1: Figure S1b). Stable over-expression or knockdown of HNF4A increased and decreased the levels of HK2 or SLC2A1, but not of fructose-bisphosphate B (ALDOB), lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA), lactate dehydrogenase D (LDHD), or phosphoglycerate kinase 1 (PGK1), in SK-N-AS, SH-SY5Y, and BE(2)-C cells (representing low, middle, or high HNF4A expression) (Fig. 1b and Additional file 1: Figure S1d). Ectopic expression or knockdown of HNF4A increased and decreased its enrichment on promoters, resulting in facilitated and reduced promoter activity and expression of HK2 and SLC2A1 in NB cells, respectively (Fig. 1c–e and Additional file 1: Figure S1e-g). ECAR, an indicator of glycolysis, was increased in SH-SY5Y cells with stable over-expression of HNF4A, while knockdown of HNF4A attenuated the glycolytic process in BE(2)-C cells (Fig. 1f). Meanwhile, OCR was reduced and increased in NB cells with stable over-expression or knockdown of HNF4A (Additional file 1: Figure S1h), accompanied by increased and decreased glucose uptake, lactate production, and ATP levels, respectively (Fig. 1g). In a public NB dataset (GSE45547), higher levels of HNF4A (P = 1.2 × 10−5), HK2 (P = 1.6 × 10−20), and SLC2A1 (P = 1.7 × 10−2) were noted in tumor tissues with advanced stages (Additional file 1: Figure S1i). Notably, knockdown of HK2 or SLC2A1 prevented the increased growth and invasion of SH-SY5Y cells induced by HNF4A over-expression (Additional file 1: Figure S2a-c). In an independent cohort of 42 primary NB tissues, there was a positive expression correlation between HNF4A and HK2 or SLC2A1 (Additional file 1: Figure S2d). High expression of HNF4A, HK2, or SLC2A1 was associated with poor survival of patients with NB, breast cancer, colon cancer, glioblastoma, lung cancer, ovarian cancer, or prostate cancer (Additional file 1: Figure S2e and Figure S3). These findings indicated that HNF4A facilitated glycolytic gene expression and glycolysis of NB cells.

Fig. 1.

Transcription factor HNF4A facilitates glycolytic gene expression and glycolysis of NB cells. a Venn diagram indicating the identification of glycolytic genes (upper left panel) and transcription factors (upper right panel) differentially expressed (P < 0.05) in INSS stages and associated with patients’ survival in 649 NB cases (GSE45547), and over-lapping analysis with potential transcription factors regulating glycolytic genes revealed by ChIP-X program (upper middle panel). The lower panel showing potential transcription factors regulating expression of glycolytic genes. b Real-time qRT-PCR assay (normalized to β-actin, n = 4) revealing the expression of HNF4A, ALDOB, HK2, LDHA, LDHD, PGK1, or SLC2A1 in SH-SY5Y and BE(2)-C cells stably transfected with empty vector (mock), HNF4A, scramble shRNA (sh-Scb), or sh-HNF4A. c ChIP and qPCR assays indicating the binding of HNF4A to promoters of HK2 and SLC2A1 in SH-SY5Y and BE(2)-C cells stably transfected with mock, HNF4A, sh-Scb, or sh-HNF4A (n = 4). d and e Dual-luciferase (d) and Western blot (e) assays showing the promoter activity and expression levels of HK2 and SLC2A1 in SH-SY5Y and BE(2)-C cells stably transfected with mock, HNF4A, sh-Scb, or sh-HNF4A (n = 4). f Seahorse tracing curves (left panel) and ECAR bars (right panel) of SH-SY5Y and BE(2)-C cells stably transfected with mock, HNF4A, sh-Scb, or sh-HNF4A (n = 4), and those treated with glucose (10 mmol·L−1), oligomycin (2 μmol·L−1), or 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG, 50 mmol·L−1) at indicated points. g The glucose uptake, lactate production, and ATP levels in SH-SY5Y, SK-N-AS, and BE(2)-C cells stably transfected with mock, HNF4A, sh-Scb, or sh-HNF4A (n = 4). Fisher’s exact test for over-lapping analysis in a. Student’s t test and ANOVA compared the difference in b–d, f and g. *P < 0.05 vs. mock or sh-Scb. Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m. (error bars) and representative of three independent experiments in b–g

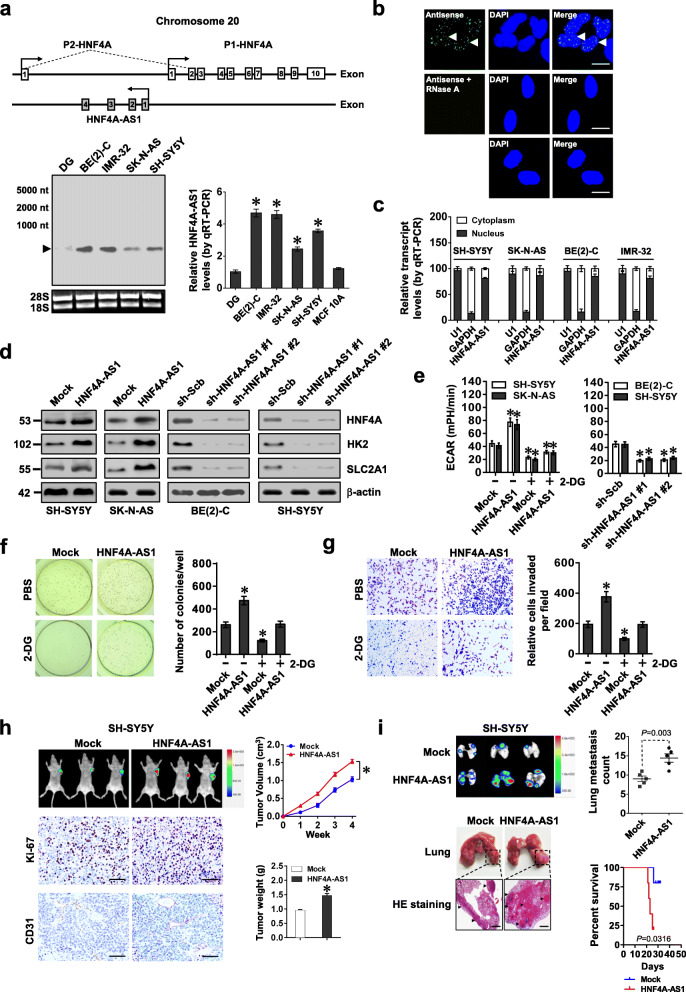

HNF4A-AS1 promotes aerobic glycolysis and NB progression

Mining of UCSC Genome Browser revealed that HNF4A-AS1, an antisense lncRNA consisting of four exons, located at upstream of P1-HNF4A (Fig. 2a). The existence of 648-nt HNF4A-AS1 transcript was validated by 5′- and 3′-RACE assays (Additional file 1: Figure S4a). High HNF4A-AS1 levels were observed in BE(2)-C, IMR-32, SK-N-AS, and SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. 2a), mainly localizing in the nucleus (Fig. 2b, c). Meanwhile, Coding Potential Assessment Tool (CPAT) [26] revealed low protein-coding potential (probability value = 0.0398) of HNF4A-AS1. In 42 primary NB cases (Additional file 1: Table S4), higher HNF4A-AS1 levels were observed in tumor tissues and serum of patients with poor differentiation (P = 0.0013 and P = 0.0097), advanced INSS stages (P = 0.0051 and P = 0.0016), or MYCN amplification (P < 0.0001 and P = 0.0009, Additional file 1: Figure S4b). To explore the potential effects of MYCN on HNF4A-AS1 expression, expression vector or shRNA of MYCN was transfected into SH-SY5Y and BE(2)-C cells, resulting in its over-expression or knockdown, respectively (Additional file 1: Figure S4c). Dual-luciferase assay indicated the increased and decreased HNF4A-AS1 promoter activity in NB cells transfected with MYCN or sh-MYCN, which was abolished by mutation of MYCN-binding site (Additional file 1: Figure S4d). Ectopic expression or knockdown of MYCN increased and decreased its enrichment on promoters, resulting in facilitated and reduced levels of HNF4A-AS1 in NB cells, respectively (Additional file 1: Figure S4e-f). Meanwhile, ectopic expression of MYCN did not affect the degradation of HNF4A-AS1 in SH-SY5Y cells treated with actinomycin D (Additional file 1: Figure S4g). Notably, there was a positive correlation between MYCN and HNF4A-AS1 in NB tissues (Additional file 1: Figure S4h). These results indicated that MYCN promoted the expression of HNF4A-AS1 in NB.

Fig. 2.

HNF4A-AS1 promotes aerobic glycolysis and NB progression. a Schematic illustration indicating genomic location of HNF4A-AS1 and HNF4A. Northern blot using a 254-bp specific probe and real-time qRT-PCR (normalized to β-actin, n = 5) showing the endogenous existence of HNF4A-AS1 transcript in normal dorsal root ganglia (DG), NB cell lines, and MCF 10A cells. b RNA-FISH using a 254-bp antisense probe showing localization (arrowheads) of HNF4A-AS1 in the nuclei (DAPI staining) of BE(2)-C cells, with sense probe and RNase A (20 μg) treatment as negative controls. Scale bars, 10 μm. c Real-time qRT-PCR (normalized to β-actin, n = 4) revealing the enrichment of HNF4A-AS1 in the cytoplasm and nuclei of NB cells. d Western blot assay indicating the expression of HNF4A and glycolytic genes in SH-SY5Y, SK-N-AS, and BE(2)-C cells stably transfected with empty vector (mock), HNF4A-AS1, scramble shRNA (sh-Scb), or sh-HNF4A-AS1. e–g ECAR bars (e), soft agar (f), and matrigel invasion (g) assays showing glycolysis, anchor-independent growth, and invasion of NB cells stably transfected with mock, HNF4A-AS1, sh-Scb, or sh-HNF4A-AS1, and those treated with 2-DG (10 mmol·L−1, n = 4). h Representative images, in vivo growth curve, Ki-67 and CD31 immunostaining, and weight at the end points of subcutaneous xenograft tumors formed by SH-SY5Y cells stably transfected with mock or HNF4A-AS1 in nude mice (n = 5 per group). Scale bar, 100 μm. i In vivo imaging, representative images and metastatic counts of lungs, and Kaplan-Meier curves of nude mice (n = 5 per group) treated with tail vein injection of SH-SY5Y cells stably transfected with mock or HNF4A-AS1. Scale bar, 100 μm. ANOVA and Student’s t test compared the difference in a and e–i. Log-rank test for survival comparison in i. *P < 0.05 vs. DG, mock, or sh-Scb. Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m. (error bars) and representative of three independent experiments in a–g

Ectopic expression or knockdown of HNF4A did not alter HNF4A-AS1 levels in NB cells (Additional file 1: Figure S5a). Instead, stable transfection of HNF4A-AS1 or shRNA against HNF4A-AS1 (sh-HNF4A-AS1) increased and decreased the transcript and protein levels of HNF4A and its downstream target genes (HK2 and SLC2A1) in SK-N-AS, SH-SY5Y, and BE(2)-C cells (with low, middle, and high HNF4A-AS1 levels, respectively) (Fig. 2d and Additional file 1: Figure S5b). We further applied dCas9-based clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) [27] to repress expression of HNF4A-AS1, resulting in decreased HK2 and SLC2A1 levels in BE(2)-C and SH-SY5Y cells (Additional file 1: Figure S5c, d). ECAR was increased and decreased in NB cells stably transfected with HNF4A-AS1, sh-HNF4A-AS1, or dCas9i-HNF4A-AS1, along with reduced and enhanced OCR, respectively (Fig. 2e and Additional file 1: Figure S5e). Consistently, stable over-expression or knockdown of HNF4A-AS1 increased and decreased the glucose uptake, lactate production, and ATP levels of NB cells, respectively (Additional file 1: Figure S5f). In addition, treatment with glycolysis inhibitor 2-DG prevented SH-SY5Y and SK-N-AS cells from alteration in these biological features induced by HNF4A-AS1 over-expression (Fig. 2e and Additional file 1: Figure S5e, f). To validate gene-specific alteration, RNAi-resistant HNF4A-AS1 was transfected into BE(2)-C cells, which rescued the downregulation of HK2 and SLC2A1 (Additional file 1: Figure S6a), alteration of ECAR and OCR (Additional file 1: Figure S6b), and decrease of glucose uptake, lactate production, and ATP levels (Additional file 1: Figure S6c) induced by HNF4A-AS1 knockdown. Knockdown or ectopic expression of HNF4A rescued the alteration in glycolytic process in SH-SY5Y and BE(2)-C cells with stable over-expression or silencing of HNF4A-AS1, respectively (Additional file 1: Figure S6d-e). Accordingly, stable over-expression or knockdown of HNF4A-AS1 increased and decreased the anchorage-independent growth and invasion of NB cells, respectively (Fig. 2f, g, and Additional file 1: Figure S7a, b). Meanwhile, 2-DG treatment abolished the increase in growth and invasion of SH-SY5Y cells stably over-expressing HNF4A-AS1 (Fig. 2f, g). In nude mice, the growth, weight, Ki-67 proliferation index, and CD31-positive microvessels of subcutaneous xenograft tumors formed by NB cells were increased and decreased by stable over-expression or knockdown of HNF4A-AS1, respectively (Fig. 2h and Additional file 1: Figure S7c, d). In experimental metastasis assay, athymic nude mice treated with tail vein injection of SH-SY5Y and BE(2)-C cells stably transfected with HNF4A-AS1 or sh-HNF4A-AS1 #1 displayed more or less lung metastatic colonies, with less or greater survival probability, respectively (Fig. 2i and Additional file 1: Figure S7e). These results indicated that HNF4A-AS1 promoted aerobic glycolysis, tumorigenesis, and aggressiveness of NB cells.

HNF4A-AS1 interacts with hnRNPU protein in NB cells

To investigate protein partner of HNF4A-AS1, we performed biotin-labeled RNA pull-down followed by mass spectrometry analysis in BE(2)-C cells, which revealed 218 differential proteins between HNF4A-AS1 and its antisense transcript pull-down groups (Additional file 1: Table S5), and 13 of them were RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) defined by RBPDB (http://rbpdb.ccbr.utoronto.ca, Additional file 1: Figure S8a). In combination with Coomassie blue staining results, hnRNPU was identified as protein with highest spectral counts (with 92 detected peptides) pulled down by biotin-labeled HNF4A-AS1 (Fig. 3a). Further validation indicated that hnRNPU was readily detected in HNF4A-AS1 pull-down complex, but not in control samples pulled down by HNF4A-AS1 antisense transcript or beads only (Fig. 3b). There was an endogenous interaction of HNF4A-AS1 with hnRNPU, but not with hnRNPK, while no interaction between hnRNPU and HOX transcript antisense RNA (HOTAIR) was observed in BE(2)-C cells (Additional file 1: Figure S8b). Co-localization of HNF4A-AS1 and hnRNPU was noted in SH-SY5Y cells, which was increased by transfection of HNF4A-AS1 (Fig. 3c). Deletion-mapping RIP, biotin-labeled RNA pull-down, and RNA EMSA assays indicated that exon 1 of HNF4A-AS1 was required for its interaction with hnRNPU (Fig. 3d–f). Meanwhile, Arg-Gly-Gly [RGG, 714-739 amino acids (aa)], but not scaffold attachment factor-A/B, acinus and PIAS (SAP, 8-42 aa), SPla/RYanodine receptor (SPRY, 267-464 aa), or p300 binding (682-713 aa) domain, of glutathione S-transferase (GST)- or FLAG-tagged hnRNPU protein was required for its interaction with HNF4A-AS1 (Fig. 3g, h). These data demonstrated that HNF4A-AS1 interacted with hnRNPU protein in NB cells.

Fig. 3.

HNF4A-AS1 interacts with hnRNPU protein in NB cells. a Coomassie blue staining (left panel) and mass spectrometry (MS) assay (right panel) of indicated electrophoretic bands revealing the identification of protein pulled down by biotin-labeled HNF4A-AS1 in BE(2)-C cells. b Biotin-labeled RNA pull-down and Western blot assays showing the hnRNPU protein pulled down by sense or antisense (AS) HNF4A-AS1 from lysates of BE(2)-C cells. The HNF4A-AS1 AS- and bead-bound protein served as negative controls. c Dual RNA-FISH and immunofluorescence staining assay indicating the co-localization of hnRNPU and HNF4A-AS1 in the nuclei of SH-SY5Y cells stably transfected with empty vector (mock) or HNF4A-AS1. d RIP (upper right panel) and Western blot (lower right panel) assays using hnRNPU antibody showing the interaction between HNF4A-AS1 and hnRNPU protein in SH-SY5Y cells transfected with a series truncations of HNF4A-AS1 (left panel). The IgG-bound RNA was taken as a negative control. e Biotin-labeled RNA pull-down assay revealing the interaction between HNF4A-AS1 truncations and hnRNPU protein in BE(2)-C cells. Bead-bound protein served as a negative control. f RNA EMSA assay using biotin-labeled probes indicating the interaction of HNF4A-AS1 truncations with recombinant GST-tagged hnRNPU protein, with or without competition using an excess of unlabeled homologous probe. g Biotin-labeled RNA pull-down and Western blot assays showing the recovered hnRNPU truncations (upper panel) after incubation of biotin-labeled HNF4A-AS1 with full-length or truncated forms of GST-tagged recombinant hnRNPU protein (lower panel). h RIP assay using FLAG antibody indicating the interaction between HNF4A-AS1 truncations and FLAG-tagged hnRNPU protein in BE(2)-C cells. The IgG was applied as a negative control. Data are representative of three independent experiments in b–h

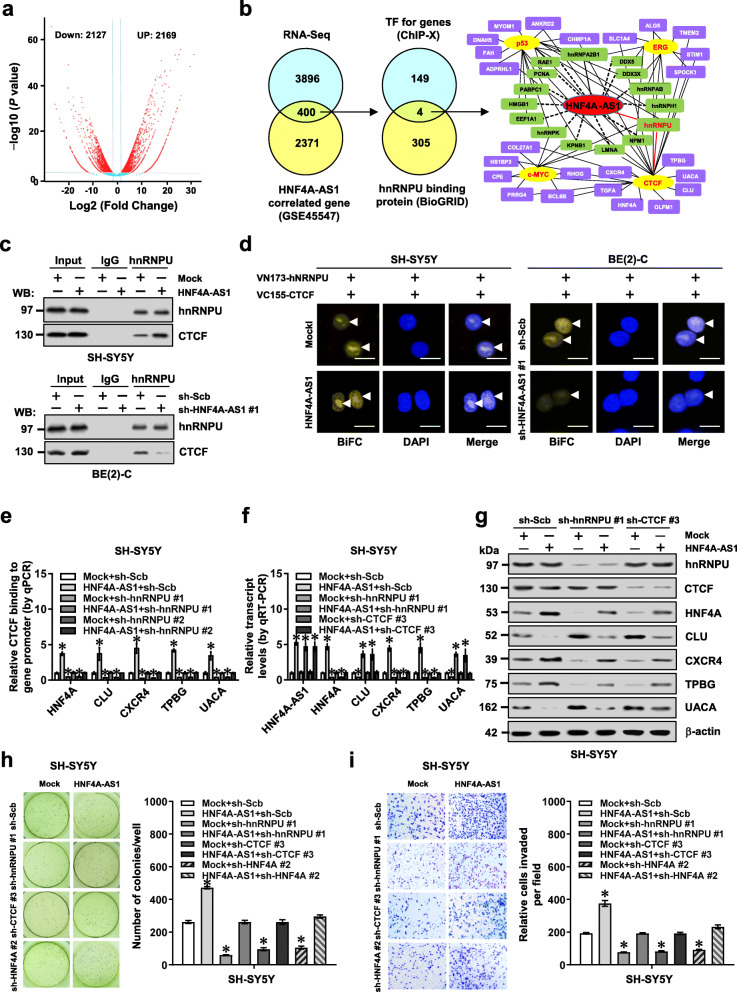

HNF4A-AS1 facilitates aerobic glycolysis and aggressiveness of NB cells via hnRNPU-mediated transactivation of CTCF

To identify putative targets of HNF4A-AS1, we observed HNF4A-AS1-induced differentially expressed genes by RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) in SH-SY5Y cells. There were 2169 upregulated and 2127 downregulated genes (fold change > 2.0, P < 0.05) upon HNF4A-AS1 over-expression (Fig. 4a). Further over-lapping (P < 0.001) with 2771 HNF4A-AS1-correlated genes (P < 0.05) in public NB cases (GSE45547) identified 400 genes consistently associated with HNF4A-AS1 levels (Fig. 4b). Integrative analysis of hnRNPU-interacting transcriptional regulators of these altered genes (Additional file 1: Table S6) by using ChIP-X program and BioGRID database [28] revealed four potential transcription factors, including CTCF, Ets-related gene (ERG), c-Myc, and p53 (Fig. 4b). Of note, stable over-expression or knockdown of HNF4A-AS1 altered the transactivation of CTCF but not of ERG, c-Myc, or p53, in SH-SY5Y, SK-N-AS, and BE(2)-C cells (Additional file 1: Figure S8c). Endogenous physical interaction between hnRNPU and CTCF was observed in BE(2)-C cells (Additional file 1: Figure S8d). The SPRY domain (267-464 aa) of hnRNPU and zinc finger domain (291-499 aa) of CTCF were crucial for their interaction (Additional file 1: Figure S9a). Co-IP, Western blot, and BiFC [29] assays indicated that ectopic expression of HNF4A-AS1 facilitated the binding of hnRNPU to CTCF in NB cells, while HNF4A-AS1 knockdown attenuated their interaction (Fig. 4c, d).

Fig. 4.

HNF4A-AS1 facilitates growth and invasion of NB cells via hnRNPU-mediated transactivation of CTCF. a Volcano plots of RNA-seq revealing alteration of gene expression (fold change > 2.0, P < 0.05) in SH-SY5Y cells stably transfected with empty vector (mock) or HNF4A-AS1. b By analyzing with ChIP-X program and BioGRID database, venn diagram (left panel) showing identification of hnRNPU-interacting transcription factors (TFs) regulating genes altered in RNA-seq and correlated with HNF4A-AS1 in a public dataset (GSE45547). Gene network (right panel) revealing identified TFs and target genes. c Co-IP and Western blot assays indicating the interaction between hnRNPU and CTCF in SH-SY5Y and BE(2)-C cells stably transfected with mock, HNF4A-AS1, scramble shRNA (sh-Scb), or sh-HNF4A-AS1 #1. d Confocal images of BiFC assay showing direct interaction between hnRNPU and CTCF (arrowheads) within SH-SY5Y and BE(2)-C cells co-transfected with pBiFC-VN173-hnRNPU and pBiFC-VC155-CTCF, and those stably transfected with mock, HNF4A-AS1, sh-Scb, or sh-HNF4A-AS1 #1. Scale bars, 10 μm. e ChIP and real-time qPCR (normalized to input) assays indicating the CTCF enrichment on target gene promoters in SH-SY5Y cells stably transfected with mock or HNF4A-AS1, and those co-transfected with sh-hnRNPU (n = 5). f and g Real-time qRT-PCR (f, normalized to β-actin, n = 4) and Western blot (g) assays showing the levels of HNF4A-AS1, hnRNPU, CTCF, and target genes in SH-SY5Y cells stably transfected with mock or HNF4A-AS1, and those co-transfected with sh-Scb, sh-hnRNPU #1, or sh-CTCF #3. h and i Representative images (left panel) and quantification (right panel) of soft agar (h) and matrigel invasion (i) assays indicating anchorage-independent growth and invasion of SH-SY5Y cells stably transfected with mock or HNF4A-AS1, and those co-transfected with sh-hnRNPU #1, sh-CTCF #3, or sh-HNF4A #2 (n = 5). ANOVA compared the difference in e, f, h, and i. *P < 0.05 vs. mock+sh-Scb. Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m. (error bars) and representative of three independent experiments in c–i

In SH-SY5Y and BE(2)-C cells, stable over-expression or silencing of HNF4A-AS1 increased and decreased the CTCF enrichment on target gene promoters, respectively, while knockdown or ectopic expression of hnRNPU prevented these effects (Fig. 4e and Additional file 1: Figure S9b-d). In addition, ectopic expression or silencing of HNF4A-AS1 prevented the altered binding of RNA Pol II, H3K4me3, and H3K27me3 to target gene promoters induced by knockdown or over-expression of CTCF (Additional file 1: Figure S9e, f and Figure S10). Dual-luciferase assay indicated the decreased HNF4A promoter activity in NB cells transfected with sh-CTCF, which was abolished by mutation of CTCF-binding site (Additional file 1: Figure S11a). Moreover, silencing of HNF4A-AS1 neutralized the increase of HNF4A promoter activity induced by over-expression of hnRNPU or CTCF, respectively (Additional file 1: Figure S11a). Consistently, knockdown or ectopic expression of hnRNPU or CTCF rescued the alteration in expression of CTCF target genes (HNF4A, CLU, CXCR4, TPBG, and UACA), glucose uptake, lactate production, ATP levels, anchorage-independent growth, and invasion of SH-SY5Y or BE(2)-C cells induced by stable over-expression or silencing of HNF4A-AS1, respectively (Fig. 4f–i and Additional file 1: Figure S11b-f). Meanwhile, silencing or ectopic expression of HNF4A partially restored the changes in anchorage-independent growth and invasion of SH-SY5Y or BE(2)-C cells with stable over-expression or silencing of HNF4A-AS1, respectively (Fig. 4h–i and Additional file 1: Figure S11e-f). These results indicated that HNF4A-AS1 facilitated aerobic glycolysis and aggressiveness of NB cells via hnRNPU-mediated transactivation of CTCF.

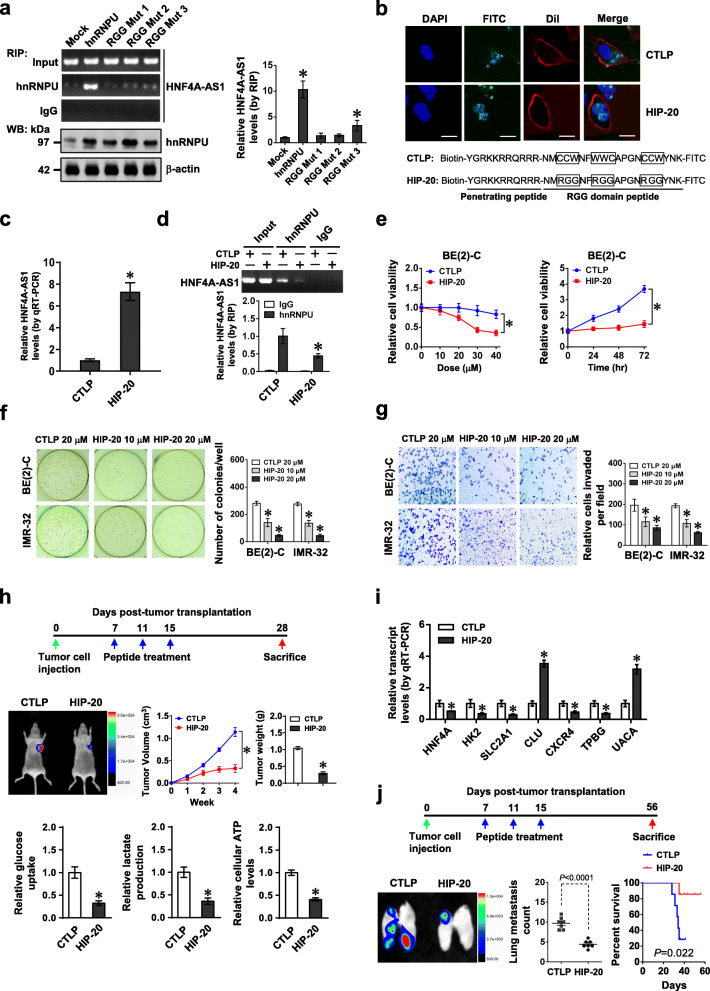

Therapeutic blocking HNF4A-AS1-hnRNPU interaction inhibits aerobic glycolysis and NB progression

Based on above findings that RGG domain (714-739 aa) of hnRNPU was necessary for its binding to HNF4A-AS1, RNABindRPlus analysis [30] further implicated the necessity of three RGG residues for this process. Mutation of these residues abolished the binding of hnRNPU to HNF4A-AS1 in BE(2)-C cells (Fig. 5a). Administration of a cell-penetrating hnRNPU inhibitory peptide of 20 amino acids (HIP-20), but not of RGG mutant control peptide (CTLP), resulted in obvious nuclear aggregation in BE(2)-C cells (Fig. 5b). The binding of HIP-20 to HNF4A-AS1 was validated by biotin-labeled peptide pull-down assay (Fig. 5c). In addition, HIP-20 treatment attenuated endogenous interaction of hnRNPU with HNF4A-AS1 (Fig. 5d), prevented the alteration in downstream gene expression induced by stable over-expression of HNF4A-AS1 (Additional file 1: Figure S12a), and inhibited the viability of BE(2)-C cells [with half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 26.5 μmol·L−1, Fig. 5e], but not of non-transformed MCF 10A cells (Additional file 1: Figure S12b). Administration of HIP-20 suppressed the anchorage-independent growth and invasion of viable BE(2)-C and IMR-32 cells in vitro (Fig. 5f, g). Intravenous administration of HIP-20 decreased the growth, weight, glucose uptake, lactate production, ATP levels, Ki-67 proliferation index, and CD31-positive microvessels, and altered HNF4A-AS1 target gene expression of subcutaneous xenograft tumors formed by BE(2)-C cells in nude mice (Fig. 5h, i, Additional file 1: Figure S12c, d). Moreover, HIP-20 treatment resulted in less lung metastatic counts and longer survival time of nude mice treated with tail vein injection of BE(2)-C cells (Fig. 5j and Additional file 1: Figure S12e). These results demonstrated that blocking HNF4A-AS1-hnRNPU interaction suppressed aerobic glycolysis and NB progression.

Fig. 5.

Therapeutic blocking HNF4A-AS1-hnRNPU interaction inhibits aerobic glycolysis and NB progression. a RIP and real-time qRT-PCR assays showing the binding of hnRNPU to HNF4A-AS1 in BE(2)-C cells stably transfected with wild-type or RGG mutant form of hnRNPU. b Representative images indicating the distribution of FITC-labeled RGG mutant control (CTLP) or hnRNPU inhibitory peptide (HIP-20, 20 μmol·L−1) in BE(2)-C cells, with nuclei and cellular membranes staining with DAPI or Dil. Scale bar, 10 μm. c and d Real-time qRT-PCR (c, normalized to β-actin, n = 4) and RIP (d) assays revealing HNF4A-AS1 pulled down by biotin-labeled CTLP or HIP-20 (20 μmol·L−1), and interaction of HNF4A-AS1 with hnRNPU in BE(2)-C cells treated with CTLP or HIP-20 (20 μmol·L−1). e–g MTT colorimetric (e), soft agar (f), and matrigel invasion (g) assays indicating the viability, anchorage-independent growth, and invasion of NB cells treated with different doses of CTLP or HIP-20 for 24 h, or 20 μmol·L−1 peptides for time points as indicated (n = 5). h and i Representative images (h, left middle panel), in vivo growth curve (h, left middle panel), tumor weight (h, right middle panel), glucose uptake, lactate production, and ATP levels (h, lower panel), and HNF4A-AS1 downstream gene expression (i, normalized to β-actin) of BE(2)-C-formed subcutaneous xenograft tumors (n = 5 per group) that were treated with intravenous injection of CTLP or HIP-20 (5 mg·kg−1) as indicated (h, upper panel). j Representative images and metastatic counts of lungs and Kaplan-Meier curves (lower panel) of nude mice (n = 5 per group) treated with tail vein injection of BE(2)-C cells and CTLP or HIP-20 (5 mg·kg−1) as indicated (upper panel). ANOVA and Student’s t test compared the difference in a and c–j. Log-rank test for survival comparison in j. *P < 0.01 vs. mock or CTLP. Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m. (error bars) and representative of three independent experiments in a–g

Lentiviral knockdown of HNF4A-AS1 inhibits aerobic glycolysis and NB progression

To further assess the therapeutic efficacy of HNF4A-AS1 knockdown, nude mice were treated with subcutaneous or tail vein injection of IMR-32 cells. Intravenous administration of lentivirus-mediated sh-HNF4A-AS1 #1 dramatically reduced the growth, weight, glucose uptake, lactate production, ATP levels, Ki-67 proliferation index, and CD31-positive microvessels of subcutaneous xenograft tumors (Additional file 1: Figure S13a-c), accompanied by significant alteration in expression of HNF4A-AS1 and its target genes (Additional file 1: Figure S13d, e). Nude mice treated with tail vein administration of lentivirus-mediated sh-HNF4A-AS1 #1 presented fewer metastatic lung counts and longer survival time (Additional file 1: Figure S13f). These data indicated that lentivirus-mediated HNF4A-AS1 knockdown suppressed aerobic glycolysis and NB progression.

HNF4A-AS1, hnRNPU, CTCF, or target gene expression is associated with tumor outcome

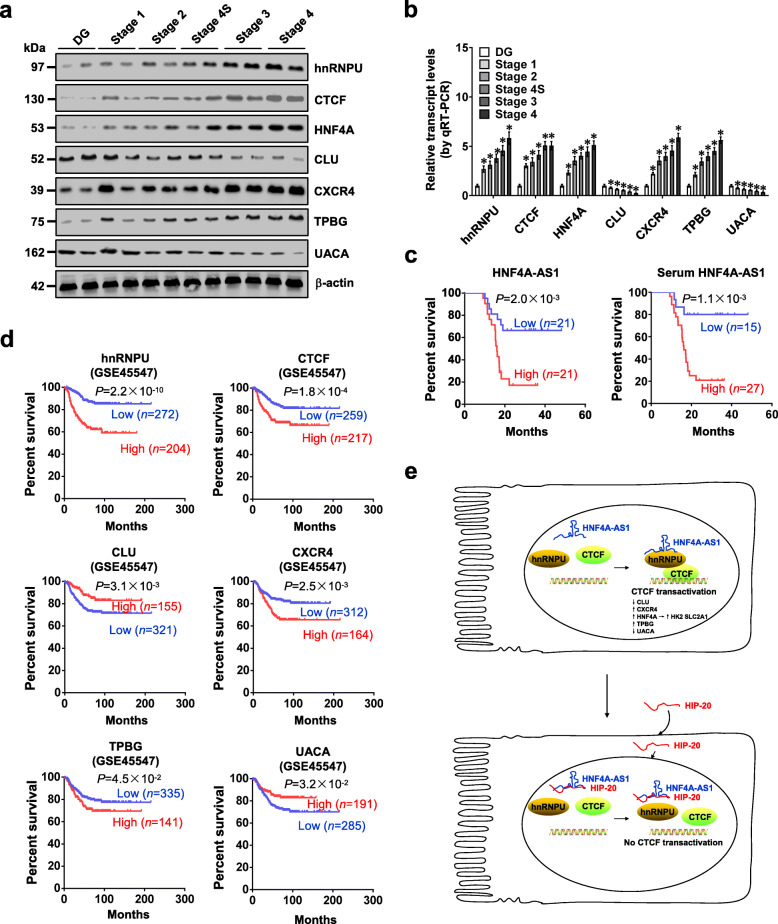

In 42 primary NB tissues, higher expression of hnRNPU, CTCF, HNF4A, CXCR4, or TPBG, and lower levels of CLU or UACA were observed, than those in normal dorsal root ganglia (Fig. 6a, b). Patients with high HNF4A-AS1 levels in tumor tissues or serum had lower survival probability (Fig. 6c). The levels of HNF4A-AS1, hnRNPU, and CTCF were positively or negatively correlated with those of target genes (Additional file 1: Figure S14a), and their expression was significantly associated with survival of 42 NB patients (Additional file 1: Figure S14b). Moreover, mining of a public NB dataset (GSE45547) revealed that high expression of hnRNPU (P = 2.2 × 10−10), CTCF (P = 1.8 × 10−4), CXCR4 (P = 2.5 × 10−3), or TPBG (P = 4.5 × 10−2) and low expression of CLU (P = 3.1 × 10−3) or UACA (P = 3.2 × 10−2) was associated with poor outcome of patients (Fig. 6d). High expression of hnRNPU or CTCF was also associated with poor survival of patients with breast cancer, colon cancer, glioblastoma, lung cancer, ovarian cancer, or prostate cancer (Additional file 1: Figure S15). These results indicated that expression of HNF4A-AS1, hnRNPU, CTCF, or target genes was associated with outcome of tumors.

Fig. 6.

Expression of HNF4A-AS1, hnRNPU, CTCF, or target gene is associated with outcome of NB. a and b Western blot (a) and real-time qRT-PCR (b, normalized to β-actin) assays revealing the levels of hnRNPU, CTCF, and their downstream target genes in normal dorsal root ganglia (DG) and NB tissues (n = 42) of different clinical stages. c Kaplan-Meier curves indicating overall survival in 42 NB patients with low or high expression of HNF4A-AS1 in tumor tissues or serum (cutoff values = 4.29 and 2.71). d Kaplan-Meier curves showing overall survival of NB cases (GSE45547) with low or high expression levels of hnRNPU (cutoff value = 16058.0), CTCF (cutoff value = 2462.2), CLU (cutoff value = 18617.9), CXCR4 (cutoff value = 23442.9), TPBG (cutoff value = 623.7), or UACA (cutoff value = 437.3). e The mechanisms underlying HNF4A-AS1-promoted tumor progression: as a MYCN-facilitated lncRNA, HNF4A-AS1 directly binds to hnRNPU to promote its interaction with CTCF, resulting in transactivation of CTCF, altered transcription of downstream target genes, and promotion of aerobic glycolysis and tumor progression. ANOVA analyzed the differences in b. Log-rank test for survival comparison in c and d. *P < 0.05 vs. DG. Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m. (error bars) in b

Discussion

Integrative screening of transcriptional regulators of aerobic glycolysis in NB remains largely unknown. In this study, we identify HNF4A as a transcription factor facilitating expression of glycolytic genes HK2 and SLC2A1 in NB. Recent studies indicate that as an oncogene associated with poor survival, MYCN is essential for aerobic glycolysis in NB [31], while the underlying mechanisms remain elusive. We demonstrate that as a MYCN-facilitated lncRNA, HNF4A-AS1 interacts with hnRNPU protein to facilitate transactivation of CTCF, which epigenetically regulates transcription of HNF4A and other genes associated with tumor progression in cis and in trans (Fig. 6e), such as CLU [32], CXCR4 [33], TPBG [34], and UACA [35]. Our evidence indicates that HNF4A-AS1 possesses oncogenic properties to promote aerobic glycolysis and NB progression, suggesting its potential as a therapeutic target against tumors.

As a member of nuclear receptor superfamily, HNF4A regulates gene expression through binding to target promoters [36]. Since its first discovery from the liver [37], a total of 12 HNF4A isoforms derived from P1 (α1-α6) or P2 (α7-α12) promoters have been documented, while α4 and α6 isoforms remain to be validated by endogenous expression in tissues [38, 39]. Due to lack of activation function 1 domain, the transactivation activity of P2-HNF4A is weaker than that of P1-HNF4A [40]. In hepatocellular carcinoma, P1-HNF4A expression is diminished, and deletion of HNF4A facilitates diethylnitrosamine-induced hepatic tumors [41]. Ectopic expression of P1-HNF4A inhibits the growth, migration, and invasion of colon cancer cells [42]. Meanwhile, high P1-HNF4A expression is observed in ovarian mucinous adenocarcinoma [43]. In gastric cancer, P1- or P2-HNF4A expression is associated with poor prognosis of patients [44]. These results indicate the tumor suppressive or oncogenic functions of HNF4A in a context-dependent manner. Recent studies show that HNF4A isoforms are functionally distinct in activating or repressing a subset of target gene expression [38]. Among the P1-HNF4A isoforms, α1 and α2 are the most potent regulators of gene expression, while α3 isoform exhibits significantly reduced activity of transcription factor [39]. In this study, we found that P1-HNF4A (especially α1 isoform), but not P2-HNF4A, was elevated in NB tissues and associated with poor outcome of patients. In addition, HNF4A promoted the expression of glycolytic genes HK2 and SLC2A1 in NB cells. As an enzyme mediating generation of glucose-6-phosphate, HK2 is essential for tumor initiation and maintenance [45]. SLC2A1 controls the transport of glucose across plasma membrane and is associated with poor survival of colorectal cancer patients [46]. Our gain- and loss-of-function studies indicated that HNF4A promoted aerobic glycolysis, tumorigenesis, and aggressiveness, suggesting its oncogenic roles in NB progression. Since tumor promoting or suppressive roles of transcription factors are affected by specific interacting partners [47], we believe that P1-HNF4A isoforms play different roles in tumors due to their nature of interactome, including their partners involved in gene transcription, which warrants further investigation.

Recent studies show emerging roles of lncRNAs in tumor metabolism. LincRNA-p21 and long intergenic noncoding RNA for kinase activation (LINK-A) facilitate glycolysis reprogramming and tumor growth by regulating hypoxia inducible factor 1 alpha signaling pathway [48, 49]. In contrast, lncRNA c-Myc inhibitory factor (MIF) decreases glucose uptake and lactate production via mediating c-Myc degradation [50]. In this study, HNF4A-AS1 was identified as a lncRNA upregulated in NB tissues and cell lines. Previous studies indicate that HNF4A-AS1 participates in mucosal injury in Crohn’s disease [51], and serves as a HNF4A target gene in hepatocellular carcinoma cells [52]. Our evidence indicated that HNF4A-AS1 facilitated the expression of HNF4A at transcriptional level, and tumor promoting functions of HNF4A-AS1 were mediated, at least in part, through interacting with hnRNPU protein. Previous studies have shown that lncRNAs are stable in serum or plasma, and may serve as promising biomarkers for diagnosis of tumors [53–55]. For instance, serum or plasma HOTAIR is a biomarker for glioblastoma multiforme [53], esophageal squamous cell carcinoma [54], and gastric cancer [55]. Plasma H19 serves as a diagnostic biomarker for gastric cancer [56], while serum LINC00161 or taurine up-regulated 1 (TUG1) levels contribute to assessing the tumor stage and progression of hepatocellular carcinoma [57] and multiple myeloma [58], respectively. Our results revealed that HNF4A-AS1 levels were elevated in serum of NB cases, and associated with clinicopathological features of tumors, indicating its potential value as a biomarker for diagnosis of NB.

As a member of hnRNP subfamily, hnRNPU participates in chromatin remodeling, transcriptional regulation, and mRNA stability [59]. Through physical interaction, hnRNPU regulates the functions of various factors [60, 61]. For example, hnRNPU interacts with p300 to promote local acetylation of nucleosomes and transcription of target genes [60]. Meanwhile, hnRNPU binds to Yes-associated protein to attenuate gene transcription [61]. In mouse hepatocytes, hnRNPU is involved in maintaining 3D chromatin architecture via cooperating with CTCF [62], while their specific cooperation in human tumors remain unclear. In this study, we found that hnRNPU was highly expressed in NB tissues, and was essential for transactivation of CTCF and subsequent epigenetic regulation of target genes. Recent studies indicate that H19 interacts with hnRNPU to regulate gene transcription [63], while lncRNA Xist localizes to inactive chromosome X through binding to hnRNPU [64]. Our results indicated that HNF4A-AS1 bound to RGG domain of hnRNPU, resulting in hnRNPU-mediated transactivation of CTCF in NB cells. In non-small cell lung cancer cells, CTCF increases the promoter activity of solute carrier family 2 member 4 (SLC2A4), implicating its potential roles in glycolysis [65]. As a transcription factor, CTCF utilizes different sets of zinc fingers to bind target sequences [66], and exerts oncogenic roles in NB progression through activating oncogene (MYCN) or repressing tumor suppressors such as forkhead box D3 (FOXD3) [11, 13]. In this study, our evidence indicated the essential functions of CTCF in regulating glycolysis of NB cells, without impact on HNF4A-AS1 expression. We believe that CTCF downstream factors might counteract the roles of MYCN in regulating HNF4A-AS1 levels, which warrants further investigation. Importantly, blocking HNF4A-AS1-hnRNPU interaction or lentivirus-mediated HNF4A-AS1 knockdown was able to suppress aerobic glycolysis, tumorigenesis, and aggressiveness of NB cells, suggesting the oncogenic roles of HNF4A-AS1/hnRNPU/CTCF axis in aerobic glycolysis and tumor progression.

Conclusions

In summary, we demonstrate that HNF4A and its derived lncRNA HNF4A-AS1 exert oncogenic roles in aerobic glycolysis and NB progression. Mechanistically, HNF4A promotes the expression of glycolytic genes HK2 and SLC2A1, while HNF4A-AS1 binds to hnRNPU protein to facilitate its interaction with CTCF, resulting in transactivation of CTCF and transcriptional alteration of HNF4A and other genes associated with tumor progression. An inhibitory peptide blocking HNF4A-AS1-hnRNPU interaction or lentivirus-mediated HNF4A-AS1 knockdown suppresses aerobic glycolysis, tumorigenesis, and aggressiveness of NB cells. We believe that this study extends our knowledge about the regulation of aerobic glycolysis by transcription factor and its derived lncRNA, and suggests that HNF4A-AS1/hnRNPU/CTCF axis may be a potential therapeutic target for tumors.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1 : Figure S1. Expression of HNF4A and its target glycolytic genes in NB tissues and cell lines. Figure S2. HNF4A facilitates the growth and invasion of NB cells via its target glycolytic genes. Figure S3. Kaplan–Meier survival plots of HNF4A, HK2, and SLC2A1 in public tumor datasets. Figure S4. MYCN facilitates the expression of HNF4A-AS1 in NB. Figure S5. HNF4A-AS1 facilitates glycolytic gene expression and glycolysis. Figure S6. Rescue studies reveal the roles of HNF4A-AS1 in regulating glycolytic gene expression and glycolysis. Figure S7. Knockdown of HNF4A-AS1 inhibits the growth and aggressiveness of NB cells. Figure S8. HNF4A-AS1 binds to hnRNPU and facilitates transactivation of CTCF. Figure S9. Interaction between hnRNPU and CTCF in NB cells. Figure S10. HNF4A-AS1 regulates target gene expression through CTCF. Figure S11. HNF4A-AS1 regulates gene expression, growth, and invasion of NB cells through hnRNPU and CTCF. Figure S12. Effects of therapeutic peptide on tumorigenesis and aggressiveness. Figure S13. Lentivirus-mediated HNF4A-AS1 knockdown inhibits NB progression. Figure S14. Expression profiles of HNF4A-AS1, hnRNPU, CTCF and target genes in NB tissues. Figure S15. Kaplan–Meier survival plots of hnRNPU and CTCF in public tumor datasets. Table S1. Primer sets used for qRT-PCR, RT-PCR, RIP, probe, and ChIP. Table S2. Oligonucleotide sets used for constructs. Table S3. Oligonucleotides encoding short hairpin RNAs. Table S4. Demographic and clinicopathological features and HNF4A-AS1 levels of 42 NB patients. Table S5. Mass spectrometry analysis of proteins pulled down by HNF4A-AS1. Table S6. ChIP-X analysis of transcription factors regulating HNF4A-AS1 target genes.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for Drs. David Martinez Selva and Arturo Sala in providing vectors.

Abbreviations

- ALDOB

Fructose-bisphosphate B

- BiFC

Bimolecular fluorescence complementation

- ChIP

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

- CLU

Clusterin

- Co-IP

Co-immunoprecipitation

- CTCF

CCCTC-binding factor

- CXCR4

C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 4

- ECAR

Extracellular acidification rate

- EMSA

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

- ERG

Ets-related gene

- GST

Glutathione S-transferase

- H3K27me3

Histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation

- H3K4me3

Histone H3 lysine 4 trimethylation

- HNF4A

Hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 alpha

- HNF4A-AS1

HNF4A antisense RNA 1

- hnRNPK

Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K

- hnRNPU

Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein U

- HOTAIR

HOX transcript antisense RNA

- LDHA

Lactate dehydrogenase A

- LDHD

Lactate dehydrogenase D

- lncRNA

Long noncoding RNA

- MYCN

V-myc avian myelocytomatosis viral oncogene neuroblastoma-derived homolog

- NB

Neuroblastoma

- OCR

Oxygen consumption rate

- PGK1

Phosphoglycerate kinase 1

- PKM2

Pyruvate kinase M2

- qPCR

Quantitative PCR

- qRT-PCR

Quantitative RT-PCR

- RACE

Rapid amplification of cDNA ends

- RBP

RNA binding protein

- RIP

RNA immunoprecipitation

- RNA Pol II

RNA polymerase II

- RNA-seq

RNA sequencing

- shRNA

Short hairpin RNA

- SLC2A3

Solute carrier family 2 member 3

- TPBG

Trophoblast glycoprotein

- TUG1

Taurine up-regulated 1

- UACA

Uveal autoantigen with coiled-coil domains and ankyrin repeats

Authors’ contributions

HS and DL conceived and performed most of the experiments; XW, EF, FY, AH, and JW accomplished some of the in vitro experiments; YG, YL, HL, and YC accomplished the in vivo studies; HS and EF undertook the mining of publicly available datasets; KH critically reviewed the manuscript; QT and LZ wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was granted by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81272779, 81372667, 81472363, 81402301, 81402408, 81572423, 81672500, 81773094, 81772967, 81874085, 81874066, 81802925, 81903011, 81903008), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2019kfyRCPY032, 2012QN224, 2013ZHYX003, 01-18-530112, 01-18-530115), and Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province (2014CFA012).

Availability of data and materials

RNA-seq data supporting the results of this study have been deposited in GEO database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/), under accession number GSE143896. Public datasets are available from GEO database (GSE45547, GSE4922, GSE24550, GSE13041, GSE8894, GSE17260, GSE21032). All remaining data are presented within the article and Supplementary Information Files, and available from the corresponding author upon request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Care Committee of Tongji Medical College. The Institutional Review Board of Tongji Medical College approved the human tissue study. All procedures were carried out in accordance with guidelines set forth by Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from all legal guardians of patients.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

This article has been retracted. Please see the retraction notice for more detail: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-023-01493-7

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Huajie Song, Dan Li and Xiaojing Wang contributed equally to this work.

Change history

8/15/2023

This article has been retracted. Please see the Retraction Notice for more detail: 10.1186/s13045-023-01493-7

Contributor Information

Huajie Song, Email: huajiesong89@126.com.

Dan Li, Email: d.li26@hotmail.com.

Xiaojing Wang, Email: xiaojingwangunion@163.com.

Erhu Fang, Email: erhufang@163.com.

Feng Yang, Email: fengyangunion@163.com.

Anpei Hu, Email: anpei_hu@163.com.

Jianqun Wang, Email: jianqun_wang@126.com.

Yanhua Guo, Email: yanhuaguo99@hotmail.com.

Yang Liu, Email: yang_liu2000@126.com.

Hongjun Li, Email: hongjun_liwh@163.com.

Yajun Chen, Email: yajun_chentj@126.com.

Kai Huang, Email: kaihuangunion@gmail.com.

Liduan Zheng, Email: ld_zheng@hotmail.com.

Qiangsong Tong, Email: qs_tong@hotmail.com.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s13045-020-00857-7.

References

- 1.Pinto NR, Applebaum MA, Volchenboum SL, Matthay KK, London WB, Ambros PF, et al. Advances in risk classification and treatment strategies for neuroblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3008–3017. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.4648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ganapathy-Kanniappan S, Geschwind JF. Tumor glycolysis as a target for cancer therapy: progress and prospects. Mol Cancer. 2013;12:152. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-12-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lu J, Tan M, Cai Q. The Warburg effect in tumor progression: mitochondrial oxidative metabolism as an anti-metastasis mechanism. Cancer Lett. 2015;356:156–164. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.David CJ, Chen M, Assanah M, Canoll P, Manley JL. HnRNP proteins controlled by c-Myc deregulate pyruvate kinase mRNA splicing in cancer. Nature. 2010;463:364–368. doi: 10.1038/nature08697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kawauchi K, Araki K, Tobiume K, Tanaka N. p53 regulates glucose metabolism through an IKK-NF-κB pathway and inhibits cell transformation. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:611–618. doi: 10.1038/ncb1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nilsson H, Lindgren D, Mandahl Forsberg A, Mulder H, Axelson H, Johansson ME. Primary clear cell renal carcinoma cells display minimal mitochondrial respiratory capacity resulting in pronounced sensitivity to glycolytic inhibition by 3-Bromopyruvate. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6:e1585. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ciavardelli D, Rossi C, Barcaroli D, Volpe S, Consalvo A, Zucchelli M, et al. Breast cancer stem cells rely on fermentative glycolysis and are sensitive to 2-deoxyglucose treatment. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1336. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barnhill LM, Williams RT, Cohen O, Kim Y, Batova A, Mielke JA, et al. High expression of CAI2, a 9p21-embedded long noncoding RNA, contributes to advanced-stage neuroblastoma. Cancer Res. 2014;74:3753–3763. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-3447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li D, Wang X, Mei H, Fang E, Ye L, Song H, et al. Long noncoding RNA pancEts-1 promotes neuroblastoma progression through hnRNPK-mediated beta-catenin stabilization. Cancer Res. 2018;78:1169–1183. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pandey GK, Mitra S, Subhash S, Hertwig F, Kanduri M, Mishra K, et al. The risk-associated long noncoding RNA NBAT-1 controls neuroblastoma progression by regulating cell proliferation and neuronal differentiation. Cancer Cell. 2014;26:722–737. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2014.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao X, Li D, Pu J, Mei H, Yang D, Xiang X, et al. CTCF cooperates with noncoding RNA MYCNOS to promote neuroblastoma progression through facilitating MYCN expression. Oncogene. 2016;35:3565–3576. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiao W, Chen Y, Song H, Li D, Mei H, Yang F, et al. HPSE enhancer RNA promotes cancer progression through driving chromatin looping and regulating hnRNPU/p300/EGR1/HPSE axis. Oncogene. 2018;37:2728–2745. doi: 10.1038/s41388-018-0128-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao X, Li D, Huang D, Song H, Mei H, Fang E, et al. Risk-associated long noncoding RNA FOXD3-AS1 inhibits neuroblastoma progression by repressing PARP1-mediated activation of CTCF. Mol Ther. 2018;26:755–773. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 14.Li D, Song H, Mei H, Fang E, Wang X, Yang F, et al. Armadillo repeat containing 12 promotes neuroblastoma progression through interaction with retinoblastoma binding protein 4. Nat Commun. 2018;9:2829. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05286-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang F, Fang E, Mei H, Chen Y, Li H, Li D, et al. Cis-acting circ-CTNNB1 promotes β-Catenin signaling and cancer progression via DDX3-mediated transactivation of YY1. Cancer Res. 2019;79:557–571. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simó R, Barbosa-Desongles A, Lecube A, Hernandez C, Selva DM. Potential role of tumor necrosis factor-α in downregulating sex hormone-binding globulin. Diabetes. 2012;61:372–382. doi: 10.2337/db11-0727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chayka O, Corvetta D, Dews M, Caccamo AE, Piotrowska I, Santilli G, et al. Clusterin, a haploinsufficient tumor suppressor gene in neuroblastomas. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:663–677. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma X, Li C, Sun L, Huang D, Li T, He X, et al. Lin28/let-7 axis regulates aerobic glycolysis and cancer progression via PDK1. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5212. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li D, Mei H, Pu J, Xiang X, Zhao X, Qu H, et al. Intelectin 1 suppresses the growth, invasion and metastasis of neuroblastoma cells through up-regulation of N-myc downstream regulated gene 2. Mol Cancer. 2015;14:47. doi: 10.1186/s12943-015-0320-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang H, Pu J, Qi T, Qi M, Yang C, Li S, et al. MicroRNA-145 inhibits the growth, invasion, metastasis and angiogenesis of neuroblastoma cells through targeting hypoxia-inducible factor 2 alpha. Oncogene. 2012;33:387–397. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marshall J. Transwell® Invasion Assays. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;769:97–110. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-207-6_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang R, Liu P, Pan D, Zhang P, Bai Z, Xu Y, et al. An investigation on a novel anti-tumor fusion peptide of FSH33-53-IIKK. J Cancer. 2016;7:1010–1019. doi: 10.7150/jca.14425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kocak H, Ackermann S, Hero B, Kahlert Y, Oberthuer A, Juraeva D, et al. Hox-C9 activates the intrinsic pathway of apoptosis and is associated with spontaneous regression in neuroblastoma. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4:e586. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lachmann A, Xu H, Krishnan J, Berger SI, Mazloom AR, Ma’ayan A. ChEA: transcription factor regulation inferred from integrating genome-wide ChIP-X experiments. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2438–2444. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iqbal MA, Siddiqui FA, Gupta V, Chattopadhyay S, Gopinath P, Kumar B, et al. Insulin enhances metabolic capacities of cancer cells by dual regulation of glycolytic enzyme pyruvate kinase M2. Mol Cancer. 2013;12:72. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-12-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang L, Park HJ, Dasari S, Wang S, Kocher JP, Li W. CPAT: Coding-Potential Assessment Tool using an alignment-free logistic regression model. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:e74. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gilbert LA, Horlbeck MA, Adamson B, Villalta JE, Chen Y, Whitehead EH, et al. Genome-scale CRISPR-mediated control of gene repression and activation. Cell. 2014;159:647–661. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stark C, Breitkreutz BJ, Reguly T, Boucher L, Breitkreutz A, Tyers M. BioGRID: a general repository for interaction datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D535–D539. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller KE, Kim Y, Huh WK, Park HO. Bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) analysis: advances and recent applications for genome-wide interaction studies. J Mol Biol. 2015;427:2039–2055. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walia RR, Xue LC, Wilkins K, El-Manzalawy Y, Dobbs D, Honavar V. RNABindRPlus: a predictor that combines machine learning and sequence homology-based methods to improve the reliability of predicted RNA-binding residues in proteins. PLoS One. 2014;9:e97725. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oliynyk G, Ruiz-Pérez MV, Sainero-Alcolado L, Dzieran J, Zirath H, Gallart-Ayala H, et al. MYCN-enhanced oxidative and glycolytic metabolism reveals vulnerabilities for targeting neuroblastoma. iScience. 2019;21:188–204. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2019.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shiota M, Zardan A, Takeuchi A, Kumano M, Beraldi E, Naito S, et al. Clusterin mediates TGF-β–induced epithelial–mesenchymal transition and metastasis via Twist1 in prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2012;72:5261–5272. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-0254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xiang Z, Zhou ZJ, Xia GK, Zhang XH, Wei ZW, Zhu JT, et al. A positive crosstalk between CXCR4 and CXCR2 promotes gastric cancer metastasis. Oncogene. 2017;36:5122–5133. doi: 10.1038/onc.2017.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kerk SA, Finkel KA, Pearson AT, Warner KA, Zhang Z, Nör F, et al. 5 T4-targeted therapy ablates cancer stem cells and prevents recurrence of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:2516–2527. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burikhanov R, Shrestha-Bhattarai T, Qiu S, Shukla N, Hebbar N, Lele SM, et al. Novel mechanism of apoptosis resistance in cancer mediated by extracellular PAR-4. Cancer Res. 2013;73:1011–1019. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sladek F, Zhong W, Lai E, Darnell J. Liver-enriched transcription factor HNF-4 is a novel member of the steroid hormone receptor superfamily. Genes Dev. 1990;4:2353–2365. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.12b.2353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Costa RH, Grayson DR, Darnell JE. Multiple hepatocyte-enriched nuclear factors function in the regulation of transthyretin and alpha 1-antitrypsin genes. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:1415–1425. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.4.1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ko HL, Zhuo Z, Ren EC. HNF4α combinatorial isoform heterodimers activate distinct gene targets that differ from their corresponding homodimers. Cell Rep. 2019;26:2549–2557. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lambert É, Babeu JP, Simoneau J, Raisch J, Lavergne L, Lévesque D, et al. Human hepatocyte nuclear factor 4-α encodes isoforms with distinct transcriptional functions. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2020; 10.1074/mcp.RA119.001909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Briançon N, Weiss MC. In vivo role of the HNF4alpha AF-1 activation domain revealed by exon swapping. EMBO J. 2006;25:1253–1262. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walesky C, Edwards G, Borude P, Gunewardena S, O’Neil M, Yoo B, et al. Hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 alpha deletion promotes diethylnitrosamine-induced hepatocellular carcinoma in rodents. Hepatology. 2013;57:2480–2490. doi: 10.1002/hep.26251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vuong LM, Chellappa K, Dhahbi JM, Deans JR, Fang B, Bolotin E, et al. Differential effects of hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α isoforms on tumor growth and T-cell factor 4/AP-1 interactions in human colorectal cancer cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2015;35:3471–3490. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00030-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sugai M, Umezu H, Yamamoto T, Jiang S, Iwanari H, Tanaka T, et al. Expression of hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α in primary ovarian mucinous tumors. Pathol Int. 2008;58:681–686. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2008.02293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ma L, Zeng J, Guo Q, Liang X, Shen L, Li S, et al. Mutual amplification of HNF4α and IL-1R1 composes an inflammatory circuit in Helicobacter pylori associated gastric carcinogenesis. Oncotarget. 2016;7:11349–11363. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Patra KC, Wang Q, Bhaskar PT, Miller L, Wang Z, Wheaton W, et al. Hexokinase 2 is required for tumor initiation and maintenance and its systemic deletion is therapeutic in mouse models of cancer. Cancer Cell. 2013;24:213–228. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goos JA, de Cuba EM, Coupé VM, Diosdado B, Delis-Van Diemen PM, Karga C, et al. Glucose transporter 1 (SLC2A1) and vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA) predict survival after resection of colorectal cancer liver metastasis. Ann Surg. 2016;263:138–145. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sarvagalla S, Kolapalli SP, Vallabhapurapu S. The two sides of YY1 in cancer: a friend and a foe. Front Oncol. 2019;9:1230. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.01230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang F, Zhang H, Mei Y, Wu M. Reciprocal regulation of HIF-1α and lincRNA-p21 modulates the Warburg effect. Mol Cell. 2014;53:88–100. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lin A, Li C, Xing Z, Hu Q, Liang K, Han L, et al. The LINK-A lncRNA activates normoxic HIF1α signalling in triple-negative breast cancer. Nat Cell Biol. 2016;18:213–224. doi: 10.1038/ncb3295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang P, Cao L, Fan P, Mei Y, Wu M. LncRNA-MIF, a c-Myc-activated long non-coding RNA, suppresses glycolysis by promoting Fbxw7-mediated c-Myc degradation. EMBO Rep. 2016;17:1204–1220. doi: 10.15252/embr.201642067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Haberman Y, BenShoshan M, Di Segni A, Dexheimer PJ, Braun T, Weiss B, et al. Long ncRNA landscape in the ileum of treatment-naive early-onset Crohn disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:346–360. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izx013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guo S, Lu H. Novel mechanisms of regulation of the expression and transcriptional activity of hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α. J Cell Biochem. 2019;120:519–532. doi: 10.1002/jcb.27407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tan SK, Pastori C, Penas C, Komotar RJ, Ivan ME, Wahlestedt C, et al. Serum long noncoding RNA HOTAIR as a novel diagnostic and prognostic biomarker in glioblastoma multiforme. Mol Cancer. 2018;17:74. doi: 10.1186/s12943-018-0822-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang W, He X, Zheng Z, Ma X, Hu X, Wu D, et al. Serum HOTAIR as a novel diagnostic biomarker for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Mol Cancer. 2017;16:75. doi: 10.1186/s12943-017-0643-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhao R, Zhang Y, Zhang X, Yang Y, Zheng X, Li X, et al. Exosomal long noncoding RNA HOTTIP as potential novel diagnostic and prognostic biomarker test for gastric cancer. Mol Cancer. 2018;17:68. doi: 10.1186/s12943-018-0817-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhou X, Yin C, Dang Y, Ye F, Zhang G. Identification of the long non-coding RNA H19 in plasma as a novel biomarker for diagnosis of gastric cancer. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11516. doi: 10.1038/srep11516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]